chapter 94 Retropubic and Suprapubic Open Prostatectomy

The treatment options for bladder outlet obstruction due to benign prostatic hyperplasia have been expanded dramatically over the past 2 decades with the development of medical and minimally invasive therapies. The current medical therapies for lower urinary tract symptoms (LUTS) include selective long-acting α1-adrenergic antagonists, such as terazosin (Hytrin [Lepor et al, 1992; Roehrborn et al, 1996]), doxazosin (Cardura [Gillenwater et al, 1995]), and tamsulosin (Flomax [Abrams et al, 1995]), and the 5α-reductase blockers, such as finasteride (Proscar [Gormley et al, 1992; Andersen et al, 1995; Lepor et al, 1996]) and dutasteride (Avodart [Roehrborn et al, 2002, 2004]). Minimally invasive procedures include visual laser ablation of the prostate (VLAP [Cowles et al, 1995]), transurethral electrovaporization of the prostate (TVP [Kaplan et al, 1996]), transurethral needle ablation (TUNA [Schulman et al, 1993; Campo et al, 1997]), transurethral microwave thermotherapy (TUMT [Ogden et al, 1993; Javle et al, 1996]), interstitial laser coagulation (ILC [Muschter and Hofstetter, 1995]) and transurethral incision of the prostate (TUIP [Cornford et al, 1997]). However, these approaches are usually reserved for men with moderate symptoms and a small to medium-sized prostate gland (Reich et al, 2006). For larger prostate glands, open prostatectomy has been frequently performed. Lately, holmium laser enucleation of the prostate (HoLEP) with the holmium : yttrium-aluminum-garnet (Ho : YAG) laser has been performed as a minimally invasive alternative to open surgery (Gilling et al, 1998). Most recently, as urologists gain experience in minimally invasive therapy, a simple prostatectomy has been performed using a laparoscopic or robotic approach (Sotelo et al, 2005, 2008; Mariano et al, 2006).

For patients with acute urinary retention, persistent or recurrent urinary tract infections, severe hemorrhage from the prostate, bladder calculi, severe symptoms unresponsive to medical therapy, and/or renal insufficiency as a result of chronic bladder outlet obstruction, transurethral resection of the prostate (TURP) or open prostatectomy is indicated. When compared with TURP, open prostatectomy offers the advantages of lower re-treatment rate and more complete removal of the prostatic adenoma under direct vision and avoids the risk of dilutional hyponatremia (the TUR syndrome) that occurs in approximately 2% of patients undergoing TURP (Mebust et al, 1989; Roos et al, 1989). Several contemporary series have demonstrated objective improvement in urinary symptoms after open prostatectomy (Tubaro et al, 2001; Gacci et al, 2003; Varkarakis et al, 2004). The disadvantages of open prostatectomy, as compared with TURP, include the need for a lower midline incision and a resultant longer hospitalization and convalescence period. There also may be an increased potential for perioperative hemorrhage (Serretta et al, 2002).

Open prostatectomy can be performed by either the retropubic or the suprapubic approach. In retropubic prostatectomy the enucleation of the hyperplastic prostatic adenoma is achieved through a direct incision of the anterior prostatic capsule. This approach to open prostatectomy was popularized by Terrence Millin, who reported the results of the procedure on 20 patients in Lancet in 1945 (Millin, 1945). The advantages of this procedure over the suprapubic approach are (1) excellent anatomic exposure of the prostate, (2) direct visualization of the prostatic adenoma during enucleation to ensure complete removal, (3) precise transection of the urethra distally to preserve urinary continence, (4) clear and immediate visualization of the prostatic fossa after enucleation to control bleeding, and (5) minimal to no surgical trauma to the urinary bladder. The disadvantage of the retropubic approach, as compared with the suprapubic prostatectomy, is that direct access to the bladder is not achieved. This may be important when one considers excising a concomitant bladder diverticulum or removing bladder calculi. The suprapubic approach also may be the preferred method when the obstructive prostatic enlargement includes a large intravesical median lobe.

Suprapubic prostatectomy, or transvesical prostatectomy, consists of the enucleation of the hyperplastic prostatic adenoma through an extraperitoneal incision of the lower anterior bladder wall. This approach to open prostatectomy was first performed by Eugene Fuller in New York in 1894; it was later popularized by Peter Freyer in London, England, who described the procedure in 1900 and later reported the results of his first 1000 patients in 1912 (Freyer, 1912). The major advantage of this suprapubic procedure over the retropubic approach is that it allows direct visualization of the bladder neck and bladder mucosa. As a result, this operation is ideally suited for patients with (1) a large median lobe protruding into the bladder, (2) a clinically significant bladder diverticulum, or (3) large bladder calculi. It also may be preferable for obese men, in whom it is difficult to gain direct access to the prostatic capsule and dorsal vein complex (Culp, 1975). The disadvantage, as compared with the retropubic approach, is that direct visualization of the apical prostatic adenoma is reduced. As a result, the apical enucleation is less precise and this factor may affect postoperative urinary continence. Furthermore, hemostasis may be more difficult because of inadequate visualization of the entire prostatic fossa after enucleation.

Indications for Open Prostatectomy

The indications for prostatectomy, by either open approach or transurethral resection, include (1) acute urinary retention; (2) recurrent or persistent urinary tract infections; (3) significant symptoms from bladder outlet obstruction not responsive to medical therapy; (4) recurrent gross hematuria of prostatic origin; (5) pathophysiologic changes of the kidneys, ureters, or bladder secondary to prostatic obstruction; and (6) bladder calculi secondary to obstruction.

