Urine Specimen Types, Collection, and Preservation

After studying this chapter, the student should be able to:

- 1. State at least three clinical reasons for performing a routine urinalysis.

- 2. Describe three types of urine specimens, and state at least one diagnostic use for each type.

- 3. Explain the importance of accurate timing and complete collection of timed urine specimens.

- 4. Describe the collection technique used to obtain the following specimens:

- 5. Describe materials and procedures used for proper collection and identification of urine specimens.

- 6. Identify six reasons for rejecting a urine specimen.

- 7. State the changes possible in unpreserved urine, and explain the mechanism for each.

- 8. Discuss urine preservatives, including their advantages, disadvantages, and uses.

- 9. List and justify at least three tests that assist in determining whether a fluid is urine.

Key Terms1

The purposes of performing tests using urine are (1) to aid in the diagnosis of disease; (2) to screen for asymptomatic, congenital, or hereditary disease; (3) to monitor disease progression; and (4) to monitor therapy effectiveness or complications.1 Many urine tests are available in clinical and commercial laboratories. These tests may be quantitative assays that determine the level of a substance in the urine, such as assays that measure electrolytes, proteins, hormones, and other metabolic substances (e.g., porphyrins). Other urine tests are qualitative or screening tests. They are used to detect the presence or increased amount of a substance, such as rapid pregnancy tests, tests to detect microbial DNA and RNA (e.g., chlamydia, trichomonas), or a routine urinalysis—which provides a real-time “snapshot” of a person’s urinary tract and metabolic status.

The most commonly performed urine test is a routine urinalysis test. It is economical and provides valuable patient health information to healthcare providers. A routine urinalysis evaluates three aspects of the urine: 1) its physical characteristics, 2) its chemical composition, and 3) the microscopic sediment elements (e.g., epithelial cells, blood cells, casts, mucus) suspended in it. See Chapters 5, 6, and 7 for a detailed discussion of these three examinations that comprise a routine urinalysis.

To obtain accurate test results, urine specimen integrity must be maintained. If the urine specimen submitted for testing is inappropriate (e.g., if a random specimen is submitted instead of a timed collection) or if the specimen composition has changed because of improper storage conditions, testing will produce results that do not reflect the patient’s condition. In such situations, the highest quality reagents, equipment, expertise, and personnel cannot compensate for the unacceptable specimen. Therefore written criteria for urine specimen types, instructions for proper collection and preservation, appropriate specimen labeling, and a handling timeline must be available to all personnel involved in urine specimen procurement.

Why Study Urine?

Urine is actually a “fluid biopsy” of the kidneys and can provide a fountain of information about the health of an individual (Fig. 2.1). The kidneys are the only organs that can have their functional status evaluated by such a noninvasive means. In addition, because urine is an ultrafiltrate of the plasma, it can be used to evaluate and monitor body homeostasis and many metabolic disease processes.

Usually, urine specimens are readily obtainable, and their collection inconveniences a patient only briefly. Some individuals are uncomfortable discussing body fluids and body functions. Good verbal and written communication with each patient in a sensitive and professional manner can ensure the collection of a quality urine specimen. The ease with which urine specimens are obtained can lead to laxity or neglect in educating the patient and in stressing the importance of a proper collection. Note that if the quality of the urine specimen is compromised, so is the resultant urinalysis.

Specimen Types

The type of specimen selected, the time of collection, and the collection technique are usually determined by the tests to be performed. The three basic types of urine specimens are first morning, random, and timed collections (Table 2.1). Note that the ideal urine specimen needs to be adequately concentrated to ensure, upon screening, the detection of chemical components and formed elements of interest. These factors also depend on the patient’s state of hydration and the length of time the urine is held in the bladder.

First Morning Specimen

To collect a first morning specimen, the patient voids before going to bed and immediately on rising from sleep collects a urine specimen. Because this urine specimen has been retained in the bladder for approximately 8 hours, the specimen is ideal to test for substances that require concentration or incubation for detection (e.g., nitrites, protein) and to confirm postural or orthostatic proteinuria. Formed elements such as white blood cells, red blood cells, and casts are more stable in these concentrated acidic urine specimens. Because the number of epithelial cells present can be significant, these specimens may be used for cytology studies. The high osmolality of first morning specimens maintains the morphology of cellular components and reduces degeneration of renal casts.2 However, the high concentration of salts in these specimens can crystallize on cooling to room temperature (e.g., amorphous urates) and interfere with routine processing for cytologic studies. If the cellular morphology in this specimen type is determined to be suboptimal (i.e., signs of degeneration present), a random urine specimen can be collected.

