6: Ventricular rhythms

Learning objectives

After reading this chapter, you should be able to:

- 1. Describe the electrocardiogram (ECG) characteristics, possible causes, signs and symptoms, and initial emergency care for premature ventricular complexes (PVCs).

- 2. Explain the terms bigeminy, trigeminy, quadrigeminy, and run as used to describe premature complexes.

- 3. Explain the difference between PVCs and ventricular escape beats.

- 4. Describe the ECG characteristics of ventricular escape beats.

- 5. Describe the ECG characteristics, possible causes, signs and symptoms, and initial emergency care for an idioventricular rhythm (IVR).

- 6. Explain the term pulseless electrical activity (PEA).

- 7. Describe the ECG characteristics, possible causes, signs and symptoms, and initial emergency care for an accelerated idioventricular rhythm (AIVR).

- 8. Explain the terms sustained and nonsustained ventricular tachycardia (VT), monomorphic VT, and polymorphic VT (PMVT).

- 9. Describe the ECG characteristics, possible causes, signs and symptoms, and initial emergency care for monomorphic VT.

- 10. Describe the ECG characteristics, possible causes, signs and symptoms, and initial emergency care for PMVT.

- 11. Describe the ECG characteristics, possible causes, signs and symptoms, and initial emergency care for ventricular fibrillation (VF).

- 12. State the purpose and indications for defibrillation.

- 13. Describe the ECG characteristics, possible causes, signs and symptoms, and initial emergency care for asystole.

Key terms

accelerated idioventricular rhythm (AIVR): Dysrhythmia originating in the ventricles with a rate between 41 and 100 beats per minute (beats/min).

asystole: A total absence of ventricular electrical activity.

atrioventricular (AV) dissociation: Any dysrhythmia in which the atria and ventricles beat independently (e.g., VT, complete AV block).

automated external defibrillator (AED): A machine with a sophisticated computer system that analyzes a patient’s heart rhythm using an algorithm to distinguish shockable rhythms from nonshockable rhythms and providing visual and auditory instructions to the rescuer to deliver an electrical shock, if a shock is indicated.

defibrillation: Delivery of an electrical current across the heart muscle over a very brief period to terminate an abnormal heart rhythm; also called unsynchronized countershock or asynchronous countershock because the delivery of current has no relationship to the cardiac cycle.

fusion beat: Beat that occurs because of simultaneous activation of one cardiac chamber by two sites (foci); in pacing, the ECG waveform that results when an intrinsic depolarization and a pacing stimulus coincide and both contribute to depolarization of that cardiac chamber.

interpolated PVC: PVC that occurs between two normally conducted QRS complexes and that does not disturb the next ventricular depolarization or sinoatrial (SA) node activity.

torsades de pointes (TdP): Type of PMVT associated with a prolonged QT interval; the QRS changes in shape, amplitude, and width and appears to twist around the isoelectric line, resembling a spindle.

ventricular tachycardia (VT): Dysrhythmia originating in the ventricles with a ventricular rate greater than 100 beats/min.

Introduction

The ventricles may assume responsibility for pacing the heart if the sinoatrial (SA) node fails to discharge, an impulse from the SA node is generated but blocked as it exits the SA node, the rate of discharge of the SA node is slower than that of the ventricles, or an irritable site in either ventricle produces an early beat or rapid rhythm. If the ventricles function as the heart’s pacemaker, they typically generate impulses at a rate of 20 to 40 beats per minute (beats/min) (Fig. 6.1).

The shape of the QRS complex is influenced by the site of origin of the electrical impulse. Typically, an electrical impulse that begins in the SA node, atria, or atrioventricular (AV) junction results in depolarization of the right and left ventricles at about the same time. The resulting QRS complex is usually narrow, measuring 0.11 second or less in duration.

If an area of either ventricle becomes ischemic or injured, it can become irritable. This irritability affects how impulses are conducted. Ventricular beats and rhythms can start in any part of the ventricles and may occur because of reentry, altered automaticity, or triggered activity (Garan, 2020). When an ectopic site within a ventricle assumes responsibility for pacing the heart, the electrical impulse bypasses the normal intraventricular conduction pathway, which results in stimulation of the ventricles at slightly different times. As a result, ventricular beats and rhythms usually have QRS complexes that are abnormally shaped and longer than normal (e.g., greater than 0.11 second). If the atria are depolarized after the ventricles, retrograde P waves may be seen.

Because ventricular depolarization is abnormal, ventricular repolarization is also abnormal and results in ST segment and T wave changes. The T waves are usually in a direction opposite that of the QRS complex; if the major QRS deflection is negative, the ST segment is usually elevated, and the T wave is positive (i.e., upright). If the major QRS deflection is positive, the ST segment is usually depressed, and the T wave is usually negative (i.e., inverted). P waves are usually not seen with ventricular dysrhythmias; however, if they are visible, they have no consistent relationship to the QRS complex (i.e., AV dissociation).

Premature ventricular complexes

How do I recognize them?

A PVC, also called a premature ventricular extrasystole, ventricular premature beat, or premature ventricular depolarization, arises from an irritable site (i.e., focus) within either ventricle. By definition, a PVC is premature, occurring earlier than the next expected beat of the underlying rhythm. The general ECG characteristics of PVCs include the following:

| Rhythm: | Irregular because of the early beats; if the PVC is an interpolated PVC, the rhythm will be regular |

| Rate: | Usually within normal range, but depends on the underlying rhythm |

| P waves: | Usually absent or, with retrograde conduction to the atria, may appear after the QRS (usually upright in the ST segment or T wave) |

| PR interval: | None with the PVC because the ectopic beat originates in the ventricles |

| QRS duration: | Usually 0.12 second or greater; T wave is usually in the opposite direction of the QRS complex |

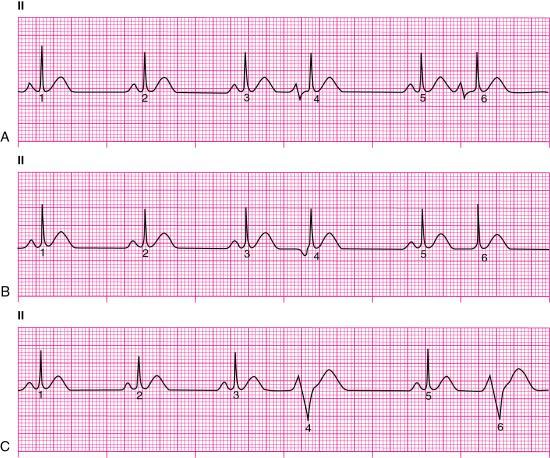

The shape of the QRS of a PVC depends on the location of the irritable focus within the ventricles (Fig. 6.2). The width of the QRS of a PVC is typically 0.12 second or greater because the PVC causes the ventricles to fire prematurely and in an abnormal manner (Fig. 6.3). The T wave usually points in a direction opposite that of the QRS complex.

