Chapter 7:

Classification of Joints

Classification of Joints

Section 7.1. Anatomy of a Joint

- • Structurally, a joint is defined as a place of juncture between two or more bones. 1 At this juncture, the bones are joined to one another by soft tissue.

-

- • In other words, structurally, a joint is defined as a place where two or more bones are joined to one another by soft tissue.

- • A typical joint involves two bones; however, more than two bones may be involved in a joint. For example, the elbow joint incorporates three bones: the humerus, radius, and ulna. Any joint that involves three or more bones of the skeleton is called a compound joint. In contrast, the term simple joint is sometimes used to describe a joint that has only two bones. 2

- • The type of soft tissue that connects the two bones of a joint determines the structural classification of the joint (Box 7-1). (For more information on the structural classification of joints, see Section 7.6.)

- • The following are the three major structural classifications of a joint 3 :

- • A joint is also known as an articulation. 4

- • Figure 7-1 illustrates the components of a typical joint of the body. (Note: It should be stated that there really is no typical joint of the body. As will be seen later in the chapter, many different types of joints exist, both structurally and functionally.)

An illustration depicts the cut-away diagram of a typical joint. The two bones are held together by fluid and ligament between them. The parts of the diagram labeled from top to bottom are as follows: bone, muscle, ligament, fibrous capsule, synovial membrane, articular cartilage, and the joint cavity (contains synovial fluid).

Section 7.2. Physiology of a Joint

- • The main function of a joint is to allow movement.

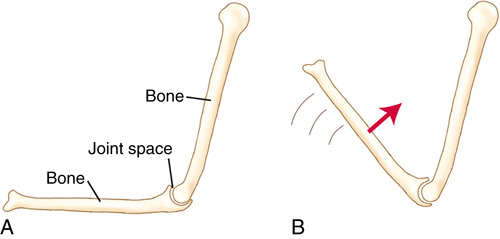

- • As we have seen, a joint contains a space between the two bones. At this space, the bones can move relative to each other. Figure 7-2 illustrates motion at a joint.

- • There actually are joints in the human body that do not allow movement. However, they exist because they did allow movement in the past. An example would be the joint between a tooth and the maxilla. When the tooth was “coming in,” movement was necessary for the tooth to descend and erupt through the maxilla. However, now no movement occurs between the tooth and the maxilla. Another example that is often given is that of the suture joints of the skull. These joints require movement to allow the passage of the baby’s head through the birth canal of the mother. However, once the child has been born and grows to maturity, movement is no longer needed at these suture joints and they often fuse. It must be emphasized that if no movement were needed at a certain point in the body, there would be no need to have a joint there. Structurally, our body would be far more stable if we had a solid skeleton that was made up of one bone, with no joints located in it. However, we need movement to occur, therefore at each location where movement is necessary, a break or space exists between bones and a joint is formed. It can be useful to think of the Tin Man in the film The Wizard of Oz. When he was first found, it was as if he had no joints at all because the spaces of the joints were all rusted together. Then as Dorothy applied oil to each spot, the joints began to function and could once again allow movement.

-

FIGURE 7-2 Illustration of how motion of one bone relative to the other bone of the joint occurs around the space of the joint. - • When we say that the main function of a joint is to allow movement, the word allow must be emphasized. A joint is a passive structure that allows movement; it does not create the movement.

- • As will be learned in later chapters, it is the musculature that crosses the joint that contracts to create the movement that occurs at a joint.

- • In addition, it is the ligaments/joint capsules that connect the bones to each other to keep the bones from moving too far from each other (i.e., dislocating) and therefore limit the movement at a joint.

Section 7.3. Joint Mobility Versus Joint Stability

- • By definition, a joint is mobile. However, a joint must also be sufficiently stable to maintain its structural integrity (i.e., it does not dislocate).

- • Every joint of the body finds a balance between mobility and stability 5 (Box 7-3).

- • The more mobile a joint is, the less stable it is.

- • The more stable a joint is, the less mobile it is.

- • Therefore, mobility and stability are antagonistic concepts; more of one means less of the other!

- • The shape of the bones of the joint

- • The ligament/joint capsule complex of the joint (Note: Ligaments and joint capsules are both made up of the same fibrous material, and both act to limit motion of a joint; therefore, they can be grouped together as the ligament/joint capsule complex.)

- • The musculature of the joint.

- • Because a muscle crosses a joint (by attaching via its tendons to the bones of the joint), the more massive a muscle is, the more stability it lends to the joint. However, this greater stability also means less mobility. For this reason, people who work out and have very large muscle mass are sometimes referred to as being muscle-bound. If the baseline tone of the musculature that crosses a joint is high (i.e., the muscles are tight), stability increases even more and mobility decreases commensurately. (For more information regarding the concept of stabilization of a joint by a muscle, see Chapter 14, Section 14.7.)

