Pleural, Pericardial, and Peritoneal Fluid Analysis

After studying this chapter, the student should be able to:

- 1. Describe the function of serous membranes as they relate to the formation and absorption of serous fluid.

- 2. Describe four pathologic changes that lead to the formation of an effusion.

- 3. Discuss appropriate collection requirements for serous fluid specimens.

- 4. Classify a serous fluid effusion as a transudate or an exudate based on the examination of its physical, microscopic, and chemical characteristics.

- 5. Compare and contrast chylous and pseudochylous effusions.

- 6. Correlate the microscopic examination and differential cell count of serous fluid analyses with diseases that affect the serous membranes.

- 7. Correlate the concentrations of selected chemical constituents of serous fluids with various disease states.

- 8. Discuss the microbiological examination of serous fluids and its importance in the diagnosis of infectious diseases.

Key Terms1⁎ *

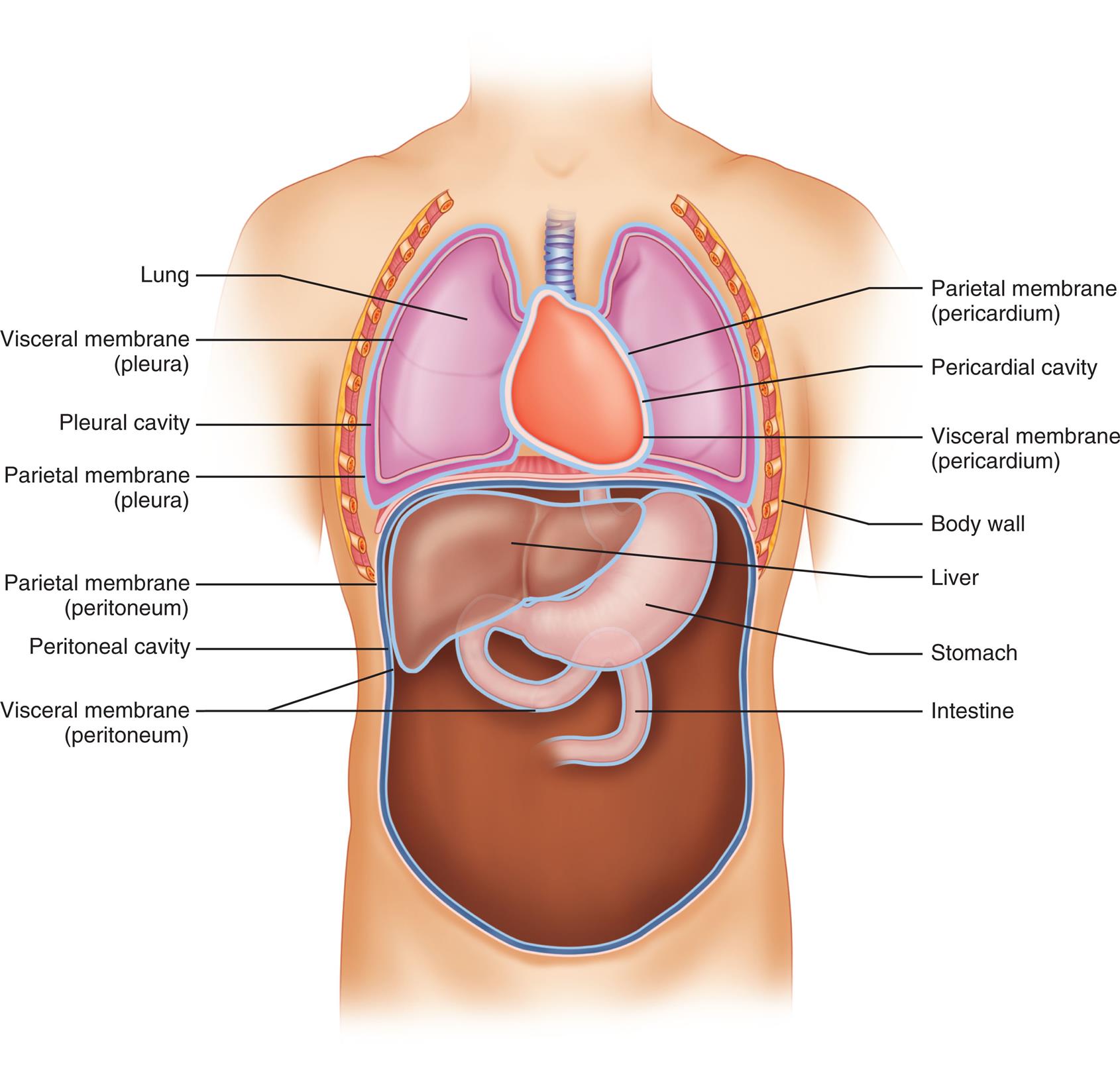

Physiology and Composition

The lungs, heart, and abdominal organs are surrounded by a thin, continuous serous membrane, as well as by the internal surfaces of the body cavity wall. A space or cavity filled with fluid lies between the membrane that covers the organ (visceral membrane) and the membrane that lines the body wall (parietal membrane) (Fig. 10.1). Each cavity is separate and is named for the organ or organs it encloses. The lungs are individually surrounded by a pleural cavity, the heart by the pericardial cavity, and the abdominal organs by the peritoneal cavity. The serous membranes that line these cavities consist of a thin layer of connective tissue covered by a single layer of flat mesothelial cells. Within the membrane is an intricate network of capillary and lymphatic vessels. Each membrane is attached firmly to the body wall and the organ it surrounds; however, the opposing surfaces of the membrane—despite close contact—are not attached to each other. Instead, the space between the opposing surfaces (i.e., between the visceral and parietal membranes) is filled with a small amount of fluid that serves as a lubricant between the membranes, which permits free movement of the enclosed organ. The cavity fluid is created and maintained through plasma ultrafiltration in the parietal membrane and absorption by the visceral membrane. The name serous fluid is a general term used to describe fluids that are an ultrafiltrate of plasma and therefore have a composition similar to that of serum.

The process of fluid formation and absorption in the pleural, pericardial, and peritoneal cavities is dynamic. Fluid formation is controlled simultaneously by four factors: (1) permeability of the capillaries in the parietal membrane; (2) hydrostatic pressure in these capillaries; (3) oncotic pressure (or colloid osmotic pressure) produced by the presence of plasma proteins within the capillaries; and (4) absorption of fluid by the lymphatic system (Box 10.1). Hydrostatic pressure (i.e., blood pressure) forces a plasma ultrafiltrate to form in the cavity; at the same time, plasma proteins in the capillaries produce a force (oncotic pressure) that opposes this filtration.

The permeability of the capillary endothelium regulates the rate of ultrafiltrate formation and its protein composition. For example, increased permeability of the endothelium will cause increased movement of protein from the blood into the cavity fluid. When this occurs, the now protein-rich fluid in the cavity further enhances the movement of more fluid into the cavity. Such an accumulation of fluid in a body cavity is termed an effusion and indicates an abnormal or pathologic process. The lymphatic system, or the fourth component in cavity fluid formation, plays a primary role in removing fluid from a cavity by absorption. However, if the lymphatic vessels become obstructed or impaired, they cannot adequately remove the additional fluid, resulting in an effusion. Other mechanisms can cause effusions, and they may occur with a variety of primary and secondary diseases, including conditions that cause a decrease in hydrostatic blood pressure (e.g., congestive heart failure, shock) and those characterized by a decrease in oncotic pressure (i.e., disorders characterized by hypoproteinemia).

A pleural, pericardial, or peritoneal effusion is diagnosed by a physical examination of the patient and on the basis of radiographic, ultrasound, or echocardiographic imaging studies. The collection and clinical testing of pleural, pericardial, and peritoneal fluids play an important role in determining the type of effusion present and in identifying its cause.

Specimen Collection

The term paracentesis refers to the percutaneous puncture of a body cavity for the aspiration of fluid. Other anatomically descriptive terms denote fluid collection from specific body cavities. Thoracentesis, for example, refers to the surgical puncture of the chest wall into the pleural cavity to collect pleural fluid, pericardiocentesis into the pericardial cavity, and peritoneocentesis (or abdominal paracentesis) into the peritoneal cavity. The term ascites refers to an effusion specifically in the peritoneal cavity, and ascitic fluid is simply another name for peritoneal fluid.

Collection of effusions from a body cavity is an invasive surgical procedure performed by a physician using sterile technique. Unlike cerebrospinal fluid and synovial fluid collections, serous fluid collections from effusions in the pleural, pericardial, and peritoneal cavities often yield large volumes of fluid. Consequently, the amount of fluid obtained often exceeds that needed for diagnostic testing. Note that at times, additional or repeat puncture procedures are necessary to remove a recurring effusion from a cavity for therapeutic purposes, such as when the effusion is compressing or inhibiting the movement of vital organs.

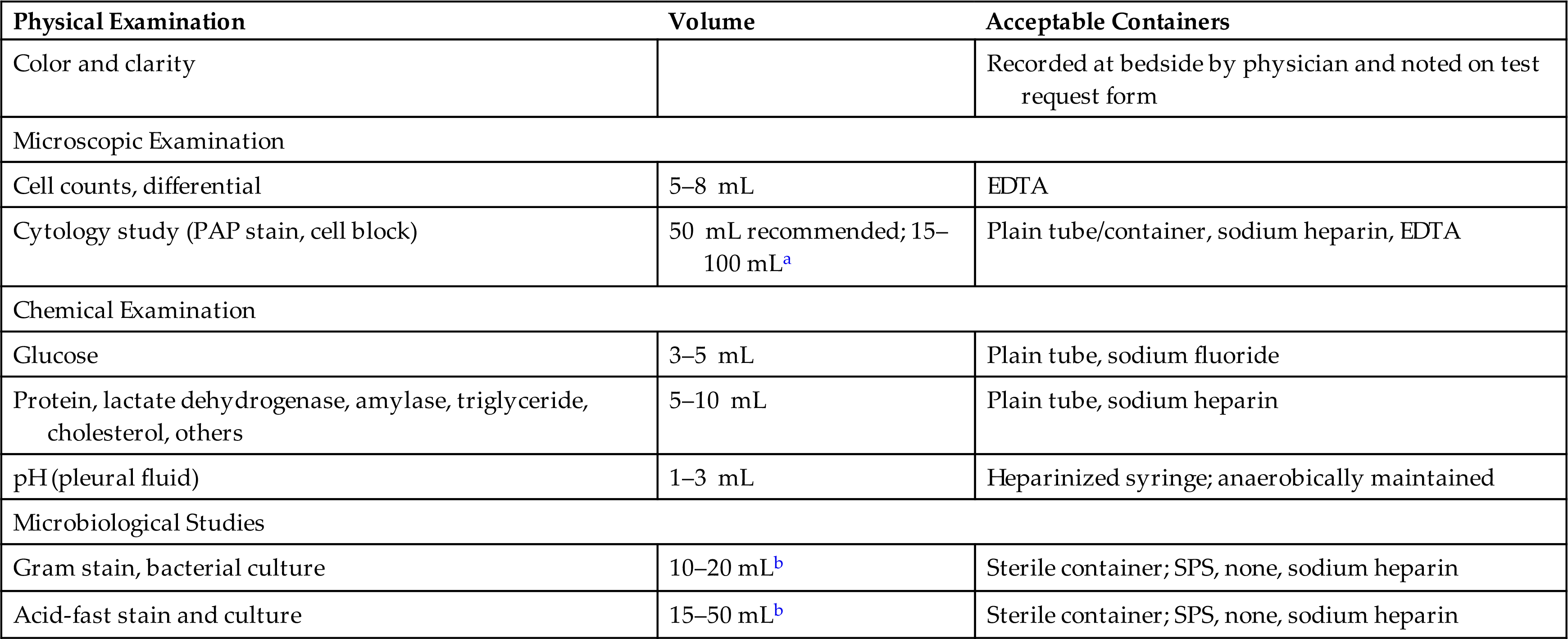

Before serous fluid is collected from a body cavity, the laboratory should be consulted to ensure that appropriate collection containers are used and suitable volumes are obtained (Table 10.1). In microbiological studies, the percentage of positive cultures obtained increases when a larger volume of specimen (10 to 20 mL) is used or when a concentrated sediment from a centrifuged specimen (50 mL or more) is used to inoculate cultures.