Open prostatectomy should be considered when the obstructive tissue is estimated to weigh more than 75 g. If sizable bladder diverticula justify removal, suprapubic prostatectomy and diverticulectomy should be performed concurrently. If the prostatectomy is performed without the diverticulectomy, incomplete emptying of the bladder diverticulum and subsequent, persistent infection may occur. Large bladder calculi that are not amenable to easy transurethral fragmentation may also be removed during the open procedure. Open prostatectomy should also be considered when a patient presents with ankylosis of the hip or other orthopedic conditions that prevent proper positioning for TURP. Also, it may be wise to perform an open prostatectomy in men with recurrent or complex urethral conditions, such as urethral stricture or previous hypospadias repair, to avoid the urethral trauma associated with TURP. Finally, the association of an inguinal hernia with an enlarged prostate suggests an open procedure, because the hernia may be repaired via the same lower abdominal incision (Schlegel and Walsh, 1987; Brunocilla et al, 2005).

Contraindications to open prostatectomy include a small fibrous gland, the presence of prostate cancer, and previous prostatectomy or pelvic surgery that may obliterate access to the prostate gland.

Preoperative Evaluation

In deciding whether to perform an open prostatectomy for symptomatic obstruction due to benign prostatic hyperplasia, it may be necessary to consider the upper and lower urinary tracts. Usually the patient will have already completed the International Prostate Symptom Score (IPSS) questionnaire and had a peak urinary flow rate determination. The postvoid residual urine volume also may have been verified with abdominal ultrasonography. A cystoscopic examination is not indicated in the routine evaluation of a patient with obstructive voiding symptoms (McConnell et al, 1994). However, cystoscopy should be performed in men with hematuria, suspected urethral stricture, and bladder calculus or diverticulum. It also can be helpful in confirming the presence of a large median lobe or in assessing the length of the prostatic urethra. For this indication it is most ideal to perform the cystoscopic examination with the patient under anesthesia just before surgery, when the pelvic floor musculature is relaxed.

Before performing an open prostatectomy the presence of prostate cancer should be excluded. All men should undergo a digital rectal examination and have a serum prostate-specific antigen determination. If the digital rectal examination detects induration or nodularity, or the serum prostate-specific antigen level is elevated, a transrectal ultrasound-guided biopsy of the prostate gland should be performed. Transrectal ultrasonography, by itself, is not indicated as a first-line diagnostic test for evaluating the prostate gland to detect early, curable prostate cancer. However, it can be useful in determining prostate size.

The upper urinary tracts should be evaluated preoperatively in men with known renal disease, abnormal renal function, recurrent urinary tract infection, or hematuria. This can be accomplished by an intravenous pyelogram with a postvoid drainage film, by computed tomography in patients with normal renal function, or by renal ultrasonography in men with compromised renal function. Magnetic resonance imaging is not commonly indicated.

Before surgery the patient should undergo a complete medical evaluation consisting of a detailed history, thorough physical examination, and appropriate laboratory assessment. Most patients will be of an age with an increased risk for cardiovascular and pulmonary disease, hypertension, diabetes mellitus and other medical conditions. All abnormalities uncovered in this evaluation should be addressed. The patient’s medications should be reviewed and attention should be given to the agents such as aspirin and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory agents that can contribute to perioperative bleeding. These medications should be discontinued and therapeutic anticoagulation reversed before surgery. In addition, a chest radiograph, electrocardiogram, routine electrolyte studies, coagulation studies, and a complete blood cell count are usually required for these patients before surgery.

Men in urinary retention should have an evaluation of renal function. If the serum creatinine value is elevated, surgery should be delayed until this parameter stabilizes. Urinalysis is performed to rule out a urinary tract infection; and, if an infection is suspected, a urine specimen should be sent for culture and sensitivity. If an infection is present, appropriate antimicrobial therapy must be instituted before surgery to prevent urinary sepsis (Serretta et al, 2002).

Historically, 3% to 10% of men undergoing an open prostatectomy will require one or more units of blood in the perioperative period (Serretta et al, 2002; Varkarakis et al, 2004; Zargooshi, 2007). Thus it may be prudent to have one or two units of blood available intraoperatively. Patients who are concerned about infectious processes associated with blood transfusion can donate one to two units of autologous blood before surgery so that it is available at the time of the procedure. The preferred autologous donation schedule is one unit per week, with the last donation 2 weeks before surgery. During this process, the patient should receive oral iron supplementation (ferrous sulfate or ferrous gluconate).

Lastly, the patient must be informed of the benefits and risks associated with open prostatectomy and written informed consent should be obtained. The benefit to be achieved is improved urination. Potential risks include urinary incontinence, erectile dysfunction, retrograde ejaculation, urinary tract infection, bladder neck contracture, urethral stricture, and the need for a blood transfusion. Other potential untoward effects include deep vein thrombosis and pulmonary embolus.

Operating Day Preparation

The patient is kept without oral intake after midnight and self-administers a Fleet enema the morning of surgery. The type of the anesthesia to be used and the risks associated with it are discussed and finalized with the patient and his family in conjunction with the anesthesiologist. One dose of a second-generation cephalosporin is administered before making the incision.

Surgical Technique

Anesthesia

The preferred anesthesia is spinal or epidural. Regional anesthesia may reduce intraoperative blood loss and the frequency of postoperative deep vein thrombosis and pulmonary embolus (Peters and Walsh, 1985). General anesthesia is utilized when there is a medical or anatomic contraindication to regional anesthesia or when the patient simply prefers general anesthesia.

Retropubic Prostatectomy

Proper Positioning of the Patient

Once anesthesia has been induced the patient is positioned on the operating table in a supine position. If a cystoscopic examination is to be performed, the patient is prepped and draped in the usual manner for a transurethral diagnostic procedure. Flexible cystoscopy, in this situation, will obviate major repositioning of the patient. After the cystoscopy the table is placed in a mild Trendelenburg position without extension.

