3: Functional Anatomy of the Female Pelvic Floor

James A. Ashton-Miller, and John O.L. DeLancey

Introduction

The anatomic structures that prevent incontinence during elevations in abdominal pressure are primarily sphincteric, augmented secondarily by musculofascial supportive systems. In the urethra, for example, the action of the vesical neck and urethral sphincteric mechanisms at rest constrict the urethral lumen and keep urethral closure pressure higher than bladder pressure. The striated urogenital sphincter, the smooth muscle sphincter in the vesical neck and the circular and longitudinal smooth muscle of the urethra all contribute to this closure pressure. In addition, the mucosal and vascular tissues that surround the lumen provide a hermetic seal via coaptation, aided by the connective tissues in the urethral wall. Decreases in the number of striated muscle sphincter fibres occur with age and parity, but changes in the other tissues are not well understood.

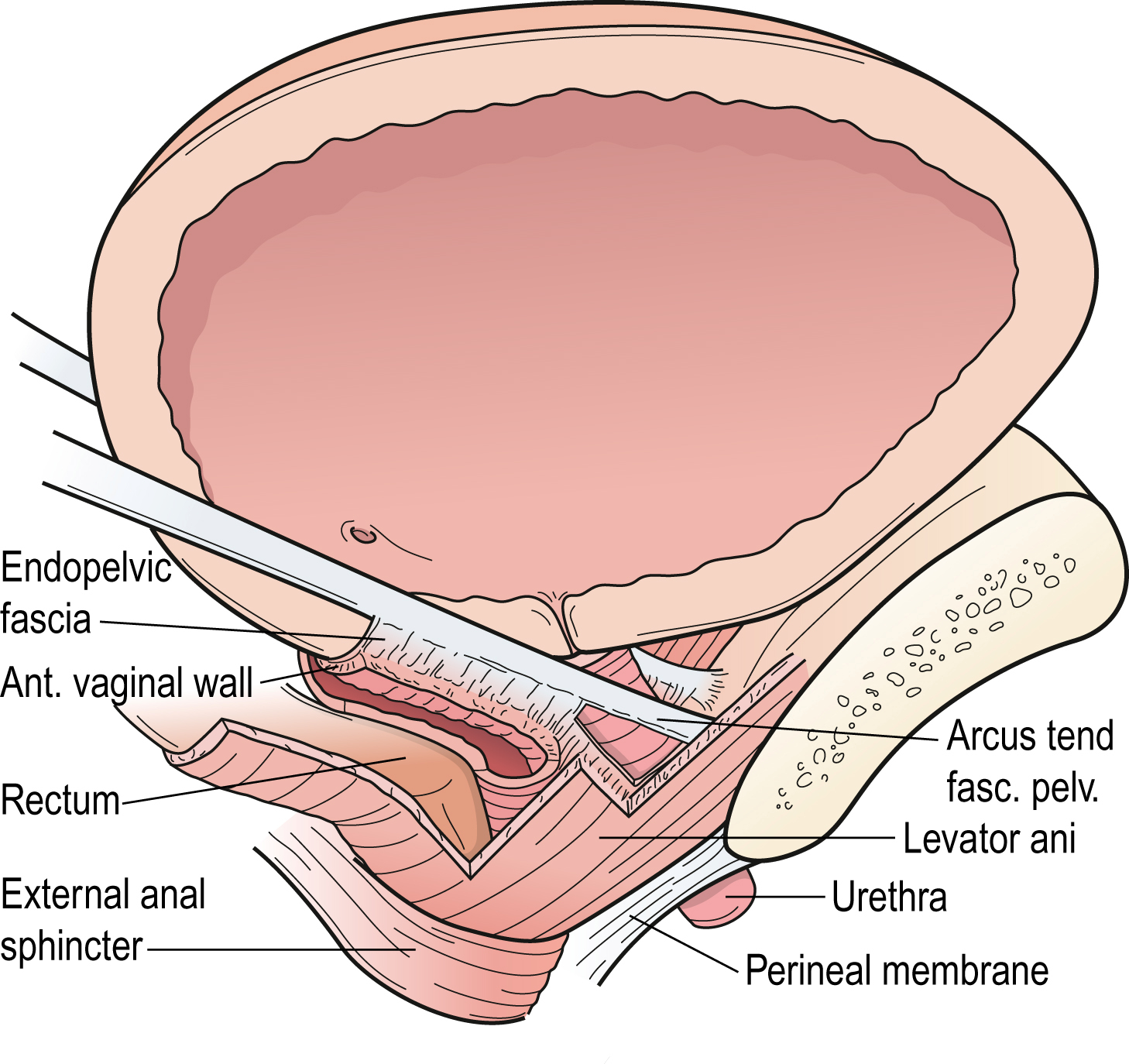

A supportive hammock under the urethra and vesical neck provides a firm backstop against which the urethra is compressed during increases in abdominal pressure to maintain urethral closure pressures above the rapidly increasing bladder pressure. This supporting layer consists of the anterior vaginal wall and the connective tissue that attaches it to the pelvic bones through the pubovaginal portion of the levator ani muscle and the uterosacral and cardinal ligaments comprising the tendinous arch of the pelvic fascia.

At rest the levator ani acts to maintain the urogenital hiatus closed in the face of hydrostatic pressure due to gravity and slight abdominal pressurization. During the dynamic activities of daily living the levator ani muscles are additionally recruited to maintain hiatal closure in the face of inertial loads related to having to decelerate caudal movements of the viscera as well as the additional load related to increases in abdominal pressure resulting from activation of the diaphragm and abdominal wall musculature.

Urinary incontinence is a common condition in women, with prevalence ranging from 8.5% to 38% depending on age, parity and definition (Thomas et al., 1980; Herzog et al., 1990). Most women with incontinence have stress urinary incontinence (SUI), not infrequently with urge incontinence (Diokno et al., 1987). Both types of incontinence are primarily due to an inadequate urethral sphincter which develops too little urethral closure pressure to prevent urine leakage (DeLancey et al., 2008, 2010). Usually this is treated using conservative therapy or, if that fails, then surgery. Despite the common occurrence of SUI, there have been few advances in our understanding of its cause in the past 40 years. Most of the many surgical procedures for alleviating SUI involve the principle of improving bladder neck support (Colombo et al., 1994; Bergman & Elia, 1995). Treatment selection based on specific anatomic abnormalities has awaited identification, in each case, of the muscular, neural and/or connective tissues involved.

