chapter 30 Female Sexual Function and Dysfunction

Urologists are well versed in the diagnosis and treatment of male sexual dysfunction. However, what is less commonly recognized but demonstrated in several studies is that male erectile dysfunction negatively impacts female sexual function and sexual quality of life (Fisher et al, 2005; Rosen et al, 2007). It was not until recently that urologists actually began to consider female sexual function as relevant to their practice. Based on the National Health and Social Life Survey, sexual dysfunction is actually more prevalent in women (43%) than in men (31%). Other studies suggest female sexual dysfunction (FSD) affects 25% to 76% of women in the United States. In one study, 98% women seeking routine gynecologic care had sexual concerns (Nusbaum et al, 2000).

Despite the high prevalence of sexual problems among women, physicians and patients alike are hesitant to initiate conversations about female sexual health. In a study of 471 physicians, only 22% stated they always screen for FSD whereas 55% screen most of the time and 23% never or rarely screen their patients (Pauls et al, 2005). Physicians cited various reasons for their lack of screening for FSD, the most common being lack of time. The majority of respondents (69%) underestimated the prevalence of FSD in their patient population. Fifty percent believed that their training and ability to treat FSD was unsatisfactory. Bachmann (2006) conducted a similar survey among physicians and health care providers attending the annual meetings of four specialty societies. Of the 1946 participants 42% did not inquire about FSD, citing limitations in time and training, embarrassment, and the absence of effective treatments as obstacles to discussing FSD. Sixty percent of participants rated both their knowledge and comfort level with FSD as fair or poor, whereas 86% rated treatment options as fair or poor.

Over the past 5 years the urologic literature has shown that a significant number of women with female pelvic floor disorders also report FSD. The aim of this chapter is to characterize female sexual function and dysfunctions while making urologists aware of the magnitude of FSD and providing them with information to diagnose and treat FSD in patients suffering from urologic conditions.

Female Sexual Anatomy and Physiology

Genital Anatomy

The organs of the female reproductive tract are classically divided into the external and the internal genitalia. The external genital organs include the mons pubis, clitoris, urethral meatus, labia majora, labia minora, vestibule, Bartholin glands, and Skene glands. The internal genital organs are located in the true pelvis and include the vagina, uterus, cervix, oviducts, ovaries, and surrounding supporting structures.

The vulva is a collective term for the female external genitalia. The vulva consists of the mons pubis, labia majora, labia minora, hymen, clitoris, vestibule, urethra, Skene glands, Bartholin glands, and vestibular bulbs. The boundaries of the vulva extend from the mons pubis anteriorly to the rectum posteriorly and laterally to the genitocrural folds.

The labia majora are two large, longitudinal, cutaneous folds of adipose and fibrous tissue that extend from the mons pubis to the posterior fourchette. The skin of the outer convex surface of the labia majora is pigmented and covered with hair follicles. The inner surface does not have hair follicles but has many sebaceous glands. Histologically the labia majora have both sweat and sebaceous glands. The labia majora are homologous to the scrotum in the male. The labia minora, which are homologous to the penile urethra, are two smaller folds located between the labia majora and the vaginal orifice. Anteriorly they divide at the clitoris to form the prepuce superiorly and the frenulum of the clitoris inferiorly. Histologically they are composed of dense connective tissue with erectile tissue and elastic fibers rather than adipose tissue. The skin of the labia minora is less cornified and has many sebaceous glands but no hair follicles or sweat glands (Katz et al, 2007). The labia minora surround a space called the vestibule, into which the orifices of the urethra, vagina, and Bartholin glands open.

Bartholin glands are vulvovaginal glands located on the posterolateral aspect of the vaginal orifice at the 4- and 8-o’clock positions. Bartholin ducts open into the groove between the hymen and the labia minora and are homologous to Cowper glands in the male.

Skene glands, or paraurethral glands, are tubular glands adjacent to the distal urethra. Skene ducts run parallel to the long axis of the urethra for approximately 1 cm before opening into the distal urethra (Katz et al, 2007). Skene glands are homologous to the prostate in the male.

Lying anteriorly to the urethra is the clitoris. The average length of the clitoris is 1.5 to 2 cm. The clitoris consists of the glans, the body, and two crura, which attach to the periosteum of the symphysis pubis. The glans is the visible external portion of the clitoris. The clitoral body has two cylindrical corpora cavernosa composed of thin-walled, vascular channels that function as erectile tissue. The clitoris is the female homologue of the penis in the male.

Deep to the labia, immediately below the bulbocavernous muscle, are two erectile bodies called the vestibular bulbs. Each bulb is attached to the inferior surface of the perineal membrane and covered by the bulbocavernosal muscle. During sexual arousal the bulbs become engorged, thereby narrowing the vaginal opening.

Central and Peripheral Nervous System

The innervation of the internal genitalia is primarily by the autonomic nervous system. The sympathetic portion of the autonomic nervous system originates in the thoracic and lumbar portions of the spinal cord, and sympathetic ganglia are located adjacent to the central nervous system. In contrast, the parasympathetic portion originates in cranial nerves and the middle three sacral segments of the cord and the ganglia are located near the visceral organs. As a broad generalization, sympathetic fibers in the female pelvis produce muscular contractions and vasoconstriction whereas parasympathetic fibers cause the opposite effect on muscles and vasodilation.

The pudendal nerve and its branches supply the majority of both motor and sensory fibers to the muscles and skin of the vulvar region. The pudendal nerve arises from the second, third, and fourth sacral roots. As the pudendal nerve reaches the urogenital diaphragm it divides into three branches: the inferior hemorrhoidal, the deep perineal, and the superficial perineal. The dorsal nerve of the clitoris is a terminal branch of the deep perineal nerve.

The skin of the anus, clitoris, and medial and inferior aspects of the vulva is supplied primarily by distal branches of the pudendal nerve. The vulvar region receives additional sensory fibers from three nerves. The anterior branch of the ilioinguinal nerve sends fibers to the mons pubis and the upper part of the labia majora. The genital femoral nerve supplies fibers to the labia majora, and the posterior femoral cutaneous nerve supplies fibers to the inferoposterior aspects of the vulva.

The female sexual response is mediated primarily via spinal cord reflexes that are under descending control from the brainstem. The nucleus paragigantocellaris, which projects directly to the pelvic efferent neurons and interneurons in the lumbosacral spinal cord, is believed to play a role in female orgasm (Meston, 2000; Meston and Frohlich, 2000). The pelvic efferent neurons and interneurons in the lumbosacral spinal cord contain the neurotransmitter serotonin (Walsh et al, 2002). Serotonin applied to the spinal cord inhibits spinal sexual reflexes and may explain selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI)-induced anorgasmia (Meston, 2000). The raphe nuclei and pallidus, the magnus and parapyramidal region, and the locus ceruleus all project to the lumbosacral spinal cord and are believed to play a role in sexual function with the periaqueductal gray area acting as a relay center for sexual stimuli (Meston, 2000; Meston and Frohlich, 2000).

In males the hypothalamic medial preoptic area, which has widespread connections to the limbic system and brainstem, functions in the ability to recognize a sexual partner. In female animals, lesions to this area increase not only lordosis but also avoidance (Meston, 2000). During orgasm and arousal oxytocin is released from neurons in the paraventricular nucleus of the hypothalamus.

c-FOS staining during copulatory testing in animals has identified the medial amygdala and the red nucleus of the stria terminalis of the forebrain as playing a role in female sexual function. Stimulation of these areas results in subjective pleasurable responses in both males and females.

More recently functional magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) studies have been used to identify specific patterns of brain activation in the female sexual response. A study by Park and coworkers (2001) reported significant activation of the inferior frontal lobe, cingulate gyrus, insula, hypothalamus, caudate nucleus, globus pallidus, and inferior temporal lobe in women watching erotic films. In another study Jeong and associates (2005) compared brain activation in premenopausal and postmenopausal women watching erotic videos. Premenopausal women were found to have greater activity in whole brain and limbic, temporal, and parietal lobes whereas postmenopausal had greater activation in the superior frontal gyrus. A study by Arnow and associates (2009) compared functional MR images after erotic videos in women with and without a history of hypoactive sexual desire disorder (HSDD) and reported significantly greater activity in the entorhinal cortex in women with no history of sexual dysfunction and higher activation in the medial frontal gyrus and putamen in women with HSDD. These findings suggest that women with HSDD have a shift in attentional focus from erotic cues to a self-monitoring of sexual response and performance concerns, underscoring the neural correlates of heightened self-focus that clinically characterizes women with HSDD (Arnow et al, 2009).

