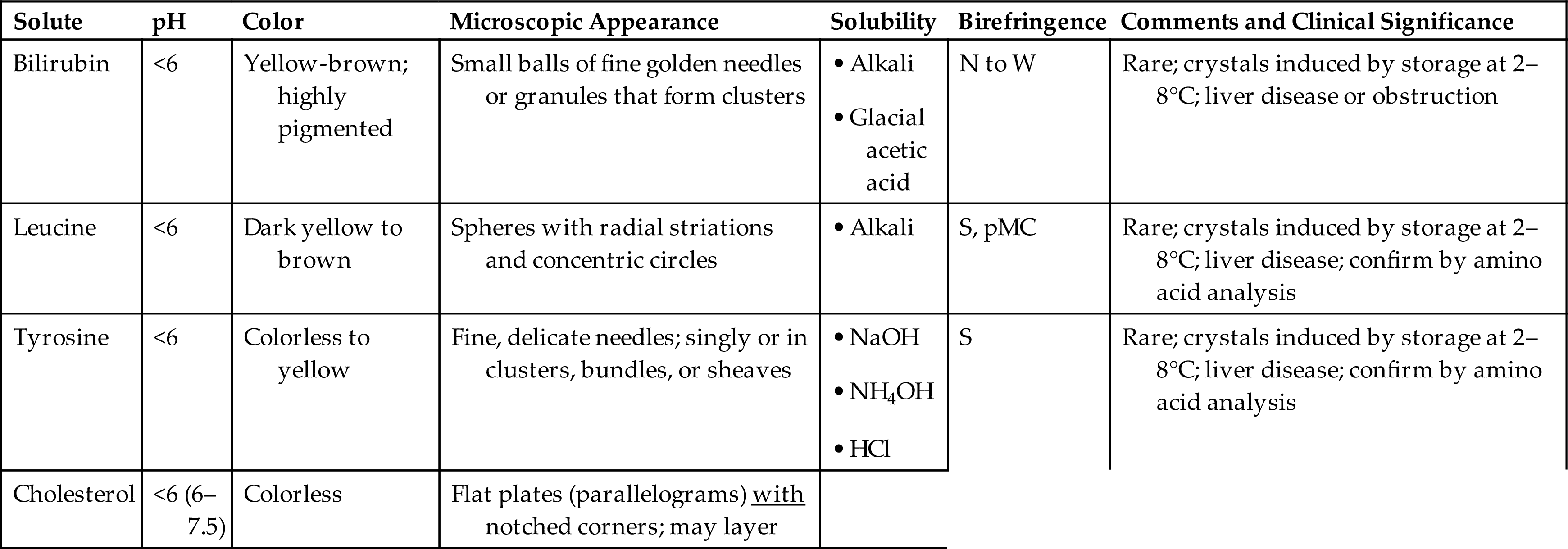

| W | Rare; crystals induced by storage at 2–8°C; indicates lipiduria, accompanies proteinuria and other forms of urinary fat | |||||

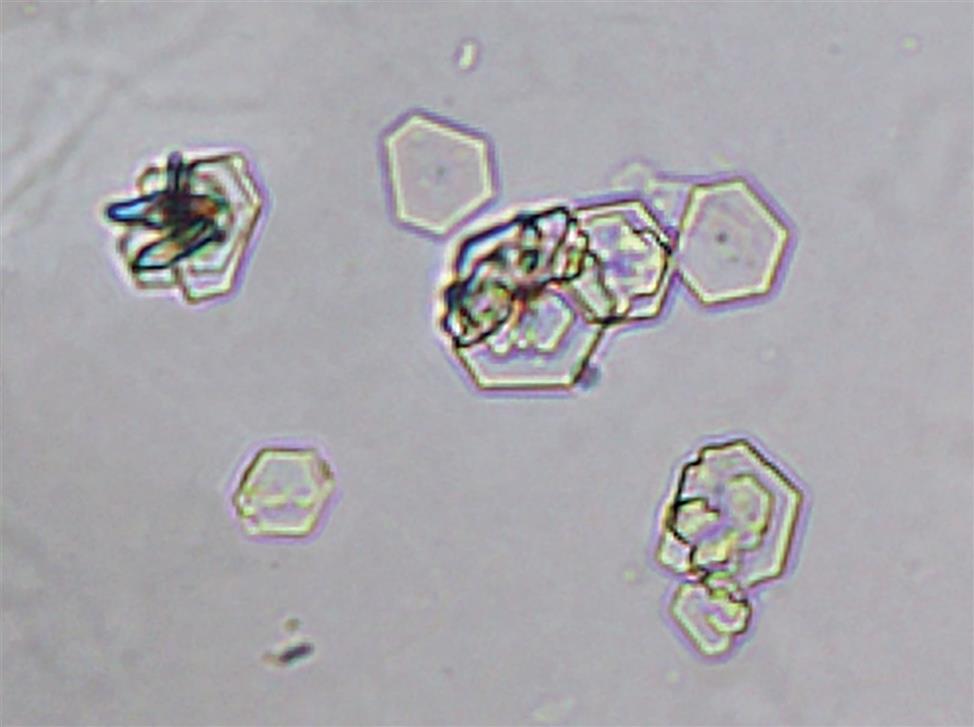

| Cystine | <6 (6–7.5) | Colorless | Hexagonal plates, often layer | W to M | Rare; metabolic disorder (cystinosis or cystinuria); confirm by nitroprusside test | |

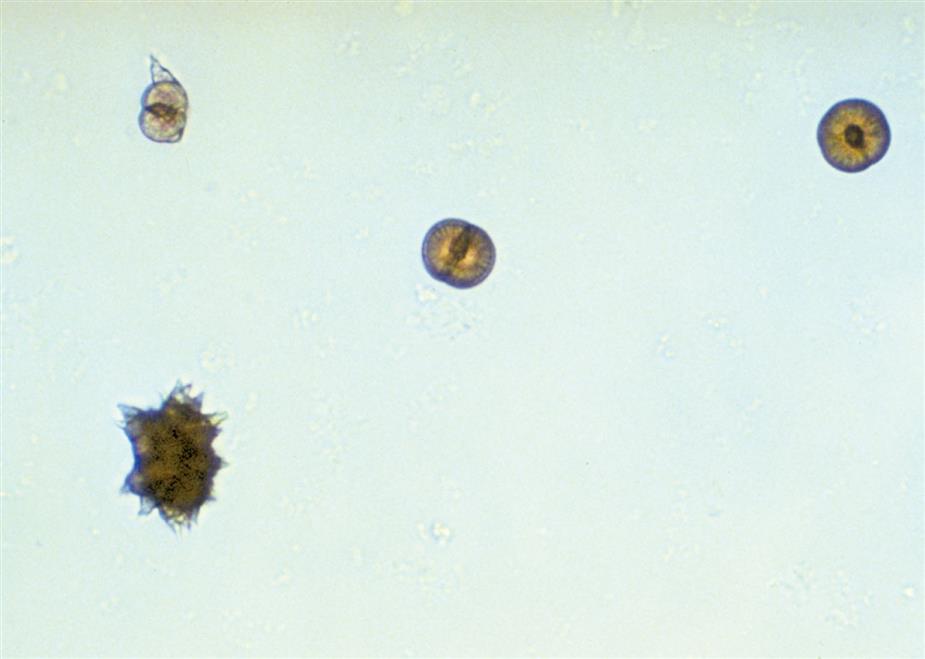

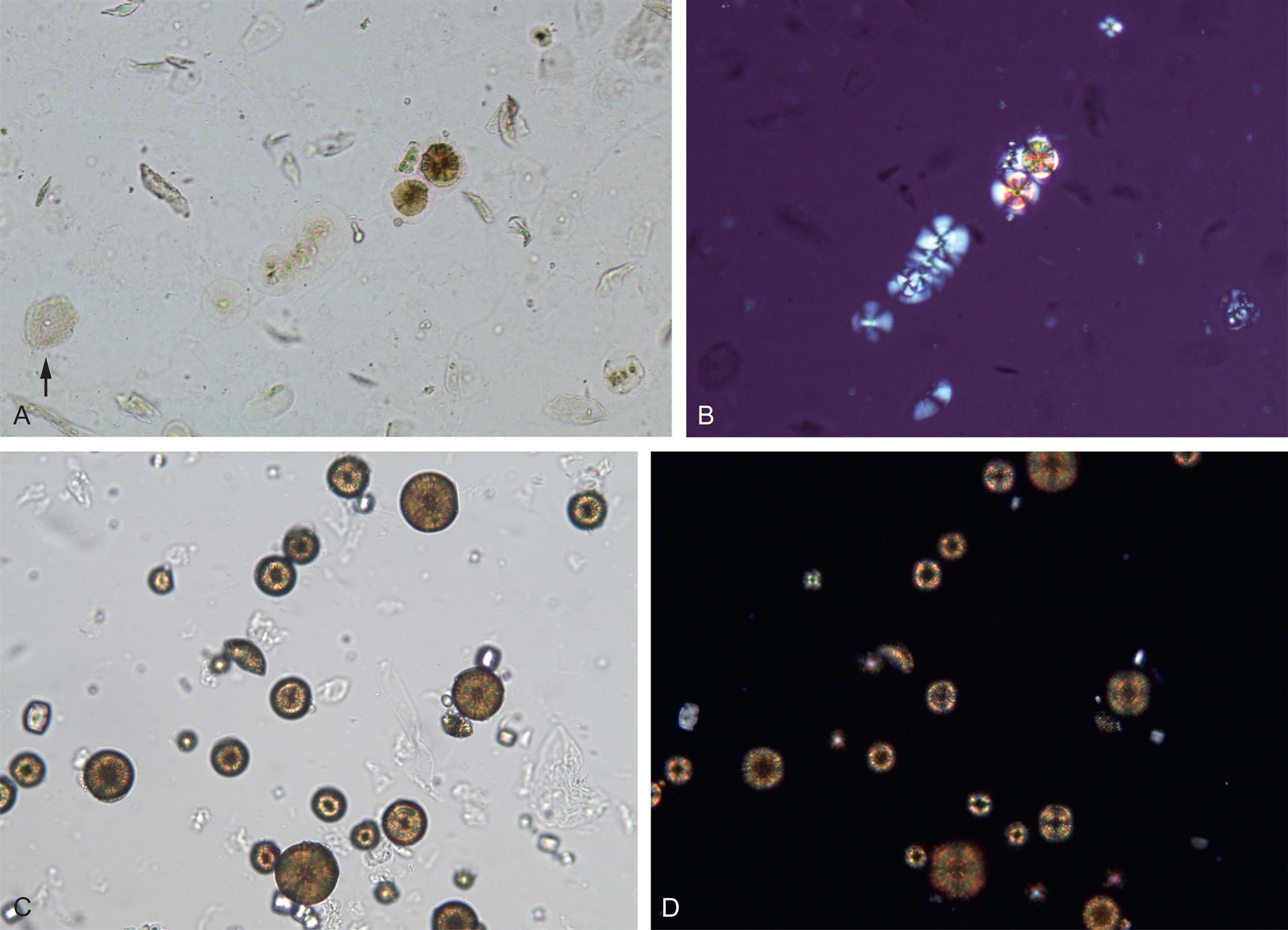

| 2,8, Dihydroxyadenine | Any | Dark yellow to brown | Spherical crystals with dark centers and radiating rays | S, pMC | ||

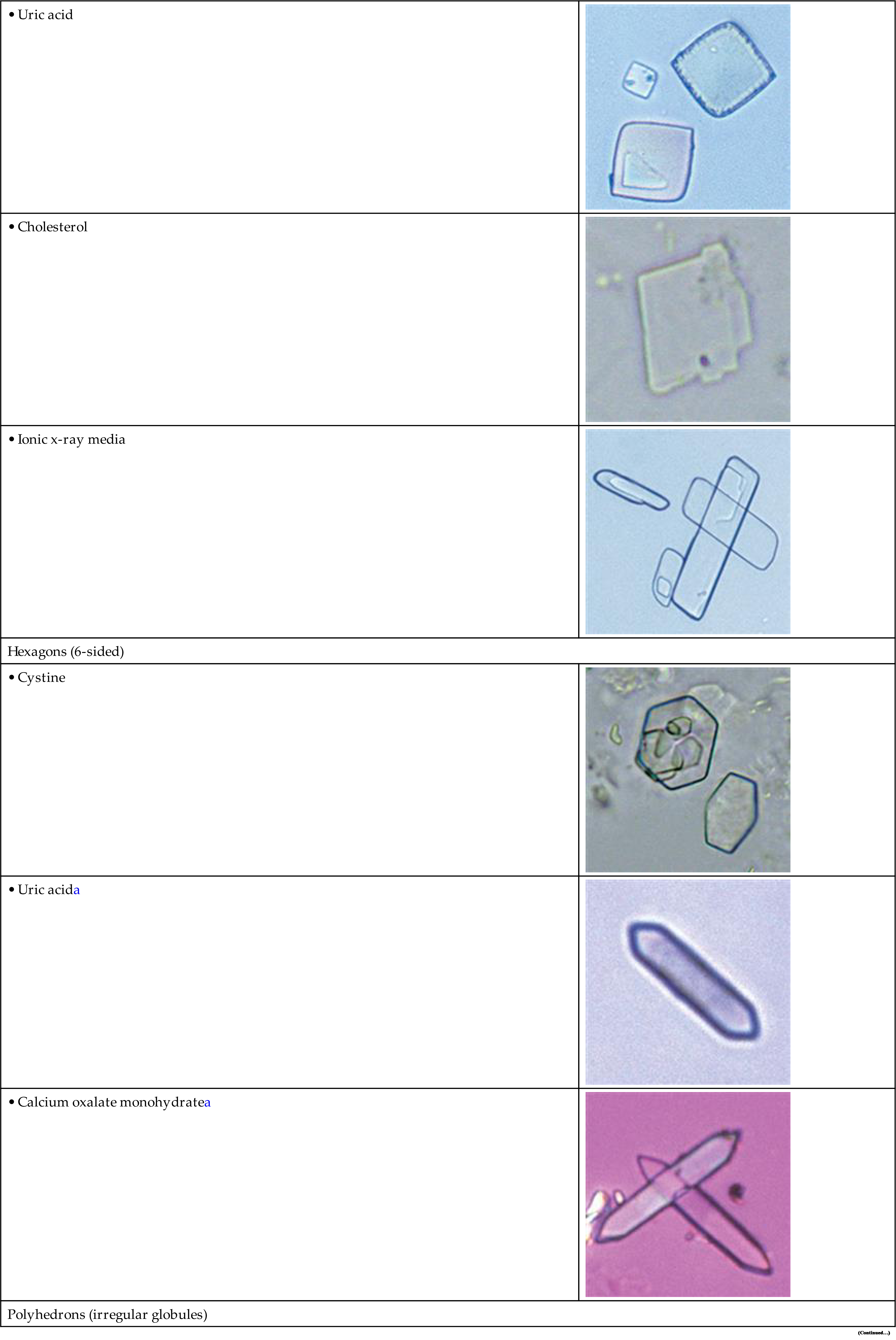

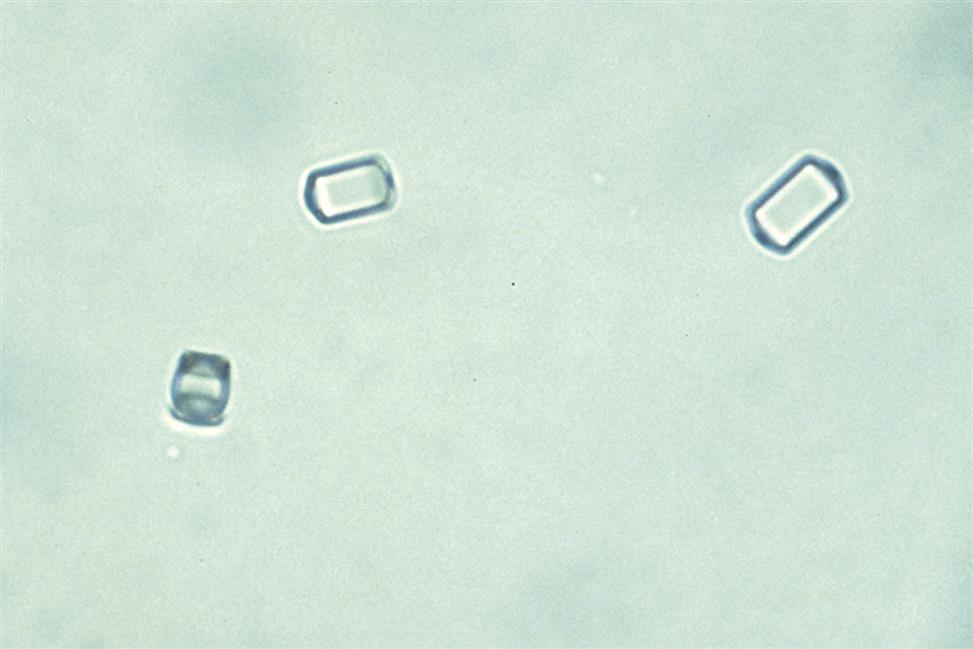

| ‘Ionic’ radiographic media (iatrogenicb) | <6 | Colorless | Flat, elongated plates (parallelograms); usually without notched corner | S, P | Following radiographic procedures; causes high SG (>1.040) |

aNote that any ‘abnormal’ crystal should be confirmed by chemical test or clinical history before reporting; if unable to confirm, consult with healthcare provider.

bAn iatrogenic solute is one not native to the human body; it originates from a treatment (e.g., imaging procedures, medications).

M, Moderate; P, polychromatic; pMC, forms pseudo-Maltese cross pattern; S, strong; SG, specific gravity; W, weak.

