Principles and Skills of Mental Health Care

http://evolve.elsevier.com/Morrison-Valfre/

Upon completion of this chapter, the student will be able to:

- 1. Describe three characteristics of a mentally healthy adult.

- 2. Explain how the phrase “do no harm” applies to mental health care.

- 3. Apply the seven principles of mental health care to client care.

- 4. Identify the four components of any behavior.

- 5. Summarize the primary purpose of, and six guidelines for, providing safe and effective crisis intervention.

- 6. Illustrate how setting limits helps to provide consistency for mental health clients.

- 7. Describe how failure contributes to the development of insight.

- 8. Identify ways to prevent overinvolvement and codependency.

- 9. Discuss the importance of personal and professional commitments.

- 10. Describe four techniques for developing a positive mental attitude.

- 11. List ten principles for nurturing yourself and other caregivers.

Key Terms

acceptance (ăk-SĔP-tәns) (p. 88)

advocacy (ĂD-vә-kә-sē) (p. 81)

behavior (bē-HĀV-yŏr) (p. 81)

caring (p. 86)

commitment (kә-MĬT-mĕnt) (p. 89)

consistency (kŏn-SĬS-tĕn-sē) (p. 85)

coping mechanisms (KŌ-pēng MĔK-ә-nĭz-әms) (p. 84)

crisis (KRĬ-sĭs) (p. 84)

empathy (ĔM-pә-thē) (p. 81)

failure (FĀL-yŭr) (p. 87)

holistic (hō-LĬS-tik) health care (p. 80)

insight (ĭn-sīt) (p. 87)

introspection (ĬN-trō-SPĔK-shәn) (p. 87)

mentally healthy adult (p. 79)

nurture (NĔR-chŭr) (p. 90)

principle (PRĬN-sĭ-pәl) (p. 79)

responsibility (rē-SPŎN-sĭ-BĬL-ĭ-tē) (p. 82)

self-awareness (SĔLF-ә-WĂR-nĕs) (p. 86)

stigma (STĬG-mә) (p. 80)

Principles of Mental Health Care

A principle is a code or standard that helps govern conduct. Principles guide decisions and actions; professional principles provide guidelines. Most health care professions are guided by standards of care, state practice acts, and principles. This chapter examines the basic principles and skills for those who work with mentally or emotionally troubled clients.

The Mentally Healthy Adult

The concepts of mental health and mental illness are not easily defined. Health, by its very nature, is a changing state, influenced by genetics, behavior, and the environment. Mental health is just as dynamic, changing as the stresses of life are encountered.

Most people manage to adapt to changes in their lives and remain contributing members of their society. Problems exist, but mentally healthy adults are content with who and where they are in life. They are able to love and express love freely without the fear of losing their independence. Flexibility and a willingness to try something different lead to an eagerness for learning. Life is considered important, and special moments are cherished. Adversity is viewed as a challenge or an opportunity for growth. To simplify: a mentally healthy adult is a person who can cope with and adjust to the recurrent stresses of daily living in an acceptable way. Although mentally healthy adults experience unhappiness, anxiety, or other psychic distresses, they manage to mobilize their resources, rise above the negativity, and continue on with their lives.

Citizens of the industrialized cultures label a person as mentally ill only after his or her ability to function independently in society is impaired for a period (Giger, 2017). In our culture, mental illness results when an individual’s problems become so overwhelming that one is unable to carry out the activities of daily living or function independently. Other cultures have different definitions of mental illness.

Mental Health Care Practice

The helping professions are based on the care of the whole person. Practicing the principles of mental health care is the responsibility of all health care providers. No matter which specialty or where the setting, every caregiver helps clients cope with their problems.

The world of health care is familiar and comfortable for those who practice within its realm. The sights, sounds, and smells of the health care environment become known and familiar, daily routines are established, and the employees all understand what behaviors are expected of them. However, to a person who is ill (disabled, stressed), visiting a medical facility can be an uncomfortable experience. Anxiety results when illness or disability affects any individual. No matter how casual a client may appear, heightened stress levels are present every time interactions with health care providers take place. Some people are so intimidated by the health care system that they wait to seek help until their problems become severe and difficult to treat. Sensitive care providers remember that clients are “out of their element” when seeking health care and need emotional support and effective care.

The skills developed when working with the mental and emotional needs of people will be used throughout your career, for yours is the profession of caring. The seven principles of mental health care listed in Box 8.1 will help guide you.

Do No Harm

The “do no harm” principle serves as a guide for all therapeutic actions. Care providers in every setting have the responsibility to protect clients, but for caregivers working with mental health clients, this principle is especially important.

The main therapeutic tool of mental health care providers is the “self.” Therapeutic use of the self can result in great improvements in clients’ behaviors when the “do no harm” principle is applied; however, when it is overlooked or forgotten, the loser is the client—the very person we are obligated to protect. No matter what the circumstances, avoid any action that may result in harm to your client. The “do no harm” principle also relates to the “reasonable and prudent nurse (caregiver)” concept found in US law. It is derived from the ancient writings of Hippocrates, whose principle of “do no harm” proves to be as true and valid today as it was in ancient Greece.

Accept Each Client as a Whole Person

People with mental problems suffer from a socially imposed stigma. The word stigma is defined as a sign or mark of shame, disapproval, or disgrace, of being shunned or rejected. Because people feel uneasy about discussing behaviors that are different, they shy away from mentally troubled individuals. One of the barriers to recovering from a mental illness is the social stigma that clients experience. Caregivers should set examples by acting as advocates for clients and educating themselves about psychiatric illnesses.

The principle of acceptance (allowing others to be who they are without passing judgment) is important in health care because you will care for many different people. Those differences do not have to be understood, but they must be accepted. You may even disapprove of clients’ attitudes and behaviors, but you must accept the person because it is the person who is the focus of your health care activities.

Holistic Framework

Holistic health care is based on the concept of “whole.” Understanding clients in relation to their work, family, and social environments encourages caregivers to consider their many needs and tailor individualized interventions.

In a health-oriented model, clients are assessed for their strengths and abilities. Goals of care are developed mutually; interventions are designed for the individual, and clients receive the services most important and relevant to them. Responsibility for success is shared between client and care provider.

