Normal Gait

Michael Whittle, David Levine and Jim Richards

To understand pathological gait, it is necessary first to understand the gait of healthy, pain-free individuals, which for ease we will refer to as ‘normal gait, within normal limits,’ since this provides the standard against which the gait of a patient can be judged. However, there are pitfalls which need to be considered when using this approach. Firstly, the term normal covers both genders, a wide range of ages and an even wider range of extremes of body geometry, so an appropriate ‘normal’ standard needs to be chosen for the individual being studied. If results from an elderly female patient are compared with normal data obtained from physically fit young males, there will undoubtedly be large differences, whereas comparison with data from healthy elderly females may show the patient’s gait to be well within normal limits appropriate for her gender and age. Another pitfall is that even though a patient’s gait differs from normal, it may not be undesirable, and efforts to turn it into a normal gait should not be made. Many gait abnormalities are a compensation for some problem experienced by the patient and, although abnormal, are nonetheless useful. Having said this, it is very important to understand normal gait and the terminology used to describe it, before looking at pathological gait. This chapter starts with a brief historical review and then gives an overview of the gait cycle, before going on to study in detail how the different parts of the locomotor system are used in walking.

Walking and Gait

Normal human walking and running can be defined as ‘a method of locomotion involving the use of the two legs, alternately, to provide both support and propulsion’. In order to exclude running, we must add ‘at least one foot being in contact with the ground at all times’. Unfortunately, this definition excludes some forms of pathological gait which are generally regarded as forms of walking, such as the three-point step-through gait (see Fig. 3.21), in which there is an alternate use of two crutches and either one or two legs. It is both unreasonable and pointless to attempt a definition of walking which will apply to all cases, at least in a single sentence!

Gait is no easier to define than walking, with many dictionaries regarding it as a word primarily for use in connection with horses! This is understandable, since quadruped animals have a repertoire of natural gaits (walking, trotting, pacing, galloping, etc.), as well as some artificial ones such as that learned by Tennessee Walking Horses in the area where one of the authors lives. Most people tend to use the words gait and walking interchangeably. However, there is a difference: the word gait describes the manner or style of walking rather than the walking process itself. It thus makes more sense to talk about a difference in gait between two individuals than about a difference in walking.

A Brief History

Walking has undoubtedly been observed since the dawn of humanity, but the systematic study of gait appears to date from the Renaissance when Leonardo da Vinci, Galileo and Newton gave useful descriptions of walking. The earliest account using a scientific approach was in the classic book De Motu Animalium, published in 1682 by Borelli, who worked in Italy and was a student of Galileo. Borelli measured the centre of gravity of the body and described how balance is maintained in walking by constant forward movement of the supporting area provided by the feet. The Weber brothers in Germany gave the first clear description of the gait cycle in 1836. They made accurate measurements of the timing of gait and of the pendulum-like swinging of the leg of a cadaver.

Kinematics

Two pioneers of kinematic measurement worked on opposite sides of the Atlantic in the 1870s. Marey, working in Paris, published a study of human limb movements in 1873. He made multiple photographic exposures, on a single plate, of a subject who was dressed in black, except for brightly illuminated stripes on the limbs. He also investigated the path of the centre of gravity of the body and the pressure beneath the foot. Eadweard Muybridge (born in England as Edward Muggeridge) became famous in California in 1878 by demonstrating that, when a horse is trotting, there are times when it has all four feet off the ground at once. The measurements were made using 24 cameras, triggered in quick succession as the horse ran into thin wires stretched across the track. In the next few years, Muybridge made a further series of studies, of naked human beings walking, running and performing a surprising variety of other activities!

The most serious application of the science of mechanics to human gait during the 19th century was the publication in Germany, in 1895, of Der Gang des Menschen, by Braune and Fischer. They employed a technique similar to Marey’s, but using fluorescent striplights on the limbs instead of white stripes. The resultant photographs were used to determine the three-dimensional trajectories, velocities and accelerations of the body segments. Knowing the masses and accelerations of the body segments, they were then able to estimate the forces involved at all stages during the walking cycle.

Further valuable work on the dynamics of locomotion was done by Bernstein in Moscow in the 1930s. He developed a variety of photographic techniques for kinematic measurement, paying particular attention to the centre of gravity of the individual limb segments and of the body as a whole.

Force Platforms

Further progress followed the development of the force platform (also called the force plate). This instrument has contributed greatly to the scientific study of gait and is now standard equipment in gait laboratories. It measures the direction and magnitude of the ground reaction force beneath the foot. An early design was described by Amar in 1924 and an improved one by Elftman in 1938. Both were purely mechanical, with the force applied to the platform causing the movement of a pointer.

Muscle Activity

For a full understanding of normal gait, it is necessary to know which muscles are active during the different parts of the gait cycle. The role of the muscles was studied by Scherb, in Switzerland, during the 1940s, initially by palpating the muscles as his subject walked on a treadmill, then later using electromyography (EMG). Further advances in the understanding of muscle activity and many other aspects of normal gait were made during the 1940s and 1950s by a group working at the University of California at San Francisco and the University of California at Berkeley, notable among whom was Verne Inman. This group wrote Human Walking (Inman et al., 1981), which was published just after Inman’s death and to many is the definitive textbook on normal gait. Human Walking has gone through several editions, with the latest by Rose and Gamble (2005). Another classic text on EMG is Muscles Alive: Their Functions Revealed by Electromyography, by John Basmajian and Carlo De Luca (Basmajian and De Luca, 1985). Although this text has not been updated since 1985, The Comprehensive Textbook of Clinical Biomechanics (Richards, 2018) contains a useful summary chapter by De Luca and colleagues.

The use of EMG in gait analysis has received much attention, but perhaps the most influential paper published was ‘The use of surface electromyography in biomechanics’ by Carlo De Luca (De Luca, 1997), which gave a summary of recommendations but perhaps more importantly a summary of problems which at the time needed resolution. Further standardisation was achieved through the SENIAM (Surface ElectroMyoGraphy for the Non-Invasive Assessment of Muscles) project coordinated and managed by Hermie Hermens and Bart Freriks from Enschede, which is now considered by many to be the definitive recommendations for and sensor positioning for specific muscles.

Mechanical Analysis

A major contribution to the mechanical analysis of walking, also from the California group, was made by Bresler and Frankel (1950). They performed free-body calculations for the hip, knee and ankle joints, allowing for ground reaction forces, the effects of gravity on the limb segments and the inertial forces. The analytical techniques developed by these workers formed the basis of many current methods of modelling and analysis.

An important paper describing the possible mechanisms which the body uses to minimise energy consumption in walking was published by Saunders et al. (1953). Further important work on energy consumption and, in particular, the energy transfers between the body segments in walking was published by Cavagna and Margaria (1966). In the 1960s, research also began to concentrate on the variability of walking, the development of gait in children and the deterioration of gait in old age. Patricia Murray published a series of papers on these subjects, including a detailed review (Murray, 1967).

Mathematical Modelling

Once the motions of the body segments and the actions of the different muscles had been examined and documented, attention moved to the forces generated across the joints. Although limited calculations of this type had been made previously, the study by Paul (1965) was the first detailed analysis of hip joint forces during walking. A subsequent paper by Paul also included an analysis of the forces in the knee (Paul, 1966). Since then, there have been many mathematical studies of force generation and transmission across the hip, knee and ankle.

The 1970s and 1980s saw great improvements in methods of measurement. The development of more convenient kinematic systems, based on electronics rather than photography, meant that results could be produced in minutes rather than days. Reliable force platforms with high-frequency response became available, as well as convenient and reliable EMG systems. The availability of high-quality three-dimensional data on the kinetics and kinematics of walking, and the ease of access to powerful computers, made it possible to develop increasingly sophisticated mathematical models. Gait laboratories now routinely measure joint moments and powers for the hip, knee and ankle, and estimates can also be made of muscle, ligament and joint contact forces.

Recent decades have seen the emergence of increasingly powerful systems, higher-speed cameras, greater portability, smaller markers, a wide variety of marker sets and larger data collection volumes.

Clinical Application

In the 1960s, those working in the field of gait measurement started exploring the usefulness of gait analysis in the management of patients with walking disorders. Gait analysis has continuously advanced since that time, moving out of the research laboratory and into clinical settings. And with improvements in measurement and analytical techniques, today the major limitation is not an inability to produce high-quality data, but knowing how best to use these data for the benefit of patients. It is fair to say that in the early days, far more progress was made in scientific gait analysis, particularly as applied to normal subjects, than in the application of these techniques for the benefit of those with gait disorders. However, there has been a steady increase in the effective use of gait analysis in the clinical management of patients. Alongside this, there has also been a growing interest in the use of observational or visual gait analysis.

Terminology Used in Gait Analysis

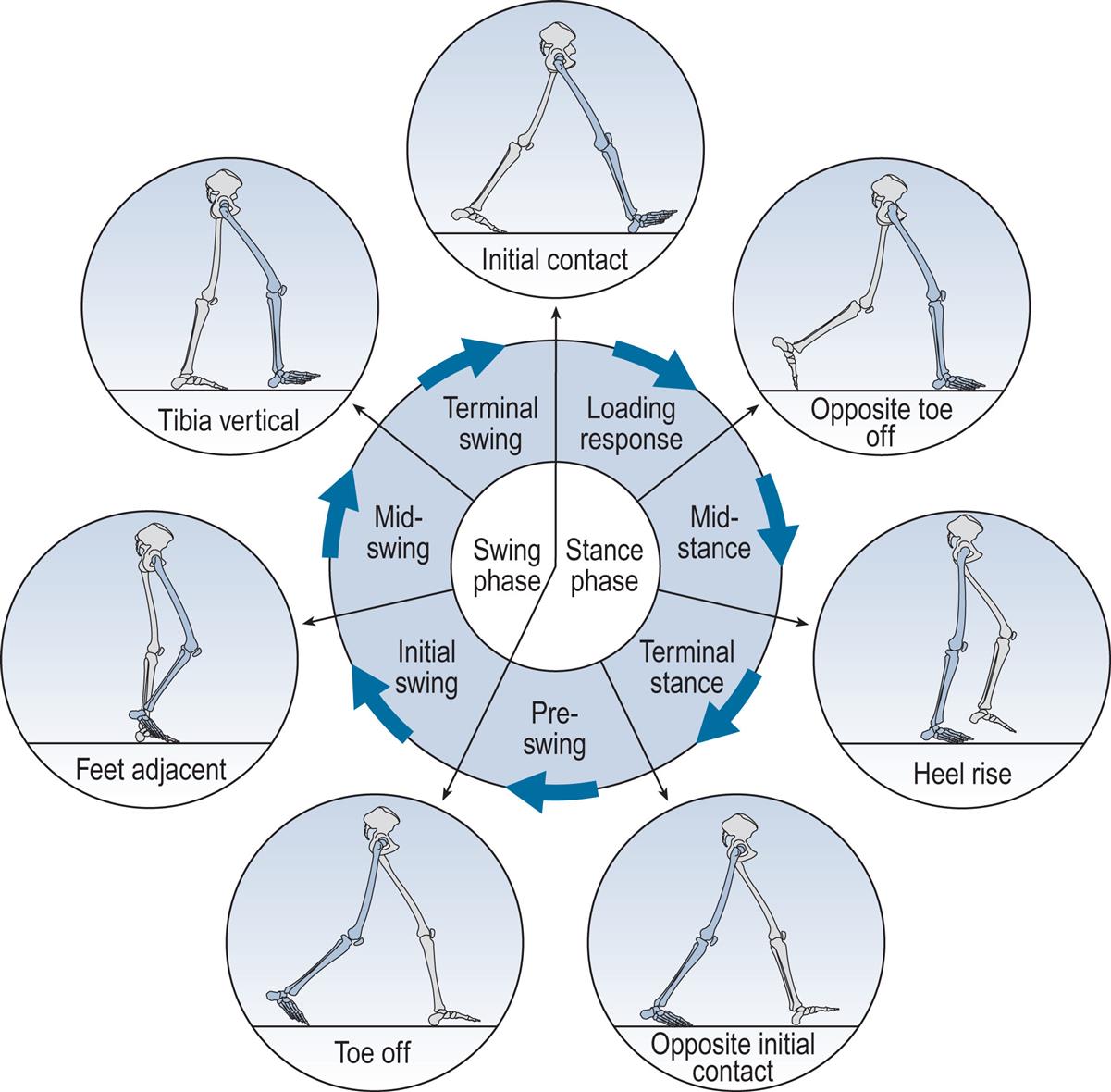

The gait cycle is defined as the time interval between two successive occurrences of one of the repetitive events of walking. Although any event could be chosen to define the gait cycle, it is generally convenient to use the instant at which one foot contacts the ground (initial contact). If it is decided to start with initial contact of the right foot, as shown in Fig. 2.1, then the cycle will continue until the right foot contacts the ground again.

The following terms are used to identify major events during the gait cycle:

These seven events subdivide the gait cycle into seven periods—four of which occur in the stance phase, when the foot is on the ground, and three in the swing phase, when the foot is moving forwards through the air (Fig. 2.1). The stance phase, which is also called the support phase or contact phase, lasts from initial contact to toe off. It is subdivided into:

The swing phase lasts from toe off to the next initial contact. It is subdivided into:

The duration of a complete gait cycle is known as the cycle time, which is divided into stance time and swing time. Unfortunately, the nomenclature used to describe the gait cycle varies considerably from one publication to another. The present text attempts to use terms which will be understood by most people working in the field; alternative terminology will be given where appropriate. However, it should be noted that the usual terminology is inadequate to describe some severe pathological gaits which were highlighted in the paper by Wall et al. (1987), ‘Two steps equals one stride equals what? The applicability of normal gait nomenclature to abnormal walking patterns’.

Gait Cycle Timing

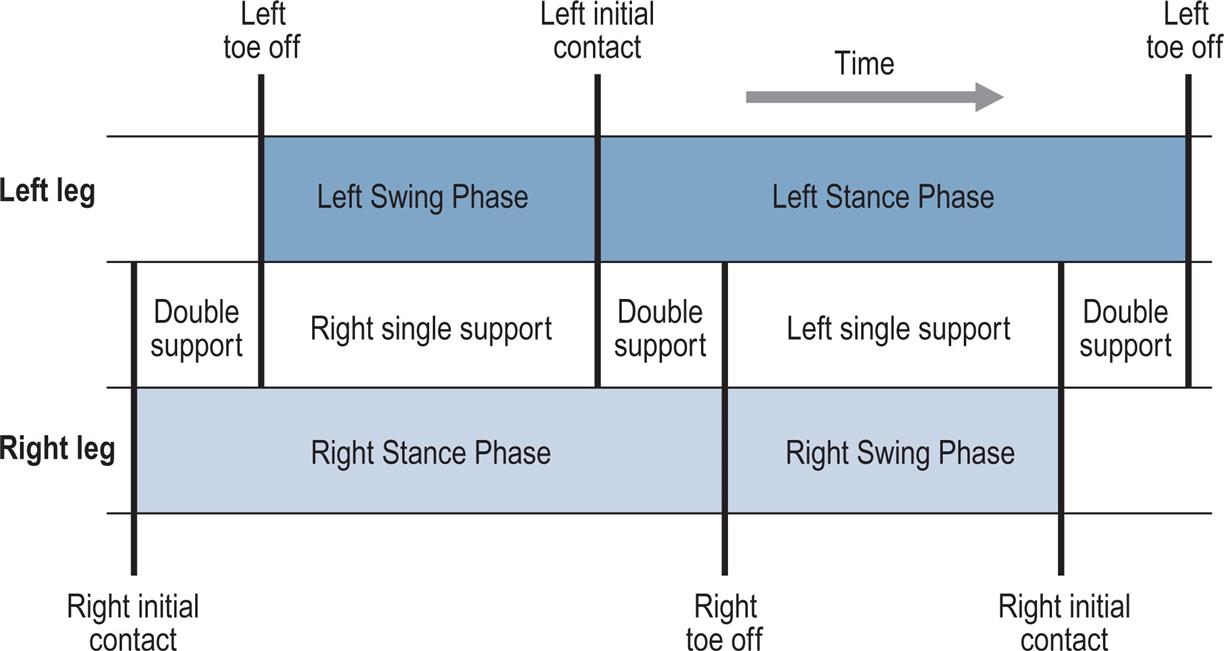

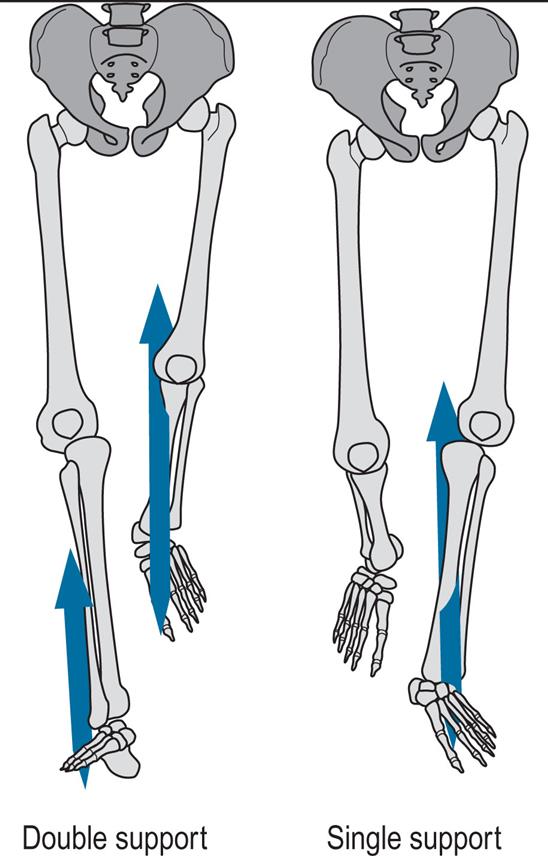

Fig. 2.2 shows the timings of initial contact and toe off for both feet during a little more than one gait cycle. Right initial contact occurs whilst the left foot is still on the ground and there is a period of double support (also known as double limb stance) between initial contact on the right and toe off on the left. During the swing phase on the left side, only the right foot is on the ground, giving a period of right single support (or single limb stance), which ends with initial contact by the left foot. There is then another period of double support, until toe off on the right side. Left single support corresponds to the right swing phase, and the cycle ends with the next initial contact on the right.

