Evidence-Based Informatics

Juliana J. Brixey and Zach Burningham

Abstract

This chapter links evidence-based practice (EBP) and practice-based evidence (PBE) with informatics by exploring the central, shared construct of knowledge. The discussion offers a foundation for understanding EBP and PBE, as well as their interrelationships. The narrative describes how EBP and PBE are supported and integrated through a variety of current informatics applications. The chapter concludes by exploring opportunities for applying informatics solutions to maximize the advantages offered by the synergistic implementation of EBP and PBE in providing cost-effective, safe, quality healthcare for individuals, families, populations, and communities.

At the completion of this chapter, the reader will be prepared to:

- 1. Give examples of trends in evidence-based quality improvement.

- 2. Describe effective models in structuring evidence-based practice (EBP) initiatives.

- 3. Discuss the role of informatics in EBP.

- 4. Discuss the relationship between EBP and practice-based evidence (PBE).

- 5. Summarize key components of the practice-based evidence (PBE) research designs.

- 6. Discuss the synergistic role of EBP and PBE in developing informatics-based solutions for managing patients’ care needs.

Key Terms

clinical practice guidelines (CPGs), 172

comparative effectiveness research, 183

evidence-based practice (EBP), 166

knowledge transformation, 170

learning health system (LHS), 166

practice-based evidence (PBE), 166

High-quality cost-effective care requires health information systems that present the evidence needed for providers to make best-practice decisions at the point of care and then capture the data by which the effectiveness of those decisions can be measured.

Introduction

Informatics solutions and tools hold promise for enhancing evidence-based clinical decision making and for measuring the effectiveness of those decisions in real-time. The field of informatics and the concepts of evidence-based practice (EBP) and practice-based evidence (PBE) intersect at the crucial junction of knowledge for clinical decisions, with the goal of transforming healthcare to be reliable, safe, and effective.

A foundational paradigm for informatics is the framework of data, information, knowledge, and wisdom (DIKW) discussed in Chapter 2. The DIKW framework indicates that, as data are organized into meaningful groupings, the information within those data can be seen and interpreted. The organization of information and the identification of the relationships between the facts within the information create knowledge. The effective use of knowledge, such as the process of providing personalized care to manage human healthcare needs, is wisdom. The DIKW framework is foundational to developing a learning health system (LHS), emphasizing the importance of real-world data and analytics to continually deliver new knowledge to providers and stakeholders, leading to wiser action and enhanced decision-making.

An LHS is now possible through advancements in computerization and the electronic health record (EHR). These tools provide the technologies to collect, organize, label, and efficiently and effectively deliver evidence-based information and knowledge at the point of decision making where clinicians can apply them. Patient-specific data is captured through documentation in the patient’s EHR as care is delivered, thereby providing a feedback loop for evaluating the effectiveness of patient-care decisions, creating cycles of continuous quality improvement (CQI). These data can be aggregated across patients, demonstrating the effectiveness of evidence-based decisions across groups of patients in various settings.

A challenge to achieving this ideal is the complexity of issues surrounding standardized terminology in healthcare and the lack of a common framework across the field of EBP and PBE. Standardized terminology is requisite for naming, classifying, tagging, locating, and then analyzing evidence to use in practice.

Evidence-Based Practice

Knowledge is the heart of EBP. Knowledge must be transformed to increase its utility at the point of care (POC) within the EBP paradigm (Stevens 2015). EBP’s ultimate goal is improving systems and microsystems within healthcare based on science. Using computerized methods and resources to support the implementation of EBP has the potential for improving healthcare. Delivering evidence to the point of patient care can align care processes with best practices.

Evidence-based Practice Evolution

The evolution of EBP underscores its potential impact on quality of care and health outcomes. To Err Is Human, a well-known Institute of Medicine report, estimated that approximately 100,000 patients were harmed annually by the healthcare system (Institute of Medicine, 2000). The report emphasized the significance of preventable harm and death. Experts in 2014 considered 100,000 deaths as an underestimation suggesting that more recent data indicate the mortality rate of medical errors ranges from 210,000 to 400,000 annually (McCann, 2014; James, 2013; Makary & Daniel, 2016; Anderson & Abrahamson, 2017). There is a debate that the actual number of deaths attributed to medical errors has been overestimated (Jarry, 2021). Nonetheless, healthcare organizations have not irradicated avoidable medical errors.

Crossing the Quality Chasm (Chasm), a 2001 Institute of Medicine report following To Err Is Human, reported that national leaders identified the gap between what is known about best care and what is practiced. Moreover, the Chasm report cited more than 100 surveys of quality of care with scores on the “report card” indicating healthcare performance as poor. Box 11.1 presents findings from these surveys, comparing current care to what was deemed the best care or standards of care. These results indicated that improvement was needed if every patient is to receive consistent, high-quality care. The report identified EBP as a solution to achieve the goal of quality healthcare.

Another set of reports demonstrating this challenge is the National Healthcare Quality Report (NHQR) and the National Healthcare Disparities Report (NHDR) produced by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ). These reports, published annually since 2003, have provided an annual snapshot of the quality of care across the country (Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality [AHRQ], 2015). Beginning in 2014, findings on healthcare quality and healthcare disparities were integrated into a single document titled the National Healthcare Quality and Disparities Report (QDR). This report highlights the importance of examining quality and disparities together to gain a more comprehensive picture of healthcare. “The report demonstrates that the nation has made clear progress in improving the health care delivery system to achieve the three aims of better care, smarter spending, and healthier people, but there is still more work to do, specifically to address disparities in care.” (AHRQ, 2015). For example, patient safety improved, as demonstrated by a 17% reduction in rates of hospital-acquired conditions (HACs) between 2010 and 2013. However, across a broad range of measures, recommended care is delivered only 70% of the time. Similarly, the downward trend for the HACs continued for the years between 2014 and 2017, as evidenced by a 13% reduction (AHRQ, 2020). Failure of care delivery, including clinician-related inefficiencies such as variability in care, has not been resolved, resulting in continued waste and cost (Shrank, Rogstad, & Parekh, 2019).

Solutions to the healthcare quality gap are offered in the Chasm report (Institute of Medicine [IOM], 2001). The IOM expert panel issued recommendations for urgent action to redesign healthcare so that it is safe, timely, effective, efficient, equitable, and patient-centered, often referred to as the STEEEP principles (IOM, 2001). Each of the STEEEP redesign principles is described further in Table 11.1.

Table 11.1

Adapted from Institute of Medicine. (2001). Crossing the quality chasm: A new health system for the 21st century (Committee on Health Care in America & Institute of Medicine) (pp. 39–40). Washington, DC: National Academies Press.

The Chasm report continues to be a major influence, directing national efforts targeted at transforming healthcare. For example, the STEEEP recommendations are now reflected in health profession education programs. The American Association of Colleges of Nursing (AACN) educational competencies include requirements for programs to prepare nurses who contribute to quality improvement (American Association of Colleges of Nursing [AACN], 2021). AACN Essentials, updated in 2021, specify that professional nursing practice be grounded in translation of current evidence into practice and further point to the need for knowledge and skills in information management as being critical in the delivery of quality patient care (AACN, 2021). Likewise, the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) requires medical education in quality improvement (Accreditation Council for Graduate, 2020). The STEEEP principles are also reflected in clinical practice resources, such as the AHRQ Health Care Innovations Exchange, where the STEEEP elements are the selection criteria for inclusion in this unique clearinghouse (AHRQ, 2021).

Quality of Care

Quality of care and EBP are conceptually linked, and form the hub of healthcare improvement. The descriptions and definitions reflect the overlap of these concepts and offer reference points against which to expand their understanding. In particular, the focal point of both is the use of knowledge in practice.

The definition of quality of care includes two essential connections to EBP and knowledge that provide a linkage to informatics. First, quality healthcare services increase the likelihood of reaching the goals of care or expected outcomes. This implies that processes of EBP must assist clinicians in knowing which options in health services are effective. The strongest cause-and-effect knowledge is discovered through formal research. Second, EBP is connected to quality insofar as healthcare is consistent with current knowledge. Using knowledge presumes accessibility to it at the POC. The overlap of EBP and knowledge is further underscored by the definition of the STEEEP principle “effective.” Effectiveness is defined in the STEEEP framework as evidence-based decision making, suggesting, “Patients should receive care based on the best available scientific knowledge” (p. 62) Knowledge is the point of convergence across the areas of EBP, informatics, and improvement. Using informatics approaches can make evidence available and accessible at the POC.

POC testing can occur within the LHS framework. Through informatics, a health system can implement an evidence-based approach to learn what is and what is not working in healthcare quality and safety. An LHS is broadly defined as “any entity that routinely and continuously seeks to generate and learn from data, for purposes of improving individual and population health.” (Guise et al., 2018). It is important to note that an LHS is not designed to replace more a time-intensive rigorous research design but seeks to compliment such efforts. There are tradeoffs to relying solely on a less controlled approach in determining optimal health care delivery practices.

