A Definition of Advanced Practice Nursing

Mary Fran Tracy

“Not being heard is no reason for silence.”

∼ Victor Hugo

This chapter considers two central questions that provide the foundation for this book:

- ■ Why is it important to define carefully and clearly what is meant by the term advanced practice nursing?

- ■ What distinguishes the practices of advanced practice registered nurses (APRNs) from those of other nurses and other healthcare providers?

Advanced practice nursing is considered here as a concept, not a role, a set of skills, or a substitution for physicians. Rather, it is a powerful idea, the origins of which date back more than a century. Such a conceptual definition provides a stable core understanding for all APRN roles (see Chapter 2), it promotes consistency in practice that can aid others in understanding what this level of nursing entails, and it promotes the achievement of value-added patient outcomes and improvement in healthcare delivery processes. Advanced practice nursing is a relatively new concept in nursing’s evolution (see Chapter 1). Although debates and dissension are necessary and even healthy in forging consensus, ultimately the profession must agree on the key issues of definition, education, credentialing, and practice. Such agreement is critically important to the survival, as well as the growth, of advanced practice nursing. In the international context, although these issues may be defined differently by different countries, in-country standardization is likewise essential. In this chapter, advanced practice nursing is defined and the scope of practice of APRNs is discussed. Various APRN roles are differentiated and key factors influencing advanced practice in healthcare environments are identified. The importance of a common and unified understanding of the distinguishing characteristics of advanced practice nursing is emphasized.

The advanced practice of nursing builds on the foundation and core values of the nursing discipline. APRN roles do not stand apart from nursing; they do not represent a separate profession, although references to “the nurse practitioner (NP) profession,” for example, are seen in the literature. It is the nursing core that contributes to the distinctiveness seen in APRN practices as compared to non-nursing providers such as physician assistants. According to the American Nurses Association (ANA, 2010), nursing practice has seven essential features:

… provision of a caring relationship that facilitates health and healing; attention to the range of human experiences and responses to health and illness within the physical and social environments; integration of assessment data with knowledge gained from an appreciation of the patient or the group; application of scientific knowledge to the processes of diagnosis and treatment through the use of judgment and critical thinking; advancement of professional nursing knowledge through scholarly inquiry; influence on social and public policy to promote social justice; and, assurance of safe, quality, and evidence-based practice. (p. 9)

These characteristics are equally essential for advanced practice nursing. Core values that guide nurses in practice include advocating for patients; respecting patient and family values and informed choices; viewing individuals holistically within their environments, communities, and cultural traditions; and maintaining a focus on disease prevention, health restoration, and health promotion (ANA, 2015a; Friberg & Creasia, 2011; Hood, 2014). These core professional values also inform the central perspective of advanced practice nursing.

Efforts to standardize the definition of advanced practice nursing have been ongoing since the 1990s (American Association of Colleges of Nursing [AACN], 1995, 2006, 2021; ANA, 1995, 2003, 2010; APRN Joint Dialogue Group, 2008; Hamric, 1996, 2000, 2005, 2009, 2014; Hamric & Tracy, 2019; National Council of State Boards of Nursing [NCSBN], 1993, 2002). However, full clarity regarding advanced practice nursing has not yet been achieved, even as this level of nursing practice spreads around the globe. The growing international use of APRNs with differing understandings in various countries has only complicated the picture (see Chapter 5). The International Council of Nurses (ICN) continues to build upon their initial work in standardizing the definition and description of advanced practice nursing, recognizing it will continue to evolve. Advanced practice nursing roles are developing at different rates across the globe, scopes of practice and educational preparation vary, and there are debates about who is, and who is not, an APRN, among other challenging issues (ICN, 2020; Schober & Stewart, 2019).

Despite this lack of clarity (Burns-Bolton & Mason, 2012; Dowling et al., 2013; Pearson, 2011), emerging consensus on key features of the concept is increasingly evident. The definition developed by Hamric has been relatively stable throughout the seven editions of this book. The primary criteria used in this definition are now standard elements used in the United States and, increasingly, elsewhere to regulate APRNs. Similarly, consensus is growing in understanding advanced practice nursing in terms of core competencies. Even authors who deny a clear understanding of the advanced practice nursing concept propose competencies—variously called attributes, components, or domains—that are generally consistent with, although not always as complete as, the competencies proposed here.

It is important to distinguish the conceptual definition of advanced practice nursing from regulatory requirements for any APRN role (NCSBN, 2021a). Of necessity, regulatory understandings focus on the more basic and measurable primary criteria of graduate educational preparation, advanced certification in a particular population focus, and practice in one of the four common APRN roles: nurse practitioner (NP), clinical nurse specialist (CNS), certified registered nurse anesthetist (CRNA), and certified nurse-midwife (CNM). This approach is clearly seen in the APRN definition outlined in the Consensus Model for APRN Regulation (APRN Joint Dialogue Group, 2008) and has been very helpful and influential in standardizing state requirements for APRN licensure across the United States. Although necessary for regulation, this approach does not constitute an adequate understanding of advanced practice nursing. Limiting the profession’s understanding of advanced practice nursing to regulatory definitions can lead to a reductionist approach that results in a focus on a set of concrete skills and activities, such as diagnostic acumen or prescriptive authority. Understanding the advanced practice of the nursing discipline requires a definition that encompasses broad areas of skilled performance (the competency approach). As Chapter 2 notes, conceptual models and definitions are also useful for providing a robust framework for graduate APRN curricula and for building an APRN professional role identity.

DISTINGUISHING BETWEEN SPECIALIZATION AND ADVANCED PRACTICE NURSING

Before the definition of advanced practice nursing can be explored, it is important to distinguish between specialization in nursing and advanced practice nursing. Specialization involves the development of expanded knowledge and skills in a selected area within the discipline of nursing. All nurses with extensive experience in a particular area of practice (e.g., pediatric nursing, trauma nursing) are specialized in this sense. As the profession has advanced and responded to changes in health care, specialization and the need for specialty knowledge have increased. The AACN’s (2021) revised Essentials: Core Competencies for Professional Nursing Education also delineates specialization at an advanced education level that includes areas such as informatics and education. Thus few nurses are generalists in the true sense of the word. Although family NPs traditionally represented themselves as generalists, they are specialists in the sense discussed here because they have specialized in one of the many facets of health care—namely, primary care. As noted in Chapter 1, early specialization involved primarily on-the-job training or hospital-based training courses, and many nurses continue to develop specialty skills through practice experience and continuing education. Examples of currently evolving specialties include genetics nursing, forensic nursing, and clinical transplant coordination. As specialties mature, they may develop graduate-level clinical preparation and incorporate the competencies of advanced practice nursing for their most advanced practitioners (Hanson & Hamric, 2003); examples include critical care, oncology nursing, and palliative care nursing.

The nursing profession has responded in various ways to the increasing need for specialization in nursing practice. The creation of specialty organizations, such as the American Association of Critical-Care Nurses and the Oncology Nursing Society, has been one response. The creation of APRN roles—the CRNA and CNM roles early in nursing’s evolution and the CNS and NP roles more recently—has been another response. A third response has been the development of specialized faculty, nursing researchers, and nursing administrators. Nurses in all of these roles can be considered specialists in an area of nursing (e.g., education, research, administration); some of these roles may involve advanced education in a clinical specialty as well. However, they are not necessarily advanced practice nursing roles.

Advanced practice nursing includes specialization but also involves expansion and educational advancement (ANA, 2015b; Cronenwett, 1995). As compared with basic nursing practice, APRN practice is further characterized by the following: (1) acquisition of new practice knowledge and skills, particularly theoretical and evidence-based knowledge, some of which overlaps the traditional boundaries of medicine; (2) significant role autonomy; (3) responsibility for health promotion in addition to the diagnosis and management of patient problems, including prescribing pharmacologic and nonpharmacologic interventions; (4) the greater complexity of clinical decision making and leadership in organizations and environments; and (5) specialization at the level of a particular APRN role and population focus (ANA, 2015b; APRN Joint Dialogue Group, 2008).