In each double support phase, one foot is forwards, having just landed on the ground, and the other one is backwards, being just about to leave the ground. When it is necessary to distinguish between the two legs in the double support phase, the leg in front is usually known as the leading leg and the leg behind as the trailing leg. The leading leg is in loading response, sometimes referred to as braking double support, initial double support or weight acceptance. The trailing leg is in pre-swing, also known as second, terminal or thrusting double support, or as weight release.

In each gait cycle, there are thus two periods of double support and two periods of single support. The stance phase usually lasts about 60% of the cycle, the swing phase about 40% and each period of double support about 10%. However, this varies with the speed of walking, with the swing phase becoming proportionately longer and the stance phase and double support phases shorter as the speed increases (Murray, 1967); see Blanc et al. (1999) for a detailed study of gait cycle timing. The final disappearance of the double support phase marks the transition from walking to running. Between successive steps in running there is a flight phase, also known as the float, double-float or nonsupport phase, when neither foot is on the ground. For more detail, this book now includes a chapter considering gait analysis of running (Chapter 8, Gait Analysis in Running and the Management of Common Injuries).

Foot Placement

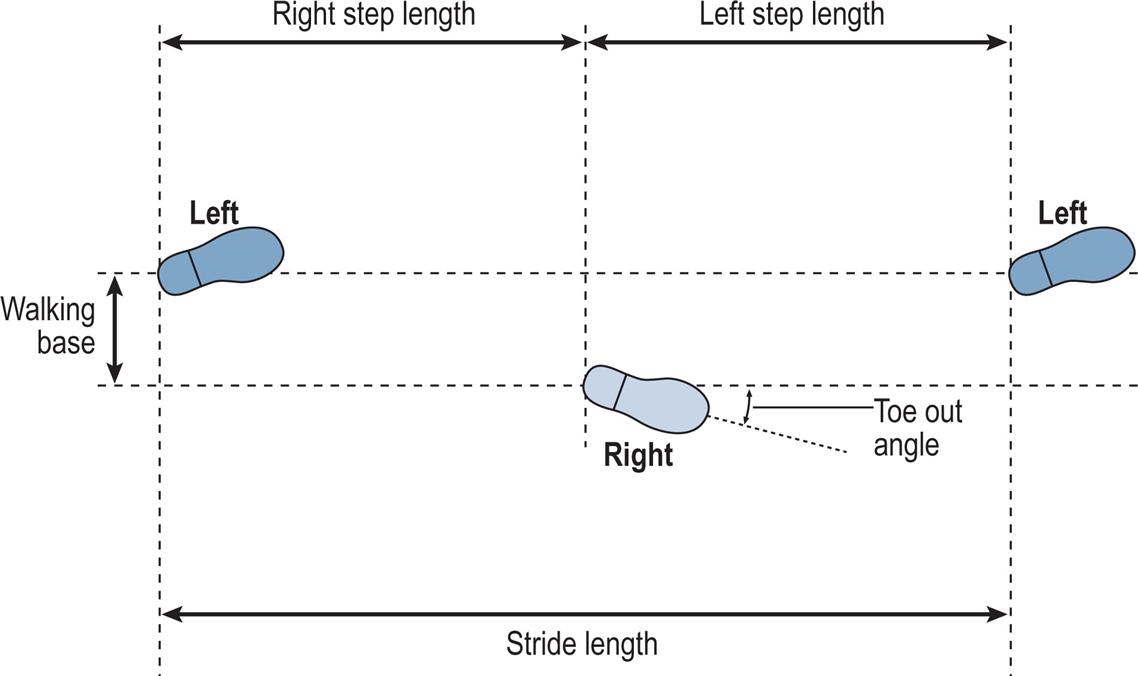

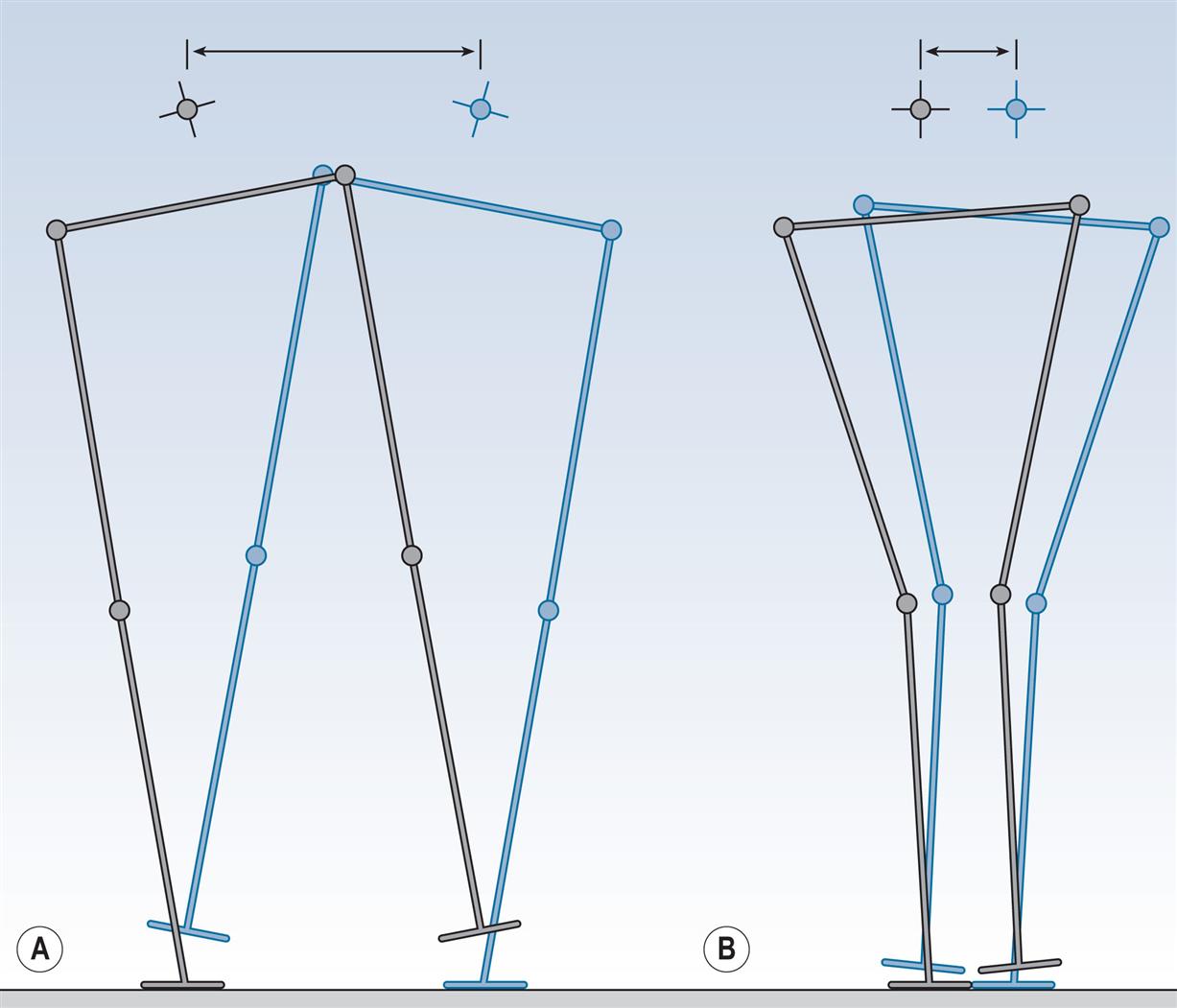

The terms used to describe the placement of the feet on the ground are shown in Fig. 2.3. The stride length is the distance between two successive placements of the same foot. It consists of two step lengths, left and right, each the distance by which the named foot moves forwards in front of the other. In pathological gait, it is common for the two step lengths to be different. If the left foot is moved forwards to take a step and the right one is brought up beside it rather than in front of it, the right step length will be zero. It is even possible for the step length on one side to be negative; for example, if the left foot never catches up with the right foot, the distance between the left and right feet will be negative. However, the stride length starting with the left heelstrike must always be the same as the stride length starting with the right heelstrike, unless the subject is walking around a curve where the inside leg will have a shorter stride length than the outside leg. This definition of a stride, consisting of one step by each foot, breaks down in some pathological gaits in which one foot makes a series of hopping movements whilst the other is in the air (Wall et al., 1987). There is no satisfactory nomenclature to deal with this situation.

The walking base (also known as the stride width or base of support) is the side-to-side distance between the line of the two feet, usually measured at the midpoint of the back of the heel but sometimes below the centre of the ankle joint. The preferred unit for stride length and step length is the metre and for the walking base, millimetres. The pattern of walking known as tandem gait involves walking with the heel of one foot placed directly in front of the toes of the other; that is, with a walking base close to zero. Although this pattern is not typically seen, even as a pathological gait it requires good balance and coordination.

The toe out (or, less commonly, toe in) is the angle in degrees between the direction of progression and a reference line on the sole of the foot. The reference line varies from one study to another; it may be defined anatomically but is commonly the midline of the foot, as judged by eye.

It is obvious that you need to walk more carefully on ice than on asphalt. Whether or not the foot slips during walking depends on two things: the coefficient of friction between the foot and the ground, and the relationship between the vertical force and the forces parallel to the walking surface (front to back and side to side). The ratio of the horizontal to the vertical force is known as the utilised coefficient of friction, and slippage will occur if this exceeds the actual coefficient of friction between the foot and the ground. In normal walking, a coefficient of friction of 0.35 to 0.40 is generally sufficient to prevent slippage; the most hazardous part of the gait cycle for slippage is initial contact. The literature on foot-to-ground friction and slippage is fairly extensive; examples include Cham and Redfern (2002) and Burnfield et al. (2005).

Cadence, Cycle Time and Speed

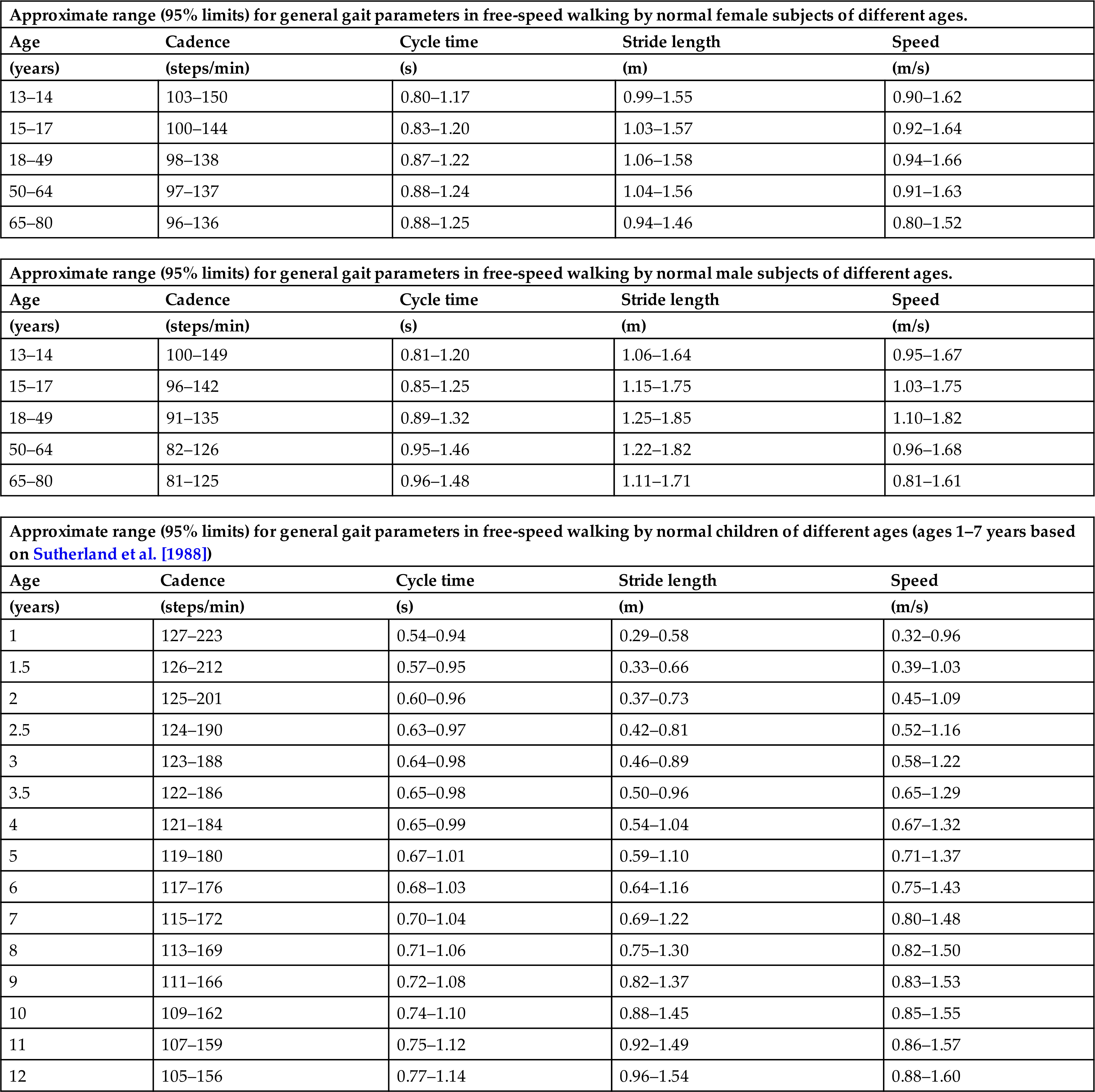

The cadence is the number of steps taken in a given time period, the usual unit being steps per minute. In most other types of scientific measurement, complete cycles are counted, but as there are two steps in a single gait cycle, the cadence is a measure of half-cycles. The normal ranges for both cadence and cycle time in both genders at different ages are shown in Table 2.1, where we consider the effect of age in more detail.

Table 2.1

| Approximate range (95% limits) for general gait parameters in free-speed walking by normal male subjects of different ages. | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | Cadence | Cycle time | Stride length | Speed |

| (years) | (steps/min) | (s) | (m) | (m/s) |

| 13–14 | 100–149 | 0.81–1.20 | 1.06–1.64 | 0.95–1.67 |

| 15–17 | 96–142 | 0.85–1.25 | 1.15–1.75 | 1.03–1.75 |

| 18–49 | 91–135 | 0.89–1.32 | 1.25–1.85 | 1.10–1.82 |

| 50–64 | 82–126 | 0.95–1.46 | 1.22–1.82 | 0.96–1.68 |

| 65–80 | 81–125 | 0.96–1.48 | 1.11–1.71 | 0.81–1.61 |

| Approximate range (95% limits) for general gait parameters in free-speed walking by normal children of different ages (ages 1–7 years based on Sutherland et al. [1988]) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | Cadence | Cycle time | Stride length | Speed |

| (years) | (steps/min) | (s) | (m) | (m/s) |

| 1 | 127–223 | 0.54–0.94 | 0.29–0.58 | 0.32–0.96 |

| 1.5 | 126–212 | 0.57–0.95 | 0.33–0.66 | 0.39–1.03 |

| 2 | 125–201 | 0.60–0.96 | 0.37–0.73 | 0.45–1.09 |

| 2.5 | 124–190 | 0.63–0.97 | 0.42–0.81 | 0.52–1.16 |

| 3 | 123–188 | 0.64–0.98 | 0.46–0.89 | 0.58–1.22 |

| 3.5 | 122–186 | 0.65–0.98 | 0.50–0.96 | 0.65–1.29 |

| 4 | 121–184 | 0.65–0.99 | 0.54–1.04 | 0.67–1.32 |

| 5 | 119–180 | 0.67–1.01 | 0.59–1.10 | 0.71–1.37 |

| 6 | 117–176 | 0.68–1.03 | 0.64–1.16 | 0.75–1.43 |

| 7 | 115–172 | 0.70–1.04 | 0.69–1.22 | 0.80–1.48 |

| 8 | 113–169 | 0.71–1.06 | 0.75–1.30 | 0.82–1.50 |

| 9 | 111–166 | 0.72–1.08 | 0.82–1.37 | 0.83–1.53 |

| 10 | 109–162 | 0.74–1.10 | 0.88–1.45 | 0.85–1.55 |

| 11 | 107–159 | 0.75–1.12 | 0.92–1.49 | 0.86–1.57 |

| 12 | 105–156 | 0.77–1.14 | 0.96–1.54 | 0.88–1.60 |

The speed of walking is the distance covered by the whole body in a given time, and should be measured in metres per second. Many authors use the term velocity in place of speed, but this is an incorrect usage of the term, unless the direction of walking is also stated, since velocity is a vector. The instantaneous speed varies from one instant to another during the walking cycle, but the average speed is the product of the cadence and the stride length, providing appropriate units are used. The cadence, in steps per minute, corresponds to half-strides per 60 seconds or full strides per 120 seconds. The speed can thus be calculated from cadence and stride length using the formula:

If cycle time is used in place of cadence, the calculation becomes much more straightforward:

The walking speed thus depends on the two step lengths, which in turn depend to a large extent on the duration of the swing phase on each side. The step length is the amount by which the foot can be moved forwards during the swing phase so that a short swing phase on one side will generally reduce the step length on that side. In pathological gait, the step length is often shortened, but it behaves in a way which is counterintuitive. When pathology affects one foot more than the other, an individual will usually try to spend a shorter time on the ‘bad’ foot and a correspondingly longer time on the ‘good’ one. Shortening the stance phase on the bad foot means bringing the good foot to the ground sooner, thereby shortening both the duration of the swing phase and the step length on that side. Thus a short step length on one side generally means problems with single support on the other side.

