Guidance and Coaching

Eileen T. O’Grady, Jean E. Johnson

“Always bear in mind that your own resolution to succeed is more important than any other.”

∼ Abraham Lincoln

This chapter defines guidance and coaching as advanced practice registered nurse (APRN) competencies that are at the heart of nursing and are an effective means to engage patients in change leading to healthier lives. Since researchers first identified the teaching–coaching function of expert nurses and APRNs, guidance and coaching by APRNs have been researched and integrated into APRN competencies and described through case studies and other writings about APRN practice (Benner, 1984; Benner et al., 1999; Fenton & Brykczynski, 1993; Hayes & Kalmakis, 2007; Ross et al., 2018).

The American Association of Colleges of Nursing (AACN) The Essentials: Core Competencies for Professional Nursing Education (2021) have re-envisioned a model of nursing education that is built on 10 domains of nursing practice and incorporates four spheres of knowledge:

1) disease prevention/promotion of health and well-being, which includes the promotion of physical and mental health in all patients as well as management of minor acute and intermittent care needs of generally healthy patients; 2) chronic disease care, which includes management of chronic diseases and prevention of negative sequela; 3) regenerative or restorative care, which includes critical/trauma care, complex acute care, acute exacerbations of chronic conditions, and treatment of physiologically unstable patients that generally requires care in a mega-acute care institution; and, 4) hospice/palliative/supportive care which includes end-of-life care as well as palliative and supportive care for individuals in long term care or those with disabling conditions, complex chronic disease states, and those requiring rehabilitative care.

(AACN, 2021, p. 6).

The Essentials identify competencies and the subcompetencies address the advanced and entry-level nursing education. There is a strong focus in the updated Essentials on patient-centered care and the emphasis on communication that strongly supports guidance and coaching competencies for APRNs throughout the domains.

This chapter will include guidance and coaching competency-building to effectively engage and build trust in the APRN–patient relationship. The theoretical and research basis of guidance and coaching provides the foundation for relationship competencies that include communication, presence, nonjudgmental thinking, empathy, partnership mindset, and conflict management skills (Johnson et al., 2022). Situations appropriate for guiding patients and those appropriate for coaching patients are emphasized. Foundational skills of the coaching methodology are discussed, and guidance and coaching skills will be contrasted. Integrative health care, often linked with guidance and coaching, is not fully covered in this chapter; rather, a thorough discussion explores the relational skills needed across all four APRN roles. (See Chapter 6 for a discussion of integrative therapies in APRN practice.)

WHY GUIDANCE AND COACHING?

Guidance and coaching are effective in facilitating behavior change for patients to lead healthier lives. APRNs are most likely to use both guidance and coaching as an integrated model to help patients gather the motivation necessary to engage in change. The “why” of guidance and coaching is to engage patients in their own care, to prevent and/or effectively manage chronic illness, and to keep patients as functional and healthy as possible throughout their life. Nursing care looks at the whole person in the context of their life. Guiding and coaching patients through important transitions and in the pursuit of behavior change or well-being is done through a whole-person lens.

Patient Engagement

There are many reasons why people are becoming more engaged in their health care: the ease of information access through the Internet, the shifting of costs of care to consumers, the heightened awareness of healthy behaviors leading to longer health spans, and an aging population with chronic illness insisting on living with the highest degree of independence and functionality possible. Patient experience surveys focus on how patients feel about the care they receive, and for acute care institutions, payment add-ons or decrements depend on those patient experience results. Hibbard and Greene (2013) have shown that patients activated to engage in their care have better outcomes and lower costs.

Guiding and coaching patients requires patient activation and empowerment by placing the responsibility of the pursuit of health where it rightly belongs—with the patient. Information technology has advanced to support the activation and empowerment of patients by giving them critical health information. The Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act of 2010 in the United States provided the structures and requirements to make data about quality of care publicly available and enhanced patient-centered care through client-centered medical homes and healthcare financing models that empower patients. Health systems are continuing to design care that engages patients in their treatment, develops their abilities to manage their health and lowers their modifiable risks, helps them express concerns and preferences regarding treatment, empowers them to ask questions about treatment options, and builds strategic patient–provider partnerships through shared decision making (Chen et al., 2016). Recognizing patients as the source of control for their health requires building confidence, trust, and partnerships with patients rather than having healthcare providers simply tell patients what they need to do.

Burden of Chronic Illness

The current biomedical model of care does not work for lifestyle-related diseases. In the United States, 6 in 19 people have one chronic disease and 4 in 10 have two or more chronic illnesses (Centers for Disease Control [CDC], 2020). Heart disease, cancer, respiratory illness, and diabetes account for 71% of deaths worldwide (World Health Organization [WHO], 2020a). These diseases are costly and are the lead driver of healthcare costs that are amenable to prevention. These diseases are caused by four behaviors: tobacco, inactivity, poor nutrition, and excessive alcohol use (CDC, 2020). Helping patients change these behaviors will greatly decrease untold suffering, early mortality, and disability.

A startling statistic that represents opportunity for behavior change is the number of people who are obese tripled between 1975 and 2016, with over 340 million children and adolescents aged 5 to 19 overweight or obese in 2016 (WHO, 2020b). Of great concern is the 2019 estimate that 38.2 million children under the age of 5 were overweight or obese (WHO, 2020b). Overweight and obesity are generally preventable and present an impending disaster for worldwide health, for society, and for the global macroeconomy.

Chronic disease in the United States is estimated to cost $3.7 trillion a year, including direct and indirect costs, with a gross domestic product (GDP) of $21 trillion. This accounts for almost 20% of the US GDP (O’Neill-Hayes & Gillian, 2020). It is estimated that global GDP could increase 8% by 2040 if chronic illness were reduced through innovation and prevention of illness (Remes et al. 2020). Chronic illnesses cause billions of dollars in losses of national income and push millions of people below the poverty line each year. In the United States alone, chronic diseases attributable to lifestyle factors are responsible for 7 of 10 deaths each year, and they account for an estimated 90% of our nation’s healthcare costs, which in 2019 was $3.8 trillion (before the COVID-19 pandemic; Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, 2020). In addition, the increasing burden of preventable chronic diseases globally has made very clear the vulnerability of those with a chronic condition to COVID-19 and other acute health emergencies that have arisen (Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation, 2020).

As every APRN knows, lifestyle factors and behaviors can be modified to lessen the risk of chronic illness. People can reduce their chances of getting a chronic disease or improve their health and quality of life if they already have a chronic disease by making healthy choices. Liu et al. (2016) found that only 6.3% of US adults engaged in all five key health behaviors that can reduce their risk of chronic diseases: (1) avoiding alcohol consumption or only drinking in moderation, (2) exercising regularly, (3) getting enough sleep, (4) maintaining a healthy body weight, and (5) not smoking. These findings, based on nearly 400,000 adults aged 21 and older, showed that 1% failed to engage in any of the five health behaviors; 24% engaged in four, 35% engaged in three, and 24% engaged in two. As APRNs use their expertise to sharply focus on patients’ lifestyles, their value in the healthcare marketplace will be more fully realized.

GUIDANCE AND COACHING DEFINITIONS

Guidance and coaching are relational approaches that focus on helping a person create change in their life to advance individual autonomy, well-being, and goal attainment. Guidance is the act of providing information and direction, and coaching is an inquiry process to help patients set and achieve their own goals by using powerful questions rather than telling them what they need to do. APRNs are in a unique position to integrate these two approaches so that the focus is on the patient’s goals and APRNs provide targeted and highly individualized information for patients to make informed decisions. Understanding and integrating into practice the characteristics of guidance and coaching comprise a key APRN competency that is built on having trust and rapport with patients.

