CHAPTER 39 Periodontal Treatment for Older Adults

Older adults are expected to compose a larger proportion of the population than in the past. Population growth among long-lived older adults contributes to this increase worldwide. For dentistry, this means that older adults are retaining more of their natural dentition. Currently, almost 70% of older adults in the United States (US) have natural teeth.12,27 However, retention of teeth may result in more teeth at risk for periodontal disease, and thus the prevalence of periodontal disease may be associated with aging. This association was addressed by Beck20 at the 1996 World Workshop on Periodontics: “It may be that risk factors do change as people age or at least the relative importance of risk factors change.”

This chapter focuses on the interrelationship between aging and oral health, with an emphasis on periodontal health.

The Aging Periodontium

Normal aging of the periodontium is a result of cellular aging. In general, cellular aging is the basis for the intrinsic changes seen in oral tissues over time. The aging process does not affect every tissue in the same way. For example, muscle tissue and nerve tissue undergo minimal renewal, whereas epithelial tissue, which is one of the primary components of the periodontium, always renews itself.

Intrinsic Changes

In epithelium, a progenitor population of cells (stem cells), situated in the basal layer, provides new cells. These cells of the basal layer are the least differentiated cells of the oral epithelium. A small subpopulation of these cells produces basal cells and retains proliferative potential of the tissue. A larger subpopulation of these cells (amplifying cells) produces cells available for subsequent maturation. This maturing population of cells continually undergoes a process of differentiation or maturation.

By definition, this differentiated cell, or epithelial cell, can no longer divide. On the other hand, the basal cell remains as part of the progenitor population of cells ready to return to the mitotic cycle and again produce both types of cells. Thus there is a constant source of renewal (Figure 39-1). In the aging process, cell renewal takes place at a slower rate and with fewer cells, so the effect is to slow down the regenerative processes. As the progenitor cells wear out and die, there are fewer and fewer of these cells to renew the dead ones. This effect is characteristic of the age-related and biologic changes that occur with aging.

Figure 39-1 Cell renewal cycle in which the basal cell produces the epithelial cell and returns to the progenitor cell population.

By the action of gerontogene(s) or replicative senescence (Hayflick’s limit and telomere shortening), the number of progenitor cells decreases. Hayflick, an American microbiologist, observed that fetal cells (i.e., fibroblasts) displayed a consistently greater growth potential (approximately 50 cumulative population doublings) than those derived from adult tissues (20 to 30 cumulative population doublings). As a result, the decreased cellular component has a concomitant effect to decrease cellular reserves and protein synthesis. This affects the oral epithelium in that the tissue becomes thin, with reduced keratinization.

Stochastic Changes

Stochastic changes occurring within cells also affect tissue (e.g., glycosylation and cross-linking produce morphologic and physiologic changes). Structures become stiffer, with a loss of elasticity and increased mineralization (fossilization). With a loss of regenerative power, structures become less soluble and more thermally stable. Somatic mutations lead to decreased protein synthesis and structurally altered proteins. Free radicals contribute to the accumulation of waste in the cell.

All these changes produce a decline in the physiologic processes of tissue. Most changes are primarily a result of aging, although some are secondary to physiologic deterioration. For example, loss of elasticity and increased resistance of the tissue may lead to decreased permeability, decreased nutrient flow, and the accumulation of wastes in the cell. Thus vascular peripheral resistance (decreased blood supply) may secondarily decrease cellular function.

Physiologic Changes

In the periodontal ligament, a decrease in the number of collagen fibers leads to a reduction or loss in tissue elasticity. A decrease in vascularity results in decreased production of mucopolysaccharides.

All these types of changes are seen in the alveolar bone. With aging, the alveolar bone shows a decrease in bone density and an increase in bone resorption and a decrease in vascularity also occurs. In contrast, however, cementum shows cemental thickness.

Functional Changes

With aging, the cells of the oral epithelium and periodontal ligament have reduced mitotic activity, and all cells experience a reduction in metabolic rate. These changes also affect the immune system and affect healing in the periodontium. There is a reduction in healing capacity and rate. Inflammation, when present, develops more rapidly and more severely. Individuals are highly susceptible to viral and fungal infections because of abnormalities in T-cell function.

Clinical Changes

Compensatory changes occur as a result of aging or disease. These changes affect the tooth or periodontium that presents the clinical condition. Gingival recession and reductions in bone height are common conditions. Attrition is a compensatory change that acts as a stabilizer between loss of bony support and excessive leveraging from occlusal forces imposed on the teeth.

In addition, a reduction in “overjet” of the teeth is seen, manifesting as an increase in the edge-to-edge contact of the anterior teeth. Typically, this is related to the approximal wear of the posterior teeth. An increase is seen in the food table area, with loss of “sluiceways,” and in mesial migration.

Functional changes are associated with reduced efficiency of mastication. Although effectiveness of mastication may remain, efficiency is reduced because of missing teeth, loose teeth, poorly fitting prostheses, or noncompliance of the patient, who may refuse to wear prosthetic appliances.

Demographics

Population Distribution

In 2000, adults 65 years of age and older were 12.0% of the US population, or 35 million people. From 2001 to 2010, this population will grow by 13%. The greatest growth will occur in those age 85 and older (29%) and those l00 and older (65%). By the mid–twenty-first century, the US population is expected to increase by 42%. During this same period, the population age 65 and older is expected to increase by 126%. Of this population, those 85 and older are expected to increase by 316%, with centenarians (age 100+) increasing by 956%.63

The increase in the aging population is the result of the dramatic increase in life expectancy during the past and present centuries. Average life expectancy was 75 years in 1990, an increase of 28 years from 1900. In 2000, life expectancy (at birth) was projected to be 77 years. Adults who reached the age of 65 in 1990 could expect to live an average of 17 additional years.62,63

Differences in population growth between urban and rural older adults have special significance for oral health. The expected increase in the proportion of older adults will be 3% larger in rural areas. Because rural older adults use dental services less than their urban counterparts, the risk for adverse changes in oral health and self-care may be greater.67

Health Status

Increased life expectancy has changed the way the public and health care policy makers and providers think about “aging.” Instead of controlling chronic disease and morbidity, aging is seen in terms of “successful aging” or “healthy aging.” This paradigm shift is based on study of what promotes health and longevity. Current research is now examining aging in terms of the physical, mental, and social well-being of older adults, not just disease or morbidity. The MacArthur Studies of Successful Aging asked the fundamental question, “What genetic, biomedical, behavioral, and social factors are crucial to maintaining health and functional capacities in the later years?”42

Despite this paradigm shift, the number of older adults with acute and chronic diseases continues to increase.63 Visual impairments, cataracts, glaucoma, and hearing impairments increase in frequency with advancing age. Almost half of people age 65 and older have arthritis.65 Most older adults have at least one chronic condition, and many have several chronic conditions. In 1994 the chronic conditions that occurred most often in older adults were arthritis, hypertension, heart disease, hearing impairment, cataract, orthopedic impairment, sinusitis, and diabetes (Table 39-1).1 Although heart disease remains the leading cause of death among older adults, cancer may become the leader during the twenty-first century. Currently, among older adults, approximately 7 in 10 deaths are caused by heart disease, cancer, or stroke.63

TABLE 39-1 Percentage of Chronic Conditions in Older Adults

| Conditions | Percentage |

|---|---|

| Arthritis | 50 |

| Hypertension | 36 |

| Heart disease | 32 |

| Hearing impairments | 29 |

| Cataracts | 17 |

| Orthopedic impairments | 16 |

| Sinusitis | 15 |

| Diabetes | 10 |

Data from Administration on Aging: A profile of older Americans, 1998, http://www.aoa.dhhs.gov.

In the early 1900s, Dr. Ignatz Leo was the first to recognize that older adults had health needs and concerns that set them apart from younger adults.47 Not until the later half of the twentieth century, however, did geriatrics (medicine for older adults) become a discipline in health care. A “geriatric” patient is an older adult who is frail, dependent, or both and who requires health and social support services to attain an optimal level of physical, psychologic, and social functioning. Thus the treatment plan must reflect the professional knowledge to resolve physical and psychologic aspects of health status, as well as being sensitive to an individual’s all-encompassing social functioning. This functioning may include aspects of race, ethnicity, culture, personal relationships, esthetics, and social and economic conditions.