When making comparisons among individuals, particularly children, it is useful to allow for differences in size. This is done by dividing a measurement by some aspect of body size, such as height (stature) or leg length, a procedure generally known as normalisation. It is thus fairly common to see walking speed expressed in statures per second or to see measures such as step factor, which is step length divided by leg length (Sutherland, 1997).

Since walking speed depends on both cadence and stride length, it follows that speed may be changed by altering only one of these variables—for instance, by increasing the cadence whilst keeping the stride length constant. In practice, however, people normally change their walking speed by adjusting both cadence and stride length. Sekiya and Nagasaki (1998) defined the walk ratio as step length (m) divided by step rate (steps/min) and found that it was fairly constant in both males and females over a range of walking speeds from very slow to very fast. Macellari et al. (1999) conducted a detailed study of the relationships among gender, body size, walking speed, gait timing and foot placement.

Overview of the Gait Cycle

The purpose of this section is to provide an overview of the gait cycle so that the detailed description which follows is easier to comprehend. The cycle is illustrated by Figs. 2.4 and 2.10–2.18, all of which are taken from a single walk by a 22-year-old healthy female, weight 540 N (55 kg, 121 lb), walking barefoot with a cycle time of 0.88 s (cadence 136 steps/min), a stride length of 1.50 m and a speed of 1.70 m/s. The individual measurements from this subject do not always correspond to ‘average’ values due to variability among individuals, although they are all close to the normal range. The measurements were made in the plane of progression, which is a vertical plane aligned to the direction of the walk; in normal walking it closely corresponds to the sagittal plane of the body. The data were obtained using a Vicon motion system and a Bertec force platform. It should be noted that different laboratories use different methods of measurement, so other publications may quote different values for some of the measured variables. The reader should thus concentrate on the changes in the variables during the gait cycle rather than on their absolute values.

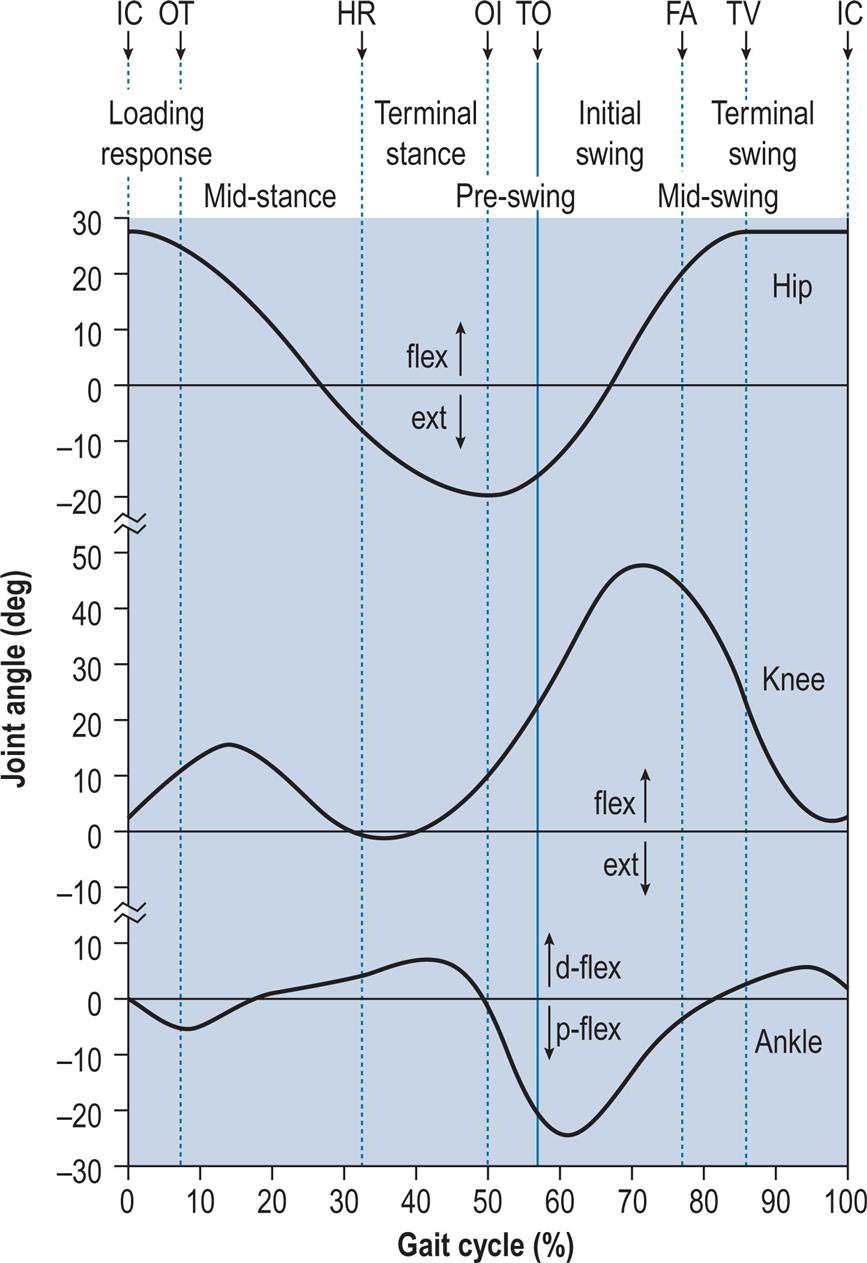

When examining diagrams of the joint angles through the gait cycle, it is essential to understand how the angles are defined. Generally speaking, the knee angle is defined as the angle between the femur and the tibia, and there is usually no ambiguity. The ankle angle is usually defined as the angle between the tibia and an arbitrary line in the foot. Although this angle is normally around 90 degrees, it is conventional to define it as 0 degrees, with dorsiflexion and plantarflexion being movements in the positive and negative directions. In this book, dorsiflexion is a positive angle, but in some other publications it is negative. The hip angle may be measured in two different ways: the angle between the vertical and the femur, and the angle between the pelvis and the femur. The latter is the ‘true’ hip angle and is usually defined so that 0 degrees is close to the hip angle in the standing position. Forward flexion of the trunk appears as hip flexion when the hip angle is defined with reference to the pelvis, but not when it is defined with reference to the vertical.

The descriptions which follow assume that symmetry is present between the two sides of the body. This is approximately true for normal individuals, although detailed examination shows that everyone has some degree of asymmetry (Sadeghi, 2003). Such subtle asymmetries are negligible, especially when contrasted to the majority of pathological gaits.

In some gait studies the subject is barefoot, and in others the subject is wearing shoes. Oeffinger et al. (1999) found small differences in some of the gait parameters between these two conditions in children but did not consider them to be clinically important. It is usually at the discretion of the investigator whether or not shoes are worn, although in some cases this may be dictated by the presence of an intervention (e.g., when an ankle foot orthosis or an orthotic insole is used).

