Routine Urinalysis—the Chemical Examination

After studying this chapter, the student should be able to:

- 1. State the proper care and storage of commercial reagent strip and tablet tests and cite at least three potential causes of their deterioration.

- 2. Describe quality control procedures for commercial reagent strip and tablet tests.

- 3. Discuss appropriate specimen and testing techniques used with commercial reagent strip and tablet tests.

- 4. State the chemical principle used on reagent strips for measurement of the following:

- 5. Summarize the clinical significance of the following substances when present in urine and describe the chemical principles used on reagent strips to measure them:

- 6. Compare and contrast the sensitivity, specificity, and potential interferences of each commercial reagent strip and tablet test.

- 7. Compare and contrast the mechanisms for and the clinical significance of the following types of proteinurias:

- 8. Discuss the clinical features of the nephrotic syndrome and Fanconi’s syndrome, including the specific renal dysfunctions involved.

- 9. Compare and contrast the chemical principle, sensitivity, and specificity of the following tests for the detection of proteins in the urine:

- 10. Differentiate between hematuria and hemoglobinuria.

- 11. Discuss the clinical significance of myoglobin. Compare and contrast myoglobinuria and hemoglobinuria.

- 12. Discuss the limitations of leukocyte esterase and nitrite reagent strip tests for the detection of leukocyturia and bacteriuria.

- 13. Describe two physiologic mechanisms that result in glucosuria.

- 14. Compare and contrast the glucose reagent strip test and the copper reduction test for the measurements of sugars in urine.

- 15. Describe three conditions that result in ketonuria.

- 16. Briefly explain the metabolic pathway that results in ketone formation, state the relative concentrations of the three ketones formed, and discuss the reagent strip and tablet tests used to detect them.

- 17. Summarize the formation of bilirubin and urobilinogen, discuss their clinical significance, and describe three physiologic mechanisms that result in altered bilirubin metabolism.

- 18. Describe two chemical principles used by reagent strip tests to detect urine urobilinogen and compare their sensitivity, specificity, and limitations.

- 19. Compare and contrast the principle, sensitivity, specificity, and limitations of the following methods for detection of bilirubin in urine:

- 20. State the importance of ascorbic acid detection in urine, and describe methods used to detect ascorbic acid.

- 21. Identify reagent strip tests that are affected adversely by ascorbic acid, and explain the mechanism of interference.

- 22. Describe the role of reflex testing in urinalysis and discuss the correlation between results obtained in the chemical examination and what they imply for the microscopic examination.

Key Terms1

- albuminuria

- ascorbic acid (also called vitamin C)

- ascorbic acid interference

- bacteriuria

- bilirubin

- Ehrlich’s reaction

- Fanconi’s syndrome

- glomerular proteinuria

- glucosuria; glycosuria

- hematuria; heme moiety

- hemoglobinuria

- hemosiderin

- jaundice

- ketonuria

- leukocyturia

- myoglobinuria

- nephrotic syndrome

- overflow proteinuria

- postrenal proteinuria

- postural (orthostatic) proteinuria

- protein error of indicators

- proteinuria

- pseudoperoxidase activity

- pyuria

- reflex testing

- renal proteinuria

- tubular proteinuria

- urinary tract infection (UTI)

- urobilinogen

Reagent Strips

Commercial reagent strips are routinely used for chemical analysis of urine. Reagent strips enable rapid screening of urine specimens for pH, protein, glucose, ketones, blood, bilirubin, urobilinogen, nitrite, and leukocyte esterase. In addition, specific gravity and ascorbic acid can be determined by reagent strip, depending on the brand of strip used. Four commonly used brands of commercial reagent strips are Multistix (Siemens Healthcare Diagnostics Inc., Deerfield, IL), Chemstrips (Roche Diagnostics, Indianapolis, IN), and Aution Sticks (Arkray Inc., Kyoto, Japan). Most commercial reagent strips are available with single or multiple test pads on a reagent strip, which allows flexibility in test selection and cost containment.

A reagent strip is an inert plastic strip onto which reagent-impregnated test pads are bonded (Fig. 6.1). Chemical reactions take place after the strip is wetted with urine. Each reaction results in a color change that can be assessed visually or mechanically. By comparing the color change observed with the color chart supplied by the strip manufacturer, qualitative results for each reaction are determined. See Appendix A for samples of these color charts and the reporting formats provided by manufacturers on reagent strip containers. Depending on the test, results are reported (1) in concentration (milligrams per deciliter); (2) as small, moderate, or large; (3) using the plus system (1+, 2+, 3+, 4+); or (4) as positive, negative, or normal. The specific gravity and the pH are exceptions; these results are estimated in their respective units. Manufacturers do not use the same reporting terminology. For example, Multistix strips report glucose values less than 100 mg/dL as negative, whereas Chemstrips report these glucose results as normal. These minor inconsistencies among products can be confusing. Therefore, laboratorians must be aware of the reporting format, the chemical principles involved, and the specificity and sensitivity of each test included on the reagent strips used in their laboratory.

The chemical principles used on reagent strips are basically the same, with some manufacturers differing only in the determination of urobilinogen. See Appendix B for a tabular summary and comparison of reagent strip reaction principles, sensitivity, and specificity, which are also discussed throughout this chapter.

Reagent strips are available with a single test pad (e.g., Albustix, a single-protein test pad) or with a variety of test pad combinations. These combinations vary from 2 to 10 testpads per reagent strip and enable health-care providers to selectively screen urine specimens for only those constituents that interest them (e.g., Chemstrip 2 LN and Multistix 2 have only two pads: leukocyte esterase and nitrite tests). Some manufacturers also include a pad to account for urine color when automated reagent strip readers (i.e., reflectance photometers) are used.

Because reducing agents such as ascorbic acid have the potential to adversely affect several reagent strip test results, it is important that these and other potential interferences are detected or eliminated. In this regard, Chemstrip reagent strips use an iodate overlay on the blood test pad to eliminate ascorbic acid interference. The presence of interferences must be known to enable alternative testing when possible or to appropriately modify the results to be reported. Common interferences encountered in the chemical examination of urine and the effects these interferences have on urinalysis results are discussed for each reagent strip test in this chapter.

Care and Storage

Reagent strips, which are sometimes called dipsticks, are examples of state-of-the-art technology. Before the development of the first dry chemical dipstick test for glucose in the 1950s, all chemical tests on urine were performed individually in test tubes. Reagent strips have significantly (1) reduced the time required for testing, (2) reduced costs (e.g., reagents, personnel), (3) enhanced test sensitivity and specificity, and (4) decreased the amount of urine required for testing.

To ensure the integrity of reagent strips, their proper storage is essential, and the manufacturer’s directions must be followed. Each manufacturer provides a comprehensive product insert that outlines the chemical principles, reagents, storage, use, sensitivity, specificity, and limitations of its reagent strips. All reagent strips must be protected from moisture, chemicals, heat, and light. Any strips showing evidence of deterioration, contamination, or improper storage should be discarded. Tight-fitting lids, along with desiccants or drying agents within the product container, help eliminate test pad deterioration due to moisture. Fumes from volatile chemicals, acids, and bases can adversely affect the test pads and should be avoided. All reagent strip containers protect the reagent strips from ultraviolet rays and sunlight; however, the containers themselves must be protected to prevent fading of the color chart located on the label of the container. Reagent strips should be stored in their original containers at temperatures below 30°C (86°F); they are stable until the expiration date indicated on the label. To ensure accurate test results, all reagent strips—whether from a newly opened container or from one that has been opened for several months—must be periodically tested using appropriate control materials.

Quality Control Testing

Quality control testing of reagent strips not only ensures that the reagent strips are functioning properly, but also confirms the acceptable performance and technique of the laboratorian using them. Multiconstituent controls at two distinct levels (e.g., negative and positive) for each reaction must be used to check the reactivity of reagent strips. New containers or lot numbers of reagent strips must be checked “at a frequency defined by the laboratory, related to workload, suggested by the manufacturer, and in conformity with any applicable regulations.”1

Commercial or laboratory-prepared materials can serve as acceptable negative controls. Similarly, positive controls can be purchased commercially or prepared by the laboratory. Because of the time and care involved in making a multiconstituent control material that tests each parameter on the reagent strip, most laboratories purchase control materials. When control materials are tested, acceptable test performance is defined by each laboratory. Regardless of the control material used, care must be taken to enwsure that analyte values are within the critical detection levels for each parameter. For example, a protein concentration of 1 g/dL would be inappropriate as a control material because it far exceeds the desired critical detection level of 10 to 15 mg/dL.

An additional quality check on chemical and microscopic examinations, as well as on the laboratorian, involves aliquoting a well-mixed urine specimen from the daily workload and having a different laboratory (interlaboratory) or a technologist on each shift (intralaboratory) analyze the specimen. Interlaboratory duplicate testing checks the entire urinalysis procedure and detects innocuous changes when manual urinalyses are performed, such as variations in the speed of centrifugation and in centrifuge brake usage. Intralaboratory duplicate testing can also be used to evaluate the technical competency of laboratorians.

Tablet and Chemical Tests

Care and Storage

Commercial tablet tests (e.g., Ictotest, Clinitest, Acetest [all from Siemens Healthcare Diagnostics Inc.]) must be handled and stored according to the inserts provided by the manufacturers. These products are susceptible to deterioration from exposure to light, heat, and moisture. Therefore they should be visually inspected before each use and discarded if any of the following changes have occurred: tablet discolored, contamination or spoilage evident, incorrect storage, or past the expiration date. Note that the stability of the reaction tablets can decrease after opening because of repeated exposure to atmospheric moisture. To ensure tablet integrity, an appropriate quality control program must be employed.

Chemical tests such as the sulfosalicylic acid (SSA) precipitation test, the Hoesch test, and the Watson-Schwartz test require appropriately made and tested reagents. When new reagents are prepared, they should be tested in parallel with current “in-use” reagents to ensure equivalent performance. Chemical tests must also be checked according to the laboratory’s quality control program to ensure the reliability and reproducibility of test results obtained.

Quality Control Testing

As with reagent strips, tablet or chemical tests performed in the urinalysis laboratory must have quality control materials run to ensure the integrity of the reagents and the technique used in testing. Some commercial controls for reagent strips can also be used to check the integrity of Clinitest, Ictotest, and Acetest tablets. In addition, lyophilized chemistry controls or laboratory-made control materials can be used. For example, a chemistry albumin standard at an appropriate concentration (approximately 30 to 100 mg/dL) serves as a satisfactory control for performance of the SSA protein precipitation test.

Positive and negative quality control materials must be analyzed according to the frequency established in the laboratory’s policy. New tablets and reagents should be checked before they are placed into use and periodically thereafter.

Chemical Testing Technique

Reagent Strips

Although reagent strips are easy to use, proper technique is imperative to ensure accurate results. Box 6.1 summarizes an appropriate manual reagent strip testing technique. The manufacturer’s instructions provided with the reagent strips and tablet tests must be followed to obtain accurate results. Note that instructions vary among different manufacturers and that failure to read reaction results at the correct time could cause the reporting of erroneous results. For example, the reactions on Multistix strips must be read at the specific time indicated, which varies from 30 seconds to 2 minutes. In contrast, all reactions on Chemstrip brand strips are stabilized and can be read at 2 minutes.

A fresh, well-mixed, uncentrifuged specimen is used for testing. If the specimen is maintained at room temperature, it must be tested within 2 hours after collection to avoid erroneous results caused by changes that can occur in unpreserved urine1 (see Chapter 2, Table 2.3). If the urine specimen has been refrigerated, it should be allowed to warm up to room temperature before testing with reagent strips to avoid erroneous results. The specimen can be tested in the original collection container or after an aliquot is poured into a labeled centrifuge tube. The reagent strip should be briefly dipped into the urine specimen, wetting all test pads. Excess urine should be drained from the strip by drawing the edge of the strip along the rim of the container or by placing the strip edge on an absorbent paper. Inadequate removal of excess urine from the strip can cause contamination of one test pad with the reagents from another, whereas prolonged dipping of the strip causes the chemicals to leach from the test pad into the urine. Both of these actions can produce erroneous test results.

When reagent strips are read, the time required before full color development varies with the test parameter. To obtain reproducible and reliable results, the timing instructions provided by the manufacturer must be followed. Timing intervals can differ among reagent strips from the same manufacturer and among different manufacturers of the same test. For example, when a Multistix strip is used, the ketone test pad is read at 40 seconds; however, when Ketostix strips are used, the test area is read at 15 seconds. Some reagent strips have the flexibility of reading all test pads, except leukocytes, at any time between 60 and 120 seconds (e.g., Chemstrips), whereas others require the exact timing of each test pad for semiquantitated results (e.g., Multistix strips).

