chapter 130 Hypospadias

Hypospadias is believed to result from arrested penile development, leaving a proximal urethral meatus. It has challenged generations of reconstructive surgeons trying to extend the urethra while straightening associated penile curvature and managing ventral skin deficiency, with the goal of restoring as normal function and appearance as is possible. The current understanding of the etiology of hypospadias and current methods for its surgical correction are discussed in this chapter.

An emphasis is given to those procedures most commonly used today, and this selection inevitably omits some techniques that a minority of surgeons prefers. For example, meatoplasty and glansplasty (MAGPI) and Mathieu flip-flap are not discussed in detail, but technical aspects of these procedures have not significantly changed since their description in prior editions of this textbook.

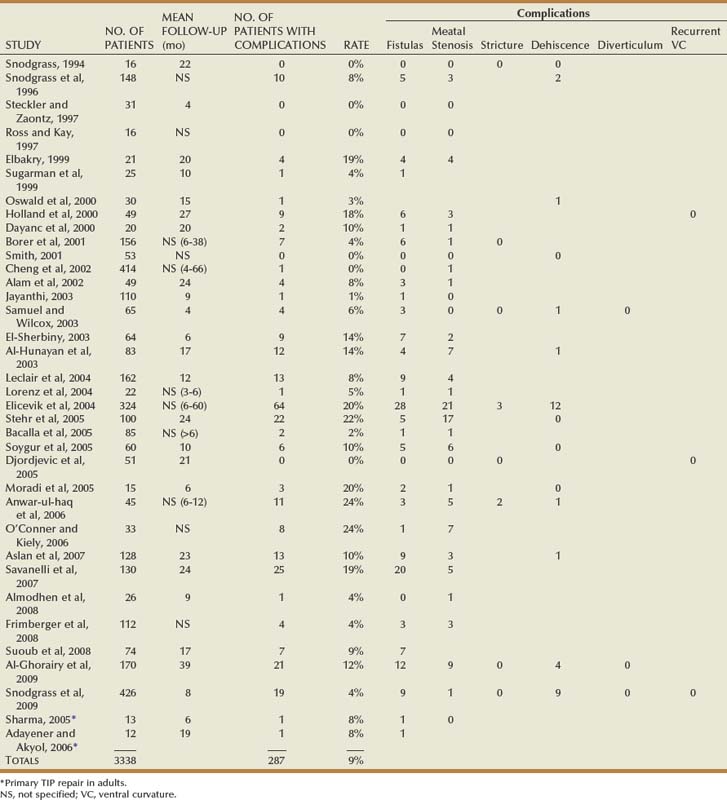

Objective outcomes data are provided for described techniques to the extent available, usually summarized in the tables. Total complications may exceed the number of patients with complications due to multiple problems in some patients. Numbers appear only in columns designating outcomes specifically mentioned by authors.

Embryology of Penile Development

The external genital anlage is initially indifferent and develops the female phenotype unless exposed to androgens during the critical gestational time period of 8 to 12 weeks. 5α-Reductase type 2 is highly expressed in mesenchymal stroma while the androgen receptor is concentrated in epithelium of the urethral plate (Kim et al, 2002). Dihydrotestosterone derived from 5α-reduced testosterone mediates the key steps in penis formation: elongation of the genital tubercle and fusion of urethral folds.

The urethral plate develops as an extension of endoderm from the cloaca along the ventral midline of the genital tubercle. Proliferating mesenchyme to either side creates urethral folds and establishes the urethral groove. Fusion of the urethral folds begins proximally and continues distally at least to the glans. Two theories are proposed for glanular urethra development: ectodermal ingrowth cannulating the glans to the urethral plate (Glenister, 1954) versus urethral plate tubularization to the tip of the glans (Kurzrock et al, 1999).

Embryo studies suggest the penis initially exhibits ventral curvature (VC) during formation, which can persist in hypospadias when normal development arrests (Kaplan and Lamm, 1975). This VC originally was ascribed to fibrous tissue bands. However, histology from both embryos and resected surgical specimens demonstrate well-vascularized tissues without fibrosis (Baskin et al, 1998; Snodgrass et al, 2000).

Preputial development begins with a cellular lamella oriented dorsally at the coronal sulcus, with ventral fusion into the frenulum delayed until after urethral formation is completed.

Neither the molecular mechanisms involved in normal penis development nor those disturbances resulting in hypospadias are currently known. In mice, Sonic hedgehog (Shh) expressed by distal urethral plate epithelium is needed for genital tubercle outgrowth, with targeted deletion resulting in penile and clitoral agenesis (Haraguchi et al, 2001). Shh regulates fibroblastic growth factor-8 (fgf8), also known as androgen-induced growth factor, which upregulates expression of fgf10 involved in glans morphogenesis. Fgf10 also is expressed in midline mesenchyme during urethral fold fusion (Haraguchi et al, 2000), and deficient mutant mice exhibit a hypospadias-like phenotype that Yucel and associates (2004) believe indicates its crucial role in distal urethral plate tubularization. Fgf receptor 2 (Fgfr2) similarly is expressed in the urethral plate and prepuce in mice, and mice lacking it manifest proximal hypospadias (Petiot et al, 2005). Androgen receptor antagonists result in loss of Fgf10 and Fgfr2 expression in the urethra and hypospadias phenotype, indicating these genes are downstream targets involved in urethral formation (Petiot et al, 2005). The B-subclass of cell-surface Ehp and ephrin molecules also plays an important role in murine urethral formation, with heterozygous mutant males demonstrating perineal hypospadias (Yucel et al, 2007).

However, extrapolation of these findings in mice to human development is currently uncertain. Although Baskin and coworkers (2004) state the murine urethra tubularizes proximally to distally by urethral fold fusion similar to humans, others describe canalization of the urethral plate without fusion of urethral folds in rats and mice (Uda et al, 2004).

Etiology

The underlying cause for nonsyndromic hypospadias in most individual cases is unknown. Based on knowledge of normal penis formation and the presumption that hypospadias represents arrested development, several causes may exist.

Genetic Factors

Familial aggregation is found in 4% to 10% of hypospadias cases, including first-, second-, and third-degree relatives (Calzolari et al, 1986; Harris and Beaty, 1993; Fredell et al, 2002; Schnack et al, 2008). A recent national registration-based study from Denmark (Schnack et al, 2008) included 1.2 million males with 5380 hypospadias cases, reporting hypospadias equally transmitted through maternal and paternal sides of the family, with recurrence risk ratios similar for twin brothers, brothers, and sons. Difficulties in establishing recurrence risks include heterogeneity in the severity of hypospadias in probands, reliance on family histories introducing recall bias, and inclusion of patients with unrecognized syndromal hypospadias (Harris and Beaty, 1993; Schnack et al, 2008). Despite these limitations, a consistent conclusion is that familial aggregation is best explained by genetic factors rather than environmental exposure (Calzolari et al, 1986; Stoll et al, 1990; Schnack et al, 2008).

Endocrinopathies

The pivotal role of androgens in normal penis development suggests endocrinopathies impacting hormone production or action may underlie hypospadias. Leydig cell dysfunction was implicated by findings of elevated basal luteinizing hormone and reduced testosterone response to human chorionic gonadotropin stimulation in prepubertal boys with hypospadias versus controls (Nonomura et al, 1984). Defects in the testosterone biosynthetic pathway, specifically, impaired 3β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase alone or with impaired 17,20-lyase or 17α-hydroxylase activity, were reported in proximal hypospadias (Aaronson et al, 1997) but not confirmed in subsequent studies (Feyaerts et al, 2002; Holmes et al, 2004). Although enzymatic assays for 5α-reductase type 2 activity in isolated hypospadias are normal, mutations in its coding gene SRD5A2 on chromosome 2 were reported in 9% of patients with hypospadias not found in controls (Silver and Russell, 1999). Androgen receptor gene mutations are considered a rare cause of hypospadias (Batch et al, 1993; Hiort et al, 1994; Allera et al, 1995; Sutherland et al, 1996) but were not detected by others (Feyaerts et al, 2002).

Problems linking disturbed androgen activity to hypospadias were summarized by Holmes and associates (2004): little evidence has been found to suggest that nonsyndromic hypospadias without other genital anomalies is associated with defects in testosterone production, its conversion to dihydrotestosterone, or androgen receptor activity. Furthermore, the autosomal recessive pattern of inheritance characterizing steroidogenic enzyme disorders does not correlate with the genetics of hypospadias.

Gene Mutations

Murine studies indicating androgen receptor activity regulates Fgf8, Fgf10, and Fgfr2 involved in urethral development have led to screening for defects in these candidate genes in patients with hypospadias. Among cases of nonsyndromic familial hypospadias variants have been found in FGF8 and FGFR2 not seen in normal controls (Beleza-Meireles et al, 2007a).

Estrogens play a role in male development, with specific nuclear estrogen receptors, predominantly ER2, found in proximity to the androgen receptor. Variants of ER2 influence serum testosterone levels and have been described in patients with hypospadias (Beleza-Meireles et al, 2007b). Further evidence implicating estrogen-related events in urethral maldevelopment was the finding that several estrogen-responsive genes are upregulated in hypospadias patients, including ACT3, Cyr61, CTGF, and CADD45β (Wang et al, 2007). Polymorphisms of ACT3 were subsequently reported associated with hypospadias, as were less common mutations (Beleza-Meireles et al, 2008).

Endocrine Disruptors

A hypothesis that natural or synthetic compounds exerting estrogen-like and/or antiandrogen effects could result in hypospadias potentially is supported by several observations. First are reports that the incidence of hypospadias is increasing in Western nations where exposure to industrial compounds is presumed widespread. In addition, pregnant animals exposed to various chemicals in pesticides exerting estrogen-like or antiandrogen effects produce male offspring with urogenital anomalies, including hypospadias (Gray et al, 2004). Similarly, an increased risk for hypospadias has been identified in males after assisted reproduction, possibly attributable to progesterone administered to mothers. Finally, there is recognition that the estrogen receptor influences androgen activity as mentioned earlier, suggesting exposure to estrogen-like compounds may explain abnormal masculinization in the absence of demonstrated defects in testosterone production, 5α-reductase type 2 activity, or the androgen receptor.

However, although human penis development is potentially vulnerable to endocrine disruption, to date xenobiotics have not been linked to hypospadias (Baskin et al, 2001; Safe, 2005). Furthermore, the reported increase in hypospadias that suggests environmental endocrine disturbance has been challenged by recent epidemiologic studies (see later).

Syndromes with Hypospadias

Nearly 200 syndromes are associated with hypospadias (Edery, 2007).

Smith-Lemli-Opitz syndrome results from autosomal recessive mutation of the DHCR7 gene on chromosome 11q13 coding for 7-dehydrocholesterol reductase. Affected individuals have mental retardation, facial dysmorphism, microcephaly, and syndactyly. DHCR7 regulates Sonic hedgehog signaling, and so association of this syndrome with hypospadias potentially links to observations in mice regarding the role of Shh in penis development.

Deletion in chromosome 11q13 results in WAGR syndrome (Wilms tumor, Aniridia, Genital anomalies, mental Retardation), associated with hypospadias due to altered WT1 gene activity. One study screening for WT1 gene defects in boys with nonsyndromic hypospadias reported no mutations (Nordenskjold et al, 1999).

Hand-foot-genital syndrome is an extremely rare autosomal dominant condition due to mutations in HOXA13 on chromosome 7p14-15, resulting in bilateral thumb and great toe hypoplasia. Hypospadias in mice mutant for Hoxa13 also have loss of Fgf8 and bone morphogenetic protein-7 in the urethral plate (Beleza-Meireles et al, 2007a).

