CHAPTER 44 Plaque Control for the Periodontal Patient

Plaque control is the regular removal of microbial plaque and the prevention of its accumulation on the teeth and adjacent gingival surfaces. Microbial plaque is the major etiology of periodontal diseases and is related to dental caries; therefore gaining patient cooperation in daily plaque removal is critical to long-term success of all periodontal and dental treatment.4,5

Microbial plaque control is an effective way of treating and preventing gingivitis and is a critical part of all the procedures involved in the treatment and prevention of periodontal diseases.52 In 1965, Löe et al92 conducted the classic study demonstrating the relationship between microbial plaque accumulation and the development of experimental gingivitis in humans. Subjects in the study stopped brushing and other plaque control procedures, resulting in the development of gingivitis in every person within 7 to 21 days. The composition of the plaque bacteria also shifted so that gram-negative organisms predominated, and these changes were shown to be reversible. Daily removal of microbial plaque led to complete resolution of gingival inflammation for all subjects within 1 week. Good supragingival plaque control has also been shown to affect the growth and composition of subgingival plaque, so that it favors a healthier microflora and reduces calculus formation.122 Carefully performed daily home plaque control, combined with frequent professionally delivered plaque and calculus removal, reduces the amount of supragingival plaque; decreases the total number of microorganisms in moderately deep pockets, including furcation areas; and greatly reduces the quantity of periodontal pathogens.32,63

Microbial plaque growth occurs within hours, and it must be completely removed at least once every 48 hours in the experimental setting with periodontally healthy subjects to prevent inflammation.121 The American Dental Association (ADA) recommends that individuals brush twice per day and use floss or other interdental cleaners once per day to effectively remove microbial plaque and prevent gingivitis.9 They recommendation twice daily brushing because most individuals do not adequately remove microbial plaque at one brushing and doing it a second time improves the results.

Periodontal lesions are predominantly found in interdental locations, so toothbrushing alone is not sufficient to control gingival and periodontal diseases.78 It has been demonstrated in healthy subjects that plaque formation begins on the interproximal surfaces where the toothbrush does not reach. Masses of plaque first develop in the molar and premolar areas, followed by the proximal surfaces of the anterior teeth and the facial surfaces of the molars and premolars. Lingual surfaces accumulate the least amount of plaque. Patients consistently leave more plaque on the posterior teeth than the anterior teeth, with interproximal surfaces retaining the highest amounts of plaque, exactly the places in which periodontal infections begin.121 In addition, periodontal patients have increased susceptibility to disease,125 complex defects in gingival architecture, and long exposed root surfaces to clean, compounding the difficulty of doing a thorough job.

Chemical inhibitors of plaque and calculus that are incorporated in mouthwashes or dentifrices also play important roles in controling microbial plaque.8 Also fluorides delivered through toothpastes and mouthrinses are essential for caries control.10 Many products are available as adjunctive agents to mechanical techniques. These medicaments, as with any drug, should be recommended and prescribed according to the needs of individual patients.

![]() Science Transfer

Science Transfer

Plaque control is the most essential element of successful periodontal therapy for all patients. Toothbrushing is the one technique that all patients need. Many patients can get effective plaque control using hand brushes, but powered toothbrushes offer improvements for patients that have reduced dexterity or who need a short-term motivational nudge to upgrade their time spent in oral hygiene. Soft nylon bristled toothbrushes directed at the gingival margin and used without a scrubbing motion are the most effective.

Antimicrobial mouthwashes, such as chlorhexidine, essential oil containing mixtures, and cetylpyridinium, can add to the mechanical plaque removal of brushes. In some patients, the combination of toothbrushing with an antimicrobial mouthwash can be as effective as brushing and flossing in removing interdental plaque. Patients with open embrasures can utilize interdental brushes because these are easier to use and more effective than floss in these cases.

Plaque control is one of the key elements of the practice of dentistry. It permits each patient to assume responsibility for oral health on a daily basis. Without it, optimal oral health through periodontal treatment cannot be attained or preserved.

The Toothbrush

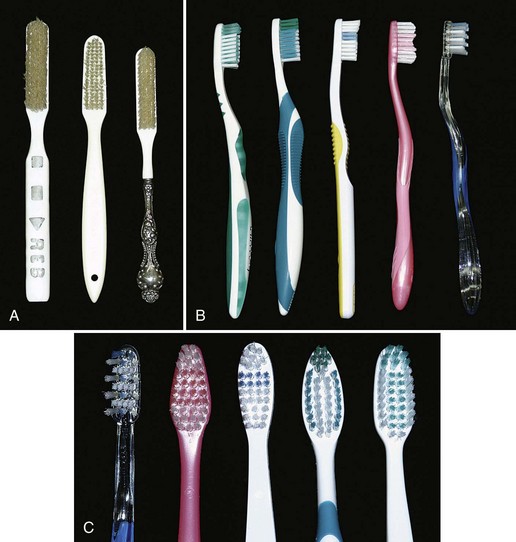

Toothbrushes vary in size and design as well as in length, hardness, and arrangement of the bristles116 (Figure 44-1). Some toothbrush manufacturers claim superiority of design for such factors as minor modifications of bristle placement, length, and stiffness. These claims are primarily based on plaque removal shown to be significantly superior to other toothbrushes in clinical studies. However, the research does not show significant differences in gingivitis scores or bleeding indices, which are the more important measures of improved gingival health. It is questionable whether slight differences in microbial plaque removal are clinically significant because no toothbrush can remove all microbial plaque. In fact, at least one study compared four commercially available toothbrushes for total plaque removal at a single brushing; all four toothbrushes removed plaque equally, and the authors concluded that no one design was superior to others.28

Figure 44-1 Manual toothbrushes. A, Toothbrushes from the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, one with an ivory handle from about 1890 (left), one with a composition handle from the 1950s (center), and one with a sterling silver handle from the early twentieth century (right). The ivory-handled brush belonged to a dental student who used the handle to practice cutting preparations and filling the “preps” with amalgam or gold foil. B, Various types of toothbrushes are available; note the variation in brush head and handle design. C, Brush heads, showing various bristle configurations.

(Antique brushes courtesy Dean John D.B. Featherstone, University of California, San Francisco School of Dentistry Historical Collection, San Francisco.)

When recommending a particular toothbrush, ease of use by the patient and the perception that the brush works well are important considerations. The effectiveness of and potential injury from different types of brushes depend to a great degree on how the brushes are used. Data from in vitro studies of abrasion by different manual toothbrushes suggest that brush designs permitting the bristles to carry more toothpaste while brushing contribute to abrasion more than brush bristles themselves.35 However, all agree that use of hard toothbrushes, vigorous horizontal brushing, and use of extremely abrasive dentifrices may lead to cervical abrasions of teeth and recession of gingiva.79

Toothbrush Design

Toothbrush bristles are grouped in tufts that are usually arranged in three or four rows. Rounded bristle ends cause fewer scratches on the gingiva than flat-cut bristles with sharp ends31,116 (see Figure 44-1). Two types of bristle material are used in toothbrushes: natural bristles from hogs and artificial filaments made of nylon. Both remove microbial plaque, but nylon bristle brushes vastly predominate in the market.20 Bristle hardness is proportional to the square of the diameter and inversely proportional to the square of bristle length.58 Diameters of common bristles range from 0.007 inch (0.2 mm) for soft brushes to 0.012 inch (0.3 mm) for medium brushes and 0.014 inch (0.4 mm) for hard brushes.65 Soft bristle brushes of the type described by Bass16 have gained wide acceptance. Preference for handle characteristics is entirely a matter of taste.

