CHAPTER 79 Results of Periodontal Treatment

The prevalence of periodontal disease, the resulting high rate of tooth mortality, and the potential for multiple systemic health complications aggravated by chronic periodontitis raise an important question: Is periodontal treatment effective in preventing and controlling the chronic infection and progressive destruction of periodontal disease? Current concepts of evaluating health care require a scientific basis for treatment, referred to as evidence-based therapy. Evidence is now overwhelming that periodontal therapy is effective in preventing periodontal disease, slowing the destruction of the periodontium, and reducing tooth loss.

Prevention and Treatment of Gingivitis

For many years, the belief that good oral hygiene is necessary for the successful prevention and treatment of gingivitis has been widespread among periodontists. In addition, worldwide epidemiologic studies have confirmed a close relationship between the incidence of gingivitis and lack of oral hygiene.5,6

Löe and co-workers17,36 provided conclusive evidence on the association between oral hygiene and gingivitis. After 9 to 21 days without performing oral hygiene measures, healthy dental students with previously excellent oral hygiene and healthy gingiva developed heavy accumulations of plaque and generalized mild gingivitis. When oral hygiene techniques were reinstituted, the plaque in most areas disappeared in 1 or 2 days, and gingival inflammation in these areas disappeared approximately 1 week after the plaque was removed. Thus gingivitis is reversible and can be resolved by daily, effective plaque removal.

A number of long-term studies have shown that gingival health can be maintained by a combination of effective oral hygiene maintenance and scaling procedures.*

A 3-year study was conducted on 1248 General Telephone workers in California to determine whether progression of gingival inflammation is reduced in an oral environment in which high levels of hygiene are maintained.34,35 Experimental and control groups were computer-matched based on periodontal and oral hygiene status, past caries experience, age, and gender. During the study period, several procedures were instituted to ensure that the oral hygiene status of the experimental group was maintained at a high level. Subjects were given a series of frequent oral prophylaxis treatments combined with oral hygiene instruction. Subjects in the control group received no attention from the study team except for annual examinations. They were advised to continue their usual daily practices and accustomed visits for professional care. After 3 years, the increase in plaque and debris in the control group was four times as great as that in the experimental group. Similarly, gingivitis scores were much higher in control subjects than in the matching experimental group. Therefore chronic marginal gingivitis can be controlled with good oral hygiene and dental prophylaxis.

Prevention and Treatment of Loss of Attachment

Although periodontal therapy has been used for more than 100 years, it is only since the mid 1970s that a number of studies have been conducted to determine the effect of treatment on reducing the progressive loss of periodontal support for the natural dentition.

Prevention of Loss of Attachment

Löe et al18,19 conducted a longitudinal investigation to study the natural development and progression of periodontal disease. The first study group, established in Oslo, Norway, in 1969, consisted of 565 healthy male nondental students and academicians between 17 and 40 years of age. Oslo was selected mainly because this city had an ongoing preschool, school, and postschool dental program offering systematic preventive, restorative, endodontic, orthodontic, and surgical therapy on an annual recall basis for all children and adolescents, complete with a documented attendance record, for the previous 40 years. Members of the study population had experienced maximum exposure to conventional dental care throughout their lives. A second study group, established in Sri Lanka in 1970, consisted of 480 male tea laborers between 15 and 40 years of age. They were healthy and well built by local standards, and their nutritional condition was clinically fair. The workers had never been exposed to any programs relative to the prevention or treatment of dental diseases. Toothbrushing was unknown, and dental caries was virtually nonexistent.