Understanding how the pelvic floor structure/function relationships provide bladder neck support can help guide treatment selection and effect. For example if, while giving vaginal birth, a woman sustains a partial tear of a portion of her pelvic muscles that influence her continence, then pelvic muscle exercises may be effective.

On the other hand, if portions of those muscles are irretrievably lost, for example due to complete and permanent denervation, then no amount of exercising will restore them; pelvic muscle exercises may well lead to agonist muscle hypertrophy, but whether or not this will restore continence will depend upon whether the agonist muscles can compensate for the lost muscle function.

This chapter reviews the functional anatomy of the pelvic floor structures and the effects of age on urethral support and the urethral sphincter, and attempts to clarify what is known about the different structures that influence stress continence. This mechanistic approach should help guide research into pathophysiology, treatment selection and prevention of SUI. In addition, we also review the structures that resist genital prolapse because vaginal delivery confers a 4- to 11-fold increase in risk of developing pelvic organ prolapse (Mant et al., 1997).

How is Urinary Continence Maintained?

Urethral closure pressure must be greater than bladder pressure, both at rest and during increases in abdominal pressure, to retain urine in the bladder and prevent leakage. The resting tone of the urethral muscles maintains a favorable pressure relative to the bladder when urethral pressure exceeds bladder pressure. The primary factor that determines continence is the maximum urethral closure pressure developed by the urethral sphincter (DeLancey et al., 2008, 2010).

- Redrawn from DeLancey 1994, with permission of C V Mosby Company, St Louis.

- DeLancey

During activities such as coughing, when bladder pressure increases several times higher than urethral pressure, a dynamic process increases urethral closure pressure to enhance urethral closure and maintain continence (Enhörning 1961). Both the magnitude of the resting closure pressure in the urethra and the increase in abdominal pressure generated during a cough determine the pressure at which leakage of urine occurs (Kim et al., 1997).

Although analysis of the degree of resting closure pressure and pressure transmission provides useful theoretical insights, it does not show how specific injuries to individual component structures affect the passive or active aspects of urethral closure. A detailed examination of the sphincteric closure and the urethral support subsystems (Fig. 3.1) is required to understand these relationships.

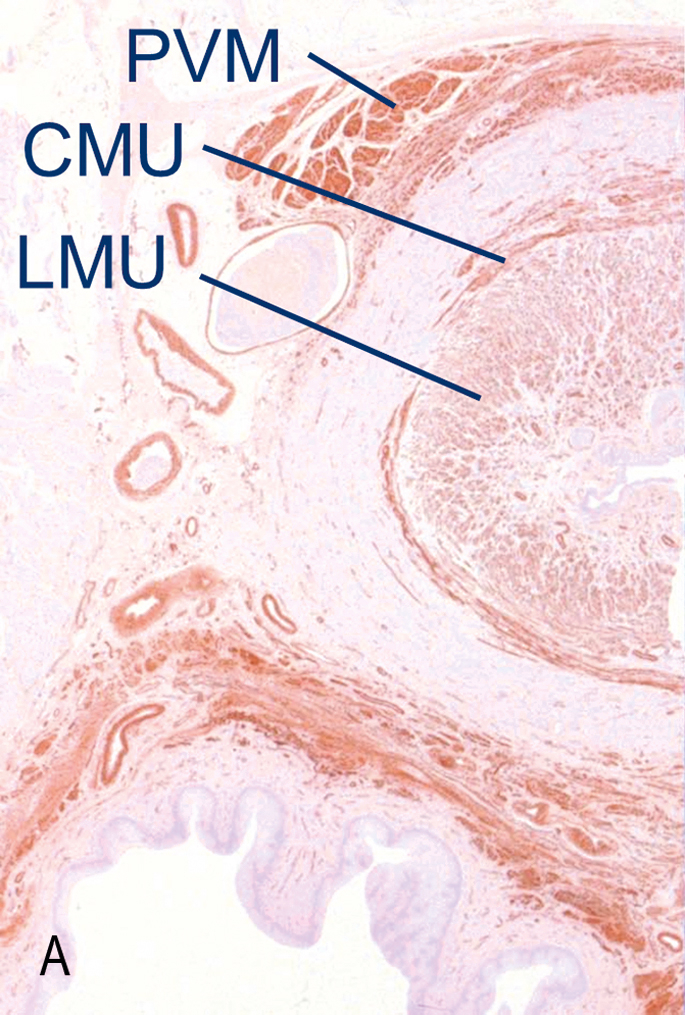

The dominant element in the urethral sphincter is the striated urogenital sphincter muscle, which contains a striated muscle in a circular configuration in the middle of the urethra and strap-like muscles distally. In its sphincteric portion, the urogenital sphincter muscle surrounds two orthogonally-arranged smooth muscle layers and a vascular plexus that helps to maintain closure of the urethral lumen.