Guidance

Guidance is a broad term that means the provision of help, instruction, or assistance, and there are several forms of guidance. The distinguishing feature of guidance compared with coaching is that guidance requires the provision of advice or education, whereas coaching is an inquiry, an excavation of answers from a person. To guide is to advise, or show the way to others, so guidance can be considered the act of providing expert counsel by leading, directing, or advising. To guide also means to assist a person to travel through or reach a destination in an unfamiliar area. Guidance is best used in situations when a person has a perceived knowledge deficit in an area for which expert APRN knowledge can fill the void. When providing guidance, the APRN is serving as a knowledge source for the patient. Guidance can include laying out, simplifying, or integrating the options for a patient to make a healthcare decision. It is imperative that the APRN determine the patient’s level of knowledge before launching into guidance. Asking patients what they know about their condition is an important skill to respectfully build on what they know and make APRN guidance more powerful and effective. What follows are some common forms of guidance.

Anticipatory Guidance

Anticipatory guidance and teaching are particular types of guidance aimed at helping patients and families know what to expect. Anticipating common problems or symptoms and what to do about them can go a long way in reducing unnecessary care, promoting self-efficacy and reducing a patient’s anxiety. Anticipatory guidance is when the APRN informs the patient a priori about an expected health process that is likely to occur. For example, when a patient sustains a cervical hyperextension injury (whiplash) after a car accident and a fracture has been ruled out, the APRN informs the patient that the muscles surrounding the neck will become far more painful within 48 hours. She or he may explain that torticollis may ensue and that this is normal, temporary, and to be expected. The APRN offers remedies and guidelines on when to seek more assessment. Another example of anticipatory guidance is when a woman experiences a miscarriage and the APRN lets the patient know to expect very heavy blood loss that may alarm her. The APRN provides guidelines about when to seek additional care, offers reassurance, and anticipates that the patient may experience intense feelings of loss and grief.

Patient Education

Patient empowerment can be achieved by teaching patients about their illnesses/conditions and by guiding them to be more involved in decisions related to ongoing care and treatment. The WHO (2016) defines patient education more broadly as any combination of learning experiences designed to help individuals and communities improve their health by increasing their knowledge or influencing their attitudes. The goal of patient education is to produce change and promote self-care. Clinicians have long held the myth that if the patient is provided with the right information, the patient will see the wisdom of making change in their life to be healthier and simply follow the recommendations.

For APRNs it is essential to determine what a person wants to learn before launching into a teaching or “telling” expert role. Patients often come with an array of information from available websites and other sources. As information has become so readily available, patients are looking for customized wisdom and a broker of information to cut through the large amount of confusing, often conflicting, sources of knowledge. They want to know what information applies to them and how should they use it. (See Chapter 6 for further discussion of patient education.)

Coaching

Coaching is a broad umbrella term that encompasses different approaches, philosophies, techniques, and disciplines. Coaching is defined by the International Coaching Federation (ICF, 2020) as “partnering with clients in a thought-provoking and creative process that inspires them to maximize their personal and professional potential.” For APRNs this definition also extends to a health potential. The ICF (2020) identified four main domains of a coach’s responsibility which could apply to APRN practice:

- 1. Engages in foundational work that is based on ethical principles and a coaching mindset that is flexible, open, curious, and client centered.

- 2. Cocreates a relationship that is based on agreement about the relationship, plans, goals, and client accountability and creates trust and safety and maintains presence with the client.

- 3. Communicates effectively using deep listening and evokes client awareness.

- 4. Cultivates learning and growth.

The ICF definition and components of coaching provide significant leeway in the development of different philosophic approaches to coaching. Although there are common principles, there are different philosophies and schools of thought in the coaching sphere. One example is motivational coaching, based on a focused approach to explore and ignite motivation for change and address ambivalence. Another is integrative coaching, developed at Duke University to help patients make changes to lead healthier lives (Duke Integrative Health, 2020). Integrative coaching is intended to address the gap between medical recommendations and the patient’s success in implementing the recommendations. Each of these approaches has commonalities, including working toward change that is defined by the patient. In addition, there are different foci of coaching, such as health and wellness, executive, life transition, end of life, and attention deficit/hyperactivity coaching, to name a few. A meta-analysis on coaching by Sonesh et al. (2015) found wide-ranging impacts of coaching, including that coaching is an effective way to change patient behaviors and improve leadership skills, job performance, and skill development. Specific findings concluded that coaching:

- ■ Improves personal and work attitudes, including self-efficacy, commitment to the organization, and reducing stress.

- ■ Elicits a strong bond, which in turn facilitates joint goal setting and may be the mechanism through which goals are reached.

In addition, systematic reviews related to the more prevalent chronic conditions such as weight loss, type 2 diabetes, chronic obstructive lung disease, and cardiac risk factor reduction found health coaching reduces hospitalization and improves healthy behaviors (An & Song, 2020; Perez-Cueto, 2019; Long et al., 2019; Pirbaglou et al., 2018).

Coaching is based on a relationship in which the individual identifies their goals. It is founded on the recognition that the person seeking coaching is mentally healthy and has internal resources to deploy toward attaining their goals. The role of the coach is to work with that person in accomplishing those goals. The coach helps individuals clarify, define, reflect, and move forward. Coaching can be thought of as leading change from behind as well as walking with the patient (McLean, 2019). This concept clearly puts the individual in charge while the coach fully engages with the patient. A coaching partnership can last from a “spot” coaching session of one time to interactions over several years.

There is considerable discussion within coaching as to how much advice-giving should be offered. Because coaching is considered a partnership with a coach asking powerful questions, the APRN must trust that the person has their own answers that are true and right for them. However, working with patients to make change is different in that providers have specific health-related information that patients need and want. Providing that information is providing guidance within a coaching context. Combining coaching with guidance is essential to a complete provider–patient relationship. Table 7.1 differentiates guidance and coaching. It is important to note that coaching is neither counseling nor mentoring. The American Counseling Association defines counseling as “a professional relationship that empowers diverse individuals, families, and groups to accomplish mental health, wellness, education, and career goals” (Kaplan et al., 2014, p. 368). Counseling can be a very long-term relationship focused on helping individuals address their problems. Counseling is generally focused on psychological, social, or performance issues. The key distinction is that counseling is intended to “fix” a problem through gaining insight and advice from the counselor. Counseling as a technique operates from a problem-based approach as well as building on a person’s strengths. Psychiatric mental health nurse practitioners use all three modalities: counseling, coaching, and guidance.

Table 7.1

| Guidance | Coaching |

|---|---|

| Expert APRN has higher authority gradient | Power is shared |

| APRN is the expert | Patient is the expert/has the answers |

| Provides advice | Seeks understanding |

| Fixes problems | Builds on strengths |

| Expertise is valued | Curiosity is valued |

| Telling | Asking |

| Teaching | Inquiring |

| Anticipates | Explores |

| APRN leads/sets agenda | Patient leads/sets agenda |

Background of Nurse Coaching

Nurse coaching is aimed at working with individuals to promote their maximal health potential by integrating the skills of nursing and coaching. Professional nurse coaching can be defined as “a skilled, purposeful, results-oriented, and structured relationship-centered interaction with clients provided by a registered nurse for the purpose of promoting achievement of client goals” (Dossey et al., 2015, p. 3). Although this definition is specific to nursing and nursing care, it is consistent with the intent of the ICF definition. The American Holistic Nurses Credentialing Corperation (2020) has created momentum to integrate coaching into all registered nurse programs through the International Nurse Coaching Association (INCA), providing educational opportunities to become a nurse coach and certification as a coach. The texts The Art and Science of Nursing Coaching: The Providers Guide to the Nursing Scope and Competencies (Dossey et al., 2013), published by the American Nurses Association (ANA), and Nurse Coaching: Integrative Approaches for Health and Wellbeing (Dossey et al., 2015) provided the framework for the work of INCA. These works have been endorsed by the American Holistic Nurses Association.

Coaching has been explicitly integrated into several APRN practices, although the extent of APRN coaching is unknown. For example, Hayes and Kalmakis (2007) asserted that coaching is a critical component of a holistic care approach for nurse practitioners. Most midwives say that their practice incorporates coaching throughout the mother’s pregnancy and delivery (Rafferty & Fairbrother, 2015; Exemplar 7.1). There has long been the concept of a “labor coach” within midwifery. Clinical nurse specialists have worked within the areas of both consultant and coach (Goudreau, 2021). As coaches, they have worked with patients and family members to manage multiple chronic illnesses, especially around care transitions or a specific disease. Many clinical nurse specialists have roles that incorporate coaching when working with nurses to develop skills. A Certified Registered Nurse Anesthetist uses coaching to customize and personalize pain management or anesthesia to meet the patient’s stated goals and needs.