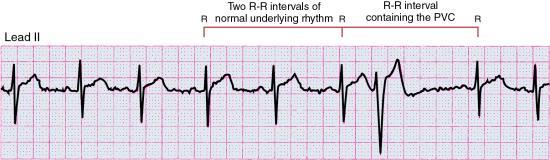

A compensatory pause often follows a PVC and occurs because the SA node is usually not affected by the PVC (Fig. 6.4). The SA node discharges at its regular rate and rhythm, including the period during and after the PVC. It is important to note that the presence of a full compensatory pause does not reliably differentiate ventricular ectopy from atrial ectopy; this is because atrial ectopy may produce a similar compensatory pattern if it does not reset the SA node (Crawford & Spence, 1995). In addition, when backward (i.e., retrograde) conduction occurs and a PVC is conducted to the atria, as in slow sinus rates, the PVC can reset the SA node, thereby resulting in a noncompensatory pause (Berger et al., 2016; Crawford & Spence, 1995).

A fusion beat is a result of an electrical impulse from a supraventricular site (e.g., SA node) discharging at the same time as an ectopic site in the ventricles (Fig. 6.5). Because fusion beats result from both supraventricular and ventricular depolarization, these beats do not resemble normally conducted beats, nor do they resemble true ventricular beats.

Patterns of premature ventricular complexes

PVCs may occur alone or in groups (i.e., patterns). Frequent PVCs are defined as the presence of at least 1 PVC on a 12-lead ECG or more than 30 PVCs per hour (Al-Khatib et al., 2018). PVCs that infrequently occur with no identifiable pattern are called isolated PVCs.

Two consecutive PVCs are called a pair or couplet (Fig. 6.6). Couplets are also referred to as “two PVCs in a row” or “back-to-back PVCs.” The appearance of couplets indicates the ventricular ectopic site is very irritable. Three or more sequential PVCs are termed a run, a salvo, or burst, and three or more PVCs that occur in a row at a rate of more than 100 beats/min is considered a run of VT.

Ventricular bigeminy describes a rhythm in which every other beat is a PVC (Fig. 6.7); with ventricular trigeminy, every third beat is a PVC; and with ventricular quadrigeminy, every fourth beat is a PVC.

Types of premature ventricular complexes

Uniform and multiform premature ventricular complexes

PVCs that look alike in the same lead and begin from the same anatomic site (i.e., focus) are called uniform PVCs (Fig. 6.8). PVCs that look different from one another in the same lead are called multiform PVCs (Fig. 6.9). The terms unifocal and multifocal are sometimes used to describe PVCs that are similar or different in appearance. Uniform PVCs are unifocal; that is, they arise from the same anatomic site within the ventricles. Multiform PVCs often, but do not always, arise from different anatomic sites; therefore, multiform PVCs are not necessarily multifocal (Goldberger et al., 2018). Multiform PVCs are generally considered more serious than uniform PVCs because they suggest a greater area of irritable myocardial tissue.

A PVC can occur with any supraventricular dysrhythmia. When identifying the rhythm, first describe the patient’s underlying rhythm and then describe the ectopic beats present (i.e., “Sinus tachycardia with uniform PVCs at 110 beats/min” or “Sinus tachycardia with multiform PVCs at 120 beats/min”).

Interpolated premature ventricular complexes

When a PVC occurs between two normally conducted QRS complexes without interfering with the normal cardiac cycle, it is called an interpolated PVC (Fig. 6.10). An interpolated PVC does not have a full compensatory pause; instead, it is squeezed between two normally conducted QRS complexes (i.e., the R-R intervals between sinus beats remain the same) and does not disturb the next ventricular depolarization or SA node activity. An interpolated PVC usually occurs when the PVC is very early or when the patient’s underlying heart rate is relatively slow.

R-on-T premature ventricular complexes

An R-on-T PVC occurs when the R wave of a PVC falls on the T wave of the preceding beat (Fig. 6.11). Because ventricular repolarization is not yet complete during the last half of the T wave (i.e., the relative refractory period), it is possible that a PVC that occurs during this period will precipitate VT or VF. R-on-T phenomenon refers to the start of a ventricular tachydysrhythmia because of an improperly timed electrical impulse on the T wave (Spotts, 2017).

What causes them?

PVCs are common, occurring in about 50% of all people with and without heart disease (Al-Khatib et al., 2018). They can occur at rest, or they can be associated with exercise. PVCs can occur for no apparent cause, and the frequency with which they occur increases with age. Frequent PVCs are associated with increased cardiovascular risk and increased mortality (Al-Khatib et al., 2018). The frequency of PVCs progressively increases during the first several weeks after a myocardial infarction (MI) and decreases at about 6 months (Miller et al., 2019). Common causes of PVCs include the following:

What do I do about them?

The signs and symptoms associated with PVCs vary, and their effect on cardiac output generally depends on their frequency. Some patients experiencing PVCs are asymptomatic; others may experience palpitations, lightheadedness, fatigue, or a pounding sensation in their neck or chest. Symptoms are particularly likely when they occur in patterns (e.g., bigeminy, trigeminy).

Treatment of PVCs depends on the cause, the patient’s signs and symptoms, and the clinical situation. Most patients experiencing PVCs do not require treatment with antiarrhythmic medications; rather, treatment of PVCs focuses on searching for and treating potentially reversible causes. For example, reassure the patient who complains of palpitations while searching for possible triggers for their PVCs (e.g., excessive caffeine ingestion, nicotine use, emotional stress). Ambulatory monitoring can help identify the type and frequency of ventricular ectopy. Beta-blockers, calcium blockers, and some antiarrhythmics may be prescribed to reduce symptoms of palpitations (Al-Khatib et al., 2018). In the setting of an acute coronary syndrome, treatment is directed at ensuring adequate oxygenation; relieving pain; and rapidly identifying and correcting hypoxia, heart failure, and electrolyte or acid–base abnormalities.

Ventricular escape beats or rhythm

How do I recognize it?

Remember that premature beats are early, and escape beats are late. We need to see at least two sinus beats in a row to establish the regularity of the underlying rhythm and to determine if a complex is early or late.

Although ventricular escape beats share some physical characteristics with PVCs (e.g., wide QRS complexes, T waves deflected in a direction opposite the QRS), they differ in some critical areas. A PVC appears early, before the next expected beat of the underlying rhythm. PVCs often reflect ventricular irritability. A ventricular escape beat occurs after a pause in which a supraventricular pacemaker failed to fire; thus, the escape beat is late, appearing after the next expected normal beat. A ventricular escape beat is a protective mechanism, safeguarding the heart from more extreme slowing or even asystole. Because it is protective, you do not want to administer any medication that would wipe out the escape beat.