Health care providers who practice holistically realize that each person must be accepted for who and what he or she is, no more and no less. They accept the whole person and search for meaning in the client’s actions; behaviors are attempts to fill needs. Your acceptance is communicated to the clients, and your actions will result in success. However, if you pass judgment, clients will sense your disapproval and therapeutic actions will not be successful.

Viewing clients holistically also involves an acceptance of their lifestyles, attitudes, social interactions, and living conditions. This can be difficult, especially when the environment or lifestyle is harmful. People with mental-emotional difficulties may display odd behaviors or verbalize unusual beliefs. They need to be accepted, just as clients with physical maladies are accepted. Identify your reactions to clients; our reactions to their behaviors can sometimes cloud their messages. Work to develop an acceptance of each client by considering the whole individual.

Progress may come slowly when working with clients who are experiencing mental health problems. A holistic point of view and a focus on the positive encourage both care providers and clients to strive for success. They allow psychiatric clients respect, and help us accept all people regardless of how different they may be from ourselves.

Develop Mutual Trust

The word trust means assured hope and reliance on another. Erikson’s theory (see Chapter 5) lists the development of trust as the first core task of the infant. Trust is an important concept for human beings, who are social and group oriented. Trust implies cooperation, support, and a willingness to work together, and it occurs on many levels. For example, when you drive your vehicle, you are engaging in an act of trust: you trust that oncoming drivers will stay on their side of the small, painted yellow line that divides the road. Numerous other small acts of trust occur throughout the day; we are usually too busy to notice them, yet to care providers, the concept of trust holds much importance.

Individuals who are unable to trust cannot rely on others for help. Many people with mental-emotional problems struggle with problems of trust. Care providers must routinely demonstrate that they can be trusted. To communicate the messages of trust, remember to do what you say you will do. If you tell a client that you will return in 10 minutes, be back in 10 minutes (better yet, be there sooner). Clients soon learn which caregivers follow their words with actions. Trust begins to grow when clients know they can depend on their caregivers.

Trust is the foundation of therapeutic relationships and it forms the basis for the success or failure of all actions. People who become your clients, no matter what their diagnoses, need to trust that they will be cared for in a safe and supportive manner. The development of trust between clients and caregivers involves three concepts: caring, empathy, and advocacy (Keltner and Steele, 2019).

For people with mental illness, caring plays an especially important role. They know, subconsciously, whether you actually care or regard them as just another client. Before trust can be developed, clients must truly believe that their nurses and other providers care.

Empathy is the ability to recognize and share the emotions of another person without actually experiencing them. It includes an understanding and acceptance of the meaning and significance of that person’s behavior. It is a willingness to see the world as the client does. Clients with mental illnesses frequently live in a lonely world of personal suffering, detached from society. Empathy, in these cases, becomes a powerful therapeutic tool that can help reestablish one’s self-worth and dignity. If clients believe that you are willing to share their discomforts, they become more interested in learning to help themselves.

Advocacy is the process of providing a client with the information, support, and feedback needed to make a decision (Keltner and Steele, 2019). Client advocacy adds the obligation to act in the client’s best interest. People with mental-emotional difficulties are not always capable of making informed decisions. Here, caregivers intervene to ensure that the client’s basic needs are being met. For example, if a client decides not to eat, the care provider may act in the client’s best interest by making the food easily available. The client cannot be forced to eat, but he or she can be encouraged to make more healthful choices. Client advocacy also involves the concept of empowerment. Many mentally ill people are quite capable of taking part in their care and treatment. Some are not, but all deserve the opportunity to make the decisions they are capable of making. Nurses and other caregivers act as advocates by assisting clients through the decision-making process. Providing information and education assists clients in making appropriate decisions about their care. When clients feel that their care providers understand and act in their best interests, trust is established. The therapeutic relationship is discussed more fully in Chapter 11.

Explore Behaviors and Emotions

Every behavior serves a purpose and has meaning; behaviors are attempts to fill personal needs and goals. Each of us lives within our own private world. Most people’s private worlds (internal frames of reference) are agreeable with others. However, people with mental-emotional difficulties have private worlds that may be difficult for the average person to understand.

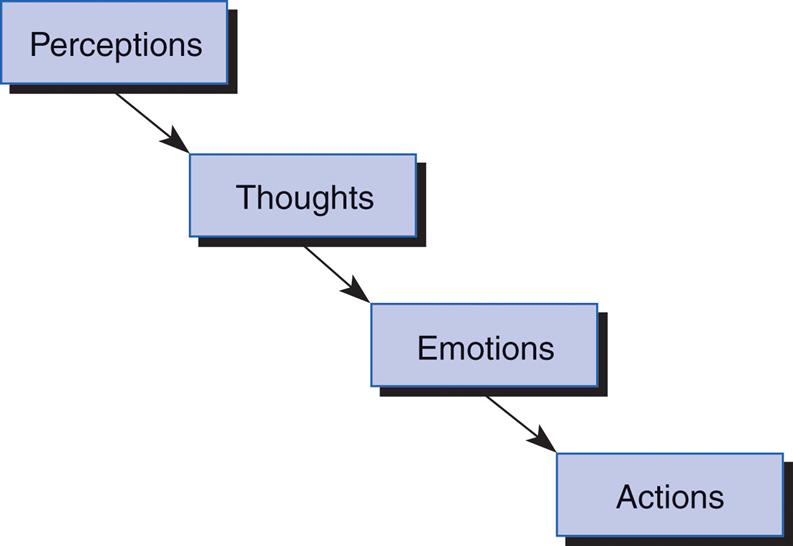

“Behavior consists of perceptions, thoughts, feelings, and actions” (Stuart, 2013) (Fig. 8.1). A disruption in any one of these areas can result in behavioral problems. Distorted perceptions, impaired thought processes, and alterations of emotional expression lead to maladaptive actions. Behaviors also must be understood in terms of the context or setting in which they occur. For example, a particular environment may be threatening because of uncomfortable past experiences in similar settings.