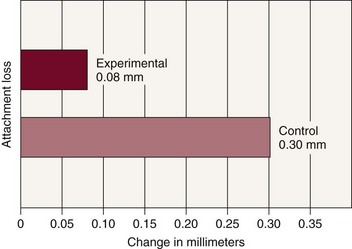

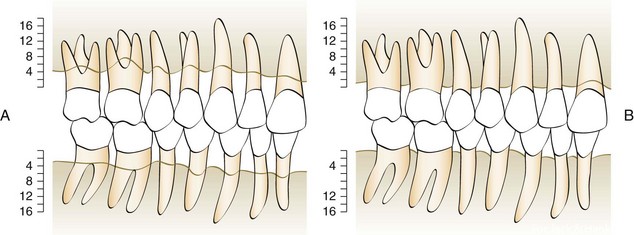

The results of this study are interesting. As the members of the Norwegian group approached 40 years of age, the mean individual loss of attachment was slightly above 1.5 mm and the mean annual rate of attachment loss was 0.08 mm for interproximal surfaces and 0.10 mm for buccal surfaces. As the Sri Lankans approached 40 years of age, the mean individual loss of attachment was 4.50 mm, and the mean annual rate of progression of the lesion was 0.30 mm for interproximal surfaces and 0.20 mm for buccal surfaces. Figure 79-1 shows a graphic interpretation of the difference between the two groups. This study suggests that without interference, periodontal lesions progress continually and at a relatively even pace.

Figure 79-1 A, Mean periodontal support of teeth of Sri Lankan tea laborers at approximately 40 years of age. B, Mean periodontal support of teeth of Norwegian academicians at approximately 40 years of age.

(From Löe H, Anerud A, Boysen H, et al: J Periodontol 49:607, 1978.)

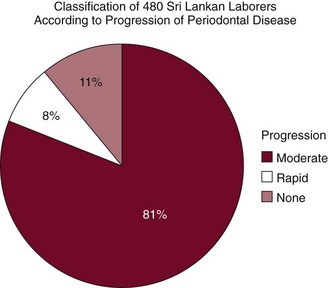

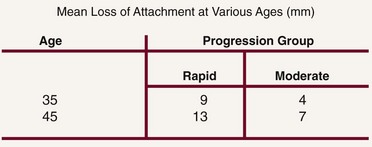

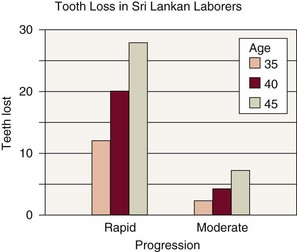

Further analysis of the Sri Lankan laborers showed that they were not all losing attachment at the same rate (Figures 79-2 and 79-3).18 Virtually all gingival areas showed inflammation, but attachment loss varied tremendously. Based on interproximal loss of attachment and tooth mortality, three subpopulations were identified as individuals with “rapid progression” (RP) of periodontal disease (8%), individuals with “moderate progression” (MP) (81%), and individuals who exhibited “no progression” (NP) of periodontal disease beyond gingivitis (11%). At age 35, the mean loss of attachment in the RP group was 9 mm; in the MP group, 4 mm; and in the NP group, less than 1 mm. At the age of 45, the mean loss of attachment in the RP group was 13 mm and in the MP group, 7 mm. Therefore, under natural conditions and in the absence of therapy, 89% of the Sri Lankan laborers had severe periodontitis that progressed at much greater rates than in the Norwegian group.

Figure 79-2 Progression of periodontal disease in an untreated population.

(Data from Löe H, Anerud A, Boysen H, et al: J Clin Periodontol 13:431, 1986.)

Figure 79-3 Loss of attachment in untreated Sri Lankan laborers.

(Data from Löe H, Anerud A, Boysen H, et al: J Clin Periodontol 13:431, 1986.)

In the previously discussed study of General Telephone workers in California, loss of attachment was measured clinically and alveolar bone loss measured radiographically.33,34 After 3 years, the control group showed loss of attachment at a rate more than 3 times that of the matching experimental group during the same period (Figure 79-4). In addition, subjects who received frequent oral prophylaxis and were instructed in good oral hygiene practices showed less bone loss radiographically after 3 years than did control subjects. It is clear that loss of attachment can be reduced by good oral hygiene and frequent dental prophylaxis.

Treatment of Loss of Attachment

A longitudinal study of patients with moderate-to-advanced periodontal disease conducted at the University of Michigan showed that the progression of periodontal disease can be stopped for 3 years postoperatively regardless of the modality of treatment.26-29 With long-term observations, the average loss of attachment was only 0.3 mm over 7 years.26 These results indicated a more favorable prognosis for treatment of advanced periodontal lesions than previously assumed.

