Health promotion strategies should be a part of everyday nursing care. Education and coaching can be introduced informally as you provide care. To succeed, nurses must become aware of the individual needs of each patient, take time to develop a personalized teaching plan, and access materials to supplement their teaching. Some suggest that this should be a priority (

Bennett et al., 2020;

Pueyo-Garrigues et al., 2019). Communication for patient education is discussed in

Chapter 15.

Community-based interventions can be formally presented through patient education, screening programs, and social media. Choosing topics of interest to high-risk populations might include screening for disease common among certain population groups. Nurses can be influential in helping communities to create supportive health environments. For example, nurses can serve on health-related community advisory committees and provide relevant

discussions regarding care and funding. The provision of health fairs for area schools or community groups is another avenue nurses can use to support health promotion and disease prevention at the community level.

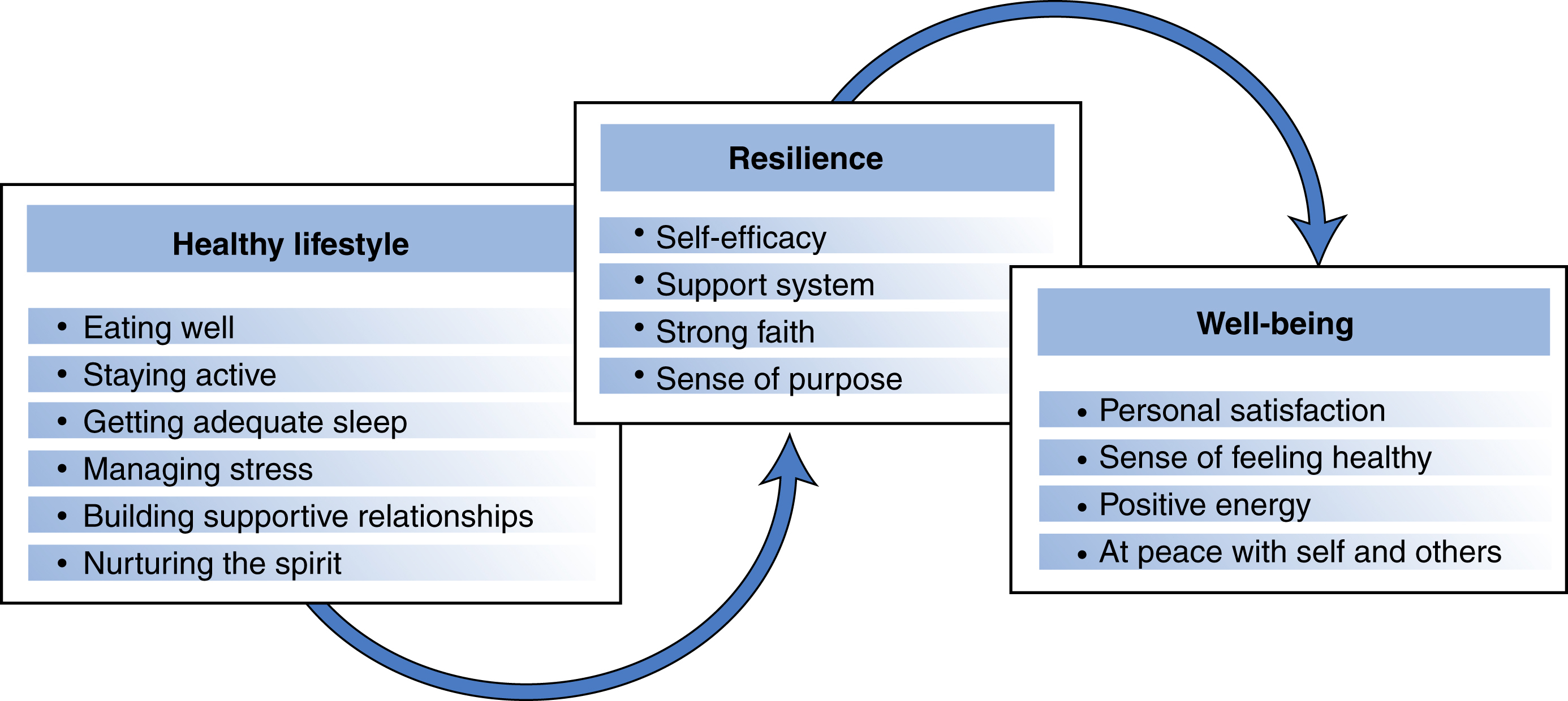

Common examples of general health promotion include developing a healthy lifestyle, good nutrition, regular physical activity, adequate sleep patterns, and stress reduction. But in addition to these desired outcomes, engaging in meaningful health promotion activities supports the development of patient autonomy, personal competence, and social relatedness.

Formal and informal instruction can focus on condition-specific topics. A wide variety of topics lend themselves to a health promotion focus. A sampling includes the following:

-

• Alcohol, nicotine, and other types of drug abuse prevention, including the DARE anti–drug use program presented in elementary schools

-

• Prevention, screening, and early detection of common chronic diseases such as human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), diabetes, cancer, heart disease, osteoporosis, and associated disorders