The main focus of geriatrics is frail and functionally dependent older adults. Functionally independent older adults are included but only to make them aware of services that they may need if they experience functional deficits that impair their daily activities (Table 39-2). Specialists in geriatric medicine, geriatricians, have additional training in health care for frail and functionally dependent older adults. In geriatric medicine, numerous assessment instruments have been developed to assist the geriatrician, and some aspects of these are important to dentists in identifying risks and functional declines. These instruments include activities of daily living (ADLs), Tinetti Balance and Gait Evaluation, geriatric depression scale (GDS), and Mini-Mental State Questionnaire. Each assesses risks to morbidity and mortality in maintaining a patient’s optimal health and functional independence.

Care for geriatric patients crosses many disciplines. Thus, an interdisciplinary team is formed to care for and treat geriatric patients and may include the dentist. Including dentistry in the interdisciplinary effort has benefits for the patient; for example, oral care has been incorporated into nursing educational programs and practice for the geriatrician nurse practitioner.49 Likewise, dieticians have educational content in oral care. The focus is to include oral health as part of medical nutrition therapy (MNT) in achieving the patient’s total health needs.7 A “last frontier” for the interdisciplinary team is the community. When geriatric patients require multidisciplinary strategies to improve their conditions at the community level, efforts have been less than satisfactory. Problems have been encountered when coordination is needed for geriatric patients to access multiple providers across a range of health care settings. Shared decision making and patient education are needed to improve access and realize successful outcomes.33 A detailed computer-based model on multidisciplinary and interdisciplinary decision making in the geriatric population can be found in Bauer et al.13-19

Functional Status

In dentistry, prevention of oral diseases and improvements in healthy lifestyles have contributed to older adults keeping and maintaining their dentition. Dentistry for geriatric patients, or geriatric dentistry, emphasizes an interdisciplinary approach to diagnosis, treatment, and prevention of dental and oral diseases.31 Specialists in geriatric dentistry are geriatric dentists. Similar geriatric health and functional instruments used in medicine assist geriatric dentists in assessing risks that compromise oral health.

Functional impairments have a significant impact on oral health and self-care. Sensory impairments and arthritis make it more difficult for older adults to understand dental outcomes, communicate oral health care needs and concerns, and perform effective oral self-care. Functional testing or measuring instruments may become part of the dentist’s armamentarium to assess an older adult’s ability to perform oral care tasks in achieving and maintaining oral health. The index of activities of daily oral hygiene (ADOH) is one such dental assessment instrument that quantifies the functional ability of older adults, specifically frail and functionally dependent older adults, in performing oral self-care tasks.10 The index of ADOH provides the dentist or dental assistant with the means to determine the functional ability of an older adult to manipulate aids used in daily oral hygiene care. From these findings, strategies may be developed to rehabilitate and then remeasure for improvements in functional deficits. If improvements are not forthcoming, alternative strategies and assistive devices are recommended.

Accommodating dentists in the interdisciplinary team is increasing, including their participation in primary care. For example, edentulism and denture wearing in older adults may be related to poor quality of life and risk for undiagnosed oral disease. They may also indicate other medical comorbidities. Thus medical and dental geriatricians must incorporate knowledge of comorbidities to identify risks that manifest as reciprocation of disease and poor quality of life.68,73 In managing periodontal disease, the dental geriatrician is challenged with integrating primary care, oral health, and patient and caregiver education in nontraditional settings such as residential, institutional, and hospital practice settings.

Although geriatric medicine training programs have grown remarkably over the past three decades, this growth is still not producing the number of geriatricians needed to care for the growing older adult population. Comparatively, the training of dental geriatricians is much less. In response, the geriatric dentistry community has advocated the use of dental geriatricians to train general dentists in the care of geriatric dental patients. Kayak and Brudvik40 see this type of training essential to “successful aging” and periodontal health care in both dental practice and nontraditional settings. Thus dental geriatricians as faculty are needed to train practitioners.68

In an article on periodontal dental education, Wilder et al stated “that dental schools are confident about the knowledge of their students regarding oral-systemic content. However, much work is needed to educate dental students to work in a collaborative fashion with other health care providers to co-manage patients at risk for oral-systemic conditions.”75

Nutritional Status

Whereas “diet” refers to the consumption of types and varieties of food resources, nutrition is the process by which food is used to provide energy and sustain, restore, and maintain tissue of living organisms. With aging, there is an increased risk of nutritional deficiencies among older adults. However, the real risk is not malnutrition; among older adults in the US, the rate of malnutrition is low. The real risk is attributed to unbalanced diets.

An older adult’s dietary patterns may be associated with numerous factors, including the aging process, diseases and the medications used in their treatment, and social and economic conditions. In general, energy needs and intake in older adults decline with age.

Beyond middle age, body weight and lean body mass decline with age, in part because of primary aging. Age changes in physiologic functioning, including metabolic, hormonal, and neural changes, have been associated with poor quality diets in older adults.

Older adults do not compensate well, or take in more food, when bodily changes alter their energy levels. For example, a slower metabolic rate accompanied with decreased levels of physical activity explains why older adults have reduced food intake. This is also associated with altered sensations of hunger, thirst, and satiety or fullness. Reductions are seen in fluid intake, uncompensated by increased thirst. The variety of foods eaten is reduced, or characteristic bland diets may result from lowered sensory-specific satiety. In other words, older adults have a lowered enjoyment of foods because of deficits in smell and possibly taste. More than half of people age 65 to 80 have a major olfactory impairment, with 75% of those age 80 and older affected. Thus food recognition diminishes with age.

All these factors may place the older adult at risk for serious problems. Anorexia, or low food intake, increases the risk of nutrition-related illnesses. Electrolytic imbalances (e.g., salt and water imbalances) are associated with age-related changes in regulatory systems, such as changes in central nervous system (CNS) receptors that detect changes in the level of sodium in blood. Dehydration, which can lead to illness and death, is a common cause of fluid and electrolyte disturbance. Deconditioning is an almost complete disturbance of physical functioning. These conditions may present when a frail older adult comes to the dental office seeking care and are seen more often in homebound persons, hospitalized patients, and nursing home residents.

Poor nutrition and low body weight may often precede and predispose older adults to secondary age changes. Secondary aging changes are a result of acute and chronic disease and medication use. The most common age-associated chronic diseases are hypertension, hyperlipidemia, atherosclerosis, and diabetes. Compounding effects of secondary aging may include impaired mobility, inability to feed oneself, poor oral health, and the use of dentures, all of which may affect the amount and types of foods consumed. Age-associated decreases in saliva production and swallowing problems may also make eating difficult. In addition, nutrient malabsorption can be caused by altered gastric acid secretion or by interaction with medications. The cumulative effect of these changes may account for taste loss in the older adult.

Economic and social factors have also been linked with significant changes in eating patterns, such as loss of appetite. Economic factors include a lower economic status resulting from retirement, failing health, living on a fixed income, or death of a spouse. Social factors include isolation, loneliness, and the effects of depression or dementia. All these factors may affect the type and quality of food consumed. For example, socialization at meals may increase the amount of food consumed by older adults.

In addition, impaired chewing can cause changes in food selection, such as decreasing the variety in the diet, which may contribute to nutritional problems. Currently, 42% of older adults have no natural teeth. Rehabilitation with complete dentures may restore only 25% of normal chewing effectiveness.54 Of those with teeth, 60% have tooth decay and 90% have periodontal disease, which may contribute to impaired chewing ability or loss of appetite.

These aging-related disease states and social factors may result in inadequate consumption of nutrient-dense foods or inadequate intake of some vitamins and minerals. Minerals are important to the absorption and utilization of vitamins. Both are important to antibody formation and the immune system in combating infection, foreign substances, and toxins (Table 39-3).23

Psychosocial Factors

Dental diseases have their greatest effect on behaviors and mental and social well-being. In other words, dental diseases impact psychologic and social functioning and thus are almost always preventable by behavioral and social means. On average, older adults use fewer dental services, perhaps because of conflicting economic priorities between medical and dental needs. For many older adults, dental services are a discretionary choice and not part of their primary care options. This may result in part from their poorer health status, lack of dental insurance or coverage by government-sponsored health care programs, or simply their functional status or independence.

