Basic Radiation Protection and Radiobiology

Kelli Welch Haynes, EdD, R.T.(R), FASRT

Today I was reading about Marie Curie

she must have known she suffered from radiation sickness

She died a famous woman denying her wounds

denying her wounds that came from the

same source as her power

Adrienne Rich“Power,” The Dream of a Common Language: Poems 1974–77

Objectives

- • Identify the sources of ionizing radiation.

- • List the units used to measure radiation exposure and their correct use.

- • Describe the sources of radiation exposure.

- • Explain the ways in which ionizing radiation interacts with matter.

- • List the permissible limits of exposure for occupational exposure and the general public.

- • Explain the reason for the varying sensitivity of human cells to ionizing radiation.

- • Describe the ways in which the entire body responds to varying amounts of radiation.

- • Discuss the various practices used to protect the patient from excessive radiation.

- • Discuss the various approaches used to protect an occupational worker from excess radiation.

- • Describe several devices used to detect and measure exposure to ionizing radiation.

Key Terms

Air Kerma SI quantity used to measure energy transferred from radiation to matter, which may be at the surface of a patient’s or radiologic and imaging sciences professional’s body

ALARA Mnemonic meaning to keep all radiation exposure as low as reasonably achievable

Becquerel (Bq) Unit of radioactivity in the International System of Units, equal to one disintegration per second

Classic Coherent Scattering Interaction with matter in which a low-energy photon (below 10 kiloelectron volts) is absorbed and released with its same energy, frequency, and wavelength but with a change of direction

Compton Scattering Interaction with matter in which a higher energy photon strikes a loosely bound outer electron, removing it from its shell, and the remaining energy is released as a scattered photon

Curie (Ci) Unit of radioactivity defined as the quantity of any radioactive nuclide in which the number of disintegrations per second is 3.7 × 1010

Exposure (X) the amount of radiation delivered to a point. Measured in coulomb per kilogram.

Germ Cells Cells of an organism whose function is to reproduce the organism (e.g., ovum, spermatozoa)

Gray (Gy) Unit in the International System used to measure the amount of energy absorbed in any medium; 1 Gy = 100 radiation absorbed doses

International System (SI) of Units System of units based on metric measurement developed in 1948 and having units used to measure radiation

Kiloelectron Volts (keV) Units of energy equal to 1000 electron volts

Photoelectric Interaction Interaction with matter in which a photon strikes an inner shell electron, causing its ejection from orbit with the complete absorption of the photon’s energy

Radiation Forms of energy emitted and transferred through matter

Sievert (Sv) Unit in the International System used to measure the dose equivalence, or biologic effectiveness, of differing radiations; 1 Sv = 100 rem

Somatic Cells All of the body’s cells except germ cells

X-rays Form of electromagnetic radiation traveling at the speed of light, possessing the ability to penetrate matter

IONIZING RADIATION

Whenever a radiologic and imaging sciences professional is applying ionizing radiation to produce a diagnostic image for the radiologist, they should remember the great responsibility this entails. Ionizing radiation is energy capable of penetrating matter and possesses sufficient energy to eject orbital electrons along its path, thus ionizing atoms. Exposure to radiation always involves a risk for biologic changes that cannot be ignored. The benefits of improved diagnosis of disease outweigh the risk, however, as long as the radiologic and imaging sciences professional is using sound judgment and always works to minimize the quantity of radiation the patient receives. The radiologic and imaging sciences professional must act to protect all persons from unnecessary radiation exposure, including themselves, the patient, and others within the clinical environment.

Sources of Ionizing Radiation

Although humans are exposed to radiation in everyday living, it is rarely given much thought. The two basic sources of ionizing radiation exposure are natural (or background) radiation and human-made (artificial) radiation sources. Background sources occur spontaneously in nature and are not affected by human activity. These forms include cosmic radiation from the sun and other planetary bodies and naturally occurring radioactive substances present on earth (such as uranium and radium), which can be inhaled or ingested through food, water, or air (radon). Sources of human-made radiation include the nuclear industry, radionuclides, medical and dental exposures, and some consumer products. The nuclear industry has contributed fallout from aboveground weapons testing, from accidents in nuclear power stations, and from the disposal of by-products from these plants. Exposure to radionuclides results from products containing radioactive elements, such as smoke detectors, and radiopharmaceuticals used in the diagnosis and treatment of disease. Medical and dental exposures constitute the greatest source of human-made radiation. In addition, certain consumer products such as video monitors, suntan beds, and microwave ovens contribute slightly to the annual US exposure. Because the radiologic and imaging sciences professional is primarily responsible for the application of medical ionizing radiation to patients, understanding the process by which x-rays interact with matter is important.

Human-Made Radiation

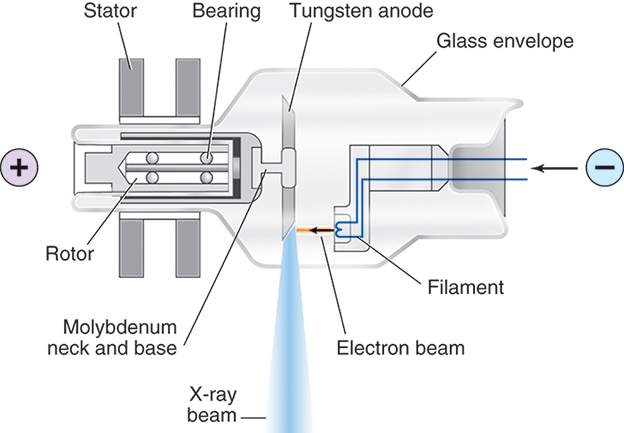

Human-made ionizing radiation, or x-rays as they are more commonly called, is a form of electromagnetic radiation that travels at the speed of light. Unlike particulate radiation, which is a liberated portion of a radioactive atom capable of traveling for short distances and reacting with matter, x-rays are bundles of energy moving as waves in space, depositing their energy randomly. For x-rays to be produced, three things must be present: (1) a source of electrons, (2) a means to rapidly accelerate the electrons, and (3) something to rapidly stop this movement. These conditions are all met by the x-ray tube and its electrical supply (Fig. 9.1). The tube itself is composed of a cathode, or negative terminal, and an anode, or positive terminal, enclosed in a special heat-resistant glass envelope to maintain the vacuum necessary for optimal x-ray production. The filament in the cathode assembly is composed of thoriated tungsten, which provides the source of electrons. When milliamperage (electric current) is applied to the filament, it responds by boiling off electrons through a process known as thermionic emission. Once kilovoltage (high voltage) is applied to the tube terminals, the electrons resulting from thermionic emission instantaneously accelerate toward the anode end of the tube. X-rays are produced when the electrons strike the anode, undergoing an energy conversion that produces both x-rays and heat. The resultant x-ray beam is heterogeneous—that is, it has many energies, measured in kiloelectron volts (keV). These x-rays, also known as the primary or useful beam, are directed toward the patient through a window in the tube. Once the x-rays strike matter, three possibilities exist: (1) they can be absorbed, (2) they can transfer some energy and then scatter, or (3) they can pass through unaffected.