Incision and Exposure of the Prostate

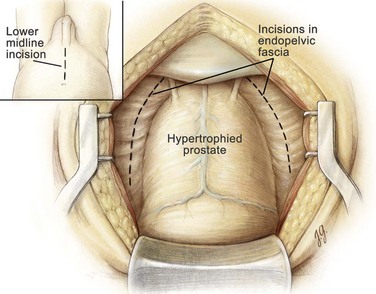

The suprapubic area is shaved, prepped, and draped in the usual sterile manner. A 22-Fr urethral catheter with a 30-mL balloon is passed into the bladder and connected to a sterile closed drainage system, and the balloon is inflated with 30 mL of saline. A lower midline incision from the umbilicus to the pubic symphysis is made. It is deepened through the subcutaneous tissue. The linea alba is incised, allowing the rectus abdominis muscles to be separated in the midline. The transversalis fascia is incised sharply to expose the space of Retzius. At the superior aspect of the wound the posterior rectus abdominis fascia is incised above the semicircular line to the level of the umbilicus and the peritoneum is mobilized cephalad starting at the pubic symphysis and swept anterolaterally. The pelvis is inspected for any abnormalities, and the inguinal area is examined for hernias. If a hernia is identified, it can be repaired using the preperitoneal approach described by Schlegel and Walsh (1987). A self-retaining Balfour retractor is placed in the incision and widened. A well-padded, malleable blade is connected to the retractor and used to displace the bladder posteriorly and superiorly. Unlike an anatomic radical retropubic prostatectomy, the balloon of the catheter is not positioned beneath the malleable blade. Instead it is allowed to rest at the level of the bladder neck and aids in identifying the prostatovesical junction later in the operation. The anterior surface of the bladder and prostate are exposed. With the use of DeBakey forceps and Metzenbaum scissors, the preprostatic adipose tissue is gently removed to expose the superficial branch of the dorsal vein complex and the puboprostatic ligaments (Fig. 94–1).

Figure 94–1 Retropubic prostatectomy. The space of Retzius has been opened and the periprostatic adipose tissue has been dissected free from the superficial branch of the dorsal vein complex. The endopelvic fascia is incised bilaterally (dotted lines), and the puboprostatic ligaments are transected bilaterally.

Hemostatic Maneuvers

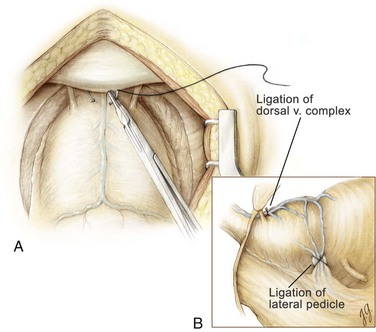

Before proceeding with enucleation of the prostatic adenoma it is important to achieve complete control of the dorsal vein complex as well as the lateral pedicles at the bladder neck (the main arterial blood supply to the prostate gland) (Walsh and Oesterling, 1990). To accomplish this task the endopelvic fascia is incised laterally and the puboprostatic ligaments are partially transected, similar to the maneuver in an anatomic radical retropubic prostatectomy (Reiner and Walsh, 1979). In patients with marked prostatic enlargement this maneuver can be easier because the enlarged prostate gland protrudes out from beneath the pubic symphysis. A 3-0 Monocryl suture on a  -inch circle-tapered needle is passed in the avascular plane between the urethra and the dorsal vein complex at the apex of the prostate and tied (Fig. 94–2A). The superficial branch of the dorsal vein at the bladder should be coagulated or ligated.

-inch circle-tapered needle is passed in the avascular plane between the urethra and the dorsal vein complex at the apex of the prostate and tied (Fig. 94–2A). The superficial branch of the dorsal vein at the bladder should be coagulated or ligated.

Figure 94–2 Retropubic prostatectomy. A, A 2-0 chromic suture on a  -inch circle-tapered needle is passed in the avascular plane between the urethra and the dorsal vein complex at the apex of the prostate. A tie is grasped and tied around the dorsal vein complex. B, With 2-0 chromic suture material on a CTX needle, a figure-of-eight suture is placed through the prostatovesicular junction just above the level of the seminal vesicles to control the main arterial blood supply to the prostate gland. When placing this suture, care must be taken to avoid entrapment of the neurovascular bundles located posteriorly and slightly laterally.

-inch circle-tapered needle is passed in the avascular plane between the urethra and the dorsal vein complex at the apex of the prostate. A tie is grasped and tied around the dorsal vein complex. B, With 2-0 chromic suture material on a CTX needle, a figure-of-eight suture is placed through the prostatovesicular junction just above the level of the seminal vesicles to control the main arterial blood supply to the prostate gland. When placing this suture, care must be taken to avoid entrapment of the neurovascular bundles located posteriorly and slightly laterally.

At this point attention is focused on securing the lateral pedicles at the prostatovesical junction. The 30-mL balloon of the catheter is used to identify the junction between the bladder and the prostate. The balloon is then deflated and 2-0 chromic suture material on a large CTX needle is used to place a figure-of-eight suture deep into the prostatovesical junction at the level where the seminal vesicles approach the prostate gland bilaterally (see Fig. 94–2B). With this maneuver, the main arterial blood supply to the prostate adenoma is controlled. Having secured the dorsal vein complex earlier, the major sources of hemorrhage for this operation have been eliminated.