The LHS recognizes the vital role the patient plays in the continual learning process. Providing a patient-centered approach to health outcomes is achieved by using patient data to formulate, evaluate, and update processes. With the advancements in informatics and IT, organizations now seek to develop “rapid” LHSs by creating well-orchestrated pipelines of near-real time data that flows back to the clinician and allows for iterative and continual refinement of the knowledge base (Abernathy et al., 2010). It must be noted that while beneficial, the LHS is not without implementation difficulties (Smoyer et al., 2016). For example, an LHS requires substantial IT investment, including a well-constructed backend data architecture, and advanced analytic capabilities, all of which can be resource-intensive. Both data storage and analytic capabilities are equally necessary. An LHS can begin to provide the environment to initiate precision medicine. For example, if genetic test results are simply stored as scanned image files without further analytic processing, then the data interpretation is still left for busy clinicians to complete. Data capture coupled with advanced analytics is required in rendering these data suitable for clinical use, such as being able to quickly determine a patient’s genetic attributes and appropriate model for treatment (Williams et al., 2018). New infrastructures are recommended for the future, including computable representations, augmented with traditional human-readable representations (e.g., text, graphs, and figures) due to the quantity of evidence and the time to change practice. Computable representations include other types of evidence (e.g., rules and predictive models). Notably, the novel representations can be digitized as knowledge objects (DKOs). The DKOs would be available through digital libraries.

The primary impetus for EBP in healthcare is the selection of the option that improves the patient’s health. Evaluation and use of research evidence support this option. In concert with the use of research evidence is the use of an institutional LHS using patient data (evidence) and analytics to assess a personalized, evidence-based approach, to the current medical issue. Clients present multiple actual or potential health problems requiring management or resolution (e.g., living with asthma, learning disabilities, and obesity management). Clinical actions may not be based on the best available scientific knowledge and, therefore, offer less effective client care (IOM, 2001). The essential role of a healthcare provider is to select and provide interventions providing a positive patient outcome and the most effective strategies for changing the microsystem or system of care. Clinicians choose from and interpret various clinical data and information while facing pressure to decrease the uncertainty, risks to patients, and costs. Knowledge underlies these decisions and plays a primary role in the care provided.

Evidence-based clinical decision making can be described as a prescriptive approach to making choices in diagnostic and intervention care, based on the idea that research-based care improves outcomes most effectively. Research-based care provides evidence about which option is most likely to produce the desired outcome. EBP is seen as a key solution in closing the gap between what is known and practiced.

However, essential questions lie between accepting this as true and the clinician’s and system’s ability to enact it: How do clinicians know which interventions will most likely diminish or resolve the health problem and help the client reach their health goal? What resources are available to apply EBP principles directly in clinical decision making? Answering these questions begins with analyzing the different models of EBP.

Evidence-Based Practice Models

Several EBP models are useful in understanding various aspects of EBP and elucidating connections between informatics and EBP. An overview of models in the field reflects several challenges for developing informatics approaches. The primary challenge is the lack of a common framework that could be used to organize and implement EBP principles.

Effective EBP Models

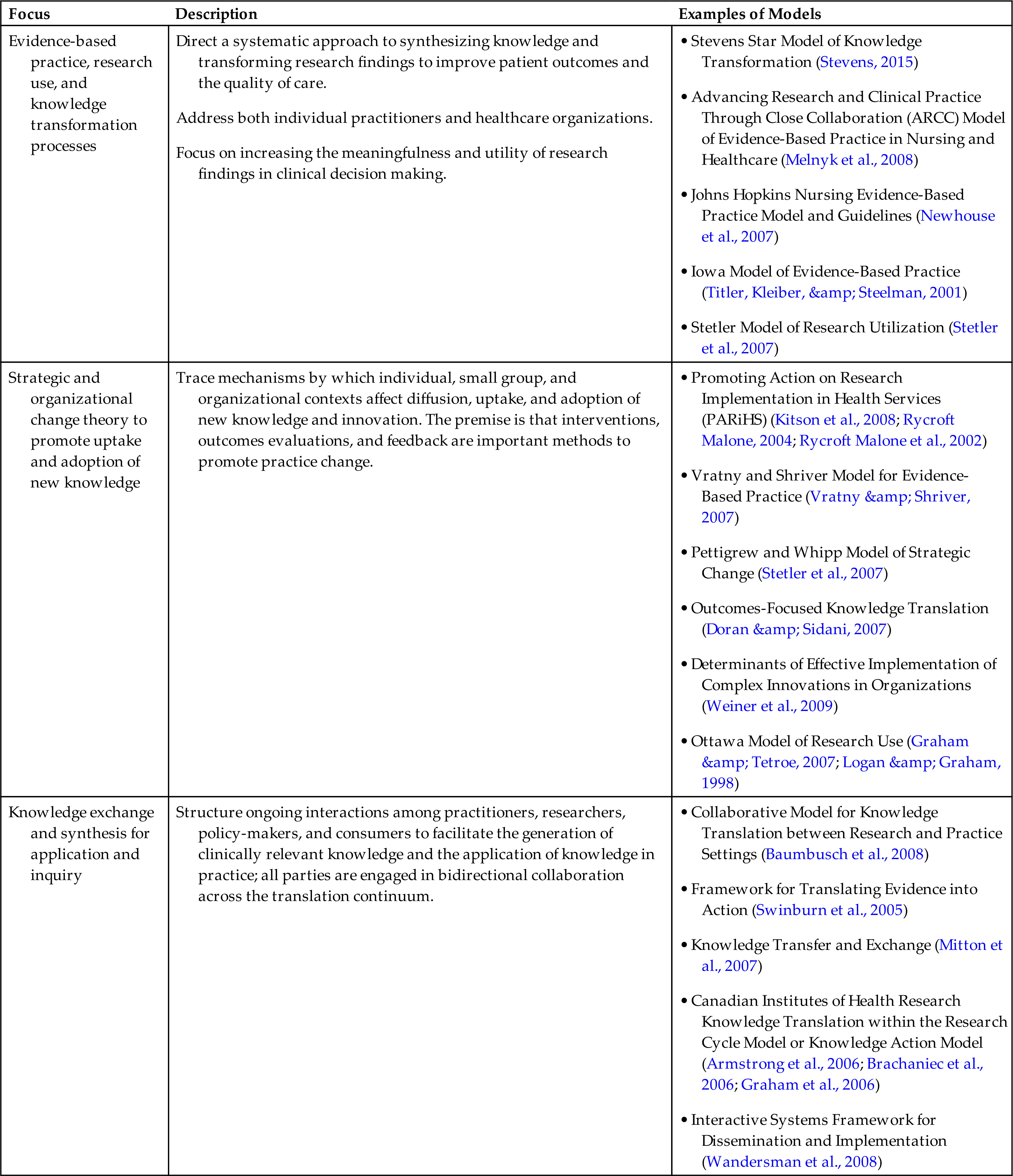

Prominent EBP models can be grouped into one of three categories of models for designing and implementing systematic approaches to strengthen evidence-based clinical decision making (Mitchell et al., 2010). Table 11.2 describes the critical attributes and provides examples in three categories.

Table 11.2

| Focus | Description | Examples of Models |

|---|---|---|

Direct a systematic approach to synthesizing knowledge and transforming research findings to improve patient outcomes and the quality of care. Address both individual practitioners and healthcare organizations. Focus on increasing the meaningfulness and utility of research findings in clinical decision making. | • Stevens Star Model of Knowledge Transformation (Stevens, 2015) • Advancing Research and Clinical Practice Through Close Collaboration (ARCC) Model of Evidence-Based Practice in Nursing and Healthcare (Melnyk et al., 2008) • Johns Hopkins Nursing Evidence-Based Practice Model and Guidelines (Newhouse et al., 2007) • Iowa Model of Evidence-Based Practice (Titler, Kleiber, & Steelman, 2001) • Stetler Model of Research Utilization (Stetler et al., 2007) | |

• Promoting Action on Research Implementation in Health Services (PARiHS) (Kitson et al., 2008; Rycroft Malone, 2004; Rycroft Malone et al., 2002) • Vratny and Shriver Model for Evidence-Based Practice (Vratny & Shriver, 2007) • Pettigrew and Whipp Model of Strategic Change (Stetler et al., 2007) • Outcomes-Focused Knowledge Translation (Doran & Sidani, 2007) • Determinants of Effective Implementation of Complex Innovations in Organizations (Weiner et al., 2009) • Ottawa Model of Research Use (Graham & Tetroe, 2007; Logan & Graham, 1998) | ||

• Collaborative Model for Knowledge Translation between Research and Practice Settings (Baumbusch et al., 2008) • Framework for Translating Evidence into Action (Swinburn et al., 2005) • Knowledge Transfer and Exchange (Mitton et al., 2007) • Canadian Institutes of Health Research Knowledge Translation within the Research Cycle Model or Knowledge Action Model (Armstrong et al., 2006; Brachaniec et al., 2006; Graham et al., 2006) • Interactive Systems Framework for Dissemination and Implementation (Wandersman et al., 2008) |

From Mitchell, S. A., Fisher, C. A., Hastings, C. E., Silverman, L. B., & Wallen, G. R. (2010). A thematic analysis of theoretical models for translational science in nursing: Mapping the field. Nursing outlook, 58(6), 287–300. Used with permission.

The first category includes models that focus on EBP, research use, and knowledge transformation principles. These models emphasize a systematic approach to synthesizing knowledge. The models specify a series of processes designed to:

Identify a question, topic, or problem in healthcare.