Interactions of X-Rays With Matter

X-rays interact with matter in five ways: (1) classic coherent scattering, (2) photoelectric interaction, (3) Compton scattering, (4) pair production, and (5) photodisintegration. Classic coherent scattering, photoelectric absorption, and Compton scattering occur within the diagnostic range of x-ray energies, whereas pair production and photodisintegration occur in the therapeutic range of energies. Both Compton scattering and photoelectric interaction directly influence patient and occupational worker exposure. They are the way in which x-rays transfer their energy to living tissue. They constitute the basis for all patient exposure and the reason behind the need for protective measures.

Classic Coherent Scattering.

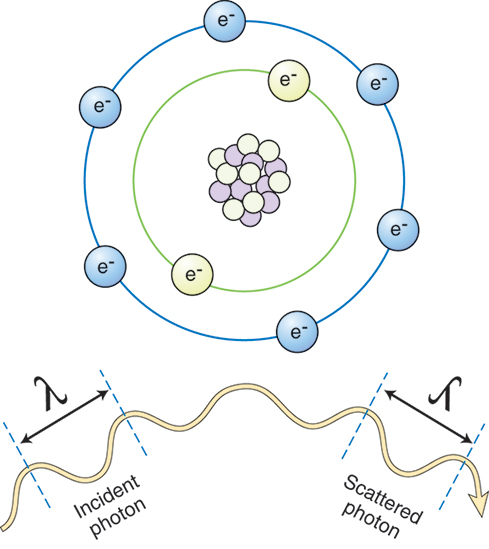

X-rays that possess energy levels below 10 keV can interact with matter through classic coherent scattering (Fig. 9.2). Also known as coherent, Thomson, or unmodified scattering, classic coherent scattering occurs when an incoming x-ray photon strikes an atom and is absorbed, causing the atom to become excited. The atom then releases the excess energy in the form of another x-ray photon possessing the same energy as the original photon, but proceeding in a different direction. This change in direction is known as scattering. Most of these scattered photons travel in a forward direction, stopping when they strike anything in their path. More importantly, classic coherent scattering results in no energy transfer to the patient.

Photoelectric Absorption.

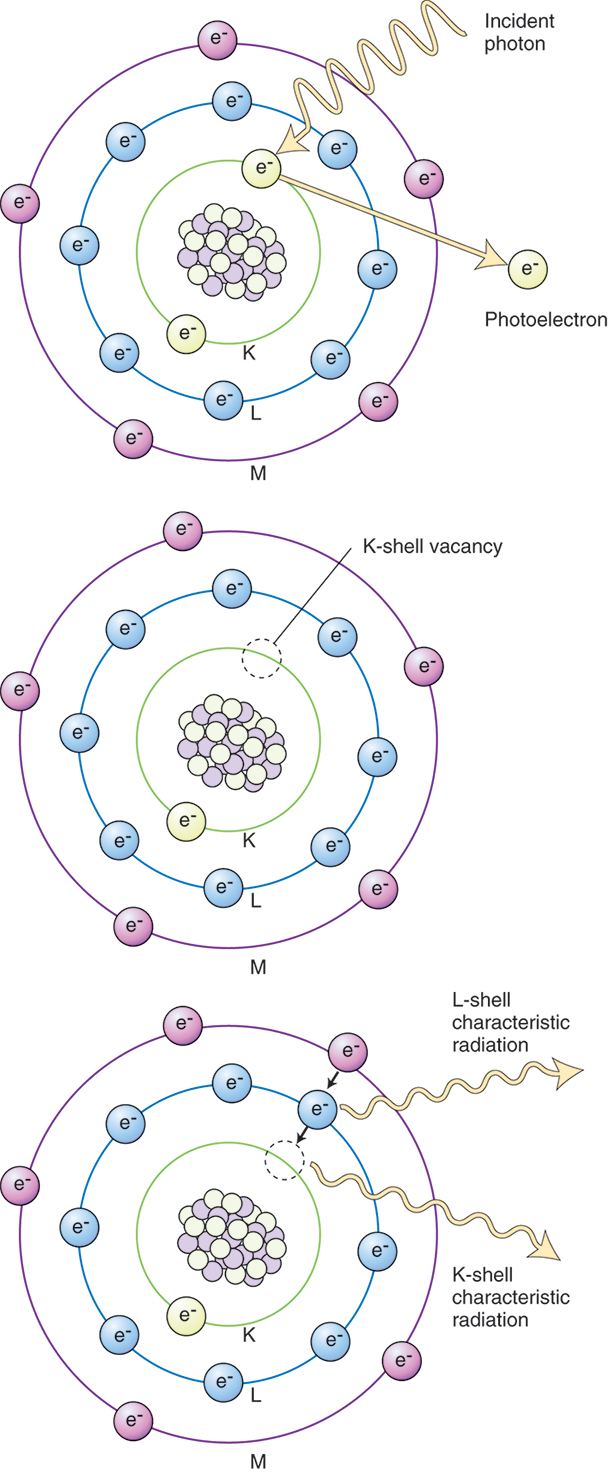

The second common interaction of x-rays with matter in the diagnostic range is the photoelectric absorption (Fig. 9.3). Photoelectric absorption occurs when an incoming x-ray photon strikes an inner shell electron and ejects it from its orbit around the nucleus of the atom, creating an ion pair. The atom, having lost an electron, is positively charged, and the released electron, referred to as the photoelectron, continues to travel until it combines with other matter. All the energy from the photon is completely consumed in this interaction; it is said that the energy is absorbed by the atom. As outer shell electrons transition to fill vacancies in inner shells, they release excess energy in the form of x-rays. X-rays originating within the body as a result of the photoelectric effect are collectively known as characteristic radiation and are the source of secondary radiation. Because complete energy absorption takes place in photoelectric interactions, this constitutes the greatest hazard to patients in diagnostic radiography.

Compton Scattering.

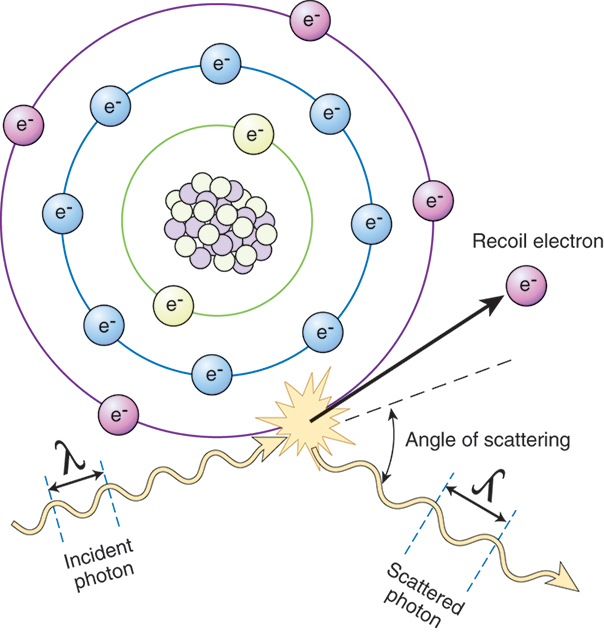

The last interaction common to the diagnostic x-ray range is the Compton effect (Fig. 9.4). The Compton effect, also known as modified or Compton scattering, occurs when an incoming x-ray photon strikes a target atom and uses a portion of its energy to eject an outer shell electron. The remainder of the photon’s energy proceeds in a direction different from that of the incoming photon. This process results in a Compton or recoil electron ejected from the outer shell, which travels until it combines with matter, and a photon of less energy that can react with the patient through further Compton or photoelectric interactions, or that can exit the patient and reach imaging equipment or the occupational worker. This interaction is also referred to as modified scattering, because the original photon possesses less energy after the interaction. The Compton effect is extremely important because it is responsible for a majority of occupational workers exposure to radiation.

