Definition of anemia

A functional definition of anemia is a decrease in the oxygen-carrying capacity of the blood. It can arise if there is insufficient hemoglobin or the hemoglobin has impaired function. The former is the more frequent cause.

Anemia is defined operationally as a reduction in the hemoglobin content of blood that can be caused by a decrease in the RBC count, hemoglobin concentration, and hematocrit below the reference interval for healthy individuals of similar age, sex, and race, under similar environmental conditions.4-8 The reference intervals are derived from large pools of “healthy” individuals; however, the definition of healthy is different for each of these groups. Thus these pools of “healthy” individuals may lack the heterogeneity required to be universally applied to any one of these populations of individuals.6 This fact has led to the development of different reference intervals for individuals of different sex, age, and race.

Examples of hematologic reference intervals for the adult and pediatric populations are included on the inside cover. They are listed according to age and sex, but race, environmental, and laboratory factors can also influence the values. Each laboratory must determine its own reference intervals based on its particular instrumentation, the methods used, and the demographic characteristics and environment of its patient population. For the purpose of the discussion in this chapter, a patient is considered anemic if the hemoglobin value falls to less than those listed on the inside cover.

Importance of patient history and clinical findings

History and physical examination are important components in making a clinical diagnosis of anemia. A decrease in oxygen delivery to tissues decreases the energy available to individuals to perform day-to-day activities. This gives rise to the classic symptoms associated with anemia, fatigue and shortness of breath. To elucidate the reason for a patient’s anemia, one starts by obtaining a detailed history, which requires carefully questioning the patient, particularly with regard to diet, drug ingestion, exposure to chemicals, occupation, hobbies, travel, bleeding history, race or ethnic group, family history of disease, neurologic symptoms, previous medications, previous episodes of jaundice, and various underlying disease processes that result in anemia.4,7-9 Therefore a thorough discussion is required to elicit any potential cause of the anemia. For example, iron deficiency can lead to an interesting symptom called pica.10 Patients with pica have cravings for unusual substances such as ice (pagophagia), cornstarch, or clay. Alternatively, individuals with anemia may be asymptomatic, as can be seen in mild or slowly progressive anemias where the body is able to adapt to the slowly developing anemia.

Certain features should be evaluated closely during the physical examination to provide clues to hematologic disorders, such as skin (for petechiae), eyes (for pallor, jaundice, and hemorrhage), and mouth (for mucosal bleeding). The examination should also search for sternal tenderness, lymphadenopathy, cardiac murmurs or arrhythmias, splenomegaly, and hepatomegaly.4,11 Jaundice is important for the assessment of anemia, because it may be due to increased RBC destruction, which suggests a hemolytic component to the anemia. Measuring vital signs is also a crucial component of the physical evaluation. Patients experiencing a rapid fall in hemoglobin concentration typically have tachycardia (fast heart rate), whereas if the anemia is long-standing, the heart rate may be normal because of the body’s ability to compensate for the anemia (discussed later).

Moderate anemias (hemoglobin concentration of 7 to 10 g/dL) may cause pallor of conjunctivae and nail beds but may not produce clinical symptoms if the onset of anemia is slow.4 However, depending on the patient’s age and cardiovascular state, symptoms such as dyspnea, vertigo, headache, muscle weakness, and lethargy can occur.4,8 Severe anemias (hemoglobin concentration of less than 7 g/dL) usually produce tachycardia, hypotension, and other symptoms of volume loss, in addition to the symptoms listed earlier. Thus severity of the anemia is gauged by the degree of reduction in hemoglobin, cardiopulmonary adaptation, and the rapidity of progression of the anemia.4

Physiologic adaptations in patients with anemia

Patients who develop anemia from acute blood loss, such as with severe hemorrhage, respond with profound changes in physiologic processes to ensure adequate perfusion of vital organs and maintenance of homeostasis. In cases of severe blood loss, such as in trauma, blood volume decreases and hypotension develops, resulting in decreased blood supply to the brain and heart. As an immediate adaptation, there is sympathetic overdrive that results in increasing heart rate, respiratory rate, and cardiac output.4,7,8 In severe anemia, blood is preferentially shunted to organs that are key to survival, including the brain, muscle, and heart.4,7,8 This results in oxygen being preferentially supplied to vital organs even in the presence of reduced oxygen-carrying capacity. In addition, tissue hypoxia triggers an increase in RBC 2,3-bisphosphoglycerate that shifts the oxygen dissociation curve to the right (decreased oxygen affinity of hemoglobin) and results in increased oxygen delivery to tissues (Chapter 7).8,12 This is also a significant mechanism in chronic anemias that enables patients with low levels of hemoglobin to remain relatively asymptomatic. Thus with slowly developing and low-grade anemia, the body develops physiologic adaptations to increase the oxygen-carrying capacity of a reduced amount of hemoglobin, which improves oxygen delivery to tissues. With persistent and severe anemia, however, the strain on the heart can ultimately lead to cardiac failure.