- • These concepts are well illustrated by comparing the mobility/stability of the shoulder joint with that of the hip joint. The shoulder joint and hip joint are both ball-and-socket joints. However, the shoulder joint is much more mobile and much less stable than the hip joint; conversely, the hip joint is much more stable and much less mobile than the shoulder joint.

- 1. The bony shape of the socket of the shoulder joint (i.e., the glenoid fossa of the scapula) is much shallower than the socket of the hip joint (i.e., the acetabulum) (Figure 7-3).

- 2. The ligament/joint capsule complex of the shoulder joint is much looser than the ligament/joint capsule complex of the hip joint.

- 3. The musculature crossing the shoulder joint is less massive than the musculature crossing the hip joint.

-

- • The advantage of the greater mobility of the shoulder joint is the increased motion, allowing the hand to be placed in a greater variety of positions. However, the disadvantage of the greater mobility of the shoulder joint is a higher frequency of injury.

- • The advantage of the greater stability of the hip joint is the low frequency of injury. The disadvantage of the greater stability of the hip joint is the inability to place the foot in a great variety of positions.

- • It is actually possible to have great mobility and great stability at a joint. This is accomplished via the soft tissues of the joint. If the muscles and the ligament/joint capsule tissues are loose, mobility is increased. However, if the muscles are developed and strong, stability is also increased. Dancers are an excellent example of people whose joints are both flexible and stable.

-

FIGURE 7-3 A, Shallow socket (glenoid fossa of the scapula) of the shoulder joint. B, Deep socket (acetabulum of the pelvis bone) of the hip joint. Shallowness/depth of the socket affects the relative mobility versus stability of the joint. -

FIGURE 7-4 Joints of the lower extremity help to absorb shock when a person lands on the ground after having jumped up into the air. All weight-bearing joints, including the joints of the spine, would help with shock absorption in this scenario.

Section 7.4. Joints and Shock Absorption

- • In addition to allowing motion to occur, a joint may also serve the purpose of shock absorption for the body. In addition to the soft tissue located between the bones of a joint, many joints also have fluid located in a capsule of the joint. This fluid can be very helpful toward absorbing shock waves that are transmitted through the joint. 6 (See Section 7.9 for a discussion of synovial joints, which have fluid located within a joint cavity.)

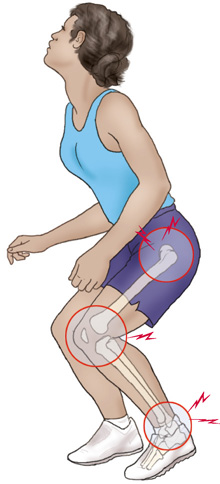

- • Although all joints have the ability to absorb shock, lower extremity and spinal joints are especially important for providing shock absorption, given the forces that enter our body whenever we walk, run, or jump and hit the ground. 7 The force of our body weight hitting the ground causes an equivalent force to be transmitted up through our body. 1 The fluid located in the joints of our lower extremities and the joints of our spine can help to absorb and dampen this shock. Figure 7-4 illustrates this concept.

- • Note: Our joints function to absorb and dampen shock in a similar manner to the shock absorbers of a car. A car’s shock absorber is a cylinder filled with fluid. When the car hits a pothole or a bump, the fluid within the shock absorber absorbs and dampens the compression force that occurs (i.e., the shock wave that would otherwise be transmitted to the rest of the car, as well as the people sitting within the car).

Section 7.5. Weight-Bearing Joints

- • Many joints of the body are weight-bearing joints. A joint is a weight-bearing joint if the weight of the body is borne through that joint.

- • Many textbooks describe weight-bearing as another function of some of the joints of our body. Although it is certainly true that many of the joints of our body have the additional function of bearing weight, bearing weight is not a reason for a joint to exist in the first place. Weight-bearing places a stress on a joint that requires greater stability. By definition, a joint allows movement, which, by definition, decreases stability. If weight-bearing is the goal, and stability is therefore needed, the body would be better off not having a joint in that location. If, for example, the lower extremity did not have a knee joint, and the entire lower extremity were one bone instead of having a separate femur and tibia, the lower extremity would be much more stable and able to bear the weight of the body through it more efficiently. Having the knee joint allows movement there and decreases the stability of the lower extremity; therefore, it does not help with weight-bearing. Of course, once present, the knee joint now has the added responsibility of bearing weight. Perhaps it is better to say that it is a characteristic, not a function, of some joints that they bear weight.