Units of Measure

To quantify the amount of radiation a patient or occupational worker receives, a system of units has been developed. The units most commonly used since the 1920s are listed in Table 9.1. In 1948, the International Committee for Weights and Measures developed a system of units based on metric measurement. The SI units system (Système International d’Unitès, or International System [SI] of Units) was officially adopted in 1985.

Table 9.1

| Quantity | SI Unit | |

| Exposure (X) | Coulombs per kilogram (C/kg) | |

| Air Kerma | Gray (Gy) | |

| Absorbed Dose (D) (Efd) | Gray (Gy) | |

| Effective Dose (EfD) | Sievert (Sv) | |

| Dose Equivalent (EqD | Sievert (Sv) | |

| Radioactivity | Becquerel |

SI, Système International d'Unités (International System of Units).

Exposure (Coulomb per kilogram).

Exposure is the measure of ionization in air as a result of exposure to x-rays or gamma rays. It is defined as quantity of x-radiation or gamma radiation that produces the quantity of 2.08 × 109 ion pairs per cubic centimeter (cc) of air for a total charge of 2.58 × 10−4 coulombs per kilogram ()C/kg: coulomb is a quantity of electric charge). It does not indicate actual exposure to to individuals when absorbed.

Air Kerma (Kinetic Energy Released in Matter).

Air kerma is the kinetic energy transferred from a beam of radiation to air or tissue. It will replace the traditional quantity, exposure. Air kerma is the total kinetic energy released in a unit mass (kilogram) of air and is measured in joules per kilogram (J/kg), where 1 J/kg is 1 Gray (Gya).

Absorbed Dose (Gray).

As ionizing radiation passes through an object such as the human body, some of the energy of that radiation is absorbed by the body and stays within it. Absorbed dose is the radiation energy per unit mass and has units of J/kg or Gyt. The units Gya and Gyt refer to radiation dose in air and tissue, respectively. For a given air kerma (radiation exposure), the absorbed dose depends on the type of tissue being irradiated.

Effective Dose and Dose Equivelent (Sievert).

Effective dose is the best measure of the overall risk of exposure to humans from ionizing radiation. Effective dose is used for occupational exposure and is measured in Sieverts (Sv). The Sievert also expresses a patient dose that accounts for partial-body irradiation.

Dose equivelent, also measured in Sieverts, is the product of the average dose in a tissue or organ in the human body and its associated weighting factor, or quality factor. Not all types of radiation produce the same response in living tissue. Alpha particles, neutrons, and beta particles may produce a different degree of biologic damage than x-rays and gamma rays. To express accurately the biologic response of exposed individuals to the same quantity of differing radiations, the Sievert was developed. The Sievert is the unit of dose equivalence, expressed as the product of the absorbed dose in Sievert and a quality factor.

The quality factor varies, depending on the type of radiation being used. For example, the quality factor for x-rays is 1; therefore 1 Gy of x-ray exposure equals 1 Sv of dose equivalence.. The quality factor for fast neutrons is 10; thus 1 Gy of fast neutron exposure equals 10 Sv of dose equivalence (1 Gy × 10 = 10 Sv), meaning that neutrons are 10 times as biologically damaging as x-rays when their dose equivalents are compared. The Sievert (Sv) in SI units, which is defined as the product of the Gy and the quality factor.

Radioactivity Becquerel (Bq).

The measure of the rate at which a radionuclide decays is referred to as activity. The Becquerel (Bq) is the unit of quantity of radioactive material, not the radiation emitted by that material. One becquerel is that quantity of radioactivity in which a nucleus disintegrates every second (1 d/s = 1 Bq).This units are commonly employed in nuclear medicine and radiotherapy.

The traditional and SI units are compared in Table 9.1.

STANDARDS FOR REGULATION OF EXPOSURE

Because patients and radiologic technologists exposed to radiation are at risk for biologic effects, limits must be set to ensure safe practice for both the patient and the radiologic technologist. Guidelines and standards set by regulatory agencies must be followed. The Center for Devices and Radiological Health (CDRH), under the direction of the US Food and Drug Administration, sets and regulates the standards for radiation-producing equipment; it also continues to research possible ways of minimizing exposure to ionizing radiation. The National Council on Radiation Protection and Measurements (NCRP) is a not-for-profit organization formed by Congress in 1964 to collect and distribute information regarding radiation awareness and safe practice to the public. The NCRP is considered an advisory group, because it does not have the authority to enforce the recommendations contained within its reports. Enforcement is the responsibility of the Nuclear Regulatory Commission (NRC). The NCRP cooperates with other organizations to review, on an ongoing basis, the latest data on radiation units, measurements, and protection. The following information reflects the recommendations made by the NCRP, in cooperation with other organizations.

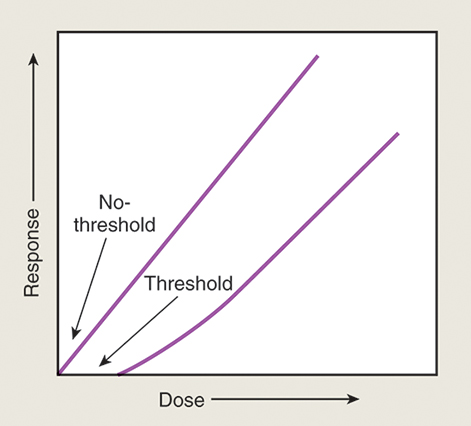

Effective dose limit recommendations have been set to minimize the biologic risk to exposed persons. The concept of a maximum permissible dose was traditionally used to describe the maximum dose of ionizing radiation that, if received by an individual, would carry a negligible risk for significant bodily or genetic damage. Currently the term effective dose limits is used, which takes into account various types of radiation exposure and tissue sensitivities. Dose limits were established for both the occupational worker and the general population. These recommendations follow two theories: nonthreshold and risk versus benefit (Fig. 9.5).

Nonthreshold indicates that no dose exists below which the risk of damage does not exist. Risk versus benefit governs the exposure of individuals when physicians ordered radiographic procedures. The benefit to the patient from performing those procedures must outweigh the risk of possible biologic damage. Because current studies indicate that an individual’s dose should be kept as low as reasonably achievable (ALARA), and that no dose is considered permissible. The NCRP has recommended certain effective dose limits, summarized in Table 9.2.