Some models in this category emphasize the process where research findings can be transformed into a more useful form, such as a clinical practice guideline (CPG) or standard of care, that can be used to guide clinical decision making in practice. Other models reflect a PBE approach by addressing the outcomes' evaluation to determine whether the EBP change has produced the expected clinical outcomes or to compare actual practice and ideal practice (thereby identifying unacceptable practice variation).

The second category includes models that offer an understanding of the mechanisms by which individual, small group, and organizational contexts affect the diffusion, uptake, and adoption of new knowledge, as well as innovation, which is essential to the design of EBP initiatives. These models propose that specific interventions accelerate the adoption of practices based on best evidence. Examples of such interventions include:

Thus, within these models, feedback regarding both patient and practitioner outcomes is seen as a change strategy.

A third category of models and frameworks postulates that formalized, bidirectional, and ongoing interactions among practitioners, researchers, policymakers, and consumers accelerate the application of new discoveries in clinical care. This ongoing interaction increases the likelihood that researchers will focus on problems of importance to clinicians. Such models simultaneously address the generation of new knowledge (discovery) and uptake. This collaboration supports the exchange of expertise and knowledge to strengthen decision making and action for all involved parties (Mitchell et al., 2010).

Each EBP model described previously has perspectives that may prove valuable in designing and advancing informatics approaches to EBP. The following section examines the application of one of these models, the Stevens ACE Star Model of Knowledge Transformation, (Stevens, 2015) which will be used to demonstrate how an EBP model can:

- • Guide the transition from the discovery of new information and knowledge to the provision of care that is based on evidence, and

- • Identify how computerization and informatics principles can be used to make this transition realistically possible in a world in which information and knowledge are growing at an explosive rate.

Stevens Star Model of Knowledge Transformation

The Star Model provides a framework for converting research knowledge into a form that has utility in the clinical decision-making process. The model articulates a necessary process for reducing the volume and complexity of research knowledge, evolving one form of knowledge to the next, and incorporating a broad range of sources of knowledge throughout the EBP process.

The model addresses two major hurdles in employing EBP:

In both instances, informatics-based solutions have been created. The Star Model explains the key concept of knowledge transformation. Knowledge transformation is defined as the conversion of research findings from the discovery of primary research results, through a series of stages and forms, to increase the relevance, accessibility, and utility of evidence at the POC to improve healthcare and health outcomes by way of evidence-based care (Stevens, 2015).

When considering the volume of knowledge, experts point out, “no unaided human being can read, recall, and act effectively on the volume of clinically relevant scientific literature.”11,p.25 It is estimated that more than 10,000 new research articles are published annually in medicine. Collectively, approximately 12.8 million medical and health studies were published between 1980 and 2012 (Bornmann & Mutz, 2015).

Even the most enthusiastic clinician or researcher would find it challenging to stay abreast of this volume of literature. When considering the form of knowledge as a barrier, it is clear that most research reports are not directly useful in a clinical setting but must be converted to a form applicable at the POC. Research results, often presented as statistical results, exist in a larger body of knowledge. The complexity and lack of congruence across all studies on a topic create a barrier when using this as a basis for clinical decision making. The Stevens Star Model addresses the transformation necessary for converting research results from single-study findings to guidelines that can be applied and measured for effect. Discussion of this model is expanded in the next section, with specific electronic resources for each form of knowledge identified and described.

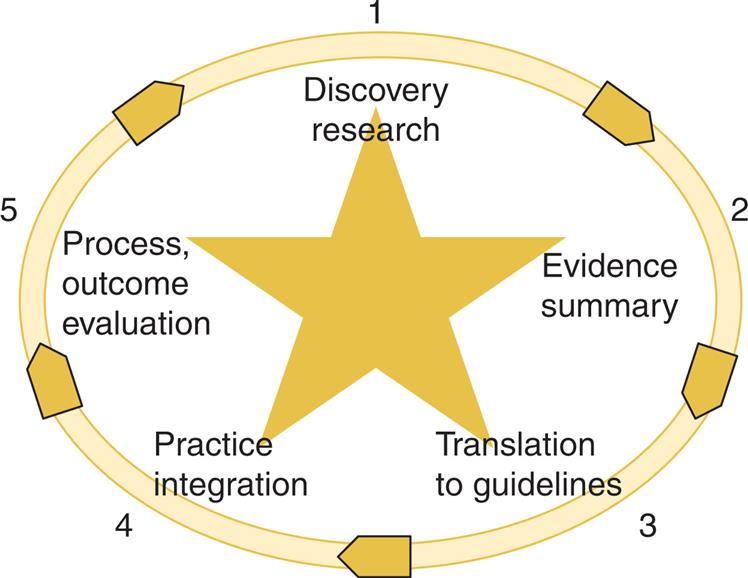

In the Star Model, individual studies move through four cycles, ending in practice outcomes and patient outcomes. The knowledge transformation process occurs at five points, conceptualized as a five-point star, as shown in Fig. 11.1. These five points are discovery research, evidence summary, translation to guidelines, practice integration, and evaluation of process and outcome (Stevens, 2015). A description of each point is provided below, along with identification and descriptions of computerized resources and examples.

Point 1: Discovery Research

Primary research on Point 1 represents the knowledge produced through primary discovery. In this stage, knowledge is in the form of results from single research studies. Over the past three decades, health-related research has produced thousands of research studies on a wide variety of health-related issues. However, the clinical utility of this form of knowledge is low. The cluster of primary research studies on any given topic may include strong and weak study designs, small and large samples, and conflicting or converging results, leaving the clinician to wonder which study best reflects cause and effect in selecting effective interventions. Point 1 knowledge is less useful in clinical decision making because many research studies may exist on a given topic, with the overall collection being unwieldy. The group of studies does not converge on a consensus of the intervention that is most likely to produce the desired outcome. Instead, one study may show that the intervention was successful, while another shows no difference between control and experimental conditions.

Initially, health sciences researchers focused on directly applying the primary research study results in patient care, detailing ways to move a single study into practice. However, since there may be multiple studies on a given topic, this strategy is no longer appropriate for most interventions. Table 11.3 illustrates part of the challenge in moving research into practice with this approach. In this example, the clinician seeks to locate current evidence about falls prevention in the elderly. A PubMed literature search on the topic “falls prevention” between 1977 and 2021 returned more than 21,614 articles to consider. Even when the search strategy was limited to “research,” more than 12,143 articles remained. The volume of literature is far too great to have clinical utility.

Table 11.3

Point 2: Evidence Summary

Table 11.3 illustrates the advantage of knowledge management through knowledge transformation stages, specifically, evidence summaries. Evidence summaries include evidence synthesis, systematic reviews (SRs), integrative reviews, and reviews of the literature, with SRs being the most rigorous approach to evidence summary. Before evidence summaries were developed, the clinician was left to deal with the many articles located via a bibliographic database search: in this case, thousands of articles. However, if the research knowledge has been transformed through evidence synthesis, the resulting SR will contain this comprehensive knowledge base in a single article. The EBP solution to the complexity and volume of literature seen in Point 1 is the Point 2 evidence summary. In this second stage of knowledge transformation, a team locates all primary research on a given clinical topic and summarizes it into a single document about the state of knowledge on the topic. This summary step is the main knowledge transformation that distinguishes EBP from simple research application and research use in clinical practice. The importance of this transformation cannot be overstated: SRs are described as the central link between research and clinical decision making (IOM, 2008). Key advantages of SRs are summarized in Box 11.2. Returning to Table 11.3 and our example on falls, once the literature search is transformed into “systematic reviews,” the volume of located sources is decreased to 250 citations. Once a narrowed clinical topic is applied, the search yields six SR on falls prevention in the elderly, thereby transforming over 14,000 pieces of knowledge into a manageable resource.

An SR combines results from a body of original research studies into a clinically meaningful whole to produce new knowledge through synthesis to use the statistical procedure meta-analysis. The statistical procedure meta-analysis can combine findings across multiple studies. Evidence summaries communicate the latest scientific findings in an accessible form that can be readily applied in making clinical decisions; that is, evidence summaries form the basis upon which to build EBP. When developing an evidence summary, nonsignificant findings can be as important to practice as positive results. However, nonsignificant findings tend not to be published and so are underrepresented in the literature.

Conducting sound evidence summaries requires scientific skill and extensive resources: often more than a year’s worth of scientific work. Therefore, evidence summaries are often conducted by scientific and clinical teams that are specifically prepared in the methodology. The dominant method for SRs is published in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins & Thomas, 2021). Narrowing down the publications is facilitated by computerized methods using Covidence (available at shorturl.at/gltw8) to screen publications and by using a reference manager such as EndNote (Clarivate, 2021).

The state of the science in informatics points to the fact that the field is developing; as such, research conducted on key aspects remains in the descriptive and correlational phases of scientific development—causal studies that test interventions are limited. The limitation can preclude the use of the SR method to summarize effect sizes across multiple studies. In fact, Weir et al. contend that researchers rushed to perform experimental studies for computerized provider order entry (CPOE) before the phenomenon was understood (Weir et al., 2012; Weir et al., 2009). With newer fields such as informatics, qualitative and descriptive studies are needed first. Then causal and comparative research and subsequent integrative reviews and SRs can be conducted to summarize the science of health informatics.