Older adults with positive attitudes toward oral health have predictably better dental behaviors that translate into higher utilization rates of dental services. Positive attitudes are highly associated with educational level.12 The education level of older adults is increasing. In 1995, only 64% of noninstitutionalized older adults completed at least high school, and 13% possessed a bachelor’s degree. By 2015, it is estimated that 76% of older adults will have completed at least high school, with 20% obtaining a bachelor’s degree. Those with more education were three to four times more likely to have visited a dentist in the past year, indicating that an informed and knowledgeable public provides a culture of healthy behaviors that guide older adults toward the long-term preservation of teeth and function.

Impediments to the utilization of dental services are associated with low income and an associated lack of a regular source of care. Those with higher education tend to be better off financially than those with low education. Poverty is less prevalent today among older adults for all race, gender, and ethnic groups.63,64 In general, older adults have the highest disposable income of all ages.71 Thus higher educational achievement with lower poverty levels is a predictor for an increase in demand for oral health care among older adults.39

However, differences in the prevalence of periodontal disease were seen in relation to race. Among dentate non-Hispanic blacks, non-Hispanic whites, and Mexican Americans 50 years of age and older, blacks had higher levels of periodontal disease, even those in higher income groups. Thus Borrell et al22 suggested that race and ethnicity are important factors in combating health disparities.

Reciprocally, oral disease may affect behaviors, and behavioral problems may adversely affect oral health. Adverse oral health conditions affect three aspects of daily living: (1) systemic health, (2) quality of life, and (3) economic productivity.

Both systemic health and quality of life are compromised when edentulism, xerostomia, soft tissue lesions, and poorly fitting dentures affect eating and food choices. Conditions, such as oral clefts, missing teeth, severe malocclusion, and severe caries, are associated with feelings of embarrassment, withdrawal, and anxiety. Oral and facial pain from dentures, temporomandibular joint disorders, and oral infections affect social interaction and daily behaviors.38

Behavioral problems may worsen oral conditions. Older adults today grew up during Prohibition or the Great Depression, when alcohol consumption was much lower. Since then, alcohol consumption has increased, especially in women, along with alcohol-related health problems. Alcohol-related disorders include alcohol abuse and dependence and alcoholic liver disease, psychoses, cardiomyopathy, gastritis, and polyneuropathy.

A general consensus states that light drinking, or one drink per day, is not harmful as long as the older adult is reasonably healthy and not taking medications that interact with alcohol. However, alcohol may react differently in older than younger adults. A decrease in body water content may produce higher peak serum ethanol levels. In particular, alcohol intake may make older adults vulnerable to changes in the capacity of the liver to metabolize drugs and to symptomatic behaviors such as confusion, depression, and dementia.

The patterns of drinking and alcohol-related problems may not differ between older and younger problem drinkers. However, numerous reports suggest that alcohol as the primary substance of abuse is higher in the older than in the younger adult. A peak onset for alcohol-related problems is 65 to 74 years. Unfortunately, alcohol consumption is directly correlated with clinical attachment loss in periodontal disease.61

Periodontal disease may also be exacerbated in those with depression.4,41 Depression is a common public health problem among elderly persons, affecting 15% of adults over age 65 in the US. The suicide rate for those over 85 is about 2 times the national rate. Geriatric depression is treatable, so recognition of this disorder is a vital step in the prevention of disability and mortality.56 However, depression is not easy to recognize. Depression may also accompany a wide variety of physical illnesses such as fatigue, poor appetite, sleep disturbances, cardiovascular disease, and cancer. It may be the primary cause of somatic complaints, including oral discomfort. The classic signs and symptoms for depression include sadness, decreased appetite, weight loss, confusion, difficulty in decision making, dissatisfaction, and irritability. Many older adults, however, present with a less dramatic level of actual sadness and frequently have apparent cognitive impairment, especially memory deficits, and therefore differentiation from dementia is important. Recognizing the signs of depression can significantly reduce depression, by about 70%, in those over 65 years of age.

Dentate Status

In dentistry the level of illness is measured as “tooth mortality” or tooth loss. Still among the most ubiquitous of human diseases, dental disease places all segments of the population at risk. Older adults are at greatest risk, especially those over 85 years of age. Oral health changes in health and functional well-being (functional disabilities) potentiate risks to oral disease, including dental caries (particularly root caries), periodontal disease, oral cancer, xerostomia (dry mouth), disorders associated with denture wearers, and systemic disease with oral symptoms.

Over a 30-year period, edentulism and partial tooth loss declined substantially.27 The most current estimates of tooth loss and tooth retention in the US population indicate that 75% of older adults age 65 to 69 and over half of adults age 75 and older are dentate (Table 39-4).

By the year 2030, the number of teeth retained by older adults is expected to double, which is an estimated 800 million increase in tooth retention. It is expected that over the next 3 decades the average number of retained teeth will increase from the current 20 to 25.9 teeth.30 Thus the risk of periodontal disease and dental caries is expected to be a major problem of older adults. Because few older adults are covered by dental insurance,11 payment for treatments will be the responsibility of the geriatric patient. Costs and the inability to afford care will always affect health care utilization, particularly dentistry, which is often considered discretionary.

Periodontal Status

The classic periodontal disease model suggested that virtually all older adults would, at some time in their life, become susceptible to severe periodontitis. This result was attributed to an insidious process in which gingivitis slowly progressed into periodontitis, with probable bone and tooth loss. Thus it was asserted that susceptibility to periodontitis increased with age, resulting in tooth loss seen predominantly after age 35 years.

The current periodontal disease model suggests that only a small proportion of adults have advanced periodontal destruction. Mild gingivitis is common, as is mild-to-moderate periodontitis. Most adults show some loss of probing attachment while maintaining a functional dentition. In addition, severe periodontal disease is not a part of normal aging and is not the major cause of tooth loss. There may be exceptions to this, but when disease occurs, it is usually in those age 85 and older.

The model asserts that gingivitis does precede periodontitis, but relatively few sites with gingivitis develop periodontitis. The bacterial flora associated with gingivitis and periodontitis shows similarities but does not reciprocate causally. In all, the current model of periodontal disease indicates the following:

The current risk factors suggested for periodontal disease include age, smoking, diabetes mellitus, and the presence of subgingival Porphyromonas gingivalis and Tannerella forsythia.

The prevalence of periodontal disease is therefore expected to increase with age 20 as a result of a cumulative disease progression over time, not susceptibility.5,44 In a 30-year preventive home care study, periodontal findings showed a 75% improvement in the number of healthy periodontal sites in the 51- to 65-year-old age group.5 Thus recent data suggest that older adults who maintain optimum oral self-care are less susceptible to periodontitis.25

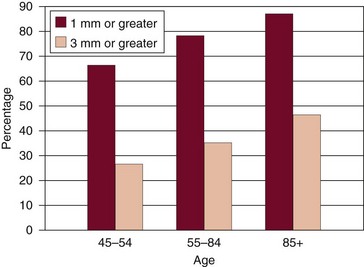

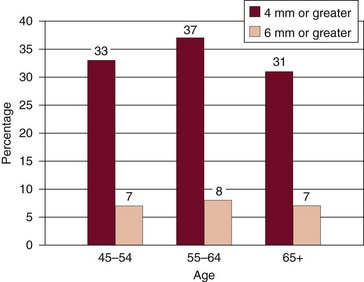

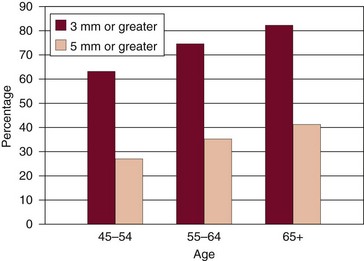

Advanced periodontal disease among older adults is not as common as once thought.15 Moderate levels of attachment loss are seen in a high proportion of older adults, but severe loss is detected in only a small proportion of older adults (Figure 39-2). The amount of periodontal disease associated with age does not appear to be clinically significant, and it is unclear whether the higher prevalence of periodontal disease is a function of age or time.44 Figures 39-3 to 39-5 illustrate periodontal disease data from phase I of the third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES III) conducted in the US from 1988 to 1991.14 Gingival recession increased with advancing age, with one-third (35%) of persons age 55 to 84 and less than half (46%) of persons age 85 and older having 3 mm or more of gingival recession (Figure 39-3). Pocket depth of 6 mm or greater was detected in 7% of persons 45 to 54 years of age, 8% of persons age 55 to 64, and 7% of persons age 65 and older (Figure 39-4). Attachment loss increases with age, although less than half of persons age 65 and older had loss of attachment measuring 5 mm or greater (Figure 39-5).