Table 9.2

| Population and Area of Body Irradiated | DOSE LIMITS | |

|---|---|---|

| SI Unit | ||

| Occupational Exposures | ||

| Effective Dose Limits | ||

| Annual | 50 mSv | |

| Cumulative | 10 mSv × age | |

| Equivalent Dose Annual Limits for Tissues and Organs | ||

| Lens of eyes | 150 mSv | |

| Skin, hands, and feet | 500 mSv | |

| Public Exposures (Annual) | ||

| Effective Dose Limit | ||

| Continuous or frequent exposure | 1 mSv | |

| Infrequent exposure | 5 mSv | |

| Equivalent Dose Limits for Tissues and Organs | ||

| Lens of eye | 15 mSv | |

| Skin, hands, and feet | 50 mSv | |

| Embryo-Fetal Exposures (Monthly) | ||

| Equivalent dose limit | 0.5 mSv | |

| Education and Training Exposures (Annual) | ||

| Effective dose limit | 1 mSv | |

| Equivalent Dose Limit for Tissues and Organs | ||

| Lens of eye | 15 mSv | |

| Skin, hands, and feet | 50 mSv | |

National Council on Radiation Protection and Measurements (NCRP): Limitation of exposure to ionizing radiation, NCRP Rep no. 116, Bethesda, MD, 1993, The Council.

SI, Système International d'Unités (International System of Units).

The annual whole-body effective dose limit for the occupational worker is 50 mSv. Currently the recommended maximum accumulated whole-body effective dose limit is 10 mSv × age in years (or 1 Sv × age in years). With this formula, a 40-year-old radiologic technologist may accumulate 1 Sv × 40, or 40 Sv (400 mSv) in their lifetime.

Anyone exposed to ionizing radiation not as a radiologic technologist is considered a member of the general population for radiation protection purposes. The whole-body dose-equivalent limit for the general population is one-tenth the occupational worker’s annual limit, or 5 mSv (0.5 rem).

BIOLOGIC RESPONSE TO IONIZING RADIATION

Ionizing radiation, absorbed by matter, undergoes energy conversions that result in changes in atomic structure. These changes, when considered in light of living tissue, can have major consequences on the life of any organism. To understand the necessity of protecting oneself and the patient from exposure to radiation, a basic review of cellular biology and how radiation interacts with cells is important.

Basic Cell Structure

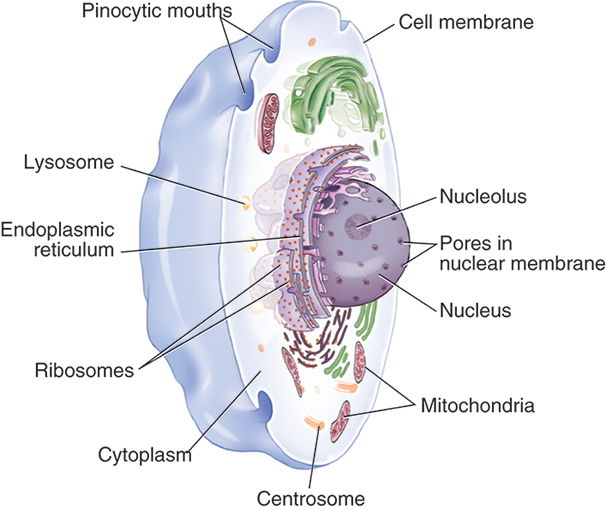

The cell is the simplest unit of organic protoplasm capable of independent existence. Simple organisms are composed of one or two cells; complex organisms are multicellular—that is, made of many cells. Although cells may differ from one another depending on their primary function, their structures are similar. Most cells are divided into two parts: (1) the nucleus and (2) the cytoplasm (Fig. 9.6). The nucleus is separated from the rest of the cell by a double-walled membrane called the nuclear envelope. This membrane has openings, or pores, that permit other molecules to pass back and forth between the nucleus and the cytoplasm. Most important, the nucleus contains the chromosomes, which are made up of genes. Genes are the units of hereditary information, composed of DNA, which is a double-stranded structure coiled around itself as a spiral staircase. It is one of the molecules at risk when a cell is exposed to ionizing radiation.

The cytoplasm of the cell is separated from its environment by the cell membrane. It contains several organelles responsible for the metabolic function of the cell. The cytoplasm itself is primarily water, which can undergo changes when struck by ionizing radiation.

Cell Types

Cells are of two types: (1) somatic cells and (2) germ cells. Somatic cells perform all the body’s functions. They possess two of every gene on two different chromosomes. Their chromosomes are paired, but each pair is different. Somatic cells possess a total of 46 chromosomes, or 23 pairs. They divide through the process of mitosis. Germ cells are the reproductive cells of an organism; they possess half the number of chromosomes as the somatic cells, for a total of 23. Germ cells reproduce through the process of meiosis.

Theories for Cellular Absorption of Ionizing Radiation

When a cell absorbs ionizing radiation, two basic theories exist to explain this interaction. The first theory, known as the direct hit theory, proposes that any type of radiation transfers its energy directly to the key molecule it has struck, resulting in the formation of ion pairs or elevation to an increased, excited energy state. Although any important structure can be hit by radiation, serious consequences arise when radiation interacts with DNA. Breaks in the bases or phosphate bonds can result in rearrangement or loss of genetic information, which can injure or kill the cell as it continues through its life cycle.

The other interaction with ionizing radiation is by indirect hit. Key molecules are affected by radiation depositing its energy elsewhere in the cell. Because cells are approximately 80% water, indirect action occurs when water molecules are ionized. This action produces chemical changes within the cell that alter the internal environment, injuring the cell, which can result in eventual cell death. With x-radiation and gamma radiation, the vast majority of cellular damage is the result of indirect hits.

Target Theory of Absorption of Ionizing Radiation

Both direct and indirect interactions with ionizing radiation apply to the target theory of absorption of ionizing radiation. Simply stated, certain molecules existing within a cell are key to the continued viability or life of that cell. Some of these molecules exist in great number; others in limited supply. If damage occurs to a molecule in abundant supply, the effect on the cell may not be as detrimental because others exist to maintain the function of the cell. Injury to a molecule in limited supply, however, can be life threatening, because no immediate replacement is available. The term target is used to describe any critical molecule, in this case the nucleus of a cell, that has undergone some interaction with ionizing radiation, either directly or indirectly. The target whose damage has serious consequences to the life of the cell is DNA.

Radiosensitivity of Cells

To study the cell’s response to radiation, a method of classification according to sensitivity was developed by Bergonie and Tribondeau in 1906. These researchers determined that mitotic activity and specific characteristics of each cell affected how the cell exhibited radiation damage. Cells are most sensitive to radiation during active division, when they are primitive in structure and function. Examples of radiosensitive cells include the basal cells of the skin, crypt cells of the small intestine, and germ cells. Cells resistant to radiation, being more specialized in structure and function, do not undergo repeated mitosis. These cells include nerve, muscle, and brain cells.

Ancel and Vitemberger, who modified this theory, stated that all cells possess the same sensitivity to radiation; the time of expression of injury is the factor that differs. This factor depends on mitosis and the external conditions in which the cell is placed. Therefore, rapidly dividing cells demonstrate the injury sooner and only appear as though they are more sensitive to radiation than those whose mitotic rate is slower. Organs composed of parenchymal cells that rapidly divide, such as skin or the small intestine, exhibit injury sooner than the esophagus or muscle, whose cells divide more slowly.