THEORIES AND RESEARCH SUPPORTING APRN GUIDANCE AND COACHING

There are numerous evidence-based theories and frameworks that inform the APRN guidance and coaching competency. These are deeply rooted in Florence Nightingale’s environmental theory and the science of human caring, which broadens and deepens the therapeutic use of self. In fact, the importance of the APRN-patient therapeutic relationship is foundational to the APRN guidance and coaching competency. Although there are many theories and models, we will note those that are important to informing and developing the APRN guidance and coaching competency.

Nightingale’s Environmental Theory

Florence Nightingale’s Notes on Nursing: What It Is and What It Is Not (1860) makes a strong link between a person’s environment and their health. Working with a person to manage their environment is the fundamental role of nursing, and as we experience a chronic illness epidemic in modern times, this observation still holds true. In fact, Nightingale built the foundation of nursing as a distinct profession on her observation that external factors associated with patients’ surroundings greatly affect their lives, their development, and their biologic and physiologic processes (Nightingale, 1860). This seminal conceptual thinking lies at the heart of modern APRN guidance and coaching.

Middle Range Theory of Integrative Nurse Coaching

A theoretical framework for nurse coaching has been developed by Dossey et al. (2015). They defined an integrative nurse coaching framework as “a distinct nursing role that places clients/patients at the center and assists them in establishing health goals, creating change in lifestyle behaviors for health promotion and disease management, and implementing integrative modalities as appropriate” (Dossey et al., 2015, p. 29). The authors identified five components of this model: “(1) Self-development (Self-reflection, Self-assessment, Self-evaluation, and Self-care); (2) Integral Perspectives and Change; (3) Integrative Lifestyle Health and Well-being; (4) Awareness and Choice; and (5) Listening with HEART (Healing, Energy, Awareness, Resiliency, and Transformation)” (Dossey et al., 2015, p. 29). Based on this theoretical framework, the ANA published a guide to nurse coaching competencies (Dossey et al., 2013). This model is patient directed, with the coach facilitating learning and decision making.

Transtheoretical Model

The transtheoretical model is an integration of several hundred psychotherapy and behavior change theories; hence the term trans (Prochaska et al., 2002). Using smokers as research subjects, Prochaska et al. (2002) learned that behavior change unfolds through a series of sequenced stages of change, which were not delineated in any of the existing multitude of theories. The transtheoretical model has been used successfully in many maladaptive lifestyle behaviors such as alcohol and substance abuse, eating disorders, anxiety/panic disorders, obesity, sedentary lifestyles, high-risk sexual behavior, and nonadherent medication use. This model is highly relevant to the APRN, who can tailor the intervention to the patient’s specific stage of change to maximize the likelihood that the patient will proceed through a needed change process. Providing specific knowledge about disease trajectories or prevention strategies and advice is overused and often counterproductive when it comes to motivating patients toward sustained lifestyle change. A thorough discussion on readiness for change and application of this theory is provided later in this chapter in Determining Patients Readiness for Change.

Watson’s Model of Caring

The theoretical framework for Watson’s model of caring is based on loving kindness. Her work has focused on the science of caring and moving from carative to caratas (“love”); that is, the process of relating to others in an authentically present way, going beyond the ego (Watson, 2020). The APRN would go beyond self-interest and ego to fully and spiritually integrate body, mind, and spirit. This model provides a strong feelings-based approach to coaching, recognizing the openness of spirit to another person as essential in a therapeutic relationship. Honoring and respecting the patient’s values, history, beliefs, autonomy, goals, and being are foundational in this model. It also requires self-reflection for the APRN to reach deep love and respect in a relationship. This includes, for example, being present to and supportive of the expression of positive and negative feelings, the creative use of self and using all ways of knowing, and assisting with basic needs with intentional caring consciousness (Watson, 2020). Ways of knowing are how knowledge comes to us and can include, for example, our experiences, senses, logic and reason, language, emotions, and imagination.

Positive Psychology

Positive psychology is the scientific study of the strengths that enable people to thrive. The field is founded on the belief that people want to lead meaningful and fulfilling lives, to cultivate what is best within themselves, and to enhance their experiences of love, work, and play (Positive Psychology Center, 2021). There are many notable positive psychologists, including Carl Rogers, Alfred Adler, Abraham Maslow, and Martin Seligman (2011) who built on their work and found five dimensions that lead to a flourishing life or a high degree of well-being. The five dimensions (PERMA) are as follows: Positive emotions are emotions that feel good. People who are flourishing feel positive emotions in a 3:1 ratio to negative emotions. These are not positive or optimistic thoughts; they are deeper full-body feelings of connection to others, to meaningful work or the feeling one gets with important accomplishments. Engagement, also known as flow is the state of being completely absorbed in an activity. It is the sweet spot between stress and boredom. People in this state are entirely absorbed in what they are doing and lose track of time while doing it. If a person is angry, anxious or depressed they are completely barred from this state. When people engage in these kinds of activities regularly they are able to withstand the hardships of life more effectively. Relationships are strong in people who are flourishing because other people matter and very little in life is positive that is solitary. People who are flourishing tend to have strong and positive relationships of many kinds from acquaintances all the way up to intimacy. Meaning and purpose is evident in those who flourish because what they do and what they engage in matters to them. They also feel that they belong to something that is larger than themselves. People who are flourishing have a strong sense of achievement that they’ve been practicing a craft, hobby or their work for years and have achieved some level of mastery in what they do (Seligman, 2011).These dimensions can be cultivated to build one’s capacity to flourish. The five dimensions of positive psychology are directly applicable to the APRN interacting with a wide range of people. In looking at the dimension of positive emotions as an example, Fredrickson (2001, 2020) significantly contributed to our understanding of how positive emotions can broaden a person’s momentary thought–action choices, which builds their enduring personal resources. This “broadening and building” suggests that the capacity to experience positive emotions may be a fundamental human strength central to human well-being. The APRN can facilitate a person’s positive psychology, especially in a guidance and coaching interaction, by promoting any or all of the five dimensions of well-being.

Growth Mindset

Dweck (2017), in her study of mindset and its impact on achievement, found that there are two types of belief systems. One is a growth mindset in which the individual believes they can learn and practice and achieve success. In addition, there is the belief that people with a growth mindset have a high degree of resilience. People with a fixed mindset believe they are endowed with talents that are fixed; they focus on documenting and defending their talent rather than developing skills. People with fixed mindsets delink talent from effort, acting on the belief that talent is a fixed, immutable entity. Fostering a growth mindset in the clinical space can create motivation and productivity, leading to improved outcomes. Guiding patients to shift from a hunger for approval (fixed mindset) to a passion for learning (growth mindset) by the tiniest degree can have a profound impact on nearly every aspect of life (Dweck, 2017).

Self-Determination Theory

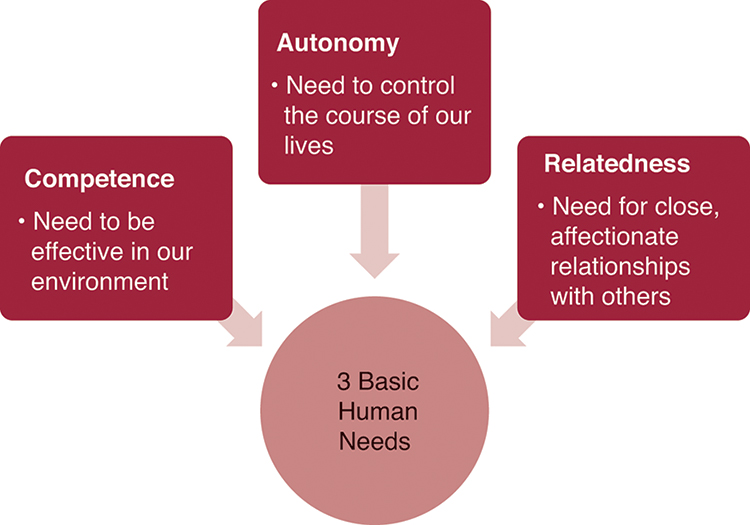

Ryan and Deci (2006) provided a framework for the understanding of human motivation and conditions that either promote or thwart it. The theory purports that there are two forms of motivation, intrinsic and extrinsic, and that all humans are motivated both by rewards (outside of ourselves) and by our interests, curiosity, and abiding values (inside). This framework offers three conditions that are associated with the level of a person’s motivation for engagement (Fig. 7.1). These three psychological needs have a robust impact on wellness (Ryan & Deci, 2006).

