CHAPTER 12 Desquamative Gingivitis

Chronic Desquamative Gingivitis

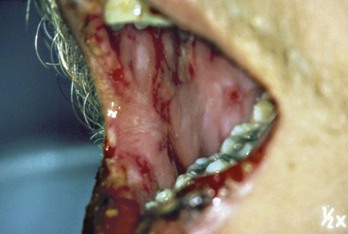

Although first recognized and reported in 1894,156 the term chronic desquamative gingivitis was coined in 1932 by Prinz122 to describe a peculiar condition characterized by intense erythema, desquamation, and ulceration of the free and attached gingiva50,100 (Figure 12-1). Patients may be asymptomatic; when symptomatic, however, their complaints range from a mild burning sensation to an intense pain. Approximately 50% of desquamative gingivitis cases are localized to the gingiva, although patients can have involvement of the gingiva plus other intraoral and even extraoral sites.56,112 Initially, the cause of this condition was unclear, with a variety of possibilities suggested. Because most cases were diagnosed in women in the fourth to fifth decades of life (although desquamative gingivitis may occur as early as puberty or as late as the seventh or eighth decade), a hormonal derangement was suspected. In 1960, however, McCarthy et al94 suggested that desquamative gingivitis was not a specific disease entity, but a gingival response associated with a variety of conditions. This concept has been further supported by numerous immunopathologic studies.77,114,130,151

Figure 12-1 Chronic desquamative gingivitis. Irregular, conspicuous erythema involves the free and attached gingival tissues.

Use of clinical and laboratory parameters have revealed that approximately 75% of desquamative gingivitis cases have a dermatologic genesis. Cicatricial pemphigoid and lichen planus account for more than 95% of the dermatologic cases.110 However, many other mucocutaneous autoimmune conditions, such as bullous pemphigoid, pemphigus vulgaris, linear immunoglobulin A (IgA) disease, dermatitis herpetiformis, lupus erythematosus, and chronic ulcerative stomatitis, can clinically manifest as desquamative gingivitis.138

Other conditions that must be considered in the differential diagnosis of desquamative gingivitis include chronic bacterial, fungal, and viral infections, as well as reactions to medications, mouthwashes, and chewing gum. Although less common, Crohn’s disease, sarcoidosis, some leukemias, and even factitious lesions have also been reported to present clinically as desquamative gingivitis.138,160

Therefore it is of paramount importance to ascertain the identity of the disease responsible for desquamative gingivitis to establish the appropriate therapeutic approach and management. To achieve this goal, the clinical examination must be coupled with a thorough history and routine histologic and immunofluorescence studies.160 Despite this diagnostic approach, however, the cause of desquamative gingivitis cannot be elucidated in up to one-third of the cases.125

Diagnosis of Desquamative Gingivitis: A Systematic Approach

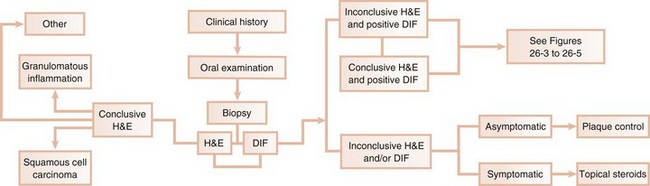

Desquamative gingivitis is only a clinical term, not a diagnosis per se. Once it is rendered, a series of laboratory procedures should be used to arrive at a final diagnosis. Thus the success of any given therapeutic approach depends on the establishment of an accurate final diagnosis. The following discussion represents a systematic approach to elucidate the disease triggering desquamative gingivitis (Figure 12-2).

Figure 12-2 Diagnostic approach for desquamative gingivitis. H&E, Hematoxylin and eosin; DIF, direct immunofluorescence.

Clinical History

A thorough clinical history is mandatory to begin the assessment of desquamative gingivitis.113 Data regarding the symptomatology associated with this condition, as well as its historical aspects (i.e., when did the lesion start, has it worsened, or is there a habit that exacerbates the condition), provide the foundation for a thorough examination. Information regarding previous therapy to alleviate the condition should also be documented.

Clinical Examination

Recognition of the pattern of distribution of the lesions (i.e., focal or multifocal, with or without confinement to the gingival tissues) provides leading information to begin the formulation of a differential diagnosis. In addition, a simple clinical maneuver. such as Nikolsky’s sign, offers insight into the plausibility of the presence of a vesiculobullous disorder.97

Biopsy

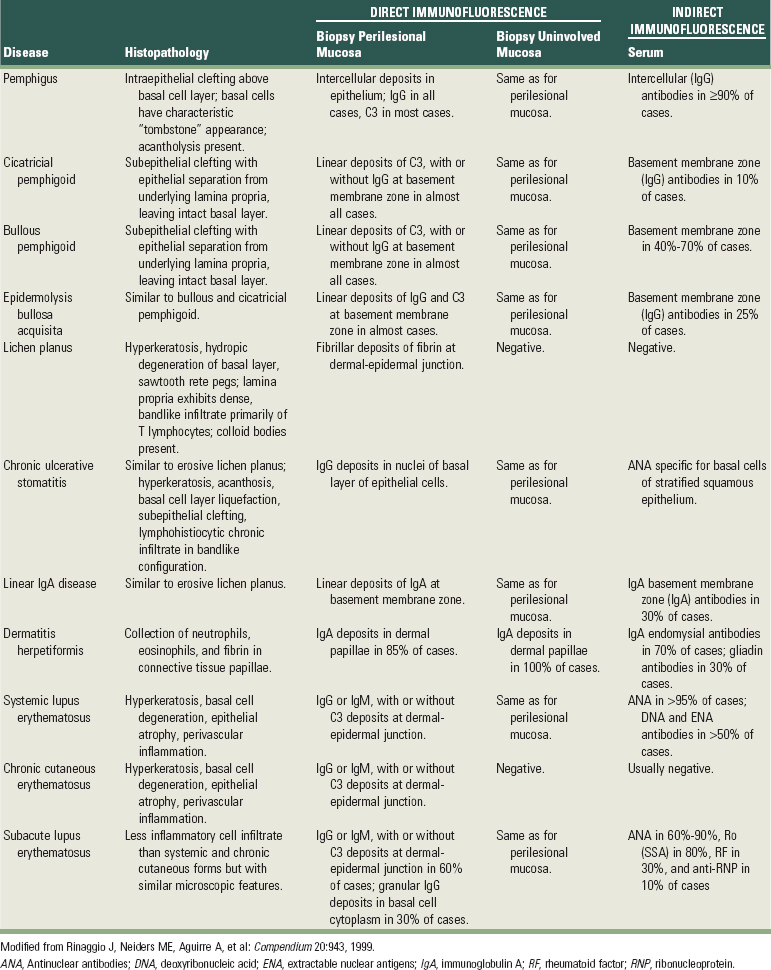

Given the extent and number of lesions that may be present in an individual, an incisional biopsy is the best alternative to begin the microscopic and immunologic evaluation. An important consideration is selection of the biopsy site. A perilesional incisional biopsy should avoid areas of ulceration because necrosis and epithelial denudation severely hamper the diagnostic process. Once the tissue is excised from the oral cavity, the specimen can be bisected and then submitted for microscopic examination. Buffered formalin (10%) should be used to fix the tissue for conventional hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) evaluation. Michell’s buffer (ammonium sulfate buffer, pH 7.0) is used as transport solution for immunofluorescence assessment. In general, an incisional biopsy of uninvolved (normal) mucosa will show the same immunofluorescent findings as the biopsy of the perilesional tissue. However, there are notable exceptions, such as lichen planus and chronic cutaneous lupus erythematosus, in which only the lesional tissue will exhibit the corresponding immunologic markers (Table 12-1).

TABLE 12-1 Histopathologic, Direct, and Indirect Immunofluorescence Findings in Select Conditions that may Present Clinically as Desquamative Gingivitis

![]() Science Transfer

Science Transfer

In many instances, the initial diagnosis of desquamative lesions of the gingiva is the responsibility of the dental clinician. Biopsy of lesions accompanied by appropriate histologic and immunofluorescence tests are needed to confirm the clinical diagnosis. In cases with dermatologic or systemic components, patients should be managed in conjunction with appropriate physician referral. Many of the disease entities are made worse by normal mechanical oral hygiene techniques and so chlorhexidine rinses are generally used for plaque control to reduce any secondary gingival inflammation caused by the biofilms and to reduce patient discomfort.

Allergic manifestations can themselves result in gingival desquamation and also may exacerbate the destruction from other causes. Patients need to be informed to stop exposure to the most common allergens found in the diet, such as cinnamon used as a flavoring agent and pyrophosphates found in tartar control toothpaste.

Clinicians should be aware that in some cases, squamous cell carcinomas can initially present as “desquamative gingivitis,” which is yet another reason for the use of biopsy on all desquamative lesions.

Microscopic Examination

Sections of approximately 5 µm of formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded tissue stained with conventional H&E are obtained for light microscopy examination.

Immunofluorescence

For direct immunofluorescence, unfixed frozen sections are incubated with a variety of fluorescein-labeled, antihuman serum (anti-IgG, anti-IgA, anti-IgM, antifibrin, and anti-C3). With indirect immunofluorescence, unfixed frozen sections of oral or esophageal mucosa from an animal such as a monkey are first incubated with the patient’s serum to allow attachment of any serum antibodies to the mucosal tissue. The tissue is then incubated with fluorescein-labeled antihuman serum. Immunofluorescence tests are positive if a fluorescent signal is observed in the epithelium, its associated basement membrane, or the underlying connective tissue (see Table 12-1).

Management

Once the diagnosis is established, the dentist must choose the optimum management for the patient. This is accomplished according to three factors: (1) practitioner’s experience, (2) systemic impact of the disease, and (3) systemic complications of the medications. A detailed consideration of these three factors dictates three different scenarios.