Figure 39-3 Percentage of older persons with gingival recession, 1988 to 1991.

(From Brown LJ, Brunelle JA, Kingman A: J Dent Res 75:672, 1996.)

Figure 39-4 Percentage of older persons with pocket depths by age, 1988 to 1991.

(From Brown LJ, Brunelle JA, Kingman A: J Dent Res 75:672, 1996.)

Figure 39-5 Percentage of older persons with loss of attachment by age, 1988 to 1991.

(From Brown LJ, Brunelle JA, Kingman A: J Dent Res 75:672, 1996.)

Periodontal regenerative therapies for aging periodontal tissue is being investigated by Benatti and others. Deciphering the biologic properties of periodontal ligament cell (PDLC) regeneration with the use of aging periodontal ligament cells in the laboratory will likely change the way periodontal disease is treated.21

Caries Status

Root caries is a disease that has a particular predilection for older adults. Exposed root surfaces in combination with compromised health status and use of multiple medications make older adults at high risk for root caries. Caries examinations from phase I of NHANES III indicate that root caries prevalence increases greatly with age. Decayed or filled root surfaces were detected in 47% of persons age 65 to 74 and in 55.9% of those 75 and older.78

The majority of older adults are at low risk for developing root caries, but mediating factors increase this risk, including immune system dysfunction and ineffective oral self-care. With the prospect of older adults retaining more of their teeth through improved access, prevention programs, and personal oral hygiene, it is likely that a sound root surface will remain caries free. Once a lesion is present, however, one-surface and multiple-surface lesions progress aggressively to infect other adjoining tooth surfaces rather than cavitating the infected surface. This natural occurrence in older adults is caused by dentinal sclerosis; caries progression spreads without cavitation. In older adults the active four-surface lesion produces a characteristic “apple coring,” or collar of caries extending circumferentially along the cementoenamel junction, below the clinical enamel crown of the tooth. The four-surface lesion becomes chronic, with morphologic loss dependent on the balance of forces during demineralization and remineralization. Loss of the root structure may be so significant that it undermines the support of the clinical crown. When tooth structure is compromised, the tooth is at a high risk for fracture, and oral or tooth function is impaired (Figure 39-6). The tooth may then be lost because of clinical outcomes that disallow its rehabilitation.

Dental Visits

Fundamentally, dental visits by older adults are correlated with having teeth, not age.77 Data from the 1995 Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System (BRFSS), which is a continuous state-based, random-digit-dialed telephone survey of the US noninstitutionalized population age 18 years and older, indicate that older adults are frequent users of dental services.26

Although their total consumption of dental services approximates that of younger adults, older adults make fewer dental visits: 21% to 53% of dentate adults visited the dentist in the last 12 months. Approximately 40% of these older adults utilize these visits for episodic care, indicating a lack of sustained and consistent care. Those least likely to visit a dentist were older adults who were either homebound or institutionalized.

When dentate and edentulous adults express positive attitudes regarding the efficacy of dental care, their care-seeking behaviors translate into use, continuous use, and recent use of dental services. However, the belief among dentate and edentulous older adults that their dental problems are a result of aging prevails. Despite clinically evident disease or problems, beliefs and values of older adults regarding the usefulness of dental care to resolve oral problems are limited. They have difficulty incorporating their perceived need into care-seeking behaviors. In addition, nursing home residents often refuse dental care, even when cost is not a barrier, and believe prevention or treatment would not be efficacious in solving their oral problems.

Recent studies report dramatic increases in dentate older adults accessing dental care, with older adults now using dental services to the same extent as dentate adults between ages 35 and 44. Among adults age 65 and older, 62% of all respondents reported having a dental visit during the previous year, and 75% of those with natural teeth reported a dental visit in the past year.26

As the trend for tooth retention in older adults continues, older adults will account for a greater proportion of dental practice income and visits. Even the oldest persons in the elderly population have reversed earlier, negative attitudes and demonstrated increased awareness and concern for oral health.41,43,74 Dental expenditure data indicate that older adults have a higher cost per visit than younger persons and are willing to make a significant investment in dental care.71 Despite these trends, older adults in nursing homes seldom access dental services.

Xerostomia

Saliva plays an essential role in maintaining oral health. Besides a loss of acinar cells occurring with aging, many older adults take medications for chronic medical conditions and disorders. When challenged with medications that cause dry mouth, older adults are more adversely affected than younger adults, which supports the secretory reserve hypothesis of salivary function.25,36

More than 500 prescription and over-the-counter (OTC) medications are associated with decreased saliva, dry mouth, and xerostomia. The medications most often associated with xerostomia and decreased saliva are the tricyclic antidepressants, antihistamines, antihypertensives, and diuretics. Medication use is frequently associated with dry mouth; however, certain medical diseases, disorders, or conditions are also associated with dry mouth, such as radiation treatment for oral, head, neck, and thyroid cancers; Sjögren’s syndrome; poorly controlled diabetes; bone marrow transplantation; thyroid disorders; and depression (Figure 39-7).

Symptomatic and corrective therapies, such as parotid-sparing radiation therapy, have been suggested. The effect of this treatment has been shown to reduce xerostomia in each of four domains of quality of life: eating, communication, pain, and emotion. Both xerostomia and quality-of-life scores improved significantly over time during the first year after therapy. These results suggest that the efforts to reduce xerostomia using parotid-sparing radiation therapy may improve broad aspects of quality of life.43

Medications that induce xerostomia may also be associated with compromised chewing, speaking, tasting, or swallowing and increased risk for caries, periodontal disease, and candidiasis.

Future research directions include (1) gene therapy approaches to direct salivary growth and differentiation or modify remaining tissues to promote secretion, (2) creation of a biocompatible artificial salivary gland, and (3) salivary transplantation. With improved secretagogues, the effects of conditions that result in reduced salivary function and increased caries will be ameliorated.34

Candidiasis

Candidiasis is caused by an overproliferation of Candida albicans. A pathogenic infection occurs when C. albicans infiltrates into the oral mucosal layers. Candidiasis can be both local and systemic.37

Any condition compromising a patient’s immune system can be considered a risk factor for candidiasis. Oral candidiasis can occur with long-term use of antibiotics, steroid therapies, or chemotherapy. Diabetes mellitus, head and neck radiation therapy, and human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) are risk factors for acute pseudomembranous candidal infection. Pseudomembranous candidiasis presents as white lesions that can be wiped away with gauze, leaving an erythematous area.37

Chronic atrophic candidiasis presents most often as an erythematous area under a maxillary denture and is associated with poor oral hygiene. In patients without a prosthesis, chronic atrophic candidiasis may present as a generalized redness or even generalized burning of the mouth.37

Chronic atrophic candidiasis, or angular cheilitis, can also manifest itself in the creases or commissures of the lips. This occurs when a patient has a tendency to pool saliva around the corners of the mouth or constantly lick the lips in some cases.37

A new treatment for candidiasis is being investigated using bioadhesive nanoparticles as modulators of adherence to buccal epithelial cells.48

Dental and Medical Assessments

Initially, the patient interview assists the patient in disclosing needs, desires, preferences, and values for dental treatment. The dental history includes dates of the last dental examination and visit, radiographs taken, and the frequency of tooth prophylaxis. Also included is a review of past restorations, endodontic therapies, extractions, oral surgeries, prosthetic appliances (including single and multiple, removable and fixed units), periodontal therapies, and gnathologic treatments. Other useful information may include daily oral self-care regimens, fluoride status of the drinking water (bottled, well, and community sources), and type of toothpaste used (fluoride versus nonfluoride).

The medical history of the older adult should be detailed and should include a careful review of past and current medical and mental conditions, including emergency and hospital visits and any serious illnesses (Box 39-1). The review should focus on a careful evaluation of systemic diseases and disorders, particularly those that influence dental treatment, such as bleeding disorders and use of anticoagulants,29 diabetes, heart valve problems,1,45 certain cardiovascular conditions, stroke, artificial joints,5 and use of corticosteroids. A consultation with the patient’s physician is advisable, especially for older adults with medical problems, or if complicated or invasive procedures are planned. The medical history review should also include medications taken regularly and allergies to medications, metals, and environmental allergens. The social history is reviewed to determine the patient’s age, tobacco use (type and pack-years estimate), alcohol use, and caregiver status. Caregiver status indicates the functional level of the patient as functionally independent, frail, or functionally dependent.