This framework is directly applicable to the APRN guidance and coaching competency because the APRN can promote the environment that supports competence, autonomy, and human relatedness (Exemplar 7.2). When these three needs are satisfied, enhanced self-motivation and health follow; when thwarted, motivation and well-being are diminished. Placing high value on positive regard, warmth, and giving patients as much psychological freedom as possible will lead to more engaged patients and better health outcomes (Ryan & Deci, 2000).

Transitions in Health and Illness

Guidance and coaching assists patients with a variety of life experiences in order to reduce healthcare costs and increase quality of care (Naylor et al., 2011). Early work by Schumacher and Meleis (1994) remains relevant to the APRN guidance and coaching competency and contemporary interventions, often delivered by APRNs, designed to ensure smooth transitions for patients as they move across settings (e.g., Aging and Disability Resource Centers, 2011; Coleman & Berenson, 2004; Coleman & Boult, 2003).

Schumacher and Meleis (1994) defined the term transition as a passage from one life phase, condition, or status to another: “Transition refers to both the process and outcome of complex person-environment interactions. It may involve more than one person and is embedded in the context and the situation” (Chick & Meleis, 1986, pp. 239–240).

Transitions have been characterized according to type, conditions, and universal properties. Schumacher and Meleis (1994) proposed four types of transitions: developmental, health and illness, situational, and organizational. Developmental transitions are those that reflect life cycle transitions, such as adolescence, parenthood, and aging. Health and illness transitions require not only adapting to an illness but more broadly reducing risk factors to prevent illness, changing unhealthy lifestyle behaviors, and numerous other clinical phenomena. Situational transitions are most likely to include changes in educational, work, and family roles. These can also result from changes in intangible or tangible structures or resources (e.g., loss of a relationship or financial reversals; Schumacher & Meleis, 1994). Organizational transitions are those that occur in the environment: within agencies, between agencies, or in society. They reflect changes in structures and resources at a system level.

Developmental, health and illness, and situational transitions are the most likely to lead to clinical encounters requiring guidance and coaching. Successful outcomes of guidance and coaching related to transitions include subjective well-being, role mastery, and well-being of relationships, all components of quality of life (Schumacher & Meleis, 1994).

This description of transitions as a focus for APRNs underscores the need for and the importance of incorporating guidance and coaching into the APRN–patient therapeutic partnerships.

BUILDING RELATIONSHIPS FOR APRN GUIDANCE AND COACHING

In order to effectively work with patients to create healthy life changes, APRNs will engage in both guidance and coaching. Effectiveness of guiding and coaching is based on the quality of the relationship between the APRN and patient. Trust is essential to the relationship, and Johnson et al. (2021) have identified six competencies critical to building a trusting relationship; being present, communicating effectively, being nonjudgmental, being empathic and compassionate, managing conflict, and partnering with patients. Even though the competencies noted in this section are part of basic nursing care, the following discussion of skills is described within the context of APRN guidance and coaching. Note that there is considerable interaction among the skills—they are interdependent and should be part of every APRN toolbox.

Presence

How well honed is your ability to be present? Thich Nhat Hah (2015), a Buddhist philosopher, said, “The most precious gift we can give others is our presence.” In a guiding or coaching relationship, presence is not only a gift but a prerequisite to being a full partner. The ICF defines coaching presence as the “ability to be fully conscious and create [a] spontaneous relationship with the client, employing a style that is open, flexible and confident” (ICF, 2016). This definition uses the words “fully conscious”; others may use the words “fully aware” or “mindful.” Some people equate the words “mindful” and “presence.” A definition of mindfulness noted by Kabat-Zinn (2017, para. 2) is “mindfulness means to purposefully pay attention in the present moment with a sense of acceptance and nonjudgment.” The commonality of both definitions is paying attention and being fully conscious. Presence requires mindfulness and mindfulness requires presence.

There are two common pitfalls to being present that relate to APRNs: external distractions/interruptions and the well-honed ability to anticipate what the patient needs. We are often physically present, but our minds tend to jump from one thought to another. When we are with a patient, we may be thinking about the patient we just saw, our frustration with one of our colleagues, or getting our child to basketball practice. When we take the time to be aware of what we think during a patient visit, we may be astounded by how many thoughts unrelated to the patient enter our mind.

In addition to the challenges of our work environment, we have deeply rooted ways of thinking as nurses and APRNs to anticipate patient problems. (See Chapter 6 for a discussion on thinking errors in practice.) We have been taught that we need to have answers for problems so we can fix a problem and thereby fix a patient. We think ahead of what we hear from the patient. Once we start anticipating, we have stopped being present. We need to slow our thinking and follow what the patient is saying. This is a fundamental challenge to the APRN: the art of coaching is to develop the ability to set aside distractions—including jumping ahead in problem solving, which often leads to misdiagnosis and care that is not patient-centered—and engage fully in the moment with the patient.

Presence can be enhanced through practice with the following tools:

- ■ Review patient information before seeing the patient, not when you are initially with the patient.

- ■ Situate yourself at eye level when possible, to maximize eye contact.

- ■ Recognize the patient’s feelings—without this recognition, trust will be limited.

- ■ If looking at or entering data into a device, invite the patient to look at the data with you.

- ■ Use the STOP method that was developed by Jon Kabat-Zinn (2020, para. 3) to refocus and be present:

- ■ S: Stop. Stop what you are doing and pause momentarily.

- ■ T: Take a breath. Take a deep breath or several. Deep breathing can anchor you to the present moment.

- ■ O: Observe. Notice what is happening both outside and inside of yourself. Where has your mind gone? What do you feel? What are you doing?

- ■ P: Proceed. Continue doing what you were doing or, using the information gained during this check-in, change course.

Communication

Communication encompasses all forms, including verbal (words and tone), written, and body language. Synthesis of all forms of communication must be used by the APRN to determine a patient’s health status. This includes what the patient understands, how they want to engage, and their style of communication. Of all of the skills that are inherent to effective communication, the most important is listening. We listen every day. It is part of our ability as human beings (as long as our hearing is anatomically and physiologically intact). However, how often are we thinking of other things when someone is talking to us? Are we looking at the patient or at the computer screen to review lab results? We intend to give our attention to the patients we serve, but there is so much work to do and so many patients to see. Every aspect of guidance and coaching has to do with highly skilled listening: listening for energy, what the person wants or needs, resistance, choices made, and how choices move toward or away from goals. Coaching in particular requires that patients do most of the talking, with the APRN doing most of the listening. We cannot adequately guide patients or do anticipatory teaching without knowing what the person already understands.

Rachel Naomi Remen (1996) is a pioneer of relationship-centered care and noted, “The most basic and powerful way to connect with another person is to listen. Just listen. Perhaps the most important thing we give to each other is our attention” (p. 143). Listening is a foundational skill to both guidance and coaching and in any relationship. Listening is the process of understanding others and establishing trust in the relationship. Trust is the foundation of the APRN–patient therapeutic relationship. We can only understand a person’s level of health literacy if we listen deeply.