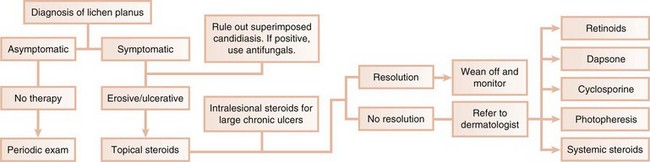

In the first scenario, the dental practitioner takes direct and exclusive responsibility for the treatment of the patient, as with erosive lichen planus that is responsive to topical steroids (Figure 12-3).

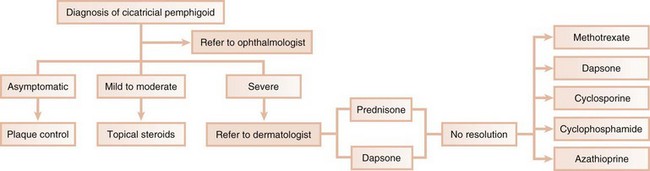

In the second scenario, the dentist collaborates with another health care provider to evaluate and/or treat a patient concurrently. The classic example is seen with cicatricial pemphigoid, in which dentists and ophthalmologists work together (Figure 12-4). Although the dentist addresses the oral lesions, the ophthalmologist monitors the integrity of the ocular conjunctiva.

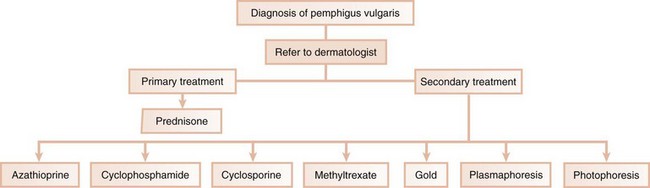

In the third scenario, the patient is immediately referred to a dermatologist for further evaluation and treatment. This occurs with conditions in which the systemic impact of the disease transcends the boundaries of the oral cavity and results in significant morbidity and even mortality. Pemphigus vulgaris is a clear example of a condition that, once diagnosed by the dentist, requires immediate referral to a dermatologist (Figure 12-5). In addition, the complications of chronically administered systemic medications that are indicated for the management of diseases, such as pemphigus vulgaris or nonresponsive mucous membrane pemphigoid (e.g., diabetes mellitus, osteoporosis, or methemoglobinemia), warrant the referral to a dermatologist or a specialist in internal medicine.

When oral treatment is provided, periodic evaluation is needed to monitor the response of the patient to the selected therapy. Initially, the patient should be evaluated at 2 to 4 weeks after beginning treatment to ensure that the condition is under control. This observation should continue until the patient is free of discomfort. Appointments every 3 to 6 months would then be appropriate. Doses of medication(s) are usually adjusted during this interval.

Table 12-2 summarizes suggested contemporary therapeutic approaches used to treat select conditions that clinically present as desquamative gingivitis. Dentists clearly play an important role in the diagnosis and management of desquamative gingivitis. The importance of being able to recognize and properly diagnose this condition is accentuated by the fact that a serious and life-threatening disease, such as squamous cell carcinoma, may mimic desquamative gingivitis.127

TABLE 12-2 Accepted Contemporary Therapeutic Approaches Used To Treat Select Conditions That Clinically Present As Desquamative Gingivitis

| Disease | Therapy |

|---|---|

| Erosive lichen planus | |

| Cicatricial pemphigoid | |

| Pemphigus | Refer to dermatologist for management with prednisone (20-30 mg/day); concomitant use of azathioprine may be needed. |

| Chronic ulcerative stomatitis |

g, Grams; pc, after meals; hs, at bedtime; IU, international units; bid, twice daily; qid, four times daily.

Diseases Clinically Presenting as Desquamative Gingivitis

Lichen Planus

Lichen planus is an inflammatory mucocutaneous disorder that may involve mucosal surfaces (e.g., oral cavity, genital tract, and other mucosae) and the skin (including the scalp and the nails).131 The current evidence suggests that lichen planus is an immunologically-mediated mucocutaneous disorder in which host T lymphocytes play a central role.11,64,92 Although the oral cavity may present lichen planus lesions with a distinct clinical configuration and distribution, the clinical presentation sometimes may simulate other mucocutaneous disorders. Therefore a clinical diagnosis of oral lichen planus should be accompanied by a broad differential diagnosis. Numerous epidemiologic studies have shown that oral lichen planus presents in 0.1% to 4% of the population.139,142 The majority of patients with oral lichen planus are middle-aged and older females, with a 2 : 1 ratio of females to males. Children are rarely affected. In a dental setting, cutaneous lichen planus is observed in about one-third of the patients diagnosed with oral lichen planus.88 In contrast, two-thirds of patients seen in dermatologic clinics exhibit oral lichen planus.136

Oral Lesions

Although there are several clinical forms of oral lichen planus (reticular, patch, atrophic, erosive, and bullous), the most common are the reticular and erosive subtypes. The typical reticular lesions are asymptomatic and bilateral and consist of interlacing white lines on the posterior region of the buccal mucosa. The lateral border and dorsum of the tongue, hard palate, alveolar ridge, and gingiva may also be affected. In addition, the reticular lesions may have an erythematous background, which is a feature associated with coexisting candidiasis. Oral lichen planus lesions follow a chronic course and have alternating, unpredictable periods of quiescence and flare-ups.

The erosive subtype of lichen planus is often associated with pain and clinically manifests as atrophic, erythematous, and often ulcerated areas. Fine, white radiating striations are observed bordering the atrophic and ulcerated zones. These areas may be sensitive to heat, acid, and spicy foods (Figure 12-6).

Gingival Lesions

Seven percent to 10% of patients with oral lichen planus have lesions restricted to the gingival tissue99,136 that may occur as one or more types of four distinctive patterns, as follows:

Figure 12-7 Erosive lichen planus presenting as desquamative gingivitis. The gingival tissues are erythematous, ulcerated, and painful.

(Courtesy Dr. Luis Gaitan, Oral Pathology Laboratory, Faculty of Odontology, National Autonomous University of Mexico (UNAM), Mexico City.)

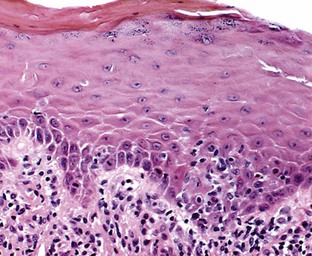

Histopathology

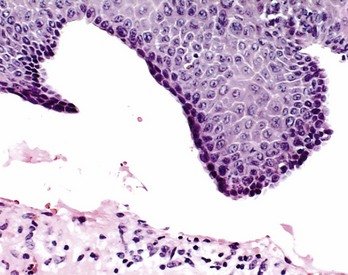

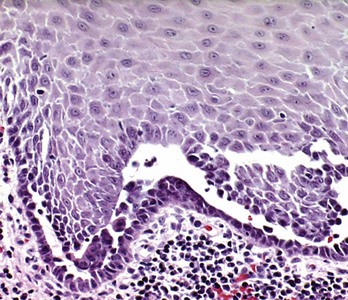

Microscopically, the three main features that characterize oral lichen planus are (1) hyperkeratosis or parakeratosis, (2) hydropic degeneration of the basal layer, and (3) a dense, bandlike infiltrate primarily of T lymphocytes in the lamina propria (Figure 12-8). Classically, the epithelial rete ridges have a “sawtooth” configuration. Hydropic degeneration of the basal layer of the epithelium may be sufficiently extensive that the epithelium becomes thin and atrophic or detaches from the underlying connective tissue and produces either a subepithelial vesicle or an ulcer. Colloid bodies (Civatte bodies) are often seen at the epithelium–connective tissue interface. A microscopic diagnosis of oral lichen planus is straightforward in the keratotic lesions, and biopsy specimens should be obtained from these areas if possible. However, these classic histologic features may be obscured in the areas of ulceration, making a conclusive diagnosis of oral lichen planus difficult based solely on conventional microscopy. Electron microscopy studies indicate that separation of the basal lamina from the basal cell layer is an early manifestation of lichen planus.61

Figure 12-8 Microscopic appearance of lichen planus. Biopsy from gingival lesion shows hyperkeratosis and mild hypergranulosis. Focal basal cell degeneration, lymphocytic exocytosis, and thickening of the basement membrane are apparent. The rete pegs exhibit a slight serrated configuration. The papillary lamina propria shows a bandlike infiltrate of lymphohistiocytic, chronic inflammatory cells. (Hematoxylin and eosin [H&E] stain; original magnification ×100.)

It is noteworthy that oral lesions of lichen planus may change in pattern, and in certain unusual cases, a second or even a third biopsy may be necessary to arrive at a definitive diagnosis. More importantly, controversy exists about the malignant potential of oral lichen planus. In recent studies, it has been estimated that oral cancer emerges in up to 2% of patients with oral lichen planus.41,55,62,63,150 In contrast, other researchers reject or question the connection between oral lichen planus and oral cancer.42,66,87,123 Despite this controversy, biopsy and close follow-up are warranted in these patients.

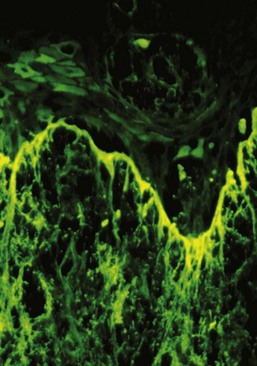

Immunopathology

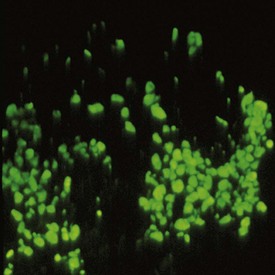

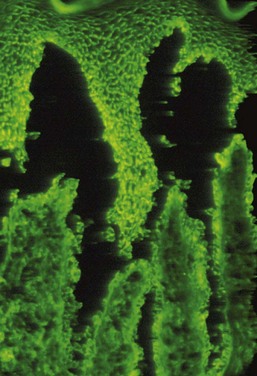

Direct immunofluorescence of both lesional and perilesional oral lichen planus biopsy specimens reveals linear fibrillar (“shaggy”) deposits of fibrin in the basement membrane zone (Figure 12-9), along with scattered, immunoglobulin-staining cytoid bodies in the upper areas of the lamina propria (Figure 12-10). Serum tests using indirect immunofluorescence are negative in lichen planus (see Table 12-1).