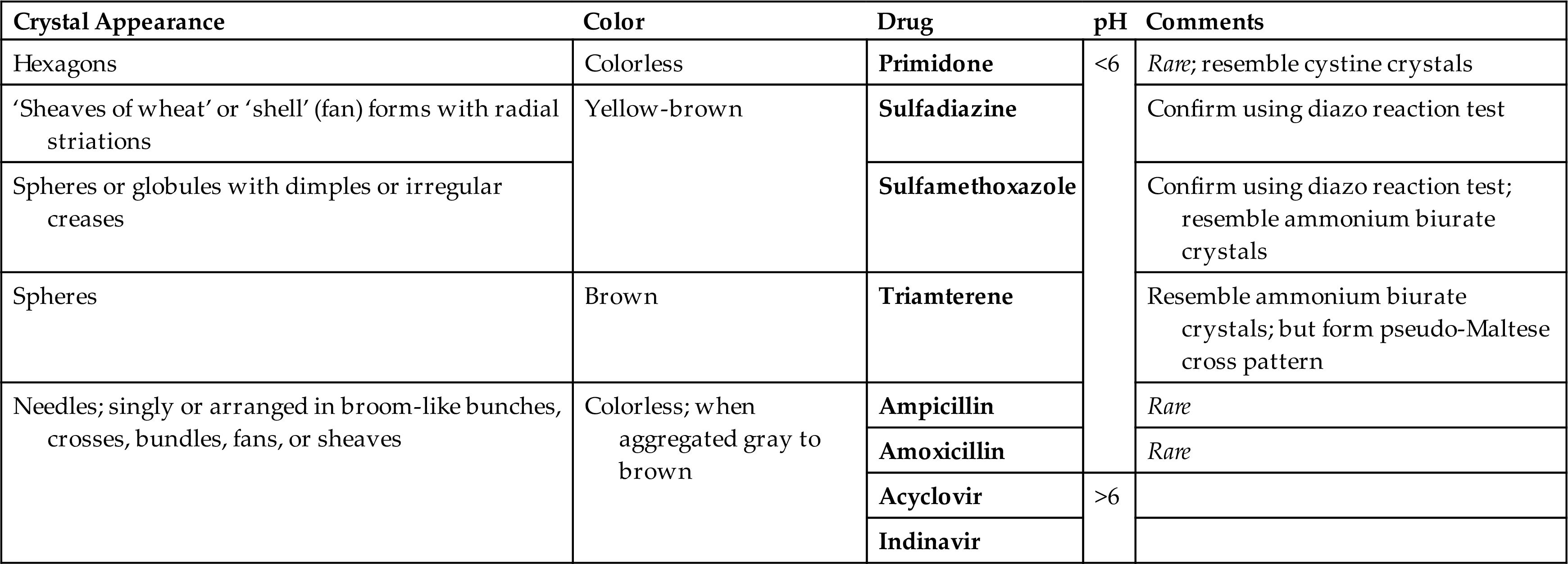

Table 7.13

Table 7.16

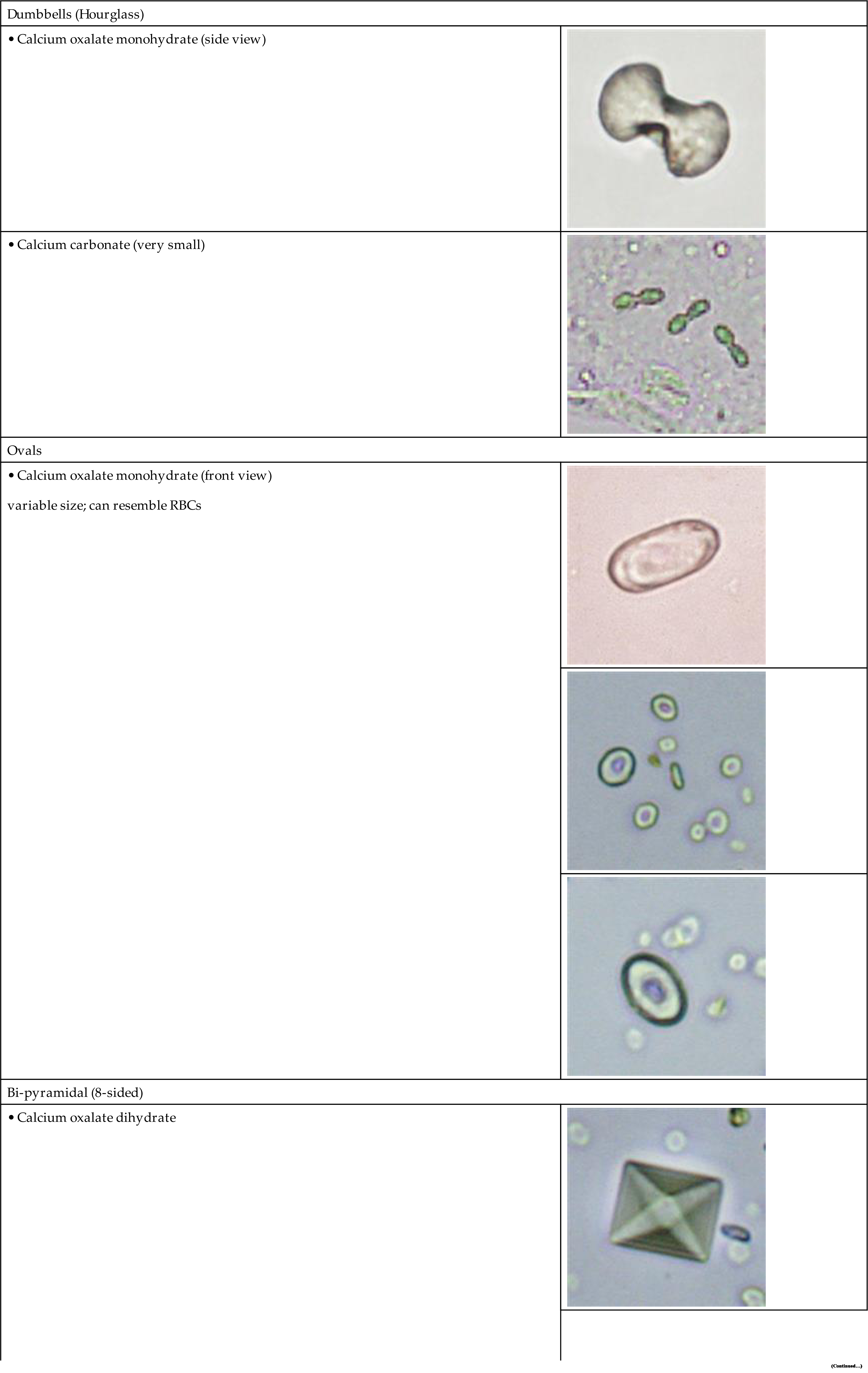

| Dumbbells (Hourglass) | |

| |

| |

| Ovals | |

| variable size; can resemble RBCs |  |

| |

| |

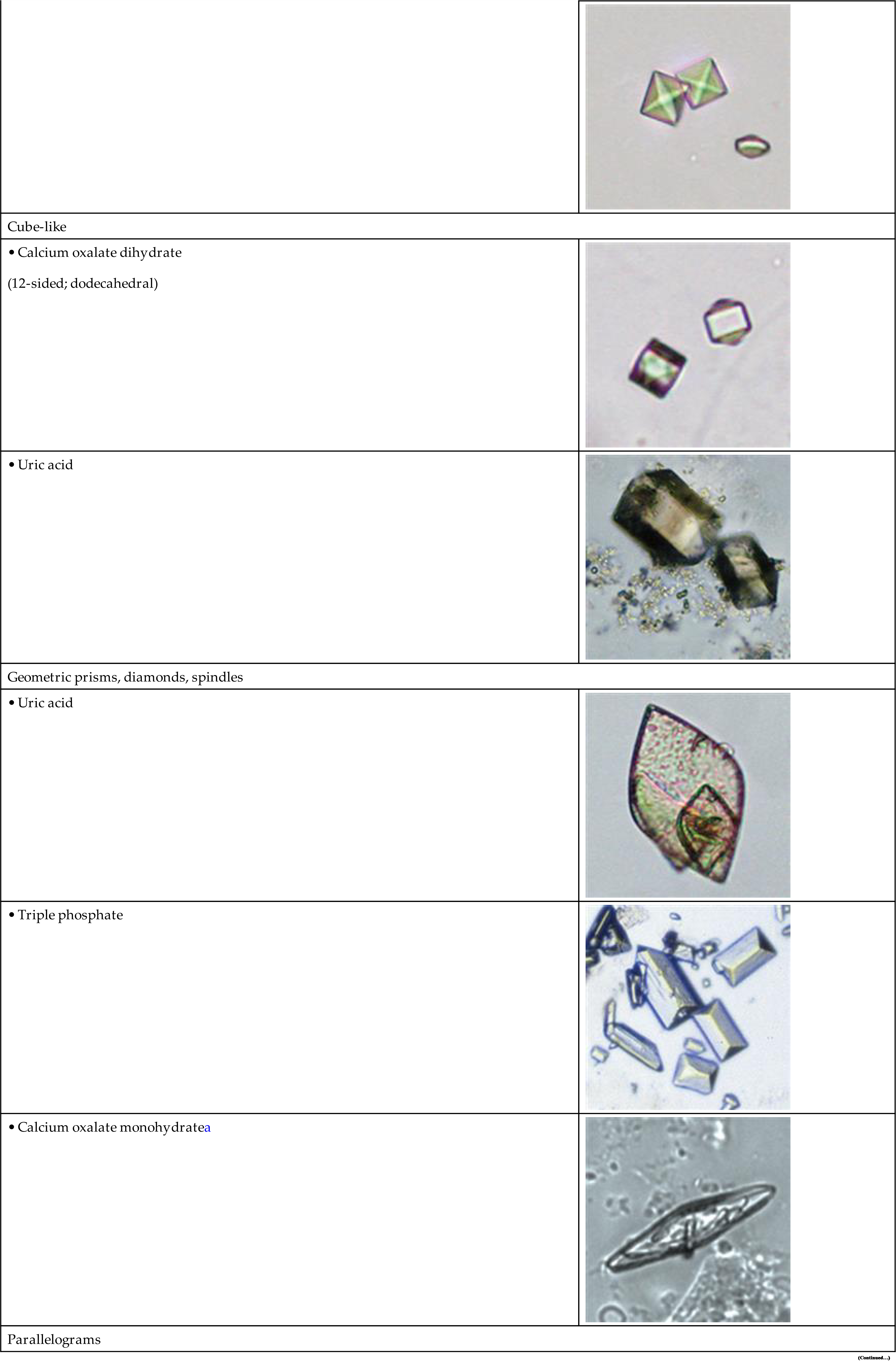

| Bi-pyramidal (8-sided) | |

| |

| |

| Cube-like | |

| (12-sided; dodecahedral) |  |

| |

| Geometric prisms, diamonds, spindles | |

| |

| |

• Calcium oxalate monohydratea |

|

| Parallelograms | |

|---|---|

| |

| |

| |

| Hexagons (6-sided) | |

| |

• Uric acida |

|

• Calcium oxalate monohydratea |

|

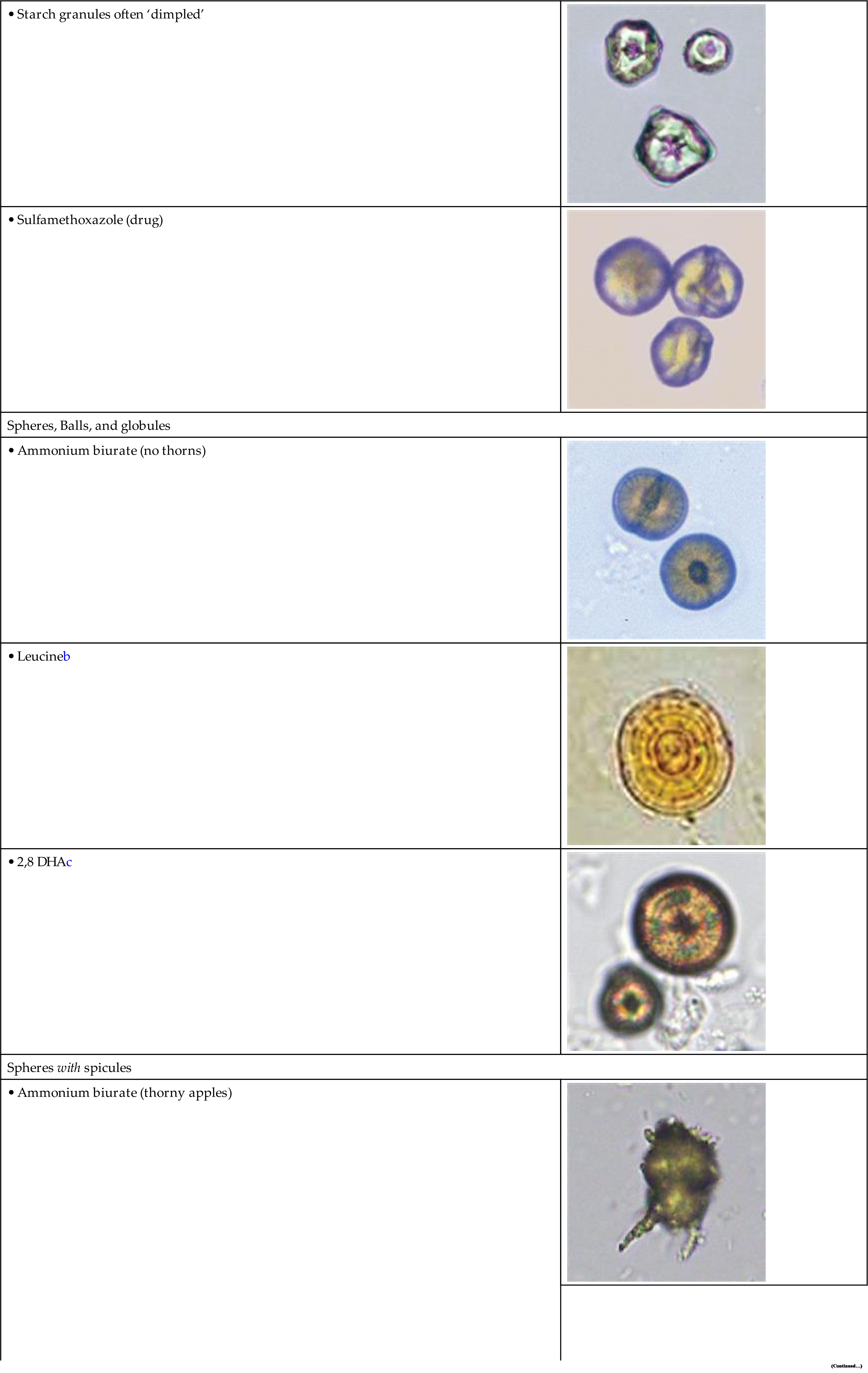

| Polyhedrons (irregular globules) | |

| |

| |

| Spheres, Balls, and globules | |

| |

• Leucineb |

|

• 2,8 DHAc |

|

| Spheres with spicules | |

| |

| |

| |

| |

| |

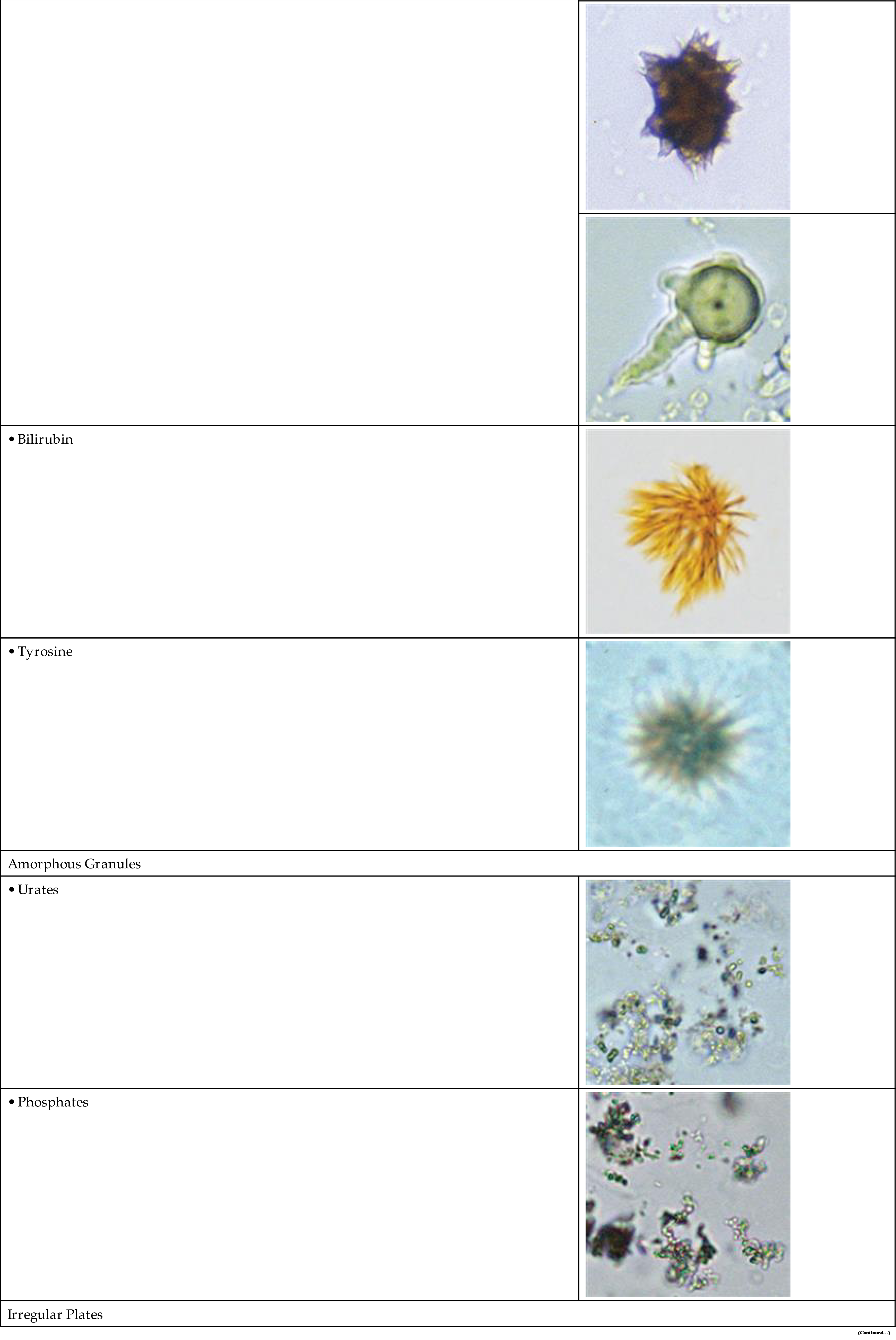

| Amorphous Granules | |

| |

| |

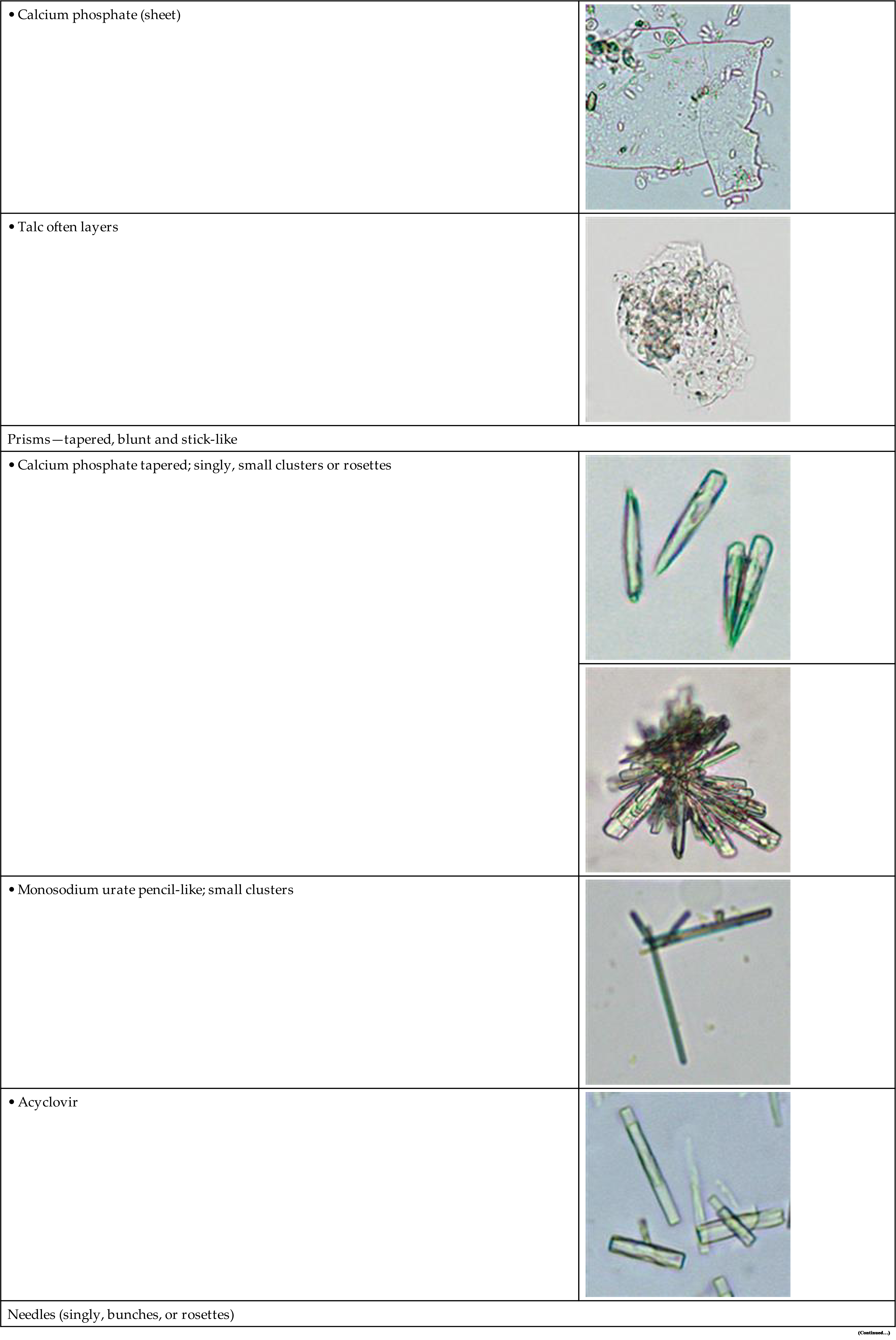

| Irregular Plates | |

| |

| |

| Prisms—tapered, blunt and stick-like | |

| |

| |

| |

| |

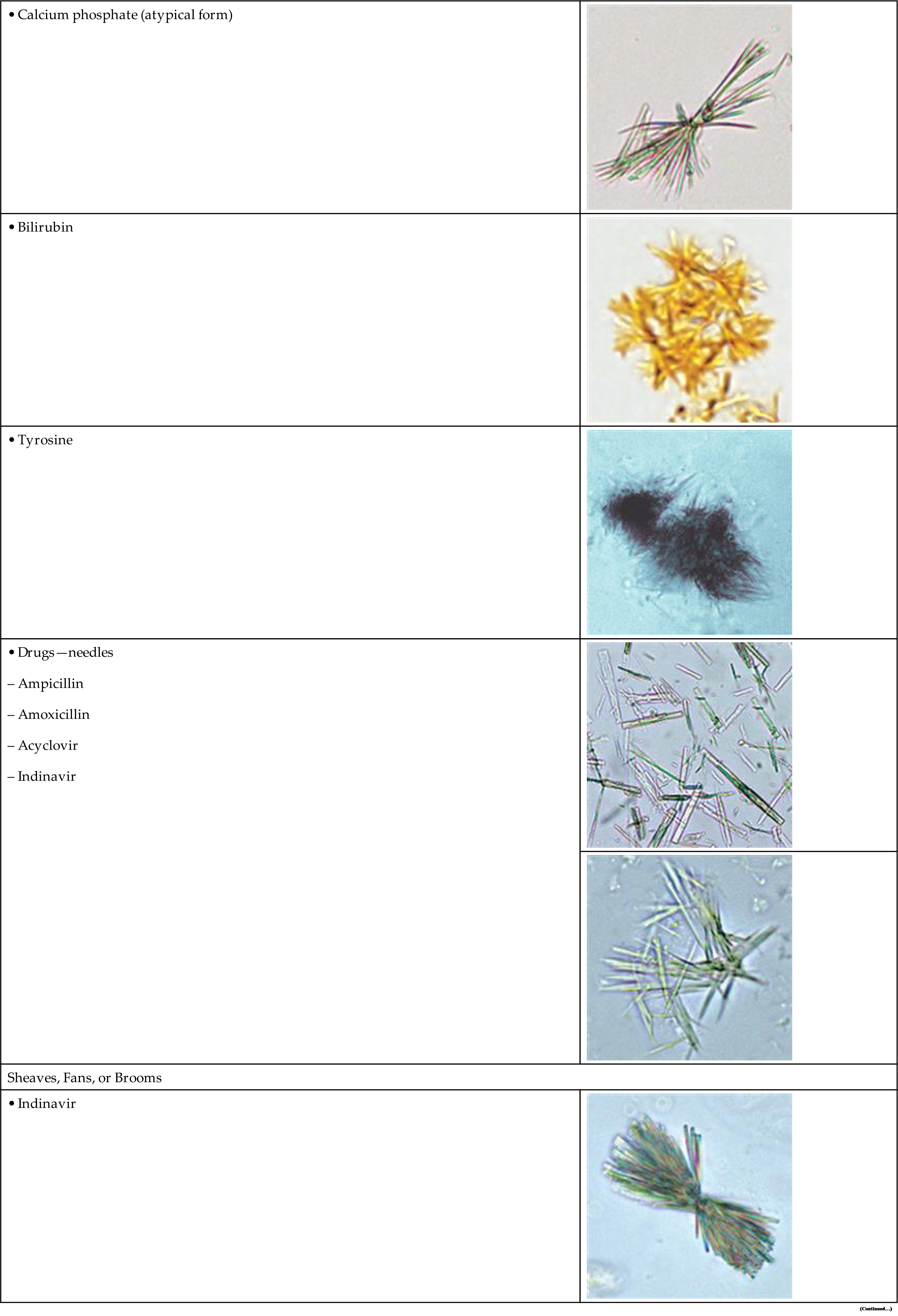

| Needles (singly, bunches, or rosettes) | |

| |

| |

| |

| |

| |

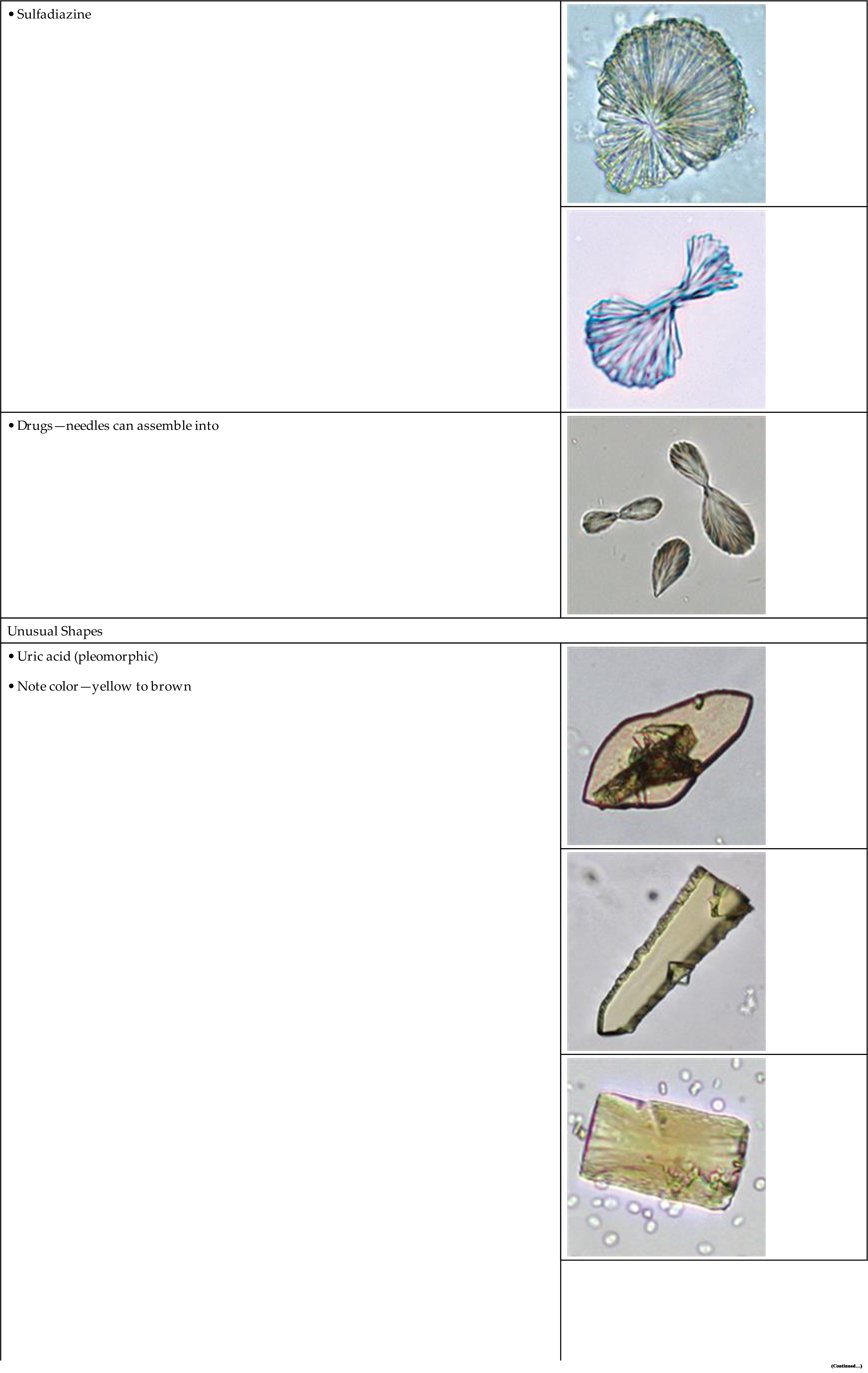

| Sheaves, Fans, or Brooms | |

| |

| |

| |

| |

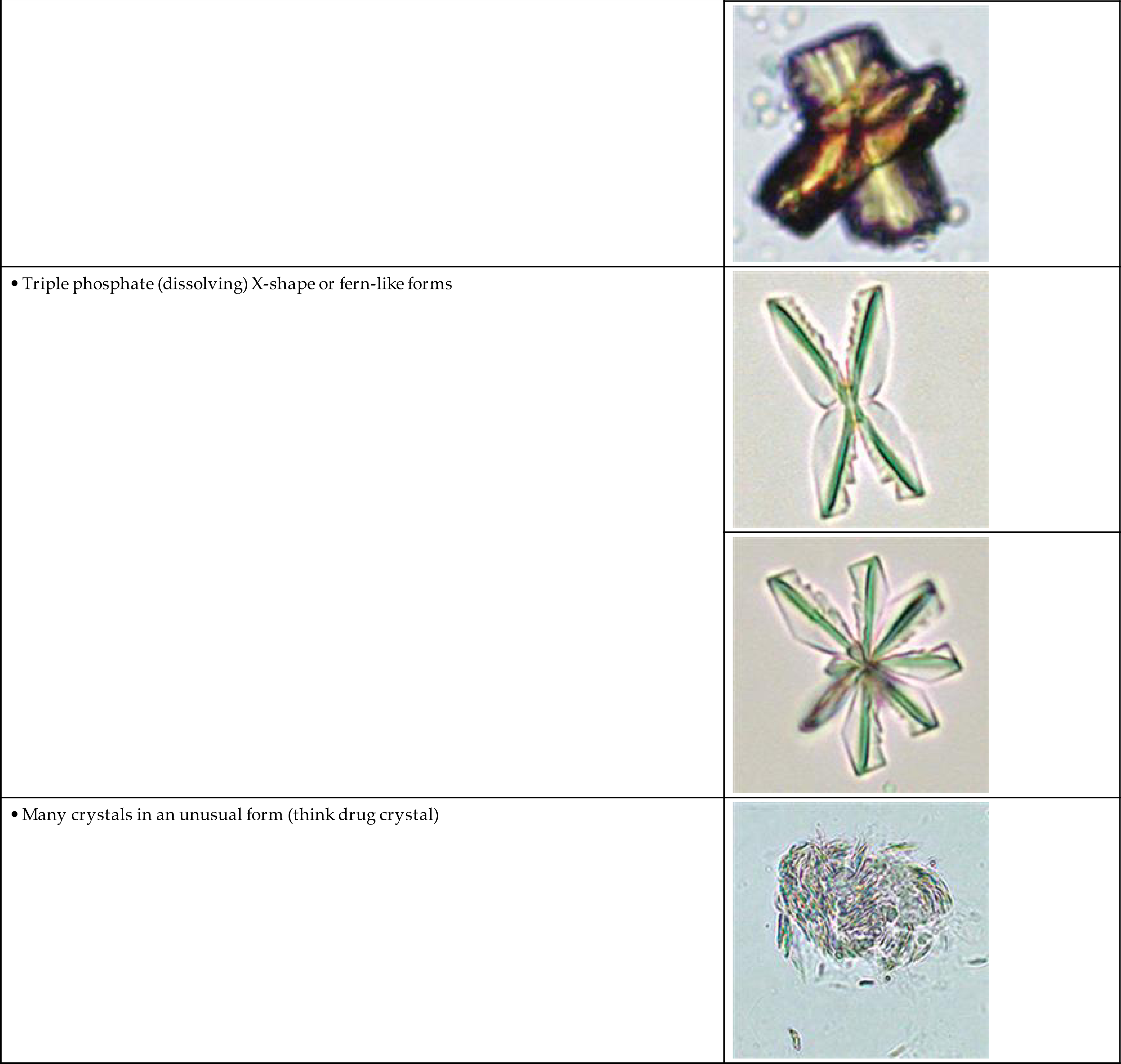

| Unusual Shapes | |

| |

| |

| |

| |

| |

| |

| |

Red text = Acid pH, Blue text = Alkaline pH, Black text = Acid/Alkaline pH

aCourtesy Michel Daudon, Laboratoire des Lithiasis, APHP, Hopital Tenon, Paris, France.

bFrom Fogazzi GB: The urinary sediment, ed 3, Milan, Italy, 2010, Elsevier Srl.

cCourtesy Hrafnhildur Runolfsdottir, Runolfur Palsson, and V. Edvardsson, APRT Deficiency Research Program, Landspitali, The National University Hospital in Reykjavik, Iceland.

dCrystals in each section are listed in order of prevalence, i.e., the most frequently seen are listed first.

Acidic Urine

Amorphous Urates

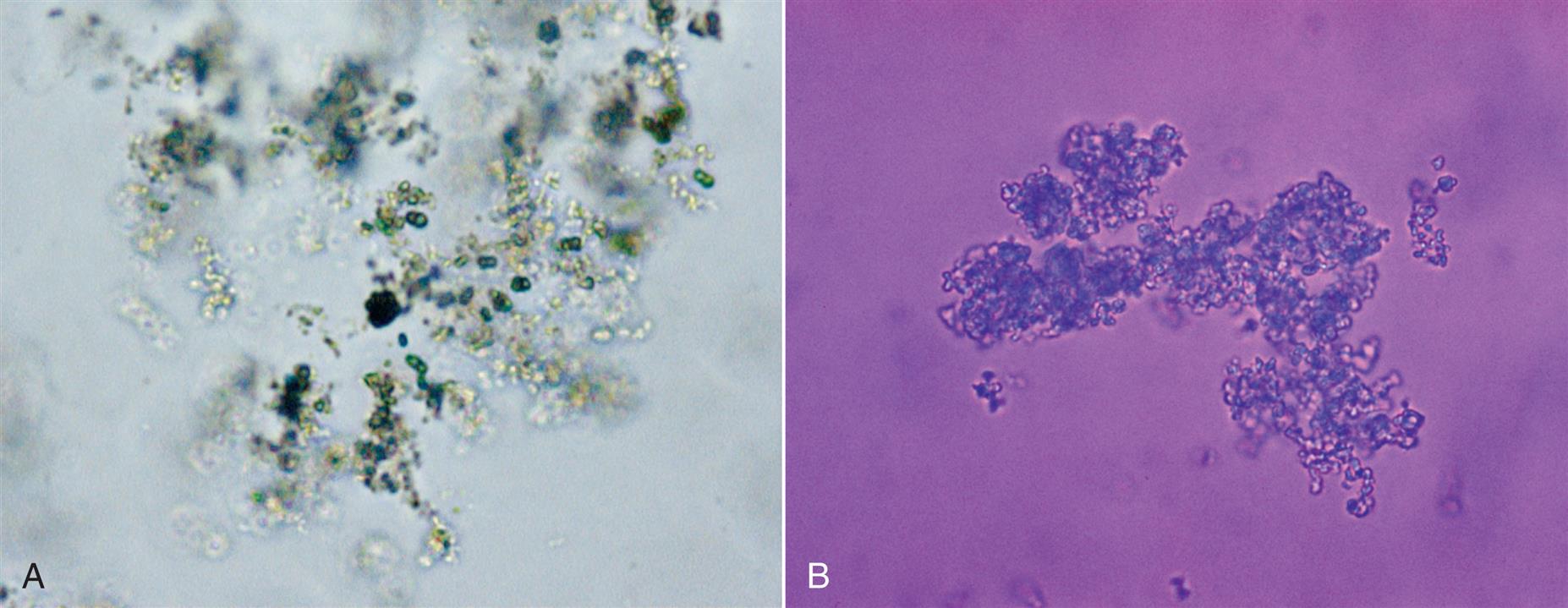

When the urine pH is between 5.7 and 7.0, uric acid exists in its ionized form as a urate salt. Some of these urate salts (sodium, potassium, magnesium, and calcium) can precipitate in amorphous form, that is, without distinct shapes or form. Microscopically, these precipitates appear as small, yellow-brown granules (Fig. 7.78), much like sand, and they can interfere with the visualization of other formed elements present in the urine sediment. Because refrigeration enhances precipitation, performance of the microscopic examination on fresh urine specimens often avoids the formation of amorphous urates. The urinary pigment uroerythrin readily deposits on the surfaces of urate crystals, imparting to them a characteristic pink-orange color. This coloration is apparent macroscopically during the physical examination. Often referred to as “brick dust,” urate crystals indicate that the urine is acidic.