Visual interpretation of color varies slightly among individuals; therefore reagent strips should be read in a well-lit area with the strip held close to the color chart. The strip must be properly oriented to the chart before results are determined. Because of similar color changes by several of the test pads, improper orientation of the strip to the color chart is a potential source of error. (See Appendix A, Reagent Strip Color Charts.) Note that color changes appearing only along the edge of a reaction pad or after 2 minutes are diagnostically insignificant and should be disregarded. When reagent strips are read by automated instruments, the timing intervals are set by the factory. The advantage of automated instruments in reading reagent strips is their consistency in timing and color interpretation regardless of room lighting or testing personnel. Some instruments, however, are unable to identify and compensate for urine that is highly pigmented owing to medications. This can lead to false-positive reagent strip test results because the true color reaction is masked by the pigment present. Laboratorians should identify highly pigmented urine specimens and manually test them using reagent strips or alternative methods. The sensitivity and specificity of three brands of commercial reagent strips are discussed throughout this chapter and are summarized in tabular form in Appendix B.

Tablet and Chemical Tests

With each tablet test, the manufacturer’s directions must be followed exactly to ensure reproducible and reliable results. All chemical tests, such as the SSA precipitation test for protein, must be performed according to established written laboratory procedures. The laboratorian should know the sensitivity, specificity, and potential interferences for each test. Chemical and tablet tests are generally performed (1) to confirm results already obtained by reagent strip testing, (2) as an alternative method for highly pigmented urine, (3) because they are more sensitive for the substance of interest than the reagent strip test (e.g., Ictotest tablets), or (4) because the specificity of the test differs from that of the reagent strip test (e.g., Clinitest, SSA protein test).

Chemical Tests

Specific Gravity

Despite being a physical characteristic of urine, specific gravity is often determined during the chemical examination using commercial reagent strips. Provided in Table 6.1 is a listing of specific gravity values and associated conditions. For in-depth discussion of the clinical significance and renal tubular functions reflected by specific gravity as well as osmolality measurements, see Chapter 4, subsections Specific Gravity and Assessment of Renal Concentrating Ability.

Table 6.1

ADH, Antidiuretic hormone, also known as arginine vasopressin (AVP).

Methods available for measuring specific gravity differ in their ability to detect and measure solutes. Therefore it is important that health-care providers are informed of the test method used—its principle, sensitivity, specificity, and limitations. See Chapter 5 and Table 5.6 for a detailed discussion and comparison of the specific gravity methods: refractometry and reagent strip method.

Principle

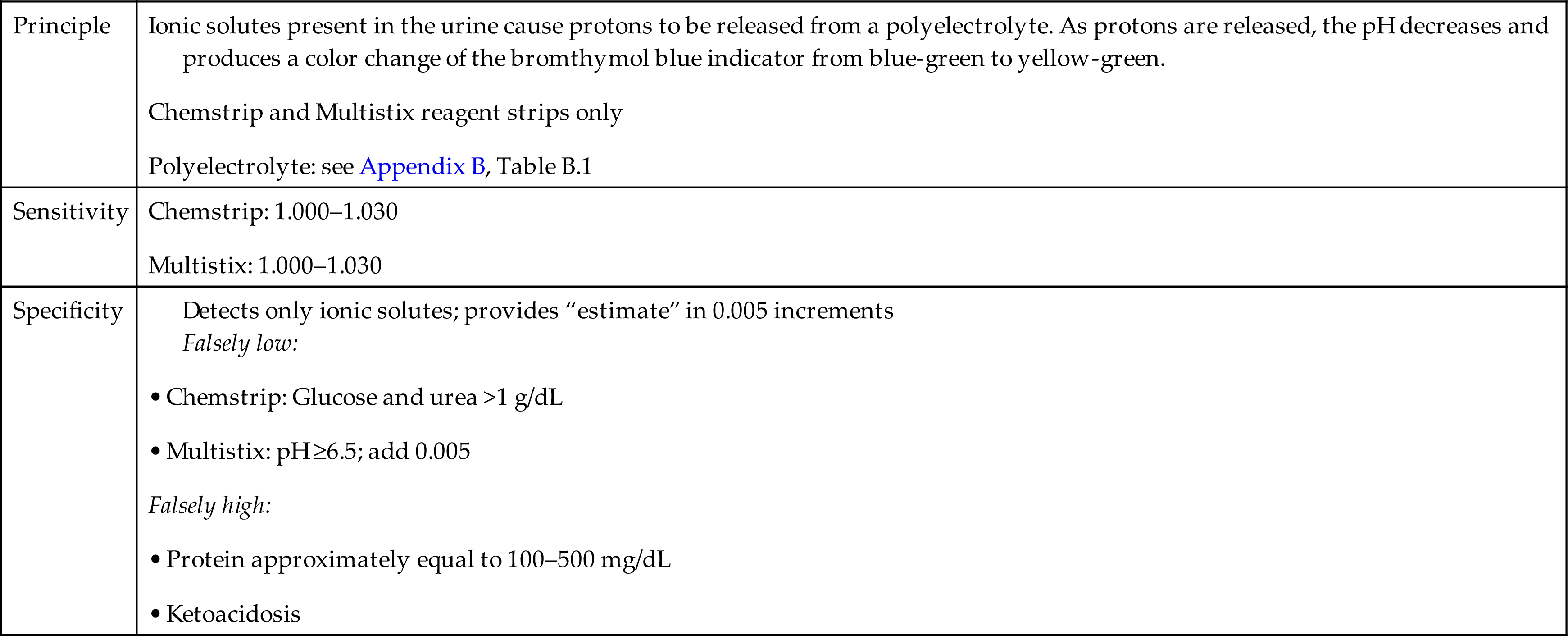

The reagent strip specific gravity test does not measure the total solute content but only those solutes that are ionic. Keep in mind that only ionic solutes are involved in the renal concentrating and secreting ability of the kidneys and therefore this test has diagnostic value (see Chapter 4). Table 6.2 provides a summary of the specific gravity reaction principle, sensitivity, and specificity using selected reagent strip brands.

Table 6.2

| Principle | Ionic solutes present in the urine cause protons to be released from a polyelectrolyte. As protons are released, the pH decreases and produces a color change of the bromthymol blue indicator from blue-green to yellow-green. Chemstrip and Multistix reagent strips only Polyelectrolyte: see Appendix B, Table B.1 |

| Sensitivity | |

| Specificity | Detects only ionic solutes; provides “estimate” in 0.005 increments • Chemstrip: Glucose and urea >1 g/dL • Multistix: pH ≥6.5; add 0.005 |

pH

Clinical Significance

The kidneys play a major role in regulating the acid–base balance of the body, as discussed in Chapter 3. The renal system, the pulmonary system, and blood buffers provide the means for maintaining homeostasis at a pH compatible with life. Normal daily metabolism generates endogenous acids and bases; in response, the kidneys selectively excrete acid or alkali. Normally, the urine pH varies from 4.5 to 8.0. The average individual excretes slightly acidic urine of pH 5.0 to 6.0 because endogenous acid production predominates. However, during and after a meal the urine produced is less acidic. This observation is known as the alkaline tide.

Urine pH can affect the stability of formed elements in urine. An alkaline pH enhances lysis of cells and degradation of the matrix of casts. Because pH values greater than 8.0 and less than 4.5 are physiologically impossible, they require investigation when obtained. The three most common reasons for a urine pH greater than 8.0 are (1) a urine specimen that was improperly preserved and stored, resulting in the proliferation of urease-producing bacteria and resultant increased pH; (2) an adulterated specimen (i.e., an alkaline agent was added to the urine after collection); and (3) the patient was given a highly alkaline substance (e.g., medication, therapeutic agent) that was subsequently excreted by the kidneys. In the latter situation, efforts should be made to ensure adequate hydration of the patient to prevent in vivo precipitation of normal urine solutes (e.g., ammonium biurate crystals), which can cause renal tubular damage.

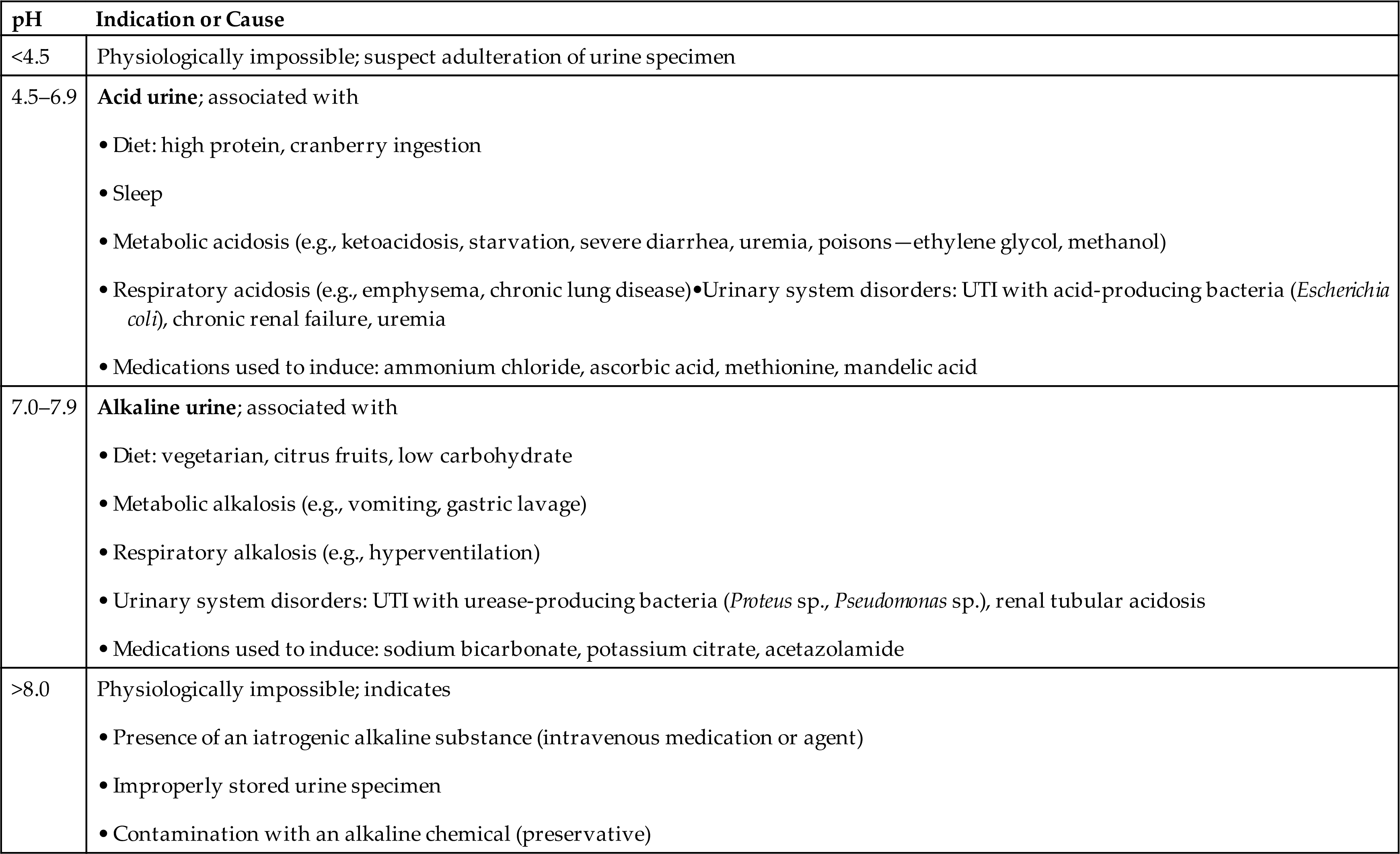

Because the kidneys constantly maintain the acid–base balance of the body, ingestion of acids or alkali or any condition that produces acids or alkali directly affects the urine pH. Table 6.3 lists urine pH values and common causes associated with them. This ability of the kidneys to manipulate urine pH has many applications. An acid urine prevents stone formation by alkaline-precipitating solutes (e.g., calcium carbonate, calcium phosphate) and inhibits the development of UTI. An alkaline urine prevents the precipitation of and enhances the excretion of various drugs (e.g., sulfonamides, streptomycin, salicylate) and prevents stone formation from calcium oxalate, uric acid, and cystine crystals.