Response of Cells to Radiation

Cells respond to radiation in many ways. They die before beginning mitosis, delay entering mitosis, or fail to divide at their normal rate. Fortunately, cells also try to repair the damage sustained through absorption of ionizing radiation. This possibility depends on how sensitive the cell is to radiation, the type of damage sustained, the kind of radiation (particulate or electromagnetic), the exposure rate, and the total dose given. Incomplete repair can result in adverse biologic effects occurring after time has elapsed.

Total Body Response to Irradiation

The total body response of any organism to radiation depends on the effect on all the systems of the body. Because every system is different in its sensitivity or resistance, the total body response at a particular dose is defined by the system most affected. This response, known as acute radiation syndrome, occurs only when the organism is exposed fully (total body) to an external source of radiation given in a few minutes. Only then does the organism develop the full set of signs and symptoms that define each syndrome, which depends on the dose received.

Early Effects of Radiation Exposure.

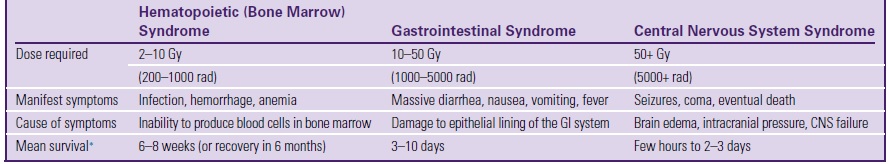

Three general stages of response exist for each acute radiation syndrome. The first is the prodromal stage, commonly referred to as the nausea, vomiting, and diarrhea stage. The second stage is the latent period, in which the organism feels well; however, during this time, the body is undergoing biologic changes that will lead to the final period, the manifest stage. Now the organism feels the full effects of the exposure, leading to either recovery or death (Table 9.3).

Table 9.3

| Hematopoietic (Bone Marrow) Syndrome | Gastrointestinal Syndrome | Central Nervous System Syndrome | |

| Dose required | 2–10 Gy | 10–50 Gy | 50+ Gy |

| (200–1000 rad) | (1000–5000 rad) | (5000+ rad) | |

| Manifest symptoms | Infection, hemorrhage, anemia | Massive diarrhea, nausea, vomiting, fever | Seizures, coma, eventual death |

| Cause of symptoms | Inability to produce blood cells in bone marrow | Damage to epithelial lining of the GI system | Brain edema, intracranial pressure, CNS failure |

| Mean survival∗ | 6–8 weeks (or recovery in 6 months) | 3–10 days | Few hours to 2–3 days |

Three radiation syndromes are (1) hematopoietic syndrome (also known as bone marrow syndrome), (2) gastrointestinal (GI) syndrome, and (3) central nervous system (CNS) syndrome. The hematopoietic syndrome occurs at doses of 2 to 10 Gy. Total body exposure results in infection, hemorrhage, and anemia. GI syndrome results from doses of 10 to 50 Gy. Individuals experience diarrhea, nausea, vomiting, and fever when subjected to these doses. CNS syndrome occurs at doses above 50 Gy, with the individual experiencing seizures, coma, and eventual death from increased intracranial pressure. Although these syndromes indicate serious, even lethal, consequences from exposure to radiation, an important point to remember is that these doses are far greater than those received by the occupational worker or patient.

Late Effects of Radiation Exposure.

Other effects of radiation exposure termed the late effects are equally important; these can develop over a long period after exposure. These effects result not only from high doses of radiation, but also from low doses administered over a longer time. Late effects are divided into two groups: (1) somatic effects, which develop in the individual exposed, and (2) genetic effects, which occur in future generations as a result of damage to the germ cells.

The two most frequently induced somatic effects are cataract formation and carcinogenesis. The lens of the eye is extremely sensitive to radiation, and studies have demonstrated the high incidence of cataract formation in laboratory animals exposed to radiation. In addition, survivors of the explosion of the atom bomb developed cataracts.

The most important late somatic effect is cancer development. The first documented case was the hand of a radiographer in 1902. Early radiologists, technologists, and researchers developed skin cancer and leukemia from prolonged exposure to ionizing radiation. Watch-dial painters developed osteosarcoma from ingesting radium when they put their paintbrushes in their mouths to draw the tip to a point. Miners who inhaled radioactive dust while digging for uranium developed lung cancer. All of these cases led to today’s strict limitations on radiation exposure.

Long-term genetic effects result from germ cells whose DNA has been altered by radiation exposure, meaning the effects are not seen in the exposed individual; instead, if an affected cell is fertilized and develops, the effects show up in future generations. These mutations—alterations in the DNA coding of the chromosome—are recessive. They appear only if the mutated cell is fertilized by another reproductive cell carrying the same mutation. This fact of genetics acts to minimize the appearance of possible radiation-induced changes.

EFFECTS OF RADIATION THERAPY

Every person will react differently to radiation therapy treatment. Side effects of radiation therapy will depend on the type and location of cancer, the dose of radiation given, and the patient’s general health. Some people have few or no side effects, while others may have quite a few side effects. Early side effects happen during or shortly after treatment. These side effects are typically short-term, mild, and treatable. The most common early side effects of radiation therapy include fatigue, nausea and vomiting, and skin changes such as dryness, itching, blistering or peeling. Cancer treatments may cause mouth, throat, and dental problems. Radiation therapy to the head and neck may harm the salivary glands and tissues in your mouth and/or make it hard to chew and swallow safely. Late side effects can take months or even years to develop. They can occur in any normal tissue in the body that has received radiation. The risk of late side effects depends on the area treated as well as the radiation dose that was used. Survivors of bone and soft-tissue cancers may have lose part or all of a limb. People who had radiation therapy or surgery to remove lymph nodes may develop lymphedema which is when lymph fluid builds up and causes swelling and pain. People who had certain surgeries in the pelvis or abdomen may not be able to develop infertility.

PROTECTING THE PATIENT

Although the patient must be exposed to ionizing radiation for a diagnostic image to be produced, care must be exercised to minimize the quantity of radiation exposure. The radiologic and imaging sciences professional has the responsibility of maximizing the quality of the imaging examination while minimizing the risk to the patient. Consequently, the concept of ALARA—as low as reasonably achievable—is used to guide technical factor selection when performing examinations of the patient. In particular, the cardinal principles of protection—time, distance, and shielding—are used to minimize patient exposure.

Time

When the radiologic and imaging sciences professional minimizes the length of time a patient remains in the path of the x-ray beam, one of the primary rules of protection is being applied. This goal is accomplished when the radiographer accurately applies the rules of radiographic technique to produce diagnostic images and uses technique charts to help determine the correct amount of radiation to direct toward the patient. The chances of repeated exposures are minimized, reducing the patient’s time in the path of the x-ray beam.

Distance

Another way to lessen patient dose is to maximize the distance between the radiation source and the patient. This increased distance lessens the entrance or skin dose to the patient. This action is not the most reasonable method to minimize patient dose, because the patient must be in the path of the ionizing beam for an image to be created. In addition, increasing distance requires an increase in technical factors to create an acceptable image.