Amorphous urates are present in acidic (or neutral) urine specimens. They can be identified by their solubility in alkali or their dissolution when heated to approximately 60°C. If concentrated acetic acid is added and time allowed, amorphous urates will convert to uric acid crystals. Amorphous urates have no clinical significance and are distinguished from amorphous phosphates on the basis of urine pH, their macroscopic appearance, and their solubility characteristics.

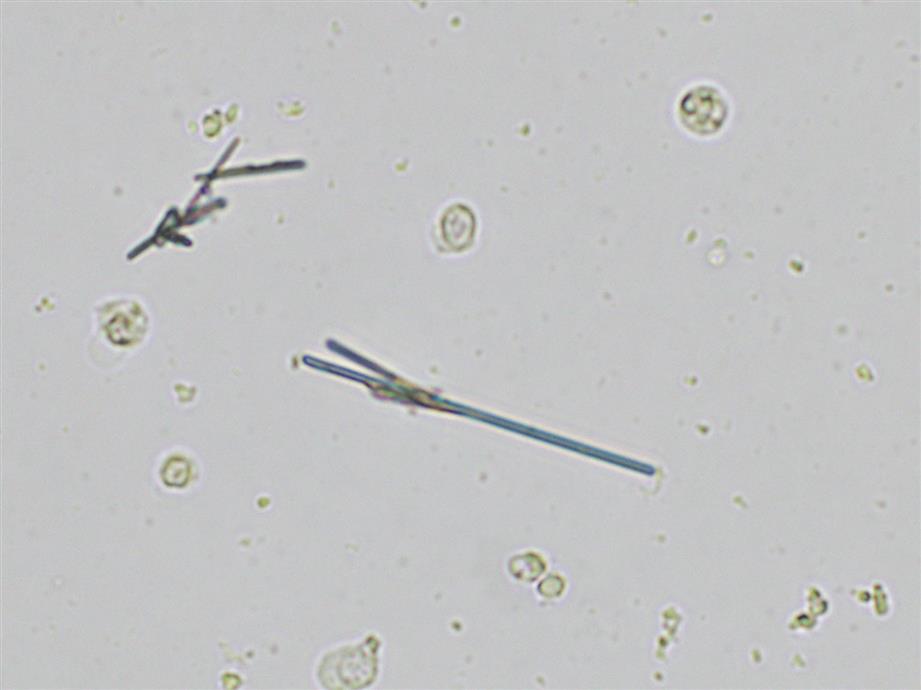

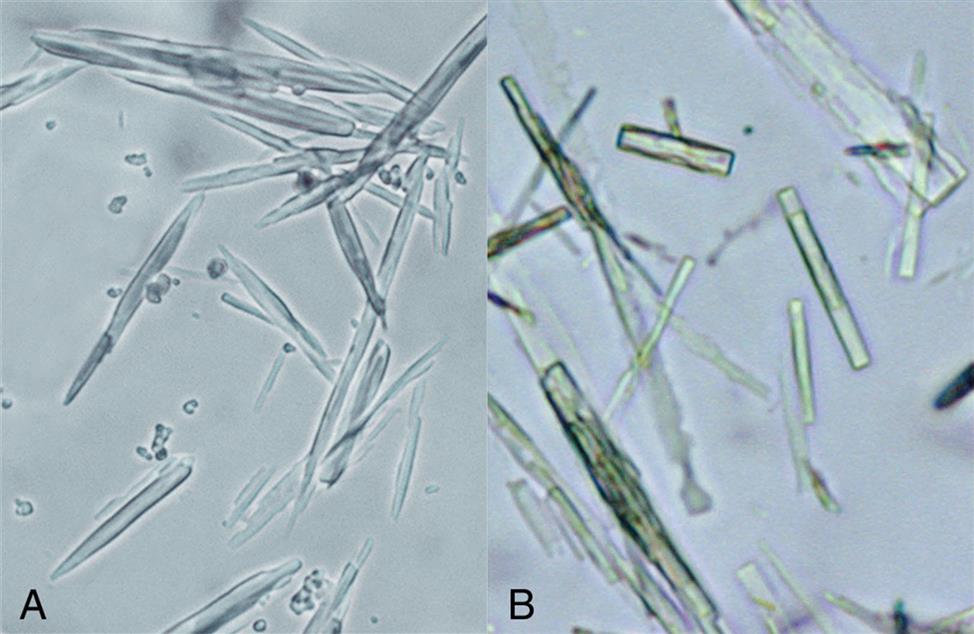

Monosodium Urate

Monosodium urate crystals, a distinct form of a uric acid salt, appear as colorless to light yellow slender, pencil-like prisms (Fig. 7.79). They may be present singly or in small clusters, and their ends are not pointed. In this author’s experience, they appear frequently in urine from infants. Monosodium urate crystals can be present when the urine pH is acid and dissolve at 60°C. They have no clinical significance and usually are reported as “urate crystals.”

Uric Acid

Uric acid crystals occur in many forms; the most common are rhombic or diamond shapes (Figs. 7.80 and 7.81). However, the crystals may appear as cubes, barrels, or bands and may cluster together to form rosettes (Figs. 7.82 and 7.83); they often show layers or laminations on their surfaces (Fig. 7.84). Although they present most often in various forms with four sides, they occasionally have six sides (hexagons), which may require differentiation from colorless cystine crystals. When these hexagons are elongated (Fig. 7.85), they must be differentiated from a similar atypical form of calcium oxalate monohydrate crystals, which can be done using color, pH, and solubility characteristics (see Table 7.11).

Uric acid crystals are yellow to golden-brown, and the intensity of their color varies directly with the thickness of the crystal. As a result, crystals may appear colorless when they are thin or when the urine is low in uroerythrin (a urine pigment). With the use of polarizing microscopy, uric acid crystals exhibit strong birefringence and produce a variety of interference colors.

Uric acid crystals are usually present when the urine pH is less than 5.7. However, when the urine concentration of uric acid is high (≥4 mmol/L), crystals can form at pH 6.0–6.5. Above pH 5.7, uric acid is usually in its ionized form as a urate and will form urate salts (e.g., amorphous urates, sodium urate). Note that uric acid crystals are 17 times less soluble than urate salt crystals; therefore, when urine with uric acid crystals is adjusted to an alkaline pH, the crystals readily dissolve. Similarly, if urine with urate salt crystals is acidified adequately, uric acid crystals form and an interesting feature is that the shape produced is unpredictable.

Uric acid is a normal urine solute that originates from the catabolism of purine nucleosides (adenosine and guanosine from RNA and DNA). Hence uric acid crystals can appear in urine from healthy individuals. Increased amounts of urinary uric acid can be present after the administration of cytotoxic drugs (e.g., chemotherapeutic agents) and with gout. With these conditions, if the urine pH is appropriately acid, large numbers of uric acid crystals can be present.

