Surgical Reconstruction of Cloacal Exstrophy

The initial successful reconstruction of cloacal exstrophy was reported by Rickham (1960). Survival in the 1970s remained at about 50%; however, the institution of intensive postnatal care led to improvement in survival in the 1980s to almost 100%.

Evaluation and Management at Birth

Immediate management is directed to the medical stabilization of the infant. Complete physical examination and determination of the various anatomic defects present allow short- and long-term management strategies to be created (Table 124–4). This initial planning stage should include decisions about gender assignment. The bowel and bladder segments are kept moist with protective plastic dressings as with bladder exstrophy (Gearhart and Jeffs, 1998). Presence of neurospinal abnormalities requires immediate neurosurgical evaluation. Consultations from social work, pediatric orthopedic surgery, and other disciplines should be obtained. Evaluation of the genitalia and gender assignment should be made by a gender assignment team including a pediatric urologist, pediatric surgeon, pediatrician, pediatric endocrinologist, and child psychologist or psychiatrist. Gender assignment decisions should be made in conjunction with appropriate parental counseling and involvement. In a large medical center with experience in dealing with complex malformations, these multiple consultations should be done in a short period of time. If there are medical concerns, delayed closure after initial intestinal diversion is appropriate (Mathews et al, 1998).

Table 124–4 Modern Functional Reconstruction of Cloacal Exstrophy

| Immediate Neonatal Assessment |

| Functional Bladder Closure (Soon after Neonatal Assessment) |

| ONE-STAGE REPAIR (FEW ASSOCIATED ANOMALIES) |

| TWO-STAGE REPAIR |

| Anti-Incontinence/Reflux Procedure (age 4-5 yr) |

| Vaginal Reconstruction |

Gender Assignment

Because of the significant separation of the corpora of the penis and scrotum and the reduction in corporal size noted in boys with cloacal exstrophy, early reports had recommended universal gender reassignment of boys (46,XY) with cloacal exstrophy to functional females (Tank and Lindenaur, 1970). To this end, bilateral orchiectomy was combined with phallic reconstruction as a functional clitoris and early or delayed vaginoplasty. Reiner (2004) has reported on 29 males with cloacal exstrophy who had gender reassignment to female. Psychosexual evaluation indicated that all of these patients had a marked male shift in psychosexual development despite having no pubertal hormonal surges. A comparison of patients with cloacal exstrophy and other cloacal anomalies at the Great Ormond Street, however, indicated no difference in social or behavioral competence or psychologic problems. Gender assignment was not associated with childhood psychologic, emotional, or behavioral problems (Baker Towell and Towell, 2003). Schober and colleagues (2002), reporting on 14 children who had undergone early gender reassignment, indicated that although patients had masculine childhood behavior, they had a feminine gender identity. Currently, however, most authors recommend assigning gender that is consistent with karyotypic makeup of the individual if at all possible (Fig. 124–30). This policy can be supported by a report indicating that the histology of the testis at birth is normal (Mathews et al, 1999a). Furthermore, with evolution of techniques for phallic reconstruction, a functional and cosmetically acceptable phallus can now be constructed (Husmann et al, 1989).

Immediate Surgical Reconstruction

Cloacal exstrophy patients should undergo carefully planned and individualized reconstructions (Ricketts et al, 1991; Lund and Hendren, 1993; Mathews et al, 1998). For infants with spinal dysraphism and myelocystocele, neurosurgical consultation should be obtained and closure undertaken as soon as the infant is medically stable. After closure of the myelocystocele, long-term follow-up is mandatory to evaluate for subtle changes in the neurologic evaluation that could herald cord tethering. Symptomatic spinal cord tethering can be seen in up to 33% of children (McLaughlin et al, 1995).

Neonatal omphalocele closure is recommended to prevent untimely rupture and is typically combined with intestinal diversion. Formerly, initial attempts focused on ileostomy with resection of the hindgut remnant. Since the recognition of the metabolic changes that occur in patients with ileostomy, an attempt has always been made to use the hindgut remnant to provide additional length of bowel for fluid absorption (Husmann et al, 1989; Mathews et al, 1998). Enlargement of the hindgut remnant and increased water absorption have been noted in children who have had this segment incorporated into construction of a fecal colostomy. The hindgut segment may be anastomosed in an isoperistaltic or retroperistaltic fashion to increase motility and generate formed stool. Children who have anal stenosis and not imperforate anus may have the capability for later continence and may be treated with a pull-through procedure (Ricketts et al, 1991). If the hindgut remnant is not used for bowel reconstruction, it should be left as a mucus fistula to be used for later bladder augmentation or vaginal reconstruction (Lund and Hendren, 1993; Mathews et al, 1998). If gastrointestinal reconstruction is combined with bladder closure, approximation of the pubis, usually with osteotomies, is beneficial in reconstruction of the pelvic ring and increases the potential for successful bladder and abdominal wall closure (Mathews et al, 1998). Some authors have suggested that gastrointestinal reconstruction after initial fecal diversion be delayed for 1 to 2 years of observation (Soffer et al, 2000). After this time, radiographic evaluation is performed to determine residual colonic length. If near-normal colonic length is noted, a pull-through procedure is performed. If there is short colon but the patient is able to make solid stool, the patient may still be a candidate for pull-through procedures. Patients who are unable to make solid stool are typically managed with a permanent fecal stoma.

At the initial stage of omphalocele closure, if it is determined that bladder and abdominal wall closure may not be accomplished, the bladder halves are approximated in the midline without further dissection and the defect is converted to a bladder exstrophy (Ricketts et al, 1991; Mathews et al, 1998). This permits abdominal distention to allow enlargement of this bladder plate for later closure. If the hindgut segment is not used in the initial reconstruction of the bowel, it is left as a mucus fistula.

Urinary Reconstruction

Modern Staged Reconstruction

The staged management of the urinary tract follows that used for the management of bladder exstrophy (Gearhart and Jeffs, 1991b). Once the bladder halves have been approximated posteriorly, the lateral edges are separated from the abdominal wall and brought together in the midline. As in the patient with classic exstrophy, placement of the bladder and posterior urethra deep into the pelvis remains a key factor in the successful surgical reconstruction of the urinary tract. Inguinal hernias that are noted should be repaired at the time of closure. In genetic females and in genotypic male subjects undergoing gender reassignment, reconstruction should be performed to improve the appearance of the genitalia. Recent reports by Thomas and colleagues (2007) in a series using a staged approach found successful results in a series of seven patients all with tethered cords.

Reconstruction of the external genitalia in the immediate postnatal period is performed to make the infant appear more congruent with the gender assigned. The psychiatric studies of children who have had gender assignment have fueled interest in male gender assignment if adequate unilateral or bilateral corporal tissue is present (Reiner, 2004). Histologic studies indicate normal histology in the testes of male subjects who have had gender reassignment despite the presence of cryptorchidism (Mathews et al, 1999a). Results of phallic reconstruction in male patients with minimal or no penile tissue in the past have been disappointing. For male-to-female reassignment, initial female genital reconstruction should bring the phallic halves together in the midline as a clitoris.

However, in instances with adequate corporal tissue, either unilaterally or bilaterally, epispadias repair can be performed at around age 1 using the standards identified for the staged reconstruction. Vaginal reconstruction can be performed early in the genetic female patient. In gender-converted male patients who require reconstruction of a neovagina, delayed reconstruction is appropriate. Reconstruction may be performed by using a preserved hindgut segment or expanded perineal skin. Long-term dilatation of the neovagina may be required.

Pubic approximation permits abdominal wall closure and usually requires osteotomy and fixation with postoperative traction. External fixation and traction are typically maintained for 6 to 8 weeks to permit healing.

Role of Osteotomy

Infants who are medically stable may be considered for urinary tract reconstruction in the immediate postnatal period. Osteotomy is indicated in all children with cloacal exstrophy at the time of bladder closure because of the wide diastasis that is invariably present (Mathews et al, 1998). Osteotomy allows the pelvic ring, bladder, and abdominal wall to be closed without undue tension on the closure. Reduction in dehiscence and postoperative ventral hernias has been noted in patients treated with osteotomy. In a large series reported by Ben-Chaim and colleagues (1995c), significant complications occurred in 89% of patients who underwent closure of the cloacal exstrophy without osteotomy but in only 17% of patients who underwent osteotomy at the time of initial cloacal exstrophy closure. Interestingly, the patients who underwent osteotomy and those who did not were similar in terms of size of the omphalocele, presence of myelomeningocele, and time of primary closure. However, it is not surprising that osteotomy had no effect on eventual continence of patients with cloacal exstrophy.

Currently, combined anterior innominate and vertical iliac osteotomies are routinely used at our institution (Silver et al, 1999). This approach does not require the patient to be repositioned on the operating table before commencing bladder and abdominal wall closure. In addition, this method obviates the use of a posterior approach and any complication of the procedure related to the spinal or back closure. In a series of five patients with extreme pubic diastasis greater than 10 cm, Silver and colleagues (1999) described initial pelvic osteotomy and gradual pelvic closure of the fixator for 1 to 2 weeks, followed by abdominal wall closure and bladder closure. Closure was successful in all patients without technical problems or complications. This technique of staged pelvic closure may provide reliable initial secondary repair in patients with cloacal exstrophy in whom one-stage pelvic closure is not feasible, even with pelvic osteotomy. An interpubic stainless bar has been added to permit stabilization of the pubic approximation and maintain the reduction in diastasis (Fig. 124–31) (Mathews et al, 2005). Because of the possible asymmetry that can be noted in the pelvic bones, care must be used when performing osteotomies and fixation. In patients who have lower extremity abnormalities, providing postoperative traction can also be challenging.