The ECG characteristics of ventricular escape beats include the following:

| Rhythm: | Irregular because of late beats; the ventricular escape beat occurs after the next expected beat of the underlying rhythm |

| Rate: | Usually within normal range, but depends on the underlying rhythm |

| P waves: | Usually absent or, with retrograde conduction to the atria, may appear after the QRS (usually upright in the ST segment or T wave) |

| PR interval: | None with the ventricular escape beat because the ectopic beat originates in the ventricles |

| QRS duration: | 0.12 second or greater; the T wave is frequently in the opposite direction of the QRS complex |

Let’s take a look at Fig. 6.12. One of the first things you notice is that the rhythm is irregular at a rate of about 60 beats/min, and there is a QRS complex that differs from the others. Although this beat looks interesting, let’s use our systematic approach to examine the rhythm strip. There are upright P waves before beats 1, 2, 3, 5, and 6. Now we know that the underlying rhythm is sinus in origin. Next, let’s examine the wide-QRS beat more closely and see what happened here. Look to the left of the wide-QRS beat and see if anything looks amiss. When you look closely at the T wave of beat 3, it has an extra protrusion or hump. Now take a moment to plot P waves across the strip. You will find that this extra hump is an early P wave that was not conducted. This waveform is a nonconducted premature atrial complex (PAC). When plotting the P waves, notice that the wide-QRS complex occurred late—after the next expected sinus beat. This late complex is an escape beat. Because the QRS associated with it is wide, it is a ventricular escape beat. A junctional escape beat is also late, but it usually has a narrow QRS. Notice that the T wave of this beat is deflected in a direction opposite its QRS complex. When you look at the PR intervals and ST segment, you will find that the PR interval is longer than expected, measuring about 0.24 second. For now, we will simply say that it is prolonged. We will explore the reasons for this and give it a name in the next chapter. ST-segment depression is also present. Our interpretation of this rhythm strip would be something like this: “Sinus rhythm with a prolonged PR interval, nonconducted PAC, ventricular escape beat, and ST-segment depression at 60 beats/min.” My goodness! That was one complicated rhythm strip!

An IVR, also called a ventricular escape rhythm, exists when three or more ventricular escape beats occur in a row at a rate of 20 to 40 beats/min. The QRS complexes seen in IVR are wide because the impulses begin in the ventricles, bypassing the normal conduction pathway. Characteristics of IVR include the following:

| Rhythm: | Ventricular rhythm is essentially regular |

| Rate: | Ventricular rate 20 to 40 beats/min |

| P waves: | Usually absent or, with retrograde conduction to the atria, may appear after the QRS (usually upright in the ST segment or T wave) |

| PR interval: | None |

| QRS duration: | 0.12 second or greater; the T wave is frequently in the opposite direction of the QRS complex |

When the ventricular rate slows to less than 20 beats/min, some practitioners refer to the rhythm as an agonal rhythm or dying heart. An example of IVR is shown in Fig. 6.13.

What causes it?

A ventricular escape rhythm may occur if the SA node and the AV junction fail to initiate an electrical impulse; if the SA node or AV junction discharge at a rate less than that of the intrinsic rate of the Purkinje fibers; or if the impulses generated by a supraventricular pacemaker site are blocked. A ventricular escape rhythm may also result from an acute coronary syndrome, digitalis toxicity, or metabolic imbalances.

What do I do about it?

Because the ventricular rate associated with IVR is slow (i.e., 20 to 40 beats/min) with a loss of atrial kick, the patient may experience serious signs and symptoms because of decreased cardiac output. If the patient has a pulse and is symptomatic because of the slow rate, apply a pulse oximeter and administer supplemental oxygen if indicated. Establish intravenous (IV) access and obtain a 12-lead ECG. Atropine may be ordered to treat the symptomatic bradycardia. If atropine is administered, reassess the patient’s response and continue monitoring. Transcutaneous pacing (TCP) or a dopamine or epinephrine IV infusion may be ordered if atropine is ineffective. Ventricular antiarrhythmic medications should be avoided when managing patients with this rhythm. These drugs may abolish ventricular activity, possibly causing asystole in a patient with a ventricular escape rhythm.

If the patient is not breathing and has no pulse despite the appearance of organized electrical activity on the cardiac monitor, PEA exists. Therapeutic interventions for PEA include performing cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR), giving oxygen, starting an IV, administering epinephrine, possibly placing an advanced airway, and aggressively searching for the underlying cause (Box 6.1).

Accelerated idioventricular rhythm

How do I recognize it?

An accelerated idioventricular rhythm (AIVR) exists when three or more ventricular beats occur in a row at a rate of 41 to 100 beats/min (Fig. 6.14). ECG characteristics of AIVR include the following:

| Rhythm: | Ventricular rhythm is essentially regular |

| Rate: | 41 to 100 (41 to 120 per some cardiologists) beats/min |

| P waves: | Usually absent or, with retrograde conduction to the atria, may appear after the QRS (usually upright in the ST segment or T wave) |

| PR interval: | None |

| QRS duration: | 0.12 second or greater; the T wave is frequently in the opposite direction of the QRS complex |

AIVR is usually considered a benign escape rhythm. It appears when the sinus rate slows and disappears when the sinus rate speeds up. Episodes of AIVR usually last a few seconds to 1 minute. Because AIVR usually begins and ends gradually, it is also called nonparoxysmal VT. Fusion beats are often seen at the onset and end of the rhythm.

What causes it?

AIVR is often seen during the early hours of an acute MI, after successful reperfusion therapy, after interventional coronary artery procedures, or during the period following cardiac arrest. AIVR has also been observed in patients with the following:

What do I do about it?

AIVR generally requires no treatment because the rhythm is protective and often transient, spontaneously resolving on its own; however, possible dizziness, lightheadedness, or other signs of hemodynamic compromise may occur because of the loss of atrial kick. When treatment is indicated, apply a pulse oximeter and administer supplemental oxygen if indicated. Establish IV access and obtain a 12-lead ECG. IV atropine may be ordered to stimulate the SA node and improve AV conduction (Gildea & Levis, 2018). If atropine is given, reassess the patient’s response and continue monitoring.

Ventricular tachycardia

Ventricular tachycardia (VT) exists when three or more sequential PVCs occur at a rate of more than 100 beats/min. VT may occur with or without pulses, and the patient may be stable or unstable with this rhythm.

How do I recognize it?

VT may occur as a short run that lasts less than 30 seconds and spontaneously ends (i.e., nonsustained VT) (Fig. 6.15). Episodes of nonsustained VT may be recorded in up to 3% of apparently healthy individuals with no identifiable heart disease (Garan, 2020). The frequency with which nonsustained VT occurs increases with age and the presence and severity of underlying heart disease (Garan, 2020). In patients with heart disease, nonsustained VT is often a predictor of high risk for sustained VT or VF (Martin & Wharton, 2001).

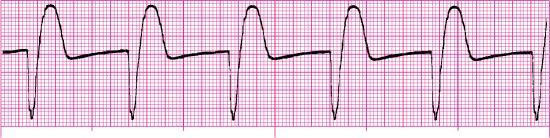

Sustained VT persists for more than 30 seconds or requires termination because of resulting hemodynamic compromise in less than 30 seconds (Al-Khatib et al., 2018) (Fig. 6.16). The rapid heart rate associated with sustained VT can cause a marked decrease in ventricular function and cardiac output, particularly in patients with underlying heart disease, resulting in acute heart failure, syncope, hypotension, or circulatory collapse within several seconds to minutes after the onset of VT (Garan, 2020).

Monomorphic ventricular tachycardia

Similar to PVCs, VT may originate from an ectopic focus in either ventricle. When the QRS complexes of VT are of the same shape and amplitude, the rhythm is called monomorphic VT (Fig. 6.17). Monomorphic VT with a ventricular rate of 150 to 300 beats/min is called ventricular flutter by some experts (Olgin et al., 2019). The ECG characteristics of monomorphic VT include the following:

| Rhythm: | Ventricular rhythm is essentially regular |

| Rate: | 101 to 250 (121 to 250 per some cardiologists) beats/min |

| P waves: | Usually not seen; if present, they have no set relationship with the QRS complexes that appear between them at a rate different from that of the VT |

| PR interval: | None |

| QRS duration: | 0.12 second or greater; often difficult to differentiate between the QRS and T wave |

What causes it?