-

• The fall prevention strategies, especially for older adults

-

• Stress reduction for informal caregivers and organizational work sites

-

• Healthy dietary practices

-

• Regular exercise habits

-

• Developing effective support systems

Motivational Interviewing

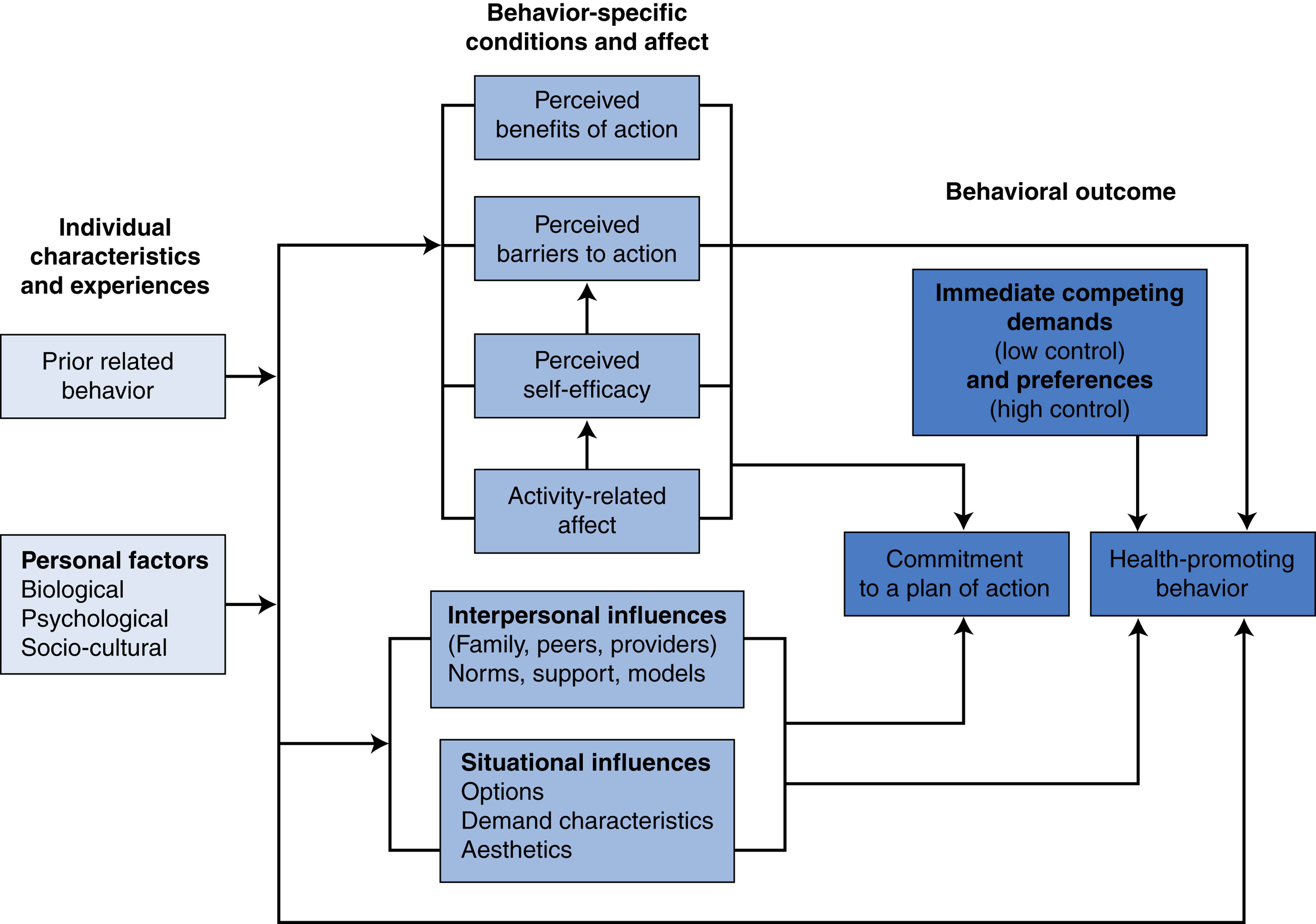

MI is “theoretically congruent” with the transtheoretical model of behavior change. A motivational intervention encompasses a patient’s values, beliefs, and preferences incorporated into relevant functional abilities and learned skills. Motivation is seen as a state of readiness rather than a personality trait. An overarching goal of individuals who need to improve their health is to develop a better health-related quality of life. To achieve this goal, people must want to change behaviors that compromise their health.

Treatment for many chronic diseases such as cancer, heart disease, asthma, diabetes, and arthritis often requires significant ongoing lifestyle changes. Patients are charged with taking a much more active role in designing and implementing the sometimes significant lifestyle changes that are required to live a purpose-filled life while coping with chronic illness. MI is a useful strategy in dealing with ambivalent patients who must make significant lifestyle changes.

The person must believe that success is “achievable” with his/her personal efforts and/or resources. The decision to change, the choice of goals, and the commitment to developing new behaviors is always under the patient’s control.

Readiness to change can be influenced. Nurses can better understand and influence a patient’s deeper perception of a problem through Socratic questioning. This type of questioning allows nurses to point to discrepancies between a patient’s goals or values and his or her current behaviors without argument or direct confrontation. MI helps patients address resistance and ambivalence about making health-related lifestyle changes in a nonjudgmental environment. Therapeutic strategies center on resolving problem behaviors, increasing committed collaboration, and joint decision-making.