Opitz G syndrome (Opitz G/BBB syndrome) occurs from X-linked mutations in midline 1 gene or autosomal dominant deletions in chromosome 22q11. The resultant phenotype includes hypertelorism, tracheoesophageal defects, cleft lip/palate, and mild mental retardation as well as hypospadias.

Wolf-Hirschhorn syndrome derives from deletions in chromosome 4p, resulting in mental retardation, seizures, abnormal facies, and midline defects, including hypospadias.

13q deletion syndrome is characterized by mental retardation, facial dysmorphia, imperforate anus, and hypospadias with penoscrotal transposition. The critical region mediating anorectal and genital anomalies has been localized to 13q33.1-34, containing 20 annotated genes including EFNB2 (Garcia et al, 2006). Partial loss of ephrin B-2 function altering ephrin signaling in mice is associated with hypospadias, as discussed earlier.

Epidemiology

Prevalence

In the 1800s both Bouisson and Rennes reported that hypospadias occurred in 1 of 300 males (Beck, 1917). Data from birth registries in the United States during the late 1960s demonstrated a similar incidence (Paulozzi et al, 1997). Subsequent studies in the 1970s and 1980s indicated an apparent doubling in hypospadias occurrence in the United States, Hungary, and England, with upward trends in Denmark, Norway, and Sweden (Paulozzi et al, 1997; Aho et al, 2000a; Toppari et al, 2001). A simultaneous increase in the ratio of severe to mild forms of the condition in the Metropolitan Atlanta Congenital Defects Program suggested the increase was due to growing incidence rather than to more frequent reporting of distal cases (Paulozzi et al, 1997). Together these data from national birth registries have been taken as evidence for the influence of environmental toxins.

However, a review of surgically treated cases versus live births in Finland from 1970 to 1986 found prevalence of hypospadias unchanged despite the apparent increase noted in the national malformation registry (Aho et al, 2000a). Further investigation suggested hypospadias was previously underreported in the Finnish national malformation registry, as well as in Swedish and Danish registries (Kallen et al, 1986). Therefore, the apparent increase in hypospadias rate in these countries may only indicate changes in reporting.

In addition, various national databases have differences in reporting requirements. For example, in Australia and Japan only cases with the urethral opening on the penile shaft, scrotum, or perineum are registered, omitting the more common coronal and glanular forms (Toppari et al, 2001). Similarly, a comparison between surgical registries and the National Congenital Anomaly System in England found significant disparity in hypospadias rates attributed to a decision in 1990 to exclude reporting of distal cases (Nelson et al, 2007). Consequently, data from such registries cannot be used to accurately determine either incidence of hypospadias or geographic variations in its occurrence.

Other Associations

Placental dysfunction in early pregnancy has been implicated in risk for offspring with hypospadias, given its role in hormone production. Significant associations have been found to low birth weight (<10th percentile), preterm birth (<37 weeks), prepregnancy maternal obesity and diabetes, and maternal hypertension (Porter et al, 2005; Nordenskjold and Frisen, 2007; Akre et al, 2008). Both decreased (<24 years) and increased (>40 years) maternal age have been reported (Porter et al, 2005; Akre et al, 2008). Males have greater risk when paired with another male, versus female, twin, but the observation that twin pregnancy is associated with hypospadias may be explained by low birth weight (Nordenskjold and Frisen, 2007).

Assisted reproduction is associated with an increased hypospadias risk, which has been attributed to hormonal manipulations during and after the procedures (Macnab and Zouves, 1991; Silver et al, 1999), as well as paternal subfertility and twin pregnancy (Wennerholm et al, 2000).

Diagnosis

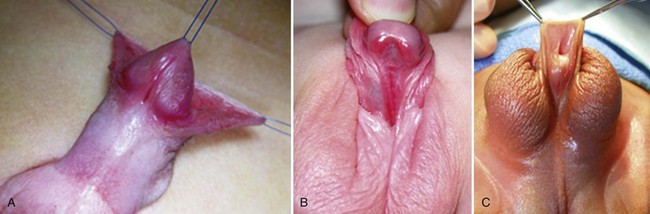

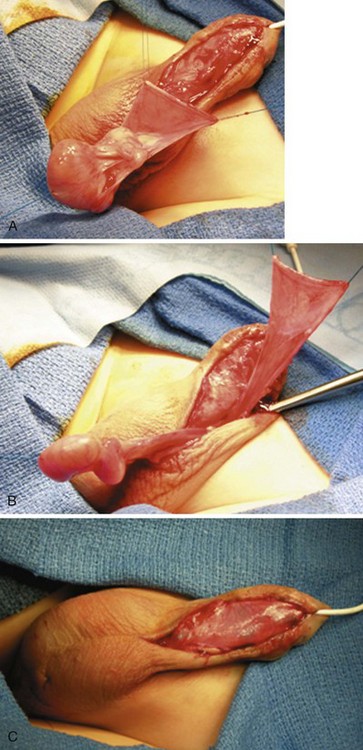

Hypospadias is diagnosed by physical examination, first suspected by the ventrally deficient prepuce and confirmed by the proximal meatus (Fig. 130–1). Other abnormal ventral findings potentially include downward glans tilt, deviation of the median penile raphe, VC, scrotal encroachment onto the penile shaft, midline scrotal cleft, and penoscrotal transposition.

Figure 130–1 Spectrum of hypospadias. A, Coronal hypospadias. B, Penoscrotal hypospadias. C, Scrotal hypospadias with scrotal transposition.

A variant subset has a normally formed foreskin concealing a glanular to distal shaft hypospadias termed megameatus intact prepuce (MIP) (Fig. 130–2). Diagnosis is made after elective neonatal circumcision or in later childhood when the foreskin retracts.

Figure 130–2 Megameatus intact prepuce hypospadias variant. A, Apparently normal penis with complete foreskin. B, Foreskin retracted, revealing coronal hypospadias.

Patients with ventrally deficient foreskins but a normally located urethral meatus are diagnosed as having chordee without hypospadias. The term implies ventral penile curvature, although, in the majority, apparent downward bending is corrected by simply degloving the ventral skin. This categorization has included patients with a glanular meatus but deficient corpus spongiosum and thin distal urethra that others consider hypospadias variants. To end confusion, boys with a hooded prepuce and bending should be diagnosed with congenital ventral curvature if the urethra is grossly normal or otherwise with hypospadias (Snodgrass, 2008).

Associated Anomalies

Cryptorchidism

Retrospective chart reviews (Kaefer et al, 1999; Wu et al, 2002) and a case-control study from the Danish National Patient Register (Weidner et al, 1999) report that approximately 7% of hypospadias patients also have cryptorchidism. In a series of 356 patients with hypospadias the incidence of cryptorchidism was 3.4% of 88 with distal versus 10% of 234 with proximal hypospadias (Wu et al, 2002).

Prostatic Utricle

An enlarged utricle sometimes hinders catheter placement during urethroplasty. After excluding patients with a disorder of sex development (DSD), urethrography demonstrates that enlarged utricles are uncommon in penile shaft hypospadias, with increasing incidence as severity progresses from penoscrotal to perineal cases (Devine et al, 1980; Ikoma et al, 1985).

Disorders of Sex Development

Although hypospadias is considered arrested masculinization, by convention it is distinguished from DSD. As discussed earlier, defects in testosterone production, its conversion to dihydrotestosterone, or androgen receptor activity that characterizes various disorders of sexual differentiation are uncommonly detected in isolated hypospadias.

The simultaneous occurrence of hypospadias with cryptorchidism increases the likelihood for DSD. Overall reported incidence in patients considered to have a male-appearing phenotype ranges from 0% to 30% and is greater with increasing severity of hypospadias and nonpalpable testes (Rajfer and Walsh, 1976; Kaefer et al, 1999; McAleer and Kaplan, 2001; Cox et al, 2008). Kaefer and colleagues reported DSD in approximately 50% of patients with a nonpalpable testis and hypospadias.

The most frequent finding is mixed gonadal dysgenesis, followed by ovotesticular disordered sexual differentiation. Incomplete androgen insensitivity, 5α-reductase type 2 deficiency, and testicular dysgenesis have also been reported. However, likely differences in defining male appearance versus ambiguity and failure to perform uniform genetic, biochemical, and radiologic evaluation in hypospadias patients with cryptorchidism make determination of the incidence of DSD uncertain.

Coexistence of hypospadias and cryptorchidism can be explained by other associations than DSD. For example, a case-control study examining risk factors independently for the two conditions within the same nationwide cohort in Sweden found low birth weight and prematurity positively correlated with each (Akre et al, 1999).

Malformation Syndromes

Hypospadias most often occurs in infants without additional known medical conditions. The finding of other anomalies increases the likelihood that hypospadias is part of a malformation syndrome. From the description of various syndromes just given these include developmental delay, facial dysmorphy, anorectal malformations, and other genital anomalies, including penoscrotal transposition and cryptorchidism.

Key Points: Penile Development

Preoperative Evaluation and Management

Karyotyping

A karyotype may help categorize hypospadias as syndromic when there are other nongenital anomalies, especially developmental delay, dysmorphic facies, and/or anorectal or scrotal malformations. It may also detect gonadal DSD, especially when there is also cryptorchidism. The role for karyotyping in isolated hypospadias, even proximal cases, is unclear because most reports concern hypospadias associated with cryptorchidism (Rajfer and Walsh, 1976; Kaefer et al, 1999; McAleer and Kaplan, 2001; Cox et al, 2008) or do not state the severity of isolated hypospadias (Moreno-Garcia and Miranda, 2002).

Radiologic Studies

No prospective studies report the incidence of radiologically detected urinary tract anomalies associated with hypospadias. Initial retrospective reviews concerned intravenous pyelography, and of these the largest series found upper tract anomalies are not increased with nonsyndromic hypospadias (McArdle and Lebowitz, 1975; Lutzker et al, 1977; Cerasaro et al, 1986). Routine voiding cystourethrography to demonstrate an enlarged utricle is not necessary, because the most common clinical manifestation is difficult catheterization that can be managed intraoperatively. Imaging can be reserved for screening patients with suspected syndromic hypospadias or DSD.

Timing of Surgery

There are no data regarding optimal timing for hypospadias surgery in children, and so guidelines are derived from expert opinion. The 1996 action committee for the American Academy of Pediatrics Section on Urology reviewed psychological factors, anesthetic considerations, and technical aspects of hypospadias repair before recommending surgery be performed between 6 and 12 months, assuming the surgeon, anesthesiologist, and facility were experienced in the care of infants (American Academy of Pediatrics, 1996). Same-day surgery can be performed after 50 gestational weeks in otherwise healthy boys, leading the author to routinely recommend repair at 3 months of age or older for distal hypospadias and selected proximal cases with an apparently normal-sized phallus. Infants with proximal hypospadias and a small-appearing glans are reassessed at 3 months and then administered hormonal stimulation, as discussed later, before surgery at approximately 6 months of age.

Optimal timing for surgery in children presenting at an older age is uncertain. From 18 months to approximately 3 years of age has been described as a difficult period for hospitalization, leading to a recommendation that repair be postponed to age greater than 3 years (Manzoni et al, 2004). However, the American Academy of Pediatrics action committee observed that surgery from 30 to 65 months of age may increase the child’s anxiety for physical injury. One study compared health-related quality of life assessment after hypospadias surgery done at less than 18 months of age versus more than 18 months of age and found no differences related to age at operation (Weber et al, 2008). Preoperative sedatives, minimal separation from family, same-day surgery, anesthetic blocks that reduce early postoperative pain, dressings that fall off spontaneously, and urinary diversion into diapers all may reduce psychological stress from hypospadias repair.