The Urinary Sphincteric Closure System

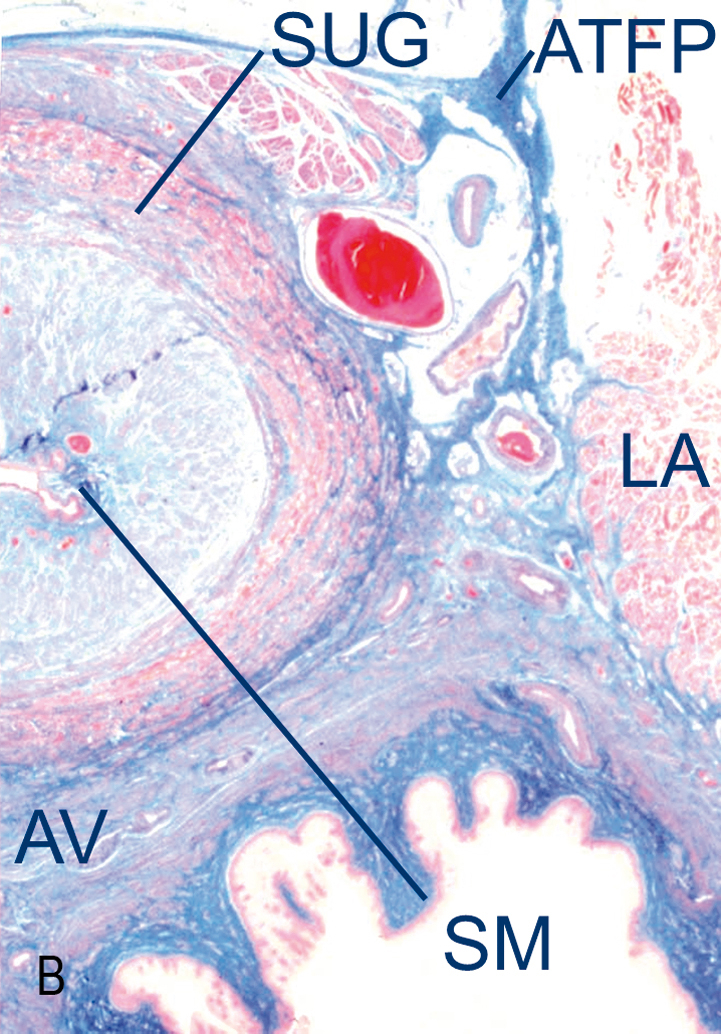

Sphincteric closure of the urethra is normally provided by the urethral striated muscles, the urethral smooth muscle and the vascular elements within the submucosa (Figs 3.2 and 3.3) (Strohbehn et al., 1996; Strohbehn & DeLancey, 1997). Each is believed to contribute equally to resting urethral closure pressure (Rud et al., 1980).

Anatomically, the urethra can be divided longitudinally into percentiles, with the internal urethral meatus representing point 0 and the external meatus representing the 100th percentile (Table 3.1). The urethra passes through the wall of the bladder at the level of the vesical neck where the detrusor muscle fibres extend below the internal urethra meatus to as far as the 15th percentile.

The striated urethral sphincter muscle begins at the termination of the detrusor fibres and extends to the 64th percentile. It is circular in configuration and completely surrounds the smooth muscle of the urethral wall.

Starting at the 54th percentile, the striated muscles of the urogenital diaphragm, the compressor urethrae and the urethrovaginal sphincter can be seen. They are continuous with the striated urethral sphincter and extend to the 76th percentile. Their fibre direction is no longer circular. The fibres of the compressor urethrae pass over the urethra to insert into the urogenital diaphragm near the pubic ramus.

The urethrovaginal sphincter surrounds both the urethra and the vagina (Fig. 3.4). The distal terminus of the urethra runs adjacent to, but does not connect with, the bulbocavernosus muscles (DeLancey 1986).

Functionally, the urethral muscles maintain continence in various ways. The U-shaped loop of the detrusor smooth muscle surrounds the proximal urethra, favoring its closure by constricting the lumen.

The striated urethral sphincter is composed mainly of type 1 (slow-twitch) fibres, which are well suited to maintaining constant tone as well as allowing voluntary increases in tone to provide additional continence protection (Gosling et al., 1981). Distally, the recruitment of the striated muscle of the urethrovaginal sphincter and the compressor urethrae compress the lumen.

The smooth muscle of the urethra may also play a role in determining stress continence. The lumen is surrounded by a prominent vascular plexus that is believed to contribute to continence by forming a watertight seal via coaptation of the mucosal surfaces. Surrounding this plexus is the inner longitudinal smooth muscle layer. This in turn is surrounded by a circular layer, which itself lies inside the outer layer of striated muscle.

The smooth muscle layers are present throughout the upper four-fifths of the urethra. The circular configuration of the smooth muscle and outer striated muscle layers suggests that the contraction of these layers has a role in constricting the lumen. The mechanical role of the inner longitudinal smooth muscle layer is presently unresolved. Contraction of this longitudinal layer may help to open the lumen to initiate micturition rather than to constrict it.

Clinical Correlates of Urethral Anatomy and Effects of Aging

There are several important clinical correlates of urethral muscular anatomy. Perhaps the most important is that SUI is caused by problems with the urethral sphincter mechanism as well as with urethral support. Although this is a relatively new concept, the supporting scientific evidence is strong.

The usual argument for urethral support playing an important role in SUI is that urethral support operations cure SUI without changing urethral function. Unfortunately, this logic is just as flawed as suggesting that obesity is caused by an enlarged stomach because gastric stapling surgery, which makes the stomach smaller, is effective in alleviating obesity. The fact that urethral support operations cure SUI does not implicate urethral hypermobility as the cause of SUI.

Most studies have shown not only that there is substantial variation in resting urethral closure pressures in normal women compared with those with SUI, but also that the severity of SUI correlates quite well with resting urethral closure pressure.

Loss of urethral closure pressure probably results from age-related deterioration of the urethral musculature as well as from neurologic injury (Hilton & Stanton, 1983; Snooks et al., 1986; Smith et al., 1989a, 1989b). For example, the total number of striated muscle fibres within the ventral wall of the urethra has been found to decrease seven-fold as women progress from 15 to 80 years of age, with an average loss of 2% per year (Fig. 3.5) (Perucchini et al., 2002a).

Because the mean fibre diameter does not change significantly with age, the cross-sectional area of striated muscle in the ventral wall decreases significantly with age; however, nulliparous women seemed relatively protected (Perucchini et al., 2002b). This 65% age-related loss in the number of striated muscle fibres found in vitro is consistent with the 54% age-related loss in closure pressure found in vivo by Rud et al., 1980, suggesting that it may be a contributing factor. However, prospective studies are needed to directly correlate the loss in the number of striated muscle fibres with a loss in closure pressure in vivo.

It is noteworthy that in our in vitro study thinning of the striated muscle layers was particularly evident in the proximal vesical neck and along the dorsal wall of the urethra in older women (Perucchini et al., 2002b). The concomitant seven-fold age-related loss of nerve fibres in these same striated urogenital sphincters (Fig. 3.6) directly correlated with the loss in striated muscle fibres (Fig. 3.7) in the same tissues (Pandit et al., 2000); and the correlation supports the hypothesis of a neurogenic source for SUI and helps to explain why faulty innervation could affect continence.