It is necessary to distinguish between specialization as understood in this chapter and the term population focus. The framers of the Consensus Model for APRN regulation were interested in licensing and regulating advanced practice nursing in two broad categories. The first was regulation at the level of role—CNS, NP, CRNA, or CNM. The second category was termed population focus and, although not explicitly defined, six population foci were identified: family and individual across the life span, adult–gerontology, pediatrics, neonatal, women’s health and gender-related, and psychiatric/mental health. These foci are at different levels of specialization; for example, family and individual across the life span is broad, whereas neonatal is a subspecialty designation under the specialty of pediatrics. Therefore population focus is not synonymous with specialization and should not be understood in the same light. As the Consensus Model states:

Education, certification, and licensure of an individual must be congruent in terms of role and population foci. APRNs may specialize but they cannot be licensed solely within a specialty area. In addition, specialties can provide depth in one’s practice within the established population foci. … Competence at the specialty level will not be assessed or regulated by boards of nursing but rather by the professional organizations.

(APRN Joint Dialogue Group, 2008, p. 6)

DISTINGUISHING BETWEEN ADVANCED NURSING PRACTICE AND ADVANCED PRACTICE NURSING

The terms advanced practice nursing and advanced nursing practice have distinct definitions and cannot be seen as interchangeable. In particular, recent definitions of advanced nursing practice do not clarify the clinically focused nature of advanced practice nursing. For example, the third edition of Nursing’s Social Policy Statement defines the term advanced nursing practice as “characterized by the integration and application of a broad range of theoretical and evidence-based knowledge that occurs as part of graduate nursing education” (ANA, 2010, p. 9). This broad definition has evolved from the AACN’s Position Statement on the Practice Doctorate in Nursing (AACN, 2004), which recommended doctoral-level educational preparation for individuals at the most advanced level of nursing practice. The doctor of nursing practice (DNP) position statement (AACN, 2004) advanced a broad definition of advanced nursing practice as the following:

… any form of nursing intervention that influences health care outcomes for individuals or populations, including the direct care of individual patients, management of care for individuals and populations, administration of nursing and health care organizations, and the development and implementation of health policy. (p. 3)

A definition this broad goes beyond advanced practice nursing to include other advanced specialties not involved in providing direct clinical care to patients, such as administration, policy, informatics, and public health (AACN, 2021). One reason for such a broad definition was the desire to have the DNP degree be available to nurses practicing at the highest level in many varied specialties, not only those in APRN roles. A decision was reached by the original task force (AACN, 2004) that the DNP degree was not to be a clinical doctorate, as was advocated in early discussions (Mundinger et al., 2000), but, rather, a practice doctorate in an expansive understanding of the term practice. It is important to understand that the DNP is a degree, much as is the master’s of science in nursing, and not a role; DNP graduates can assume varied roles, depending on the specialty focus of their program. Some of these roles are not APRN roles as advanced practice nursing is defined here.

In the revised Essentials, AACN uses the term advanced nursing practice specialty versus advanced nursing practice role (i.e., APRN). However, even in this revised document, AACN interchanges the terms advanced nursing practice role and advanced practice nursing role (AACN, 2021). The nuances in the differences between these terms have not been clear to nurses in education and practice, professionals outside of nursing, and, at times, even DNP graduates themselves. As a result, the specific distinctions between the advanced specialties (such as administration) and APRN roles continue to require clarification. The current confusion in the United States also has global implications, though the international community more recently is using the term advanced nursing practice when referring to direct care roles that are comparable to US APRN roles (ICN, 2020; see Chapter 5).

Advanced practice nursing is a concept that applies to nurses who provide direct patient care to individual patients and families. As a consequence, APRN roles involve expanded clinical skills and abilities and require a different level of regulation than non-APRN roles. These skills afford APRNs unique perspectives in making broader practice decisions for individuals and populations specifically in their specialty areas. This text focuses on advanced practice nursing and the varied roles of APRNs. The revised Essentials’ discussion on both the advanced level of education of APRNs and those in specialty areas includes requirements for clinical practicums of direct and indirect care; the specific meaning of this is unclear at this time.

DEFINING ADVANCED PRACTICE NURSING

As noted, the concept of advanced practice nursing continues to be defined in various ways in the nursing literature. The Ovid Medline database defines the Medical Subject Heading of advanced practice nursing as:

evidence-based nursing, midwifery and healthcare grounded in research and scholarship. Practitioners include nurse practitioners, clinical nurse specialists, nurse anesthetists and nurse midwives.

(US National Library of Medicine, 2021)

This description is vague and relies primarily on a delineation of roles.

Advanced practice nursing is often defined as a constellation of four roles: the NP, CNS, CNM, and CRNA (APRN Joint Dialogue Group, 2008; Stanley, 2011). For example, the fourth edition of ANA’s Nursing: Scope and Standards of Practice does not provide a definition of advanced practice nursing but uses a regulatory and role-based definition of APRNs:

a subset of graduate-level prepared registered nurses who have completed an accredited graduate-level education program preparing the nurse for special licensure recognition and practice for one of the four recognized APRN roles: certified registered nurse anesthetist (CRNA), certified nurse-midwife (CNM), clinical nurse specialist (CNS), or certified nurse practitioner (CNP). APRNs assume responsibility and accountability for health promotion and/or maintenance, as well as the assessment, diagnosis, and management of healthcare consumer problems, which includes the use and prescription of pharmacologic and non-pharmacologic interventions (APRN Joint Dialogue Group, 2008). Some clinicians in this classification began APRN practice prior to the current educational preparation requirement and have been grandfathered to hold this designation.

(ANA, 2021, pp. 2–3)

In the past, some authors discussed advanced practice nursing only in terms of selected roles such as the NP and CNS roles (Lindeke et al., 1997; Rasch & Frauman, 1996) or the NP role exclusively (Hickey et al., 2000; Mundinger, 1994). Defining advanced practice nursing in terms of particular roles limits the concept and denies the unfortunate reality that some nurses in the four APRN roles are not using the core competencies of advanced practice nursing in their practice. These definitions are also limiting because they do not incorporate evolving and emergent APRN roles. Thus although such role-based definitions are useful for regulatory purposes, it is preferable to define and clarify advanced practice nursing as a concept without reference to particular roles.

CORE DEFINITION OF ADVANCED PRACTICE NURSING

The definition proposed in this chapter builds on and extends the understanding of advanced practice nursing proposed in the first six editions of this text. Important assertions of this discussion are as follows:

- ■ Advanced practice nursing is a function of educational and practice preparation and a constellation of primary criteria and core competencies.

- ■ Direct clinical practice is the central competency of any APRN role and informs all the other competencies.

- ■ All APRNs share the same core criteria and competencies, although the actual clinical skill set varies depending on the needs of the APRN’s specialty patient population.

A definition should also clarify the critical point that advanced practice nursing involves advanced nursing knowledge and skills; it is not a medical practice, although APRNs perform expanded medical therapeutics in many roles. Throughout nursing’s history, nurses have assumed medical roles. For example, common nursing tasks such as blood pressure measurement and administration of chemotherapeutic agents were once performed exclusively by physicians. When APRNs begin to transfer new skills or interventions into their repertoire, these become nursing skills, informed by the clinical practice values of the profession.

Actual practices differ significantly based on the particular role adopted, the specialty practiced, and the organizational framework within which the role is performed. Despite the need to keep job descriptions and job titles distinct in practice settings, it is critical that the public’s acceptance of advanced practice nursing be enhanced and confusion decreased. As Safriet (1993, 1998) noted, nursing’s future depends on reaching consensus on titles and consistent preparation for title holders. It is imperative for the nursing profession to be clear, concrete, and consistent about APRN titles and their functions in discussions with nursing’s larger constituencies: consumers, other healthcare professionals, healthcare administrators, and healthcare policymakers.

Conceptual Definition

Advanced practice nursing is the patient-focused application of an expanded range of competencies to improve health outcomes for patients and populations in a specialized clinical area of the larger discipline of nursing.a

In this definition, the term competencies refers to a broad area of skillful performance; six core competencies combine to distinguish nursing practice at this level. Competencies include activities undertaken as part of delivering advanced nursing care directly to patients. Some competencies are processes that APRNs use in all dimensions of their practice, such as collaboration and leadership. At this stage of the development of the nursing discipline, competencies may be based in theory, practice, or research. Although the discipline is expanding its research-based evidence to guide practice, an expanded ability to use theory also is a key distinguishing feature of advanced practice nursing. In addition, a strong experiential component is necessary to develop the competencies and clinical practice expertise that characterize APRN practice. Graduate education and in-depth clinical practice experiences work together to develop the APRN.