Evidence resources and examples

Major computerized resources for locating SRs include the Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, the AHRQ, as well as the general professional literature. The Cochrane’s primary strategy is the production and dissemination of SRs of healthcare interventions. This group established the “systematic review” as a literature review, conducted using rigorous approaches that synthesize all high-quality research evidence to reflect current knowledge about a specific question. The Cochrane Collaboration specifies the scientific methods, and its design is considered the gold standard for evidence summaries. As of October 2021, the Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews included 8715 SRs (The Cochrane Collaboration, 2016). Using an example of fall prevention, the most accessed Cochrane Review in 2014 is entitled “Interventions for Preventing Falls in Older People Living in the Community.” The findings from this SR are summarized in Box 11.3. The evidence summary offers powerful knowledge about what interventions are likely to be most successful. Note that in this example, 62 trials (Point 1 studies) were located, screened for relevance and quality, and meta-analysis was used to consolidate results into a single set of conclusions. However, the recommendations for practice from the SR are not yet action-oriented. It is necessary to translate a conclusion into an actionable recommendation by moving knowledge to Point 3 on the Star model for this to happen.

Point 3: Translation to Guidelines

In the third stage of EBP, translation, experts are called on to consider the evidence summary, fill in gaps with consensus expert opinion, and merge research knowledge with expertise to produce clinical practice guidelines (CPGs). This process translates the research evidence into clinical recommendations. The IOM defines clinical guidelines as “systematically developed statements to assist practitioner and patient decisions about appropriate healthcare for specific clinical circumstances” (IOM, 2011)

CPGs have evolved during the past 20 years from recommendations based mainly on expert judgment to recommendations grounded primarily in evidence. Expert consensus is used in guideline development when research-based evidence is lacking (Clancy & Cronin, 2005). CPGs are commonly produced and sponsored by a clinical specialty organization. Such guidelines are present throughout all organized healthcare as clinical pathways, nursing care standards, and unit policies. An exemplar of the development of CPGs in nursing is Putting Evidence into Practice in Oncology (Oncology Nursing Society [ONS], 2015). This program engages scientists and expert clinicians in examining evidence, conducting evidence summaries, generating practice recommendations, and developing tools to implement the guidelines. These online guidelines are accessible to clinicians and are also published in nursing literature (Mitchell et al., 2009).

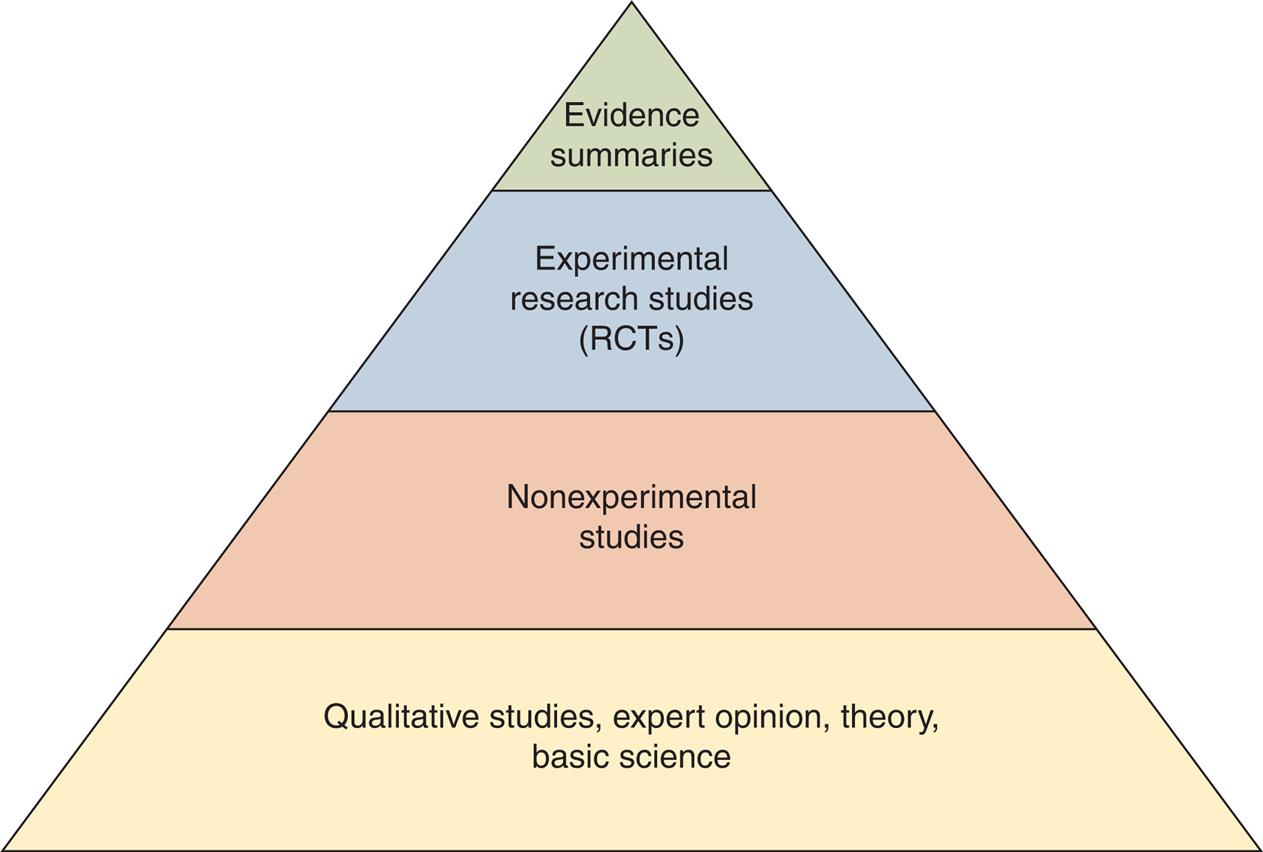

Criteria essential for well-developed CPGs are (1) the evidence is explicitly identified and (2) the evidence and recommendation are rated. Several taxonomies have been developed to assist in rating evidence. One such taxonomy was developed by the Center for Evidence Based Medicine in the United Kingdom. This rating system identifies SRs as the uppermost strength of evidence (Center for Evidence-Based Medicine [CEBM, 2021).

The consensus of expert opinion, rated the weakest strength of all levels of evidence, is also included and counted as evidence. However, if no other evidence exists, this may be used to support clinical decision making. Well-developed CPGs and care standards share several characteristics:

Fig. 11.2 illustrates a strength-of-evidence rating hierarchy (Stevens et al., 2009). The higher the evidence is placed on the pyramid, the more confident the clinician can be that the intervention will cause the targeted health effect.

Some EBP approaches emphasize the usefulness of CPGs in bridging the gap between primary research findings and clinical decision making (IOM, 2008). CPGs are systematically developed statements to assist practitioners and patients in decision-making about appropriate healthcare for specific clinical circumstances (IOM, 2011). CPGs are seen as tools to help move scientific evidence to the bedside. To increase the likelihood that the recommended action will positively impact the clinical outcome, it is imperative that guidelines are based on best available evidence, systematically located, appraised, and synthesized (i.e., evidence based).

Guideline resources and examples

Today, the AHRQ provides the National Guideline Clearinghouse, a searchable database of more than 2500 CPGs entered by numerous sources. Although this knowledge management database can be easily used to locate a wide variety of CPGs, the user must examine the information presented with the CPG to determine that the CPG is current, was developed systematically, and is based on best evidence.

Other guidelines can be located on the AHRQ’s website, U.S. Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) segment (US Preventive Services Task Force [USPSTF], 2021). These recommendations focus on screening tests, counseling, immunizations, and chemoprophylaxis and are based on evidence summary work performed by the AHRQ.

Critical appraisal of the various forms of knowledge is essential. However, for clinical decision making, appraisal of guidelines is crucial for effective clinical care. Several standards for critical appraisal of CPGs are available and can be used to examine CPGs as clinical agencies consider adoption into practice. An excellent example of a systematic approach is the instrument used to assess practice guidelines developed by the Appraisal of Guidelines for Research and Evaluation (AGREE) enterprise (Appraisal of Guidelines, 2010). The 23-item AGREE II instrument developed by this international collaboration is reliable and valid. It outlines primary facets of the CPG to be appraised: scope and purpose, stakeholder involvement, rigor of development, clarity and presentation, application, and editorial independence. Even though the instrument is not easily used by the individual clinician, it is helpful to groups and organizations charged with the adoption of specific CPGs. Box 11.4 identifies key elements to be examined when appraising a CPG.

Recommendations flowing from evidence are rated in terms of strength. The USPSTF uses a schema for rating its evidence-based recommendations (USPSTF, 2021). It grades the strength of recommendations according to one of five classifications (A, B, C, D, and I). The recommendation grade reflects the strength of evidence and magnitude of net benefit (benefits minus harms). Table 11.4 defines each grade and indicates the suggestion for practice.

Table 11.4

USPSTF, U.S. Preventive Services Task Force.

US Preventive Services Task Force. Grade definitions. http://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/Page/Name/grade-definitions; October 2014. Reprinted with permission of the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality.