Reduced oxygen delivery to tissues caused by reduced hemoglobin concentration elicits an increase in erythropoietin secretion by the kidneys. Erythropoietin stimulates the erythroid precursors in the bone marrow, which leads to the release of more RBCs into the circulation7,8 (Chapter 5).

With rapid blood loss, the hemoglobin and hematocrit may be initially unchanged because there is balanced loss of plasma and cells. However, as the drop in blood volume is compensated for by movement of fluid from the extravascular to the intravascular compartment or by administration of resuscitation fluid, there will be a dilution of RBCs and anemia. Box 16.1 summarizes the body’s physiologic adaptations to anemia.

Mechanisms of anemia

The life span of an RBC in circulation is about 120 days. In a healthy individual with no anemia, each day approximately 1% of RBCs are removed from circulation because of senescence, but the bone marrow continuously produces RBCs to replace those lost. Hematopoietic stem cells differentiate into erythroid precursor cells, and the bone marrow releases reticulocytes (immature anucleated RBCs) that mature into RBCs in the peripheral circulation. Adequate RBC production requires several nutritional factors such as iron, vitamin B12, and folate. Globin (polypeptide chain) synthesis must also function normally. In conditions with excessive bleeding or hemolysis, the bone marrow must increase RBC production to compensate for the increased RBC loss. Therefore the maintenance of a stable hemoglobin concentration requires the production of functionally normal RBCs in sufficient numbers to replace the amount lost.4

Ineffective and insufficient erythropoiesis

Erythropoiesis is the term used for marrow erythroid proliferative activity. Normal erythropoiesis occurs in bone marrow and is under the control of the hormone erythropoietin (produced by the kidney) and other growth factors and cytokines (Chapters 4 and 5).7,8 When erythropoiesis is effective, bone marrow is able to produce functional RBCs that replace the daily loss of RBCs.

Ineffective erythropoiesis refers to the production of erythroid precursor cells that are defective. These defective precursors often undergo apoptosis (programmed cell death) in the bone marrow before they have a chance to mature to the reticulocyte stage and be released into the peripheral circulation. Several conditions, such as megaloblastic anemia (impaired deoxyribonucleic acid [DNA] synthesis as a result of vitamin B12 or folate deficiency), thalassemia (deficient globin chain synthesis), and sideroblastic anemia (deficient protoporphyrin synthesis), involve ineffective erythropoiesis as a mechanism of anemia. In these anemias, peripheral blood hemoglobin concentration is low, which triggers an increase in erythropoietin production leading to increased erythropoietic activity. Although the RBC production rate is high, it is ineffective in that many of the defective erythroid precursors undergo destruction in the bone marrow. The end result is a decreased number of circulating RBCs resulting in anemia.4,11

Insufficient erythropoiesis refers to a decrease in the number of erythroid precursors in the bone marrow, resulting in decreased RBC production and anemia. Many factors can lead to the decreased RBC production, including a deficiency of iron (inadequate intake, malabsorption, excessive loss from chronic bleeding); a deficiency of erythropoietin (renal disease); or loss of the erythroid precursors as a result of an autoimmune reaction (aplastic anemia, acquired pure red cell aplasia) or infection (parvovirus B19). Erythropoiesis can also be suppressed by infiltration of the bone marrow space with leukemia cells or with nonhematopoietic cells (metastatic tumors, granulomas, or fibrosis), the latter called myelophthisic anemia with characteristic teardrop RBCs.4,7,12

Blood loss and hemolysis

Anemia can also develop as a result of acute blood loss (such as a traumatic injury) or chronic blood loss (such as an intermittently bleeding colonic polyp). Increased hemolysis results in a shortened RBC life span, thus increasing the risk for anemia. Chronic blood loss induces iron deficiency as a cause of anemia. With acute blood loss and excessive hemolysis, the bone marrow takes a few days to increase production of RBCs.4,7,8 This response may be inadequate to compensate for a sudden excessive RBC loss as in traumatic hemorrhage or in conditions with a high rate of hemolysis and shortened RBC survival. Numerous causes of hemolysis exist, including intrinsic defects in the RBC membrane, enzyme systems, or hemoglobin, or extrinsic causes such as antibody-mediated processes, mechanical fragmentation, or infection-related destruction.4,7,8

Laboratory diagnosis of anemia

Complete blood count with red blood cell indices

To detect the presence of anemia, the medical laboratory professional performs a complete blood count (CBC) using an automated blood cell analyzer to determine the RBC count, hemoglobin concentration, hematocrit, RBC indices, white blood cell count, and platelet count (Chapter 12). The RBC indices include the mean cell volume (MCV), mean cell hemoglobin (MCH), and mean cell hemoglobin concentration (MCHC) (Chapter 11).13 The most important of these indices is the MCV, a measure of the average RBC volume in femtoliters (fL). Reference intervals for these determinations are listed on the inside front cover and in Table 16.1. Automated blood cell analyzers also provide the red cell distribution width (RDW), an index of variation of cell volume in an RBC population (discussed later). A reticulocyte count should be performed for every patient with anemia. As with RBCs, automated analyzers provide accurate measurements of reticulocyte counts.