Another study was conducted in 75 patients with advanced periodontal disease to determine the effect of plaque control and surgical pocket elimination on the establishment and maintenance of periodontal health.14 This study showed that no further alveolar bone loss occurred during the 5-year observation period. The meticulous plaque control practiced by the patients in this study was considered a major factor in the excellent results produced. After 14 years, results for 61 of the initial 75 individuals were reported.13 Repeated examinations demonstrated that treatment of advanced forms of periodontal disease resulted in clinically healthy periodontal conditions and that this state of health was maintained in most patients and sites during the 14-year period. A more detailed analysis of the data, however, revealed that a small number of sites in a few patients lost a substantial amount of attachment. Approximately 43 surfaces in 15 different patients were exposed to recurrent periodontal disease of significant magnitude. The frequency of sites that lost more than 2 mm of attachment during the 14 years of maintenance was 0.8% to 0.1% per year.

Neither of these studies used a control group because failing to treat advanced periodontal patients cannot be justified for ethical reasons. However, in a study in private practice, an effort was made to find and evaluate patients with diagnosed moderate-to-advanced periodontitis who had not followed through with recommended periodontal therapy.3 Thirty patients ranging in age from 25 to 71 years were evaluated after periods ranging from 18 to 115 months. All of these untreated patients had progressive increases in pocket depth and radiographic evidence of progressive bone resorption.

In a study of the progression of periodontal disease in the absence of therapy, two different populations were monitored.16 One group of 64 Swedish adults with mild-to-moderate periodontal disease and one group of 36 American adults with advanced destructive disease were monitored but not treated for 6 years and 1 year, respectively. During the course of 6 years, 11.6% of all sites in the Swedish population (1.9% per year) showed attachment loss of greater than 2 mm, and the corresponding figure for the American population was 3.2% per year. Thus the frequency of sites with disease progression was 20 to 30 times higher in untreated groups of patients than in the treated and well-maintained groups described in the preceding discussion.16 Thus treatment is effective in reducing loss of attachment.

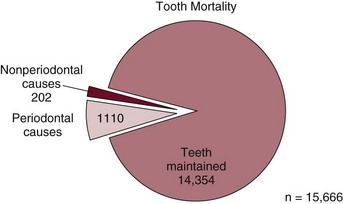

Tooth Mortality

The ultimate test for the effectiveness of periodontal treatment is whether the loss of teeth can be prevented. Sufficient studies from both private practice and research institutions are now available to document that loss of teeth is reduced or prevented by therapy.

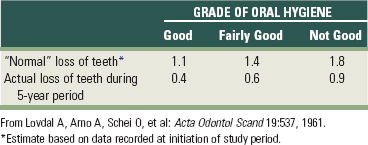

The combined effect of subgingival scaling every 3 to 6 months and controlled oral hygiene was evaluated over a 5-year period in 1428 factory workers in Oslo.20 Tooth loss was significantly reduced in all patients. This study showed that frequent subgingival scaling reduces tooth loss even when oral hygiene is “not good” (Table 79-1).

TABLE 79-1 Average Loss of Teeth during a 5-year Period Compared with Normal Loss of Teeth in 1428 Men and Women Ages 20 through 59

The previously mentioned longitudinal study conducted at the University of Michigan included 104 patients with a total of 2604 teeth.26-29After 1 to 7 years of treatment, 53 teeth were lost for various reasons (Table 79-2). Approximately 32 teeth were lost during the first and second years after initiation of treatment. The remaining 21 teeth were lost in a random pattern over the next 6 years. Therefore the loss of teeth caused by advanced periodontal disease after treatment was minimal (1.15%).

TABLE 79-2 Tooth Mortality after Treatment of Advanced Periodontitis in 104 Patients with 2604 Teeth Treated over a 10-Year Period

| Teeth Lost* | Reason |

|---|---|

| 2 | Pulpal disease |

| 3 | Accidents |

| 4 | Prosthetic considerations |

| 14 | Various reasons; for example, one patient wanted a maxillary denture for cosmetic reasons |

| 30 | Periodontal |

| 53 | All reasons |

* 2% of the teeth were lost during the study period. NOTE: United States health surveys conducted in the 1960s indicated that an average of 4.3 teeth were lost after age 35 in the general population.9

Data from Ramfjord SP, Knowles JW, Nissle RR, et al: J Periodontol 44:66, 1973.