Endocrine Factors

Estrogen and Progesterone

Traditionally three sex steroids have been implicated in female sexual behavior: estrogens, progestins, and androgens. In premenopausal woman, with normal ovulation, estrogen and progesterone levels are maintained until menopause. In premenopausal women the primary source of estradiol production is from the ovaries, under the control of follicle-stimulating hormone and inhibin produced by the pituitary gland, with less contributed from the adrenal gland and ovarian androgen precursors (Simpson, 2000; Davis et al, 2004; Giraldi et al, 2004). During the late follicular phase and in the luteal phase of the menstrual cycle there is a rise in estradiol. During the luteal phase there is also a rise in progesterone. Estradiol and progesterone levels fall abruptly at the time of menopause when ovulation ceases (Simpson, 2000; Davis et al, 2004; Giraldi et al, 2004).

Recent research suggests that estrogen and progesterone have little direct influence on female desire. Schreiner-Engel and coworkers (1989) found no significant difference in the estrogen levels of women with and without clinically diagnosed HSDD. Numerous studies have also shown no change in sexual desire with the administration of exogenous estrogen therapy alone in women (Furuhjelm et al, 1984; Nathorst-Boos et al, 1993a, 1993b). However, administration of both estrogen and androgen in natural and surgically menopausal woman has been shown to restore normal levels of sexual desire (Sherwin and Gelfand, 1985a). Although lack of estrogen may not directly impair female arousal and desire, it can indirectly impair sexual function by decreasing vasocongestion and lubrication and vaginal epithelial atrophy. Because estrogen plays a role in the regulation of vaginal and nitric oxide synthase expression, both naturally and surgically induced menopause result in decreased vaginal and nitric oxide synthase expression, resulting in apoptosis of the vaginal wall, smooth muscle, and epithelium. Treatment with estrogen therapy increases nitric oxide synthase expression, restores vaginal lubrication, and decreases dyspareunia, resulting in improved female sexual satisfaction.

In general, progestins do not have a direct impact on female sexual function. Although oral contraceptives that increase progesterone levels have been associated with decreased sexual desire and interest, treatment with progesterone alone has not been shown to improve sexual desire in either premenopausal or menopausal women (Persky, 1976; Schreiner-Engel et al, 1981; Leiblum et al, 1983; Sherwin and Gelfand, 1985b). Indirectly, progesterone may affect female sexual behavior by increasing depressive moods. It is believed that progesterone and estradiol compete for receptors in the central nervous system, and higher ratios of progesterone to estradiol correlate with unpleasant feelings and depressive moods (Persky et al, 1982).

Testosterone

Premenopausal women also produce 0.3 mg of testosterone daily. Unlike in men, 50% of testosterone production in women comes directly from the ovaries and the adrenal glands, with the remaining 50% produced by testosterone precursors such as androstenedione and dehydroepiandrosterone (DHEA) in peripheral tissues (Walsh et al, 2002). Only 2% of the total testosterone is free, whereas 98% is bound to albumin or sex hormone–binding globulin (SHBG). Fluctuations in SHBG alter the bioavailability of free testosterone. The administration of exogenous estrogens, such as oral contraceptives, increases hepatically synthesized SHBG, thereby reducing the bioavailability of free testosterone. Oral contraceptives also diminish follicle-stimulating hormone and luteinizing hormone levels, thereby suppressing ovulation and inhibiting androgen production. The combination of these two mechanisms may lead to very low circulating levels of free and bioavailable testosterone. Several studies have documented the negative effects of oral contraceptives on sexual function, including diminished sexual interest and arousal, suppression of female-initiated sexual activity, and decreased frequency of sexual intercourse and sexual enjoyment (Basson et al, 2004; Davis et al, 2004; Nappi et al, 2005). In premenopausal women with regular menstrual cycles, testosterone and androstenedione rise in the late follicular and luteal phases (Vierhapper et al, 1997). In premenopausal women there is also a diurnal variation in testosterone, with levels peaking in the morning (Vierhapper et al, 1997).

Unlike estrogen and progesterone levels, which fall abruptly with menopause, testosterone levels diminish gradually throughout life. Between the ages of 30 and 60, total and free testosterone levels decrease by 50% (Basson, 2008). In addition, adrenal precursors, DHEA and DHEA sulfate, decrease with increasing age (Baulieu, 1996; Baulieu et al, 2000). Decreased androgen levels associated with aging have been associated with decreased libido, arousal, orgasm, and genital sensations.

In addition to aging there are several clinical conditions in premenopausal women that are associated with low testosterone levels. Hyperprolactinemia and adrenal insufficiency can cause hypogonadotropic hypogonadism and loss of libido. Cushing disease or endogenous or exogenous glucocorticosteroid excess leads to adrenal suppression and androgen insufficiency and indirectly inhibits sexual function. Symptoms of androgen insufficiency include diminished sense of well-being or dysphoria; unexplained fatigue; decreased libido, sexual receptivity, and pleasure; and vasomotor instability or decreased vaginal lubrication despite adequate estrogen treatment. Bone loss, decreased muscle strength, and changes in memory or cognitive function are also possible as a result of diminished androgen production.

In studies of both naturally and surgically menopausal women the administration of testosterone alone, without estrogen replacement therapy, has been shown to improve desire, arousal, and sexual fantasies (Leiblum et al, 1983; McCoy and Davidson, 1985; Sherwin and Gelfand, 1985a). However, the effect of relationship between testosterone levels and desire in premenopausal women is less well defined. Several studies have failed to find differences in testosterone levels in premenopausal women with and without HSDD (Stuart et al, 1987; Schreiner-Engel et al, 1989). New data suggest that testosterone is beneficial in premenopausal women with HSDD who have low circulating testosterone levels (Schwenkhagen and Studd, 2009). Women placed on testosterone supplementation must be counseled regarding the potential risks and side effects of therapy, which include acne, hirsutism, male pattern baldness, clitoral hypertrophy, and increased triglyceride levels.

Physiology of Female Sexual Response Cycle

Although detailed writings of female anatomy date back to medieval times it was not until the 1900s that female sexuality and the physiology of the female sexual response cycle were described. Prior to 1900 female sexuality was demonized and deemed inappropriate unless procreatory or tied to pleasuring one’s husband. It was also widely believed that mental diseases in females resulted from abnormalities or excitation of the female external genitalia. It was not until 1953 when Arthur Kinsey published the controversial Sexual Behaviour in the Human Female, the first book to candidly report on female orgasm, masturbation, premarital sex, and infidelity, that the many myths surrounding female sexuality were dispelled.

Masters and Johnson were the first to study and report on sexual function and dysfunction. Published in 1966, the Human Sexual Response described the male and female sexual response cycle as four linear, successive phases: excitement, plateau, orgasm, and resolution. In females, the excitement phase begins with engorgement of the vaginal mucosa, thickening of the vaginal walls, and transudation of fluid into the vagina. There is engorgement of labia, clitoris, and vagina, with a resultant increase in vaginal and clitoral length. The breast become slightly enlarged from engorgement and the areolae become erect. Muscular tension, heart rate, and blood pressure rise slightly. In the plateau phase the labia become more engorged, the clitoris retracts, the outer one third of the vagina becomes more congested and narrow while the inner two thirds expand, and pelvic floor muscle tension builds. Orgasm is characterized by rhythmic contractions of levator ani, vagina, and uterus with massive release of muscular tension. During the resolution phase there is gradual diminishing of sexual muscular tension and detumescence of the labia, clitoris, and vagina.