Although the first morning urine is usually the most concentrated and is frequently the specimen of choice, it is not the most convenient to obtain. It requires that the patient pick up a container and instructions at least 1 day before his or her appointment; in addition, the specimen must be preserved if it is not going to be analyzed within 2 hours of collection.

Random Urine Specimen

For ease and convenience, routine screening is most often performed on random urine specimens. Random specimens can be collected at any time, usually during daytime hours and without prior patient preparation. Because excessive fluid intake and strenuous exercise can directly affect urine composition, random urine specimens may not accurately reflect a patient’s condition. Despite this, random specimens are usually satisfactory for routine screening and are capable of detecting abnormalities that indicate a disease process.

With prior hydration of the patient, a random clean catch urine specimen is ideal for cytology studies. Hydration consists of instructing the patient to drink 24 to 32 ounces of water each hour for 2 hours before urine collection. Most cytology protocols require collection of these specimens daily for 3 to 5 consecutive days. This increases the number of cells studied, thereby enhancing the detection of abnormality or disease. One method that can be used to increase the cellularity of a urine specimen is to have the patient exercise for 5 minutes by skipping or jumping up and down before specimen collection.

Timed Collection

Because of circadian or diurnal variation in excretion of many substances and functions (e.g., hormones, proteins, glomerular filtration rate) and the effects of exercise, hydration, and body metabolism on excretion rates, quantitative urine assays often require a timed collection. Timed collections, usually 12-hour or 24-hour, eliminate the need to determine when excretion is optimal and allow comparison of excretion patterns from day to day. Timed urine specimens can be divided into two types: those collected for a predetermined length of time (e.g., 2 hours, 12 hours, 24 hours) and those collected during a specific time of day (e.g., 2 PM to 4 PM). For example, a 4-hour or 12-hour specimen for determination of urine albumin, creatinine, and the albumin-to-creatinine ratio can be collected anytime and is an ideal specimen to screen for microalbuminuria. In contrast, a 2-hour collection for determination of urinary urobilinogen is preferably collected from 2 PM to 4 PM—the time when maximal excretion of urobilinogen is known to occur (in most individuals).

Accurate timing and strict adherence to specimen collection directions are essential to ensure valid results from timed collections. For example, if the two first morning specimens are included in a single 24-hour collection, the results will be erroneous because of the additional volume and analyte added. Box 2.1 summarizes a protocol for the timed collec-tion of a 24-hour specimen. This same protocol is applicable to any timed collection. A rule of thumb is to empty the bladder and discard the urine at the beginning of a timed collec-tion and to collect all urine subsequently passed during the collection period. At the end time of the collection, the patient must empty his or her bladder and include that urine in the timed collection.

Depending on the analyte being measured, a urine preservative may be necessary to ensure its stability throughout the collection. In addition, certain foods and drugs can affect the urinary excretion of some analytes. When this influence is known to be significant, the patient needs to be properly instructed to avoid these substances. Written instructions should include the test name, the preservative required, and any special instructions or precautions. The most common errors encountered in quantitative urine tests are related directly to specimen collection or handling, such as loss of specimen (i.e., not collecting all urine excreted in a timed collection), inclusion of two first morning samples, inaccurate total volume measurement, transcription error, and inadequate preservation.

Collection Techniques

Routine Void

A routine voided urine specimen requires no patient preparation and is collected by having the patient urinate into an appropriate container. Normally the patient requires no assistance other than clear instructions. These routine specimens, whether random or first morning, can be used for routine urinalysis. For other collection procedures, the patient may require assistance, depending on the patient’s age and physical condition or the technique to be used for collection (Table 2.2).

