CHAPTER 42 Treatment of Periodontal Abscess

Classification of Abscesses

The periodontal abscess is a localized purulent inflammation of the periodontal tissues.6 It has been classified into three diagnostic groups: gingival abscess, periodontal abscess, and pericoronal abscess. The gingival abscess involves the marginal gingival and interdental tissues. The periodontal abscess is an infection located contiguous to the periodontal pocket and may result in destruction of the periodontal ligament and alveolar bone. The pericoronal abscess is associated with the crown of a partially erupted tooth.22

Periodontal Abscess

The periodontal abscess is typically found in patients with untreated periodontitis and in association with moderate-to-deep periodontal pockets.5,25 Periodontal abscesses often arise as an acute exacerbation of a preexisting pocket6 (Figure 42-1). Primarily related to incomplete calculus removal, periodontal abscesses have been linked to a number of clinical situations.8,15,16,24 They have been identified in patients after periodontal surgery,12 after preventive maintenance (Figure 42-2),7,10,17,21 after systemic antibiotic therapy,26 and as the result of recurrent disease.15,16 Conditions in which periodontal abscess is not related to inflammatory periodontal disease include tooth perforation or fracture2,24 (Figure 42-3) and foreign body impaction.1,23 Poorly controlled diabetes mellitus has been considered a predisposing factor for periodontal abscess formation22 (Figure 42-4). Formation of periodontal abscess has been reported as a major cause of tooth loss12-21; however, with proper treatment followed by consistent preventive periodontal maintenance, teeth with significant bone loss may be retained for many years7 (see Figure 42-10).

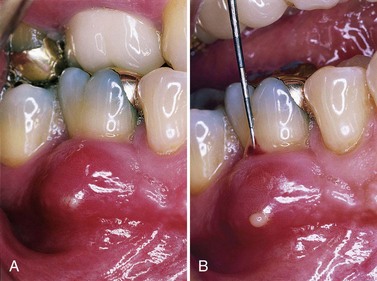

Figure 42-1 A, Deep furcation invasions are a common location for the periodontal abscess. B, Furcation anatomy often prevents the definitive removal of calculus and microbial plaque.

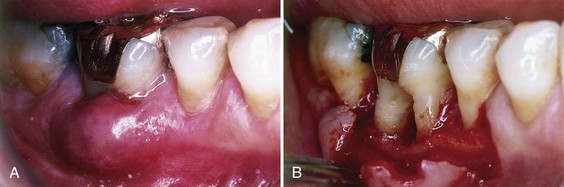

Figure 42-2 Postprophylaxis periodontal abscess resulting from partial healing of a periodontal pocket over residual calculus.

Gingival Abscess

The gingival abscess is a localized, acute inflammatory lesion that may arise from a variety of sources, including microbial plaque infection, trauma, and foreign body impaction.22 Clinical features include a red, smooth, sometimes painful, often fluctuant swelling (Figure 42-5).

Pericoronal Abscess

The pericoronal abscess results from inflammation of the soft tissue operculum, which covers a partially erupted tooth. This situation is most often observed around the mandibular third molars. As with the gingival abscess, the inflammatory lesion may be caused by the retention of microbial plaque, food impaction, or trauma.

![]() Science Transfer

Science Transfer

All patients with abscesses affecting periodontal tissues including gingiva should have a periapical radiograph that tests the vitality of the teeth in the region. This will allow the clinician to clarify if the origin of the abscess is periodontal or pulpal and thus provide the appropriate treatment. All abscesses require drainage, and periodontal abscesses can often be managed by curetting the pocket under local anesthesia to remove plaque or any other etiologic material, such as food debris, resulting in drainage of pus, blood, and edema fluid. If drainage is not obvious, then a gingival incision parallel to the long axis of the teeth may be necessary. Systemic antibiotics are only used if there is evidence of inflammatory spread beyond the gingiva in healthy patients and in immunocompromised patients and diabetics. Occlusal adjustment will often help reduce pain because the affected teeth are often extruded from the inflamed periodontal tissues. Postoperative plaque control is essential.

Appropriate treatment of acute abscesses can in some patients lead to complete resolution of the inflammation and associated bone loss, thus at least 8 weeks should pass before further treatment decisions are made.