Table 10.1

| Physical Examination | Volume | Acceptable Containers |

|---|---|---|

| Color and clarity | Recorded at bedside by physician and noted on test request form | |

| Microscopic Examination | ||

| Cell counts, differential | 5–8 mL | EDTA |

| Cytology study (PAP stain, cell block) | 50 mL recommended; 15–100 mLa | Plain tube/container, sodium heparin, EDTA |

| Chemical Examination | ||

| Glucose | 3–5 mL | Plain tube, sodium fluoride |

| Protein, lactate dehydrogenase, amylase, triglyceride, cholesterol, others | 5–10 mL | Plain tube, sodium heparin |

| pH (pleural fluid) | 1–3 mL | Heparinized syringe; anaerobically maintained |

| Microbiological Studies | ||

| Gram stain, bacterial culture | 10–20 mLb | Sterile container; SPS, none, sodium heparin |

| Acid-fast stain and culture | 15–50 mLb | Sterile container; SPS, none, sodium heparin |

EDTA, Ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid; PAP, Papanicolaou; SPS, sodium polyanetholsulfonate.

aNo upper limit to the amount of fluid that can be submitted; large volumes of fluid enhance the recovery of cellular elements.

bLarge fluid volumes may facilitate the recovery of viable microbial organisms.

Normally, serous fluids do not contain blood or fibrinogen, but a traumatic puncture procedure, a hemorrhagic effusion, or an active bleed (e.g., from a ruptured blood vessel) can result in serous fluid that appears bloody and clots spontaneously. Therefore to prevent clot formation, which entraps cells and microorganisms, sterile tubes coated with an anticoagulant such as sodium heparin or liquid ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA) are used to collect fluid specimens for the microscopic examination and microbiological studies. In contrast, serous fluid for chemical testing is placed into a nonanticoagulant tube (red top), which will allow clot formation when fibrinogen or blood is present. Serous fluids should be maintained at room temperature and transported to the laboratory as soon as possible after collection to eliminate potential chemical changes, cellular degradation, and bacterial proliferation. Note that refrigeration (4–8°C) adversely affects the viability of microorganisms and should not be used for serous fluid specimens. However, serous fluid samples intended for cytology examination are an exception and can be refrigerated at 4°C when storage is necessary.

A blood sample must be collected shortly before or after the paracentesis procedure to enable comparison studies of the chemical composition of the effusion with that of the patient’s plasma. These studies enable classification of the effusion (transudate or exudate, chylous or pseudochylous), which assists in diagnosis and treatment. Note that for chemical analysis, the same type of specimen collection tube (nonanticoagulant, sodium heparin) should be used for both the fluid specimen and the blood collection (serum or plasma). In addition, specimen transport and handling conditions should be the same to eliminate result variations due to these potential differences.

Transudates and Exudates

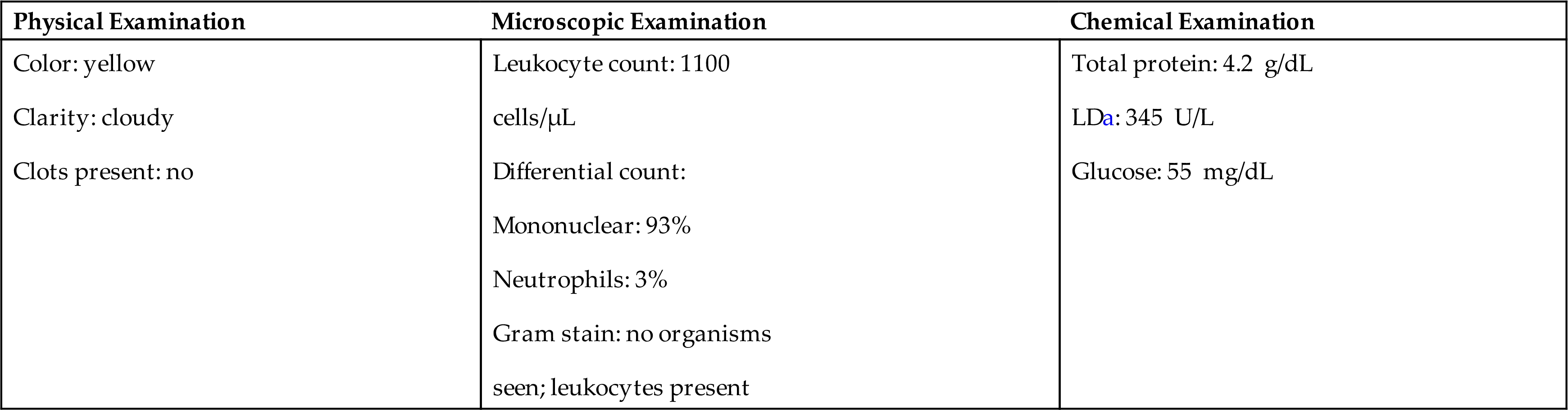

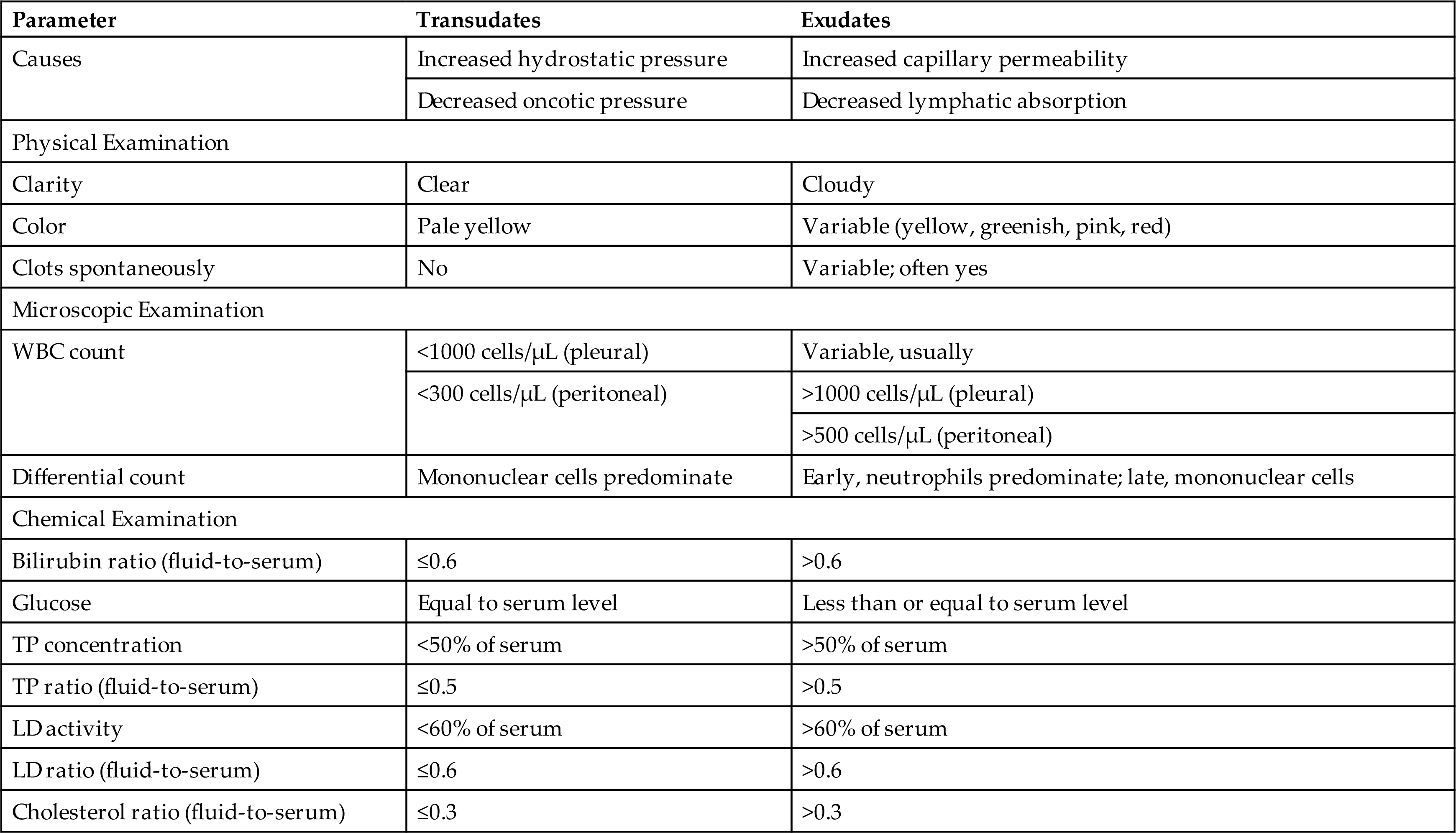

An effusion, particularly in the pleural or peritoneal cavity, is classified as a transudate or an exudate. This classification is based on several criteria, including appearance, leukocyte count, and total protein, lactate dehydrogenase, glucose, and bilirubin concentrations; however, because of the overlap among categories, no single parameter differentiates a transudate from an exudate in all patients.1 Table 10.2 lists parameters and the values associated with transudates and exudates.

Table 10.2

LD, Lactate dehydrogenase; TP, total protein; WBC, white blood cell.

Classifying an effusion as a transudate or exudate is important because this information assists the physician in identifying its cause. Transudates primarily result from a systemic disease that causes an increase in hydrostatic pressure or a decrease in plasma oncotic pressure in the parietal membrane capillaries. These changes are noninflammatory and are frequently associated with congestive heart failure, hepatic cirrhosis, and nephrotic syndrome (i.e., hypoproteinemia). Once an effusion has been identified as a transudate, further laboratory testing usually is not necessary.