We believe that the ability of pelvic floor exercise to compensate for this age-related loss in sphincter striated muscle may be limited under certain situations. Healthy striated muscle can increase its strength by about 30% after an intensive 8–12 weeks of progressive resistance training intervention (e.g. Skelton et al., 1995). For example, suppose an older woman had a maximum resting urethral closure pressure of 100 cmH2O when she was young but it is now 30 cmH2O due to loss of striated sphincter muscle fibres. If she successfully increases her urethral striated muscle strength by 30% through an exercise intervention and there is a one-to-one correspondence between urethral muscle strength and resting closure pressure, she will only be able to increase her resting closure pressure by 30%, from 30 cmH2O to 39 cmH2O, an increment less than one-tenth of the 100 cmH2O increase in intravesical pressure that occurs during a hard cough. It remains to be determined whether pelvic floor muscle exercise is as effective in alleviating SUI in women with low resting urethral pressures as it can be in women with higher resting pressures, especially for women participating in activities with large transient increases in abdominal pressure.

Urethral (And Anterior Vaginal Wall) Support System

Support of the urethra and vesical neck is determined by the endopelvic fascia of the anterior vaginal wall through their fascial connections to the arcus tendineus fascia pelvis and connection to the medial portion of the levator ani muscle.

It is our working hypothesis that both urethral constriction and urethral support contribute to continence. Active constriction of the urethral sphincter maintains urine in the bladder at rest. During increases in abdominal pressure, the vesical neck and urethra are compressed to a closed position when the raised abdominal pressure surrounding much of the urethra exceeds the fluid pressure within the urethral lumen (see Fig. 3.1). The stiffness of the supportive layer under the vesical neck provides a backstop against which abdominal pressure compresses the urethra. This anatomic division mirrors the two aspects of pelvic floor function relevant to SUI: urethral closure pressure at rest and the increase in urethral closure caused by the effect of abdominal pressure.

Support of the urethra and distal vaginal wall are inextricably linked. For much of its length the urethra is fused with the vaginal wall, and the structures that determine urethral position and distal anterior vaginal wall position are the same.

The anterior vaginal wall and urethral support system consists of all structures extrinsic to the urethra that provide a supportive layer on which the proximal urethra and mid-urethra rest (DeLancey 1994). The major components of this supportive structure are the vaginal wall, the endopelvic fascia, the arcus tendineus fasciae pelvis and the levator ani muscles (see Fig. 3.1).

The endopelvic fascia is a dense, fibrous connective tissue layer that surrounds the vagina and attaches it to each arcus tendineus fascia pelvis laterally. Each arcus tendineus fascia pelvis in turn is attached to the pubic bone ventrally and to the ischial spine dorsally.

The arcus tendineus fasciae pelvis are tensile structures located bilaterally on either side of the urethra and vagina. They act like the catenary-shaped cables of a suspension bridge and provide the support needed to suspend the urethra on the anterior vaginal wall. Although it is well defined as a fibrous band near its origin at the pubic bone, the arcus tendineus fascia pelvis becomes a broad aponeurotic structure as it passes dorsally to insert into the ischial spine. It therefore appears as a sheet of fascia as it fuses with the endopelvic fascia, where it merges with the levator ani muscles (see Fig. 3.1).

Levator Ani Muscles

The levator ani muscles also play a critical role in supporting the pelvic organs (Halban & Tandler, 1907; Berglas & Rubin, 1953; Porges et al., 1960). Not only has evidence of this been seen in magnetic resonance scans (Kirschner-Hermanns et al., 1993; Tunn et al., 1998) but histological evidence of muscle damage has been found (Koelbl et al., 1998) and linked to operative failure (Hanzal et al., 1993).