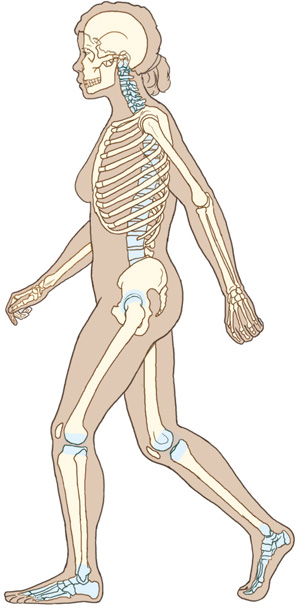

- • Almost all joints of the lower extremities, and the joints of the spine are weight-bearing joints 7 (Box 7-4). In addition to allowing movement, these joints must also be able to bear the weight of the body parts that are above them.

- • Because of the stress of bearing weight, weight-bearing joints tend to be more stable and less mobile.

- • Because a greater proportion of body weight is above joints that are lower in the body, the amount of weight-bearing stress that a joint must bear is greater for the joints that are lower in the body. For example, the upper cervical vertebrae need bear only the weight of the head; however, the lower lumbar vertebrae must bear the entire weight of the head, neck, trunk, and upper extremities. The joints of the ankle and foot have the greatest combined weight of body parts above them and therefore bear the greatest weight.

- • Potentially, the weight-bearing stress on the ankle and foot joints is the greatest. However, because two lower extremities exist, the weight-bearing load on them is divided by two when a person is standing on both feet. Of course, when a person is standing on only one foot, the entire weight of the body is borne through the joints of that side’s lower extremity.

- • Upper extremity joints (and some other miscellaneous joints) are not usually weight-bearing joints.

An illustration of a skeleton structure depicts the weight-bearing joints of the body wherein the joints that are responsible for weight bearing are indicated in different color. The joints indicated include the spine, knee, ankle, hip and neck.

Section 7.6. Joint Classification

Structural Classification of Joints

- • Structurally, joints can be divided into the following three categories: (1) fibrous, (2) cartilaginous, and (3) synovial 3 (Table 7-1).

-

- • A joint in which the bones are held together by a dense fibrous connective tissue is known as a fibrous joint.

- • A joint in which the bones are held together by either fibrocartilage or hyaline cartilage is known as a cartilaginous joint.

- • A joint in which the bones are connected by a joint capsule, which is composed of two distinct layers (an outer fibrous layer and an inner synovial layer), is known as a synovial joint.

- • It is worth noting that fibrous and cartilaginous joints have no joint cavity; synovial joints enclose a joint cavity.

-

Classification of Joints by Structure

Joints Without a Joint Cavity

- • Fibrous: Fibrous joints are joints in which dense fibrous tissue attaches the two bones of the joint to each other.

- • Cartilaginous: Cartilaginous joints are joints in which cartilaginous tissue attaches the two bones of the joint to each other. 8

Joints With a Joint Cavity

- • Synovial: Synovial joints are joints in which a joint capsule attaches the two bones of the joint to each other. 8

Functional Classification of Joints

- • Functionally, joints can be divided into three categories: (1) synarthrotic, (2) amphiarthrotic, and (3) diarthrotic 6 (Table 7-2).

-

- • As in all categories of classification, alternatives exist. Another common classification of joints divides them into only two functional categories: (1) synarthroses, lacking a joint cavity, and (2) diarthroses, possessing a joint cavity. 7 Synarthroses are then divided into synostoses (united by bony tissue), synchondroses (united by cartilaginous tissue), and syndesmoses (united by fibrous tissue). 9 Diarthroses are synovial joints (united by a capsule enclosing a joint cavity).

-

Classification of Joints by Function Synarthrotic Synarthrotic joints allow very little or no movement. Amphiarthrotic Amphiarthrotic joints allow a moderate but limited amount of movement. Diarthrotic Diarthrotic joints are freely moveable and allow a great deal of movement. - • A joint that allows very little or no movement is known as a synarthrotic joint 9 (synarthrosis; plural: synarthroses).

- • A joint that allows a moderate but limited amount of movement is known as an amphiarthrotic joint 6 (amphiarthrosis; plural: amphiarthroses).

- • A joint that is freely moveable and allows a great deal of movement is known as a diarthrotic joint 9 (diarthrosis; plural: diarthroses).

- • It is worth noting that although general agreement exists among sources regarding the classification of joints into three categories based on movement, the exact delineation among these relative amounts of movement may differ at times.

- • It is a major principle of anatomy and physiology that structure and function are intimately related. It is often said that structure determines function. That is, the anatomy of a body part determines its physiology. Relating this to the study of joints, the structure of a joint determines the motion possible at that joint.

- • Therefore, although joints may be divided into three categories by structure, and into three categories by function (i.e., movement), it is important to realize that these three structural and three functional categories are related. They are only different categories based on whether the perspective is that of an anatomist, who looks at structure, or that of a physiologist or kinesiologist, who looks at function.