It is sometimes difficult to accurately interpret the messages a client’s behavior is sending. Actions may be clouded with symbols or influenced by chemical substances. Alcohol and other drugs affect perceptions, emotional expression, and judgment, as well as behavior.

An often overlooked method of understanding the meaning of a client’s behavior is to simply ask the individual. Many clients are willing to share, when: (1) they have trust in you and (2) you are willing to take the time to listen. When people with mental health problems can discuss their behaviors or share their emotions, they are not looking for approval or reproach; acceptance and a gentle exploration of what the behaviors mean to them will help develop and practice insight. Recognizing ineffective behaviors and replacing them with more appropriate actions is the first step toward gaining some control over one’s situation.

Explaining how you view the client’s behaviors allows for perception checks. Is the client sending the same message that you are receiving? Do each of you see the same messages in the client’s symbols? If a client says he feels like a duck, do you know what he is really trying to portray? Sharing your perceptions helps clients see how their behavioral messages are being received by other people, and it allows you the opportunity to gain insight into their worlds.

Some clients are unable to share the meanings of their behaviors verbally; they communicate with actions only. Caregivers must develop acute observational skills with these individuals. Repeated behaviors are often attempts to undo or fix something. Other actions can be cries for help or forms of self-punishment for wrongful deeds. The meaning of a client’s behaviors may be shrouded in mystery, but time, trust, and persistent observations assist in discovering the real meanings that lie behind the messages.

Encourage Responsibility

Responsible people are capable of making and fulfilling obligations, and they are accountable for their decisions or actions. Responsibility implies that a person is able to exercise capability and accountability; individuals who are unable to make or keep obligations are not considered responsible. Health care providers work with clients who exhibit a wide variety of coping styles and behaviors. Encouraging responsibility is a primary mental health intervention because it helps build self-worth, dignity, and confidence. It also assists clients in learning more successful coping behaviors. Responsibility is a cornerstone of modern societies and a goal of mental health care.

As children grow, developing the necessary skills for living within a society, so do their responsibilities. Responsibility is learned early, starting when the child begins to explore and manipulate his or her environment. The primary instructor is the family, but the child’s social group and culture exert strong influences. As children learn about “right behaviors,” they develop the responsibility to engage in them. There is a saying that states, “If the family does not teach responsibility, then the school will. If the school does not teach responsibility, then the group will. If the group does not teach responsibility, then society will, and society sends irresponsible people to jail.”

Many people with mental-emotional problems have difficulty behaving in responsible ways. Some have never been taught because of their dysfunctional family or childhood experiences. Others cannot remember or hold on to a logical picture long enough to be responsible. However, every person has the capacity for growth and therefore some degree of responsibility. Nurses and other professionals who work with the mentally ill population plan and implement specific interventions designed to help clients achieve their highest possible level of responsibility.

The first step in developing self-responsibility relates to care of the self. The basic physical needs of life (Maslow’s lower-order needs) must be met, no matter what the circumstances. Every adult—and, sadly, many children—must procure food, clothing, and shelter for themselves. People with mental-emotional problems commonly have difficulty in meeting basic needs, so lessons of self-responsibility usually begin with something as basic as caring for one’s daily personal hygiene.

Caregivers should assess their clients’ abilities to perform the skills associated with the activities of daily living. For example, sometimes the reason for poor hygiene is a lack of knowledge; a person may never have been taught to bathe frequently or brush teeth after every meal. In such cases the caregiver must teach and the client must learn the basic skills of personal cleanliness. When the client assumes responsibility for basic needs, it leads to improved feelings of self-worth—when one looks good, one feels better. Small successes become positive steps that help equip clients with the skills necessary for effective functioning.

The next step in assuming self-responsibility is to be accountable for one’s emotions. Mental health clients frequently have poor control over their emotions (poor impulse control). They immediately react without considering the consequences of their behaviors. “I’m sorry. I lost my temper” does not excuse the action. Becoming responsible for one’s emotions involves the willingness to identify and then “own” the problems and emotions. It also requires a willingness and determination to try new and more effective ways of coping with emotional reactions.

When clients learn to replace an unacceptable behavior with a more effective action, they achieve a degree of control over their lives. As individuals become responsible, they begin to succeed. Those small successes help to remove them from the role of victim and to realize the value of becoming responsible.

People who seek treatment for mental or emotional problems must assume the responsibility for cooperating with and following their therapeutic plan of care. This involves a commitment to becoming actively involved by sharing personal information, being open to new ideas, and being willing to try new ways of doing things.

Clients are also responsible for the effects of their actions on others. The enjoyment of social interactions is accompanied by the responsibility of behaving appropriately. People who have problems with emotional (impulse) control can become a threat to the safety of others when their behaviors are inappropriate. It is important for caregivers to assist clients in controlling their behaviors because people who act in irresponsible ways are soon removed from social settings.

Responsibility is a fundamental concept in mental health care. It is a key to developing more effective behaviors and building self-worth. Some psychiatric therapies are designed around the concept of responsibility. For example, William Glasser’s reality therapy (1998) uses responsibility as a therapeutic tool (Box 8.2). Reality therapy is used to help clients recover from addiction. It is often used to “help individuals with relationship problems, behavioral problems (e.g., teens who act out), cultural conflicts, depression, anxiety, and challenging life situations such as coping with a serious medical condition” (www.addiction.com/addiction-a-to-z/drug-addiction).

Encourage Effective Adaptation

Mental health clients may be labeled with one or more psychiatric diagnoses, but all have one thing in common: unsuccessful coping behaviors. The very nature of mental illness is characterized by actions that are not in keeping with society’s definitions of appropriate behaviors. Mental health caregivers provide clients with education about, and opportunities to engage in, more effective behaviors.

With some mental-emotional difficulties, we can speak of cures. Situational depression, for example, is frequently cured. Many cases of confusion or delirium are cured when a physical problem is discovered and treated. However, some mental problems are chronic and force clients and their significant others to make permanent changes in how they live their lives. Despite this reality, many people with chronic illnesses—both physical and mental—adapt and lead full, satisfying, and meaningful lives. Adaptation in this context is not the same as the “cure” of a medical illness. Here it means there has been sufficient improvement for the client to carry on everyday activities. In other words, if we can teach clients to replace maladaptive behaviors with more effective actions, they will improve in their abilities to live more successfully.