The definition also emphasizes the patient-focused and specialized nature of advanced practice nursing. APRNs expand their capability to provide and direct care, with the ultimate goal of improving patient and specialty population outcomes; this focus on outcome attainment is a central feature of advanced practice nursing and the main justification for differentiating this level of practice. Finally, the critical importance of ensuring that any type of advanced practice is grounded within the larger discipline of nursing is made explicit.

Certain activities of APRN practice overlap with those performed by physicians and other healthcare professionals. However, the experiential, theoretical, and philosophic perspectives of nursing make these activities advanced nursing when they are carried out by an APRN. Advanced practice nursing further involves highly developed nursing skill in areas such as guidance and coaching, as well as the performance of select medical interventions. Particularly with regard to physician practice, the nursing profession needs to be clear that advanced practice nursing is embedded in the nursing discipline—the advanced practice of nursing is not the junior practice of medicine.

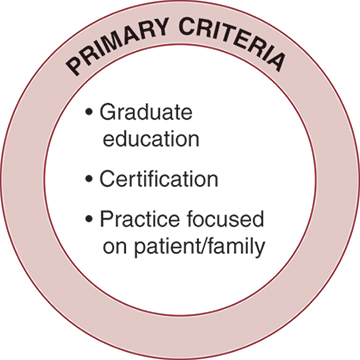

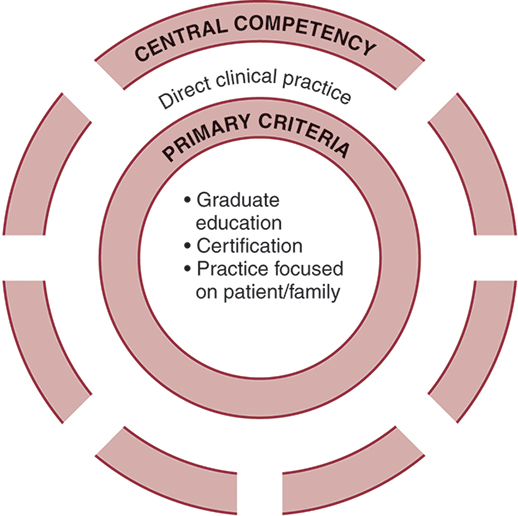

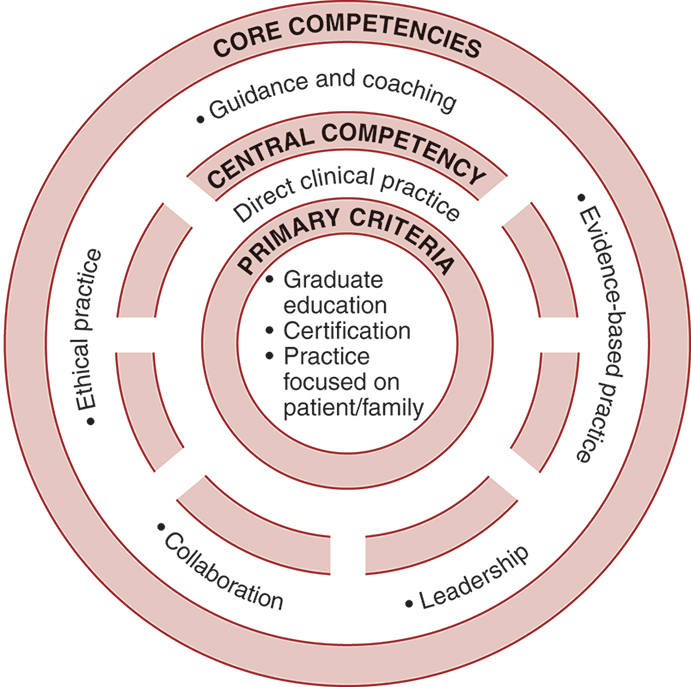

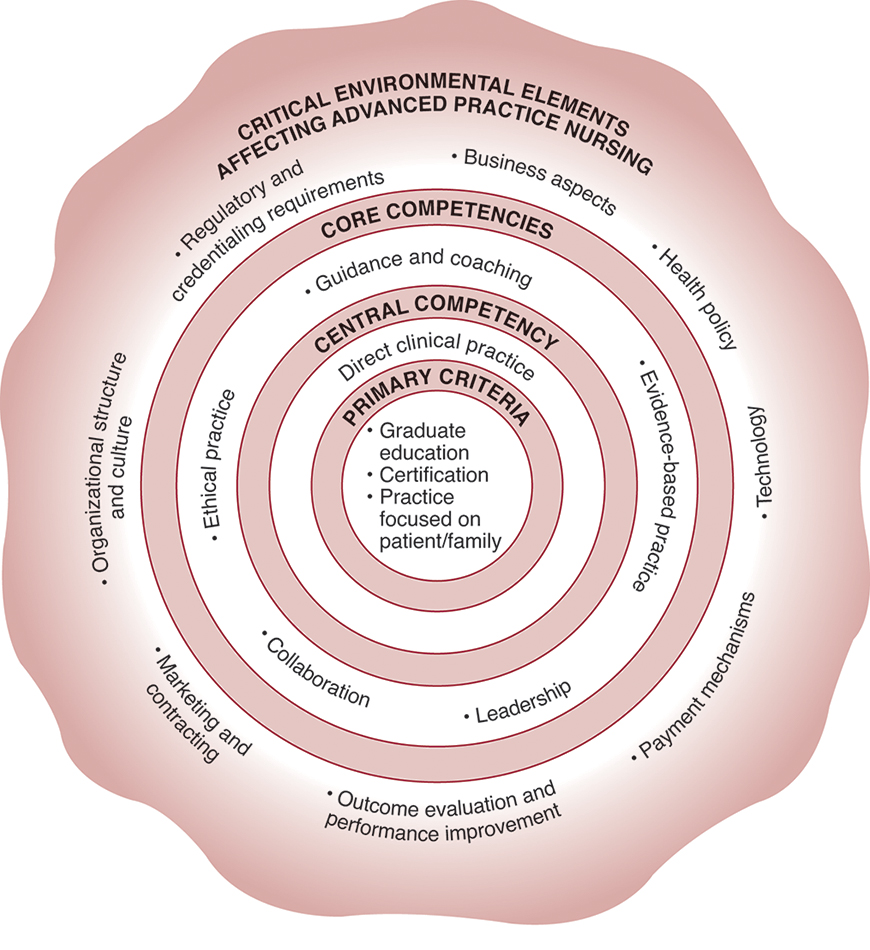

Advanced practice nursing is further defined by a conceptual model integrating three primary criteria and six core competencies, one of them central to the others. This discussion and the chapters in Part II of this text isolate each of these core competencies to clarify them. The reader should recognize that this is only a heuristic device for clarifying this conceptualization of advanced practice nursing. In reality, these elements are integrated into an APRN’s practice; they are not separate and distinct features. The concentric circles in Figs. 3.1 through 3.3 represent the seamless nature of this interweaving of elements. In addition, an APRN’s skills function synergistically to produce a whole that is greater than the sum of its parts. The essence of advanced practice nursing is found not only in the primary criteria and competencies demonstrated but also in the synthesis of these elements into a unified composite practice that conforms to the conceptual definition just presented.

Primary Criteria

Certain criteria (or qualifications) must be met before a nurse can be considered an APRN. Although these baseline criteria are not sufficient in and of themselves, they are necessary core elements of advanced practice nursing. The three primary criteria for advanced practice nursing are shown in Fig. 3.1 and include an earned graduate degree with a concentration in an advanced practice nursing role and population focus, national certification at an advanced level, and a practice focused on patients and their families. As noted, these criteria are most often the ones used by states to regulate APRN practice because they are objective and easily measured (see Chapter 20).