- • Therefore, the following general correlations can be made (Table 7-3):

- • Fibrous joints are synarthrotic joints. 7

- • Cartilaginous joints are amphiarthrotic joints. 6

- • Synovial joints are diarthrotic joints. 7

Section 7.7. Fibrous Joints

- • Fibrous joints are joints in which the soft tissue that unites the bones is a dense fibrous connective tissue; hence, a fibrous joint has no joint cavity (Table 7-4; Figure 7-6).

- • Fibrous joints typically permit very little or no movement; therefore, they are considered to be synarthrotic joints.

- • Three types of fibrous joints exist 5 :

(A) shows the fibrous tissue that unites the two bones of a fibrous joint. (B) shows the cross-sectional view of the interosseus membrane that is located between the radius and the ulna. (C) shows the anterior view of the interosseus membrane of the forearm that unites the radius and the ulna.

Syndesmosis Joints

- • In a syndesmosis joint, a fibrous ligament or fibrous aponeurotic membrane unites the bones of the joint. 5

- • Syndesmoses permit a small amount of movement between the two bones of the joint.

- • The interosseus membrane between the radius and ulna is an example of a syndesmosis joint (see Figure 7-6, B and C).

- • The interosseus membrane between the tibia and fibula is another example of a syndesmosis joint.

Suture Joints

- • In a suture joint, a thin layer of fibrous tissue unites the two bones of the joint. 5

- • Suture joints are found only in the skull (Figure 7-7).

- • A small amount of movement is permitted at these joints early in life.

- • The principal purpose of the suture joints is to allow the bones of the skull of a baby to move relative to one other to allow easier passage through the birth canal during delivery.

- • Suture joints are usually considered to allow little or no movement later in life, but controversy exists regarding this (Box 7-5).

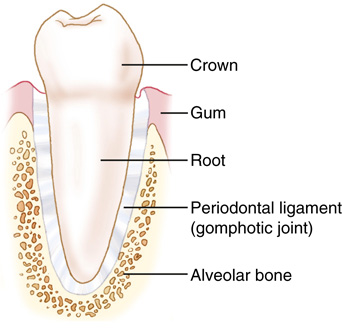

Gomphosis Joints

- • In a gomphosis joint, fibrous tissue unites two bony components with surfaces that are adapted to each other like a peg in a hole 5 (Figure 7-8).

- • This type of joint is found only between the teeth and the mandible, or between the teeth and the maxilla.

- • Gomphoses permit movement of the teeth relative to the mandible or the maxilla early in life, but in an adult no movement is permitted in a gomphosis joint.

(A) shows the skeletal structure of the head (skull) wherein a joint near the dimple is indicated as a fibrous suture. (B) shows the cross-sectional view of the same suture joint that exists in between the bones of the skull.

A cut-away diagram shows the view of the joint between a tooth and the adjacent bone. The following parts are labeled from top to bottom: crown, gum, root, periodontal ligament (gomphotic joint), and the alveolar bone.

Section 7.8. Cartilaginous Joints

- • Cartilaginous joints are joints in which the soft tissue that unites the bones is cartilaginous connective tissue (usually fibrocartilage, but occasionally hyaline cartilage); hence, a cartilaginous joint has no joint cavity. 5

- • Cartilaginous joints typically permit a moderate but limited amount of movement; therefore, they are considered to be amphiarthrotic joints.

- • Two types of cartilaginous joints exist 6 :

Symphysis Joints

- • In a symphysis joint, fibrocartilage in the form of a disc unites the bodies of two adjacent bones. 5 (The term body of a bone is usually used to refer to the largest aspect of a bone.) These fibrocartilaginous discs can be quite thick. Consequently, although not allowing the extent of motion that a diarthrotic synovial joint allows, cartilaginous joints can allow a moderate amount of motion.

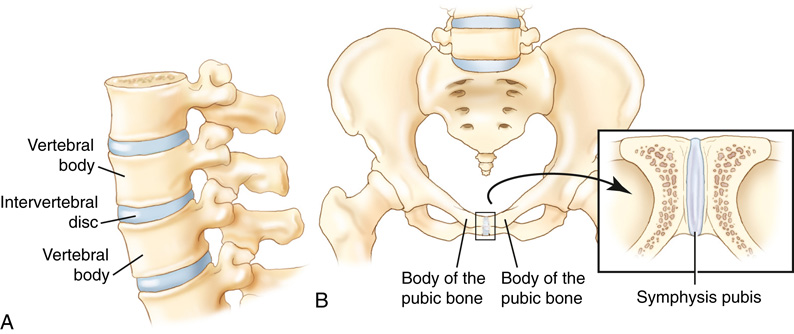

- • An example of a cartilaginous symphysis joint is the intervertebral disc joint of the spine (Figure 7-9, A).

-

- • Technically, an intervertebral disc joint could be considered to have a joint cavity filled with fluid. The cavity is enclosed by the fibrocartilaginous annular fibers and the fluid is the “pulpy” nucleus pulposus. (For more on intervertebral discs, see Chapter 8, Section 8.4.)