In contrast, exudates result from inflammatory processes that increase the permeability of the capillary endothelium in the parietal membrane or decrease the absorption of fluid by the lymphatic system. Numerous disease processes such as infections, neoplasms, systemic disorders, trauma, and inflammatory conditions may cause exudates. Additional laboratory testing is required with exudates, such as microbiological studies to identify pathologic organisms or cytologic studies to evaluate suspected malignant neoplasms.

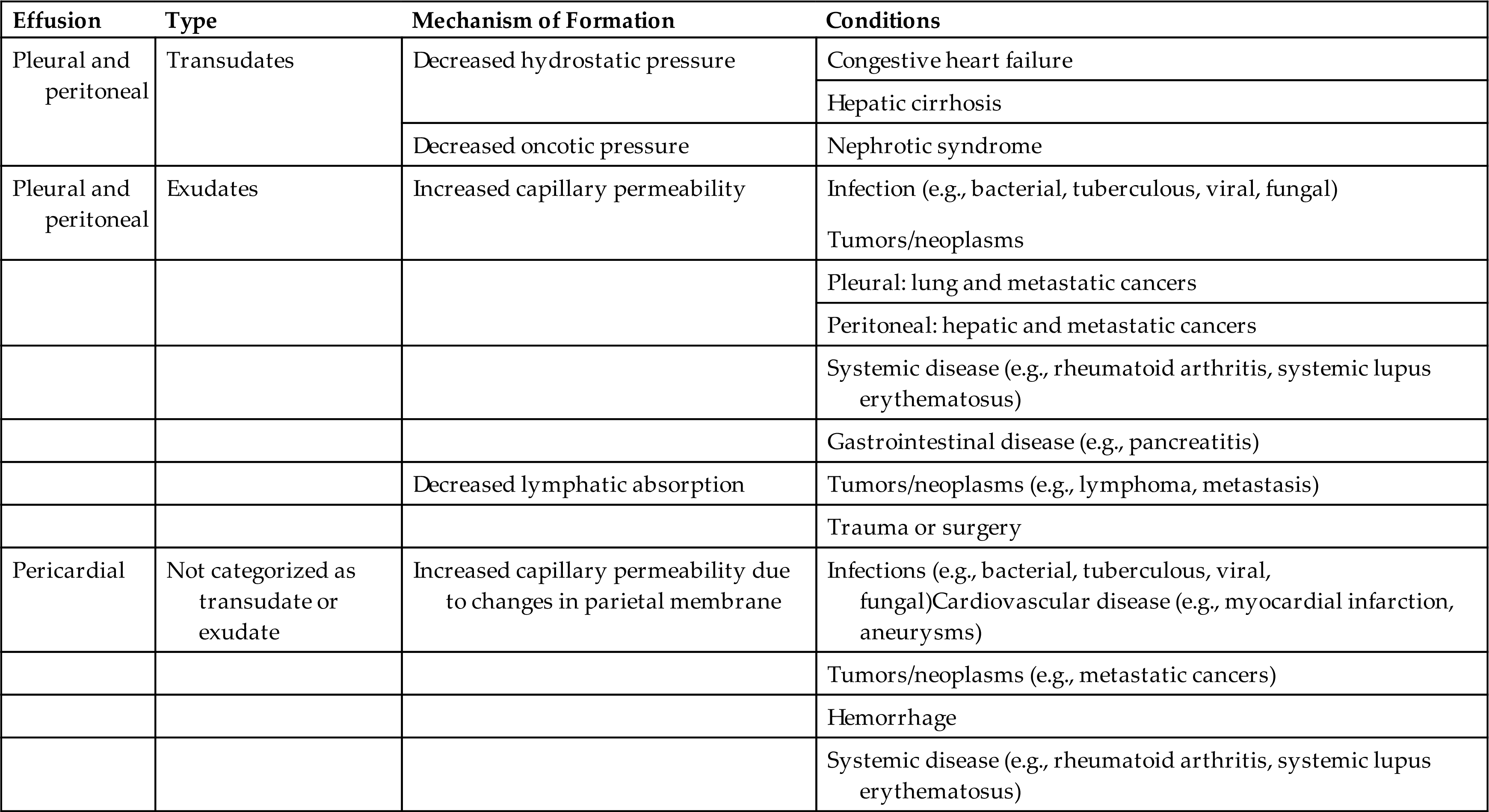

Table 10.3 summarizes various causes of pleural, pericardial, and peritoneal effusions. Unlike pleural and peritoneal effusions, pericardial effusions usually are not classified as a transudate or an exudate. Most often, pericardial effusions result from pathologic changes of the parietal membrane (e.g., because of infection or damage) that cause an increase in capillary permeability; hence the majority of pericardial effusions could be considered exudates.

Table 10.3

Physical Examination

Reference values for the characteristics of normal serous fluid in the pleural, pericardial, and peritoneal cavities are not available because in healthy individuals, the fluid volume in these cavities is small and the fluid is not normally collected. Only effusions are routinely collected and categorized as a transudate or an exudate (see Table 10.2). Transudates are usually clear fluids, pale yellow to yellow, that have a viscosity similar to that of serum. Because transudates do not contain fibrinogen, they do not spontaneously clot. In contrast, exudates are usually cloudy; vary from yellow, green, or pink to red; and may have a shimmer or sheen to them. Because exudates often contain fibrinogen, they can form clots, thus requiring an anticoagulant (e.g., EDTA, sodium heparin) in the collection tube. The physical appearance of an effusion usually is recorded on the patient’s chart by the physician after paracentesis and should be transcribed onto all test request forms. If this information is not provided, the laboratory performing the microscopic examination should document the physical characteristics of the fluid.

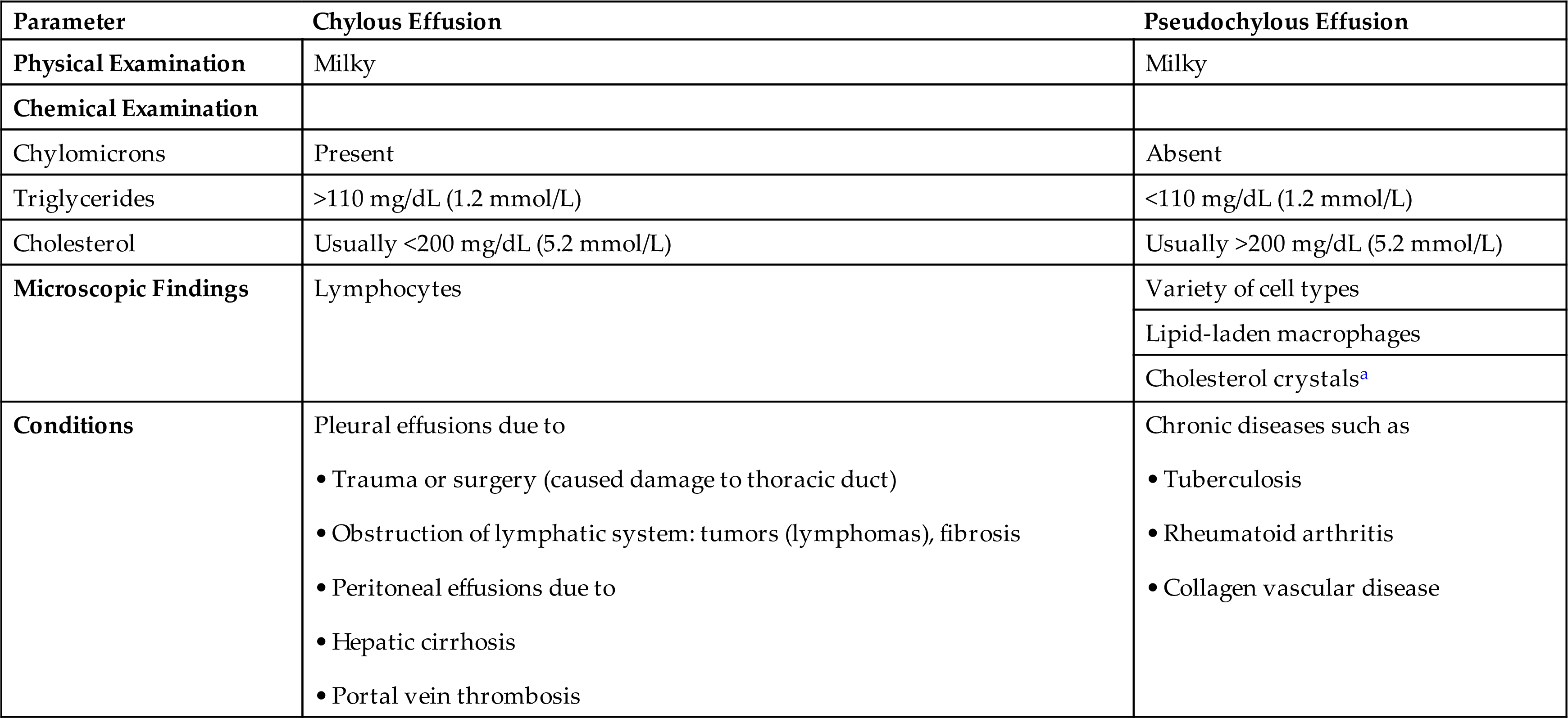

A cloudy paracentesis fluid most often indicates the presence of large numbers of leukocytes, other cells, chyle, lipids, or a combination of these substances. In pleural or peritoneal fluid, a characteristic milky appearance that persists after centrifugation usually indicates the presence of chyle (i.e., an emulsion of lymph and chylomicrons) in the effusion. A chylous effusion is caused by obstruction of or damage to the lymphatic system. In the pleural cavity, this can be caused by tumors, often lymphoma, or by damage to the thoracic duct due to trauma or accidental damage during surgery. Chylous effusions in the peritoneal cavity result from obstruction to lymphatic fluid drainage, which can occur with hepatic cirrhosis and portal vein thrombosis. Note that chronic effusions (as seen with rheumatoid arthritis, tuberculosis, and myxedema) can have a similar appearance, owing to the breakdown of cellular components; they also have a characteristically high cholesterol content. Consequently because of their visual similarity, chronic effusions are often called pseudochylous effusions and are differentiated from true chylous effusions by their lipid composition (i.e., triglycerides, chylomicron content). In a chylous effusion, lipoprotein analysis will show an elevated triglyceride level (i.e., greater than 110 mg/dL) and chylomicrons present, whereas a pseudochylous effusion has a low triglyceride level (less than 50 mg/dL) and no chylomicrons present. Table 10.4 summarizes the characteristics that assist in differentiating chylous and pseudochylous effusions.