BOX 39-1 Dental Patient Interview: Older Adult

Obtaining a complete medical history may take longer in severely compromised older adults. However, the time spent to disclose conditions will determine if the use of the interdisciplinary team is indicated. Coordinating and managing oral health care in this manner may increase the success of dental outcomes.58

Older adults are high users of prescription and OTC medications. Table 39-5 lists the top 20 drugs prescribed in the US in 2003. Many medications used by older adults can have a negative impact on oral health. To obtain a complete list of prescription and OTC medications, ask patients to bring each medication bottle or package to the dental office. This not only helps to obtain a complete medication list but also provides additional information such as medication dose and number of physicians prescribing medications.

TABLE 39-5 Top 20 Drugs Prescribed in the United States, 2003

| Brand Name | Drug Action | Manufacturer |

|---|---|---|

| Hydrocodone w/APAP | Opioid analgesic, antitussive, antipyretic | Various; data for two or more generic manufacturers have been combined. |

| Lipitor | Lipid-lowering agent used for treating cholesterolemia | Pfizer US Pharmaceuticals |

| Synthroid | Synthetic human thyroid used for treating hypothyroidism | Abbott |

| Atenolol | Synthetic, β1-selective (cardioselective) adrenoreceptor blocking agent | Various; data for two or more generic manufacturers have been combined. |

| Zithromax | Antibiotic similar to erythromycin | Pfizer US Pharmaceuticals |

| Amoxicillin | Antibiotic-antibacterial drug | Various; data for two or more generic manufacturers have been combined. |

| Furosemide | Potent diuretic contained in Lasix | Various; data for two or more generic manufacturers have been combined. |

| Hydrochlorothiazide | Diuretic Antihypertensive |

Various; data for two or more generic manufacturers have been combined. |

| Norvasc | Long-acting calcium channel blocker | Pfizer US Pharmaceuticals |

| Lisinopril | Synthetic peptide derivative used as an oral long-acting angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitor | Various; data for two or more generic manufacturers have been combined. |

| Alprazolam | One of the benzodiazepine class of central nervous system–active compounds used for treating anxiety and contained in Xanax | Various; data for two or more generic manufacturers have been combined. |

| Zoloft | Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI) used for treating depression | Pfizer US Pharmaceuticals |

| Albuterol Aerosol | Inhalation aerosol used for treating asthma and contained in Proventil | Various; data for two or more generic manufacturers have been combined. |

| Toprol-XL | Synthetic, β1-selective (cardioselective) adrenoreceptor blocking agent | AstraZeneca |

| Zocor | Lipid-lowering agent used for treating cholesterolemia | MSD |

| Premarin | Estrogen used for treating menopause: hormone replacement therapy (HRT) | Wyeth Pharmaceuticals |

| Prevacid | Inhibits gastric acid secretion | Tap Pharmaceuticals |

| Zyrtec | Selective H1-receptor antagonist used for treating allergies | Pfizer US Pharmaceuticals |

| Ibuprofen | Nonsteroidal antiinflammatory agent Analgesic Both contained in Motrin |

Various; data for two or more generic manufacturers have been combined. |

| Levoxyl | Synthetic human thyroid used for treating hypothyroidism | Monarch Pharmaceuticals |

Data from RxList: Top 200 prescriptions for 2003 by number of U.S. prescriptions dispensed, http://www.rxlist.com/top200.htm. Feb. 21, 2005.

Extraoral and Intraoral Examinations

The extraoral examination provides assessments of the head and neck. The head and neck examination determines if the skull is normal in shape with no traumatic injuries. Also included are assessments of the skin, nodes, and cranial nerves involved in oral function. The temporomandibular joint is also assessed at this time. Findings include changes from normal, apparent lesions, and dysfunction.

The intraoral examination provides assessment of soft and hard tissue of the oral cavity (Box 39-2). Assessments help to determine the state of the teeth: past restorations, caries, occlusal dysfunction, and missing teeth. The periodontal examination includes gingival bleeding points and pocket depths. The remaining intraoral examination assesses the lips, cheeks, tongue, gingiva, floor of the mouth, palate, retromolar region, and oropharyngeal area for tissue abnormalities, red or white patches, ulcerations, and swellings. A major focus of these examinations is the assessment for oral and pharyngeal cancer.

BOX 39-2 Dental Examination: Assessments for Older Adult Patients

Oral Epithelium

It can be difficult to differentiate between a benign lesion and either a precancerous or early cancerous lesion. For this reason, a product called OralCDx has been developed; this computer-assisted brush biopsy test can aid in screening for cancer.28,55

Oral cancer may appear as an ulceration, a swelling, or a red or white sore that does not heal in 1 to 2 weeks. Other signs of oral cancer may be swollen lymph nodes and difficulty swallowing and speaking.32 Particularly alarming, oral and pharyngeal cancer lesions may not be painful. Unfortunately, the 5-year survival of patients with oral cancer has not improved.6

Xerostomia screening may be done by sialometry or by oral examination. With sialometry, depending on the type of gland, the precise collection of saliva may require 5 to 15 minutes (Table 39-6). Specific screening tools may be required for different gland types. For example, modified Carlson-Crittenden collectors are used to suction saliva from the parotid gland through Stensen’s duct, and specialized equipment is used for the submandibular gland (through Wharton’s ducts) and the minor salivary glands.

TABLE 39-6 Sialometry for Xerostomia Screening: Salivary Flow Rates

| Category | Normal | Abnormal |

|---|---|---|

| Whole saliva | 0.5–1.2 ml/min | 0.0–0.2 ml/min |

| Whole saliva, stimulated | 1.0–2.0 ml/min | 0.01–0.4 ml/min |

A less quantitative measure of saliva for xerostomia is by oral examination using a tongue blade (Figure 39-8). The saliva collected from either the floor of the mouth or the buccal vestibules is absorbed onto the tongue blade (see Figure 39-8, A and B). If only the tip of the tongue blade demonstrates wetness rather than a greater portion of the end of the blade, then an abnormal finding is noted (see Figure 39-8, C).

Figure 39-8 Tongue blade screen for saliva testing. A, Screening begins by placing the tongue blade in the sublingual area at the mandibular anterior quadrant. B, For the saliva screen, wet the tongue blade for about 5 seconds. C, Tongue blade screen showing minimal wetness, an indication of xerostomia.

Assessment of risk is determined after completion of the patient interview and the extraoral and intraoral examinations. Oral and medical problems may influence the risk for disease, pain, oral dysfunction, and nutritional disorders, both in quality and quantity of foods.53 Risk assessments may also serve as predictors for successful treatment outcomes, maintenance protocols, and patient compliance. For example, the risk factors that influence periodontal therapy are smoking, genetic susceptibility, compliance, and diabetes.76

Assessment tests use genetic markers to demonstrate susceptibility to periodontal disease. Specific genetic markers associated with increased levels of interleukin-1 (IL-1) production indicate a strong susceptibility to severe periodontitis in older adults. When the genotype for polymorphic IL-1 gene cluster was identified, it was correlated with an odds ratio of 18.9, indicating severe periodontitis in nonsmoking adults.

Risk factors for oral and pharyngeal cancer are age, tobacco use, frequent use of alcohol, and exposure to sunlight (lip). Oral cancer is treatable if discovered and treated early. Most dentists can easily identify an early carcinoma in situ (Figure 39-9). At this stage, however, the lesion may have already spread to the lymph nodes. Oral and pharyngeal cancer detected at later stages can cause disfigurement, loss of function, decreased quality of life, and death. Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) data indicated that more than 50% of tongue and floor of mouth cancers had metastasized to a distant site at the time of diagnosis.57

The conditions predisposing the older patient to disease or changes in oral health status may result from physical or psychologic problems, or both. These problems may be the result of the older person’s social conditions. Whatever the cause, these underlying problems must be addressed so that dental outcomes will be positive. This may require the dentist first to address the patient’s fears and expectations about treatment outcomes. For example, older adults who are experiencing the loss of teeth and the adjustment to removable appliances or dentures can experience tremendous difficulty in accepting a reduced level of oral functioning. Their coping mechanism may also be stressed because of other socially important factors, such as esthetics and social esteem. Thus the patient’s presenting conditions may affect the rendering of the treatment plan.