One Step at a Time

There is an old saying, “The longest journey begins with a single step,” and it was never so true as in mental health care. To people with mental-emotional problems, everything seems overwhelming; even the simplest decisions can be monumental. People diagnosed with schizophrenia may not be able to differentiate one world from another for long enough to follow a train of thought to a logical conclusion. Therefore it is important for caregivers to give instructions simply and repeat them often.

When planning therapeutic interventions, remember that it is important to master the first item before proceeding to more complex steps. This process involves breaking down a task or concept into small and simple units. For example: if the goal is for a client to arrive on time for his appointments, this may involve wearing a watch, being able to tell time, remembering the appointment, and transporting himself to the appointment. The first step in meeting the goal may be the purchase of a watch or learning to tell time.

There are two important points here. First, do not assume—assess. In the preceding example, one assumes that every adult can tell time, but the assessment results revealed that this client could not tell time because of blurred vision. Unless the caregiver helps the client deal with his visual problems, he will not be successful in meeting the goal of routinely keeping all appointments. Second, remember that success is built on many small steps. Breaking each learning experience into small units increases the chances of mastery. Make sure that the client will succeed within the first few steps; the taste of success is especially sweet in the early stages, and it encourages people to continue trying. One small, successful step soon becomes two, and those small triumphs can become symbolic of the client’s potential for growth and change.

Crisis Intervention

When experiencing stress, people use their resources to decrease the discomfort. These efforts, called coping mechanisms, are defined as any thought or action aimed at reducing stress. We all use coping mechanisms as the tools that help us work through the ups and downs of daily living. Coping mechanisms are divided into three main types: psychomotor (physical), cognitive (intellectual), and affective (emotional). When coping mechanisms are successfully used, an individual is able to solve problems and reduce stress; these are adaptive or constructive coping mechanisms. However, when efforts to decrease stress are used without resolving the conflict, then the coping mechanism is labeled as maladaptive or destructive. Table 8.1 describes each type of coping mechanism.

Table 8.1

| MECHANISM | DESCRIPTION | EXAMPLE |

|---|---|---|

| Psychomotor (physical) | Efforts to cope directly with problem | Confrontation, fighting, running away, negotiating |

| Cognitive (intellectual) | Efforts to neutralize threat by changing meaning of problem | Making comparisons, substituting rewards, ignoring, changing values, using problem-solving methods |

| Affective (emotional) | Actions taken to reduce emotional distress; no efforts are made to solve problem | Ego defense mechanisms such as denial and suppression; see Chapter 5 for other ego defense mechanisms |

A crisis is an upset in the homeostasis (steady state) of an individual. A crisis has several characteristics that separate it from other stressful situations. First, the definition of crisis is an individual matter that depends on the perception of the event, the severity of the threat, and the available coping strategies and resources. Second, a crisis occurs when an individual’s usual coping mechanisms are ineffective. The crisis demands new solutions with new coping strategies. Third, crisis is self-limiting. Because human organisms cannot endure high levels of continued stress, crises are usually resolved within a short time. Fourth, a crisis usually affects more than one person. Everyone within the person’s support system is affected by the crisis.

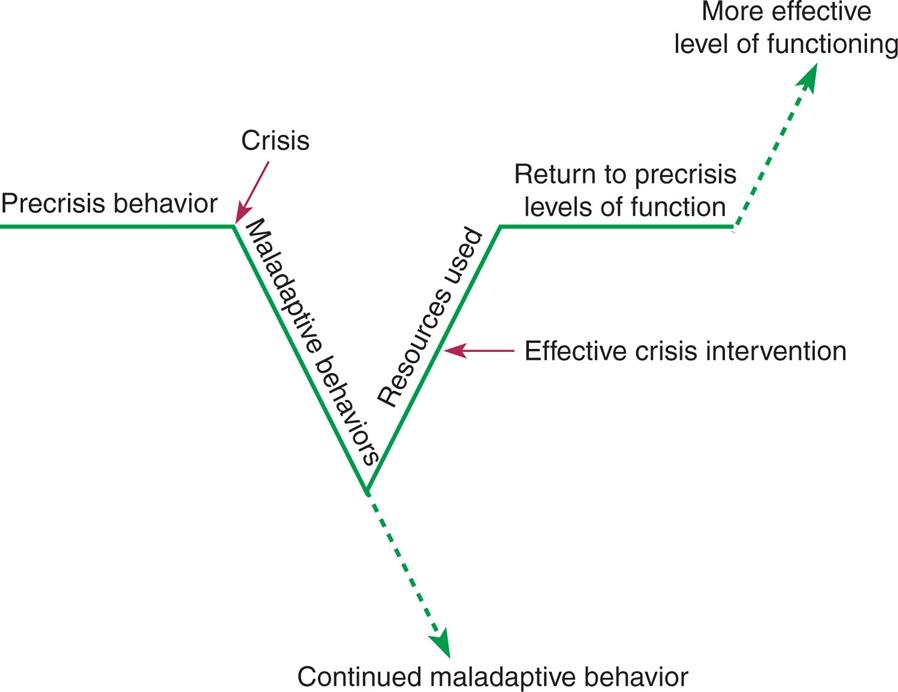

As people experience a crisis, they travel through similar stages: perception, denial, crisis, disorganization, recovery, and reorganization (Fig. 8.2). Once an event is perceived as a crisis, an overwhelming feeling of denial is experienced. This emotion serves to protect the individual from sudden, intense stress. An increase in tension is felt as attempts are made to eliminate the problem. As efforts to cope are ineffective, the individual or family enters the stage of crisis in which everything seems to “fall apart.”

A line with V-shaped dip at the center shows stages of crisis from left to right as follows: Precrisis behavior, crisis, maladaptive behaviors, continued maladaptive behaviors (a dotted arrow pointing down from the center of the V), resources used (effective crisis intervention), return to pre-crisis levels of function, and more effective level of functioning (a dotted arrow pointing upward from the straight line).

