The History of Mental Health Care

http://evolve.elsevier.com/Morrison-Valfre

Upon completion of this chapter, the student will be able to:

- 1. Develop working definitions of mental health and mental illness.

- 2. List three major factors believed to influence the development of mental illness.

- 3. Describe the role of the Church in the care of the mentally ill during the Middle Ages.

- 4. Compare the major contributions made by Philippe Pinel, Dorothea Dix, and Clifford Beers to the care of people with mental disorders.

- 5. Discuss the effect of World Wars I and II on American attitudes toward people with mental illnesses.

- 6. State the major change in the care of people with mental illnesses that resulted from the discovery of psychotherapeutic drugs.

- 7. Describe the development of community mental health care centers.

- 8. Discuss the shift of patients with mental illness from institutional care to community-based care.

- 9. Evaluate how congressional actions have affected mental health care in the United States.

Key Terms

catchment (KĂCH-mĭnt) area (p. 7)

deinstitutionalization (dē-ĭn-stĭ-TOO-shәn-lĭ-ZĀ-shәn) (p. 7)

demonic exorcisms (dē-MŎN-ĭk ĔK-sŏr-sĭs-әms) (p. 2)

electroconvulsive therapy (ē-lĕk-trō-kŏn-VŬL-sĭv THĔR-ә-pē) (ECT) (p. 6)

health-illness continuum (cŭn-TĬN-ū-әm) (p. 1)

humoral (HŪ-mŏr-ăl) theory of disease (p. 2)

lobotomy (lŏ-BŎT-ә-mē) (p. 6)

lunacy (LOO-nә-sē) (p. 3)

mental health (MĒN-tăl) (p. 1)

mental illness (disorder) (DĬS-ŏr-dĕr) (p. 1)

psychoanalysis (sī-kō-ă-NĂL-Ĭ-sĭs) (p. 6)

psychotherapeutic (SĪ-kō-THĔR-ә-PŪ-tĭk) drugs (p. 6)

trephining (tre-PHIN-ing) (p. 2)

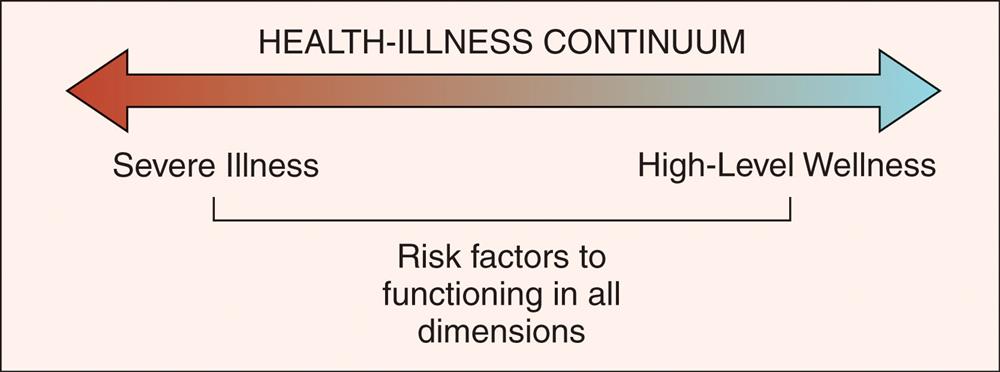

Mental/emotional health is interwoven with physical health. Behaviors relating to health exist over a broad spectrum, often referred to as the health-illness continuum (Fig. 1.1). People who are exceptionally healthy are placed at the high-level wellness end of the continuum, while severely ill individuals fall at the opposite end. Most of us, however, function somewhere between these two extremes. As we meet with the stresses of life, our abilities to cope are repeatedly challenged, and we strive to adjust in effective ways. When stress is physical, the body calls forth its defense systems and wards off illness. When stress is emotional or developmental, we respond by creating new (and hopefully effective) behaviors.

Mental health is the ability to “cope with and adjust to the recurrent stresses of living in an acceptable way” (Mosby, 2013). Mentally healthy people successfully carry out the activities of daily living, adapt to change, solve problems, set goals, and enjoy life. They are self-aware, directed, and responsible for their actions. Mentally healthy people are able to cope well.

Mental health is influenced by three factors: inherited characteristics, childhood nurturing, and life circumstances. The risk for developing ineffective coping behaviors increases when problems exist in any one of these areas. If behaviors interfere with daily activities, impair judgment, or alter reality, an individual is said to be mentally ill. Simply, a mental illness (disorder) is a disturbance in one’s ability to cope effectively. There is a rich history with examples of changing attitudes toward people with mental health problems.