Midstream “Clean Catch”

If the possibility of contamination (e.g., from vaginal discharge) exists, or if a bacterial culture is desired, a midstream “clean catch” specimen should be obtained. Collec-tion of these specimens requires additional patient instructions, cleaning supplies, and perhaps assistance for elderly patients or young children. The Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI) provides instruction details for male and female patients in the document titled Urinalysis: Approved Guideline.1

In brief, before collection of a midstream clean catch specimen, the glans penis of the male or the urethral meatus of the female is thoroughly cleansed and rinsed. After the cleansing procedure, a midstream specimen is obtained when the patient first passes some urine into the toilet and then stops and urinates the midportion into the specimen container. Any remaining urine is passed into the toilet. To prevent contamination of the container and specimen, the interior of the container must not come in contact with the patient’s hands or perineal area. This midstream technique allows passage of the initial urine that contains any urethral washings (e.g., normal bacterial flora of the distal urethra) into the toilet and allows collection of a specimen that represents elements and analytes from the bladder, ureters, and kidneys. Because an informed patient can obtain these useful specimens with minimal effort, the midstream clean catch specimen is frequently collected. When done properly, the technique eliminates sources of contamination and provides an excellent specimen for routine urinalysis and urine culture.

Catheterized Specimen

A routine voided or midstream clean catch specimen is readily obtained by a well-instructed and physically able patient. In contrast, two collection techniques require medical personnel. A catheterized specimen is obtained after catheterization of the patient—that is, insertion of a sterile catheter through the urethra into the bladder. Urine flows directly from the bladder through the indwelling catheter and accumulates in a plastic reservoir bag. A urine specimen can be collected at any time from this reservoir. Because urinary tract infections are common in catheterized patients, these urine specimens are often used for bacterial culture. When a single catheterized urine specimen is received for multiple tests (e.g., routine urinalysis, bacterial culture, urine total protein, urine drug tests) and the culture cannot be performed first, steps must be taken to prevent contamination of the urine specimen. This usually involves transferring aliquots of the urine specimen using sterile technique into additional containers for the other tests requested. Any of the specimen types discussed (e.g., random, timed) can be obtained from catheterized patients by following the appropriate collection procedure.

Studies to determine whether one or both kidneys are involved in a disease process can involve collection of urine directly from the ureters. A catheter is inserted up the urethra, through the bladder, and into each individual ureter, where urine is collected. Urine collected from the left ureter and the right ureter is analyzed, and the results are compared.

Suprapubic Aspiration

Another collection technique, suprapubic aspiration, involves collecting urine directly from the bladder by puncturing the abdominal wall and the distended bladder using a needle and syringe. The normally sterile bladder urine is aspirated into the syringe and sent for analysis. This procedure is used principally for bacterial cultures, especially for anaerobic microbes, and in infants, in whom specimen contamination is often unavoidable.

Pediatric Collections

Newborns, infants, and other pediatric patients pose a challenge in collecting an appropriate urine specimen. Because these patients are unable to urinate voluntarily, commercially available plastic urine collection bags with a hypoallergenic skin adhesive are used. The patient’s perineal area is cleansed and dried before the specimen bag is placed onto the skin. The bag is placed over the penis in the male and around the vagina (excluding the anus) in the female, and the adhesive is firmly attached to the perineum. Once the bag is in place, the patient is checked every 15 minutes to see if an adequate volume of urine has been collected. The urine specimen should be removed as soon as possible after collection, labeled, and transported to the laboratory. Because of the many possible sources of contamination despite the use of sterile bags and technique, urine for bacterial culture may need to be obtained by catheterization or suprapubic aspiration. However, when the patient is prepared appropriately, these bag specimens are usually satisfactory for routine screening and quantitative assays. The use of disposable diapers to collect urine for quantitative assay also has been reported.3 Note that urine absorbed into a diaper or other absorbent material is not acceptable for the microscopic examination portion of a routine urinalysis (see subsection Reasons for Urine Specimen Rejection).

Reasons for Urine Specimen Rejection

A urine specimen may be rejected for testing for a variety of reasons (Box 2.2). Each laboratory should have a written protocol that lists each situation and details the steps to follow and the forms to complete to document such specimens when they are encountered. In each instance, the laboratory should keep the urine specimen, notify the appropriate personnel, and request collection of a new specimen. Unlabeled and improperly labeled urine specimens (e.g., name or ID number on container label and order slip do not match) are probably the two most common reasons for specimen rejection. Another reason for specimen rejection is a request for a urine culture when the urine specimen was collected in a nonsterile container, or when midstream clean catch instructions were not provided to the patient for collection.

Some institutions allow urine absorbed into a diaper or other absorbent material (e.g., cotton balls) to be used for chemical analysis; the urine is recovered by expressing it into a specimen cup. However, this urine is not acceptable for bacterial culture or for the physical and microscopic examination portions of a routine urinalysis because epithelial cells, blood cells, and formed elements (e.g., casts, mucus) will be trapped in the absorbent material causing erroneous results. Other causes for rejection include specimens that have not been properly stored and those visibly contaminated with fecal material or debris (e.g., toilet tissue).