Acute Versus Chronic Abscess

Abscesses are categorized as acute or chronic. The acute abscess is often an exacerbation of a chronic inflammatory periodontal lesion. Influencing factors include increased number and virulence of bacteria present, combined with lowered tissue resistance and lack of spontaneous drainage.11,25 The drainage may have been prevented by a deep, tortuous pocket morphology, debris, or closely adapted pocket epithelium blocking the pocket orifice. Acute abscesses are characterized by painful, red, edematous, smooth, and ovoid swelling of the gingival tissues.15,16,25 Exudate may be expressed with gentle pressure; the tooth may be percussion sensitive and feel elevated in the socket (Figure 42-6). Fever and regional lymphadenopathy are occasional findings.22

Figure 42-6 Patient presenting with acute abscess complained of dull pain and a sensation of tooth elevation in the socket. Signs of tissue distention and exudation are evident.

The chronic abscess forms after the spreading infection has been controlled by spontaneous drainage, host response, or therapy. Once homeostasis between the host and infection has been reached, the patient may have few or no symptoms.9 However, dull pain may be associated with the clinical findings of a periodontal pocket, inflammation, and a fistulous tract.22

Box 42-1 compares the signs and symptoms of the acute and chronic abscess.

BOX 42-1 Data from Dahlen G: Periodontol 2000 28:206, 2002; Meng HX: Ann Periodontol 4:79, 1999; and Sanz M, Herrera D, van Winkelhoff AJ: The periodontal abscess. In Clinical periodontology, Copenhagen, 2000, Munksgaard.

Signs and Symptoms of Periodontal Abscess

* May indicate the need for systemic antibiotics.

Periodontal Versus Pulpal Abscess

To determine the cause of an abscess and thus establish a proper treatment plan, it is often necessary to perform a differential diagnosis between a periodontal and pulpal abscess4 (Box 42-2 and Figures 42-7 and 42-8).

BOX 42-2 Modified from Corbet EF: Periodontol 2000 34:204, 2004.

Differential Diagnosis of Periodontal and Pulpal Abscess

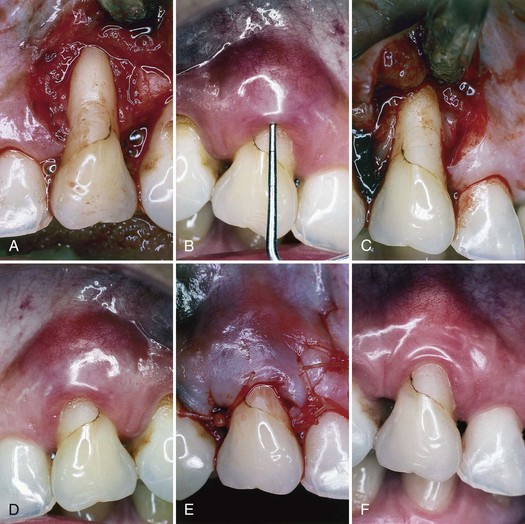

Figure 42-7 A, Maxillary right first molar with fistula on the attached gingiva. B, Using local anesthesia, periodontal probe is introduced through the fistula and angled toward the root end. C, Surgical flap elevation demonstrates failed endodontic therapy and tooth fracture as causing the fistula.

Specific Treatment Approaches

Treatment of the periodontal abscess includes two phases: resolving the acute lesion, followed by the management of the resulting chronic condition24 (Box 42-3).

BOX 42-3 Modified from Sanz M, Herrera D, van Winkelhoff AJ: The periodontal abscess. In Clinical periodontology, Copenhagen, 2000, Munksgaard.

Treatment Options for Periodontal Abscess

Acute Abscess

The acute abscess is treated to alleviate symptoms, control the spread of infection, and establish drainage.19 Before treatment, the patient’s medical history, dental history, and systemic condition are reviewed and evaluated to assist in the diagnosis and to determine the need for systemic antibiotics3 (Boxes 42-4 and 42-5).

BOX 42-5 Data from American Academy of Periodontology: J Periodontol 67:1553, 2004.

Antibiotic Options for Periodontal Infections

Drainage through Periodontal Pocket

The peripheral area around the abscess is anesthetized with sufficient topical and local anesthetic to ensure comfort. The pocket wall is gently retracted with a periodontal probe or curette in an attempt to initiate drainage through the pocket entrance (see Figure 42-8). Gentle digital pressure and irrigation may be used to express exudates and clear the pocket (Figure 42-9). If the lesion is small and access uncomplicated, debridement in the form of scaling and root planing may be undertaken.