Opinions regarding the merits of hard and soft bristles are based on studies that are not comparable, often inconclusive, and contradict one another.66 Softer bristles are more flexible, clean slightly below the gingival margin when used with a sulcular brushing technique,17 and reach farther onto the proximal surfaces.47 Use of hard-bristled toothbrushes is associated with more gingival recession, and frequent brushers who use hard bristles have more recession than those who use soft bristles.77 However, the manner in which a brush is used and the abrasiveness of the dentifrice affect the abrasion to a greater degree than the bristle hardness itself.1,96 Bristle hardness does not significantly affect wear on enamel surfaces.109

The amount of force used to brush is not critical for effective plaque removal.127 Vigorous brushing is not necessary and can lead to gingival recession, wedge-shaped defects in the cervical area of root surfaces,46,110 and painful ulceration of the gingiva.104

Toothbrushes must also be replaced periodically, although the amount of visible bristle wear does not appear to affect plaque removal for up to 9 weeks.30 The ADA recommends that toothbrushes be replaced every 3 to 4 months.9

Powered Toothbrushes

Electrically powered toothbrushes designed to mimic back-and-forth brushing techniques were invented in 1939. Subsequent models featured circular or elliptical motions, and some had combinations of motions. Currently, powered toothbrushes have oscillating and rotating motions (Figure 44-2), and some brushes use low-frequency acoustic energy to enhance cleaning ability. Powered toothbrushes rely primarily on mechanical contact between the bristles and the tooth to remove plaque. The addition of low-frequency acoustic energy generates dynamic fluid movement and provides cleaning slightly away from the bristle tips.45 The vibrations have also been shown to interfere with bacterial adherence to oral surfaces. Neither the sonic vibration nor the mechanical motion of powered toothbrushes has been shown to affect bacterial cell viability.94 Hydrodynamic shear forces created by these brushes disrupt plaque a short distance from the bristle tips, explaining the additional interproximal plaque removal.70

Typically, comparison studies of powered toothbrushes, manual toothbrushes, or other powered devices demonstrate slightly improved plaque removal for the device of interest in a short-term clinical trial.98,108 A recent Cochrane review reported that only mechanical brushes with oscillating and rotating motions reduced microbial plaque 11% and demonstrated 6% greater reduction in gingival bleeding than manual brushing. These improvements were maintained over 3 months. Although long-term benefits have not been established, this particular style of mechanical brush resulted in better microbial plaque and gingivitis reduction in a number of well-controlled studies.60

Patient acceptance of powered toothbrushes is good. One study reported that 88.9% of patients introduced to a powered toothbrush would continue to use it.130 However, patients have also been reported to quit using powered toothbrushes after 5 or 6 months, presumably when the novelty is gone. Powered toothbrushes have been shown to improve oral health for (1) children and adolescents, (2) children with physical or mental disabilities, (3) hospitalized patients, including older adults who need to have their teeth cleaned by caregivers, and (4) patients with fixed orthodontic appliances. Powered brushes have not been shown to provide benefits routinely for patients with rheumatoid arthritis, children who are well-motivated brushers, or patients with chronic periodontitis.61

Dentifrices

Dentifrices aid in cleaning and polishing tooth surfaces. They are used mostly in the form of pastes, although tooth powders and gels are also available. Dentifrices are made up of abrasives (e.g., silicon oxides, aluminum oxides, and granular polyvinyl chlorides), water, humectants, soap or detergent, flavoring and sweetening agents, therapeutic agents (e.g., fluorides, pyrophosphates), coloring agents, and preservatives.59,97 Composing 20% to 40% of dentifrices, abrasives are insoluble inorganic salts that enhance the abrasive action of toothbrushing as much as 40 times.96 Tooth powders are much more abrasive than pastes and contain about 95% abrasive materials. The abrasive quality of dentifrices affects enamel only slightly and is a much greater concern for patients with exposed roots. Dentin is abraded 25 times faster and cementum 35 times faster than enamel, so root surfaces are easily worn away, leading to notching and tooth sensitivity.120 Oral hygiene procedures mainly cause hard tissue damage from abrasive dentifrices, although gingival lesions can also be produced104,109 (Figure 44-3). Dentifrices are very useful for delivering therapeutic agents to the teeth and gingiva. The pronounced caries-preventive effect of fluorides incorporated in dentifrices has been proved beyond question.119 Fluoride ion must be available in the amount of 1000 to 1100 parts per million (ppm) to achieve caries reduction effects. Toothpaste products that have been tested by the ADA and have fluoride ion available in the appropriate amount carry the ADA seal of approval for caries control and can be relied on to provide caries protection.10

Figure 44-3 Vigorous toothbrushing with an abrasive dentifrice can result in trauma to the gingiva and wearing away of the tooth surfaces, especially root surfaces, and can contribute to gingival recession.

“Calculus control toothpastes,” also referred to as “tartar control toothpastes,” contain pyrophosphates and have been shown to reduce the deposition of new calculus on teeth. These ingredients interfere with crystal formation in calculus but do not affect the fluoride ion in the paste or increase tooth sensitivity. Dentifrice with pyrophosphates has been shown to reduce the formation of new supragingival calculus by 30% or more.73,95,135 Pyrophosphate-containing toothpastes do not affect subgingival calculus formation or gingival inflammation. The inhibitory effects reduce the deposition of new supragingival calculus but do not affect existing calculus deposits. To achieve the greatest effect from calculus control toothpaste, the patient’s teeth must be cleaned and completely free of supragingival calculus when starting to use the product daily.

Toothbrushing Methods

Many methods for brushing the teeth have been described and promoted as being efficient and effective. These methods can be categorized primarily according to the pattern of motion when brushing and are primarily of historic interest, as follows71:

Roll: Roll3 or modified Stillman technique67

Vibratory: Stillman,118 Charters,25 and Bass17 techniques

Circular: Fones technique44

Vertical: Leonard technique85

Horizontal: Scrub technique132

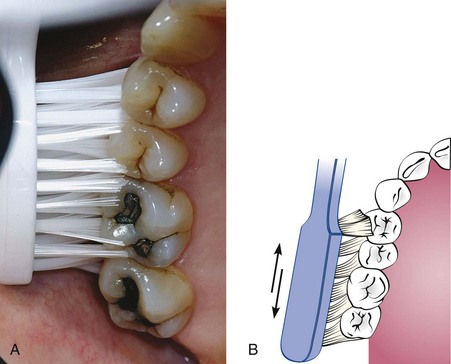

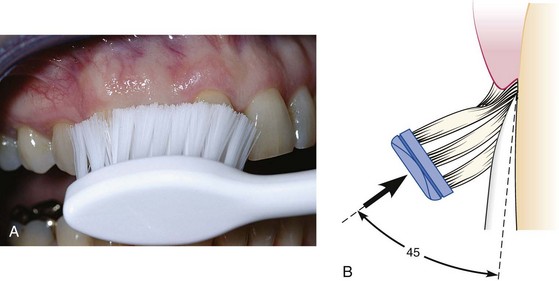

Patients with periodontal disease are most frequently taught a sulcular brushing technique using a vibratory motion to improve access in the gingival areas. This is referred to as “target hygiene.”123 The method most often recommended is the Bass technique because it emphasizes sulcular placement of bristles, adapting the bristle tips to the gingival margin to reach the supragingival plaque and accessing subgingival plaque to the extent possible. A controlled vibrating motion is used to dislodge microbial plaque and avoid trauma. The brush is systematically placed on all the teeth in both arches. Figures 44-4 and 44-5 illustrate this brushing technique.

Figure 44-4 Bass method. A, Place the toothbrush so that the bristles are angled approximately 45 degrees from the tooth surfaces. B, Start at the most distal tooth in the arch, and use a vibrating, back-and-forth motion to brush.

Figure 44-5 Bass method. A, Proper position of the brush in the mouth aims the bristle tips toward the gingival margin. B, Diagram shows the ideal placement, which permits slight subgingival penetration of the bristle tips.

Bass Technique17

Brushing with Powered Toothbrushes

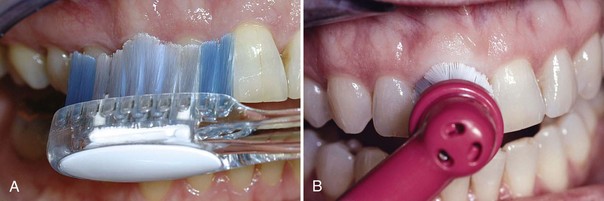

The various mechanical motions built into powered toothbrushes do not require special techniques. The patient needs only place the brush head next to the teeth at the gingival margin, using a targeted hygiene approach, and proceed systematically around the dentition.126 A routine method of brushing all the teeth, similar to the method described for manual brushing, should also be used with powered toothbrushes (Figure 44-6).

Interdental Cleaning Aids

Any toothbrush, regardless of the brushing method used, does not completely remove interdental plaque. This is true for all brushers, even periodontal patients with wide-open embrasures.49,112 Daily interdental plaque removal is crucial to augment the effects of toothbrushing because most dental and periodontal diseases originate in interproximal areas.2

Tissue destruction associated with periodontal disease often leaves large, open spaces between teeth and long, exposed root surfaces with anatomic concavities and furcations. These areas are both difficult for patients to clean and poorly accessible to the toothbrush.78 Patients need to understand that the purpose of interdental cleaning is to remove microbial plaque, not just dislodge food wedged between teeth. Many tools are available for interproximal cleaning and they should be recommended based on the size of interdental spaces, presence of furcations, tooth alignment, and presence of orthodontic appliances or fixed prostheses. Also, ease of use and patient cooperation are important considerations. Common aids are dental floss and interdental cleaners such as wooden or plastic tips and interdental brushes.