TABLE 16.1

| Test | Formula | Adult Reference Interval |

| Absolute reticulocyte count (× 109/L) | = [reticulocytes (%)/100] × RBC count (× 1012/L) | 20–115 × 109/L |

| Corrected reticulocyte count (%) | = reticulocytes (%) × patient’s HCT (%)/45 | — |

| Reticulocyte production index (RPI) | = corrected reticulocyte count/maturation time | In anemic patients, RPI should be >3 |

| Mean cell volume (MCV) (fL) | = HCT (%) × 10/RBC count (× 1012/L) | 80–100 fL |

| Mean cell hemoglobin (MCH) (pg) | = HGB (g/dL) × 10/RBC count (× 1012/L) | 26–32 pg |

| Mean cell hemoglobin concentration (MCHC) (g/dL) | = HGB (g/dL) × 100/HCT (%) | 32–36 g/dL |

HGB, Hemoglobin; HCT, hematocrit; RBC, red blood cell.

The RBC histogram provided by the automated analyzer is an RBC volume frequency distribution curve with the relative number of cells plotted on the ordinate and RBC volume (fL) on the abscissa. In healthy individuals the distribution is approximately Gaussian. Abnormalities include a shift in the curve to the left (smaller cell population or microcytosis) or to the right (larger cell population or macrocytosis). A widening of the curve occurs when a population of RBCs have different volumes causing a greater variation of RBC volume about the mean. The histogram complements the peripheral blood film examination in identifying abnormal RBC populations. A discussion of histograms with examples can be found in Chapters 12 and 13.

RDW is the coefficient of variation of RBC volume expressed as a percentage.13 It indicates the variation in RBC volume within the population measured and an increased RDW correlates with anisocytosis (variation in RBC diameter) on the peripheral blood film. Automated analyzers calculate the RDW by dividing the standard deviation of the RBC volume by the MCV and then multiplying by 100 to convert to a percentage. Clinical usefulness of the RDW is discussed later.

Reticulocyte count

The reticulocyte count serves as an important tool to assess the bone marrow’s ability to increase RBC production in response to an anemia. Reticulocytes are young RBCs that lack a nucleus but still contain residual ribonucleic acid (RNA) to complete the production of hemoglobin. Normally they circulate peripherally for only 1 day while completing their development. The adult reference interval for the reticulocyte count is 0.5% to 2.5% expressed as a percentage of the total number of RBCs.13 The newborn reference interval is 1.5% to 6.0%, but these values change to approximately those of an adult within a few weeks after birth.13 An absolute reticulocyte count is determined by multiplying the percent reticulocytes by the RBC count (Table 16.1). The reference interval for the absolute reticulocyte count is 20 to 115 × 109/L, based on an adult RBC count within the reference interval (inside front cover).4,7 A patient with a severe anemia may seem to be producing increased numbers of reticulocytes if only the percentage is considered. For example, an adult patient with 1.5 × 1012/L RBCs and 3% reticulocytes has an absolute reticulocyte count of 45 × 109/L. The percentage of reticulocytes exceeds the reference interval, but the absolute reticulocyte count is within the reference interval. For the degree of anemia, however, both these results are inappropriately low. In other words, production of reticulocytes within the reference interval is inadequate to compensate for an RBC count that is approximately one-third of normal.

Two successive corrections are made to the reticulocyte count to obtain a better representation of RBC production. First, to obtain a corrected reticulocyte count, one corrects for the degree of anemia by multiplying the reticulocyte percentage by the patient’s hematocrit and dividing the result by 45 (the average normal hematocrit). If the reticulocytes are released prematurely from the bone marrow and remain in the circulation 2 to 3 days (instead of 1 day), the corrected reticulocyte count must be divided by maturation time to determine the reticulocyte production index (RPI) (Table 16.1). The RPI is a better indication of the rate of RBC production than is the corrected reticulocyte count.4 The reticulocyte count and derivation of RPI is discussed in Chapter 11.

In addition, state-of-the-art automated blood cell analyzers determine the fraction of immature reticulocytes among the total circulating reticulocytes, called the immature reticulocyte fraction (IRF). The IRF is helpful in assessing early bone marrow response after treatment for anemia and is covered in Chapter 12.

Analysis of the reticulocyte count plays a crucial role in determining whether an anemia is due to an RBC production defect or to premature hemolysis and shortened survival defect. If there is shortened RBC survival, as in the hemolytic anemias, the bone marrow tries to compensate by increasing RBC production to release more reticulocytes into the peripheral circulation. Although an increased reticulocyte count is a hallmark of the hemolytic anemias, it can also be observed after acute blood loss (Chapter 20).4,7,8 Chronic blood loss, on the other hand, does not lead to an appropriate increase in the reticulocyte count, but rather leads to iron deficiency and a subsequent low reticulocyte count. Thus an inappropriately low reticulocyte count results from decreased production of normal RBCs, as a result of either insufficient or ineffective erythropoiesis.