Calcium Oxalate

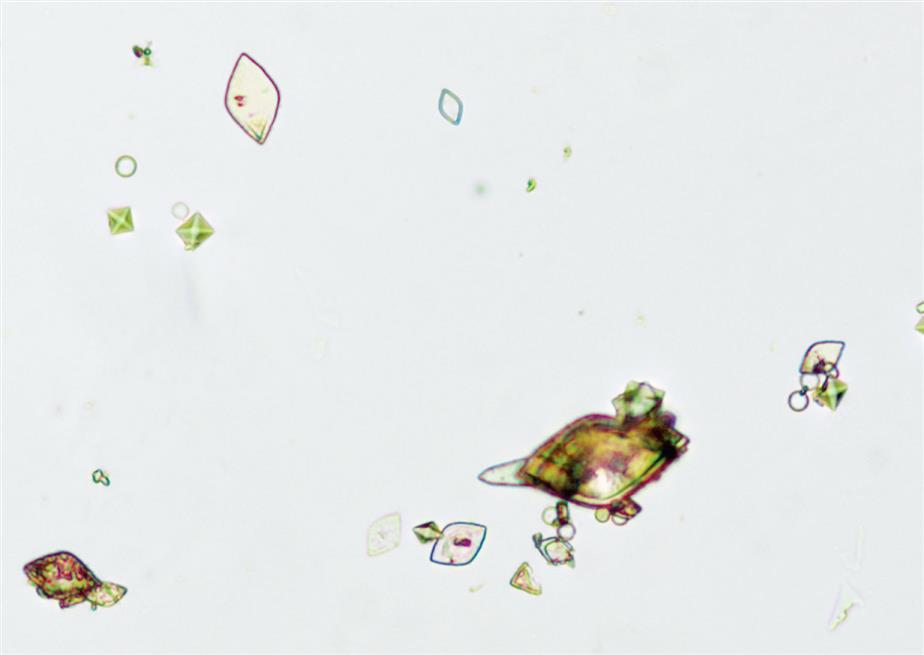

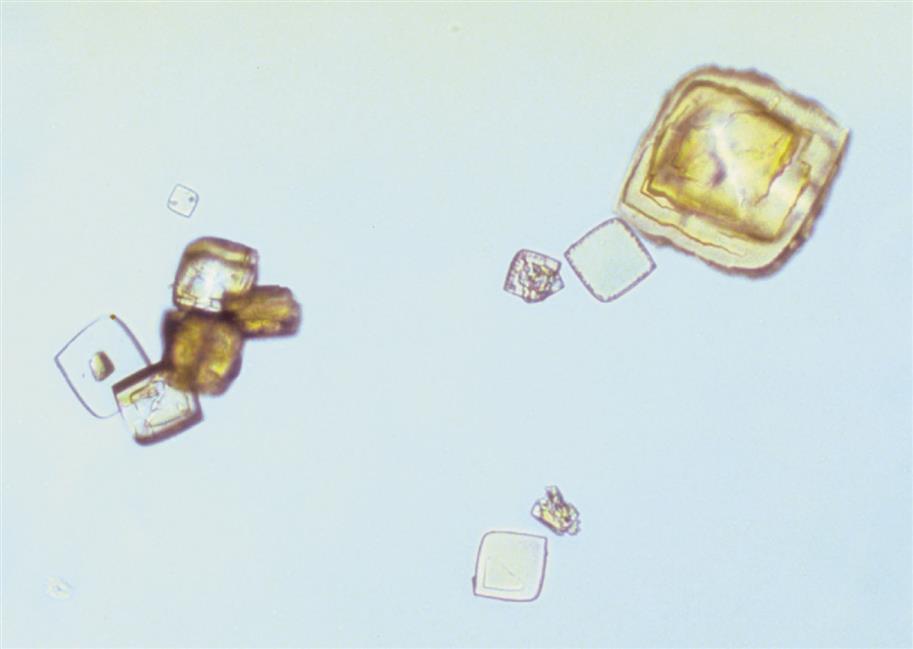

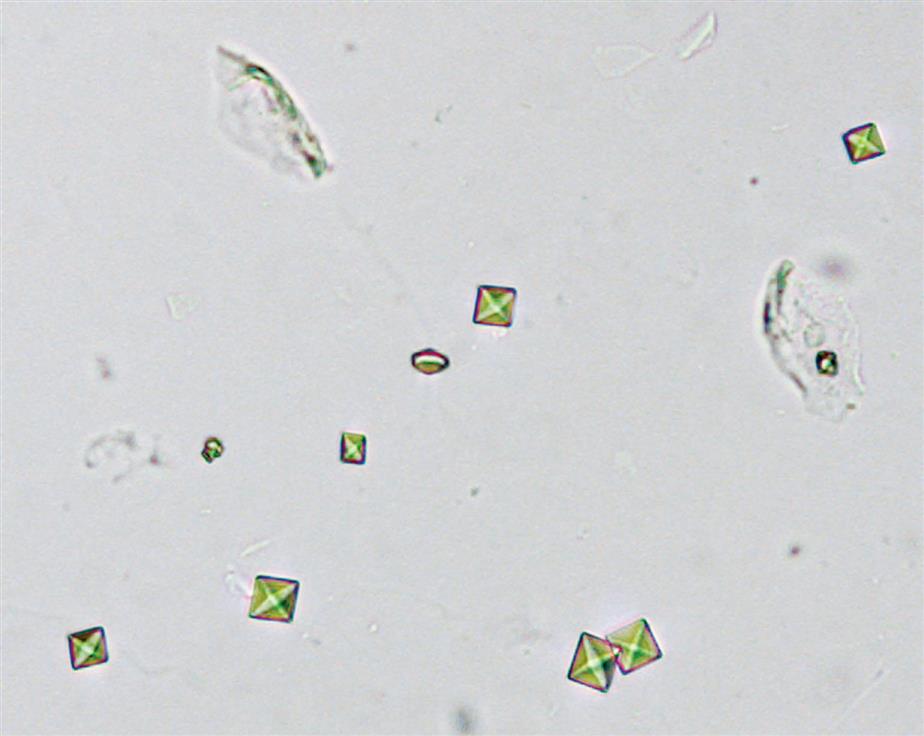

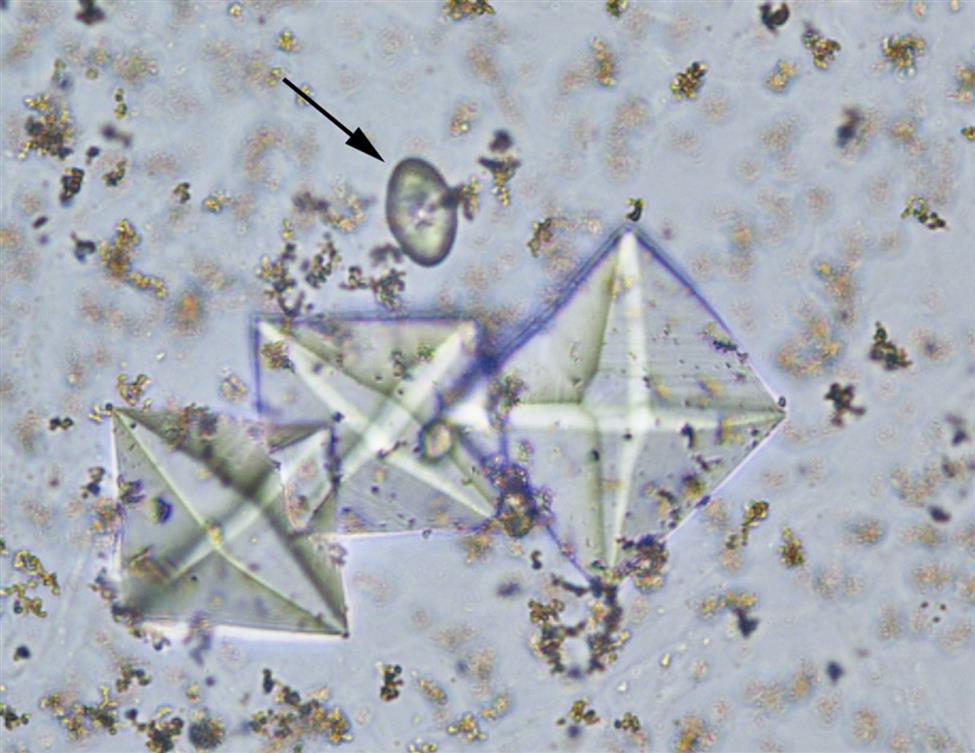

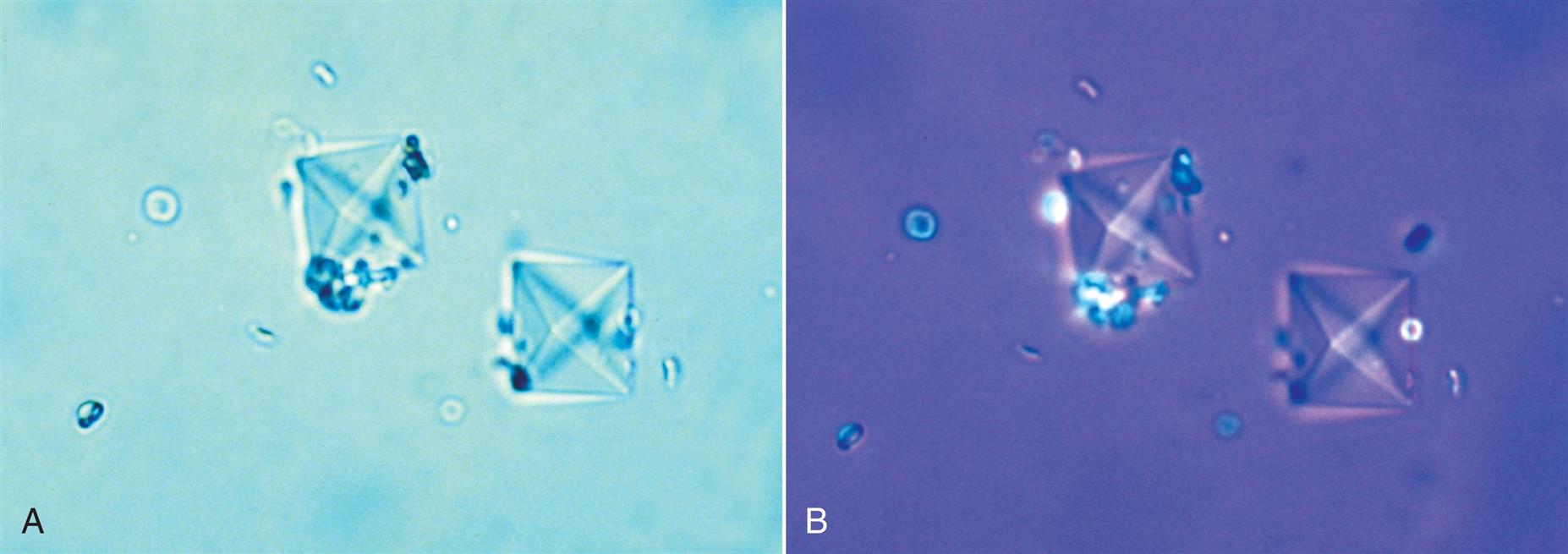

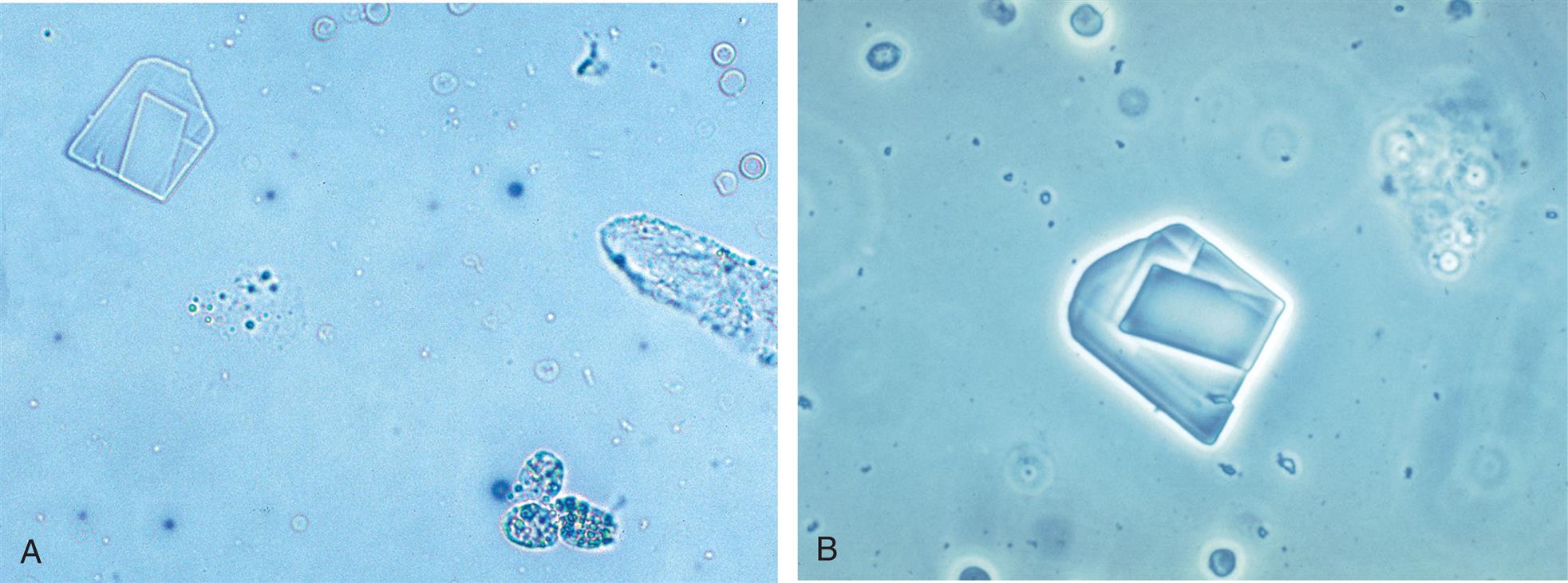

The most common shape of calcium oxalate crystals is the dihydrate form (also known as Weddellite form). It is an eight-sided bi-pyramidal structure (Fig. 7.86) that consists of two square-based pyramids joined at their bases. When viewed from one end, they appear as squares scribed with lines that intersect in the center; hence they are sometimes called ‘envelope’ crystals. A form of dihydrate crystal that is less common is the 12-faced dodecahedral form (Fig. 7.87).

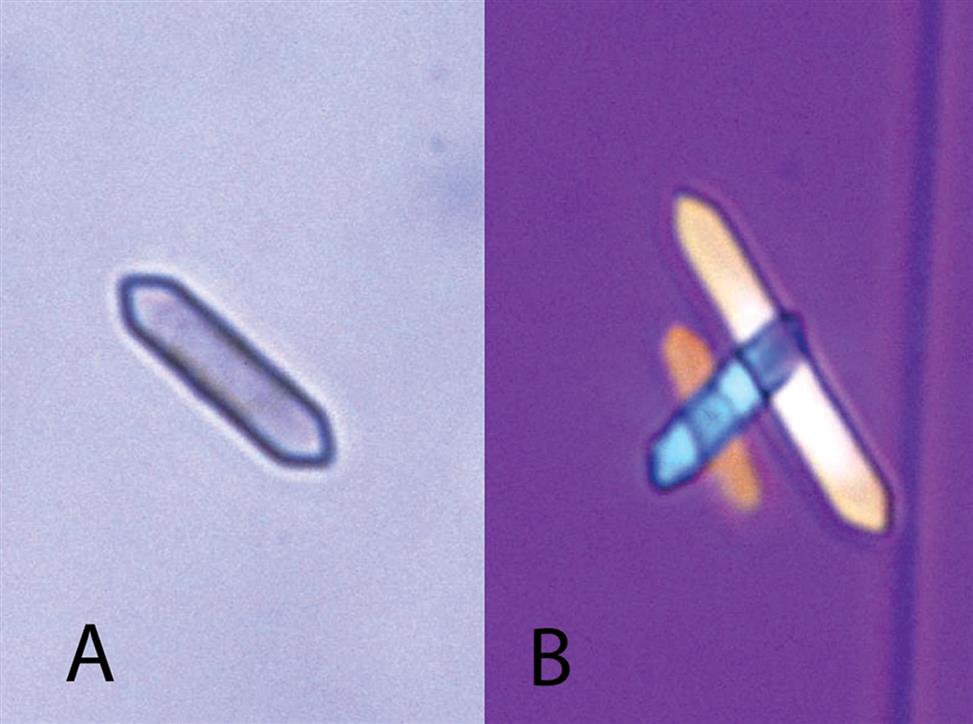

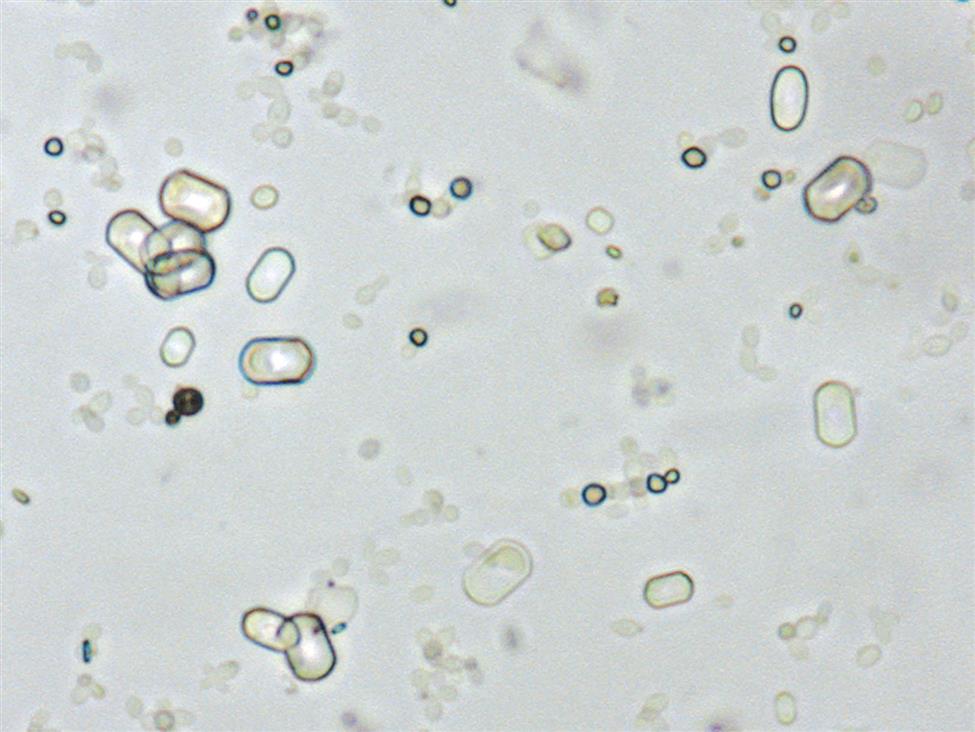

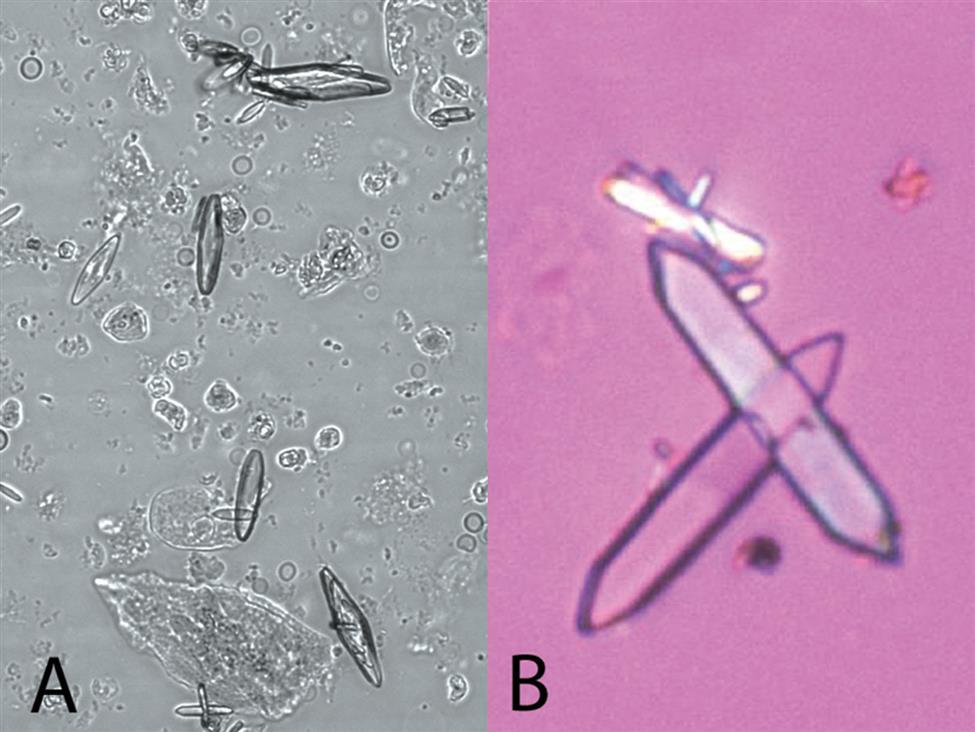

In contrast, the most common form of calcium oxalate monohydrate (Whewellite form) crystals is ovoid or dumbbell-shaped when viewed from the side (Figs. 7.88 and 7.89). These crystals can vary in size, and when small they resemble RBCs but are more refractile. Under polarizing microscopy, monohydrate crystals demonstrate strong birefringence (see Fig. 7.90). Another monohydrate form are atypical ovals that appear flatter (Fig. 7.91). Note that it is common to see calcium oxalate crystals in several forms in a single urine specimen, that is, both monohydrate and dihydrate forms (see Figs. 7.88 and 7.90).

Two additional forms of monohydrate crystals are associated with the ingestion of ethylene glycol (antifreeze), which is an oxalate precursor. One type is the spindle, rhomboid, or elongated diamond form (Fig. 7.92A); the other form is that of elongated (thin) hexagons, which may develop buds or layers from its surface (Fig. 7.92B)26,27. These crystals can appear singly, in clumps, or arranged as rosettes. Note that it can be a challenge to differentiate this elongated hexagon form of calcium oxalate from similar-looking uric acid crystals (compare Fig. 7.92B with Fig. 7.85). When solubility characteristics and birefringence are unable to determine identity, FTIR microspectrometry can be used to reveal a crystals composition.

Calcium oxalate crystals are colorless and can vary significantly in size. Usually the crystals are small and require high-power magnification for identification. On occasion, the crystals may be large enough to be identified under low-power magnification. Calcium oxalate crystals may cluster together and can stick to mucus threads. When this occurs, they may be mistaken for crystal casts by an inexperienced microscopist.

Calcium oxalate crystals are the most frequently observed crystals in human urine, in part because they can form in urine of any pH. Calcium and oxalate are solutes normally found in the urine of healthy individuals. Approximately 50% of the oxalate typically present in urine is derived from ascorbic acid (vitamin C), an oxalate precursor (see Fig. 6.9) or from oxalic acid. Foodstuffs high in oxalic acid or ascorbic acid include vegetables (rhubarb, tomatoes, asparagus, spinach) and citrus fruits. Beverages that are high in oxalic acid include cocoa, tea, coffee, and chocolate. Lastly, ingestion of ethylene glycol (accidental or intentional) is metabolized to oxalic acid (oxalate) for excretion.

As urine forms in the renal tubules, oxalate ions in the ultrafiltrate associate with calcium ions to become calcium oxalate. When the calcium to oxalate ratio in the urine is high, it favors formation of dihydrate crystals.28 With optimal conditions (i.e., solute concentrations, pH, temperature), calcium oxalate precipitates in a crystalline form, which may also be observed with other crystals, predominantly urates or uric acid.

Hippuric Acid

Hippuric acid (N-benzoylglycine) crystals in urine are extremely rare and have no clinical significance. Hippuric acid is a normal solute in urine, reflecting the dietary intake of phenolic compounds, such as fruits, vegetables, coffee, tea, and wine. Dietary phenols are metabolized to benzoic acid, which is then converted to hippuric acid and is excreted in the urine. Note that benzoic acid itself is also used as a food additive, preservative, as well as in making artificial flavors. Despite high urine concentrations reported in the literature, no scholarly articles or studies report the finding of hippuric acid crystals.

Crystals reported as hippuric acid are colorless with the shape of an elongated hexagon similar to atypical forms of calcium oxalate monohydrate and uric acid (see Figs. 7.85 and 7.92). Hippuric acid crystals have historically been associated with ‘glue sniffing’ or inhalant abuse (i.e., the inhaling of toluene-based substances such as glues, paints, or solvents). However, a literature review does not support this association. Despite urinary excretion of very high levels of hippuric acid (e.g., 257 mmol/L), crystalluria is not reported.29 In fact, glue sniffers primarily develop distal renal tubular acidosis without any associated crystalluria. Note that in cases of glue sniffers with renal calculi formation, the stone composition is reported to be predominantly calcium oxalate or calcium phosphate.30,31 Consequently, this author suspects that crystals identified historically as hippuric acid, were actually the elongated hexagon form of monohydrate calcium oxalate. Today, crystal composition can be confirmed using FTIR spectroscopy, which in the days when hippuric acid crystals were reported, this technology was not available or not used. In conclusion, the association of inhalant abuse (glue sniffing) with the formation of hippuric acid crystals is unsubstantiated and should not be propagated. Note that further studies are needed to confirm or refute this view.

Alkaline Urine

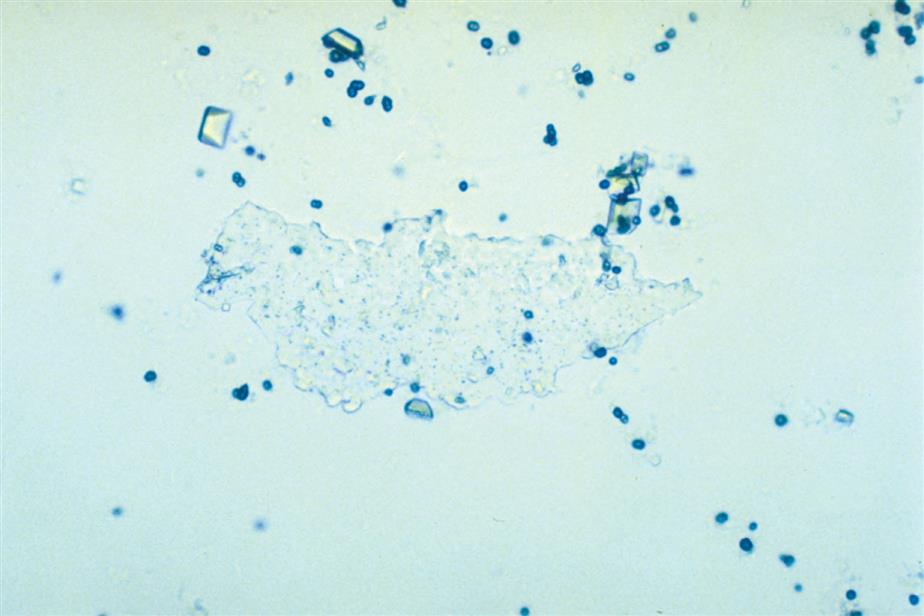

Amorphous Phosphate

Amorphous phosphates are found in alkaline and neutral (pH >6) urine and are microscopically indistinguishable from amorphous urates. This noncrystalline form of phosphates resembles fine, colorless grains of sand in the sediment (Fig. 7.93). Amorphous phosphates are differentiated from amorphous urates on the basis of urine pH, their solubility characteristics, and, to a lesser degree, their macroscopic appearance. Large quantities of amorphous phosphates cause a urine specimen to appear cloudy; the precipitate is white or gray, in contrast to the pink-orange color of amorphous urates. Unlike urates, amorphous phosphates are soluble in acid and do not dissolve when heated to approximately 60°C.

Similar to amorphous urates, amorphous phosphates have no clinical significance and can make the microscopic examination difficult when a large quantity is present. Because refrigeration enhances their deposition, specimens maintained at room temperature and analyzed within 2 hours of collection minimize amorphous phosphate formation.