Preoperative Hormonal Stimulation

Androgenic stimulation has been advocated to increase penile size, reduce VC, and improve vascularity. Although several reports involving small numbers of patients with varied severity of hypospadias document increased penile size, glans circumference, and/or transverse length of the inner prepuce, no prospective randomized trial has determined that hormonal therapy favorably impacts objective surgical outcomes. Furthermore, no available data establish mean and standard deviations for normal glans size in children of varying ages.

One reported regimen is intramuscular testosterone enanthate 2 mg/kg given 5 and 2 weeks preoperatively (Gearhart and Jeffs, 1987; Luo et al, 2003). A comparison between a mixture of testosterone propionate and enanthate providing a dose of 2 mg/kg/wk administered twice daily topically or intramuscularly weekly found no differences in response regarding penile length or diameter. Elevated serum levels greater than 10 ng/mL only were noted after topical therapy, possibly from excessive application (Chalapathi et al, 2003).

Reported mean increases in penile length range from approximately 0.5 to nearly 3 cm, with partial to complete loss of these gains by 3 to 12 months after stimulation (Gearhart and Jeffs, 1987; Davits et al, 1993; Chalapathi et al, 2003). Side effects include pubic hair growth and aggressive behavior; accelerated linear height and bone age have not been documented (Gearhart and Jeffs, 1987; Davits et al, 1993; Chalapathi et al, 2003), but few patients have had bone age assessed after stimulation.

The author prefers two to three intramuscular injections of testosterone enanthate 2 mg/kg over a 6- to 12-week period. Hormonal stimulation has been used in less than 1% of distal repairs versus 25% of proximal to perineal cases and is recommended when the glans appears small, recognizing there are no published criteria to define normal or adequate glans diameter (Snodgrass and Yucel, 2007).

General Aspects of Surgical Repair

Suture Materials

No randomized controlled trials (RCTs) compare suture materials while controlling other factors that may influence outcomes, including severity of hypospadias, type of repair, and suturing technique. Recommendations therefore reflect the surgeon’s preference. Available needles for various sutures may also influence choice and outcomes but are rarely reported in hypospadias literature. Sutures and needles preferred by the author are listed in Table 130–1.

Table 130–1 Sutures and Needles for Hypospadias Repair

| SUTURE SIZE AND MATERIAL | NEEDLE |

|---|---|

| 7-0 polyglactin | TG 140-8 |

| 6-0 polyglactin | S 29 |

| 4-0, 5-0 polyglactin | RB |

| 6-0 polypropylene | BV 1 |

| 6-0, 7-0 polydioxanone | BV 1 |

| 4-0, 5-0 polydioxanone | RB |

Perioperative Antibiotics

No RCTs have been performed to determine if hypospadias surgical outcomes are influenced by preoperative intravenous antibiotics. One RCT comprising 101 patients compared intraoperative intravenous cefonicid plus postoperative oral cephalexin to intravenous cefonicid alone. There were no differences in the two groups regarding surgical complications, but both asymptomatic bacilluria (21% vs. 51%, P < .05) and febrile urinary tract infection (6% vs. 23%, P < .05) were more common without postoperative antibiotics (Meir and Livne, 2004). Postoperative antibiotics are commonly used during urinary diversion; the author prefers trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole.

Postoperative Urinary Diversion

One RCT randomized 64 toilet-trained boys (median age 6 years, range 2 to 17) undergoing tubularized incised plate (TIP) repair by a single surgeon to postoperative bladder catheterization or not, decided at the conclusion of the procedure. There were no differences in urethroplasty complications; however, dysuria (14% vs. 45%, P < .01), urinary retention (0% vs. 24%, P < .05), and urinary extravasation (0% vs. 17%, P < .05) occurred significantly more often in the unstented group (El-Sherbiny, 2003).

A prospective observational study by the same surgeon involved 32 consecutive non–toilet-trained boys (mean age 18 ± 6 months) undergoing TIP repair with no urinary diversion. Urinary extravasation developed in one patient the second postoperative day resulting in catheter placement. There were no urethroplasty complications with mean follow-up of 9 months (Almodhen et al, 2008).

Another prospective study compared 36 patients undergoing Mathieu repair with catheter (n = 17, mean age 4.1 years) versus without diversion (n = 19, mean age 4.6 years) and no difference was reported in urethroplasty complications at 6 months or longer follow-up (McCormack et al, 1993).

The author prefers urinary diversion to avoid the occasional need for early postoperative catheterization due to retention or extravasation. However, should the catheter inadvertently be dislodged prematurely it is not replaced unless urinary retention or extravasation occurs. A 6-Fr bladder stent is used for all repairs in prepubertal boys regardless of age, or a 12- to 14-Fr catheter is used in patients after puberty.

Dressings

Two RCTs, one having 100 patients operated on by one surgeon (Van Savage et al, 2000) and the other comprising 120 patients and four surgeons (McLorie et al, 2001), were done to evaluate the role of postoperative bandages. In the first study patients had an adhesive film versus no dressing, whereas the second compared postoperative topical antibiotic ointment alone to an adhesive film or compressive wrap followed by topical antibiotic ointment applied after dressing removal. In both, 2% of patients were excluded from randomization owing to bleeding at the conclusion of the procedure resulting in a bandage. Parents in both studies were instructed to remove the bandage by postoperative day 2 (Van Savage et al, 2000) or when it appeared loose (McLorie et al, 2001). Neither study reported the appearance of the penis on catheter removal (e.g., extent of edema or hematoma formation). Urethroplasty outcomes were not impacted by dressings versus no dressings. Both studies noted greater numbers of telephone calls from parents of boys with bandages, although one did not state if these calls specifically related to the dressing.

Both these studies concluded that bandages are not needed after hypospadias repair, and when they are used they increase parental anxiety. However, in both, parental concern also might relate to instructions to remove the dressings. McLorie and colleagues (2005) specifically noted that half the parents did not remove the bandage as instructed and that 38% of boys with adhesive films and 82% with compressive wraps experienced pain with dressing removal.

The lack of benefit to compressive wrap dressings and the greater likelihood of discomfort for the child with their removal argues against their use. Otherwise, in both studies a major argument against dressings is the bother for parents in removing them. Because adhesive films nearly always fall off spontaneously, surgeons who prefer bandages might consider their use—combined with assurances that the parents need not be concerned with dressings.

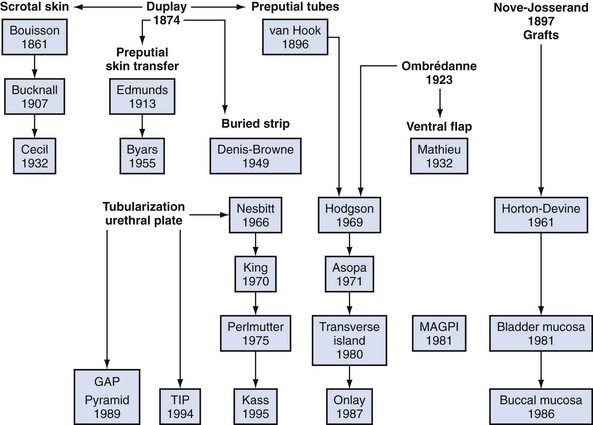

Historic Background

Although it is commonly written that more than 200 repairs have been described, hypospadias urethroplasty can be summarized into three basic categories: tubularization of the urethral plate, supplementation or substitution of the urethral plate with skin flaps, or urethral plate substitution with grafts (Fig. 130–3). Of these, today the most common primary surgery is urethral plate tubularization. This is also the most recently introduced concept, given that the urethral plate—tissues extending distally from the hypospadias meatus that normally form the urethra—was only recognized as a distinct structure in the late 1980s.

Figure 130–3 Genealogy of hypospadias urethroplasty. Duplay is considered the father of tubularized skin flaps, Ombredanne inspired ventral flaps, and Nove-Josserand pioneered grafts. The urethral plate was not recognized as a distinct structure until the late 1980s, and so procedures utilizing the plate are the most recently described. GAP, glans approximation procedure; MAGPI, meatoplasty and glansplasty; TIP, tubularized incised plate.

Hypospadias surgery that began in the early 1800s originally focused on repair for proximal defects. VC often found in these cases was ascribed to fibrous bands, and by the 1940s the belief that these fibrous tissues represented dysplastic corpus spongiosum extending fanlike from the meatus became firmly entrenched. This “chordee tissue,” now recognized as the urethral plate, was resected for straightening. Consequently, substitution urethroplasty was necessary, most often accomplished using preputial flaps. Variations of these flaps account for most of the different repairs described.

Modern hypospadias surgery dates to 1980. Duckett (1980) mobilized inner preputial flaps on a vascular pedicle away from dorsal shaft skin, providing greater flexibility to transpose them ventrally. The following year he described the meatoplasty and glanuloplasty (MAGPI) technique for glanular defects (Duckett, 1981), opening the door for routine distal repair that today comprises most hypospadias surgery. It was also Duckett who defined the urethral plate and then modified his tubularized preputial flap (“transverse island”) to the onlay version supplementing, rather than substituting, the plate after realizing routine “chordee” excision was not necessary (Baskin et al, 1994). By the end of the decade nearly all primary hypospadias could be repaired using MAGPI, onlay, or tubularized preputial flaps.

Although tubularization of the broad or deeply grooved urethral plate had been reported sporadically, in 1994 the midline incision was described to tubularize the narrow or flat plate without the need for supplemental skin flaps (Snodgrass, 1994). The TIP repair subsequently gained widespread use for its perceived simplicity and improved cosmetic outcomes versus flap repairs. Its application to proximal hypospadias followed increased realization that the urethral plate is not fibrous scar but well-vascularized tissues that potentially can be preserved for urethroplasty, even in some cases with VC.

Hypospadias Surgery

Ventral Curvature

Etiology

The penis exhibits VC during normal development (Kaplan and Lamm, 1975), which implies that persistent bending in hypospadias reflects arrested development. Consequently, ventral tissues—including shaft skin, dartos, corpus spongiosum, urethral plate, and overlying tunics of the corpora cavernosa—may be shortened relative to the dorsal surface. Previous concepts that dysplastic dartos and corpus spongiosum coalesce into fibrous “chordee” tissues that require resection have been disproved by histologic studies in both embryos and surgical specimens referenced earlier (Baskin et al, 1998; Snodgrass et al, 2000).

Extent of Curvature

Prevalence and severity of VC after release of shaft skin varies by extent of hypospadias. From the author’s experience since 2000, VC occurred in 50 (11%) of 440 primary distal cases undergoing artificial erection (Snodgrass et al, 2010), 12 of 40 (30%) midshaft repairs (Snodgrass and Yucel, 2007), and 57 of 70 (81%) proximal repairs (Snodgrass and Prieto, 2009). VC in all patients with distal and midshaft repairs was less than 30 degrees.

VC in consecutive proximal shaft to perineal hypospadias was less than 30 degrees in 22 patients (31%) and more than 30 degrees in 35 patients (50%). Half of these patients with proximal hypospadias either had no VC after the penis was degloved or had minor bending readily correctable with a single dorsal plication.

It is also important to consider what extent of VC impairs sexual activity. Reports concerning adult men seeking medical attention suggest bending 30 degrees or more is present before sexual dysfunction occurs (Bracka, 1989; Thiounn et al, 1998; Van Der Horst et al, 2004; Greenfield et al, 2006).