Enucleation of the Adenoma

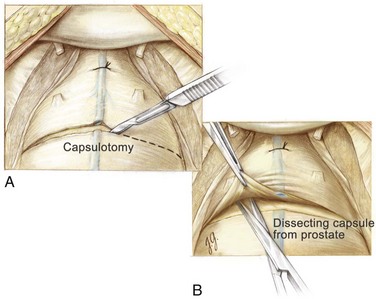

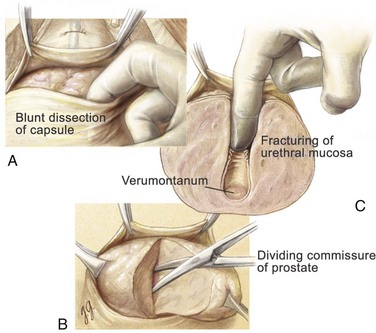

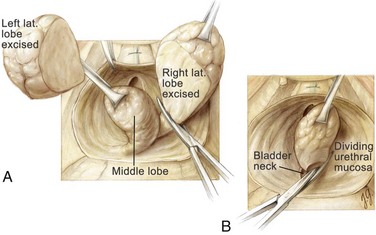

With a sponge stick on the bladder neck to depress the bladder posteriorly, a No. 15 blade on a long handle is used to make a transverse capsulotomy in the prostate 1.5 to 2.0 cm distal to the bladder neck (Fig. 94–3). The superficial branch of the dorsal vein complex is transected as the transverse capsulotomy is made. It does not bleed because hemostasis of the dorsal vein complex has previously been controlled both proximally and distally. The incision is deepened to the level of the adenoma and extended sufficiently lateral in each direction to permit complete enucleation. A pair of Metzenbaum scissors is used to dissect the overlying prostatic capsule from the underlying prostatic adenoma. Once a well-defined plane is sufficiently developed, the index finger can be inserted between the prostatic adenoma and the capsule to further develop the plane laterally and posteriorly (Fig. 94–4). A pair of Metzenbaum scissors is then used to incise the anterior commissure from the bladder neck to the apex separating the lateral lobes of the prostate anteriorly. The posterior prostatic urethra is exposed, and the index finger is inserted down to the verumontanum. The mucosa of the urethra overlying the left lateral lobe is divided sharply at the level of the apex under direct vision without injury to the external urinary sphincter. With the aid of a Babcock clamp, the left lateral lobe is removed safely. This maneuver is then repeated for the right lateral lobe. If a median lobe is present, the overlying mucosa is incised at the level of the bladder neck and this lobe is removed (Fig. 94–5). In this manner the entire prostatic adenoma is removed with preservation of a strip of posterior prostatic urethra. Because the capsulotomy was a transverse rather than longitudinal incision there is little risk that the incision will be inadvertently extended into the sphincteric mechanism during the enucleation process, which would compromise subsequent urinary continence.

Figure 94–3 Retropubic prostatectomy. A, With the superficial branch of the dorsal vein complex secured proximally and distally, a No. 15 blade on a long handle is used to make the transverse capsulotomy. B, Metzenbaum scissors are used to develop the plane anteriorly between the prostatic adenoma and the prostatic capsule.

Figure 94–4 Retropubic prostatectomy. A, With blunt dissection with the index finger, the prostatic adenoma is dissected free laterally and posteriorly. B, Metzenbaum scissors are used to divide the anterior commissure to visualize the posterior urethra and verumontanum. C, The index finger is then used to fracture the urethral mucosa at the level of the verumontanum. With this last maneuver, extreme care is taken not to injure the external sphincteric mechanism.

Figure 94–5 Retropubic prostatectomy. A, After removal of the left lateral lobe of the prostate, the right lateral lobe is excised with the aid of a tenaculum and Metzenbaum scissors. B, Lastly, the median lobe is removed under direct vision.

The prostatic fossa is now carefully inspected to ensure that all of the adenoma has been removed and that hemostasis is complete. If hemorrhage is persistent, 4-0 chromic suture material can be used to place a figure-of-eight suture in the bladder neck at the 5- and 7-o’clock positions as in suprapubic prostatectomy (see Fig. 94–11). When placing these sutures it is necessary to visualize the ureteral orifices so that they are not incorporated. Indigo carmine dye may be given intravenously to aid in the visualization of the ureteral orifices if necessary. If the bladder neck appears obstructive at the completion of the operation, it may be appropriate to perform a wedge resection at the 6-o’clock position and advance the bladder mucosa into the prostatic fossa. The maneuver helps prevent the development of a bladder neck contracture.

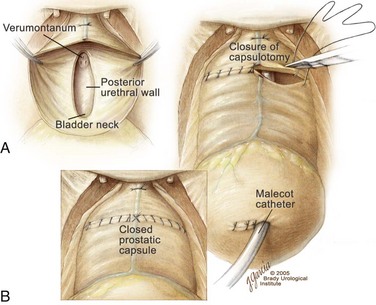

Closure

After inspecting the bladder for complete adenoma removal and hemostasis, a 22-Fr, three-way Foley catheter with a 30-mL balloon is inserted through the anterior urethra and prostatic fossa into the bladder. With the urethral catheter in place, the prostatic capsule is closed (Fig. 94–6). Then 2-0 chromic suture material on a  -inch circle-tapered needle is used to create two running sutures. These sutures begin laterally and meet in the midline; they are first tied separately and then together to create a watertight closure. Fifty milliliters of water is then placed in the balloon to ensure that the catheter balloon remains in the bladder and does not retract into the prostatic fossa. The bladder is then irrigated with saline to ensure continued hemostasis and to test the capsular closure for leakage. A small, closed-suction drain is placed via a separate stab incision lateral to the prostate and bladder on one side to prevent hematoma and urinoma formation. The pelvis is irrigated with copious amounts of normal saline solution, and the rectus fascia is reapproximated with a size 1 PDS suture on a TPI needle in a running fashion. The skin is closed with skin staples. The drain is secured to the abdominal wall, and the urethral catheter is secured to the lower extremity.