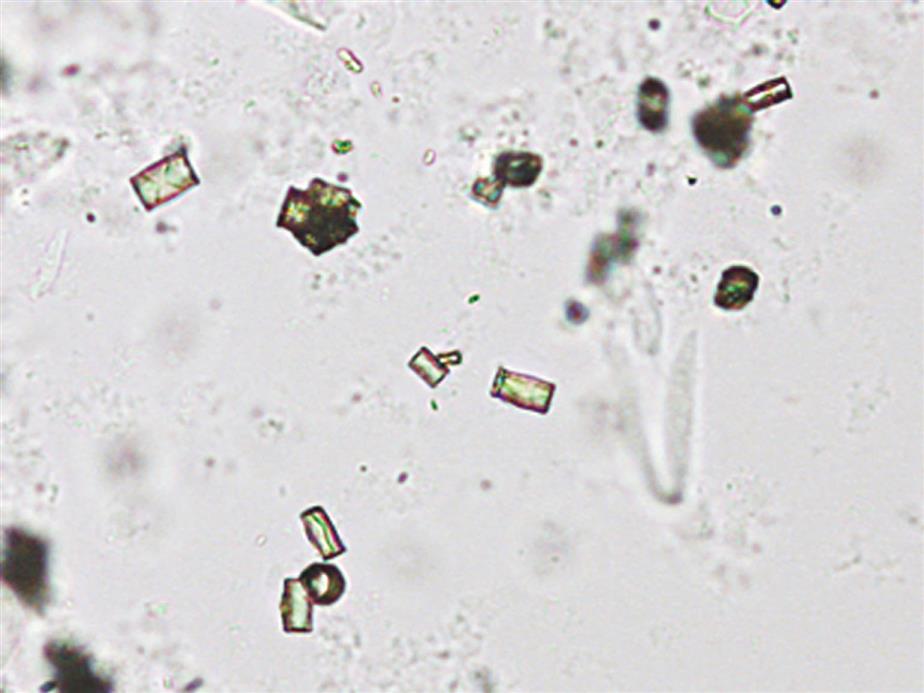

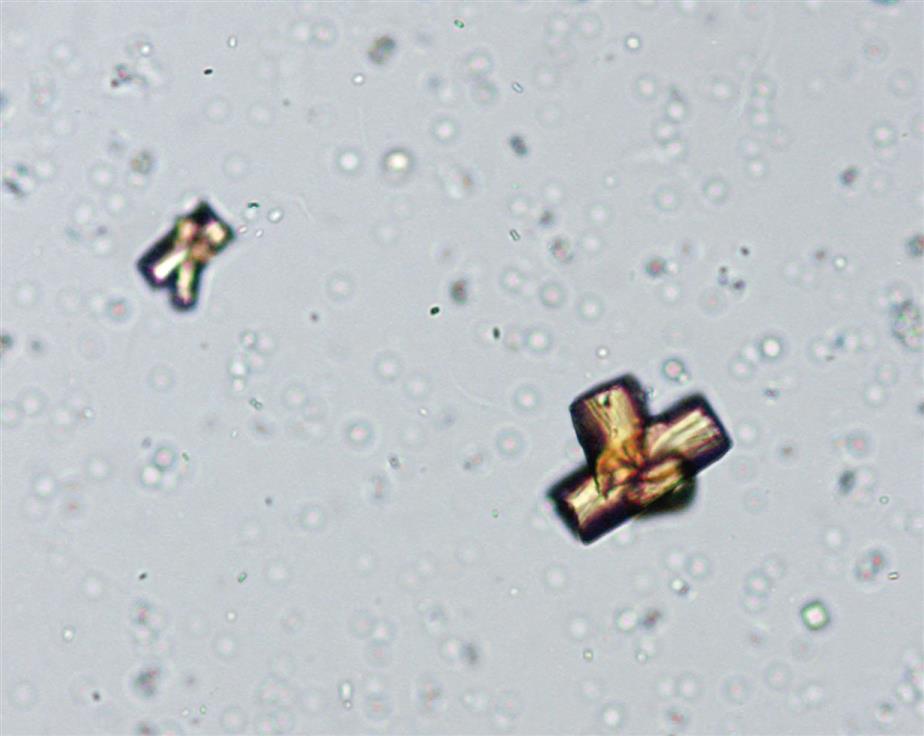

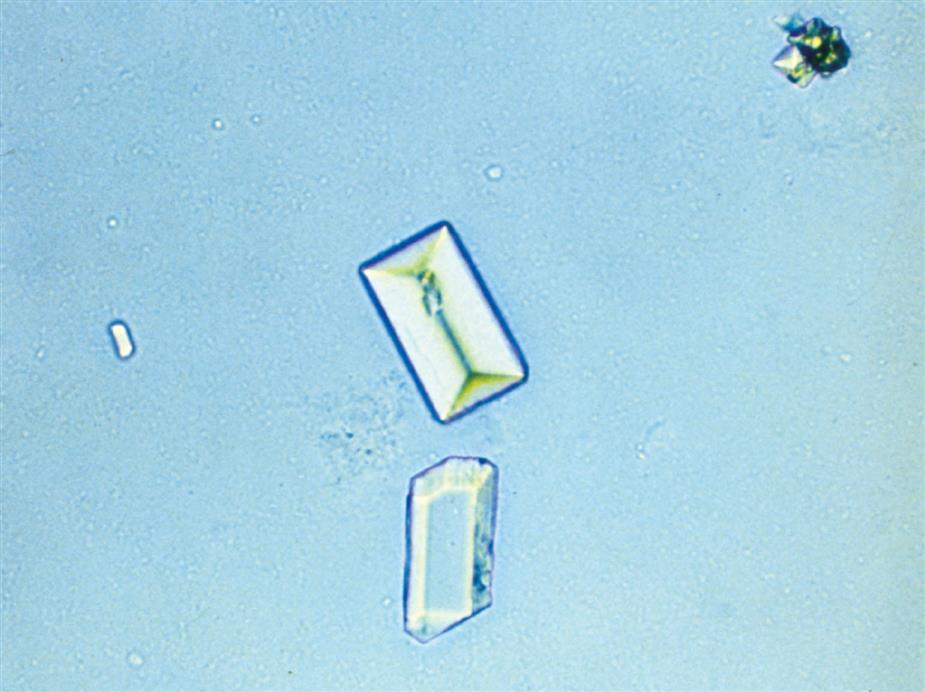

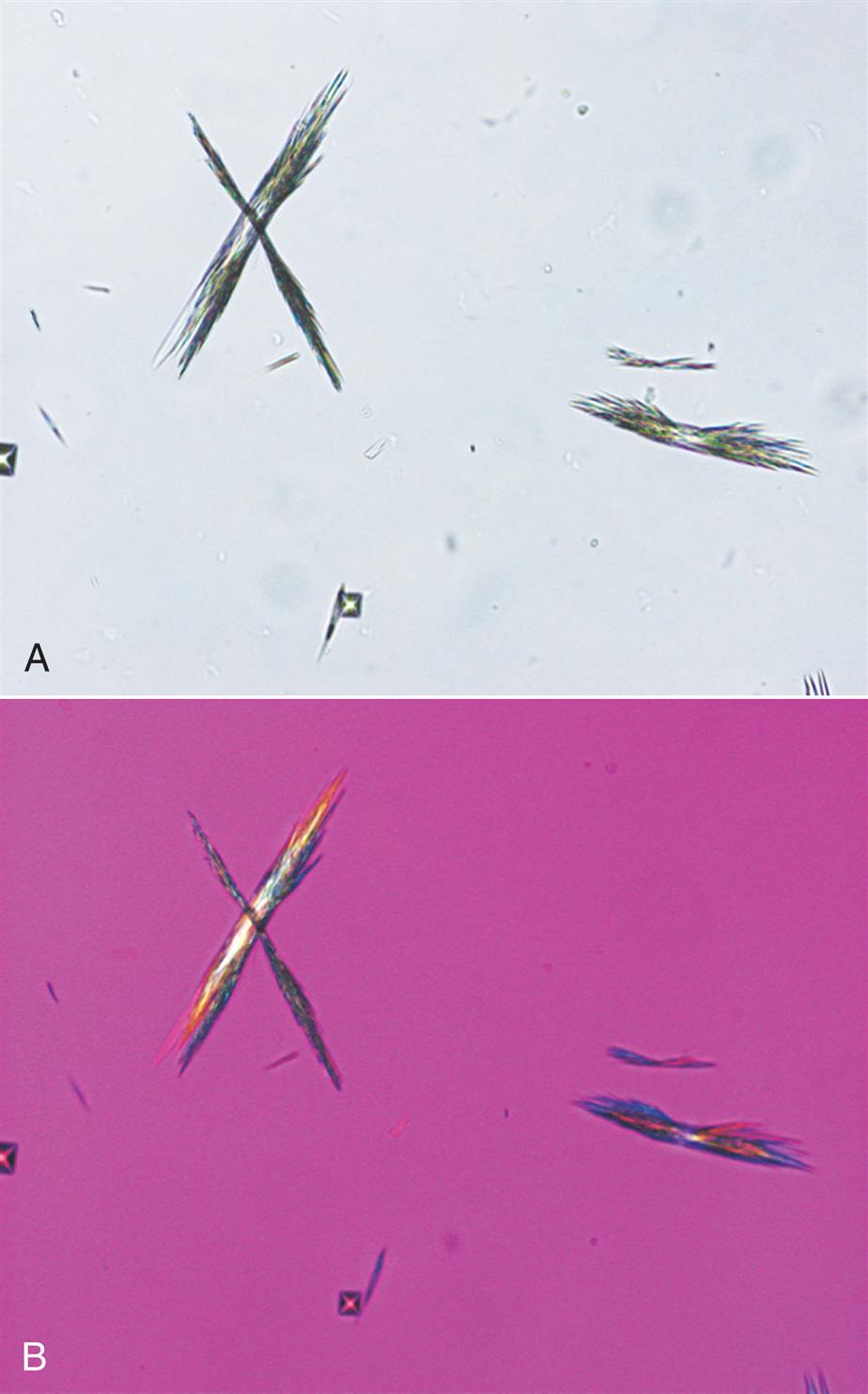

Triple Phosphate

Triple phosphate (NH4MgPO4, ammonium magnesium phosphate) crystals are colorless and appear in several different forms. The most common and characteristic forms are three- to six-sided prisms with oblique terminal surfaces, the latter described as “coffin lids” (Fig. 7.94). Not all crystals are perfectly formed, and their size can vary greatly. Other common shapes include trapezoids, elongated prisms (see Urine Sediment Image Gallery, Fig. 53), and an atypical fern or feathery form. With prolonged storage these crystals can dissolve, taking on a X-shape (see Urine Sediment Image Gallery, Figs. 54 and 55). Under polarizing microscopy, triple phosphate crystals range from weakly to strongly birefringent.

Among the crystals observed in alkaline urine, triple phosphate crystals are common. Note that they can also be present in neutral urine (pH >6). Because ammonium magnesium phosphate is a normal urine solute, triple phosphate crystals can be present in urine from healthy individuals. Triple phosphate crystals have little clinical significance but have been associated with UTIs characterized by an alkaline pH and have been implicated in the formation of renal calculi.

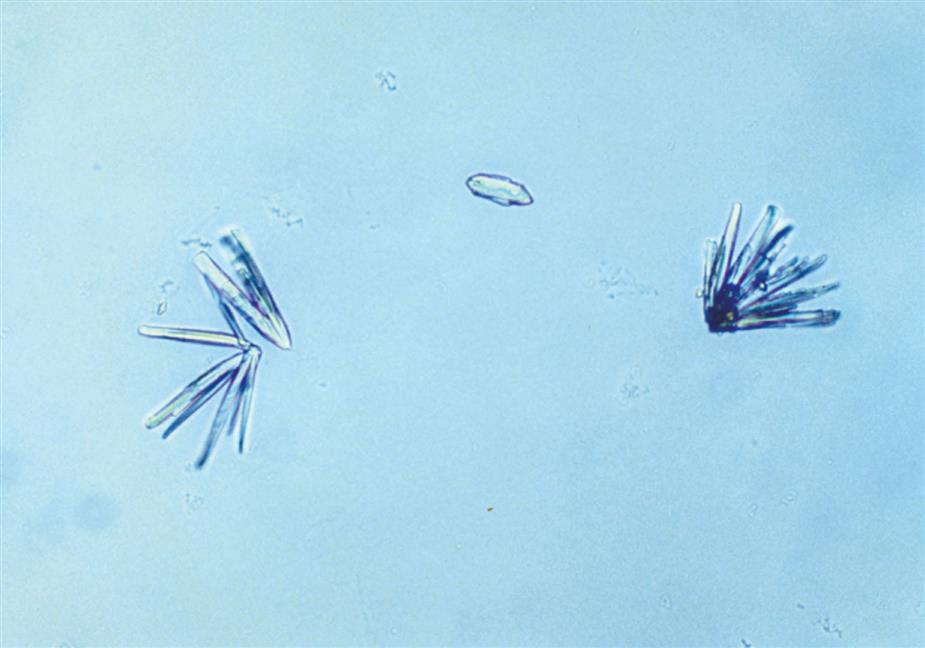

Calcium Phosphate

Calcium phosphate is present in urine as dibasic calcium phosphate (i.e., CaHPO4, calcium monohydrogen phosphate) and as monobasic calcium phosphate (i.e., Ca[H2PO4]2, calcium biphosphate). These similar yet different compounds precipitate out of solution in distinctly different crystalline shapes. Dibasic calcium phosphate crystals, sometimes called stellar phosphates, appear as colorless, slat-like prisms arranged in small groupings or in a rosette pattern (Fig. 7.95). Each prism has one tapered or pointed end, with the other end squared off. Another, less common, form of dibasic calcium phosphate crystals are thin, long needles arranged in bundles or sheaves (Fig. 7.96). In contrast, monobasic calcium phosphate crystals usually appear microscopically as irregular granular sheets (Fig. 7.97) or flat plates that can be large and may even be noticed floating on the top of a urine specimen. These colorless crystalline sheets can resemble large degenerating squamous epithelial cells.

Calcium phosphate crystals are classified as alkaline crystals because they are present in neutral or alkaline urine (pH >6). The calcium phosphate prism forms (dibasic) are weakly birefringent with polarizing microscopy, whereas calcium phosphate plates (monobasic) are not birefringent. Calcium phosphate crystals are common and have no clinical significance.

Ammonium Biurate

Ammonium biurate crystals appear as yellow-brown spheres with striations or irregular creases on the surface (Fig. 7.98). Irregular projections or spicules (thorns) can also be present, giving these crystals a “thorny apple” appearance. They are predominantly seen in alkaline urine (pH >7.5), but can form in neutral urine (pH >6).

Ammonium biurate is a normal urine solute and crystals occur most frequently in urine specimens that have undergone prolonged storage. However, when they precipitate out of solution in fresh urine specimens (e.g., after iatrogenically induced alkalinization) they are clinically significant, because in vivo precipitation can cause renal tubular damage. Their presence most often indicates inadequate hydration of the patient. Therefore when ammonium biurate crystals are encountered in a urine specimen, investigation is required to determine whether (1) the integrity of the urine specimen has been compromised (improper storage) or (2) in vivo formation is taking place.

Ammonium biurate crystals are strongly birefringent and dissolve in acid or on heating to approximately 60°C. Similar to other urate salts (amorphous urates, acid urates), ammonium biurate crystals can be converted to uric acid crystals with the addition of concentrated hydrochloric or acetic acid.

An important note is that ammonium biurate crystals can resemble some forms of sulfonamide drug crystals. One differentiates between them on the basis of urine pH, a sulfonamide confirmatory test, and the solubility characteristics of the crystals.

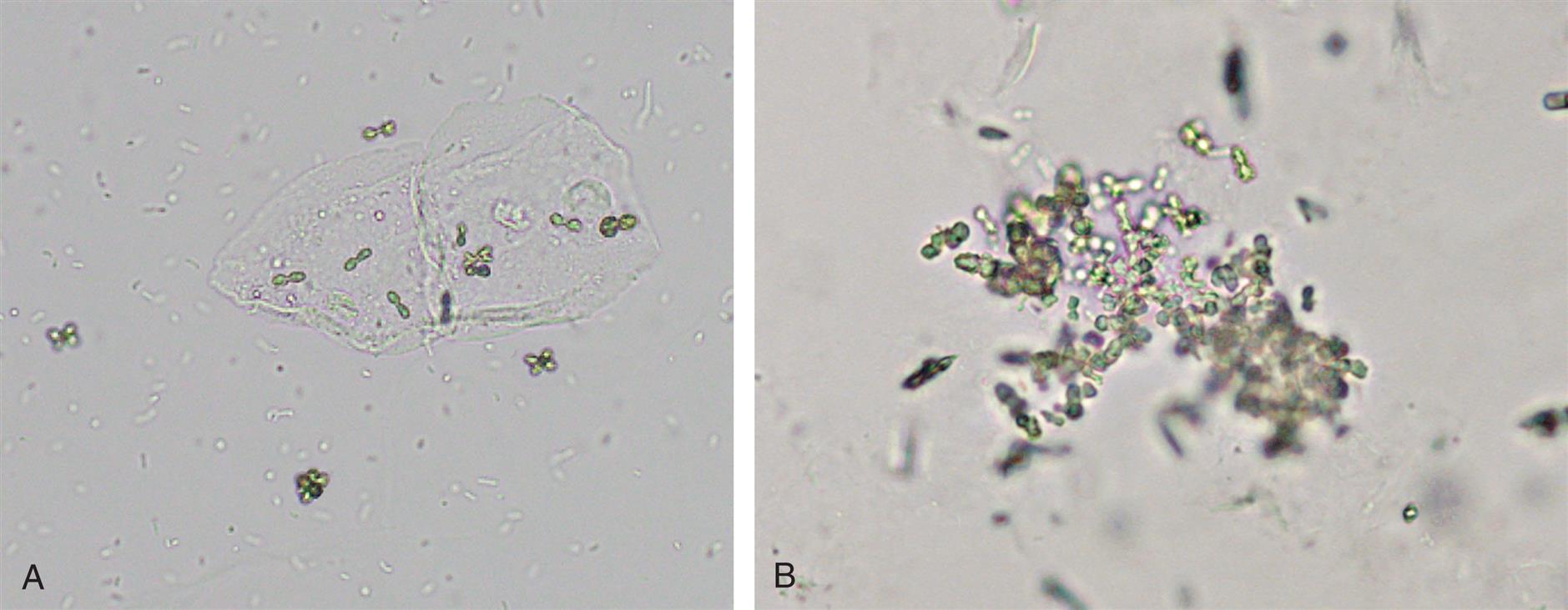

Calcium Carbonate

Calcium carbonate crystals appear as tiny, colorless granular crystals (Fig. 7.99A). Slightly larger than amorphous material, these crystals sometimes are misidentified as bacteria because of their size and occasional rod shape. Under polarizing microscopy, they are strongly birefringent, which aids in differentiating them from bacteria that are not birefringent. Calcium carbonate crystals are usually found in pairs, giving them a dumbbell shape, or as tetrads. They may also be encountered as aggregate masses that are difficult to distinguish from amorphous material (Fig. 7.99B).

Present primarily in alkaline urine (pH >6), calcium carbonate crystals are not found frequently in the urine sediment. Although they have no clinical significance, one can identify calcium carbonate crystals positively through the production of carbon dioxide gas (effervescence) with the addition of acetic acid to the sediment.

Crystals of Metabolic Origin

Bilirubin

The amount of bilirubin in urine can be so great that on refrigeration, its solubility is exceeded and bilirubin crystals precipitate out of solution (Fig. 7.100). Bilirubin crystals usually appear as small clusters of fine needles (20–30 μm in diameter), but granules and plates have been reported. Always characteristically golden yellow, these crystals indicate the presence of large amounts of bilirubin in the urine. Bilirubin crystals are confirmed by correlation with the chemical examination—that is, the crystals can be present only if the chemical screen for bilirubin is positive.

Bilirubin crystals only form in an acidic urine. They dissolve when alkali or strong acids are added. They are classified as abnormal crystals because bilirubinuria indicates a metabolic disease process. However, because these crystals form in the urine after excretion and cooling (i.e., storage), they are not frequently observed and they are not usually reported.

Cystine

Cystine crystals appear as colorless, hexagonal plates with sides that are not always even (Fig. 7.101). These clear, refractile crystals are often laminated or layered and tend to clump.

Cystine crystals are clinically significant and indicate disease—that is, hereditary cystinosis or cystinuria. These crystals tend to deposit within the tubules as calculi, resulting in renal damage; therefore, proper identification is important. Thin, hexagonal uric acid crystals can resemble cystine; therefore, a confirmatory test should be performed before cystine crystals are reported. The chemical confirmatory test for cystine is based on the cyanide-nitroprusside reaction. Sodium cyanide reduces cystine to cysteine, and the free sulfhydryl groups subsequently react with nitroprusside to form a characteristic red-purple color. For procedural details and performance, see Appendix E, “Manual and Historic Methods of Interest.”

Cystine crystals are present primarily in acid urine (pH <6) but can be present in urine up to a pH of ~ 8.3 (pKa of cystine). In vivo, the solubility of cystine rises exponentially with urine pH (i.e., it is almost four times more soluble at pH 8 than at pH 5).29 They dissolve in alkali or hydrochloric acid (pH <2) and are weakly to moderately birefringent depending on the thickness or layering of the crystals. In summary, when cystine excretion is excessive and crystals form in the urine, it is abnormal and indicates a disease process.

Tyrosine and Leucine

Tyrosine crystals appear as fine, delicate needles that are colorless or yellow (Fig. 7.102). They frequently aggregate to form clusters, bundles, or sheaves but may also appear singly or in small groups.