Professional groups within the agency can move forward with confidence that all research evidence has been systematically gathered and amassed into a powerful conclusion of what will work. The evidence summary is vetted through clinical experts, and interpretations are made for direct clinical application. In instances where there is a gap in the evidence summary, the experts consider the evidence of lower rating, and finally add their expertise into the fully developed CPG. Box 11.5 presents an example of Point 3 in the form of a CPG for preventing falls in the elderly. Note that both the evidence and the recommendation are rated.

Many available rating scales convey the strength of the recommendation. Coupled with the strength of evidence, the clinician can use “Level 1” evidence and “Grade A” recommendations to support clinical decisions. The USPSTF adopted a system linking strength of evidence with the strength of recommendation as follows:

- • “A” (strongly recommends)

- • “B” (recommends)

- • “C” (no recommendation for or against)

- • “D” (recommends against)

- • “I” (insufficient evidence to recommend for or against) (Harris et al., 2001).

Box 11.6 presents three examples of USPSTF recommendations, along with the grade of each recommendation.

Translating guidelines into practice is a labor-intensive process involving a significant cognitive load. In the busy world of healthcare, clinicians cannot routinely take time to search out CPGs and then translate their application to individual patients. However, using CPGs to design clinical decision support (CDS) systems in EHRs can make it possible for busy clinicians to access evidence-based guidelines that have been individualized to the patient’s needs and status at the POC.

Point 4: Practice Integration

Once guidelines are produced, the recommended actions are clear. Next, the challenge is to integrate the clinical action into practice and thinking. This integration is accomplished through change at individual clinician, organizational, and policy levels. Integration inevitably involves change and integration of evidence into a myriad of health IT tools such as CDS, Infobuttons, order sets in EHRs, and evaluation of compliance using data warehouses or other big data sources. It is essential that, as advances and best practices emerge, all members of the healthcare team are actively involved in making quality improvement, and health IT changes. Healthcare providers are called on to be leaders and followers in contributing to such improvement at the individual level of care, as well as at the system level of care, together with other disciplines (IOM, 2010).

Patient preference must be considered at the point of integration, with patient and family circumstances guiding individualized EBP. Integration may not be straightforward because the underlying evidence and science of healthcare is incomplete. In addition, computerized tools may not be available to assist in the process. As EHRs increasingly include social and behavioral determinants of health and as personal health records expand, health IT should integrate patient preferences in a more electronic and systematic manner. The USPSTF’s highly developed, well-grounded recommendations, presented in Box 11.6, indicate that clinical judgment must be used, and that individualization to patient circumstances and preferences occurs in moving the evidence-based recommendations into practice. At this point in the transformation of knowledge, the whole of the EBP definition becomes clear: EBP is the integration of best research knowledge, clinical expertise, and patient preference to produce the best-practice decisions.

Practice innovation resources and examples

The AHRQ Health Care Innovations Exchange provides a venue for sharing “what works at our place” along with the evidence of how the innovation was tested (AHRQ, 2021). The Health Care Innovations Exchange was created to speed the implementation of new and better ways of delivering healthcare. This online collection of more than 700 innovation profiles supports the AHRQ’s mission to improve healthcare quality and reduce disparities. The Health Care Innovations Exchange offers frontline health professionals a variety of opportunities to share, learn about, and hasten the adoption of tested innovations. It also contains more than 1500 quality tools suitable for a range of healthcare settings and populations. Innovation profiles and quality tools are continuously entered into the Exchange. Box 11.7 presents an example of an innovation profile.

Increasingly, agencies are extending the standard of excellence in local policies and procedures by moving toward EBP guidelines. Health IT approaches to integrate EBP guidelines into care hold promise of placing such best practices into point-of-care decision making. For example, as clinical summaries and evidence-based order sets can be available in EHRs, credible practice guidelines can be linked and available via CDS applications.

Point 5: Evaluation

The fifth stage in knowledge transformation is evaluation. Practice changes are followed by evaluation of the impact on a wide variety of outcomes, including

Evaluation of specific outcomes is at a high level of public interest (AHRQ, 2015; IOM, 2001). As a result, quality indicators are being established for healthcare improvement and public reporting. Additional information on how EHRs and computerization can be used to provide evaluation data is discussed under PBE later in this chapter. Chapter 12 provides information about integrating EBP into CDS applications.

Evaluation resources and examples

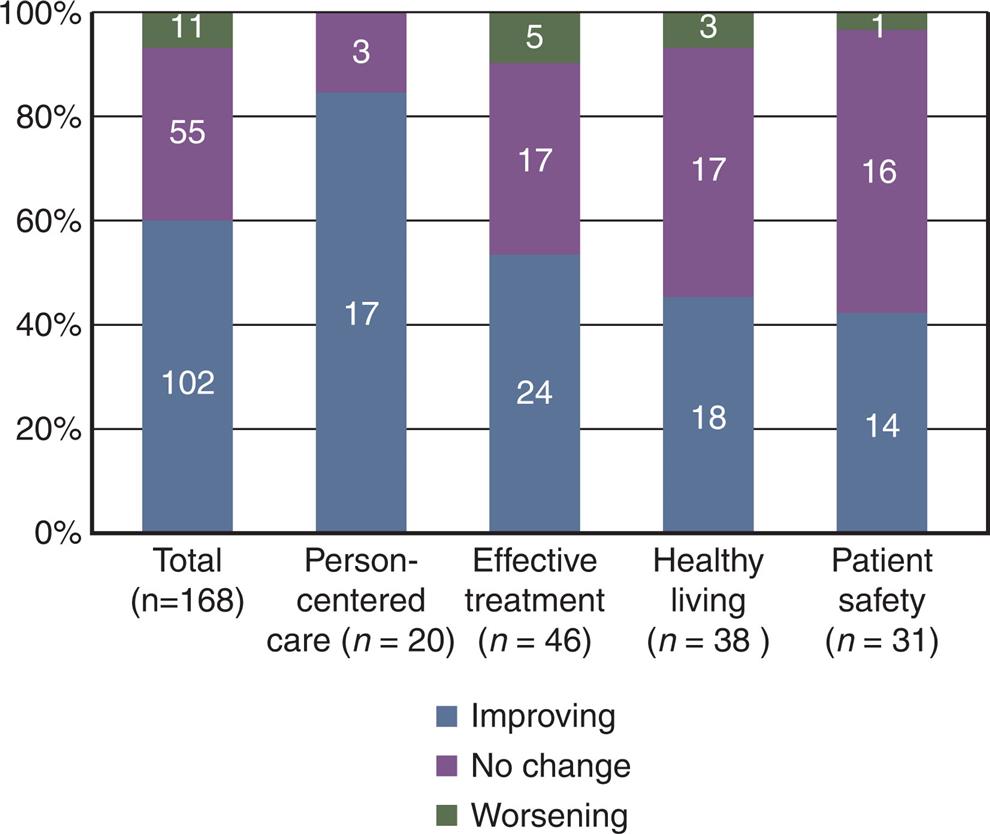

AHRQ, through its National Healthcare QDR, established significant quality indicators (AHRQ, 2015). AHRQ reports provide a comprehensive overview of the quality of healthcare received by the U.S. population, as well as disparities in care experienced by different racial, ethnic, and socioeconomic groups. The reports are based on more than 250 measures of quality and disparities covering a broad array of healthcare services and settings. Key selection criteria include measures that are the most important and scientifically supported. The QDR, using these measures, present in summary statements and charts, form a snapshot of how our healthcare system is performing and the extent to which healthcare quality and disparities have improved or worsened over time.

Fig. 11.3 is a summary chart showing trends across the NQS priorities from the QDR.

Another influential entity establishing quality measures is the National Quality Forum (NQF). This nonprofit organization brings together a variety of healthcare stakeholders, including consumer organizations, public and private purchasers, physicians, nurses, informaticians, hospitals, accrediting and certifying bodies, supporting industries, and healthcare research and quality improvement organizations. The NQF’s mission includes consensus building on priorities for performance improvement, endorsing national consensus standards for measuring and reporting on performance, and education and outreach (National Quality Forum [NQF], 2016). An example of an NQF-endorsed measure for patient safety is presented in Box 11.8.

An important collection of quality measures is assembled in the National Quality Measures Clearinghouse (NQMC), an initiative of the AHRQ (AHRQ, 2021). The NQMC is a database and website for information on evidence-based healthcare quality measures and measure sets. Its purpose is to promote widespread access to quality measures by the healthcare community and other interested individuals. The key targets are practitioners, healthcare providers, health plans, integrated delivery systems, purchasers, and others. The aim is to provide an accessible mechanism for obtaining detailed information on quality measures and to further their dissemination, implementation, and use to inform healthcare decisions. Box 11.9 presents a measure from the NQMC. Computerized tools for analyzing the big data in these national databases and teasing out the factors influencing healthcare outcomes will provide a basis for evidence in the search for other levels of EBP.

Informatics and Evidence-Based Practice

Informatics and IT hold great promise for achieving full integration of EBP into all care, for every patient, every time. The EBP frameworks provide a foundation upon which informatics solutions can be constructed to move evidence into practice. As seen in the examples addressing each point in the Stevens ACE Star Model, knowledge can be sorted and organized into various forms. The national efforts cited here resulted in the availability of several significant web-based information resources to support each point on the Star Model. New and innovative knowledge management tools are still being developed.