Mechanisms of VT include disorders of impulse formation, such as altered automaticity or triggered activity, or disorders of conduction, such as reentry. Sustained monomorphic VT is often associated with chronic heart disease. Other possible causes of VT include the following:

- • Acid–base imbalance

- • Acute coronary syndromes

- • Cocaine or methamphetamine abuse

- • Electrolyte imbalance (e.g., potassium, calcium, magnesium)

- • Structural heart disease (e.g., ischemic heart disease, cardiomyopathy, valvular heart disease, adult congenital heart disease)

- • Trauma (e.g., myocardial contusion, invasive cardiac procedures)

- • Tricyclic antidepressant overdose

What do I do about it?

Signs and symptoms associated with VT vary. Because episodes of nonsustained VT come and go, they typically don’t cause symptoms; however, a beta-blocker may be prescribed if episodes are frequent and accompanied by symptoms such as palpitations or syncope. Because nonsustained VT is associated with an increased risk of death and other cardiovascular adverse outcomes, including stroke (Al-Khatib et al., 2018), patients should receive follow-up and ongoing management by a cardiologist. Ambulatory monitoring or use of an implanted cardiac monitor may be ordered to diagnose the dysrhythmia, ascertain its frequency, establish if it is the cause of the patient’s symptoms, and assess the patient’s response to treatment.

During sustained VT, the severity of the patient’s symptoms is related to several factors, including how rapid the ventricular rate is, how long the tachycardia has been present, current medications, the presence and extent of underlying heart disease, and the presence and severity of peripheral vascular disease (Olgin et al., 2019). The patient may experience palpitations, dizziness, chest discomfort, shortness of breath, or lightheadedness. Syncope, near-syncope, or a seizure may occur because of an abrupt onset of VT.

Monomorphic VT can degenerate into PMVT or VF, particularly when the ventricular rate is very fast or myocardial ischemia is present. Treatment is based on the patient’s signs and symptoms and the type of VT. In all cases, a search for the cause of the VT is essential. For example, VT that results from hypokalemia may be terminated with potassium replacement. When possible, obtain a 12-lead ECG before attempting pharmacologic or electrical conversion of the dysrhythmia; doing so enables proper rhythm interpretation, diagnosis, and treatment (De Ponti et al., 2017).

If the rhythm is monomorphic VT (and the tachycardia causes the patient’s symptoms):

- • CPR and defibrillation are used to treat the pulseless patient with VT.

- • Stable but symptomatic patients are treated with oxygen (if indicated), IV access, and ventricular antiarrhythmics (e.g., procainamide, amiodarone, sotalol) to suppress the rhythm. Procainamide should be avoided if the patient has a prolonged QT interval or signs of heart failure. Sotalol should also be avoided if the patient has a prolonged QT interval. Echocardiography is typically performed to assess cardiac structure and function in patients with structural heart disease.

- • Unstable patients (usually a sustained heart rate of 150 beats/min or more) are treated with oxygen, IV access, and sedation (if the patient is awake and time permits), followed by synchronized cardioversion.

After the acute event is resolved, the patient will require a thorough evaluation to identify the underlying cause, reduce the likelihood of recurrence of symptomatic sustained VT, and prevent sudden cardiac death. Interventions may include genetic testing, invasive cardiac imaging (e.g., cardiac catheterization, computed tomography angiography), electrophysiologic testing with possible catheter ablation, antiarrhythmic medications, or insertion of an implantable cardioverter-defibrillator.

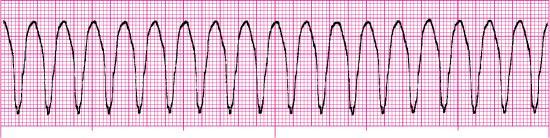

Polymorphic ventricular tachycardia

With PMVT, the QRS complexes vary in shape and amplitude from beat to beat and appear to twist from upright to negative or negative to upright and back, resembling a spindle (Fig. 6.18). The twisting may not always be seen, especially if the episode is nonsustained or if only a limited number of leads are available (Al-Khatib et al., 2018). PMVT is a dysrhythmia of intermediate severity between monomorphic VT and VF (Fig. 6.19). It may be challenging to distinguish PMVT from VF when the rate of PMVT is very fast (Garan, 2020). The ECG characteristics of PMVT include the following:

| Rhythm: | Ventricular rhythm may be regular or irregular |

| Rate: | Ventricular rate 150 to 300 beats/min; typically 200 to 250 beats/min |

| P waves: | None |

| PR interval: | None |

| QRS duration: | 0.12 second or more; there is a gradual alteration in the amplitude and direction of the QRS complexes; a typical cycle consists of 5 to 20 QRS complexes |

What causes it?

Several types of PMVT and their possible causes have been identified. Most PMVTs are associated with a normal QT interval (Jebberi et al., 2019) and are simply referred to as normal-QT PMVT. PMVT that occurs in the presence of a long QT interval (typically 0.45 second or more and often 0.50 second or more) is called torsades de pointes (TdP). A long QT interval may be congenital, acquired (typically precipitated by antiarrhythmic drugs that lengthen the QT interval or hypokalemia, which are often associated with bradycardia), or idiopathic (neither familial nor with an identifiable acquired cause). PMVT can occur in the presence of an abnormally short QT interval (typically less than 0.32 second). This type of PMVT is called short-QT PMVT. PMVT that occurs in the setting of an acute MI is associated with increased mortality (Virani et al., 2021).

What do I do about it?

The signs and symptoms associated with PMVT are usually related to the decreased cardiac output that occurs because of the fast ventricular rate. Signs of shock are often present. The patient may experience a syncopal episode or seizures. The rhythm may occasionally terminate spontaneously and recur after several seconds or minutes, or it may deteriorate to VF and cause cardiac arrest. The patient with sustained PMVT is rarely hemodynamically stable.

It is best to consult a cardiologist when treating a patient with PMVT because of the diverse mechanisms of PMVT, as there may or may not be clues as to its specific cause at the time of the patient’s presentation. Treatment options vary and can be contradictory. For example, a medication that may be appropriate for treating a patient with TdP may be contraindicated when treating a patient with another form of PMVT. In general, if the patient is symptomatic because of the tachycardia, treat ischemia (if it is present), correct electrolyte abnormalities, and discontinue any medications that the patient may be taking that prolong the QT interval. If the patient is stable, the use of IV amiodarone (if the QT interval is normal), magnesium, or beta-blockers may be effective, depending on the cause of the PMVT. Defibrillate if the patient is unstable or has no pulse.

Ventricular fibrillation

How do I recognize it?

VF is a chaotic rhythm that begins in the ventricles. In VF, there is no organized ventricular depolarization. The ventricular muscle quivers, and as a result, there is no effective myocardial contraction and no pulse. The resulting rhythm looks chaotic with deflections that vary in shape and amplitude. No normal-looking waveforms are visible. VF with waves that are 3 mm or more high is called coarse VF (Fig. 6.20). As VF continues, myocardial energy stores become depleted, and the amplitude of the fibrillating waves decreases. VF with low amplitude waves (i.e., less than 3 mm) is called fine VF (Fig. 6.21). In general, coarse VF is more likely to respond to defibrillation than fine VF. If untreated, VF will eventually degenerate to asystole. The ECG characteristics of VF include the following:

| Rhythm: | Rapid and chaotic with no pattern or regularity |

| Rate: | Cannot be determined because there are no discernible waves or complexes to measure |

| P waves: | None |

| PR interval: | None |

| QRS duration: | None |

Fig. 6.22 illustrates a comparison of ventricular dysrhythmias.