Table 6.3

The urine pH provides valuable information for assessing and managing disease and for determining the suitability of a specimen for chemical testing. Correlation of urine pH with a patient’s condition aids in the diagnosis of disease (e.g., production of an alkaline urine despite a metabolic acidosis is characteristic of renal tubular acidosis). Individuals with a history of stone formation can monitor their urine pH and use this information to modify their diets if necessary. Highly alkaline urine of pH 8.0 to 9.0 can also interfere with chemical testing, particularly in protein determination.

Methods

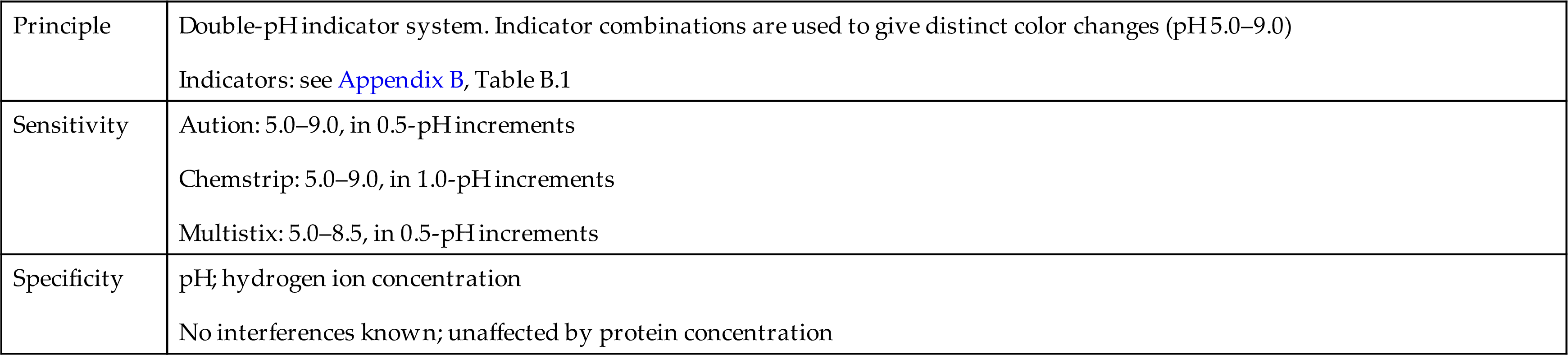

Reagent strip tests

Commercial reagent strips, regardless of the manufacturer, are based on a double indicator system that produces varying color changes with pH (Equation 6.1). The indicator combinations produce color changes from yellow or orange (pH 5.0) to green (pH 7.0) to blue (pH 9.0). See Appendix B, Table B.1 for specific indicators used by different manufacturers.

Equation 6.1

Equation 6.1

The range provided on the strips is from pH 5.0 to pH 9.0 in 0.5- or 1.0-pH increments, depending on the manufacturer. No interferences with test results are known, and the results are not affected by protein concentration. However, erroneous results can occur from pH changes caused by (1) improper storage of the specimen with bacterial proliferation (a falsely increased pH); (2) contamination of the specimen container before collection (a falsely increased or decreased pH depending on the agent); or (3) improper reagent strip technique, causing the acid buffer from the protein test pad to contaminate the pH test area (a falsely decreased pH). See Table 6.4 for a summary of the pH principle, sensitivity, and specificity on selected reagent strip brands.

Table 6.4

| Principle | Double-pH indicator system. Indicator combinations are used to give distinct color changes (pH 5.0–9.0) Indicators: see Appendix B, Table B.1 |

| Sensitivity | |

| Specificity |

pH meter

Although the accuracy provided by a pH meter is not usually necessary, a pH meter is an alternative method for determining the urine pH. Various pH meters are available; the manufacturer’s operating instructions supplied with the instrument must be followed to ensure proper use of the pH meter and valid results. Nevertheless, the components involved in and the principle behind all pH meters are basically the same.

A pH meter consists of a silver–silver chloride indicator electrode with a pH-sensitive glass membrane connected by a salt bridge to a reference electrode (usually a calomel electrode, Hg–Hg2Cl2). When the indicator electrode is placed in urine, a difference in H+ activity develops across the glass membrane. This difference causes a change in the potential difference between the indicator and the reference electrodes. This voltage difference is registered by a voltmeter and is converted to a pH reading. Because pH measurement is temperature dependent and pH decreases with increasing temperature, it is necessary that the pH measurement be adjusted for the temperature of the urine during measurement. Most pH meters perform this temperature compensation automatically.

A pH meter is calibrated with the use of two or three commercially available standard buffer solutions. Accurate pH measurements require that the pH meter be calibrated using at least two different standards in the pH range of the test solution and that adjustment for the temperature of the test solution be made manually or automatically. In addition, the pH-sensitive glass electrode must be clean and maintained to prevent protein buildup or bacterial growth.

pH test papers

Various indicator papers with different pH ranges and sensitivities are commercially available. The indicator papers do not add impurities to the urine. In use, they produce sharp color changes for comparison with a supplied color chart of pH values.

Protein

Clinical Significance

Normal urine contains up to 150 mg (1 to 14 mg/dL) of protein each day. This protein originates from the ultrafiltration of plasma and from the urinary tract itself. Proteins of low molecular weight ([MW] <40,000) readily pass through the glomerular filtration barriers and are reabsorbed. Because of their low plasma concentration, only small quantities of these proteins appear in the urine. In contrast, albumin, a moderate-molecular-weight protein, has a high plasma concentration. This fact, combined with its ability (although limited) to pass through the filtration barriers, accounts for the small amount of albumin present in normal urine. Actually, less than 0.1% of plasma albumin enters the ultrafiltrate, and 95% to 99% of all filtered protein is reabsorbed. High-molecular-weight proteins (>90,000) are unable to penetrate a healthy glomerular filtration barrier. The end result is that the proteins in normal urine consist of about one-third albumin and two-thirds globulins. Among proteins that originate from the urinary tract itself, three are of particular interest: (1) uromodulin (also known as Tamm-Horsfall protein), which is a mucoprotein synthesized by the distal tubular cells and involved in cast formation; (2) urokinase, which is a fibrinolytic enzyme secreted by tubular cells; and (3) secretory immunoglobulin A,which is synthesized by renal tubular epithelial cells.2

The presence of an increased amount of protein in urine, termed proteinuria, is often the first indicator of renal disease. For most patients with proteinuria (prerenal and renal), the protein present at an increased concentration is albumin, although to varying degrees. Protein reabsorption by the renal tubules is a nonselective, competitive, and threshold-limited (Tm) process. Basically, when an increased amount of protein is presented to the tubules for reabsorption, the tubules randomly reabsorb the protein in a rate-limited process. As the quantities of proteins other than albumin increase and compete for tubular reabsorption, the amount of albumin excreted in the urine also increases. Proteinuria results from (1) an increase in the quantity of plasma proteins that are filtered, or (2) filtering of the normal quantity of proteins but with a reduction in the reabsorptive ability of the renal tubules. Early detection of proteinuria (i.e., albumin) aids in identification, treatment, and prevention of renal disease. However, protein excretion is not an exclusive feature of renal disorders, and other conditions can also present with proteinuria.

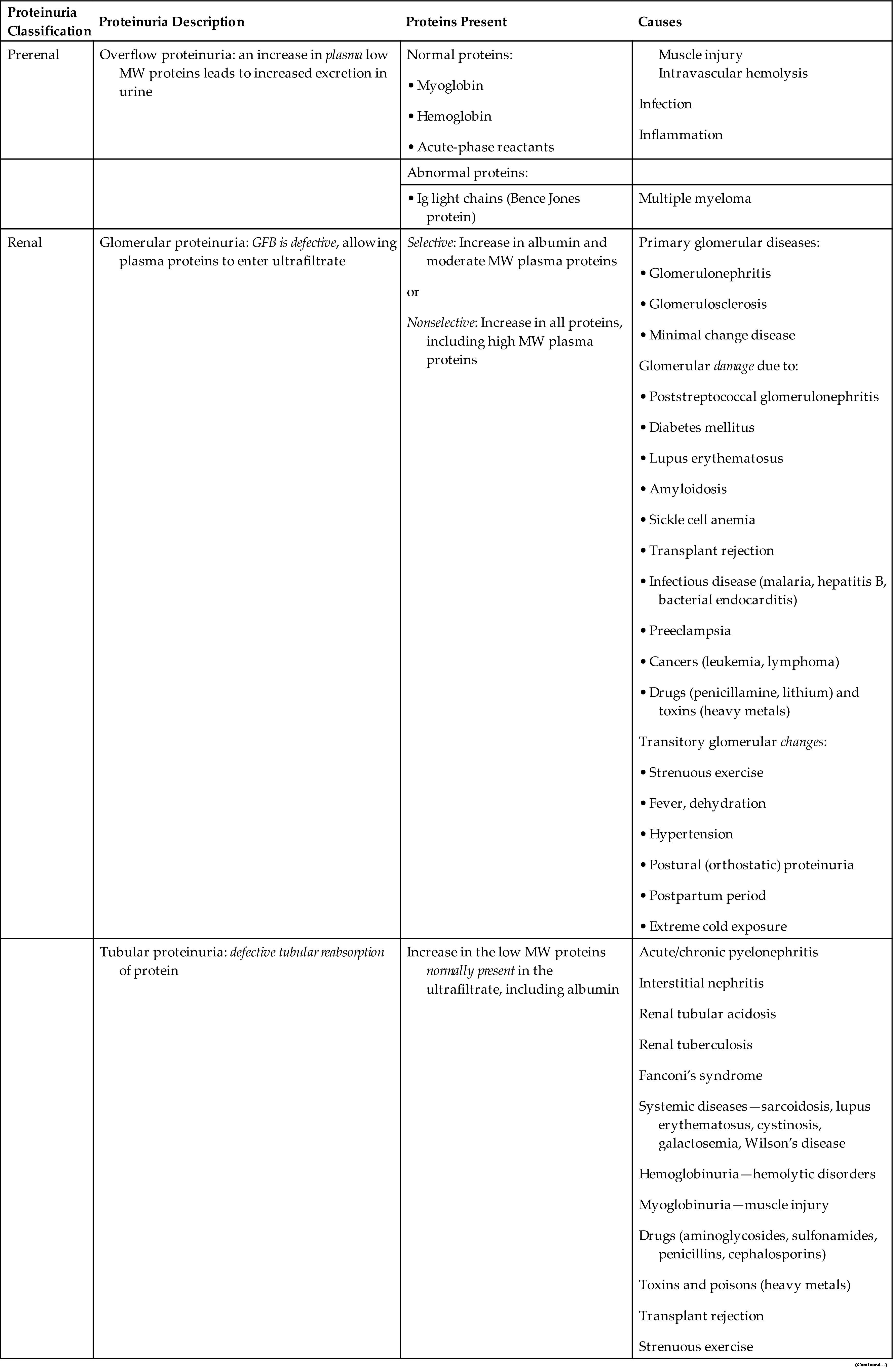

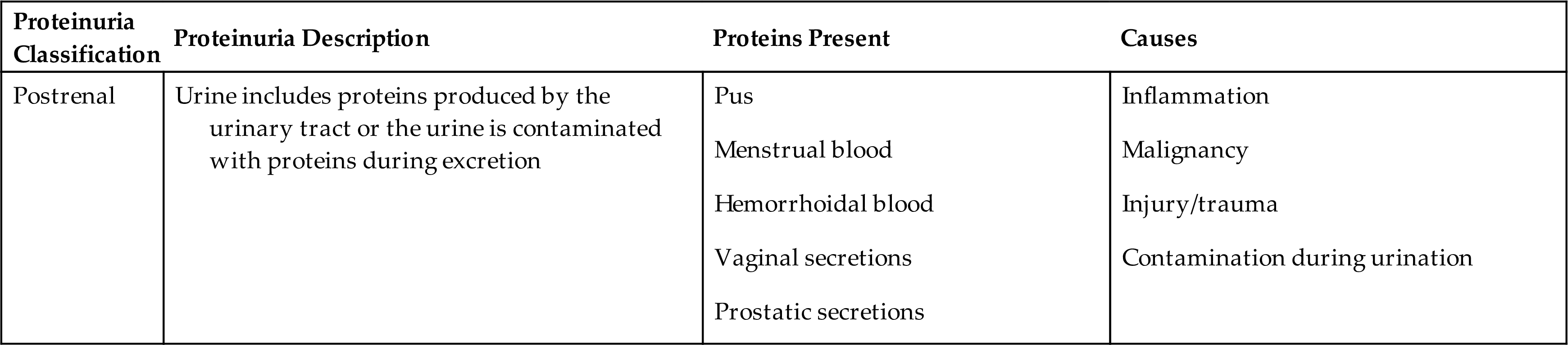

Proteinuria can be classified into four categories: prerenal or overflow proteinuria, glomerular proteinuria, tubular proteinuria, and postrenal proteinuria. This differentiation is based on a combination of protein origination and renal dysfunction; together, they determine the types and sizes of proteins observed in the urine (Table 6.5).