Case Study

Mr White Wants to Be Discharged

Mr White: “I’m ready to go home now. I know once I get home, that I’ll be able to get along without help. I’ve lived there all my life and I know my way around.”

Nurse Brook: “I know that you think you can manage yourself at home. But most people need some rehabilitation after a stroke to help them regain their strength. If you go home now without the rehabilitation, you may be shortchanging yourself by not taking the time to develop the skills you need to be independent at home. Is that something important to you?”

MI is an intervention in which the nurse uses empathetic exploration to help a patient become aware of discrepancies in their behavior that are hurting their health and well-being. This exploration is coupled with teaching them new skills to achieve more healthy life goals.

Negotiating behavior change is conceptualized as a shared endeavor in which both patient and provider examine the patient’s potential and willingness to change destructive health behaviors. When motivational strategies match an individual’s readiness to change, this match increases the likelihood of positive intentional behavioral lifestyle changes.

There are two phases of MI. The first phase focuses on mutually exploring and resolving ambivalence to change as a collaborative endeavor. This is accomplished through weighing the pros and cons of the current situations and the actions one would have to take to make change possible. With the patient in charge of determining change activities, the second phase emphasizes strengthening and supporting the patient’s commitment to change based on the patient’s choice and capacity for change.

A good starting point is a simple introductory question, such as, “I wonder if you could tell me what you do to keep yourself healthy?” This type of question helps you to see what the patient values or even if he or she thinks about taking a personal role in achieving and maintaining healthy

behaviors. It also provides an opportunity to assess for possible issues that actually may be counterproductive, as in the Janet Chico case.