Table 10.4

| Parameter | Chylous Effusion | Pseudochylous Effusion |

|---|---|---|

| Physical Examination | Milky | Milky |

| Chemical Examination | ||

| Chylomicrons | Present | Absent |

| Triglycerides | >110 mg/dL (1.2 mmol/L) | <110 mg/dL (1.2 mmol/L) |

| Cholesterol | Usually <200 mg/dL (5.2 mmol/L) | Usually >200 mg/dL (5.2 mmol/L) |

| Microscopic Findings | Lymphocytes | Variety of cell types |

| Lipid-laden macrophages | ||

| Cholesterol crystalsa | ||

| Conditions | Pleural effusions due to • Trauma or surgery (caused damage to thoracic duct) • Obstruction of lymphatic system: tumors (lymphomas), fibrosis |

Chronic diseases such as |

aPresence confirms or establishes fluid as pseudochylous effusion.

Blood can be present in transudates and exudates because of a traumatic paracentesis procedure. As with other body fluids (e.g., cerebrospinal fluid, synovial fluid), the origin of the blood is determined by the distribution of blood during paracentesis. If the amount of blood decreases during the collection and small clots form, a traumatic tap is suspected. If the blood is homogeneously distributed in the fluid and the fluid does not clot (indicating that the fluid has undergone fibrinolytic changes in the body cavity—a process that takes several hours), the patient has a hemorrhagic effusion.

Microscopic Examination

The microscopic examination of pleural, pericardial, and peritoneal fluids may include a total cell count of erythrocytes (red blood cells, RBCs) and leukocytes (white blood cells, WBCs), a nucleated cell differential count, cytology studies, and, at times, identification of crystals. Note that in contrast to cerebrospinal fluid, which is always present in the central nervous system regardless of health status, serous fluids (i.e., pleural, pericardial, peritoneal fluids) are normally not present in a sufficient amount in body cavities to be analyzed. In other words, their presence indicates a pathologic process; hence, there are no “normal” reference values for serous fluids.

As with other body fluids, cloudy effusions must be diluted for cell counting using normal saline or another suitable diluent. (See Appendix D for acceptable diluents and their preparation.) Acetic acid diluents are avoided because they cause cells to clump, which prevents accurate cell counting. Cell counts can be performed manually using a hemacytometer or an automated analyzer. For details, see Chapters 16 Chapter 16 Chapter 17 and 17.

In the microbiology laboratory, a Gram stain is performed on serous fluids when requested to aid in the microscopic identification of microbes (see subsection Microbiological Examination).

Total Cell Counts

Total RBC and WBC counts have little differential diagnostic value in the analysis of pleural, pericardial, and peritoneal fluids. No single value for a WBC count can be used reliably to differentiate transudates from exudates; hence these counts have limited clinical use. However, WBC counts in transudates are usually less than 1000 cells/μL, whereas those in exudates generally exceed 1000 cells/μL.

With pericardial fluid, a WBC count of greater than 1000 cells/μL is suggestive of pericarditis, whereas an RBC count or hematocrit of the fluid can assist in identifying a hemorrhagic effusion. With pleural fluid, RBC counts can also be used to identify hemorrhagic effusions. However, high RBC counts (greater than 10,000 cells/μL) are frequently associated with neoplasms or trauma of the pleura. With peritoneal fluid, a WBC count exceeding 500 cells/μL with a predominance of neutrophils (greater than 50%) suggests bacterial peritonitis. However, the volume of peritoneal fluid (or ascites) can change significantly because of extracellular fluid shifts, and these fluid shifts can significantly change the cell count obtained. Hence a wide range of WBC counts can be encountered in peritoneal effusions throughout the course of a disease.

Differential Cell Count

Microscope Slide Preparation

A cytocentrifuged-prepared smear of a body fluid is most often used to perform a differential cell count. Cytocentrifugation is easy and fast, and enables good cell recovery in a concentrated area of the microscope slide. Despite minimal cell distortion, some recognizable artifacts associated with cytocentrifugation are well known and they are listed in Box 17.4. For additional details on slide preparation, dilutions, and diluents, see Chapter 17, subsection “Body Fluid Analysis: Manual Hemacytometer Counts and Differential Slide Preparation.”

Low-Power Examination

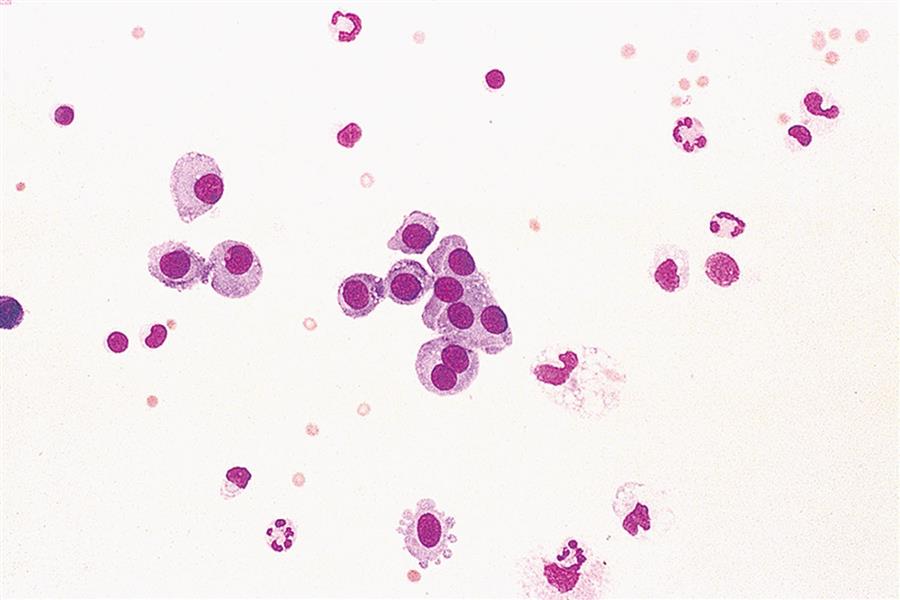

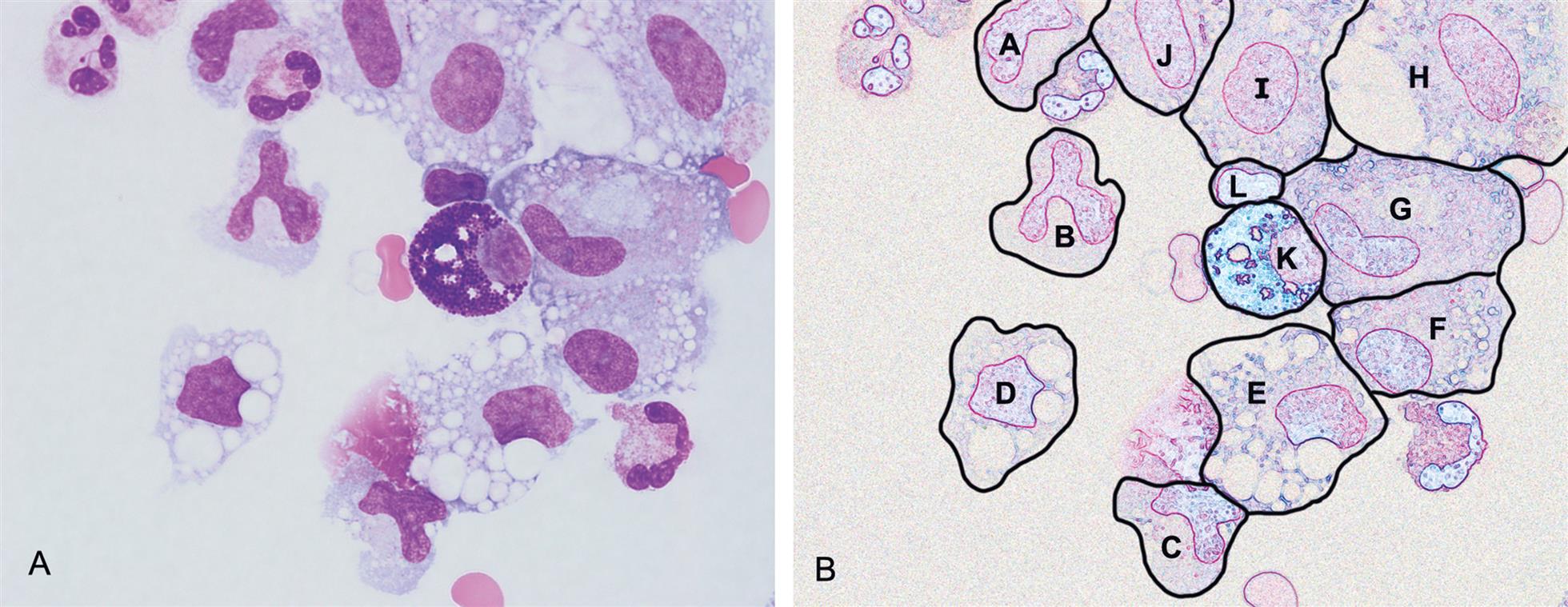

Each cytocentrifuged smear should be scanned in its entirety using a low-power objective (10 ×) to detect abnormalities that may be few in number yet apparent at this magnification, such as malignant cell clumps or other significant findings (see Fig. 9.4). In addition, this overview gives the microscopist a glimpse of the fluid’s composition, that is, its cellularity, density, and cell distribution on the slide (Fig. 10.2). Note that it does not matter whether this evaluation is done before or after the nucleated cell differential.

Nucleated Cell Differential

A differential nucleated cell count is performed using a high-power oil immersion objective (i.e., 50 × or 100 ×). The cell types that can be present in pleural, pericardial, and peritoneal fluids include granulocytes (i.e., neutrophils, eosinophils, basophils), lymphocytes, plasma cells, mononuclear phagocytes (i.e., monocytes, macrophages), mesothelial cells (lining cells of serous membranes), and malignant cells. Note that all nucleated cells are counted, including mesothelial cells and malignant cells.