Informatics can significantly add to the support of EBP, patient-centered care, and transitions of care across settings. Such technology can greatly assist in the exchange of health information for continuity and quality of care. Furthermore, with recent advancements in the EHR, health care organizations investing in IT, and the introduction of the LHS model, informatics will help facilitate the movement of evidence into practice at an increased pace and will result in the personalization of EBPs based on the unique characteristics of the patient.

The success of improvement through best (evidence-based) practice could be boosted with a greater understanding of the context in which such changes are being made. Once the knowledge is transformed into recommendations (best practices), integrating EBP into practice requires change at levels that include the patient and family, individual provider, microsystem, and macrosystem. The good intentions of an individual provider to use practice guidelines in decision making can be either supported or thwarted by the clinical information systems at the POC.

Successful Evidence-Based Practice Models

Successful models for integrating EBP into practice are emerging. For example, the national team performance training, Team Strategies and Tools to Enhance Performance and Patient Safety (Team STEPPS), has been promoted across military healthcare since 1995, with a “civilian” rollout initiated in 2006 (Team STEPPS, 2015). The program is built on a solid evidence base from human factors engineering and solves urgent problems arising from team-based care. The program demonstrated improvements in communication and teamwork skills among healthcare professionals leading to improvements in patient care.

The role of health IT in quality measurement was described in an AHRQ report (Anderson et al., 2012). Past quality processes were conducted via manual chart entry, manual chart abstraction, and analysis of administrative claims data. Advances are seen in locations with existing health IT. The ability to pull meaningful data from the POC is increasingly computerized as information systems are created and expanded. A potential for health IT is to evolve existing measures into electronic measures and computerized data collection (Anderson et al., 2012).

The long-term goal for improving health IT–enabled quality measurement is to achieve a robust information infrastructure that supports national quality measurement and reporting strategies. Key goals include interoperability that ensures that EHRs can share information for care coordination, patient-centered care, and cost savings. Such interoperability relies on harmonizing standards. Information exchange, integrating interoperability standards into vendor products, and data linkage are critical for advancement (Anderson et al. 2012).

Many challenges must be overcome to achieve the next generation of health IT–enabled quality measurement. First, consensus among quality stakeholders is required to move forward on the purpose of measurement, achieving patient-centricity in a fragmented health delivery system, alignment of incentives; ownership and funding; increased information exchange; and ensuring privacy, security, and confidentiality. Second, measurement challenges to be overcome include measures valuable to consumers, measures to assess value, measures for specialty uses, and accounting for variations in risk in measurement. Third, technology challenges to be overcome include expansion of eMeasures; advancement in measure capture technologies; advancement in patient-focused technologies, health information exchange, interoperability, and standards; internet connectivity; and aggregation and analysis. Notably, the report concludes with a call for stakeholder input to inform pathways to achieving the next generation of quality improvement, an important opportunity in which healthcare providers can engage (Anderson et al. 2012).

The research agenda for health informatics research focuses on issues related to identifying challenges, priorities, and those actions related to increasing the use of the EHR for research, (Zayas-Cabán et al., 2020) population health (Kharrazi et al., 2017) and supporting patient and family empowerment in care after hospitalization (Collins et al., 2018). The new research results in the need for research that tests patient centered and population and infrastructure foci in real-world settings. When the conditions for standardization and interoperability of EHRs are satisfied, patient-specific data can be connected across healthcare settings. Once this occurs, knowledge discovery about coordination and care processes can be expanded using data generated routinely from care settings using PBE principles. By organizing the informatics approach of DIKW into the EBP knowledge transformation and application in real-world settings, the field of quality improvement and EBP translation into practice can be advanced.

As recent as 2020 the ONC (Caban et al., 2020) released two goals and nine priorities as health IT research priorities. The goals included

The 2020 federal health IT principles reflect the ONC continued commitment to translating evidence into practice (Office of the National Coordinator, 2020). Accordingly, EBP and guidelines are necessary for the value-based care model.

Relationship of EBP and PBE

The goal of EBP is to achieve safe, cost-effective quality outcomes by using research-based evidence to direct patient-care decisions. However, to be fully effective, EBP requires the feedback loop provided by practice to determine if the goals of EBP have been achieved in the real world of healthcare delivery. Furthermore, evidence should drive practice, and the data from the practice environment is the ultimate test of the evidence used. Models of EBP and PBE often overlap, especially within the context of an LHS. Leaders need to foster a shared learning culture where evidence drives practice, and the real world of the practice setting provides the ultimate evidence for improving healthcare. With the increasing interoperability of health IT, a shared learning culture extends beyond the local department or institution with the opportunity to create generalizable knowledge to improve care worldwide. Typical PBE questions are:

- • Are treatments used in daily practice associated with intended outcomes?

- • Can we predict adverse events in time to prevent or lessen them?

- • What treatments work best for which patients?

- • With limited financial resources, what are the best interventions to use for specific types of patients?

- • What types of individuals are at risk for certain conditions?

Answers to these questions can help clinicians, patients, researchers, healthcare administrators, and policy-makers learn from and improve real-world, everyday clinical practice. An important emerging approach to knowledge building, including knowledge about the effectiveness of EBP guidelines, can be obtained from clinical data through the application of PBE research design techniques.

Electronic Health Records and Practice-Based Evidence Knowledge Discovery

Increased adoption of EHRs and other health information systems has resulted in vast amounts of structured and textual data. Data may be a partial or a complete copy of all data collected in the course of care provided. Moreover, data can be stored on servers in a data warehouse (a large data repository integrating data across clinical, administrative, and other systems). The data can include billing information, physician and nursing notes, laboratory results, radiology images, and other diverse data types. In some settings, data describing individual patients and their characteristics, health issues, treatments, and outcomes have accumulated for years, forming longitudinal records. The clinical record can also be linked to repositories of genetic or familial data (Duvall et al., 2012; Slattery & Kerber, 1993; Hu et al., 2011). These data constitute an underused resource for scientific research in biomedicine and nursing.

The potential of using these data stores to advance scientific knowledge and patient care is widely acknowledged. However, clinical concepts are typically represented in the EHR to support healthcare delivery but not necessarily research. For example, pain might be qualitatively described in a patient’s note and EHR as “mild” or “better.” The description may meet the immediate need for documentation and care. However, the description does not allow the researcher to measure differences in pain over time and across patients, as would measurement using a pain scale. Clinical concepts may not be adequately measured or represented in a way that enables scientific analysis. Data quality affects the feasibility of secondary analysis.

Knowledge Building Using Health Information Technology

PBE studies are observational studies that attempt to mitigate the weaknesses traditionally associated with observational designs. The mitigation is accomplished by exhaustive attention to determining patient characteristics that may confound conclusions about the effectiveness of an intervention. For example, observational studies might indicate that aerobic exercise is superior to nonaerobic exercise in preventing falls. Nevertheless, if the prescribers tend to order nonaerobic exercise for those who are more debilitated, the severity of illness is a confounder and should be controlled in the analysis.

PBE studies use large samples and diverse sources of patients to improve sample representativeness, power, and external validity. In general, there are 800 or more subjects. PBE uses approaches similar to community-based participatory research by including frontline clinicians and patients in the design, execution, and analysis of studies, as well as their data elements, to improve relevance to real-world practice. Finally, PBE uses detailed standardized structured documentation of interventions, which is ideally incorporated into the standard electronic documentation.

This method requires training and quality-control checks for the reliability of the measures of the actual process of care. Statistical analysis involves correlations among patient characteristics, intervention process steps, and outcomes. PBE can uncover best practices and combinations of treatments for specific types of patients while achieving many of the presumed advantages of randomized controlled trials (RCTs), especially the presumed advantage that RCTs control for patient differences through randomization. Frontline clinicians treating the study patients lead the study design and analyses of the data prospectively based on clinical experience. The characteristics of PBE are summarized in Table 11.5.

Table 11.5

Practice-Based Evidence

Practice-Based Evidence Features and Challenges

PBE is an innovative prospective research design that uses data gathered from current practice to identify what care processes work in the real world. EBP is about using evidence to guide practice. PBE is about obtaining evidence from practice.

PBE studies mitigate the weaknesses usually associated with traditional observational designs in four main ways:

- • Exhaustive attention to patient characteristics to address confounds or alternative explanations of treatment effectiveness.

- • Use of large samples and diverse sources of patients to improve sample representativeness, power, and external validity.

- • Use of detailed standardized structured documentation of interventions with training and quality-control checks for the reliability of the measures of the actual process of care.

- • Inclusion of frontline clinicians and patients in the design, execution, and analysis of studies and their data elements to improve ecological validity.

PBE studies require comprehensive data acquisition. By using bivariate and multivariate associations among patient characteristics, process steps, and outcomes can be identified. Concurrently, PBE study designs are structured to minimize the potential for false associations between treatments and outcomes. These studies focus on reducing the effects of potential alternative factors or explanations when estimating the complex associations between treatments and outcomes within a specific care context (Horn et al., 2005). However, the identified associations between treatment and outcome are not considered causal links. The associations still inform causal judgments to the extent that the research design can measure and statistically control for these confounders or alternative explanations.