Urine Volume Needed for Testing

Routine urinalysis protocols typically require 10 mL to 15 mL of urine, but collection of a larger volume is encouraged to ensure sufficient urine for additional or repeat testing. Smaller volumes of urine (< 12 mL) hinder performance of the microscopic examination when the urinalysis is performed manually and can limit the chemical tests performed. However, if a fully automated urinalysis system (see Chapter 16) is used, a complete urinalysis can be performed with 3 to 5 mL of urine.

With 24-hour urine collections, despite the large volume of urine submitted to the laboratory, only a small amount (≈1 mL) of well-mixed urine is actually required for quantitative urine tests (e.g., creatinine, hormones, electrolytes). A portion of the urine collection (20 to 50 mL) is usually retained to ensure sufficient specimen in case repeat or additional testing is required later.

Urine Specimen Storage and Handling

Containers

Containers for urine specimen collections must be clean, dry, and made of a clear or translucent disposable material such as plastic or glass. They should stand upright, have an opening of at least 4 to 5 cm, and have a capacity of 50 to 100 mL. A lid or cover that is easily placed onto and removed from the container is needed to prevent spillage. Specimens that are transported require a lid with a leakproof seal. Disposable, nonsterile containers are commercially available and economical.

For the collection of specimens for microbial culture, sterile, individually packaged urine containers are available from commercial sources. However, when a urine specimen must be stored for 2 hours or longer before testing, the use of a sterile container is recommended, regardless of the tests ordered, because of changes that can occur in unpreserved urine.

Various large containers are available for the collection of 12-hour and 24-hour urine specimens for quantitative analyses. These containers have a capacity of approximately 3000 mL and have a wide mouth and a leakproof screw cap. Usually made of a brown, opaque plastic, they protect the specimen from ultraviolet and white light, and acid preservatives can be added to them.

Clear, pliable, polyethylene urine collection bags are available for collecting specimens from the pediatric patient. These collection bags can be purchased as nonsterile or sterile. After collection, they are self-sealing for transport to the laboratory. For collection of a 24-hour specimen, some brands provide an exit port or tubing attached to the bag base. This port enables transfer of the urine that has accumulated to another collection container, thereby eliminating the need for multiple collection bags. More important, this exit port avoids repeated patient preparation and reapplication of adhesive to a child’s sensitive skin.

Labeling

All specimen containers must be labeled before or immediately after collection. Because lids are removed, the patient identification label is always placed directly on the container holding the specimen. Under no circumstances should the label appear only on the removable specimen lid. This practice invites specimen mix-ups; once the lid is removed, such a specimen is technically unlabeled.

Labels must have an adhesive that resists moisture and adheres under refrigeration. The patient identification information required on the label may differ among laboratories. However, the following minimal information should be provided on all labels: the patient’s full name, a unique identification number, the date and time of collection, the patient’s room number (if applicable), and the preservative used, if any.