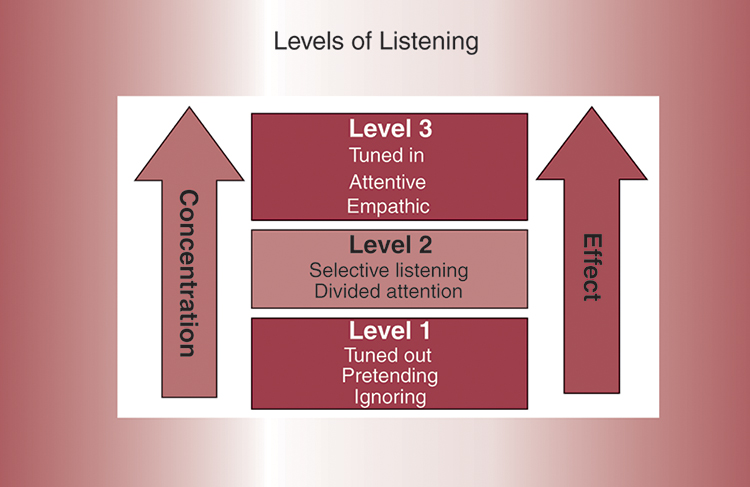

There are several different taxonomies of listening. A useful classification described by Whitworth and colleagues (2007) includes three levels of listening (Fig. 7.2). The level 1 listener is tuned out, either ignoring the person talking or pretending to listen. This level is also referred to as internal listening, where the listening is all about the listener. Level 2 listening is selective, with the listener sometimes focusing but at times being distracted by his own inner dialogue. Level 2 listening has a sharper focus on the other person than level 1. In level 3, the APRN becomes a mirror in which the information is reflected back. This listening is collaborative, empathic, and clarifying. The APRN is unattached to their agenda and own interests. Level 3 is empathic listening, representing the highest level, in which the listener gives time and attention to listening and gives their full self. Empathic listening is not only hearing what is said but also understanding the words, emotions, and meaning. It is considered “deep” listening or listening with the heart. Deep listening is hearing what is not said and includes tone of voice and nonverbal expressions. It is a global form of listening, in which one is using all of the senses to listen, noticing gestures, the action, inaction, and interaction. It requires the APRN to be very open and softly focused without an agenda or judgment of any kind. Level 3 listening is often described as a force field with invisible radio waves in which only the skilled listener can receive the information, often unobservable to the untrained listener (Whitworth et al., 2007). Guiding and coaching require level 3 listening in order to fully engage with the patient’s baseline knowledge, goals, actions, and emotions. Suggestions for levels 2 and 3 listening are the following:

- ■ Stop talking!

- ■ Relax for a minute prior to engaging with a patient by deep breathing, visualizing a pleasant memory that triggers relaxation.

- ■ Review the health record prior to beginning a dialogue.

- ■ Remove distractions and potential interruptions and clear your head of intruding thoughts.

- ■ Listen for the tone of the conversation as well as the words.

- ■ Acknowledge what is said by reflecting and probing further.

- ■ Ask powerful questions (Table 7.2).

Literature reflecting the benefits of deep listening includes patient satisfaction with care, enhanced patient engagement in care planning, and improved health outcomes (Wentlandt et al., 2016). Listening is the most critical skill for APRNs, as discussed in Chapter 6. There is no guidance or coaching without deep listening.

Table 7.2

| If your life depended on taking action, what would you do? |

| What’s the takeaway from this? |

| What are three other possibilities? |

| If you could wave a magic wand, what would you do? |

| What resources do you need? |

| How could you use your strengths in this situation? |

| How will you know when you have achieved success? |

| What would happen if you don’t do anything? |

| What is this costing you? … What else is it costing you? |

| If you say “yes” to this [change], what are you saying “no” to? |

| What is the hardest part for you? |

| What does success look like to you? |

Nonjudgmental (Suspending Judgment)

Being completely accepting toward another person, without reservations, is a concept developed by the psychologist Carl Rogers. He proposed that each individual has vast resources to marshal for self-understanding and self-directed behavior, but an interpersonal climate of positive regard was necessary to facilitate this (C. Rogers, 1961). It is about accepting a person as they are without judgment and is the basis for patient-centered therapy.

Being judgmental means that we are unusually harsh or critical in disapproving, blaming, or finding fault in others. Often judgmentalism is steeped in our biases and closed-mindedness. When we hold negative opinions of others, it distorts our perceptions of other people and of ourselves. By judging others, we garner distorted feelings of power or righteousness over others. Being judgmental is associated with poor self-worth and self-esteem. Currently, more attention is being paid to implicit (unconscious) bias as a contributing factor in health disparities in the United States. One definition of implicit bias is “attitudes or stereotypes that affect our understanding, actions, and decisions in an unconscious manner” (Kirwan Institute, 2015). Everyone has implicit biases, and they are based not only on race, ethnicity, or religion but also on manner of dress, weight, gender, political views, religious practices, and other issues. And they may be based on how we perceive the behavior of a patient as a patient. Is the patient deferential? Are they personable? Are they a complainer?

A patient must feel physically and psychologically safe from being judged in order to fully engage in a relationship. We often take for granted that people seek health care and trust APRNs to do the best for them simply because we are credentialed healthcare providers. However, they often feel that they must “please us” rather than being honest about their concerns. Pleasing a provider is deeply rooted in patient behavior. Patients want their APRN to like them, so they may be afraid that the APRN will be angry or judgmental of them if they are challenging or have not adhered to a treatment plan, so they may tell APRNs what they think we want to hear. We often give subtle messages of greater acceptance when patients are “compliant” and of nonacceptance if they are not.

Suspending judgment does not mean we have to like every patient. Mearns (1994) noted that liking someone is based on shared values and complementary needs and is therefore conditional. However, it is especially important to be nonjudgmental for all patients and particularly for those we find most frustrating. Being nonjudgmental includes setting boundaries by creating clarity of expectations in the relationship. The concept of boundary awareness in coaching is founded on the initial work of Kerr and Bowen (1988) on self-differentiation within the context of family. In an APRN coaching relationship, there is a fine line between boundaries that are too tight and those that are too loose, and it can be a significant challenge to maintain a balance. To be more aware of boundaries, pay attention to situations in which you feel stressed. Reflect on the sources of stress and how you are establishing boundaries. Another exercise in clarifying boundaries is to be aware of feelings of resentment, discomfort, and/or guilt (Gionta & Guerra, 2015). If you experience these feelings within a patient relationship, it is time to focus on setting or resetting boundaries. Examples of boundaries include not tolerating hurtful behaviors (if the patient has the capacity to manage their behavior) or being treated disrespectfully as an APRN. APRNs need to establish their own set of boundaries and clarify and maintain them with their patients, families, and healthcare team.

There is an important difference between judgment and discernment. Discernment is differentiating between what is appropriate or inappropriate and is a conscious act. Judgmentalism is holding strong, often unconscious negative opinions of others involving little knowledge and fast thinking. If we are judging, it is nearly impossible to be truly helpful. TOME is a tool to practice being nonjudgmental:

- ■ Notice Triggers. Notice what triggers judgments and why. Understanding the triggers will enhance awareness of making judgments about patients.

- ■ Observe like a reporter. Look at your patients in as neutral a manner as possible. Look at them without placing your value set on them and explore their values and the meaning of health and/or illness to them.

- ■ Meditate. Meditation is a way of being aware of thoughts and questioning their origins and impact on patients.

- ■ Extend empathy. Every patient wants to be understood and have their APRN understand their situation and how they feel about their health or illness. Conveying empathy through acknowledging the patient’s feelings helps patients move through the change cycle.

Empathy and Compassion

Carl Rogers built on Maslow’s hierarchy of needs by adding that in order for a person to “grow,” they need acceptance, genuineness, and empathy. Rogers believed that each person can achieve their deepest desires in life and achieve self-actualization but that empathy helps foster that growth, just as a seed needs soil and water. His greatest contribution was likely in his study of accurate empathy and its role in the growth of humans. He described empathy as an underappreciated way of being and posited that accurate empathy is “being one with the patient in the here and now, being highly sensitive to their experience and their world” (C. Rogers, 1961, p. 34). He stressed that listening is not a passive endeavor, because active listening can bring about changes in people’s attitudes toward themselves. People who experience accurate empathy and are listened to in this way become more emotionally mature, more open, and less defensive (C. Rogers, 1961). There is increasing recognition and evidence that provider–patient relationships, the quality of their communications, and accurate empathy influence quality, safety, and health outcomes (Price et al., 2014).