Graduate Education

First, the APRN must possess an earned graduate degree with a concentration in an APRN role. This graduate degree may be a master’s or a DNP. Advanced practice students acquire specialized knowledge and skills through study and supervised practice at the graduate level. Curricular content includes theories and research findings relevant to the core of a particular advanced nursing role, population focus, and relevant specialty. For example, a CNS interested in palliative care will need coursework in CNS role competencies, the adult population focus, and the palliative care specialty. Because APRNs assess, manage, and evaluate patients at the most independent level of clinical nursing practice, all APRN curricula contain specific courses in advanced health and physical assessment, advanced pathophysiology, and advanced pharmacology (the “three Ps”; AACN, 2021; APRN Joint Dialogue Group, 2008). Expansion of practice skills is acquired through faculty-supervised clinical experience, with master’s programs requiring a minimum of 500 clinical hours and DNP programs requiring 1000 hours. As noted earlier in the ANA definition, there is current consensus that a master’s education in nursing is a baseline requirement for advanced practice nursing; nurse-midwifery was the latest APRN specialty to agree to this requirement in 2009 (American College of Nurse-Midwives [ACNM], 2015).

Why is graduate educational preparation necessary for advanced practice nursing? Graduate education is a more efficient and standardized way to inculcate the complex competencies of APRN-level practice than nursing’s traditional on-the-job or apprentice training programs. As the knowledge base within specialties has grown, so, too, has the need for formal education at the graduate level. In particular, the skills necessary for evidence-based practice and the theory base required for advanced practice nursing mandate education at the graduate level.

Some of the differences between basic and advanced practice in nursing are apparent in the following: the range and depth of APRNs’ clinical knowledge; APRNs’ ability to anticipate patient responses to health, illness, and nursing interventions; their ability to analyze clinical situations and explain why a phenomenon has occurred or why a particular intervention has been chosen; the reflective nature of their practice; their skill in assessing and addressing nonclinical variables that influence patient care; and their attention to the consequences of care and improving patient outcomes. Because of the interaction and integration of graduate education in nursing and extensive clinical experience, APRNs are able to exercise a level of discernment in clinical judgment that is unavailable to other experienced nurses (Spross & Baggerly, 1989).

Professionally, requiring at least master’s-level preparation is important to create parity among APRN roles so that all can move forward together in addressing policymaking and regulatory issues. This parity advances the profession’s standards and ensures more uniform credentialing mechanisms. Moving toward a doctoral-level educational expectation may also enhance nursing’s image and credibility with other disciplines. Decisions by other healthcare providers, such as pharmacists, physical therapists, and occupational therapists, to require doctoral preparation for entry into their professions provided compelling support for nursing to establish the practice doctorate for APRNs to achieve parity with these disciplines (AACN, 2006). Nursing has a particular need to achieve greater credibility with medicine. Organized medicine has historically been eager to point to nursing’s internal differences in APRN education as evidence that APRNs are inferior providers.

The clinical nurse leader (CNL) role represents a different understanding of the master’s credential. Historically, master’s education in nursing was, by definition, specialized education (see Chapter 1). However, the master’s-prepared CNL is described as an “advanced generalist”; “a masters-educated nurse prepared for practice across the continuum of care within any healthcare setting in today’s changing healthcare environment” (AACN, 2013, p. 4). The revised Essentials (AACN, 2021) document is intended to address advanced-level nursing education and does not distinguish between master’s and DNP preparation. Even though CNLs have expanded leadership skills and graduate-level education, they are clearly not APRNs. APRN graduate education is highly specialized and involves preparation for an expanded scope of practice, neither of which characterizes CNL education. With the revised Essentials, it is even more important that the preparation of CNLs is clearly differentiated from that of the CNS for example. The existence of generalist and APRN specialty master’s programs has the potential to confuse consumers, institutions, and nurses alike; it is incumbent on educational programs to clearly differentiate the curricula for generalist CNL versus specialist APRN roles to avoid role confusion for these graduates. It is likewise important that CNL graduates understand that they are not APRNs.

The AACN’s proposed 2015 deadline for APRNs to be prepared at the DNP level was heavily debated (Cronenwett et al., 2011) and was not realized, even though the number of DNP programs increased dramatically (from 20 programs in 2006 to 357 in 2020 with an additional 106 new DNP programs in the planning stages; AACN, 2020). Master’s-level programs that prepare APRNs are continuing at this point in time.

Certification

The second primary criterion that must be met to be considered an APRN is professional certification for practice at an advanced level within a clinical population focus. The continuing growth of specialization has dramatically increased the amount of knowledge and experience required to practice safely in modern healthcare settings. National certification examinations have been developed by specialty organizations at two levels. The first level that was developed tested the specialty knowledge of experienced nurses and not knowledge at the advanced level of practice. More recently, organizations have developed APRN-specific certification examinations in a specialty. CNM and CRNA organizations were farsighted in developing certifying examinations for these roles early in their history (see Chapter 1). As regulatory groups, particularly state boards of nursing, increasingly use the certification credential as a component of APRN licensure, the certification landscape continues to change. As noted, the Consensus Model has mandated regulation of APRNs at a role and population focus level (APRN Joint Dialogue Group, 2008), accelerating the development of more broad-based APRN certification examinations.

National certification at an advanced practice level is an important primary criterion for advanced practice nursing. Continuing variability in graduate curricula makes sole reliance on the criterion of graduate education insufficient to protect the public. Although standardization in educational requirements for each APRN role has improved over the last decade, it is difficult to argue that graduate education alone can provide sufficient evidence of competence for regulatory purposes. National certification examinations provide a consistent standard that must be met by each APRN to demonstrate beginning competency for an advanced level of practice in their role. Certification also enhances title recognition in the regulatory arena, which promotes the visibility of advanced practice nursing and enhances the public’s access to APRN services.

It is critically important that certifying organizations work to clarify the certification credential as appropriate only for currently practicing APRNs. Given the centrality of the direct clinical practice component to the definition of advanced practice nursing, certification examinations must establish a significant number of hours of clinical practice as a requirement for maintaining APRN certification. Some faculty and nursing leaders who do not maintain a direct clinical practice component in their positions have been allowed to sit for certification examinations and represent themselves as APRNs. Statements such as “Once a CNS, always a CNS,” which are heard with NPs and CNMs as well, perpetuate the mistaken notion that an APRN title is a professional attribute rather than a practice role. Such a misunderstanding is confusing inside and outside of nursing; by definition, these individuals are no longer APRNs. This requires collaboration between academic institutions and healthcare organizations to support faculty to maintain a clinical practice as it is increasingly difficult to practice clinically above and beyond the faculty role.

As noted, the Consensus Model focuses regulatory efforts on these broad role and population foci rather than on particular specialties, although some specialties are represented (e.g., neonatal NPs). This decision not to recognize established APRN certification examinations in specialties such as oncology or critical care for state licensure purposes has challenged the CNS role more than other APRN specialties. The American Nurses Credentialing Center has become the dominant certifying organization for State Board of Nursing–supported CNS examinations. The number of examination options for CNSs has significantly decreased with Consensus Model implementation; the American Nurses Credentialing Center website (https://www.nursingworld.org/our-certifications/, March 10, 2022) maintains a listing of currently available CNS examinations. It is likely that the types of APRN certification examinations offered may continue to evolve as the Consensus Model evolves. Even though APRN regulation is becoming more standardized, a need exists for the continued development of specialty examinations at the advanced practice nursing level, particularly for CNS specialties; as it stands now, many CNSs have to take the broad-based certification examination recognized by their state in addition to an APRN-level specialty certification examination necessary for their practice. Another unintended consequence of the limitations set by recognizing only six population foci is that educational programs have closed CNS concentrations given the lack of a sanctioned certification examination in the specialty. Although other factors also influenced these decisions, not recognizing specialty examinations for regulatory purposes is a key factor in these closures. This issue is starting to impact NPs as well, as some are becoming increasingly specialized in areas such as diabetes care, pain management, and emergency care (Schumann & Tyler, 2018).

The limited population foci sanctioned at present can be seen as a first step in standardizing regulation; the Consensus Model report noted the expectation that additional population foci would evolve. Even with these transitional issues, the Consensus Model represents an important standardization of APRN regulation and has helped cement the primary criterion of certification as a core regulatory requirement for APRN licensure.