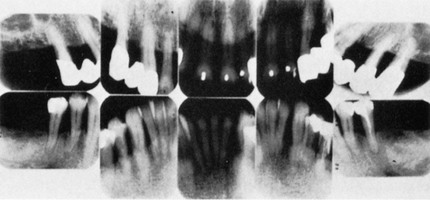

Another study was undertaken to test the effect of periodontal therapy in cases of advanced disease.14-15 The subjects were 75 patients who had lost 50% or more of their periodontal support (Figure 79-5). Treatment consisted of oral hygiene measures, scaling procedures, extraction of untreatable teeth, periodontal surgery, and prosthetic therapy if indicated. After completion of periodontal treatment, no patient showed further loss of periodontal support for the next 5 years. No teeth were extracted in the 5-year posttreatment period. Patients in this study were selected because of their capacity to meet high requirements of plaque control after repeated instruction in oral hygiene techniques; this fact does not detract from the validity of the study but tends to show the etiologic importance of bacterial plaque. The results indicate that periodontal surgery coupled with a detailed plaque control program not only temporarily cures the disease but also reduces further progression of periodontal breakdown, even in patients with severely reduced periodontal support.

Figure 79-5 Radiographs taken 5 years after typical periodontal treatment. Note the advanced bone loss, despite the teeth retained in a healthy condition for the duration of the study.

(From Lindhe J, Nyman S: J Clin Periodontol 2:67, 1975.)

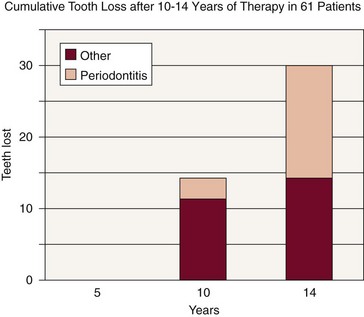

After 14 years, 61 of the original patients were still in the study.14 Recurrence of destructive periodontal disease in isolated sites of the dentition resulted in loss of a certain number of teeth during the observation period (Figure 79-6). In the 6 to 10 years after active therapy, one tooth in each of three different patients was lost, and during the final observation period (11 to 14 years), three teeth in one patient, two teeth in each of three patients, and one tooth in each of four patients had to be extracted because of recurrent periodontal disease. In addition, three teeth in each of three different patients and one tooth in each of five patients were extracted because of the development of extensive caries, periapical lesions, or other endodontic complications. During the entire course of the study, the total loss was 30 teeth (for all reasons) of 1330 teeth. The tooth mortality rate was therefore 2.3%.

Figure 79-6 Tooth loss in treated patients with very advanced periodontal disease.

(Data from Lindhe J, Nyman S: J Clin Periodontol 11:504, 1984.)

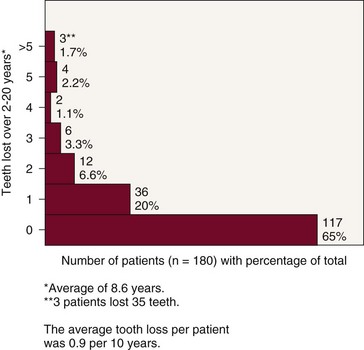

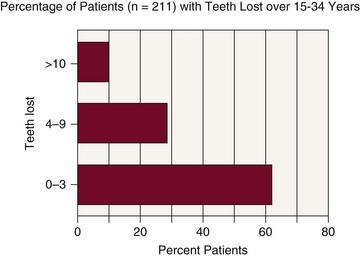

Several studies in private practice have attempted to measure frequency of tooth loss after periodontal therapy. In one study, 180 patients who had been treated for chronic destructive periodontal disease were evaluated.30-31 The average age of the patients before treatment was 43.7 years. A total of 141 teeth were lost. From the beginning of treatment to the time of the survey, the majority of patients lost no teeth (Figure 79-7). Three of 180 patients (1.7%) lost 35 teeth, approximately 25% of the teeth lost. Twelve additional patients lost 46 teeth, or 32.6% of the teeth lost. Many patients in the study had advanced alveolar bone loss, including extensive furcation involvements. However, only a relatively small number (141) of the teeth were lost in the study group of 180 patients between the beginning of periodontal treatment and the time of the study.