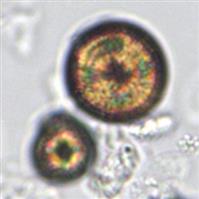

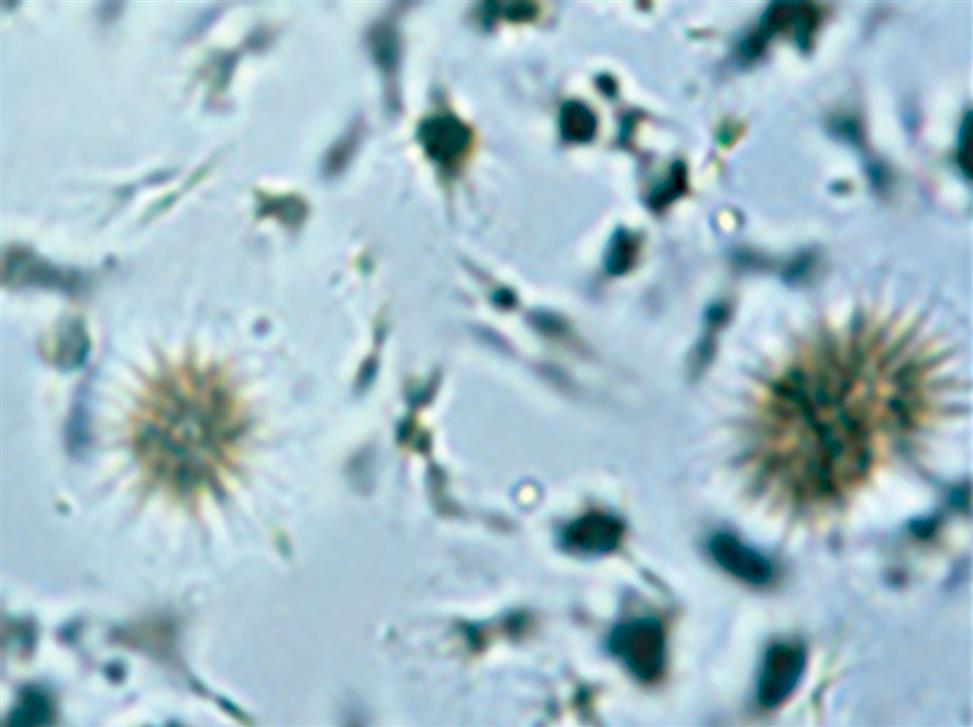

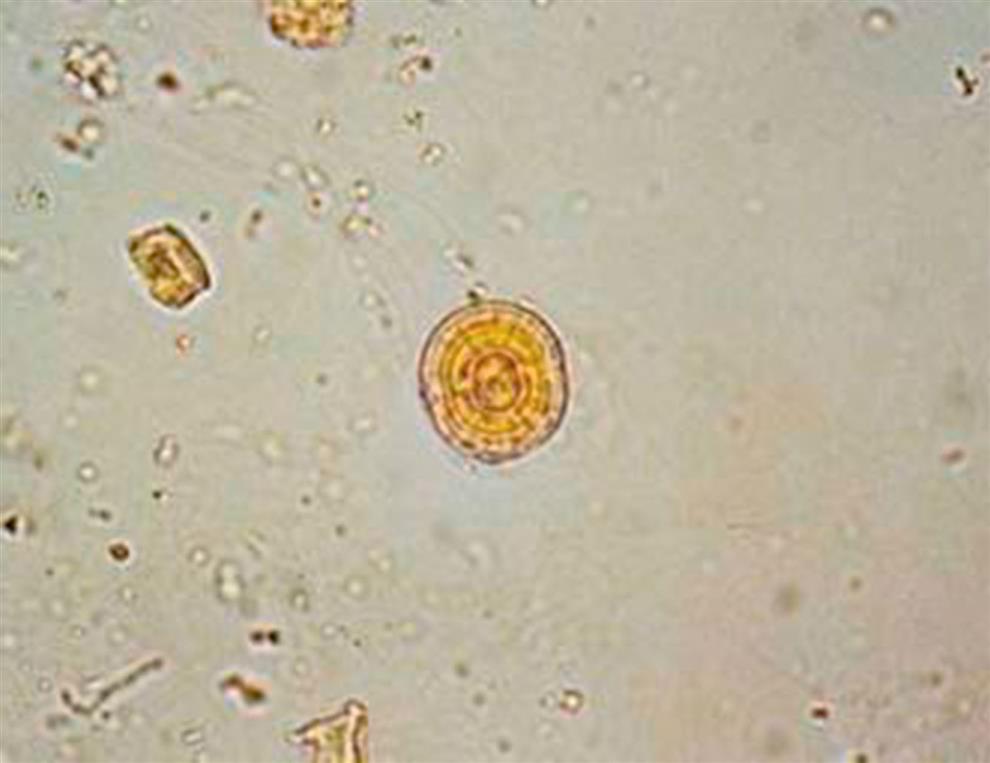

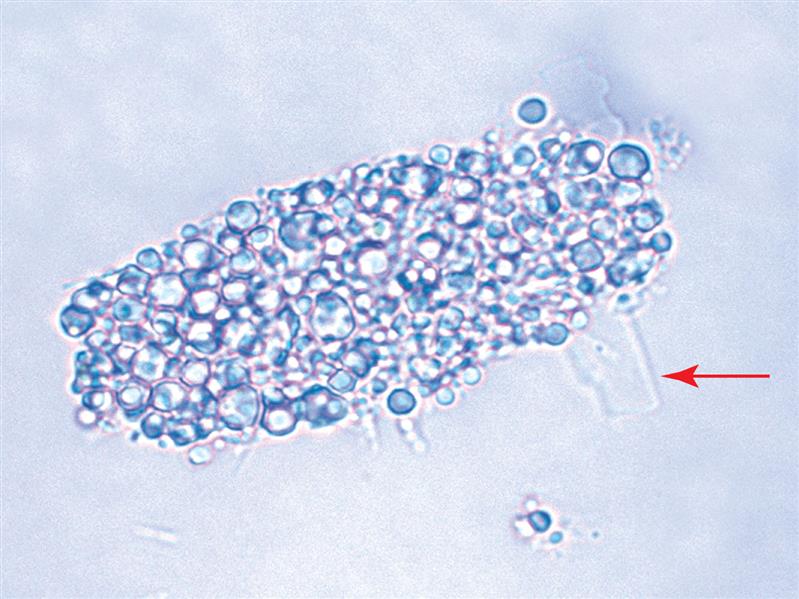

Leucine crystals are highly refractile, yellow to brown spheres. They have concentric circles on their surface and may also have radial striations (Fig. 7.103). They are birefringent under polarized microscopy, producing a pseudo-Maltese cross pattern (i.e., pattern with unequal or asymmetric quadrants, see Chapter 18, Table 18.1).

Tyrosine and leucine crystals form in acid urine (pH <6) and dissolve in alkali. They are rarely seen today because of the rapid turnaround time for a urinalysis and because they require refrigeration to force them out of solution. Of the two, tyrosine crystals are found more often because it is less soluble than leucine. Sometimes leucine crystals can be forced out of solution by the addition of alcohol to tyrosine-containing urines.

These amino acid crystals are abnormal and are rarely seen. They may be present in the urine of patients with overflow aminoacidurias—rare inherited metabolic disorders. In these conditions, the concentration of tyrosine and leucine in the blood is high (aminoacidemia), resulting in increased renal excretion. Although rare, these crystals have also been observed in the urine of patients with severe liver disease.

Be aware that there are other substances that can form crystals that look similar to those formed by tyrosine or leucine. For example, leucine look-alikes include some medication crystals and 2,8-dihydroxyadenine (DHA) crystals (Fig. 7.104), which are present in urine from individuals with the rare inborn error of metabolism known as adenine phosphoribosyltransferase (APRT) deficiency.33 Most identified cases of APRT have been in Japan but cases have also been identified in Iceland and France.33

Tyrosine look-alikes include the slender needle crystals of medications such as indinavir, acyclovir, amoxicillin, and ampicillin. Therefore, it is important to review patient diagnosis, history, and medications and to confirm crystals as tyrosine or leucine before they are reported. Techniques available to specifically identify them include chromatographic methods, FTIR and ultraviolet spectrometry.

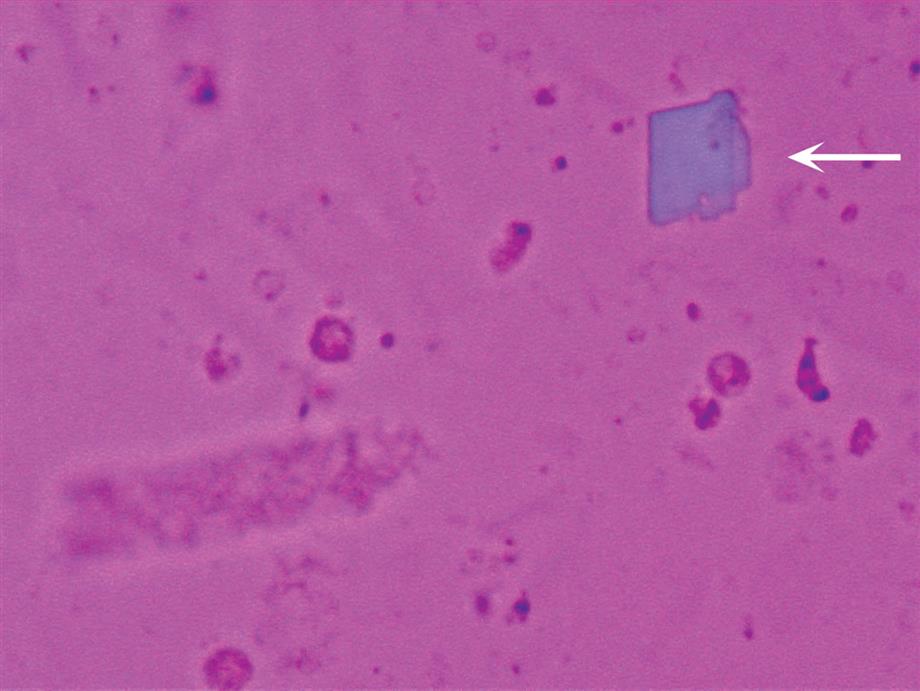

Cholesterol

Cholesterol crystals appear as clear, thin parallelogram-shaped plates (Fig. 7.105). Their shape and size can vary, they are often layered, and they may have notched corners (Figs. 7.106 and 7.107). Under polarizing microscopy, cholesterol crystals are only weakly birefringent and colorless. When a red compensator plate is used, their birefringence is weak and monochromatic (Fig. 7.106). Cholesterol crystals are predominantly in acid urine (pH <6) but can be present in neutral urine (pH 6–7.5). Because of their organic composition, they are soluble in chloroform and ether.

Cholesterol crystal formation occurs in vitro, that is, the crystals are induced out of solution by the cooling of urine after collection and storage. Therefore in some institutions, these crystals are not reported. Instead, lipiduria or chyluria is documented in the urinalysis report by the enumeration and reporting of oval fat bodies, free-floating fat, and fatty casts.

When observed in urine sediment, cholesterol crystals indicate large amounts of cholesterol in the urine and that ideal conditions have promoted supersaturation and its precipitation. Note that cholesterol is a large molecule; if it is able to cross the glomerular filtration barrier to be present in urine so will protein—particularly albumin because of its high plasma concentration. Consequently, when cholesterol is suspected in urine, review the chemical result for protein. It should be positive; the amount present is variable (trace to large) depending on hydration but is most often high (>300 mg/dL). Other evidence of lipids, such as free-floating fat droplets, fatty casts, or oval fat bodies should also accompany these crystals. Upon urine cooling or storage, cholesterol crystals protruding from oval fat bodies or fatty casts can be observed (see Fig. 7.107).

Cholesterol crystals can be seen with the nephrotic syndrome, polycystic kidney disease, lipoid nephrosis, and in conditions resulting in chyluria—the rupture of lymphatic vessels into the renal tubules due to tumors (neoplasms) or parasites (filariasis).

One substance that forms crystals similar to cholesterol is ionic radiographic media (ionic x-ray dye). Although this media is no longer used in the United States, it may be used elsewhere and is discussed briefly in the next section, “Crystals of Iatrogenic Origin.”

Crystals of Iatrogenic Origin

Iatrogenic substances are those that are not native to the human body. In other words, the substance is taken into the body by ingestion, absorption through skin or mucus membranes, inhalation, or by intravenous administration. In a clinical setting, the source of iatrogenic substances found in urine can be categorized into two sources: 1) imaging procedures or 2) drugs. In the following discussion, ionic radiographic media crystals are reviewed and summarized in Table 7.12 with abnormal crystals. Drugs associated with crystalluria are discussed briefly and their characteristics summarized in Table 7.13.

Radiographic Contrast Media

In x-ray procedures, such as computed tomography (CT or CAT) scans, angiography, and pyelograms, radiographic contrast media are used. This media is removed from the body by the kidneys and excreted in the urine. Radiographic contrast media are derivatives of triiodobenzene; the iodine provides the opacity needed for visualization by x-ray. These media can be divided into two categories: ionic and nonionic agents. The nonionic media, such as iodixanol (Visipaque), iohexal (Omnipaque), and iopamidol (Isovue), are preferred because they do not precipitate in vivo or in vitro (in excreted urine) and therefore do not affect the microscopic examination of urine sediment. In contrast, the ionic media are water soluble, dissociating into anions and cations that can precipitate in a crystalline form in the urinary tract or excreted urine. Ionic radiographic media are water-soluble derivatives of triiodobenzene (anion) with either meglumine (cation) or sodium (cation) or a mixture of these two cations. They are known by numerous product names such as diatrizoate (Hypaque, Renografin, Cystografin), metrizoate (Isopaque), and iothalamate (Conray). Note that in the United States, these ionic agents are no longer commercially available because of side effects and the high incidence of contrast-induced nephropathy due to in vivo crystal formation.

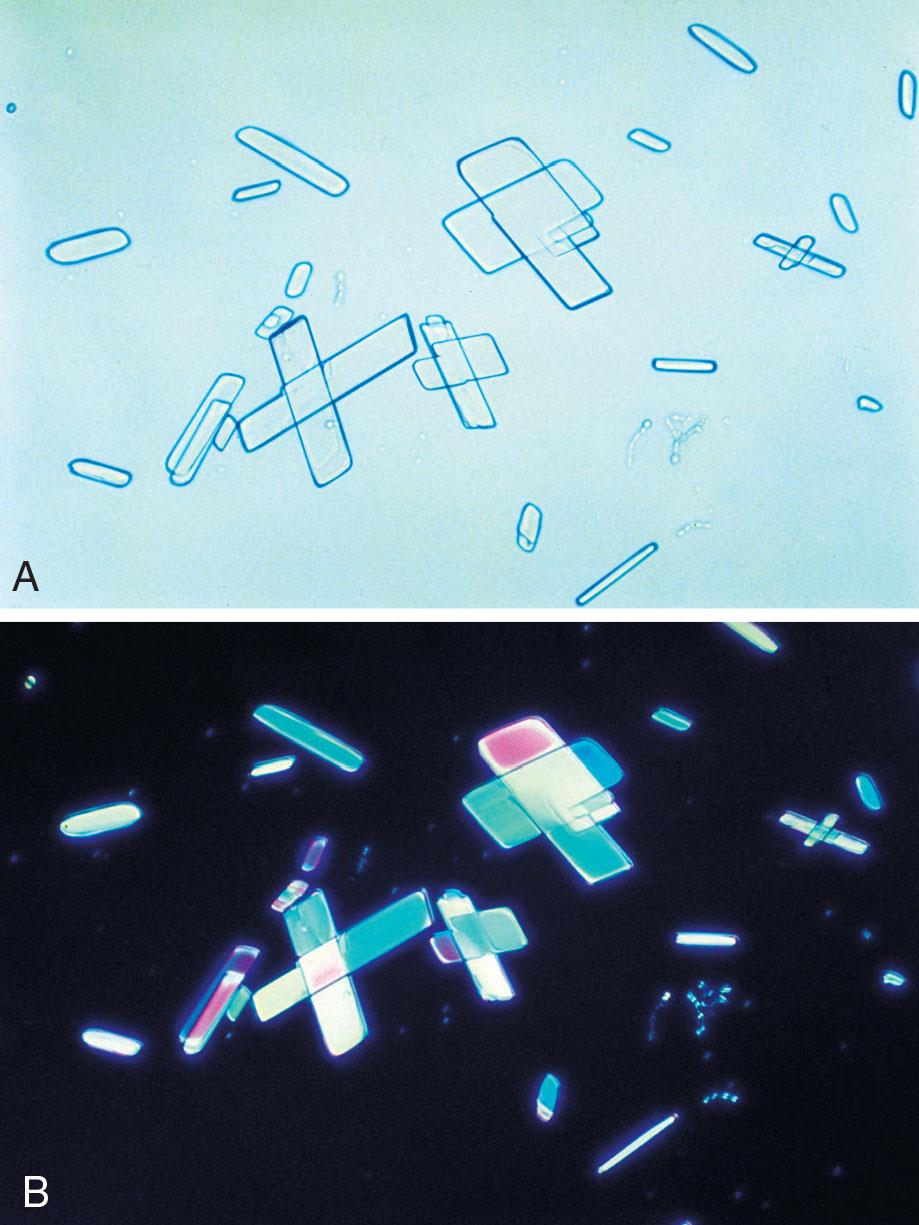

When ‘ionic’ radiographic media is used and urine is collected for a urinalysis before sufficient time has passed after a radiographic procedure, the media can precipitate out of solution. The media crystals form in acid urine as layered parallelogram-shaped crystals that are morphologically similar to and need to be differentiated from cholesterol crystals (compare Figs. 7.105 and 7.108A). Media crystals usually do not have notched corners, which can be seen on cholesterol crystals (see Figs. 7.106 and 7.107). Features that aid in specifically identifying media crystals include: (1) their strong polychromatic birefringence with polarizing microscopy (compare Figs. 7.106 and 7.108B); (2) the high urine specific gravity (by density measurements), which usually exceeds physiologically possible values (i.e., >1.040); (3) the large number of crystals usually present; and (4) the lack of significant proteinuria and lipiduria.

Clearance of radiographic media from the body is highly variable due to the dosage given and the patient’s renal function. The greatest excretion occurs during the first 24 hours, but excretion can persist as late as 3 days.34 If a sulfosalicylic acid precipitation test for protein is performed, it will produce a false-positive result because the media precipitates upon acid addition (see Appendix E for details). Whether urine specimens with ionic radiographic media present are accepted for urinalysis testing varies among institutions. See Table 7.12 for a summary of ionic radiographic media crystal characteristics.

Drug Crystals

Most drugs and their metabolites are eliminated from the body by the kidneys. As urine forms within the nephrons, high concentrations of these agents (prescribed or overdose) combined with an optimal pH can cause their precipitation out of solution. Additional factors that promote drug crystalluria include dehydration as well as hypoalbuminemia, which increases the level of unbound drug in the bloodstream. Note that unbound drug in the plasma can freely pass the glomerular filtration barrier.

Remember, solute crystallization is a balancing act between solute concentration and pH. However, crystal formation can occur at a less optimal pH when the concentration of the solute is very high. It is also important to note that some drugs (naftidrofryl oxalate [a vasodilator], orlistat [oral inhibitor of lipase]) as well as some iatrogenic substances (ethylene glycol, toluene inhalants) can cause a crystalluria—not of the drug itself but of its principal metabolite, oxalate. In other words, when calcium oxalate crystalluria (usually of monohydrate forms) is observed, it may be directly linked to the metabolism of a drug.

Proper identification and reporting of drug crystals are important because if crystals are forming in vivo (i.e., in the renal tubules), they can cause kidney damage, that is, crystal-induced acute kidney injury. When unusual crystals are encountered in urine sediment, the healthcare provider should be contacted to obtain a list of the patient’s medications. Treatments to prevent in vivo crystal formation and its adverse effects include: increasing hydration, infusion of pH-adjusting agents, or cessation of the offending drug.

Table 7.13 provides a summary of drug crystals discussed in this section. This table is not organized by drug name but by crystal appearance, with pH also aiding in differentiation. It is important to note that all of these drug crystals are strongly birefringent when using polarizing microscopy and different drugs can form similar-looking crystals. Therefore, before reporting the presence of a drug crystal in urine it must be established what drug(s) the individual is either taking or has had access to. A good guideline is that whenever a very large number of unusual crystals are observed in urine sediment, suspect a drug crystal. Table 7.16 can also be helpful when attempting to identify urine crystals.

Acyclovir

Acyclovir is an antiviral drug. When a patient is dehydrated or when the drug is given as an intravenous bolus, acyclovir crystals may form in neutral to alkaline urine (pH >6). Acyclovir crystals are colorless and needle-shaped with pointed or blunt ends (Fig. 7.109). They can appear singly or in bunches and are strongly birefringent when using polarizing microscopy.

Ampicillin and Amoxicillin

Ampicillin and amoxicillin are two β-lactam antibiotics of the penicillin family that can form urine crystals. These antibiotics are used to treat or prevent many different types of bacterial infections. Both drugs form crystals in acid (pH <6) urine and appear as colorless, long, thin needles or prisms (Fig. 7.110). The individual needles may aggregate into small groupings or, with refrigeration, into large clusters. When observed in urine, the crystals most often indicate large doses of the drug with inadequate hydration.

Indinavir

Indinavir sulfate (Crixivan) is an HIV-1 protease inhibitor. Its slender needle crystals often aggregate together into bunches, broom-like bundles, rosettes, or cross forms (Fig. 7.111). The crystals are strongly birefringent when observed under polarizing microscopy. Indinavir crystals are most often observed in neutral to alkaline (pH >6) urine.

Sulfonamides

Sulfonamide drug crystals appear in acid urine (<6). They can take various forms depending on the particular drug prescribed. Historically, sulfonamide preparations were relatively insoluble and resulted in kidney damage caused by crystal formation within the renal tubules. Currently, these drugs have been modified and their solubility is no longer a problem. As a result, sulfonamide crystals are not found as often in urine sediment and renal damage caused by them is uncommon.

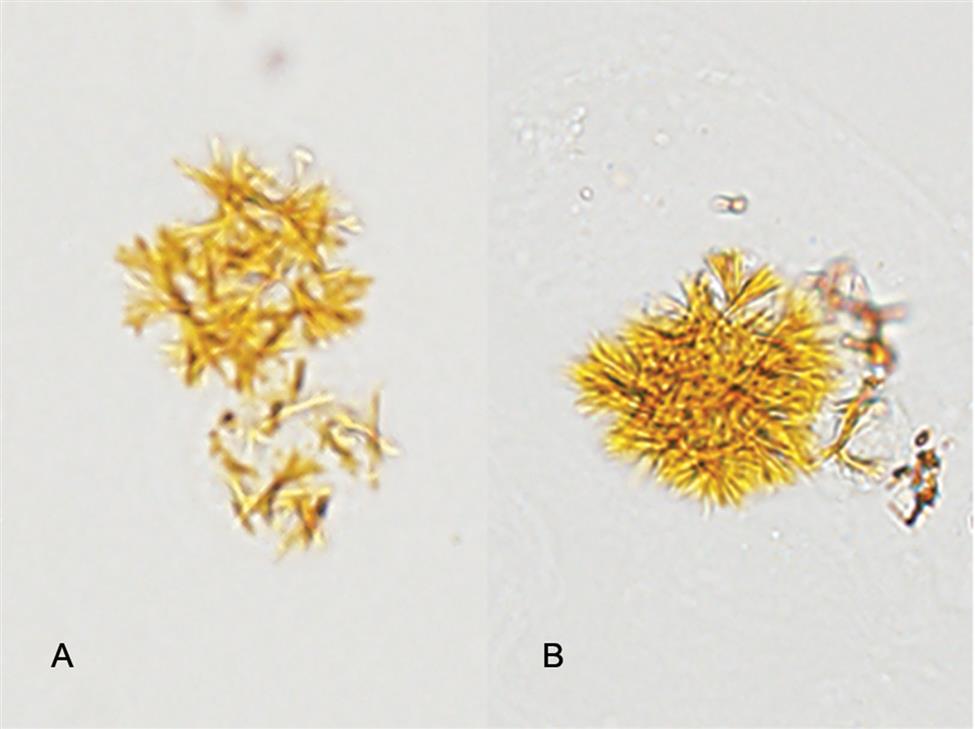

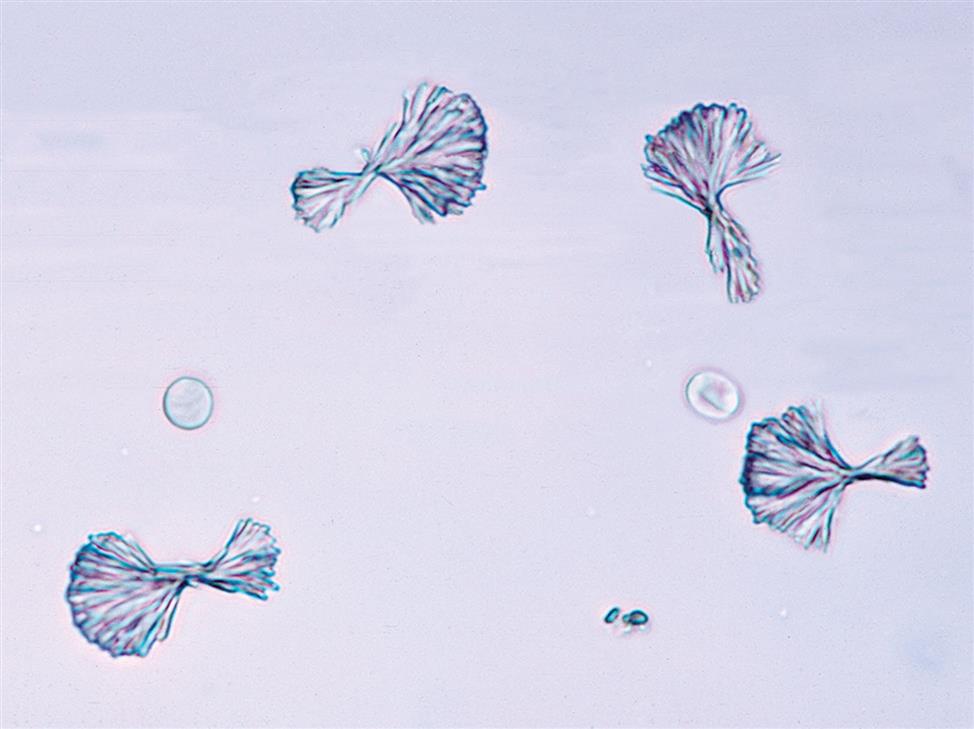

Sulfadiazine is a short-acting sulfonamide often used to treat Toxoplasma encephalitis in patients with AIDS. Its crystals are yellow-brown and shaped like sheaves of wheat (Fig. 7.112) or in shell (fan) forms (see Urine Sediment Image Gallery, Fig. 50). Both forms have radial striations.