Differential Diagnosis

The classic clinical presentation of oral lichen planus can be simulated by other conditions, mainly by lichenoid mucositis. If oral lichen planus is confined to the gingival tissues (erosive oral lichen planus), the identification of fine, white radiating striations bordering the erosive areas support a clinical diagnosis of oral lichen planus. If the white striations are absent, the differential diagnosis should primarily include mucous membrane pemphigoid and pemphigus vulgaris. Other, less common possibilities include linear IgA disease (LAD) and chronic ulcerative stomatitis.

Treatment

The keratotic lesions of oral lichen planus are asymptomatic and do not require treatment once the microscopic diagnosis is established. However, follow-up of the patient every 6 to 12 months is warranted to monitor suspicious clinical changes and the emergence of an erosive component.

In contrast, the erosive, bullous, or ulcerative lesions of oral lichen planus are treated with high-potency topical steroids, such as 0.05% fluocinonide gel (Lidex, three times daily). Lidex can also be mixed 1:1 with carboxymethyl cellulose (Orabase) paste or other adhesive ointment. A gingival tray can also be used to deliver Lidex or 0.05% clobetasol propionate with 100,000 IU/ml of nystatin in Orabase. Three 5-minute applications of this mixture daily appear to be effective in controlling erosive lichen planus.57 Intralesional injections of triamcinolone acetonide (10 to 20 mg) or short-term regimens of 40 mg of prednisone daily for 5 days, followed by 10 to 20 mg daily for an additional 2 weeks, have also been used in more severe cases.112 Because of the potential side effects, administration of systemic steroids should be prescribed and monitored by a dermatologist. Other treatment modalities (e.g., retinoids, hydroxychloroquine, cyclosporine, azathioprine, cyclophosphamide, or free gingival grafts) have also been used.112,119 A promising therapeutic agent, tacrolimus (0.1% Protopic ointment, twice daily), is an immunosuppressant that is effective in controlling lesions of erosive lichen planus.72,91,104,144

Because candidiasis is often associated with symptomatic oral lichen planus and topical steroid therapy promotes fungal growth, treatment should also include a topical antifungal agent.16,52,67

Pemphigoid

The term pemphigoid applies to a number of cutaneous, immune-mediated, subepithelial bullous diseases characterized by a separation of the basement membrane zone, including bullous pemphigoid, mucous membrane pemphigoid, and pemphigoid (herpes) gestationis.118,140 Among these conditions, bullous pemphigoid and mucous membrane pemphigoid, also known as benign mucous membrane pemphigoid and cicatricial pemphigoid, have received considerable attention. Current molecular findings on these two diseases clearly indicate that they are separate entities.140 However, considerable histologic and immunopathologic overlap exists between the two diseases, so their differentiation may be impossible based on these two criteria.118 In many cases, the clinical findings are probably the best cognitive element to discriminate between them. Accordingly, the term bullous pemphigoid is preferred when the disease is nonscarring and mainly affects the skin. The term cicatricial pemphigoid is favored when scarring occurs and the disease is mainly confined to mucous membranes (although scarring may be absent in some subtypes of mucous membrane pemphigoid).157 Until more research allows better understanding of this family of diseases, bullous pemphigoid and mucous membrane pemphigoid are discussed separately.

Bullous Pemphigoid

Bullous pemphigoid is a chronic, autoimmune, subepidermal bullous disease with tense cutaneous bullae that rupture and become flaccid (Figure 12-11). Oral involvement occurs in about a third of the patients.148

Figure 12-11 Bullous pemphigoid. Coalescing cutaneous bullae are seen, some of them are hemorrhagic. Rupture of bullae leads to formation of serpiginous ulcers.

Although the skin lesions of bullous pemphigoid clinically resemble those of pemphigus, the microscopic picture is quite distinct.

Histopathology

There is no evidence of acantholysis, and the developing vesicles are subepithelial rather than intraepithelial. The epithelium separates from the underlying connective tissue at the basement membrane zone. Electron microscopic studies show an actual horizontal splitting or replication of the basal lamina. The separating epithelium remains relatively intact, and the basal layer is present and appears to be regular. The two major antigenic determinants for bullous pemphigoid are the 230 kD protein plaque known as BP1 and the 180 kD collagen-like transmembrane protein BP2.105,121,129

Immunofluorescence

Immunologically, bullous pemphigoid is characterized by immunoglobulin G (IgG) and complement 3 (C3) immune deposits along epithelial basement membranes and circulating IgG antibodies to the epithelial basement membrane.71,109 Direct immunofluorescence is positive in 90% to 100% of these patients, whereas indirect immunofluorescence is positive in 40% to 70% of affected patients110 (see Table 12-1).

Oral Lesions

Oral lesions have been reported to occur secondarily in up to 40% of cases. There is an erosive or desquamative gingivitis presentation and occasional vesicular or bullous lesions.148

Treatment

Because its etiologic factors are unknown, treatment of bullous pemphigoid is designed to control its signs and symptoms.71,109 The primary treatment is a moderate dose of systemic prednisone. Steroid-sparing strategies (prednisone plus other immunomodulator drugs) are used when high doses of steroids are needed or the steroid alone fails to control the disease.38 For localized lesions of bullous pemphigoid, high-potency topical steroids or tetracycline, with or without nicotinamide, can be effective.112

Mucous Membrane Pemphigoid (Cicatricial Pemphigoid)

Mucous membrane pemphigoid, also known as cicatricial pemphigoid, is a chronic, vesiculobullous autoimmune disorder of unknown cause that predominantly affects women in the fifth decade of life. Although rare, it has been reported in young children.22,106,140

Cicatricial pemphigoid involves the oral cavity, conjunctiva, and the mucosa of the nose, vagina, rectum, esophagus, and urethra. In about 20% of patients, however, the skin may also be involved. Recent investigations suggest that cicatricial pemphigoid encompasses a group of heterogeneous conditions with distinct clinical and molecular features.33,101,133 An elaborate cascade of events is involved in the pathogenesis of cicatricial pemphigoid. Initially, antigen-antibody complexing occurs at the basement membrane zone, followed by complement activation and subsequent leukocyte recruitment. Next, proteolytic enzymes are released and dissolve or cleave the basement membrane zone, usually at the level of the lamina lucida.45 The two major antigenic determinants for cicatricial pemphigoid are bullous pemphigoid 1 and 2 (BP1 and BP2). Most cases of cicatricial pemphigoid are the result of an immune response directed against BP2 and less often against BP1, epiligrin (laminin-5, a lamina lucida protein in basement membrane of stratified epithelium), and β-4 integrins.8,20,33

Current research strongly suggests that there are at least five subtypes of cicatricial pemphigoid: oral pemphigoid, antiepiligrin pemphigoid, anti-BP antigen mucosal pemphigoid, ocular pemphigoid, and multiple-antigens pemphigoid.140 Recent studies have shown that the sera of ocular pemphigoid patients recognize β4 integrin subunit while patients with oral pemphigoid recognize the βα6 unit.124

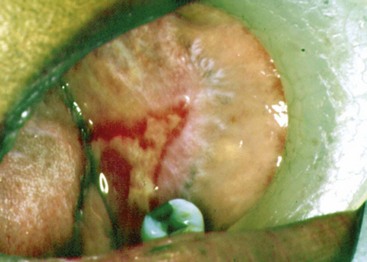

Ocular Lesions

In cases presenting first to the dentist (mainly desquamative gingivitis), the eyes are affected in approximately 25% of patients.110 In contrast, in cases presenting first to the dermatologist, 66% of patients present with conjunctival lesions, whereas in ophthalmic studies, 100% of the patients have ocular involvement.51,81,102,103 The initial lesion is characterized by unilateral conjunctivitis that becomes bilateral within 2 years. Subsequently, there may be adhesions of eyelid to eyeball (symblepharon) (Figure 12-12). Adhesions at the edges of the eyelids (ankyloblepharon) may lead to a narrowing of the palpebral fissure. Small vesicular lesions may develop on the conjunctiva, which may eventually produce scarring, corneal damage, and blindness.

Oral Lesions

The most characteristic feature of oral involvement is the presence of desquamative gingivitis, typically with areas of erythema, desquamation, ulceration, and vesiculation, of the attached gingiva53,146 (Figure 12-13). Vesiculobullous lesions may occur elsewhere in the mouth.53 The bullae tend to have a relatively thick roof and rupture in 2 to 3 days, leaving irregularly-shaped areas of ulceration. Healing of the lesions may take up to 3 weeks or longer.

Figure 12-13 Gingival mucous membrane pemphigoid. Lesions are confined to the gingival tissues, producing a typical desquamative gingivitis appearance.

(Courtesy Dr. Stuart L. Fischman, State University of New York at Buffalo.)

Histopathology

The microscopic appearance of the oral lesions, although not completely diagnostic for mucous membrane pemphigoid, is sufficiently distinctive that a tentative diagnosis can be considered. A striking subepithelial vesiculation, with the epithelium separated from the underlying lamina propria, leaves an intact basal layer (Figure 12-14). The separation of the epithelium and the connective tissue occurs at the basement membrane zone. Electron microscopic studies demonstrate a split in the basal lamina.154 A mixed inflammatory infiltrate (lymphocytes, plasma cells, neutrophils, and scarce eosinophils) is observed in the underlying fibrous connective tissue.