Table 6.5

GFB, Glomerular filtration barrier; Ig, immunoglobulin; MW, molecular weight.

Overflow proteinuria results from increased quantities of plasma proteins in the blood readily passing through the glomerular filtration barriers into the urine. As soon as the level of plasma proteins returns to normal, the proteinuria resolves. Conditions that result in this increased urine excretion of low-molecular-weight plasma proteins include septicemia, with spilling of acute-phase reactant proteins; hemoglobinuria, after a hemolytic episode; and myoglobinuria, which follows muscle injury. Immunoglobulin paraproteins (κ and λ monoclonal light chains) are also low-molecular-weight proteins that are abnormally produced in multiple myeloma and macroglobulinemia. These light chain diseases account for approximately 12% of monoclonal gammopathies. Historically, the presence of immunoglobulin light chains, also known as Bence Jones proteins, was identified in urine by their unique solubility as related to temperature. An aliquot of the urine specimen would be heated, and if the urine coagulated at 40°C to 60°C and redissolved at 100°C, this indicated the presence of immunoglobulin light chains, that is, Bence Jones protein. Today, immunoassays and electrophoretic techniques are available to specifically identify and quantitate these light chain proteins.

Renal proteinuria can present with a glomerular pattern, a tubular pattern, or a mixed pattern. Disease can cause changes to glomerular filtration barriers such that increased quantities of plasma proteins are allowed to pass with the ultrafiltrate. In glomerular proteinuria, the tubular capacity for protein reabsorption (Tm) is exceeded, and an increased amount of protein is excreted in the urine. As stated in Chapter 3, albumin would readily pass through the glomerular filtration barriers if not for its negative charge, which allows only a small amount of albumin to pass. Consequently, any disorder that alters the negativity of glomerular filtration barriers will (1) enable an increased amount of albumin to freely pass, and (2) allow other moderate-molecular-weight proteins of similar charge to pass, such as α1-antitrypsin, α1-acid glycoprotein, and transferrin (Box 6.2). The glomeruli are considered to be selective if they are able to retard the passage of high-molecular-weight proteins (>90,000) and nonselective if discrimination is lost and high-molecular-weight proteins are allowed into the ultrafiltrate.

Glomerular proteinuria occurs in primary glomerular diseases or disorders that cause glomerular damage. It is the most common type of proteinuria encountered and is the most serious clinically. The proteinuria is usually heavy, exceeding 2.5 g/day of total protein, and can be as much as 20 g/day. Some of the conditions that can result in glomerular proteinuria are listed in Table 6.5. Glomerular proteinuria can develop into a clinical condition termed nephrotic syndrome. This syndrome is characterized by proteinuria exceeding approximately 3.5 g/day, hypoalbuminemia, hyperlipidemia, lipiduria, and generalized edema. Nephrotic syndrome is a complication of numerous disorders and is discussed more fully in Chapter 8.

The detection of what seem to be minor increases in urine albumin excretion has particular merit in patients with diabetes, hypertension, or peripheral vascular disease. Although the exact mechanism of proteinuria is not clearly understood in each of these disorders, increased glomerular permeability appears to result from changes in glomerular filtration barriers. With diabetic individuals, the most important factor associated with the development of glomerular proteinuria is hyperglycemia. Because glucose is capable of nonenzymatic binding with various proteins, it apparently combines with proteins of the glomerular filtration barriers, causing glomerular permeability changes and stimulating growth of the mesangial matrix. In health, urine albumin excretion is less than 30 mg/day; when glomerular changes occur in a diabetic individual, urine albumin excretion increases to 30 to 300 mg/day. Because rigorous treatment in the early stages of disease can reverse these changes, chemical methods for the detection of low levels of albumin play an important role. See “Sensitive Albumin Tests” later in this chapter, Table 6.8, and Chapter 4, subsection Screening for Albuminuria.

Several conditions, termed functional proteinurias, induce a mild glomerular or mixed pattern of proteinuria in the absence of renal disease. Changes in glomerular blood flow (e.g., renal vasoconstriction) and enhanced glomerular permeability appear to be the primary mechanisms involved. Strenuous exercise, fever, extreme cold exposure, emotional distress, congestive heart failure, and dehydration are associated with this type of proteinuria. The amount of protein excreted is usually less than 1 g/day. Functional proteinurias are transitory and resolve with time and supportive treatment.

Postural (orthostatic) proteinuria is considered to be a functional proteinuria. This condition is characterized by the urinary excretion of protein only when the individual is in an upright (orthostatic) position. A first morning urine specimen is normal in protein content, whereas specimens collected during the day contain elevated quantities of protein. It is theorized that when the patient is in the upright position, increased renal venous pressure causes renal congestion and glomerular changes. Although this condition is considered to be benign, persistent proteinuria may develop, and evidence of glomerular abnormalities has been found by renal biopsy in a few patients.3 Urine protein excretion in postural proteinuria is usually less than 1.5 g/day. Individuals suspected of having postural proteinuria collect two urine specimens: a first morning specimen and a second specimen collected after the patient has been in an upright position for several hours. If the first specimen is negative for protein and the second is positive, a tentative diagnosis of postural proteinuria can be made. These individuals should be monitored every 6 months and reevaluated as necessary.

Proteinuria that occurs during pregnancy is usually transient and sometimes is associated with delivery, toxemia, or renal infection. A wide range in the amount of protein excreted has been noted. Protein excretion associated with preeclamptic toxemia approaches 3 g/day, whereas minor increases up to 300 mg/day occur with normal pregnancy.

Tubular proteinuria occurs when normal tubular reabsorptive function is altered or impaired. When either occurs, plasma proteins that normally are reabsorbed—such as β2-microglobulin, retinol-binding protein, α2-microglobulin, or lysozyme—will be increased in the urine. The urine total protein concentration is usually less than 2.5 g/day, with low-molecular-weight proteins predominating (Box 6.3). Although albumin is found in increased amounts, it does not approach the level found in glomerular proteinuria. In light of this, chemical testing methods that detect predominantly albumin (e.g., reagent strip tests) are limited in their ability to detect increased urine protein.

When tubular proteinuria is suspected, a quantitative urine total protein method should be employed, or a protein precipitation method sensitive to all proteins can be used for screening (e.g., SSA precipitation test). Tubular proteinuria, originally discovered in workers exposed to cadmium dust (a heavy metal), can result from a variety of disorders (see Table 6.5).It can occur alone or with glomerular proteinuria, as in chronic renal disease or renal failure, in which case the urine proteins excreted result in a mixed pattern.

A condition particularly characterized by proximal tubular dysfunction is Fanconi’s syndrome. This syndrome has the following distinctive urine findings: aminoaciduria, proteinuria, glycosuria, and phosphaturia. Associated with inherited and acquired diseases, this syndrome of altered tubular transport mechanisms retains normal glomerular function. Heavy metal poisoning and the hereditary disease cystinosis are common causes of Fanconi’s syndrome.

Postrenal proteinuria can result from an inflammatory process anywhere in the urinary tract—in the renal pelvis, ureters, bladder (cystitis), prostate, urethra, or external genitalia. Another cause can be the leakage of blood proteins into the urinary tract as a result of injury and hemorrhage. In addition, contamination of urine with vaginal secretions or seminal fluid can result in a positive protein test or proteinuria.

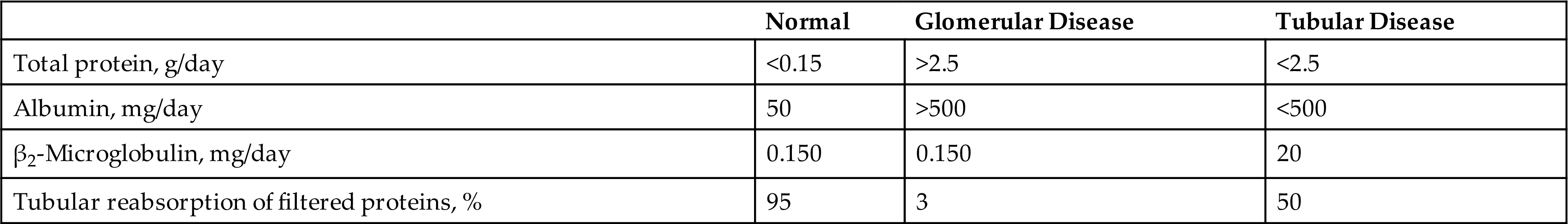

In summary, an increase in urine protein results from (1) increased plasma proteins overflowing into the urine (prerenal); (2) renal changes—glomerular, tubular, or both; or (3) inflammation and postrenal sources. Table 6.6 compares various proteins present in normal urine with urine characteristic of glomerular and tubular renal disease. Note the relative quantity of total protein present, the sizes of proteins that predominate, and the differences in the percentage of protein reabsorbed.

Table 6.6

Modified from Waller KV, Ward MW, Mahan JD, et al: Current concepts in proteinuria. Clin Chem 35:755–765, 1989.

Methods

Historically, qualitative or semiquantitative screening tests for urine protein relied on protein precipitation techniques. Proteins denature upon exposure to extremes of pH or temperature, and the most visible evidence of this is a decrease in solubility. For years, the SSA protein precipitation test was used but is replaced today by the rapid and economical reagent strip test for protein.

Positive urine protein results should be evaluated and correlated with urine specific gravity results. Large volumes of urine (polyuria) can produce a negative protein reaction despite significant proteinuria because the protein present is being excessively diluted. Likewise, a trace amount of protein present in dilute urine indicates greater pathology compared with a trace amount in concentrated urine. Note that an abnormally high specific gravity (>1.040) is a strong indicator that radiographic contrast media is present. It can be excreted in the urine for up to 3 days after a radiographic procedure.

Once the presence of an increased amount of urine protein has been established, accurate methods are available to differentiate and quantify the proteins. Electrophoresis, nephelometry, turbidimetry, and radial immunodiffusion methods are used and are discussed at length in clinical chemistry textbooks. Despite the qualitative or semiquantitative nature of the protein tests discussed in this chapter, they remain vital tools in the detection and monitoring of diseases that cause proteinuria.

Sulfosalicylic acid precipitation test

The sulfosalicylic acid (SSA) protein precipitation test detects all proteins in urine—albumin and globulins. This test is not frequently performed today because it is nonspecific and time-consuming. In addition, false-positive SSA precipitation results can be obtained when x-ray contrast media and certain drugs (e.g., penicillins) are present in high concentrations. If this occurs, additional testing is required before protein results can be reported. For more discussion and details on the performance of the SSA precipitation test, see Appendix E, Manual and Historic Methods of Interest. Note also that when needed today, automated chemistry analyzers have sensitive and specific assays for the quantitative determination of urine total protein.