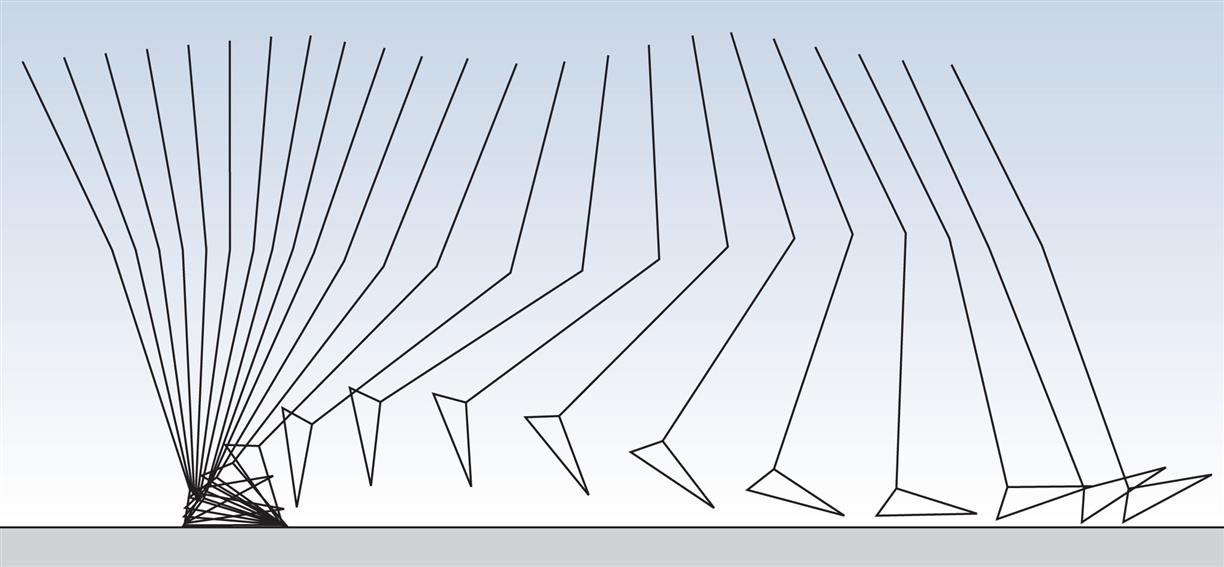

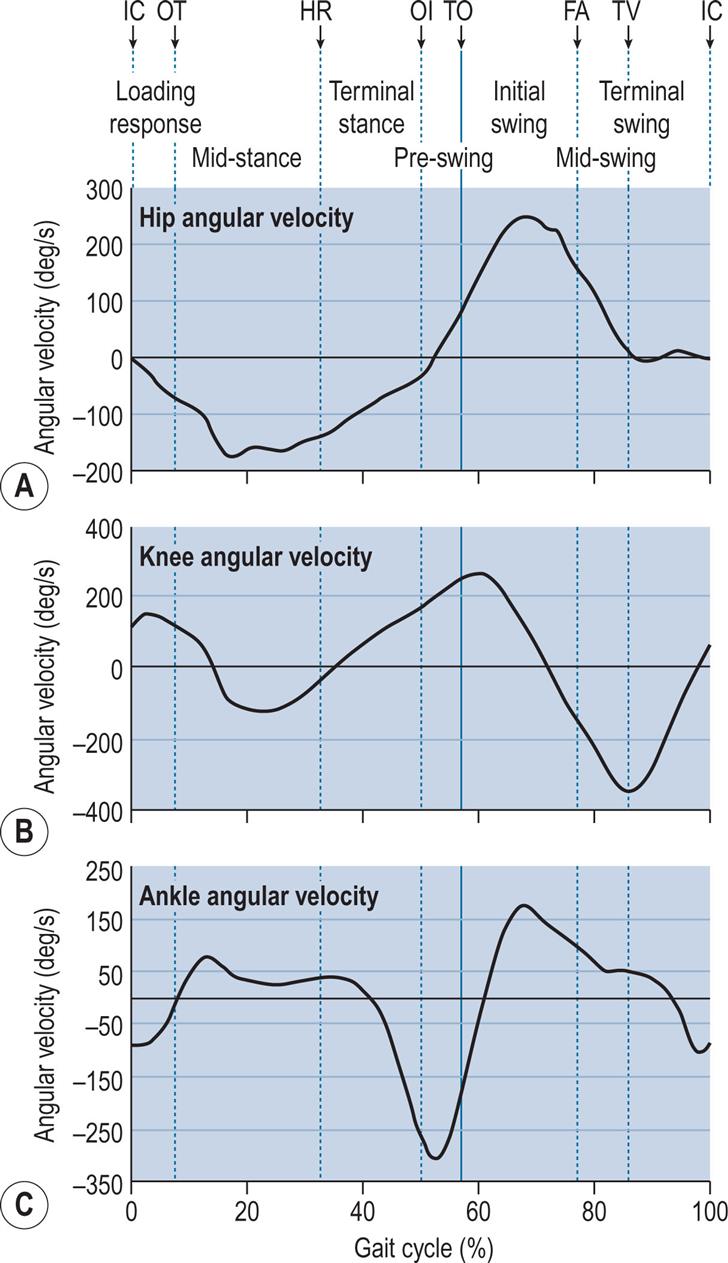

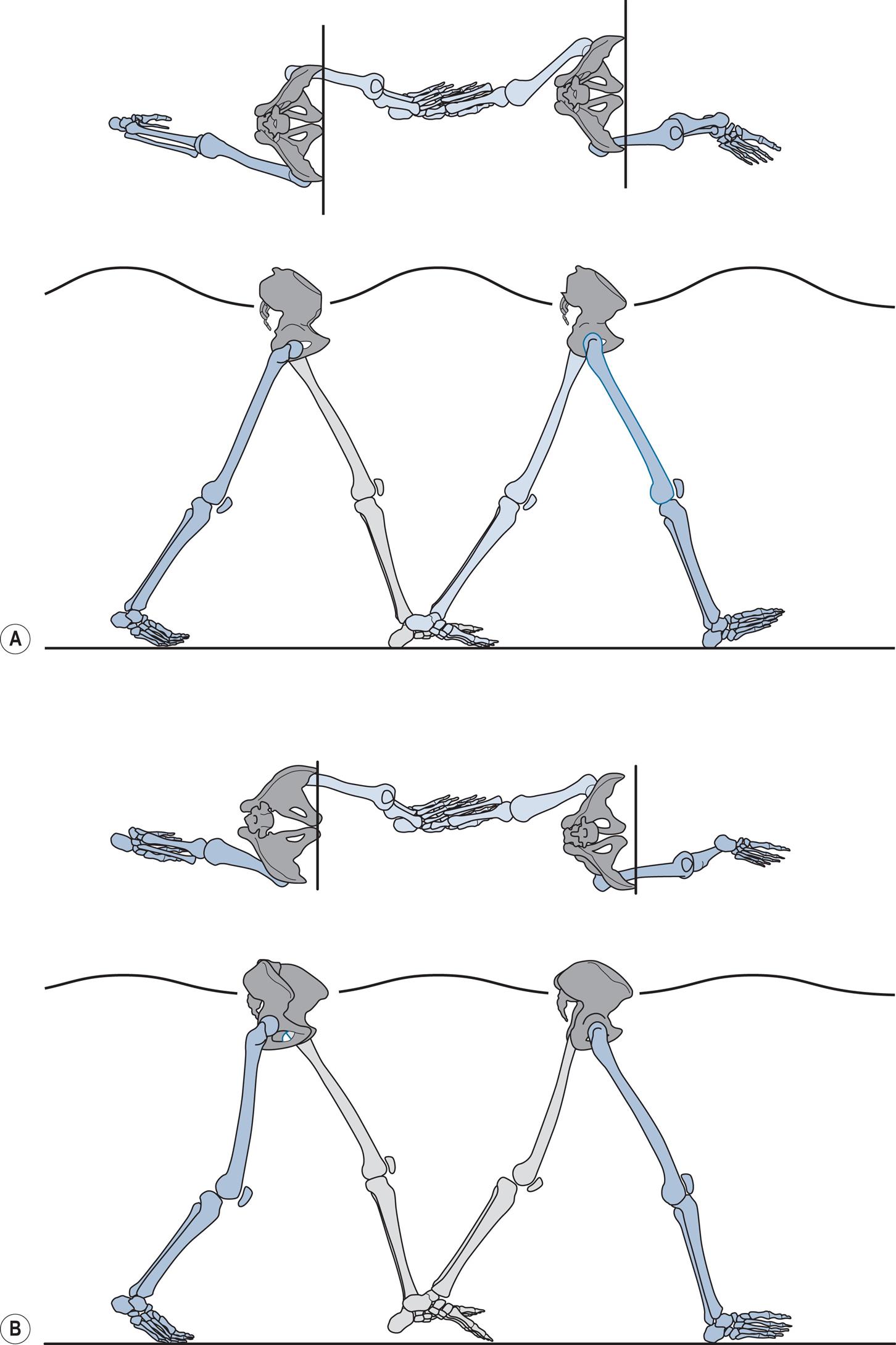

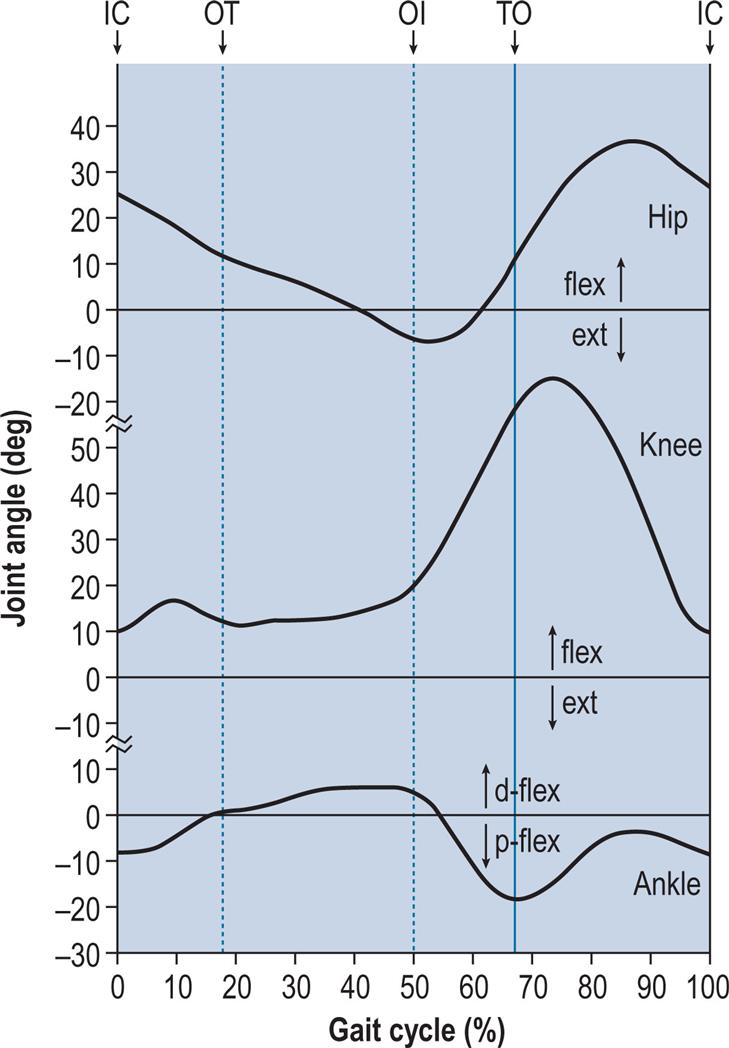

During gait, important movements occur in all three planes: sagittal, coronal and transverse. However, this chapter will concentrate on the sagittal plane, in which the largest movements occur. Fig. 2.4 shows the successive positions of the right leg at 40-ms intervals, measured over a single gait cycle. Fig. 2.5 shows the corresponding sagittal plane angles at the hip, knee and ankle joints and Fig. 2.6 shows the sagittal plane angular velocity of the hip, knee and ankle joints.

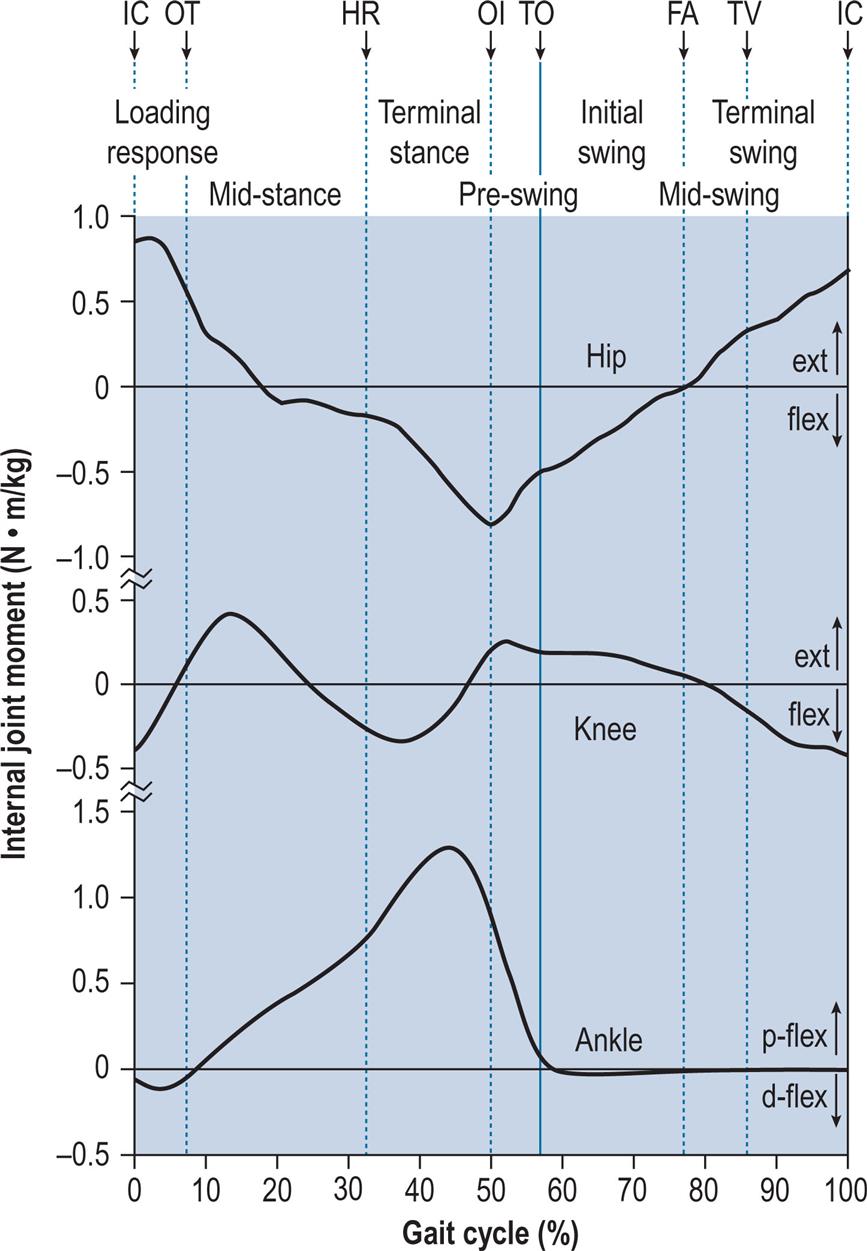

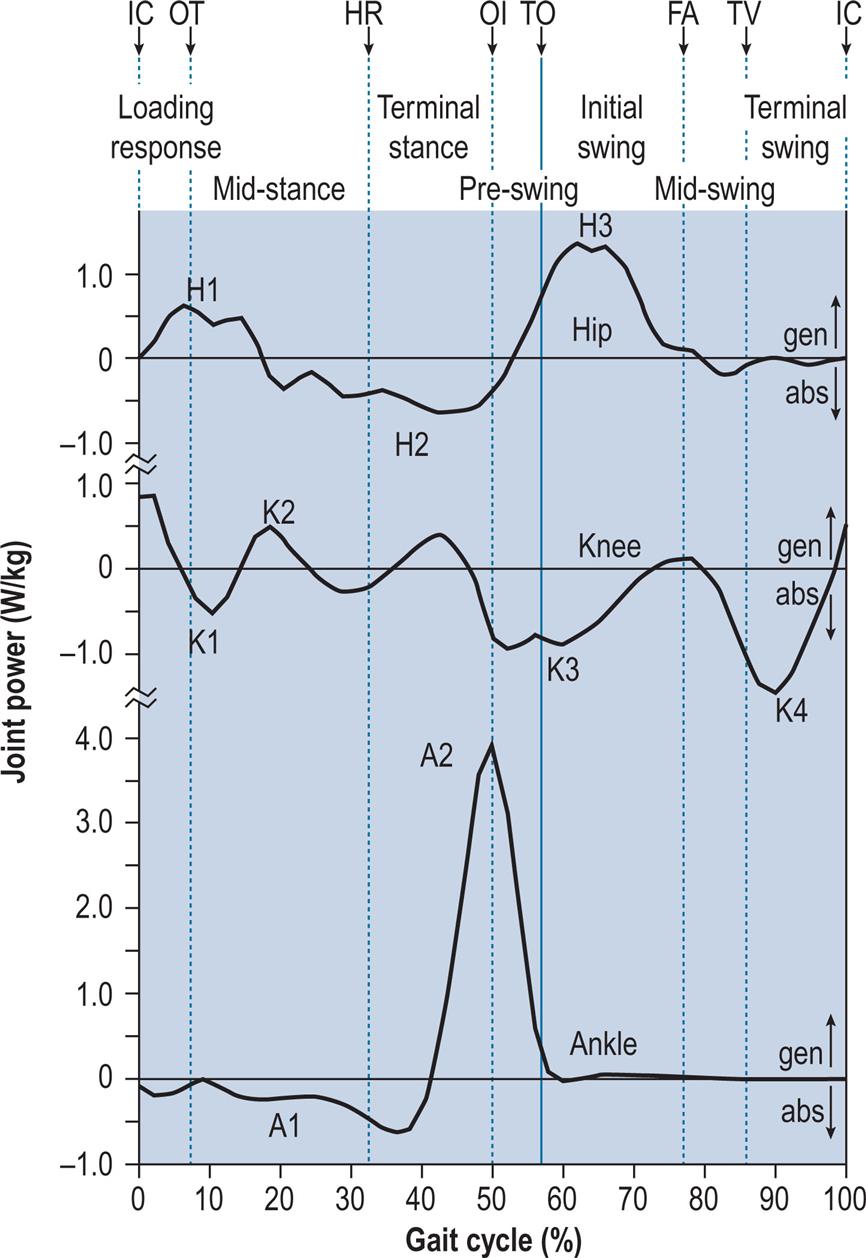

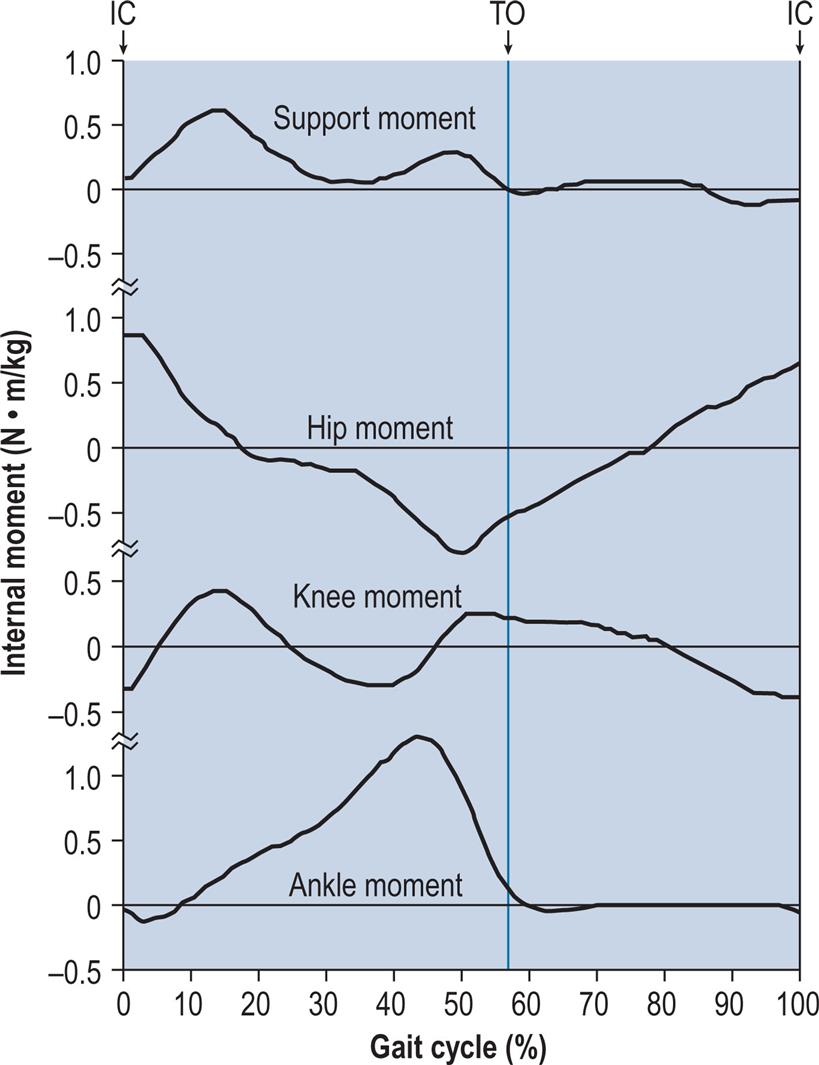

Fig. 2.7 shows the internal joint moments (in newton-metres per kilogram of body mass) and Fig. 2.8 the joint powers (in watts per kilogram of body mass). Different authors have used different units for the measurement of moments and powers; those used here are scaled for body mass, but not for the length of the limb segments. In Fig. 2.8, the annotations H1–H3, K1–K4 and A1–A2 refer to the peaks of power absorption and generation described by Winter (1991).

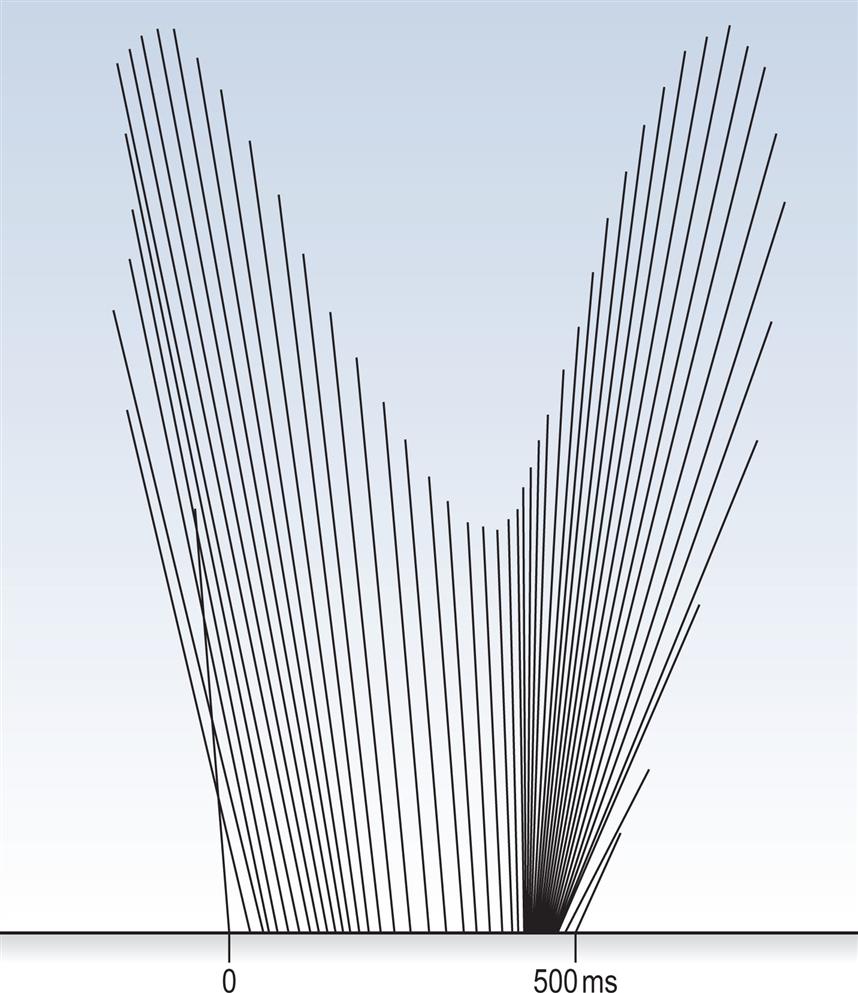

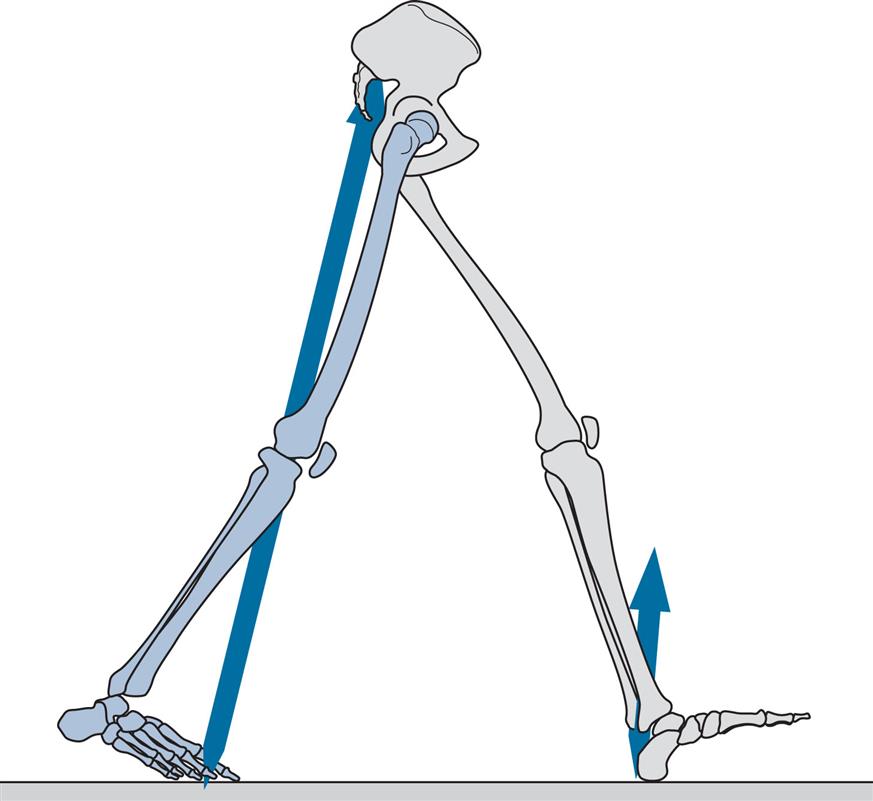

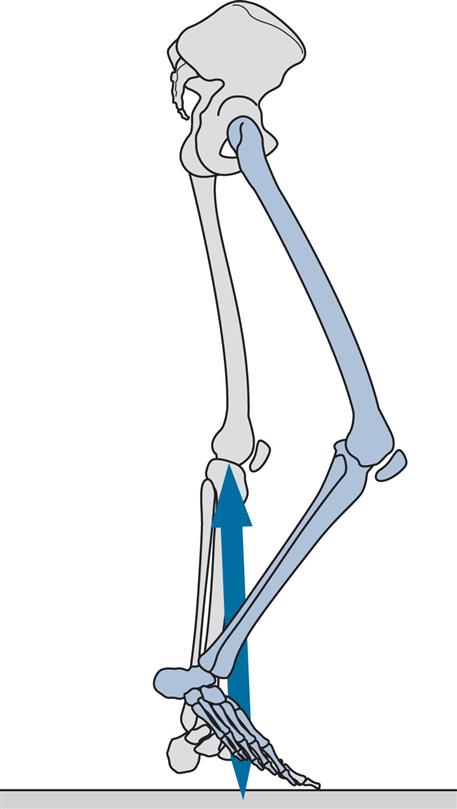

Fig. 2.9 shows a ‘butterfly diagram’, described by Pedotti (1977). This is a plot of the ground reaction vectors and is made up of successive representations, in this case at 10-ms intervals, of the magnitude, direction and point of application of the ground reaction force vector. The vectors move across the diagram from left to right and create a shape that resembles the wings of a butterfly.