Handling and Preservation

Changes in Unpreserved Urine

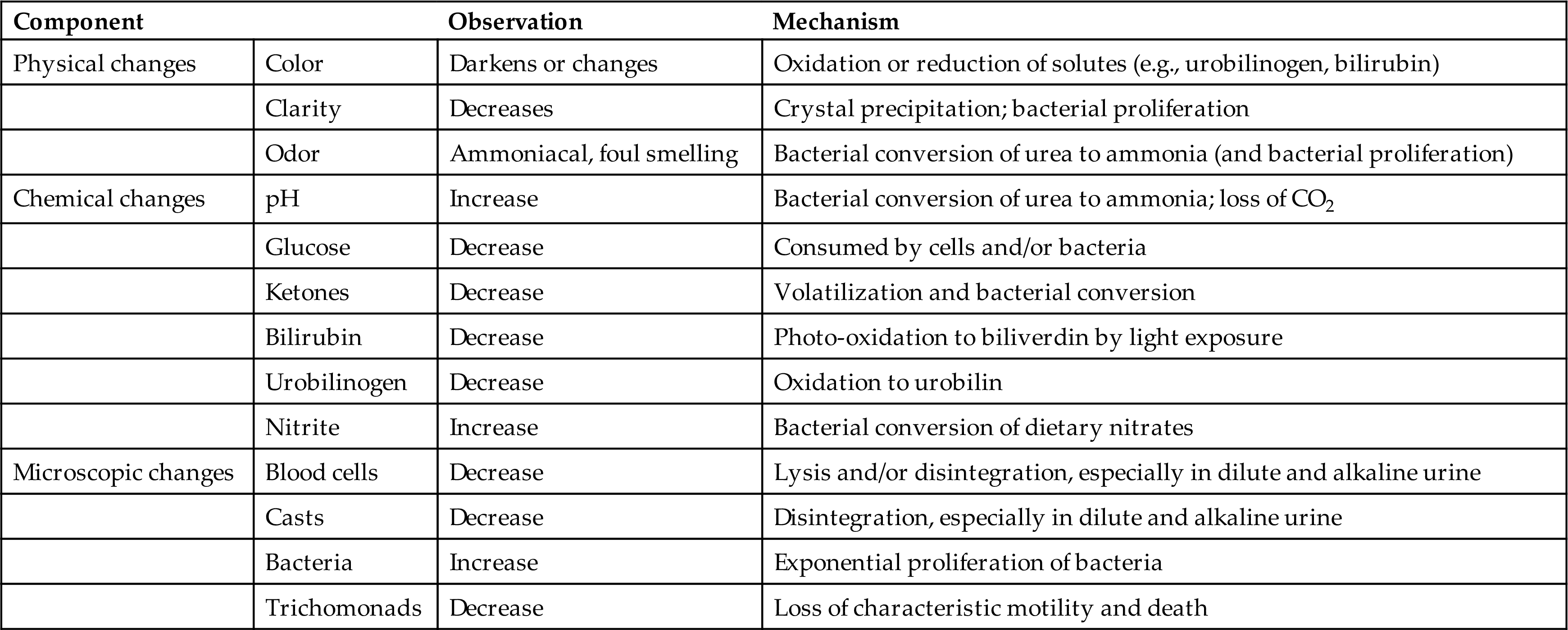

Urine specimens should be delivered to the laboratory immediately after collection. However, this is not always possible; if a delay in specimen transportation is to be 2 hours or longer, precautions must be taken to preserve the integrity of the specimen, protecting it from the effects of light and room temperature changes. A variety of changes can occur in unpreserved urine (Table 2.3). These changes can potentially affect any aspect—physical, chemical, or microscopic examinations—of a urinalysis. Changes in the physical examination result from (1) alteration of the urine solutes to a different form, resulting in a color change; (2) bacterial growth causing an increased odor because of metabolism or proliferation of bacteria; and (3) solute precipitation in the form of amorphous material, which decreases urine clarity. Individual components of the chemical examination (e.g., glucose, pH) can also be affected. Most often these changes result in removal of the chemical entity by various mechanisms, leading to false-negative results. In contrast, urine nitrite and pH increase in unpreserved urine as bacteria proliferate, converting nitrate to nitrite and metabolizing urea to ammonia.

Table 2.3

The microscopic changes that can occur result from disintegration of formed elements, particularly in hypotonic and alkaline urine, or from unchecked bacterial growth. In the latter case, it can be difficult to determine whether the large number of bacteria observed in these specimens results from improper storage or from a urinary tract infection.

In summary, changes will occur in unpreserved urine; which changes occur and their magnitude vary and are impossible to predict. Therefore appropriate specimen collection, handling, and storage are necessary to ensure that these potential changes do not occur and that accurate results are obtained.