-inch circle-tapered needle is used to create two running sutures. These sutures begin laterally and meet in the midline; they are first tied separately and then together to create a watertight closure. Fifty milliliters of water is then placed in the balloon to ensure that the catheter balloon remains in the bladder and does not retract into the prostatic fossa. The bladder is then irrigated with saline to ensure continued hemostasis and to test the capsular closure for leakage. A small, closed-suction drain is placed via a separate stab incision lateral to the prostate and bladder on one side to prevent hematoma and urinoma formation. The pelvis is irrigated with copious amounts of normal saline solution, and the rectus fascia is reapproximated with a size 1 PDS suture on a TPI needle in a running fashion. The skin is closed with skin staples. The drain is secured to the abdominal wall, and the urethral catheter is secured to the lower extremity.

Figure 94–6 Retropubic prostatectomy. A, View of the prostatic fossa and posterior urethra after enucleation of all the prostatic adenoma. Note that the verumontanum and a strip of posterior urethra remain intact. B, After placement of a urethral catheter and, if needed, a Malecot suprapubic tube, the transverse capsulotomy is closed with two running 2-0 chromic sutures. The two sutures are tied first to themselves and then to each other across the midline to create a watertight closure of the prostatic capsule.

Suprapubic Prostatectomy

Proper Positioning of the Patient

After anesthesia has been induced, the patient is positioned on the operating table in a supine position. Cystoscopy, if clinically indicated, is performed as previously described. The table is placed in a mild Trendelenburg position without extension. The patient’s suprapubic area is shaved. After the lower abdomen and external genital area are prepped and draped in the usual sterile manner, a 22-Fr catheter is inserted into the bladder. After residual urine is drained, 250 mL of saline is instilled into the bladder and the catheter is clamped.

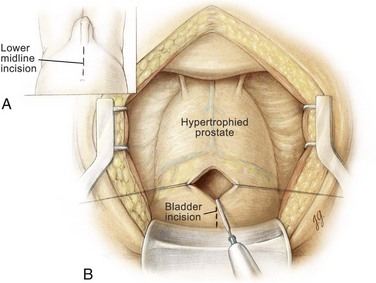

Incision and Exposure of the Prostate

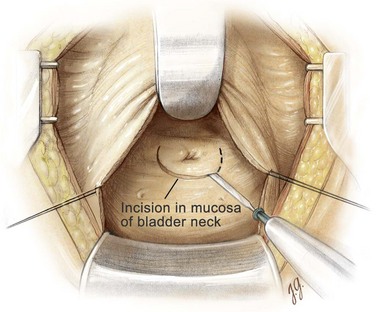

A lower midline incision is made from the umbilicus to the pubic symphysis (Fig. 94–7). It is deepened through the subcutaneous tissue. The linea alba is incised, allowing the rectus abdominis muscles to be separated in the midline. The transversalis fascia is incised sharply to expose the space of Retzius. At the superior aspect of the wound the posterior rectus abdominis fascia is incised above the semicircular line to the level of the umbilicus and the peritoneum is then swept cephalad to develop the prevesical space. A self-retaining Balfour retractor is placed in the incision to retract the rectus muscles laterally. The anterior bladder wall is identified, and two 3-0 Vicryl stitches are placed on each side of the midline below the peritoneal reflection. A vertical cystotomy is made with an electrocautery. With the use of a pair of Metzenbaum scissors, a cystotomy is then extended cephalad and caudally to within 1 cm of the bladder neck (Fig. 94–8). Several pairs of stay sutures are placed using 3-0 Vicryl on each side of the midline to facilitate exposure. A figure-of-eight suture using 3-0 Vicryl is placed and tied at the most caudal position of the cystotomy to prevent further extension of the cystotomy incision during blunt finger dissection of the adenoma. Alternatively, a transverse bladder incision can be utilized. After inspecting the bladder, a well-padded, malleable blade is placed in the bladder, connected to the Balfour retractor, and used to retract the bladder cephalad. The bladder neck and prostate gland now can be visualized. A narrow Deaver retractor can be placed over the bladder neck and used to further expose the trigone. Indigo carmine dye may be given intravenously to aid in the visualization of the ureteral orifices if necessary.

Enucleation of the Adenoma

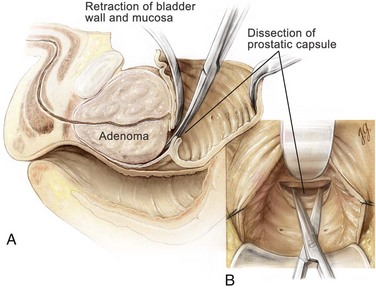

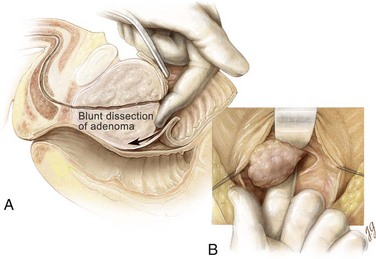

An electrocautery is used to create a circular incision in the bladder mucosa distal to the trigone (see Fig. 94–8). Care is taken not to injure the ureteral orifices. With the use of a pair of Metzenbaum scissors, the plane between the prostatic adenoma and prostatic capsule is developed at the 6-o’clock position (Fig. 94–9). Once a well-established plane is created posteriorly, the prostatic adenoma is dissected circumferentially and inferiorly toward the apex, using blunt dissection (Fig. 94–10). At the apex the prostatic urethra is transected using a pinch action of the two fingertips and avoiding excessive traction so as not to avulse the urethra and injure the sphincteric mechanism. At this point the prostatic adenoma, either as one unit or separate lobes, can be removed from the prostatic fossa.

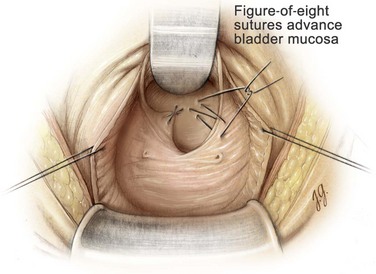

Hemostatic Maneuvers

After enucleation of the adenoma the prostatic fossa is inspected for residual tissue. If found, these nodules are removed by sharp or blunt dissection. The prostatic fossa also must be examined for discrete bleeding sites that frequently can be controlled with an electrocautery or 4-0 chromic suture ligatures. In addition, a 0-chromic suture is used to place two figure-of-eight sutures to advance the bladder mucosa into the prostatic fossa at the 5-o’clock and 7-o’clock positions at the prostatovesical junction to ensure control of the main arterial blood supply to the prostate (Fig. 94–11). With this maneuver, hemostasis is usually complete.