Early Years

Illness, injury, and insanity have concerned humanity throughout history. Physical illness and injury were easy to detect with the senses. Mental illness (insanity) was something different—something that could not be seen or felt—and therefore it was feared.

Primitive Societies

Although the historical record is vague, it can be assumed that some care was given to sick people. Early societies believed that everything in nature was alive with spirits, and illness was thought to be caused by the wrath of evil spirits. Therefore, people with mental illnesses were thought to be possessed by demons or the forces of evil.

Treatments for mental illness focused on removing the evil spirits. Magical therapies made use of “frightening masks and noises, incantations, vile odors, charms, spells, sacrifices, and fetishes” (Kelly, 1999). Physical treatments included bleeding, massage, blistering, inducing vomiting, and the practice of trephining—cutting holes in the skull to encourage the evil spirits to leave. Mentally ill individuals were allowed to remain within society as long as their behaviors were not disruptive; severely ill or violent members of the group were often driven into the wilderness to fend for themselves.

Greece and Rome

Superstitions and magical beliefs dominated thinking until the Greeks introduced the idea that mental illness could be rationally explained through observation. The Greeks incorporated many ideas about illness from other cultures. By the 6th century bce, medical schools were well established. The greatest physician in Greek medicine, Hippocrates, born in 460 bce, was the first to base treatment on the belief that nature has a strong healing force. He felt that the role of the physician was to assist in, rather than direct, the healing process. Proper diet, exercise, and personal hygiene were his mainstays of treatment. Hippocrates viewed mental illness as a result of an imbalance of humors. Each of the fundamental elements—air, fire, water, and earth—had a related humor or part in the body; an overabundance or lack of one or more humors resulted in illness. This view (the humoral theory of disease) persisted for centuries.

Plato (427–347 bce), a Greek philosopher, recognized life as a dynamic balance maintained by the soul. According to Plato a “rational soul” resided in the head and an “irrational soul” was found in the heart and abdomen. He believed that if the rational soul was unable to control the undirected parts of the irrational soul, mental illness resulted. In theory, Plato had foreseen Sigmund Freud by almost 2000 years.

The principles and practices of Greek medicine became established in Rome around 100 bce, but most physicians still believed that demons caused mental illness. The practice of frightening away evil spirits to cure mental illness was reintroduced and its use continued well into the Middle Ages. The Romans showed little interest in learning about the body or mind. Most Roman physicians “wanted to make their patients comfortable by pleasant physical therapies” (Alexander and Selesnick, 1966) such as warm baths, massage, music, and peaceful surroundings.

By 300 ce, “six epidemics killed hundreds of thousands of people and desolated the land” (Alexander and Selesnick, 1966). Churches became sanctuaries for the sick, and soon hospitals were built to accommodate the sufferers. By 370 ce, Saint Basil’s Hospital in England offered services for sick, orphaned, crippled, and mentally troubled people.

Middle Ages

Dark Ages

From about 500 ce to 1100 ce, priests cared for the sick as the Church developed into a highly organized and powerful institution. Early Christians believed that “disease was . . . punishment for sins, possession by the devil, or the result of witchcraft” (Ackerknecht, 1968). To cure mental illness, priests performed demonic exorcisms, religious ceremonies in which patients were physically punished to drive away the evil possessing spirit. Fortunately, Christian charity tempered these practices as members of the community cared for the mentally ill with concern and sympathy.

As time passed, medieval society declined. Repeated attacks from barbaric tribes led to chaos and moral decay. Epidemics, natural disasters, and overwhelming taxes wiped out the middle class. Cities, industries, and commerce disappeared. “The population declined, crime waves occurred, poverty was abysmal, and torture and imprisonment became prominent as civilization seemed to slip back into semi-barbarianism” (Donahue, 1996). Only monasteries remained as the last refuge of care and knowledge.

Throughout the Middle Ages, medicine and religion were interwoven. However, by 1130 CE laws were passed forbidding monks to practice medicine because it was considered too disruptive to their way of life. As a result, responsibility for the care of sick people once again fell to members of the community.

In the late 1100 s, a strong Arabic influence was felt in Europe. The Arabs had retained and improved upon the Greek legacy; they had an extensive knowledge of drugs, mathematics, astronomy, and chemistry, as well as an awareness of the relationship between emotions and disease. The Arabic influence resulted in the establishment of learning centers, called universities. Many were devoted to the study of medicine, surgery, and care of the sick.