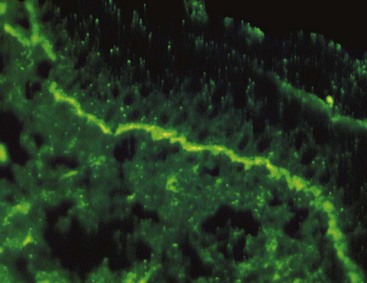

Immunofluorescence

Positive findings along the basement membrane area have been reported using both direct and indirect immunofluorescence.34,70,76 In biopsy tests by direct immunofluorescence, the main immunoreactants are IgG and C3, which are confined to the basement membrane (Figure 12-15). Some studies indicate that positive indirect immunofluorescence is rare in these patients (<25%).96 The lack of indirect immunofluorescence findings may be caused by an earlier diagnosis of mucous membrane pemphigoid, resulting in the identification of patients with less extensive disease.2,79 In any event, circulating autoantibodies do not appear to play a role in the pathogenesis of the disease.

Differential Diagnosis

Several disease entities present with similar clinical and histologic (subepithelial bulla) features.40 These include bullous pemphigoid, bullous lichen planus, dermatitis herpetiformis, LAD, erythema multiforme, herpes gestationis, and epidermolysis bullosa acquisita.

Pemphigus may be confined to the oral cavity in its early stage, and the vesicular and ulcerative lesions may resemble those of mucous membrane pemphigoid. An erosive or desquamative gingivitis may also be seen in pemphigus as a rare manifestation. Biopsy studies can quickly rule out pemphigus by revealing the absence or presence of acantholytic changes. In erythema multiforme, there are obvious vesiculobullous lesions, but the onset is usually acute rather than chronic, labial involvement is severe, and the gingivae are usually not affected. Desquamative gingivitis is an unusual finding in erythema multiforme, although occasional vesicular lesions may develop. A biopsy study of an oral lesion reveals an unusual degeneration of the upper stratum spinosum, characteristically seen in oral erythema multiforme lesions.

Cicatricial pemphigoid must be differentiated from epidermolysis bullosa acquisita, which can present with similar histopathology and immunopathology. When the biopsy is treated with salt to separate the dermis from the epidermis, basement membrane immunodeposits occur on the epidermal side in pemphigoid and the dermal side in epidermolysis bullosa acquisita.44

Treatment

Topical steroids are the mainstay of treatment for mucous membrane pemphigoid, particularly when localized lesions are present. Fluocinonide (0.05%) and clobetasol propionate (0.05%) in an adhesive vehicle can be used three times a day for up to 6 months. When the oral lesions of mucous membrane pemphigoid are confined to the gingival tissues, topical corticosteroids are effectively delivered with vacuum-formed custom trays or veneers.140 Optimal oral hygiene is essential because local irritants on the tooth surface result in an exaggerated gingival inflammatory response. Gingival irritation from any dental prosthesis should also be minimized.

If the disease is not severe and symptoms are mild, systemic corticosteroids may be omitted. If ocular involvement exists, systemic corticosteroids are indicated.

When lesions do not respond to steroids, systemic dapsone (4-4′-diaminodiphenylsulfone) has proved to be effective.28,49,101,108 Because of the systemic side effects to dapsone, including hemolysis and methemoglobinemia, particularly in patients with glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase deficiency, referral to a dermatologist is often indicated.115 Systemic steroids can also be combined with azathioprine or cyclophosphamide.7,137 Some authors also advocate sulfonamides and tetracycline; surgery, although not a treatment for mucous membrane pemphigoid, is used in some patients to prevent blindness, as well as esophageal and upper airways stenosis.140 Connective tissue grafting to alleviate root surface sensitivity and improve esthetics has been used with success to manage gingival recession in a patient with cicatricial pemphigoid.84

Pemphigus Vulgaris

The pemphigus diseases are a group of autoimmune bullous disorders that produce cutaneous and mucous membranes blisters (Figures 12-16 and 12-17). Pemphigus vulgaris is the most common of the pemphigus diseases, which also include pemphigus foliaceous, pemphigus vegetans, and pemphigus erythematosus.128 Pemphigus vulgaris is a potentially lethal, chronic condition (10% mortality rate) with a worldwide incidence of 0.1 to 0.5 cases per year per 100,000 individuals.12,128,135 A predilection in women, usually after the fourth decade of life, has been observed.112 However, pemphigus vulgaris has also been reported in unusually young children and even in newborns.26,128,143,158

Figure 12-16 Cutaneous lesion of patient with pemphigus vulgaris. A large bulla is present in the flexor surface of the wrist.

Figure 12-17 Pemphigus vulgaris of the oral cavity. Multiple and coalescent areas of ulceration are covered by pseudomembranes of necrotic epithelium. This patient presented with large ulcers in the labial mucosa, tongue, and soft palate.

The epidermal and mucous membrane blisters occur when the cell-to-cell adhesion structures are damaged by the action of circulating and in vivo binding of autoantibodies to the pemphigus vulgaris antigens, which are cell surface glycoproteins present in keratinocytes. These pemphigus vulgaris glycoproteins are members of the desmoglein (DSG) subfamily of the cadherin superfamily of cell-cell adhesion molecules, which are present in desmosomes.78 Whereas high levels of desmoglein 3 (Dsg3) autoantibodies correlate with severity of oral disease in patients with pemphigus vulgaris, elevated levels of desmoglein 1 (Dsg1) autoantibodies are associated with severity of cutaneous disease.60 Recent evidence suggests that DSG3, the gene coding for pemphigus vulgaris, is located in chromosomes.18

Most cases of pemphigus vulgaris are idiopathic. However, medications, such as penicillamine and captopril, can produce drug-induced pemphigus, which is usually reversible on withdrawal of the causative drug. Paraneoplastic pemphigus is antigenically distinct from pemphigus vulgaris and is associated with underlying malignancies.107

In approximately 60% of patients with pemphigus vulgaris, the oral lesions are the first sign of the disease and may herald the dermatologic involvement by a year or more.98,149

Oral Lesions

Oral lesions can range from small vesicles to large bullae. When the bullae rupture, they leave extensive areas of ulceration (Figure 12-18). Virtually any region of the oral cavity can be involved, but multiple lesions often develop at sites of irritation or trauma. The soft palate is more often involved (80%), followed by the buccal mucosa (46%), ventral aspect or dorsum of tongue (20%), and lower labial mucosa (10%). Oral lesions of pemphigus vulgaris are confined less often to the gingival tissues.75 In these patients, a clinical diagnosis of erosive gingivitis or desquamative gingivitis is seen as the sole manifestation of oral pemphigus.

Figure 12-18 Pemphigus vulgaris of the gingiva. Clinical appearance of patient with oral lesions confined to the gingivae that were clinically diagnosed as “consistent with desquamative gingivitis.”

(Courtesy Dr. Beatriz Aldape, Faculty of Odontology, National Autonomous University of Mexico (UNAM), Mexico City.)

Histopathology

Lesions of pemphigus demonstrate a characteristic intraepithelial separation, which occurs above the basal cell layer. The intraepithelial vesiculation begins as a microscopic alteration (Figure 12-19) and gradually results in a grossly visible, fluid-filled bulla. Occasionally the entire superficial layers of epithelium are lost, leaving only the basal cells attached to the underlying lamina propria, conferring a characteristic “tombstone” appearance to the epithelial cells. Acantholysis, a separation of the epithelial cells of the lower stratum spinosum, takes place and is characterized by the presence of round rather than polyhedral epithelial cells. The intercellular bridges are lost, and the nuclei are large and hyperchromatic.32,80,161 The underlying connective tissue usually presents as a mild-to-moderate, chronic inflammatory cell infiltrate. As the vesicle or bulla ruptures, the ulcerated lesion becomes infiltrated with polymorphonuclear leukocytes (PMNs), and the surface may show suppuration.

Figure 12-19 Microscopic features of pemphigus vulgaris. Typical intraepithelial clefting with “tombstone” appearance of basal cells, which remain attached to subjacent basement membrane and fibrous connective tissue. Acantholysis of epithelial cells with formation of “Tzanck” cells is seen in the intraepithelial cleft. (H&E stain; ×100.)

Immunofluorescence

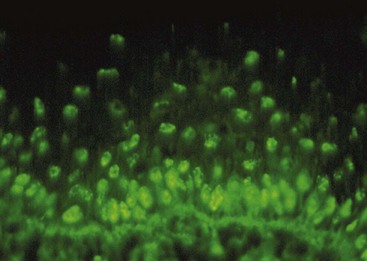

The presence of autoantibodies can be demonstrated in the oral mucosa of patients with oral pemphigus by the use of immunofluorescence techniques. For direct immunofluorescence, perilesional unfixed frozen sections are incubated with fluorescein-labeled human anti-IgG. In indirect immunofluorescence, unfixed frozen sections of oral or esophageal mucosa from an animal such as a monkey is first incubated with the patient’s serum to allow attachment of any serum antibodies to the mucosal tissue. The tissue is then incubated with fluorescein-labeled, antihuman IgG serum. The test is positive if immunofluorescence is observed in the intercellular spaces of the stratified squamous epithelium of the mucosa (Figure 12-20).

Figure 12-20 Direct immunofluorescence of oral pemphigus. Positive intercellular signal for immunoglobulin G (IgG) deposits is seen in keratinocytes of the stratified squamous epithelium.

The indirect technique is less sensitive than the direct technique and may be negative in early stages of the disease, particularly in localized forms (see Table 12-1). In most cases, however, the indirect immunofluorescence titers are helpful to monitor disease activity and have prognostic value.

Differential Diagnosis

The oral lesions of pemphigus vulgaris may be similar to those seen in erythema multiforme. In erythema multiforme, however, recurrent active episodes of comparatively short duration are followed by long intervals free of skin or oral lesions. Erythema multiforme affects the lips with considerable severity. Microscopic examination with conventional H&E and direct immunofluorescence can discriminate oral lesions of pemphigus from those of erythema multiforme. Pemphigus vulgaris will show characteristic intraepithelial clefting at the basal-spinous cell layers and interface with acantholysis, whereas erythema multiforme shows microvesiculation of the superficial epithelial layers and numerous necrotic keratinocytes. Pemphigus vulgaris shows an intercellular and intraepithelial signal with direct immunofluorescence. In contrast, erythema multiforme exhibits negative immunofluorescence.