Single-Stage Reconstruction

Grady and Mitchell (1999) have reported using a single-stage reconstruction in cloacal exstrophy—a procedure similar to that done for bladder exstrophy. Delay in urinary tract reconstruction has also been advised by these authors if there is a large omphalocele or other medical instability. In this situation, the conversion to a bladder exstrophy and subsequent reconstruction of the bladder and penis as a single step is performed. Among the small number of patients who have had this type of management strategy, occasional patients have been reported to be able to have voided continence. As with staged reconstruction, most patients have required augmentation cystoplasty for continence.

Techniques to Create Urinary Continence

Urinary continence is possible in most children but usually requires bladder augmentation and the use of intermittent catheterization. Multiple series by Gearhart and Jeffs (1991b), Mitchell and colleagues (1990), and Hendren (1992) have shown the applicability of modern techniques for lower tract reconstruction to help these patients achieve urinary continence. Enhancement of bladder capacity may be performed using a hindgut segment, if available; ileum; or stomach. Continence appears to be more difficult to achieve in male patients who undergo gender reassignment, and a continent stoma may be most applicable in this special group of patients (Mathews et al, 1998). In genetic female patients, successful continence has been achieved after Young-Dees-Leadbetter bladder neck reconstruction, but the vast majority of patients have required intermittent catheterization (Husmann et al, 1999). Similar findings were reported in a series by Mitchell and colleagues (1990). Husmann and colleagues (1999) reported that the success rate of Young-Dees-Leadbetter bladder neck reconstruction in the cloacal exstrophy population was closely related to the presence of coexisting neurologic abnormalities.

Urinary continence can be achieved in these individuals in many ways. An orthotopic urethra can be constructed from local tissue, vagina, ileum, stomach, or ureter. A catheterizable stoma can be constructed from ileum when enough bowel is present and fluid loss is not a problem. The bladder may be augmented with unused hindgut, ileum, or stomach. However, surgery to provide a continent urinary reservoir should be delayed until a method of evacuation can be taught and the child is old enough to participate in self-care. The choice between a catheterizable urethra and an abdominal stoma depends on the adequacy of the urethra and bladder outlet, interest and dexterity of the child, and orthopedic status regarding the spine, hip joints, braces, and ambulation. In a series by Gearhart and Jeffs (1991b) and in another series by Mitchell and colleagues (1990), multiple techniques were used to produce continence in patients with cloacal exstrophy. An innovative approach is required to find a suitable solution for each individual patient according to the patient’s bladder size and function and mental, neurologic, and orthopedic status. With the advent of modern pediatric anesthesia and intensive care, the newborn survival rate is high. Improving survivorship makes reconstructive techniques applicable in a large percentage of patients born with this condition.

Long-Term Issues in Cloacal Exstrophy

Because survival has become almost universal, the focus has changed in cloacal exstrophy to improving quality of life. Improvement in functional outcomes has become the mainstay of improving the quality of life. Patients presenting with significant neurologic defects need intensive management to provide improvement in quality of life. In this population, management of the bowel with permanent diversion and using continent catheterization channels for urinary management provide independence and promote improvement in self-esteem. When neurologic issues are minimal or absent, bowel pull-through and voided continence would be ideal. Ricketts and colleagues (1991) have presented a continence score that can be used in this group of children. Using a six-point scoring system to determine bowel and bladder continence (6 = best; 0 = worst), they evaluated 12 patients who had been managed over time. They had seven patients with a continence score of 1 (colostomy and incontinent bladder) and only one patient who had a score of 5 (enema program and a continent bladder), attesting to the difficulties presented with surgical reconstruction.

Some children have required permanent ileostomy for management of their gut. Husmann and colleagues (1989) noted that patients undergoing permanent ileostomy, in comparison with terminal colostomy, had greater initial morbidity; however, bowel adaptation appeared to occur by age 3 years with resolution of the short gut syndrome in most. If patients with terminal ileostomy were aggressively managed with hyperalimentation, growth characteristics in the two groups were similar.

Attempts at phallic reconstruction in the past had minimal success because of the diminutive nature of the corpora in boys and the wide pubic separation. Modern reconstructive surgical techniques may allow some boys to have complete phallic reconstruction performed with forearm grafts. Fertility appears to be universally compromised in boys, but girls have normal fertility and pregnancy has been reported. Girls have higher degrees of cervical prolapse when compared with their counterparts with bladder exstrophy.

Summary

Evolution in management of cloacal exstrophy has permitted near-universal survival with significant improvement in cosmetic and functional outcomes. Debate continues regarding the issue of gender reassignment, and long-term data are still accruing on the best strategy for management. Continence can be achieved with appropriate reconstruction and the use of intermittent catheterization. Despite the extensive malformations noted, many patients have gone on to live fruitful lives.

Key Points: Cloacal Exstrophy—Priorities in Management

Epispadias

Epispadias varies from a mild glanular defect in a covered penis to the penopubic variety with complete incontinence in males or females. It is most commonly noted as a component of bladder and cloacal exstrophy.

Male Epispadias

Isolated male epispadias is a rare anomaly, with a reported incidence of 1 in 117,000 males. Most male epispadias patients (about 70%) have complete epispadias with incontinence (Gearhart and Jeffs, 1998). Epispadias consists of a defect in the dorsal wall of the urethra. The normal urethra is replaced by a broad, mucosal strip lining the dorsum of the penis extending toward the bladder, with potential incompetence of the sphincter mechanism. The displaced meatus is free of deformity, and occurrence of urinary incontinence is related to the degree of the dorsally displaced urethral meatus (Gearhart and Jeffs, 1998). The displaced meatus may be found on the glans, penile shaft, or in the penopubic region. All types of epispadias are associated with varying degrees of dorsal chordee. In penopubic or subsymphyseal epispadias, the entire penile urethra is opened and the bladder outlet may be large enough to admit the examining finger, indicating obvious gross incontinence (Fig. 124–32A). To a lesser extent than those with classic bladder exstrophy, patients with epispadias have a characteristic widening of the symphysis pubis caused by outward rotation of the innominate bones. This separation of the pubis causes divergent penopubic attachments that contribute to the short, pendular penis with dorsal chordee. Therefore the penile deformity is virtually identical to that observed in bladder exstrophy. The reported male-to-female ratio of epispadias varies between 3 : 1 (Dees, 1949) and 5 : 1 (Kramer and Kelalis, 1982a).

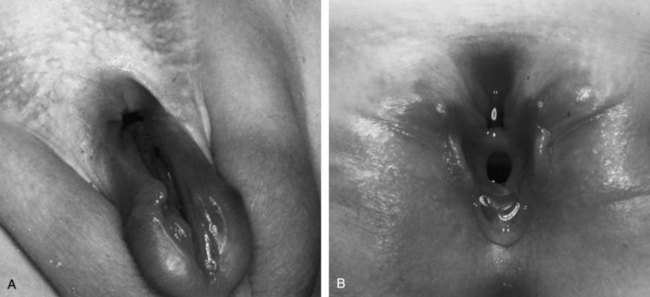

Figure 124–32 A, Three-month-old boy with complete epispadias. B, Six-month-old girl with complete female epispadias.

Kramer and Kelalis (1982a) reviewed their experience with 82 male patients with epispadias. Penopubic epispadias occurred in 49 cases, penile epispadias in 21, and glanular epispadias in 12. Urinary incontinence was observed in 46 of 49 patients with penopubic epispadias, in 15 of 21 patients with penile epispadias, and in no patient with glanular epispadias. The goals of the treatment of complete male epispadias include creation of normal urinary control and establishment of a straight, cosmetically acceptable penis of adequate length that is functional for normal sexual intercourse. It has been postulated that complete male epispadias is similar to classic bladder exstrophy except that in complete epispadias the bladder is closed and bladder closure procedures are not required.

Associated Anomalies

Anomalies associated with complete epispadias are usually confined to deformities of the external genitalia, diastasis of the pubic symphysis, and deficiency of the urinary continence mechanism. The only renal anomaly observed in 11 cases of epispadias was agenesis of the left kidney (Campbell, 1952). In a review by Arap and colleagues (1988), 1 case of renal agenesis and 1 ectopic kidney occurred among 38 patients.

The ureterovesical junction is inherently deficient in complete epispadias, and the incidence of reflux has been reported in a number of series to be between 30% and 40% (Kramer and Kelalis, 1982a; Arap et al, 1988). In a review by Ben-Chaim and colleagues (1995b) of a series of 15 patients with complete male epispadias treated at our institution, a lower rate of vesicoureteral reflux was noted compared with male patients with classic bladder exstrophy (100% vs. 82%, respectively); the rate of inguinal hernias (33%) was also significantly lower. A possible explanation for the lower incidence of reflux in complete male epispadias is that the pouch of Douglas is not as enlarged and deep. Therefore the distal ureter enters the bladder in a more oblique fashion than in classic exstrophy (Gearhart and Jeffs, 1998).