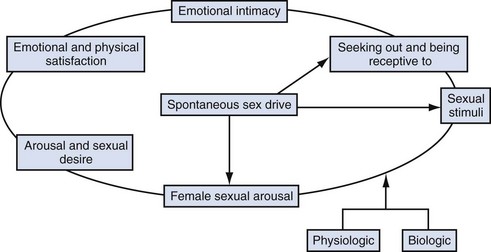

In response to much criticism, Basson, in 2000, described a more contemporary nonlinear model of female sexual response, integrating emotional intimacy, sexual stimuli, and relationship satisfaction (Fig. 30–1). This model recognizes that female sexual functioning is more complex and is less linear than male sexual functioning. It also emphasizes that many women initially begin a sexual encounter from a point of sexual neutrality, with the decision to be sexual stemming from the conscious need for emotional closeness or as a result of seduction from a partner. As demonstrated by the model, arousal stems from intimacy and seduction and often precedes desire. This model emphasizes that women have many reasons for engaging in sexual activity other than spontaneous sexual drive. Sexual neutrality or being receptive to, rather than initiating sexual activity, is considered a normal variation of female sexual functioning.

Classification and Epidemiology

Unlike male erectile dysfunction, female sexual disorders are more difficult to assess, diagnose, and treat. One of the initial barriers in the field of FSD was the lack of consensus of the definitions and criteria of these disorders. In 1998 the American Foundation of Urologic Disease Consensus convened to create a classification system and common terminology. It was at this conference that FSD was divided into four categories: sexual desire disorders, sexual arousal disorders, orgasmic disorders, and sexual pain disorders. In 2000 the panel reconvened and changed the classification schema to add “causing personal distress” as a criterion for diagnosis (Basson et al, 2000). This distinction is important because many studies on the prevalence of FSD have not qualified if the sexual symptoms reported caused “personal distress.” In 2004 the Second International Consensus of Sexual Medicine, consisting of over 200 multidisciplinary experts from 60 countries, convened and revised the definitions for FSD (Table 30–1).

Table 30–1 Revised Definitions for Female Sexual Dysfunction from the Second International Consensus of Sexual Medicine

Estimates on the prevalence of FSD varies greatly depending on the definitions, the assessment tool used, and the demographics of the population (age, race, educational and marital status). Hayes and colleagues (2008) compared the difference in the prevalence of the types of FSD among 356 women using four different instruments and found that the prevalence varied substantially depending on the instrument used, leading to the conclusion that the instrument chosen to assess for FSD significantly affects prevalence estimates. U.S. population census data suggest that roughly 10 million American women aged 50 to 74 years self report complaints of diminished lubrication, pain during intercourse, decreased arousal, and difficulty achieving orgasm (Salonia et al, 2004).

Several studies have shown that the prevalence of FSD varies depending on age, with women older than age 45 years at an increased risk of having FSD (Shifren et al, 2008). Among women aged 40 and older, the most common reported sexual problem was low desire (38.7% to 54%), difficulty with lubrication (21.5% to 39%), and inability to orgasm (20.5% to 34%) (Shifren et al, 2008).

Female pelvic floor disorders (incontinence, lower urinary tract symptoms, and pelvic organ prolapse) have also been shown to have a negative impact on female sexual function. Women with incontinence are up to three times more likely to experience decreased arousal, infrequent orgasms, and increased dyspareunia (Handa et al, 2004; Hansen, 2004; Laumann et al, 1999; Salonia et al, 2004). Several recent large studies have found a statistically significant improvement in sexual function scores among women who underwent successful surgery for incontinence and prolapse (Brubaker et al, 2009; Handa et al, 2007).

Key Points

Physiology

Diagnosis

The first step in diagnosing FSD is to identify women with the problem. Plouffe (1985) and colleagues found three simple questions as effective at identifying sexual problems as a lengthy interview (Kammerer-Doak and Rogers, 2008).

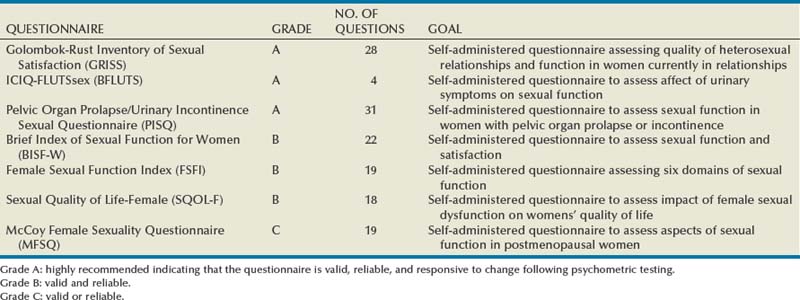

Validated questionnaires are also valuable tools to help identify the presence or absence of a sexual problem. A list of questionnaires recommended by the 4th International Consultation on Incontinence for evaluation of sexual function and health in women with urinary symptoms by grade is shown in Table 30–2. For additional information regarding commonly used and validated sexual function assessment tools the reader is referred to the Baylor College of Medicine website (http://femalesexualdysfunctiononline.org/resources/) (Kingsberg and Janata, 2007).

Table 30–2 Questionnaires Recommended by the 4th International Consultation on Incontinence for Evaluation of Sexual Function and Health in Women with Urinary Symptoms

After identifying patients at risk for FSD, the diagnosis of a problem relies on a careful clinical evaluation consisting of a detailed history, which includes sexual, medical, surgical, and psychosocial history; medications (including over-the-counter medications and supplements); physical examination; and validated questionnaires. At times blood tests and specialized laboratory tests may be appropriate. Although FSD can be purely physiologic, many cases are multifactorial owing to a combination of physiologic and psychological/social factors. It is advised that women with sexual health concerns undergo a separate and concomitant psychological interview by a psychologically focused health care professional (Basson, 2000; Basson et al, 2003, 2004).

History

If a problem is elicited a detailed and more thorough sexual history is warranted and should include past and present assessment of physiologic sexual responses (desire, arousal, and orgasm) to determine the following:

The medical history should include focused questions on the patient’s medical conditions, surgeries, and medication use. Current and medical history should focus on the following:

Table 30–3 Medications with Known Sexual Side Effects

See Tables 30-4 and 30-5 for the components of a complete patient history.

Table 30–4 Components of Comprehensive Sexual History

Table 30–5 Components of Comprehensive Medical and Surgical History

Physical Examination

The goals of the physical examination in women with sexual concerns are to confirm normal anatomy, assess for abnormalities, and reproduce and/or localize pain or tenderness (if tolerable). Given the intimate nature of the physical examination it is recommended that it be conducted in the presence of a female chaperone.

Although the physical examination of a woman with sexual concerns should focus on the genital examination, the examination should also include vital signs, particularly blood pressure, peripheral pulses, and a neurologic evaluation, including a sensory assessment. For women with neurologic disorders, anal and vaginal tone, voluntary tightening of the anus, and bulbocavernosal reflexes should be evaluated.

The genital examination should begin with visual inspection. Atrophy, abnormal discharges, signs of vaginitis, vulvar skin abnormalities, Bartholin or Skene gland cysts, urethral diverticuli, and signs of former episiotomy scars should be noted. The clitoris should be exposed to inspect for adhesions.

The second portion of the physical examination is palpation. The levator ani muscles should be palpated to assess for vaginismus and levator ani myalgia. A bimanual examination should be done to assess for motion tenderness, adnexal masses, endometriosis, and fibroids. Finally, a speculum examination should be performed to evaluate for pelvic organ prolapse. Table 30–6 is a list of physical examination findings that may impair female sexual function.

Table 30–6 Physical Examination Findings That May Impair Female Sexual Function

| EXAMINATION | CONDITION | SEXUAL SYMPTOMS |

|---|---|---|

| Inspection of Genitalia | ||

| Vaginal or labial atrophy | Low estrogen levels | Decreased arousal, dyspareunia |

| Sparse pubic hair | Low androgen levels | Decreased desire |

| Vulvar skin lesions | Lichen sclerosis, Candida, sexually transmitted infections | Dyspareunia |

| Vaginal discharge | Infection | Dyspareunia |

| Hypertonic muscle tone | Vaginismus, vestibulitis | Dyspareunia |

| Clitoral hood retraction | Adhesions | Anorgasmia |

| Vaginal wall cysts | Infected Bartholin or Skene gland | Dyspareunia |

| Manual Examination | ||

| Urethral fullness | Urethral diverticulum | Dyspareunia |

| Levator tenderness | Levator ani myalgia | Vaginismus, deep dyspareunia |

| Fixed retroverted uterus | Endometriosis, masses | Deep dyspareunia |

| Narrowed vaginal canal | Stricture/stenosis | Dyspareunia |

| Speculum Examination | ||

| Pelvic organ prolapse | Dyspareunia, decreased desire | |

| Stress incontinence | Vaginitis, decreased desire | |

Data from from Kingsberg, 2007, and Frank, 2008.