Practice Focused on Patient and Family

The third primary criterion necessary for one to be considered an APRN is a practice focused on patients and their families. As noted in describing DNP graduates, the AACN DNP Essentials Task Force differentiated APRNs from other roles using this primary criterion. They noted two general role categories (AACN, 2006):

roles which specialize as an advanced practice nurse (APN) with a focus on care of individuals; and roles that specialize in practice at an aggregate, systems, or organizational level. This distinction is important as APRNs face different licensure, regulatory, credentialing, liability, and reimbursement issues than those who practice at an aggregate, systems, or organizational level. (p. 17)

While not clearly delineated, the revised Essentials recognizes a difference between advanced-level graduates in an advanced nursing practice specialty and those in an advanced nursing practice role (i.e., APRNs; AACN, 2021). This criterion does not imply that direct practice is the only activity that APRNs undertake, however. APRNs also educate others, participate in leadership activities, and serve as consultants (Bryant-Lukosius et al., 2016); they understand and are involved in practice contexts to identify and effect needed system changes; they also work to improve the health of their specialty populations (AACN, 2021). However, to be considered an APRN role, the patient/family direct practice focus must be primary.

Historically, APRN roles have been associated with direct clinical care. Recent work is solidifying this understanding. The Consensus Model (APRN Joint Dialogue Group, 2008) has made clear that the provision of direct care to individuals as a significant component of their practice is the defining factor for all APRNs. The centrality of direct clinical practice is further reflected in the core competencies presented in the next section.

Why limit the definition of advanced practice nursing to roles that focus on clinical practice to patients and families? There are many reasons. Nursing is a practice profession. The nurse–patient interface is at the core of nursing practice; in the final analysis, the reason that the profession exists is to render nursing services to individuals in need of them. Clinical practice expertise in a given specialty develops from these nurse–patient encounters and lies at the heart of advanced practice nursing. Ongoing direct clinical practice is necessary to maintain and develop an APRN’s expertise. Without regular immersion in practice, the cutting-edge clinical acumen and expertise found in APRN practices cannot be sustained. For example, CNSs who are required to function at a healthcare organization system level may be relegated to expertise in only one or two spheres of impact (i.e., nurses and nursing personnel sphere, organizations and systems sphere). Without interaction in the patient direct care sphere, they must rely on the perspective of others (e.g., nurses, administrators) in planning and carrying out improvement activities and policies rather than using their advanced assessment and evaluation skills to fully understand problems and develop potential solutions.

If every specialized role in nursing were considered advanced practice nursing, the term would become so broad as to lack meaning and explanatory value. Distinguishing between APRN roles and other specialized roles in nursing can help clarify the concept of advanced practice nursing to consumers, other healthcare providers, and even other nurses. In addition, the monitoring and regulation of advanced practice nursing are increasingly important issues as APRNs work toward more authority for their practices (see Chapter 20). If the definition of advanced practice nursing included nonclinical roles, development of sound regulatory mechanisms would be impossible.

It is critical to understand that this definition of advanced practice nursing is not a value statement but, rather, a differentiation of one group of nurses from other groups for the sake of clarity within and outside the profession. Some nurses with specialized skills in administration, research, and community health have viewed the direct practice requirement as a devaluing of their contributions. Some faculty who teach clinical nursing but do not themselves maintain an advanced clinical practice have also thought themselves to be disenfranchised because they are not considered APRNs by virtue of this primary criterion. Perhaps this problem has been exacerbated with use of the term advanced, because this term can inadvertently imply that nurses who do not fit into the APRN definition are not advanced (i.e., are not as well prepared or highly skilled as APRNs).

No value difference exists between nurses in broad specialties and APRNs; both groups are equally important to the overall growth and strengthening of the profession. The profession must be able to differentiate its various roles without such differentiation being viewed as a disparagement of any one group. We must be able to say what advanced practice nursing is not, as well as what it is, if we are to ensure clarity of the concept within and outside the profession. As the AACN (2021) has noted, all nurses—whether their focus is clinical practice, educating students, conducting research, planning community programs, or leading nursing service organizations—are valuable and necessary to the integrity and growth of the discipline. However, all nurses, particularly those with advanced degrees, are not the same, nor are they necessarily APRNs. Historically, the profession has had difficulty differentiating itself and has struggled with the prevailing lay notion that “a nurse is a nurse is a nurse.” This antiquated view does not match the reality and increasing complexity of the healthcare arena, nor does it celebrate the diverse contributions of all the various nursing roles and specialties.

SIX CORE COMPETENCIES OF ADVANCED PRACTICE NURSING

Direct Clinical Practice: The Central Competency

As noted earlier, the primary criteria are necessary but insufficient elements of the definition of advanced practice nursing. Advanced practice nursing is further defined by a set of six core competencies that are enacted in each APRN role. The first core competency of direct clinical practice is central to and informs all of the others (see Fig. 3.2). In one sense, it is “first among equals” of the six core competencies that define advanced practice nursing. Although APRNs do many things, excellence in direct clinical practice provides the foundation necessary for APRNs to execute the other competencies, such as collaboration, guidance and coaching, and leadership within organizations.

However, clinical expertise alone should not be equated with advanced practice nursing. The work of Patricia Benner and colleagues (Benner, 1984; Benner et al., 1996, 1999, 2008) is a major contribution to an understanding of clinically expert nursing practice. These researchers extensively studied expert nurses in acute care clinical settings and described the engaged clinical reasoning and domains of practice seen in clinically expert nurses. Although some of the participants in this research were APRNs (in the most recent report [Benner et al., 1999], 16% of the nurse participants were APRNs), most were nurses with extensive clinical experience who did not have APRN preparation. Calkin (1984) has characterized these latter nurses as “experts by experience.” (See Chapter 2 for a discussion of Calkin’s conceptual differentiation between levels of nursing practice.) Benner and colleagues did not discuss differences in the practices of APRNs as compared with other nurses that they have studied. They stated that “‘Expert’ is not used to refer to a specific role such as an advanced practice nurse. Expertise is found in the practice of experienced clinicians and advanced practice nurses” (Benner et al., 1999, p. 9).

Although clinical expertise is a central ingredient of an APRN’s practice, the direct care practice of APRNs is distinguished by six characteristics: (1) use of a holistic perspective, (2) formation of therapeutic partnerships with patients, (3) expert clinical performance, (4) use of reflective practice, (5) use of evidence as a guide to practice, and (6) use of diverse approaches to health and illness management (see Chapter 6). These characteristics help distinguish the practice of the expert by experience from that of the APRN. APRN clinical practice is also informed by a population focus (AACN, 2021), because APRNs work to improve the care for their specialty patient population, even as they care for individuals within the population. As noted, experiential knowledge and graduate education combine to develop these characteristics in an APRN’s clinical practice. It is important to note that the “three Ps” that form core courses in all APRN programs (pathophysiology, pharmacology, and physical assessment) are not separate competencies in this understanding but provide baseline knowledge and skills to support the direct clinical practice competency.

The specific content of the direct practice competency differs significantly by specialty. For example, the clinical practice of a CNS dealing with critically ill children differs from the expertise of an NP managing the health maintenance needs of older adults or a CRNA administering anesthesia in an outpatient surgical clinic. In addition, the amount of time spent in direct practice differs by APRN specialty. CNSs in particular may spend most of their time in activities other than direct clinical practice (see Chapter 12). Thus it is important to understand this competency as a central defining characteristic of advanced practice nursing rather than as a particular skill set or expectation that APRNs only engage in direct clinical practice.

Additional Advanced Practice Nurse Core Competencies

In addition to the central competency of direct clinical practice, five other competencies further define advanced practice nursing regardless of role function or setting. As shown in Fig. 3.3, these additional core competencies are as follows:

These competencies have repeatedly been identified as essential features of advanced practice nursing. In addition, each role is differentiated by some unique competencies (see the specific role chapters in Part III of this text). The nature of the patient population receiving APRN care, organizational expectations, emphasis given to specific competencies, and practice characteristics unique to each role distinguish the practice of one APRN group from others. Each APRN role organization publishes role-specific competencies on their websites: the National Association of Clinical Nurse Specialists (NACNS) for CNSs (www.nacns.org), the National Organization of Nurse Practitioner Faculties for NPs (www.nonpf.org), the ACNM for CNMs (www.acnm.org), and the American Association of Nurse Anesthesiology for CRNAs (www.aana.com). There is a dynamic interplay between the core APRN competencies and each role; role-specific expectations grow out of the core competencies and similarly serve to inform them as APRNs practice in a changing healthcare system. In addition, competencies promoted by other professional groups become important to the understanding of advanced practice nursing; for example, the Interprofessional Education Collaborative competencies on interprofessional practice are helping to shape the understanding of collaboration (Interprofessional Education Collaborative Expert Panel, 2016; see Chapter 10).