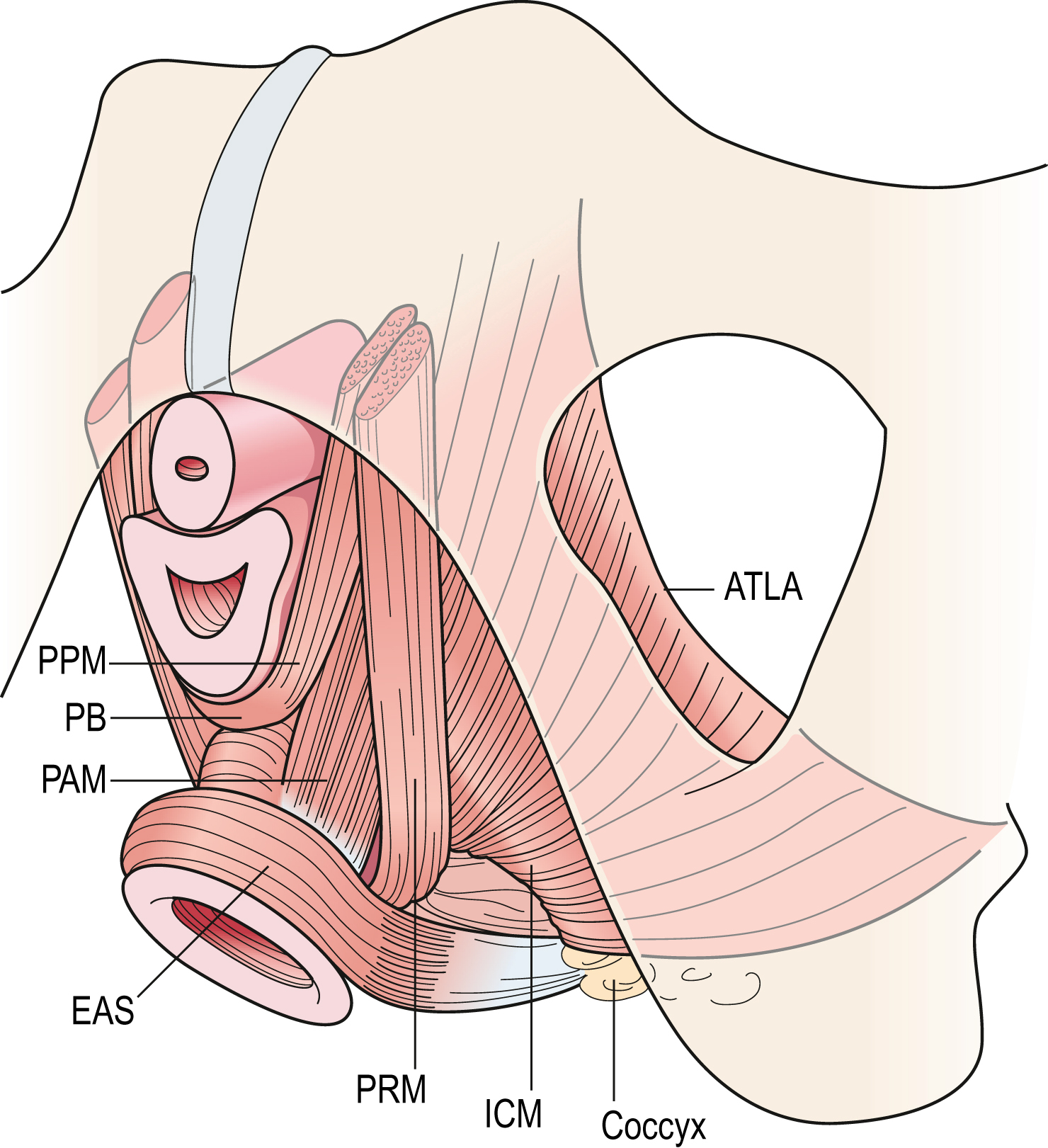

- • the first region is the iliococcygeal portion, which forms a relatively flat, horizontal shelf spanning the potential gap from one pelvic sidewall to the other;

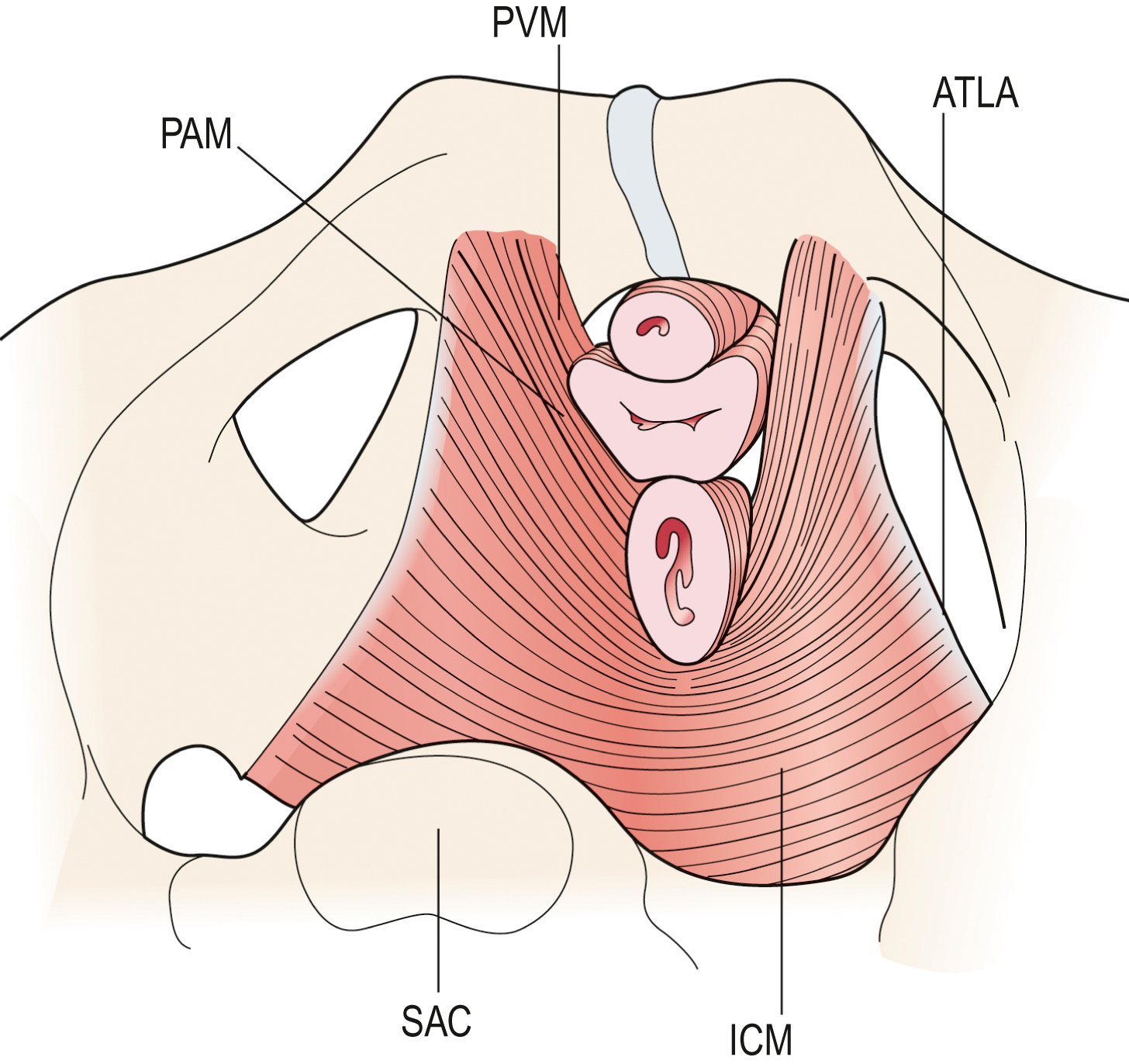

Fig. 3.8 Schematic view of the levator ani muscles from below after the vulvar structures and perineal membrane have been removed showing the arcus tendineus levator ani (ATLA); external anal sphincter (EAS); puboanal muscle (PAM); perineal body (PB) uniting the two ends of the puboperineal muscle (PPM); iliococcygeal muscle (ICM); puborectal muscle (PRM). Note that the urethra and vagina have been transected just above the hymenal ring. DeLancey - • the second portion is the pubovisceral muscle, which arises from the pubic bone on either side and attaches to the walls of the pelvic organs and perineal body;

- • the third region, the puborectal muscle, forms a sling around and behind the rectum just cephalad to the external anal sphincter.

The connective tissue covering on both superior and inferior surfaces are called the superior and inferior fasciae of the levator ani. When these muscles and their associated fasciae are considered together, the combined structures make up the pelvic diaphragm.