Figure 79-7 Tooth mortality. Average tooth loss per patient was 0.9 per 10 years.

(Modified from Ross IF, Thompson RH, Galdi M: Parodontologie 25:125, 1971.)

The teeth were lost for several reasons, including periodontal disease, caries, and other nonperiodontal causes. The length of time after treatment varied from 2 to 20 years, with an average of 8.6 years. Of considerable significance is the large number of teeth (81 teeth, or 57.5%) lost by a few patients (15 patients, or 8.4%). Even when this group is considered with the remaining 165 patients, the periodontal care helped to retain most teeth because the average tooth loss was slightly less than one tooth (0.9) over the 10 years after treatment.

In a follow-up study, the long-term results of periodontal therapy were evaluated after 15 to 34 years (average of 22.2 years).4 The average tooth loss at this time was 1.6 teeth per 10 years. Patients were classified into three groups according to tooth loss. Approximately 62% had an average tooth loss of 0.45 per 10 years and were considered “well maintained”; 28% lost an average of 2.6 teeth per 10 years and were considered “downhill”; and 10% lost an average of 6.4 teeth per 10 years and were considered “extreme downhill” (Figure 79-8).

Figure 79-8 Tooth mortality 15 to 34 years after initiation of therapy (average of 22.2 years). Average tooth loss per patient was 1.6 teeth per 10 years. Compare with the same study population in Figure 79-7. As the treated population ages, the rate of bone loss appears to increase.

(Modified from Goldman MJ, Ross IF, Goteiner D: J Periodontol 57:347, 1986.)

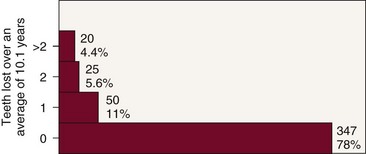

Another study included all patients in a practice who had been treated 5 or more years previously and had received regular preventive periodontal care since that time.25 The 442 patients had an average of 10.1 years since treatment. Two-thirds of the patients were older than 40 years of age at the time of treatment. These patients had been seen every 4.6 months, on average, for their preventive periodontal care, which consisted of oral hygiene instruction and prophylaxis (Figures 79-9 and 79-10).

Figure 79-9 Tooth mortality in 442 periodontal patients treated over 10 years.

(Courtesy Dr. R.C. Oliver, Rio Verde, AZ.)

Figure 79-10 Loss of teeth with advanced periodontal disease over 10 years.

(Courtesy Dr. R.C. Oliver, Rio Verde, AZ.)

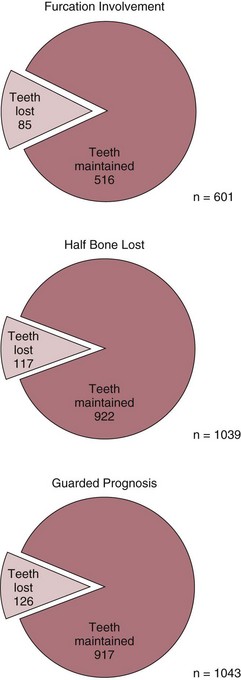

The total tooth loss resulting from periodontal disease was 178 of more than 11,000 teeth available for treatment. More important, 78% of the patients did not lose a single tooth after periodontal therapy, and 11% lost only one tooth. Considering that more than 600 teeth had furcation involvements at the time of the original treatment and that well over 1000 teeth had less than half the alveolar bone support remaining, the tooth loss was low. During the same average 10-year period after periodontal therapy, only 45 teeth were lost through caries or pulpal involvement. Even more surprising are the statistics over an average 10-year period for teeth with a less-than-optimal prognosis. Only 85 (14%) of a total of 601 teeth with furcation involvement were lost, and 117 (11%) of 1039 teeth with half or less of the bone remaining were lost. Of the 1043 teeth listed as having a “guarded prognosis” for any reason by the clinician performing the initial examination, only 126 (12%) were lost over this 10-year average period. The average tooth mortality rate was 0.72 tooth lost per patient per 10 years.