Problems of the mind, however, received only spiritual attention. Church doctrine still stated that if a person was insane, it must be the result of some external force—for example, the moon. Thus the term lunacy was coined and “literally means a disorder caused by a lunar body” (Alexander and Selesnick, 1966). In time, large institutions were established, and mentally ill individuals were herded into “lunatic asylums.” Magic was still used to explain the torments of the mind. A few church scholars even suggested that witches might be the source of human distresses.

Superstitions, Witches, and Hunters

The Church’s doctrine of imposed celibacy failed to curtail many of the clergy’s sexual behaviors, and so began an antierotic movement that focused on women as the cause of men’s lust. Women were thought to be carriers of the devil because they stirred men’s passions. “Psychotic women with little control over voicing their sexual fantasies and sacrilegious feelings were the clearest examples of demoniacal possession” (Alexander and Selesnick, 1966). This campaign, in turn, flamed the public’s mounting fear of mentally troubled people.

Witch-hunting was officially launched in 1487 with the publication of the book The Witches’ Hammer, a textbook of both pornography and psychopathology. Soon after, Pope Innocent VIII and the University of Cologne voiced support for this “textbook of the Inquisition.” As a result of this one publication, men, women, children and mentally ill persons were tortured and burned at the stake by the thousands. There were few safe havens during these troubled times.

The first English institution for mentally ill people was initially a hospice founded in 1247 by the sheriff of London. By 1330, Bethlehem Royal Hospital had developed into a lunatic asylum that eventually became infamous for its brutal treatments. Violently ill patients were chained to walls in small cells and often provided “entertainment” for the public. Hospital staff would charge fees for their “tourist attractions” and conduct tours through the institution. Less violent patients were forced to wear identifying metal armbands and beg on the streets. Insane people were harshly treated in those times, but Bethlehem Royal Hospital, commonly called Bedlam (Fig. 1.2), was preferable to burning at the stake.

By the middle of the 14th century, the European continent had endured several devastating plagues and epidemics. One quarter of the earth’s population, more than 60 million people, perished from infectious diseases during this period. The feudal system lost power and declined. Cities began to flourish and housed a growing middle class. “Luxury and misery, learning and ignorance existed side by side” (Donahue, 1996). Society was at last beginning to demand reforms. However, as the age of art, medicine, and science dawned, the hunting of “witches” became even more popular. It was a time of great contradictions.

The Renaissance

The Renaissance began in Italy around 1400 and spread throughout the European continent within a century. Upheavals in economics, politics, education, and commerce brought the real world into focus, and the power of the Church slowly declined as an intense interest in material gain and worldly affairs developed. At the same time, the medieval view of a sinful, naked form changed into a celebration of the human form by artists such as da Vinci, Raphael, and Michelangelo. Thousand-year-old anatomy books were replaced by realistic anatomic drawings. Observation, rather than ancient theories, revolutionized many of the ideas of the day.

Sixteenth-century physicians, relying on observation, began to record what they saw. Mental illness was at last being recognized without bias. By the mid-1500s, behaviors were accurately recorded for melancholia (depression), mania, and psychopathic personalities. Precise observations led to classifications for different abnormal behaviors. Mental problems were now thought to be caused by some sort of brain disorder—except in the case of sexual fantasies, which were still considered to be God’s punishment or the result of possession by the devil. However, despite great advances in knowledge, the actual treatment of mentally troubled people remained inhumane.

The Reformation

Another movement that influenced the care of the sick—the Reformation—occurred in 1517. People were displeased with the conduct of the clergy and the widespread abuses occurring within the Catholic Church. Martin Luther (1483–1546), a dissatisfied monk, and his followers broke away from the Catholic Church and became known as Protestants. As a result of this separation, many hospitals operated by the Catholic Church began to close. Once again the poor, sick, and insane were turned out into the streets.

Seventeenth Century

During the 17th and 18th centuries, developments in science, literature, philosophy, and the arts laid the foundations for the modern world. Reason was slowly beginning to replace magical thinking, but a strong belief in demons persisted.

The 1600s produced many great thinkers. Knowledge of the secrets of nature brought a sense of self-reliance. However, many people were uncomfortable, so they once again moved toward the security of witch-hunting as a means of protecting themselves from the unexplainable.

It was during the 17th and 18th centuries that conditions for mentally ill individuals were at their worst. While physicians and theorists were making observations and speculations about insanity, patients were bled, starved, beaten, and purged into submission. Treatments for the mentally troubled remained in this unhappy state until the late 1700s.