The opening within the levator ani muscle through which the urethra and vagina pass (and through which prolapse occurs), is called the urogenital hiatus of the levator ani. The rectum also passes through this opening, but because the levator ani attaches directly to the anus it is not included in the name of the hiatus. The hiatus, therefore, is supported ventrally (anteriorly) by the pubic bones and the levator ani muscles, and dorsally (posteriorly) by the perineal body and external anal sphincter.

The normal baseline activity of the levator ani muscle keeps the urogenital hiatus closed by compressing the vagina, urethra and rectum against the pubic bone, the pelvic floor and organs in a cephalic direction (Taverner 1959). This constant activity of the levator ani muscle is analogous to that in the postural muscles of the spine. This continuous contraction is also similar to the continuous activity of the external anal sphincter muscle, and closes the lumen of the vagina in a manner similar to that by which the anal sphincter closes the anus. This constant action eliminates any opening within the pelvic floor through which prolapse could occur.

A maximal voluntary contraction of the levator ani muscles causes the pubovisceral muscles and the puborectalis muscles to further compress the mid-urethra, distal vagina and rectum against the pubic bone distally and against abdominal hydrostatic pressure more proximally. It is this compressive force and pressure that one feels if one palpates a pelvic floor muscle contraction intravaginally. Contraction of the bulbocavernosus and the ventral fibres of the iliococcygeus will only marginally augment this compression force developed by the pubovisceral and puborectalis muscles because the former develops little force and the latter is located too far dorsally to have much effect intravaginally.

Finally, maximal contraction of the mid and dorsal iliococcygeus muscles elevates the central region of the posterior pelvic floor, but likely contributes little to a vaginal measurement of levator strength or pressure because these muscles do not act circumvaginally.

When injury to the levator ani occurs it is usually caused by vaginal birth (DeLancey et al., 2003). Biomechanical computer simulations suggest this injury most likely occurs when stretch and tension in the muscle nearest the pubic bone peak near the end of the second stage of labour (Jing et al., 2012). Injuries to the levator ani are associated with genital prolapse (DeLancey et al., 2007) and in the next section we shall discuss why.

Interactions Between the Pelvic Floor Muscles and the Endopelvic Fasciae

The levator ani muscles play an important role in protecting the pelvic connective tissues from excess load. Any connective tissue within the body may be stretched by subjecting it to a tensile force. Skin expanders used in plastic surgery stretch the dense and resistant dermis to extraordinary degrees, and flexibility exercises practised by dancers and athletes elongate leg ligaments. Both these observations underscore the adaptive nature of connective tissue when subjected to repeated tension over time.

If the ligaments and fasciae within the pelvis were subjected to continuous stress imposed on the pelvic floor by the great force of abdominal pressure, they would stretch. This stretching does not occur because the constant tonic activity of the pelvic floor muscles (Parks et al., 1962) closes the urogenital hiatus and carries the weight of the abdominal and pelvic organs, preventing constant strain on the ligaments and fasciae within the pelvis.

The interaction between the pelvic floor muscles and the supportive ligaments is critical to pelvic organ support. As long as the levator ani muscles function to properly maintain closure of the genital hiatus, the ligaments and fascial structures supporting the pelvic organs are under minimal tension. The fasciae simply act to stabilize the organs in their position above the levator ani muscles.

When the pelvic floor muscles relax or are damaged, the pelvic floor opens thereby placing the distal vagina between a zone of high abdominal pressure and the lower atmospheric pressure outside the body. The resulting pressure differential, which acts across the distal vaginal wall much like the wind on a sail, causes it to cup thereby increasing tension in the vaginal wall. This tension pulls the cervix caudally placing the uterine suspensory ligaments under tension and allowing the distal anterior vaginal wall to further cup (Chen et al., 2009). Although the ligaments can sustain these loads for short periods of time, if the pelvic floor muscles do not close the pelvic floor then the connective tissue will eventually fail, resulting in pelvic organ prolapse.

The support of the uterus has been likened to a ship in its berth floating on the water attached by ropes on either side to a dock (Paramore, 1918). The ship is analogous to the uterus, the ropes to the ligaments and the water to the supportive layer formed by the pelvic floor muscles. The ropes function to hold the ship (uterus) in the centre of its berth as it rests on the water (pelvic floor muscles). If, however, the water level falls far enough that the ropes are required to hold the ship without the supporting water, the ropes would break.

The analogous situation in the pelvic floor involves the pelvic floor muscles supporting the uterus and vagina, which are stabilized in position by the ligaments and fasciae. Once the pelvic floor musculature becomes damaged and no longer holds the organs in place, the supportive connective tissue is placed under stretch until it fails.

While the attachment of the levator ani muscles into the perineal body is important, it is uni- or bilateral damage to the pubic origin of this ventral part of the levator ani muscle during delivery that is one of the irreparable injuries to the pelvic floor. Recent magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) has vividly depicted these defects and it has been shown that up to 20% of primiparous women have a visible defect in the levator ani muscle on MRI (DeLancey et al., 2003), with a concomitant loss in levator muscle strength (DeLancey et al., 2007).

It is likely that this muscular damage is an important factor associated with recurrence of pelvic organ prolapse after initial surgical repair. Moreover, these defects were found to occur more frequently in those individuals complaining of SUI (DeLancey et al., 2003). An individual with muscles that do not function properly has a problem that is not surgically correctable.

Pelvic Floor Function Relevant to Stress Urinary Incontinence

Functionally, the urethral sphincter is primarily responsible for maintaining urinary continence, aided secondarily by interactions between the levator ani muscle and the endopelvic fascia which help maintain continence and provide pelvic support. Impairments usually become evident when the system is stressed.

One such stressor is a hard cough that, driven by a powerful contraction of the diaphragm and abdominal muscles, can cause a transient increase of 150 cmH2O, or more, in abdominal pressure. This transient pressure increase causes the proximal urethra to undergo a downward (caudodorsal) displacement of about 10 mm in the midsagittal plane that can be viewed on ultrasonography (Howard et al., 2000b). This displacement is evidence that the inferior abdominal contents are forced to move caudally during a cough.