Dental Floss

Dental floss is the most widely recommended tool for removing plaque from proximal tooth surfaces.48 Floss is made from nylon filaments or plastic monofilaments, and can be waxed, unwaxed, thick, thin, and even flavored.7 Some prefer monofilament flosses made of a nonstick material because they are slick and do not fray. Clinical research has demonstrated no significant differences in the ability of the various types of floss to remove dental plaque; they all work equally well.42,64,75,76 Waxed dental floss was thought to leave a waxy film on proximal surfaces, thus contributing to plaque accumulation and gingivitis. It has been shown, however, that wax is not deposited on tooth surfaces105 and that improvement in gingival health is unrelated to the type of floss used.42 Factors influencing the choice of dental floss include the tightness of tooth contacts, roughness of proximal surfaces, and the patient’s manual dexterity, not the superiority of any one product. Therefore recommendations about type of floss should be based on ease of use and personal preference.

Technique

The floss must contact the proximal surface from line angle to line angle to clean effectively. It must also clean the entire proximal surface, including accessible subginigival areas, not just be slipped apical into the contact area. The following is a brief description of flossing technique:

Figure 44-8 Dental floss technique. The floss is slipped between the contact area of the teeth (in this case, teeth #7 and #8), is wrapped around the proximal surface, and removes plaque by using several up-and-down strokes. The process must be repeated for the distal surface of tooth #8.

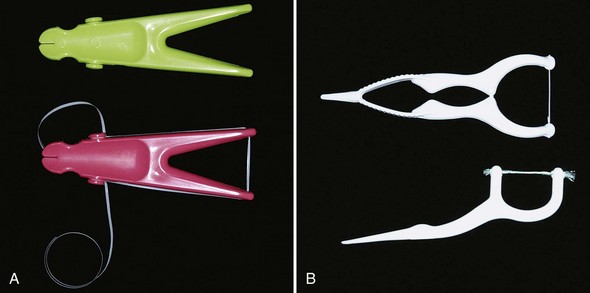

Flossing can be facilitated by using a floss holder (Figure 44-9, A). Floss holders are helpful for patients lacking manual dexterity and for caregivers assisting patients in cleaning their teeth. A floss holder should be rigid enough to keep the floss taut when penetrating into tight contact areas, and it should be simple to string with floss. The disadvantage is that floss tools are time-consuming because they must be rethreaded frequently when the floss shreds.

Figure 44-9 Floss holders can simplify the manipulation of dental floss. A, Reusable floss tools require stringing the floss around a series of knobs and grooves to secure it. B, Disposable floss tools have prestrung floss and are easy to use, but the floss may shred and break, requiring several tools to complete flossing the teeth.

Disposable, single-use floss holders with prethreaded floss are also available. Short-term clinical studies suggest that plaque reduction and improvement in gingivitis scores are similar for patients using disposable floss devices as for patients who hold the floss with their fingers23,117 (Figure 44-9, B).

Powered flossing devices are also available (Figure 44-10). The devices have been shown to be safe and effective, but no better at plaque removal than holding the floss in the fingers.29,54

Figure 44-10 Powered flossing devices can be easier for some patients to use than handheld floss. The tip is inserted into the proximal space, and a bristle or wand comes out of the tip and moves in a circular motion when the device is turned on (left). Alternately, the device moves the prestrung floss in short motions to provide interproximal cleaning (right).

Establishing a lifelong habit of flossing the teeth is difficult to achieve for both patients and dentists, regardless of whether one uses a tool or flosses with the fingers. In fact, the daily use of floss is universally low. It has been reported that only about 8% of young teenagers in Great Britain floss daily,93 with similar percentages reported for other countries.78 No information is available about the establishment of long-term flossing habits comparing the various tools to finger flossing. However, the tools may be useful to help some individuals begin flossing or to make flossing possible if patients have limited dexterity.

Interdental Cleaning Devices

Concave root surfaces and furcations are often present in periodontal patients who have experienced significant attachment loss and recession, and they are not cleaned well with dental floss. A comparison study of dental floss and interdental brushes used by patients with moderate to severe periodontal disease showed that the interproximal brushes removed slightly more interproximal plaque and that subjects found them easier to use than dental floss. However, no differences were seen in probe depth reductions or bleeding indices.26 Therefore interproximal cleaning aids, such as interdental brushes, are adequate for proximal cleaning of teeth when interdental spaces permit access.78

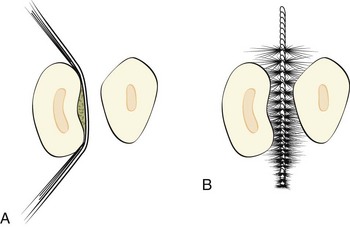

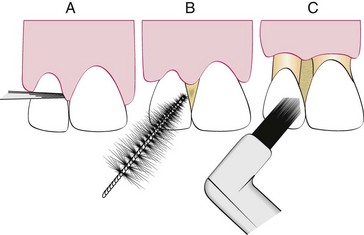

Embrasure spaces vary greatly in size and shape. Figure 44-11 provides a representation of the size and anatomy of three types of embrasures and the type of interdental cleaner often recommended for each. As a general rule, the larger the space, the larger the device used to clean it should be.

Figure 44-11 Interproximal embrasure spaces vary greatly in patients with periodontal disease. In general, A, embrasures with no gingival recession are adequately cleaned using dental floss; B, larger spaces with exposed root surfaces require the use of an interproximal brush; and C, single-tufted brushes clean efficiently in interproximal spaces with no papillae.

Interdental Brushes

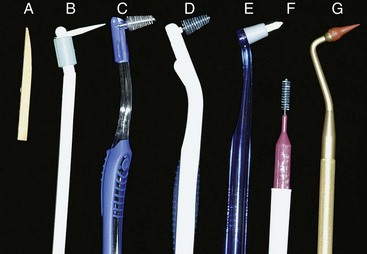

A wide variety of interdental cleaning devices are available for removing microbial plaque from between the teeth (Figure 44-12). The most common types are conical or cylindrical brushes, tapered wooden toothpicks that are round or triangular in cross section, and single-tufted brushes. Many interdental devices have handles for convenient manipulation around the teeth and in posterior areas. Clinical research has shown that the devices are effective on lingual and facial tooth surfaces as well as on proximal surfaces.78,112,128

Figure 44-12 Interproximal cleaning devices include wooden tips (A and B), interproximal brushes (C to F), and rubber tip stimulators (G).

Technique

Interdental brushes of any style are inserted through interproximal spaces and moved back and forth between the teeth with short strokes. For the most efficient cleaning, the diameter of brush should be slightly larger than the gingival embrasures to be cleaned. This size permits bristles to exert pressure on both proximal tooth surfaces, working their way into concavities on the roots.

Single-tufted brushes provide access to furcation areas, or isolated areas of deep recession, and work well on the lingual surfaces of mandibular molars and premolars. These areas are often missed when using a toothbrush.

Wooden or Rubber Tips

Wooden toothpicks are used either with or without a handle (see Figure 44-12, A and B). Access is easier from the buccal surfaces for tips without handles but is limited primarily to the anterior and bicuspid areas. Wooden toothpicks used on handles improve access to all areas and have been shown to be as effective as dental floss in reducing plaque and bleeding scores in subjects with gingivitis.87 Triangular wooden tips are also available; this design is most useful in the anterior areas when used from the buccal surfaces of the teeth. Rubber tips are conical and are mounted on handles or the ends of toothbrushes; they can be easily adapted to all proximal surfaces in the mouth. Plastic tips that resemble wooden or rubber tips are also available and are used in the same way. Both rubber and plastic tips can be rinsed and reused and are easily carried in a pocket or purse.

Technique

Toothpicks are common devices and readily available in most homes. They can be used around all surfaces of the teeth when attached to commercially available handles (see Figure 44-12, B). Once mounted on the handle, the toothpick is broken off so that it is only 5- or 6-mm long. The tip of the toothpick is used to trace along the gingival margin and into the proximal areas from both the facial and the lingual surface of each tooth (Figure 44-13). Toothpicks mounted on handles are efficient for cleaning along the gingival margin,48 can penetrate into periodontal pockets and furcations, and permit patients to target their hygiene efforts at the gingival margin.123

Figure 44-13 Wooden toothpick. A, The tip is a common wooden toothpick held in a handle and broken off. It is used to clean subgingivally and reach into periodontal pockets. B, The tip can also be used to clean along the gingival margins of the teeth and reach under the gingiva.

Soft, triangular wooden picks or plastic alternatives are placed in the interdental space with the base of the triangle resting on the gingiva and the sides in contact with the proximal tooth surfaces (Figure 44-14). The pick is then repeatedly moved in and out of the embrasure to remove plaque. The disadvantage of triangular wooden or plastic tips is that they do not reach well into the posterior areas or on the lingual surfaces.