Surgical Management

The objectives of repair of penopubic epispadias include achievement of urinary continence with preservation of the upper urinary tracts and the reconstruction of cosmetically acceptable genitalia. The surgical management of incontinence in penopubic epispadias is virtually identical to that in closed bladder exstrophy.

Young (1922) reported the first cure of incontinence in a male patient with complete epispadias. Since this initial report, continence following surgical reconstruction has progressively improved (Burkholder and Williams, 1965; Kramer and Kelalis, 1982a; Arap et al, 1988; Mollard et al, 1998; Peters et al, 1988). In patients with complete epispadias and good bladder capacity, epispadias and bladder neck reconstruction can be performed in a single-stage operation. Urethroplasty formerly was performed after bladder neck reconstruction (Kramer and Kelalis, 1982a; Arap et al, 1988). However, improvements in bladder capacity in the small bladder associated with exstrophy (Gearhart and Jeffs, 1989a) and that associated with epispadias (Peters et al, 1988) have led us to perform urethroplasty and penile elongation before bladder neck reconstruction. A small, incontinent bladder with reflux is hardly an ideal situation for bladder neck reconstruction and ureteral reimplantation. Before bladder neck reconstruction there was an average increase in bladder capacity of 95 mL within 18 months after epispadias repair in the patients with an initial small bladder capacity and a continence rate of 87% after the continence procedure (Peters et al, 1988). In a series by Ben-Chaim and colleagues (1995b) composed exclusively of patients with complete male epispadias, bladder capacity increased by an average of 42 mL within 18 months after urethroplasty. Nine (82%) of 11 patients were dry day and night after an average of 9 months.

In epispadias, as in the bladder exstrophy, bladder capacity is the predominant indicator of eventual continence (Ritchey et al, 1988). Arap and colleagues (1988) reported higher continence rates in patients who had an adequate bladder capacity before bladder neck reconstruction than in those with inadequate capacity (71% vs. 20%, respectively). In addition, in Arap’s group of patients with complete epispadias, most obtained continence within 2 years, similar to results in patients with classic bladder exstrophy.

A firm intrasymphyseal band typically bridges the divergent symphysis, and an osteotomy is not usually performed. The Young-Dees-Leadbetter bladder neck plasty, Marshall-Marchetti-Krantz suspension, and ureteral reimplantation are performed when the bladder capacity reaches approximately 80 to 85 mL, which usually occurs between 4 and 5 years of age. Genital reconstruction procedures in epispadias and exstrophy are similar. The following reconstructive maneuvers must take place: release of dorsal chordee and division of the suspensory ligaments; dissection of the corpora from their attachments to the inferior pubic ramus; lengthening of the urethral groove; and lengthening of the corpora, if needed, by incision and anastomosis or grafting or by medial rotation of the ventral corpora in a more downward direction.

Urethral reconstruction in complete epispadias has been performed in many ways. A transverse island flap was used by Monfort and colleagues (1987). The urethra, once reconstructed, can be positioned between and below the corpora (Cantwell, 1895; Ransley et al, 1989; Gearhart et al, 1992, 1995c). Mitchell and Bagli (1996) reported their experience with a complete penile disassembly technique, and a multicenter experience with the technique was later reported in a total of 17 patients from four institutions (Zaontz et al, 1998). Chordee was reliably corrected, erectile function was preserved, the urethra was eventually situated in a cosmetic fashion, and satisfactory cosmesis was achieved. A recent small series by Kropp and colleagues (2008) of patients with complete epispadias showed that complications using the disassembly repair were in the acceptable range. Unlike the use of this in the exstrophy group, there was no ischemia of the glans or corpora. However, most required additional surgery because hypospadias was created in a number of patients. Ransley and colleagues reported excellent results using the modified Cantwell-Ransley procedure, saving cavernocavernostomy for patients with severe chordee and especially those in the older age group (Kajbafzadeh et al, 1995; Surer et al, 2001a). For a detailed description of the surgical reconstruction, see the previous discussion in the section on bladder exstrophy.

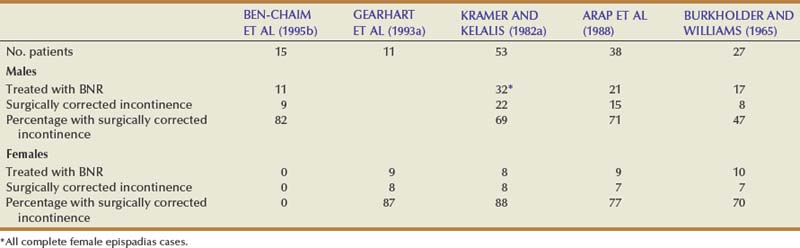

Achievement of urinary continence after epispadias repair in patients with isolated epispadias is summarized in Table 124–5. A majority of these patients underwent reconstruction by means of a Young-Dees-Leadbetter bladder neck plasty. Urinary continence was obtained in 82% of male patients (Ben-Chaim et al, 1995b). As in the exstrophy population, repair of the epispadiac deformity results in an increase of outlet resistance and possible increase in bladder capacity before bladder neck reconstruction. Although both complete epispadias and bladder exstrophy patients achieve improvement in bladder capacity after epispadias repair, the mean increase in overall capacity is higher in those with complete epispadias. This increase in bladder capacity may account for increased continence in this group compared with the classic bladder exstrophy population. Clinically, these bladders are more supple, easier to mobilize, and more amenable to bladder neck reconstruction. Ben-Chaim and colleagues (1995b) reported that the mean time to initial continence following bladder neck reconstruction was 90 days in patients with complete male epispadias compared with 110 days in those with bladder exstrophy. These results suggest that, for patients with complete epispadias, bladder capacity before reconstruction and the rate of achieving continence afterward are better than for patients with bladder exstrophy. The reason might be that the bladder is not exposed in utero and does not have any scarring from prior closure; therefore its potential for expansion is higher.

Table 124–5 Urinary Continence after Bladder Neck Reconstruction (BNR) in Patients with Complete Epispadias

It was formerly thought that the effect of urethral lengthening and prostatic enlargement might be significant in complete epispadias by increasing outlet resistance if continence was not perfect as the child became older. Earlier in a series by Arap and colleagues (1988), the establishment of continence had no relation to puberty and usually occurred within 2 years, usually preceding puberty by several years. In the series reported by Ben-Chaim and colleagues (1995b), as stated previously, all patients obtained daytime continence at a mean of 9 months after bladder neck reconstruction, and 9 (82%) of 11 patients attained total day and night continence. All patients voided spontaneously. After a mean follow-up of 7 years, all patients maintained normal upper tracts and kidney function. All of them had cosmetically pleasing genitalia, as judged by parents, patients, and physicians, and experienced normal erections. A 36-year-old patient was married and had fathered three children. Many of the patients were younger than 16 years of age and had not yet become sexually active.

Results of urethroplasty in epispadias have been reported in a number of publications (Mesrobian et al, 1986; Ransley et al, 1989; Kajbafzadeh et al, 1995; Zaontz et al, 1998). In a modern series of modified Cantwell-Ransley repairs reported by Surer and colleagues (2001a), the incidence of postoperative fistula in the 3-month period after surgery was 19%, and the incidence of urethral stricture formation was less than 10%. Catheterization and cystoscopy could easily negotiate the neourethral channel in all patients who underwent a modified Cantwell-Ransley epispadias repair. In another modern series reported by Mollard and colleagues (1998), the continence rate was 84% and the fistula rate was less than 10%. In Mollard’s series with long-term follow-up, patients had normal erections; the vast majority had regular sexual intercourse, and most had normal ejaculation or had fathered children. Most of Surer’s patients were quite young, and assessment of genital reconstruction must be deferred until these patients are sexually mature and active (2001a). In a large series of Hammouda (2003) using the penile disassembly technique, 6% of boys were made hypospadiac and 1% had partial glandar loss. Although many methods of epispadias repair exist, meticulous follow-up of the urethra, selection of patients, and surgical experience remain the milestones of success. Lastly, Ransley and colleagues (Kajbafzadeh et al, 1995) obtained good results using a modified Cantwell-Ransley repair in a large number of patients with epispadias. The fistula rate was 4%, and the urethral stricture rate was 5.3%. Baird and colleagues (2005b) reported on 129 boys who underwent a modified Cantwell-Ransley repair. Of this group, 32 had penopubic epispadias. Twenty-four were primary repairs, and 8 were secondary repairs. Urethrocutaneous fistula occurred in 13% of primary and 25% of secondary repairs. A urethral stricture occurred in one patient.

