Introduction

The vitreous is a transparent extracellular gel, with a complicated structural framework consisting of collagen, soluble proteins, hyaluronic acid and a water content of 99%. Its total volume is approximately 4.0 mL. The few cells normally present in the gel are located predominantly in the cortex and consist of hyalocytes, astrocytes and glial cells. The vitreous provides structural support to the globe while providing a clear path for light to reach the retina. It also hinders the forward diffusion of oxygen from the retinal blood supply to the anterior segment. Once liquefied or surgically removed it does not reform. Vitreous opacities may be caused by developmental abnormalities, trauma or disease. Most have already been described in other chapters (e.g. snowballs, malignant cells, parasitic cysts and hereditary vitreoretinopathies) and will not be mentioned here.

Vitreous haemorrhage

Vitreous haemorrhage is a relatively common condition that has many diverse causes (Table 17.1), most of which have been described elsewhere in the book.

1

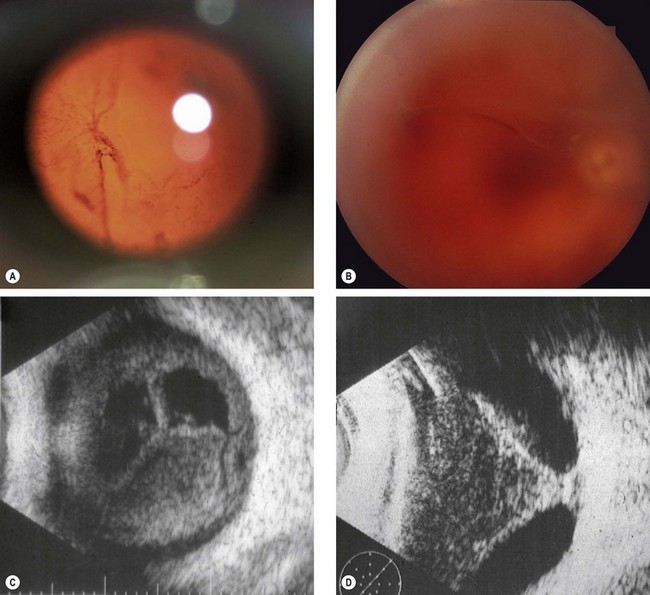

The symptoms vary according to the severity of the bleed. Mild haemorrhage (

Fig. 17.1A) causes sudden diffuse blurring of vision and floaters, but may not affect visual acuity, whilst a dense bleed may result in very severe visual loss.

2

B-scan ultrasonography in unclotted vitreous haemorrhage generally shows a uniform medium grey appearance (

Fig. 17.1C). Once cellular aggregates develop, small particulate echoes become visible. Echography is very helpful in evaluating eyes with dense vitreous haemorrhage in order to exclude the possibility of underlying retinal detachment (

Fig. 17.1D) or retinal tear.

3

Treatment varies according to the severity and underlying cause.

Table 17.1 Causes of vitreous haemorrhage

1 Acute posterior vitreous detachment associated either with a retinal tear or avulsion of a peripheral vessel 2 Proliferative retinopathies

• Following retinal vein occlusion 3 Miscellaneous retinal disorders

|

Asteroid hyalosis (Benson disease)

1

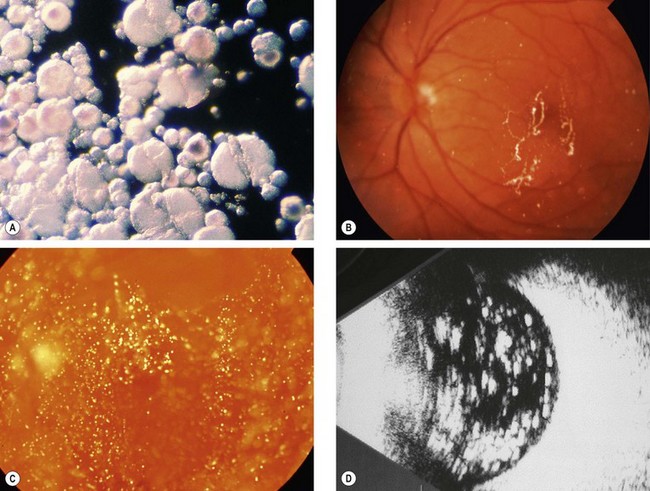

Pathogenesis. Asteroid hyalosis is a common degenerative process in which tiny calcium-pyrophosphate globules collect within the vitreous gel (

Fig. 17.2A). One eye is affected in 75% of patients; the condition rarely causes visual problems and in the majority of cases it is asymptomatic. An association with diabetes has been suggested but is unproven. The prevalence of asteroid hyalosis increases with age and affects 2.9% of those aged 75–86 years. It is more common in men than in women.

2

Signs. Numerous tiny round yellow-white particles that vary in size and density (

Fig. 17.2B and C). They move with the vitreous during eye movements but do not sediment inferiorly when the eye is immobile.

3

US shows very high amplitude echoes (

Fig. 17.2D).

Synchisis scintillans (cholesterolosis bulbi)

1

Pathogenesis. Synchisis scintillans occurs as a consequence of chronic vitreous haemorrhage, often in a blind eye. The condition is usually discovered when frank haemorrhage is no longer present. The crystals are composed of cholesterol and are derived from plasma cells or degraded products of erythrocytes, and lie either freely or engulfed within foreign body giant cells.

2

Signs. Numerous flat golden-brown refractile particles that tend to sediment inferiorly when the eye is immobile. Occasionally the anterior chamber may also be involved (

Fig. 17.3).

Amyloidosis

1

Amyloidosis is a localized or systemic condition in which there is extracellular deposition of a fibrillary protein. Vitreous opacification typically occurs in the familial amyloidosis that is also characterized by polyneuropathy, prominent corneal nerves and light-near dissociation of pupillary reactions.

2

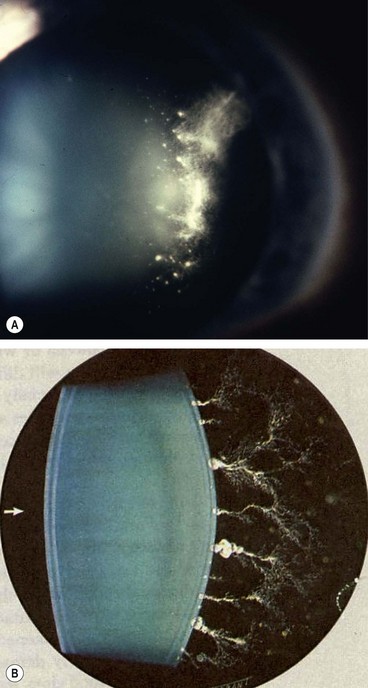

Signs. The vitreous opacities may be unilateral or bilateral and are initially perivascular. Later they involve the anterior vitreous and take on a

characteristic sheet-like (‘glass wool’) appearance (

Fig. 17.4A). The opacities may become attached to the posterior lens by thick footplates (

Fig. 17.4B). Dense opacification resulting in significant visual impairment may require vitrectomy.

Vitreous cyst

Vitreous cysts (Fig. 17.5) are rare congenital remnants of the primary hyaloidal system or ciliary body pigment epithelium. Treatment is seldom required, although laser photocystotomy or vitrectomy have been suggested in patients with annoying symptoms.