Figure 44-14 Triangular wooden tips are also popular with patients. The tip is inserted between the teeth, with the triangular portion resting on the gingival papilla. The tip is moved in and out to remove plaque; however, it is very difficult to use on posterior teeth and from the lingual aspect of all teeth.

Rubber tips should be placed into the embrasure space, resting on the gingiva, and used in a circular motion. They can be applied to interproximal spaces and other defects throughout the mouth and are easily adaptable to lingual surfaces.

Recommendations

Gingival Massage

Massaging the gingiva with a toothbrush or an interdental cleaning devices produces epithelial thickening, increased keratinization, and increased mitotic activity in the epithelium and connective tissue.21,24,51 The increased keratinization occurs only on the oral gingiva and not on the areas more vulnerable to microbial attack: the sulcular epithelium and the interdental areas where the gingival col is present. Epithelial thickening, increased keratinization, and increased blood circulation have not been shown to be beneficial for restoring gingival health.50 Improved gingival health associated with interdental stimulation is much more likely the result of microbial plaque removal than gingival massage.

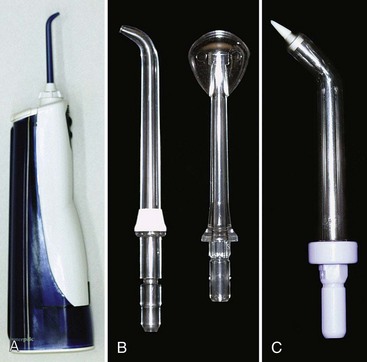

Figure 44-16 Oral irrigation. A, The most common oral irrigators have a built-in pump and reservoir. B, Conventional plastic tips are used for daily supragingival irrigation at home by the patient. Left, Tip for gingival irrigation. Right, Tip for cleaning dorsal surface of the tongue. C, Soft rubber tip is used for daily subgingival irrigation by the patient at home.

Figure 44-17 Effect of a disclosing agent. A, Unstained, the teeth look clean, but close inspection shows subtle signs of gingivitis. B, Plaque shows as dark-red particulate matter when stained with a disclosing dye. It is useful to demonstrate toothbrushing in the patient’s mouth with the teeth disclosed and plaque visible.

Oral Irrigation

Supragingival Irrigation

Oral irrigators for daily home use by patients work by directing a pulsating stream of water through a nozzle to the tooth surfaces. Most often, a device with a built-in pump generates the pressure (Figure 44-16, A). Oral irrigators clean nonadherent bacteria and debris from the oral cavity more effectively than toothbrushes and mouth rinses. They are particularly helpful for removing debris from inaccessible areas around orthodontic appliances and fixed prostheses. When used as adjuncts to toothbrushing, these devices can have a beneficial effect on periodontal health by reducing the accumulation of microbial plaque and calculus69,90,107 and decreasing inflammation and pocket depth.6,22,107

Oral irrigation has been shown to disrupt and detoxify subgingival plaque and can be useful in delivering antimicrobial agents into periodontal pockets.6 Daily supragingival irrigation with dilute chlorhexidine for 6 months resulted in significant reductions in bleeding and gingivitis compared with water irrigation and chlorhexidine rinse controls. Irrigation with water alone also reduced gingivitis significantly but not as much as the dilute chlorhexidine.43

Technique

Subgingival Irrigation

Subgingival irrigation can be performed both in the dental office and at home by the patient, particularly when antimicrobial agents are used. Home irrigation is performed by aiming or placing the irrigation tip into the periodontal pocket, attempting to insert the tip at least 3 mm, using a soft rubber tip34 (see Figure 44-16, C). Irrigation performed in the dental office, also called lavage or flushing of the periodontal pocket, as a one-time treatment after scaling and root planing, has not been shown to improve clinical healing, and data do not support its use in improving therapeutic results.6,56,113

Subgingival irrigation performed with an oral irrigator using chlorhexidine diluted to one-third strength and performed regularly at home and after scaling, root planing, and in-office irrigation therapy has produced significant gingival improvement compared with controls.56,72,113 Subgingival irrigation has been shown to disrupt more than half the subgingival plaque68 and reach about half the depth of pockets, up to 7 mm, much further apically than a toothbrush or floss can reach.36 These data suggest that patients can benefit from daily subgingival irrigation, particularly in difficult sites such as furcations and residual pockets. A more detailed discussion of irrigation is presented in Chapter 46.

Technique

The soft rubber irrigator tip reduces the pressure and flow of the pulsating jet of water (see Figure 44-16, C) when inserted subgingivally and permits penetration of irrigant of up to 70% of pocket depth in laboratory simulation.27,68 The subgingival irrigation tip should be gently inserted into pockets or furcation areas, 3 mm if possible, and each pocket should be flushed for a few seconds.

One caution must be considered. Transient bacteremia has been reported after water irrigation in patients with periodontitis41 and patients receiving periodontal maintenance therapy.129 However, bacteremia has also been found after toothbrushing102 and is known to occur in a significant number of patients after scaling alone.129 Subgingival irrigation at home is not the oral hygiene procedure of choice for patients requiring antibiotic prophylaxis before dental treatment, particularly if extensive inflammation is present.34 For these patients, supragingival irrigation used in combination with toothbrushing and other interdental cleaning aids is recommended.

Caries Control

Dental caries, particularly root caries, is a problem for periodontal patients because of attachment loss associated with the disease process and periodontal therapeutic procedures. Root caries develops through a process similar to coronal caries, involving the alternating cycle of demineralization and remineralization of the surfaces and other risk factors associated with diet and salivary flow. The demineralization process requires the fermentation of carbohydrates in the plaque by oral bacteria, resulting in loss of mineral from the root surface. Lactobacillus and Streptococcus species are involved in the root caries process, as with coronal caries. The major difference is that the amount of organic material in the root surfaces is greater than in enamel, so once the demineralization has occurred, the organic matrix—mostly collagen—is exposed. Organic material is then further broken down by bacterial enzymes, resulting in rapid destruction of the root surface.38,131

Fluoride works primarily by topical effects to prevent and reverse the caries process, whether in enamel, cementum, or dentin. Low concentrations of topical fluoride inhibit demineralization, enhance remineralization, and inhibit the enzyme activity in bacteria by acidifying the cells.39,40 Adult patients benefit from the prevention and reversal of root caries provided by low-concentration topical fluoride delivered by toothpastes or other topical applications.39 It also has been demonstrated that the use of fluoride dentifrice containing 5000 ppm of fluoride was more effective in reversing active root caries lesions than the fluoride level of 1100 ppm found in conventional toothpastes.18

Chemical Plaque Control with Oral Rinses

Improved understanding of the infectious nature of dental diseases has dramatically increased interest in chemical methods of plaque control and holds great promise for advances in disease control and prevention. The ADA Council on Scientific Affairs has adopted a program for acceptance of chemical plaque control agents. The agents must be evaluated in placebo-controlled clinical trials of 6 months or longer that demonstrate significantly improved gingival health compared with controls. To date, the ADA has accepted two agents for treatment of gingivitis: prescription solutions of chlorhexidine digluconate oral rinse and nonprescription essential oil mouthrinse.

Prescription Chlorhexidine Rinse

The agent that has shown the most positive antibacterial results to date is chlorhexidine, a diguanidohexane with pronounced antiseptic properties. Several clinical investigations confirmed the initial finding that 2 daily rinses with 10 ml of a 0.2% aqueous solution of chlorhexidine digluconate almost completely inhibited the development of microbial plaque, calculus, and gingivitis in the human model for experimental gingivitis.57 Clinical studies of several months’ duration have reported plaque reductions of 45% to 61% and more importantly, gingivitis reductions of 27% to 67%.57,82 The 0.12% chlorhexidine digluconate preparation available in the United States for reducing plaque and gingivitis has been shown to be equally effective as the higher-concentration product.74,80

Localized, reversible side effects to chlorhexidine use occur, primarily brown staining of the teeth, tongue, and silicate and resin restorations82 and transient impairment of taste perception.91 Chlorhexidine has very low systemic toxic activity in humans, has not produced any appreciable resistance of oral microorganisms, and has not been associated with teratogenic alterations.80 The preparation contains 12% alcohol, which may be of interest to clinicians and patients over concerns that alcohol increases the risk of oropharyngeal cancer. However, an extensive review of the available epidemiologic evidence associating alcohol-containing oral rinse preparations with cancer concluded that existing data do not support this association.37,115 Recently a nonalcoholic form of chlorhexidine mouthrinse has become available. It has been shown to be equally effective for microbial plaque control15,88 and may be preferred by patients.