In a different approach to the treatment of incontinence associated with epispadias reported by Duffy and Ransley (1998), 12 boys aged 3 to 7 years underwent endoscopic submucosal injection of plastic microspheres. All patients had undergone a modified Cantwell-Ransley epispadias repair before injection. The procedure was performed 24 times, with a total volume of 83 mL of material injected into 59 sites in the posterior urethra. Mean follow-up was 10.8 months. Three patients (25%) were rendered completely dry, the degree of incontinence was improved in six, and there was no change in three. The authors offered this as an alternative to bladder neck reconstruction in patients with primary epispadias. Ben-Chaim and colleagues (1995a) reported that submucosal injection of collagen in the bladder neck area can have a role in improving stress incontinence when the patient with complete epispadias has incomplete urinary control or as an adjunct after bladder neck reconstruction. In a recent study by Kibar and colleagues (2009b) of complete epispadias, 1 patient out of 12 was continent after bladder neck injection.

Kramer and colleagues (Mesrobian et al, 1986) reported the success of genital reconstruction in epispadias, with good long-term follow-up ending with a straight penis angled downward in almost 70% of patients, with normal erectile function. Of this group, 80% had satisfactory sexual intercourse, and of 29 married patients, 19 had fathered children. These results were mirrored in the long-term follow-up study of Mollard and colleagues (1998).

A carefully constructed and well-planned approach to the management of urinary incontinence in genital deformities associated with complete epispadias should provide a satisfactory cosmetic appearance, normal genital function, and preservation of fertility potential in most patients.

Female Epispadias

Female epispadias is a rare congenital anomaly; it occurs in 1 of every 484,000 female patients (Gearhart and Jeffs, 1998). The authors use the classification of Davis (1928), which describes three degrees of epispadias in female patients. In the least degree of epispadias, the urethral orifice simply appears patulous. In intermediate epispadias, the urethra is dorsally split along most of the urethra. In the most severe degree of epispadias, the urethral cleft involves the entire length of the urethra and sphincteric mechanism and the patient is rendered incontinent (see Fig. 124–32B). The genital defect is characterized by a bifid clitoris. The mons is depressed in shape and coated by a smooth, glabrous area of skin. Beneath this area, there may be a moderate amount of subcutaneous tissue and fat, or the skin may be closely applied to the anterior and inferior surface of the symphysis pubis. The labia minora are usually poorly developed and terminate anteriorly at the corresponding half of the bifid clitoris, where there may be a rudiment of a preputial fold. These external appearances are most characteristic: On minimal separation of the labia, one sees the urethra, which may vary considerably, as mentioned previously. The symphysis pubis is usually closed but may be represented by a narrow fibrous band. The vagina and internal genitalia are usually normal.

Associated Anomalies

The ureterovesical junction is inherently deficient in cases of epispadias, and the ureters are often laterally placed in the bladder with a straight course so that reflux occurs. The incidence of reflux is reported to be 30% to 75% (Kramer and Kelalis, 1982b; Gearhart et al, 1993a). Because there is no outlet resistance, the bladder is small and the wall is thin. However, after urethral reconstruction, the mild urethral resistance created allows the bladder to develop an acceptable capacity for potential later bladder neck reconstruction.

Surgical Objectives

Objectives for repair of female epispadias parallel those devised for male patients: (1) achievement of urinary continence, (2) preservation of the upper urinary tracts, and (3) reconstruction of functional and cosmetically acceptable external genitalia.

Operative Techniques

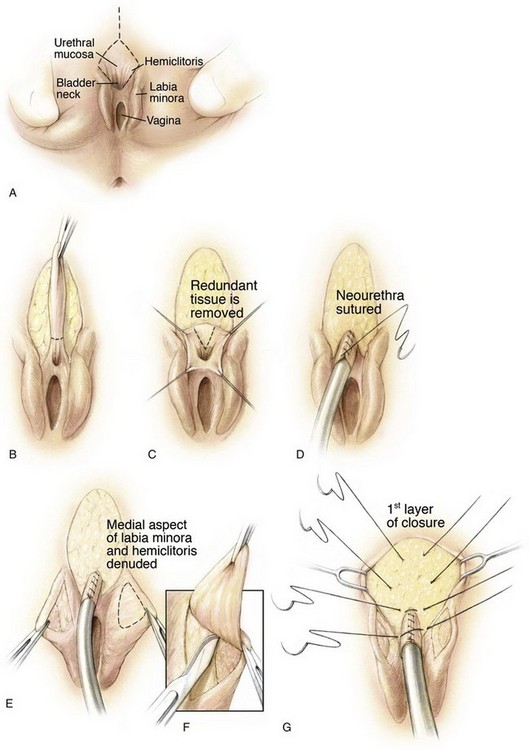

With the patient in the lithotomy position, the defect of the female epispadias with incontinence is apparent (Fig. 124–33A). The two halves of the clitoris are widely separated, and the roof of the urethra is cleft between the 9 o’clock and 3 o’clock positions. The smooth mucosa of the urethra tends to blend cephalad with the thin, hairless skin over the mons. The urethral incision is begun at the cephalad extent of the vertical incision at the base of the mons and is brought inferiorly through the full thickness of the urethral wall at the 9 o’clock and 3 o’clock positions (Fig. 124–33B). Sutures can be placed in the urethra to permit downward traction on the urethra so that the roof of the urethra is excised to a level near the bladder neck (Fig. 124–33C). Often, one finds the dissection proceeding under the symphysis. An inverting closure of the urethra is then performed over a 12- or 10-Fr Foley catheter. Suturing is begun near the bladder neck and progresses distally until closure of the neourethra is accomplished (Fig. 124–33D). Attention is then given to denuding the medial half of the bifid clitoris and the labia minora so that proper genital coaptation can be obtained.

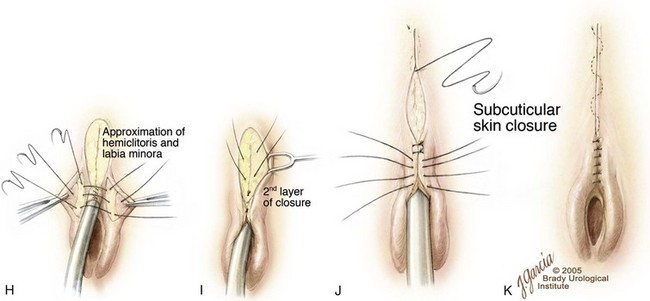

Figure 124–33 A, Typical appearance of female epispadias with initial incisions outlined. B, Excision of the glabrous skin of the mons. C, Tapering of the urethra with a dorsal resection of a wedge of tissue. D, Reconstruction of the urethra over a catheter with running suture. E and F, Medial aspect of the labia minora and clitoris. G, Initial layer of mons closure. H, Approximation of the labia minora over the urethral reconstruction. I, Second layer of mons closure. J, Creation of clitoral hood. K, Completion of mons closure.

(© Brady Urological Institute.)

After this is done, fat from the mons and subcutaneous tissue can be used to cover the suture line and obliterate the space in front of the pubic symphysis (Fig. 124–33E and F). The two halves of the clitoris and labia minora are brought together using interrupted sutures of 6-0 polyglycolic acid. The corpora may be partially detached from the anterior ramus of the pubis to aid in the urethral closure. Also, bringing these tissues together may contribute by adding resistance to the urethra. Mons closure is further aided by mobilizing subcutaneous tissue laterally and bringing it medially to fill any prior depression that remains (Fig. 124–33G). The subcutaneous layer is closed with 4-0 polyglactin suture in an interrupted fashion (Fig. 124–33H). The skin is closed with interrupted sutures of 6-0 polypropylene (Fig. 124–33I to K). A 10-Fr catheter is left indwelling for 5 to 7 days. Should the patient undergo simultaneous bladder neck reconstruction, a Foley catheter is not left in the urethra and the patient is placed in the supine position for the abdominal part of the procedure.

Achievement of a satisfactory cosmetic appearance of the external genitalia and urinary continence in the female child with epispadias represents a surgical challenge. Many operations have been reported to control continence in the epispadias group, but the results are disappointing. These procedures include transvaginal plication of the urethra and bladder neck, muscle transplantations, urethra twisting, cauterization of the urethra, bladder flap, and Marshall-Marchetti vesicourethral suspension (Stiles, 1911; Davis, 1928; Marshall et al, 1949; Gross and Kresson, 1952). These procedures may increase urethral resistance, but they do not correct incontinence or the malformed anatomy of the urethra, bladder neck, and genitalia.

The challenge of the small bladder in the female epispadias patient is comparable with a situation seen in some patients with closed bladder exstrophy. The small, incontinent bladder, with or without reflux, is hardly an ideal setting for a successful bladder neck reconstruction and ureteral reimplantation. A third of all incontinent epispadias patients have a bladder capacity of less than 60 mL, in the authors’ experience and that of Kramer and Kelalis (1982b). Bladder augmentation, injection of polytetrafluoroethylene (Teflon) in the bladder neck area, and simultaneous bladder neck reconstruction and bladder neck augmentation have been offered as a solution to this challenge. However, primary closure of the epispadiac urethra in children with closed exstrophy was found to increase bladder capacity without causing hydronephrosis, and this approach has been applied to male and female patients with epispadias (Peters et al, 1988; Gearhart and Jeffs, 1989a; Ben-Chaim et al, 1995b). Although the authors typically perform urethral and genital reconstruction at about 1 year of age, they advocate delaying bladder neck reconstruction until the child is 4 to 5 years old. Not only does this delay allow the bladder to increase in capacity, it also allows the child to accept essential instructions for toilet training, which is critical to achieving satisfactory continence in the postoperative state. Data from deJong and colleagues (2000) combined a standard exterior genitoplasty plus urethroplasty with a percutaneous bladder neck suspension. The authors felt the suspension moved the bladder neck into an intra-abdominal position. In this small series one was dry and voiding, two required bladder neck bulking agents, and one was on CIC. In another small series from India, Bhat and colleagues (2008) performed a urethroplasty and the perineal musculature was double-breasted over the urethral closure from the bladder neck distally. They report impressive results with two patients totally continent, one partially continent, and one continent after bladder neck reconstruction.