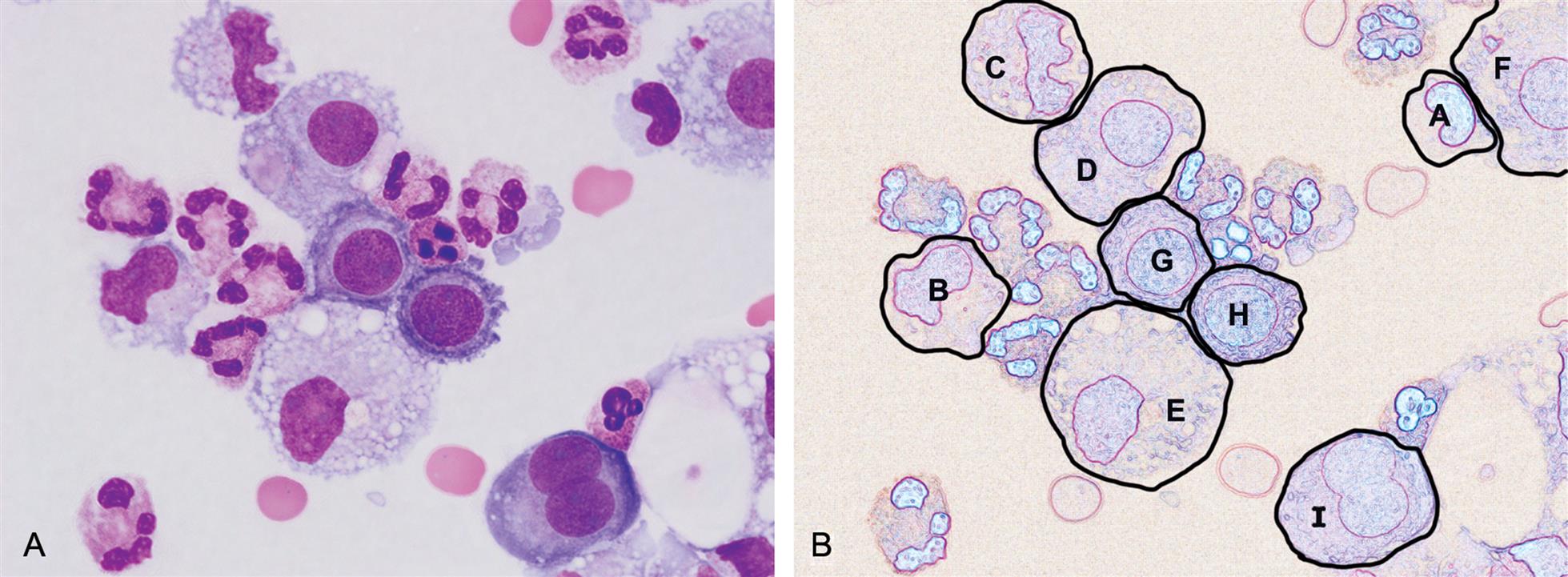

Monocytes, macrophages, and mesothelial cells

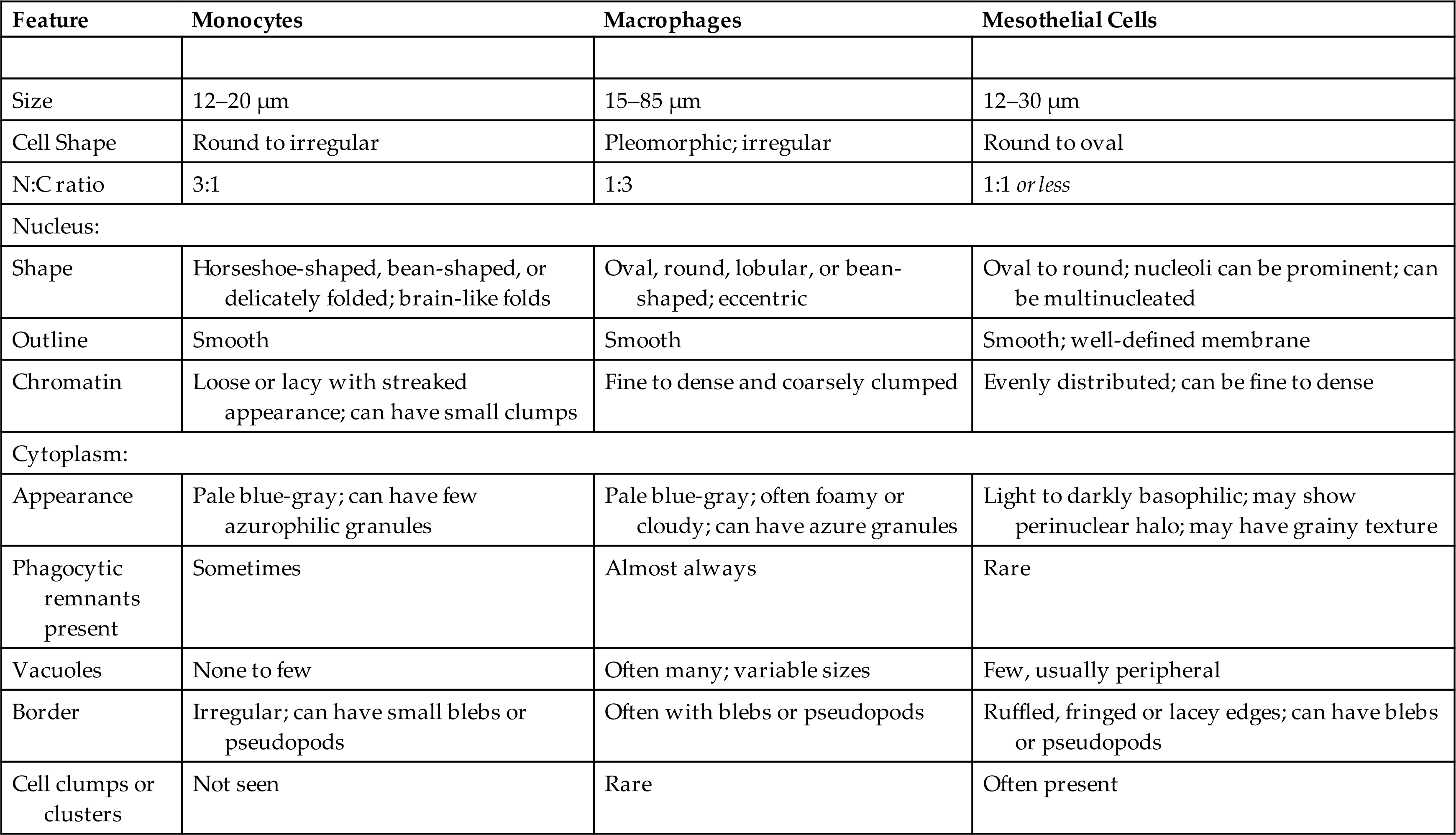

It is important to note that both monocytes and mesothelial cells can transform into macrophages. During this process, the visual appearance of intermediate “transitioning” cells can be very difficult to specifically identify (Figs. 10.3 and 10.4). Fortunately, because there is usually no clinical value in differentiating these three cell types (monocytes, macrophages, and mesothelial cells), they are often counted together in a single group or category.2 Despite this, when performing the nucleated cell count, some institutions choose to identify and report these cell types in two categories: monocytes/macrophages and mesothelial cells. Table 10.5 is provided as a guide for differentiating monocytes, macrophages, and mesothelial cells.

Table 10.5

| Feature | Monocytes | Macrophages | Mesothelial Cells |

|---|---|---|---|

| Size | 12–20 μm | 15–85 μm | 12–30 μm |

| Cell Shape | Round to irregular | Pleomorphic; irregular | Round to oval |

| N:C ratio | 3:1 | 1:3 | 1:1 or less |

| Nucleus: | |||

| Shape | Horseshoe-shaped, bean-shaped, or delicately folded; brain-like folds | Oval, round, lobular, or bean-shaped; eccentric | Oval to round; nucleoli can be prominent; can be multinucleated |

| Outline | Smooth | Smooth | Smooth; well-defined membrane |

| Chromatin | Loose or lacy with streaked appearance; can have small clumps | Fine to dense and coarsely clumped | Evenly distributed; can be fine to dense |

| Cytoplasm: | |||

| Appearance | Pale blue-gray; can have few azurophilic granules | Pale blue-gray; often foamy or cloudy; can have azure granules | Light to darkly basophilic; may show perinuclear halo; may have grainy texture |

| Phagocytic remnants present | Sometimes | Almost always | Rare |

| Vacuoles | None to few | Often many; variable sizes | Few, usually peripheral |

| Border | Irregular; can have small blebs or pseudopods | Often with blebs or pseudopods | Ruffled, fringed or lacey edges; can have blebs or pseudopods |

| Cell clumps or clusters | Not seen | Rare | Often present |

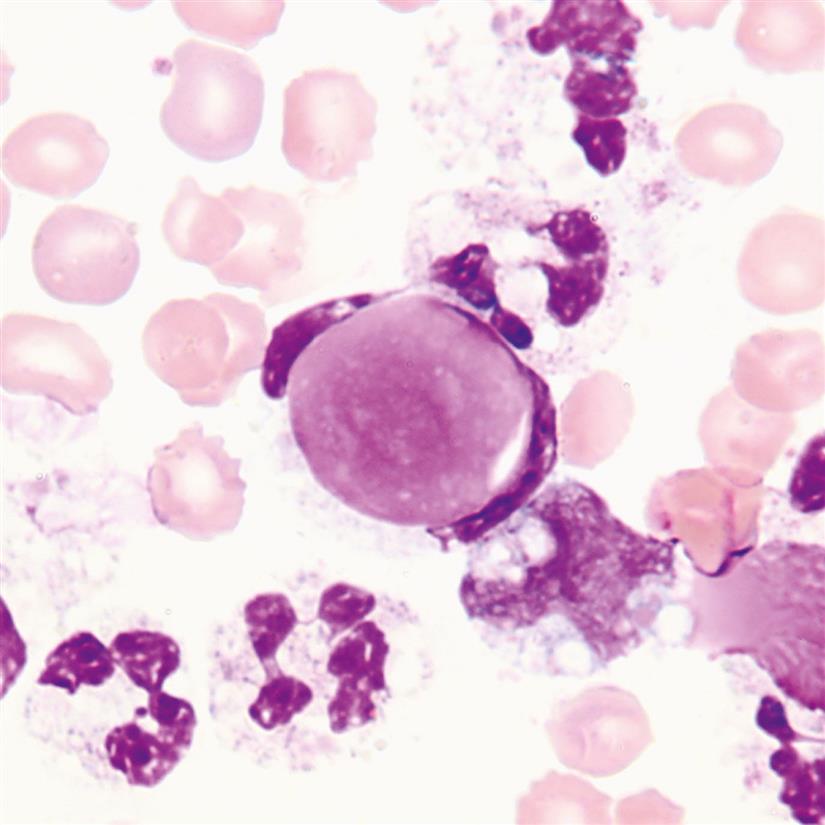

Monocytes move into body fluids from the bloodstream in response to inflammation and infection. These round or slightly irregular-shaped mononuclear cells are typically 12 to 20 μm in diameter (Fig. 10.3). The smooth-bordered nucleus is kidney bean or horseshoe–shaped and it can have delicate, brain-like folds. The nuclear chromatin appears loose with a lacy or streaked (i.e., raked, combed) appearance. The cytoplasm of monocytes is pale blue-gray and azurophilic granules may be present, although few in number. Monocytes can demonstrate blebs or pseudopods on their cytoplasmic borders. They may also have a few vacuoles or phagocytic remnants, but they do not form cell clumps.