Peripheral blood film examination

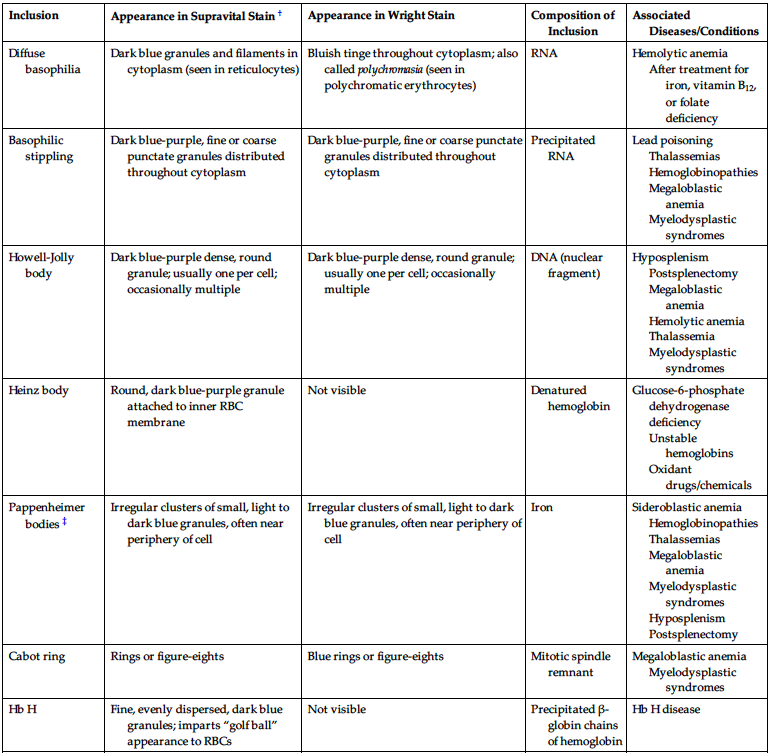

An important component in the evaluation of an anemia is examination of the peripheral blood film, with particular attention to RBC diameter, shape, color, and inclusions. The peripheral blood film also serves to verify the results produced by automated analyzers. Normal RBCs on a Wright-stained blood film are nearly uniform, ranging from 7 to 8 μm in diameter. Small or microcytic cells are less than 6 μm in diameter, and large or macrocytic RBCs are greater than 8 μm in diameter. Certain shape abnormalities of diagnostic value (such as sickle cells, spherocytes, schistocytes, and oval macrocytes) and RBC inclusions (such as malarial parasites, basophilic stippling, and Howell-Jolly bodies) can be detected only by studying the RBCs on a peripheral blood film (Tables 16.2 and 16.3). Examples of abnormal shapes and inclusions are provided in Figure 16.1.

TABLE 16.2

| RBC Abnormality | Cell Description | Commonly Associated Disease States |

|---|---|---|

| Anisocytosis | Abnormal variation in RBC volume or diameter | Hemolytic, megaloblastic, iron deficiency anemias |

| Macrocyte | Large RBC (>8 μm in diameter), MCV > 100 fL | Megaloblastic anemia |

| Myelodysplastic syndromes | ||

| Chronic liver disease | ||

| Bone marrow failure | ||

| Reticulocytosis | ||

| Oval macrocyte | Large oval RBC | Megaloblastic anemia |

| Microcyte | Small RBC (<6 μm in diameter), MCV < 80 fL | Iron deficiency anemia |

| Anemia of chronic inflammation | ||

| Sideroblastic anemia | ||

| Thalassemia/Hb E disease and trait | ||

| Poikilocytosis | Abnormal variation in RBC shape | Severe anemia; certain shapes helpful diagnostically |

| Spherocyte | Small, round, dense RBC with no central pallor | Hereditary spherocytosis |

| Immune hemolytic anemia | ||

| Extensive burns (along with schistocytes) | ||

| Elliptocyte, ovalocyte | Elliptical (cigar-shaped), oval (egg-shaped) RBC | Hereditary elliptocytosis or ovalocytosis |

| Iron deficiency anemia | ||

| Thalassemia major | ||

| Myelophthisic anemias | ||

| Stomatocyte | RBC with slit-like area of central pallor | Hereditary stomatocytosis |

| Rh deficiency syndrome | ||

| Acquired stomatocytosis (liver disease, alcoholism) | ||

| Artifact | ||

| Sickle cell | Thin, dense, elongated RBC pointed at each end; may be curved | Sickle cell anemia |

| Sickle cell-β-thalassemia | ||

| Hb C crystal | Hexagonal crystal of dense hemoglobin formed within the RBC membrane | Hb C disease |

| Hb SC crystal | Finger-like or quartz-like crystal of dense hemoglobin protruding from the RBC membrane | Hb SC disease |

| Target cell (codocyte) | RBC with hemoglobin concentrated in the center and around the periphery resembling a target | Liver disease