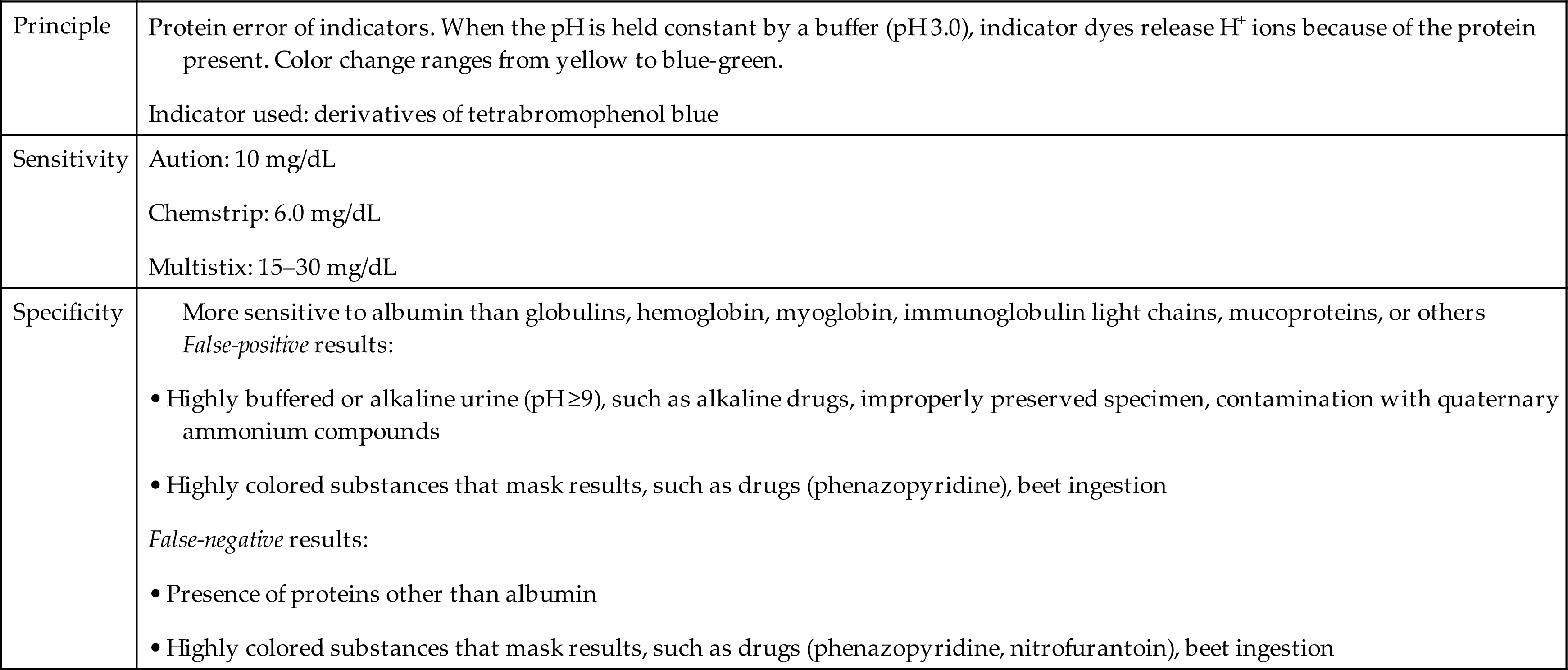

Reagent strip tests

Commercial reagent strips available for routine protein screening use the same principle, originally described by Sorenson in 1909 and termed the protein error of indicators. When the pH is held constant by a buffer, certain indicator dyes release hydrogen ions as a result of the presence of proteins (anions), causing a color change. The reaction pad is impregnated with a buffer that maintains the test area at pH 3.0. If protein is present, it acts as a hydrogen receptor, accepting hydrogen ions from the pH indicator and thereby causing a color change (Equation 6.2).E

Equation 6.2

Equation 6.2

The intensity of the color change is directly related to the amount of protein present. Protein reagent strip results are reported as concentrations in milligrams per deciliter (mg/dL) by matching the resultant reaction pad color with the color chart provided on the reagent strip container. Table 6.7 summarizes the protein reaction principle, sensitivity, and specificity of selected reagent strip brands.

Table 6.7

This method is more sensitive to albumin than to any other protein, and negative results will occur despite the presence of other proteins. Note that globulins, myoglobin, hemoglobin, immunoglobulin light chains (Bence Jones proteins), and mucoproteins are usually not detected by the reagent strip test because the concentrations of these proteins are usually insufficient to cause a color change. For example, when the reagent strip blood result is less than large (i.e., trace, small, or moderate), the concentration of hemoglobin is not high enough to contribute to the protein result.

Extremely alkaline (pH ≥9.0) or highly buffered urine can overwhelm the buffering capacity of the reaction pad to produce false-positive results. As with protein precipitation methods, adjusting the urine with acid to approximately pH 5.0 and retesting using the reagent strip test will produce an accurate protein result.

Tubular reabsorption of protein is a nonselective, competitive process. When an increased amount of protein is presented to the tubules for reabsorption, the tubules randomly reabsorb protein through a rate-limited process. As a result, the amount of albumin in urine increases as other proteins, which are normally not present, compete for reabsorption. Hence the reagent strip detection of albumin is often capable of detecting most instances of proteinuria.

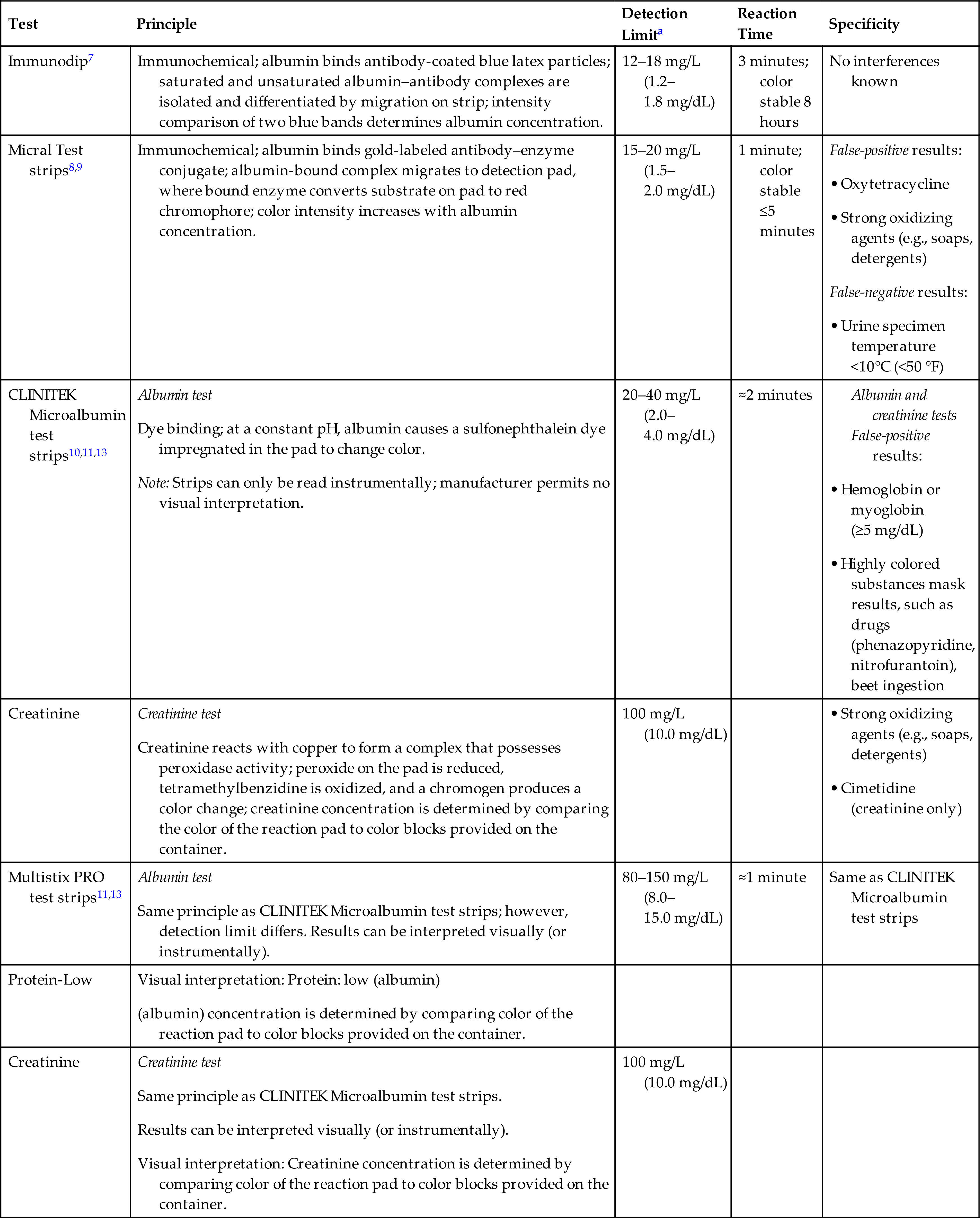

Sensitive albumin tests

Identification and management of patients at risk for kidney disease are enhanced greatly by the detection and monitoring of urine albumin excretion. Routine reagent strip methods are unable to detect the low levels of albumin excretion (10 to 20 mg/L or 1 to 2 mg/dL) that are clinically significant; hence sensitive albumin screening tests were developed. Periodic monitoring of urine for low-level albumin excretion greatly benefits individuals with diabetes, hypertension, or peripheral vascular disease. These patients have been shown to develop low-level albuminuria before nephropathy. Studies have demonstrated that early intervention to reduce hyperglycemia in diabetic patients or to normalize blood pressure in hypertensive people can reduce progression to clinical nephropathy.4–6

Several commercial reagent strip methods are available to screen urine for low-level increases in albumin; they include the OSOM ImmunoDip urine albumin test (Sekisui Diagnostics Corporation, Framingham, MA), the Micral Test (Roche Diagnostics), the Multistix PRO reagent strip test, and the CLINITEK Microalbumin reagent strip test (Siemens Healthcare Diagnostics Inc.) (Table 6.8).

Table 6.8

| Test | Principle | Detection Limita | Reaction Time | Specificity |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Immunodip7 | Immunochemical; albumin binds antibody-coated blue latex particles; saturated and unsaturated albumin–antibody complexes are isolated and differentiated by migration on strip; intensity comparison of two blue bands determines albumin concentration. | 12–18 mg/L (1.2–1.8 mg/dL) | 3 minutes; color stable 8 hours | No interferences known |

| Micral Test strips8,9 | Immunochemical; albumin binds gold-labeled antibody–enzyme conjugate; albumin-bound complex migrates to detection pad, where bound enzyme converts substrate on pad to red chromophore; color intensity increases with albumin concentration. | 15–20 mg/L (1.5–2.0 mg/dL) | 1 minute; color stable ≤5 minutes | False-positive results:False-negative results: |

| CLINITEK Microalbumin test strips10,11,13 | 20–40 mg/L (2.0–4.0 mg/dL) | ≈2 minutes | Albumin and creatinine tests • Hemoglobin or myoglobin (≥5 mg/dL) • Highly colored substances mask results, such as drugs (phenazopyridine, nitrofurantoin), beet ingestion | |

| Creatinine | Creatinine reacts with copper to form a complex that possesses peroxidase activity; peroxide on the pad is reduced, tetramethylbenzidine is oxidized, and a chromogen produces a color change; creatinine concentration is determined by comparing the color of the reaction pad to color blocks provided on the container. |

100 mg/L (10.0 mg/dL) | ||

| Multistix PRO test strips11,13 | 80–150 mg/L (8.0–15.0 mg/dL) | ≈1 minute | Same as CLINITEK Microalbumin test strips | |

| Protein-Low | ||||

| Creatinine | 100 mg/L (10.0 mg/dL) |

aSensitive albumin tests typically report protein concentrations in mg/L. Concentrations in mg/dL are provided to enable rapid comparison with reagent strip and sulfosalicylic acid (SSA) methods.

The ImmunoDip test is an immunochemical-based reagent strip reaction housed in a hard plastic case or stick. The test stick is placed into the urine specimen such that the vent hole located near one end is completely immersed. The unique design of the plastic housing controls the rate of urine flow over the reagent strip and the amount of urine that participates in the reaction. Another benefit of this unique housing is that once the test is completed, the result remains fixed and can be read up to 8 hours after testing without deterioration. Urine enters the vent hole of the test stick and albumin, if present, binds to monoclonal antibodies that are coupled to blue latex particles on the test pad. The degree of saturation of the latex particles with urine albumin determines the location to which the albumin–antibody–latex particle complex ultimately migrates by capillary action. Unsaturated complexes bind to the lower band or zone on the reagent strip, whereas saturated complexes migrate to the top zone.7 Comparing the intensity of the two blue bands provides semiquantitative albumin results. A lower band that is darker than the top band indicates an albumin concentration less than 12 mg/L (1.2 mg/dL); bands of equal intensity indicate an albumin level of 12 to 18 mg/L (1.2 to 1.8 mg/dL); and a top band darker than the lower band indicates an albumin concentration of 20 mg/L (2.0 mg/dL) or greater.

The Micral Test uses gold-labeled monoclonal antibodies in its immunochemical reagent strip test. In this reaction, albumin in the urine binds with a soluble antibody–enzyme conjugate that is impregnated on the reaction pad. Only the albumin–conjugate immunocomplex, moving by capillary action, passes into the reaction zone of the strip, because an intermediate zone immobilizes any excess, unbound conjugate. Once in the reaction zone, the enzyme (β-galactosidase) bound to the antibody reacts with the substrate (chlorophenol red galactoside) in the reaction zone to produce a red dye.8,9 Timing and technique are crucial; therefore, the manufacturer’s instructions must be followed to ensure accurate test results. The Micral Test method is capable of detecting as little as 15 to 20 mg/L (1.5 to 2 mg/dL) of human albumin in urine. A color chart to determine albumin results from 0 to 100 mg/L (0 to 10 mg/dL) is provided on the reagent strip container.