- • Another example is the pubic symphysis of the pelvis (Figure 7-9, B).

Synchondrosis Joints

- • In a synchondrosis joint, hyaline cartilage unites the two bones of the joint. 5

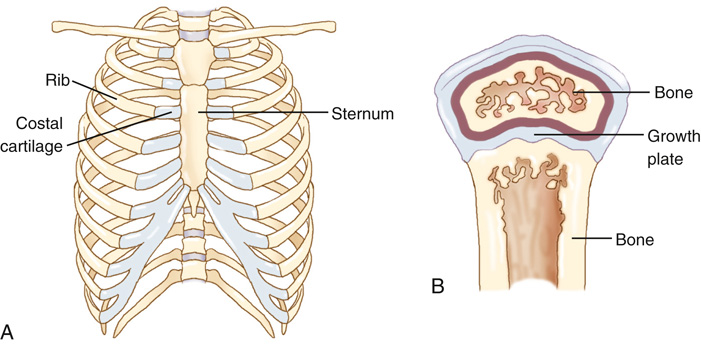

- • An example of a cartilaginous synchondrosis joint is the cartilage (i.e., costal cartilage) that is located between a rib and the sternum (Figure 7-10, A).

- • The growth plate (i.e., epiphysial disc) of a growing bone may also be considered to be another type of synchondrosis joint (Figure 7-10, B).

-

- • Eventually a growth plate ossifies and only a remnant, the epiphysial line, remains. 1 Many sources do not consider the epiphysial disc of a growing bone to be another type of synchondrosis joint, because the main purpose of the growth plate is growth, not movement. 1 (For more information on growth plates, see Chapter 3, Section 3.6.)

(A) shows a lateral view of the intervertebral disc joint located between the adjacent vertebral bodies of the spine. (B) shows the anterior view of the pelvis with a close up view in the inset box which illustrates the middle joint located between the right and left bodies of the pubic bones of the pelvis. This joint is labeled as symphysis pubis in the inset.

(A) shows the anterior view of the ribcage and the following parts are labeled: rib, coastal cartilage, and sternum. (B) shows the growth plate between the adjacent regions of the bony tissue of a developing long bone.

Section 7.9. Synovial Joints

Components of a Synovial Joint

- • The bones of a synovial joint are connected by a joint capsule, which encloses a joint cavity. 5

- • This joint capsule is composed of two distinct layers: (1) an outer fibrous layer and (2) an inner synovial membrane layer 5 (Table 7-5).

- • The inner synovial membrane layer secretes synovial fluid into the joint cavity, also known as the synovial cavity. 6

- • Furthermore, the articular ends of the bones are capped with articular cartilage (i.e., hyaline cartilage). 3

- • Synovial joints are the only joints of the body that possess a joint cavity.

- • By virtue of the presence of a joint cavity, synovial joints typically allow a great deal of movement; hence, they are considered to be diarthrotic joints.

Roles of Ligaments and Muscles in a Synovial Joint

Ligaments

- • By definition, a ligament is a fibrous structure (made primarily of collagen fibers) that attaches from any one structure of the body to any other structure of the body 10 (except a muscle to a bone).

- • In the musculoskeletal field, a ligament is defined more narrowly as attaching one bone to another bone.

-

FIGURE 7-11 Examples of synovial joints. A, Anterior view frontal-plane cross-section of the shoulder joint. B, Lateral view sagittal-plane cross-section of the elbow (humeroulnar) joint. C, Lateral view sagittal-plane cross-section of the knee joint. Three cut-away diagrams are marked A through C. (A) shows the anterior view frontal plane cross-section of the shoulder joint. The following points are labeled: fibrous capsule, synovial membrane, glenoid labrum, articular cartilage, synovial cavity, subacromial bursa, supraspinatus tendon, deltoid, and head of the humerus. (B) shows the lateral view sagittal-plane cross section of the elbow point. The following are labeled: fat pad, fibrous capsule, distal humerus, synovial membrane, synovial cavity, articular cartilage, and olecranon process of the ulna. (C) shows the lateral view sagittal plane cross section of the knee joint. The following are labeled: quadriceps femoris muscle, synovial membrane, femur, suprapatellar bursa, fibrous capsule, patella, synovial membrane, prepatellar bursa, articular cartilage, sub patellar fat, menisci, subcutaneous infrapatellar bursa, tibia, and intrapatellar bursa.

-

Components of a Synovial Joint

- • Therefore, ligaments cross a joint, attaching the bones of a joint together.

- • Evolutionarily, ligaments of a synovial joint formed as thickenings of the outer fibrous layer of the joint capsule.

- • For this reason, the term ligamentous/joint capsule complex is often used to describe the ligaments and the joint capsule of a joint together.