Sulfamethoxazole (e.g., Bactrim, Septra) is a combination antibiotic used to treat a variety of infections (e.g., ear, urinary tract, bronchitis). Its crystals are more commonly encountered and they appear as yellow-brown spheres or globules with dimples or irregular creases (Fig. 7.113). In shape and color, sulfamethoxazole crystals can closely resemble ammonium biurate crystals but can be differentiated from them on the basis of pH, solubility, and the sulfonamide chemical confirmatory test. Note that a list of the patient’s current and past medications is of value in confirming the identity of these urine crystals.

Sulfadiazine and sulfamethoxazole crystals are present in acid (pH <6) urine. They are highly refractile under brightfield microscopy and strongly birefringent under polarizing microscopy, and should be confirmed chemically before they are reported. The rapid chemical test to confirm the presence of a sulfonamide is based on the diazotization of sulfanilamide followed by an azo coupling reaction. See Appendix E, “Manual and Historic Methods of Interest,” for procedural details and performance.

Primidone and Triamterene

Primidone is an anticonvulsant medication and it can form colorless hexagonal crystals that look like cystine crystals. Triamterene, a diuretic, can form urine crystals that are brown and look like ammonium biurate.

Both of these drug crystals are strongly birefringent when using polarizing microscopy. This characteristic helps distinguish primidone (strong birefringence) from cystine (weak birefringence). Regarding triamterene crystals, they form a pseudo-Maltese cross pattern under polarizing microscopy, which distinguishes them from ammonium biurate crystals that look similar but do not produce a cross pattern.

Crystal Summary

Although crystals are frequently encountered in the urine sediment, their presence often has minimal diagnostic or health implications. At other times crystal identification can provide crucial clues to a patient’s condition or renal status, even to the point of helping save a life. For example, identifying and reporting many calcium oxalate crystals in urine from a comatose acidotic individual in the emergency department could guide clinicians to suspect ethylene glycol ingestion and timely lifesaving treatment.

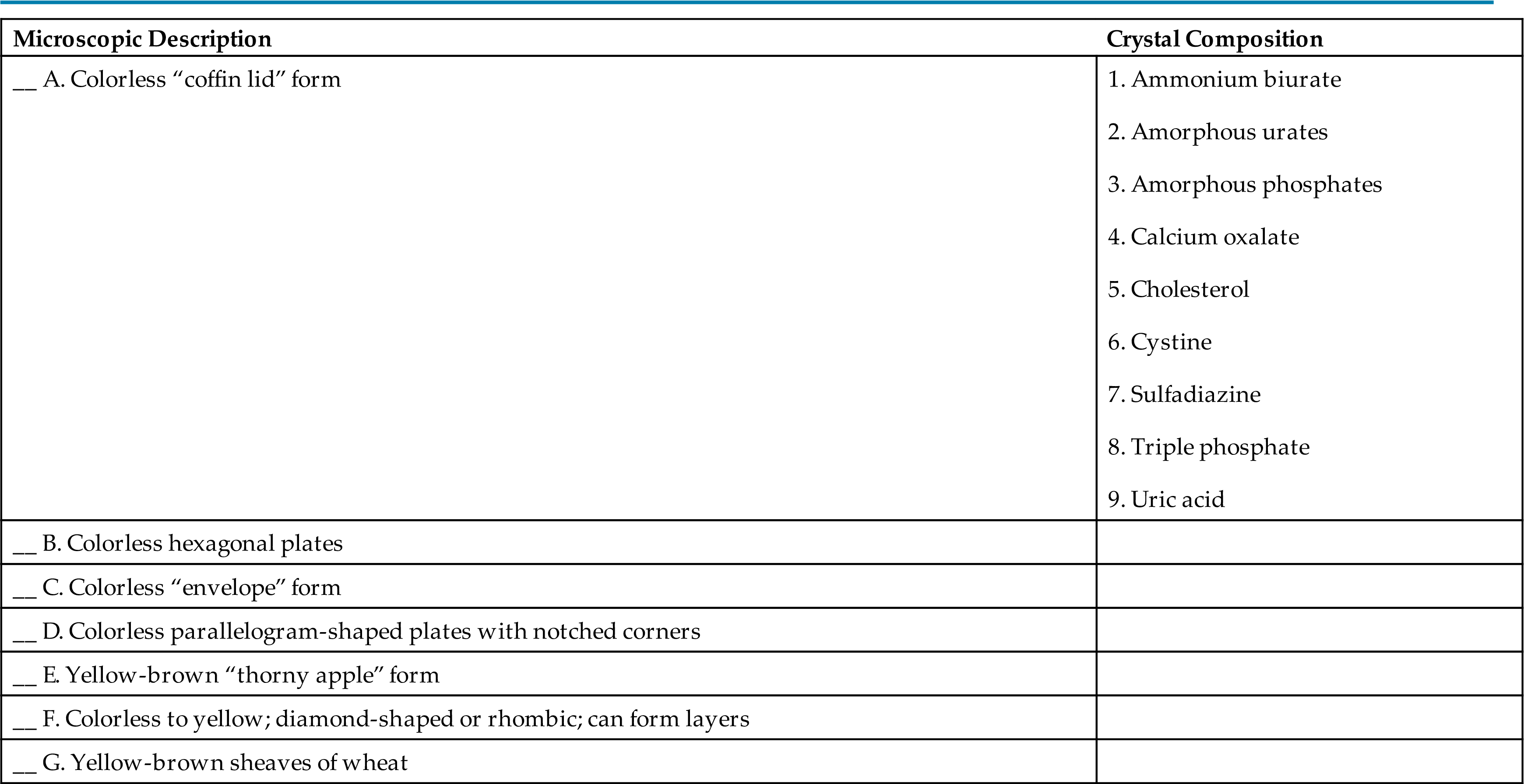

Because crystals are dynamic—undergoing formation (growing) and at times, dissolution—a single image does not capture the various stages and changes that can occur. In addition, crystals of different composition can have similar shapes. To facilitate correct identification, Table 7.16 (at the end of the chapter) categorizes crystals by shape. Also, additional images of crystals are provided in the Urine Sediment Image Gallery that immediately follows this chapter.

Note that the use of polarizing microscopy can be instrumental when identifying crystals (i.e., type and degree of birefringence) or when simply trying to determine whether an entity is crystalline (e.g., CaOx) or organic (e.g., RBC), see Fig. 7.90. Therefore, Chapter 18 provides a discussion of polarizing microscopy, directions for its use, as well as tables and pictures to enhance understanding of birefringence (Tables 18.1 and 18.2).

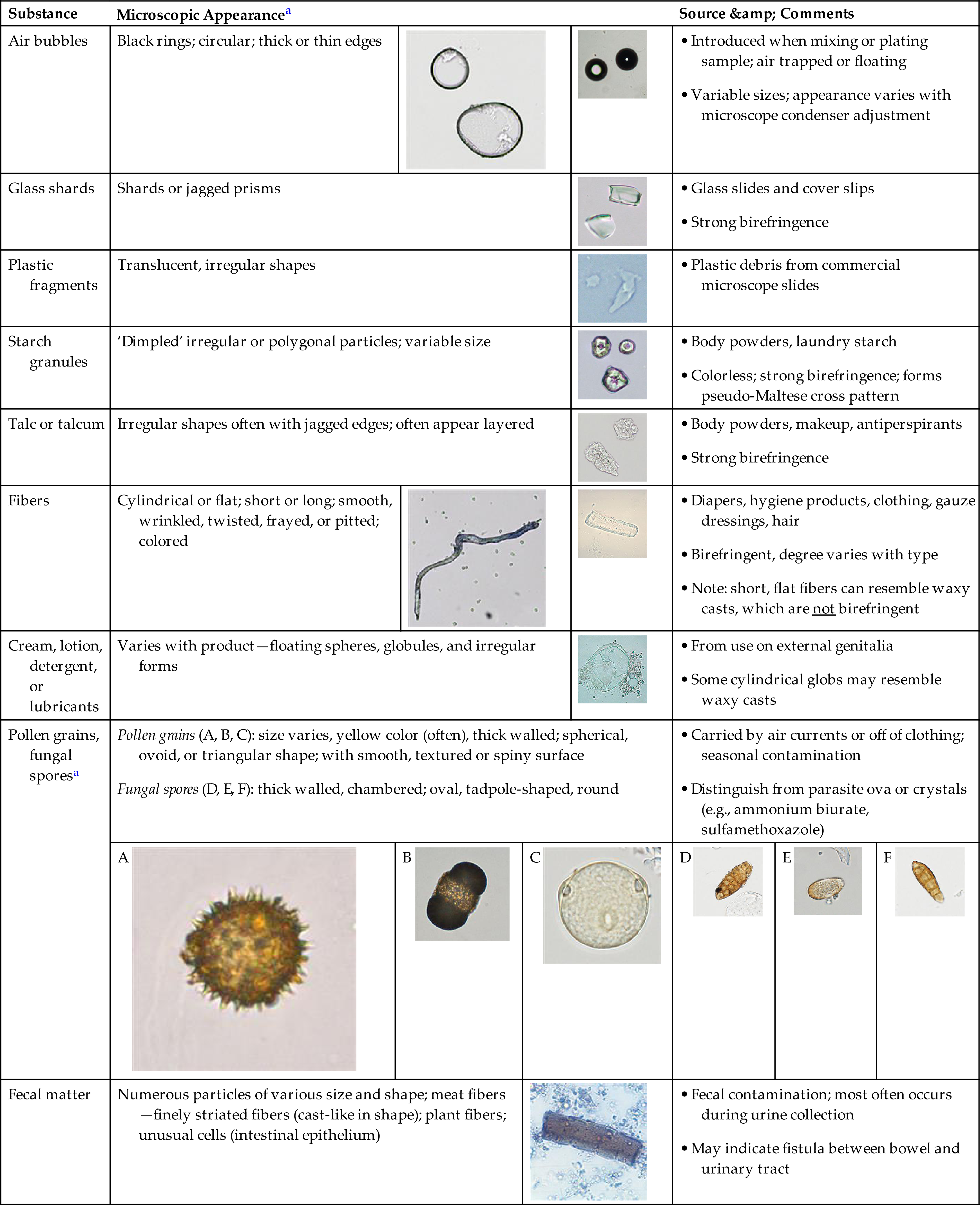

Contaminants

A variety of substances observed in urine sediment are considered contaminants and they can originate from either the patient, the laboratory, or the environment. See Table 7.14 for a list of commonly encountered contaminants, a description of their microscopic appearance with representative images, possible sources, and additional information that can aid in correctly identifying them. Note that it is equally imperative that a microscopist is able to identify contaminants and artifacts that should be disregarded as it is that they can properly identify elements of clinical importance. Note that additional images of contaminants can also be found in the Urine Sediment Image Gallery immediately follows this chapter.

Table 7.14

| Substance | Microscopic Appearancea | Source & Comments | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Air bubbles | Black rings; circular; thick or thin edges |  |

|

||||||

| Glass shards | Shards or jagged prisms |  |

|||||||

| Plastic fragments | Translucent, irregular shapes |  |

|||||||

| Starch granules | ‘Dimpled’ irregular or polygonal particles; variable size |  |

|||||||

| Talc or talcum | Irregular shapes often with jagged edges; often appear layered |  |

|||||||

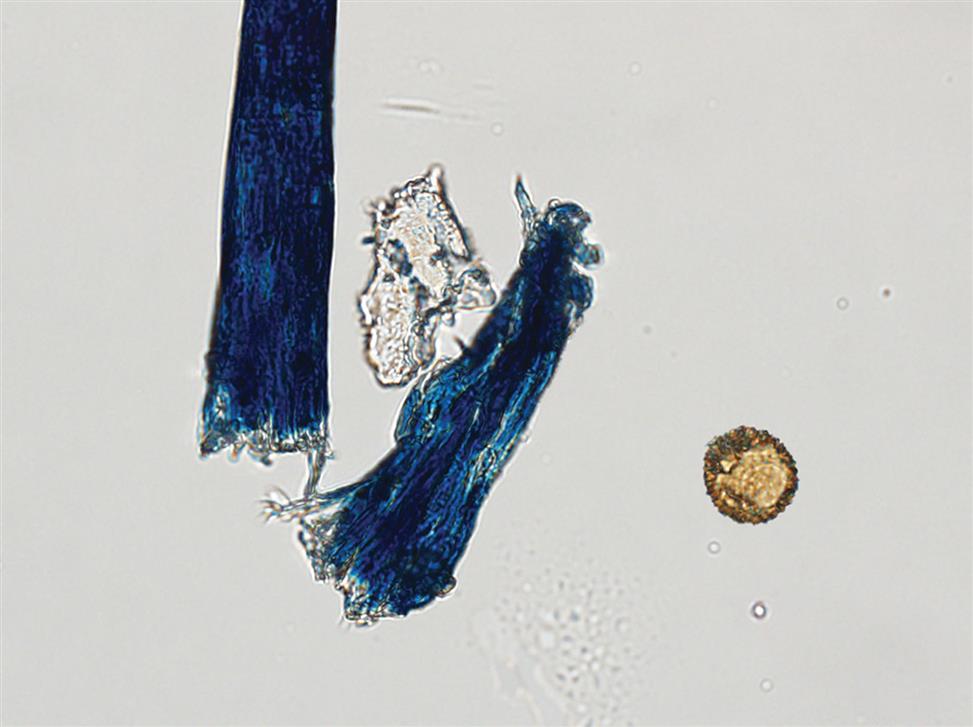

| Fibers | Cylindrical or flat; short or long; smooth, wrinkled, twisted, frayed, or pitted; colored |  |

|

||||||

| Cream, lotion, detergent, or lubricants | Varies with product—floating spheres, globules, and irregular forms |  |

|||||||

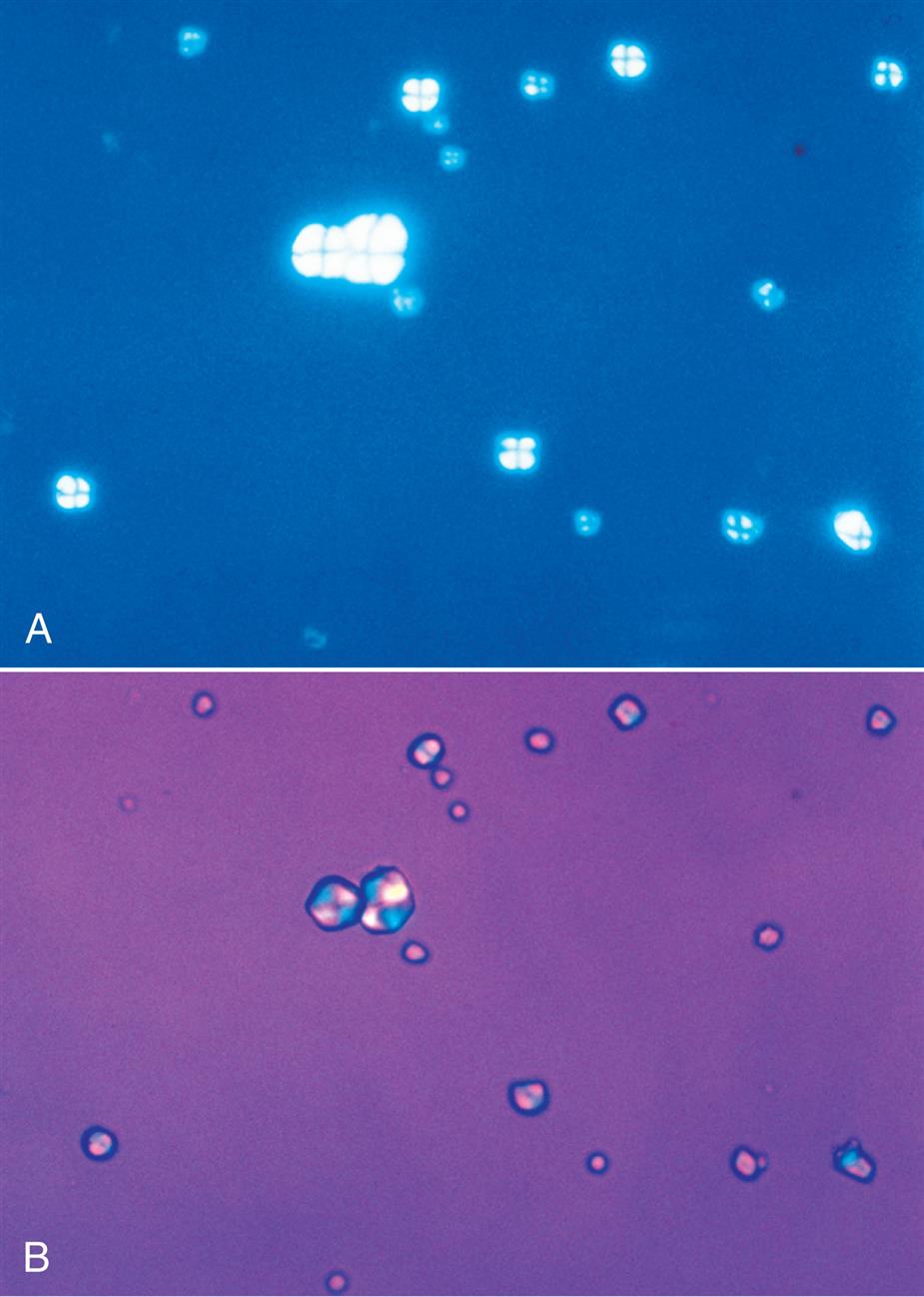

| Pollen grains, fungal sporesa | |||||||||

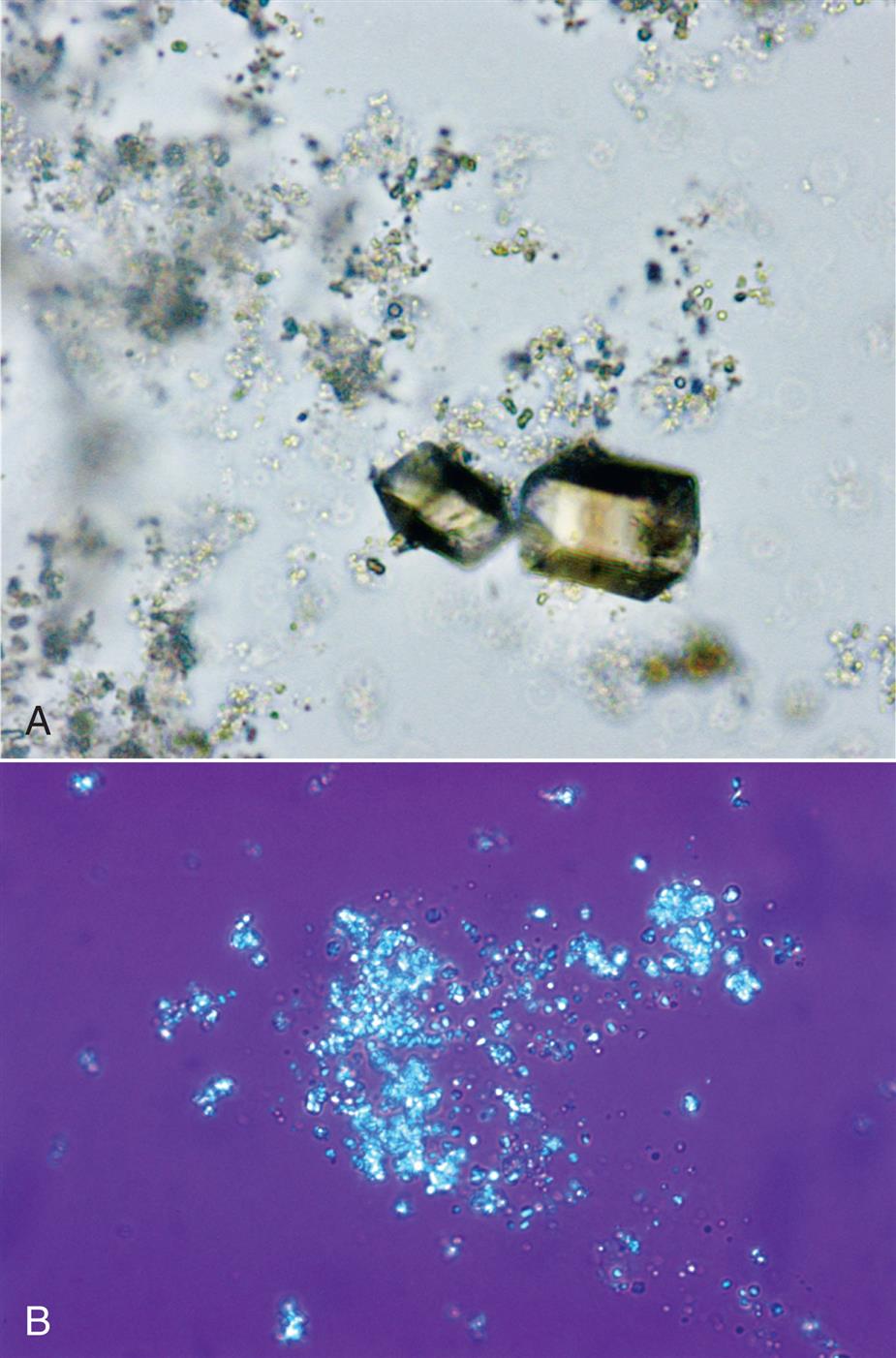

A  |

B  |

C  |

D  |

E  |

F  | ||||

| Fecal matter | Numerous particles of various size and shape; meat fibers—finely striated fibers (cast-like in shape); plant fibers; unusual cells (intestinal epithelium) |  |

|||||||

aNote that images within and between categories are not on the same size scale.