The CLINITEK Microalbumin reagent strip and Multistix PRO reagent strip (Siemens Healthcare Diagnostics Inc.) tests use a dye-binding method to determine low levels of urine albumin.10,11 A high-affinity sulfonephthalein dye impregnated in the pad changes color when it binds albumin. A buffer also impregnated on the reaction pad maintains a constant pH to ensure optimal protein discrimination and reactivity for albumin.12 The development of any blue color is due to the presence of albumin, and color changes on the reaction pad range from pale green to aqua blue. The CLINITEK Microalbumin reagent strip test, which must be read instrumentally, is able to detect albumin concentrations of 20 to 40 mg/L (2–4 mg/dL). In contrast, Multistix PRO reagent strips can be read visually or instrumentally, and the lowest level of protein detection is approximately 150 mg/L (15 mg/dL).Although these strips use essentially the identical chemical reaction, their sensitivity and the manufacturer-recommended reporting terminology differ, that is, milligrams per liter (mg/L) of albumin for the CLINITEK Microalbumin reagent strip test and milligrams per deciliter (mg/dL) of protein—low for the Multistix PRO reagent strip test.

Both reagent strips also include a reaction pad that determines semiquantitatively the urine creatinine concentration. Creatinine in the urine reacts with copper sulfate impregnated in the pad to form a copper–creatinine complex that possesses peroxidase activity.13 The reaction pad also is impregnated with a chromogen (tetramethylbenzidine) and a peroxide. Once the copper–creatinine complex is formed, it causes the peroxide to be reduced and the chromogen to oxidize, producing a color change on the reaction pad from orange to green (Equations 6.3 and 6.4). Note the similarity of this indicator reaction to that universally used in reagent strip tests for blood (see Equation 6.5).

Equation 6.3

Equation 6.3 Equation 6.4

Equation 6.4The inclusion of 4-hydroxy-2-methylquinoline in the reaction pad reduces interference from ascorbic acid and hemoglobin to greater than 22 mg/dL and 5 mg/dL, respectively.13 Assessment of albumin (protein) and creatinine on these reagent strips enables the estimation of an albumin-to-creatinine (A/C) or protein-to-creatinine ratio. For the Multistix PRO reagent strips, a table is provided to determine whether the protein-to-creatinine ratio is normal or abnormal. In contrast, the CLINITEK Microalbumin reagent strips, which are read instrumentally, report an estimate of the A/C ratio numerically as “less than 30 mg/g” (normal), “30 to 300 mg/g” (abnormal), or “greater than 300 mg/g” (abnormal). Conversion of results to SI units (i.e., milligrams of albumin per millimoles of creatinine) is also an option.

Note that not all positive sensitive albumin tests provide evidence of abnormality because extremely low levels of urine albumin, that is, concentrations less than 20 mg/L (<2.0 mg/dL), are considered normal. Low-level transient increases in albumin can occur with strenuous exercise, dehydration, and acute illness with fever. Keep in mind that overhydration (dilute urine) can mask increased urine albumin excretion. In these situations, determination of an A/C or protein-to-creatinine ratio reduces the numbers of false-positive and false-negative test results. Simultaneous urine creatinine measurement, as with CLINITEK Microalbumin and Multistix PRO reagent strips, accounts for these hydration effects and results in useful estimates of the A/C ratio or the protein-to-creatinine ratio.14 For example, concentrated urine that contains a small amount of protein can be correctly identified as “normal,” whereas a dilute urine specimen with a small amount of protein can be correctly identified as “abnormal.”

In summary, periodic monitoring for low-level urine albumin excretion should be performed for individuals at increased risk for developing kidney disease, such as those with hypertension or diabetes (type 1 or type 2). Early identification of kidney changes enables early intervention. Before a diagnosis of microalbuminuria is made, a positive screening test should be confirmed with a quantitative protein assay.

Blood

Clinical Significance

As discussed in Chapter 5, blood in urine can result in various presentations of color or may not be visually evident. Historically, color and clarity or microscopic viewing was used to detect the presence of blood in urine. Chemical methods now provide a rapid and sensitive means of detecting the presence of blood. Blood can enter the urinary tract anywhere from the glomeruli to the urethra or can be a contaminant in the urine as a result of the collection procedure used. Lysis of red blood cells (RBCs) with the release of hemoglobin is enhanced in alkaline or dilute urine (e.g., SG ≤1.010). Without current chemical methods, the presence of free hemoglobin in urine would go undetected. True hemoglobinuria—free hemoglobin from plasma passing the glomerular filtration barriers into the ultrafiltrate—is uncommon. Most often, intact RBCs enter the urinary tract and then undergo lysis to varying degrees. Hematuria is the term used to describe an abnormal quantity of RBCs in the urine, whereas hemoglobinuria indicates the urinary presence of hemoglobin.

Even small increases in the quantity of RBCs in urine are diagnostically significant. The chemical methods used detect the heme moiety—the tetrapyrrole ring (protoporphyrin IX) of a hemoglobin molecule with its centrally bound iron (Fe+2) atom. Note, however, that substances other than hemoglobin also contain a heme moiety such as myoglobin and cytochromes. Of particular interest is myoglobin (MW 17,000), an intracellular protein of muscle that will be increased in the bloodstream when muscle tissue is damaged by trauma or disease. Because of its small size, myoglobin readily passes the glomerular filtration barriers and is excreted in the urine. As a result, a positive chemical test for blood is nonspecific, indicating the presence of hemoglobin, RBCs, or myoglobin. Correlation with the urine microscopic results, the appearance of the patient’s plasma, and the results of plasma chemical tests, as well as the patient’s clinical presentation and history, may be necessary to determine which substances are present.

Hematuria and hemoglobinuria

A feature that helps distinguish between hematuria and hemoglobinuria is urine clarity. Hematuria is often evident by a cloudy or smoky urine specimen, whereas with true hemoglobinuria the urine is clear. Urine colors for both are similar, and color variations range from normal yellow to pink, red, or brown depending on the amount of blood or hemoglobin present. In addition, urine pH can affect the appearance of these specimens. For example, an alkaline pH promotes RBC lysis and hemoglobin oxidation.

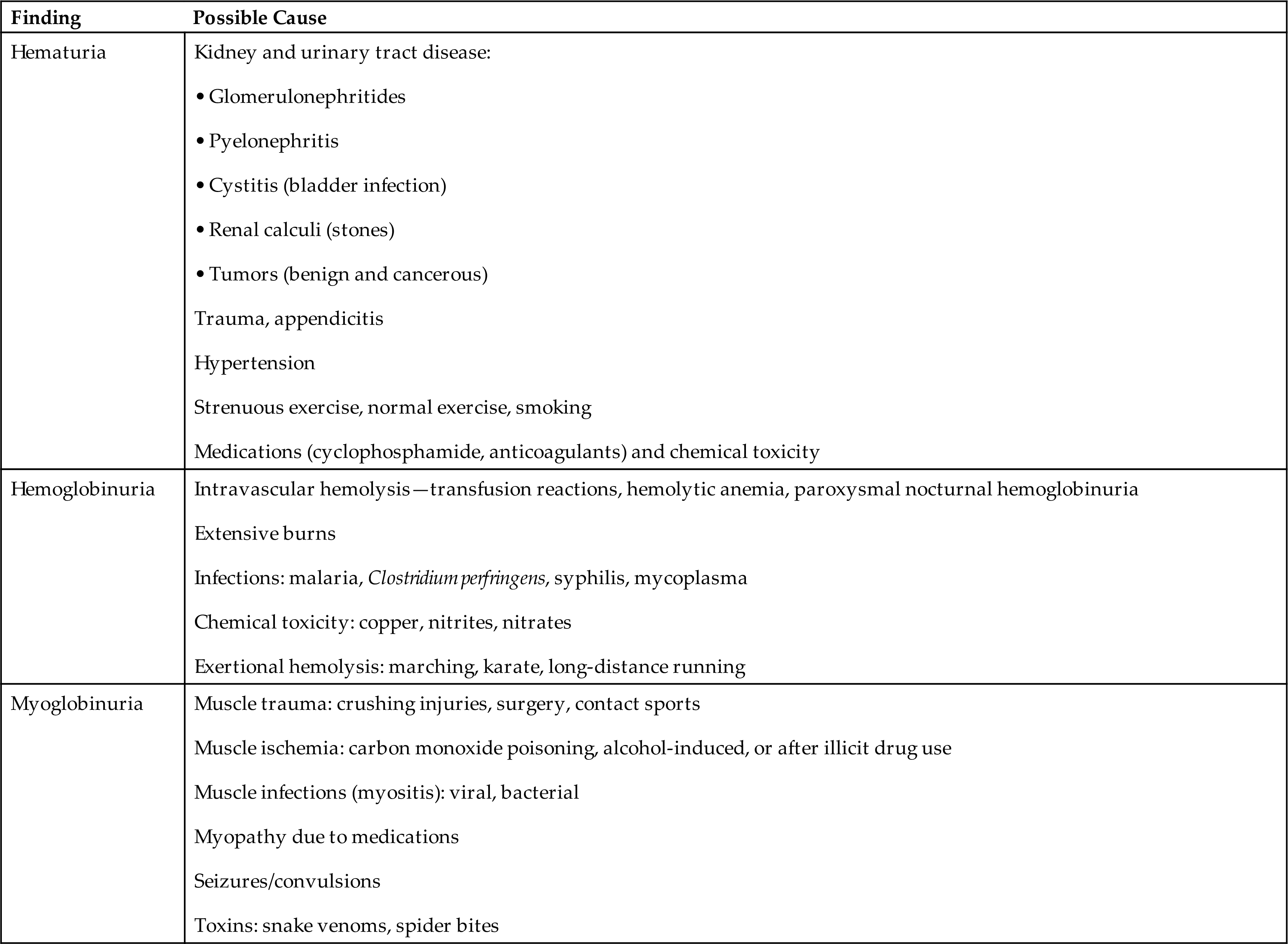

Numerous diseases of the kidneys or urinary tract, trauma, drug therapy, or strenuous exercise can result in hematuria and hemoglobinuria (Table 6.9). The detection of hematuria or hemoglobinuria is an early indicator of disease that is not always visually evident and when present always requires further investigation. The amount of blood in a urine specimen has no correlation with disease severity, nor can the amount of blood alone identify the location of the bleed. In combination with a microscopic examination, however, when RBCs are present in casts, a glomerular or tubular origin is indicated.

Table 6.9

| Finding | Possible Cause |

|---|---|

| Hematuria | |

| Hemoglobinuria | |

| Myoglobinuria |

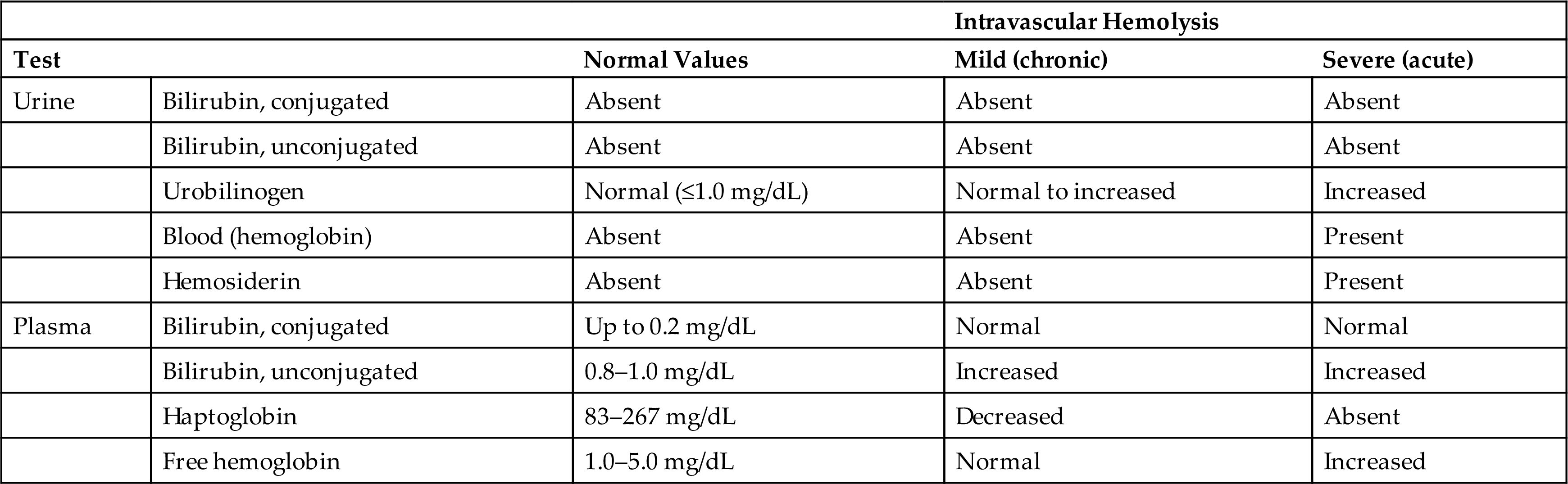

As previously stated, true hemoglobinuria is uncommon. Any condition resulting in intravascular hemolysis has the potential for producing hemoglobinuria. However, free hemoglobin in the bloodstream is bound rapidly by plasma haptoglobin. This hemoglobin–haptoglobin complex is too large to pass through the glomerular filtration barriers, so it remains in the plasma and is removed from the circulation by the liver, where it is metabolized. If all available plasma haptoglobin is bound, any additional free hemoglobin readily passes through the glomeruli with the ultrafiltrate. As dissociated dimers (MW ≈38,000), hemoglobin is reabsorbed principally by the proximal renal tubules and is catabolized to ferritin. Within the renal cells, ferritin is denatured to form hemosiderin, a storage form of iron that is insoluble in aqueous solutions. Hemosiderin usually appears in urine 2 to 3 days after a hemolytic episode and appears as yellow-brown granules (1) within sloughed renal tubular cells, (2) as free-floating granules, or (3) within casts. A Prussian blue staining test (Rous test) performed on a concentrated urinary sediment aids in visualization and identification of hemosiderin (for test details, see Appendix E). The presence of urinary hemosiderin is intermittent and should not be solely relied on to confirm a hemolytic episode or a chronic hemolytic condition. Table 6.10 compares urine and plasma values of analytes that can be used to monitor chronic and acute hemolytic episodes.