If the lesion is large and drainage cannot be established, root debridement by scaling and root planing or surgical access should be delayed until the major clinical signs have abated.18 In these patients, use of adjunctive systemic antibiotics13-16 with short-term high-dose regimens is recommended20 (see Box 42-5). Antibiotic therapy alone without subsequent drainage and subgingival scaling is contraindicated.14

Drainage through External Incision

The abscess is dried and isolated with gauze sponges. Topical anesthetic is applied, followed by local anesthetic injected peripheral to the lesion. A vertical incision through the most fluctuant center of the abscess is made with a #15 surgical blade. The tissue lateral to the incision can be separated with a curette or periosteal elevator. Fluctuant matter is expressed, and the wound edges approximated under light digital pressure with a moist gauze pad.

In abscesses presenting with severe swelling and inflammation, aggressive mechanical instrumentation should be delayed in favor of antibiotic therapy so as to avoid damage to healthy contiguous periodontal tissues.24

Once bleeding and suppuration have ceased, the patient may be dismissed. For those who do not need systemic antibiotics, posttreatment instructions include frequent rinsing with warm salt water (1 tbsp/8-oz glass) and periodic application of chlorhexidine gluconate either by rinsing or locally with a cotton-tipped applicator. Reduced exertion and increased fluid intake are often recommended for patients showing systemic involvement. Analgesics may be prescribed for comfort. By the following day, the signs and symptoms have usually subsided. If not, the patient is instructed to continue the previously recommended regimen for an additional 24 hours. This often results in satisfactory healing, and the lesion can be treated as a chronic abscess.25

Chronic Abscess

As with a periodontal pocket, the chronic abscess is usually treated with scaling and root planing or surgical therapy. Surgical treatment is suggested when deep vertical or furcation defects are encountered that are beyond the therapeutic capabilities of nonsurgical instrumentation (Figure 42-10). The patient should be advised of the possible postoperative sequelae usually associated with periodontal nonsurgical and surgical procedures. As with the acute abscess, antibiotic therapy may be indicated.25

Figure 42-10 A, Chronic periodontal abscess of maxillary right canine. B, Using local anesthesia, periodontal probe is inserted to determine severity of the lesion. C, Using mesial and distal vertical incisions, a full-thickness flap is elevated, exposing severe bone dehiscence, a subgingival restoration, and root calculus. D, Root surface has been planed free of calculus and the restoration smoothed. E, Full-thickness flap has been replaced to its original position and sutured with absorbable sutures. F, At 3 months, gingival tissues are pink, firm, and well adapted to the tooth, with minimal periodontal probing depth.

Gingival Abscess

Treatment of the gingival abscess is aimed at reversal of the acute phase and when applicable, immediate removal of the cause. To ensure procedural comfort, topical or local anesthesia by infiltration is administered. When possible, scaling and root planing are completed to establish drainage and remove microbial deposits. In more acute situations the fluctuant area is incised with a #15 scalpel blade, and exudate may be expressed by gentle digital pressure. Any foreign material (e.g., dental floss, impression material) is removed. The area is irrigated with warm water and covered with moist gauze under light pressure.

Once bleeding has stopped, the patient is dismissed with instructions to rinse with warm salt water every 2 hours for the remainder of the day. After 24 hours the area is reassessed, and if resolution is sufficient, scaling not previously completed is undertaken. If the residual lesion is large or poorly accessible, surgical access may be required.

Pericoronal Abscess

As with the other abscesses of the periodontium, the treatment of the pericoronal abscess is aimed at management of the acute phase, followed by resolution of the chronic condition. The acute pericoronal abscess is properly anesthetized for comfort, and drainage is established by gently lifting the soft tissue operculum with a periodontal probe or curette. If the underlying debris is easily accessible, it may be removed, followed by gentle irrigation with sterile saline. If there is regional swelling, lymphadenopathy, or systemic signs, systemic antibiotics may be prescribed.

The patient is dismissed with instructions to rinse with warm salt water every 2 hours, and the area is reassessed after 24 hours. If discomfort was one of the original complaints, appropriate analgesics should be employed. Once the acute phase has been controlled, the partially erupted tooth may be definitively treated with either surgical excision of the overlying tissue or removal of the offending tooth.