Many conditions limit an older person’s ability to withstand or cope with dental treatment. For example, some older adults with physically or psychologically based behavior problems may require premedication in order for the dentist to deliver treatment. Other conditions may limit the dentist’s ability to render treatment. For example, an older patient may not tolerate a reclining chair position for restorative procedures because of a chronic heart ailment or arthritis.

With treatment, there is a concomitant risk for causing problems, referred to as iatrogenic effects. Iatrogenic problems arise from side effects of treatment or from treatment procedures and range from drug interactions to medical emergencies.

Under certain conditions, the most appropriate care is to do nothing. In some severely compromised patients, treatment is only rendered if the potential for sepsis is suspected. Otherwise, treatment is withheld. In less serious situations, a dentist may decide not to treat a cracked tooth but to dome it and leave its root intact in tissue. This maintains the bone in the area and allows for a prosthetic appliance to be placed. In general, the dentist uses a determination of the risk/benefit of treatment for patient-related outcomes in deciding whether to provide treatment.

In addition, the dentist often may not have the special skills, equipment, or training to meet the needs of poorly functioning or nonfunctioning older adults. This may require the dentist to obtain the additional training and equipment to treat this population, especially in a rural community where access to services is extremely limited. Alternatively, the dentist may need to become familiar with the referral resources to contact clinicians who can treat such patients. One major referral base would be a trained hospital dentist who is capable of managing and treating the patient impaired by dementia or some physical problem or disease.

Periodontal Diseases in Older Adults

Periodontal disease in older adults is usually referred to as chronic periodontitis.37,60 Because periodontitis is a chronic disease, much of the ravages of the disease detected in older adults results from an accumulation of the disease over time. Research has shown that the advanced stages of periodontitis are less prevalent than the moderate stages in the older adult population.24 One theory is that many sites of advanced periodontal disease have resulted in tooth loss earlier in life, suggesting that older age is not a risk factor for periodontal disease.37,60

Evidence is limited on whether the risk factors for periodontal disease differ with age.20 General health status, immune status, diabetes, nutrition, smoking, genetics, medications, mental health status, salivary flow, functional deficits, and finances may modify the relationship between periodontal disease and age.20,76

Some frequently prescribed medications for older adults can alter the gingival tissues. Steroid-induced gingivitis has been associated with postmenopausal women receiving steroid therapy. Gingival overgrowth can be induced by such medications as cyclosporines, calcium channel blockers, and anticonvulsants (e.g., nifedipine, phenytoin) in the presence of poor oral hygiene. This gingival overgrowth further decreases a person’s ability to maintain good oral hygiene.37

Relationship to Systemic Disease

In Padilha et al,52 using data from the Baltimore Longitudinal Study of Aging, the conclusion is reached that “the number of teeth is a significant risk indicator for mortality … and that improving oral health and preventing tooth decay may substantially improve the oral status of the population and increase longevity.”

A review of the literature by Loesche and Lopatin46 indicates that poor oral health has been associated with medical conditions such as aspiration pneumonia and cardiovascular disease. In particular, periodontal disease can be associated with coronary heart disease and cerebrovascular accident (CVA; stroke). In addition, the Surgeon General’s Report on Oral Health emphasizes that animal and population-based studies demonstrate an association between periodontal disease and diabetes, cardiovascular disease, and stroke.66

Recent investigations confirm these associations. For example, a periodontal examination may assist cardiovascular risk assessment in hypertensive patients. Angeli et al8 reported an association between periodontal disease and left ventricular mass in untreated patients with essential hypertension.

Pneumonia is a common cause of morbidity and mortality in the older adult. Improvements in oral care have greatly reduced the incidence of pneumonia in elderly nursing home patients. Although the mechanism is currently under investigation, it is thought that the cough reflex can be improved by reducing the oropharyngeal microbial pathogens present.69 Expanding on these findings, studies have been conducted on the prevention of ventilator-associated pneumonia. Providing oral therapy for intensive care patients to reduce bacterial colonization in the mouth and teeth can reduce mortality and morbidity by 42%.35

The presence and extent of periodontal disease may be related to increased risk of weight loss in older, well-functioning adults. This association is independent of smoking and diabetes mellitus. Changes in nutrient intake may be related to periodontal disease and a higher systemic inflammatory burden.74

Periodontal Treatment Planning

Generally, periodontal disease in older adults is not a rapidly progressive disease but often presents as long-standing chronic disease. Because periodontal disease has periods of exacerbation and remission, understanding and documenting periods of active disease versus quiescent periods are essential to the formulation of the treatment plan and prognosis.60

Periodontal disease must be diagnosed regardless of age. The goal of periodontal treatment for both young and old patients is to preserve function and eliminate or prevent the progression of inflammatory disease.72

The goal of clinically managing periodontal disease in older adults is based on specific, individualized care. The major consideration is improving or maintaining function, with an emphasis on quality-of-life issues. Emphasizing care over cure is the cornerstone of any proposed treatment plan. Prevention, comfort, function, esthetics, and ease of maintenance are the criteria for successful management of an older adult, particularly a frail or functionally dependent older patient.

Several factors must be considered during treatment planning for older individuals.60 It is important first to remember that periodontal healing and recurrence of disease are not influenced by age.20 Factors to consider in the older patient are medical and mental health status, medications, functional status, and lifestyle behaviors that influence periodontal treatment, outcome, or progression of disease.72 Periodontal disease severity, ability to perform oral hygiene procedures, and ability to tolerate treatment should be evaluated during treatment planning. The risks and benefits of both surgical and nonsurgical therapy should be considered.46 The amount of remaining periodontal support or past periodontal destruction, tooth type, number of occlusal contacts, and individual patient preferences are also important.72 Dental implants are a reliable replacement for missing teeth in older adults77; age alone is not a contraindication for implant placement. Risk factors for success of implants has been investigated. While aging is a factor in decision making, the majority of the failures are associated with smoking, diabetes, head and neck radiation, and postmenopausal estrogen therapy.51

For older adults, a nonsurgical approach is often the first treatment choice. Depending on the nature and extent of periodontal disease, surgical therapy may be indicated. Surgical technique should minimize the amount of additional root exposure. Individuals responding best to surgical therapy are those who are able to maintain the surgical result. Age alone is not a contraindication to surgery. For individuals who are unable to comply with treatment, who have poor oral hygiene, or who are medically or mentally compromised or functionally impaired, palliative supportive periodontal care instead of surgical periodontal treatment is often the optimal treatment approach.46,58

A common goal for all older adults is to decrease bacteria through oral hygiene and mechanical debridement. Clinical trials with older adults show that the development or progression of periodontal disease can be prevented or arrested by the control of plaque. For certain patients, topical antibiotic therapy may complement repeated subgingival instrumentation during supportive care. Oral hygiene maintenance should also focus on root surfaces susceptible to caries.72

Decision making for frail and functionally dependent older adults may be challenging to the general dentist. For this reason, dentists, other health care professionals, and other scientists are creating high-quality office-based methods to access evidence-based decision-making programs and accommodating websites to help with complicated oral health care issues. 3,59,70

Prevention of Periodontal Disease and Maintenance of Periodontal Health in Older Adults

For both younger and older persons, the most important factors determining a successful outcome of periodontal treatment are plaque control and frequency of professional care. Advanced age does not decrease plaque control9; however, older adults may have difficulty performing adequate oral hygiene because of compromised health, altered mental status, medications, or altered mobility and dexterity.72 Older adults may change toothbrush habits because of disabilities such as hemiplegia secondary to CVA, visual difficulties, dementia, and arthritis. The newer, lightweight, electric-powered toothbrushes may be more beneficial than a manual toothbrush for older adults with physical and sensory limitations. The proportion of people who floss their teeth decreases after age 40 years.71 This may be partly caused by impairment of fine motor skills secondary to disease or injury. Interproximal brushes, shaped wooden toothpicks, and mechanical flossing devices often can be used in place of traditional flossing with satisfactory outcomes.