Laboratory Testing

Vaginal pH

Vaginal pH should be measured in women with vaginal discharges, odors, or atrophic vaginitis. Normal vaginal pH in women is 3.5 to 4.5. An acidic pH rules out a bacterial vaginitis other than candidiasis. A pH of 4.5 or more is suggestive of vaginitis, vaginosis, and/or atrophic vaginitis.

Wet Mount Testing

During the speculum portion of the examination samples should be taken of any abnormal discharge for wet mount and culture. Normal vaginal secretions are odorless and are not associated with the clinical complaint of itching or irritation.

Clue cells on wet mount are suggestive of bacterial vaginosis. Women diagnosed with bacterial vaginosis should be treated with oral or vaginal administration of metronidazole (Flagyl). Partners do not require treatment. If a patient is diagnosed with bacterial vaginosis it is important to also screen for gonorrhea and chlamydia.

The observation of an increased white blood cell count on a wet mount, more than 1 white blood cell per epithelial cell, may occur under the following conditions: vaginitis secondary to Trichomonas, yeast, and/or atrophy; cervicitis secondary to gonorrhea, chlamydia, and/or herpes; and upper genital/reproductive tract disease such as endometritis and/or pelvic inflammatory disease (Haefner, 1999; Anderson et al, 2004).

Blood Testing

Currently there are no recommended routine laboratory tests for women with sexual concerns. Therefore laboratory testing should be tailored to the results of the history and physical examination.

There are 10 sex steroids, including 7 androgens and 3 estrogens. Measurement of multiple sex steroids may be of clinical relevance to gain a better understanding of the hormonal integrity in a woman with sexual health concerns. Certain clinical scenarios might suggest checking estrogen (estradiol and estrone) and androgen values (DHEA sulfate, androstenedione, total testosterone, free testosterone, SHBG, and dihydrotestosterone). For example, measuring SHBG values might be of value in a premenopausal woman on oral contraceptive therapy with sexual complaints or measuring dihydrotestosterone levels in a woman who develops acne or alopecia after treatment with testosterone.

There are multiple concerns and limitations in determining serum hormone levels in women with sexual health concerns (Södergård et al, 1982; Zumoff et al, 1995; Shifren et al, 2000; Basson et al, 2004; Davis et al, 2005; Davison et al, 2005). First, although two studies have suggested normative ranges of androgens in women, the Endocrine Society’s Clinical Guidelines on Androgen Therapy in Women state that there are insufficient data to determine normal ranges of testosterone concentration values for women of different ages (Guay et al, 2004; Davison et al, 2005; Wierman et al, 2006). Second, the accuracy, precision, and reliability of the assays used to measure testosterone levels in women are not uniformly sensitive or reliable to accurately measure the low serum concentrations typically found in women (Wierman et al, 2006). However, newer testosterone assays, using mass spectroscopy, have shown promise in measuring testosterone more accurately and precisely (Rosner et al, 2007). Free testosterone is more important than total testosterone in sexual function. Only 1% to 2% of testosterone is found in its free biologically available form, with the remainder bound to either SHBG or albumin (Shufelt and Braunstein, 2002). The gold standard for measuring free testosterone is equilibrium dialysis. DHEA is usually measured in the sulfated form because it is easier to measure and does not vary during the menstrual cycle. Several studies have shown a consistent, age-related decline in DHEA sulfate levels (Zumoff et al, 1995; Munarriz et al, 2002; Basson et al, 2004). If low levels of DHEA sulfate are found, a morning cortisol level should be drawn to rule out adrenal insufficiency.

Specialized Testing

Vascular Testing

The female sexual response cycle is a complex interplay of physiologic, hypothalamic and emotive factors that relies on an intact neurovascular system. During sexual arousal, engorgement of the clitoral, labial, and vaginal erectile tissues occurs as a result of increased blood flow through the iliohypogastric-pudendal arterial bed. Just as atherosclerosis can cause impotence in men it can also cause sexual dysfunction in women. Diminished genital blood flow to the iliohypogastric-pudendal arterial bed secondary to atherosclerosis resulting in clitoral and vaginal vascular insufficiency syndromes can lead to decreased engorgement and arousal (Goldstein and Berman, 1998). In return, diminished blood flow and atherosclerotic changes lead to clitoral fibrosis, which interferes with normal smooth muscle relaxation and dilation to sexual stimulation (Tarcan et al, 1999).

Therefore Doppler ultrasonography, vaginal and clitoral photoplethysmography, and selective pudendal arteriography have all been used to assess the integrity of the female pelvic vascular supply. However, none of these measures has been validated or standardized. In addition, no normative data for control subjects exist for comparison. Therefore the clinical relevance of diagnostic hemodynamic investigations in women with sexual dysfunction has not yet been established (Basson et al, 2004).

Indications for vascular testing include (1) women with sexual arousal disorders who have exposure to multiple vascular risk factors, (2) women who have suffered pelvic fractures, and (3) women with sexual arousal disorders unresponsive to other therapies.

Vaginal photoplethysmography, the most commonly used noninvasive vascular testing in women with FSD, measures vaginal blood flow and vaginal pulse amplitude, thereby providing quantitative data on the extent of vaginal engorgement (Pasqualotto et al, 2005). However, this test has many drawbacks, including movement artifact (not suitable for use during stimulation or orgasm), the fact that it provides arbitrary rather than absolute units of measure, and that it provides no anatomic information (Verit et al, 2006).

Duplex Doppler ultrasonography before and after stimulation—visual, vibratory, or after topical alprostadil—has been used to record vaginal, clitoral, and labial blood flow during arousal. It also can be used to obtain changes in peak systolic velocity that occur in the vaginal, clitoral, cavernosal, and labial arteries during sexual arousal as well as the changes in clitoral and labial diameter associated with sexual stimulation. Drawbacks include paucity of “control” of duplex Doppler ultrasound values in women without sexual dysfunction and lack of standardized technique (Akkus et al, 1995; Khalife et al, 2000; Bechara et al, 2003; Munarriz et al, 2003; Pasqualotto et al, 2005).

MRI is one of the newest technologies being used to assess sexual function and arousal in women. MRI provides noninvasive, unparalleled multiplanar high-resolution imaging of the female pelvic floor without ionizing radiation. It can also be used to obtain dynamic quantitative physiologic information regarding changes in tissue volume, regional blood flow changes, and regional metabolite composition. MRI can be used to define the normal anatomic relationships of the female genital structures in vivo, providing a more accurate picture and a better understanding of the functional anatomy of women compared with cadaveric studies (Deliganis et al, 2002; Maravilla et al, 2002; Suh et al, 2003, 2004). During arousal, MR images show characteristic engorgement that is most pronounced in the clitoris, especially in the crura and body of the clitoris. The vaginal mucosa does not show any increase in size and signal intensity because it is only a few cell layers thick, below the limit of resolution of the MRI technique (Suh et al, 2003).

Functional brain imaging or functional MRI represents the ability to observe anatomic sites of brain activation in response to a specific task performed by a subject using rapid dynamic MRI. This technique is an experimental tool for exploring brain function associated with emotional attraction, feelings of pleasure, and even sites of activation associated with sexual arousal. There have been a number of studies applying functional MRI techniques to the evaluation of sexual arousal or emotional response in women. Brain regions that activated with sexual arousal were related with visual association areas (posterior temporo-occipital cortices, paralimbic areas, anterior cingulate cortex) (Komisaruk and Whipple, 2005).