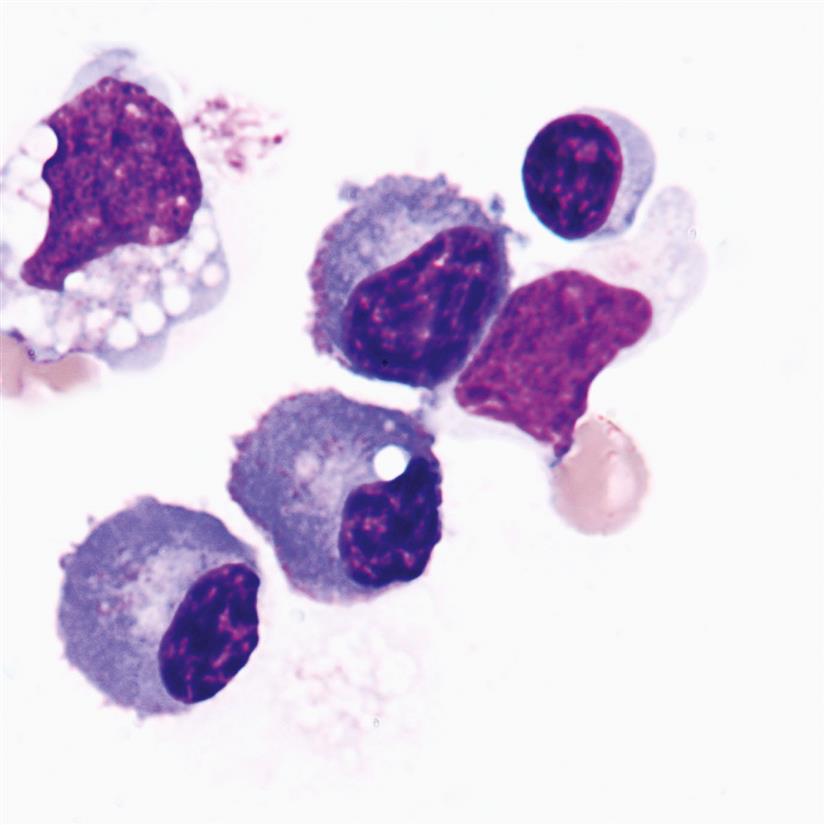

In serous body fluids, macrophages derive from either monocytes or mesothelial cells. They appear in a variety of irregular shapes (i.e., pleomorphic) and their size is highly variable, ranging from 12 to 85 μm in diameter (Figs. 10.3 and 10.4). Their oval or round nucleus is eccentric with a smooth border; it can also be lobular or bean-shaped. The nuclear chromatin can vary from fine to dense and may be coarsely clumped. The pale blue-gray cytoplasm often appears cloudy or foamy and azure granules can be present. These actively phagocytic cells have numerous vacuoles of varying sizes, and their cytoplasmic borders often have blebs or pseudopods present. At times during cell transformation to a macrophage, it is difficult to distinguish whether the cell is a monocyte or a macrophage, in which case they are identified and enumerated in a “monocyte-macrophage” category.

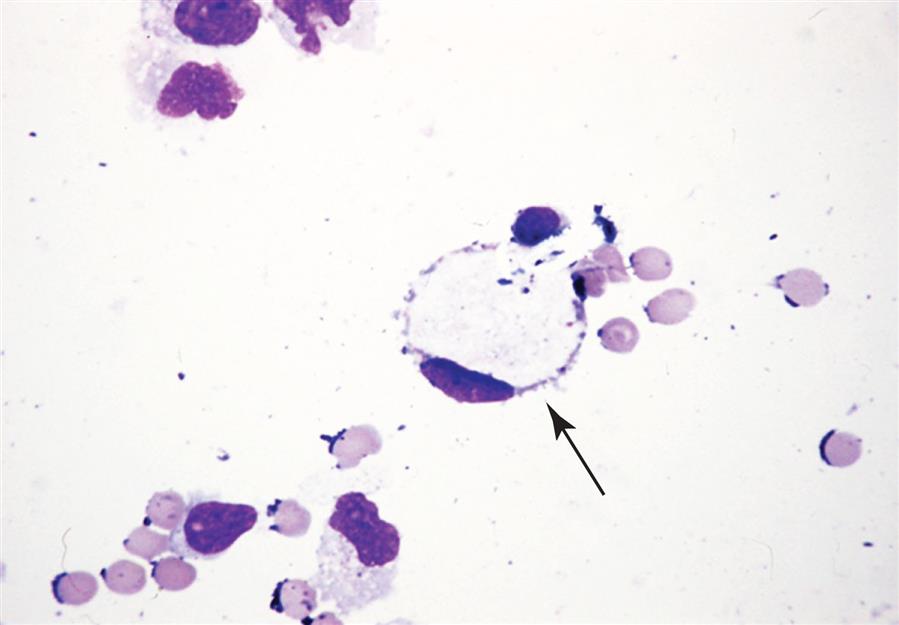

Macrophages can also be descriptively named based on the type of inclusions within them (as discussed in Chapter 9, section Cerebrospinal Fluid). Erythrophages (macrophages with RBC inclusions) and siderophages (macrophages with hemosiderin inclusions) are associated with hemorrhage into a body cavity (see Figs. 9.10–9.12). When numerous neutrophils are present in a body fluid, macrophages can ingest them. These neutrophages will contain one or several neutrophils in various stages of degeneration and are associated with acute inflammation. Although lipophages (macrophages with numerous small, clear, lipid-containing vacuoles) may be seen in pleural and pericardial fluids, they are more often seen in the cerebrospinal fluid (see Fig. 9.13) and synovial fluids.

In a macrophage, several vacuoles can merge together to form a single large vacuole. When this occurs, the nucleus becomes pressed against the cell membrane and because of their appearance, these cells are sometimes called “signet ring” macrophages (Fig. 10.5). However, it is important that these macrophages are not confused with signet ring carcinoma, an adenocarcinoma of glandular epithelial cells most often of the stomach. Therefore, to reduce confusion for clinicians, the term signet ring should not be used when reporting macrophages in serous fluids.

A detailed discussion of the formation of these various macrophages is provided in Chapter 9, section Macrophages. Note that because macrophages are counted collectively in a monocyte/macrophage/mesothelial cell category, some institutions append a comment to the report that indicates the descriptive type of macrophages present, for example, “many erythrophages present, rare siderophage present.”

Mesothelial cells are the lining cells of serous membranes and are routinely sloughed off. Hence, they are often seen in effusions. These cells are 20 to 50 μm in diameter, with light gray to deep blue staining cytoplasm that can appear grainy (Fig. 10.6). Their nuclei may be eccentric with smooth, regular borders and they can be multinucleated (see Fig. 10.3). The nuclear chromatin is evenly distributed and can be fine or dense; one to three nucleoli may be present. Because mesothelial cells can show a perinuclear halo, they sometimes resemble plasma cells (Fig. 10.7), which can also be in pleural and peritoneal fluids.

Mesothelial cells have ruffled or fringed cytoplasmic borders that can form blebs or pseudopods (see Fig. 10.3). They can have a few small vacuoles which, when present, are usually located at the cell’s periphery. In serous body fluids, mesothelial cells appear singly and as cell clumps. Therefore, it is imperative that when cell clumps are present they are correctly identified and distinguished from malignant cells. Note that as mesothelial cells transform into macrophages, their cytoplasm becomes less basophilic and more vacuolated, giving it a foamy appearance.

Granulocytes

Conditions associated with an increase in granulocytes, lymphocytes, and plasma cells in serous fluids are varied and briefly listed in Table 10.6. Neutrophils, when present in large numbers, suggest an infection but they could originate from blood contamination. Infections include peritonitis, pericarditis, bacterial pneumonia, and fungal infections. Although rare, lupus erythematosus (LE) cells (i.e., neutrophils with a phagocytized homogeneous nucleus) may be present in fluids from patients with systemic lupus erythematosus, a chronic autoimmune disorder (Fig. 10.8).

Table 10.6

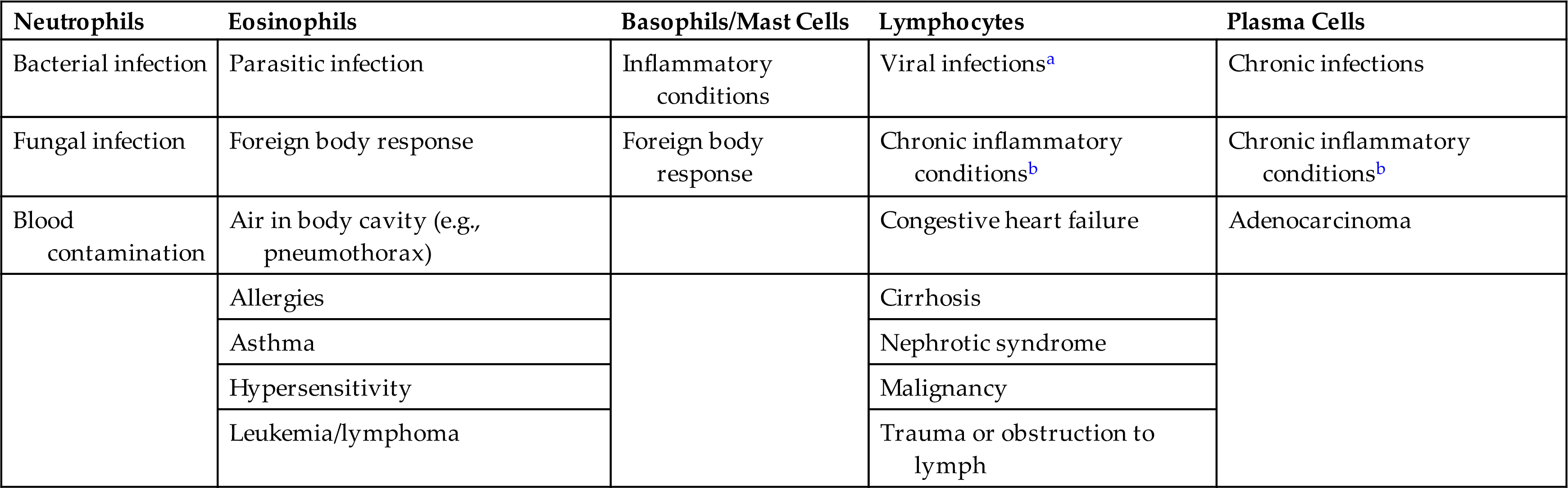

| Neutrophils | Eosinophils | Basophils/Mast Cells | Lymphocytes | Plasma Cells |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bacterial infection | Parasitic infection | Inflammatory conditions | Viral infectionsa | Chronic infections |

| Fungal infection | Foreign body response | Foreign body response | Chronic inflammatory conditionsb | Chronic inflammatory conditionsb |

| Blood contamination | Air in body cavity (e.g., pneumothorax) | Congestive heart failure | Adenocarcinoma | |

| Allergies | Cirrhosis | |||

| Asthma | Nephrotic syndrome | |||

| Hypersensitivity | Malignancy | |||

| Leukemia/lymphoma | Trauma or obstruction to lymph |

aViral infections include infectious mononucleosis, viral hepatitis, viral pneumonia, cytomegalovirus infection, etc.

bChronic inflammatory conditions include tuberculosis, rheumatoid arthritis, collagen vascular disease, etc.