Hemoglobinopathies Thalassemia |

| Schistocyte (schizocyte) | Fragmented RBC caused by rupture in the peripheral circulation | Microangiopathic hemolytic anemia* (along with microspherocytes) |

| Macroangiopathic hemolytic anemia† | ||

| Extensive burns (along with microspherocytes) | ||

| Helmet cell (keratocyte) | RBC fragment in shape of a helmet | Same as schistocyte |

| Folded cell | RBC with membrane folded over | Hb C disease |

| Hb SC disease | ||

| Acanthocyte (spur cell) | Small, dense RBC with few irregularly spaced projections of varying length | Severe liver disease (spur cell anemia)

Neuroacanthocytosis (abetalipoproteinemia, McLeod syndrome) |

| Burr cell (echinocyte) | RBC with blunt or pointed, short projections that are usually evenly spaced over the surface of cell; present in all fields of blood film but in variable numbers per field‡ | Uremia

Pyruvate kinase deficiency |

| Teardrop cell (dacryocyte) | RBC with a single pointed extension resembling a teardrop or pear | Primary myelofibrosis |

| Myelophthisic anemia | ||

| Thalassemia | ||

| Megaloblastic anemia |

*Such as thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura, hemolytic uremic syndrome, disseminated intravascular coagulation.

†Such as traumatic cardiac hemolysis.

‡Cells with similar morphology that are unevenly distributed in a blood film (not present in all fields) likely are due to a drying artifact in blood film preparation; these artifacts are sometimes called crenated RBCs.

Hb, Hemoglobin; MCV, mean cell volume.

TABLE 16.3

| Inclusion | Appearance in Supravital Stain † | Appearance in Wright Stain | Composition of Inclusion | Associated Diseases/Conditions |

| Diffuse basophilia | Dark blue granules and filaments in cytoplasm (seen in reticulocytes) | Bluish tinge throughout cytoplasm; also called polychromasia (seen in polychromatic erythrocytes) | RNA | Hemolytic anemia

After treatment for iron, vitamin B12, or folate deficiency |

| Basophilic stippling | Dark blue-purple, fine or coarse punctate granules distributed throughout cytoplasm | Dark blue-purple, fine or coarse punctate granules distributed throughout cytoplasm | Precipitated RNA | Lead poisoning

Thalassemias Hemoglobinopathies Megaloblastic anemia Myelodysplastic syndromes |

| Howell-Jolly body | Dark blue-purple dense, round granule; usually one per cell; occasionally multiple | Dark blue-purple dense, round granule; usually one per cell; occasionally multiple | DNA (nuclear fragment) | Hyposplenism

Postsplenectomy Megaloblastic anemia Hemolytic anemia Thalassemia Myelodysplastic syndromes |

| Heinz body | Round, dark blue-purple granule attached to inner RBC membrane | Not visible | Denatured hemoglobin | Glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase deficiency

Unstable hemoglobins Oxidant drugs/chemicals |

| Pappenheimer bodies ‡ | Irregular clusters of small, light to dark blue granules, often near periphery of cell | Irregular clusters of small, light to dark blue granules, often near periphery of cell | Iron | Sideroblastic anemia

Hemoglobinopathies Thalassemias Megaloblastic anemia Myelodysplastic syndromes Hyposplenism Postsplenectomy |

| Cabot ring | Rings or figure-eights | Blue rings or figure-eights | Mitotic spindle remnant | Megaloblastic anemia

Myelodysplastic syndromes |

| Hb H | Fine, evenly dispersed, dark blue granules; imparts “golf ball” appearance to RBCs | Not visible | Precipitated β-globin chains of hemoglobin | Hb H disease |

*Inclusions of hemoglobin crystals (Hb S, Hb C, Hb SC) are covered in Table 16.2.

‡Stain dark blue and are called siderotic granules when observed in Prussian blue stain.

Hb, Hemoglobin; RBC, red blood cell.

Finally, a review of the white blood cells and platelets may help show that a more generalized bone marrow problem is leading to the anemia. For example, hypersegmented neutrophils can be seen in vitamin B12 or folate deficiency, whereas blast cells and decreased platelets may be an indication of acute leukemia. Chapter 13 contains a complete discussion of the peripheral blood film evaluation. Information from the blood film examination always complements the data from the automated blood cell analyzer.

Bone marrow examination

The cause of many anemias can be determined from the history, physical examination, and results of laboratory tests on peripheral blood. When the cause cannot be determined, however, or the differential diagnosis remains broad, bone marrow aspiration and biopsy may help in establishing the cause of anemia.4,8 Bone marrow examination is indicated for a patient with an unexplained anemia associated with or without other cytopenias, fever of unknown origin, or suspected hematologic neoplasm. Bone marrow examination evaluates hematopoiesis and can determine whether there is an infiltration of abnormal cells into the bone marrow. Important findings in bone marrow that can point to the underlying cause of the anemia include abnormal cellularity (e.g., hypocellularity in aplastic anemia); evidence of ineffective erythropoiesis and megaloblastic changes (e.g., folate/vitamin B12 deficiency or myelodysplastic syndromes); lack of iron on iron stains of bone marrow (the gold standard for diagnosis of iron deficiency); and the presence of granulomata, fibrosis, infectious agents, and tumor cells that may be inhibiting normal erythropoiesis. Chapter 14 discusses bone marrow procedures and bone marrow examination in detail.