As discussed earlier, a study by Arnow and associates (2009), comparing functional MRI in women with HSDD with women without sexual dysfunction found greater activation in the bilateral entorhinal cortex in women without FSD but greater activation of the medial frontal gyrus, right inferior frontal gyrus, and bilateral putamen in women with HSDD, suggesting that women with HSDD shift focus from erotic cues to self-monitoring of sexual response and performance concerns.

Treatment

The treatment of FSD is complicated owing to the many causes for these disorders. Optimal female sexual health requires physical, emotional, and mental well-being, which often makes medical treatment alone insufficient. Therefore, treatment requires a multimodal approach, often involving a multidisciplinary team of urologists and a mental health specialist with expertise in sexual medicine/sex therapy. Known anatomic, metabolic, and infectious causes should be corrected first. After correcting medical causes, treatment should begin with patient education.

Women should be educated about average sexual behaviors and frequencies (Kammerer-Doak and Rogers, 2008). Often women are led to believe they have a sexual dysfunction based on misinformation about what is “normal.” Behavioral changes such as changes in sexual practices and routine (e.g., initiating a sexual encounter in the morning instead of when exhausted at the end of a long day), smoking cessation, a healthy diet, and adequate rest and exercise should be discussed. Psychological referrals should be made to those providers who specialize in sexual disorders.

Once these issues have been addressed the use of pharmacotherapy should be discussed when appropriate. It is important to inform patients that to date the only U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA)–approved pharmacologic treatment of any female sexual disorder is that of conjugated estrogens (Premarin Vaginal Cream) for moderate to severe dyspareunia.

Hypoactive Sexual Desire Disorder

HSDD is defined as the absence or diminution of sexual interest or desire, absence of sexual thoughts or fantasies, and a lack of responsive desire. This is the most common type of female sexual disorder, and the cause can be physiologic, psychological, or both (Laumann et al, 1999; Nicolosi et al, 2004).

Although desire disorders are the most common sexual disorder they are challenging for physicians to treat. Desire is a complex concept composed of three discrete yet interrelated components: drive, cognition, motivation (Althof et al, 1992; Kingsberg and Althof, 2009). It is imperative for physicians to determine which component or components are causative because the treatments for impaired sex drive are different from those of impaired motivation.

Drive, the biologic component of desire, is based on neuroendocrine function and manifested by spontaneous sexual interest: sexual fantasies, dreams, and thoughts. Cognition is the woman’s sexual expectations, beliefs, and values. The third component of desire is motivation or the willingness to engage in sexual activity and is commonly related to psychosocial factors.

Treatment should begin with educating the patient that it is normal for drive to decline with increasing age, which reflects decreased androgen and testosterone production.

If desire is diminished secondary to psychosocial factors the patient should be referred to a sex therapist or psychologist to discuss lifestyle changes, stress management, or couples therapy.

If the cause appears to be related to drive, exogenous testosterone therapy with tibolone (a synthetic steroid with selective estrogenic, androgenic, and progesterogenic properties) may be an appropriate option, particularly for postmenopausal women. Centrally acting agents also are being investigated for the treatment of HSDD in both premenopausal and postmenopausal women.

Androgens for the Treatment of Desire Disorders

Despite testosterone being one of the most commonly prescribed drugs for desire disorders, its use is controversial and not FDA approved in women. Although testosterone is linked to sexual desire, studies have shown that low serum testosterone levels are not predictive of low desire nor do they correlate well with the likelihood of a therapeutic response (Davis et al, 2005).

In 2005 a Cochrane review of 23 trials with 1957 participants looking at the benefits of adding testosterone to hormonal therapy in perimenopausal and postmenopausal women concluded that although there was insufficient evidence in perimenopausal women, postmenopausal women did experience improved sexual function with the addition of testosterone to hormonal therapy (Somboonporn et al, 2005).

Several subsequent randomized controlled trials in postmenopausal women and surgically castrated women have shown that the addition of testosterone to hormonal therapy improved not only desire but also arousal and orgasm (Shifren et al, 2000, 2006; Braunstein et al, 2005; Davis et al, 2005).

The data regarding testosterone therapy in premenopausal women is lacking owing to a paucity of studies, but in two studies an improvement in sexual desire in premenopausal women with low libido treated with transdermal testosterone was suggested (Goldstat et al, 2003; Davis et al, 2005).

When prescribing testosterone therapy physicians must be aware of the potential adverse side effects and contraindications. Complications include acne, hirsutism, seborrhea, menstrual irregularities, virilization, hyperlipidemia, liver dysfunction, and male pattern baldness. Transdermal preparations may minimize adverse effects. Any patient on testosterone should be seen and have laboratory studies done routinely to avoid having levels reach superphysiologic levels.

Contraindications to testosterone therapy include androgenic alopecia, hirsutism, seborrhea or acne, polycystic ovary syndrome, liver dysfunction, and estrogen depletion (Basson et al, 2004).

For the androgen precursors DHEA and DHEA sulfate there are limited data regarding their effectiveness. One small retrospective study showed DHEA (50 mg/day) to improve desire, arousal, orgasm, and sexual satisfaction in both premenopausal and postmenopausal women (Munarriz et al, 2002).

Other Medication for the Treatment of Desire Disorders

Tibolone, a synthetic steroid, has been used in Europe for more than 20 years given its positive effects on sexual function. In one randomized control study of postmenopausal women with arousal and desires disorders, tibolone in combination with hormonal therapy was shown to significantly improve sexual function scores and increase clitoral circulation.

Arousal Disorders

Sexual arousal disorders can be treated, depending on the etiology, with counseling to change sexual practice patterns, medical therapy, or a combination of the two.

Estrogen replacement therapy has shown beneficial effects in women with postmenopausal arousal disorder by improving vaginal lubrication and blood flow.

Bupropion, an aminoketone antidepressant, has been shown to improve arousal in both premenopausal and postmenopausal women and both depressed and nondepressed women with arousal disorder (Modell et al, 2000; Segraves et al, 2001, 2004).

Alprostadil, a topically applied prostaglandin applied to the external genitalia, is currently under investigation for use in women given its beneficial effects on male arousal.

Arginmax, a nutritional supplement containing L-arginine, a precursor of nitric oxide, showed an increase in sexual arousal in both premenopausal and postmenopausal women in two small randomized control studies (Ito et al, 2001, 2006).

Zestra, botanical massage oil applied to the vulva, has been shown in one randomized control trial to significantly improve arousal in women with arousal disorders (Ferguson et al, 2003).

Phentolamine and yohimbine are α-androgenic antagonists that cause vasodilatation through smooth muscle relaxation. Although phentolamine has been shown to improve arousal and lubrication for menopausal women with arousal disorder, yohimbine failed to show any clinical improvement in arousal (Raina et al, 2007).

Sildenafil, a selective phosphodiesterase-5 inhibitor used to treat erectile dysfunction in men via smooth muscle relaxation, has also been used in women with arousal disorder with mixed results. Kaplan and colleagues (1999) reported no overall improvement in 33 postmenopausal women with arousal disorder treated with 50 mg of sildenafil despite improved vaginal lubrication and clitoral sensitivity. Basson and associates (2002) also reported no improvement in 781 premenopausal and postmenopausal women with arousal disorder with sildenafil. However, several studies have shown significant improvement in sexual arousal, orgasm, and overall satisfaction in women with arousal disorders treated with sildenafil (Caruso et al, 2001; Berman et al, 2003).

The EROS clitoral therapy device, an FDA-approved device that applies gentle suction to the clitoris, enhancing clitoral engorgement, has proven beneficial in women with arousal disorders (Wilson et al, 2001).

Orgasmic Disorders

Orgasmic disorders can be classified as primary or secondary. Primary orgasmic disorders are typically the result of sexual inexperience and are treated using cognitive behavioral therapy, directed masturbation, and sex education. Permission giving by the physician regarding sexual exploration and masturbation is hugely helpful to women with anorgasmia. Secondary anorgasmia, or acquired anorgasmia, is often the result of antidepressant medications. This can be treated by stopping the offending medication.