Pemphigoid may clinically resemble pemphigus. Microscopic examination and direct immunofluorescence studies are needed to establish a correct diagnosis. Bullous pemphigoid and mucous membrane pemphigoid exhibit detachment of the epithelium from the underlying connective tissue (“lifting off”), instead of the acantholytic lesion characteristic of pemphigus.

Bullous lichen planus must also be considered in the differential diagnosis. The primary lesion of pemphigus may be of a bullous character, followed by erosion with associated pain and discomfort. In lichen planus, however, the characteristic reticular lesions are invariably found associated with the bullae. Microscopic examination and direct immunofluorescence studies are necessary to differentiate this condition from pemphigus. Bullous lichen planus shows separation of the epithelium from the underlying fibrous connective tissue, “sawtooth” rete pegs, and a bandlike, chronic inflammatory infiltrate in the lamina propria. Direct immunofluorescence reveals linear fibrillar deposits of fibrin in the basement membrane of bullous lichen planus, whereas pemphigus vulgaris has intercellular immunoglobulin deposition within the epithelium.

If the oral lesions of pemphigus vulgaris are restricted to the gingival tissues, erosive lichen planus, pemphigoid, LAD, and chronic ulcerative stomatitis should be ruled out.

Treatment

The main therapy for pemphigus vulgaris is systemic corticosteroids with or without the addition of other immunosuppressive agents.149 If the patient responds well to corticosteroids, the dosage can be gradually reduced, but a low maintenance dosage is usually necessary to prevent or minimize the recurrence of lesions. Many dermatologists monitor the dose of steroids by periodic evaluation of the titers of DsG3 and DsG1 antibodies. Increasing titers are often associated with an impending exacerbation and warrant an increase of the steroid dose. A decrease in titer justifies a reduction of the steroid dose.23 In patients not responsive to corticosteroids or who gradually adapt to them, “steroid-sparing” therapies are used; these consist of combinations of steroids plus other medications, such as azathioprine, cyclophosphamide, cyclosporine, dapsone, gold, and methotrexate, as well as photoplasmapheresis and plasmapheresis.112 Rituximab is an anti-CD20 monoclonal antibody aimed to remove desmoglein-reactive autoantibodies that is currently being evaluated as an adjunct to treat pemphigus vulgaris.43,141

The maintenance phase aims to control the disease with the lowest dose of medication. To minimize the risk of morbidity associated with the long-term use of steroids, alternate-day steroid therapy, steroid-sparing drugs, and topical steroids can be combined. Because topical steroids may promote the development of candidiasis, topical antifungal medication may also be needed.90

Minimizing oral irritation is important in patients with oral pemphigus vulgaris. Optimal oral hygiene is essential because there is usually widespread involvement of the marginal and attached gingivae in pemphigus vulgaris, as well as in other areas of the mouth, which can be exacerbated by plaque-associated gingivitis and periodontitis. Periodontal care is an important issue of the overall management of patients with pemphigus vulgaris. To prevent flare-ups, patients in the maintenance phase should receive prednisone before professional oral prophylaxis and periodontal surgery.128 In addition, the fit and design of removable prosthetic appliances should receive special attention because even slight irritation from these prostheses can cause severe inflammation with vesiculation and ulceration.

Chronic Ulcerative Stomatitis

Chronic ulcerative stomatitis, first reported in 1990,68 clinically presents with chronic oral ulcerations and has a predilection for women in their fourth decade of life. The erosions and ulcerations present predominantly in the oral cavity, with only a few cases exhibiting cutaneous lesions.25,82,159

Oral Lesions

Painful, solitary small blisters and erosions with surrounding erythema are present mainly on the gingiva and the lateral border of the tongue. Because of the magnitude and clinical features of the gingival lesions, a diagnosis of desquamative gingivitis is considered (Figure 12-21). The buccal mucosae and hard palate may also present similar lesions.152

Figure 12-21 Chronic ulcerative stomatitis. Erythema and ulceration of the gingiva consistent with a clinical diagnosis of desquamative gingivitis. Direct and indirect immunofluorescence studies demonstrate the presence of stratified epithelium–specific antinuclear antibodies (SES-ANA).

(Courtesy Dr. Douglas Damm, University of Kentucky, Lexington.)

Histopathology

The microscopic features of chronic ulcerative stomatitis are similar to those observed in erosive lichen planus. Hyperkeratosis, acanthosis, and liquefaction of the basal cell layer with areas of subepithelial clefting are prominent features of the epithelium. The underlying lamina propria exhibits a lymphohistiocytic, chronic infiltrate in a bandlike configuration.

Immunofluorescence

Direct immunofluorescence of normal and perilesional tissues reveals typical stratified epithelium–specific antinuclear antibodies (SES-ANA). These are nuclear deposits of IgG with a speckled pattern, mainly in the basal cell layer of the normal epithelium (Figure 12-22). In addition, fibrin deposits are visualized at the epithelial tissue–connective tissue interface. Indirect immunofluorescence studies using an esophageal substrate also reveal the presence of SES-ANA.153

Diagnosis

Chronic ulcerative stomatitis is clinically similar to erosive lichen planus. In addition, pemphigus vulgaris, mucous membrane pemphigoid, LAD, bullous pemphigoid, and lupus erythematosus have to be included in the clinical differential diagnosis. Microscopic examination usually reduces the number of possibilities to chronic ulcerative stomatitis, LAD, and erosive lichen planus. Direct and indirect immunofluorescence studies are needed to arrive at the correct diagnosis.

Treatment

For mild cases, topical steroids (fluocinonide, clobetasol propionate) and topical tetracycline may produce clinical improvement; however, recurrences are common.85 For severe cases, a high dose of systemic corticosteroids is needed to achieve remission. Unfortunately, reduction of the corticosteroid dose results in relapse of the lesions. Hydroxychloroquine sulfate at a dosage of 200 to 400 mg per day seems to be the treatment of choice to produce complete, long-lasting remission.13,27,65,68 However, a long-term follow-up study demonstrated that combined therapy (small doses of corticosteroids and chloroquine) may be required because the initial good response to chloroquine ceases after several months or even years of treatment.25

Linear Immunoglobulin A Disease (Linear Immunoglobulin A Dermatosis)

Linear IgA disease (LAD), also known as linear IgA dermatosis, is an uncommon mucocutaneous disorder with a predilection for women. The etiopathogenic aspects of LAD are not fully understood, although drug-induced LAD triggered by angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors has been reported.48 LAD clinically presents as a pruritic vesiculobullous rash, usually during middle age and later, although younger individuals may be affected. Characteristic plaques or crops with an annular presentation surrounded by a peripheral rim of blisters affect the skin of the upper and lower trunk, shoulders, groin, and lower limbs. The face and perineum may also be affected. Mucosal involvement, including the oral mucosa, ranges from 50% to 100% of the cases published.21,29,69

LAD may mimic lichen planus both clinically and histologically. Immunofluorescence studies are needed to establish the correct diagnosis.

Oral Lesions

Oral manifestations of LAD consist of vesicles, painful ulcerations or erosions, and erosive gingivitis/cheilitis. The hard and soft palates are affected more often; tonsillar pillars, buccal mucosa, tongue, and gingiva follow in frequency. Rarely, oral lesions may be the only manifestation of LAD for several years before the presentation of cutaneous lesions.19 In addition, oral lesions of LAD have been clinically reported as desquamative gingivitis37,116,120,121 (Figure 12-23).

Immunofluorescence

Linear deposits of IgA are observed at the epithelial tissue–connective tissue interface. They differ from the granular pattern observed in dermatitis herpetiformis.

Differential Diagnosis

The differential diagnosis of LAD includes erosive lichen planus, chronic ulcerative stomatitis, pemphigus vulgaris, bullous pemphigoid, and lupus erythematosus. Microscopic examination and immunofluorescence studies are necessary to establish the correct diagnosis.

Treatment

The primary treatment for LAD is a combination of sulfones and dapsone. Small amounts of prednisone (10 to 30 mg/day) can be added if the initial response is inadequate.24 Alternatively, tetracycline (2 g/day) combined with nicotinamide (1.5 g/day) have shown promising results.117 Recently, mycophenolate (1 g twice daily [bid]) combined with prednisolone (30 mg daily) resulted in the resolution of refractory ulcerations associated with LAD.83

Dermatitis Herpetiformis

Dermatitis herpetiformis is a chronic condition that usually develops in young adults (ages 20 to 30 years) and has a slight predilection for men.39 Currently, evidence indicates that dermatitis herpetiformis is a cutaneous manifestation of celiac disease. Approximately 25% of patients with celiac disease have dermatitis herpetiformis. The etiology of celiac disease is obscure; however, tissue transglutaminase seems to be the predominant autoantigen in the intestine, skin, and sometimes mucosae.31 Gluten enteropathy can be severe in about two-thirds of patients and mild or subclinical in the remaining third. In severe cases, patients may complain of dysphagia, weakness, diarrhea, and weight loss.93

Clinically, dermatitis herpetiformis presents with bilateral and symmetric pruritic papules or vesicles primarily restricted to the extensor surfaces of the extremities. The sacrum, buttocks, and occasionally the face, as well as the oral cavity, may also be affected.15,39 The name “herpetic” derives from the initial presentation of this disease, in which clusters of vesicles or papules arise on the skin. These vesicles or papules eventually resolve and are followed by hyperpigmentation of the skin, which ultimately wanes. The oral lesions of dermatitis herpetiformis range from painful ulcerations preceded by the collapse of ephemeral vesicles or bullae to erythematous lesions.111

Histopathology

Microscopic examination of the initial lesions of dermatitis herpetiformis reveals focal aggregates of neutrophils and eosinophils among deposits of fibrin at the apices of the dermal pegs.162

Immunofluorescence

Direct immunofluorescence shows that IgA and C3 are present at the dermal papillary apices. These findings are present in perilesional and normal, uninvolved tissue. In contrast, biopsies taken from lesional sites may fail to exhibit IgA or C3, resulting in false-negative results.162 Although no circulating autoantibodies to epithelial basement membrane are present in dermatitis herpetiformis, almost 80% of patients have antiendomysial and gliadin antibodies.14

Lupus Erythematosus

Lupus erythematosus is an autoimmune disease with three different clinical presentations: systemic, chronic cutaneous, and subacute cutaneous.