Table 6.10

Myoglobinuria

Myoglobin is a monomeric heme-containing protein involved in the transport of oxygen in muscles. Skeletal or cardiac muscle damage caused by a crushing injury, vigorous physical exercise, or ischemia causes the release of myoglobin into the blood. Because of its small molecular size (MW 17,000), myoglobin readily passes the glomerular filtration barrier. Its adverse renal effects are related to catabolism of the heme moiety and formation of free radicals during this process. Nontraumatic disorders such as alcohol overdose, toxin ingestion, and certain metabolic disorders can result in myoglobinuria (see Table 6.9). In fact, nontraumatic myoglobinuria with acute renal failure is common in patients with an alcohol overdose or a history of cocaine or heroin addiction.15 Myoglobinuria may be obvious based on the patient’s medical history and presenting symptoms, such as a crushing injury; however, nontraumatic rhabdomyolysis (muscle damage) has vague symptoms (nausea; weakness; swollen, tender muscles) and chemical analysis is often required for diagnosis.

Differentiation of hemoglobinuria and myoglobinuria

Myoglobin appears to be more toxic to renal tubules than hemoglobin. The reason for this is unclear but may be related to their difference in glomerular clearance and to other factors such as hydration, hypotension, and aciduria. Differentiating between hemoglobinuria and myoglobinuria can be difficult but is important (1) for diagnosis, (2) for predicting a patient’s risk for acute renal failure, and (3) for treatment.

Visual inspection of urine and plasma can help distinguish between hemoglobinuria and myoglobinuria, but these gross observations are of limited value. Urine colors can be similar—hemoglobinuria causes a red or brown urine, whereas myoglobinuria causes a pink, red, or brown urine. Hemoglobin is not cleared as rapidly from the plasma as myoglobin; therefore with hemoglobinuria, the plasma often shows various degrees of hemolysis. In contrast, myoglobin is rapidly cleared by glomerular filtration and the plasma appears normal.

Historically, the differentiation of hemoglobin and myoglobin in clinical laboratories has relied on the ammonium sulfate precipitation method. This method was based on the different solubility characteristics of hemoglobin and myoglobin when saturated with 80% ammonium sulfate. At this salt concentration, hemoglobin precipitates out of solution, whereas myoglobin remains soluble in the supernatant. Only red or brown urine is tested, and an assessment is made by observing whether the urine color precipitates out of or remains in the supernate after 80% saturation with ammonium sulfate. Because of reliance on visual observation, this method does not detect low levels of hemoglobinuria (<30 mg/dL). At these low levels, false-negative results for hemoglobin would be reported because no visible precipitation is observed.15 With the availability of sensitive and specific immunoassays and high-performance liquid chromatography methods, the ammonium sulfate precipitation method for differentiation is no longer clinically useful.

The following approach to differentiating between hemoglobin and myoglobin is similar to a protocol recommended by Shihabi, Hamilton, and Hopkins in 1989 for development of a “rhabdomyolysis/hemolysis profile.”15 Normally, myoglobin excretion is less than 0.04 mg/dL; however, during extreme exercise, it can increase to 40 times the normal rate without adverse renal effects. Only urine myoglobin concentrations exceeding 1.5 mg/dL are associated with a patient’s risk of developing acute renal failure. Because available blood reagent strip tests are sensitive and capable of detecting approximately 0.04 mg/dL of myoglobin, urine from patients suspected of having rhabdomyolysis should be diluted 1:40 before testing for myoglobin. If the blood reagent strip test is negative when testing the diluted urine sample, no significant rhabdomyolytic process is occurring. However, if the test is positive, the creatine kinase level should be determined using the patient’s plasma. A rhabdomyolytic process will cause the plasma creatine kinase concentration to exceed the normal upper reference limit by 40 times or greater. This will occur because of the high concentration of creatine kinase in muscle cells. If the diagnosis of hemoglobinuria versus myoglobinuria is still questionable, test the patient’s plasma for myoglobin. Rhabdomyolysis will cause a markedly elevated plasma myoglobin level. Table 6.11 compares laboratory findings that aid in the differential diagnosis of hemoglobinuria and myoglobinuria.

Method

Table 6.12 summarizes the principle, sensitivity, and specificity of the blood reaction pad on selected reagent strip brands. Despite various manufacturers, reagent strip tests for blood detection are based on the same chemical principle: the pseudoperoxidase activity of the heme moiety. The reagent pad is impregnated with the chromogen tetramethylbenzidine and a peroxide. Through pseudoperoxidase activity of the heme moiety, peroxide is reduced and the chromogen becomes oxidized, producing a color change on the reaction pad (Equation 6.5). Depending on the reagent strip manufacturer, intact RBCs may be lysed on the reaction pad; this causes the release of hemoglobin and the development of a mottled or dotted pattern.

Equation 6.5

Equation 6.5

Table 6.12

| Principle | |

| Chromogen used: tetramethylbenzidine | |

| Sensitivity | |

| Specificity | |

| False-positive results: | |

| False-negative or decreased results: |

aSee Chapter 7, Box 7.2, for conversion of “cells per high-power field (HPF)” to “cells per microliter (μL).” Note that the number of cells seen per HPF will vary with the protocol used to prepare the urine sediment (i.e., sediment concentration) and the optics of the microscope, which determines the size of the field of view (Chapter 7,subsection Standardization of Sediment Preparation).

Color charts are provided on the labels of reagent strip containers for visual assessment of the reaction pads. A homogeneous color change results from hemoglobin, whereas a mottled pattern can occur when intact RBCs are lysed and their hemoglobin is released. Test results can be reported as negative, trace, small, moderate, or large, or the plus (1+, 2+, 3+) system can be used.

Because intact RBCs are not “dissolved” in urine, they can settle out or can be removed from the urine by centrifugation. Therefore, it is important that urine specimens are well mixed and tested for blood before centrifugation. In contrast, hemoglobin is dissolved in the urine and will not settle out. In other words, hemoglobin is detectable in the urine before centrifugation and in the supernatant afterward. To detect “intact” RBCs, a lysing agent is needed on the reaction pad to cause release of hemoglobin from the cells. Note that some reagent strip brands do not include a lysing agent (e.g., Aution sticks 9 EB, ARKRAY, Inc., Kyoto, Japan). When using these strips, the presence of increased numbers of “intact” RBCs will be missed if a microscopic examination is not performed because only hemoglobin is detected.

Because proteins other than hemoglobin, such as myoglobin, contain the heme moiety, blood reagent strip tests can detect their presence. All reagent strips, regardless of their manufacturer, are equally specific for hemoglobin and myoglobin. Other heme-containing substances, such as mitochondrial cytochromes, are present in quantities too small to be detected. Table 6.12 relates the sensitivity for hemoglobin to that for RBCs. The assumption is that approximately 30 picograms of hemoglobin is contained in each RBC; therefore 10 lysed RBCs are equivalent to approximately 0.03 mg/dL hemoglobin.16

Blood reagent strips are one of several reagent strip chemistry tests susceptible to ascorbic acid interference. Whenever RBCs are observed in microscopic examination of the urine sediment, but the chemical examination is negative for blood, ascorbic acid (also called vitamin C) should be suspected. Ascorbic acid is a strong reducing substance that reacts directly with peroxide (H2O2) impregnated on the blood reagent pad and removes it from the intended reaction, thereby preventing oxidation of the chromogen. As a result, false-negative or falsely low reagent strip results for blood can be obtained from specimens that contain ascorbic acid. Chemstrip reagent strips have successfully eliminated this interference through the use of an “iodate scavenger pad.” On Chemstrip reagent strips, a proprietary iodate-impregnated mesh overlies the blood reagent pad and oxidizes any ascorbic acid before it can interfere in the chemical reaction. Excretion and detection of ascorbic acid in urine, as well as a summary of the reagent strip tests affected by ascorbic acid, are discussed later in this chapter. Note that the potential for ascorbic acid to cause a false-negative blood reagent strip test emphasizes the need to include a microscopic examination whenever screening for hematuria.17

False-positive results for urinary blood can be obtained when menstrual or hemorrhoidal blood contaminates the urine. Other causes include strong oxidizing agents such as sodium hypochlorite or hydrogen peroxide that directly oxidize the chromogen or microbial peroxidases produced by certain bacterial strains (e.g., Escherichia coli) that can catalyze the reaction in the absence of the intended pseudoperoxidase, hemoglobin. Refer to Table 6.12 and the manufacturer’s insert for other substances that can affect blood reagent strip results.

Leukocyte Esterase

Clinical Significance

Normally, a few white blood cells (leukocytes) are present in urine: 0 to 8 per high-power field or approximately 10 white blood cells per microliter. The number of white blood cells per microliter varies slightly depending on the standardized procedure used to prepare the sediment for microscopic examination. Increased numbers of leukocytes in urine indicate inflammation, which can be present anywhere in the urinary system—from the kidneys to the lower urinary tract (bladder, urethra). The presence of approximately 20 or more white blood cells per microliter is a good indication of a pathologic process. Increased numbers of white blood cells are found more often in urine from women than from men, in part because of the greater incidence of UTI in women, but also because of the increased potential for a woman’s urine to be contaminated with vaginal secretions.

Before the development of reagent strip tests that detect leukocyte esterase, the presence of white blood cells was determined solely by microscopic examination of urine sediment. The chemical detection of leukocyte esterase provides a means to determine the presence of white blood cells even when they are no longer viable or visible. Remember, white blood cells are particularly susceptible to lysis in hypotonic and alkaline urine, as well as from bacteriuria, high storage temperatures, and centrifugation. Therefore the presence of significant numbers of white blood cells or a large quantity of leukocyte esterase in urine may indicate an inflammatory process within the urinary tract or, in urine from women, could indicate contamination with vaginal secretions.

Increased numbers of white blood cells in urine can be present with or without bacteriuria (bacteria in the urine) (see Table 6.13). However, the most commonly encountered cause of leukocyturia is a bacterial infection involving the kidneys (pyelonephritis) or the lower urinary tract, such as cystitis or urethritis. In these conditions, leukocyturia is usually accompanied by bacteriuria of varying degrees. In contrast, kidney and UTIs involving trichomonads, mycoses (e.g., yeast), chlamydia, mycoplasmas, viruses, or tuberculosis cause leukocyturia or pyuria without bacteriuria.