It is also important to understand that each of the competencies described in Part II of this text have specific definitions in the context of advanced practice nursing. For example, leadership has clinical, professional, and systems expectations for the APRN that differ from those for a nurse executive or staff nurse. These unique definitions of each competency help distinguish practice at the advanced level. Similarly, certain competencies are important components of other specialized nursing roles. For example, collaboration is an important competency for nursing administrators. The uniqueness of advanced practice nursing is seen in the synergistic interaction between direct clinical practice and this constellation of competencies. In Fig. 3.3, the openings between the central practice competency and these additional competencies represent the fact that the APRN’s direct practice skill interacts with and informs all the other competencies. For example, APRNs collaborate with other providers who seek their practice expertise to plan care for specialty patients. They are able to provide expert guidance and coaching for patients going through health and illness transitions because of their direct practice experience and insight.

The core competencies are not unique to APRN practices. Physicians and other healthcare providers may have developed competency in some of them. Experienced staff nurses may master several of these competencies with years of practice experience. These nurses are seen as exemplary performers and are often encouraged to enter graduate school to become APRNs. What distinguishes APRN practice is the expectation that every APRN’s practice encompasses all of these competencies and seamlessly blends them into daily practice encounters. This expectation makes APRN practice unique among that of other providers.

These complex competencies develop over time. No APRN emerges from a graduate program fully prepared to enact all of them. However, it is critical that graduate programs provide exposure to each competency in the form of didactic content and practical experience so that new graduates can be prepared to utilize them at the basic core level, be given a base on which to build their practices, and be tested for initial credentialing. These key competencies are described in detail in subsequent chapters and are not further elaborated here.

Scope of Practice

The term scope of practice refers to the legal authority granted to a professional to provide and be reimbursed for healthcare services. It is intended to protect the public from unsafe, unqualified healthcare providers. The ANA (2021) defined the scope of nursing practice as “… the description of the who, what, where, when, why, and how associated with nursing practice and roles” (p. 113). This authority for practice emanates from many sources, such as state and federal laws and regulations, the profession’s code of ethics, and professional practice standards. For all healthcare professionals, scope of practice is most closely tied to state statutes; for nursing in the United States, these statutes are the nurse practice acts of the various states. As previously discussed, APRN scope of practice is characterized by specialization; expansion of services provided, including diagnosing and prescribing; and autonomy to practice (APRN Joint Dialogue Group, 2008). The scopes of practice also differ among the various APRN roles; various APRN organizations have provided detailed and specific descriptions for their particular role. Carving out an adequate scope of APRN practice authority has been a historic struggle for most of the advanced practice groups (see Chapter 1), and this continues to be a hotly debated issue among and within the health professions. Significant variability in state practice acts continues, such that APRNs can perform certain activities in some states, notably prescribing certain medications and practicing without physician supervision, but may be constrained from performing these same activities in other states (NCSBN, 2021a). The Consensus Model’s proposed regulatory language can be used by states to achieve consistent scope of practice language and standardized APRN regulation (APRN Joint Dialogue Group, 2008).

Although more than 2 decades old, a report by the Pew Health Professions Commission (Finocchio et al. & Taskforce on Health Care Workforce Regulation, 1998) remains relevant today. The Taskforce noted that the tension and turf battles between professions and the increased legislative activities in this area “clog legislative agendas across the country (p. ii).” These battles are costly and time-consuming, and lawmakers’ decisions related to scope of practice are frequently distorted by campaign contributions, lobbying efforts, and political power struggles rather than being based on empirical evidence. More recently, while the National Academy of Medicine reported that progress continues on a state-by-state basis in achieving full practice authority for APRNs, there are still many states where APRNs have reduced or restricted practice authority (National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, & Medicine [NASEM], 2016; Phillips, 2021; see Chapter 20 for further discussion). In addition, the National Academy of Medicine highlighted the fact that medical staff member and hospital privileging criteria are inconsistent due to state laws as well as business preferences. Opposition by some physician associations and physicians is ongoing and has been a significant barrier. Much work remains to be done. The National Academy of Medicine recommended that the coalition of stakeholders to remove these barriers needs to be expanded and diversified to increase collaboration in improving health care for patients (NASEM, 2021).

DIFFERENTIATING ADVANCED PRACTICE ROLES: OPERATIONAL DEFINITIONS OF ADVANCED PRACTICE NURSING

As noted earlier, it is critical to the public’s understanding of advanced practice nursing that APRN roles and resulting job titles reflect actual practices. Because actual practices differ, job titles should differ. The following corollary is also true—if the actual practices do not differ, the job titles should not differ. For example, some institutions have retitled their CNSs clinical coordinators or clinical educators, even though these APRNs are practicing consistently with the practices of a CNS. This change in job title renders the CNS practice less clearly visible in the clinical setting and thereby obscures CNS role clarity. An example is in Virginia, where state regulators label advanced practice nurses as licensed nurse practitioners for all four APRN roles, further sowing confusion in health care and the public. As noted, differences among roles must be clarified in ways that promote understanding of advanced practice nursing, and the Consensus Model (APRN Joint Dialogue Group, 2008) clarifies appropriate titling for APRNs.

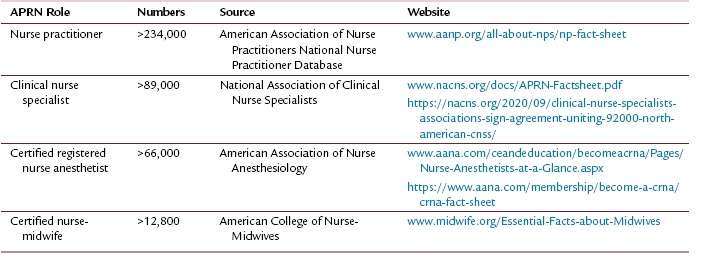

Workforce Data

It is difficult to obtain accurate numbers for APRNs by role, particularly for those prepared as CNSs. The US Bureau of Labor Statistics has separate classifications for NPs, CRNAs, and CNMs in their Standard Occupational Classification listing, so some data are collected when the Bureau does routine surveys. However, CNSs are not listed as a separate role in the classification system; rather the role is subsumed under the general registered nurse (RN) classification (US Bureau of Labor Statistics, 2021a, 2021b). The Bureau of Labor Statistics has refused to add a CNS classification despite repeated attempts to convince them otherwise. Therefore the latest APRN role numbers are based on the respective organizational data for consistency (Table 3.1).

Table 3.1

| APRN Role | Numbers | Source | Website |

|---|---|---|---|

| Nurse practitioner | >234,000 | American Association of Nurse Practitioners National Nurse Practitioner Database | www.aanp.org/all-about-nps/np-fact-sheet |

| Clinical nurse specialist | >89,000 | National Association of Clinical Nurse Specialists | www.nacns.org/docs/APRN-Factsheet.pdf |

| Certified registered nurse anesthetist | >66,000 | American Association of Nurse Anesthesiology | www.aana.com/ceandeducation/becomeacrna/Pages/Nurse-Anesthetists-at-a-Glance.aspx

https://www.aana.com/membership/become-a-crna/crna-fact-sheet |

| Certified nurse-midwife | >12,800 | American College of Nurse-Midwives | www.midwife.org/Essential-Facts-about-Midwives |

It is essential to have accurate tracking of APRN numbers by distinct role as well as by geographic distribution and basic demographic statistics. Gathering data only on select APRN roles or as subcategories of the RN role diminishes the profession’s ability to actively and appropriately advocate for patients on a national level for needed care that can best be provided by APRNs.

Four Established Advanced Practice Nurse Roles

Advanced practice nursing is applied in the four established roles and in emerging roles. These APRN roles can be considered to be the operational definitions of the concept of advanced practice nursing. Although each APRN role has the common definition, primary criteria, and competencies of advanced practice nursing at its center, each has its own distinct form. Some of the distinctive features of the various roles are listed here. Differences and similarities among roles are further explored in Part III of this text.