Shielding

Due to technological advancements, such as improved detectors and generators, the use of patient gonadal and fetal shielding is being discontinued. Evidence shows that shielding provides negligible or no benefit and carries a risk of increasing patient dose and compromising the diagnostic efficacy of an image. Areas of the body that should be shielded from the useful beam whenever possible are the lens of the eye, breasts and the thyroid gland. Shields are made of lead, which has an atomic number of 82. Lead absorbs x-rays through the process of photoelectric effect, thereby minimizing patient exposure. Lead aprons should be used for additional patient shielding whenever the apron will not interfere with the anatomy of interest.

Additional Methods of Protection

Other factors specific to the production of x-rays can be manipulated with the purpose of minimizing patient exposure. These factors include beam restriction, image receptor speed, technical factor selection, and filtration. The radiographer must always restrict the primary beam to the anatomic area of interest, never exceeding the size of the image receptor used to capture the information. This restriction limits the exposure to the area undergoing radiography and does not increase the overall patient dose. Through the use of high-speed image receptors, a diagnostic image can be produced with reduced radiation, which minimizes patient exposure. In addition, selecting technical factors that use high kilovoltages increases the probability that Compton interactions will occur. This method results in a reduction of the energy being directly absorbed by the patient, creating a decrease in patient exposure. When reduced kilovoltage techniques are selected, an increased quantity of the radiation is completely absorbed within the patient, adding to the dose. Finally, filtration material in the path of the x-ray beam absorbs the low-energy x-rays that only add to the patient’s entrance dose. Eliminating their presence in the primary beam does not affect the finished image, because most do not exit the patient to reach the image receptor. Aluminum is the most common material used in filtration. Its atomic number and K-shell binding energies encourage photoelectric absorption of the low-energy x-rays.

PROTECTING THE RADIOLOGIC AND IMAGING SCIENCES PROFESSIONAL

The same principles of time, distance, and shielding are used to reduce the radiologic technologists exposure to radiation. This reduction is accomplished by minimizing the time spent in the room when ionizing radiation is being produced, using the greatest possible distance from the source of exposure and placing a shield between the worker and the radiation source.

Time

The radiographer should always spend the least amount of time possible in a room when a source of radiation is active. This risk exists only when exposures are being made; once the exposure is terminated, no radiation remains within the room or the contents of the room. The amount of dose received is directly related to the length of time spent with the source. During fluoroscopy, in which radiation is used for imaging dynamic structures, x-rays are emitted for longer periods. Therefore most units are equipped with 5-minute timers to alert the operator when the time has elapsed.

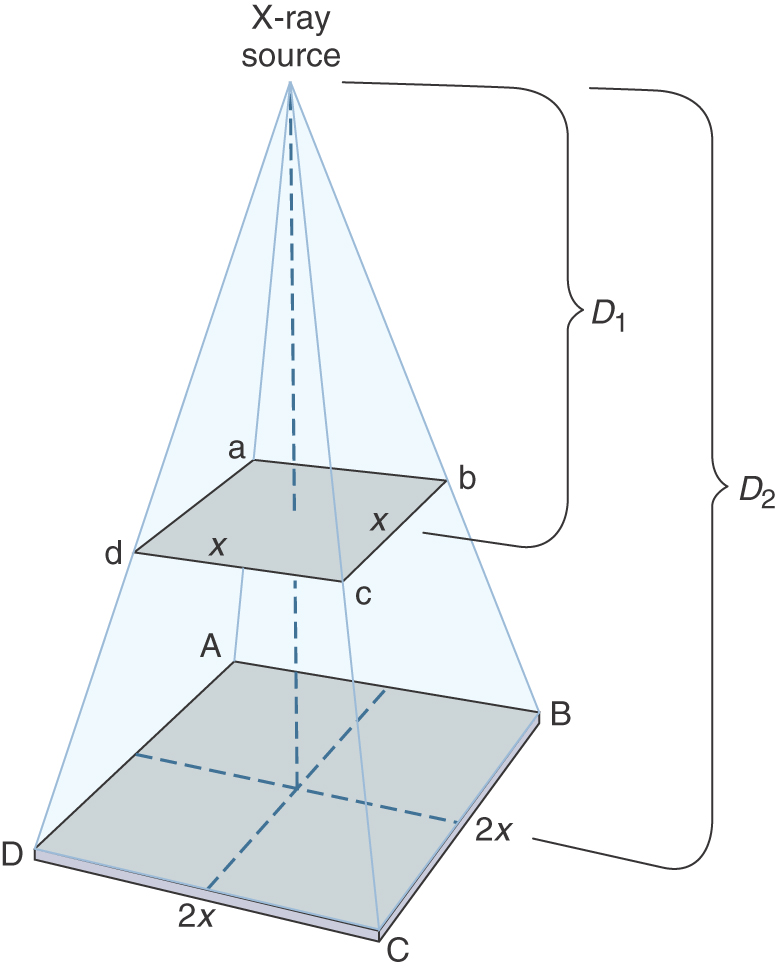

Distance

Distance is the best measure of protection for an occupational worker. The principle of the inverse square law states that the intensity of radiation varies inversely with the square of the distance. Simply stated, increasing the distance from the source of the x-ray beam greatly reduces the quantity of radiation that reaches the radiographer (Fig. 9.7). This reduction occurs because the x-rays leaving the tube spread out (diverge) and cover a much larger area, which in turn lessens their intensity. The following formula can be used to determine the exact exposure reaching the worker:

For example, if the intensity of radiation received by the radiographer were 20 Gy at a distance of 1 m from the tube, what then would the intensity be at a distance of 2 m from the tube, all other factors remaining the same? Solving for the new intensity, we get:

Doubling the distance between the radiologic and imaging sciences professional and the source of radiation reduces the exposure by a factor of 4 (now 1/4 the dose at the original distance). Conversely, if the distance from the source of radiation is reduced by 1/2, the exposure will increase to 4 times the original. Therefore distance is an extremely important factor in radiation protection.

The imaging sciences professional should not make a practice of holding a patient who cannot cooperate during a radiographic procedure. This circumstance places the radiologic technologist closer to the beam and to the patient, who is a source of scatter radiation from Compton interaction, and increases the time a radiologic and imaging sciences professional is near the source of radiation. Whenever possible, immobilization devices such as sandbags or restraint bands should be used. If these devices are ineffective or unavailable, assistance should be obtained from a nonoccupational worker such as a nurse, physician, or relative of the patient. The person who assists the patient must wear shielding devices to minimize his or her exposure.

Shielding

Although the practice of shielding the patients’ fetus and gonads is being discontinued, radiologic technologists should continue to shield themselves from radiation exposure. It is important to use shielding whenever time and distance alone cannot satisfactorily protect the worker. Lead is the material used in both fixed protective barriers and accessory devices such as aprons and gloves. Lead aprons and gloves should be worn when taking advantage of fixed barriers is impossible. Lead aprons are constructed of lead-impregnated vinyl, with a content of 0.25 to 1.0 mm of lead equivalency. However, it is recommended that aprons worn by personnel during fluoroscopic procedures be 0.5 mm of lead equivalency. The greater the amount of lead used, the better the protection offered to the radiographer. The greatest drawback to increased lead content is the increase in weight. The minimum permissible amount of lead equivalency for aprons used when the peak kilovoltage is 100 is 0.25 mm. Gloves usually possess the same minimum amount.