During the disorganization phase, individuals become preoccupied with the crisis situation. Activities of daily living no longer continue. The individual becomes flooded with anxiety as attempts are made to reorganize or escape. One may blame others or pretend the situation does not exist, but nothing helps. Once all attempts to deny, solve, escape, or ignore the problem have failed, the individual slowly moves toward recovery. This is the stage at which most people seek help.

Recovery begins when attempts to cope with the problem result in success. One success provides encouragement and builds on another, and soon the stage of reorganization begins. Normal activities are resumed. When a crisis is successfully resolved, the individual functions at a higher level than before. Growth has taken place, and one becomes stronger and more capable.

Crises can also result in unsuccessful resolutions or pseudo-resolutions. Unresolved crises result when maladaptive behaviors are used to hide the problem. An example is the husband who sends his wife to counseling for depression while he continues to abuse her when he drinks. Pseudo-resolution occurs when nothing is learned from the crisis and the opportunity for growth is missed; new stressors may trigger buried conflicts of the unresolved crisis. The inability to solve future crises may be compounded by these old conflicts.

The main goal of crisis intervention is to help individuals and families manage their crisis situations by offering immediate emotional support. People are then assisted in developing effective coping mechanisms, which allows time to reorganize resources and support systems.

Victims of crisis are treated in settings such as emergency departments, clinics, jails, places of worship, homes, and even over the telephone. Crisis hotlines are 24-hour telephone lines staffed by volunteers trained in crisis intervention techniques. Emotional support and referral to various community resources are offered to any caller.

Guidelines relating to crisis intervention have been developed by the National Institute for Training in Crisis Intervention and other organizations. Because crisis situations are high-stress encounters for all parties, the following guidelines can assist in providing safe, effective crisis interventions:

- 1. Care is needed immediately. Actions must be taken to reduce anxiety levels. Sometimes this may require only reassurance. In other situations, interventions must be taken to ensure safety and prevent harm.

- 2. Control. People experiencing a crisis are often unable to exercise control. Safety for both client and care provider must be considered. The care provider must quickly assume control, but only until the client is able to recover self-control. Again, the level of control is determined by each situation. Some people are relieved that someone else is in control, whereas others resort to physical aggression during a crisis. Control is important in a crisis because without it the client cannot be helped to work with the problems that triggered the crisis.

- 3. Assessment. Although assessment usually is the first step in the care process, in crisis the issues of immediacy, safety, and control must be considered first. Thoroughly assess the situation. Ask direct questions, such as, “What happened?” Have the client explain the situation and review the events of the past 2 weeks. A quick and accurate assessment helps to determine the best therapeutic interventions.

- 4. The client’s disposition is determined. A treatment plan is developed that assists the client in working on the problems triggering the crisis. The focus of crisis intervention therapy is to help clients manage their problems more effectively.

- 5. Referral. Once emotionally stabilized and in control, clients are referred to professional, community, or support group resources. The most successful referrals match the client’s needs with the most appropriate service. Know what resources are available within your community before you interact with the client. A caregiver looking through the Yellow Pages or scrolling on a device during a crisis generates lack of confidence and invites problems.

- 6. Follow-up. Care providers must see whether the referrals were actually contacted. A follow-up telephone call will often reveal new problems that prevent the client from receiving needed care.

All people experience crises. When new coping mechanisms are needed but are unavailable because of immaturity, an individual experiences a developmental or maturational crisis. Severe stresses within one’s environment may cause a situational crisis. Assisting people in crisis to mobilize their resources is an important step in encouraging effective adaptation.

Provide Consistency

The last principle for mental health care providers relates to the concept of consistency, which is displaying behaviors that imply being steady, regular, and dependable. People with mental illness often lack the security of someone who is there when needed. In some cases, the consistency and reliability of mental health care providers are their only stability. The link that serves as a bridge between the client’s world and the world of reality is frequently the reliability of the therapeutic relationship.

The concept of consistency is usually addressed in the client’s plan of care, but each therapeutic intervention must be routinely used by every member of the care team. Clients often test staff members by “playing one against the other” or attempting to manipulate the situation and gain control. However, when each care provider responds by giving the same message, clients learn that members of the care team can be relied on to do what they say they will do. In many cases, assertiveness training has proven effective for care providers in working with manipulative clients (Yoshinaga, et al., 2018). Two general guidelines for providing consistency are (1) to set limits and (2) to focus on the positive changes that clients are making.

Setting limits involves clients, staff members, and institutional policies (Chenevert, 1994). As the plan of care is developed, each rule or limitation is established. Facility policies define some of the limitations; the remainder relate to therapeutic activities, social interactions, and personal behaviors. Whatever the limitations, the client must be informed and willing to cooperate with the plan of care.

Each member of the care team is responsible for understanding the purpose of each limitation and the methods for enforcing them. To illustrate: the facility’s policy is for all clients to remain out of bed during the day. To accomplish this, the staff informs each client every morning that the doors to the rooms will be locked by 9 a.m. Then the aide makes 9 a.m. rounds and locks the door to each room. The clients were first informed and then reminded of the rule. Then the enforcement or actual action demonstrated that the limitation would be enforced. Something as simple as providing a routine can teach clients about the values of reliability, consistency, and stability.

This brings us to a valuable point: do not commit yourself unless you are able to fulfill the commitment. If your actions are not reliable, if you do not behaviorally demonstrate stability and consistency, then the therapeutic relationship will be established with great difficulty. Clients are people, and they need to know whether someone truly cares and is willing to make the connection that helps them to heal.

Skills for Mental Health Care

Caregivers serve as therapeutic instruments, with each interaction designed to move clients toward the goals of care. They also act as role models for good mental and physical health. They are expected to help solve problems while graciously coping with the varied personalities of many individuals. Caregivers work to instill confidence in their clients and encourage them to change and try new behaviors within the security of the therapeutic relationship.

To practice effectively, a caregiver’s approach to clients must continually be monitored and adjusted. Thought and consideration are given to each therapeutic action. Making a positive, therapeutic use of your personality requires “a consistent, thoughtful effort directed toward developing an awareness of self and others” (Taylor, 1994).