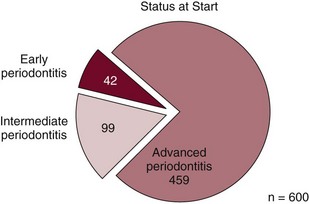

In a third study in private practice, 600 patients were followed for 15 to 53 years after periodontal therapy (Figures 79-11 and 79-12).7 The majority (76.5%) had advanced periodontal disease at the start of treatment. There were 15,666 teeth present, for an average of 26 teeth per patient. During the follow-up period (average of 22 years), a total of 1312 teeth were lost from all causes. Of this number, 1110 were lost for periodontal reasons. The average tooth mortality rate per patient was 2.2 teeth; when this is converted to a 10-year rate, an average of one tooth was lost per 10 years in each patient. During this period of observation, 666 teeth with a questionable prognosis were lost out of a total of 2141. This means that 31% of the teeth with a questionable prognosis were lost over 22 years of treatment. A total of 1464 teeth with furcation involvement were treated, and 31.6% were lost during the period of study. Approximately 83% of the patients lost fewer than 3 teeth over the 22-year average treatment period and were classified as “well maintained.” The remaining 17% of the patients were divided into two groups: “downhill” (4 to 9 teeth lost) or “extreme downhill” (10 to 23 teeth lost). Thus 17% of the patients studied accounted for 69% of the teeth lost from periodontal causes. This study also showed that relatively few teeth are lost after periodontal therapy. In addition, relatively few of the teeth with guarded prognosis, including those with furcation involvement, are lost, and a small percentage of patients lose most of the teeth.

Figure 79-11 Status at the start of a study of 600 patients.

(Data from Hirschfeld L, Wasserman B: J Periodontol 49:225, 1978.)

Figure 79-12 Loss of teeth in 600 patients over 15 to 53 years from nonperiodontal and periodontal causes.

(Data from Hirschfeld L, Wasserman B: J Periodontol 49:225, 1978.)

Three studies give insight into tooth mortality in untreated patients. The studies of Löe et al19 in Sri Lankan laborers showed that after age 35, an average of 5 and 16 teeth were lost per 10 years in the “moderate progression” and “rapid progression” groups, respectively (Figure 79-13). In a previously discussed study in private practice,3 an effort was made to find and evaluate patients with diagnosed moderate-to-advanced periodontitis who did not follow through with recommended periodontal therapy. Patients with untreated periodontal disease were losing teeth at a rate greater than 0.61 tooth per year (6.1 teeth per 10 years). A total of 83 teeth were lost in 30 patients, but the investigators excluded one patient who had lost 25 teeth. Including this patient would have increased the tooth loss in untreated patients to an even higher rate. In another study, reporting on patients with moderate-to-advanced periodontitis examined at the Department of Periodontology at the University of Kiel in Germany, Kocher et al10 found a marked increase in tooth loss in the untreated patients compared with the treated patients when they were examined after 7 years.

Figure 79-13 Tooth loss in a population with untreated periodontal disease.

(Data from Löe H, Anerud A, Boysen H, et al: J Clin Periodontol 13:431, 1986.)

When Tables 79-3 and 79-4 are compared, it is obvious that tooth mortality is much greater in untreated groups.

TABLE 79-3 Tooth Mortality in Treated Periodontitis Patients

| Study | Average Number of Teeth Lost per 10 Years with Periodontal Treatment* |

|---|---|

| Hirschfeld and Wasserman7 | 1.0 |

| Kocher et al10 | 1.6 |

| McFall20 | 1.4 |

| Oliver24 | 0.72 |

| Ross et al30 | 0.9 |

| Goldman et all4 | 1.6 |

| McLeod et al21 | 1.5 |

* Tooth mortality adjusted to 10 years by chapter author.