Case Study

Janet Chico

Janet is a 77-year-old woman with osteoporosis. She is health conscious and walks regularly to build bone strength. She wears a weighted vest to increase her workout strength and recently upped this weight to 15 pounds without consulting her physician. This change caused pain, and Janet was advised to decrease the weight. In this case, the concept of bone strengthening was appropriate, but its application had become inappropriate.

When a patient begins to tell you about his or her personal health habits, you can reflect on the relevant details and ask for clarification. The purpose of the dialog is to deepen the patient’s understanding. Use empathy in your responses. For example, “It sounds like you have been having a tough time and not getting a lot of support.”

Open-ended questions allow patients the greatest freedom to respond. Asking a patient if he regularly exercises may yield a one-sentence answer. Inviting the same patient to describe his activity and exercise during a typical day and what makes it easier or harder for him to exercise can provide stronger data. Potential concerns and inconsistency with values, preferences, or goals are more readily identified.

Patient and family perspectives on disease and treatment are not necessarily the same as those of their healthcare providers. For example, you may think that an emaciated or an obese woman would be worried about her weight and would want to modify it because she values the way she looks. On the other hand, her culture or family values and traditions may be in conflict with making significant behavioral changes. Until the patient can understand a health-related value for making a change, she will not put serious effort into doing so. This level of data allows nurses to tailor interventions based on the patient’s readiness to change and the availability of a support system.

As patients progress to the contemplative stage, nurses provide coaching guidance, information, and practical support to help them consider different choices and potential solutions. The pros and cons of each possible choice are explored. Empathy for the challenges faced by the patient and affirming the patient’s reflection process encourages patients to consider alternative options and to choose the most viable among them. A critical component of MI is acceptance of the patient’s right to make the final decision and the need for the clinician to honor the patient’s right to do so.

In the preparation stage, your role is to help patients establish realistic goals and develop a plan for achieving them. Goals should be realistic, patient-centered, and achievable. For example, the goal of losing 10 pounds in 3 months sounds more doable than a goal to simply losing weight (too vague) or losing 75 pounds (potentially overwhelming). Incremental goals build a sense of confidence, as the patient sequentially meets them.

Personalizing goals and treatment plans for your patients is critical. Each patient has a unique life situation, support system, and way of coping with problems. Unhealthy habits are cumulative and hard to break. Work with patients to monitor their progress, offering suggestions, revising goals or plans when needed, and reminding patients of progress made. It is useful to help patients proactively identify potential obstacles and to anticipate the next steps. You can offer additional suggestions, empathize or commend patient efforts, and revisit actions from the preparation stage if goals need revision. For example, you could say, “You have really worked hard to master your exercises” or “I’m really impressed that you were able to avoid eating sweets this week.” Availability to help patients solve problems or rethink plans, if needed, is also key.