Self-Awareness

Simply defined, self-awareness is a consciousness of one’s personality. It is the act of looking at oneself: of considering one’s abilities, characteristics, aspirations, and concepts of self in relation to others. It is an awareness of one’s personal and social behaviors and how they affect others (Morrison, 1993). In short, self-awareness is the ability to objectively look within.

The development of self-awareness requires time, patience, and a willingness to routinely consider your behaviors, attitudes, and values. The rewards, however, are worth the efforts because both clients and caregivers benefit when therapeutic goals are achieved. Personally, self-awareness allows individuals to direct and mold the pattern of their lives, to be in charge of their own direction and development. Caregivers who encourage the development of self-awareness in their clients must be ready to practice it themselves. To improve self-awareness requires caring, insight, acceptance, commitment, a positive outlook, and the willingness to nurture oneself. If you are willing to put effort into these areas, you will evolve into a person who is able to use your personality to achieve therapeutic change and personal fulfillment.

Caring

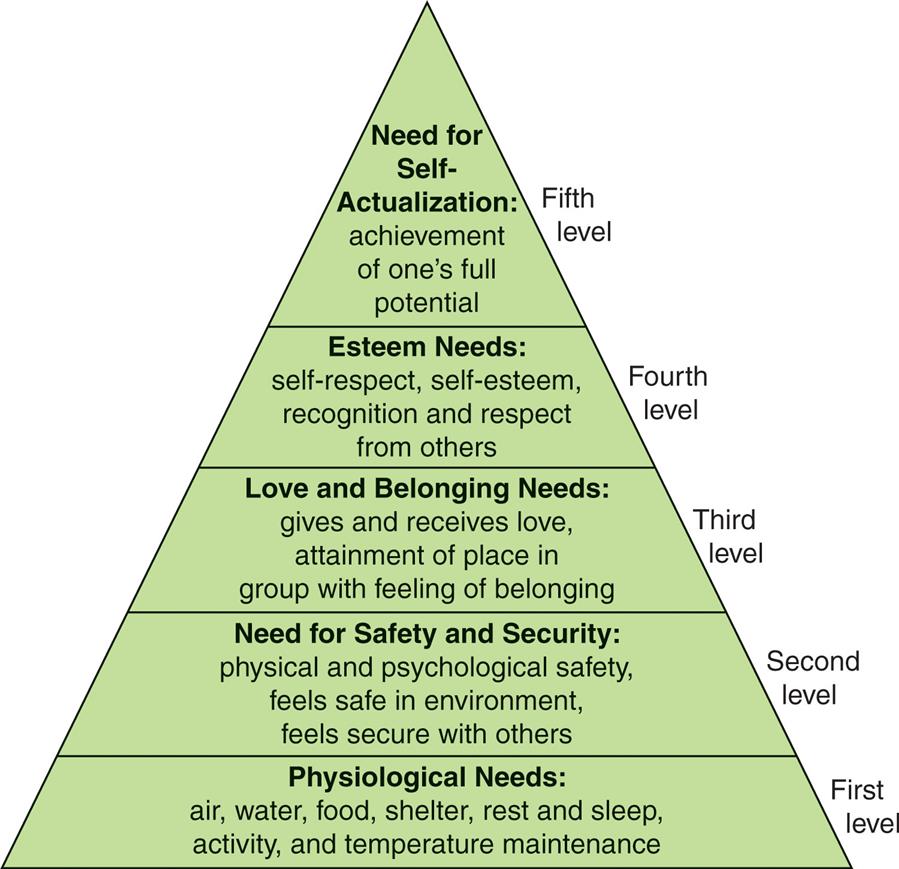

Everyone has the universal human need for love. Maslow’s hierarchy of needs (Fig. 8.3) lists the need for love and belonging as the first nonphysical requirement after safety. Without love, infants fail to grow or thrive and adults become isolated, lonely, and depressed. Human beings are gregarious creatures; we are meant to live with others. Although physical appearances, behavioral patterns, and communication styles may differ, each person carries within the need to belong and be loved.

A pyramid for Maslow’s hierarchy of needs is as follows: First level: Physiological needs: air, water, food, shelter, rest and sleep, activity, and temperature maintenance. Second level: Need for safety and security: physical and psychological safety, feels safe in environment, and feels secure with others. Third level: Love and belonging needs: gives and receives love, attainment of place in group with feeling of belonging. Fourth level: Esteem needs: self-respect, self-esteem, recognition, and respect from others. Fifth level: Need for self-actualization: achievement of one’s full potential.

Caring is the energy on which the health care professions are built. It is defined as a concern for the well-being of another person, and it includes behaviors such as accepting, comforting, honesty, attentive listening, and sensitivity. Caring is the glue that binds individuals to one another. It is energy of the soul, freely given in hopes of helping another human being. Caring cannot be taught as a procedure or skill; it must be developed, encouraged, and molded into the therapeutic personality of the caregiver. Caring serves as a thread that connects people and moves them toward recovery. Box 8.3 lists several therapeutic actions that demonstrate caring.

Insight

We all are responsible for our own development, both professionally and personally. We gain insight and wisdom through experience. Insight is the ability to clearly see and understand the nature of things; it relies on common sense, good judgment, and prudence. Although not always comfortable, our insights provide us with new opportunities to take risks, explore our own potentials, and fail as well as succeed. For care providers, insight includes sensitivity to people, the ability to make keen observations, and a willingness to seek new knowledge.

Self-awareness is developed through the practice of introspection, the process of looking into one’s own mind. Introspection is an analysis of self—one’s feelings, reactions, attitudes, opinions, values, and behaviors. It is also a process for observing and analyzing one’s behavior in various situations. Introspection allows us to “step out” of an interaction and watch our own behaviors; this process is assisted when caregivers can view themselves interacting with clients on video. Introspection allows caregivers to identify both personal and professional learning needs. Practice professional introspection by keeping a small notebook. Throughout the day, jot down any questions or subjects that relate to the care of your clients—anything about which you feel you need to know more. After work, make it a point to research at least one question or topic every day. This practice will serve as a valuable aid for gaining new knowledge. Knowledge breeds competence, and from competence grows the confidence to provide the best possible care.