Nonprescription Essential Oil Rinse

Essential oil mouthrinses contain thymol, eucalyptol, menthol, and methyl salicylate. These preparations have been evaluated in long-term clinical studies and demonstrated plaque reductions of 20% to 35% and gingivitis reductions of 25% to 35%.33,53,79 This type of oral rinse has a long history of daily use and safety since the nineteenth century, and many patients have used the products for decades. These products also contain alcohol (up to 24% depending on the preparation), so some patients prefer not to use them.

Other Products

A preparation containing triclosan has shown some effectiveness in reducing plaque and gingivitis. It is available in toothpaste form, and the active ingredient is more effective in combination with zinc citrate or a copolymer of methoxyethylene.13 Other oral rinse products on the market have shown some evidence of plaque reduction, although long-term improvement in gingival health has not been substantiated. These include stannous fluoride, cetylpyridinium chloride (quaternary ammonia compounds), and sanguinarine. Evidence suggests that these and other available mouth rinse products do not possess the antimicrobial potential of either chlorhexidine products or essential oil preparations.97,103

One type of agent has been marketed as a prebrushing oral rinse to improve the effectiveness of toothbrushing. The active ingredient is sodium benzoate. Research to support its effectiveness is contradictory, but the preponderance of evidence suggests that using a prebrushing rinse is no more effective than brushing alone.19,20

Chemical plaque control has been shown to be effective for both plaque reduction and improved wound healing after periodontal surgery.111 Both chlorhexidine11 and essential oil134 mouthrinses have significant positive effects when prescribed for use after periodontal surgery for 1 to 4 weeks.

Recommendations

Disclosing Agents

Disclosing agents are solutions or wafers capable of staining bacterial deposits on the surfaces of teeth, tongue, and gingiva. These can be used as educational and motivational tools to improve the efficiency of plaque control procedures12 (Figure 44-17). Solutions are applied to the teeth as concentrates on cotton swabs or diluted as rinses. They usually produce heavy staining of bacterial plaque, gingiva, tongue, lips, and fingers, as well as the sink. Wafers are crushed between the teeth and swished around the mouth for a few seconds and then spit out. Either form can be used for plaque control instruction in the office and dispensed for home use to aid periodontal patients in evaluating the effectiveness of their oral hygiene routines.

Frequency of Plaque Removal

In the controlled and supervised environment of clinical research, where well-trained individuals remove all visible plaque, gingival health can be maintained by one thorough cleaning with brush, floss, and toothpicks every 24 to 48 hours.32,71,78,81 However, most patients fall far short of this goal. The average daily home care routine lasts less than 2 minutes and removes only 40% of plaque.34 It has been reported that improved plaque removal and therefore improved periodontal health is associated with increasing the frequency of brushing to twice per day.71,99 Cleaning three or more times per day does not appear to further improve periodontal conditions.

Patient Motivation and Education

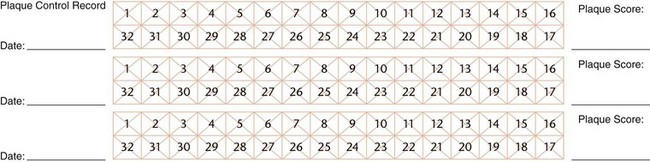

In periodontal therapy, plaque control has two important purposes: to minimize gingival inflammation and to prevent the recurrence or progression of periodontal diseases and caries. Daily mechanical removal of plaque by the patient, including the use of appropriate antimicrobial agents, is the only practical means for improving oral health on a long-term basis. The process requires interest on the part of the patient and education and instruction from the dentist, followed by encouragement and reinforcement. Keeping records of patient performance facilitates this process. Figure 44-18 provides an example of a plaque control record that permits repeated measures and comparison over time.

Motivation for Effective Plaque Control

Motivating patients to perform effective plaque control is one of the most critical and difficult elements of long-term success in periodontal therapy. It requires both commitment by the patient to change daily habits and regular return visits for maintenance and reinforcement. The scope of this compliance problem is immense. It has been shown that patients stop using interproximal cleaning aids after a very short time. Heasman et al62 followed 100 patients treated for moderate to severe periodontal disease and taught to use one or more interdental cleaning aids. It was found that only 20% used the aids after 6 months. Of those who had started using three devices, one-third had stopped all interdental cleaning at 6 months; the others used one or two of the aids.68 The situation is no better when looking at patient willingness to return for office visits. In one study of 1280 patients, most of whom had periodontal surgery in multiple sites after intensive scaling, root planing, and plaque control instruction, 25% never returned for a follow-up visit; only 40% returned regularly.100 Wilson et al133 reported that 67% of periodontal patients were noncompliant with return visits in a 20-year retrospective of a private periodontal practice.

Adopting new habits and returning for office visits is not an impossible task. To be successful, the patient (1) must be receptive and understand the concepts of pathogenesis, treatment, and prevention of periodontal disease; (2) must be willing to change the habits of a lifetime; and (3) must be able to adjust personal beliefs, practices, and values to accommodate new regimens. Manual skills must be developed to establish an effective plaque control regimen. In addition, the patient must understand the dentist’s critical role in treating and maintaining periodontal health.106 If not, long-term success of treatment is much less likely.

Education and Scoring Systems

Many patients prefer to believe that treatment is a passive process, so it is incumbent on the dentist to educate and reinforce to each patient their personal role in long-term success of therapy. Our health-conscious society is an advantage with regard to patient education. Most patients know what gingivitis is because they have heard about it on television or read about it in magazines or on the web. They are willing to spend time and money to try new products such as toothbrushes and mouthrinses.

Patients must also be informed that periodic assessment and debridement of the teeth in the dental office are required to prevent recurrence of periodontal diseases and identify problems that may arise. These procedures work best when combined with an individualized oral hygiene regimen practiced daily at home. Therefore time spent in the dental office teaching the patient how to perform microbial plaque control procedures is central to care. Patients sometimes have the concept that “cleanings” every few months are sufficient for microbial plaque removal and disease control. Only the combination of regular office visits with conscientious home care has been shown to significantly reduce gingivitis and loss of supporting periodontal tissues over the long term.89,127

Periodontal patients should be shown how periodontal disease has manifested in their own mouth. Stained dental plaque, the bleeding of inflamed gingiva, and demonstrations of the periodontal probe inserted into pockets are impressive demonstrations of the presence of pathogens and symptoms of disease. It also is of educational value to patients to have their oral cleanliness and periodontal condition recorded periodically14 so that improvements in performance can be used for positive reinforcement. The plaque control record and the bleeding points index are simple indices and useful for patient education and motivation.

Plaque Control Record (O’Leary Index).101

Have the patient use a disclosing solution or tablet and examine each tooth surface (except occlusal surfaces) for the presence or absence of stained plaque at the dentogingival junction. Plaque is recorded on the appropriate box in a diagram for four surfaces on each tooth. After all teeth have been scored, the index number is calculated for the percentage of surfaces with plaque by dividing the number of surfaces with microbial plaque by the total number of surfaces scored and then multiplying by 100. A reasonable goal for patients is 10% or fewer surfaces with plaque. If plaque is always present in the same areas, provide instructions to improve plaque control in those areas. It is extremely difficult to achieve a perfect score of 0, so patients should be rewarded for approaching it.

Some frequently used plaque indices do not require staining the teeth such as the plaque index of Silness and Löe.114 These are more convenient to use and often more acceptable to patients, but they are not as dramatic for patient education.

Bleeding Points Index.84

The bleeding points index provides an evaluation of gingival inflammation around each tooth in the patient’s mouth. Retract the cheek, and place the periodontal probe 1 mm into the sulcus or pocket at the distal aspect of the most posterior tooth in the quadrant on the buccal surface. Carry the probe lightly across the length of the sulcus to the mesial interproximal area on the facial aspect. Continue along all the teeth in the quadrant from the facial aspect. Wait 30 seconds, and record the presence of bleeding on the distal, facial, and mesial surfaces on the chart. Repeat on the lingual-palatal aspect, recording bleeding only for the direct lingual surface, not for the mesial or distal surfaces. This results in four separate scores for each tooth and does not score the mesial and distal surfaces twice. Repeat the steps for each quadrant. The percentage of the number of bleeding surfaces is calculated by dividing the number of surfaces that bled by the total number of tooth surfaces (four per tooth) and by multiplying by 100 to convert the score to a percentage. This index is designed to demonstrate gingival inflammation characterized by bleeding rather than presence of microbial plaque. Again, a goal of 10% or fewer bleeding points is good, but 0 is ideal. If a few bleeding points repeatedly occur in the same areas, plaque control for those areas should be reinforced or modified.