Preoperative and Intraoperative Assessment

Preoperative assessment cannot accurately predict either the extent of curvature or the means required for straightening. Apparent bending may improve or resolve as the skin is degloved, so the common maneuver of compressing penopubic and penoscrotal tissues at the base of the penis to better visualize the penile shaft may falsely suggest or exaggerate VC by traction on deficient ventral skin. The finding that skin adjacent to the meatus may retract as far as the penoscrotal junction during degloving provides additional proof that relatively short ventral skin contributes to curvature.

Cephalad traction on the glans stay suture causes the bent (>30 degrees) penis to pivot from side to side. Such observations formed the basis for determining VC and its correction until saline corporeal injection was described by Gittes and McLaughlin in 1974. Artificial erection induced by saline injection remains the most commonly used means to assess presence and severity of VC, as well as to document successful correction. Criticisms of the technique include the potential for supraphysiologic or subphysiologic intracorporeal pressure during injection to distort findings. After ventral dissection of tissues from the tunica albuginea and/or ventral lengthening procedures for the corpora cavernosa (see later discussion), repeat erection may be difficult, owing to corporeal leakage.

Vasoactive drugs have also been injected to induce erection during hypospadias repair (Perovic et al, 1997; Kogan, 2000), with the proposed advantage being more physiologic assessment in contrast to saline injection. However, dose regimens are empirical in children, erection lasts longer than with saline irrigation unless a reversal agent is injected, and there may be increased bleeding from the prolonged erection.

It should also be noted that reported degrees of curvature, including those by this author, most likely were subjectively determined by visual estimate without direct measurement with a protractor.

Straightening Maneuvers

Curvature up to 30 degrees can be corrected by midline dorsal plication into the tunica albuginea of the corpora cavernosa directly opposite the area of greatest bending (Fig. 130–4). Baskin and colleagues (1998) reported lack of sensory nerves in this location, and straightening without corporotomy can be achieved.

Figure 130–4 Midline dorsal plication. The surface of the corpora cavernosa is exposed in the midline opposite the region of curvature, avoiding the dorsal veins; and then polypropylene suture is placed, burying the knot.

There are few reports concerning sutures used, efficacy, or durability of plication, and assessment is complicated by lack of objective determination of intraoperative and postoperative extent of curvature. The only outcomes data for midline plication to date are found in a retrospective review of 43 prepubertal boys, 53% with VC greater than 30 degrees, whose curvature was straightened using one or two polypropylene 4-0 or 5-0 sutures. At median 16 months’ follow-up, 93% of patients were thought to maintain a straight penis (Bar Yosef et al, 2004). In contrast, the author uses only a single 6-0 polypropylene suture for midline plication of bending less than 30 degrees, preferring alternative methods to multiple plications when curvature is greater.

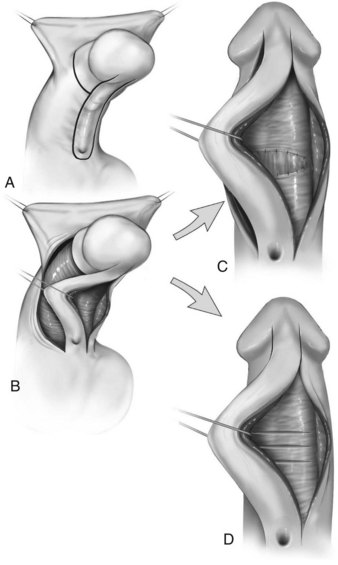

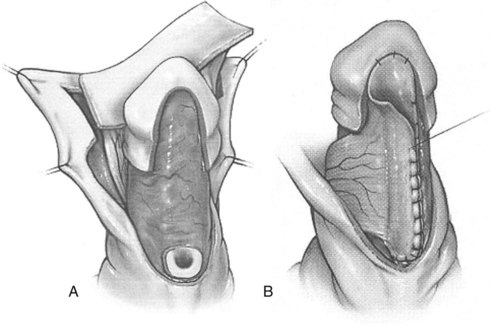

Similarly, optimal management of VC greater than 30 degrees remains uncertain. Multiple plications using 5-0 to 4-0 polypropylene are described, although concerns for both recurrent curvature and loss of penile length increase when more than one plication is performed (Braga et al, 2008). This extent of bending after skin degloving and ventral dartos dissection is considered disproportion between the ventral and dorsal aspects of the corpora cavernosa (Baskin et al, 1994). Ventral lengthening traditionally involves transection of the urethral plate followed by transverse incision from the 3- to 9-o’clock position into the tunica albuginea to expose erectile tissues of the corpora in the region of greatest curvature. The resultant defect has been closed using dermal grafts, small intestine submucosa, or tunica vaginalis flaps or grafts (Fig. 130–5). No evidence indicates the outcome is significantly influenced by choice of materials for corporotomy repair. Most proponents of the use of small intestine submucosa have used single-layer material; use of four-layer small intestine submucosa was reported in two small series and was associated with recurrent curvature in one (2 of 12 cases) (Soergel et al, 2003) but not in another (0 of 21 cases) (Elmore et al, 2007).

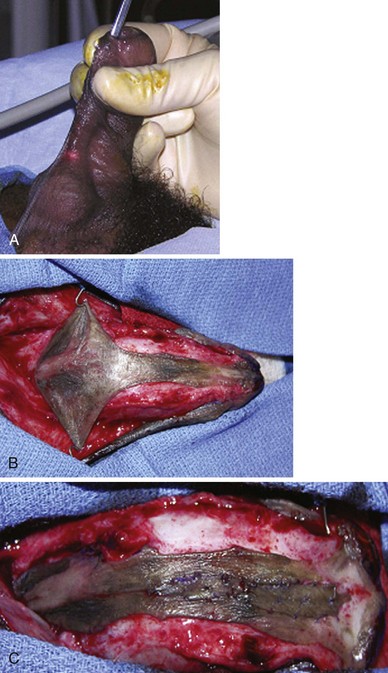

Figure 130–5 Ventral corporeal lengthening to correct ventral curvature. A, Ventral penile curvature showing skin incisions preserving the urethral plate. B, Urethral plate dissected from the corpora cavernosa. C, Ventral corporotomy with grafting. D, Multiple corporotomies without grafting.

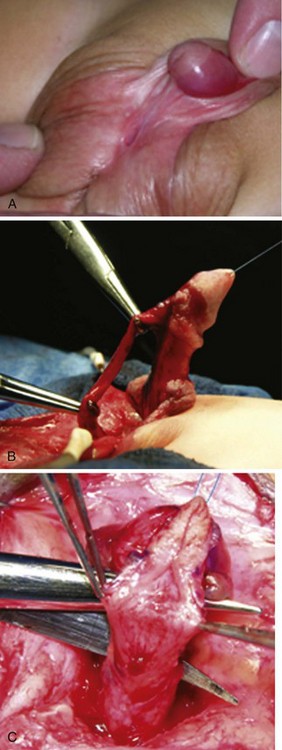

Urethral plate transection to facilitate corporeal grafting requires substitution urethroplasty using preputial flaps or grafts in either one or two stages. Alternatively, the urethral plate and adjacent corpus spongiosum can be preserved and dissected from the underlying surface of the corpora cavernosa. Elevation of the plate alone has been reported to correct curvature (Mollard and Castagnola, 1994), or it can be combined with corporotomy and grafting (Kajbafzadeh et al, 2007). Dissection under the urethral plate can also be continued proximally to near the membranous junction, elevating the normal urethra from the corpora (Fig. 130–6). This maneuver was adapted from urethral stricture repair in which mobilization of the urethra combined with its inherent elasticity allows gaps to 5 cm in adults to be bridged (Warwick et al, 1997). After dissection of the urethral plate and urethra, residual VC can be corrected by dorsal plication or ventral corporotomy (Riccabona et al, 2003; Bhat, 2007; Snodgrass and Prieto, 2009). Rather than a single corporotomy with grafting, two to three transverse incisions can be made into the tunica albuginea without exposing erectile spongy tissue or need for grafting (see Fig. 130–5) (Devine, 1983; Snodgrass and Prieto, 2009). The preserved urethral plate can then be incorporated into TIP repair or onlay urethroplasty.

Figure 130–6 Mobilization of urethral plate and proximal urethra. A, Scrotal hypospadias with ventral curvature. B, Penis straightening included dissection of the urethral plate and proximal urethra off the corpora cavernosa. The picture shows there is no tension on the urethra after mobilization. Ventral corporeal lengthening and/or dorsal plication can also be used with this maneuver as needed to correct ventral curvature. C, Despite elevation of the urethral plate from the corpora, a dorsal midline incision for TIP urethroplasty can still be performed without creating separate strips.

(Reprinted from Snodgrass W, Prieto J. Straightening ventral curvature while preserving the urethral plate in proximal hypospadias repair. J Urol 2009;182[Suppl. 4]:1720–5.)

VC that persists despite mobilization of the urethral plate and urethra requires urethral plate transection for straightening. In the author’s experience 15 patients with penoscrotal to perineal hypospadias have undergone urethral plate elevation alone (3 patients) or combined with urethral mobilization (12 patients), of which 3 patients had persistent bending despite dissection to the membranous region, visibly due to tethering by a short urethral plate (Snodgrass and Prieto, 2009).

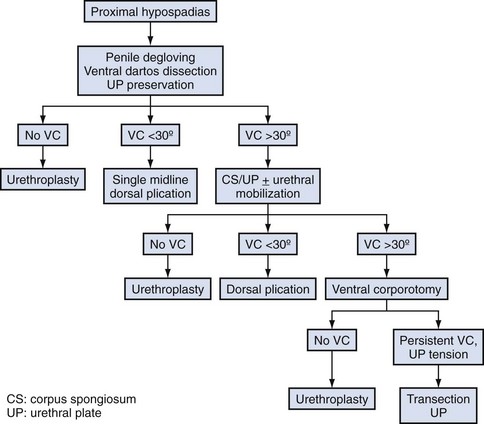

A proposed algorithm for correcting penile curvature is outlined in Figure 130–7.

Congenital Penile Curvature

Description of patients diagnosed with “chordee without hypospadias” is complicated by varying inclusion or exclusion of patients with divergent corpus spongiosum and a hypoplastic urethra. In series excluding such cases, VC is attributed most often to deficient ventral shaft skin and dartos, followed by corpora cavernosa disproportion, with a shortened urethra the least common finding (Donnohoo et al, 1998; Tang et al, 2007).

Outcomes of Straightening after Puberty

No report describes effects of pubertal growth on straightening achieved by dorsal plication. A single series comprising 16 patients, 14 with proximal hypospadias and 2 with congenital penile curvature without hypospadias, provides information after corporotomy and dermal grafting (Badawy and Morsi, 2008). Although all patients were postpubertal at final review, only 3 were sexually active. Fifteen reported firm erection, but 1 patient undergoing repair after puberty subsequently noted impaired erection despite sildenafil, requiring intracorporeal injection for sufficient firmness. The authors reported weakness and bulging at the site of his graft.

Key Points: Ventral Curvature

Urethroplasty

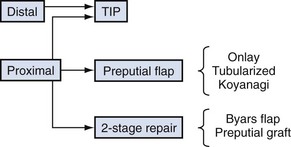

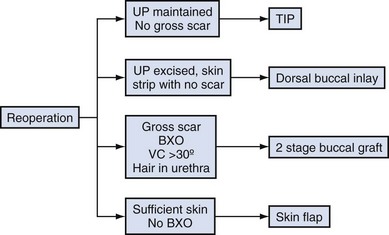

The most commonly used options for primary hypospadias urethroplasty are summarized in Figure 130–8. It is traditional to describe repairs in separate categories for distal, midshaft, and proximal defects based on meatal position after skin degloving and correction of VC, although an alternative classification would be to consider primary repairs accomplished by tubularizing the urethral plate versus options when the plate is not maintained for urethroplasty (Sozubir and Snodgrass, 2003), most notably when VC greater than 30 degrees results in plate transection.