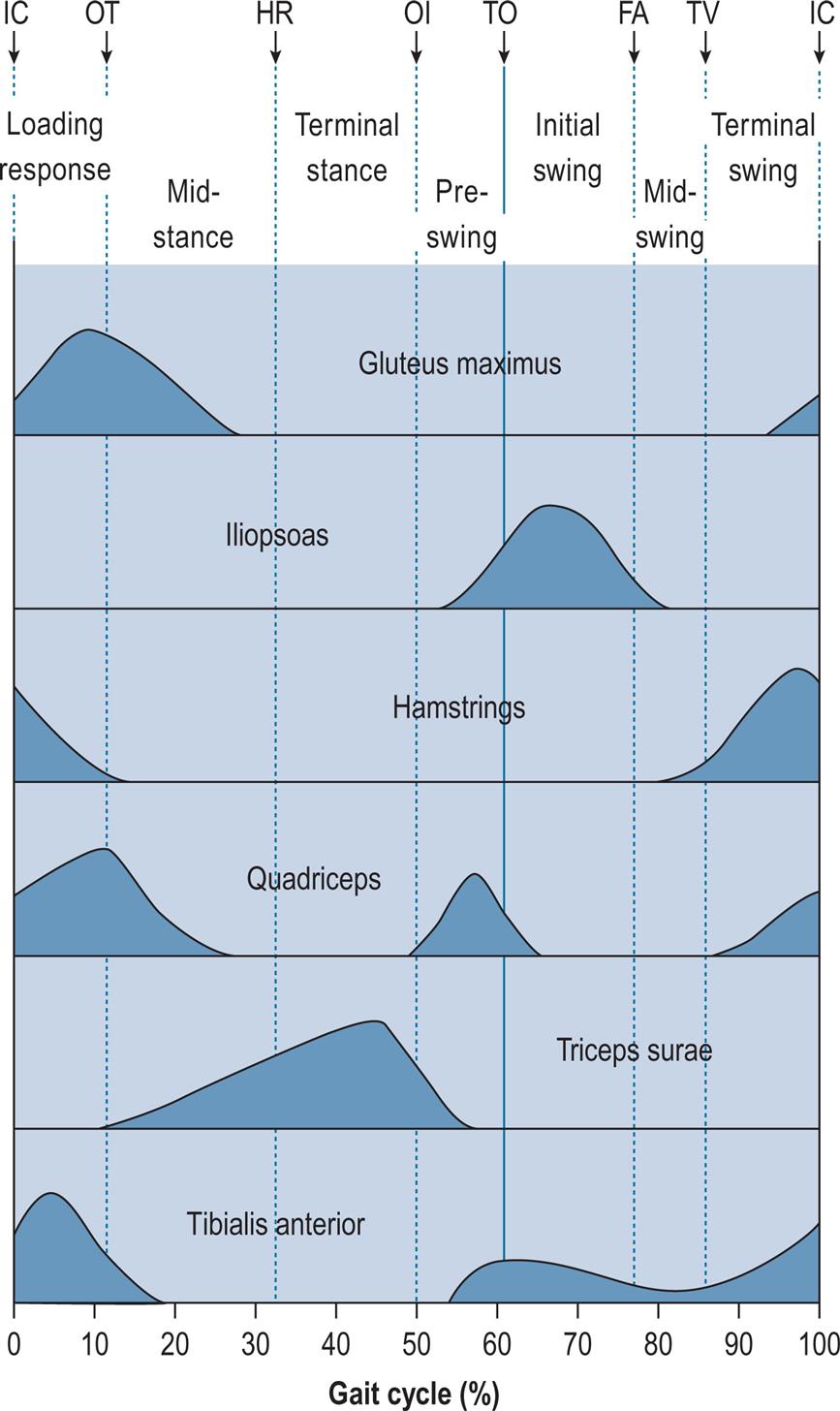

Fig. 2.10 gives the typical activity of a number of key muscles or muscle groups during the gait cycle. This is based largely on data from Perry (1992), Inman et al. (1981) and Rose and Gamble (1994). Similar, though not identical, data for these and other muscles were given by Sutherland (1984) and Winter (1991). Although Fig. 2.10 shows a typical pattern, it is not the only possible one. One of the interesting things about gait is the way in which the same movement may be achieved in a number of different ways, and this particularly applies to the use of muscles; as a result, two people may walk with the same ‘normal’ gait pattern but using different combinations of muscles. The pattern of muscle usage not only varies from one subject to another but is also affected by fatigue, and within subject variations are seen with walking speed. The muscular system is said to possess redundancy, which means that if a particular muscle cannot be used, its functions may be taken over by another muscle or group of muscles. A good review of muscle activity in gait was provided by Shiavi (1985).

Upper Body

The upper body moves forwards throughout the gait cycle. Its speed varies a little, being fastest during the double support phases and slowest in the middle of the stance and swing phases. The trunk twists about a vertical axis, with the shoulder girdle rotating in the opposite direction to the pelvis. The arms swing out of phase with the legs so that the left leg and the left side of the pelvis move forwards at the same time as the right arm and the right side of the shoulder girdle. Lamoth et al. (2002) made a detailed study of the relative motion between the pelvis and the trunk at different walking speeds. Murray (1967) found average total excursions of 7 degrees for the shoulder girdle and 12 degrees for the pelvis in adult males walking at free speed. The fluidity and efficiency of walking depend to some extent on the motions of the trunk and arms, but these movements are commonly ignored in clinical gait analysis and have been relatively neglected in gait research. The whole trunk rises and falls twice during the cycle, through a total range of about 46 mm (Perry, 1992), being lowest during double support and highest in the middle of the stance and swing phases. An approximation to this vertical motion can be seen in the position of the hip joint in Fig. 2.4. The trunk also moves from side to side, once in each cycle, with the trunk being over each leg during its stance phase, as might be expected from the need for support. The total range of side-to-side movement is also about 46 mm (Perry, 1992). The pelvis twists about a vertical axis and tips slightly, both backwards and forwards (with an associated change in lumbar lordosis) and from side to side. The spinal muscles are selectively activated so that the head moves less than the pelvis, which is important for providing a stable platform for vision (Prince et al., 1994).

Hip

The hip flexes and extends once during the cycle (Fig. 2.5). The limit of flexion is reached around the middle of the swing phase, and the hip is then kept flexed until initial contact. The peak extension is reached before the end of the stance phase, after which the hip begins to flex again.

Knee

The knee shows two flexion and two extension peaks during each gait cycle. It is almost fully extended before initial contact, flexes during the loading response and the early part of mid-stance (stance phase knee flexion), extends again during the latter part of mid-stance, then starts flexing again, reaching a peak during initial swing (swing phase knee flexion). It extends again prior to the next initial contact.

Ankle and Foot

The ankle is usually within a few degrees of the neutral position for dorsiflexion/plantarflexion at the time of initial contact. After initial contact, the ankle plantarflexes, bringing the forefoot down onto the ground. During mid-stance, the tibia moves forwards over the foot, and the ankle joint becomes dorsiflexed. Before opposite initial contact, the ankle angle again changes, with a major plantarflexion taking place until just after toe off. During the swing phase, the ankle moves back into dorsiflexion until the forefoot has cleared the ground (around feet adjacent), after which something close to the neutral position is maintained until the next initial contact. In the frontal plane, the foot is slightly inverted (supinated, adducted or varus) at initial contact. The foot pronates as it contacts the ground, then moves back into supination as the ankle angle changes from plantarflexion to dorsiflexion; this supinated attitude is maintained as the heel rises and the ankle plantarflexes prior to toe off. Some degree of supination is retained throughout the swing phase.

The Gait Cycle in Detail

Each of the following sections begins with general remarks about the events surrounding a particular phase in the gait cycle and then describes what is happening in the upper body, hips, knees, ankles and feet, with particular reference to the activity of the muscles. These sections are very detailed and may be too much to comprehend in one pass. It is suggested that the reader should skip the sections on moments and powers on the first reading, but should go back to them later to gain a deeper understanding of the mechanical processes underlying the gait cycle. The figures shown in this section represent the normal positions of the lower limbs and pelvis at different events during gait and the ground reaction force vector expected. More detailed descriptions of the events of normal gait are given by Murray (1967), Perry (1992), Inman et al. (1981) and Rose and Gamble (1994).

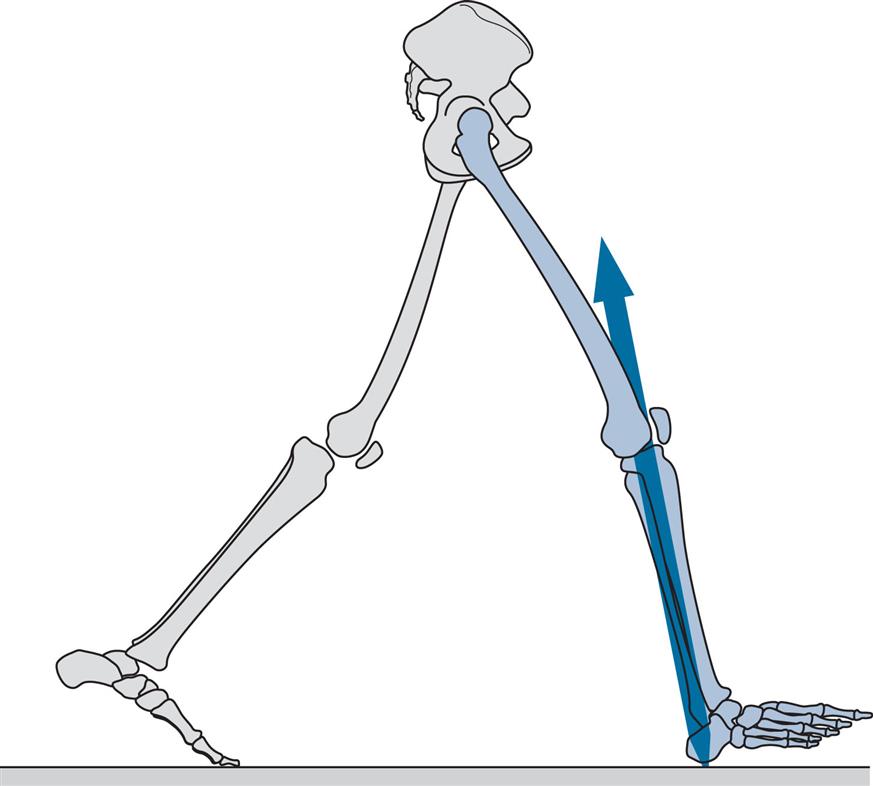

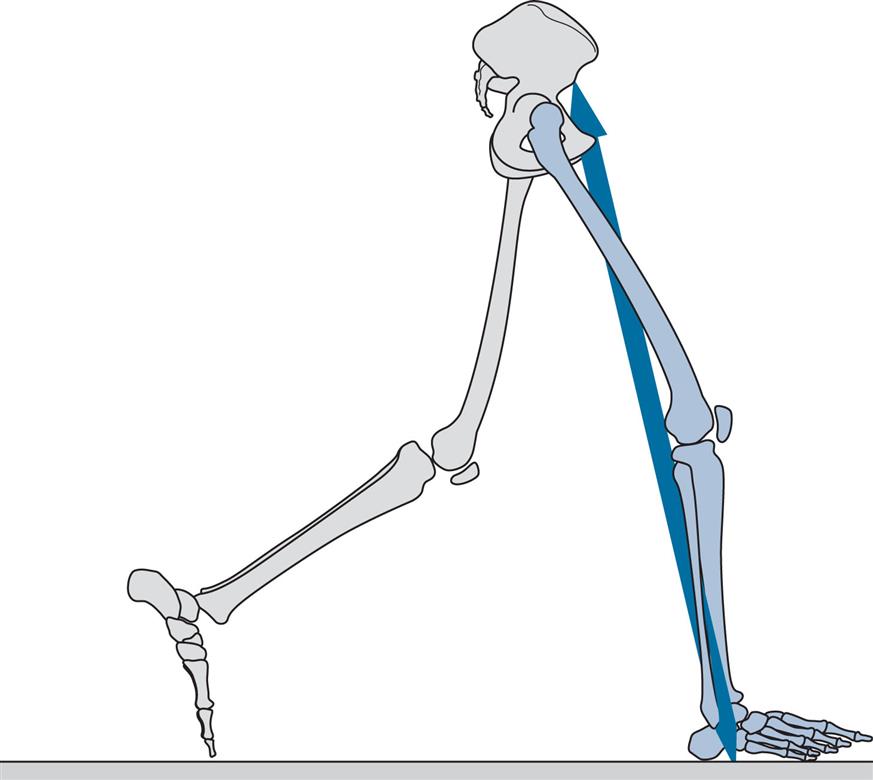

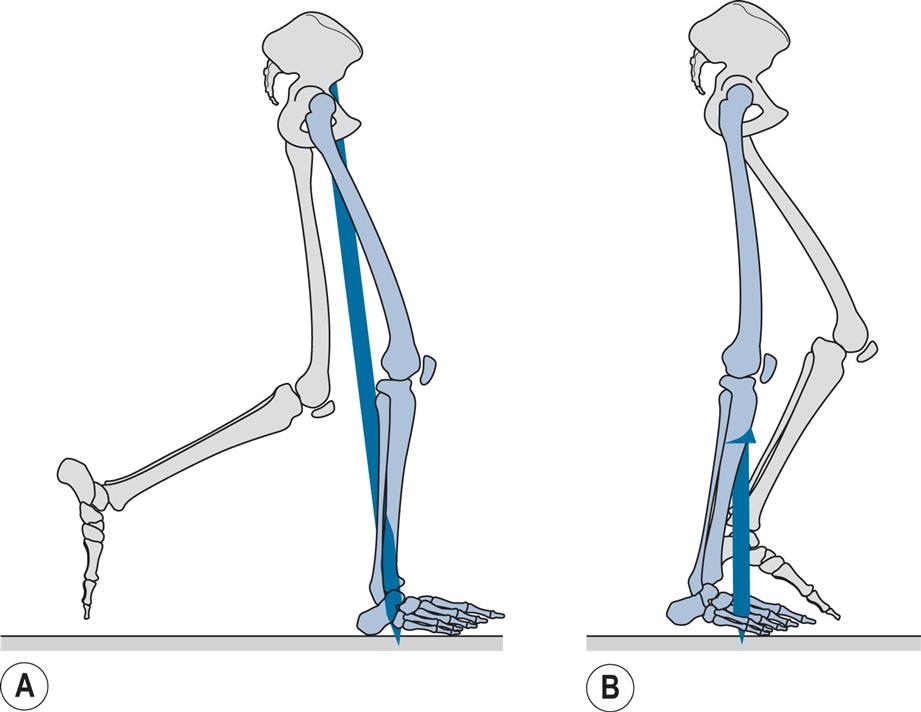

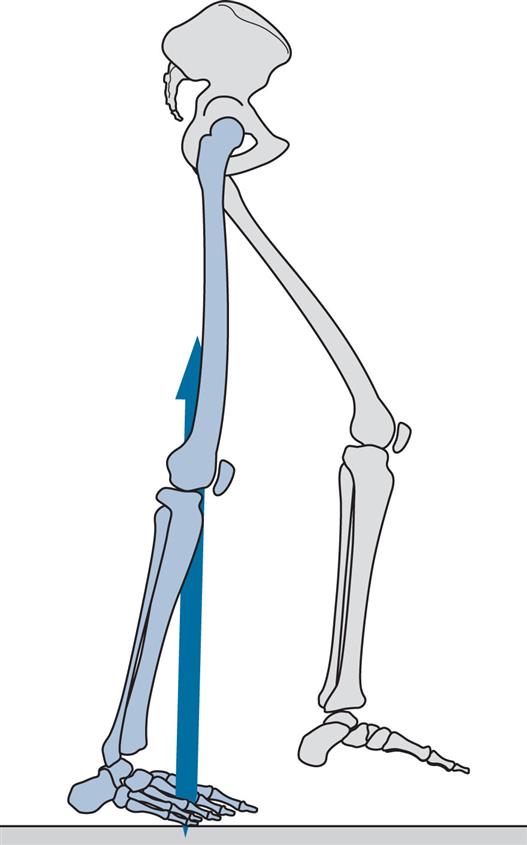

Figs 2.11–2.19 show the positions of the two legs and the ground reaction force vector beneath the right foot (where present) at the seven major events of the gait cycle, and at two additional points: near the beginning of the loading response (Fig. 2.12) and halfway through mid-stance (Fig. 2.14). The description is based on a gait cycle from right initial contact to the next right initial contact.