Because the abdominal contents are essentially incompressible, the pelvic floor and/or the abdominal wall must stretch slightly under the transient increase in abdominal hydrostatic pressure, depending on the level of neural recruitment. The ventrocaudal motion of the bladder neck that is visible on ultrasonography indicates that it and the surrounding passive tissues have acquired momentum in that direction. The pelvic floor then needs to decelerate the momentum acquired by this mass of abdominal tissue.

The resulting inertial force causes a caudal-to-cranial pressure gradient in the abdominal contents, with the greatest pressure arising nearest the pelvic floor. While the downward momentum of the abdominal contents is being slowed by the resistance to stretch of the pelvic floor, the increased pressure compresses the proximal intra-abdominal portion of the urethra against the underlying supportive layer of the endopelvic fasciae, the vagina, and the levator ani muscles.

We can estimate the approximate resistance of the urethral support layer to this displacement. The ratio of the displacement of a structure in a given direction to a given applied pressure increase is known as the compliance of the structure.

If we divide 12.5 mm of downward displacement of the bladder neck (measured on ultrasonography) during a cough by the transient 150 cmH2O increase in abdominal pressure that causes it, the resulting ratio (12.5 mm divided by 150 cmH2O) yields an average compliance of 0.083 mm/cmH2O in healthy nullipara (Howard et al., 2000b). In other words, the cough displaces the healthy intact pelvic floor 1 mm for every 12 cmH2O increase in abdominal pressure. (Actually, soft tissue mechanics teaches us to expect ever smaller displacements as the abdominal pressure increments towards the maximum value.)

The increase in abdominal pressure acts transversely across the urethra, altering the stresses in the walls of the urethra so that the anterior wall is deformed toward the posterior wall, and the lateral walls are deformed towards one another, thereby helping to close the urethral lumen and prevent leakage due to the concomitant increase in intravesical pressure.

If pelvic floor exercises lead to pelvic floor muscle hypertrophy, then the resistance of the striated components of the urethral support layer can be expected to also increase. This is because the longitudinal stiffness and damping of an active muscle are linearly proportional to the tension developed in the muscle (e.g. Blandpied & Smidt, 1993); for the same muscle tone, the hypertrophied muscle contains more cross-bridges in the strongly-bound state (across the cross-sectional area of the muscle) and these provide greater resistance to stretch of the active muscle.

If there are breaks in the continuity of the endopelvic fascia (Richardson et al., 1981) or if the levator ani muscle is damaged, the supportive layer under the urethra will be more compliant and will require a smaller pressure increment to displace a given distance.

Howard et al., (2000b) showed that compliance increased by nearly 50% in healthy primipara to 0.167 mm/cmH2O and increased even further in stress-incontinent primipara by an additional 40% to 0.263 mm/cmH2O. Thus, the supportive layer is considerably more compliant in these incontinent patients than in healthy women; it provides reduced resistance to deformation during transient increases in abdominal pressure so that closure of the urethral lumen cannot be ensured and SUI becomes possible.

An analogy that we have used previously is attempting to halt the flow of water through a garden hose by stepping on it (DeLancey, 1990). If the hose was lying on a noncompliant trampoline, stepping on it would change the stress in the wall of the hose pipe, leading to a deformation and flattening of the hose cross-sectional area, closure of the lumen and cessation of water flow, with little indentation or deflection of the trampoline. If, instead, the hose was resting on a very compliant trampoline, stepping on the hose would tend to accelerate the hose and underlying trampoline downward because the resistance to motion (or reaction force) is at first negligible, so little flattening of the hose occurs as the trampoline begins to stretch. While the hose and trampoline move downward together, water would flow unabated in the hose. As the resistance of the trampoline to downward movement increasingly decelerates the downward movement of the foot and hose, flow will begin to cease. Thus, an increase in compliance of the supporting tissues essentially delays the effect of abdominal pressure on the transverse closure of the urethral lumen, allowing leakage of urine during the delay.

Additionally, the constant tone maintained by the pelvic muscles relieves the tension placed on the endopelvic fascia. If the nerves to the levator ani muscle are damaged (such as during childbirth) (Allen et al., 1990), the denervated muscles would atrophy and leave the responsibility of pelvic organ support to the endopelvic fascia alone. Over time, these ligaments gradually stretch under the constant load and this viscoelastic behaviour leads to the development of prolapse.

There are several direct clinical applications for this information. The first concerns the types of damage that can occur to the urethral support system. An example is the paravaginal defect, which causes separation in the endopelvic fascia connecting the vagina to the pelvic sidewall and thereby increases the compliance of the fascial layer supporting the urethra. When this occurs, increases in abdominal pressure can no longer effectively compress the urethra against the supporting endopelvic fascia to close it during increases in abdominal pressure. When present, this paravaginal defect can be repaired surgically and normal anatomy can thus be restored.

Normal function of the urethral support system requires contraction of the levator ani muscle, which supports the urethra through the endopelvic fascia. During a cough, the levator ani muscle contracts simultaneously with the diaphragm and abdominal wall muscles to build abdominal pressure. This levator ani contraction helps to tense the suburethral fascial layer, as evidenced by decreased vesical neck motion on ultrasonographic evaluation (Miller et al., 2001), thereby enhancing urethral compression. It also protects the connective tissue from undue stresses. Using an instrumented speculum (Ashton-Miller et al., 2002), the strength of the levator ani muscle has been quantified under isometric conditions (Sampselle et al., 1998), the maximum levator force available to close the distal vagina has been shown to differ in the supine and standing postures (Morgan et al., 2005), and racial differences have been found in the levator muscle contractile properties (Howard et al., 2000a).

Striated muscle takes 35% longer to develop the same force in the elderly as in young adults, and its maximum force is also diminished by about 35% (Thelen et al., 1996a). These changes are due not to alterations in neural recruitment patterns, but rather to age-related changes in striated muscle contractility (Thelen et al., 1996b) due to the age-related loss of fast-twitch fibres (Claflin et al., 2011). Happily, and unlike that in the adjacent obturator internus muscle, the decrease in levator ani cross-sectional area or volume is not significant with older age (Morris et al., 2012), presumably due to the levator being comprised of slow-twitch muscle fibres. If the striated muscle of the levator ani becomes damaged or if its innervation is impaired, the muscle contraction will take even longer to develop the same force. This decrease in levator ani strength, in turn, is associated with decreased stiffness, because striated muscle strength and stiffness are directly and linearly correlated (Sinkjaer et al., 1988).