Surgical Results

The continence rate of 87.5% in our female patients is comparable with that of Hanna and Williams (1972), who found a 67% continence rate in female patients with good bladder capacity, and that of Kramer and Kelalis (1982b), who reported an 83% continence rate in patients with adequate bladder capacity. All of the authors’ patients seen for primary treatment have achieved a capacity in excess of 80 mL (see Table 124–5).

Hendren (1981) and Kramer and Kelalis (1982b) showed that genitourethral reconstruction can be accomplished with satisfactory results. At our institution, patients who underwent prior urethral and genital reconstruction had a mean bladder capacity at bladder neck reconstruction of 121 mL, making the bladder suitable for the reconstruction and eventual continence without the use of augmentation cystoplasty or need for intermittent catheterization.

The time interval to achieve continence in our patients was a mean of 18 months for those who underwent genitourethral and bladder neck reconstruction in one procedure and 23 months for those who underwent preliminary urethroplasty and genital reconstruction after bladder neck reconstruction. In a series by Klauber and Williams (1974), the mean interval to acceptable continence was 2.25 years. Also, in a series by Kramer and Kelalis (1982b), some patients became continent within a short period, whereas complete continence was delayed for several years in others. The time delay for achieving continence may represent increased pelvic muscular development, as suggested by Kramer and Kelalis (1982b). In regard to the interval to continence, no advantage appears to be gained by preliminary urethroplasty. However, the authors believe that the advantage gained by increased bladder capacity at the time of bladder neck reconstruction outweighs any advantage gained by a combined approach. In the series by Bhat and colleagues (2008) and deJong and coworkers (2000), continence rates were between 40% and 60% without further bladder neck repair or injection.

Key Points: Epispadias—Priorities in Management

Adolescents and Adults with Exstrophy

Male Concerns

The mainstay of male concerns is the length, appearance, and axis deviation (chordee) associated with exstrophy. In the typical adolescent and adult these three concerns are all intertwined. In this author’s significant experience, most boys seek consultation for all of these concerns around the time they begin showering at school. More penile length can be achieved (around an inch) by degloving the penis and cutting all scar tissue and any remnants of the suspensory ligaments. A conscious decision about the appearance must be made preoperatively because the authors have found that the placement of tissue expanders and expanding the penile skin if satisfactory is superior to full-thickness skin grafting (Fig. 124–34). If the penile skin is inferior and not a good candidate to be expanded, then full-thickness grafting is a suitable alternative (Hernandez et al, 2008). Residual dorsal chordee lasting from childhood is not uncommon because the corporal anatomy is longer on the ventrum than the dorsum, and this oftentimes remains to be adequately corrected. The use of grafts (dermal grafts, tunica vaginalis, human alloderm) can be used to lengthen the dorsal aspect of the penis. The authors’ preference is human alloderm because it is readily available, durable, and easy to use. Because of its anatomy, the penis must be opened dorsally for one half of its circumference as described by Perovic and Djinovic (2007) to both lengthen and straighten the penis. Early measurements and determinations from artificial erections must be adequate because after grafting, the artificial erections can leak saline through the suture lines and give misleading information about the adequacy of correction.

In rare cases the penis is so inadequate that a neophallus must be constructed. The authors and their pediatric plastic surgery colleagues have used a radical free-flap phalloplasty in five patients with excellent results (Gearhart and Redett, 2010).

Female Concerns

The three main female concerns are the appearance of the external genitalia, adequacy of the vaginal opening, and uterine prolapse. Although the authors correct the female external genitalia defect at birth, sometimes “touch-up” surgery needs to be performed at puberty. The three cosmetic concerns are the appearance of the lower abdominal wall, the mons veneris, and the clitorides. The authors’ group has found that in females who underwent pelvic osteotomy at the time of newborn closure, the appearance of the mons veneris is more cosmetic and in less need of repair while in the patients who do not have an osteotomy the mons is thin, inelastic, and flat appearing. To repair this in adolescence, the mons flaps are raised laterally and brought to the midline and sewn to the fascia and themselves easily. In extreme cases with an extremely scarred flat mons veneris, tissue expanders are placed laterally and gradually inflated over 6 weeks. These flaps are moved medially and used to reconstruct the mons. The pseudocapsules are rolled together in the midline to give the mons a more elevated appearance. This oftentimes involves the lower abdominal wall as well. Dissection is performed laterally, the lateral flaps are mobilized, and the midline scars are all excised to improve the appearance. This same defect is seen in the clitorides when an osteotomy is not performed at birth. They tend to be separated and scarred. Mobilizing lateral mons veneris flaps brings the clitoral halves closer to the midline and makes them easier to bring into apposition. Local estrogen cream is used three times daily for 2 weeks before any external genital surgery to soften scars, increase skin availability, and improve local vascularity. The vaginal orifice is more vertical and somewhat stenotic in exstrophy females compared with normal females. The young women appear at puberty having difficulty inserting tampons and also with intromission. These are easily repaired by an inverted U-flap of perineal skin inserted into the posterior vaginal wall, which is incised vertically (Stein et al, 1995). Beware that the cervix in exstrophy females is in the anterior vaginal wall, and sometimes opening the stenotic opening allows for uterine prolapse, which would have occurred anyway. If the patient is not sexually active, a vaginal dilator is used once daily until sexual activity occurs.

As in the genitalia and lower abdominal wall, prolapse of the uterus is more common in those who did not undergo osteotomy at birth. However, the authors have still seen it in those who did undergo pelvic closure with an osteotomy. The degree of prolapse depends on the degree of pubic bone divergence and the diameter of the opening in the levator hiatus for the vagina and rectum (Miles-Thomas et al, 2006). Because of the rarity of this condition, the average gynecologist has often never seen an adolescent or adult woman with it. The authors suspend the uterus to the sacrum with human alloderm or “pelvicoil.” The suspensory substance is sewn to the uterus from the cervix and dome of the uterus so that it can be snugly suspended to the ligaments on the front of the uterus. The authors do this prophylactically in adolescents undergoing continent diversion or other major abdominal procedures (Stein et al, 1999).

Sexual Function and Fertility in the Exstrophy Patient

Male Patient

Reconstruction of the male genitalia and preservation of fertility were not primary objectives in early surgical management of bladder exstrophy. Sporadic instances of pregnancy or the initiation of pregnancy by males with bladder exstrophy have been reported. In two large exstrophy series, male fertility was documented. Only 3 of 68 men in one study (Bennett, 1973) and 4 of 72 in another (Woodhouse et al, 1983) had successfully fathered children. In a large series of 2500 patients with exstrophy and epispadias (Shapiro et al, 1985), there were 38 males who had fathered children.

Hanna and Williams (1972) compared semen analyses in men who had undergone primary closure and ureterosigmoidostomy. A normal sperm count was found in only one of eight men after functional closure and in four of eight men with diversion. The difference in observed fertility potential is probably attributable to iatrogenic injury to the verumontanum during functional closure or bladder neck reconstruction. Retrograde ejaculation may also account for low sperm counts after functional bladder closure. In a long-term study from our institution, Ben-Chaim and colleagues (1996) found that 10 of 16 men reported they ejaculated a few cubic centimeters of volume, 3 ejaculated only a few drops, and 3 had no ejaculation. Semen analysis was obtained in four patients: Three had azoospermia, and one had oligospermia. The average ejaculated volume of the patients who had sperm counts was 0.4 mL. In another large series by Stein and colleagues (1994) from Germany, the authors found that none of the patients who had reconstruction of the external genitalia could ejaculate normally, nor had they fathered children. Five patients who did not undergo reconstruction had normal ejaculation, and two had fathered children. The conclusion was that male patients with genital reconstruction and closure of the urethra demonstrated high risk of infertility. In a recent large study of successful primary closure from a large exstrophy center by Ebert and colleagues (2008), sperm parameters were poor in 18 of 21 patients and FSH was increased in 25% of patients (Ebert et al, 2010).

Assisted reproductive techniques have been applied to the exstrophy population. Bastuba and colleagues (1993) reported pregnancies achieved with the use of assisted reproductive techniques. In a small series from the Netherlands, all patients delivered a normal infant after ICSI (D’Hauwers et al, 2008). Regardless of the method of reconstruction of the external genitalia and bladder neck, newer techniques such as gamete intrafallopian transfer (GIFT) or intracytoplasmic sperm injection (ICSI) can be used to assist these patients in their goal of pregnancy achievement. Use of GIFT or ICSI in 21 men with exstrophy led to successful pregnancy with no instances of exstrophy in any of the offspring in our exstrophy population.