Dyspareunia and Vaginismus

The treatment of sexual pain disorders is often challenging, given the paucity of controlled trials as well as the multiple causes. Ideally, treatment should involve a multidisciplinary team that can address the physiologic, emotional, relational, and psychological factors. Pelvic floor physical therapy with biofeedback, pelvic floor electrical stimulation, perineal ultrasonography, and vaginal dilators have all been used with reported clinical benefit but without scientific evidence (Basson et al, 2004).

Pharmacotherapy for sexual pain disorders is routed in treating the underlying condition. Postmenopausal women with pain secondary to atrophic vaginitis should be treated with topical estrogen whereas women with vulvovaginitis should be treated with oral or transvaginal antifungal agents.

Tricyclic antidepressants, SSRIs, and corticosteroids have been used to treat vulvar vestibulitis, but data supporting their use are limited.

SSRI-Related Sexual Dysfunction

Selective phosphodiesterase-5 inhibitors have been used in therapy for SSRI-induced sexual function. In several studies, women with SSRI-induced sexual dysfunction reported significant improvements in overall sexual function and satisfaction on sildenafil (Nurnberg et al, 1999, 2008; Salerian et al, 2000; Basson et al, 2004). Some reports suggest that bupropion may be an effective antidote for SSRI-induced sexual dysfunction; however, the data on restoring normal sexual functioning in this patient population are mixed (Clayton et al, 2004; DeBattista et al, 2005).

Surgical Therapy

Sexual Pain Disorders

The role of surgery in the treatment of female sexual pain disorders should be considered only in patients who have failed conservative medical and psychological therapy.

Vulvar Vestibulectomy

Vulvar vestibulectomy has been used in women with refractory vulvar vestibulitis syndrome and in women with various conditions such as lichen sclerosis or posterior fourchette fissures that have destroyed the normal vulvar architecture. Since first described in 1981, the surgery has undergone several modifications and variations. A complete vulvar vestibulectomy involves anterior, posterior, and lateral vaginal mucosa with a posterior vaginal advancement flap. In a modified vulvar vestibulectomy, only the posterior vaginal mucosa is excised (Kehoe and Luesley, 1999).

It is imperative to map the painful vestibular areas preoperatively. With the patient under general anesthesia, the previously mapped areas are infiltrated with lidocaine and epinephrine (1 : 200,000 units) for hydrodissection. A No. 15 blade is then used to excise the vestibular mucosa. The defect is then closed using 3-0 or 4-0 Vicryl sutures. Attention should be paid to the location of the Bartholin gland, which should be avoided to prevent postoperative cyst formation (Kehoe and Luesley, 1999).

Postoperatively, patients should be instructed to avoid vaginal penetration and limit physical activity for a minimum of 4 weeks. At 4 weeks patients should begin a physical therapy regimen, which may include biofeedback and vaginal dilators.

In 2008 Landry and colleagues conducted a review of the treatment of vestibulodynia. Of the 38 studies reviewed only 5 were randomized controlled studies and the majority of the studies had several methodologic weaknesses, including absence of a control group, pretreatment pain evaluation, validated questionnaires assessing pain and sexual function, and standard surgical technique.

Yet based on these limited prospective studies and the randomized clinical trials, vestibulectomy was the most efficacious treatment to date, achieving a high rate of patient satisfaction and greater than 50% resolution of dyspareunia (Landry et al, 2008).

Female Pelvic Floor Disorders

Although female pelvic organ prolapse, incontinence, and overactive bladder have all been shown to have a negative impact on female sexual function, surgical restoration of normal anatomy with alleviation of symptoms does not consistently improve female sexual outcomes.

Key Points

Diagnosis and Treatment

Conclusion

Despite our increasing knowledge base, female sexual disorders still remain a challenge to physicians and patients alike. Much of this is based on both physician and patient avoidance of the topic. Sexual health is as important to the quality of lives of women as it is to men, and female patients expect that their physicians will address their sexual concerns. The goal of this chapter was to equip the urologist with the tools to screen, diagnose, and collaborate with a multidisciplinary team to adequately address the complexity of female sexual disorders.

Basson R, Althof S, Davis S, et al. Summary of the recommendations on sexual dysfunctions in women. J Sex Med. 2004;1(1):24-34.

Braunstein GD, Sundwall DA, Katz M, et al. Safety and efficacy of a testosterone patch for the treatment of hypoactive sexual desire disorder in surgically menopausal women: a randomized, placebo-controlled trial. Arch Intern Med. 2005;165(14):1582-1589.

Davis SR, Davison SL, Donath S, Bell RJ. Circulating androgen levels and self-reported sexual function in women. JAMA. 2005;294(1):91-96.

Guay A, Munarriz R, Jacobson J, et al. Serum androgen levels in healthy premenopausal women with and without sexual dysfunction. Part A. Serum androgen levels in women aged 20-49 years with no complaints of sexual dysfunction. Int J Impot Res. 2004;16(2):112-120.

Kammerer-Doak D, Rogers RG. Female sexual function and dysfunction. Obstet Gynecol Clin North Am. 2008;35(2):169-183. vii

Kingsberg S, Althof SE. Evaluation and treatment of female sexual disorders. Int Urogynecol J Pelvic Floor Dysfunct. 2009;20(Suppl. 1):S33-S43.

Laumann EO, Paik A, Rosen RC. The epidemiology of erectile dysfunction: results from the National Health and Social Life Survey. Int J Impot Res. 1999;11(Suppl. 1):S60-S64.

Nurnberg HG, Hensley PL, Heiman JR, et al. Sildenafil treatment of women with antidepressant-associated sexual dysfunction: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2008;300(4):395-404.

Nyirjesy P, Sobel JD. Advances in diagnosing vaginitis: development of a new algorithm. Curr Infect Dis Rep. 2005;7:458-462.

Rosner W, Auchus RJ, Azziz R, et al. Position statement: utility, limitations, and pitfalls in measuring testosterone: an endocrine society position statement. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2007;92(2):405-413.

Salonia A, Munarriz RM, Naspro R, et al. Women’s sexual dysfunction: a pathophysiological review. BJU Int. 2004;93:1156-1164.

Shifren JL, Davis SR, Moreau M, et al. Testosterone patch for the treatment of hypoactive sexual desire disorder in naturally menopausal women: results from the INTIMATE NM1 study. Menopause. 2006;13(5):770-779.

Somboonporn W, Davis S, Seif MW, Bell R. Testosterone for peri- and postmenopausal women. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2005;(4):CD004509.

Akkus E, Carrier S, Turzan C, et al. Duplex ultrasonography after prostaglandin E1 injection of the clitoris in a case of hyperreactio luteinalis. J Urol. 1995;153(4):1237-1238.

Althof SE, Turner LA, Levine SB, et al. Through the eyes of women: the sexual and psychological responses of women to their partner’s treatment with self-injection or external vacuum therapy. J Urol. 1992;147(4):1024-1027.

Anderson MR, Klink K, Cohrssen A. Evaluation of vaginal complaints. JAMA. 2004;291(11):1368-1379.

Arnow BA, Millheiser L, Garrett A, et al. Women with hypoactive sexual desire disorder compared to normal females: a functional magnetic resonance imaging study. Neuroscience. 2009;158(2):484-502.

Bachmann G. Female sexuality and sexual dysfunction: are we stuck on the learning curve? J Sex Med. 2006;3(4):639-645.

Basson R. Testosterone supplementation to improve women’s sexual satisfaction: complexities and unknowns. Ann Intern Med. 2008;148(8):620-621.

Basson R. The female sexual response: a different model. J Sex Marital Ther. 2000;26(1):51-65.

Basson R, Althof S, Davis S, et al. Summary of the recommendations on sexual dysfunctions in women. J Sex Med. 2004;1(1):24-34.

Basson R, Berman J, Burnett A, et al. Report of the international consensus development conference on female sexual dysfunction: definitions and classifications. J Urol. 2000;163(3):888-893.

Basson R, Leiblum S, Brotto L, et al. Definitions of women’s sexual dysfunction reconsidered: advocating expansion and revision. J Psychosom Obstet Gynaecol. 2003;24(4):221-229.

Basson R, McInnes R, Smith MD, et al. Efficacy and safety of sildenafil citrate in women with sexual dysfunction associated with female sexual arousal disorder. J Womens Health Gend Based Med. 2002;11(4):367-377.