Trzeciak et al. (2019) suggested in their book Compassionomics that empathy precedes compassion, that first you need to have empathy—the feeling of truly understanding another person—and then compassion, the action that results from empathy. In working with patients to create change, empathy and compassion are essential. Although empathy is woven into basic nursing, as we get pressed for time with interruptions, technology intrusions, and demands of patients, exhibiting empathy requires constant vigilance.

Although we accept empathy as an emotional state, there is growing understanding of the neurophysiology of empathy. Research beginning in the mid-1990s has identified neural networks of mirror neurons that may explain the capacity for empathy (Rizzolatti & Craighero, 2004). Mirror neurons are activated by both the action of an individual and the observation of a similar action performed by another (Lamm & Majdandzic, 2015; Preston & de Waal, 2002). It appears that mirror neural pathways extend to multiple structures in the brain based on the stimuli producing the effect. A possible explanation for empathy is that when we are listening to and looking at a patient, our mirror neurons are activated as if we are experiencing what the patient is doing or experiencing. With ongoing research into mirror neurons, there is great promise to better understand the neural activation that forms and supports relationships and how feelings are experienced. To expand empathy and compassion:

- ■ Audio-record a visit with a patient and reflect on the content of the visit.

- ■ Practice reflecting back to the patient your understanding of the feelings the patient may be experiencing. Be present and listen.

- ■ Acknowledge the emotional content of what the patient is saying.

- ■ Ask the patient how you can help them.

Managing Conflict

Conflicts may result from differences in ideas and values and when certain needs are not met. This could be the case if a patient feels disrespected in some way, frequently because of feeling not listened to or cared about. Conflict can range from a minor annoyance to significant hostility about some aspect of the patient visit. Examples include patients feeling a loss of control or when a treatment has not worked, they are not feeling understood/listened to, and/or they are fearful about their future. While preventing conflict with patients is preferable to managing a conflict, there will always be some conflict to manage in a healthcare situation. Suggestions for managing healthy conflict include:

- ■ Take a deep breath before responding. This will be calming and provide a moment to recognize the situation.

- ■ Never meet a feeling with a fact. Acknowledge the patient’s feelings. This all-important step deescalates highly charged encounters. Until intense emotions are acknowledged, there is little that will be accomplished in a patient visit. For example, if a patient comes into an exam room angrily saying that they were treated rudely by the receptionist, the APN must first recognize and notice that they are upset. By validating the patient’s feelings first, the conversation can move to a constructive dialogue.

- ■ Ask questions to understand the patient’s emotional landscape. Asking about how they are doing or feeling makes the well-being of the patient the priority (within a realistic boundary).

- ■ Maintain a respectful stance with the patient while working through the conflict.

- ■ Make sure they feel heard and understood. Provide a summary of the conflict and agreements to the patient before the patient leaves.

Partnership

There has been much written about the importance of APRNs creating healthcare partnerships with patients. APRNs are keenly aware of the potential power gradient between themselves and patients. However, each patient knows themselves better than any provider, including their fears, behaviors, and healthcare concerns. When partnering with patients, APRNs must see the patient as a full partner and expert on themselves. This approach greatly reduces the power gradient, with the patient having self-knowledge and APRNs having healthcare expertise. In addition, patients are becoming more knowledgeable, with healthcare expertise available online and with communities such as “Patients Like Me” that provide a forum for people to support each other with shared disease experiences and provide resources to manage their lives. The extent of the partnership also depends on the needs of the patients. For instance, individuals with an ear infection may simply want a limited interaction to confirm a diagnosis and get treatment. However, patients with a chronic or life-threatening illness will want to have a partnership to understand the diagnostics and treatment options. The nature of the partnership will differ with patients having differing expectations and capabilities for partnering. To foster a partnership relationship, consider these practices:

DETERMINING PATIENT READINESS FOR CHANGE

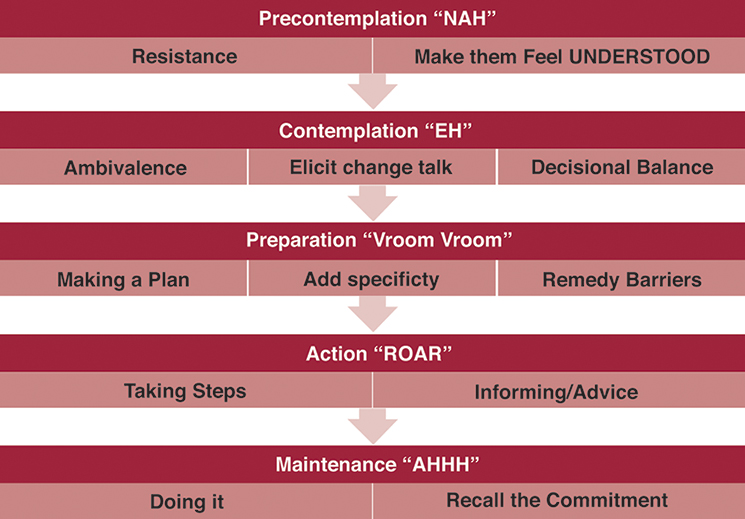

Guidance and coaching are the basis for promoting change in patients (Exemplar 7.3). The transtheoretical model of change noted above describes the change process that includes assessing the readiness of the patient to engage in change, preparation to make the change, taking action, and finally maintaining the change (Prochaska et al., 2002; Fig. 7.3).

Patient Readiness

In order to be coached, the patient must be functionally able, creative, and resourceful. Therefore most people in the general population are appropriate to receive/participate in coaching. If an APRN is considering using coaching, patients must first be deemed well enough to imagine a better future for themselves. Consequently, coaching will not be productive with people who cannot envision a different future. Explicitly, those who are severely mentally ill, psychotic, manic, severely depressed, suicidal, inebriated, obtunded, demented, or high or who are in a severe emotional state such as acute grief or trauma are not appropriate to engage in a coaching partnership. People with mental illness or in an acute intense emotional state are best engaged with empathy and guidance. A simple way to determine whether a person is coachable is to ask the individual to describe their life in the future, if everything went as well as it possibly could for them. If the person cannot articulate an answer, the APRN should not enter into a coaching dialogue but instead work with them to be able to envision a future healthier life.

After rapport has been established and some degree of empathy expressed, the APRN must determine the person’s readiness for change. The person’s stage of change in any given self-defeating lifestyle must be documented in the health record for the entire healthcare team to use and build on, measure progress, and guide interventions. Staging people is a necessary first step to any coaching encounter because it drives skilled conversations. Taking the time to assess where the person is in the change process and their willingness to be coached on any issue sets the stage for a deeper, more meaningful, and more effective encounter.

Resistance

When people are resistant, they are saying they will not change, they have no plans to change in the near future, or they are wholly not interested in changing. The main task for the APRN in working with people who are resistant to change is to help them feel understood. These interactions need not take a great deal of time, and the patient should leave the APRN with the feeling of being understood, that the APRN “gets me.” The challenge for the APRN is to see how the self-defeating patient activity serves a larger purpose in the patient’s life and to offer a partnership statement for the future, such as “I can see how smoking makes you feel like you are making your own decisions in your life and how important that is to you. If you ever want to quit, come back and I can work with you to quit.” Specific advice at this stage can drive resisters deeper into resistance; therefore it is harmful to offer advice and suggestions to patients in resistance.

Motivational Interviewing

Motivational interviewing (MI) is a way of communicating with patients to help them get past their resistance or ambivalence and move forward with change (Exemplar 7.4). By skillfully approaching those in resistance and contemplation with nonjudgmentalism and the freedom to choose how they want to live, we create an environment for them to be less defensive and more reflective. It is based on the early work of Miller and Rollnick (2013) from their experience working with individuals who had a drinking problem. The most recent definition:

MI is a collaborative, goal-oriented style of communication with particular attention to the language of change. It is designed to strengthen personal motivation for and commitment to a specific goal by eliciting and exploring the person’s own reasons for change within an atmosphere of acceptance and compassion.