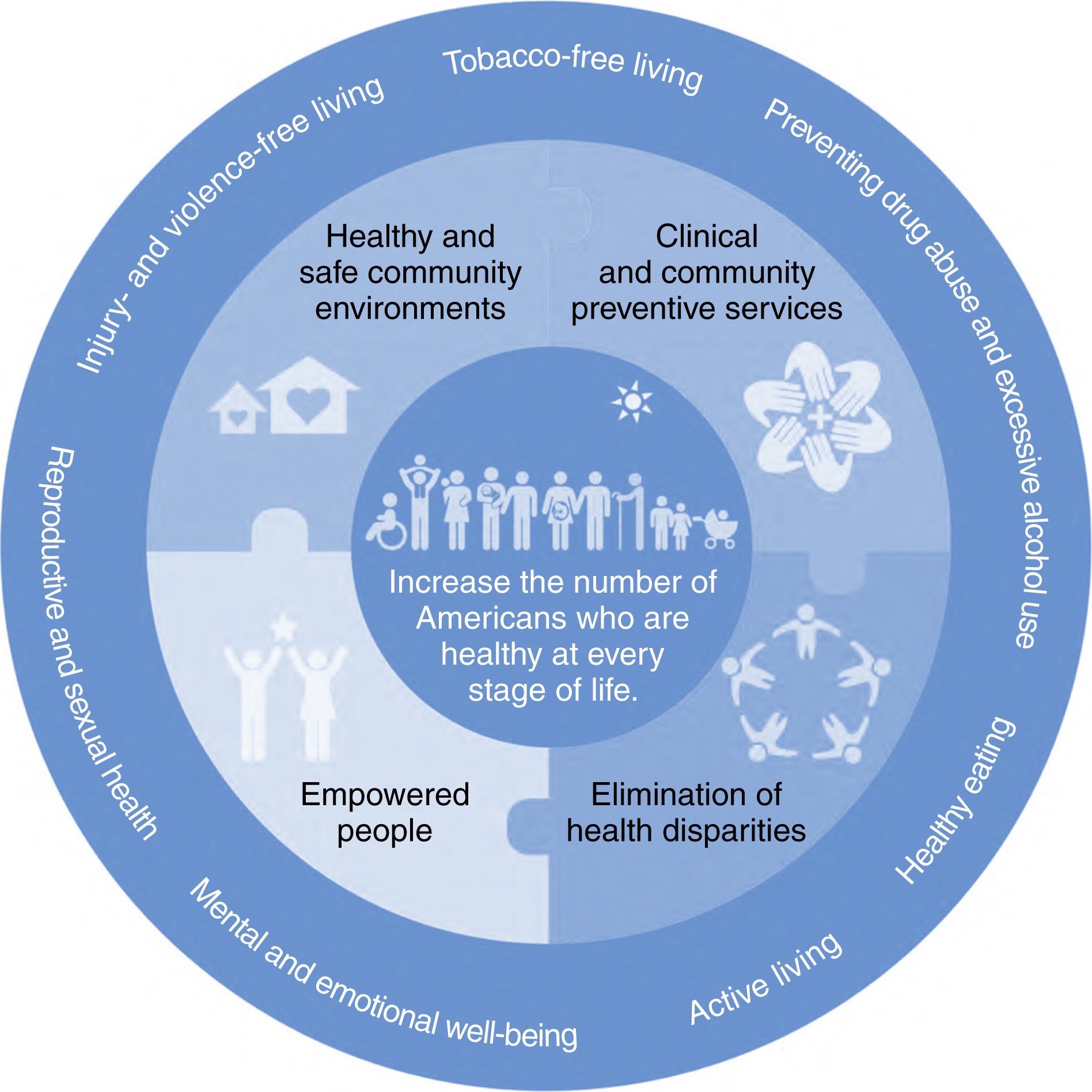

Health Promotion as a Population Concept

Community

is defined as a group of citizens that have either a geographic, population-based, or self-defined relationship and whose health may be improved by a health promotion approach. The community offers a natural social system with special significance for facilitating health promotion activities, particularly for people who are economically or socially disadvantaged. It is difficult to change attitudes and lifestyles to promote health when a patient’s social or economic environment does not support prevention efforts.

Successful community-based health promotion activities start with a community analysis of health issues identified by the community. Consciousness raising is critical, as engagement and buy-in of the community in which the activity is to take place is essential. The active participation of individuals, communities, and systems means a stronger and more authentic commitment to the establishment of the realistic regulatory, organizational, and sociopolitical supports that will be needed to achieve targeted health outcomes.

Box 14.2 presents health promotion strategies useful at the community level as well as with our individual patients.

Community empowerment seeks to enhance a community’s ability to identify, mobilize, and address the issues that it faces to improve the overall health of the community.

This type of empowerment is fueled by

both public policy and targeted education. Successful health promotion programs require individuals, groups, and organizations to act as active agents in shaping health practices and policies that have meaning to a target population. Specific interventions are designed to engage those people who are most involved as active participants in a common environmental concern related to health. Proactive social and political action to enhance health services can augment educational efforts to ensure program viability.

Box 14.2

Guiding Principles for Community Engagement

Before starting a community engagement effort

-

• Be clear about the purposes or goals of the engagement effort and the populations and/or communities you want to engage.

-

• Become knowledgeable about the community’s culture, economic conditions, political and power structures, norms and values, demographic trends, history, and experience with the efforts by outside groups to engage it in various programs. Learn about the community’s perceptions of those initiating the engagement activities.