The PBE approach does not infer causality directly like RCTs, but several sources indicate the strength of the evidence that a causal link exists. First, alternative hypotheses regarding possible causes are tested using a large number of available variables to identify additional potential variables that may influence outcomes. Results can be used to drill down to discover potential alternative causes and to generate additional specific hypotheses. Analyses continue until the project team is satisfied that they cannot think of any other variables to explain the outcomes. Second, one can test the predictive validity of significant PBE findings by introducing findings into clinical practice and assessing whether outcomes change when treatments change, as predicted by PBE models. Third, studies can be repeated in different healthcare settings and assessed to determine if the findings remain the same.

Underlying the common criticism of observational studies (that they demonstrate association but not causation) is an unchallenged assumption that the evidence for causation is dichotomous; that is, something either is or is not the cause. Instead, the evidence for causation should be viewed as a continuum that extends from mere association to undeniable causation. While observational studies cannot prove causation in some absolute sense, by chipping away at potential confounders and by testing for predictive validity in follow-up studies, we move upward on the continuum from mere association to causation. PBE studies offer a methodology for moving up this continuum.

Research design involves a balance of internal validity (the validity of the causal inference that the treatment is the “true” cause of the outcome) and external validity (the validity that the causal inference can be generalized to other subjects, forms of the treatment, measures of the outcome, practitioners, and settings). Essentially, PBE designs trade away the internal validity of RCTs for external validity (Mitchell & Jolley, 2001). PBE designs have high external validity (generalizability) because they include virtually all patients with or at risk for the condition under study, as well as potential confounders that could alter treatment responses. PBE designs attempt to minimize threats to internal validity by collecting information on all patient variables—demographic, medical, nursing, functional, and socioeconomic—that might account for differences in outcome. By doing so, PBE designs minimize the need for compensating statistical techniques such as instrumental variables and propensity scoring to mitigate selection bias effects, unknown sources of variance, and threats to internal validity.

PBE study designs attempt to capture the complexity of the healthcare process presented by patient and treatment differences in routine care; PBE studies do not alter or standardize treatment regimens to evaluate the efficacy of a specific intervention or combination of interventions, as one usually does in an RCT or other types of experimental designs (Horn & Gassaway, 2007, 2010). PBE studies measure multiple concurrent interventions, patient characteristics, and outcomes. This comprehensive framework provides for consequential analyses of significant associations between treatment combinations and outcomes, controlling for patient differences.

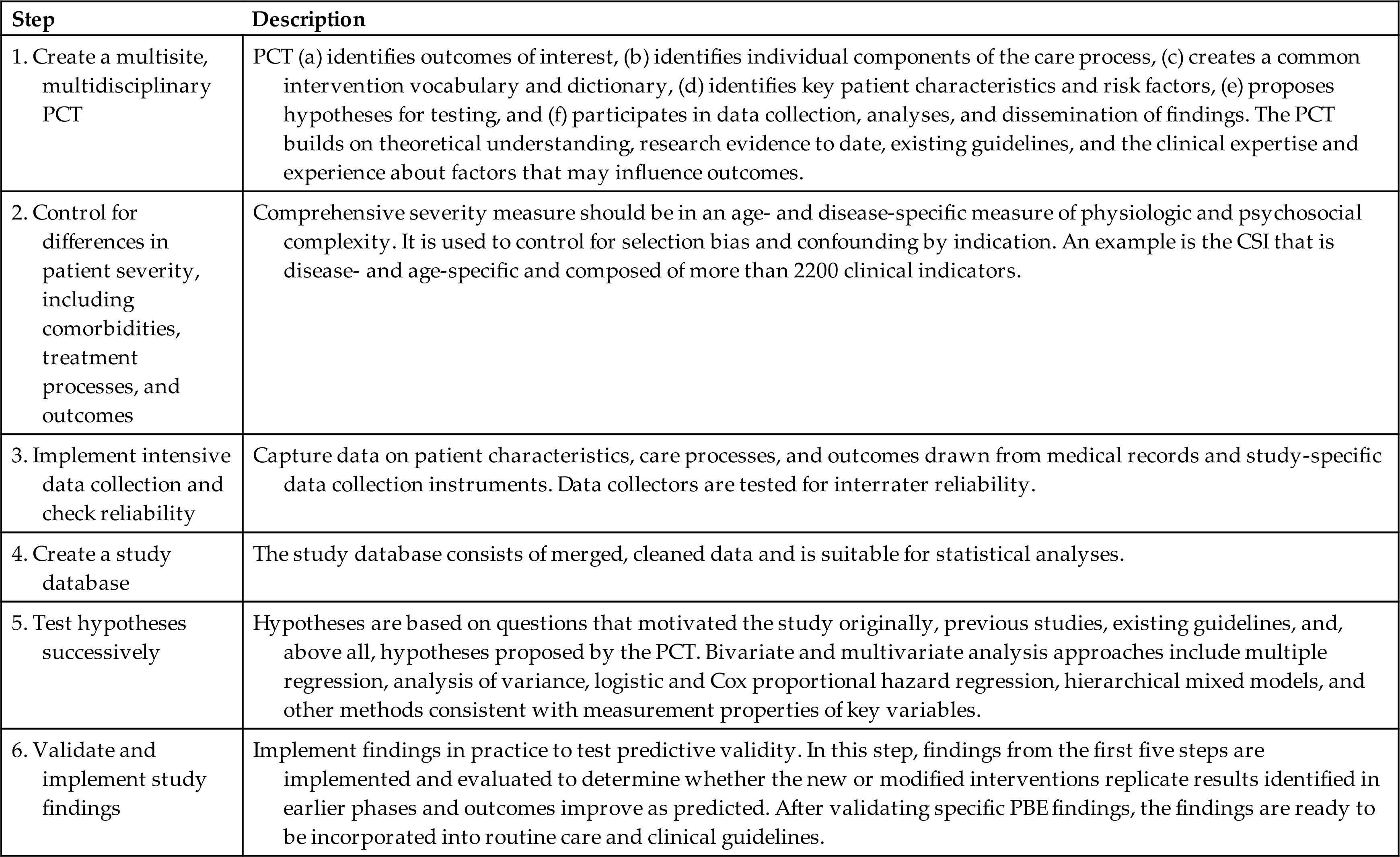

Steps in a Practice-Based Evidence Study

Table 11.6 outlines the steps involved in conducting a PBE study and gives a brief description of what each step involves. Once a clinical issue is identified, PBE methods by forming a multidisciplinary team, often with representatives of multiple sites. Participation of informaticians on the team is critical to ensuring that the electronic documentation facilitates data capture for the research and clinical practice without undue documentation burden.

Table 11.6

CSI, Comprehensive Severity Index; PBE, practice-based evidence; PCT, project clinical team.

Create a Multisite, Multidisciplinary Project Clinical Team

One factor that distinguishes PBE studies from most other observational studies is the extensive involvement of frontline clinicians and patients. Frontline clinicians and patients are engaged in all aspects of PBE projects; they identify data elements to be included in the PBE project based on initial study hypotheses, extensive literature review, and clinical experience and training, as well as patient experience. Many relevant details about patients, treatments, and outcomes may be recorded in existing EHRs; however, the project clinical team (PCT) often identifies additional critical variables that must be collected in supplemental standardized documentation developed specifically for the PBE study. Clinicians and patients also participate in data analyses leading to publication. Front-to-back clinician and patient participation foster high levels of clinician and patient buy-in that contribute to data completeness and clinical ownership of study findings, even when findings challenge conventional wisdom and practice. Such ownership is essential to knowledge translation and best practice.

Control for Differences in Patient Severity of Illness

Controls for patient factors

PBE designs require the recording of each subject's treatment as determined by clinicians in practice rather than by randomizing subjects to neutralize the effect of patient differences. PBE studies address patient differences by measuring a wide variety of patient characteristics that go beyond race, gender, age, payer, and other variables that can be exported from administrative, registry, or EHR databases, and then accounting for patient differences through statistical control.

The goal is to measure all variables contributing to outcomes to have the information needed to control for patient differences. This is the primary reason for including frontline clinicians and patients in PBE study design and implementation. There always remains the possibility that some patient characteristic may be overlooked. Still, PBE’s exhaustive patient characterization significantly minimizes the chances of not being able to resolve unknown sources of variance because of patient differences.

One critical component of the PBE study design is the use of tools for measuring the degree of illness, such as the Comprehensive Severity Index (CSI) ((Horn et al., 2005; Horn et al., 2001; Averill et al., 1992; Clemmer et al., 1999; Horn et al., 2002; Willson et al., 2000; Ryser et al., 2005; Horn et al., 1991; Gassaway et al., 2005; Carter et al., 2009; Rosenbaum, 2002). In PBE studies, the CSI can be used to measure how ill a patient is at the time of presentation for care, as well as over time. Degree of illness is defined as the extent of deviation from “normal values.” CSI is “physiologically-based, age- and disease-specific, independent of treatments, and provides an objective, consistent method to define patient severity of illness levels based on over 2,200 signs, symptoms, and physical findings related to a patient’s disease(s), not just diagnostic information, such as ICD-9-CM coding alone.”67 The validity of CSI has been studied for over 30 years in various clinical settings and conditions such as inpatient adult and pediatric conditions, ambulatory care, rehabilitation care, hospice care, and long-term care settings (Averil et al., 1992; Carter et al., 2009). Patient diagnosis codes and data management rules are used to calculate severity scores for each patient overall and separately for each patient’s disease (principal and each secondary diagnosis).