Significance of Plaque Scores and Bleeding Scores

Plaque scores are helpful as indicators of patient compliance and success with daily plaque control procedures. However, plaque levels themselves do not necessarily reflect gingival health or risk of disease progression, even though plaque is highly correlated with the presence of gingivitis.92 Bleeding is a much better indicator of predicting success in controlling inflammation and reducing the chance of disease progression. Although bleeding on probing is not the most specific or sensitive measures of health, it has a strong negative correlation to disease progression. If bleeding is absent at any given site in the mouth, reflecting good plaque control and disease management, it is unlikely that periodontal disease will progress.83

Instruction and Demonstration

Patients can reduce the incidence of plaque and gingivitis with repeated instruction and encouragement much more effectively than with self-acquired oral hygiene habits.55,112 However, instruction in how to clean teeth must be more than a cursory chairside demonstration on the use of a toothbrush. It is a painstaking procedure that requires patient participation, careful supervision with correction of mistakes, and reinforcement during return visits, until the patient achieves the necessary proficiency.86 Any strategy for introducing plaque control to the periodontal patient includes several elements. At the first instruction visit, the patient should be given a new toothbrush, an interdental cleaner, and a disclosing agent. The patient’s plaque should be disclosed because dental plaque otherwise is difficult for the patient to see (see Figure 44-17). Polished dental restorations do not take up the stain, but the oral mucosa and the lips may retain it for up to several hours. Use petroleum jelly to keep the dye off the patient’s lips.

Toothbrushing should be demonstrated in the patient’s mouth while the patient observes using a hand mirror. The patient then repeats the procedures with the dentist giving assistance, correction, and positive reinforcement. Repeat the demonstration and instruction process with dental floss and interdental cleaning aids according to the patient’s needs.

Encourage patients to clean the teeth thoroughly at least once a day. Be sure to inform them that home care procedures on a full dentition take 5 to 10 minutes, and for complex periodontal cases, home care procedures may take 30 minutes. The patient should set aside a convenient time and place in the daily schedule to perform the procedures reliably every day. Subsequent instruction visits should be used to reinforce or modify previous instructions, periodically recording the state of gingival health and amount of plaque.

Some strategies simply do not work. Waiting until the end of the appointment, for example, when the patient is sore, exhausted, and possibly anesthetized is not conducive to learning. Failing to provide positive reinforcement, handing the patient too many tools, and relying only on pamphlets and printed material to provide education are likely to result in an insufficient or ineffective instruction process.

Recommendations

The following list provides some strategies that will assist you in educating and motivating your patients:

Summary

1 Abrasivity of current dentifrices. Report of the Council of Dental Therapeutics. J Am Dent Assoc. 1970;81:1177.

2 Addy M, Adriaens P. Epidemiology and etiology of periodontal diseases and the role of plaque control in dental caries. In: Lang NP, Ättstrom R, Löe H, editors. Proceedings of the European Workshop on Mechanical Plaque Control. Chicago: Quintessence, 1998.

3 American Academy of Periodontology, Committee Report: The tooth brush and methods of cleaning the teeth. Dent Items Int. 1920;42:193.

4 American Academy of Periodontology. Position Paper: Guidelines for periodontal therapy. J Periodontol. 2001;72:1624.

5 American Academy of Periodontology. Position Paper: Periodontal maintenance. J Periodontol. 2003;74:1395.

6 American Academy of Periodontology. Position Paper: The role of supra- and subgingival irrigation in the treatment of periodontal diseases. J Periodontol. 2005;76:2015.

7 American Dental Association. ADA Seal of Acceptance Program: Floss and other interdental cleaners. www.ada.org/ada/seal/floss.asp, June 25, 2009.

8 American Dental Association. ADA Seal of Acceptance Program: Mouthrinses. www.ada.org/ada/seal/mouthrinses.asp, June 25, 2009.

9 American Dental Association. ADA Seal of Acceptance Program: Toothbrushes. www.ada.org/ada/seal/toothbrushes.asp, June 25, 2009.

10 American Dental Association. ADA Seal of Acceptance Program: Toothpaste. www.ada.org/ada/seal/toothpaste.asp, June 25, 2009.

11 Anderson L, Sanz M, Newman MG, et al. Clinical effects of a 0.12% chlorhexidine mouthrinse on periodontal surgical wounds without periodontal dressing. J Dent Res. 1988;67:329. (abstract 1728)

12 Arnim SS. The use of disclosing agents for measuring tooth cleanliness. J Periodontol. 1963;34:227.

13 Arweiler NB, Henning G, Reich E, Netuschil L. Effect of an amine-fluoride-triclosan mouthrinse on plaque regrowth and biofilm vitality. J Clin Perio. 2002;29:358.

14 Barrikman R, Penhall O. Graphing indexes reduce plaque. J Am Dent Assoc. 1973;87:1404.

15 Bascones A, Morante S, Mateos L, et al. Influence of additional active ingredients on the effectiveness of non-alcoholic chlorhexidine mouthwashes: a randomized controlled trial. J Periodontol. 2005;76:1469.

16 Bass CC. The optimum characteristics of toothbrushes for personal oral hygiene. Dent Items Int. 1948;70:697.

17 Bass CC. An effective method of personal oral hygiene. Part II. J La State Med Soc. 1954;106:100.

18 Baysan A, Lynch E, Ellwood R, et al. Reversal of primary root caries using dentifrices containing 5000 and 1100 ppm fluoride. Caries Res. 2001;35:41.

19 Beiswander BB, Mallott MC, Mau MS, et al. The relative plaque removal effect of a prebrushing mouthrinse. J Am Dent Assoc. 1990;120:190.

20 Binney A, Addy M, Newcombe RG. The plaque removal effects of single rinsings and brushings. J Periodontol. 1993;64:181.

21 Cantor MT, Stahl SS. The effects of various interdental stimulators upon the keratinization of the interdental col. Periodontics. 1965;3:243.

22 Cantor MT, Stahl SS. Interdental col tissue responses to the use of a water pressure device. J Periodontol. 1969;40:292.

23 Carter-Hanson C, Gadbury-Amyot C, Killoy WJ. Comparison of the plaque removal efficacy of a new flossing aid (Quik-Floss) to finger flossing. J Clin Periodontol. 1996;23:873.

24 Castenfelt T. Toothbrushing and massage in periodontal disease: an experimental clinical histologic study. Stockholm: Nordisk Rotegravyr; 1952.

25 Charters WJ. Eliminating mouth infections with the toothbrush and other stimulating instruments. Dent Digest. 1932;38:130.

26 Christou V, Timmerman MF, van der Velden U, et al. Comparison of different approaches of interdental oral hygiene: interdental brushes versus dental floss. J Periodontol. 1998;69:759.

27 Ciancio SC. Clinical benefits of powered subgingival irrigation. Biol Ther Dent. 1992;8:13.

28 Claydon N, Addy M. Comparative single-use plaque removal by toothbrushes of different designs. J Clin Periodontol. 1996;23:1112.

29 Cronin M, Dembling W. An investigation of the efficacy and safety of a new electric interdental plaque remover for the reduction of interproximal plaque and gingivitis. J Clin Dent. 1996;7:74.

30 Daly CG, Chapple CC, Cameron AC. Effect of toothbrush wear on plaque control. J Clin Periodontol. 1996;23:45.

31 Danser MM, Timmerman MF, Ijzerman Y, et al. Evaluation of the incidence of gingival abrasion as a result of toothbrushing. J Clin Periodontol. 1998;25:701.

32 De la Rosa MR, Guerra JZ, Johnston DA, et al. Plaque growth and removal with daily toothbrushing. J Periodontol. 1979;50:661.

33 De Paola LG, Overholser CD, Meiller TF, et al. Chemotherapeutic reduction of plaque and gingivitis development: a 6 month investigation. J Dent Res. 1986;65:274. (abstract 941)

34 Drisko CH. Nonsurgical periodontal therapy: pharmacotherapeutics. Ann Periodontol. 1996;1:491.

35 Dyer D, Addy M, Newcombe RG. Studies in vitro of abrasion by different manual toothbrush heads and a standard toothpaste. J Clin Periodontol. 2000;27:99.

36 Eakle WS, Ford C, Boyd RL. Depth of penetration in periodontal pockets with oral irrigation. J Clin Periodontol. 1986;13:39.

37 Elmore JG, Horwitz JI. Oral cancer and mouthwash use: evaluation of the epidemiologic evidence. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1995;113:253.

38 Featherstone JD. Fluoride, remineralization and root caries. Am J Dent. 1994;7:271.

39 Featherstone JD. Prevention and reversal of dental caries: role of low level fluoride. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 1999;27:31.

40 Featherstone JD. The science and practice of caries prevention. J Am Dent Assoc. 2000;131:887.

41 Felix JA, Rosen S, App GR. Detection of bacteremia after the use of an oral irrigation device in subjects with periodontitis. J Periodontol. 1971;42:785.