Other tests that can assist in the diagnosis of anemia can be performed on a bone marrow specimen as well, including immunophenotyping of membrane antigens by flow cytometry (Chapter 28), cytogenetic studies (Chapter 30), and molecular analysis to detect specific genetic mutations and chromosome abnormalities in leukemia cells (Chapter 29).

Other laboratory tests

Other laboratory tests that can assist in establishing the cause of anemia include routine urinalysis (to detect hemoglobinuria or an increase in urobilinogen) with a microscopic examination (to detect hematuria or hemosiderin) and analysis of stool (to detect occult blood or intestinal parasites). Also, certain chemistry studies are very useful, such as serum haptoglobin, lactate dehydrogenase, and unconjugated bilirubin (to detect excessive hemolysis) and renal and hepatic function tests. With more patients having undergone gastric bypass surgery for obesity, certain rare deficiencies such as insufficient copper have become more common as another nutritional deficiency that can cause anemia.14

After the hematologic laboratory studies are completed, the anemia may be classified based on reticulocyte count, MCV, and peripheral blood film findings. Iron studies (including serum iron, total iron-binding capacity, transferrin saturation, and serum ferritin) are valuable if an inappropriately low reticulocyte count and a microcytic anemia are present. Serum vitamin B12 and serum folate assays are helpful in investigating a macrocytic anemia with a low reticulocyte count, whereas a direct antiglobulin test can differentiate autoimmune hemolytic anemias from other hemolytic anemias. Because of the numerous potential etiologies of anemia, the specific cause needs to be determined to initiate appropriate therapy.11

Approach to evaluating anemias

The approach to the patient with anemia begins with taking a complete history and performing a physical examination.4,7 For example, new-onset fatigue and shortness of breath suggest an acute drop in the hemoglobin concentration, whereas minimal or lack of symptoms suggests a long-standing condition where adaptive mechanisms have compensated for the drop in hemoglobin. A strict vegetarian may not be getting enough vitamin B12 in the diet, whereas an individual with alcoholism may not be getting enough folate. A large spleen may be an indication of hereditary spherocytosis, whereas a stool positive for occult blood may indicate iron deficiency. Thus a complete history and physical examination can yield information to narrow the possible cause or causes of the anemia and thus lead to a more rational and cost-effective approach to ordering the appropriate diagnostic tests.

The first step in the laboratory diagnosis of anemia is detecting its presence by the accurate measurement of the hemoglobin concentration, hematocrit, MCV, and RBC count and comparison of these values with the reference interval for healthy individuals of the same age, sex, race, and environment. Knowledge of previous hematologic values is valuable as a reduction of 10% or more in these values may be the first clue that an abnormal condition may be present.4,6,15

There are numerous causes of anemia, so a rational algorithm to initially evaluate this condition using the previously mentioned tests is required. A reticulocyte count and a peripheral blood film examination are of paramount importance in evaluating anemia.

The remainder of this chapter discusses the importance of individual RBC measurements, the MCV, reticulocyte count, and RDW and how they assist in classifying anemias so as to arrive at a specific diagnosis. Two widely used classification schemes for anemias relate to the morphology of red cells and the pathophysiologic condition responsible for the patient’s anemia.

Morphologic classification of anemia based on mean cell volume

The MCV is an extremely important tool and is key in the morphologic classification of anemia. Microcytic anemias are characterized by an MCV of less than 80 fL with small RBCs (less than 6 μm in diameter). Microcytosis is often associated with hypochromia (increased central pallor in RBCs) and an MCHC of less than 32 g/dL. Microcytic anemias are caused by conditions that result in reduced hemoglobin synthesis. Heme synthesis is diminished in iron deficiency, iron sequestration (chronic inflammatory states), and defective protoporphyrin synthesis (sideroblastic anemia, lead poisoning). Globin chain synthesis is insufficient or defective in thalassemia and in Hb E disease. Iron deficiency is the most common cause of microcytic anemia; the low iron level is insufficient for maintaining normal erythropoiesis. Although iron deficiency anemia is characterized by abnormal iron studies, the early stages of iron deficiency do not result in microcytosis or anemia and are manifested only by reduced iron stores. The causes of iron deficiency vary in infants, children, adolescents, and adults, and it is imperative to find the cause before beginning treatment (Chapter 17).

Macrocytic anemias are characterized by an MCV greater than 100 fL with large RBCs (greater than 8 μm in diameter). Macrocytic anemias arise from conditions that result in megaloblastic or nonmegaloblastic red cell development in bone marrow. Megaloblastic anemias are caused by conditions that impair synthesis of DNA, such as vitamin B12 and folate deficiency or myelodysplasia. Nuclear maturation lags behind cytoplasmic development as a result of the impaired DNA synthesis. This asynchrony between nuclear and cytoplasmic development results in larger cells. All cells of the body are ultimately affected by the defective production of DNA (Chapter 18). Pernicious anemia is one cause of vitamin B12 deficiency, whereas pregnancy with increased requirements is a leading cause of folate deficiency. Megaloblastic anemia is characterized by oval macrocytes and hypersegmented neutrophils in the peripheral blood and by megaloblasts or large nucleated erythroid precursors in the bone marrow. The MCV in megaloblastic anemia can be markedly increased (up to 150 fL), but modest increases (100 to 115 fL) are most common.