Sexual function and libido in exstrophy patients are normal (Woodhouse, 1998). The erectile mechanism in patients who have undergone epispadias repair appears to be intact because 87% of boys and young men in the Hopkins series experienced erections after repair of epispadias (Surer et al, 2001a). Poor or absent ejaculation may occur after genital reconstruction. Complete absence of ejaculation is rare, but the emission that does occur may be slow and may occur for several hours. Milking the urethra in an antegrade fashion from proximal to distal has provided pregnancy in some cases (Woodhouse, 1999). In papers from both Woodhouse (1998) and Ben-Chaim and colleagues (1996) and Ebert and colleagues (2008), most patients reported satisfactory orgasm; half of the men and all of the women described intimate relationships as serious and long term. In the series by Ben-Chaim, the only patients who had no ejaculation were two patients who had undergone cystectomy. Overall, it seems from the experience in England, Germany, and the United States that most men with exstrophy achieve erection and have a reasonable sex life.

With better reconstructive techniques, patients with bladder exstrophy are living long and fruitful lives. The authors have recently reported a case of prostate cancer in a reconstructed male exstrophy and have seen two others in the recent past.

Female Patient

Further reconstruction of the female genitalia may be necessary during adolescent years. In our experience, the external genitalia are fully reconstructed at the time of initial exstrophy closure because with the use of osteotomy, a suitable mons pubis can be created and the bifid clitoris and labia can easily be brought together in the midline. Vulvoplasty is sometimes indicated in patients before they become sexually active or start using tampons. In Woodhouse’s experience (1999), most patients required vaginoplasty before intercourse could take place. Woodhouse reported successful intercourse in all of his patients, but three found it painful. Stein and colleagues (1995) from Germany reviewed a large series of patients with exstrophy and found that a cut-back vaginoplasty was required before intercourse in 23 patients. The authors have also seen several patients who have not had vulvoplasty, have two clitoral halves, have a normal sex life and normal orgasm, and desire no surgical repair of this condition.

Mathews and colleagues (2003) reported on a large series of girls and women with the exstrophy complex. All girls older than 18 years indicated that they had normal sexual desire, and many were sexually active. Mean age for commencement of sexual activity was 19.9 years. Although a few patients complained of dyspareunia, most indicated normal orgasms. Other studies by Baird and colleagues (2005a) and Ben-Chaim and colleagues (1996) confirmed the results of the larger study by Mathews. Some patients indicated that they restricted sexual activity because of the cosmetic appearance of their external genitalia. Mons plasty is therefore important to obtain a cosmetically pleasing appearance either in infancy or in adolescence because hair-bearing skin and fat should be used to cover the midline defect. As mentioned earlier, the authors perform this procedure at the time of initial closure. It certainly can be done in adolescence with the use of rhomboid flaps, as popularized by Kramer and Jackson (1986).

Obstetric Implications

Review of the literature reveals 45 women with bladder exstrophy who successfully delivered 49 normal offspring. The main complication after pregnancy was cervical and uterine prolapse, which occurred frequently (Krisiloff et al, 1978). Burbage and colleagues (1986) described 40 women ranging from 19 to 36 years of age who were treated in infancy for bladder exstrophy; 14 pregnancies in 11 of these women resulted in 9 normal deliveries, 3 spontaneous abortions, and 2 elective abortions. Uterine prolapse occurred in 7 of the 11 patients during pregnancy. All had undergone prior permanent urinary diversions. Spontaneous vaginal deliveries were performed in those women, and cesarean sections were performed in women with functional bladder closures to eliminate stress on the pelvic floor and to avoid traumatic injury to the urinary sphincter mechanism (Krisiloff et al, 1978). With modern reconstructive techniques, successful pregnancies have been reported in female patients who have undergone continent urinary diversion (Kennedy et al, 1993).

Woodhouse (1999) reported prolapse in a number of patients, and it was said to be a considerable problem to correct. Seven patients had total prolapse, one of whom had never had intercourse or a pregnancy. Woodhouse believes that prolapse may occur in up to half of patients after pregnancy. In a report from Mathews and colleagues (2003), vaginal prolapse and uterine prolapse were noted commonly and even quite early in life (mean age 16 years). Uterine suspension provided only modest success for the prevention of recurrent prolapse. Stein and colleagues (1995), in a large exstrophy series from Germany, found that uterine fixation was required to correct prolapse in 13 patients with long-term follow-up of more than 25 years. The anterior displacement of the vaginal os and the marked posterior displacement of the dorsorectalis sling with its deficient anterior component were postulated as reasons for prolapse. With the modern use of osteotomy with resultant recreation of the pelvic floor, the authors have seen less uterine prolapse in their series.

Regardless of the method of repair, the uterus must be anchored in such a way that it is fixated in the pelvis and less susceptible to prolapse. Some authors have advocated fixation of the uterus to the anterior abdominal wall in childhood; this, they say, prevents prolapse but still allows normal pregnancy. Woodhouse (1999) believed that, although prophylactic surgery may be helpful, once prolapse occurs, anterior fixation is insufficient to correct uterine prolapse in the exstrophy patient. The authors fix both sides of the uterus from the cervix to the top of the uterus bilaterally to the presacral ligaments.

Long-Term Adjustment Issues

Interest has increased in long-term adjustment issues in patients with bladder exstrophy. Children with exstrophy undergo multiple reconstructive surgeries and have potential problems with respect to urinary incontinence and sexual dysfunction. However, the ultimate outcome would be better measured by how these children adjust overall in society. The severe nature of the exstrophy disorder could predict that this birth defect could have substantial psychologic implications. Parental reaction to the child’s medical condition may change the way the parents interact with the child. Incontinence may have a negative impact on social function and self-esteem. Multiple hospitalizations may interfere with the ability to be like other children. Concerning the potential medical and psychologic implications of this anomaly, children born with exstrophy may be at increased risk for difficulties.

Formerly, there was a limited amount of information in the literature concerning this condition and its treatment and whether or not it has a deleterious effect on children and their families. Montagnino and colleagues (1998) evaluated younger children who performed more poorly and had disturbed behavior, specifically in skills related to function in school. Children who achieved continence after the age of 5 years were more likely to have problems with acting-out behavior. There were no differences in adjustment on the basis of male or female sex, bladder versus cloacal exstrophy, type of continence strategy, or gender reassignment versus no reassignment. The conclusions of this long-term study were that children with exstrophy do not have clinical psychopathology (Montagnino et al, 1998). There was acting-out behavior rather than depression or anxiety, suggesting that improved outcomes may be achieved through a focus on normal adaptation rather than potential psychologic stress. In addition, earlier achievement of continence through reconstructive efforts is potentially of psychologic benefit. This work was further supported by Catti and colleagues (2006), who found in adults that quality of life was better in those who were continent with a good body image (Catti et al, 2006).

Reiner (1999) studied 42 children with exstrophy and presented preliminary results suggesting that these patients tend to have more severe behavioral and developmental problems than children with other anomalies, significant body distortion, and self-esteem problems. Reiner has recommended early intervention with the exstrophy patient and family and continuation with long-term psychiatric support into adult life. In a study from Europe, Feitz and colleagues (1994) found a more positive picture when they evaluated 11 women and 11 men with exstrophy, of whom 9 women (82%) and 10 men (91%) did not manifest any clinical levels of psychologic stress. The authors concluded that these adults had a positive attitude toward life. With the use of structured instruments and appropriate evaluation and interviews, Reiner and Gearhart (2006) indicated that all 20 patients evaluated met criteria for at least one anxiety disorder. Older patients experienced waning of anxiety associated peer discovery of incontinence following successful surgical reconstruction, and all noted intensified sexual activity with age. New data from Reiner and colleagues (2008) of a large series of male patients found that 14% experienced suicidal ideation. As they became older, 31% experienced this phenomenon and a few attempted adolescent/early adulthood suicide. One succeeded. These findings underline the importance of screening patients as they become older for psychopathology.

In an important study by Lee and colleagues (2006), females were found to have more close friendships, fewer disadvantages in relation to healthy peers, and more partnerships than males. There were no gender differences in adjustment within educational and professional careers, which overall were good. Ebert and colleagues (2005) reviewed by questionnaire a group of 100 exstrophy adolescents. Education and social integration were high. All patients were heterosexual, and almost 50% were sexually active. Almost 60% expressed anxiety about sexual activity. The most important finding was that 94% of patients expressed an interest in psychologic assistance. These exciting new data underline the importance of early childhood intervention.

Being born with exstrophy does not result in childhood psychopathology. Children with exstrophy exhibit some tendency toward increased problems with acting out or lack of attainment of age-appropriate adaptive behavior (Montagnino et al, 1998; Reiner, 1999). Therefore all experts in childhood psychology tend to agree that counseling should come from the nursing and medical staff early in the exstrophy condition. Likewise, the patient and parents should be served by an experienced exstrophy support team, and psychologic support and counseling should be extended into adult life.

Acknowledgment

This chapter is dedicated to the memory of Dr. Jean Cendron (1923-2008) and Dr. Robert D. Jeffs (1924-2006), the pioneers of modern exstrophy surgery.