The NACNS (2019) has distinguished CNS practice by characterizing three “spheres of impact” in which the CNS operates. These include the patient direct care sphere, the nurses and nursing practice sphere, and the organizations and systems sphere (see Chapter 12). A CNS is first and foremost a clinical expert who provides direct care to patients with complex health problems. CNSs not only learn collaboration processes, as do other APRNs, but also function as formal consultants to nursing staff and other care providers within their organizations. Developing, supporting, and educating nursing staff and other interprofessional staff to improve the quality of patient care comprise a core part of the nurses and nursing practice sphere. Managing system change in complex organizations to build teams and improve nursing practices and effecting system change to enable better advocacy for patients are additional role expectations of the CNS. Expectations regarding sophisticated evidence-based practice activities have been central to this role since its inception.

NPs, whether in primary care or acute care, possess advanced health assessment, diagnostic, and clinical management skills that include pharmacology management. Their focus is expert direct care, managing the health needs of individuals and their families. Incumbents in the classic NP role provide primary health care focused on wellness and prevention; NP practice also includes caring for patients with minor, common acute conditions and stable chronic conditions (see Chapter 13). The acute care NP (ACNP) brings practitioner skills to a specialized patient population within the acute care setting. The ACNP’s focus is the diagnosis and clinical management of acutely or critically ill patient populations in a particular specialized setting. Acquisition of additional medical diagnostic and management skills, such as interpreting computed tomography and magnetic resonance imaging scans, inserting chest tubes, and performing lumbar punctures, also characterizes this role (see Chapter 14).

The CNM (see Chapter 15) has advanced health assessment and intervention skills focused on women’s health and childbearing. CNM practice involves independent management of women’s health care. CNMs focus particularly on pregnancy, childbirth, the postpartum period, and neonatal care, but their practices also include family planning, gynecologic care, primary health care for women through menopause, and treatment of male partners for sexually transmitted infections (ACNM, 2020). The CNM’s focus is on providing direct care to a select patient population.

CRNA practice (see Chapter 16) is distinguished by advanced procedural and pharmacologic management of patients undergoing anesthesia. CRNAs practice independently, in collaboration with physicians, or as employees of a healthcare institution. Like CNMs, their primary focus is providing direct care to a select patient population. Both CNM and CRNA practices are also distinguished by well-established national standards and certification examinations in their specialties.

These differing roles and their similarities and distinctions are explored in detail in subsequent chapters. It is expected that other roles may emerge as health care continues to change and new opportunities become apparent. This brief discussion underscores the rich and varied nature of advanced practice nursing and the necessity for retaining and supporting different APRN roles and titles in the healthcare marketplace. At the same time, the consistent definition of advanced practice nursing described here undergirds each of these roles, as will be seen in Part III of this text.

CRITICAL ELEMENTS IN MANAGING ADVANCED PRACTICE NURSING ENVIRONMENTS

The healthcare arena is increasingly fluid and changeable; some would even say it is chaotic. Advanced practice nursing does not exist in a vacuum or a singular environment. Rather, this level of practice occurs in a wide variety of healthcare delivery environments. These diverse environments are complex admixtures of interdependent elements, as noted in Fig. 3.4. The term environment refers to any milieu in which an APRN practices, ranging from a community-based rural healthcare practice for a primary care NP to a complex tertiary healthcare organization for an ACNP. Certain core features of these environments dramatically shape advanced practice and must be managed by APRNs in order for their practices to survive and thrive (Fig. 3.4). Although not technically part of the core definition of advanced practice nursing, these environmental features are included here to frame the understanding that APRNs must be aware of these key elements in any practice setting. Furthermore, APRNs must be prepared to contend with and shape these aspects of their practice environment to be able to enact advanced practice nursing fully.

The environmental elements that affect APRN practice include the following:

- ■ Managing reimbursement and payment mechanisms

- ■ Dealing with marketing and contracting considerations

- ■ Understanding legal, regulatory, and credentialing requirements

- ■ Understanding and shaping health policy considerations

- ■ Strengthening organizational structures and cultures to support advanced practice nursing

- ■ Using technology to optimize patient care

- ■ Enabling outcome evaluation and performance improvement

With the exception of organizational structures and cultures, Part IV of this text explores these elements in depth. Discussion of organizational considerations is presented in Chapter 4 and woven throughout the chapters in Part III.

Common to all of these environmental elements is the increasing use of technology and the need for APRNs to master various new technologies to improve patient care and healthcare systems. The ability to use information systems and technology and patient care technology is an essential element of graduate-level curricula (AACN, 2021). Electronic technology in the form of electronic health records, coding schemas, communications, Internet use, and provision of care across state lines through telehealth practices is changing healthcare practice. These changes, in turn, are reshaping all six APRN core competencies. Proficiency in the use of new technologies is increasingly necessary to support clinical practice, implement quality improvement initiatives, and provide leadership to evaluate outcomes of care and care systems (see Chapters 22 and 23).

Managing the business and legal aspects of practice is increasingly critical to APRN survival in the competitive healthcare marketplace. All APRNs must understand current reimbursement issues, even as changes related to the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (2010) and the Medicare Access and CHIP Reauthorization Act (2015) are being debated, re-debated, and advanced. Payment mechanisms and legal constraints must be managed, regardless of setting. Given the increasing competition among physicians, APRNs, and nonphysician providers, APRNs must be prepared to market their services assertively and knowledgeably. Marketing oneself as a new NP in a small community may look different from marketing oneself as a CNS in a large health system, but the principles are the same (Chapter 18). Marketing considerations often include the need to advocate for and actively create positions that do not currently exist. Contract considerations are much more complex at the APRN level, and all APRNs, whether newly graduated or experienced, must be prepared to enter into contract negotiations.

Health policy at the state and federal levels is an increasingly potent force shaping advanced practice nursing; regulations and policies that flow from legislative actions can enable or constrain APRN practices. Variations in the strength and number of APRNs in various states attest to the power of this environmental factor. Organizational structures and cultures, whether those of a community-based practice or a hospital unit, are also important facilitators of or barriers to advanced practice nursing; APRN students must learn to assess and intervene to build organizations and cultures that strengthen APRN practice. Finally, APRNs are accountable for the use of evidence-based practice to ensure positive patient and system outcomes. Measuring the favorable impact of advanced practice nursing on these outcomes and effecting performance improvements are essential activities that all APRNs must be prepared to undertake because continuing to demonstrate the value of APRN practice is a necessity in chaotic practice environments (Chapter 21).

Special mention must be made of healthcare quality. Reimbursement is being increasingly tied to quality metrics, with higher expectations for transparency of quality outcomes by providers. As quality concerns have escalated, more attention is being focused on quality metrics for all settings (see Chapter 23). As noted in the Future of Nursing 2020–2030 report, it is imperative that issues such as structural racism, social determinants of health, and diversity in the healthcare workforce be acknowledged and addressed (NASEM, 2021). Achieving quality health care for all is dependent on resolving these issues in order to ensure even the basic first step of equitable access to the healthcare system and appropriate care and treatment. APRNs are an important part of the solution to ensuring quality outcomes for their specialty populations. Quality is not itself a competency or an environmental element, but it is an important feature that should be evident in the processes that APRNs use and the outcomes that they achieve. For example, coaching for wellness should demonstrate the quality processes of a therapeutic nurse–patient relationship and the patient being a partner with the APRN in achieving wellness outcomes. The importance of APRN involvement in quality initiatives can be seen in the work of the Nursing Alliance for Quality Care, a national partnership of organizations, consumers, and other stakeholders in the safety and quality arena (http://www.naqc.org).

IMPLICATIONS OF THE DEFINITION OF ADVANCED PRACTICE NURSING

A number of implications for education, regulation and credentialing, practice, and research flow from this understanding of advanced practice nursing. The Consensus Model (APRN Joint Dialogue Group, 2008) makes the important point that effective communication among legal and regulatory groups, accreditors, certifying organizations, and educators (licensing, accreditation, certification, and education [LACE]) is necessary to advance the goals of advanced practice nursing. Decisions made by each of these groups affect and are affected by all the others. Historically, advanced practice nursing has been hampered by the lack of consensus in APRN definition, terminology, educational and certification requirements, and regulatory approaches. The Consensus Model process, by combining stakeholders from each of the LACE areas, took a giant step forward toward the profession’s achieving needed consensus on APRN practice, education, certification, and regulation.