In addition, multidisciplinary strategies are increasingly becoming part of periodontal health care promotion. Assessments of overall health, functional status, and patient education are fundamental to promoting and maintaining optimum periodontal health. Older adults, their families, and caregivers need to be informed and trained by dentists in the appropriate devices, chemotherapeutic agents, and techniques to provide oral self-care and maintain healthy lifestyles. The outcomes are instrumental in achieving overall health, oral and periodontal health, self-esteem, nutrition, and quality of life. Barriers to achieving these benefits are access and costs. For those older adults who are homebound or institutionalized, these barriers inhibit their achieving and maintaining optimum oral and periodontal health.

Antiplaque Agents

Patients who are unable to remove plaque adequately secondary to disease or disability may benefit from antiplaque agents such as chlorhexidine, sub-antimicrobial tetracycline, and Listerine or its generic counterparts.50,60,72

Chlorhexidine is a cationic bisbiguanide that has been used as a broad-spectrum antiseptic in medicine since the 1950s. In Europe, a 0.2% concentration of chlorhexidine has been used for years as a preventive and therapeutic agent.46,71 Chlorhexidine is either bacteriostatic or bactericidal, depending on the dose. Adverse effects of chlorhexidine include an increase in calculus formation, dysgeusia (altered taste), and permanent staining of teeth.6 Chlorhexidine is a prescription rinse for short-term use (<6 months); long-term use (>6 months) has not been extensively studied.71 The American Dental Association (ADA) Council on Dental Therapeutics4 has approved chlorhexidine to help prevent and reduce supragingival plaque and gingivitis. Although chlorhexidine has not been studied in older adults, outcomes in younger persons, including those with disabilities, suggest that it is also effective in older adults. Chlorhexidine may be particularly useful for older adults who have difficulty with plaque removal and those who take phenytoin, calcium channel blockers, or cyclosporines and who are at risk for gingival hyperplasia.60,71

Sub-antimicrobial tetracycline (Periostat) is useful in treating moderate to severe chronic periodontitis. The active ingredient in Periostat is doxycycline hyclate. In concert with scaling and root planing, Mohammad et al50 have shown this treatment to be effective in institutionalized older adults. Periostat is contraindicated for those patients with an allergy to tetracycline.

Listerine antiseptic and its generic counterparts are approved by the ADA Council on Dental Therapeutics6 to help prevent and reduce supragingival plaque and gingivitis. The active ingredients in Listerine are methyl salicylate and three essential oils (eucalyptol, thymol, and menthol). Listerine has been shown to be effective in reducing plaque and gingivitis compared with placebo rinses in young healthy adults. Listerine may exacerbate xerostomia because of its high alcohol content, ranging from 21.6% to 26.9%. Listerine is generally contraindicated in patients under treatment for alcoholism who take Antabuse (disulfiram). Listerine may benefit patients who do not tolerate the taste or staining of chlorhexidine and who prefer OTC medicaments that are less expensive and easier to obtain.60,71

The use of inorganic polyphosphate (Poly P) to treat periodontal disease in the aging is being investigated in Japan and points to an alternative method for reduction of bone loss. What is interesting is that the Poly P is considered safe as a food additive and is low risk to harm the patient. Since it is not an antibiotic, bacteria are unlikely to become resistant to it.80

Fluoride

Fluoride, “nature’s cavity fighter,” is the most effective caries-preventive agent currently available. Fluoride’s effects are as follows60,71:

Topical fluorides are recommended for the prevention and treatment of dental caries. OTC fluorides include fluoride dentifrices, rinses, and gels that contain concentrations of 230 to 1500 parts per million (ppm) of fluoride ions. Prescription 1.1% neutral sodium fluoride gels are available with a fluoride concentration of 5000 ppm fluoride ion. Professionally applied fluoride gel, foam, or varnish products are between 9050 and 22,600 ppm fluoride ion.6

Saliva Substitutes

Saliva substitutes, which are intended to match the chemical and physical traits of saliva, are available to relieve the symptoms of dry mouth. Their composition is varied; however, they usually contain salt ions, a flavoring agent, paraben (preservative), cellulose derivative or animal mucins, and fluoride. The ADA’s seal of approval has been granted for some artificial saliva products (e.g., Saliva Substitute, Salivart).6 Most saliva substitutes can be used as desired by patients and are dispensed in spray bottle, rinse/swish bottle, or oral swab stick.6,71 In addition, products, such as dry-mouth toothpastes and moisturizing gels, are also available. Biotene products are marketed to relieve the symptoms of xerostomia.

Patients with dry mouth may also benefit by stimulating saliva flow with sugarless candies and sugarless gum. Xylitol chewing gum has been shown to have anticariogenic properties in children. Medicated chewing gum with xylitol and chlorhexidine or xylitol alone has the added benefits of reducing oral plaque scores and gingivitis in elderly persons who live in residential facilities.7

Salivary substitutes and stimulants are only effective in the short term. Under investigation is acupuncture-like transcutaneous nerve stimulation (Codetron), a method to treat radiation-induced xerostomia. Unlike traditional acupuncture therapy, Codetron does not use invasive needles to achieve stimulation. This method helps the patient to produce their own saliva and reduce symptoms of xerostomia for several months. Acupuncture therapy has demonstrated improvements lasting up to 3 years.79

Cessation of tobacco use has been primarily an issue of patient compliance. Most smokers (90%) quit “cold turkey.” However, nicotine replacement therapy may help strongly addicted patients. The transdermal nicotine patch or nicotine polacrilex (gum) can reduce the symptoms of nicotine withdrawal. For behavioral modification, the four steps to tobacco cessation are as follows:

Clinical studies show that all four components, used routinely, result in much higher patient cessation rates than if only two or three are used. Both forms of nicotine replacement have been shown to increase cessation rates when used in combination with behavioral interventions.

Nicotine replacement therapy is intended to be used for a few (6 to 12) weeks so that patients can learn psychologic and social coping skills without going through nicotine withdrawal at the same time. It is not recommended for use for more than 6 months.

Nicotine replacement therapy should probably not be considered for the following persons:

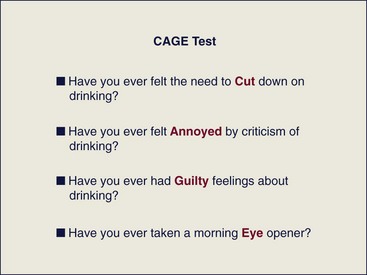

Alcoholism and alcohol abuse are diagnosed using the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, third edition, revised (DSM-IIIR), and fourth edition (DSM-IV). The tests suggested to screen for alcohol abuse are the self-administered questionnaire, the Michigan Alcoholism Screening Test (MAST), and the CAGE (from a series of four questions about drinking: cut down, annoyed, guilty, and eye-opener) questionnaire, which is a four-item screening tool (Figure 39-10). A score of 2 (an affirmative answer to 2 questions) in the elderly patient provides clinical evidence or suspicion of alcohol abuse, with a sensitivity of about 50% and a specificity over 90%. The MAST, with a cutoff score of 5, produces sensitivity ranging from 50% to 70% and a specificity above 90%.

Figure 39-10 Method of determining alcohol abuse using the modified CAGE test. The acronym CAGE is derived from a series of four questions about drinking: cut down; annoyed; guilty; and eye-opener test.

(From Mallin R: Am Fam Physician 65:1107, 2002.)

The most common treatment for alcoholism is referral to a substance abuse facility. For the older adults, the most effective treatment is a program that emphasizes older adult–specific groups using nonconfrontational therapy and encouraging reminiscence, as well as discussion of current problems. Discussion of current problems is relevant because of the role that stress plays in recent widowhood, recent retirement, or disruption or removal from one’s residence.

Conclusion

Future oral health care trends will see increased numbers of older adults seeking periodontal therapy. Dental practitioners of the twenty-first century should be comfortable providing comprehensive periodontal care for this segment of the population. Aging dental patients have particular oral and general health conditions that dentists should be familiar with detecting, consulting, and treating. Medical diseases and conditions that occur more often with age may require modification to periodontal preventive tools, as well as for the planning and treatment phases of periodontal care.

![]() Science Transfer

Science Transfer

With improvements in life expectancy, dentists can expect to be treating more older patients than in previous years. There are also improvements in dental heath so that more of these patients have surviving teeth. Because of these factors, clinicians need to focus on the special needs of older patients. Many of these patients have reduced salivary flow and so are more susceptible to gingival inflammation and root caries and thus need aggressive preventive treatment, including topical fluorides, antiplaque mouthwashes, focused mechanical oral hygiene techniques, and artificial salivary supplements.