From the Laboratory

It does not matter whether plastic commercial slides or glass microscope slides and coverslips are used to perform the microscopic exam, both can contribute a contaminant to the urine sediment. Glass shards are sharp, jagged prisms that are very refractile and easy to see (see Urine Sediment Image Gallery, Fig. 5). They are also strongly birefringent under polarizing microscopy. Plastic fragments from commercial slides are irregular-shaped and translucent (see Urine Sediment Image Gallery, Figs. 3 and 4). If you want to see these contaminants without any urine components, simply plate clean water using your slide supplies and review it microscopically. Air bubbles are usually introduced under the coverslip when plating a sample for microscopic review or may result when a specimen has been shaken before plating (see Urine Sediment Image Gallery, Fig 1 and 2).

From the Patient

Starch and Talc

Starch and talc particles originate from a variety of sources and can be encountered microscopically in the urine sediment. Prior to 2009, the interior of all protective gloves worn by healthcare workers were dusted with starch or talc to make them easier to wear. However, this use is now banned for surgical gloves and manufacturing practices have been changed to compensate for the lack of a powder. Today, with the widespread use of powderless gloves, starch and talc are not seen as often in urine sediment. Starch can still contaminate the urine from other sources, such as body powders or from clothing that has be treated with laundry starch. Sources of talc or talcum powder include body powders (e.g., baby powder), makeup, and antiperspirants.

Starch has unique visual characteristics that make it easy to identify. Starch granules can vary greatly in size and usually have a centrally located dimple (Fig. 7.114). They are colorless, irregular polygonal particles with scalloped or faceted edges. Under polarizing microscopy, starch granules are strongly birefringent and exhibit a pseudo-Maltese cross pattern (i.e., unequal quadrants), the edges of which are not distinct nor perfectly round (Fig. 7.115). Starch granules are readily differentiated from cholesterol droplets because of distinct visual differences using brightfield microscopy. For a side-by-side comparison, see Table 18.1 in Chapter 18.

Talc particles also vary in size but appear as irregular, jagged pieces. They are colorless and may appear layered like shale (Fig. 7.116 and Urine Sediment Image Gallery, Fig. 6).

Because starch granules and talc particles are urine contaminants, they are not reported. Excessive quantities could interfere with the examination, however, and may necessitate the collection of a new specimen.

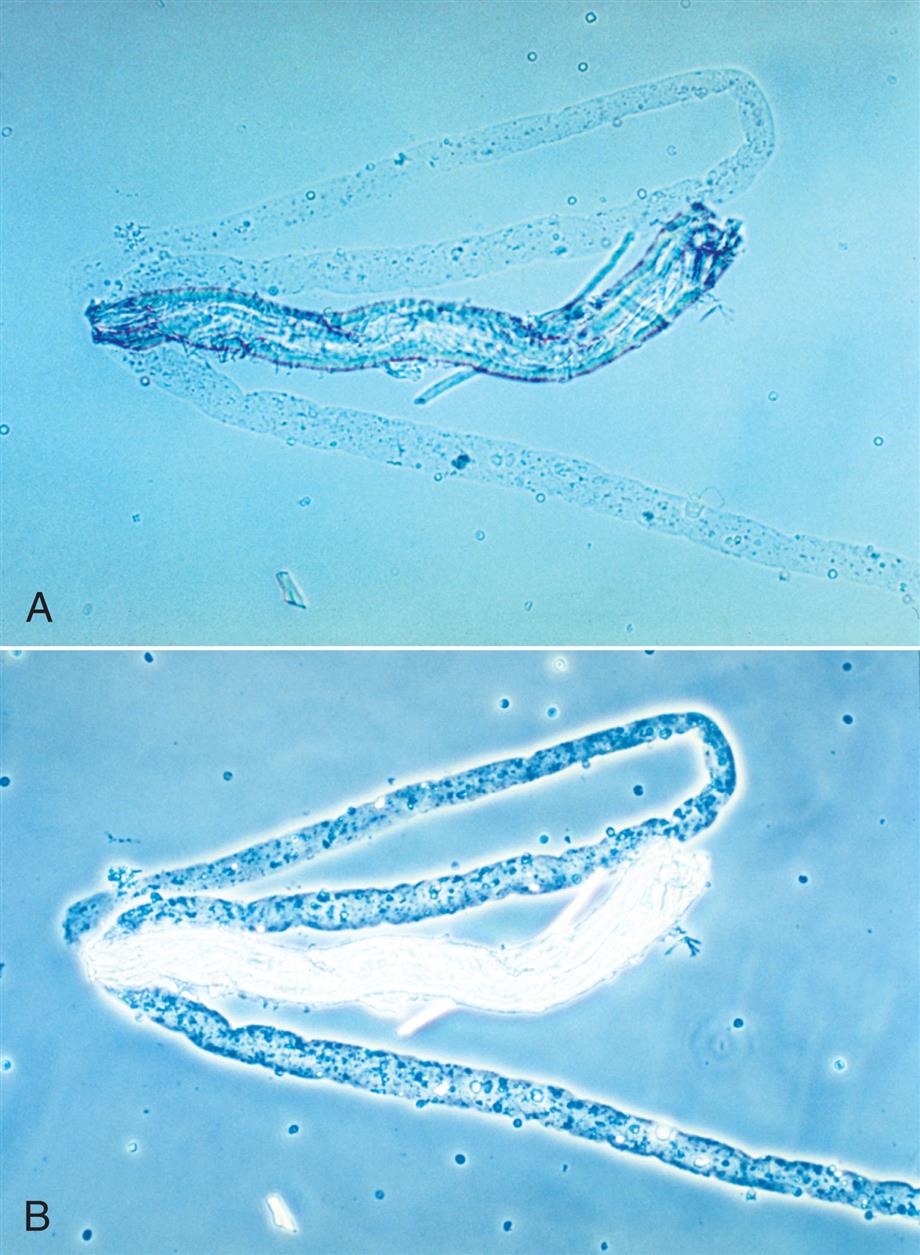

Fibers

Numerous types of fibers, such as hair, cotton, fabric threads, and absorbent fibers from diapers and hygiene products often appear in urine sediment. They are considered contaminants and are disregarded during the microscopic examination. It is important to ensure their proper identification by the novice microscopist. Because of the variety of sources, fibers have a variety of appearances. They can be long or short, wide or thin, smooth, wrinkled, twisted or frayed. One common feature is their strong birefringence under polarizing microscopy.

Fibers from clothing, gauze dressings, or hair are usually easy to recognize using brightfield microscopy because of their strong refractility in comparison to casts (Figs. 7.116 and 7.117). Similar but more challenging are fibers from diapers or hygiene products because they can resemble urinary casts. Diaper fibers tend to be flat with distinct edges and appear thicker at their margins, sometimes with wrinkles; in contrast, urinary casts are thicker in the middle and do not have wrinkles (see Fig. 7.60 and Urine Sediment Image Gallery, Fig. 7). The strong birefringence of fibers also differentiates them from matrix of casts, which are not birefringent (compare Fig. 7.60 [fiber] to Figs. 7.54B and 7.56B [cast matrix]).

Creams and Lotions

Any cream, lotion, detergent, or lubricant used in or around the external genitalia could potentially be washed into a urine specimen during collection. Depending on the product, the microscopic appearance will vary. The product may appear as round droplets of variable size suspended in the urine sediment, similar to many free-floating fat droplets; however, these droplets are numerous, dull, and translucent in appearance. Creams can appear as globules or irregular masses (see Table 7.14); sometimes a mass may appear cylindrical-shaped and need to be distinguished from a waxy cast.

Fecal Matter

Fecal material contaminates urine primarily by two modes: through improper collection technique and through an abnormal connection or fistula between the urinary tract and the bowel. Specimens received from infants and from patients who are extremely ill or physically compromised are most likely to be contaminated with fecal material because of the difficulty involved in performing the urine collection. With the assistance of a healthcare worker for ill or physically compromised patients or the use of collection bags for infants, urine specimens can be obtained without contamination. In contrast, a fistula continually channels fecal material into the urinary tract and this contamination cannot be eliminated. In such cases, the patient has a persistent UTI from the constant influx of normal bacterial flora from the intestine into the urinary tract; food remnants can also be present in the urine sediment.

Fecal contamination of urine specimens is often not grossly apparent. Microscopic examination of the urine sediment can reveal the abnormal presence of partially digested vegetable cells and muscle fibers from ingested foods.

From the Environment

Pollen Grains and Fungal Spores

Pollen grains and fungal spores are occasionally seen in urine sediment. They are introduced into the urine specimen from air currents or from the surfaces of clothing during or after collection. Pollen grains vary in shape and size but they are usually large, thick-walled, and yellow in color (see Fig. 7.116 and Table 7.14). Their shape and texture vary with the plant species. Pollen can be spherical, ovoid, or triangular with smooth, textured, or spiny surfaces. Similarly, fungal spores are large, thick-walled elements, often with chambers. They are usually round, oval, or tadpole-shaped with smooth outer surfaces.

Correlation of Urine Sediment Findings With Disease

Most urine sediment findings are not unique for a specific disorder; rather, they indicate a process (e.g., infection, inflammation) or functional change (e.g., glomerular changes, tubular dysfunction, obstruction) that is occurring in the kidneys or urinary tract. Other entities can point to a hereditary disease (cystine crystals) or an iatrogenic agent (drug crystals). A challenge for healthcare providers can be to determine the cause of the disorder and its location within the urinary tract. Consequently, it is the entire urinalysis—the physical, chemical, and microscopic examinations—that best enables healthcare providers to detect and monitor disease in the urinary tract. When serial specimens (daily or weekly) are obtained from a patient, the urinalysis test provides an economical means to monitor the progression or resolution of a disorder.

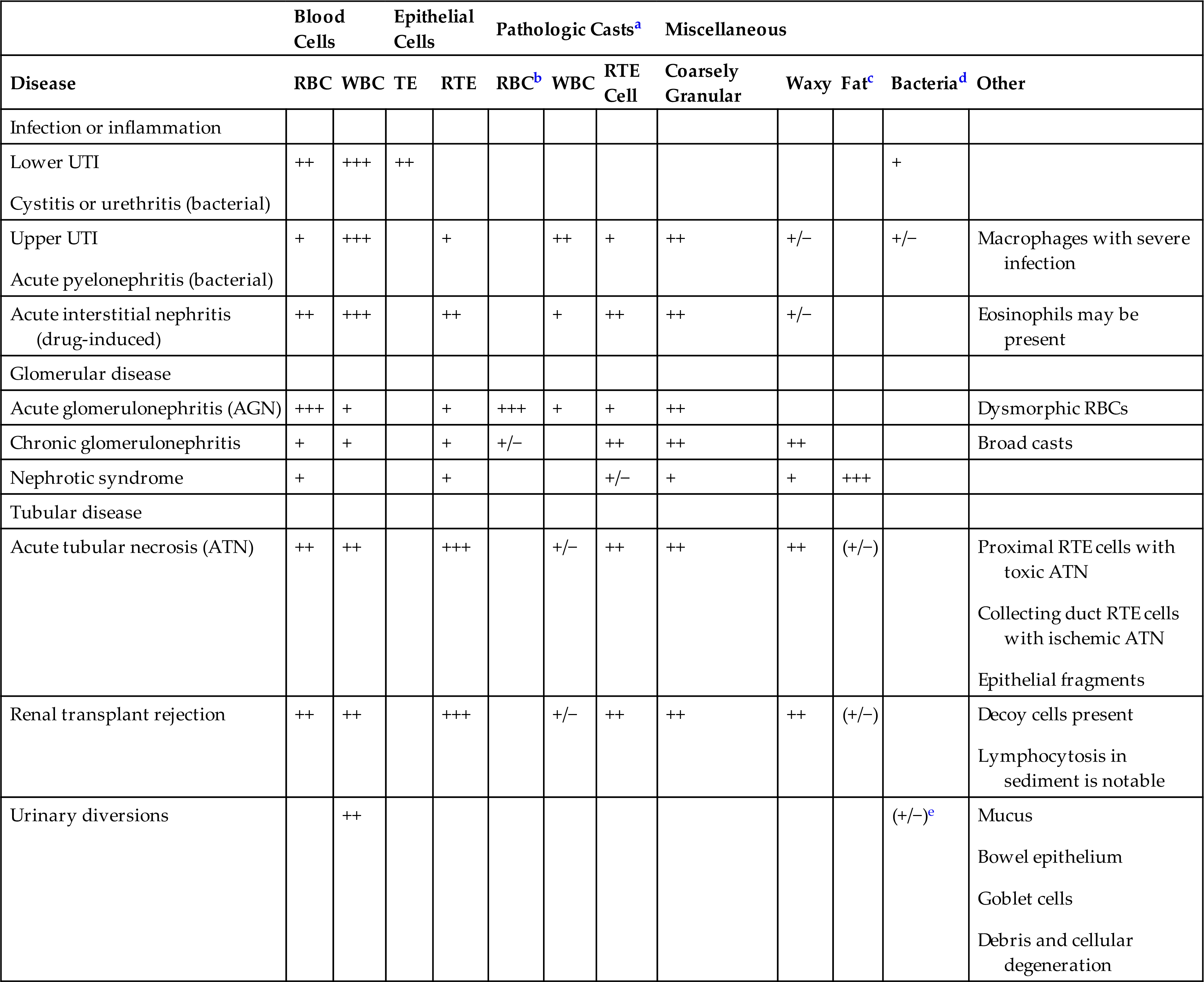

Table 7.15 links the urine sediment findings discussed in this chapter to selected disorders of the urinary tract that are discussed in Chapter 8. In health, the urine sediment may have a few epithelial cells, a rare RBC, and few WBCs (see Table 7.4). A few hyaline casts or an occasional finely granular cast may also be observed, but because the urinary tract is sterile, microorganisms such as bacteria and yeast should not be present. Note that hyaline casts are not listed in this table because they are not considered pathologic casts (i.e., indicative of disease). However, increased numbers of hyaline casts can be observed in the urine sediment with each of these disorders. Some urine sediment findings point specifically to a disease process (e.g., presence of bacteria and WBCs indicates an infection), whereas other findings identify the location of a disease process (e.g., WBC casts, RBC casts indicate a process occurring in the kidneys, where casts are formed). See Chapter 8 for further discussion of renal and metabolic diseases, including their clinical features, pathogenesis, and urinalysis results associated with each.To assist in crystal identification, Table 7.16 categorizes crystals solely based on shape. The order of appearance in each category is by prevalence, and the font color indicates the predominant pH in which the crystals form.

Table 7.15

| Blood Cells | Epithelial Cells | Pathologic Castsa | Miscellaneous | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Disease | RBC | WBC | TE | RTE | RBCb | WBC | RTE Cell | Coarsely Granular | Waxy | Fatc | Bacteriad | Other |

| Infection or inflammation | ||||||||||||

| ++ | +++ | ++ | + | |||||||||

| + | +++ | + | ++ | + | ++ | +/− | +/− | Macrophages with severe infection | ||||

| Acute interstitial nephritis (drug-induced) | ++ | +++ | ++ | + | ++ | ++ | +/− | Eosinophils may be present | ||||

| Glomerular disease | ||||||||||||

| Acute glomerulonephritis (AGN) | +++ | + | + | +++ | + | + | ++ | Dysmorphic RBCs | ||||

| Chronic glomerulonephritis | + | + | + | +/− | ++ | ++ | ++ | Broad casts | ||||

| Nephrotic syndrome | + | + | +/− | + | + | +++ | ||||||

| Tubular disease | ||||||||||||

| Acute tubular necrosis (ATN) | ++ | ++ | +++ | +/− | ++ | ++ | ++ | (+/−) | ||||

| Renal transplant rejection | ++ | ++ | +++ | +/− | ++ | ++ | ++ | (+/−) | ||||

| Urinary diversions | ++ | (+/−)e | ||||||||||

RBC, red blood cell; TE, transitional epithelial; UTI, urinary tract infection; WBC, white blood cell.

aNote that hyaline casts, which are not considered pathologic, are often present in increased numbers in the listed conditions.

bIncludes blood and hemoglobin casts.

cIncludes fatty casts, oval fat bodies (OFBs), and free-floating fat droplets.

dQuantity of bacteria observed can vary from few to many; does not reflect severity of bacterial infection.

eVaries with type of diversion.

Study Questions

- 3. The microscopic identification of hemosiderin is enhanced when the urine sediment is stained with

- 4. When the laboratorian performs the microscopic examination of urine sediment, which of the following are enumerated using low-power magnification?

- 5. A urine sediment could have which of the following formed elements and still be considered “normal”?

- 6. Which of the following statements about red blood cells in urine is true?

- 7. Hemoglobin is a protein and will

- A. does not react in the protein reagent strip test.

- B. interfere with the protein reagent strip test, producing erroneous results.

- C. always contribute to the protein reagent strip result, regardless of the amount of hemoglobin present.

- D. contribute to the protein reagent strip result only when large concentrations of hemoglobin are present.

- 9. Which of the following is not a characteristic of neutrophils found in the urine sediment?

- 10. How do increased numbers of leukocytes usually get into the urine?

- 11. Which statement regarding lymphocytes found in urine sediment is correct?

- 12. Which of the following urinary tract structures is not lined with transitional epithelium?

- 13. Match the number of the epithelial cell type with its characteristic feature. Only one type is correct for each feature.

- 15. Urinary casts are formed in

- 16. Urinary casts are formed with a core matrix of

- 17. Which of the following does not contribute to the size, shape, or length of a urinary cast?

- 18. All of the following enhance urinary cast formation except

- 19. When the laboratorian is using brightfield microscopy, a urinary cast that appears homogeneous with well-defined edges, blunt ends, and cracks is most likely a

- 20. All of the following can be found incorporated into a cast matrix except

- 21. Which of the following urinary casts are diagnostic of glomerular or renal tubular damage?

- 22. Which of the following characteristics best differentiates waxy casts from fibers that may contaminate urine sediment?

- 23. Which of the following does not affect the formation of urinary crystals within nephrons?

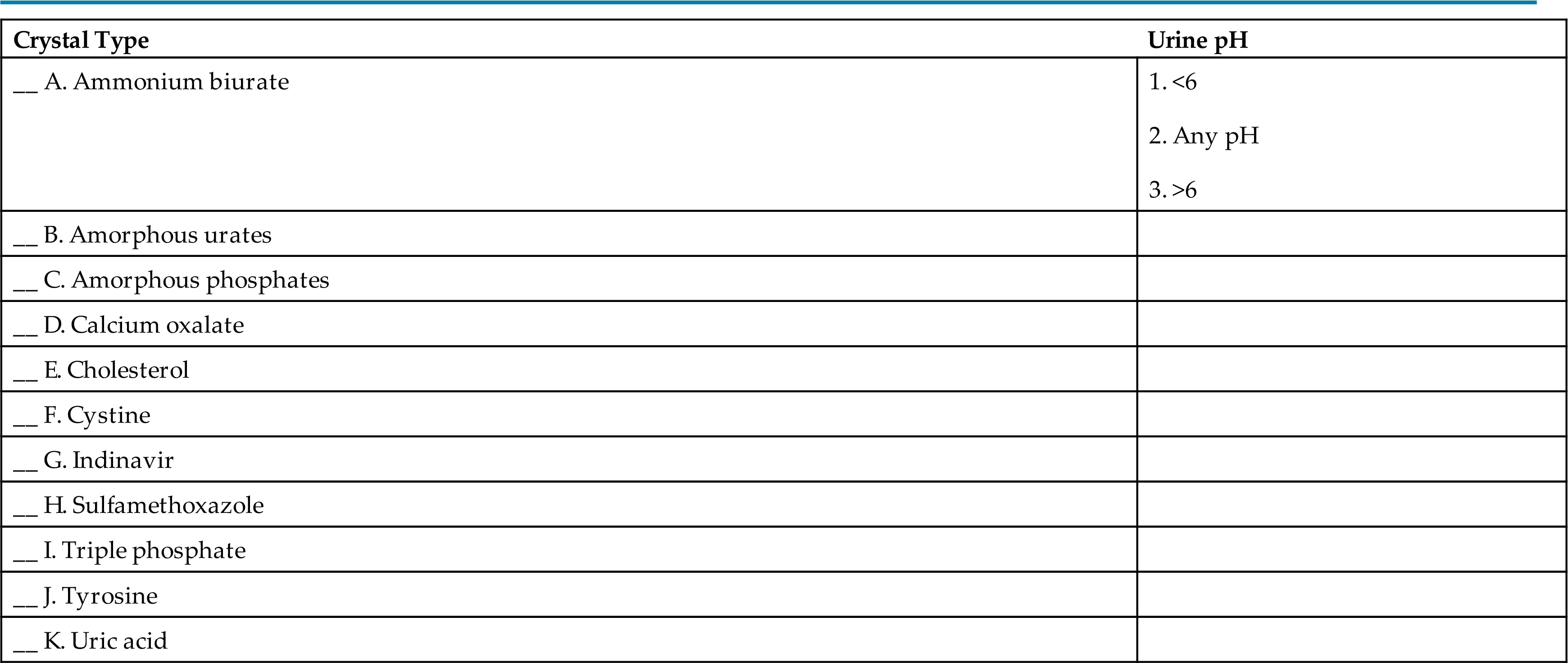

- 24. The formation of urinary crystals is associated with a specific urine pH. Match the urine pH that best facilitates crystalline formation with the crystal type.

- 25. Match the crystal composition with the microscopic description that best characterizes it.

- 26. Which of the following crystals, when found in the urine sediment, most likely indicates an abnormal metabolic condition?

- 28. When using brightfield microscopy, mucus threads can be difficult to differentiate from

- 29. Which of the following is not a distinguishing characteristic of yeast in the urine sediment?

- 30. Fat can be found in the urine sediment in all of the following forms except

- 31. Which of the following statements regarding the characteristics of urinary fat is true?

- 32. Which of the following statements regarding the microscopic examination of urine sediment is false?

- A. If large numbers of leukocytes are present microscopically, then bacteria are present.

- B. If urinary fat is present microscopically, then the chemical test for protein should be positive.

- C. If large numbers of casts are present microscopically, then the chemical test for protein should be positive.

- D. If large numbers of red blood cells are present microscopically, then the chemical test for blood should be positive.

- 33. The following are initial results obtained during a routine urinalysis. Which results should be investigated further?

- 34. The following are initial results obtained during a routine urinalysis. Which results should be investigated further?

- 35. Which of the following when found in the urine sediment from a female patient is not considered a vaginal contaminant?