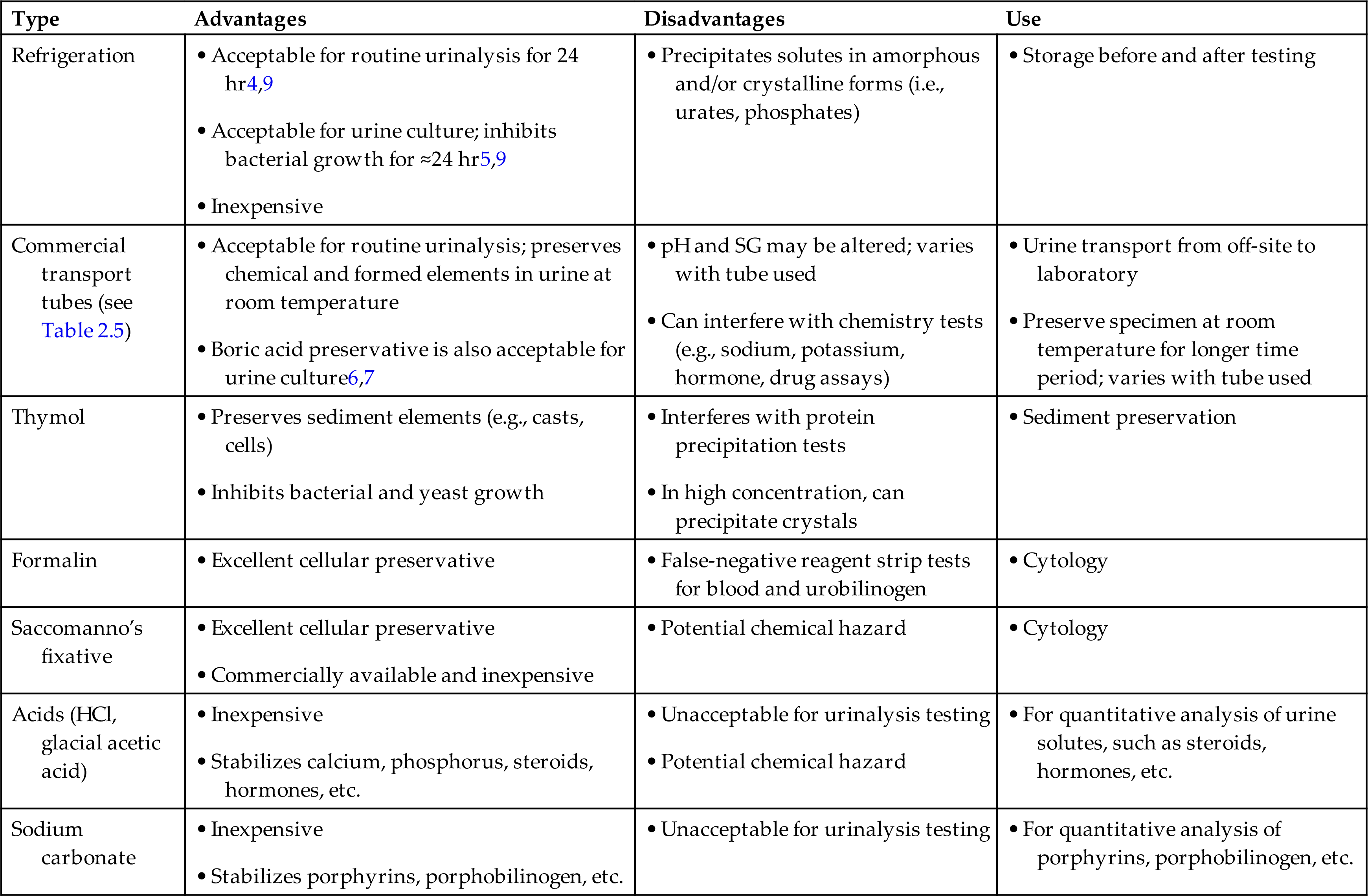

Preservatives

Unfortunately, no single urine preservative is available to suit all testing needs (Table 2.4). Hence the preservative used depends on the type of collection, the tests to be performed, and the time delay before testing. The easiest and most common form of preservation, refrigeration at 4°C to 6°C, is suitable for the majority of specimens.4,5 Any urine specimen for microbiological studies should be refrigerated promptly if it cannot be transported directly to the laboratory. Refrigeration prevents bacterial proliferation, and the specimen remains suitable for culture for up to 24 hours.

Table 2.4

| Type | Advantages | Disadvantages | Use |

|---|---|---|---|

| Refrigeration | |||

| Commercial transport tubes (see Table 2.5) | |||

| Thymol | |||

| Formalin | |||

| Saccomanno’s fixative | |||

| Acids (HCl, glacial acetic acid) | |||

| Sodium carbonate |

aTime frame of acceptability for urine specimens and the use of preservatives are determined by each laboratory.

Although refrigeration is the easiest means of preserving urine specimens, refrigeration of routine urinalysis specimens is not recommended if they will be analyzed within 2 hours.1 Refrigeration can induce precipitation of amorphous urate and phosphate crystals that can interfere substantially with the microscopic examination. For routine urinalysis specimens that must be transported long distances, commercial transport tubes with a preservative are available (Table 2.5).6–9

Table 2.5

Timed Collections

Timed specimens, particularly 12-hour and 24-hour collections, may require the addition of a chemical preservative to maintain the integrity of the analyte of interest. Regardless of the preservative necessary, urine collections should be kept on ice or refrigerated throughout the duration of the collection.