Baulieu EE. Dehydroepiandrosterone (DHEA): a fountain of youth? J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1996;81(9):3147-3151.

Baulieu EE, Thomas G, Legrain S, et al. Dehydroepiandrosterone (DHEA), DHEA sulfate, and aging: contribution of the DHEAge Study to a sociobiomedical issue. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2000;97(8):4279-4284.

Bechara A, Bertolino MV, Casabé A, et al. Duplex Doppler ultrasound assessment of clitoral hemodynamics after topical administration of alprostadil in women with arousal and orgasmic disorders. J Sex Marital Ther, 29 Suppl. 1, 2003, 1-10.

Berman JR, Berman LA, Toler SM, et al. Safety and efficacy of sildenafil citrate for the treatment of female sexual arousal disorder: a double-blind, placebo controlled study. J Urol. 2003;170(6 Pt. 1):2333-2338.

Braunstein GD, Sundwall DA, Katz M, et al. Safety and efficacy of a testosterone patch for the treatment of hypoactive sexual desire disorder in surgically menopausal women: a randomized, placebo-controlled trial. Arch Intern Med. 2005;165(14):1582-1589.

Brubaker L, Chiang S, Zyczynski H, et al. The impact of stress incontinence surgery on female sexual function. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2009;200(5):562.e1-562.e7.

Caruso S, Intelisano G, Lupo L, Agnello C. Premenopausal women affected by sexual arousal disorder treated with sildenafil: a double-blind, cross-over, placebo-controlled study. BJOG. 2001;108(6):623-628.

Clayton AH, Warnock JK, Kornstein SG, et al. A placebo-controlled trial of bupropion SR as an antidote for selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor-induced sexual dysfunction. J Clin Psychiatry. 2004;65(1):62-67.

Davis SR, Davison SL, Donath S, Bell RJ. Circulating androgen levels and self-reported sexual function in women. JAMA. 2005;294(1):91-96.

Davis SR, Guay AT, Shifren JL, et al. Endocrine aspects of female sexual dysfunction. J Sex Med. 2004;1(3):237-253.

Davison SL, Bell R, Montalto JG, et al. Measurement of total testosterone in women: comparison of a direct radioimmunoassay versus radioimmunoassay after organic solvent extraction and celite column partition chromatography. Fertil Steril. 2005;84(6):1698-1704.

DeBattista C, Solvason B, Poirier J, et al. A placebo-controlled, randomized, double-blind study of adjunctive bupropion sustained release in the treatment of SSRI-induced sexual dysfunction. J Clin Psychiatry. 2005;66(7):844-848.

Deliganis AV, Maravilla KR, Heiman JR, et al. Female genitalia: dynamic MR imaging with use of MS-325 initial experiences evaluating female sexual response. Radiology. 2002;225(3):791-799.

Ferguson DM, Steidle CP, Singh GS, et al. Randomized, placebo-controlled, double blind, crossover design trial of the efficacy and safety of Zestra for Women in women with and without female sexual arousal disorder. J Sex Marital Ther, 29 Suppl. 1, 2003, 33-44.

Fisher WA, Rosen RC, Eardley I, et al. Sexual experience of female partners of men with erectile dysfunction: the female experience of men’s attitudes to life events and sexuality (FEMALES) study. J Sex Med. 2005;2(5):675-684.

Furuhjelm M, Karlgren E, Carlstrom K. The effect of estrogen therapy on somatic and psychical symptoms in postmenopausal women. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 1984;63(7):655-661.

Giraldi A, Marson L, Nappi R, et al. Physiology of female sexual function: animal models. J Sex Med. 2004;1(3):237-253.

Goldstat R, Briganti E, Tran J, et al. Transdermal testosterone therapy improves well-being, mood, and sexual function in premenopausal women. Menopause. 2003;10(5):390-398.

Goldstein I, Berman JR. Vasculogenic female sexual dysfunction: vaginal engorgement and clitoral erectile insufficiency syndromes. Int J Impot Res, 10 Suppl. 2, 1998, S84-S90.

Guay A, Munarriz R, Jacobson J, et al. Serum androgen levels in healthy premenopausal women with and without sexual dysfunction. Part A. Serum androgen levels in women aged 20-49 years with no complaints of sexual dysfunction. Int J Impot Res. 2004;16(2):112-120.

Haefner HK. Current evaluation and management of vulvovaginitis. Clin Obstet Gynecol. 1999;42(2):184-195.

Handa VL, Harvey L, Cundiff GW, et al. Sexual function among women with urinary incontinence and pelvic organ prolapse. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2004;191(3):751-756.

Handa VL, Zyczynski HM, Brubaker L, et al. Sexual function before and after sacrocolpopexy for pelvic organ prolapse. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2007;197(6):629.e1-629.e6.

Hansen BL. Lower urinary tract symptoms (LUTS) and sexual function in both sexes. Eur Urol. 2004;46(2):229-234.

Hayes RD, Dennerstein L, Bennett CM, et al. What is the “true” prevalence of female sexual dysfunctions and does the way we assess these conditions have an impact? J Sex Med. 2008;5:777-787.

Ito TY, Polan ML, Whipple B, et al. The enhancement of female sexual function with ArginMax, a nutritional supplement, among women differing in menopausal status. J Sex Marital Ther. 2006;32(5):369-378.

Ito TY, Trant AS, Polan ML. A double-blind placebo-controlled study of ArginMax, a nutritional supplement for enhancement of female sexual function. J Sex Marital Ther. 2001;27(5):541-549.

Jeong GW, Park K, Youn G, et al. Assessment of cerebrocortical regions associated with sexual arousal in premenopausal and menopausal women by using BOLD-based functional MRI. J Sex Med. 2005;2(5):645-651.

Kammerer-Doak D, Rogers RG. Female sexual function and dysfunction. Obstet Gynecol Clin North Am. 2008;35(2):169-183. vii

Kaplan SA, Reis RB, Kohn IJ, et al. Safety and efficacy of sildenafil in postmenopausal women with sexual dysfunction. Urology. 1999;53(3):481-486.

Katz VL, Lentz GM, Lobo RA, Gershenson DM, editors. Comprehensive gynecology, 5th ed, Philadelphia: Mosby Elsevier, 2007.

Kehoe S, Luesley D. Vulvar vestibulitis treated by modified vestibulectomy. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 1999;64(2):147-152.

Khalifé S, Binik YM, Cohen DR, et al. Evaluation of clitoral blood flow by color Doppler ultrasonography. J Sex Marital Ther. 2000;26(2):187-189.

Kingsberg S, Althof SE. Evaluation and treatment of female sexual disorders. Int Urogynecol J Pelvic Floor Dysfunct. 2009;20(Suppl. 1):S33-S43.

Kingsberg SA, Janata JW. Female sexual disorders: assessment, diagnosis, and treatment. Urol Clin North Am. 2007;34(4):497-506. v–vi

Komisaruk BR, Whipple B. Functional MRI of the brain during orgasm in women. Annu Rev Sex Res. 2005;16:62-86.

Landry T, Bergeron S, Dupuis MJ, et al. The treatment of provoked vestibulodynia: a critical review. Clin J Pain. 2008;24(2):155-171.

Laumann EO, Paik A, Rosen RC. Sexual dysfunction in the United States: prevalence and predictors. JAMA. 1999;281(6):537-544.

Leiblum S, Bachmann G, Kemmann E, et al. Vaginal atrophy in the postmenopausal woman: the importance of sexual activity and hormones. JAMA. 1983;249(16):2195-2198.

Maravilla KR, Cao Y, Heiman JR, et al. Serial MR imaging with MS-325 for evaluating female sexual arousal response: determination of intrasubject reproducibility. J Magn Reson Imaging. 2003;18(2):216-224.

McCoy NL, Davidson JM. A longitudinal study of the effects of menopause on sexuality. Maturitas. 1985;7(3):203-210.

Meston CM. Sympathetic nervous system activity and female sexual arousal. Am J Cardiol. 2000;86(2A):30F-34F.

Meston CM, Frohlich PF. The neurobiology of sexual function. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2000;57(11):1012-1030.