Distal Hypospadias

The most commonly performed operation to repair distal hypospadias is the TIP repair. Although other procedures such as MAGPI, Mathieu flip-flap, and urethral advancement remain in use, a survey of current practices indicates these together account for less than 10% of distal procedures (Cook et al, 2005). Technical aspects of these operations are little changed from prior descriptions in this textbook, with the exception of V incision into the ventral lip of flip-flaps, which attempts to create a vertical meatus (Boddy and Samuel, 2000). However, a study correlating preoperative configuration of the urethral plate (deep vs. moderate or shallow groove) to cosmetic results after V incision into onlay preputial flaps questions the reliability of this maneuver to achieve a vertical neomeatus unless the plate already is deeply grooved (Hayashi et al, 2007).

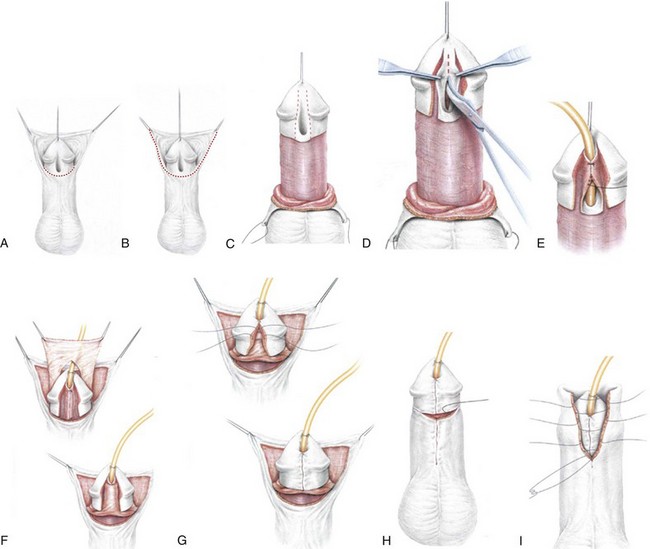

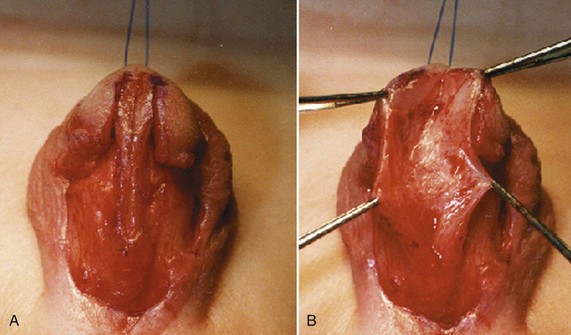

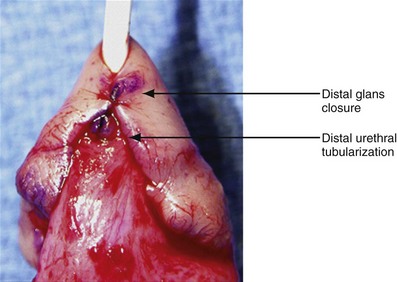

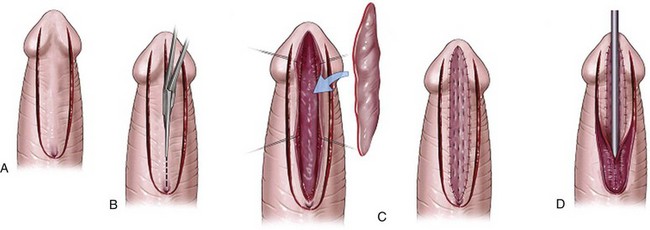

Figure 130–9 depicts TIP repair. The key step is midline incision of the urethral plate, which widens a narrow plate and converts a flat into a deep plate groove (Fig. 130–10), ensuring a vertical, slit neomeatus and a normal-caliber neourethra. Tubularization should not continue beyond approximately the midpoint of the dissected glans wings, corresponding to a point some 3 mm proximal to the distal extent of the plate, to avoid iatrogenic meatal stenosis. Glansplasty approximates the glans halves distally to create a normal-appearing meatus independent of plate tubularization (Fig. 130–11), because the opening of the urethral plate is not sutured to the glans as is commonly done with flaps.

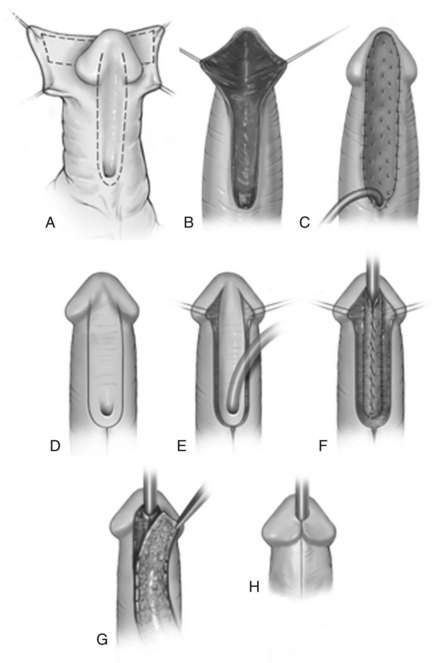

Figure 130–9 Distal tubularized incised plate repair. A, Circumscribing incision is made approximately 2 mm below meatus when circumcision is desired. B, Ventral V incision when foreskin reconstruction is planned. C, Penis degloved (or only ventral surface exposed during foreskin preservation). Visible junction of glans wings to urethral plate is marked and then infiltrated with 1 : 100,000 epinephrine. D, Midline incision of the urethral plate extends from within the meatus to the end of the plate, without entering the distal glans. Incision continues to near the corpora cavernosa. E, Urethral plate tubularization begins distally approximately 3 mm from the end of the plate, ensuring an oval, not rounded, meatus. Subepithelial running 7-0 polyglactin sutures proceed proximally. A knot is tied, and then suturing returns distally to complete a two-layer closure. F, Dartos flap is dissected from the dorsal prepuce and shaft skin, buttonholed, and transposed ventrally to cover the neourethra. A flap can usually be developed from the ventrolateral dartos in patients undergoing foreskin reconstruction G, Glansplasty begins distally, and a 7-0 polyglactin suture is used to create the meatus at the desired location, independent of the underlying urethral plate tubularization. A second 7-0 polyglactin suture under the first reinforces this distal approximation. Then a single layer of 6-0 polyglactin interrupted subepithelial sutures completes the glans wings closure to the corona. H, Shaft skin closure for circumcision after excising excess prepuce and approximating the inner preputial collar ventrally. Interrupted subepithelial 7-0 polyglactin is used. I, Foreskin reconstruction performed in three layers using 7-0 polyglactin sutures: inner prepuce, dartos, and outer shaft skin are separately approximated using subepithelial 7-0 polyglactin.

(Reprinted from Snodgrass WT. Snodgrass technique for hypospadias repair. BJU Int 2005;95[4]:683–93.)

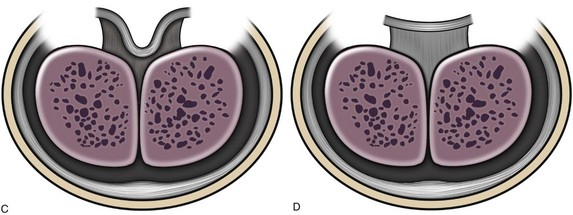

Figure 130–10 Urethral plate incision. A, Urethral plate before dorsal incision. B, Dorsal incision widens and deepens the plate. Incision depth varies according to urethral plate configuration. A deep plate (C) that already extends near the corpora may not need incision, whereas the flat plate (D) requires deep incision.

(A and B, Reprinted from Snodgrass W, Koyle M, Manzoni G, et al. Tubularized incised plate hypospadias repair: results of a multicenter experience. J Urol 1996;156[2 Pt. 2]:839–41; C and D reprinted from Snodgrass WT. Tubularized incised plate hypospadias repair: indications, technique, and complications. Urology 1999;54[1]:6–11.)

Figure 130–11 Tubularized incised plate (TIP) glansplasty. The most distal stitch approximating glans wings, creating the neomeatus, usually is beyond the most distal stitch of the tubularized urethral plate. It is not necessary to suture the glans wings to the urethral plate in TIP repair.

Contraindications

Whether urethral plate characteristics (flat vs. deeply grooved, narrow vs. wide) determine the appropriate use of TIP repair has been debated. Some consider a flat and/or narrow urethral plate a contraindication to TIP repair (Holland and Smith, 2000), whereas others report TIP repair reliably corrects distal hypospadias regardless of urethral plate configuration (Nguyen and Snodgrass, 2004). The author has not found an alternative procedure necessary for distal hypospadias repair in over 500 consecutive cases (Snodgrass et al, 2010).

Outcomes

Table 130–2 summarizes published short-term results for TIP distal urethroplasty. The longest reported mean follow-up is 2 years, and to date no series describes outcomes after puberty in patients operated on when children.

One purported advantage to the TIP repair over alternative procedures for distal hypospadias is improved appearance of the meatus, creating a vertical slit neomeatus in contrast to the sometimes rounded configuration after Mathieu or other flap repairs. In addition to meatal shape, however, normal cosmesis requires sufficient glans approximation below the meatus to the corona so that the neomeatus appears correctly positioned. Two to three sutures closing the glans wings between the meatus and corona are needed and are readily placed in the TIP repair because glans closure is independent of urethral plate tubularization. In contrast, it may be difficult to mature the neomeatus created with flaps to glans wings and maintain sufficient glans to allow these additional two to three stitches proximally to the corona.

Two studies objectively assess cosmesis. One used postoperative photographs blindly scored by a panel of medical professionals that ranked TIP repair results superior to those from Mathieu and onlay flaps (Ververidis et al, 2005). A second administered Likert scale questionnaires to parents and the operating surgeon after TIP repair or circumcision. No significant differences occurred between surgeon and parents in either group or in satisfaction after TIP repair for hypospadias versus elective circumcision in boys with a normal penis (Snodgrass et al, 2008).

Midshaft Hypospadias

In a consecutive series of boys with midshaft hypospadias none had VC greater than 30 degrees, indicating the urethral plate can be maintained for urethroplasty in most cases (Snodgrass and Yucel, 2007). Accordingly, options for repair include TIP repair or onlay preputial flap. Technical aspects of TIP repair are unchanged from distal operations described earlier, with the addition that divergent corpus spongiosum can be dissected from the underlying corpus cavernosa and released from glans wings to approximate over the shaft portion of the neourethra to near the corona (Yerkes et al, 2000).

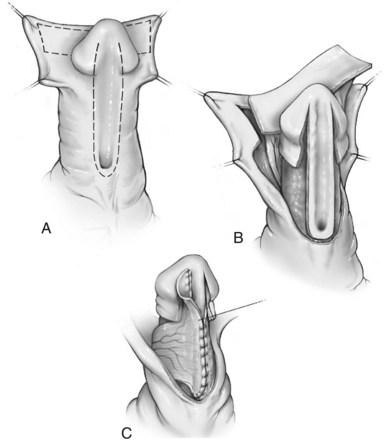

An onlay preputial flap is depicted in Figure 130–12. Thin skin proximal to the urethral meatus is incised to the midline convergence of corpus spongiosum wings. Then inner prepuce is harvested on its vascular pedicle from either the dorsal hood or from one side of Byars flaps after the dorsal hood is incised (Sedberry-Ross et al, 2007). The flap should be gently stretched to fit the urethral plate without redundancy. Distally, flaps are secured to the glans wings to create the neomeatus. The vascular pedicle or a separate dartos flap can be used to cover the exposed suture line.