Implications for Advanced Practice Nursing Education

Graduate programs should provide anticipatory socialization experiences to prepare students for their chosen APRN role. Graduate experiences should include practice in all of the competencies of advanced practice nursing, not just direct clinical practice. For example, students who have no theoretical base or guided practice experiences in collaboration skills or clinical, professional, and systems leadership will be ill-equipped to demonstrate these competencies on assuming a new APRN role. In addition, APRN students need to understand the critical elements in healthcare environments, such as the business aspects of practice and healthcare policy that must be managed if their practices are to survive and grow.

All APRN roles require at least a specialty master’s education; master’s programs are continuing for the foreseeable future even as the DNP degree is being developed in many institutions. The profession has embraced a wide variety of graduate educational models for preparing APRNs, including direct-entry programs for non-nurse college graduates and RN-to-master’s of science in nursing programs. However, three of the four APRN professional organizations have endorsed doctoral preparation as entry into APRN practice (the AANA by the year 2025 [AANA, 2007], the NACNS by the year 2030 [NACNS, 2015], and the National Organization of Nurse Practitioner Faculties by 2025 [2018]). Ensuring quality and standardization of APRN education in the various specialties is imperative if the profession is to guarantee a highly skilled, uniformly educated APRN workforce to the public. The definition of advanced practice nursing used here can serve as a guide for developing quality courses and clinical practice experiences that prepare APRN students to practice at an advanced level.

It is imperative that nursing leaders and DNP faculty continue to provide increased clarity for the terms advanced nursing practice and advanced practice nursing. The differences between the two, despite being significant in the practice setting, are easily lost on the majority of RNs and even DNP graduates not prepared in an APRN role. Lack of clarity about this distinction has created ongoing problems as DNP graduates prepared in areas other than as an APRN confuse their combined graduate preparation and their RN clinical experience with being an APRN. This type of confusion about roles within nursing only perpetuates the ongoing lack of clarity when communicating with physicians and policymakers (Carter et al., 2013, 2014) and compromises the progress that APRNs have made in the practice arena.

Implications for Regulation and Credentialing

Significant progress has been made toward an integrative view of APRN regulation over the past decade, culminating in the LACE regulatory framework detailed in the Consensus Model. In particular, the primary criteria of graduate education, advanced certification, and focus on direct clinical practice for all APRN roles proposed in Hamric’s definition have been affirmed as the key elements in regulating and credentialing APRNs (APRN Joint Dialogue Group, 2008). Such internal cohesion can go a long way toward removing barriers to the public’s access to APRN care.

The Consensus Model has been an important unifying force within the APRN community. The regulatory clarity in this document has increasingly been seen in other national statements, and the work was highlighted in the Institute of Medicine’s (IOM) report, The Future of Nursing (IOM, 2011). The NCSBN has embarked on the “APRN Campaign for Consensus,” a nationwide effort to have this model enacted in all states. However, as of August 2021, only 16 states and two territories have fully implemented the Consensus Model into legislation (NCSBN, 2021b).

The IOM report also has given rise to action coalitions, funded by the AARP Foundation and the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, in numerous states (Campaign for Action, n.d.). The Campaign for Action has a dual focus, implementing solutions to the challenges facing the nursing profession and strengthening nurse-based approaches to transform how Americans receive quality health care. Although the Campaign for Action is broader in scope than just advanced practice nursing, many of the solutions for transforming health care involve APRNs being able to practice to the full extent of their education. It is critically important for all APRNs to be aware of and involved in these efforts.

One implication for credentialing flows from the diverse specialty and role base of advanced practice nursing. APRNs must practice and be certified in the specific population focus and role for which they have been educated. APRNs who wish to change their specialty, population focus, or APRN role need to return to school for education targeted to that area. The days are past when a primary care NP could take a job in a specialized acute care practice without further education to prepare for that specialty. This issue of aligning APRN job expectations with education and certification is not always well understood by practice environments, educators, or even APRNs themselves. However, the need to ensure congruence between an APRN’s specialty, education, certification, role, and subsequent practice has been identified by regulators; more stringent regulations regarding this issue have been promulgated (NCSBN, 2021a).

Implications for Research

As noted in Chapter 8, one of the core competencies of advanced practice nursing is the use of an evidence base in an APRN’s practice and in changing the practice environment to incorporate the use of evidence. The practice doctorate initiative identified the increased need for leadership in evidence-based practice and for application of knowledge to solve practice problems and improve health outcomes as reasons for moving to the DNP degree for APRN practice (AACN, 2006); the emphasis has continued in the revised Essentials document (AACN, 2021). If research is to be relevant to healthcare delivery and to nursing practice at all levels, APRNs must be involved. APRNs need to recognize the importance of advancing the profession’s and healthcare system’s knowledge about effective patient care practices and to realize that they are a vital link in building and translating this knowledge into clinical practice.

Related to this research involvement is the necessity for more research differentiating basic and advanced practice nursing and identifying the patient populations that benefit most from APRN intervention. For example, there is compelling empirical evidence that APRNs can effectively manage chronic disease—preventing or mitigating complications, reducing rehospitalizations, and increasing patients’ quality of life. This evidence is presented in the chapters in Part III of this text and in Chapter 21. Linking advanced practice nursing to specific patient outcomes remains a major research imperative for this century. It is interesting to note the increasing research being conducted in international settings as more countries implement advanced practice nursing and study the effectiveness of these new practitioners.

Similarly, research is needed on the outcomes of the different APRN educational pathways in terms of APRN graduate experiences and patient outcomes. Such data would be invaluable in continuing to refine advanced practice education. Outcomes achieved by graduates from DNP programs need similar study in comparison to master’s-level APRN graduates; in critiquing the need for the DNP degree, Fulton and Lyon (2005) noted the absence of research data on whether there are weaknesses in current master’s-level graduates.

Finally, it is incumbent upon DNP faculty to ensure that APRNs understand their role in evidence-based practice vis-à-vis research. In fact, faculty themselves continue to struggle with knowledge and understanding of evidence-based practice and its use in the completion of the scholarly DNP project (AACN, 2015; Dols et al., 2017). Translational, evidence-based practice change, and quality improvement projects are the proper foci for DNP projects; such projects require a complex skill set that is the focus of DNP evidence-based practice courses. DNP students are not sufficiently educated in the particulars of the formal research process to be prepared to conduct independent research successfully, and faculty have an important responsibility to assist the student to identify an appropriate topic. Unfortunately, it is not uncommon to encounter APRN DNP projects that are not an implementation of evidence-based practice or a clinical change project to bring research evidence to influence practice, but rather involve the conduct of a research study. The DNP-prepared APRN is an evidence-based practice expert who evaluates and generates internal evidence, translates research into sustainable practice changes, and uses research to make practice decisions that improve the quality of patient care (AACN, 2021; Melnyk, 2016). Without this important understanding, nursing runs the risk of implying that advancing the science of nursing through research no longer requires PhD preparation. Such a misunderstanding could lead practice institutions to hire DNP graduates with the intention that they conduct rigorous independent research. It could also substantially delay the translation of research findings into clinical practice.

Implications for Practice Environments

Because of the centrality of direct clinical practice, APRNs must hold on to and make explicit their direct patient care activities. They must also articulate the importance of this level of care for patients. In addition, it is important to identify those patients who most need APRN services and ensure that they receive this care.

APRN roles require considerable autonomy and authority to be fully enacted. Practice settings have not always structured APRN roles to allow sufficient autonomy or accountability for achievement of the patient and system outcomes that are expected of advanced practitioners. It is equally important to emphasize that APRNs have expanded responsibilities—expanded authority for practice requires expanded responsibility for practice. APRNs must demonstrate a higher level of responsibility and accountability if they are to be seen as legitimate providers of care and full partners on provider teams responsible for patient populations. This willingness to be accountable for practice will also promote consumers’ and policymakers’ perceptions of APRNs as credible providers in line with physicians.