Modell JG, May RS, Katholi CR. Effect of bupropion-SR on orgasmic dysfunction in nondepressed subjects: a pilot study. J Sex Marital Ther. 2000;26(3):231-240.

Munarriz R, Kim NN, Goldstein I, et al. Biology of female sexual function. Urol Clin North Am. 2002;29(3):685-693.

Munarriz R, Maitland S, Garcia SP, et al. A prospective duplex Doppler ultrasonographic study in women with sexual arousal disorder to objectively assess genital engorgement induced by EROS therapy. J Sex Marital Ther, 29 Suppl. 1, 2003, 85-94.

Nappi R, Salonia A, Traish AM, et al. Clinical biologic pathophysiologies of women’s sexual dysfunction. J Sex Med. 2005;2(1):4-25.

Nathorst-Boos J, von Schoultz B, Carlstrom K. Elective ovarian removal and estrogen replacement therapy—effects on sexual life, psychological well-being and androgen status. J Psychosom Obstet Gynaecol. 1993;14(4):283-293.

Nathorst-Boos J, Wiklund I, Mattsson LA, et al. Is sexual life influenced by transdermal estrogen therapy? A double blind placebo controlled study in postmenopausal women. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 1993;72(8):656-660.

Nicolosi A, Laumann EO, Glasser DB, et al. Sexual behavior and sexual dysfunctions after age 40: the global study of sexual attitudes and behaviors. Urology. 2004;64(5):991-997.

Nurnberg HG, Hensley PL, Heiman JR, et al. Sildenafil treatment of women with antidepressant-associated sexual dysfunction: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2008;300(4):395-404.

Nurnberg HG, Lauriello J, Hensley PL, et al. Sildenafil for sexual dysfunction in women taking antidepressants. Am J Psychiatry. 1999;156(10):1664.

Nusbaum MR, Gamble G, Skinner B, et al. The high prevalence of sexual concerns among women seeking routine gynecological care. J Fam Pract. 2000;49(3):229-232.

Park K, Kang HK, Seo JJ, et al. Blood-oxygenation-level-dependent functional magnetic resonance imaging for evaluating cerebral regions of female sexual arousal response. Urology. 2001;57(6):1189-1194.

Pasqualotto EB, Pasqualotto FF, Sobreiro BP, et al. Female sexual dysfunction: the important points to remember. Clinics (Sao Paulo). 2005;60(1):51-60.

Pauls RN, Kleeman SD, Segal JL, et al. Practice patterns of physician members of the American Urogynecologic Society regarding female sexual dysfunction: results of a national survey. Int Urogynecol J Pelvic Floor Dysfunct. 2005;16(6):460-467.

Persky H. Tetrahydrocortisol/tetrahydrocortisone ratio (H4F/H4E) as an indicator of depressive feelings. Psychosom Med. 1976;38(1):13-18.

Persky H, Dreisbach L, Miller WR, et al. The relation of plasma androgen levels to sexual behaviors and attitudes of women. Psychosom Med. 1982;44(4):305-319.

Plouffe LJr. Screening for sexual problems through a simple questionnaire. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1985;151(2):166-169.

Raina R, Pahlajani G, Khan S, et al. Female sexual dysfunction: classification, pathophysiology, and management. Fertil Steril. 2007;88(5):1273-1284.

Rosen RC, Fisher WA, Beneke M, et al. The COUPLES-project: a pooled analysis of patient and partner treatment satisfaction scale (TSS) outcomes following vardenafil treatment. BJU Int. 2007;99(4):849-859.

Rosner W, Auchus RJ, Azziz R, et al. Position statement: utility, limitations, and pitfalls in measuring testosterone: an endocrine society position statement. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2007;92(2):405-413.

Salerian AJ, Deibler WE, Vittone BJ, et al. Sildenafil for psychotropic-induced sexual dysfunction in 31 women and 61 men. J Sex Marital Ther. 2000;26(2):133-140.

Salonia A, Munarriz RM, Naspro R, et al. Women’s sexual dysfunction: a pathophysiological review. BJU Int. 2004;93:1156-1164.

Schreiner-Engel P, Schiavi RC, Smith H, White D. Sexual arousability and the menstrual cycle. Psychosom Med. 1981;43(3):199-214.

Schreiner-Engel P, Schiavi RC, White D, Ghizzani A. Low sexual desire in women: the role of reproductive hormones. Horm Behav. 1989;23(2):221-234.

Schwenkhagen A, Studd J. Role of testosterone in the treatment of hypoactive sexual desire disorder. Maturitas. 2009;63(2):152-159.

Segraves RT, Clayton A, Croft H, et al. Bupropion sustained release for the treatment of hypoactive sexual desire disorder in premenopausal women. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2004;24(3):339-342.

Segraves RT, Croft H, Kavoussi R, et al. Bupropion sustained release (SR) for the treatment of hypoactive sexual desire disorder (HSDD) in nondepressed women. J Sex Marital Ther. 2001;27(3):303-316.

Sherwin BB, Gelfand MM. Differential symptom response to parenteral estrogen and/or androgen administration in the surgical menopause. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1985;151(2):153-160.

Sherwin BB, Gelfand MM. Sex steroids and affect in the surgical menopause: a double-blind, cross-over study. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 1985;10(3):325-335.

Shifren JL, Braunstein GD, Simon JA, et al. Transdermal testosterone treatment in women with impaired sexual function after oophorectomy. N Engl J Med. 2000;343(10):682-688.

Shifren JL, Davis SR, Moreau M, et al. Testosterone patch for the treatment of hypoactive sexual desire disorder in naturally menopausal women: results from the INTIMATE NM1 study. Menopause. 2006;13(5):770-779.

Shifren JL, Monz BU, Russo PA, et al. Sexual problems and distress in United States women: prevalence and correlates. Obstet Gynecol. 2008;112(5):970-978.

Shufelt CL, Braunstein GD. Testosterone and the breast. Menopause Int. 2008;14(3):117-122.

Simpson ER. Role of aromatase in sex steroid action. J Mol Endocrinol. 2000;25(2):149-156.

Södergård R, Bäckström T, Shanbhag V, Carstensen H. Calculation of free and bound fractions of testosterone and estradiol-17 beta to human plasma proteins at body temperature. J Steroid Biochem. 1982;16(6):801-810.

Somboonporn W, Davis S, Seif MW, Bell R. Testosterone for peri- and postmenopausal women. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2005;(4):CD004509.

Stuart FM, Hammond DC, Pett MA. Inhibited sexual desire in women. Arch Sex Behav. 1987;16(2):91-106.

Suh DD, Yang CC, Cao Y, et al. Magnetic resonance imaging anatomy of the female genitalia in premenopausal and postmenopausal women. J Urol. 2003;170(1):138-144.

Suh DD, Yang CC, Cao Y, et al. MRI of female genital and pelvic organs during sexual arousal. J Psychosom Obstet Gynaecol. 2004;25(2):153-162.

Tarcan T, Park K, Goldstein I, et al. Histomorphometric analysis of age-related structural changes in human clitoral cavernosal tissue. J Urol. 1999;161(3):940-944.

Verit FF, Yeni E, Kafali H. Progress in female sexual dysfunction. Urol Int. 2006;76(1):1-10.

Vierhapper H, Nowotny P, Waldhäusl W. Determination of testosterone production rates in men and women using stable isotope/dilution and mass spectrometry. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1997;82(5):1492-1496.

Walsh PC, Retik AB, Vaughan JrE, et al, editors. Campbell’s urology, 8th ed, Philadelphia: WB Saunders, 2002.

Wierman ME, Basson R, Davis SR, et al. Androgen therapy in women: an Endocrine Society Clinical Practice guideline. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2006;91(10):3697-3710.

Wilson SK, Delk JR2nd, Billups KL. Treating symptoms of female sexual arousal disorder with the Eros-Clitoral Therapy Device. J Gend Specif Med. 2001;4(2):54-58.

Zumoff B, Strain GW, Miller LK, et al. Twenty-four-hour mean plasma testosterone concentration declines with age in normal premenopausal women. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1995;80(4):1429-1430.