- • Synovial joint ligaments are usually located outside of the joint capsule and are therefore extra-articular; however, occasionally a ligament is located within the joint cavity and is intra-articular. 2

- • Functionally, the purpose of a ligament is to limit motion at a joint. 11

Muscles

- • By definition, a muscle is a soft tissue structure that is specialized to contract. 1

- • A muscle attaches via its tendons to the two bones of a joint. Therefore, a muscle connects the two bones of the joint that it crosses to each other. 1

- • Some muscles cross more than one joint and do not attach to every bone of each joint that they cross. For example, the biceps brachii crosses the shoulder and elbow joints, but it attaches proximally to the scapula, and then skips over the humerus to attach distally onto the radius.

- • Muscles are nearly always extra-articular. Only a couple of examples can be found of a tendon of a muscle being located intra-articularly (i.e., within a joint cavity). The long head of the biceps brachii runs through the shoulder (i.e., glenohumeral) joint; the proximal tendon of the popliteus is located within the knee joint. 12

- • The major function of a muscle is to contract and to generate a force on one or both bones of a joint. This contraction force can move one or both of the bones and create motion at the joint. (The role that muscles play in the musculoskeletal system is covered in much greater depth in Chapters 13 to 15.)

Classification of Synovial Joints

- • Synovial joints can be divided into four categories based on the number of axes of movement that exist at the joint 4 (Box 7-6):

-

- 1. Uniaxial joint: A uniaxial joint allows motion to occur around one axis, within one plane.

- 2. Biaxial joint: A biaxial joint allows motion to occur around two axes, within two planes.

- 3. Triaxial joint: A triaxial joint allows motion to occur around three axes, within three planes (a triaxial joint is also known as a polyaxial joint).

- 4. Nonaxial joint: A nonaxial joint allows motion to occur within a plane, but this motion is a gliding type of motion and does not occur around an axis.

Section 7.10. Uniaxial Synovial Joints

- • A uniaxial joint allows motion around one axis; this motion occurs within one plane.

- • Two types of uniaxial synovial joints exist 6 :

Hinge Joints

- • A hinge joint is a joint in which the surface of one bone is spool-like and the surface of the other bone is concave. The spool-like surface moves within the concave surface of the other bone. 4

- • A hinge joint is similar in structure and function to the hinge of a door hence its name.

- • An example of a hinge joint is the elbow joint 5 (Figure 7-12, A).

- • Another example of a hinge joint is the ankle joint (Figure 7-12, B).

Pivot Joints

- • A pivot joint is a joint in which one surface is shaped like a ring, and the other surface is shaped so that it can rotate within the ring. 3

- • A pivot joint is similar in structure and function to a doorknob.

- • An example of a pivot joint is the atlantoaxial joint between the ring-shaped atlas (C1) and the odontoid process (i.e., dens) of the axis (C2) in the cervical spine 6 (Figure 7-13, A).

- • Another example of a pivot joint is the proximal radioulnar joint of the forearm, in which the radial head rotates within the ring-shaped structure created by the radial notch of the ulna and the annular ligament 6 (Figure 7-13, B).

(A) shows a hand bent at the elbow such that it forms a L-shaped position with the palm facing upwards and a hinge fixed through the elbow joint. (B) shows a leg and a hinge fixed through the major ankle joint.

(A) shows the atlantoaxial joint that has two forces that are acting upon it in opposite directions. (B) shows the proximal radioulnar joint that has a hinge fixed through its joint and the direction of rotation is towards the right.