(Miller & Rollnick, 2013, p. 29)

MI may be especially useful in working with patients who have mixed feelings about making a change, who have a low level of confidence, who don’t want to make a change, or for whom change is not important (Motivational Interviewing Network of Trainers, 2019). MI incorporates four fundamental processes that describe the back-and-forth and flow of a conversation. These processes are as follows:

- ■ Engaging: This is the foundation of MI. The goal is to establish a productive working relationship through careful listening to understand and accurately reflect the person’s experience and perspective while affirming strengths and supporting autonomy.

- ■ Focusing: In this process an agenda is negotiated that draws on both the patient and APRN’s expertise to agree on a shared purpose, which gives the APRN permission to move into a directional conversation about change.

- ■ Evoking: In this process the APRN gently explores and helps the person to build their own “why” of change through eliciting their ideas and motivations. Ambivalence is normalized, explored without judgment, and, as a result, may be resolved. This process requires skillful attention to the person’s talk about change.

- ■ Planning: Planning explores the “how” of change, where the APRN supports the person to consolidate commitment to change and develop a plan based on the person’s own insights and expertise.

Contemplation

APRNs most often see patients when they are in the contemplation phase. It is the place of ambivalence, where they both want to change but do not want to. They have one foot on the gas pedal and one on the brake. Advice at this stage can be harmful. Instead, the APRN can inquire about their personal motivators and bring forth the emotional conflict the person is experiencing. The APRN should approach the person in ambivalence with a neutral stance, without pushing. To determine their readiness for change, use questions such as “Why is this important? Why now? What if you did nothing and stay on this course—what is your future like in 10 years?” These powerful questions can move the person to identify personal motivators. The key task in this stage is to arouse emotions and encourage people to start talking about their ambivalence. These questions elicit change-talk in the patient.

Preparation

Once a patient moves to the preparation phase, they are ready to make a change. The ambivalence has dissolved. The task of the APRN is to identify barriers and develop remedies for these obstacles in partnership with the patient. With many life changes, it is important to set a start date and prepare the environment for change, such as finding an exercise partner or identifying impulse control techniques. Suggestions, gently offered, can be helpful in this stage as long as the APRN has no strong ownership in the person’s willingness to adopt a specific suggestion.

Action

Action is when the patient is actively engaged in making a lifestyle change. This stage is one in which direct advice and guidance is most helpful. Brainstorming on strategies to overcome obstacles and conversations on what to do in the event of a short-term lapse (a one-time reemergence of an unwanted behavior) or relapse (fully reverting back to prior behavior) are important. A common technique is to create “if … then” scenarios. For example, if a patient was working to reverse their type 2 diabetes and was excluding sugar from their diet, they might craft a plan that if they ingest sugar, then they get right back to avoiding sugar at the next meal. Anticipating setbacks and having remedies planned for lapses and relapses are crucial during the action stage (Krebs et al., 2018).

Maintenance

Maintenance often requires the APRN to acknowledge the patient’s success and to ask about how the patient holds themselves accountable, how they manage lapses, and what they would do if a relapse occurred. When a patient experiences a full relapse, they revert to consistently exhibiting old behaviors. The APRN must determine where the patient is in the cycle of change again (e.g., are they in resistance vs. contemplation, or are they back in action?). It is important for the APRN to approach change as a process and to be aware that having setbacks can be common for some people.

THE “FOUR As” OF THE COACHING PROCESS

According to J. Rogers (2016), coaching is a partnership of equals whose aim is to achieve speedy, increased, and sustainable effectiveness through focused learning on some aspect of the patient’s life. Coaching raises awareness and identifies choices, with the APRN and patient working from the patient’s agenda. Together they have the sole aim of closing the gap between performance and potential. A crucial first step is asking permission from each person prior to initiating a coaching conversation. For example, “You seem to be having a hard time taking your Lasix regularly. May I do some coaching with you on this?” Initiating a coaching and guiding conversation hands control almost entirely over to the patient.

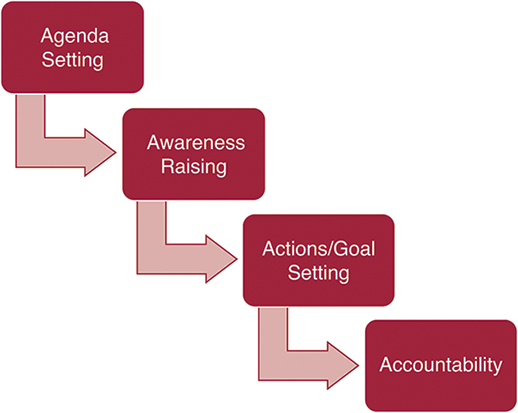

Coaching with guidance is a mindset that is integrated into every encounter with a patient or family member. Generally, there is a four-step sequenced coaching methodology—agenda setting, awareness raising, actions and goal setting, and accountability—with each step building on the previous step (Fig. 7.4 and Table 7.3).

Table 7.3

| Coaching Phase | APRN Skill | Powerful Questions |

|---|---|---|

| Agenda elicited | Excavate what is most meaningful

Clarify needs |

What is most important/meaningful/helpful to you at this time?

What do you need from our time together? |

| Awareness raised | Ask powerful questions

Shift consciousness Let the person do most of the talking Explore assumptions with curiosity Promote “generative moments” |

What are you not willing to give up?

If you say “yes” to X, what do you say “no” to? What is working well in this situation? Who do you need to become to make it happen? What do you want to see happen? What do you want to be held accountable for? What do you most value about yourself? What would your life be like if you were not [name limitation]? What is your deepest desire for yourself? |

| Actions/goal setting | Link raised awareness to specific goals to forward into action

Brainstorm Determine self-efficacy Challenge whether the person could do more (gently and once) |

What do you want to do and when do you want to do it?

On a scale of 1–10, how successful do you think you will be? What is going to get in your way? What is the remedy to that obstacle? Can I challenge you to … (do more)? |

| Accountability | Help person use resources, not pursue goals alone

Partner with supportive others Use technology Confirm agenda met |

How do you want to be accountable?

What will you do if you go off your plan? What is your “when–then” plan? Did you get what you needed today? |

Agenda Setting

Agenda setting, and the broader coaching methodology, requires handing over control and the choice of topic to the patient. The APRN elicits the agenda (the topic the patient wants to discuss) from the patient and the APRN and patient work together to address the patient’s agenda. Guidance can be useful in this stage by providing factual information that the patient can use in creating their agenda. For example, the APRN may say, “You have a lot of things going on with you and we have 15 minutes together today. What would be most useful for you to have accomplished with our time together?” Allow for silence, because this is a powerful question in and of itself. The patient may struggle with that question, and the APRN may need to ask more probing questions; however, the agenda must be specific, measurable, and within the patient’s control. Agendas cannot be centered around feelings or the actions of others. Acceptable agendas could include, “I need a plan for managing sugar cravings” or “I want to be able to manage the colostomy myself,” and unacceptable agendas are “I want to feel better” or “I want my wife to have more concern about my pain.” Eliciting and clarifying the agenda is a necessary and important step in the coaching process. If no agenda is determined by the patient, then no coaching can occur (Kimsey-House et al., 2011).

Focusing on the patient’s agenda is a sharp departure from what is typically provided by APRNs in the form of patient education because the encounter is entirely directed toward what the patient wants. The decisions each person makes, no matter how small, lead them toward (or away from) a life that is healthier. Thus at some level, the patient agenda is wrapped in the person’s fundamental values and truth.

Awareness Raising

Awareness raising requires challenging the patient’s mindset and assumptions about an issue with which they are struggling. It requires skillful inquiry in which the APRN adopts a highly curious approach to understand what and how the patient thinks about an issue. Awareness is raised by asking powerful questions (Table 7.2) that have likely never been asked of the patient and require deep reflection. This phase of coaching generally is the most time consuming. It can also be useful to incorporate guidance in the form of providing the patient information about their health concerns or interests as well as information about their health status. As the APRN builds coaching skills, it can be helpful to have five powerful questions that are used regularly to begin an inquiry. During the awareness phase, the APRN is using deep listening skills, watching for nonverbal messages. The APRN may become aware of the moment in which the patient has a major insight or makes new connections. The APRN can identify when awareness has been raised because there may be more silence and the patient will begin to identify changes they want to make.