Systemic Lupus Erythematosus

Systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) is a severe disease with a predilection for women over men (10 : 1) that affects vital organs such as the kidneys and heart, as well as the skin and mucosa. The classic cutaneous lesions characterized by the presence of a rash on the malar area with a butterfly distribution are actually uncommon35 (Figure 12-24). The oral lesions of SLE are usually ulcerative or similar to lichen planus. Oral ulcerations present in 36% of patients with SLE. In about 4% of patients, hyperkeratotic plaques reminiscent of lichen planus appear on the buccal mucosa and palate.17 Direct immunofluorescence of the perilesional and normal tissue reveals immunoglobulins and C3 deposits at the dermal-epidermal interface. Antinuclear antibodies (ANA) are present in more than 95% of cases, whereas deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA) and extractable nuclear antigen (ENA) antibodies are present in more than 50% of patients (see Table 12-1).

Chronic Cutaneous Lupus Erythematosus

Chronic cutaneous lupus erythematosus (CCLE) usually has no systemic signs or symptoms, with lesions being limited to skin or mucosal surfaces. The skin lesions are referred to as discoid lupus erythematosus (DLE). DLE merely describes the chronic scarring, atrophy-producing lesion that may develop into hyperpigmentation or hypopigmentation of the healing area (Figure 12-25). In the oral cavity, about 9% of patients with CCLE present lichen planus–like plaques on the palate and buccal mucosa.5,17 The gingiva may be affected and clinically present as desquamative gingivitis (Figure 12-26).

Figure 12-25 Chronic cutaneous lupus erythematosus. Multiple facial lesions with irregular hyperpigmented borders, some of which exhibit central scarring with cutaneous atrophy. Other lesions consist of hyperpigmented cutaneous patches.

Figure 12-26 Lupus erythematosus of the oral cavity presenting as desquamative gingivitis. Intense erythema with ulceration is bordered by white radial lines.

(Courtesy Dr. Stuart L. Fischman, State University of New York at Buffalo.)

Histopathology

The histopathology of the oral lesions of chronic cutaneous lupus erythematosus consists of hyperkeratosis, alternated acanthosis and atrophy, and hydropic degeneration of the basal layer of the epithelium. The lamina propria exhibits a chronic inflammatory cell infiltrate similar to that observed in lichen planus. However, a more diffuse and deeper inflammatory infiltrate with a perivascular pattern is typically observed.147

Direct immunofluorescence of lesional tissue reveals immunoglobulins and C3 deposits at the dermal-epidermal junction of the lesional or perilesional tissue but not in normal tissue. This seems to differentiate SLE from DLE. Indirect immunofluorescence reveals the presence of ANAs in more than 95% of patients, whereas DNA- and ENA-circulating antibodies are present in more than 50%.

Subacute Cutaneous Lupus Erythematosus

Patients with subacute cutaneous lupus erythematosus (SCLE) present cutaneous lesions that are similar to DLE but lack the development of scarring and atrophy.18 In addition, arthritis/arthralgia, low-grade fever, malaise, and myalgia may present in up to 50% of SCLE patients.18,155 Direct immunofluorescence reveals immunoglobulins and C3 deposits at the dermal-epidermal junction in 60% of cases, and granular IgG deposits in the cytoplasm of basal cells in 30%. About 80% of patients with SCLE have Ro (SSA) antibodies to nuclear antigens, whereas 25% to 30% have La (SSB) antibodies to nuclear antigens. Rheumatoid factor (RF) is positive in about 30% of these patients, ANA is positive in 60% to 90%, and 10% of cases have antiribonucleoprotein (anti-RNP) antibodies to nuclear antigens (see Table 12-1).

Differential Diagnosis

Erosive lichen planus, erythema multiforme, and pemphigus vulgaris may sometimes simulate the lesions observed in lupus erythematosus. The diagnosis of DLE confined to the oral cavity is difficult to make, but microscopic studies may suggest the characteristic histopathology.4 Biopsy studies (H&E and direct immunofluorescence) aid in differentiating between lupus erythematosus and other erosive diseases.

Treatment

The therapy for SLE depends on the severity and extent of the disease ranging from topical steroids to nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drug (NSAIDs) and for severe systemic organ involvement, moderate-to-high doses of prednisone. Immunosuppressive drugs, such as cytotoxic agents (cyclophosphamide and azathioprine), and plasmapheresis alone or with steroids are useful.112 Recently, rituximab has been utilized and produced dramatic long-term remissions.35 For CCLE, topical steroids are effective to manage the cutaneous and oral lesions. For patients resistant to topical therapy, systemic antimalarial drugs may be used with good results.110

Erythema Multiforme

Erythema multiforme (EM) is an acute bullous and macular inflammatory mucocutaneous disease that affects mainly young adults 20 to 40 years of age and rarely children (up to 20%).134 The genesis of the mucocutaneous lesions is believed to reside in the development of immune complex vasculitis. This is followed by complement fixation, leading to leukocytoclastic destruction of vascular walls and small vessel occlusion. The culmination of these events produces ischemic necrosis of the epithelium and underlying connective tissue.45 Target or “iris” lesions with central clearing are the “hallmark” of erythema multiforme. It may be a mild condition (erythema multiforme minor) or a severe, possibly life-threatening condition (erythema multiforme major, or Stevens-Johnson syndrome). An underdiagnosed type of erythema multiforme is the oral form in which most patients have chronic or recurrent oral lesions only.6

Erythema multiforme minor lasts approximately 4 weeks and exhibits a moderate cutaneous and mucosal involvement. Stevens-Johnson syndrome may last a month or longer and involves the skin, conjunctiva, oral mucosa, and genitalia, requiring more aggressive therapy. Some researchers consider toxic epidermal necrolysis as the most severe form of erythema multiforme; however, other investigators believe that these are unrelated entities.10 The two most common etiologic factors for the development of erythema multiforme are (1) herpes simplex infection and (2) drug reactions. The most common causative drugs are sulfonamides, penicillins, quinolones, chlormezanone, barbiturates, oxicam NSAIDs, anticonvulsant drugs, protease inhibitors, and allopurinol.46

Oral lesions in erythema multiforme are common and present in more than 70% of patients with skin involvement.47,89,95 In rare instances, however, erythema multiforme may be confined to the mouth.6,86,138 The oral lesions consist of multiple, large, shallow painful ulcers with an erythematous border. They may affect the entire oral mucosa in approximately 20% of patients with erythema multiforme. The lesions are so painful that chewing and swallowing are impaired (Figure 12-27). The buccal mucosa and tongue are the most frequently affected sites, followed by the labial mucosa. Less often affected are the floor of the mouth, hard and soft palate, and the gingiva.47 There are rare instances in which erythema multiforme may be confined exclusively to the gingival tissues, resulting in a clinical diagnosis of desquamative gingivitis.9 Hemorrhagic crusting of the vermilion border of the lips may occur, which is helpful in arriving at a clinical diagnosis of erythema multiforme.

Figure 12-27 Erythema multiforme. Large, shallow, and painful ulcers involving the labial and buccal mucosae. Hemorrhagic crusting of the mandibular vermilion border of the lips is observed.

(Courtesy Dr. Stuart L. Fischman, State University of New York at Buffalo.)

Histopathology

Common microscopic findings of erythema multiforme include liquefaction degeneration of the upper epithelium and development of intraepithelial microvesicles but without the acantholysis that occurs in pemphigus.145 In addition, acanthosis, pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia, and necrotic keratinocytes are observed in the epithelium. Degenerative changes also occur in the basement membrane. In some cases the junction between the epithelium and the lamina propria is indistinct because of a dense, inflammatory cell infiltrate. Edema of the lamina propria, vascular dilation, and congestion are also present. Deeper layers of the connective tissue stroma exhibit a perivascular, chronic inflammatory cell infiltrate. However, neutrophils and eosinophils may also be present.

Immunofluorescence

Immunofluorescence examination is negative in erythema multiforme. Its value resides in ruling out other vesiculobullous and ulcerative disorders.

Treatment

There is no specific treatment for erythema multiforme. For mild symptoms, systemic and local antihistamines together with topical anesthetics and debridement of lesions with an oxygenating agent are adequate. In patients with bullous or ulcerative lesions and severe symptoms, corticosteroids are considered the drug of choice, although their use is controversial and not completely accepted.46

Drug Eruptions

An increase in the incidence of skin and oral manifestations of hypersensitivity to drugs has been noted since the advent of sulfonamides, barbiturates, and various antibiotics. The cutaneous and oral lesions are attributed to the drug acting as an allergen that sensitizes the tissues.

Eruptions in the oral cavity resulting from sensitivity to drugs that have been taken by mouth or parenterally are termed stomatitis medicamentosa. The local reaction from the use of a medicament in the oral cavity (e.g., stomatitis resulting from topical penicillin) is referred to as stomatitis venenata or contact stomatitis. In many cases, skin eruptions may accompany the oral lesions.