What causes it?

Factors that increase the susceptibility of the myocardium to fibrillate include the following:

- • Acute coronary syndromes

- • Dysrhythmias

- • Electrolyte imbalance

- • Environmental factors (e.g., electrocution)

- • Hypertrophy

- • Increased sympathetic nervous system activity

- • Proarrhythmic effect of antiarrhythmics and other medications

- • Severe heart failure

- • Structural heart disease (e.g., ischemic heart disease, cardiomyopathy, valvular heart disease, adult congenital heart disease)

- • Vagal stimulation

What do I do about it?

The patient in VF is unresponsive, apneic, and pulseless. The priorities of care in cardiac arrest resulting from pulseless VT or VF are high-quality CPR and defibrillation. Use the Hs and Ts to recall possible reversible causes of pulseless VT or VF. Administer medications and perform additional interventions per current resuscitation guidelines.

Defibrillation

Defibrillation is the delivery of an electrical current across the heart muscle over a very brief period to terminate an abnormal heart rhythm. Defibrillation is also called unsynchronized countershock or asynchronous countershock because current delivery has no relationship to the cardiac cycle. The shock attempts to deliver a uniform electrical current of sufficient intensity to depolarize myocardial cells (including fibrillating cells) at the same time. By briefly stunning the heart, an opportunity is provided for the heart’s natural pacemakers to resume normal activity. When the cells repolarize, the pacemaker with the highest degree of automaticity should assume pacing responsibility.

Manual defibrillation refers to the placement of adhesive pads on a patient’s chest, the interpretation of the patient’s cardiac rhythm by a trained health care professional, and the health care professional’s decision to deliver a shock, if indicated. Automated external defibrillation refers to the placement of pads on a patient’s chest and the interpretation of the patient’s cardiac rhythm by an automated external defibrillator (AED). The AED has a sophisticated computer system that analyzes a patient’s heart rhythm using an algorithm to distinguish shockable rhythms from nonshockable rhythms and providing visual and auditory instructions to the rescuer to deliver an electrical shock, if a shock is indicated. Defibrillation is indicated in the treatment of pulseless monomorphic VT, sustained PMVT, and VF.

Asystole (cardiac standstill)

How do I recognize it?

Asystole, also called cardiac standstill, is a total absence of atrial and ventricular electrical activity (Fig. 6.23). There is no atrial or ventricular rate or rhythm, no pulse, and no cardiac output. If atrial electrical activity is present, the rhythm is called P wave asystole or ventricular standstill (Fig. 6.24). The ECG characteristics of asystole include the following:

| Rhythm: | Ventricular not discernible; atrial may be discernible |

| Rate: | Ventricular not discernible, but atrial activity may be observed (i.e., P-wave asystole) |

| P waves: | Usually none |

| PR interval: | None |

| QRS duration: | Absent |

What causes it?

Use the Hs and Ts to recall possible reversible causes of asystole. Ventricular asystole may occur temporarily after the termination of a tachycardia with medications, defibrillation, or synchronized cardioversion (Fig. 6.25).

What do I do about it?

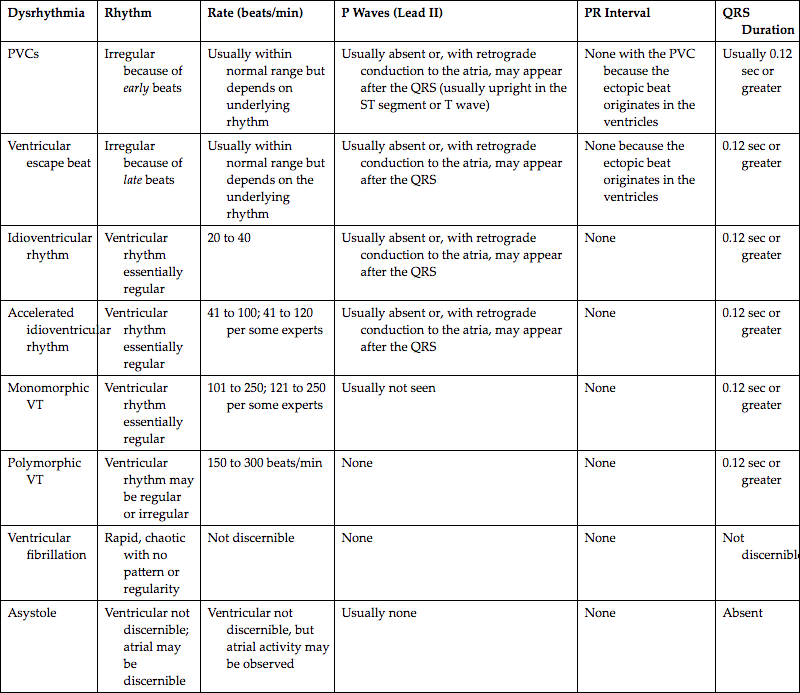

When asystole is observed on a cardiac monitor, quickly confirm that the patient is unresponsive and has no pulse, and then begin high-quality CPR. Additional care includes establishing vascular access, considering possible reversible causes of the arrest, administering medications (i.e., epinephrine), and performing additional interventions per current resuscitation guidelines. Defibrillation is not indicated in the treatment of asystole. A summary of ventricular rhythm characteristics appears in Table 6.1.

| Dysrhythmia | Rhythm | Rate (beats/min) | P Waves (Lead II) | PR Interval | QRS Duration |

| PVCs | Irregular because of early beats | Usually within normal range but depends on underlying rhythm | Usually absent or, with retrograde conduction to the atria, may appear after the QRS (usually upright in the ST segment or T wave) | None with the PVC because the ectopic beat originates in the ventricles | Usually 0.12 sec or greater |

| Ventricular escape beat | Irregular because of late beats | Usually within normal range but depends on the underlying rhythm | Usually absent or, with retrograde conduction to the atria, may appear after the QRS | None because the ectopic beat originates in the ventricles | 0.12 sec or greater |

| Idioventricular rhythm | Ventricular rhythm essentially regular | 20 to 40 | Usually absent or, with retrograde conduction to the atria, may appear after the QRS | None | 0.12 sec or greater |

| Accelerated idioventricular rhythm | Ventricular rhythm essentially regular | 41 to 100; 41 to 120 per some experts | Usually absent or, with retrograde conduction to the atria, may appear after the QRS | None | 0.12 sec or greater |

| Monomorphic VT | Ventricular rhythm essentially regular | 101 to 250; 121 to 250 per some experts | Usually not seen | None | 0.12 sec or greater |

| Polymorphic VT | Ventricular rhythm may be regular or irregular | 150 to 300 beats/min | None | None | 0.12 sec or greater |

| Ventricular fibrillation | Rapid, chaotic with no pattern or regularity | Not discernible | None | None | Not discernible |

| Asystole | Ventricular not discernible; atrial may be discernible | Ventricular not discernible, but atrial activity may be observed | Usually none | None | Absent |

PVC, Premature ventricular complex; VT, ventricular tachycardia.