Section 7.11. Biaxial Synovial Joints

Condyloid Joints

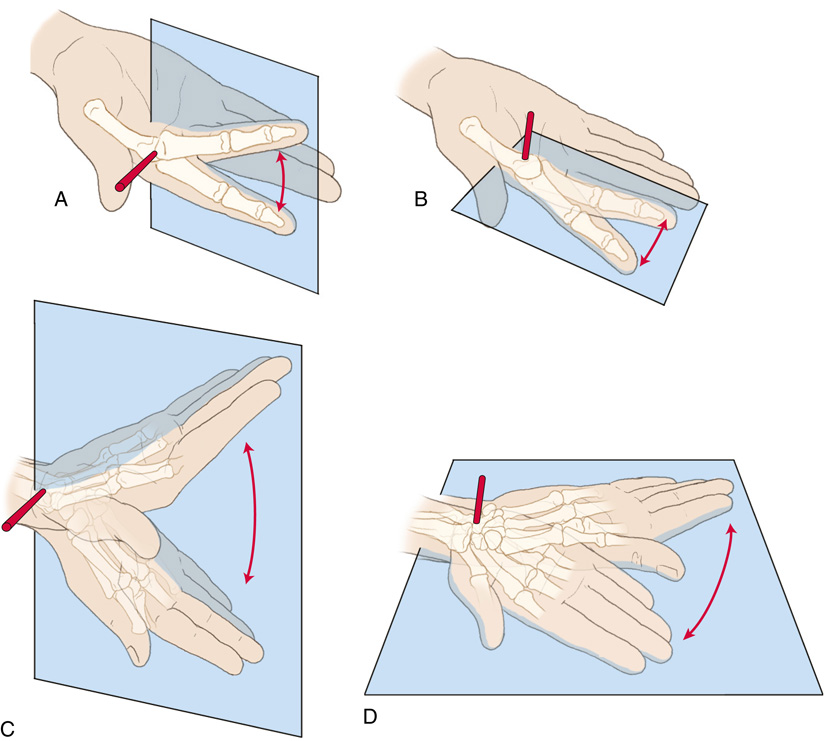

- • In a condyloid joint, one bone is concave and the other bone is convex (i.e., oval) in shape. The convex bone fits into the concave bone. 8

- • An example of a condyloid joint is the metacarpophalangeal (MCP) joint of the hand 6 (Figure 7-14, A and B).

- • Another example of a condyloid joint is the radiocarpal joint of the wrist (Figure 7-14, C and D).

Saddle Joints

- • A saddle joint is a modified condyloid joint. 4

- • Instead of having one convex-shaped bone that fits into a concave-shaped bone, both bones of a saddle joint are shaped such that each bone has a convexity and a concavity to its surface; the convexity of one bone fits into the concavity of the other bone and vice versa. 8

- • Saddle joints are similar in structure and function to a person sitting on a Western saddle on a horse.

- • The classic example of a saddle joint is the carpometacarpal (CMC) joint of the thumb 5 (Figure 7-15, A and B, and Box 7-7).

- • Another example of a saddle joint is the sternoclavicular joint between the manubrium of the sternum and the medial end of the clavicle (Figure 7-15, C and D).

(A) shows the metacarpophalangeal joint wherein the middle finger is lifted upwards and a hinge is fixed through the joint. (B) shows the metacarpophalangeal joint wherein the finger is slightly lowered downward thus forming an angle sideways. (C) shows the radiocarpal joint wherein the palm is stretched upwards and a hinge is fixed through the joint. (D) shows the side to side movement of the palm and the hinge is fixed through its joint.

(A) shows the thumb moved across towards the little fingers. A man on a saddle back of a horse slightly tilting towards his left. (B) shows the thumb diagonal with the index finger. A man over the horseback slightly leaning towards the front from his original sitting position. (C) shows the upper shoulder bone and ribcage wherein the following parts are labeled: clavicle, sternoclavicular joint, and manubrium of the sternum. (D) shows the sternoclavicular joint that has the following parts labeled: clavicle, manubrium of the sternum, and the 1st rib.

Section 7.12. Triaxial Synovial Joints

- • A triaxial joint allows motion around three axes; this motion occurs within three planes. 4

- • Only one major type of triaxial synovial joint exists—the ball-and-socket joint.

Ball-and-Socket Joints

- • In a ball-and-socket joint, one bone has a ball-like convex surface that fits into the concave-shaped socket of the other bone. 3

- • An example of a ball-and-socket joint is the hip joint 6 (Figure 7-16).

- • Another example of a ball-and-socket joint is the shoulder joint 8 (Figure 7-17).

(A) shows the anterior view of the ball and socket joint of the hip. The labels are pelvic bone, acetabulum, and femoral head. (B) shows the rotation of the pelvis bone at the thigh. (C) shows a similar view as the previous one except that a hinge is fixed through the joint. (D) shows depicts the lateral and medial rotation of the thigh at the hip joint that occur in a transverse plane around a vertical axis. The direction of rotation is marked is represented by a circle.

(A) shows the anterior view of the ball and socket joint of the shoulder. The following parts are labeled: scapula, glenoid tossa, and humoral head. (B) shows the flexion and extension of the arm at the shoulder joint and a hinge fixed at the joint. (C) shows of the bending and extending of the arm at the shoulder joint that occur in the frontal plane around a mediolateral axis. (D) shows the lateral and medial rotation of the arm at the shoulder joint and a hinge is fixed through the joint.

Section 7.13. Nonaxial Synovial Joints

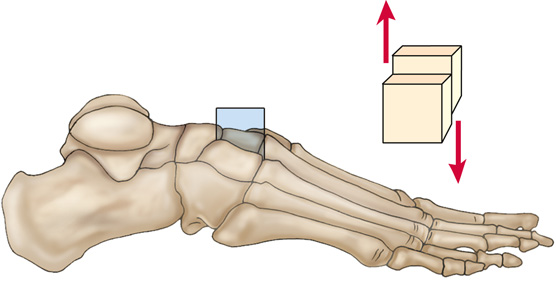

- • A nonaxial joint allows motion within a plane, but this motion does not occur around an axis. 2

- • The motion that occurs at a nonaxial joint is a gliding movement in which the surface of one bone merely translates (i.e., glides) along the surface of the other bone. 4 (See Chapter 6, Sections 6.2 to 6.4 for more information on nonaxial translation motion.)