In general, drug eruptions in the oral cavity are multiform. Vesicular and bullous lesions occur most often, but pigmented or nonpigmented macular lesions are also frequently observed. Erosions, often followed by deep ulceration with purpuric lesions, may also occur. The lesions are seen in different areas of the oral cavity, with the gingiva often affected.1,54

The development of gingival lesions caused by contact allergy to mercurial compounds present in dental amalgam has been clearly documented.73 Because of financial considerations, biopsy and patch testing may be indicated before the indiscriminate replacement of dental amalgam restorations. Similarly, desquamative gingivitis has been reported with the use of tartar control toothpaste. Pyrophosphates and flavoring agents have been identified as the main causative agents of this unusual condition.36 Oral reactions to cinnamon compounds (cinnamon oil, cinnamic acid, or cinnamic aldehyde) used to mask the taste of pyrophosphates in tartar control toothpaste include an intense erythema of the attached gingival tissues characteristic of plasma cell gingivitis3,74 (Figure 12-28). A thorough clinical history usually discloses the source of the gingival disturbance. Elimination of the offending agent (e.g., tartar control toothpaste) leads to resolution of the gingival lesions within a week. Challenge with the offending agent leads to recurrence of the oral lesions. If removal of the offending medication is not possible, topical corticosteroids and topical tacrolimus can be used to treat the lesions.66

Miscellaneous Conditions Mimicking Desquamative Gingivitis

Another group of heterogeneous conditions may masquerade as desquamative gingivitis. Factitious lesions, candidiasis, graft-versus-host disease, Wegener’s granulomatosis, foreign body gingivitis, Kindler syndrome, and even squamous cell carcinoma can divert the attention of the clinician and result in a diagnostic challenge.

Factitious lesions are consciously and intentionally produced injuries without a clear motive, although guilt, seeking sympathy, or monetary compensation may be the driving force behind this abnormal behavior. Factitious desquamative gingivitis has been reported in the literature and may be difficult to diagnose and may become apparent only after extensive and costly laboratory tests fail to reveal the genesis of the lesions.96

Candidiasis may rarely be limited to the gingival tissues and may simulate desquamative gingivitis. Linear gingival erythema is a Candida-associated lesion in individuals infected with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) in which a ribbonlike red band of the gingival margins is present and reminiscent of desquamative gingivitis.132

Graft-versus-host disease may occur in recipients of allogenic bone marrow transplants, whose oral lesions may occasionally resemble desquamative gingivitis (Figure 12-29).

Figure 12-29 Graft-versus-host disease in recipient of allogeneic bone marrow transplant. The maxillary gingiva exhibits features consistent with desquamative gingivitis.

(Courtesy Dr. Linda Lee, University of Toronto.)

Wegener’s granulomatosis is a systemic disease that may initially present with striking alterations that are confined to the gingival tissues. Classically, the gingival tissues exhibit erythema and enlargement and are typically described as “strawberry gums”30 (Figure 12-30).

Figure 12-30 Wegener’s granulomatosis affecting gingival tissues. The classic “strawberry gums” appearance of the mandibular gingiva is seen in this patient. A slight resemblance with desquamative gingivitis is evident.

Foreign body gingivitis is clinically characterized by red or red and white chronic lesions that may be painful and are reminiscent of desquamative gingivitis. This condition is more common in women approaching the fifth decade of life. Microscopic analysis reveals small (<5 µm in diameter) foreign bodies associated with a chronic inflammatory cell response that may exhibit granulomatous and lichenoid characteristics. Energy-dispersive x-ray microanalysis has revealed that most of these foreign bodies originate as dental materials (more specifically, abrasives and restorative material).58,59

Kindler syndrome (cutaneous neonatal bullae, poikiloderma, photosensitivity, and acral atrophy) may also present with oral lesions that are clinically consistent with desquamative gingivitis.126

Failure to evaluate properly and systematically a patient with a clinical condition that is consistent with desquamative gingivitis can lead to unpleasant outcomes. This is particularly true when therapy for a putative desquamative gingivitis is established before a biopsy of the lesional tissue is obtained. Every year we see in our laboratory at least two examples of clinically diagnosed desquamative gingivitis for which microscopic and immunofluorescence studies were not performed to rule out the genesis of the gingival lesions. In these cases the patients have been either “carefully” followed up or prescribed topical steroids for several months. The lack of response of the gingival tissues eventually impels the clinician to obtain a biopsy, which reveals that the gingival lesions are squamous cell carcinomas. Thus the clinician should be alert to the possibility of squamous cell carcinoma of the gingival tissues presenting initially as “desquamative gingivitis.”

1 Abdollahl M, Rahimi R, Radfar M. Current opinion on drug-induced oral reactions: a comprehensive review. Contemp Dent Pract. 2008;9:1.

2 Ahmed AR, Kurgis BS, Rogers RS. Cicatricial pemphigoid. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1991;24:987.

3 Allen CM, Blozis GG. Oral mucosal reactions to cinnamon-flavored chewing gum. J Am Dent Assoc. 1988;116:664.

4 Andreasen JO, Poulsen HE. Oral manifestations in discoid and systemic lupus erythematosus: histologic investigation. Acta Odontol Scand. 1964;22:389.

5 Archard HO, Roebuck NF, Stanley HR. Oral manifestations of chronic discoid lupus erythematosus. Oral Surg. 1963;16:696.

6 Ayangco L, Rogers RS3rd. Oral manifestations of erythema multiforme. Dermatol Clin. 2003;21:195.

7 Bagan J, Muzio LL, Scully C. Number III. Mucous membrane pemphigoid. Oral Diseases. 2005;11:197.

8 Balding SD, Prost C, Diaz LA. Cicatricial pemphigoid autoantibodies react with multiple sites on the BP 180 extracellular domain. J Invest Dermatol. 1996;106:141.

9 Barrett AW, Scully C, Eveson JW. Erythema multiforme involving gingiva. J Periodontol. 1993;64:910.

10 Bastuji-Garin S, Rzany B, Stern RS, et al. Clinical classification of cases of toxic epidermal necrolysis, Stevens-Johnson syndrome, and erythema multiforme. Arch Dermatol. 1993;129:92.

11 Baudet-Pommel M, Janin-Mercier A, Souteyrand P. Sequential immunopathologic study of oral lichen planus treated with tretinoin and etretinate. Oral Surg. 1991;71:197.

12 Becker BA, Gaspari AA. Pemphigus vulgaris and vegetants. Dermatol Clin. 1993;11:453.

13 Beutner EH, Chorzelski TP, Parodi A, et al. Ten cases of chronic ulcerative stomatitis with stratified epithelium-specific antinuclear antibody. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1991;24:781.

14 Beutner EH, Chorzelski TP, Reunala TL, et al. Immunopathology of dermatitis herpetiformis. Clin Dermatol. 1992;9:295.

15 Boh EE, Milikan LE. Vesiculobullous diseases with prominent immunologic features. JAMA. 1992;268:2893.

16 Brown RS, Bottomley WK, Puente E, et al. A retrospective evaluation of 193 patients with oral lichen planus. J Oral Pathol Med. 1993;22:69.

17 Burge SM, Frith PA, Juniper RP, et al. Mucosal involvement in systemic and chronic cutaneous lupus erythematosus. Br J Dermatol. 1989;121:727.

18 Callen JP, Kulick KB, Stelzer G, et al. Subacute cutaneous lupus erythematosus: clinical, serologic, and immunogenetic studies on 49 patients seen in a non-referral setting. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1986;15:1227.

19 Campisi G, Di Liberto C, Carrocio A, et al. Coeliac disease: Oral ulcer prevalence, assessment of risk and association with gluten-free diet in children. Digest Liver Disease. 2008;40:104.

20 Challacombe SJ, Setterfield J, Shirlaw P, et al. Immunodiagnosis of pemphigus and mucous membrane pemphigoid. Acta Odontol Scand. 2001;59:226.

21 Chan LS, Regezi JA, Cooper KD. Oral manifestations of linear IgA disease. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1990;22:362.

22 Chan LS, Ahmed AR, Anhalt GJ, et al. The first international consensus on mucous membrane pemphigoid: definition, diagnostic criteria, pathogenic factors, medical treatment, and prognostic indicators. Arch Dermatol. 2002;138:370.

23 Cheng SW, Obayashi M, Kinoshita-Kuroda K, et al. Monitoring disease activity in pemphigus with enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay using recombinant desmogleins 1 and 3. Br J Dermatol. 2002;147:261.

24 Chorzelski T, Jablonska S, Maciejowska E. Linear IgA bullous dermatosis of adults. Clin Dermatol. 1992;9:383.

25 Chorzelski T, Olszewska M, Jarzabek-Chorzelska M, et al. Is chronic ulcerative stomatitis an entity? Clinical and immunological findings in 18 cases. Eur J Dermatol. 1998;8:261.

26 Chowdhury MM, Natarajan S. Neonatal pemphigus vulgaris associated with mild oral pemphigus vulgaris in the mother during pregnancy. Br J Dermatol. 1998;139:500.

27 Church LFJr, Schosser RH. Chronic ulcerative stomatitis associated with stratified epithelial specific antinuclear antibodies: a case report of a newly described disease entity. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1992;73:579.

28 Ciarrocca KN, Greenberg MS. A retrospective study of the management of oral mucous membrane pemphigoid with dapsone. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 1999;88:159.

29 Cohen DM, Bhattacharyya I, Zunt SL, et al. Linear IgA disease histopathologically and clinically masquerading as lichen planus. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 1999;88:196.

30 Cohen RE, Cardoza TT, Drinnan AJ, et al. Gingival manifestations of Wegener’s granulomatosis. J Periodontol. 1990;61:705.

31 Collin P, Reunala T. Recognition and management of the cutaneous manifestations of celiac disease: a guide for dermatologists. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2003;4:13.

32 Combes FL, Canizares O. Pemphigus vulgaris, a clinicopathological study of one hundred cases. Arch Dermatol Syph. 1950;62:786.

33 Dabelsteen E. Molecular biological aspects of acquired bullous diseases. Crit Rev Oral Biol Med. 1998;9:162.

34 Dabelsteen E, Ullman S, Thomson K, et al. Demonstration of basement membrane autoantibodies in patients with benign mucous membrane pemphigoid. Acta Dermatol Venereol Stockh. 1974;54:189.

35 D’Cruz DP. Systemic lupus erythematosus. Br Med J. 2006;332:890.

36 DeLattre V. Factors contributing to adverse soft tissue reactions due to the use of tartar control toothpastes: report of a case and literature review. J Periodontol. 1999;70:803.