Throughout the text, references will be made to the position of the ground reaction force vector relative to the axis of a joint and to the resultant joint moments. This approach, known as vector projection, is an approximation at best, since it neglects the mass of the leg below the joint in question (especially important at the hip) and also ignores the acceleration and deceleration of the limb segments (which primarily lead to errors in the swing phase). However, the authors have used this approach since it makes it much easier to understand joint moments. The graphs for joint moments (Fig. 2.7) and joint powers (Fig. 2.8) were calculated correctly using a method known as inverse dynamics, which is based on the kinematics, the ground reaction force and the subject’s anthropometry.

Initial Contact (Fig. 2.11)

General

Initial contact is the beginning of the loading response and the first period of the stance phase. Initial contact is frequently called heelstrike, since in normal individuals there is often a distinct impact between the heel and the ground, known as the heelstrike transient. Other names for this event are heel contact, footstrike and foot contact. The direction of the ground reaction force changes from generally upwards during the heelstrike transient (Fig. 2.11) to upwards and backwards in the loading response immediately afterwards (Fig. 2.12). This change in direction can also be seen in the butterfly diagram (Fig. 2.9), where the force vector changes direction immediately after initial contact.

Upper Body

The trunk is about half a stride length behind the leading (right) foot at the time of initial contact. In the side-to-side direction, the trunk is crossing the midline in its range of travel, moving towards the right as the foot on that side makes contact. The trunk is twisted, with the left shoulder and the right side of the pelvis each being at their furthest forwards and the left arm at its most advanced. The amount of arm swing varies greatly from one person to another, and it also increases with the speed of walking. At the time of initial contact, Murray (1967) found the mean elbow flexion to be 8 degrees and the shoulder flexion 45 degrees.

Hip

The attitude of the legs at the time of initial contact is shown in Fig. 2.11. The maximum flexion of the hip (generally around 30 degrees) is reached around the middle of the swing phase, after which it changes little until initial contact. The hamstrings are active during the latter part of the swing phase (since they act to prevent knee hyperextension), and the gluteus maximus begins to contract around the time of initial contact; together, these muscles start the extension of the hip, which will be complete around the time of opposite initial contact (Fig. 2.5).

Knee

The knee extends rapidly at the end of the swing phase, becoming nearly fully extended before initial contact, and then starts to flex again (Figs. 2.5 and 2.11). This extension is generally thought to be passive, although Perry (1992) states that it involves quadriceps contraction. Except in very slow walking, the hamstrings contract eccentrically at the end of the swing phase, to act as a braking mechanism to prevent knee hyperextension. This contraction continues into the beginning of the stance phase.

Ankle and Foot

The ankle is generally close to its neutral position in plantarflexion/dorsiflexion at the time of initial contact. Since the tibia is sloping backwards, the foot slopes upwards and only the heel contacts the ground (Fig. 2.11). The foot is usually slightly supinated (inverted, adducted or varus) at this time, and relatedly, most people show a wear pattern on the lateral side of the heel of the shoe. The tibialis anterior is active throughout the swing phase and in early stance, having maintained dorsiflexion during the swing and in preparation for the controlled movement into plantarflexion which occurs following initial contact.

Moments and Powers

At the time of initial contact, there is an internal extensor moment at the hip (Fig. 2.7), produced by contraction of the hip extensors (the gluteus maximus and the hamstrings, Fig. 2.10). As the hip joint moves in the direction of extension, these muscles contract concentrically and generate power (H1 in Fig. 2.8). The knee shows an internal flexor moment, due to contraction of the hamstrings (Fig. 2.10) as they prevent hyperextension at the end of the swing phase. As the knee starts to flex, concentric contraction of the hamstrings, as well as the release of energy stored in the ligaments of the extended knee, results in short-lived power generation (the unnamed peak in Fig. 2.8). Little moment or power exchange occurs at the ankle until just after initial contact. The heelstrike involves an absorption of energy by the elastic tissues of the heel and by compliant materials in footwear, very little of which could be recovered later in the stance phase. The amount of energy lost to the environment as sound and heat in this way is probably fairly small.

Loading Response (Fig. 2.12)

General

The loading response is the double support period between initial contact and opposite toe off. During this period, the foot is lowered to the ground by plantarflexion of the ankle. The ground reaction force increases rapidly in magnitude, its direction being upwards and backwards. In the subject used for illustration, loading response occupied the period from 0% to 7% of the cycle; this is unusually short, with loading response typically occupying the first 10% to 12% of the cycle. Fig. 2.12 represents 2% of the cycle.

Upper Body

During loading response, the trunk is at its lowest vertical position, about 20 mm below its average level for the whole cycle; its instantaneous forward speed is at its greatest, around 10% higher than the average speed for the whole cycle. It continues to move laterally towards the right foot. The arms, having reached their maximum forward (left) and backward (right) positions, begin to return.

Hip

During loading response, the hip begins to extend (Fig. 2.5) through concentric contraction of the hip extensors, the gluteus maximus and the hamstrings (Fig. 2.10).

Knee

From its nearly fully extended position at initial contact, the knee flexes during loading response (Fig. 2.5), initiating the stance phase flexion. This is accompanied by eccentric contraction of the quadriceps (Fig. 2.10) to control the speed and magnitude of flexion.

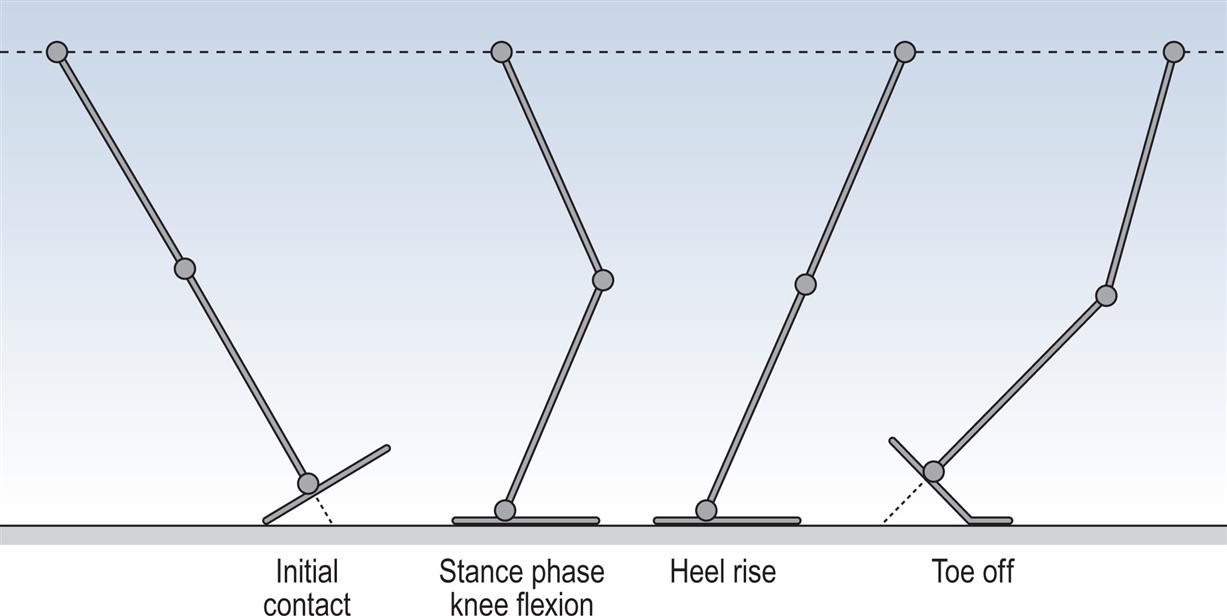

Ankle and Foot

The loading response period of the gait cycle, also called the initial rocker, heel rocker or heel pivot, involves plantarflexion at the ankle (Fig. 2.5). The plantarflexion is controlled by eccentric contraction of the tibialis anterior muscle. The movement into plantarflexion is accompanied by pronation of the foot and internal rotation of the tibia, as there is an automatic coupling between pronation/supination of the foot and internal/external rotation of the tibia (Inman et al., 1981; Rose and Gamble, 1994). The direction of the force vector changes from that shown in Fig. 2.11 to that shown in Fig. 2.12, within a 10- to 20-ms period.

Moments and Powers

As described earlier in ‘Initial Contact’, the hip shows an internal extensor moment with power generation during the loading response, and the knee shows an internal flexor moment with power generation. At the ankle, the posterior placement of the force vector (Fig. 2.12) produces an external plantarflexor moment. In the normal individual, this is resisted by an internal dorsiflexor moment (Fig. 2.7) produced by the tibialis anterior (Fig. 2.10), which contracts eccentrically, absorbs power (Fig. 2.8) and permits the foot to be lowered gently to the ground. Should the tibialis anterior fail to generate sufficient moment, the foot plantarflexes too rapidly, producing an audible ‘foot slap’.

Opposite Toe Off (Fig. 2.13)

General

Opposite toe off, also known as opposite foot off, is the end of the double support period known as loading response and the beginning of mid-stance, the first period of single support. The forefoot, which was being lowered by plantarflexion of the ankle, contacts the ground at foot flat, also known as forefoot contact, which generally occurs around the time of opposite toe off. On the opposite (left) side, it marks the end of the stance phase and the beginning of the swing phase. In the subject used for illustration, opposite toe off (Fig. 2.13) occurred at 7% and foot flat at 8% of the cycle.

Upper Body

At opposite toe off, the left shoulder and arm, having reached their most forward positions, are now moving posteriorly. Similarly, the pelvis on the right side now starts to twist back towards the neutral position. The trunk, having reached its lowest position during loading response, now begins to gain height but loses forward speed as a result of the backward and upward direction of the ground reaction force acting on the centre of gravity of the body. This represents a conversion of kinetic energy to potential energy, similar to a child’s swing at its lowest point before it begins to climb up again.

Hip

The hip flexion angle is around 25 degrees at time of opposite toe off (Fig. 2.5). The hip continues to extend through the concentric contraction of the gluteus maximus and hamstrings.

Knee

At opposite toe off, the knee is continuing to flex, reaching peak stance phase knee flexion early in mid-stance, after which it begins to extend again (Fig. 2.5). The magnitude of the stance phase flexion is very sensitive to walking speed and can disappear during slow walking. Quadriceps contraction (eccentric, then concentric) permits the knee to act like a spring, preventing the vertical force from building up too rapidly (Perry, 1974).

Ankle and Foot

As soon as the foot is flat on the ground, around opposite toe off, the direction of ankle motion changes from plantarflexion to dorsiflexion, as the tibia moves over the now stationary foot (Fig. 2.5). Both foot pronation and internal tibial rotation reach a peak around opposite toe off and begin to reverse. These two motions are ‘coupled’; that is, they always occur together, due in part to the geometry of the ankle and subtalar joints (Inman et al., 1981; Rose and Gamble, 1994). The tibialis anterior ceases to contract and is replaced by contraction of the triceps surae (Fig. 2.10).

Moments and Powers

At opposite toe off, the hip continues to have an internal extensor moment with power generation, as described earlier in ‘Initial Contact’. At the knee, the force vector lies behind the joint (Fig. 2.13), producing an external flexor moment. This is opposed by an internal extensor moment (Fig. 2.7) generated by the quadriceps muscles (Fig. 2.10). These contract eccentrically, absorbing power (K1 in Fig. 2.8). The line of the ground reaction force begins to move forwards along the foot (Fig. 2.13), causing the internal dorsiflexor moment at the ankle to become smaller and then to reverse, to become a plantarflexor moment (Fig. 2.7). Little power exchange occurs at the ankle at this time.

Mid-stance (Fig. 2.14)

General

Mid-stance is the period of the gait cycle between opposite toe off and heel rise, although the term has been used in the past to describe an event in the gait cycle when the swing phase leg passes the stance phase leg, corresponding to the swing phase event of feet adjacent, or the point in time when the anterior posterior component of the ground reaction force is zero. In the subject used for illustration, mid-stance occupied the period from 7% to 32% of the cycle; Fig. 2.14A represents 18% of the cycle and Fig. 2.14B the event when the anterior posterior reaction force is zero.

Upper Body

The period of mid-stance sees the trunk climbing to its highest point, about 20 mm above the mean level, and slowing its forward speed as the kinetic energy of forward motion is converted to the potential energy of height. The side-to-side motion of the trunk also reaches its peak during mid-stance, with the trunk being displaced about 20 mm from its central position, towards the side of the stance (right) leg. Like the feet, the arms pass each other during mid-stance, as each follows the motion of the opposite leg. The twisting of the trunk has now disappeared, as both the shoulder girdle and pelvis pass through neutral before twisting the other way.

Hip

During the mid-stance period, the hip continues to extend, moving from a flexed attitude to an extended one (Fig. 2.5). Concentric contraction of the gluteus maximus and the hamstrings ceases during this period, as hip extension is achieved by inertia and gravity. Throughout mid-stance and terminal stance, significant muscle activity about the hip joint takes place in the frontal plane. As soon as the opposite foot has left the ground, the pelvis is supported only by the stance phase hip. It dips down slightly on the side of the swinging leg, but its position is maintained by contraction of the hip abductors, especially the gluteus medius and tensor fascia lata.

Knee

During mid-stance, the knee reaches its peak of stance phase flexion and starts to extend again (Fig. 2.5), initially through concentric contraction of the quadriceps. The peak generally occurs between 15% and 20% of the gait cycle. Its magnitude varies from one individual to another and with the speed of walking, but it is commonly between 10 degrees and 20 degrees.

Ankle and Foot

The mid-stance rocker, also called the second rocker or ankle rocker, occurs during mid-stance and terminal stance. It is characterised by forward rotation of the tibia about the ankle joint as the foot remains flat on the floor, with the ankle angle changing from plantarflexion to dorsiflexion and the triceps surae contracting eccentrically. The actual angles vary with the method of measurement; most authors report larger angles than those seen in Fig. 2.5. External rotation of the tibia and coupled supination of the foot occur during mid-stance and terminal stance. The ground reaction force vector moves forwards along the foot from the time of foot flat onwards, and moving under the forefoot prior to heel rise. The movement of the foot into supination peaks in mid-stance and then begins to reverse towards pronation.

Moments and Powers

During mid-stance, the internal extensor moment at the hip, generated by contraction of the extensor muscles, declines and disappears, to be replaced by a moment in the opposite direction (Fig. 2.7). At the knee, the force vector remains behind the joint, producing an external flexor moment, opposed by an internal extensor moment (Fig. 2.7) due to quadriceps contraction (Fig. 2.10). According to Perry (1992), only the vasti, and not the rectus femoris, are active at this time. As the direction of knee motion changes from flexion to extension (Fig. 2.5), power generation takes place (K2 in Fig. 2.8). The ankle shows an increasing internal plantarflexor moment throughout mid-stance and into terminal stance (Fig. 2.7), as the force vector moves into the forefoot. This moment is generated by the triceps surae (Fig. 2.10), which are contracting eccentrically and absorbing power (A1 in Fig. 2.8).

Heel Rise (Fig. 2.15)

General

Heel rise, also called heel off, marks the transition from mid-stance to terminal stance. It is the time at which the heel begins to lift from the walking surface. Its timing varies considerably, both from one individual to another and with the speed of walking. The subject used for illustration shows heel rise at 32% of the gait cycle.

Upper Body

By heel rise, the trunk is falling from its highest point, reached during mid-stance. The lateral displacement over the supporting (right) leg also begins to diminish, in preparation for the transfer of weight back to the left leg. As the right hip extends and the leg moves backwards, the right side of the pelvis twists backwards with it and the arm and shoulder girdle on the right move forwards.

Hip

At heel rise and into terminal stance, the hip continues to extend (Fig. 2.5). Peak hip extension is reached around the time of opposite initial contact. The activity of the hip abductors in the frontal plane is still required to stabilise the pelvis, although this activity ceases prior to initial contact by the other foot.

Knee

The knee has an extension peak close to the time of heel rise (Fig. 2.5). Around this time, active ankle plantarflexion brings the ground reaction force forwards, moving it under the forefoot and in front of the knee joint (barely visible in Fig. 2.15). This attempts to extend the knee, an effect known as the plantarflexion/knee extension couple, which becomes very important in some pathological gaits. Contraction of the gastrocnemius augments the action of the soleus as far as the ankle joint is concerned, but it also acts as a flexor at the knee, preventing hyperextension and subsequently initiating knee flexion.