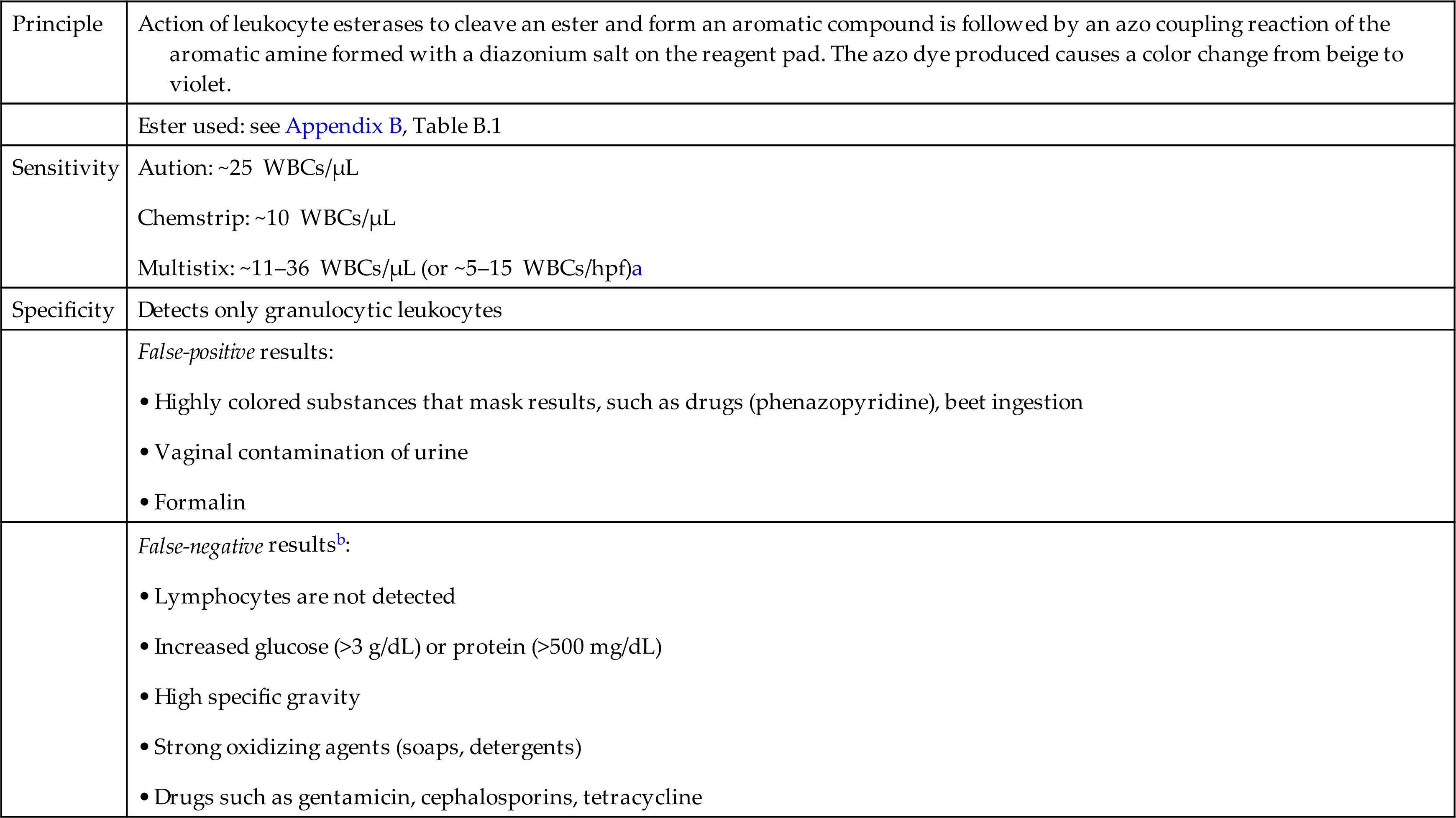

Methods

Reagent strip tests detect leukocyte esterases that are found in the azurophilic granules of granulocytic leukocytes. These granules are present in the cytoplasm of all granulocytes (neutrophils, eosinophils, and basophils), monocytes, and macrophages. Therefore the reagent strip method does not detect lymphocytes. Several advantages of the leukocyte esterase screening test are its ability (1) to detect the presence of intact and lysed white blood cells and (2) to serve as a screening test for white blood cells that is independent of procedural variations for sediment preparation. Table 6.14 summarizes the principle, sensitivity, and specificity of the leukocyte esterase reaction on selected reagent strip brands.

Table 6.14

| Principle | Action of leukocyte esterases to cleave an ester and form an aromatic compound is followed by an azo coupling reaction of the aromatic amine formed with a diazonium salt on the reagent pad. The azo dye produced causes a color change from beige to violet. |

| Ester used: see Appendix B, Table B.1 | |

| Sensitivity | |

| Specificity | Detects only granulocytic leukocytes |

| False-positive results: | |

| False-negative resultsb: |

aSee Chapter 7, Box 7.2, for conversion of “cells per high-power field (HPF)” to “cells per microliter (μL).” Note that the number of cells seen per HPF will vary with the protocol used to prepare the urine sediment (i.e., sediment concentration) and the optics of the microscope, which determines the size of the field of view (Chapter 7,subsection Standardization of Sediment Preparation).

bNote that oxalic acid does not affect leukocyte esterase results because oxalic acid does not exist in urine that has a pH greater than 4.5; it dissociates. At the pH of human urine, it is present exclusively as its salt—oxalate.

All reagent strip tests for leukocyte esterase detection are based on the action of the leukocyte esterase to cleave an ester, impregnated in the reagent pad, to form an aromatic compound. Immediately after hydrolysis of the ester, an azo coupling reaction takes place between the aromatic compound produced and a diazonium salt provided on the test pad. The end result is an azo dye with a color change of the reagent pad from beige to violet (Equations 6.6 and 6.7).

Equation 6.6

Equation 6.6

Equation 6.7

Equation 6.7

This screening test for leukocyte esterase initially detects about 10 to 25 white blood cells per microliter. However, note that a negative result does not rule out the presence of increased numbers of white blood cells; it only indicates that the amount of leukocyte esterase present is insufficient to produce a positive test. This can occur despite increased numbers of white blood cells when (1) the white blood cells present are lymphocytes or (2) the urine is significantly dilute (hypotonic). Results for this chemical test often are reported as negative or positive. The quantitative evaluation of white blood cells in urine sediment is part of the microscopic examination; however, lysis of these cells may have occurred. Therefore this reagent strip test provides a means to identify urine specimens that require further evaluation because of increased quantities of leukocyte esterases (i.e., increased numbers of granulocytic leukocytes).

False-positive results for leukocyte esterase are most often obtained on urine specimens contaminated with vaginal secretions. Other potential sources of false-positive results are drugs or foodstuffs that color the urine red or pink in an acid medium. These substances (e.g., phenazopyridine, nitrofurantoin, beets) mask the reagent pad so that its color resembles that of a positive reaction.

Substances that can reduce the sensitivity of the leukocyte esterase reaction and cause false-negative results include increased protein (500 mg/dL), increased glucose (≥3 g/dL), and high specific gravity. Antibiotics, such as gentamicin or cephalosporin, and strong oxidizing agents (which interfere with reaction pH) can also produce false-negative results.

Note that oxalic acid does not interfere with the leukocyte esterase reaction when testing urine without an acid preservative. Because human urine always has a pH greater than 4.5, oxalic acid cannot exist but dissociates and is present exclusively as its salt—oxalate. However, if acidifying agents are added to a urine specimen after collection to reduce the pH to 4.4 or lower, oxalate can be converted (reduced) to oxalic acid. If this acidified urine is tested, a falsely low or negative result for leukocyte esterase could be obtained.

Nitrite

Clinical Significance

Routine screening for urine nitrite provides an important tool to identify UTI. A urinary tract infection (UTI) can involve the bladder (cystitis), the renal pelvis and tubules (pyelonephritis), or both. Two pathways for the development of UTI are possible: (1) the movement of bacteria up the urethra into the bladder (ascending infection) and (2) the movement of bacteria from the bloodstream into the kidneys and urinary tract. Ascending infections represent the more prevalent type of UTI. The microorganisms involved are usually gram-negative bacilli that are normal flora of the intestinal tract. The most common infecting microorganism is Escherichia coli, followed by Proteus species, Enterobacter species, and Klebsiella species. UTI occurs eight times more often in females than in males. In addition, catheterized individuals, regardless of gender, have a high incidence of infection. Various factors involved in the incidence of UTI are discussed in Chapter 8, subsection Tubulointerstitial Disease and Urinary Tract Infections.

Normally, the bladder and the urine are sterile. This sterility is maintained by the constant flushing action when urine is voided. A UTI can begin as a result of urinary obstruction (e.g., tumor), bladder dysfunction, or urine stasis. Once bacteria have established a bladder infection (cystitis), ascension to the kidneys is possible but is not inevitable. UTIs can be asymptomatic (asymptomatic bacteriuria), particularly in the elderly, and the nitrite test provides a means of identifying these patients. With early intervention, the spread of infection to the kidneys and the potential to develop renal complications can be prevented.

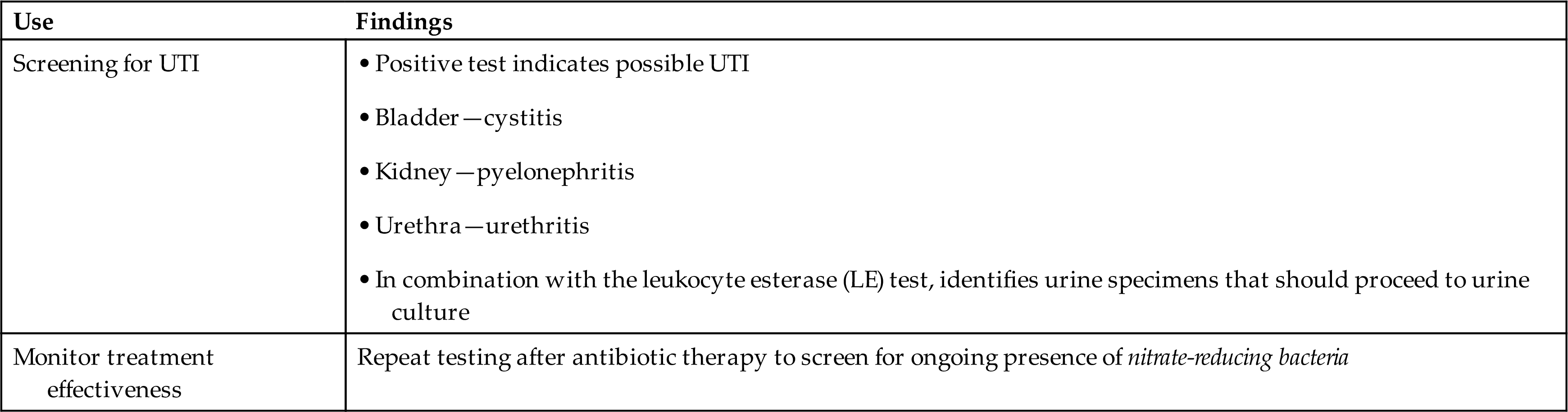

Screening urine for nitrite and leukocyte esterase provides a means of identifying patients with bacteriuria. Normally, nitrates are consumed in the diet (e.g., in green vegetables) and are excreted in the urine without nitrite formation. When nitrate-reducing bacteria are infecting the urinary tract and adequate bladder retention time is allowed, these bacteria convert dietary nitrate to nitrite. However, not all bacteria contain the enzyme (nitrate reductase) necessary to reduce dietary nitrates to nitrite. Some bacteria commonly involved in UTIs that do not reduce nitrate include gram-positive Staphylococcus saprophyticus and Enterococcus spp. Factors that affect nitrite formation and detection include the following: (1) The infecting microbe must be a nitrate reducer, (2) adequate time (a minimum of 4 hours) must be allowed between voids for bacterial conversion of nitrate to nitrite, and (3) adequate dietary nitrate must be consumed and available for conversion. In addition, nitrite detection can be reduced by subsequent conversion by bacteria of nitrite to nitrogen or by antibiotic therapy that inhibits bacterial conversion of nitrate to nitrite. To appropriately screen for nitrite, the urine specimen of choice is a first morning void or a specimen collected after the urine has been retained in the bladder for at least 4 hours. This latter requirement can be difficult because frequent micturition is a common presenting symptom of UTI.

The screening test for urine nitrite does not replace a traditional urine culture, which can also specifically identify and quantify the bacteria present. The nitrite test simply provides a rapid, indirect means of identifying the presence of nitrate-reducing bacteria in urine at minimal expense. In doing so, the test also helps identify patients with asymptomatic bacteriuria that might otherwise go undiagnosed. It is also important to note that ascorbic acid in urine can interfere with the nitrite test, causing false-negative results (see Ascorbic Acid section later in this chapter). See Table 6.15 for diagnostic uses of the nitrite test alone or in combination with the leukocyte esterase.

Table 6.15

| Use | Findings |

|---|---|

| Screening for UTI | |

| Monitor treatment effectiveness | Repeat testing after antibiotic therapy to screen for ongoing presence of nitrate-reducing bacteria |

aOrganisms that do not reduce nitrate to nitrite are not detected, such as non–nitrate-reducing bacteria, yeast, trichomonads, and Chlamydia.

Methods