- • It is important to emphasize that motion at a nonaxial joint may occur within a plane, but it does not occur around an axis hence the name nonaxial joint.

- • The surfaces of the bones of a nonaxial joint are usually flat or slightly curved.

- • Examples of nonaxial joints are the joints found between adjacent tarsal bones 5 (i.e., intertarsal joints) (Figure 7-18).

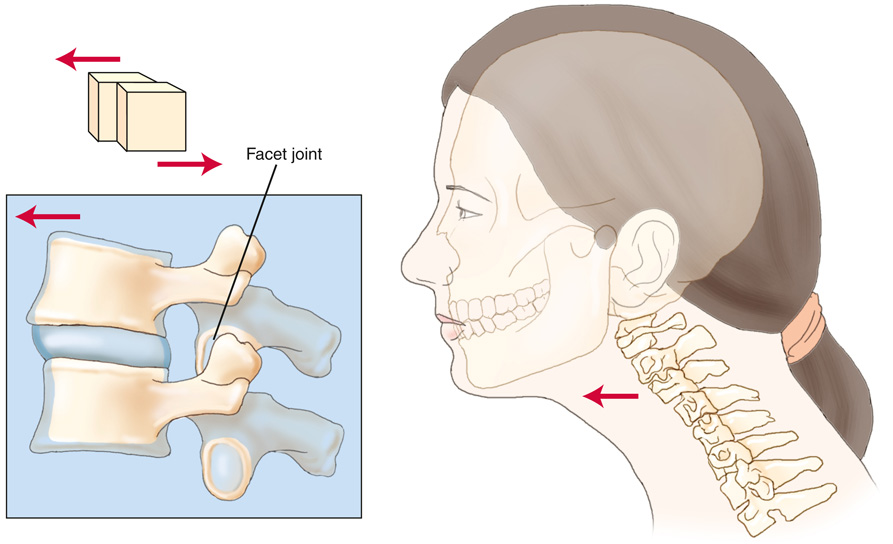

- • Another example of a nonaxial joint is a facet joint of the spine (Figure 7-19).

- • A nonaxial joint is also known as a gliding joint, an irregular joint, or a plane joint. 13

An illustration depicts the joints between the facets in the spine. The surfaces of the facets are flat or slightly curved. One facet moves over another by gliding action. The spine area near the neck in the body of a woman is indicated. The inset shows the facet joint in clear vision.

Section 7.14. Menisci and Articular Discs

- • Most often, the bones of a joint have opposing surfaces that are congruent (i.e., their surfaces match each other). However, sometimes the surfaces of the bones of a joint are not well matched. In these cases the joint will often have an additional intra-articular structure interposed between the two bones.

- • These additional intra-articular structures are made of fibrocartilage and function to help maximize the congruence of the joint by helping to improve the fit of the two bones. 14

- • By improving the congruence of a joint, these structures help to do two things:

-

- • Maintain normal joint movements: Because of the better fit between the two bones of the joint, these structures help to improve the movement of the two bones relative to each other. 1

- • Cushion the joint: These structures help to cushion the joint by absorbing and transmitting forces (e.g., weight-bearing, shock absorption) from the bone of one body part to the bone of the next body part. 1

- • If this fibrocartilaginous structure is ring shaped, it is called an articular disc.

- • If it is crescent shaped, it is called a meniscus (plural: menisci).

- • Although these structures are in contact with the articular surfaces of the joints, they are not attached to the joint surfaces but rather to adjacent soft tissue of the capsule or to bone adjacent to the articular surface. 14

- • Articular discs are found in many joints of the body.

-

- • One example is the temporomandibular joint (TMJ), which has an articular disc located within its joint cavity 1 (Figure 7-20, A).

- • Another example is the sternoclavicular joint, which has an articular disc located within its joint cavity (Figure 7-20, B).•Articular menisci are found between the tibia and the femur in the knee joint 4 (Figure 7-21).

(A) shows the lateral cross-section of the temporomandibular joint. The cut-away diagram has the following parts labeled: temporal bone, articular disc, and mandible. (B) shows the anterior view of the sternoclavicular joint. The following parts are labeled out: clavicle, manubrium of sternum, articular disc, and 1st rib.

(A) shows the posteromedial view of the right knee joint. The cut-away diagram has the following parts labeled from top to bottom: fezur, medial meniscus, lateral meniscus, head of fibula, and tibia. (B) shows the proximal view looking down on the tibia. The following parts are labeled out: lateral meniscus, medial meniscus, and tibial tuberosity.