Eighteenth Century

During the latter part of the 18th century, psychiatry developed as a separate branch of medicine. Inhumane treatment and vicious practices were openly questioned. In 1792, Philippe Pinel (1745–1826), the director of two Paris hospitals, liberated patients from their chains “and advocated acceptance of the mentally ill as human beings in need of medical assistance, nursing care, and social services” (Donahue, 1996). During this period, the Quakers, a religious order, established asylums of humane care in England.

In the American colonies, the Philadelphia Almshouse was erected in 1731; it accepted sick, infirm, and insane patients as well as prisoners and orphans. In 1794 Bellevue Hospital in New York City was opened as a pesthouse for the victims of yellow fever and by 1816 it had enlarged to contain an almshouse for poor people, wards for the sick and insane, staff quarters, and even a penitentiary.

Unfortunately, the care and treatment of people with mental illness remained as harsh and indifferent in the United States as it was in Europe. The practice of allowing poor people to care for mentally ill individuals continued well into the late 1800s and was only slowly abandoned. Actual care of mentally ill persons in the United States did not begin to improve until the arrival of Alice Fisher, a Florence Nightingale–trained nurse, in 1884.

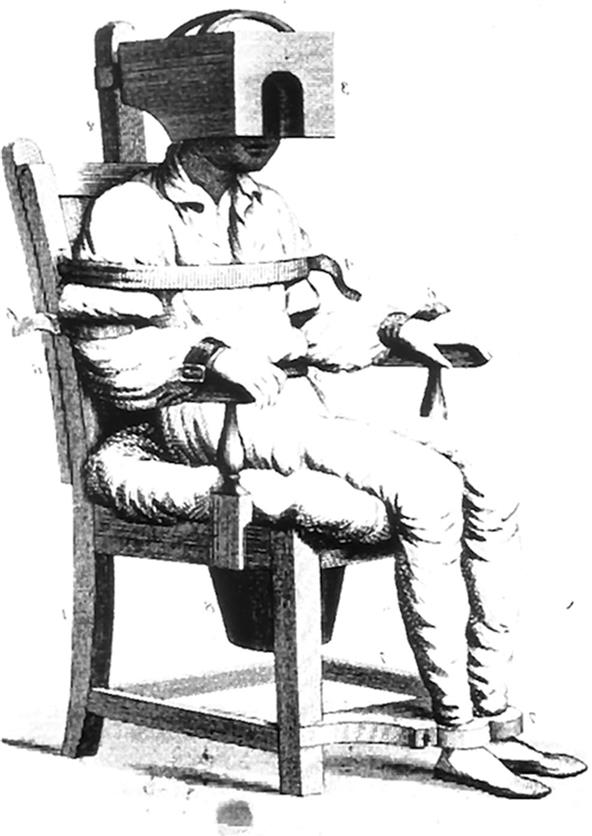

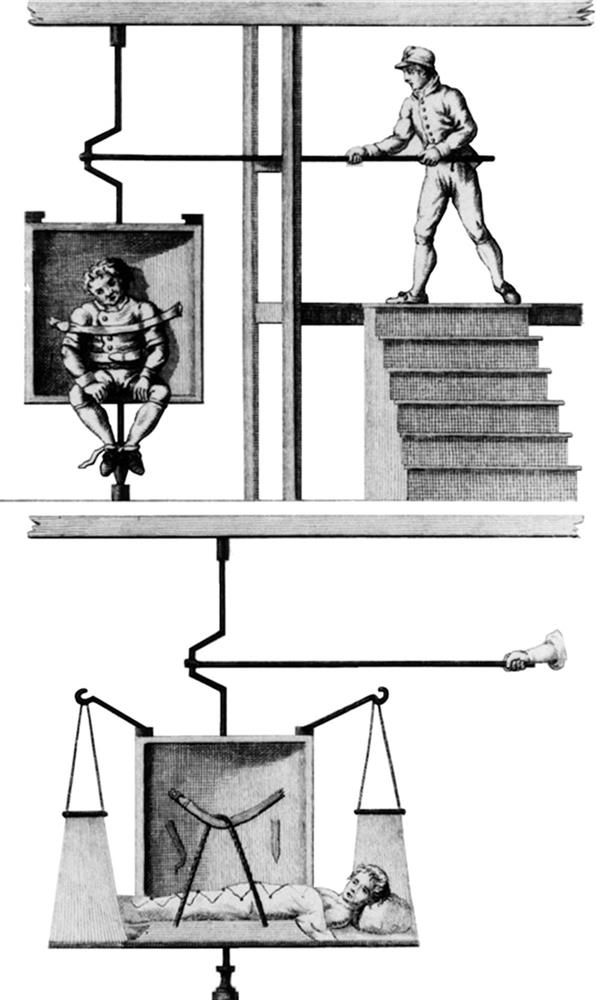

By the close of the 18th century, treatments for people with mental illness still included the medieval practices of bloodletting, purging, and confinement (Fig. 1.3). Newer therapies included demon-expelling tranquilizing chairs (Fig. 1.4) and whirling devices (Fig. 1.5). The study of psychiatry was in its infancy, and those who actually cared for insane people still relied heavily on the methods of their ancestors.