For engagement to occur, it is necessary to

-

• Go to the community, establish relationships, build trust, work with the formal and informal leadership, and seek commitment from community organizations and leaders to create processes for mobilizing the community.

-

• Remember and accept that collective self-determination is the responsibility and right of all people who are in a community. No external entity should assume it can bestow to a community the power to act in its own self-interest.

For engagement to succeed,

-

• Partnering with the community is necessary to create change and improve health.

-

• All aspects of community engagement must recognize and respect the diversity of the community. Awareness of the various cultures of a community and other factors of diversity must be paramount in designing and implementing community engagement approaches.

-

• Community engagement can be sustained only by identifying and mobilizing community assets and strengths and by developing the community’s capacity and resources to make decisions and take action.

-

• Organizations that wish to engage a community as well as individuals seeking to effect change must be prepared to release control of actions or interventions to the community and be flexible enough to meet the changing needs of the community.

-

• Community collaboration requires long-term commitment by the engaging organization and its partners.

From Clinical and Translational Science Awards (CTSA) Consortium and Community Engagement Key Function Committee Task Force on the Principles of Community Engagement (2011).

Principles of community engagement (2nd ed., pp. 46–52). NIH Publication No. 11–7782. Washington, DC: National Academies Press. Retrieved from

http://www.atsdr.cdc.gov/communityengagement/pdf/PCE_Report_508_FINAL.pdf.

Health promotion activists recognize the community as their principal voice in promoting health and well-being. Health promotion represents a multidisciplinary approach, also inclusive of health education, public health, and environmental health. Health promotion strategies are relevant in clinics, schools, communities, and parishes; they can be introduced during many aspects of routine care in hospitals.

PRECEDE–PROCEED Model

The PRECEDE–PROCEED model is a community education structural framework for designing, implementing, and evaluating community-based health promotion. Developed by

Green and Kreuter (2005), this model consists of two components. The PRECEDE dimension refers to the assessment and planning components of the program. The acronym PRECEDE stands for the predisposing, reinforcing, and enabling factors contributing to the educational/organizational diagnosis, which are directly addressed in the proceed component. Behavioral factors that can affect the success of the PRECEDE–PROCEED model are presented in

Table 14.2.

Nurses also determine population needs and establish evaluation methods in the PRECEDE phase. Evaluation is a continuous process that begins when the program is implemented and is exercised throughout the educational experience. Sufficient resources, knowledge about target populations, and leadership training are part of an essential infrastructure needed to support health promotion approaches in the community.

A sustainable educational model needs political, managerial, and administrative supports for full implementation of a community-based approach to health promotion and disease prevention. Green later added the PROCEED component (policy, regulatory, organizational constructs in educational and environmental development). This component considers critical environmental and cost variables such as budget, personnel, and critical organizational relationships as part of the implementation phase. Having resources in place and assessing their sustainability is important in successful health promotion programs, although it is not always thought through in the planning phase. Components of the PRECEDE–PROCEED model are presented in

Table 14.3.

Table 14.2

PRECEDE–PROCEED Model: Examples of PRECEDE Diagnostic Behavioral Factors

| Factors |

Examples |

| Predisposing factors |

Previous experience, knowledge, beliefs, and values that can affect the teaching process (e.g., culture and prior learning) |

| Enabling factors |

Environmental factors that facilitate or present obstacles to change (e.g., transportation, scheduling, and availability of follow-up) |

| Reinforcing factors |

Perceived positive or negative effects of adopting the new learned behaviors, including social support (e.g., family support, risk for recurrence, and avoidance of a health risk) |

As with all types of education and counseling, learners need to be actively engaged in goal setting and developing action plans that have meaning to them. The healthcare system is complex and requires a new level of patient decision-making.

Choosing the right strategies requires special attention to the learner’s readiness, capabilities, and skills.

Box 14.1 presents strategies in health promotion counseling. Evaluation of health promotion activities is essential. In addition to evaluating immediate program effects, longitudinal evaluation of the impact of health promotion activities on morbidity, mortality, and quality of life is desirable. Keep in mind that what constitutes quality of life is a subjective reality for each patient and may differ from person to person.