Alternatively, if the connection between the muscle and the fascia is broken (Klutke et al., 1990), then the normal mechanical function of the levator ani during a cough is lost. This phenomenon has important implications for clinical management. Recent evidence from MRI scans, reviewed in a blinded manner shows the levator ani can be damaged unilaterally or bilaterally in certain patients (DeLancey et al., 2003). This damage, which most often occurs in the pubovisceral muscle near its pubic enthesis (Kim et al., 2011), has been shown to be associated with vaginal birth (Miller et al., 2010). Injury to the levator ani may also be related to urethral sphincter dysfunction (Miller et al., 2004).

Urethrovesical Pressure Dynamics

The anatomical separation of sphincteric elements and supportive structures is mirrored in the functional separation of urethral closure pressure and pressure transmission. The relationship between resting urethral pressure, pressure transmission and the pressure needed to cause leakage of urine are central to understanding urinary continence. These relationships have been described in what we have called the ‘pressuregram’ (Kim et al., 1997). The constrictive effect of the urethral sphincter deforms the wall of the urethra so as to maintain urethral pressure above bladder pressure, and this pressure differential keeps urine in the bladder at rest. For example, if bladder pressure is 10 cmH2O while urethral pressure is 60 cmH2O, a closure pressure of 50 cmH2O prevents urine from moving from the bladder through the urethra (Table 3.2, Example 1).

Bladder pressure often increases by 200 cmH2O or more during a cough, and leakage of urine would occur unless urethral pressure also increases. The efficiency of this pressure transmission is expressed as a percentage. A pressure transmission of 100% means, for example, that during a 200 cmH2O increase in bladder pressure (from 10 cmH2O to 210 cmH2O), the urethral pressure would also increase by 200 cmH2O (from 60 to 260 cmH2O) (see Table 3.2, Example 1).

The pressure transmission is less than 100% for incontinent women. For example, abdominal pressure may increase by 200 cmH2O while urethral pressure may only increase by 140 cmH2O, for a pressure transmission of 70% (see Table 3.2, Example 2).

If a woman starts with a urethral pressure of 30 cmH2O, resting bladder pressure of 10 cmH2O and her pressure transmission is 70%, then with a cough pressure of 100 cmH2O her bladder pressure would increase to 110 cmH2O while urethral pressure would increase to just 100 cmH2O and leakage of urine would occur (see Table 3.2, Example 3).

In Table 3.2, Example 4 shows the same elements, but with a higher urethral closure pressure; and similarly, Example 5 shows what happens with a weaker cough.

According to this conceptual framework, resting pressure and pressure transmission are the two key continence variables. What factors determine these two phenomena? How are they altered to cause incontinence? Although the pressuregram concept is useful for understanding the role of resting pressure and pressure transmission, it has not been possible to reliably make these measurements because of the rapid movement of the urethra relative to the urodynamic transducer during a cough.

Clinical Implications of Levator Functional Anatomy

Pelvic muscle exercise has been shown to be effective in alleviating SUI in many, but not all, women (Bø & Talseth, 1996). Having a patient cough with a full bladder and measuring the amount of urine leakage is quite simple (Miller et al., 1998a). If the muscle is normally innervated and is sufficiently attached to the endopelvic fascia, and if by contracting her pelvic muscles before and during a cough a woman is able to decrease that leakage (Fig. 3.10) (Miller et al., 1998b), then simply learning when and how to use her pelvic muscles may be an effective therapy. If this is the case, then the challenge is for the subject to remember to use this skill during activities that transiently increase abdominal pressure.

If the pelvic floor muscle is denervated as a result of substantial nerve injury, then it may not be possible to rehabilitate the muscle sufficiently to make pelvic muscle exercise an effective strategy. In order to use the remaining innervated muscle, women need to be told when to contract the muscles to prevent leakage, and they need to learn to strengthen pelvic muscles.

A stronger muscle that is not activated during the time of a cough cannot prevent SUI. Therefore, teaching proper timing of pelvic floor muscles would seem logical as part of a behavioural intervention involving exercise. The efficacy of this intervention is currently being tested in a number of ongoing randomized controlled trials. In addition, if the muscle is completely detached from the fascial tissues, then despite its ability to contract, the contraction may no longer be effective in elevating the urethra or maintaining its position under stress.

Anatomy of the Posterior Vaginal Wall Support as it Applies to Rectocele

The posterior vaginal wall is supported by connections between the vagina, the bony pelvis and the levator ani muscles (Smith et al., 1989b). The lower one-third of the vagina is fused with the perineal body (Fig. 3.11), which is the attachment between the perineal membranes on either side. This connection prevents downward descent of the rectum in this region.

If the fibres that connect one side with the other rupture then the bowel may protrude downward resulting in a posterior vaginal wall prolapse (Fig. 3.12).

The midposterior vaginal wall is connected to the inside of the levator ani muscles by sheets of endopelvic fascia (Fig. 3.13). These connections prevent ventral movement of the vagina during increases in abdominal pressure. The medial most aspect of these paired sheets is referred to as the rectal pillars.

In the upper one-third of the vagina, the vaginal wall is connected laterally by the paracolpium. In this region there is a single attachment to the vagina, and a separate system for the anterior and posterior vaginal walls does not exist. Therefore when abdominal pressure forces the vaginal wall downward towards the introitus, attachments between the posterior vagina and the levator muscles prevent this downward movement.

The uppermost area of the posterior vagina is suspended, and descent of this area is usually associated with the clinical problem of uterine and/or apical prolapse. The lateral connections of the midvagina hold this portion of the vagina in place and prevent a midvaginal posterior prolapse (Fig. 3.14). The multiple connections of the perineal body to the levator muscles and the pelvic sidewall (Figs 3.15 and 3.16) prevent a low posterior prolapse from descending downward through the opening of the vagina (the urogenital hiatus and the levator ani muscles). Defects in the support at the level of the perineal body most frequently occur during vaginal delivery and are the most common type of posterior vaginal wall support problem.

Acknowledgement

Supported by Public Health Service grants R01 DK 47516 and 51405, P30 AG 08808 and P50 HD 44406.