Top panel: A black and white painting of a patient tied to a swing and a man on the stairs stands with a pole positioned at the rod of the swing.Bottom panel: A black and white painting lying on a swinging bed and a hand holds a pole positioned at the rod of the swinging bed.

Nineteenth-Century United States

By the early 1800s the Revolutionary War had ended, and the United States was a growing nation. Changes that occurred during this century had an enormous effect on the care of the mentally ill population.

One of the most important figures in 19th-century psychiatry was Dr. Benjamin Rush, a crusader for the insane. Dr. Rush (1745–1813) graduated from Princeton University at 15 years of age. By the time he was 31, he had been a professor of chemistry and medicine and a chief surgeon in the Continental Army; he was also a signatory of the Declaration of Independence. His book Diseases of the Mind was the first psychiatric text written in the United States. In it, he advocated clean conditions (good air, lighting, and food) and kindness. As a result of Rush’s efforts, mentally troubled people were no longer caged in the basements of general hospitals. However, only a few institutions for insane persons were actually available in the United States at this time. Mildly affected people were commonly sold at slave auctions, whereas the more violent remained in asylums that were a combination of zoo and penitentiary.

During the 1830s, attitudes toward mental illness slowly began to change. The “once insane, always insane” concept was being replaced by the notion that cure might be possible. A few mental hospitals were built, but the actual living conditions for most patients remained deplorable.

It was not until 1841 that a frail 40-year-old schoolteacher exposed the sins of the system. Dorothea Dix was contracted to teach Sunday school at a jail in Massachusetts. While there, she saw both criminals and mentally ill prisoners living in squalid conditions. For the next 20 years, Dix surveyed asylums, jails, and almshouses throughout the United States, Canada, and Scotland. It was not uncommon for her to find mentally ill people “confined in cages, closets, cellars, stalls, and pens . . . chained, naked, beaten with rods and lashed into obedience” (Dolan, 1968).

Dorothea Dix presented her findings to anyone who would listen. Her untiring crusade had results that shook the world. The public became so aroused by Dix’s efforts that millions of dollars were raised, more than 30 mental hospitals were constructed throughout the United States, and care of the mentally ill greatly improved.

By the late 1800s, a two-class system of psychiatric care had emerged: private care for the wealthy and publicly provided care for the remainder of society. The newly constructed mental institutions were quickly filled, and soon chronic overcrowding began to strain the system. Cure rates fell dramatically. The public became disenchanted, and mental illness was once again viewed as incurable. Only small, private facilities that catered to the wealthy had some degree of success. State facilities had evolved into large, remote institutions that became completely self-reliant and removed from society.

By the close of the 19th century, many of the gains in the care for the mentally ill population had been lost. Overpopulated institutions could offer no more than minimal custodial care. Theories of the day gave no satisfactory explanations about the causes of mental problems, and current treatments remained ineffective. It was a time of despair for mentally troubled people and those who cared for them.

Twentieth Century

The 1900s were ushered in by reform movements; political, economic, and social changes were beginning. For the first time in history, disease prevention was emphasized. For the mentally ill population, however, conditions remained intolerable until 1908, when a single individual began his crusade.

Clifford Beers was a young student at Yale University when he attempted suicide. Consequently, he spent 3 years as a patient in mental hospitals in Connecticut. On his release in 1908, Beers wrote a book, A Mind That Found Itself, that would set the wheels of the mental hygiene movement in motion. In it he recounted the beatings, isolation, and confinement of a mentally ill person. As a direct result of Beers’s work, the Committee for Mental Hygiene was formed in 1909. In addition to prevention, the group focused on removing the stigma attached to mental illness. Under Beers’s energetic guidance, the movement grew nationwide. The social consciousness of a nation had finally been awakened.