42 Finkelstein P, Grossman E. The effectiveness of dental floss in reducing gingival inflammation. J Dent Res. 1979;58:1034.

43 Flemmig TF, Newman MG, Doherty FM, et al. Supragingival irrigation with 0.06% chlorhexidine in naturally occurring gingivitis. I. Six month clinical observations. J Periodontol. 1990;61:112.

44 Fones AC. Mouth hygiene, ed 4. Philadelphia: Lea & Febiger; 1934.

45 Forgas-Brockmann LB, Carter-Hanson C, Killoy WJ. The effects of an ultrasonic toothbrush on plaque accumulation and gingival inflammation. J Clin Periodontol. 1998;25:375.

46 Gillette WB, van House RL. Ill effects of improper oral hygiene procedures. J Am Dent Assoc. 1980;101:476.

47 Gilson CM, Charbeneau GT, Hill HC. A comparison of physical properties of several soft toothbrushes. J Mich Dent Assoc. 1969;51:347.

48 Gjermo P, Flotra L. The plaque removing effect of dental floss and toothpicks: A group comparison study. J Periodontal Res. 1969;4:170. (abstract)

49 Gjermo P, Flotra L. The effect of different methods of interdental cleaning. J Periodontal Res. 1970;5:230.

50 Glickman I, Petralis R, Marks R. The effect of powered toothbrushing plus interdental stimulation upon the severity of gingivitis. J Periodontol. 1964;35:519.

51 Glickman I, Petralis R, Marks R. The effect of powered toothbrushing and interdental stimulation upon microscopic inflammation and surface keratinization of the interdental gingiva. J Periodontol. 1965;36:108.

52 Goodson JM, Palys MD, Carpino E, et al. Microbiological changes associated with dental prophylaxis. J Am Dent Assoc. 2004;135:1159.

53 Gordon JM, Lamster IV, Seiger MC. Efficacy of Listerine antiseptic in inhibiting the development of plaque and gingivitis. J Clin Periodontol. 1985;12:697.

54 Gordon JM, Frascella JA, Reardon RC. A clinical study of the safety and efficacy of a novel electric interdental cleaning device. J Clin Dent. 1996;7:70.

55 Gravelle HR, Shackelford NF, Lovett JT. The oral hygiene of high school students as affected by three different educational programs. J Public Health Dent. 1967;27:91.

56 Greenstein G. Effects of subgingival irrigation on periodontal status. J Periodontol. 1987;58:827.

57 Grossman E, Reiter G, Sturzenberger OP, et al. Six-month study of the effects of a chlorhexidine mouthrinse on gingivitis in adults. J Periodontal Res. 1986;21(suppl):33.

58 Harrington JH, Terry IA. Automatic and hand toothbrushing abrasion studies. J Am Dent Assoc. 1964;68:343.

59 Harris NO. Dentifrices, mouth rinses, and oral irrigators. In Harris NO, Christen AG, editors: Primary preventive dentistry, ed 3, East Norwalk, Conn: Appleton & Lange, 1991.

60 Heanue M, Deacon SA, Deery C, et al. Manual versus powered toothbrushing for oral health. Cochrane Rev. 2004:2.

61 Heasman PA, McCracken GI. Powered toothbrushes: a review of clinical trials. J Clin Periodontol. 1999;26:407.

62 Heasman PA, Jacobs DJ, Chapple IL. An evaluation of the effectiveness and patient compliance with plaque control methods in the prevention of periodontal disease. J Clin Prev Dent. 1989;11:24.

63 Hellstrom MK, Ramberg P, Krok L, et al. The effects of supragingival plaque control on subgingival microflora in human periodontitis. J Clin Periodontol. 1996;23:934.

64 Hill HC, Levi PA, Glickman I. The effects of waxed and unwaxed dental floss on interdental plaque accumulation and interdental gingival health. J Periodontol. 1973;44:411.

65 Hine MK. Toothbrush. Int Dent J. 1956;6:15.

66 Hiniker JJ, Forscher BK. The effect of toothbrush type on gingival health. J Periodontol. 1954;25:40.

67 Hirschfeld I. The toothbrush, its use and abuse. Dent Items Int. 1931;3:833.

68 Hollander BN, Boyd RL, Eakle WS. Comparison of subgingivally placed cannula oral irrigator tip with a supragingivally placed standard irrigator tip. J Clin Periodontol. 1992;19:340.

69 Hoover DR, Robinson HB, Billingsley A. The comparative effectiveness of the Water-Pik in a noninstructed population. J Periodontol. 1968;39:43. (abstract)

70 Hope CK, Petrie A, Wilson M. In vitro assessment of the plaque-removing ability of hydrodynamic shear forces produces beyond the bristles by 2 electric toothbrushes. J Periodontol. 2003:1017.

71 Jepson S. The role of manual toothbrushes in effective plaque control: advantages and limitations. In: Lang NP, Ättstrom R, Löe H, editors. Proceedings of the European Workshop on Mechanical Plaque Control. Chicago: Quintessence, 1998.

72 Jolkovsky DL, Waki MY, Newman MN, et al. Clinical and microbiological effects of subgingival and gingival marginal irrigation with chlorhexidine gluconate. J Periodontol. 1990;61:663.

73 Kazmierczak M, Mather M, Ciancio S, et al. A clinical evaluation of anticalculus dentifrices. J Clin Prev Dent. 1990;12:13.

74 Keijser J, Verkade H, Timmerman M, et al. Comparison of 2 commercially available chlorhexidine mouthrinses. J Periodontol. 2003;74:214.

75 Keller SE, Manson-Hing LR. Clearance studies of proximal tooth surfaces. Part II. In vivo removal of interproximal plaque. Ala J Med Sci. 1969;6:266.

76 Keller SE, Manson-Hing LR. Clearance studies of proximal tooth surfaces. Parts III and IV. In vivo removal of interproximal plaque. Ala J Med Sci. 1969;6:399.

77 Khocht A, Simon G, Person P, et al. Gingival recession in relation to history of hard toothbrush use. J Periodontol. 1993;64:900.

78 Kinane DF. The role of interdental cleaning in effective plaque control: need for interdental cleaning in primary and secondary prevention. In: Lang NP, Ättstrom R, Löe H, editors. Proceedings of the European Workshop on Mechanical Plaque Control. Chicago: Quintessence, 1998.

79 Lamster IB, Alfano MC, Seiger MC, et al. The effect of Listerine antiseptic on reduction of existing plaque and gingivitis. J Clin Prev Dent. 1983;5:12.

80 Lang NP, Brecx MC. Chlorhexidine digluconate: an agent for chemical plaque control and prevention of gingival inflammation. J Periodontal Res. 1986;21(suppl):74.

81 Lang NP, Cumming BR, Löe H. Toothbrushing frequency as it relates to plaque development and gingival health. J Periodontol. 1973;44:396.

82 Lang NP, Hotz P, Graf H, et al. Effects of supervised chlorhexidine mouthrinses in children: a longitudinal clinical trial. J Periodontal Res. 1982;17:101.

83 Lang NP, Joss A, Orsanic T, et al. Bleeding on probing: a predictor for the progression of periodontal diseases? J Clin Periodontol. 1986;13:590.

84 Lenox JA, Kopczyk RA. A clinical system for scoring a patient’s oral hygiene performance. J Am Dent Assoc. 1973;86:849.

85 Leonard JF. Conservative treatment of periodontoclasia. J Am Dent Assoc. 1939;26:1308.

86 Less W. Mechanics of teaching plaque control. Dent Clin North Am. 1972;16:647.

87 Lewis MW, Holder-Ballard C, Selders RJJr, et al. Comparison of the use of a toothpick holder to dental floss in improvement of gingival health in humans. J Periodontol. 2004;75:551.

88 Leyes Borrajo JL, Garcia Varela L, Lopez Castro G, et al. Efficacy of chlorhexidine mouthrinses with and without alcohol: a clinical study. J Periodontol. 2002;73:317.

89 Lindhe J, Nyman S. The effect of plaque control and surgical pocket elimination on the establishment and maintenance of periodontal health: a longitudinal study of periodontal therapy in cases of advanced disease. J Clin Periodontol. 1975;2:67.

90 Lobene RR. The effect of a pulsed water pressure cleaning device on oral health. J Periodontol. 1969;40:667.

91 Löe H. Does chlorhexidine have a place in the prophylaxis of dental disease? J Periodontal Res. 1973;8(suppl 12):93.

92 Löe H, Theilade E, Jensen SB. Experimental gingivitis in man. J Periodontol. 1965;36:177.

93 Macgregor ID, Balding JW, Regis D. Flossing behaviour in English adolescents. J Clin Periodontol. 1998;25:291.

94 MacNeill S, Walter DM, Day A, et al. Sonic and mechanical toothbrushes an in vitro study showing altered microbial surface structures but lack of effect on viability. J Clin Periodontol. 1998;25:988.