TABLE 79-4 Tooth Mortality in Untreated Periodontitis Patients

| Study | Average Number of Teeth Lost per 10 Years without Periodontal Treatment* |

|---|---|

| Becker et all3 | 6 |

| Kocher et al10 | 5 |

| Löe et al18 (moderate progression) | 5 |

| Löe et al18 (rapid progression) | 16 |

Summary

The prevalence of periodontal disease and the resulting high rate of tooth mortality have increased the need for effective treatment. Strong evidence now indicates that periodontal disease can contribute to numerous health problems, including pregnancy complications, heart disease, stroke, and diabetes.23,24,32,33 Available treatment is effective in preventing periodontal disease and stopping the progression of bone destruction after periodontitis is present. In addition, overwhelming evidence suggests that periodontal therapy greatly reduces tooth mortality. Every dental practitioner should be familiar with the philosophy and techniques of periodontal therapy. Failure to diagnose and treat periodontal disease or to make periodontal treatment available to patients causes unnecessary dental problems and tooth loss and places the patient at risk for systemic health problems.

![]() Science Transfer

Science Transfer

Gingivitis can be reversed by using initial therapy coupled with adequate plaque control techniques by the patient and subsequent maintenance visits every 4 to 6 months. Untreated periodontitis can cause rapid progression of attachment loss in approximately 8% of patients, resulting in tooth loss and significant active periodontal disease by the age of 45. Moderate progression occurs in approximately 81% of patients, but even these will have an average of 7 mm loss of attachment by age 45. A small percentage of patients (about 11%) show little, if any, progression of gingivitis to periodontitis. Clinicians should use this information to apply more aggressive treatment to those that are most susceptible.

Treatment of even advanced periodontally involved teeth with a combination of nonsurgical and surgical therapy with appropriate plaque control by the patient and maintenance visits every 3 or 4 months in the dental office is remarkably successful. Tooth loss can be expected to be between 1% to 3% over decades of management even with initial periodontal disease levels being very dramatic. Importantly, just a small subset of patients are responsible for much of the tooth loss in treated populations.

If the clinical team and the patient are committed to periodontal health, the overall prognosis for successful periodontal therapy is excellent, and during treatment planning, a more optimistic approach to therapy is generally the best.

The variation in patient response to treatment is related to compliance and to different host immune responses and presence of highly pathogenic anaerobic bacteria in the biofilms. New reliable diagnostic techniques are needed to identify any at-risk patients, and clinicians should be ready to apply new breakthroughs in the assessment of immune capability and presence and numbers of putative periodontal bacteria.

1 Axelsson P, Lindhe J. Effect of controlled oral hygiene procedures on caries and periodontal disease in adults: results after 6 years. J Clin Periodontol. 1981;18:239.

2 Bay I, Moller IJ. The effect of a sodium monofluorophosphate dentifrice on the gingiva. J Periodontal Res. 1968;3:103.

3 Becker W, Berg L, Becker EB. Untreated periodontal disease: a longitudinal study. J Periodontol. 1979;50:234.

4 Goldman MJ, Ross IF, Goteiner D. Effect of periodontal therapy on patients maintained for 15 years or longer. J Periodontol. 1986;57:347.

5 Greene JC. Periodontal disease in India: report of an epidemiological study. J Dent Res. 1960;39:302.

6 Greville TN. United States life tables by dentulous or edentulous condition, 1971, and 1957–58, Pub No (HRA) 75-1338. Washington, DC: US Department of Health, Education, and Welfare; 1974.

7 Hirschfeld L, Wasserman B. A long-term survey of tooth loss in 600 treated periodontal patients. J Periodontol. 1978;49:225.

8 Hoover DR, Lefkowitz W. Reduction of gingivitis by toothbrushing. J Periodontol. 1955;36:193.

9 Kelly JE, Van Kirk LEJr, Garst CC. Decayed, missing and filled teeth in adults: United States 1960–1962, PHS Pub No 1000, Series 11, No 23. Washington, DC: US Public Health Service; 1967.