Figure 94–11 Suprapubic prostatectomy. After enucleation of the entire prostatic adenoma, a 0-chromic suture is used to place two figure-of-eight sutures to advance bladder mucosa into the prostatic fossa at the 5- and 7-o’clock positions at the prostatovesicular junction to ensure control of the main arterial blood supply to the prostate.

If hemorrhage remains pronounced despite the hemostatic sutures, a size 2 nylon purse-string suture can be placed around the vesical neck, brought out through the skin, and tied firmly, as described by Malament (1965). This maneuver closes the bladder neck and tamponades the prostatic fossa. The nylon suture is removed by cutting it at the skin and applying gentle traction on postoperative day 2 or 3. Plicating sutures can be placed transversely in the posterior prostatic capsule to prevent further bleeding, as described by O’Conor (1982).

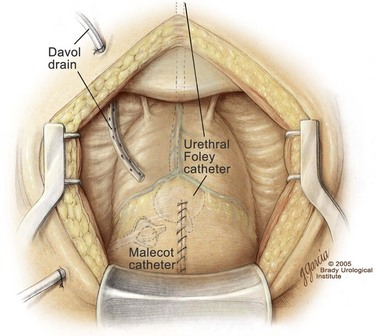

Closure

A 22-Fr urethral catheter with a 30-mL balloon is passed through the urethra into the bladder. In addition, a 20- to 24-Fr Malecot suprapubic tube is placed into the dome of the bladder and secured with a 4-0 chromic purse-string suture. The suprapubic tube exits the bladder via a separate stab incision at the lateral aspect of the dome, avoiding the peritoneal cavity (Fig. 94–12). Next, the cystotomy incision is closed in two layers. The first layer of closure is performed using a 2-0 Vicryl to create two running sutures. Care is taken to get a small amount of bladder mucosa in the suture. The two sutures begin cephalad and caudally and meet in the midbladder where they are first tied separately and then together. Previously placed 3-0 Vicryl stay-sutures are tied over the first layer of closure to complete the two-layer closure. With this approach the bladder closure is watertight and completed in a timely manner. Fifty milliliters of saline is placed in the balloon to ensure that the catheter balloon remains in the bladder and does not retract into the prostatic fossa. The urethral catheter and suprapubic tube are irrigated to confirm a watertight closure and to verify that hemorrhage is minimal. A small, closed-suction drain is placed via a separate stab incision lateral to the bladder. The drain exits the skin on the opposite side of the suprapubic tube. The pelvis is irrigated with copious amounts of normal saline solution, and the rectus fascia is closed with a size 1 PDS suture on a TPI needle in a running fashion. The skin is closed with skin staples. Next, the suprapubic tube and drain are secured to the abdominal wall, and the urethral catheter is anchored to the lower extremity.

Figure 94–12 Suprapubic prostatectomy. After placement of a urethral catheter and a Malecot suprapubic tube, the cystotomy is closed in two layers using a running 2-0 Vicryl suture, enforced by tying of multiple interrupted 3-0 Vicryl stay sutures. A closed Davol suction drain is placed on one side of the bladder and exits via a separate stab incision.

Postoperative Management

In the recovery area the outputs from the pelvic drain, suprapubic tube, and urethral catheter are monitored. In addition, it is routine to verify the hematocrit. If significant hemorrhage is noted, the urethral catheter may be placed on traction so that the balloon containing 50 mL of saline can compress the bladder neck and prostatic fossa. Constant and reliable traction can be maintained by securing the catheter to the abdomen. In addition, continuous bladder irrigation should be initiated to prevent clot formation. For maximal effect the inflow should be through the urethral catheter and the outflow through the suprapubic tube. For most patients these measures are adequate and effective. However, if excessive bleeding persists after these measures, the urethral catheter can be removed in the operating suite and a cystoscopic inspection of the prostatic fossa and bladder neck can be performed to identify and fulgurate discrete bleeding sites. If marked hemorrhage should continue to persist, open re-exploration should be strongly considered.

On the evening of the day of surgery the patient is asked to perform the dorsiflexion and plantarflexion exercises 100 times per hour while awake and to perform pulmonary exercises. Effective pain management consists of intravenous morphine sulfate on an as-needed basis via a patient-controlled analgesic pump.

On the first postoperative day the patient is started on a clear liquid diet and asked to ambulate four times per day. Pulmonary exercises are continued. If the hematuria is resolved, continuous bladder irrigation can be discontinued with both urethral catheter and suprapubic tube placed to gravity drainage. Also, the balloon in the urethral catheter is partially deflated to 30 mL of saline and residual clots are removed by irrigation.

On the second postoperative day, if urine is clear, the urethral catheter may be removed and the suprapubic tube is clamped to allow a voiding trial. The patient is encouraged to ambulate and continue pulmonary exercises. When the patient tolerates a regular diet, oral analgesics can be given and parenteral narcotics discontinued. Appropriate discharge instructions are reviewed with the patient at this time in preparation for discharge on the third day after surgery. On the third postoperative day the pelvic drain is removed if the drainage is less than 75 mL/24 hr. The skin staples are removed and replaced with Steri-strips in nonobese men. The pathologic examination of the enucleated prostatic adenoma should be performed to confirm the absence of adenocarcinoma of the prostate.