Figure 130–12 Onlay preputial flap. A, Lines of incision to create the preputial flap and preserve the urethral plate. B, Preputial flap mobilized on its vascular pedicle. C, Flap sewn to the urethral plate.

Outcomes

Reports concerning midshaft TIP repair most often combine outcomes with patients having either more distal or proximal defects. The two largest series with results specifically for midshaft hypospadias found urethroplasty complications in 13% and 16% (Snodgrass and Yucel, 2007; Al-Ghorairy et al, 2009).

Similarly, onlay preputial flap results specifically for midshaft repair are not readily obtainable. The procedure originally was described for distal to midshaft cases not amenable to MAGPI, and to enable use for distal hypospadias the meatus was incised proximally to create a defect of sufficient length to accommodate the flap. The most recent publication providing outcomes for midshaft hypospadias reported 29% urethroplasty complications in 51 patients (Sedberry-Ross et al, 2007).

Proximal Hypospadias

The greatest controversy in primary hypospadias surgery concerns decision making for proximal cases. Options depend on whether the urethral plate is available for urethroplasty after associated VC is straightened. If so, then either TIP repair or an onlay preputial flap can be used. When the urethral plate is transected a one-stage urethroplasty can be accomplished by tubularized preputial flaps or the Koyanagi flap or a two-stage repair done with Byars flaps or preputial grafts.

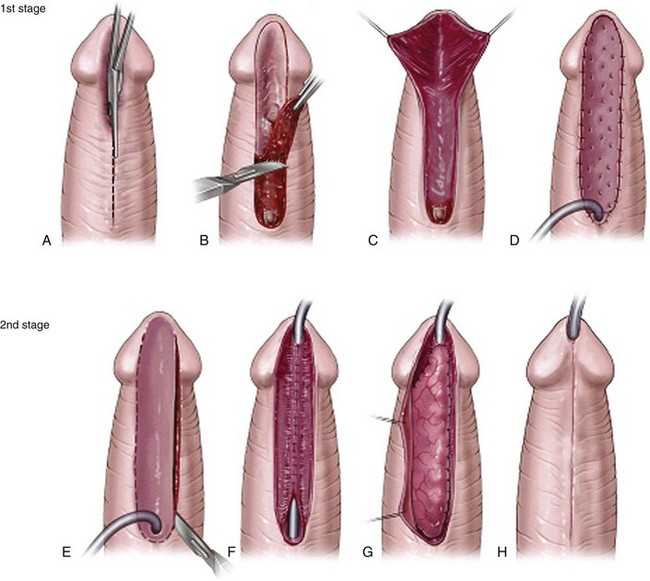

Tubularized Incised Plate Repair

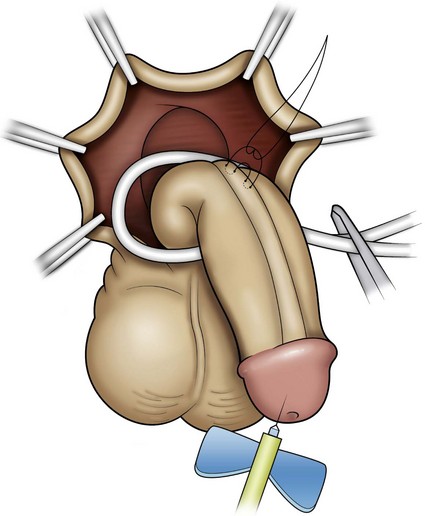

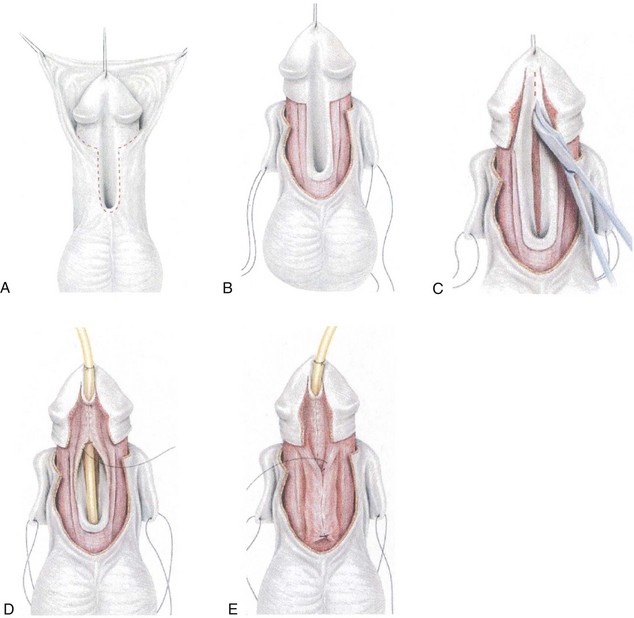

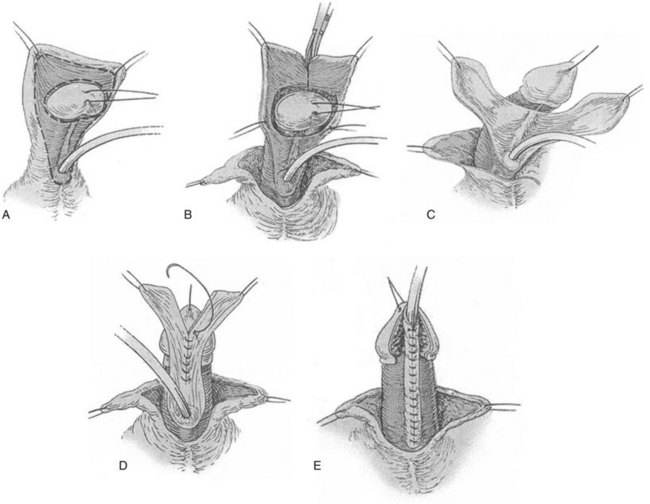

Steps for a proximal TIP repair are illustrated in Figure 130–13. There are several important distinctions between distal and proximal TIP repairs. First, correction of VC may lead to dissection of the urethral plate, and proximal urethra, from the corpora cavernosa. Midline incision can still be performed without creating separate strips (see Fig. 130–6C). The neourethra is tubularized with interrupted subepithelial sutures reinforced by a second running layer. Divergent corpus spongiosum is next sewn over the neourethra, followed by a tunica vaginalis flap (Fig. 130–14). To reduce chances for secondary partial concealment of the penis, shaft skin at the penoscrotal junction is secured to the corpora cavernosa with subepithelial 5-0 polydioxanone to either side of the ventral midline before skin closure.

Figure 130–13 Proximal tubularized incised plate repair. A, Circumscribing incision preserves urethral plate in patient desiring circumcision. B, After degloving, glans wings are separated from the urethral plate. Corpus spongiosum is dissected from the cavernosal bodies and released distally from the glans wings for later spongioplasty. At this point artificial erection is performed and ventral curvature straightened as discussed in the text. C, Midline urethral plate incision. D, Two-layer urethral plate tubularization using interrupted subepithelial 7-0 polyglactin followed by running 7-0 polydioxanone. E, Spongioplasty approximates divergent corpus spongiosum over the neourethra, before a tunica vaginalis barrier flap is added.

(Reprinted from Snodgrass WT. Snodgrass technique for hypospadias repair. BJU Int 2005;95[4]:683–93.)

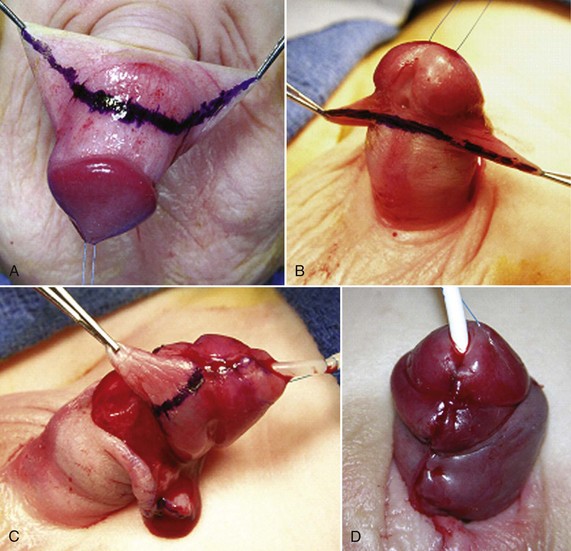

Figure 130–14 Tunica vaginalis barrier flap. A, The testis is delivered and the tunica vaginalis opened transversely. B, The tunica vaginalis flap is dissected to near the external ring to avoid tension on either the testis or the penis. C, Flap covers the entire neourethra. The testis is pexed into its scrotal compartment, which is then sutured closed.

Outcomes

In a cohort of 56 boys with proximal shaft to perineal hypospadias, the author corrected 36 (64%) using the TIP procedure while the other 20 (36%) underwent staged repairs after urethral plate transection during straightening (Snodgrass and Yucel, 2007). After that report, urethral plate/proximal urethral dissection with superficial transverse corporotomies were incorporated into the algorithm for straightening, resulting in more frequent preservation of the plate. In 22 consecutive proximal shaft to perineal repairs, 19 (86%) had TIP repair versus only 3 (14%) undergoing a two-stage repair (Snodgrass and Prieto, 2009).

Urethroplasty complications occurred in 8 (53%) of the original 15 patients undergoing proximal TIP repair by the author, which were mostly fistulas in 5 (33%) despite a dartos flap over the neourethra in every case. After technical modifications described earlier (two-layer subepithelial tubularization and spongioplasty) the complication rate in the next 20 cases decreased to five complications (25%), including two (10%) fistulas. After substituting tunica vaginalis rather than dartos for the barrier layer, in the most recent 22 cases there were no fistulas, the single complication (4.5%) being glans dehiscence.