Healthy older patients can be successfully treated with all types of periodontal therapy, including surgical approaches, and dental implants can be successful in this group of patients.

1 ACC/AHA 2008 Guideline Update on Valvular Heart Disease: Focused Update on Infective Endocarditis. A Report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. Circulation. 2008;118:887.

2 Administration on Aging. A profile of older Americans. http://www.aoa.dhhs.gov, 1998.

3 Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Evidence-based practice. http://www.ahrq.gov/clinic/epcix.htm, 2005.

4 Alliance for Aging Research, task force on aging research funding. Washington, DC: The Alliance, 2004.

5 American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons. Antibiotic Prophylaxis for Bacteremia in Patients with Joint Replacements. http://www.aaos.org/, 2009.

6 American Dental Association. Guide to dental therapeutics, ed 2. Chicago: ADA; 2000.

7 American Dietetic Association. Oral health and nutrition. J Am Diet Assoc. 2003;103:615.

8 Angeli F, Verdecchia P, Pellegrino C, et al. Association between periodontal disease and left ventricle mass in essential hypertension. Hypertension. 2003;41:488.

9 Axelsson P, Nystrom B, Lindhe J. The long-term effect of a plaque control program on tooth mortality, caries and periodontal disease in adults: results after 30 years of maintenance. J Clin Periodontol. 2004;31:749.

10 Bauer JG. The index of ADOH: concept of measuring oral self-care functioning in the elderly, Spec Care. Dent. 2001;21:63.

11 Bauer JG, Spackman S. Financing Dental Services In The Us: Best practice model, Braz. J Oral Sci. 2003;2:187.

12 Bauer JG, Spackman S, Chiappelli F, et al. Issues In Dentistry For Patients With Alzheimer-Related Dementia. Long-Term Care—Interface. 2005;6:30.

13 Bauer JG, Spackman S. The clinical decision tree of oral health in geriatrics. In: Weiss JW, Weiss DJ, editors. A Science of Decision Making. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2009.

14 Bauer JG, Spackman S, Chiappelli F, et al. Interdisciplinary resources optimize evidence-based dental practice. J Evid-Based Dent Pract. 2005;5:67.

15 Bauer JG, Spackman S, Chiappelli F, et al. Evidence-based decision-making in private practice. J Evid-Based Dent Pract. 2005;5:125.

16 Bauer JG, Spackman S, Chiappelli F, et al. Model of evidence-based dental decision-making. J Evid-Based Dent Pract. 2005;5:189.

17 Bauer J, Chiappelli F, Spackman S, et al. Evidence-based dentistry: Fundamentals for the Dentist. CDA Journal. 2006;34:427.

18 Bauer JG, Spackman S, Chiappelli F, et al. Evidence-based dentistry: A clinician’s perspective. CDA Journal. 2006;34:427.

19 Bauer JG, Spackman S, Chiappelli F, et al. Making clinical decisions using a clinical practice guideline. CDA Journal. 2006;34:427.

20 Beck JD. Periodontal implications: older adults. Ann Periodontol. 1996;1:322.

21 Benatti BB, Silvério KG, Casati MZ, et al. Influence of aging on biological properties of periodontal ligament cells. Connective Tissue Research. 2008;49:401.

22 Borrell LN, Burt BA, Neighbors HW, Taylor GW. Social factors and periodontitis in an older population. Am J Public Health. 2004;94:748.

23 Boyd LD, Madden TE. Nutrition, infection, and periodontal disease. Dent Clin North Am. 2003;47:337.

24 Brown LJ, Brunelle JA, Kingman A. Periodontal status in the United States, 1988–1991: prevalence, extent, and demographic variation. J Dent Res. 1996;75:672. (special issue)

25 Burt BA, Eklund SA. Dentistry, dental practice, and the community. Philadelphia: Saunders; 1999.

26 Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Dental service use and dental insurance coverage—United States, behavioral risk factor surveillance System, 1995. MMWR. 1997;46:1199.

27 Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Public health and aging: retention of natural teeth among older adults—United States, 2002. MMWR. 2003;52:1226.

28 Christian DC. Computer-assisted analysis of oral brush biopsies at an oral cancer screening program. J Am Dent Assoc. 2002;133:357.

29 du Breuil AL, Umland EM. Outpatient management of anticoagulation therapy. Am Fam Physician. 2007;75:1031.

30 Ettinger RL. The unique oral health needs of an aging population. Dent Clin North Am. 1997;41:633.

31 Ettinger RL, Mulligan R. The future of dental care for the elderly population. J Calif Dent Assoc. 1999;27:687.

32 Fedele DJ, Jones JA, Niessen LC. Oral cancer screening in the elderly. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1991;39:920.

33 Fortinsky RH, Iannuzzi-Sucich M, Baker, et al. Fall—risk assessment and management in clinical practice: views from healthcare providers. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2004;52:1522.

34 Fox PC. Salivary enhancement therapies. Caries. 2004;38:241.

35 Garcia R, Jendresky l, Colbert L: Reduction of microbial colonization in the oropharynx and dental plaque reduces ventilator-associated pneumonia. Poster presented at Association for Professionals in Infection Control (APIC) Conference and Epidemiology Annual Educational Conference and International Meeting, Phoenix, 2004.

36 Ghezzi EM, Ship JA. Aging and secretory reserve capacity of major salivary glands. J Dent Res. 2003;82:844.

37 Gibson G, Niessen LC, Cassel CK, Cohen HJ, Larson EB, et al, editors. Geriatric medicine. New York: Springer-Verlag, 1997.

38 Hollister MC, Weintraub JA. The association of oral status with systemic health, quality of life, and economic productivity. J Dent Educ. 1993;57:901.

39 Jones JA, Fedele DJ, Bolden AJ, et al. Gains in dental care use not shared by minority elders. J Public Health Dent. 1994;54:39.

40 Kayak HA, Brudvik J. Dental students’ self-assessed competence in geriatric dentistry. J Dent Educ. 1992;56:728.

41 Kiecolt-Glaser JK, Glaser R. Depression and immune function: central pathways to morbidity and mortality. J Psychosom Res. 2002;53:873.

42 Kiyak HA. Successful aging: implications for oral health. J Public Health Dent. 2000;60:276.

43 Lin A, Kim HM, Terrell JE, et al. Quality of life after parotid-sparing IMRT for head and neck cancer: a prospective longitudinal study. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2003;57:61.

44 Locker D, Slade GD, Murray H. Epidemiology of periodontal disease among older adults: a review. Periodontol 2000. 1998;16:16.

45 Lockhart PB., Guidelines for prevention of infective endocarditis: An explanation of the changes, J Am Dent Assoc, 2S, 2008, 139, http://www.ada.org/prof/resources/topics/infective_endocarditis.asp

46 Loesche WJ, Lopatin DE. Interaction between periodontal disease, medical disease and immunity in the older individual. Periodontol 2000. 1998;16:80.

47 Macfayden D. International geriatric health promotion study/activities. In: Abdellah FG, Moore SR, editors. Proceedings of the Surgeon General’s Workshop on Health Promotion and Aging. Washington, DC: US Department of Health and Human Services, 1988.

48 McCarron PA. Bioadhesive, non-drug-loaded nanoparticles as modulators of candidal adherence to buccal epithelial cells: a potentially novel prophylaxis for candidosis. Biomaterials. 2004;25:2399.

49 Mezey M, Capezuti E, Fulmer T. Care of older adults. Nurs Clin North Am. 2004;39(3):xiii.

50 Mohammad AR, Preshaw PM, Hefti AF, et al: Subantimicrobial-dose doxycycline for treatment of periodontitis in an institutionalized geriatric population. Presented at 81st General Session of International Association for Dental Research (IADR), Goteborg, Sweden, 2003.

51 Moy PK, Medina D, Shetty V, Aghaloo TL. Dental implant failure rates and associated risk factors. Int J Oral Maxillofac Implants. 2005;20:569.

52 Padilha DM, Hilgert JB, Hugo FN, et al. Number of teeth and mortality risk in the Baltimore Longitudinal Study of Aging. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2008;63:739.