10 Kocher T, Konig J, Dzierzon U, et al. Disease progression in periodontally treated and untreated patients: a retrospective study. J Clin Periodontol. 2000;27:866.

11 Konig J, Plagmann HC, Ruhling A, Kocher T. Tooth loss and pocket probing depths in compliant periodontally treated patients: a retrospective analysis. J Clin Periodontol. 2002;29:1092.

12 Ladavalya MR, Harris R. A study of the gingival and periodontal conditions of a group of people in Chieng Mai province. J Periodontol. 1959;30:219.

13 Lightner LM, O’Leary JT, Drake RB, et al. Preventive periodontic treatment procedures: results over 46 months. J Periodontol. 1971;42:555.

14 Lindhe J, Nyman S. The effect of plaque control and surgical pocket elimination on the establishment and maintenance of periodontal health: a longitudinal study of periodontal therapy in cases of advanced disease. J Clin Periodontol. 1975;2:67.

15 Lindhe J, Nyman S. Long-term maintenance of patients treated for advanced periodontal disease. J Clin Periodontol. 1984;11:504.

16 Lindhe J, Haffajee AD, Socransky SS. Progression of periodontal disease in adult subjects in the absence of periodontal therapy. J Clin Periodontol. 1983;10:433.

17 Löe H, Theilade E, Jensen SB. Experimental gingivitis in man. J Periodontol. 1965;36:177.

18 Löe H, Anerud A, Boysen H, et al. The natural history of periodontal disease in man. J Periodontol. 1978;49:607.

19 Löe H, Anerud A, Boysen H, et al. Natural history of periodontal disease in man. J Clin Periodontol. 1986;13:431.

20 Lovdal A, Arno A, Schei O, et al. Combined effect of subgingival scaling and controlled oral hygiene on the incidence of gingivitis. Acta Odontol Scand. 1961;19:537.

21 McFall WTJr. Tooth loss with and without periodontal therapy. Periodont Abstracts. 1969;17:8.

22 McLeod DE, Lainson PA, Spivey JD. The effectiveness of periodontal treatment as measured by tooth loss. J Am Dent Assoc. 1997;128:316.

23 Meskin LH. Focal infection: back with a bang!. J Am Dent Assoc. 1998;129:8.

24 Offenbacher S, Lieff S, Beck JD. Periodontitis-associated pregnancy complications. Pregnancy Neonat Med. 1988;3:82.

25 Oliver RC: Personal communication, 1977.

26 Ramfjord SP, Nissle RR. The modified Widman flap. J Periodontol. 1974;45:601.

27 Ramfjord SP, Knowles JW, Nissle RR, et al. Longitudinal study of periodontal therapy. J Periodontol. 1973;44:66.

28 Ramfjord SP, Knowles JW, Nissle RR, et al. Results following three modalities of periodontal therapy. J Periodontol. 1975;46:522.

29 Ramfjord SP, Nissle RR, Shick RA, et al. Subgingival curettage versus surgical elimination of periodontal pockets. J Periodontol. 1968;39:167.

30 Ross IF, Thompson RH. A long-term study of root retention in the treatment of maxillary molars with furcation involvement. J Periodontol. 1978;49:238.

31 Ross IF, Thompson RH, Galdi M. The results of treatment: a long-term study of one hundred and eighty patients. Parodontologie. 1971;25:125.

32 Slavkin HC. Does the mouth put the heart at risk? J Am Dent Assoc. 1999;130:109.

33 Stamm JW. Proceedings of the Sunstar-Chapel Hill Symposium 1997 on Periodontal Diseases and Human Health: New directions in periodontal medicine. Ann Periodontol. 1998;3:1.

34 Suomi JD, Greene JC, Vermillion JR, et al. The effect of controlled oral hygiene on the progression of periodontal disease in adults: results after the third and final year. J Periodontol. 1971;42:152.

35 Suomi JD, West JD, Chang JJ, et al. The effect of controlled oral hygiene procedures on the progression of periodontal disease in adults: radiographic findings. J Periodontol. 1971;42:152.

36 Theilade E, Wright WH, Jensen SB, et al. Experimental gingivitis in man. II. J Periodontal Res. 1966;1:1.