Personal introspection is the process of learning who you are. This type of introspection may be accompanied by emotional discomfort, but for those individuals who can overcome their emotional defenses, introspection serves as a valuable tool for developing self-awareness.

Risk-Taking and Failure

The process of developing self-awareness includes the elements of risk and failure. If one is to grow, then one must take risks. Risk-taking implies the possibility of failure. For most of us, the word failure has a negative meaning that implies defeat and a lack of success. However, failure can be filled with positive, growth-promoting experiences. Failure provides the opportunity for change. It encourages creativity, stimulates learning, and sharpens one’s judgments. Failure is a price that must be paid for improvement. When used as a learning tool, the experience of failure can provide insight and the foundation for the next step toward success. The person who never fails cannot savor the rewards of success.

How do we grow from our failures? The first and most important step is to understand that failure is a necessary part of change. The second step is to give yourself permission to fail. The odds of a person living a lifetime without a failure are about zero. Failure, learning, and growth are all partners in the development of self-awareness. The third step is to consider your failure as a learning experience. Examine the elements of the failure and discover what improvements could be made. More effective actions in the future can avoid the failures of the past. The fourth and last step is to discover the opportunities that are created by failure. Often a failure opens new doors or presents a problem in an entirely different light. Examining and learning from failure can create new options and opportunities. Box 8.4 lists several suggestions for using failure as a positive experience. Remember that one fails only when one refuses to grow from the experience.

Acceptance

Although people may engage in behaviors that are considered inappropriate, every individual has worth and some degree of dignity. Each client must be given respect and the opportunity to participate in care if treatment is to be successful. Acceptance in this context means the receiving of the entire person and the world in which he or she functions.

Accepting clients does not necessarily include approving of their behaviors. This is an important distinction; you must accept the person, but you do not have to accept the behavior. Many caregivers who work with mentally and emotionally troubled clients do not hesitate to tell a client when his or her behavior is inappropriate, but no mental health caregiver should ever directly attack or correct the person. Table 8.2 presents examples of communications that focus on the difference between correcting the behavior and correcting the person. The very reason clients with mental-emotional problems seek help is to correct their ineffective behaviors. As their care providers, we must accept the entire person as a complete package, regardless of our own reactions. This acceptance then becomes the foundation on which other therapeutic actions are based.

Table 8.2

Boundaries and Overinvolvement

Caregivers give of themselves in order to care for others. Today we realize that to effectively care for others, we must care for ourselves and recharge our batteries, if we are to maintain the necessary energy to work therapeutically with clients. One of the ways in which caregivers maintain their energy levels is to define their helping boundaries.

We all have limits or boundaries over which we will not cross. Personal boundaries provide order and security because they help to establish the limits of one’s behavior. To illustrate: you would not think of stealing from your friends because a personal boundary limits you from doing so.

Professional boundaries define the needs of the caregiver as distinctly different from the needs of the patient: what is helpful and what is not, and what fosters independence or an unhealthy dependence (Raphael-Grimm and Zuccarini, 2015). Once clients stabilize, they are expected to begin functioning independently with guidance and encouragement from the health care team. Professional (helping) boundaries have been crossed when caregivers become too helpful or controlling. The caregiver may feel good, but the client does not function better as a result of the interventions.

The need for professional boundaries must be continually balanced with one’s need to be caring. To do this, care providers establish their own set of professional boundaries by defining the limits of both their personal and professional lives. The focus of the professional aspect is the client, but the focus of the personal aspect is the caregiver. The boundaries of each remain distinct because one cannot focus on the client and the self at the same time.

The therapeutic relationship is anchored in the effective management of professional (helping) boundaries. When the focus of interaction is the client and progress is being made toward the therapeutic goals, the relationship is effective and satisfying for both client and caregiver. To maintain their professional boundaries, caregivers frequently assess their relationships with their clients. If they find themselves having difficulty in setting limits or feel that they are the only one who “really understands” a certain client (i.e., the beginnings of codependency), then cause for concern exists and help should be sought. Discussing the situation with appropriate persons helps provide perspective and increases one’s therapeutic effectiveness.

Detecting boundary violations is often difficult because a person’s own needs stimulate and maintain the violation, but early detection helps prevent larger problems in the future. Frequent self-assessments help monitor for problems. A delicate balance exists between knowing when to help and when not to help clients. Caregivers who are aware of this balance keep the client as the major focus of concern and maintain the professional boundaries that help individuals progress toward their therapeutic goals.

We have all had (or will have) special clients, those who have touched us deeply. Becoming overinvolved is not difficult to do. However, to thrive and grow ourselves, we must learn to walk the fine line between compassion and overinvolvement.

Caregivers are people too, complete with their own attributes and problems. It is easier to form rapport with some clients than with others. Sometimes that rapport leads to an overinvolvement because the client touches the caregiver in some special way. This initial attraction can soon result in conflict because the caregiver begins to have difficulty separating the professional relationship from the growing friendship with the client. When the client–care provider relationship begins to fulfill the caregiver’s needs, codependency results. The relationship loses its therapeutic effectiveness, and the caregiver or client withdraws, left with a mix of unresolved feelings and unmet goals.

To protect yourself from becoming codependent, remember this one rule of thumb: if you show a significantly greater level of concern for one client than for others, then you are running the risk of becoming overinvolved. Recognize this risk early and discuss it with your supervisor. Exploring your feelings in relation to the client helps to regain the balance between professionalism and compassion. Often just the personal awareness of the potential of becoming overinvolved is enough to prevent it from occurring. Compassion, empathy, and acceptance are vital elements of health care, but they must be balanced by professionalism, judgment, and therapeutic actions that meet the client’s needs.

Commitment

A commitment is a personal bond to some course of action or cause. The health care professions are undergoing radical changes; if provision of high-quality care for every person is to remain a primary goal of our society, then a strong commitment from each health care provider will be needed to maintain the focus on our clients. Caregivers must be committed to providing competent health care, no matter what the setting or circumstances.