Baird AD, Frimberger D, Gearhart JP. Reconstructive lower urinary tract surgery in incontinent adolescents with exstrophy/epispadias complex. Urology. 2005;66(3):636-640.

Baird AD, Gearhart JP, Mathews RI. Applications of the modified Cantwell-Ransley epispadias repair in the exstrophy-epispadias complex. J Pediatr Urol. 2005;1(5):331-336.

Baird AD, Mathews RI, Gearhart JP. The use of combined bladder and epispadias repair in boys with classic bladder exstrophy: outcomes, complications and consequences. J Urol. 2005;174(4):1421-1424.

Borer JG, Gargollo PC, Hendren WH, et al. Early outcome following complete primary repair of bladder exstrophy in the newborn. J Urol. 2005;174:1674-1678.

Ebert A, Scheuering S, Schott G, Roesch WH. Psychosocial and psychosexual development in childhood and adolescence within the exstrophy-epispadias complex. J Urol. 2005;174(3):1094-1098.

Gearhart JP, Baird AD. The failed complete repair of bladder exstrophy: insights and outcomes. J Urol. 2005;174:1669-1672.

Gearhart JP, Ben-Chaim J, Jeffs RD, et al. Criteria for the prenatal diagnosis of classic bladder exstrophy. Obstet Gynecol. 1995;85:961.

Gearhart JP, Forschner DC, Jeffs RD, et al. A combined vertical and horizontal pelvic osteotomy approach for primary and secondary repair of bladder exstrophy. J Urol. 1996;155:689.

Gearhart JP, Peppas DS, Jeffs RD. The application of continent urinary stomas to bladder augmentation replacement in the failed exstrophy reconstruction. Br J Urol. 1995;75:87.

Grady R, Mitchell ME. Complete repair of exstrophy. J Urol. 1999;162:1415.

Hernandez D, Purves JT, Gearhart JP. Complications of surgical reconstruction of the exstrophy-epispadias complex. J Ped Urol. 2008;4:460-466.

Mathews R, Gosling JA, Gearhart JP. Ultrastructure of the bladder in classic exstrophy—correlation with development of continence. J Urol. 2004;172:1446.

Sponseller PD, Bisson LJ, Gearhart JP, et al. The anatomy of the pelvis in the exstrophy complex. J Bone Joint Surg (Am). 1995;77:177.

Stec AA, Pannu HK, Tadros YE, et al. Pelvic floor evaluation in classic bladder exstrophy using 3-dimensional computerized tomography—initial insights. J Urol. 2001;166:1444.

Ambrose SS, O’Brien DP. Surgical embryology of the exstrophy-epispadias complex. Surg Clin North Am. 1974;54:1379.

Appignani BA, Jaramillo D, Barnes PD, Poussaint TY. Dysraphic myelodysplasias associated with urogenital and anorectal anomalies: prevalence and types seen with MR imaging. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1994;163:1199.

Arap S, Giron AN. Duplicated exstrophy: report of three cases. Eur Urol. 1986;12:451.

Arap S, Nahas WC, Giron AM, et al. Continent epispadias: surgical treatment of 38 cases. J Urol. 1988;140:577.

Austin P, Holmsy YL, Gearhart JP, et al. Prenatal diagnosis of cloacal exstrophy. J Urol. 1998;160:1179.

Baird AD, Frimberger D, Gearhart JP. Reconstructive lower urinary tract surgery in incontinent adolescents with exstrophy/epispadias complex. Urology. 2005;66(3):636-640.

Baird AD, Gearhart JP, Mathews RI. Applications of the modified Cantwell-Ransley epispadias repair in the exstrophy-epispadias complex. J Pediatr Urol. 2005;1(5):331-336.

Baird AD, Mathews RI, Gearhart JP. The use of combined bladder and epispadias repair in boys with classic bladder exstrophy: outcomes, complications and consequences. J Urol. 2005;174(4):1421-1424.

Baka-Jakubiak M. Combined bladder neck, urethral and penile reconstruction in boys with exstrophy-epispadias complex. BJU Int. 2000;86:513.

Baker LA, Gearhart JP. Staged approach to bladder exstrophy and the role of osteotomy. World J Urol. 1998;16:205.

Baker LA, Jeffs RD, Gearhart JP. Urethral obstruction after primary exstrophy closure: what is the fate of the genitourinary tract? J Urol. 1999;161:618.

Baker Towell DM, Towell AD. A preliminary investigation into quality of life, psychological distress and social competence in children with cloacal exstrophy. J Urol. 2003;169:1850.

Bastuba MD, Alper MM, Oats RD. Fertility and the use of assisted reproductive techniques in the adult male exstrophy patient. Fertil Steril. 1993;60:733.

Beaudoin S, Simon L, Bargy F. Anatomical basis of the common embryological origin for epispadias and bladder or cloacal exstrophy. Surg Radiol Anat. 1997;19:11-16.

Ben-Chaim J, Jeffs RD, Peppas DS, et al. Submucosal bladder neck injections of glutaraldehyde cross linked bovine collagen for the treatment of urinary incontinence in patients with the exstrophy-epispadias complex. J Urol. 1995;154:862.

Ben-Chaim J, Jeffs RD, Reiner WG, et al. The outcome of patients with classic bladder exstrophy in adult life. J Urol. 1996;155:1251.

Ben-Chaim J, Peppas DS, Jeffs RD, Gearhart JP. Complete male epispadias: genital reconstruction achieving continence. J Urol. 1995;153:1665.

Ben-Chaim J, Peppas DS, Sponseller PD, et al. Application of osteotomy in the cloacal exstrophy patient. J Urol. 1995;154:865.

Bennett AH. Exstrophy of the bladder treated by ureterosigmoidostomies. Urology. 1973;2:165.

Bhat AL, Bhat M, Sharma R, Saxena G. Single stage perineal urethroplasty for continence in female epispadias: a preliminary report. Urology. 2008;72:300.

Bolduc S, Capolicchio G, Upadhyay J, et al. The fate of the upper urinary tract in exstrophy. J Urol. 2002;168:2579.

Borer JG, Gargollo PC, Hendren WH, et al. Early outcome following complete primary repair of bladder exstrophy in the newborn. J Urol. 2005;174:1674-1678.

Boyadjiev S, South S, Radford C, et al. Characterization of reciprocal translocation 46XY,t(8;9)(p11.2;13) in a patient with bladder exstrophy identifies CASPR3 as a candidate gene and shows duplication of the regions flanking the pericentric heterochromatin on chromosome 9 in normal population. Presented at American Society of Genetics. Toronto: October 29, 2004b.

Boyadjiev SA, Dodson JL, Radford CL, et al. Clinical and molecular characterization of the bladder exstrophy-epispadias complex: analysis of 232 families. BJU Int. 2004;94:1337.

Braga LH, Lorenzo AJ, Bägli DJ, et al. Does bilateral ureteral reimplantation at the time of primary bladder exstrophy closure (CPRE-BUR) protect the upper tracts? Abstract 54, American Academy of Pediatrics annual meeting. Boston: 2008a.

Braga LH, Lorenzo AJ, Bägli DJ, et al. Outcome analysis of isolated male epispadias: single center experience with 33 cases. J Urol. 2008;179(3):1107-1112.

Burbage KA, Hensle TW, Chambers WJ, et al. Pregnancy and sexual function in bladder exstrophy. Urology. 1986;28:12.

Burkholder GV, Williams DI. Epispadias and incontinence: surgical treatment in 27 children. J Urol. 1965;94:674.

Cadeddu JA, Benson JE, Silver RI, et al. Spinal abnormalities in classic bladder exstrophy. Br J Urol. 1997;79:975.

Caione P, Kapoza N, Lais A, et al. Female genito-urethroplasty and submucosal periurethral collagen injections as adjunctive procedures for continence in the exstrophy-epispadias complex. Br J Urol. 1993;71:350.

Caione P, Lais A, Dejenaro N, et al. Glutaraldehyde cross linked bovine collagen in the exstrophy-epispadias complex. J Urol. 1993;150:631.

Caione P, Napo S, DeCastro R. Low dose desmopressin in the treatment of nocturnal urinary incontinence in exstrophy-epispadias complex. BJU Int. 1999;84:329.

Campbell M. Epispadias: a report of 15 cases. J Urol. 1952;67:988.

Canning DA, Gearhart JP, Peppas DS, Jeffs RD. The cephalotrigonal reimplant in bladder neck reconstruction for patients with exstrophy or epispadias. J Urol. 1992;150:156.

Cantwell FV. Operative technique of epispadias by transplantation of the urethra. Ann Surg. 1895;22:689.

Catti M, Paccalin C, Rudigoz RC, Mouriquand P. Quality of life for adult women born with bladder and cloacal exstrophy: a long-term follow up. J Pediatr Urol. 2006;2(1):16-22.

Cendron J. La réconstruction vésicale. Ann Chir Infant. 1971;12:371.

Cerniglia F, Roth DA, Gonzalez ET. Covered exstrophy and visceral sequestration in a male newborn. J Urol. 1989;141:903.

Cervellione RM, Bianchi A, Fishwick J, et al. Salvage procedures to achieve continence after failed bladder exstrophy repair. J Urol. 2008:304-306.