1 Abrams H, Kopczyk R. Gingival sequela from a retained piece of dental floss. J Am Dent Assoc. 1983;106:57.

2 Abrams H, Cunningham C, Lee S. Periodontal changes following coronal/root perforation and formocresol pulpotomy. J Endod. 1992;18:399.

3 American Academy of Periodontology. Position paper: Systemic antibiotics in periodontics. J Periodontol. 2004;67:1553.

4 Ammons WFJr, Harrington GW. The periodontic-endodontic continuum. In Newman MG, Takei HH, Carranza FA, editors: Carranza’s clinical periodontology, ed 9, Philadelphia: Saunders, 2002.

5 Becker W, Berg L, Becker B. The long-term evaluation of periodontal treatment and maintenance in 95 patients. Int J Periodont Restor Dent. 1984;2:55.

6 Carranza FA, Camargo PM. The periodontal pocket. In Newman MG, Takei HH, Carranza FA, editors: Carranza’s clinical periodontology, ed 9, Philadelphia: Saunders, 2002.

7 Chace R, Low SB. Survival characteristics of periodontally involved teeth: a 40-year study. J Periodontol. 1993;64:701.

8 Corbet EF. Diagnosis of acute periodontal lesions. Periodontol 2000. 2004;34:204.

9 Dahlen G. Microbiology and treatment of dental abscesses and periodontal-endodontic lesions. Periodontol 2000. 2002;28:206.

10 Dello Russo NM. The post-prophylaxis periodontal abscess: etiology and treatment. Int J Periodont Restor Dent. 1985;5:29.

11 Epstein S, Scopp IW. Antibiotics and the intraoral abscess. J Periodontol. 1977;48:236.

12 Garrett S, Polson A, Stoller N, et al. Comparison of a bioabsorbable GTR barrier to a non-absorbable barrier in treating human class II furcation defects: a multi-center parallel design randomized single-blind study. J Periodontol. 1997;668:667.

13 Genco RJ. Using antimicrobials agents to manage periodontal diseases. J Am Dent Assoc. 1991;122:31.

14 Hafstrom CA, Wikstrom MB, Renvert SN, Dahlen GG. Effect of treatment on some periodontopathogens and their antibody levels in periodontal abscesses. J Periodontol. 1994;65:1022.

15 Herrera D, Roldan S, Sanz M. The periodontal abscess: a review. J Clin Periodontol. 2000;27:377.

16 Herrera D, Roldan S, Gonzalez I, Sanz M. The periodontal abscess. I. Clinical and microbiology findings. J Clin Periodontol. 2000;27:287.

17 Kaldahl WB, Kalwarf KL, Patil KD, et al. Long-term evaluation of periodontal therapy. I. Response to 4 therapeutic modalities. J Periodontol. 1996;67:93.

18 Lewis MA, MacFarlane TW. Short-course high dosage amoxicillin in the treatment of acute dento-alveolar abscess. Br Dent J. 1986;161:299.

19 Manson JD. Periodontics, ed 3. Philadelphia: Lea & Febiger; 1975.

20 Martin MV, Longman LP, Hill JB, Hardy P. Acute dentoalveolar infections: an investigation of the duration of antibiotic therapy. Br Dent J. 1997;183:135.

21 McLeod DE, Lainson PA, Spivey JD. Tooth loss due to periodontal abscess: a retrospective study. J Periodontol. 1997;68:963.

22 Meng HX. Periodontal abscess. Ann Periodontol. 1999;4:79.

23 O’Leary TJ, Standish SM, Bloomer RS. Severe periodontal destruction following impression procedures. J Periodontol. 1973;44:43.

24 Sanz M, Herrera D, van Winkelhoff AJ. The periodontal abscess. In: Clinical periodontology. Copenhagen: Munksgaard; 2000.

25 Takei HH. Treatment of the periodontal abscess. In Newman MG, Takei HH, Carranza FA, editors: Carranza’s clinical periodontology, ed 9, Philadelphia: Saunders, 2002.

26 Topoll H, Lange D, Muller R. Multiple periodontal abscesses after systemic antibiotic therapy. J Clin Periodontol. 1990;17:268.