37 Del Valle AE, Martinez-Sahuquillo A, Padron JR, et al. Two cases of linear IgA disease with clinical manifestations limited to the gingiva. J Periodontol. 2003;74:879.

38 De Vita S, Neri R, Bombardieri S. Cyclophosphamide pulses in the treatment of rheumatic diseases: an update. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 1991;9:179.

39 Economopoulou P, Laskaris G. Dermatitis herpetiformis: oral lesions as an early manifestation. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1986;62:77.

40 Eisen D, Ellis CN, Duell GA, et al. Effect of topical cyclosporin rinse on oral lichen planus. N Engl J Med. 1990;323:290.

41 Eisenberg E. Lichen planus and oral cancer: is there a connection between the two? J Am Dent Assoc. 1992;123:104.

42 Eisenberg E, Krutchkoff DJ. Lichenoid lesions of oral mucosa: diagnostic criteria and their importance in the alleged relationship to oral cancer. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1992;73:699.

43 El Tal AK, Posner MR, Spigelman Z, et al. Rituximab: a monoclonal antobody to CD20 used in the treatment of pemphigus vulgaris. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2006;55:449.

44 Engel M, Ray HG, Orban B. The pathogenesis of desquamative gingivitis. J Dent Res. 1950;29:410.

45 Eversole LR. Immunopathology of oral mucosal ulcerative, desquamative and bullous diseases. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1994;77:55.

46 Farthing P, Bagan JV, Scully C. Erythema multiforme. Oral Diseases. 2005;11:261.

47 Farthing PM, Margou P, Coates M, et al. Characteristics of the oral lesions in patients with cutaneous recurrent erythema multiforme. J Oral Pathol Med. 1995;24:9.

48 Femiano F, Scully C, Gombos F. Linear IgA dermatosis induced by a new angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2003;95:169.

49 Fine JD. Management of acquired bullous diseases. N Engl J Med. 1995;5:33.

50 Foss CL, Grupe HE, Orban B. Gingivosis. J Periodontol. 1953;24:207.

51 Foster CS. Cicatricial pemphigoid. Trans Am Ophthalmol Soc. 1986;84:527.

52 Fotos PG, Vincent SD, Hellstein JW. Oral candidosis: clinical, historical and therapeutic features of 100 cases. Oral Surg. 1992;74:41.

53 Gallagher G, Shklar G. Oral involvement in mucous membrane pemphigoid. Clin Dermatol. 1987;5:19.

54 Gallagher GT. Oral mucous membrane reactions to drugs and chemicals. Curr Opin Dent. 1991;1:777.

55 Giovanni L, Scully C, Carrozzo M, et al. Current controversies in oral lichen planus: report of an international consensus meeting. Part 2. Clinical management and malignant transformation. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2005;100:164.

56 Goadby K. Diseases of the gums and oral mucous membrane. London: Henry Froude and Hodder & Staughton; 1923.

57 Gonzalez-Moles MA, Ruiz-Avila I, Rodriguez-Archilla A, et al. Treatment of severe erosive gingival lesions by topical application of clobetasol propionate in custom trays. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2003;95:688.

58 Gordon SC, Daley TD. Foreign body gingivitis: clinical and microscopic features of 61 cases. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 1997;83:562.

59 Gordon SC, Daley TD. Foreign body gingivitis: identification of the foreign material by energy-dispersive x-ray microanalysis. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 1997;83:571.

60 Harman KE, Seed PT, Gratian MJ, et al. The severity of cutaneous and oral pemphigus is related to desmoglein 1 and 3 antibody levels. Br J Dermatol. 2001;144:775.

61 Hashimoto K, Dibella R, Shklar G, et al. Electron microscopic studies of oral lichen planus. G Ital Dermatol. 1966;107:765.

62 Holmstrup P. The controversy of a premalignant potential of lichen planus is over. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1992;73:704.

63 Ingafou M, Leao JC, Porter Sr, et al. Oral lichen planus. A retrospective study of 690 British patients. Oral Diseases. 2006;12:463.

64 Ishii T. Immunohistochemical demonstration of T cell subsets and accessory cells in oral lichen planus. J Oral Pathol. 1987;15:268.

65 Islam MN, Cohen DM, Ojha J, et al. Chronic ulcerative stomatitis: diagnostic and management challenges – four new cases and review of the literature. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2007;104:194.

66 Ismail SB, Kumar SK, Zain RB. Oral lichen planus and lichenoid reactions: etiopathogenesis, diagnosis, management and malignant transformation. J Oral Sci. 2007;49:89.

67 Jainkittivong A, Kuvatanasuchati J, Pipattanagovit, et al. Candida in oral lichen planus patients undergoing topical steroid therapy. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2007;104:61.

68 Jaremko WM, Beutner EH, Kumar V, et al. Chronic ulcerative stomatitis associated with a specific immunologic marker. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1990;22:215.

69 Kelly SE, Frith PA, Millard PR, et al. A clinicopathological study of mucosal involvement in linear IgA disease. Br J Dermatol. 1988;119:161.

70 Komori A, Welton NA, Kelln EE. The behavior of the basement membrane of skin and oral lesions in patients with lichen planus, erythema multiforme, lupus erythematosus, pemphigus vulgaris, pemphigoid and epidermolysis bullosa. Oral Surg. 1966;22:752.

71 Korman NJ. Bullous pemphigoid. Dermatol Clin. 1993;11:483.

72 Laeijendecker R, Tank B, Dekker SK, et al. A comparison of treatment of oral lichen planus with topical tacrolimus and triamcinolone acetonide ointment. Acta Der Venereol. 2006;86:227.

73 Laine J, Kalimo K, Happonen R. Contact allergy to dental restorative materials in patients with oral lichenoid lesions. Contact Dermatitis. 1997;36:141.

74 Lamey PJ, Lewis MAO, Ress TD, et al. Sensitivity reaction to the cinnamonaldehyde component of toothpaste. Br Dent J. 1990;168:115.

75 Lamey PJ, Rees TD, Binnie WH, et al. Oral presentation of pemphigus vulgaris and its response to systemic steroid therapy. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1992;74:54.

76 Laskaris G, Angelopoulos A. Cicatricial pemphigoid: direct and indirect immunofluorescent studies. Oral Surg. 1981;51:48.

77 Laskaris G, Demetrou N, Angelopoulos A. Immunofluorescent studies in desquamative gingivitis. J Oral Pathol. 1981;10:398.

78 Lenz P, Amagai M, Volc-Platzer B, et al. Desmoglein 3-ELISA: a pemphigus vulgaris specific diagnostic tool. Arch Dermatol. 1999;135:142.

79 Leonard J. Immunofluorescent studies in ocular cicatricial pemphigoid. Br J Dermatol. 1988;118:209.

80 Lever WF. Pemphigus. Medicine. 1953;32:1.

81 Lever WF. Pemphigus and pemphigoid: a review of the advances made since 1964. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1979;1:2.

82 Lewis JE, Beutner EH, Rostami R, et al. Chronic ulcerative stomatitis with stratified epithelium-specific antinuclear antibodies. Int J Dermatol. 1996;35:272.

83 Lewis MAO, Yaqoob NA, Emanuel C, et al. Successful treatment of oral linear IgA disease using mycophenolate. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2007;103:483.

84 Lorenzana ER, Rees TD, Hallmon WW. Esthetic management of multiple recession defects in a patient with cicatricial pemphigoid. J Periodontol. 2001;72:230.

85 Lorenzana ER, Rees TD, Glass M, et al. Chronic ulcerative stomatitis: a case report. J Periodontol. 2000;71:104.

86 Lozada F, Silverman S. Erythema multiforme: clinical characteristics and natural history in fifty patients. Oral Surg. 1978;46:628.

87 Lozada-Nur F. Oral lichen planus and oral cancer: is there enough epidemiologic evidence? Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2000;89:265.

88 Lozada-Nur F, Miranda C. Oral lichen planus: epidemiology, clinical characteristics, and associated diseases. Semin Cutan Med Surg. 1997;16:273.

89 Lozada-Nur F, Gorsky M, Silverman SJr. Oral erythema multiforme: clinical observations and treatment of 95 patients. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1989;67:36.

90 Lozada-Nur F, Miranda C, Maliski R. Double-blind clinical trial of 0.05% clobetasole propionate ointment in orabase and 0.05% fluocinonide ointment in orabase in the treatment of patients with vesiculoerosive diseases. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1994;77:598.

91 Lozada-Nur F, Sroussi HY. Tacrolimus powder in orabase 0.1% for the treatment of oral lichen planus and oral lichenoid lesions: an open clinical trial. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2006;102:744.

92 Malmstrom M, Kontinnen YT, Jungell P, et al. Lymphocyte activation in oral lichen planus in situ. Am J Clin Pathol. 1988;89:329.

93 Marsh MN. The natural history of gluten sensitivity: defining, refining and re-defining. Q J Med. 1995;85:9.

94 McCarthy FP, McCarthy PL, Shklar G. Chronic desquamative gingivitis: a reconsideration. Oral Surg. 1960;13:1300.

95 McCarthy PL, Shklar G. Diseases of the oral mucosa, ed 2. Philadelphia: Lea & Febiger; 1980.

96 McGrath KG, Pick R, Leboff-Ries E, Patterson R. Factitious desquamative gingivitis simulating a possible immunologic disease. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 1985;75:44.

97 Mignogna MD, Fortuna G, Leuci S, et al. Nikolsky’s sign on the gingival mucosa: a clinical tool for oral health practitioners. J Periodontol. 2008;79:2241.

98 Mignogna MD, Lo Muzio L, Bucci E. Clinical features of gingival pemphigus vulgaris. J Clin Periodontol. 2001;28:489.

99 Mignogna MD, Lo Russo L, Fedele S. Gingival involvement of oral lichen planus in a series of 700 patients. J Clin Periodontol. 2005;32:1029.

100 Merritt AH. Chronic desquamative gingivitis. J Periodontol. 1933;4:30.