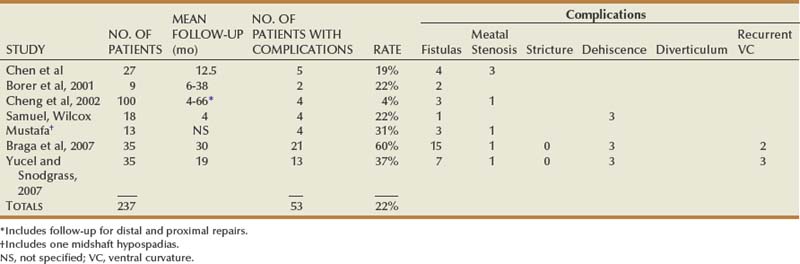

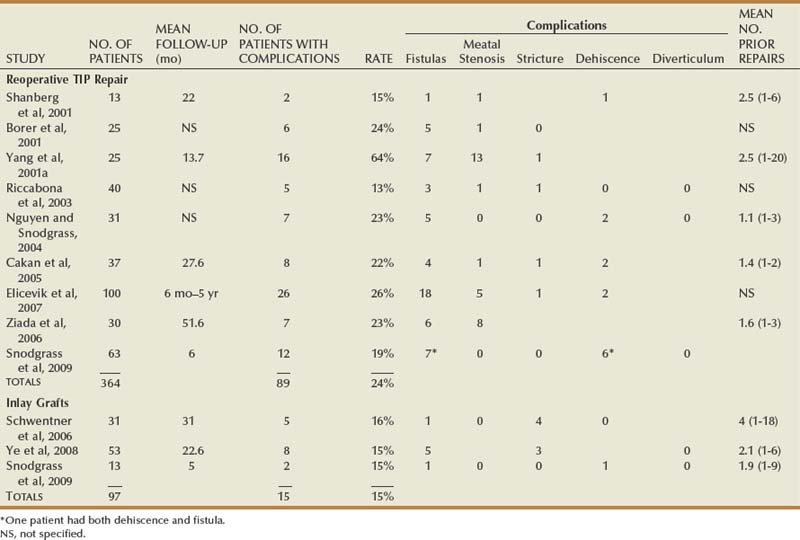

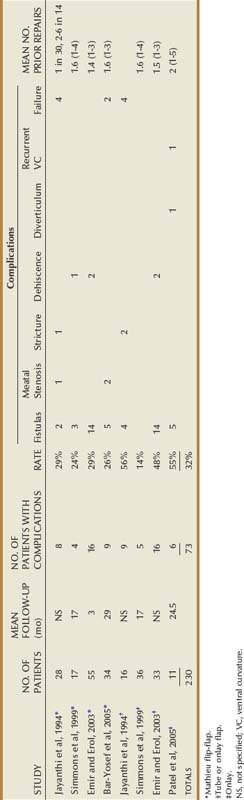

Table 130–3 shows other published results for proximal TIP repair, excluding those in which proximal outcomes cannot be distinguished from more distal cases. Selection bias must be considered in these reports, because none except the study of Yucel and Snodgrass states the total number of proximal cases operated during the study period to determine the relative use of TIP repair versus other techniques.

Onlay Preputial Flap

Need for a longer flap usually requires the inner prepuce to be dissected from an intact dorsal hood and then rotated ventrally on its pedicle. Otherwise, steps in the procedure are as already shown in Figure 130–12.

Outcomes

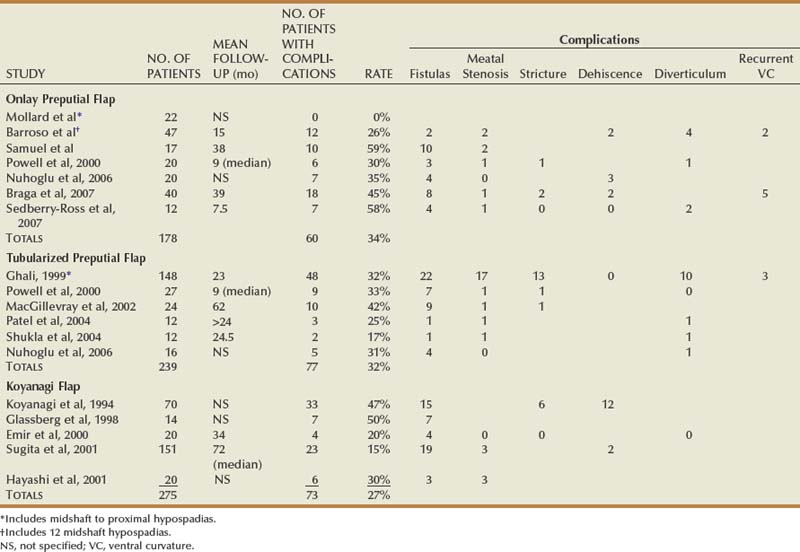

Reports specifically concerning outcomes of onlay preputial flaps for proximal hypospadias are summarized in Table 130–4.

Tubularized Preputial Flap

This procedure is illustrated in Figure 130–15. After excision of the urethral plate and required straightening maneuvers, the required length of inner prepuce is harvested, tubularized, and transferred ventrally. The native urethra is secured to the corpora cavernosa and then spatulated before anastomosis to the flap to reduce incidence of stricture, and then the tube is gently stretched distally, with its suture line facing dorsally, and anchored to the corpora cavernosa with interrupted stitches. Glans wings are sewn to the flap to create the neomeatus.

Figure 130–15 Tubularized preputial flap. A, After degloving and release of ventral dartos, persisting ventral curvature greater than 30 degrees led to excision of the urethral plate (see text for additional straightening maneuvers to attempt preservation of urethral plate). Inner preputial flap approximately 10 mm wide is dissected on its dartos vascular pedicle and transposed ventrally. This flap can be tubularized, with the proximal end anastomosed to the spatulated native urethra and distal end to the glans wings. B, Alternatively, one edge of the flap can be fixed with interrupted sutures to the corpora cavernosa from the proximal meatus distally into the glans and then the flap is trimmed and the opposite edge sutured along the first to create a tube with uniform caliber. Glansplasty and skin closure is similar to that described for onlay preputial flaps.

Alternatively, the open flap is brought ventrally and then one side is secured to the corpora cavernosa just lateral to the midline with interrupted subepithelial sutures. The flap is gently stretched, excess tissues are excised, and then the other side is similarly anchored to the corpora to complete tubularization. This tube is tailored proximally to approximately the caliber of the native urethra before the anastomosis is made (Canning, 2007).

Outcomes

Tubularized preputial flaps (also referred to as “transverse island preputial flaps”) were originally used when MAGPI was not possible before development of the onlay preputial flap. Consequently, much of the outcomes data mixes large numbers of patients with distal hypospadias without separately reporting results in proximal cases that today comprise the only use of this procedure. Table 130–4 summarizes outcomes specifically after proximal hypospadias repairs.

Koyanagi Flap

Use of the Koyanagi repair is determined from the outset of the operation based on the surgeon’s impression that VC will lead to urethral plate excision, and so decision making for this procedure differs from all others described in this section.

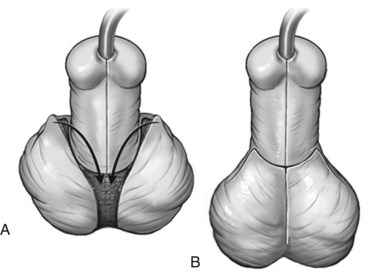

The Koyanagi repair updates the Russell operation (Russell, 1900), primarily by maintaining blood supply to the flaps as illustrated in Figure 130–16. These flaps are brought together ventrally, sewn into a single strip, and then tubularized proximally to distally.

Figure 130–16 Koyanagi flap. A, Proposed lines of incisions to create flap. B, The flap can be divided into two wings as shown or maintained in one piece with a central buttonhole to transpose it ventrally. C, The urethral plate in the center of the flap is dissected from the corpora to near the meatus, and the glanular portion of the plate is excised as glans wings are made. D, Inner flap margins are reapproximated, and excess flap skin is excised. E, The outer margins are closed to complete tubularization using 7-0 polyglactin or polydioxanone subepithelial interrupted or running sutures. Glansplasty and skin closure are as described for other preputial flaps.

Outcomes

Proponents offer varied opinions for managing the dartos vascular pedicle to the lateral skin flaps. Koyanagi and colleagues (1994) split the contiguous flap into a Y at the 12-o’clock position. Others attribute complications to devascularization of the distal region and instead maintain the loop, passing the glans dorsally through a 12-o’clock buttonhole in the dartos pedicle (Hayashi et al, 2001b). Alternatively, in the largest reported series the pedicle was removed from the distal 2 cm of the flap, which was treated as a tubularized graft (Sugita et al, 2001). Results are shown in Table 130–4.

Byars Flaps

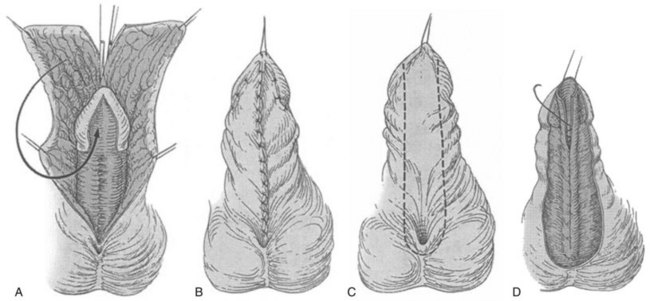

A two-stage flap repair (Fig. 130–17) divides the dorsal preputial hood, transposes the resultant flaps ventrally, and reapproximates them in the midline from the native urethral meatus to the glans tip. Glans wings should be widely separated to allow sufficient skin to be placed for later tubularization. The author previously maintained the urethral plate within the glans to combine distal TIP repair with a proximal Byars flap urethroplasty (Snodgrass et al, 1998) but discontinued that approach due to complications (see later). After a period of approximately 6 months, second-stage tubularization of the skin flaps is accomplished.

Figure 130–17 Byars flap. A, After degloving and release of ventral dartos, persisting ventral curvature greater than 30 degrees led to excision of the urethral plate (see text for additional straightening maneuvers to attempt preservation of urethral plate). The dorsal preputial hood is incised in the midline and the two flaps transposed ventrally on either side of the penis. The prepuce is advanced into the glans; alternatively, the urethral plate can be maintained within the glans. B, Flap edges are approximated in the midline. C, Six months later a U-shaped incision is made approximately 10 mm wide. D, The resultant strip is tubularized in two layers.

Outcomes

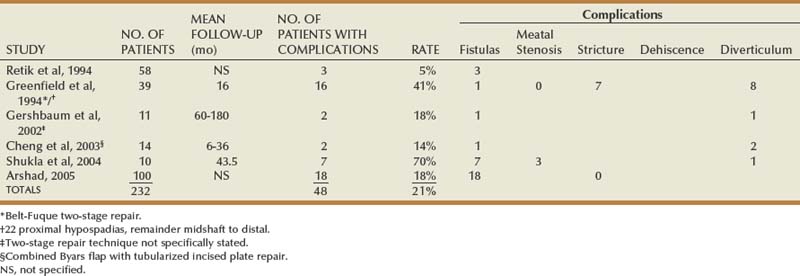

Table 130–5 shows outcomes data for staged skin flap repairs. The largest series did not state the number of patients with follow-up or duration of follow-up. Nearly half the patients operated on by Greenfield and coworkers (1994) had midshaft or more distal hypospadias, all of which corrected by the Belt-Fuque technique, but outcomes were included because this is a two-stage preputial flap procedure.

Cheng and colleagues (2003) transected the urethral plate proximally, preserving the distal portion, and used Byars flaps to bridge the gap to the native urethra. Diverticula formed in 2 of 14 patients from the interposed skin flaps without distal obstruction. The authors preserved the glanular urethral plate in eight of nine Byars flap repairs. The complication rate was 100%, including five diverticula and two strictures at the flap/urethral plate junction. Of the diverticula, four had no distal obstruction except for the presumed increased resistance to flow created by the glans. Considering diverticulum formation without obstruction evidence of preputial skin distensibility, another 4 patients had buccal grafts—thought less elastic—interposed between the distally preserved urethral plate and proximal native urethra, but a diverticulum still developed in one, leading the author to abandon these techniques.

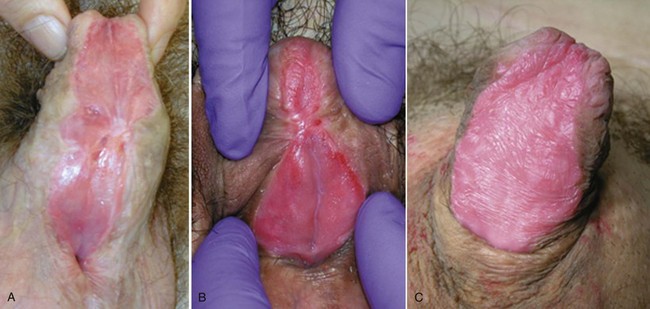

Preputial Grafts

Inner prepuce can be harvested as a graft to bridge the defect from native urethra to glans tip when the urethral plate is excised. This approach has not been commonly used in the United States because curvature leading to urethral plate transection most often has been corrected by corporeal incision and grafting, meaning subsequent addition of a urethral graft would place one graft onto another. Preputial grafts are an option when remaining VC after urethral plate excision is less than 30 degrees or if multiple superficial transverse corporotomies are used for correcting VC without corporeal grafting.