Ankle and Foot

The peak of ankle dorsiflexion is reached some time after heel rise (Fig. 2.5). The triceps surae initially maintains the ankle angle as the knee begins to flex, with movement into plantarflexion beginning late in terminal stance. The tibia becomes increasingly externally rotated and the foot becomes increasingly supinated, the two being linked through coupled motion at the subtalar joint. As the heel rises, the toes remain flat on the ground and extension occurs at the metatarsophalangeal (MTP) joints, along an oblique line across the foot known as the metatarsal break or toe break. From the time the heel rises, hindfoot inversion (adduction or varus angulation) is seen.

Moments and Powers

At heel rise, there is a small but increasing internal hip flexor moment (Fig. 2.7). The source of this internal flexor moment does not appear to have been fully explained in the literature, although it could be due to a combination of adductor longus and rectus femoris contraction and the stretching of ligaments as the hip moves into extension, with a resultant power absorption (H2 in Fig. 2.8). At the knee, quadriceps contraction has ceased prior to heel rise and the internal knee moment has reversed to become a flexor moment. According to Perry (1992), this occurs because the upper body moves forwards faster than the tibia. If the ankle joint were totally free, the forward motion of the body would simply dorsiflex the ankle. However, contraction of the triceps surae (Fig. 2.10) slows down and controls the forward motion of the tibia so that as the femur moves forwards, an external extensor moment is generated at the knee, which is opposed by an internal flexor moment (Fig. 2.7). Only small and variable power exchanges occur at the knee around heel rise. At the ankle, the internal plantarflexor moment continues to increase, as first the soleus and then both the soleus and gastrocnemius together (triceps surae in Fig. 2.10) contract increasingly strongly. The contraction is initially eccentric, with power absorption (A1 in Fig. 2.8).

Opposite Initial Contact (Fig. 2.16)

General

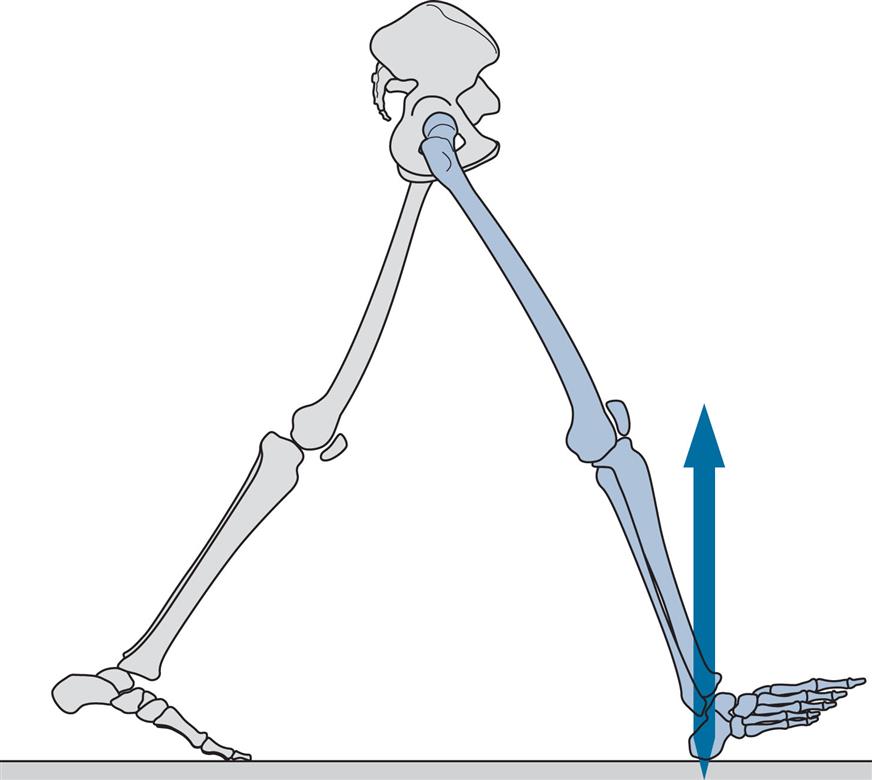

As might be expected, opposite initial contact in symmetrical gait occurs at close to 50% of the cycle. It marks the end of the period of single support and the beginning of pre-swing, which is the second period of double support. At the time of opposite initial contact, also known as opposite foot contact, the hip begins to flex, the knee is already flexing and the ankle is plantarflexing. The period between heel rise and toe off (terminal stance followed by pre-swing) is sometimes called the terminal rocker phase. This is appropriate, since the leg is now rotating forwards about the forefoot rather than about the ankle joint. Another term for this period is the push off phase. Perry (1974) objected to this term, suggesting instead the term roll-off, because ‘the late floor-reaction peak is the result of leverage by body alignment, rather than an active downward thrust’. However, it is clear that the push off is not simply passive, since it is the period during which the generation of power at the ankle is greatest (Winter, 1983). What is not clear is whether this power is used to accelerate the whole body (as suggested by Winter) or merely the leg (as suggested by Perry) or (as seems most likely) some combination of the two. Buczek et al. (2003) showed that power generation at the ankle is necessary to sustain normal walking. Using terms borrowed from a study on posture control by Mueller et al. (1994), normal walking involves an ‘ankle strategy’ but may be replaced by a ‘hip strategy’ in which subjects ‘decrease their push-off, pulling their leg forward from their hips’.

Upper Body

The attitude of the upper body at opposite initial contact resembles that described for initial contact, except that the trunk is now moving towards the left rather than the right, and the trunk is twisted so that the right shoulder and arm and the left side of the pelvis are forwards.

Hip

At opposite initial contact, the hip reaches its most extended position (typically between 10 degrees and 20 degrees of extension, depending on how it is measured), and motion reverses in the direction of flexion (Fig. 2.5). With the hip extended, the adductor longus acts as the primary hip flexor (Perry, 1992) and probably generates sufficient moment to initiate hip flexion, particularly when combined with tension in the stretched hip ligaments and the effects of gravity.

Knee

The knee is already moving into flexion by the time of opposite initial contact (Fig. 2.5). The force vector has moved behind the knee, aiding its flexion (Fig. 2.16), and the rectus femoris begins to contract eccentrically (included with the quadriceps in Fig. 2.10), to prevent flexion from occurring too rapidly. The term pull off has been used for the hip and knee flexion occurring during pre-swing.

Ankle and Foot

From before opposite initial contact until the foot leaves the ground at toe off, the ankle is moving into plantarflexion (Fig. 2.5), due to concentric contraction of the triceps surae (Fig. 2.10). Extension of the toes at the MTP joints continues and causes a tightening of the plantar fascia. The foot reaches its maximum supination, with hindfoot inversion (adduction or varus angulation) which is coupled with external tibial rotation. These various factors combine to lock the midtarsal joints, resulting in high stability of the foot for loadbearing (Inman et al., 1981; Rose and Gamble, 1994).

Moments and Powers

A peak of hip internal flexor moment occurs around opposite initial contact (Fig. 2.7). As stated earlier in ‘Opposite Initial Contact’, this probably results from a combination of adductor longus contraction, passive tension in the hip ligaments and gravity. As the direction of hip motion reverses from extension to flexion, power absorption (H2 in Fig. 2.8) is replaced by power generation (H3 in Fig. 2.8). During terminal stance, flexion of the knee brings the joint in front of the force vector (Fig. 2.16), reversing the external moment from extensor to flexor and hence changing the internal moment from flexor to extensor (Fig. 2.7). The eccentric contraction of the rectus femoris (included with the quadriceps in Fig. 2.10) limits the rate of knee flexion and results in power absorption (K3 in Fig. 2.8). At the ankle, the force vector is well in front of the joint at opposite initial contact (Fig. 2.16). The resultant high external dorsiflexor moment is opposed by a correspondingly high internal plantarflexor moment (Fig. 2.7), produced by concentric contraction of the triceps surae (Fig. 2.10). The result is a large generation of power (A2 in Fig. 2.8), which is the highest power generation of the entire gait cycle. The immediate effect of this power generation is to accelerate the limb forwards into the swing phase.

Toe Off (Fig. 2.17)

General

Toe off generally occurs at about 60% of the gait cycle (57% in the subject used for illustration). It separates pre-swing from initial swing and is the point at which the stance phase ends and the swing phase begins. The name terminal contact has been proposed for this event, since in pathological gait the toe may not be the last part of the foot to leave the ground.

Upper Body

The extreme rotations of the shoulders, arms and trunk all begin to return towards the neutral position, as the trunk gains height and moves towards the front (left) supporting foot.

Hip

As the foot leaves the ground, the hip continues to flex (Fig. 2.5). This is achieved by gravity and tension in the hip ligaments, as well as by contraction of the rectus femoris (included with the quadriceps in Fig. 2.10) and adductor longus.

Knee

By the time of toe off, the knee has flexed to around half of the angle it will achieve at the peak of swing phase flexion. This flexion is aided by the positioning of the ground reaction force vector well behind the knee (Fig. 2.17), although the magnitude of the force declines rapidly, reaching zero as the foot leaves the ground. The major part of knee flexion then results from hip flexion: the leg acts as a jointed ‘double pendulum’ so that as the hip flexes, the shank is ‘left behind’ due to its inertia, resulting in flexion of the knee. At the very beginning of the swing phase, the rectus femoris may contract eccentrically to prevent excessive knee flexion, particularly at faster walking speeds (Nene et al., 1999).

Ankle and Foot

The peak of ankle plantarflexion occurs just after toe off. The magnitude of plantarflexion depends on the method of measurement; it is 25 degrees in Fig. 2.5. Triceps surae contraction ceases prior to toe off and tibialis anterior contraction begins (Fig. 2.10), bringing the ankle up into a neutral or dorsiflexed attitude during the swing phase.

Moments and Powers

Around toe off, the hip still shows an internal flexor moment (Fig. 2.7), resulting from gravity, ligament elasticity and adductor longus and iliopsoas contraction. Since the hip is flexing at this time, power generation occurs (H3 in Fig. 2.8). During pre-swing and initial swing, hip flexion causes the knee to flex. This double pendulum motion results in an external flexor moment at the knee that is opposed by an internal extensor moment (Fig. 2.7) as the rectus femoris contracts eccentrically (included with the quadriceps in Fig. 2.10) to limit the speed at which the knee flexes. This eccentric contraction absorbs power (K3 in Fig. 2.8). At the ankle, the internal plantarflexor moment reduces rapidly during pre-swing as the magnitude of the ground reaction force declines, falling to zero as the foot leaves the ground at toe off (Fig. 2.7). The ankle power generation peak also declines to around zero during this period (Fig. 2.8).

Feet Adjacent (Fig. 2.18)

General

Feet adjacent separates initial swing from mid-swing. It is the time when the swinging leg passes the stance phase leg and the two feet are side by side. The swing phase occupies about 40% of the gait cycle and the feet become adjacent around the centre of this time; in the subject used for illustration, it occurred at 77% of the gait cycle. Alternative names for feet adjacent are foot clearance and mid-swing; the latter term is now applied to a period of the gait cycle rather than to a particular event.

Upper Body

When the feet are adjacent, the trunk is at its highest position and is maximally displaced over the stance phase leg (left). The arms are level with each other, with the left arm moving forwards and the right arm moving backwards.

Hip

The hip starts to flex prior to toe off, and by the time the feet are adjacent, it is well flexed (20 degrees in Fig. 2.5). This is achieved by a powerful contraction of the iliopsoas (Fig. 2.10), aided by gravity.

Knee

The flexion of the knee during the swing phase results largely from the flexion of the hip. As described earlier in ‘Toe Off’, the leg acts as a jointed pendulum, and no muscle contraction is necessary around the knee (thus enabling above-knee amputees to achieve swing phase knee flexion in their prosthetic limb). The peak swing phase knee flexion angle is usually between 60 degrees and 70 degrees (Fig. 2.5). It occurs before the feet are adjacent, by which time the knee has started to extend again. In fast walking, swing phase knee flexion is less than when walking at a natural speed, to shorten the swing phase. This is achieved by co-contraction of the rectus femoris and hamstrings (Gage, 2004).

Ankle and Foot

At the time the feet are adjacent, the ankle is moving from a plantarflexed attitude around toe off towards a neutral or dorsiflexed attitude in terminal swing (Fig. 2.5). Most of the shortening of the swing phase leg required to achieve toe clearance comes from flexion of the knee, but the ankle also needs to move out of plantarflexion. This movement requires contraction of the anterior tibial muscles, although the force of contraction is much less than that required (Fig. 2.10) to control foot lowering following initial contact. The closest approach of the toes to the ground occurs around the time the feet are adjacent. In normal walking, the toes clear the ground by very little; Murray (1967) found a mean clearance of 14 mm with a range of 1 to 38 mm. The degree of foot supination reduces following toe off, but the foot remains slightly supinated until the following initial contact.

Moments and Powers

As the hip moves into flexion, from opposite initial contact and through pre-swing and initial swing until the feet are adjacent, an internal flexor moment is present (Fig. 2.7). This is generated by gravity, the rectus femoris and the adductors, with the addition of ligament elasticity at the beginning of the movement and iliopsoas contraction towards its end (Fig. 2.10). Hip flexion, in response to this moment, results in the highest peak of power generation at the hip (H3 in Fig. 2.8), the power being used to accelerate the swinging leg forwards. The resultant kinetic energy is later transferred to the trunk, as the swinging leg is decelerated again at the end of the swing phase. Between toe off and feet adjacent, the knee continues to show a small internal extensor moment, as the rectus femoris (part of the quadriceps in Fig. 2.10) prevents the knee from flexing too rapidly in response to the external flexor moment transferred from the hip. Whilst the knee is still flexing, power absorption occurs (K3 in Fig. 2.8). Only very small moments and power exchanges are seen at the ankle, since only the weight of the foot is involved.

Tibia Vertical (Fig. 2.19)

General

The division between the periods of mid-swing and terminal swing is marked by the tibia of the swinging leg becoming vertical, which occurred at 86% of the gait cycle in the subject used for illustration. Terminal swing is also known as reach.

Upper Body

When the tibia is vertical on the swing phase leg (right), the trunk has begun to lose vertical height and to move from its maximum displacement over the supporting (left) leg back towards the midline. The left arm is now in front of the right and the right side of the pelvis is a little in front of the left side.

Hip

Tibia vertical marks approximately the time at which further hip flexion ceases; the subject used for illustration has a hip angle of about 27 degrees of flexion from tibia vertical to the next initial contact (Fig. 2.5). The hamstrings contract increasingly strongly during terminal swing (Fig. 2.10) to limit the rate of knee extension whilst maintaining the hip joint in this flexed position.

Knee

Tibia vertical occurs during a period of rapid knee extension, as the knee goes from the peak of swing phase flexion prior to feet adjacent, to more or less full extension prior to the next initial contact (Fig. 2.5). This extension is largely passive, being the return swing of the lower (shank) segment of the double pendulum referred to earlier in ‘Toe Off’. Eccentric contraction of the hamstrings prevents this motion from causing an abrupt hyperextension of the knee at the end of swing (Fig. 2.10).

Ankle and Foot

Once toe clearance has occurred, generally before the tibia becomes vertical, the ankle attitude becomes less important: it may be anywhere between a few degrees of plantarflexion and a few degrees of dorsiflexion, prior to the next initial contact (Fig. 2.5). The tibialis anterior continues to contract to hold the ankle in position, but its activity usually increases prior to initial contact in anticipation of the greater contraction forces which will be needed during the loading response (Fig. 2.10).

Moments and Powers

At the hip, by the time of tibia vertical, an increasing internal extensor moment is seen (Fig. 2.7); this is largely generated by the contraction of the hamstrings, although the gluteus maximus also begins to contract prior to the next initial contact (Fig. 2.10). This moment probably permits the transfer of momentum from the swinging leg to the trunk, recovering some of the kinetic energy imparted to the leg in initial swing (H3 in Fig. 2.8). Since the hip angle is essentially static during terminal swing, very little power exchange occurs at the joint itself. The knee demonstrates an increasing internal flexor moment (Fig. 2.7), which is generated by eccentric contraction of the hamstrings (Fig. 2.10), with power absorption (K4 in Fig. 2.8). This occurs in response to an external extensor moment generated by the inertia of the swinging shank, which would hyperextend the knee if it were not checked. The ankle moment remains negligible (Fig. 2.7), with very little power exchange (Fig. 2.8).

Terminal Foot Contact (Fig. 2.11)

The gait cycle ends at the next initial contact of the same foot (in this case, the right foot). Because it is confusing to refer to the end of the cycle as initial contact, it is sometimes known as terminal foot contact.