The first and most important commitment is to yourself: the commitment to consciously take charge of your personal and professional growth. Self-commitment involves a promise to do the best you can in every situation and to be the best that you can be. Each person has a unique set of talents, an individual personality, and areas that need improvement. People who are committed to improving themselves are able to consider both the positive and negative aspects of their personalities without guilt or remorse. They realize their mistakes and attempt to profit from them by extracting the lessons hidden in each error. They then commit themselves to applying these hard-earned lessons to new situations, which in turn enhances self-awareness and expands their ability to cope with new experiences.

Health care providers have stronger commitments than most people. They are committed to caring about the welfare of humankind. They demonstrate this dedication by continually seeking out new knowledge, keeping up to date with the latest professional developments, and striving to improve their therapeutic effectiveness.

You are committed; otherwise, you would not be reading these words. Take the time to discover what you feel is most important in life. Then look behind the topic, and you will find yourself committed to a certain course of action. The exercise of describing one’s commitments helps to expand self-awareness and reminds us of the interconnectedness of all human beings.

Positive Outlook

Distress of the human spirit can be far more damaging than a medical diagnosis. A positive, health-oriented attitude alone can make a difference in someone’s functioning. Learn to approach problems with an attitude that employs the client’s strengths, assets, and resources; a focus on the positive aspects of a situation stands a greater chance of success. When it is assumed that a mental health client will succeed, they usually live up to expectations and do just that—succeed. One small success fosters and breeds other triumphs. Keep your focus on the “can do.” It can have surprising results.

One of the most effective and important tools for developing self-awareness is a positive or optimistic attitude. One’s outlook affects every perception, thought, and emotion. A person with a positive outlook radiates energy and well-being that cheers everyone in the vicinity; people are attracted to such individuals. On the other hand, individuals with negative attitudes tend to discourage other people from interacting with them. Their attitude of doom and gloom can even foster the development of many physical and mental problems.

Positive attitudes and thoughts can act as buffers against stress and conflict. They can prevent caregiver burnout, the syndrome that results when care providers give too much without renewing their energies. A positive outlook does not require one to be continually upbeat. The reality of each situation must be considered objectively, but there is no reason to harbor a negative attitude when a positive one is much more fulfilling. In addition, caregivers who practice positive thinking act as role models for those clients who do not cope effectively within their worlds.

Achieving and maintaining a positive outlook is especially important for caregivers who work with mentally and emotionally troubled individuals. A positive attitude is the secret weapon for coping with the adversity of life. It is the key to maintaining physical and emotional health, especially for those who share their energies therapeutically. Developing a positive attitude (Box 8.5) is a process that requires persistent and patient efforts because our current attitudes and habits are deeply ingrained. However, the process can be assisted by following these five tips:

- 1. Listen to your self-talk. Pay attention to the words you use. Each word has an emotional attachment. The human brain is programmed by thoughts, which become feelings, which evolve into words and actions. Many people complain of being under too much stress or pressure. No one denies that modern life contains its share of stresses, but it is how each stressor is defined that determines your point of view. If you do not define the event as stressful, then it is not. Practice listening to yourself; you may be surprised at what you discover.

- 2. Change recurrent negative themes. Any thought, emotion, word, or action that is self-defeating needs to be replaced with a positive, empowering one. Releasing and replacing one’s negative attitudes leads to greater self-esteem, awareness, confidence, and happiness, not to mention the added benefits of a highly effective immune system. Practice changing your negative themes because your outlook determines the success or failure of an action.

- 3. Be your own cheerleader. Give yourself a pep talk every morning and whenever you are coping with stresses. Present yourself with positive, inspiring thoughts. Your brain does not question your thoughts. Those stored thoughts then become the basis for actions. Positive statements uplift the spirits and help to convince you of your value.

- 4. Visualize future successes. Take a few moments during each day to picture yourself achieving a goal. Fantasize about the feelings associated with achievement, and think about the steps that lead to the goal. Picture yourself as a dynamic person and capable caregiver; it will help to provide the blueprint for future growth. Besides, it is fun to do.

- 5. Act the part. Visualize yourself as a person with confidence and ability. You will find that your actual level of confidence grows each time you project an image of self-assurance. Developing a positive outlook will serve you well.

Nurturing Yourself

A critical first step in the development of self-awareness is to recognize and tend to your own needs. To nurture someone is to encourage their development. Caregivers are expected to work hard for the welfare of their clients, but energy cannot be continually spent without being renewed. Care providers must function at a high level of wellness to provide the energy required by their clients. You have chosen to care for others, and part of the responsibility you accepted when making this decision was to care for yourself. To effectively care for your clients, you must first care for and nurture yourself (Box 8.6).

Principles and Practices for Caregivers

Health care providers seek to “instill hope, empower others, encourage independence, and help improve the other’s condition. When we are unable to achieve that, unable to alleviate suffering, we often experience a sense of frustration and failure” (Sherwood, 1992). When this frustration occurs repeatedly, we become emotionally worn or burned out, as many caregivers call it. Somehow each of us must find the balance between the moral duty to care amid the stress of constant suffering and the concern for one’s own well-being. Box 8.6 offers basic principles for maintaining oneself when caring for others. Using these guidelines will assist you in finding the balance between giving and renewing. Remember them, because they are the keys for replenishing the energies that you so freely share with others.

To nurture yourself requires more than food, water, sleep, and activity. To nourish the part of the self from which one’s therapeutic energies are drawn requires special renewal. Caregivers nurture themselves in different ways. Some turn to a special source of comfort, whereas others find renewal in the adventure of trying new things. Spending time alone recharges some; others need the challenge of physical activities, travel, or new relationships.

Research has pointed out the many benefits of daily meditation for stress reduction, relaxation, and renewal (Kabot-Zinn, 1994). Meditation, termed the relaxation response by Western medicine, is the practice of becoming still and quiet. Health care professionals who practice meditation for as little as 15 minutes per day find it a valuable source of renewal and stress reduction.

In this busy world, it is easy to lose sight of one simple fact: your ability to care for your clients depends on how well you care for yourself. How you choose to nurture and renew yourself is a matter of personal preference; the important thing is that you do it regularly and without guilt. A good diet, adequate exercise, and restful sleep must not be ignored, but the essence of caring must also be applied to the self. Caregivers need to be willing to accept, love, and nourish themselves as much as they do their clients.