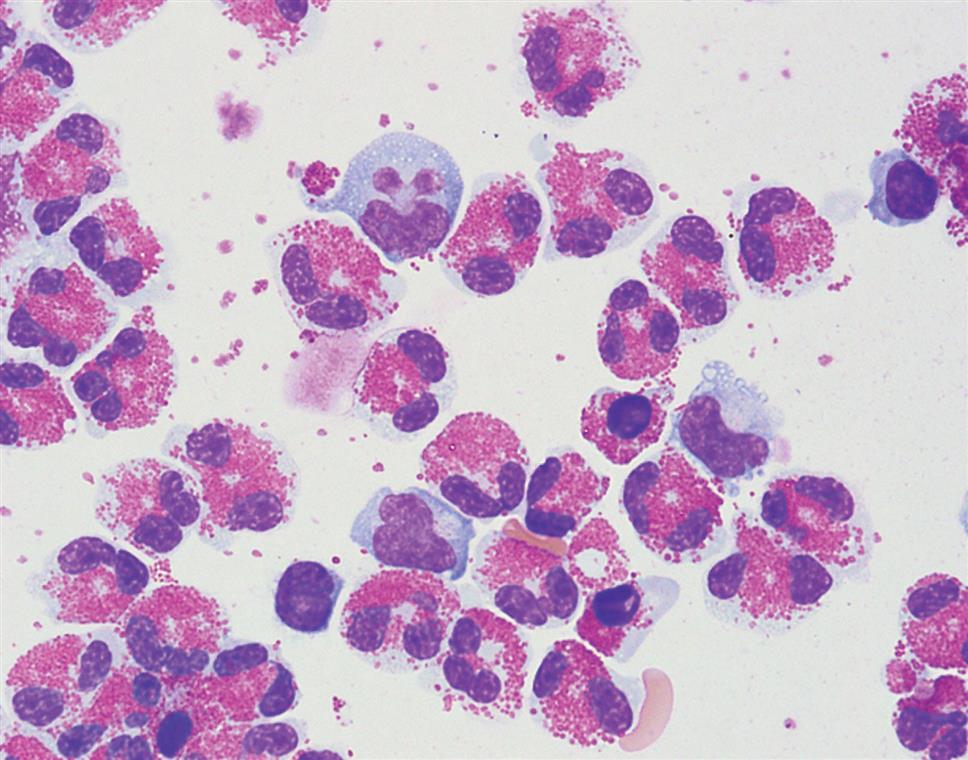

Eosinophilia, when the eosinophil count is greater than 10%, can accompany a variety of conditions, such as parasitic infections, foreign body response (e.g., shunts, chest tubes, peritoneal dialysis), allergies, air in the body cavity (e.g., pneumothorax), leukemias, lymphoma, and others (Fig. 10.9).

Basophils and mast cells can look similar but are actually derived from different cell precursors. A mast cell is usually larger than a basophil and its nucleus is round compared with the segmented nucleus of a basophil. Both cells have numerous blue-black cytoplasmic granules that can fill the cell such that it is difficult to see the nucleus. There is a greater density of these granules in a mast cell compared with a basophil. The peritoneal fluid in Fig. 10.4 shows a mast cell based on its round, eccentric nucleus. It is unusual to see basophils or mast cells in serous fluids. However, they often accompany eosinophilia (e.g., parasitic infections), are associated with a foreign body response (e.g., peritoneal dialysis), and may be encountered in other inflammatory conditions.

Lymphocytes and plasma cells

Lymphocytes can be seen in all body fluids. They often vary both in the number present and in their size. Note that lymphocytes transform in response to various stimuli. Consequently, a spectrum of different types of lymphocytes can be encountered in a single body fluid. Small lymphocytes (7–12 μm) have a small to moderate amount of light blue cytoplasm; a round to oval nucleus; and condensed, dark-staining chromatin (Figs. 10.2, 10.4, 10.7, and 10.9). A few small azurophilic granules may be present in the cytoplasm. In comparison, large lymphocytes are 12 to 18 μm in diameter, primarily due to a larger amount of cytoplasm. Reactive lymphocytes are usually the largest lymphocytes, typically 10 to 30 μm in diameter, with moderate to abundant cytoplasm. The cytoplasm can be pale to dark blue, and in some cells the cytoplasm stains darker blue at the periphery with a light area or zone near the nucleus, resembling a plasma cell. The nucleus of reactive lymphocytes is larger and the nuclear chromatin less basophilic compared with smaller lymphocytes, and several nucleoli may be prominent. Reactive lymphocytes accompany other inflammatory cells and are frequently observed molding around RBCs and other cells in the cytocentrifuged smear.

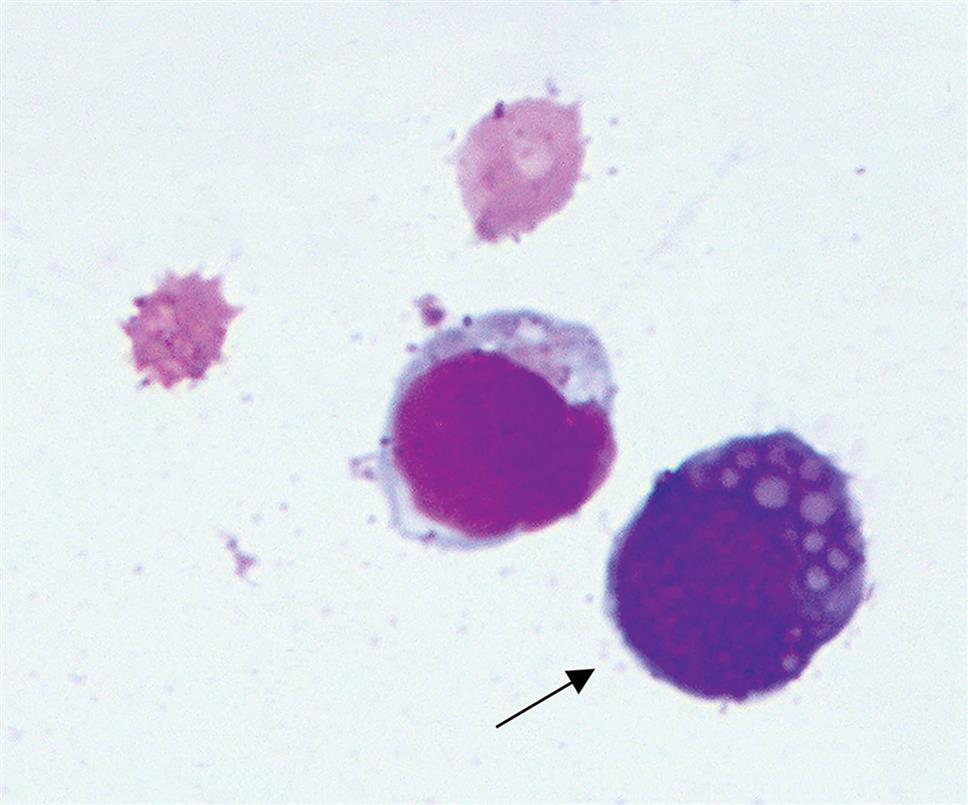

Note that lymphocytes also transform under various stimuli to form mature plasma cells. As this process occurs, various intermediate cell types are formed: reactive lymphocytes, plasmacytoid lymphocytes, and immunoblasts. When mature, a plasma cell is 8 to 20 μm in diameter and has an eccentric round or oval nucleus with no nucleoli and coarsely clumped chromatin. Sometimes the chromatin takes on a “clock-face” pattern. Plasma cells can be binucleated and rarely multinucleated. Their moderate to abundant cytoplasm has no granulation and stains moderate to dark blue with a light area or clear zone called a “hof” next to the nucleus (Fig. 10.7). Vacoules may or may not be present.

In response to infections, inflammation, or malignancy, plasma cells can produce antibodies. These plasma cells, also called “Mott” cells, have vacuoles that contain immunoglobulin proteins. Their cytoplasm is usually dark blue with a tinge of pink (Fig. 10.10).

Malignant cells.

Malignant cells are common in effusions from patients with neoplastic disease. However, the number of malignant cells found in body fluids can vary dramatically, which highlights the importance of the low-power examination of an entire cytocentrifuged smear to search for any rare malignant cells or cell clumps.

The morphology of malignant cells can be divided into two types: monomorphic (i.e., cells that show no variation in morphology; all cells look alike) and pleomorphic (numerous variations in cellular morphology). A variety of morphologic features are associated with malignant cells, and the most common are listed in Box 10.2. At times, the changes observed can be obvious, with cells looking extremely bizarre and atypical; other times, the changes may not be as recognizable. Malignant characteristics include a high nucleus-to-cytoplasmic (N:C) ratio and changes in the nucleus size, shape, and appearance. Nucleoli are atypically large and irregular in shape, and there are changes in the chromatin density and distribution. Cells can be oddly multinucleated, with the various nuclei differing in size and shape within a single cell. Nuclear molding, where the nucleus of one cell indents the nucleus of another cell, can produce unusual cell clusters that are usually detectable using low-power magnification. Lastly, a feature of malignancy that may be observed is cytoplasmic granules, that is, the cells have large clumps of prominent granules that are normally not present. It can be very difficult to discern between normal and malignant cells; therefore always consult a pathologist whenever suspicious cells are observed in a body fluid. This professional interaction provides an opportunity for learning and team building in the laboratory. For example, reactive and malignant mesothelial cells can be very difficult to differentiate in cases of malignant mesothelioma.

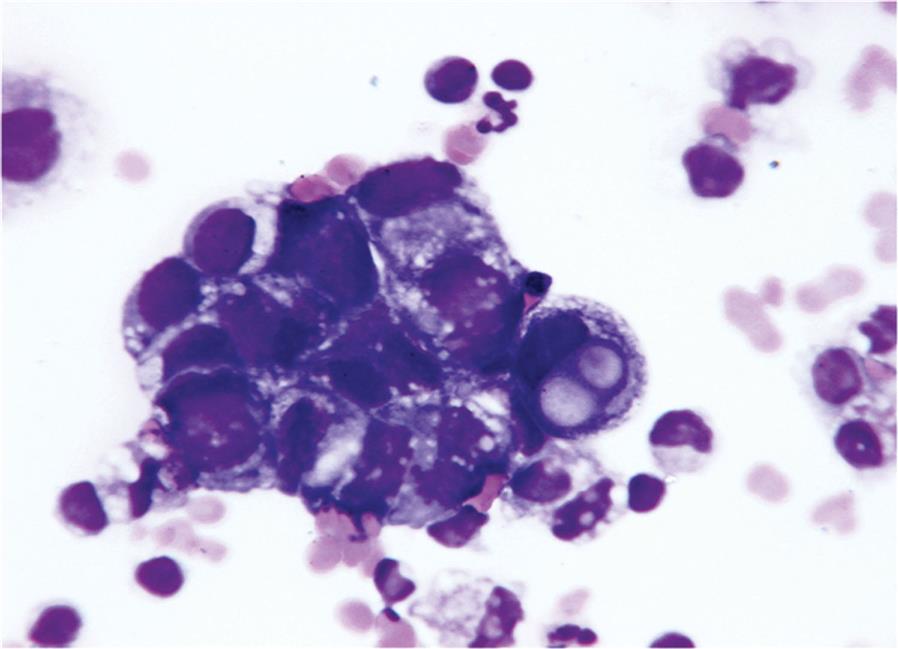

Most malignant effusions are caused by metastatic adenocarcinomas (Fig. 10.11). However, any of the blood cancers, leukemias, or lymphomas can infiltrate body cavities to cause an effusion. In these cases, the use of immunocytochemistry and flow cytometry is valuable in determining an accurate diagnosis. In summary, proper identification of malignant cells in body fluids by a skilled professional (e.g., pathologist, cytologist) is crucial and is performed when a smear is forwarded for review or when a cytologic examination is specifically requested.