Psychoanalysis

In the early 1900s, a neurophysiologist named Sigmund Freud published the article that introduced the term psychoanalysis to the world’s vocabulary. Freud believed that forces both within and outside the personality were responsible for mental illness. He developed elaborate theories around the theme of repressed sexual energies. Freud was the first person who succeeded in “explaining human behavior in psychologic terms and in demonstrating that behavior can be changed under the proper circumstances” (Alexander and Selesnick, 1966). The first comprehensive theory of mental illness based on observation had emerged, and psychoanalysis began to gain a strong hold in America (see Chapter 5).

Influences of War

By 1917 the United States had entered World War I. Men were drafted into service as rapidly as they could be processed, but many were considered too “mentally deficient” to fight. As a result, the federal government called on Beers’s Committee for Mental Hygiene to develop a master plan for screening and treating mentally ill soldiers. The completed plan included methods for early identification of problems, removal of mentally troubled personnel from combat duty, and early treatment close to the fighting front. The committee also recommended that psychiatrists be assigned to station hospitals to treat combat veterans with acute behavioral problems and should provide ongoing psychiatric care after soldiers returned to their homes.

A renewed interest in mental hygiene was sparked by the war. During the 1930s, new therapies for treating insanity were developed. Insulin therapy for schizophrenia induced 50-hour comas through the administration of massive doses of insulin. Passing electricity through the patient’s head (electroconvulsive therapy [ECT]) helped to improve severe depression, and lobotomy (a surgical procedure that severs the frontal lobes of the brain from the thalamus) almost eliminated violent behaviors. A new class of drugs that lifted spirits of depressed people, the amphetamines, was introduced. All these therapies improved behaviors and made patients more receptive to Freud’s psychotherapy. Public interest was renewed, and in 1937 Congress passed the Hill-Burton Act, which funded the construction of psychiatric units throughout the United States.

From 1941 to 1945, the United States was immersed in World War II. Many draftees were still rejected for enlistment because of mental health problems. A large number of soldiers received early discharges based on psychiatric disorders, and many active-duty personnel received treatment for psychiatric problems.

In 1946, Congress passed the National Mental Health Act, which provided funding for programs in research, training of mental health professionals, and expansion of state mental health facilities. By 1949, the National Institute of Mental Health was organized to provide research and training related to mental illness. New approaches to the care of the mentally ill population (the therapeutic community movement, family care, halfway houses) sparked the public’s enthusiasm.

The Korean War of the 1950s, the Vietnam War of the 1960s and 1970s, and other armed conflicts contributed significant knowledge to the understanding of stress-related problems. Posttraumatic stress disorders became recognized among soldiers fighting wars. Today, stress disorders are considered the basis of many emotional and mental health problems.

Introduction of Psychotherapeutic Drugs

Psychotherapeutic drugs are chemicals that affect the mind. These drugs alter emotions, perceptions, and consciousness in several ways. They are used in combination with various therapies for treating mental illness. Psychotherapeutic drugs are also called psychopharmacologic agents, psychotropic drugs, and psychoactive drugs.

“By the 1950s, more than half the hospital beds in the United States were in psychiatric wards” (Taylor, 1994). Patients were usually treated kindly, but effective therapies were still limited. Treatments consisted of psychoanalysis, insulin therapy, electroconvulsive (shock) therapy, and water/ice therapy. More violent patients were physically restrained in straitjackets or underwent lobotomy. Drug therapy consisted of sedatives (chloral hydrate and paraldehyde), barbiturates (phenobarbital), and amphetamines that quieted patients but did little to treat their illnesses.

In 1949, an Australian physician, John Cade, discovered that lithium carbonate was effective in controlling the severe mood swings seen in bipolar (manic-depressive) illness. With lithium therapy, many chronically ill clients were again able to lead normal lives and were released from mental institutions. Encouraged by the apparent success of lithium, researchers began to explore the possibility of controlling mental illness using various new drugs.

Chlorpromazine (Thorazine) was introduced in 1956 and proved to control many of the bizarre behaviors observed in schizophrenia and other psychoses (Keltner and Folks, 2005). The 1950s concluded with the introduction of imipramine, the first antidepressant. Soon other drugs, such as antianxiety agents, became available for use in treatment.

As more patients were able to control their behaviors with drug therapy, the demand for hospitalization decreased. Many people with mental disorders could now live and function outside institutions. At this time, the federal government began the movement called deinstitutionalization, the release of large numbers of mentally ill persons into the community. To illustrate, 560,000 patients were cared for in state hospitals in 1955. By 1994, the number of institutionalized patients had dropped to fewer than 120,000 people. Today, fewer than 38,000 psychiatric beds remain in the United States (Fuller, et al, 2016). The introduction of psychotherapeutic drugs opened the doors of institutions and set the stage for a new delivery system: community mental health care.