The shielding garments must be in good condition; cracked aprons and gloves do not successfully attenuate radiation. Protective apparel must be stored properly on specially designed racks so that cracks do not develop. To determine whether aprons or gloves adequately protect the wearer, they should undergo fluoroscopy at least once per year to check for damage.

Fixed protective barriers are part of the radiographic room construction and can be divided into primary and secondary barriers. Primary barriers are those that can be struck by the primary beam exiting the x-ray tube. Secondary barriers are those that can be struck only by secondary, scatter, or leakage radiation. A diagnostic radiologic physicist who considers the design and use of the room determines the exact quantity of lead or the equivalent thickness of concrete (Table 9.4).

Table 9.4

| Cardinal Principle | Patient | Technologist |

| Time | Minimize the length of time they are in the primary beam.

Consult technique charts and use shorter exposure times to avoid repeat exposures. During fluoroscopy, less beam “on” time. |

During fluoroscopy, spend the least amount of time in the room that is practical. |

| Distance | Maximize distance between the patient and the source of radiation.

SID should be at least 40 inches (100 cm). |

Increase the distance from the source of scatter (the patient) during fluoroscopic and mobile studies. |

| Shielding | Collimate the beam to the area of interest only.

Provide a lead apron to the patient if requested.∗ |

Wear lead aprons and thyroid shields during fluoroscopic and mobile studies.

Stand behind fixed or mobile barriers. |

SID, Source-to-image receptor distance.

∗If the shield will not interfere with visualizing the anatomy of interest.

Pregnant Student

Student pregnancy is covered under NRC regulations regarding the declared pregnant worker. Radiologic and imaging sciences programs accredited by the Joint Review Committee on Education in Radiologic Technology (JRCERT) must publish and make these regulations known to accepted and enrolled female students. Although guidelines for the exposure of pregnant women have been in place for many years, in 1994 the NRC in the United States became the first regulatory agency to limit the absorbed radiation dose to the unborn child. The dose limit is 5 mSv for the declared pregnant woman for the duration of her pregnancy. In addition, the NCRP recommends that once pregnancy is known, a limit of 0.5 mSv per month should apply. Should a pregnant student voluntarily disclose her pregnancy in writing to her program officials, a second dosimeter (fetal dosimetry badge) is issued and worn during energized laboratory sessions and clinical assignments.

Studies of average exposures of radiologic technologists indicate it is unlikely that the exposure of a pregnant student would exceed these limits. Consequently, little reason exists for the pregnant student to decide not to declare her pregnancy or to substantially alter her clinical assignments. Deciding what the risk to her fetus may be and taking precautions to avoid excessive radiation exposure are the responsibilities of the pregnant woman. Careful attention to the ALARA concepts of time, distance, and shielding are an important part of this decision.

As a result of US Supreme Court litigation designed to end sex discrimination against pregnant women in the workplace, American employers may not bar women of childbearing age from jobs because of potential risk to their fetuses. The NRC requires that all persons frequenting any portion of a restricted radiation area be instructed in the risks of radiation exposure to the embryo and fetus. (Restricted areas include diagnostic radiologic rooms, nuclear medicine laboratories, and any other area where ionizing radiation is applied to humans.) These instructions must include the right to declare or not declare pregnancy status. A declared pregnant woman is one who has voluntarily elected to declare her pregnancy. She is not under any regulatory or licensing obligation to do so. If a declaration is made, it must be in writing, be dated, and include the estimated month of conception. Acknowledgment of a pregnancy verbally or by visual observation does not meet the requirements of these regulations. Furthermore, the woman has the right to revoke her declaration of pregnancy. Until the proper declaration has been made, the total exposure dose limit is 50 mSv.

Current recommendations in the literature discourage moving a newly declared pregnant woman to an area of lower radiation exposure, because reassignments have the potential to increase the exposure of others who are not yet aware they are pregnant. ALARA radiation protection philosophy supports a schedule that evenly distributes exposure risk to all students at a relatively uniform monthly exposure rate to avoid substantial variations among individuals.

The NRC regulations require that a personnel monitor be used if the declared pregnant student could potentially receive 10% of the embryo or fetal dose limit. This amount would be 0.5 mSv for the entire pregnancy, or 0.05 mSv per month. In addition to the collar monitor, a second dosimeter (fetal badge) must be worn at waist level. During fluoroscopic procedures when a lead apron is worn, the fetal badge is worn at waist level under the lead apron.

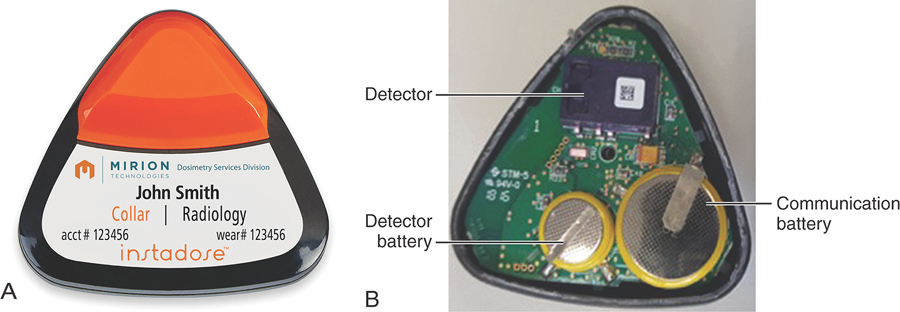

RADIATION MONITORING

Any occupational worker who is regularly exposed to ionizing radiation, who may potentially be exposed to 10% or more of the annual occupational effective dose limit of 50 milliSievert, must be monitored to determine estimated exposure. Dosimeters measure the quantity of radiation received based on conditions in which the radiologic and imaging sciences professional was placed. The most common personnel-monitoring devices are the optically stimulated luminescence (OSL) dosimeter, thermoluminescent dosimeter (TLD), and direct ion storage dosimeter.

Students entering clinical rotations or an energized laboratory will also be issued a dosimeter. This device should always be worn at collar level, outside of leaded apparel, facing forward. Each month, an exposure report will be received by the educational program, indicating the amount of exposure for the monitoring period. This report is maintained on file as part of the student’s permanent record. Programs accredited by the JRCERT are required to inform students of their radiation exposures in a timely manner.

Optically Stimulated Luminescence Dosimeters

The Luxel OSL dosimeter (Landauer) is the most common method used to monitor personnel exposure (Fig. 9.8). This type of dosimeter consists of a strip of aluminum oxide, a copper filter, an open window, a tin filter, and an imaging filter. The device is heat-sealed within a laminated, light-tight paper wrapper. The entire package is then sealed in a tamper-proof plastic blister pack. The front of the dosimeter provides information identifying the person wearing it, the name of the department, and a badge placement icon. To determine the individual’s exposure, the aluminum oxide is exposed to a laser light, which stimulates the aluminum oxide after use, causing it to become luminescent in proportion to the amount of radiation exposure, which determines the occupational worker’s exposure.