CSI and other measures of patient key characteristics, such as level and completeness of spinal cord injury, severity of stroke disability, or severity of traumatic brain injury, control for patient differences. Using these patient differences can help to account for treatment selection bias or confounding by indication in analyses.

Controls for treatment and process factors

Treatment in clinical settings is often determined by facility standards, regional differences, and clinician training. Therefore, like patient differences, treatment differences must be recorded during a PBE study. The goal is to find measurable factors that describe each treatment to be compared. Examples include the medications dispensed and their dosage; rehabilitation therapies performed and duration on each day of treatment; content, mode, and amount of patient education; and nutritional consumption.

PBE identifies better practices by examining how different approaches to care are associated with outcomes of care while controlling for patient variables. PBE does not require providers to follow treatment protocols or exclude certain treatment practices. However, characteristics of treatment, including timing and dose, require detailed documentation. These characteristics must be defined by the PBE team and measured in a structured, standard manner for all participating sites and their clinicians. Consistency is critical for minimizing variation in data collection and documentation (Horn et al., 2012).

The level of detail found in routine documentation of interventions may be insufficient. Each PBE team must assess the level of detail afforded by routine documentation and determine whether supplemental documentation is necessary (Horn et al., 2012). Further, point-of-care documentation or EHR data are pilot tested to ensure the complete representation of variables. Pilot testing ensures that point-of-care documentation or EHR data collection captures all elements that clinicians suggest may affect the outcomes of their patients. If a variable is not measured, it cannot be used in subsequent analyses.

Controls for outcome factors

Multiple outcomes can be addressed in a single PBE project; projects are not limited to one primary outcome, as in other study designs. In particular, PBE studies incorporate widely accepted, standard measures. For example, the Braden Scale for Risk of Pressure Ulcer Development is commonly collected in PBE studies, and it has been used as both a control and an outcome variable (Carter et al., 2009; Rosenbaum, 2002; Horn et al., 2012). Although PBE projects incorporate as many standard measures as possible, they also include outcome measures specific to the study topic. Additional patient outcomes commonly assessed in PBE studies are condition-specific complications, condition-specific long-term medical outcomes (based on clinician assessment or patient self-report), condition-specific patient-centered measures of activities and participation in society, patient satisfaction, quality of life, and cost (Deutscher et al., 2009).

Some outcomes (e.g., discharge destination [home, community, and institution], length of stay, or death) are commonly available in administrative databases. Other outcome variables (e.g., repeat stroke, deep vein thrombosis, pain, electrolyte imbalance, and anemia) are found in traditional paper charts or EHR documentation. However, they typically are available only up to discharge from the care setting.

Implement Intensive Data Collection and Check Reliability

Using the data elements identified in step 2, historical data are collected from the EHR. Direct care providers document the specific elements of treatment at the POC. For example, if the treatment includes physical therapy, the type, intensity, and duration are precisely recorded during each therapy session. If the healthcare provider offers patient counseling or education, the teaching methods, instructional materials, topical content, and duration of each teaching session are recorded. The informatics specialist is a critical partner in designing the data capture to prevent the need for parallel documentation. If the documentation is too burdensome, clinicians will not comply with documentation requirements, and the data will be incomplete. Therefore, the design of the data collection is critical to the success of this research approach. The fact that the frontline clinicians define these data collection formats helps ensure that the data collection formats are specifically designed so that data can be documented easily and quickly.

Create a Study Database

The elements of data that are collected are compiled into a study-specific database with the assistance of informatics personnel. Data sources include existing or new clinician documentation of care delivered. Patients drop out of a PBE study if they leave the care setting before completion of treatment or drop out during follow-up (Deutscher et al., 2009). Patients who withdraw from a treatment do not distort the results of PBE study findings because PBE studies follow patients throughout the care process, taking date and time measurements on all therapies. Hence, if a patient withdraws from care of the study, investigators can use the existing data in the analyses, controlling for time in the study. PBE studies have an advantage because of their large sample size, number of information points, and complete comparison of those subjects who complete therapy and those who withdraw.

Successively Test Hypotheses

PBE studies use multivariable analyses to identify variables most strongly associated with outcomes. Detailed characterization of patients and treatments allows researchers to specify direct effects, indirect effects, and interactions that might not otherwise become apparent with less detailed data. CSI (overall, individual components, or individual severity indicators) can be used in data analysis to represent the role of comorbid and co-occurring conditions along with the principal diagnosis. Suppose a positive outcome is found to be associated with a specific treatment or combination of treatments. In that case, the subsequent methodological approach is to include confounding patient variables or combinations of variables in the analysis in an attempt to “disconfirm” the association. The association may remain robust, or variables may be identified that explain the outcome more adequately.

Data in PBE studies include many clinical and therapeutic variables, and a selection procedure is applied to decide on significant variables to retain in regressions. Only variables suggested by the team based on the literature and team members’ education and clinical experience and with frequencies equal to or greater than 10 to 20 patients in the sample are usually allowed.

Analyses conducted using PBE databases are iterative. Counterintuitive findings are investigated thoroughly. In fact, counterintuitive and unexpected findings often lead to discoveries of important associations of treatments with outcomes.

Large numbers of patients (usually >1000 and often >2000) and considerable computing power are required to perform PBE analyses. When multiple outcomes are of interest, and there is little information on the effect size of each predictor variable, sample size is based on the project team’s desire to find small, medium, or large effects of patient and process variables.

Validate and Implement Findings

See the exemplar in Box 11.10 showing how a PBE study of stroke rehabilitation culminated in validation studies and changes in the standard of care in a healthcare system. Because PBE studies are observational, the conclusions require prospective validation before being incorporated into clinical guidelines and standards of care. Validation of PBE findings can use a CQI approach consisting of the systematic implementation of those interventions that were found to be better, in conjunction with monitoring their outcomes. If the findings from the outcome assessment replicate the findings of the initial retrospective stage in multiple settings and populations, the intervention would be a candidate for incorporation into clinical guidelines as a care process that has established efficacy and effectiveness. This is in contrast to interventions that only have RCT evidence, which generally indicates only efficacy.

Limitations and Strengths of Practice-Based Evidence Studies

PBE methods work best in situations where one wishes to study existing clinical practice. However, there are no limitations related to conditions or settings for the use of PBE study methods. The technique can be time-consuming in terms of conducting the initial PBE steps, as well as data extraction. Although the relevant variables may change, PBE study designs have been found to work in various practice settings, including acute and ambulatory care, inpatient and outpatient rehabilitation, hospice, and long-term care, and for adult and pediatric patients.

Informatics and Practice-Based Evidence

Challenges to Practice-Based Evidence Integration With Electronic Health Records

Data elements needed for PBE, and especially for CSI, can be captured in structured, exportable formats while also being used for clinical documentation of care EHR use in patient care as research expands. This concept is implemented already in health systems in Israel and various PBE studies in the United States (Deutscher et al., 2008). However, transitioning to EHRs presents its own challenges, especially for data-intensive PBE studies. EHRs can facilitate data acquisition, but they are not always research-friendly because many desired data elements are in text, such as clinical notes, and cannot be exported easily. If EHR data cannot be exported directly, they must be abstracted manually or alternatively, processed using Natural Language Processing (NLP) methods (Spyns, 1996). Whereas manual abstraction from EHR can be more labor-intensive than abstracting paper charts are, when relying on NLP methods, a bulk of the effort is spent on training the computer algorithms to extract the needed data elements. In addition, EHR modifications for optimizing point-of-care data documentation and abstraction are costly and time-consuming, potentially slowing down the planning and implementation of PBE studies based on routine electronic data capture. With HITECH, EHRs have become pervasive in clinical practice (Mennemeyer et al., 2016). Over time, new EHR exporting and reporting software are emerging, making EHR data abstraction less labor-intensive.

Examination of CSI elements themselves may show a reduced set that differentiates severity, as well as the full set. It is possible that two valid data elements would each contribute clinically unique information but be fully redundant with respect to their ability to differentiate severity in a population. For example, unresponsive neurological status and fever ≥ 104 degrees are clinically unique indicators of severity in pneumonia. If these indicators differentiate only the same most gravely ill pneumonia patients from the rest of the population, they provide redundant information with respect to the severity of pneumonia. In this case, it may be possible to use only one of the two indicators in CSI scoring, reducing the information burden to compute a CSI score and increasing efficiency.

Comparative Effectiveness Research

PBE requires a multidisciplinary team approach for comparative effectiveness research and ensures inclusion of a wide spectrum of variables so that differences in patient characteristics and treatments are measured and controlled statistically (Horn et al., 2012).

The next step for comparative effectiveness research is to conduct more rigorous, prospective large-scale observational cohort studies. National efforts such as the Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute’s (PCORI) Clinical Data Research Networks (CDRN) can enable comparative effectiveness research and PBE by providing informatics solutions for sharing data across multiple institutions (Amin et al., 2014). From a PBE perspective, rigor entails controlled measurement of outcomes related to multiple intervention combinations and a variety of patient characteristics in diverse clinical settings (Horn et al., 2012). PBE studies address questions in the real world where multiple variables and factors can affect the outcomes; they can fit seamlessly into everyday clinical documentation and, therefore, have the potential to influence and improve the evidence in EBP in the real-world clinical environment of patient care.

Conclusion and Future Directions