The 1960s were filled with social changes. With the introduction of psychotherapeutic drugs came the concept of the “least restrictive alternative.” If patients could, with medication, control their behaviors and cooperate with treatment plans, then the controlled environment of the institution was no longer necessary. It was believed that people with mental disorders could live within their communities and work with their therapists on an outpatient basis.

Congressional Actions

As the population of people with mental illnesses shifted from the institution to the community, the demand for community mental health services expanded. To meet this demand, the federal government acted to establish a nationwide network of community mental health centers.

The Community Mental Health Centers Act was passed by Congress in October 1963. This act was designed to support the construction of mental health centers in communities throughout the United States. At these centers, the needs of all people experiencing mental or emotional problems, as well as those of acute and chronic mentally ill people, would be met. Physicians (psychiatrists), nurses, and various therapists would develop therapeutic relationships with clients and monitor their progress within the community setting. Each center was to provide comprehensive mental health services for all residents within a certain geographic region, called a catchment area.

It was believed that community mental health centers would provide the link in helping mentally ill people make the transition from the institution to the community, thus meeting the goal of humane care delivered in the least restrictive way. Passage of the Medicare/Medicaid Bill of 1965, combined with the Community Mental Health Centers Act, led to the release of more than 75% of institutionalized mentally ill persons into the community. Unfortunately, most chronically mentally ill people were “dumped” into their communities before realistic strategies, programs, and facilities were in place.

Community mental health centers expanded throughout the 1970s, but funding was inadequate and sporadic. Demands for services overwhelmed the system and non–revenue-generating services (prevention and education) were eliminated. Services for the general public dwindled and many centers began to close their doors. Finally, in 1975, Congress passed amendments to the Community Mental Health Centers Act that provided funding for community centers based on a complex set of guidelines. The President’s Commission on Mental Health was established in 1978 by President Jimmy Carter. Its task was to assess the mental health needs of the nation and recommend possible courses of action to strengthen and improve existing community mental health efforts. The commission’s final report resulted in 117 specific recommendations grouped into four broad areas: coordination of services, high-risk populations, flexibility in planning services, and least restrictive care alternatives.

In 1980, Congress passed one of the most progressive mental health bills in history. The Mental Health Systems Act addressed community mental health care and clients’ rights, and established priorities for research and training. However, before the recommendations could be nationally implemented, the United States elected a new president, and mental health reform changed dramatically.

Just as legislation that comprehensively dealt with mental health issues was about to be enacted, the political climate changed. Federal funding for all mental health services was drastically reduced. The passage of the Omnibus Budget Reconciliation Act (OBRA) of 1981 essentially repealed the Mental Health Systems Act. This resulted in block grant funding where each state received a “block” or designated amount of federal money. The state then determined where and how the money was spent. Unfortunately, many states proved less committed to mental health with the use of their block grant money. As a result, many hospitalized mentally ill people (especially the older adult population) were transferred to less appropriate nursing homes or other community facilities.