Nonmegaloblastic forms of macrocytic anemias are also characterized by large RBCs, but in contrast to megaloblastic anemias, they are typically related to membrane changes caused by disruption of the cholesterol-to-phospholipid ratio. These macrocytic cells are mostly round, and the erythroid precursors in the bone marrow do not display megaloblastic changes. Macrocytic anemias are often seen in patients with chronic liver disease, alcohol abuse, and bone marrow failure. It is rare for the MCV to be greater than 115 fL in nonmegaloblastic anemias.

Normocytic anemias are characterized by an MCV in the range of 80 to 100 fL. The RBC morphology on the peripheral blood film must be examined to rule out a dimorphic population of microcytes and macrocytes that can yield a normal MCV. The presence of a dimorphic population can also be verified by observing a bimodal distribution on the RBC histogram produced by an automated blood cell analyzer (Chapters 12 and 13). Some normocytic anemias develop as a result of the premature destruction and shortened survival of RBCs (hemolytic anemias), and they are characterized by an elevated reticulocyte count. The hemolytic anemias can be further divided into those that result from intrinsic causes (membrane defects, hemoglobinopathies, and enzyme deficiencies) and those that result from extrinsic causes (immune and nonimmune RBC injury). A direct antiglobulin test helps differentiate immune-mediated RBC destruction from other causes of hemolysis. In the hemolytic anemias, reviewing the peripheral blood film provides vital information for determining the cause of the hemolysis (Tables 16.2 and 16.3 and Figure 16.1). Hemolytic anemias are discussed in Chapters 20 to 24.

Other normocytic anemias develop as a result of a decreased production of RBCs and are characterized by a decreased reticulocyte count (Chapter 19). Figure 16.2 presents an algorithm for initial morphologic classification of anemia based on the MCV.

Morphologic classification of anemias and the reticulocyte count

The absolute reticulocyte count is useful in initially classifying anemias into the categories of decreased or ineffective RBC production (decreased reticulocyte count) and excessive RBC loss (increased reticulocyte count). Using the morphologic classification in the first category, when the reticulocyte count is decreased, the MCV can further classify the anemia into three subgroups: normocytic anemias, microcytic anemias, and macrocytic anemias. The excessive RBC loss category includes acute hemorrhage and the hemolytic anemias with shortened RBC survival. Figure 16.3 presents an algorithm that illustrates how anemias can be classified based on the absolute reticulocyte count and MCV.4,7

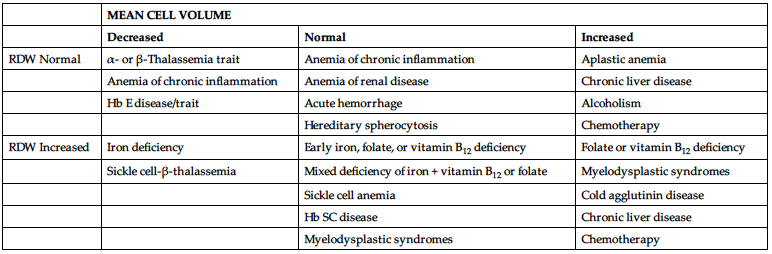

Morphologic classification and the red blood cell distribution width

The RDW can help determine the cause of an anemia when used in conjunction with the MCV. Each of the three MCV categories mentioned previously (normocytic, microcytic, macrocytic) can also be subclassified by the RDW as homogeneous (normal RDW) or heterogeneous (increased or high RDW).7,16 For example, a decreased MCV with an increased RDW is suggestive of iron deficiency (Table 16.4). This classification is not absolute, however, because there can be an overlap of RDW values among some of the conditions in each MCV category.

TABLE 16.4

| MEAN CELL VOLUME | |||

| Decreased | Normal | Increased | |

| RDW Normal | α- or β-Thalassemia trait | Anemia of chronic inflammation | Aplastic anemia |

| Anemia of chronic inflammation | Anemia of renal disease | Chronic liver disease | |

| Hb E disease/trait | Acute hemorrhage | Alcoholism | |

| Hereditary spherocytosis | Chemotherapy | ||

| RDW Increased | Iron deficiency | Early iron, folate, or vitamin B12 deficiency | Folate or vitamin B12 deficiency |

| Sickle cell-β-thalassemia | Mixed deficiency of iron + vitamin B12 or folate | Myelodysplastic syndromes | |

| Sickle cell anemia | Cold agglutinin disease | ||

| Hb SC disease | Chronic liver disease | ||

| Myelodysplastic syndromes | Chemotherapy | ||

*This classification scheme is not absolute because there can be overlap of RDW values among some of the conditions in each MCV category.