The OSL dosimeter can detect x-rays and gamma radiation in the range of 5 keV to in excess of 40 MeV. The dose measurement range is from .01 mSv to 1000 Sv. Doses less than .01 mSv are not detectable and reported as M, or minimal. Typically, the OSL dosimeter is worn for 2 months, but may be exchanged on a monthly basis. The holder should be worn between the collar and waist, on the front of the occupational worker. An advantage of this personal radiation monitoring device is that, because of the blister packaging, it is unaffected by heat, moisture, and pressure. The main disadvantage of this device is the inability to provide an immediate reading of the worker’s exposure; the dose can be determined only when the aluminum oxide is analyzed by the dosimetry company.

Thermoluminescent Dosimeters

Another device used to monitor personnel exposure is the TLD. It consists of a plastic holder containing crystals that absorb a portion of the energy they receive from a radiation exposure. When the device is exposed, the absorbed energy causes the outer valence electrons to be trapped in the forbidden zone, the region immediately past their resting orbit. The number of electrons elevated to this state depends directly on the amount of radiation received. When the time comes to determine the dose, these crystals are heated so that the trapped electrons return to their original resting state. This process results in a release of the extra energy in the form of a light photon. The light is collected and analyzed to determine the quantity of the dose received by the TLD.

The crystal most commonly used in TLDs is lithium fluoride. Once the lithium fluoride crystals have been heated (annealed), they can then be reused. The TLD provides readings as low as 0.05 mSv (Table 9.5).

Table 9.5

| Optically Stimulated Luminescence Dosimeters | Thermoluminescent Dosimeters | |

| Construction | Plastic holder containing sensing material, tin and copper filters, and an open window | Plastic holder containing crystals of sensing material |

| Sensing material | Strip of aluminum oxide crystals | Lithium fluoride crystals |

| Processing | Crystals are heated; light emitted is proportional to the dose received | Crystals are heated; light emitted is proportional to the dose received |

| Maximum wear time | Up to 2 months | Up to 3 months |

| Sensitivity | 0.01 mSv | 0.05 mSv |

Pocket Dosimeters

The last dosimetry device is the pocket direct ion storage (DIS) dosimeter, which is a small ionization gas filled dosimeter connected to a “solid state” device, with electrically erasable programmable read-only memory (EEPROM). EEPROMs are used in microprocessors and various consumer products to store small amounts of data will allowing some memory to be erased and reprogrammed to store more data. In the personnel dosimeter (Fig. 9.9), when radiation ionizes the gas in the ionization chamber, the cumulative electric charge is stored in the EEPROM and will remain in the device until “read out” by the introduction of a small control signal. The amount of charge stored in the device is directly proportional to the amount of radiation exposure that produced ionization in the chamber. The DIS dosimeter is read out through a physical connecting device such as a universal serial bus (USB) and the data can be stored electronically. The DIS dosimeter provides instant access to data and no need for the institution to collect and mail dosimeters to the manufacturer for the read out.

Field Survey Instruments

Other types of instruments are used to detect the presence of radiation and provide the user an indication of the intensity of the source. These devices are known as field survey instruments. A common instrument used to detect x-radiation, gamma radiation, and beta radiation is the Geiger-Müller counter, which is an ionization chamber constructed of an electrode housed within a chamber. The walls of the chamber are negatively charged, and the electrode is positive. When x-rays pass through the chamber and interact with the air, ionization occurs. Free electrons are attracted to the positively charged electrode, where they can be measured. The number of free electrons is directly proportional to the radiation exposure and can be displayed on a special meter that interprets this information and determines the exposure in coulombs per kilogram.

SUMMARY

- • Medical ionizing radiation is a form of electromagnetic radiation capable of penetrating matter and depositing energy as it travels. Although ionizing radiation can interact with matter in five ways, of particular importance to imaging are the photoelectric interaction and Compton effect. Both of these interactions contribute to the creation of the diagnostic image, and both contribute to the radiation exposure of the patient and the radiologic technologist.

- • The quantities of radiation important in radiography are exposure, air kerma, absorbed dose, effective dose and dose equivalent. The units used to are, air kerma, Gray, and Sievert.

- • Biologic changes that occur as a result of exposure to radiation begin at the cellular level. The effects depend on what type of cell was struck, how the energy was transferred, the type of radiation, and the sensitivity of the cell. The immediate response of the cell is to repair itself. However, when this self-repair is not possible, other changes begin to take place. These changes have an impact not only on the cells struck but also on all the systems that are composed of the cells. The effects resulting from exposure are either somatic, affecting the individual exposed, or genetic, affecting future generations through changes in germ cells. To minimize these changes, appropriate protective measures must be used.

- • To minimize patient exposure, the radiologic technologist must keep in mind all of the principles of image production that play a role in patient exposure. Examples of these factors are kilovoltage, image receptor speed, collimation, filtration, and repeated exposures. The radiologic technologist must also protect themself from unnecessary radiation through the use of the cardinal rules of protection—time, distance, and shielding. Finally, a record of the amount of radiation the occupational worker receives or to which they are exposed can be obtained by using monitoring devices such as OSLs, TLDs, and DIS dosimeters.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Bushong C: Radiologic science for technologists: physics, biology, and protection, ed 12, St. Louis, 2021, Elsevier.

Carlton RC, Adler AM: Principles of radiographic imaging: an art and a science, ed 7, Albany, NY, 2019, Cengage.

Dorland's illustrated medical dictionary, ed 31, Philadelphia, 2007, Saunders.

Hall EJ, Giaccia AJ: Radiobiology for the radiologist, ed 7, Philadelphia, 2012, Lippincott Williams & Wilkins.

Koontz BF: Radiation therapy treatment effects: An evidence-based guide to managing toxicity, 2019, Demon Medical.

Marsh RM, Silosky M: Patient shielding in diagnostic imaging: discontinuing a legacy practice, Am J Roentgenol 212(4):755–757, 2019. https://doi-org.nsula.idm.oclc.org/10.2201/AJR.18.20508

National Council on Radiation Protection: NCRP recommendations for ending routine gonadal shielding during abdominal and pelvic radiography, National Council on Radiation Protection Statement No. 13, 2019. Available at:https://ncrponline.org/wp-content/themes/ncrp/PDFs/Statement13.pdf

National Council on Radiation Protection and Measurements: SI units in radiation protection and measurements, NCRP Rep no. 82, Bethesda, MD, 1985, The Council.

National Council on Radiation Protection and Measurements: Recommendations on limits for exposure to ionizing radiation, NCRP Rep no. 91, 1987, Bethesda, MD, 1987, The Council.

National Council on Radiation Protection and Measurements: Limitation of exposure to ionizing radiation, NCRP Rep no. 116, Bethesda, MD, 1993, The Council.

Statkiewicz-Sherer MA, Visconti PJ, Ritenour ER, Haynes KW: Radiation protection in medical radiography, ed 9, St. Louis, 2021, Elsevier.

U.S. Food and Drug Administration: Radiation emitting products, Washington, DC, n.d., The Administration.

U.S. Nuclear Regulatory Commission: Instruction concerning prenatal radiation exposure, Regulatory guide 8.13, rev 2, Washington, DC, 1987, The Commission.

U.S. Nuclear Regulatory Commission: Standards for protection against radiation, 10 CFR Part 20, Washington, DC, 1994, The Commission.