Stop & review

Identify one or more choices that best complete the statement or answer the question.

- 1. Identify the ECG characteristics of an IVR.

- 2. A 74-year-old man experienced a syncopal episode at the grocery store. His blood pressure is 74/50 mm Hg, heart rate is 30 beats/min, and ventilatory rate is 18 breaths/min. Breath sounds are clear, his oxygen saturation on room air is 97%, and his blood glucose is normal. The cardiac monitor reveals a ventricular escape rhythm. Based on the information provided, which of the following are possible therapeutic interventions to consider?

- 3. How would you differentiate a junctional escape rhythm at 40 beats/min from an idioventricular rhythm at the same rate?

- a. It is impossible to differentiate a junctional escape rhythm from an idioventricular rhythm.

- b. The junctional escape rhythm will have a narrow QRS complex; the idioventricular rhythm will have a wide QRS complex.

- c. The rate (i.e., 40 beats/min) would indicate a junctional escape rhythm, not an idioventricular rhythm.

- d. The junctional escape rhythm will have a wide QRS complex; an idioventricular rhythm will have a narrow QRS complex.

- 4. The term for three or more PVCs occurring in a row at a rate of more than 100/min is

- 5. Which of the following are the priorities of care in cardiac arrest resulting from pulseless VT or VF?

- 6. Select the shockable cardiac arrest rhythms from the choices below.

- 7. The primary difference between a PVC and a ventricular escape beat is

- 8. Which of the following statements are true about asystole?

- a. Begin TCP as soon as the equipment is available.

- b. Defibrillation is the treatment of choice for this rhythm.

- c. Use the Hs and Ts when considering possible reversible causes of the rhythm.

- d. If a flat line is present but atrial activity is seen, the rhythm is called P wave asystole or ventricular standstill.

- 9. An 83-year old woman with a history of ischemic heart disease presents with a sudden onset of sustained monomorphic VT. Which of the following should be anticipated when caring for this patient?

- 10. Antiarrhythmics can cause a ___ effect, which means that they have the potential to cause serious adverse effects, more serious dysrhythmias, or both, than those that they were intended to treat.

- 11. Which of the following is a type of PVC that occurs between two normally conducted QRS complexes and does not disturb the next ventricular depolarization or SA node activity?

- 12. The ECG characteristics of monomorphic VT include

Ventricular rhythms—practice rhythm strips

Use the five steps of rhythm interpretation to interpret each of the following rhythm strips. All rhythms were recorded in lead II unless otherwise noted.

- 13. Identify the rhythm.

- Rhythm: __________________________ Rate: __________________________ P waves: _________________________

- PR interval: ______________________ QRS duration: _____________________ QT interval: _____________________

- Interpretation: _____________________________________________________________________________________

- 14. Identify the rhythm.

- Rhythm: __________________________ Rate: __________________________ P waves: _________________________

- PR interval: ______________________ QRS duration: _____________________ QT interval: _____________________

- Interpretation: _____________________________________________________________________________________

- 15. This rhythm strip is from a 63-year-old man who collapsed on the kitchen floor. He is unresponsive, apneic, and pulseless. His past medical history includes a coronary artery bypass graft 8 years ago and pacemaker implantation 5 years ago.

- 16. This rhythm strip is from a 1-month-old infant after a 3-minute seizure.

- Rhythm: __________________________ Rate: __________________________ P waves: _________________________

- PR interval: ______________________ QRS duration: _____________________ QT interval: _____________________

- Interpretation: _____________________________________________________________________________________

- 17. Identify the rhythm.

- Rhythm: __________________________ Rate: __________________________ P waves: _________________________

- PR interval: ______________________ QRS duration: _____________________ QT interval: _____________________

- Interpretation: _____________________________________________________________________________________

- 18. Identify the rhythm.

- Rhythm: __________________________ Rate: __________________________ P waves: _________________________

- PR interval: ______________________ QRS duration: _____________________ QT interval: _____________________

- Interpretation: _____________________________________________________________________________________

- 19. Identify the rhythm.

- Rhythm: __________________________ Rate: __________________________ P waves: _________________________

- PR interval: ______________________ QRS duration: _____________________ QT interval: _____________________

- Interpretation: _____________________________________________________________________________________

- 20. Identify the rhythm.

- Rhythm: __________________________ Rate: __________________________ P waves: _________________________

- PR interval: ______________________ QRS duration: _____________________ QT interval: _____________________

- Interpretation: _____________________________________________________________________________________

- 21. This rhythm strip is from a 73-year-old woman complaining of chest pain.

- Rhythm: __________________________ Rate: __________________________ P waves: _________________________

- PR interval: ______________________ QRS duration: _____________________ QT interval: _____________________

- Interpretation: _____________________________________________________________________________________

- 22. This rhythm strip is from a 25-year-old man with an altered mental status because of alcohol.

- Rhythm: __________________________ Rate: __________________________ P waves: _________________________

- PR interval: ______________________ QRS duration: _____________________ QT interval: _____________________

- Interpretation: _____________________________________________________________________________________

- 23. Identify the rhythm.

- Rhythm: __________________________ Rate: __________________________ P waves: _________________________

- PR interval: ______________________ QRS duration: _____________________ QT interval: _____________________

- Interpretation: _____________________________________________________________________________________

- 24. Identify the rhythm.

- Rhythm: __________________________ Rate: __________________________ P waves: _________________________

- PR interval: ______________________ QRS duration: _____________________ QT interval: _____________________

- Interpretation: _____________________________________________________________________________________

- 25. Identify the rhythm.

- Rhythm: __________________________ Rate: __________________________ P waves: _________________________

- PR interval: ______________________ QRS duration: _____________________ QT interval: _____________________

- Interpretation: _____________________________________________________________________________________

- 26. Identify the rhythm.

- Rhythm: __________________________ Rate: __________________________ P waves: _________________________

- PR interval: ______________________ QRS duration: _____________________ QT interval: _____________________

- Interpretation: _____________________________________________________________________________________

- 27. This rhythm strip is from a 47-year-old man with an altered mental status. His blood pressure is 118/86 mm Hg, and his blood sugar is 37 mg/dL.

- Rhythm: __________________________ Rate: __________________________ P waves: _________________________

- PR interval: ______________________ QRS duration: _____________________ QT interval: _____________________

- Interpretation: _____________________________________________________________________________________

- 28. This rhythm strip is from a 69-year-old man who is complaining of substernal chest pain. He rates his discomfort as 9/10.

- Rhythm: __________________________ Rate: __________________________ P waves: _________________________

- PR interval: ______________________ QRS duration: _____________________ QT interval: _____________________

- Interpretation: _____________________________________________________________________________________

- 29. This rhythm strip is from a 68-year-old man with a head injury after a fall.

- Rhythm: __________________________ Rate: __________________________ P waves: _________________________

- PR interval: ______________________ QRS duration: _____________________ QT interval: _____________________

- Interpretation: _____________________________________________________________________________________

- 30. This rhythm strip is from a 58-year-old man who was initially unresponsive, apneic, and pulseless.

- Rhythm: __________________________ Rate: __________________________ P waves: _________________________

- PR interval: ______________________ QRS duration: _____________________ QT interval: _____________________

- Interpretation: _____________________________________________________________________________________

- 31. Identify the rhythm.