The collection preservative needed for a particular analyte can differ among laboratories. These variations stem from (1) different test methods; (2) how often the test is performed; and (3) time delays and transportation conditions (e.g., the sample is sent to a reference laboratory). Some laboratories may perform an assay daily in-house and require only refrigeration of the sample during the timed collection. In contrast, a small laboratory may send the assay to a reference facility that requires that a chemical preservative be used during the collection to ensure analyte stability. Each urinalysis laboratory must have in its procedure manual a protocol for the collection of all timed urine specimens. The protocol should include the name of the analyte; a description of the appropriate specimen collection technique; the appropriate preservative required; labeling requirements, including precautions for certain chemical preservatives; the location at which the test is performed; reference ranges; and the expected turnaround time.

Timed urine collections should be transported to the laboratory as soon as possible after completion of the collection. The total volume is determined, the specimen is well mixed to ensure homogeneity, and aliquots are removed for the appropriate tests. At no point during a timed collection can urine be removed or discarded, even if the volume is recorded. This would invalidate the collection because the concentration of the analyte in any removed aliquot cannot be determined and corrected for.

Is this Fluid Urine?

At times it is necessary to verify that the fluid present in a urine container is in fact urine. This may occur in laboratories that perform urine testing for illicit drugs (e.g., amphetamine, cocaine, tetrahydrocannabinol [THC], steroids). In these situations, particularly when the urine collection is not witnessed, the individual may have the opportunity to add a substance to the urine collection (e.g., an adulterated specimen). Another possibility is that the liquid in the container is not urine.

Specific gravity, pH, and temperature can be helpful in identifying urine specimens to which additional liquid has been added. The physiologically possible range for urine pH in a fresh urine specimen is 4.0 to 8.0 and for specific gravity is 1.002 to 1.035. In a normal healthy individual, the temperature of a urine specimen immediately after collection is usually between 32.5°C and 37.5°C. If this range is exceeded and the temperature is lower or higher, the urine has been altered in some way, or the fluid is not urine. Note that urine specific gravity can exceed 1.035 if the patient has had a recent infusion of radiographic contrast media (x-ray dye).

Occasionally, when an amniocentesis is performed, concern may be raised regarding whether the fluid collected is amniotic fluid or urine aspirated from the bladder. Another circumstance that may be encountered is receipt in the laboratory of two specimens from the same patient in identical sterile containers for testing, but the fluid source is not clearly evident on either container. In these varied situations, a few simple and easily performed tests can aid in determining whether the fluid is actually urine.

The single most useful substance that identifies a fluid as urine is its uniquely high creatinine concentration (approximately 50 times that of plasma). Similarly, concentrations of urea, sodium, and chloride are significantly higher in urine than in other body fluids. Note that in urine from healthy individuals, no protein or glucose is usually present. In contrast, other body fluids such as amniotic fluid or plasma exudates contain glucose and are high in protein.

Study Questions

- 1. Which of the following is the urine specimen of choice for cytology studies?

- 2. Which of the following specimens usually eliminates contamination of the urine with entities from the external genitalia and the distal urethra?

- 3. Substances that show diurnal variation in their urinary excretion pattern are best evaluated using a

- 4. Which of the following will not cause erroneous results in a 24-hour timed urine collection?

- 5. A 25-year-old woman complains of painful urination and is suspected of having a urinary tract infection. Which of the following specimens should be collected for a routine urinalysis and urine culture?

- 6. Which of the following tests requires a timed urine collection?

- 7. An unpreserved urine specimen collected at midnight is kept at room temperature until the morning hospital shift. Which of the following changes will most likely occur?

- 8. A urine specimen containing the substance indicated is kept unpreserved at room temperature for 4 hours. Identify the probable change to that substance.

- 9. Which of the following is the most common method used to preserve urine specimens?

- 10. If refrigeration is used to preserve a urine specimen, which of the following may occur?

- 11. Which of the following urine preservatives is acceptable for both urinalysis and urine culture?

- 12. How much urine is usually required for a ‘manually’ performed routine urinalysis?

- 13. Which of the following substances is higher in urine than in any other body fluid?