On discharge from the hospital the patient is encouraged to gradually increase his activity. If the patient voids well with a minimal postvoid residual urine volume, the suprapubic tube is then removed in the clinic on the fifth day after surgery. The patient should be able to resume full activity 4 to 6 weeks postoperatively with outpatient visits at 6 weeks and 3 months.

Complications

The overall rate of morbidity and mortality associated with open prostatectomy is extremely low. Historically, excessive hemorrhage had been a major concern. But with modern surgical techniques, blood loss is now minimal and the need for a blood transfusion is uncommon (Zargooshi, 2007). In retropubic open prostatectomy, controlling the dorsal vein complex distal to the apex of the prostate and ligating the lateral pedicles to the prostate at the prostatovesical junction markedly reduces venous and arterial bleeding, respectively. Nevertheless, it may still be prudent to have one to two units of autologous blood available at the time of open prostatectomy.

Urinary extravasation can also be of concern in the immediate postoperative period; this most likely results from an incomplete closure of the prostatic capsulotomy in retropubic prostatectomy or the cystotomy in suprapubic prostatectomy. This will usually resolve spontaneously with continued catheter drainage. The drain should be left in place until urinary extravasation ceases.

After an open prostatectomy, urgency and urgency incontinence may be present for several weeks to several months, depending on the preoperative bladder status. If the condition is severe, the patient may be given an anticholinergic agent such as oxybutynin (Ditropan). Stress incontinence and total incontinence are rare. With a precise enucleation of the prostatic adenoma, risk of injury to the external sphincter mechanism is minimal. If stress incontinence does result after the procedure, the patient may benefit from transurethral collagen injections for a mild condition or an artificial urinary external sphincter when the situation is more severe.

Late urologic complications are not common. Acute cystitis rarely occurs as long as the patient voids to completion. Acute epididymitis can occur occasionally if infected urine refluxes into the ejaculatory ducts.

Erectile dysfunction occurs in 3% to 5% of patients undergoing an open prostatectomy; it is more common in older men than in younger men. Retrograde ejaculation occurs in 80% to 90% of patients after surgery. The risk of this adverse effect is reduced if the bladder neck is preserved at the time of surgery. Also, 2% to 5% of patients will develop a bladder neck contracture 6 to 12 weeks after an open prostatectomy (Tubaro et al, 2001; Varkarakis et al, 2004). This commonly occurs in men who have a relatively small opening at the bladder neck at the end of the operation. As stated earlier, for these men it may be appropriate to perform a wedge resection at the 6 o’clock position and advance the bladder mucosa into the prostatic fossa in the retropubic prostatectomy. However, if a bladder neck contracture does develop, the initial management should be dilatation with urethral sounds or a direct vision incision of the bladder neck using a Collings knife to create a 22-Fr opening.

The most common nonurologic adverse effects include deep vein thrombosis, pulmonary embolus, myocardial infarction, and a cerebrovascular event. The incidence of any one of these complications is less than 1% and the overall mortality rate resulting from this operation should approach zero (Varkarakis et al, 2004).

Summary

Open prostatectomy, whether performed via a retropubic approach or a suprapubic approach, is an excellent treatment option for (1) men with symptomatic bladder outlet obstruction due to benign prostatic hyperplasia causing a markedly enlarged prostate gland, (2) individuals with a concomitant bladder condition, such as a bladder diverticulum or large bladder calculi, and (3) patients who cannot be placed in the dorsal lithotomy position for TURP. With improved surgical technique these procedures can be routinely performed in a precise manner with minimal hemorrhage. Efficacy, in terms of durable improvement in symptom score and peak urinary flow rate, is superior than other treatment options available for the obstructing prostate gland, including TURP. Meanwhile, complications are minimal and the length of hospitalization has been markedly reduced. For most patients, the length of hospital stay is 3 days or less. Thus, for the properly selected individual, an open prostatectomy is a highly effective and well-tolerated operation.

Key Points

Roos NP, Wennberg JE, et al. Mortality and reoperation after open and transurethral resection of the prostate for benign prostatic hyperplasia. N Engl J Med. 1989;320(17):1120-1124.

Walsh PC, Oesterling JE. Improved hemostasis during simple retropubic prostatectomy. J Urol. 1990;143(6):1203-1204.

Abrams P, Schulman CC, et al. Tamsulosin, a selective alpha 1c-adrenoceptor antagonist: a randomized, controlled trial in patients with benign prostatic “obstruction” (symptomatic BPH). The European Tamsulosin Study Group. Br J Urol. 1995;76(3):325-336.

Andersen JT, Ekman P, et al. Can finasteride reverse the progress of benign prostatic hyperplasia? A two-year placebo-controlled study. The Scandinavian BPH Study Group. Urology. 1995;46(5):631-637.

Brunocilla E, Vece E, et al. Preperitoneal prosthetic mesh hernioplasty for the simultaneous repair of inguinal hernia during prostatic surgery: experience with 172 patients. Urol Int. 2005;75(1):38-42.

Campo B, Bergamaschi F, et al. Transurethral needle ablation (TUNA) of the prostate: a clinical and urodynamic evaluation. Urology. 1997;49(6):847-850.

Cornford PA, Biyani CS, et al. Daycase transurethral incision of the prostate using the holmium: YAG laser: initial experience. Br J Urol. 1997;79(3):383-384.

Cowles RS3rd, Kabalin JN, et al. A prospective randomized comparison of transurethral resection to visual laser ablation of the prostate for the treatment of benign prostatic hyperplasia. Urology. 1995;46(2):155-160.

Culp DA. Benign prostatic hyperplasia: early recognition and management. Urol Clin North Am. 1975;2(1):29-48.

Freyer PJ. One thousand cases of total enucleation of the prostate for radical cure of enlargement of that organ. BMJ. 1912;2:868.

Gacci M, Bartoletti R, et al. Urinary symptoms, quality of life and sexual function in patients with benign prostatic hypertrophy before and after prostatectomy: a prospective study. BJU Int. 2003;91(3):196-200.