- Rhythm: __________________________ Rate: __________________________ P waves: _________________________

- PR interval: ______________________ QRS duration: _____________________ QT interval: _____________________

- Interpretation: _____________________________________________________________________________________

- 32. This rhythm strip is from a 61-year-old woman who is complaining of shortness of breath.

- Rhythm: __________________________ Rate: __________________________ P waves: _________________________

- PR interval: ______________________ QRS duration: _____________________ QT interval: _____________________

- Interpretation: _____________________________________________________________________________________

- 33. Identify the rhythm.

- Rhythm: __________________________ Rate: __________________________ P waves: _________________________

- PR interval: ______________________ QRS duration: _____________________ QT interval: _____________________

- Interpretation: _____________________________________________________________________________________

- 34. Identify the rhythm.

- Rhythm: __________________________ Rate: __________________________ P waves: _________________________

- PR interval: ______________________ QRS duration: _____________________ QT interval: _____________________

- Interpretation: _____________________________________________________________________________________

- 35. Identify the rhythm.

- Rhythm: __________________________ Rate: __________________________ P waves: _________________________

- PR interval: ______________________ QRS duration: _____________________ QT interval: _____________________

- Interpretation: _____________________________________________________________________________________

- 36. Identify the rhythm.

- Rhythm: __________________________ Rate: __________________________ P waves: _________________________

- PR interval: ______________________ QRS duration: _____________________ QT interval: _____________________

- Interpretation: _____________________________________________________________________________________

- 37. This rhythm strip is from a 90-year-old unresponsive woman who has a history of heart failure.

- Rhythm: __________________________ Rate: __________________________ P waves: _________________________

- PR interval: ______________________ QRS duration: _____________________ QT interval: _____________________

- Interpretation: _____________________________________________________________________________________

Stop & review answers

- 1. A, C. The ECG characteristics of an idioventricular rhythm include an essentially regular ventricular rhythm with QRS complexes measuring 0.12 second or greater; P waves are usually absent or, with retrograde conduction to the atria, may appear after the QRS (usually upright in the ST segment or T wave); and a ventricular rate 20 to 40 beats/min.

- 2. A, B, C, D. Establish IV access and obtain a 12-lead ECG. Atropine may be ordered to treat the symptomatic bradycardia. TCP or a dopamine or epinephrine IV infusion may be ordered if atropine is ineffective. Ventricular antiarrhythmic medications (e.g., amiodarone, lidocaine, procainamide) should be avoided when managing patients with this rhythm. These drugs may abolish ventricular activity, possibly causing asystole.

- 3. B. A junctional escape rhythm has a narrow QRS complex and an intrinsic rate of 40 to 60 beats/min. An idioventricular rhythm has a wide QRS complex and an intrinsic rate of 20 to 40 beats/min.

- 4. C. Three or more sequential PVCs are termed a run or burst, and three or more PVCs that occur in a row at a rate of more than 100 beats/min are considered a run of VT.

- 5. A, B. The priorities of care in cardiac arrest resulting from pulseless VT or VF are high-quality CPR and defibrillation. Other interventions, such as administering medications and inserting and advanced airway, are less important.

- 6. A, D. VF and pulseless VT are shockable rhythms, which means that delivering a shock to the heart with a defibrillator may result in the termination of the rhythm. Asystole and PEA are nonshockable rhythms.

- 7. A. A PVC occurs before and a ventricular escape beat occurs after the next expected beat of the underlying rhythm.

- 8. C, D. Defibrillation is performed to briefly stun the heart with electrical current of sufficient intensity to allow the heart’s natural pacemakers to resume normal activity. With asystole, there is no electrical activity to reset. Similarly, TCP is not indicated. Instead, focus your efforts on performing high-quality CPR, establishing IV access, giving epinephrine, and using the Hs and Ts to identify possible reversible causes of the event. Asystole is also called cardiac standstill because there is a total absence of atrial and ventricular electrical activity. If a flat line is present and atrial activity is seen (i.e., P waves are present), the rhythm is called P wave asystole or ventricular standstill.

- 9. B, C, D, E. The rapid heart rate associated with sustained VT can cause a marked decrease in ventricular function and cardiac output, particularly in patients with underlying heart disease, resulting in acute heart failure, syncope, hypotension, or circulatory collapse within several seconds to minutes after the onset of VT.

- 10. D. Antiarrhythmics can cause a proarrhythmic effect, which means that they have the potential to cause serious adverse effects, more serious dysrhythmias, or both, than those that they were intended to treat.

- 11. D. An interpolated PVC occurs between two normally conducted QRS complexes and does not disturb the next ventricular depolarization or SA node activity.

- 12. B, C, D. ECG characteristics of monomorphic VT include a ventricular rhythm that is essentially regular, a ventricular rate of 101 to 250 beats/min, and a QRS that is 0.12 second or greater in duration. There is no PR interval associated with VT because the rhythm originates below the AV node.

Practice rhythm strip answers

Note: The rate and interval measurements provided here were obtained using electronic calipers.

- 13. Fig. 6.26

- Rhythm: Irregular

- Rate: 120 beats/min

- P waves: Positive, one precedes each QRS (sinus beats)

- PR interval: 0.13 second (sinus beats)

- QRS duration: 0.08 second (sinus beats)

- QT interval: 0.32 second (sinus beats)

- Interpretation: Sinus tachycardia at 120 beats/min with ventricular quadrigeminy; baseline artifact is present

- 14. Fig. 6.27

- 15. Fig. 6.28

- 16. Fig. 6.29

- 17. Fig. 6.30

- Rhythm: Irregular

- Rate: 70 beats/min

- P waves: Positive, one precedes each QRS before the sinus beats and the fusion beat

- PR interval: 0.16 second (sinus beats)

- QRS duration: 0.08 second (sinus beats)

- QT interval: 0.34 second (sinus beats)

- Interpretation: Sinus rhythm at 70 beats/min with a fusion beat, a pair of PVCs, ST-segment depression, and inverted T waves

- 18. Fig. 6.31

- Rhythm: Irregular; two rhythms are present

- Rate: 90 beats/min (sinus beats); 160 beats/min (VT) (because two rhythms are present, a rate for each should be documented)

- P waves: Positive, one precedes each QRS before the sinus beats; none visible with VT

- PR interval: 0.16 second (sinus beats)

- QRS duration: 0.10 second (sinus beats); 0.14 second (VT)

- QT interval: 0.33 second (sinus beats)

- Interpretation: Sinus rhythm at 90 beats/min, a fusion beat, and then monomorphic VT at 160 beats/min; baseline artifact is present

- 19. Fig. 6.32

- Rhythm: Irregular; two rhythms are present

- Rate: 60 beats/min (sinus beats); 300 to 375 beats/min (PMVT)

- P waves: Positive, one precedes each QRS before the sinus beats, one is notched; none visible with PMVT (because two rhythms are present, a rate for each should be documented)

- PR interval: 0.16 second (sinus beats)

- QRS duration: 0.09 second (sinus beats); 0.12 second (PMVT)

- QT interval: 0.40 second (sinus beats)