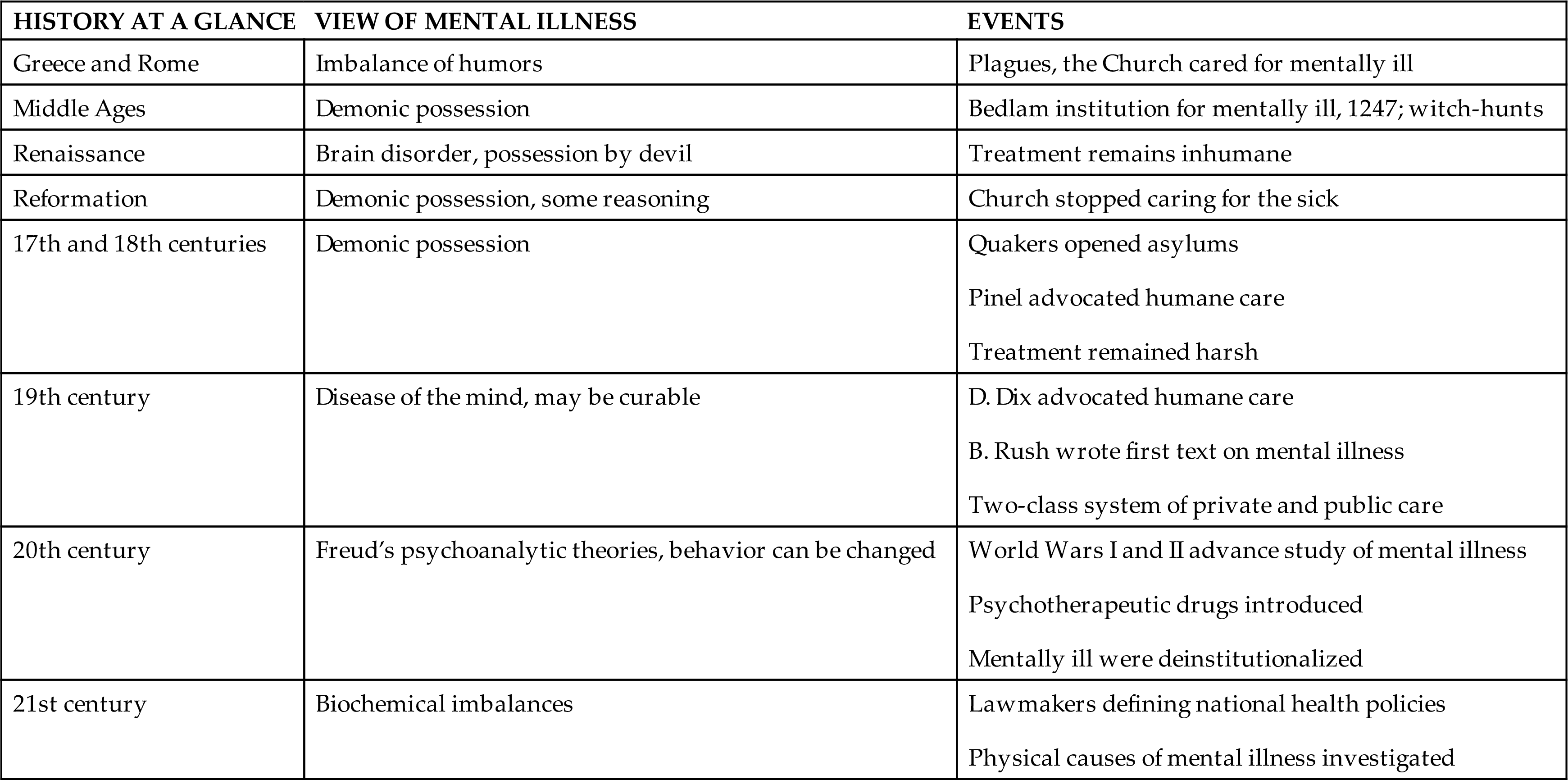

When the Omnibus Budget Reconciliation Act of 1987 was passed, people with chronic mental problems could no longer be inappropriately “warehoused” in nursing homes or other long-term facilities, and many were discharged to the streets. As concern for a rapidly expanding federal budget deficit grew, funding for mental health care dwindled. By the late 1980s, funding was curtailed for most inpatient psychiatric care. Following the trend, most insurance companies withdrew their coverage for psychiatric care. See Table 1.1 for a brief history of mental health care.

Table 1.1

Twenty-First Century

In 2006, the National Alliance for Mental Illness (NAMI) conducted the “first comprehensive survey and grading of state adult mental health care systems conducted in more than 15 years” (NAMI, 2006). The results revealed a fragmented system with an overall grade of D. Recommendations focused on increased funding, availability of care, access to care, and greater involvement of consumers and their families.

Today many of our population’s most severely mentally ill people still wander the streets in abject poverty and homelessness as a result of federal and state funding cuts. Community mental health centers have closed their doors or drastically reduced their services. Federal funding is limited to block grants (for all health care) to each state. The original goals of comprehensive care, education, rehabilitation, prevention, training, and research were lost in the efforts to curtail costs.

To address the growing lack of mental health care, Congress passed the Mental Health Parity and Addiction Equity Act of 2008. This bill required insurance coverage for mental health and substance use conditions that was equal to the coverage for medical problems. Under the Affordable Care Act of 2010, all insurers are required to cover 10 Essential Health Benefit groups; mental health problems are included conditions. It is estimated that the Affordable Care Act will include “federal parity protection to 62 million Americans” (Beronio, Po, Skopec, and Glied, 2013).

Currently, lawmakers in the United States are working to define a new national health policy. Models for delivering cost-effective health care are being investigated, but no comprehensive plan is yet in place. Other countries, such as Canada, the United Kingdom, and Australia, are faced with similar mental health care issues. It is in all of our best interests to accept the challenge of providing for our societies’ mental and physical health care needs. The Critical Thinking exercise offers something to consider.