Modified from Bessman, J. D., Gilmer, P. R., & Gardner, F. H. (1983). Improved classification of anemias by MCV and RDW. Am J Clin Pathol, 80, 324; and Lin, J. C. (2018). Approach to anemia in the adult and child. In Hoffman, R., Benz, E. J., Silberstein, L. E., et al. (Eds.), Hematology: Basic Principles and Practice. (7th ed., p. 463). Philadelphia: Elsevier.

Hb, Hemoglobin.

Pathophysiologic classification of anemias and the reticulocyte count

In a pathophysiologic classification of anemia, related conditions are grouped by the mechanism causing the anemia. In this classification scheme, the anemias caused by decreased RBC production have inappropriately low reticulocyte counts (e.g., disorders of DNA synthesis and aplastic anemia) and are distinguished from other anemias caused by increased RBC destruction (intrinsic and extrinsic abnormalities of RBCs) or acute blood loss, which have increased reticulocyte counts. Some anemias have more than one pathophysiologic mechanism. Box 16.2 presents a pathophysiologic classification of anemia based on the causes of the abnormality and gives one or more examples of an anemia in each classification.

Summary

- • Anemia is defined operationally as a reduction in the hemoglobin content of blood that can be caused by a decrease in the red blood cell (RBC) count, hemoglobin concentration, and hematocrit below the reference interval for healthy individuals of the same age, sex, and race, under similar environmental conditions.

- • Diagnosis of anemia is based on history, physical examination, symptoms, and laboratory test results.

- • Many anemias have common manifestations. Careful questioning of the patient may reveal contributing factors, such as diet, medications, occupational hazards, and bleeding history.

- • A thorough physical examination is valuable in determining the cause of anemia. Some of the areas that should be evaluated are skin, nail beds, eyes, mucosa, lymph nodes, heart, spleen, and liver.

- • Moderate anemias (hemoglobin concentration between 7 and 10 g/dL) may cause pallor of conjunctivae and nail beds, but not manifest other clinical symptoms if the onset is slow. Severe anemias (hemoglobin concentration of less than 7 g/dL) usually produce pallor, dyspnea, vertigo, headache, muscle weakness, lethargy, hypotension, and tachycardia.

- • Laboratory procedures helpful in the initial diagnosis of anemia include the complete blood count (CBC) with RBC indices, red blood cell distribution width (RDW), and the reticulocyte count, and examination of the peripheral blood film. Examination of a peripheral blood film is especially important in the diagnosis of hemolytic anemias.

- • Bone marrow examination is usually not required for diagnosis of anemia but is indicated in cases of unexplained anemia, fever of unknown origin, or suspected hematologic neoplasm. Other tests are indicated based on the RBC indices, history, and physical examination, such as serum iron, total iron-binding capacity, and serum ferritin (for microcytic anemias) and serum folate and vitamin B12 (for macrocytic anemias).

- • The reticulocyte count and mean cell volume (MCV) play crucial roles in investigation of the cause of an anemia.

- • Morphologic classification of anemias is based on the MCV and includes normocytic, microcytic, and macrocytic anemias. The MCV, when combined with the reticulocyte count and the RDW, also can aid in classification of anemia.

- • Major subgroups of the pathophysiologic classification include anemias caused by decreased RBC production and those caused by increased RBC destruction or acute blood loss. Anemias may have more than one pathophysiologic cause.

- • The cause of anemia should be determined before treatment is initiated.

Now that you have completed this chapter, go back and read again the case study at the beginning and respond to the questions presented.

Review questions

Answers can be found in the Appendix.

- 1. Which of the following patients would be considered anemic with a hemoglobin value of 14.5 g/dL? Refer to reference intervals inside the front cover of this text.

- 2. Anemia most commonly presents with which one of the following set of symptoms:

- 3. Which of the following are important to consider in the patient’s history when investigating the cause of an anemia?

- 4. Which one of the following is reduced as an adaptation to long-standing anemia?

- 5. An autoimmune reaction destroys the hematopoietic stem cells in the bone marrow of a young adult patient, and the amount of active bone marrow, including erythroid precursors, is diminished. Erythroid precursors that are present are normal in appearance, but there are too few to meet the demand for circulating red blood cells, and anemia develops. The reticulocyte count is low. The mechanism of the anemia would be described as:

- 6. What are the initial laboratory tests that are performed for the diagnosis of anemia?

- 7. An increase in which one of the following suggests a shortened life span of RBCs and hemolytic anemia?

- 8. Which of the following is detectable only by examination of a peripheral blood film?

- 9. Schistocytes, ovalocytes, and acanthocytes are examples of abnormal changes in RBC:

- 10. Refer to Figure 16.3 to determine which one of the following conditions would be included in the differential diagnosis of an anemic adult patient with an absolute reticulocyte count of 20 × 109/L and an MCV of 65 fL.

- 11. Which one of the following conditions would be included in the differential diagnosis of an anemic adult patient with an MCV of 125 fL and an RDW of 20% (reference interval 11.5% to 14.5%)? Refer to Table 16.4.