Clinical Value of the Nucleated Cell Differential

The clinical value of a nucleated cell differential varies with the origin of the paracentesis fluid. In pleural fluid, neutrophils predominate in about 90% of effusions caused by acute inflammation (i.e., exudates). Lymphocytes predominate in 90% of effusions caused by tuberculosis, neoplasms, and systemic diseases. Similarly, in peritoneal fluid, neutrophils predominate (greater than 25%) in most exudates, suggesting bacterial infection. In peritoneal transudates and in exudates caused by decreased lymphatic absorption (e.g., tuberculosis, neoplasms, lymphatic obstruction), lymphocytes predominate. Pericardial fluid differential counts are often not performed because a variety of conditions (e.g., bacterial and viral pericarditis, postmyocardial infarction) can produce the same cell differential; hence, a pericardial fluid differential count provides little diagnostic information.

Cytologic Examination

When malignant disease is suspected, large volumes (10–200 mL) of the pleural, pericardial, or peritoneal effusion should be submitted for cytologic examination. The fluid should be concentrated to increase the yield of cells, and a cell block and cytocentrifuged smears can be prepared. Cytologic examination is an important, sensitive, and specific procedure in the diagnosis of primary and metastatic neoplasms and is performed by a cytologist or a pathologist.

Chemical Examination

The chemistry tests selected to evaluate pleural, pericardial, and peritoneal fluids assist the physician in establishing or confirming a diagnosis for the cause of an effusion. Once a diagnosis has been established, appropriate treatment can be initiated, and further testing usually is not required. A specific diagnosis based on laboratory findings from serous fluids is limited to (1) malignancy, when malignant cells are recovered and identified; (2) systemic lupus erythematosus, when characteristic lupus erythematosus cells are found during the microscopic examination; and (3) infectious disease, when microorganisms (e.g., bacteria, fungi) are identified by Gram stain or culture. Several disease processes can occur simultaneously, each contributing to the development of an effusion. Therefore chemistry tests initially classify the effusion as a transudate or an exudate. Transudates usually require no further chemical analysis, whereas exudates are tested further to identify their causative agents or cause. A systematic approach in serous fluid testing greatly facilitates the diagnostic process.

Total Protein and Lactate Dehydrogenase Ratios

No single test can identify specifically the disease process causing effusions in the pleural, pericardial, and peritoneal cavities. Historically, transudates and exudates were classified by the total protein (TP) content or specific gravity of the fluid alone. Because of the significant overlap noted when these criteria were used (i.e., exudates with protein content or specific gravity values that were equivalent to those of transudates and vice versa), a better discriminator was needed. Useful tests for classifying a serous fluid as a transudate or an exudate are simultaneous determinations of the serum and serous fluid TP concentration and lactate dehydrogenase (LD) activity. From these values, the fluid-to-serum TP ratio and the fluid-to-serum LD ratio can be determined as follows:

Equation 10.1

Equation 10.1 Equation 10.2

Equation 10.2These ratios together provide a reliable means to distinguish a transudate from an exudate. If the TP ratio is less than 0.5 and the LD ratio is less than 0.6, the fluid is classified as a transudate. In contrast, exudates are those fluids with a TP ratio greater than 0.5, a LD ratio greater than 0.6, or both.

Glucose

Once a fluid has been classified as an exudate, several chemical tests can be used for further evaluation. The tests selected and their usefulness vary with the origin of the fluid. The simultaneous measurement of serum and serous fluid glucose concentrations has limited value. If the serous fluid glucose is less than 60 mg/dL or if the glucose difference between serum and fluid is greater than 30 mg/dL, an exudative process is identified. Only low fluid glucose levels are clinically significant, and a variety of disease processes are associated with them, particularly rheumatoid arthritis. Other conditions such as bacterial infection, tuberculosis, and malignant neoplasm may also present with decreased fluid glucose levels; however, a normal serous fluid glucose value does not rule out these disorders.

Amylase

The determination of simultaneous serum and fluid amylase levels, particularly in pleural and peritoneal fluids, is clinically useful and has become routine in many laboratories. A serous fluid amylase value that exceeds the established upper limit of normal (for serum specimens) or is 1.5 to 2 times the serum value is considered abnormally increased.5 These high fluid amylase levels most often occur in effusions caused by pancreatitis, esophageal rupture (salivary amylase), gastroduodenal perforation, and metastatic disease.

Lipids (Triglyceride and Cholesterol)

Because identification of a chylous effusion is clinically significant, determining the triglyceride level of a fluid is an important adjunct when evaluating serous fluids. The milky appearance of an effusion does not identify it specifically as a chylous effusion because pseudochylous effusions can have a similar appearance. Therefore fluid triglyceride levels are used as an additional determining factor. A serous fluid triglyceride value that is greater than 110 mg/dL (1.2 mmol/L) indicates a chylous effusion, whereas a triglyceride value of less than 50 mg/dL rules it out. If the triglyceride level is between 50 and 110 mg/dL, lipoprotein electrophoresis can be performed; the presence of chylomicrons identifies a chylous effusion, whereas the absence of chylomicrons indicates a pseudochylous effusion. Chylous effusions are associated with obstruction or damage to the lymphatic system, which can occur with neoplastic disease (e.g., lymphoma), trauma, tuberculosis, and surgical procedures. Pseudochylous effusions are most often encountered with chronic inflammatory conditions (e.g., rheumatoid arthritis). Note that the presence of cholesterol crystals in a serous fluid is diagnostic of a pseudochylous effusion.6

The cholesterol level of pleural fluid can be useful for differentiating between a chylous and a pseudochylous effusion. A fluid-to-serum cholesterol ratio of greater than 1.0 indicates a pseudochylous effusion. The cholesterol ratio can also be helpful in identifying a pleural effusion as a transudate or exudate when other chemical results (TP ratio, LD ratio) are equivocal. In these cases, a fluid-to-serum cholesterol ratio of greater than 0.3 indicates an exudate.6,7

pH

With pleural fluid, an abnormally low pH value can help identify patients with parapneumonic effusions (i.e., exudates caused by pneumonia or lung abscess) that require aggressive treatment. Parapneumonic effusions can involve the parietal and visceral membranes, produce pus, and loculate in the pleural cavity. Studies show that if the pleural fluid pH is less than 7.30, despite appropriate antibiotic therapy, the placement of drainage tubes is necessary for resolution of the effusion. In contrast, if the pleural fluid pH exceeds 7.30, the effusion completely resolves after antibiotic treatment alone. An important note is that the collection of pleural fluid specimens for pH measurement requires the same rigorous sampling protocol as the collection of arterial blood gas specimens (i.e., an anaerobic sampling technique using a heparinized syringe, placing the specimen on ice, and immediately transporting it to the laboratory for analysis).

Pericardial and peritoneal fluid pH measurements currently have no clearly established clinical value.

Carcinoembryonic Antigen

The measurement of carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA), a tumor marker, is useful in evaluating pleural and peritoneal effusions from patients who have a previous history or are currently suspected of having a carcinoembryonic antigen–producing tumor. When a CEA measurement is combined with a fluid cytologic examination, the identification of malignant effusions is significantly increased.

Microbiological Examination

Staining Techniques

Microbiological examination includes the preparation of smears using a concentrated or cytocentrifuged specimen for immediate identification of microorganisms. Depending on the suspected diagnosis, this may include Gram stain, an acid-fast stain, and other staining techniques. The sensitivity of these techniques depends on two factors: (1) the appropriate collection, processing, and handling of the fluid specimen, and (2) the technical competence of the microscopist reading the smears. If either aspect is substandard, optimal results will not be obtained. In fluid specimens that have been allowed to clot, microorganisms can be caught in the clot matrix and obstructed from view; similarly, contamination of the specimen during its collection or delays in handling and processing can yield false-positive results from in vitro bacterial proliferation. Because of the potential presence of stain precipitates, cellular components, and other debris, smears must be evaluated by appropriately trained and experienced laboratorians. Under the best conditions, a Gram stain is positive in about 30% to 50% of bacterial effusions, whereas acid-fast stains are positive in only 10% to 30% of tuberculous effusions.

Culture

As with smear preparations, the larger the volume of pleural, pericardial, or peritoneal fluid used or the more concentrated the inoculum used, the greater the chances of obtaining a positive culture. Both aerobic and anaerobic cultures should be performed. The sensitivity of a positive culture varies with the origin of the fluid and the organism present. Positive bacterial cultures are obtained in approximately 80% of all bacterial effusions. In contrast, peritoneal tuberculous (or mycobacterial) effusions culture positive in 50% to 70% of cases, pericardial effusions culture positive in about 50% of cases, and pleural tuberculous effusions culture positive in only about 30% of cases.

Study Questions

- 1. Which of the following statements about serous fluid–filled body cavities is true?

- 1. A parietal membrane is attached firmly to the body cavity wall.

- 2. Serous fluid acts as a lubricant between opposing membranes.

- 3. A serous membrane is composed of a single layer of flat mesothelial cells.

- 4. The visceral and parietal membranes of an organ are actually a single continuous membrane.

- 5. Paracentesis and serous fluid testing are performed to

- 6. Thoracentesis refers specifically to the removal of fluid from the

- 7. Which of the following tubes could be used for a bacterial culture of serous fluid?

- 8. Serous fluid for bacterial culture should be stored at

- 9. Which of the following parameters best identifies a fluid as a transudate or an exudate?

- 10. Chylous and pseudochylous effusions are differentiated by their

- 11. Which of the following conditions is most often associated with the formation of a transudate?

- 12. Match the type of serous effusion most often associated with each pathologic condition.

- 13. Which of the following features is not a characteristic of malignant cells?

- 14. Which of the following laboratory findings on an effusion does not indicate a specific diagnosis?

- 15. An abnormally low fluid pH value is useful when evaluating conditions associated with

- 16. A pleural or peritoneal fluid amylase level two times higher than the serum amylase level can be found in effusions resulting from

- 17. A glucose concentration difference greater than 30 mg/dL between the serum and an effusion is associated with

- 18. Which of the following actions can adversely affect the chances of obtaining a positive stain or culture when performing microbiological studies on infectious serous fluid?