Actions and Goal Setting

The APRN asks the patient what they want to do and when they want to do it. Goals flow directly from the awareness raised, which arouses emotions, and the patient has a higher degree of self-efficacy in pursuing the goal(s). If the patient seems stuck on developing a solution, the APRN can set up a brainstorming exercise in which the patient and APRN take turns coming up with a list of ideas/solutions. The key competency in brainstorming is to not allow the patient to judge the ideas until they are all laid out. Once the goals or actions are determined, the APRN must determine self-efficacy (the belief a person has in themselves to complete a task). The APRN asks, “On a scale of 1 to 10, how successful are you likely to be in doing this (10 = success)?” If the chosen number is less than 7, the goal must be modified. That is, the goal must be made less ambitious so that the patient has a self-efficacy score of at least a 7 in order for the patient to be positioned for success. Guidance may be useful here to help the patient define manageable goals and actions by providing information related to specific goals such as realistic lab measures for cholesterol or specific products available for smoking cessation.

Success breeds success, so as any adult embarks on a change process, it is important to have early successes. During this phase of the coaching, the APRN is letting the patient talk. The APRN may need to ask clarifying questions to make the patient’s goal more specific. If the APRN has a sense the patient could do more, they can challenge the patient. This skill is only used during the goal-setting phase and when the APRN thinks the patient could do more. For example, if the patient commits to ambulating down the hall once a day, the APRN can challenge them to do so three times a day. The patient will respond to the challenge in one of three ways: (1) agree to it, (2) reject it, or (3) modify it. It is crucial that the APRN accepts fully however the patient responds and challenges the patient no further.

Accountability

The final step in the coaching method is determined by the APRN asking, “How do you want to hold yourself accountable?” Ideally, it is best for the patient to rely on their own resources to achieve accountability, such as relatives, coworkers, or apps. The APRN could offer themselves as a way to hold a patient accountable, but it must not present any burden to the APRN. Accountability could be in the form of an email, text, or follow-up visit. It is important in this phase to have the patient outline a plan if the goals are not being met; this may include developing “when–then” strategies such as “When a week goes by and I haven’t done what I said I would, I will reschedule with you” (J. Rogers, 2016).

APRN PRACTICE PRINCIPLES FOR SUCCESSFUL GUIDANCE AND COACHING

Within the guiding and coaching process there are several important principles to keep in mind (Table 7.4). The following considerations are helpful, skillful ways for APRNs to approach patients by consistently bringing these principles to patient relationships.

Table 7.4

| Ask questions |

| Ask permission |

| Build on strengths |

| Support small changes |

| Be curious |

| Challenge |

| Get to the feelings |

Ask Questions

Perhaps the most important single change an APRN can do to move toward a coaching and guiding mindset is pause when you are going to tell a patient to do something. Do a self-check about whether it is an opportunity for coaching and ask a question instead. For example, replace “I see you are short of breath and that you need to take your diuretic every day” with “I see you are short of breath, and maybe uncomfortable. How can I best be helpful to you today?” In order to more fully engage patients in their self-care, asking questions places the patient in the driver’s seat, where they belong. It creates a psychological spaciousness for patients to feel and claim a sense of agency over their own care.

Ask Permission

Although nursing is a wonderful blend of science, technology, and caring, nurses have a strong drive to make people better, whatever the specific situation. APRNs have embraced the idea of holistic health care and are empathic with patients, but there continues to be an attitude that providers know what is best for patients. Integrating coaching into practice requires a culture shift and a change in personal philosophy and approach to caring for patients. To effectively integrate coaching into personal beliefs as well as the practice culture, there are many small actions that can support more effective APRN encounters. This can be difficult as the APRN is a clinical expert and knows the population so well, making it hard to resist telling others what and how to do things.

A crucial first step is asking permission from each person prior to initiating a coaching conversation. Asking permission, such as “Is it okay for me to explore this with you further?” is a way of respecting boundaries. Asking permission also demonstrates to the person that they have a choice and power in the relationship (Kimsey-House et al., 2011). If the patient decides against coaching, the APRN should move to providing guidance.

Build on Strengths

There is increasing recognition that building on patient strengths is a way for patients to gain confidence in their ability to change. The tendency in the past has been to focus on what is broken or not working or what an individual does not do well. This has supported the idea that the health issues a patient has are the result of not doing something or not doing something correctly, and that gap needs to be addressed. Rather than fixing what is broken, building on strengths can make the broken parts desiccate and shrink. For example, if a person has a great appreciation for excellence in their profession, that inherent skill can be applied to a weight loss journey by raising the quality of food they are ingesting or using love of learning to experiment with different strategies to manage their stress. An interprofessional summit was convened to identify that a major change that must occur in care delivery is to build on patient strengths to assist patients to achieve their goals (Swartwout et al., 2016).

The recent focus on building strengths is based on seminal research by Peterson and Seligman (2004), who demonstrated the benefit of assessing and using people’s strengths in making and sustaining change in a person’s life. There are years of research showing the benefits of building on strengths (VIA Institute on Character, 2016). The Classification of Strengths is an important tool that has been used in a growing body of evidence since the mid-1990s (Peterson & Park, 2009). This classification has six “virtues”: wisdom and knowledge, courage, humanity, justice, temperance, and transcendence. In addition, there are 24 characteristics within the overall classification (Table 7.5). Although the research has not been specific to health care, there are clearly applications to health promotion by assessing and then building on patients’ strengths for a healthier future.

Table 7.5

| Values in Action Classification of Strengths | |

|---|---|

| 6 Virtues | 24 Characteristics |

| Wisdom and knowledge | Creativity, curiosity, judgment, love of learning, perspective |

| Courage | Bravery, perseverance, honesty, zest |

| Humanity | Love, kindness, social intelligence |

| Justice | Teamwork, fairness, leadership |

| Temperance | Forgiveness, humility, prudence, self-regulation |

| Transcendence | Appreciation of beauty and excellence, gratitude, hope, humor, spirituality |

From Character Strengths and Virtues: A Handbook and Classification, by Peterson and M. Seligman, 2004, APA Press, p. 29–30.

Building on strengths has become an approach broadly used in health coaching. Confidence gained from building on strengths helps individuals not only to deploy those strengths toward achieving their goals but to also work on areas to be developed. Often people do not recognize their strengths, and the initial work of the APRN is to help the patient identify their strengths. There are strengths assessments available online that have strong validity profiles. One example is the VIA Survey of Character Strengths, which can be found at http://www.viacharacter.org/www/Character-Strengths-Survey. If there is no formal values in action (VIA) assessment, the APRN can help the patient recognize their strengths to build on by asking:

- ■ “Tell me about a challenge that you feel you successfully managed.”

- ■ “What would your friends and family say were the best parts about you?”

- ■ “What strengths helped you be successful?”

- ■ “How would you describe your strengths to create the change you want to make?”

APRNs can incorporate strength finding into any visit. Identifying strengths could take place during the history or physical examination. APRNs already respect, value, and engage with each patient, and identifying and building on their strengths will help in the APRN efforts to build capacity to relate well to patients.

Support Small Changes

Although big change is often desired, small changes are what create forward movement. Nearly everyone at some time has intentions to lead a healthier life by making adjustments in lifestyle. Each New Year, millions of resolutions fall by the wayside because we try to take big leaps to change behaviors and then realize a big leap is too difficult.

When coaching a patient, there is a tendency by both APRN and patient to jump to big interventions. Well-intentioned patients may want to initiate major interventions to manage their health, but they overestimate the change they can realistically make and sustain in their lives. Overestimating the ability to make lifestyle changes can then be demoralizing when the changes are not successful. Often, a patient will commit to making a change in order to please the APRN but cannot follow through.