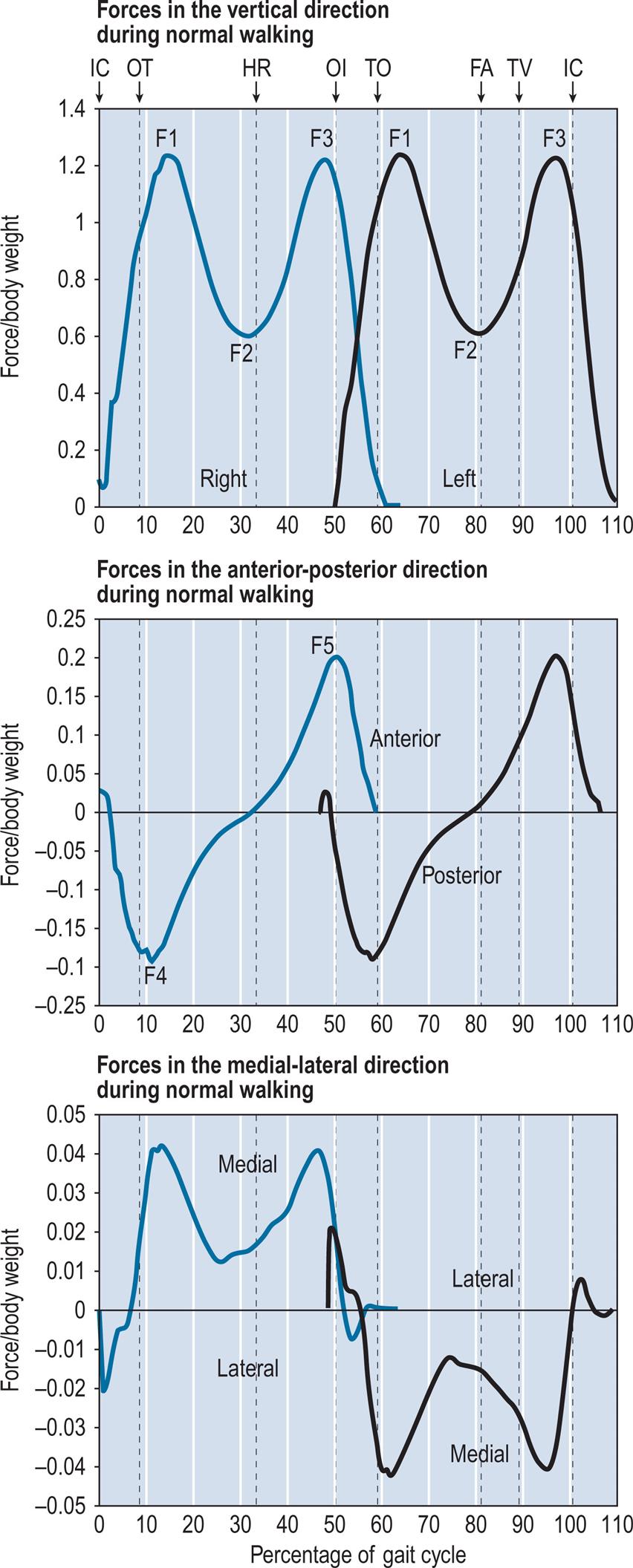

Ground Reaction Forces

The force platform (or force plate) is an instrument commonly used in gait analysis. It gives the total force applied by the foot to the ground, although it does not show the distribution of different parts of this force (e.g., heel and forefoot) on the walking surface. Some force platforms give only one component of the force (usually vertical), but most give a full three-dimensional description of the ground reaction force vector. The electrical output signals may be processed to produce three components of force (vertical or Fz, medial-lateral or Fy and fore-aft [anterior-posterior] or Fx). As force plates can be mounted in multiple directions, it is best to describe the forces as Fv, FA-P and FM-L to avoid confusion. The force plate also produces the two coordinates of the centre of pressure and the moments about the vertical axis. The centre of pressure is the point on the ground through which a single resultant force appears to act, although in reality the total force is made up of innumerable small force vectors, spread out across a finite area on the surface of the platform.

Since the ground reaction force is a three-dimensional vector, it would be preferable to display it as such for the purposes of interpretation. Unfortunately, this is seldom practical. The most common form of display is that shown in Fig. 2.20, where the three components of force are plotted against time for the walk shown in the previous figures. The sign convention used in Fig. 2.20 is the same as that used by Winter (1991), where the ground reaction force is positive upwards, forwards and to the right. Regrettably, there is no general agreement on sign conventions.

The vertical force shows a characteristic double hump, which results from an upward acceleration of the centre of gravity during early stance (F1), a reduction in downward force as the body ‘flies’ over the leg in mid-stance (F2) and a second peak due to deceleration (F3) as the downward motion is checked in late stance. The fore-aft (or anteroposterior) trace from the right foot shows braking during the first half of the stance phase (F4) and propulsion during the second half (F5). The left foot shows the same pattern, but with the direction of the lateral force reversed. The lateral component of force is generally very small; for most of the stance phase of the right foot, the ground reaction force accelerates the centre of gravity towards the left side of the body, and during the stance phase of the left foot, the acceleration is towards the right side.

Plots of this type are difficult to interpret and encourage consideration of the force vector as separate components rather than as a three-dimensional whole. The butterfly diagram shown in Fig. 2.9 is an improvement on this, since it combines two of the force components (vertical and fore-aft) with the centre of pressure in the fore-aft direction. It also preserves information on timing, since the lines representing the force vector are at regular intervals (10 ms in this case). Butterfly diagrams for the frontal and transverse planes are more difficult to interpret and are seldom used.

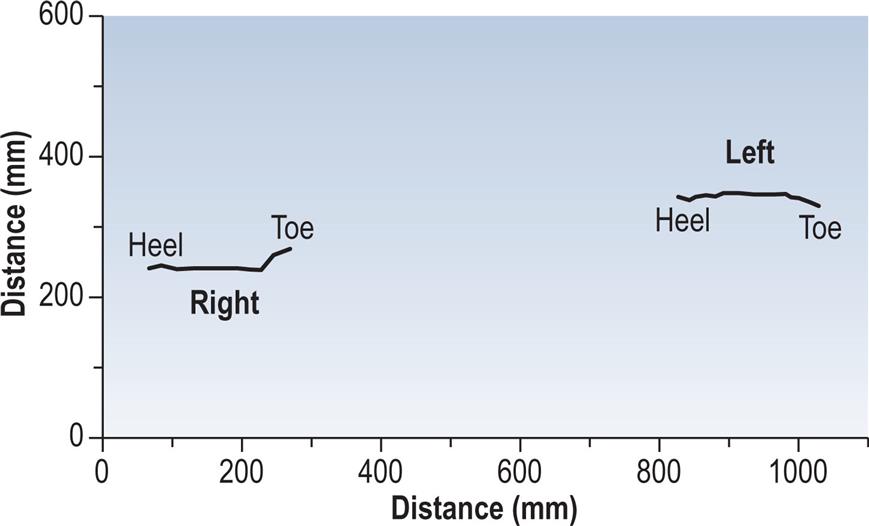

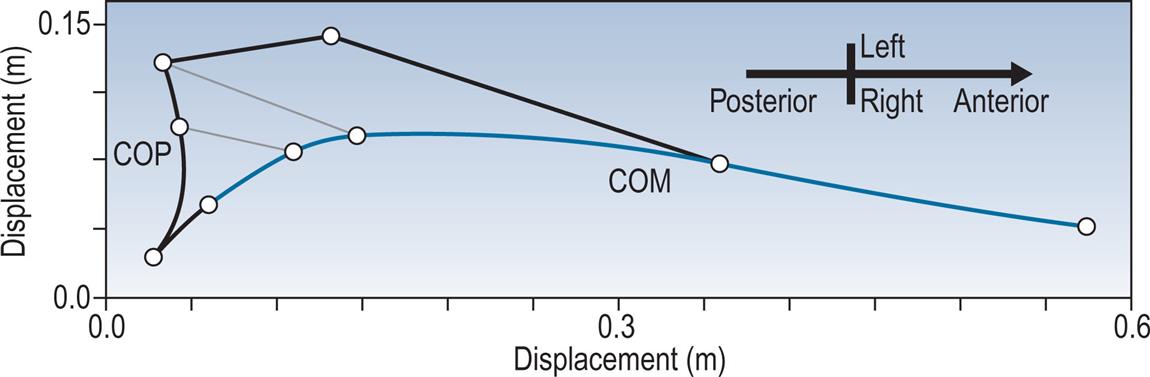

The other type of information commonly derived from the force platform is the position of the centre of pressure of the two feet on the ground, as shown in Fig. 2.21, again, for the same walk. This may be used to identify abnormal patterns of foot contact, including an abnormal toe-out or toe-in angle. The step length and walking base can also be measured from this type of display, provided there is an identifiable initial contact.

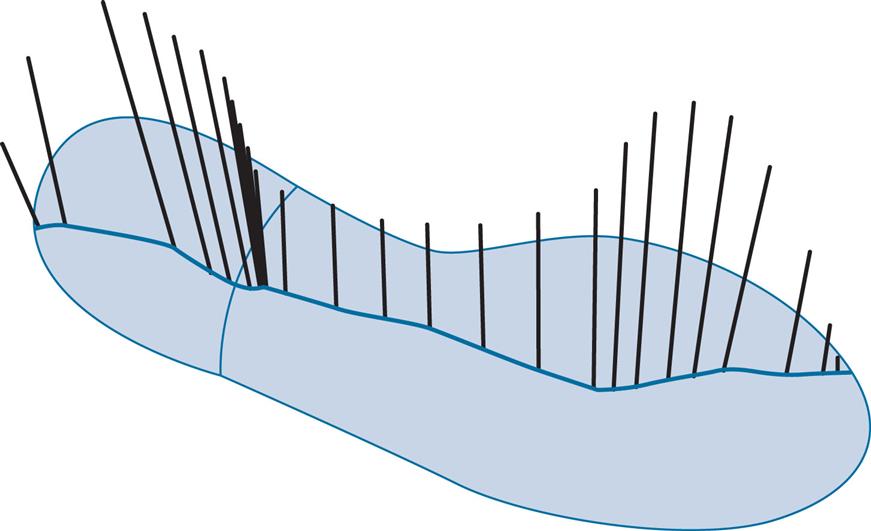

Should the pattern of foot contact be of particular interest, it is preferable to combine the data on the centre of pressure with an outline of the foot obtained by some other means (such as chalk or ink on the floor). This type of display, with the addition of a sagittal plane representation of the ground reaction force vector, is shown in Fig. 2.22 for a normal male subject wearing shoes. The trace shows initial contact at the back of the heel on the lateral side, with progression of the centre of force along the middle of the foot to the metatarsal heads, where it moves medially, ending at the hallux. The spacing of the vectors shows how long the centre of pressure spends in any one area. It is worth noting that there is a cluster of vectors just in front of the edge of the heel where the shoe is not in contact with the ground, again pointing out the fact that the centre of pressure is merely the average of a number of forces acting beneath the foot.

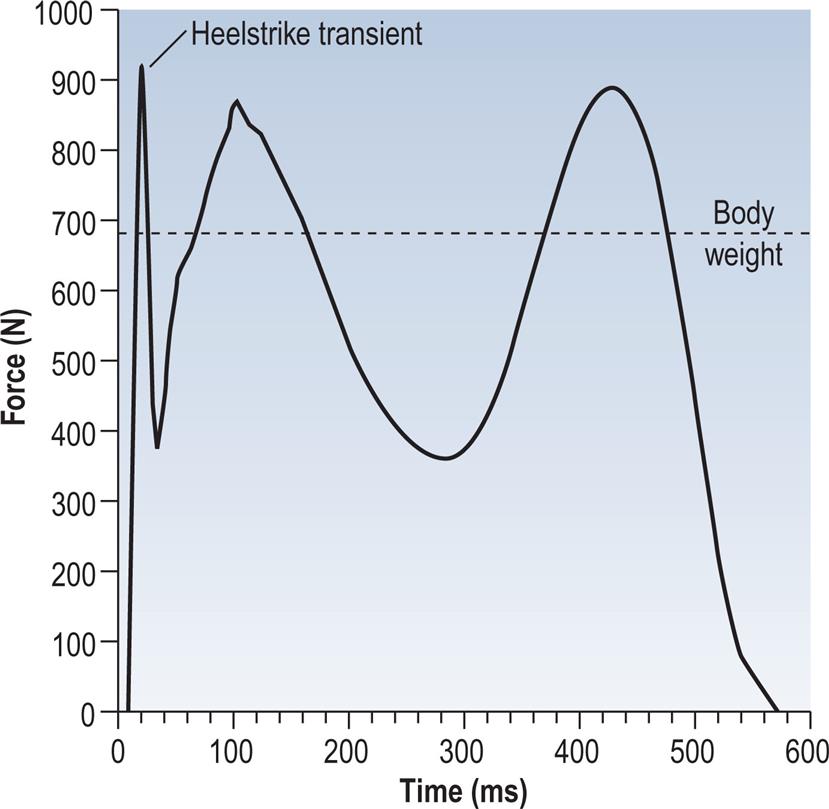

There is considerable variation among individuals as to how much force is applied to the ground at initial contact. In some cases this leads to what is known as a heelstrike transient. This is caused by the swinging limb hitting the ground with a backward velocity, causing a rapid impact peak as the leg decelerates. Fig. 2.23 shows the vertical component of the ground reaction force from a fast walk, in hard-heeled shoes, by an individual with a marked heelstrike. The data were recorded at 1000 Hz from a Bertec force platform, which has a particularly high-frequency response. It has been suggested that transient forces in the joints, resulting from the heelstrike, may cause degenerative arthritis (Radin, 1987). The heelstrike transient represents the transfer of momentum from the moving leg to the ground. It is a fairly short event, typically lasting 10 to 20 ms, and can only be observed using measuring equipment with a fast enough response time. A review article on the heelstrike transient and related topics was published by Whittle (1999).

Moments about the vertical axis are seldom reported. In comparing these moments between normal children and children with clubfeet, Sawatzky et al. (1994) were surprised to find only small, statistically insignificant differences. However, as will be explained in Chapter 4, Methods of Gait Analysis, these moments are largely a result of the acceleration and deceleration of the swing phase leg, and only minor changes could be expected to be introduced by the foot on the ground.

Support Moment

Winter (1980) coined the term support moment to describe the sum of the sagittal plane moments about the hip, knee and ankle joints:

where MS, MH, MK and MA are the support, hip, knee and ankle moments, respectively.

Winter noted that the support moment was far less variable than its individual components, suggesting that a decreased moment about one joint could be compensated for by an increased moment about one or both of the other joints. However, it was difficult to interpret this in biomechanical terms, since the sign convention was based on flexion and extension rather than on clockwise and anticlockwise moments, which caused the direction of the knee moment to be opposite to that of the hip and ankle moments. Hof (2000) published a justification for the support moment and suggested that it is responsible for preventing collapse of the knee. Based on his analysis, he suggested the following revised formula for its calculation:

Fig. 2.24 illustrates the support moment calculated from the sagittal plane hip, knee and ankle internal moments from the normal subject used for illustration throughout this chapter, using the formula suggested by Hof (2000). Anderson and Pandy (2003) suggested that a better alternative to the support moment would be the sum of the vertical components of force from individual muscles during walking.

Energy Consumption

It is relatively easy to measure the energy consumption of a vehicle, but much more difficult to make equivalent measurements of human walking, for two reasons. Firstly, there is a clear relationship between the fuel level in the tank of a vehicle and the amount of energy that has been used, whereas knowing how much food a person has eaten gives no information on the energy consumed in a particular activity. Secondly, a vehicle which is switched off uses no energy, whereas people use metabolic energy all the time, whether they are walking or not.

The first problem, that of measuring fuel consumption, can be solved by measuring not the fuel consumed but the oxygen which is used to oxidise it. Measurements of oxygen uptake, while not particularly pleasant for the subject (who has to wear a face mask or mouthpiece), are nonetheless perfectly practical and are used routinely to measure the metabolic cost of different activities.

The second problem, the lack of a suitable baseline for energy consumption measurements in humans, is not easy to solve and requires a different way of thinking about the topic. The energy used by a person who is walking can be divided into three parts:

- 1. The muscles used for walking consume energy, as they accelerate and decelerate the trunk and the limb segments in different directions.

- 2. There is an ‘overhead’ involved in walking, in that the expenditure of energy by the muscles involves increased activity by the heart and the muscles used in breathing, which themselves use energy. Energy is also expended in maintaining the upright posture.

- 3. The basal metabolic rate (BMR) is the energy expended by the body at rest to maintain normal body functions. This continual work makes up about 60% to 70% of the energy we use and includes respiration, cardiovascular function and the maintenance of body temperature.

The relationship between metabolic energy and physical energy is very complicated. As explained in Chapter 1, Basic Sciences, if a muscle undergoes an isometric contraction, it still uses energy, although its length does not change and the physical work it does is zero. In an eccentric contraction, when it lengthens under tension it uses metabolic energy, when in physical terms one would expect it to gain energy rather than to lose it.

In the past it has been usual to estimate the mechanical efficiency of walking by looking at the difference in oxygen consumption between the basal state and walking at a given speed. Inman et al. (1981) and Rose and Gamble (1994) suggested that it is more realistic to use standing or very slow walking as the baseline for measurements of faster walking. Despite these uncertainties, a figure of 25% is often quoted for the efficiency of the conversion of metabolic energy into mechanical energy in a wide range of activities, including walking. A comprehensive review of the energy expenditure of normal and pathological gait was given by Waters and Mulroy (1999).

The energy requirements of walking can be expressed in two ways: the energy used per unit time and the energy used per unit distance. Since energy expenditure is usually inferred from the oxygen used, these are generally known as oxygen consumption and oxygen cost, respectively.