- Interpretation: Sinus rhythm at 60 beats/min to PMVT at 300 to 375 beats/min

- 20. Fig. 6.33

- Rhythm: Irregular

- Rate: 110 beats/min

- P waves: Positive, one precedes each QRS before the sinus beats; early and inverted in beats 5 and 11

- PR interval: 0.14 second

- QRS duration: 0.09 second (sinus beats)

- QT interval: 0.30 second (sinus beats)

- Interpretation: Sinus tachycardia at 110 beats/min with two PJCs (beats 5 and 11)

- 21. Fig. 6.34

- 22. Fig. 6.35

- Rhythm: Irregular

- Rate: 82 beats/min

- P waves: Positive, one precedes each QRS before the sinus beats; early with beat 6, distorting the T wave of beat 5

- PR interval: 0.19 second

- QRS duration: 0.10 second

- QT interval: 0.34 second

- Interpretation: Sinus rhythm at 82 beats/min with a PAC (beat 5); artifact is present

- 23. Fig. 6.36

- Rhythm: Irregular

- Rate: 70 beats/min

- P waves: Positive, one precedes each QRS before the sinus beats; none visible with beat 4

- PR interval: 0.21 second

- QRS duration: 0.11 second

- QT interval: 0.40 second

- Interpretation: Sinus rhythm at 70 beats/min with an interpolated PVC (beat 4) and inverted T waves; artifact is present

- 24. Fig. 6.37

- 25. Fig. 6.38

- Rhythm: Irregular to regular

- Rate: 143 to 167 beats/min (atrial beats); 150 beats/min with beats 11 through 16

- P waves: None visible

- PR interval: None

- QRS duration: 0.08 second (atrial beats)

- QT interval: 0.22 second

- Interpretation: Atrial fibrillation (AFib) at 143 to 167 beats/min with two ventricular complexes and a fusion beat, changing to supraventricular tachycardia (SVT) at 150 beats/min; ST-segment depression and artifact present

- 26. Fig. 6.39

- 27. Fig 6.40.

- 28. Fig. 6.41

- Rhythm: Irregular

- Rate: 80 beats/min

- P waves: Positive, one precedes each QRS with sinus beats; none with beats 2, 4, and 6

- PR interval: 0.18 second (sinus beats)

- QRS duration: 0.08 second (sinus beats)

- QT interval: 0.38 second (sinus beats) (difficult to clearly identify end of T waves)

- Interpretation: Sinus rhythm at 80 beats/min with uniform PVCs, artifact is present

- 29. Fig. 6.42

- 30. Fig. 6.43

- 31. Fig. 6.44

- Rhythm: Irregular

- Rate: Sinus rate 88 beats/min; overall rate about 110 beats/min

- P waves: Positive, one precedes each QRS with sinus beats; some are notched

- PR interval: 0.20 second (sinus beats)

- QRS duration: 0.08 second (sinus beats)

- QT interval: 0.36 second (sinus beats)

- Interpretation: Sinus rhythm at 88 beats/min with a run of VT and a PVC, ST-segment depression, and inverted T waves

- 32. Fig. 6.45

- Rhythm: Irregular

- Rate: 130 beats/min

- P waves: Positive, one precedes each QRS with sinus beats; none visible with beats 7 and 10

- PR interval: 0.12 second (sinus beats)

- QRS duration: 0.06 second (sinus beats)

- QT interval: Unable to determine because T waves are not visible

- Interpretation: Sinus tachycardia at 130 beats/min with multiform PVCs (beats 7 and 10)

- 33. Fig. 6.46

- 34. Fig. 6.47

- 35. Fig. 6.48

- Rhythm: Irregular

- Rate: 70 beats/min

- P waves: Positive, one precedes each QRS with sinus beats; none visible with beat 5

- PR interval: 0.20 second (sinus beats)

- QRS duration: 0.09 second (sinus beats)

- QT interval: 0.30 second (sinus beats)

- Interpretation: Sinus rhythm at 70 beats/min with an R-on-T PVC (beat 5) and ST-segment elevation

- 36. Fig. 6.49

- 37. Fig. 6.50

- Rhythm: Irregular

- Rate: 65 beats/min (sinus beats) to 167 to 214 beats/min (PMVT)

- P waves: Positive, one precedes each QRS with sinus beats; none visible with PMVT

- PR interval: 0.16 second (sinus beats)

- QRS duration: 0.10 to 0.12 second (sinus beats)

- QT interval: 0.32 second (sinus beats)

- Interpretation: Sinus rhythm at 65 beats/min with ST-segment depression to PMVT at 167 to 214 beats/min

References

Al-Khatib S.M, Stevenson W.G, Ackerman M.J, Bryant W.J, Callans D.J, Curtis A.B. & … Page R.L. 2017 AHA/ACC/HRS guideline for management of patients with ventricular arrhythmias and the prevention of sudden cardiac death J Am Coll Cardiol 14, 2018;72: e91- e220.

Berger M.G, Rubenstein J.C. & Roth J.A. Cardiac arrhythmias Andreoli & Carpenter’s Cecil essentials of medicine 9th ed 2016; Saunders Philadelphia, PA 110-135.

Crawford M.V. & Spence M.I. Electrical complications in coronary artery disease: Arrhythmias Common sense approach to coronary care 6th ed 1995; Mosby St. Louis, MO 220.

De Ponti R, Bagliani G, Padeletti L. & Natale A. General approach to a wide QRS complex Card Electrophysiol Clin 3, 2017;9: 461-485.

Garan H. Ventricular arrhythmias Goldman-Cecil medicine 26th ed 2020; Elsevier Philadelphia, PA 343-350.

Gildea T.H. & Levis J.T. ECG diagnosis: Accelerated idioventricular rhythm Perm J 2, 2018;22: 87-88.

Goldberger A.L, Goldberger Z.D. & Shvilkin A. Ventricular arrhythmias Goldberger’s clinical electrocardiography 9th ed 2018; Elsevier Philadelphia, PA 156-171.

Jebberi Z, Marazzato J, De Ponti R, Bagliani G, Leonelli F.M. & Boveda S. Polymorphic wide QRS complex tachycardia: Differential diagnosis Card Electrophysiol Clin 2, 2019;11: 333-344.

Martin D. & Wharton J.M. Sustained monomorphic ventricular tachycardia Cardiac arrhythmia: Mechanisms, diagnosis, and management 2nd ed 2001; Lippincott Williams & Wilkins Philadelphia, PA 573-601.

Miller J.M, Tomaselli G.F. & Zipes D.P. Diagnosis of cardiac arrhythmias Braunwald’s heart disease: A textbook of cardiovascular medicine 11th ed 2019; Elsevier Philadelphia, PA 648-669.

Olgin J, Tomaselli G.F. & Zipes D.P. Ventricular arrhythmias Braunwald’s heart disease—A textbook of cardiovascular medicine 11th ed 2019; Elsevier Philadelphia, PA 753-771.

Spotts V. Temporary transcutaneous (external) pacing AACN procedure manual for critical care 7th ed 2017; Elsevier St. Louis, MO 399-406.

Virani S.S, Alonso A, Aparicio H.J, Benjamin E.J, Bittencourt M.S, Callaway C.W. & … Tsao C.W. Heart disease and stroke statistics—2021 update: A report from the American Heart Association Circulation 8, 2021;143: e254- e743.

ECG Pearl

ECG Pearl