Gillenwater JY, Conn RL, et al. Doxazosin for the treatment of benign prostatic hyperplasia in patients with mild to moderate essential hypertension: a double-blind, placebo- controlled, dose-response multicenter study [see comments]. J Urol. 1995;154(1):110-115.

Gilling PJ, Kennett K, et al. Holmium laser enucleation of the prostate (HoLEP) combined with transurethral tissue morcellation: an update on the early clinical experience. J Endourol. 1998;12(5):457-459.

Gormley GJ, Stoner E, et al. The effect of finasteride in men with benign prostatic hyperplasia. The Finasteride Study Group [see comments]. N Engl J Med. 1992;327(17):1185-1191.

Javle P, Blair M, et al. The role of an advanced thermotherapy device in prostatic voiding dysfunction. Br J Urol. 1996;78(3):391-397.

Kaplan SA, Santarosa RP, et al. Transurethral electrovaporization of the prostate: one-year experience. Urology. 1996;48(6):876-881.

Lepor H, Auerbach S, et al. A randomized, placebo-controlled multicenter study of the efficacy and safety of terazosin in the treatment of benign prostatic hyperplasia. J Urol. 1992;148(5):1467-1474.

Lepor H, Williford WO, et al. The efficacy of terazosin, finasteride, or both in benign prostatic hyperplasia. Veterans Affairs Cooperative Studies Benign Prostatic Hyperplasia Study Group [see comments]. N Engl J Med. 1996;335(8):533-539.

Malament M. Maximal hemostasis in suprapubic prostatectomy. Surg Gynecol Obstet. 1965;120:1307-1312.

Mariano MB, Tefilli MV, et al. Laparoscopic prostatectomy for benign prostatic hyperplasia—a six-year experience. Eur Urol. 2006;49(1):127-131. discussion 131–2

McConnell JD, Barry MJ, et al. Benign prostatic hyperplasia: diagnosis and treatment. Clinical practice guideline no. 8. Rockville (MD): U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Agency for Health Care Policy and Research, Public Health Service; 1994.

Mebust WK, Holtgrewe HL, et al. Transurethral prostatectomy: immediate and postoperative complications: a cooperative study of 13 participating institutions evaluating 3,885 patients. J Urol. 1989;141(2):243-247.

Millin R. Retropubic prostatectomy: new extravesical technique: report on 20 cases. Lancet. 1945;2:693.

Muschter R, Hofstetter A. Technique and results of interstitial laser coagulation. World J Urol. 1995;13(2):109-114.

O’Conor VJJr. An aid for hemostasis in open prostatectomy: capsular plication. J Urol. 1982;127(3):448.

Ogden CW, Reddy P, et al. Sham versus transurethral microwave thermotherapy in patients with symptoms of benign prostatic bladder outflow obstruction. Lancet. 1993;341:14-17.

Peters CA, Walsh PC. Blood transfusion and anesthetic practices in radical retropubic prostatectomy. J Urol. 1985;134(1):81-83.

Reich O, Gratzke C, et al. Techniques and long-term results of surgical procedures for BPH. Eur Urol. 2006;49(6):970-978. discussion 978

Reiner WG, Walsh PC. An anatomical approach to the surgical management of the dorsal vein and Santorini’s plexus during radical retropubic surgery. J Urol. 1979;121(2):198-200.

Roehrborn CG, Boyle P, et al. Efficacy and safety of a dual inhibitor of 5-alpha-reductase types 1 and 2 (dutasteride) in men with benign prostatic hyperplasia. Urology. 2002;60(3):434-441.

Roehrborn CG, Marks LS, et al. Efficacy and safety of dutasteride in the four-year treatment of men with benign prostatic hyperplasia. Urology. 2004;63(4):709-715.

Roehrborn CG, Oesterling JE, et al. The Hytrin Community Assessment Trial study: a one-year study of terazosin versus placebo in the treatment of men with symptomatic benign prostatic hyperplasia. HYCAT Investigator Group. Urology. 1996;47(2):159-168.

Roos NP, Wennberg JE, et al. Mortality and reoperation after open and transurethral resection of the prostate for benign prostatic hyperplasia. N Engl J Med. 1989;320(17):1120-1124.

Schlegel PN, Walsh PC. Simultaneous preperitoneal hernia repair during radical pelvic surgery. J Urol. 1987;137(6):1180-1183.

Schulman CC, Zlotta AR, et al. Transurethral needle ablation (TUNA): safety, feasibility, and tolerance of a new office procedure for treatment of benign prostatic hyperplasia. Eur Urol. 1993;24(3):415-423.

Serretta V, Morgia G, et al. Open prostatectomy for benign prostatic enlargement in southern Europe in the late 1990s: a contemporary series of 1800 interventions. Urology. 2002;60(4):623-627.

Sotelo R, Clavijo R, et al. Robotic simple prostatectomy. J Urol. 2008;179(2):513-515.

Sotelo R, Spaliviero M, et al. Laparoscopic retropubic simple prostatectomy. J Urol. 2005;173(3):757-760.

Tubaro A, Carter S, et al. A prospective study of the safety and efficacy of suprapubic transvesical prostatectomy in patients with benign prostatic hyperplasia. J Urol. 2001;166(1):172-176.

Varkarakis I, Kyriakakis Z, et al. Long-term results of open transvesical prostatectomy from a contemporary series of patients. Urology. 2004;64(2):306-310.

Walsh PC, Oesterling JE. Improved hemostasis during simple retropubic prostatectomy. J Urol. 1990;143(6):1203-1204.

Zargooshi J. Open prostatectomy for benign prostate hyperplasia: short-term outcome in 3000 consecutive patients. Prostate Cancer Prostatic Dis. 2007;10(4):374-377.