Chan DY, Jeffs RD, Gearhart JP. Determinates of continence in the bladder exstrophy population after bladder neck reconstruction. Urology. 2001;165:1656.

Chandra S, Sharma A, Bharga S. Covered exstrophy with incomplete duplication of the bladder. Pediatr Surg Int. 1999;15:422.

Chitrit Y, Zorn B, Filidori M, et al. Cloacal exstrophy in monozygotic twins detected through antenatal ultrasound scanning. J Clin Ultrasound. 1993;21:339.

Cohen AR. The mermaid malformation: cloacal exstrophy and occult spinal dysraphism. Neurosurgery. 1991;28:834.

Cole EE, Adams MC, Brock JW, et al. Outcome of continence procedures in the pediatric patient: a single institutional experience. J Urol. 2003;170:560.

Connolly JA, Peppas DS, Jeffs RD, Gearhart JP. Prevalence in repair of inguinal hernia in children with bladder exstrophy. J Urol. 1995;154:1900.

D’elia G, Pahernik S, Fisch M, et al. Mainz Pouch II technique: 10 years’ experience. BJU Int. 2004;93:1037.

Dave S, Grover VP, Agarwala S, et al. Cystometric evaluation of reconstructed classical bladder exstrophy. BJU Int. 2001;88:403.

Davis DM. Epispadias in females and the surgical treatment. Surg Gynecol Obstet. 1928;47:600.

de Jong TP, Dik P, Klijn AJ. Female epispadias repair: a new 1-stage technique. J Urol. 2000;164(2):492-494.

Dees JE. Congenital epispadias with incontinence. J Urol. 1949;62:513.

D’Hauwers KW, Feitz WF, Kremer JA. Bladder exstrophy and male fertility: pregnancies after ICSI with ejaculated or epididymal sperm. Fertil Steril. 2008;89(2):387-389.

Diamond DA. Management of cloacal exstrophy. Dial Pediatr Urol. 1990;13:2.

Diamond DA, Bauer SB, Dinlenc C, et al. Normal urodynamics in patients with bladder exstrophy: are they achievable? J Urol. 1999;162:841.

Dick EA, de Bruyn R, Patel K, Owens CM. Spinal ultrasound in cloacal exstrophy. Clin Radiol. 2001;56:289.

Duckett JW. Use of paraexstrophy skin pedicle grafts for correction of exstrophy and epispadias repair. Birth Defects Orig Artic Ser. 1977;13:171.

Duckett JW, Gazak JM. Complications of ureterosigmoidostomy. Urol Clin North Am. 1983;10:473.

Duffy PG, Ransley PG. Endoscopic treatment of urinary incontinence in children with primary epispadias. Br J Urol. 1998;81:309-311.

Ebert A, Scheuering S, Schott G, Roesch WH. Psychosocial and psychosexual development in childhood and adolescence within the exstrophy-epispadias complex. J Urol. 2005;174(3):1094-1098.

Ebert AK, Bals-Pratsch M, Seifert B, et al. Genital and reproductive function in males after functional reconstruction of the exstrophy-epispadias complex—long-term results. Urology. 2008;72(3):566-569.

Ebert AK, Schott G, Bals-Pratsch M, et al. Long-term follow-up of male patients after reconstruction of the bladder-exstrophy-epispadias complex: psychosocial status, continence, renal and genital function. J Pediatr Urol. 2010;6:6.

El-Sherbiny MT, Hafez AT. Complete repair of bladder exstrophy in boys: can hypospadias be avoided? Eur Urol. 2005;47(5):691-694.

Feitz WF, Vangrunsven VJ, Froeling FM. Outcome analysis of the psychosexual and socioeconomic development of adults born with bladder exstrophy. J Urol. 1994;152:1417.

Feneley M, Gearhart JP. A history of bladder and cloacal exstrophy [abstract]. American Urological Association Annual Meeting. Anaheim (CA): May 1, 2000.

Franco I, Culligan M, Reed EF, et al. The importance of catheter size in achievement of urinary continence in patients undergoing a Young-Dees-Leadbetter procedure. J Urol. 1994;152:710.

Frimberger D, Lakshmanan Y, Gearhart JP. Continent urinary diversions in the exstrophy complex: why do they fail? J Urol. 2003;170:1338.

Gambhir L, Höller T, Müller M, et al. Epidemiological survey of 214 families with bladder exstrophy-epispadias complex. J Urol. 2008;179:1539-1543.

Gargollo PC, Borer JG, Retik AB, et al. Magnetic resonance imaging of pelvic musculoskeletal and genitourinary anatomy in patients before and after complete primary repair of bladder exstrophy. J Urol. 2005;174(4 Pt. 2):1559-1566.

Gearhart JP. Failed bladder exstrophy closure: evaluation and management. Urol Clin North Am. 1991;18:687.

Gearhart JP. Bladder exstrophy, epispadias and other abnormalities. In: Walsh PC, Retik AB, Vaughan ED, et al, editors. Campbell’s urology. 8th ed. Philadelphia: Saunders; 2002:2136.

Gearhart JP, Baird AD. The failed complete repair of bladder exstrophy: insights and outcomes. Presented at the American Academy of Pediatrics Urology Section. San Francisco: October 9, 2004.

Gearhart JP, Baird AD. The failed complete repair of bladder exstrophy: insights and outcomes. J Urol. 2005;174:1669-1672.

Gearhart JP, Baird AD, Mathews RI. Applications of the modified Cantwell-Ransley repair in the exstrophy-epispadias complex. Presented at the European Society of Pediatric Urology. Regensberg (Germany): April 13, 2004.

Gearhart JP, Baird A, Nelson CP. Results of bladder neck reconstruction after newborn complete primary repair of exstrophy. J Urol. 2007;178:1619-1622.

Gearhart JP, Ben-Chaim J, Jeffs RD, et al. Criteria for the prenatal diagnosis of classic bladder exstrophy. Obstet Gynecol. 1995;85:961.

Gearhart JP, Ben-Chaim J, Scortino C. The multiple reoperative bladder exstrophy closure: what affects the potential of the bladder? Urology. 1996;47:240.

Gearhart JP, Canning DA, Jeffs RD. Failed bladder neck reconstruction: options for management. J Urol. 1991;146:1082.

Gearhart JP, Forschner DC, Jeffs RD, et al. A combined vertical and horizontal pelvic osteotomy approach for primary and secondary repair of bladder exstrophy. J Urol. 1996;155:689.

Gearhart JP, Jeffs RD. The use of parenteral testosterone therapy in genital reconstructive surgery. J Urol. 1987;138:1077.

Gearhart JP, Jeffs RD. Bladder exstrophy: increase in capacity following epispadias repair. J Urol. 1989;142:525.

Gearhart JP, Jeffs RD. State of the art reconstructive surgery for bladder exstrophy at the Johns Hopkins Hospital. Am J Dis Child. 1989;143:1475.

Gearhart JP, Jeffs RD. Management of the failed exstrophy closure. J Urol. 1991;146:610.

Gearhart JP, Jeffs RD. Techniques to create urinary continence in cloacal exstrophy patients. J Urol. 1991;146:616.

Gearhart JP, Jeffs RD. The bladder exstrophy-epispadias complex. In: Walsh PC, et al, editors. Campbell’s urology. 7th ed. Philadelphia: WB Saunders; 1998:1939.

Gearhart JP, Leonard MP, Burgers JK. Cantwell-Ransley technique for repair of epispadias. J Urol. 1992;148:851.

Gearhart JP, Mathews RI, Taylor S, et al. Combined bladder closure in epispadias repair and the reconstruction of bladder exstrophy. J Urol. 1998;160:1182.

Gearhart JP, Peppas DS, Jeffs RD. Complete genitourinary reconstruction in female epispadias. J Urol. 1993;149:1110.

Gearhart JP, Peppas DS, Jeffs RD. Failed exstrophy closure: strategy for management. Br J Urol. 1993;71:217.

Gearhart JP, Peppas DS, Jeffs RD. The application of continent urinary stomas to bladder augmentation replacement in the failed exstrophy reconstruction. Br J Urol. 1995;75:87.

Gearhart JP, Redett R. The use of free flap phalloplasty in the exstrophy-epispadias population, 2010. [submitted for publication]

Gearhart JP, Scortino C, Ben-Chaim J. The Cantwell-Ransley repair in exstrophy and epispadias: lessons learned. Urology. 1995;46:92.

Gearhart JP, Yang A, Leonard MP, et al. Prostate size and configuration in adult patients with bladder exstrophy. J Urol. 1993;149:308.

Gobet R, Weber D, Renzulli P, Kellenberger C. Long-term follow up (37-69 years) of patients with bladder exstrophy treated with ureterosigmoidostomy: uro-nephrological outcome. J Pediatr Urol. 2009;5:190.

Grady R, Mitchell ME. Complete repair of exstrophy. J Urol. 1999;162:1415.

Grady RW. Technique for repair of bladder exstrophy and epispadias: long-term follow up. New Orleans: American Academy of Pediatrics; 2003. November 1

Greene WB, Dias LS, Lindseth RE, Torch MA. Musculoskeletal problems in association with cloacal exstrophy. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1991;73(4):551-560.