95 Mallatt ME, Beiswanger BB, Stookey GK, et al. Influence of soluble pyrophosphates on calculus formation in adults. J Dent Res. 1985;64:1159.

96 Manly RS, Brudevold F. Relative abrasiveness of natural and synthetic toothbrush bristles on cementum and dentin. J Am Dent Assoc. 1957;55:779.

97 Mauriello SM, Bader JD. Six-month effects of a sanguinarine dentifrice on plaque and gingivitis. J Periodontol. 1988;59:238.

98 McKendrick AJ, Barbenel LM, McHugh WD. A two-year comparison of hand and electric toothbrushes. J Periodontal Res. 1968;3:224.

99 McKendrick AJ, Barbenel LM, McHugh WD. The influence of time of examination, eating, smoking, and frequency of brushing on the oral debris index. J Periodontal Res. 1970;5:205.

100 Novaes AB, Novaes ABJr, Moraes N, et al. Compliance with supportive periodontal therapy. J Periodontol. 1996;67:213.

101 O’Leary TJ, Drake RB, Naylor JE. The plaque control record. J Periodontol. 1972;43:38.

102 O’Leary TJ, Shafer WG, Swenson HM, et al. Possible penetration of crevicular tissue from oral hygiene procedures. II. Use of the toothbrush. J Periodontol. 1970;41:158.

103 Parsons LG, Thomas LG, Southard GL, et al. Effect of sanguinaria extract on established plaque and gingivitis when supragingivally delivered as a manual rinse or under pressure in an oral irrigator. J Clin Periodontol. 1987;14:381.

104 Pattison GA. Self-inflicted gingival injuries: literature review and case report. J Periodontol. 1983;54:299.

105 Perry DA, Pattison G. The investigation of wax residue on tooth surfaces after the use of waxed dental floss. Dent Hygiene. 1986;60:16.

106 Renvert S, Glavind L. Individualized instruction and compliance in oral hygiene practices: recommendations and means of delivery. In: Lang NP, Ättstrom R, Löe H, editors. Proceedings of the European Workshop on Mechanical Plaque Control. Chicago: Quintessence, 1998.

107 Robinson HB, Hoover PR. The comparative effectiveness of a pulsating oral irrigator as an adjunct in maintaining oral health. J Periodontol. 1971;42:37.

108 Robinson P, Deacon SA, Deery C, et al. Manual versus powered toothbrushing for oral health. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2009. Issue 2

109 Sangnes G. Traumatization of teeth and gingiva related to habitual tooth cleaning procedures. J Clin Periodontol. 1976;3:94.

110 Sangnes G, Gjermo P. Prevalence of oral soft and hard tissue lesions related to mechanical tooth cleaning procedures. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 1976;4:77.

111 Sanz M, Herrera D. Role of oral hygiene during the healing phase of periodontal therapy. In: Lang NP, Ättstrom R, Löe H, editors. Proceedings of the European Workshop on Mechanical Plaque Control. Chicago: Quintessence, 1998.

112 Schmid MO, Balmelli O, Saxer UP. The plaque removing effect of a toothbrush, dental floss and a toothpick. J Clin Periodontol. 1976;3:157.

113 Shiloah J, Hovious LA. The role of subgingival irrigations in the treatment of periodontitis. J Periodontol. 1993;64:835.

114 Silness J, Löe H. Periodontal disease in pregnancy. II. Correlation between oral hygiene and periodontal condition. Acta Odontol Scand. 1964;22:121.

115 Silverman SJr, Wilder R. Antimicrobial mouthrinse as part of a comprehensive oral care regimen. J Am Dent Assoc. 2006;137(suppl 3):22s.

116 Silverstone LM, Featherstone MJ. A scanning electron microscope study of the end rounding of bristles in eight toothbrush types. Quintessence Int. 1988;19:87.

117 Spolsky VA, Perry DA, Meng Z, et al. Evaluating the efficacy of a new flossing aid. J Clin Periodontol. 1993;20:490.

118 Stillman PR. A philosophy of the treatment of periodontal disease. Dent Digest. 1932;38:314.

119 Stookey G. Are all fluoride dentifrices the same? In: Wei SHY, editor. Clinical uses of fluorides. Philadelphia: Lea & Febiger, 1985.

120 Stookey GK, Muhler JC. Laboratory studies concerning the enamel and dentin abrasion properties of common dentifrice polishing agents. J Dent Res. 1968;47:524.

121 Straub AM, Salvi GE, Lang NP. Supragingival plaque formation in the human dentition. In: Lang NP, Ättstrom R, Löe H, editors. Proceedings of the European Workshop on Mechanical Plaque Control. Chicago: Quintessence, 1998.

122 Suomi JD, Green JC, Vermillion JR, et al. The effect of controlled oral hygiene procedures on the progression of periodontal disease in adults: results after two years. J Periodontol. 1969;40:416.

123 Takei HH: Targeted hygiene. Personal communication. June 2009.

124 Tedesco LA, Keffler MA, Davis EL, et al. Effect of a social cognitive intervention on oral health status, behavior reports, and cognition. J Periodontol. 1992;63:567.

125 Teles RP, Patel M, Socransky SS, Haffajee AD. Disease progression in periodontally healthy and maintenance subjects. J Periodontol. 2008;79:784.

126 Tritten CB, Armitage GA. Comparison of a sonic and a manual toothbrush for efficacy in supragingival plaque removal and reduction of gingivitis. J Clin Periodontol. 1996;23:641.

127 Van der Weijden GA, Timmerman MF, Danser MM, et al. Relationship between the plaque removal efficacy of a natural toothbrush and brushing force. J Clin Periodontol. 1998;25:413.

128 Waerhaug J. The interdental brush and its place in operative and crown and bridge dentistry. J Oral Rehabil. 1976;3:107.

129 Waki MY, Jolkovsky DL, Otomo-Corgel J, et al. Effects of subgingival irrigation on bacteremia following scaling and root planing. J Periodontol. 1990;61:405.

130 Warren PR, Ray TS, Cugini M, et al. A practice-based study of a power toothbrush: assessment of effectiveness and acceptance. J Am Dent Assoc. 2000;131:389.

131 Wefel JS. Root caries histopathology and chemistry. Am J Dent. 1994;7:261.

132 Wilkins EM, Oral disease control: toothbrushes and toothbrushing,, Clinical practice of the dental hygienist, ed 6, 1992, Lea & Febiger, Philadelphia

133 Wilson TGJr, Glover ME, Schoen J, et al. Compliance with maintenance therapy in a private dental practice. J Periodontol. 1984;55:468.

134 Yukna RA, Broxson AW, Mayer ET, et al. Comparison of Listerine mouthwash and periodontal dressing following periodontal flap surgery. Clin Prev Dent. 1986;4:14.

135 Zacheri WA, Pheiffer HJ, Swancar JR. The effect of soluble pyrophosphates on dental calculus in adults. J Am Dent Assoc. 1985;110:737.

Suggested Readings

American Academy of Periodontology. Position Paper: Guidelines for periodontal therapy. J Periodontol. 2001;72:1624.

American Academy of Periodontology. Position Paper: Periodontal maintenance. J Periodontol. 2003;74:1395.

American Academy of Periodontology. Position Paper: The role of supra- and subgingival irrigation in the treatment of periodontal diseases. J Periodontol. 2005;76:2015.

Featherstone JD. Prevention and reversal of dental caries: role of low level fluoride. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 1999;27:31.

Lewis MW, Holder-Ballard C, Selders RJJr, et al. Comparison of the use of a toothpick holder to dental floss in improvement of gingival health in humans. J Periodontol. 2004;75:551.

Leyes Borrajo JL, Garcia Varela L, Lopez Castro G, et al. Efficacy of chlorhexidine mouthrinses with and without alcohol: a clinical study. J Periodontol. 2002;73:317.

Lindhe J, Nyman S. The effect of plaque control and surgical pocket elimination on the establishment and maintenance of periodontal health: a longitudinal study of periodontal therapy in cases of advanced disease. J Clin Periodontol. 1975;2:67.

Robinson P, Deacon SA, Deery C, et al. Manual versus powered toothbrushing for oral health. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2009. Issue 2

Warren PR, Ray TS, Cugini M, et al. A practice-based study of a power toothbrush: assessment of effectiveness and acceptance. J Am Dent Assoc. 2000;131:389.

Wilson TGJr, Glover ME, Schoen J, et al. Compliance with maintenance therapy in a private dental practice. J Periodontol. 1984;55:468.