The procedure is shown in Figure 130–18. After excision of the plate the ventral native urethra is sewn to surrounding skin edges to establish a proximal meatus, and the glans wings are widely opened. Inner prepuce is harvested, and the dartos is excised from its undersurface. Then it is secured to the dorsal lip of the native urethra and gently stretched distally. Sutures anchor it to adjacent shaft skin and glans wings, with subepithelial stitches used along the glans tip to avoid tracks at the neomeatus during the second stage. Additional rows of stitches “quilt” the graft to the corpora cavernosa to facilitate neovascularization by limiting fluid collection under the graft. A tie-over dressing further immobilizes the graft during the first week of healing. Six months later this neourethral plate is tubularized and covered with tunica vaginalis.

Figure 130–18 Two-stage preputial graft. A, Ventral curvature leads to urethral plate excision. B, Wide dissection of glans wings. Graft is outlined on inner prepuce. C, Graft is harvested from the inner prepuce and secured to the meatus proximally, along shaft skin, and into the glans using interrupted 7-0 polyglactin. Subepithelial glans sutures minimize suture marks. Additional 6-0 polyglactin quilting stitches are placed down the midline and to either side at 0.5-cm intervals to minimize space where a seroma or hematoma could collect under the graft. An RB needle facilitates anchoring the graft to the underlying corporeal surface. D, U-shaped incision at least 6 months after first-stage surgery. E, Glans wings developed. F, Tubularization of the neourethral plate. G, Tunica vaginalis flap covers the neourethra. H, Skin closure using subepithelial sutures.

Outcomes

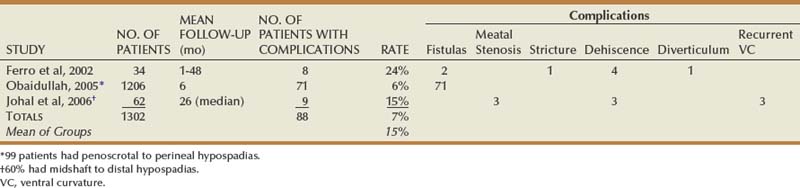

Cloutier described two-stage grafting in 1962, but Bracka is credited with stimulating modern interest in this approach. His report (Bracka, 1995) mixes primary cases of all extents with reoperations, and so data specifically for primary proximal hypospadias are not available. Of the three publications summarized in Table 130–6, two similarly combine data mostly from midshaft to distal repair with results from a smaller number of proximal hypospadias. Only the report by Ferro and colleagues (2002) focused on proximal repairs using Bracka’s technique. In all these, complications from grafting occurred in less than 5%, consisting of partial graft loss that did not require an additional procedure for correction before second-stage tubularization.

Skin Closures

Inner Preputial Collar

The ventral preputial deficiency found in most hypospadias patients includes its inner “mucosal” surface, which normally provides coverage between the corona and shaft skin. Instead, shaft skin occupies the space from the margins of the open glans wings to the urethral plate and meatus. To create the appearance of a normal circumcised penis, this shaft skin must be removed and ventral midline closure done using inner prepuce transposed from the dorsal hood. Firlit (1987) described a chevron incision dorsally to create bilateral “darts” for ventral midline approximation (Fig. 130–19).

Figure 130–19 Inner preputial collar. Line for dorsal (A) and ventral (B) skin incision. C, Excision of perimeatal shaft skin after urethroplasty and glansplasty. D, Completed inner preputial collar. Interrupted subepithelial 7-0 polyglactin approximates the sides proximally, and 9-0 polyglactin is used through the epithelium at the corona, because it is unlikely to produce visible suture tracks.

Although it has been suggested that divergence between the darts may preclude midline approximation, necessitating rotational flaps (Redman, 2006), the author has not encountered this situation. The proximal corners of the darts are first approximated using a 7-0 polyglactin subepithelial suture, which then provides ventral traction. Midline closure proceeds distally with interrupted subepithelial stitches. The space immediately below the glans is repaired using 9-0 polyglactin stitches placed through the epithelium. The postoperative appearance with the mucosal collar is contrasted to examples in which the collar was not formed, illustrating the importance of this step for optimal cosmetic outcomes (Fig. 130–20).

Circumcision versus Foreskin Reconstruction

The abnormal prepuce can be removed for circumcision or reconstructed ventrally if a natural, nonoperated appearance is preferred. For circumcision, a circumferential skin incision is made initially, creating lateral darts to approximate the mucosal collar ventrally, as described in the preceding section. When foreskin reconstruction is desired, the initial skin incision extends in a V from the corners of the dorsal prepuce ventrally to below the meatus, without a circumferential incision.

In patients to be circumcised, after completion of urethroplasty, glansplasty, and ventral mucosal collar the dorsal prepuce is incised in the midline proximally to the level of the mucosal collar and then stitched to it with a subepithelial 7-0 polyglactin suture. Next, the ventral median raphe is approximated from proximally to near the mucosal collar using interrupted subepithelial sutures. Excess lateral skin is excised and remaining skin edges are closed with subepithelial sutures to minimize the likelihood of suture tracks (Snodgrass, 1999a).

Foreskin repair begins with subepithelial closure of the inner surface with the dorsal foreskin retracted proximally. Then the prepuce is extended distally and the dartos approximated to reinforce closure of the inner layer. Finally, the outer skin margins are sutured together with subepithelial stitches, avoiding iatrogenic distal phimosis. The family is instructed not to retract the foreskin until the surgeon determines postoperatively that edema and tissue reaction have subsided, usually after 6 weeks.

Outcomes

Preputioplasty is an option in nearly all distal hypospadias surgeries, although occasionally the prepuce is too narrow to close ventrally. Foreskin reconstruction also can be considered for midshaft to proximal repairs, unless flap urethroplasty leaves insufficient skin. Although typically done without a circumscribing incision, when VC suggests need for dorsal plication the penis can be degloved with subsequent preputioplasty (Snodgrass et al, 2006).

Klijn and coworkers (2001) reported increased urethroplasty and skin complications with foreskin reconstruction versus circumcision during distal hypospadias repair, but these may have resulted from their reliance on skin flap (Mathieu) urethroplasty and their instructions to parents to begin foreskin retraction only 2 weeks postoperatively. In a comparison of matched cohorts undergoing distal TIP repair with foreskin reconstruction versus circumcision, Suoub and associates (2008) found no differences in urethroplasty or skin complications, which is also the experience of the author (unpublished data).

Minor and Major Scrotoplasty

Scrotal encroachment onto the ventral penile shaft can occur associated with any extent of hypospadias. This sometimes creates a false impression that the meatus is penoscrotal when it is actually found located on the distal shaft after penile degloving moves the scrotum proximally. Midline scrotal cleft and varying degrees of superolateral extension of scrotum alongside the penis most often are encountered in proximal hypospadias, in some cases combined with a rugated, feminized appearance at the dorsal penopubic junction. Collectively these findings are commonly referred to as penoscrotal transposition, although this term also describes the rare condition in which the penis is actually located completely below the scrotum.

Encroachment onto the penile shaft is corrected by release of the scrotum as the penis is degloved, with subsequent suture fixation to the correct penoscrotal location more proximally. Scrotal clefts are excised and resultant edges sutured to create a median raphe. Minor superolateral encroachment with a rugated penopubic junction is corrected by incising the ventral junction of scrotum and penile shaft skin to approximately the 4- and 8- or 3- and 9-o’clock positions and then affixing the shaft skin to the desired penoscrotal junction (Fig. 130–21). Pronounced extensions of scrotum superolaterally to the penis are moved ventrally as rotation flaps and secured to the penoscrotal junction (Fig. 130–22).

Figure 130–21 Minor scrotoplasty. A, Minor scrotal encroachment on the penopubic junction. B, Ventral incisions at the penoscrotal junction allow ventral rotation of shaft skin and scrotum. Incision continues to approximately the 3- to 4- and 8- to 9-o’clock positions, with subsequent ventral approximation of the shaft skin. C, Smooth penopubic junction with normal-appearing scrotum.

Figure 130–22 Major scrotoplasty. A, After completion of urethroplasty, skin incisions are made along the abnormal extensions of scrotum to either side of the penis. These flaps are rotated down and to the midline. B, Skin closure using subepithelial sutures.

An alternative method for correction involves completely removing shaft skin from the penis, maintaining its vascular pedicle, and then subsequently moving both above the scrotum through a “buttonhole” (Kolligian et al, 2000).

Attention to vascular pedicles allows simultaneous correction of scrotal encroachment with urethroplasty, because penile and scrotal tissues derive from distinct embryologic anlage.

Outcomes

There are few reports specifically concerning scrotoplasty outcomes. In one retrospective series, 5 of 37 patients with scrotal flap rotation developed penile tethering or secondary cryptorchidism (Pinke et al, 2001). Simultaneous Koyanagi repair with rotational scrotal flaps has been reported without apparent increased scrotoplasty or urethroplasty complications (Glassberg et al, 1998; Nonomura et al, 1988).

Assessing Surgical Outcomes

The goal of hypospadias repair is to improve function and appearance as near to normal as possible. Therefore, success requires more than straightening curvature and extending the urethra to the glans. Reports from teens and adults operated on when children emphasize that cosmetic results are as important as functional outcomes (Bracka, 1989; Mureau et al, 1995; Aho et al, 2000b). Furthermore, a glanular meatus without obstruction or fistula does not ensure the patient can void with a straight and compact stream.

Initial Postoperative Follow-up

Ideal frequency and duration of follow-up after surgery are ill defined. The author prefers postoperative examinations after distal to midshaft hypospadias repair at 6 weeks and 6 months, whereas those undergoing proximal surgery are recommended to have additional annual follow-up until toilet training.

Although it is often stated that periodic assessment should continue to puberty, it is unlikely many patients operated on while infants will have adult follow-up. Accordingly, there are few data regarding outcomes in adults operated on while children. Furthermore, long-term results that are reported often concern operations no longer in common usage due to ongoing evolution in surgical techniques.

Means to assess results and detect complications beyond simple visual inspection of the penis also are not standardized. Furthermore, the time at which various complications usually appear are poorly reported, which makes minimum duration of follow-up to detect the majority of problems unclear.

Neourethral Calibration

Passage of a sound or bougie can be done to determine if a small-appearing neomeatus is stenotic and to exclude neourethral stricture, especially in pre–toilet-trained boys in whom uroflowmetry is not practical. The author performs a single calibration in pre–toilet-trained patients 6 months postoperatively; but given the low rates of meatal stenosis and neourethral stricture, instrumentation could be reserved for those with suspected obstructive voiding symptoms. The normal caliber of the meatus varies with age; the minimum is variously reported from less than or equal to 8 French (Litvak et al, 1976) to greater than or equal to 10 French (Yang et al, 2001b).

Uroflowmetry

Uroflowmetry is advocated as a noninvasive means to assess neourethral function. Parameters considered include both maximum flow rate and appearance of the curve, defined as bell versus plateau shaped. Obstruction is suspected in plateau curves with maximum flow rates more than 2 standard deviations below the mean of age-matched controls (Garibay et al, 1995).