CHAPTER 85 Dental Insurance and Managed Care in Periodontal Practice

History

Health Insurance

Health insurance emerged in the United States (US) as the country was emerging from the great depression in the 1930s. Most of the original “insurance” programs were offered by hospital systems or groups of physicians and included diagnostic and radiographic services, as well as “room and board” while patients were hospitalized. Insurance plans did not have great penetration in the US until World War II.

World War II created a huge demand for labor in the US. The labor force was significantly reduced by the Armed Forces as the US fought the war. The posters of “Rosie the Riveter” were produced during this period as women moved into the wartime production economy to fulfill the needs for war materials in a depleted labor market. At the same time, the US had frozen wartime wages and prices. This wage freeze was put in place to prevent individuals or groups from leveraging the shortage of goods and labor for personal gain, thereby hurting the wartime production efforts.

To compete for labor in these wage-restricted markets, employers began to offer “nonwage” compensation, and health insurance was a popular “total compensation” enticement to work for an employer. The effects of this “employment-based” health insurance system are still in place today, although its relevance to the current economy and health systems is increasingly debated.

Some progressive employers in World War II even opened their own clinics. This was seen as useful from a number of perspectives. In some cases, workers did not need to leave their workplace to receive medical services, thereby reducing the amount of time lost from production. The cost of the health system was also under the direct control of the employer. The Kaiser Health system of today is the evolutionary prodigy of Henry Kaiser’s vision for the health care of the individuals employed in his shipyards.

Dental Insurance

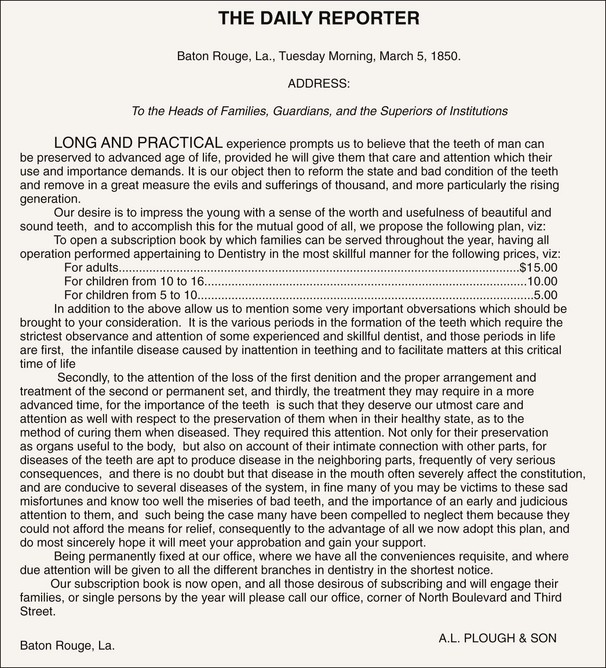

Dental insurance has existed in one form or another for a substantial time. Figure 85-1 shows a proposal for a dental capitation plan from 1850.

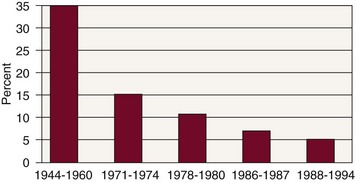

Formally, dental insurance in the US began in 1954 as collaboration between the International Longshoreman and Warehouse Union (ILWU) and the three state dental associations on the West coast. The ILWU suggested to the Washington, Oregon and California State Dental Associations that they help design a program for the ILWU’s children or following the World War II Kaiser example, the ILWU would open its own clinics.2 At the time of this collaboration, dental care was considered uninsurable. Caries and periodontal diseases were pandemic, and edentulism was an expected outcome by the time individuals reached middle age3 (Figures 85-2 and 85-3). Life expectancy at birth was 60 years.5 Against this backdrop, three dental service corporations were formed in Washington, Oregon, and California within several months of each other.

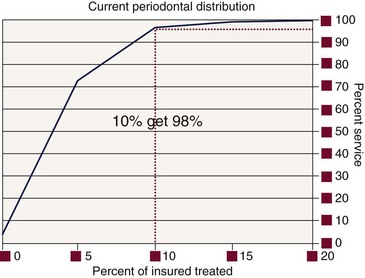

Figure 85-2 Decreasing incidence of caries in molar teeth. The probability that an erupting molar tooth would be restored in the year after eruption.

Figure 85-3 Penetration by age of gingivitis, periodontal disease, and tooth loss as recorded in 1950.

(From Marshall-Day CD: J Periodontal Res 22:13, 1951.)

There is some debate as to whether dental benefits coverage is insurance or prepaid health care. Typically, insurance covers large costs for events that occur infrequently (e.g., fire insurance, automobile insurance). However, dental needs across large populations are uniform, and the costs are relatively small compared with medical costs. The argument is actually one of perspective. For the purchaser of dental services from a third-party payer, dental insurance is prepaid health care. The carrier or the purchaser assumes the risk. The underwriting costs of dental care are very well known. In fact, an employer with more than about 1000 employees will probably be “self-insured.” That is, the employer will pay the benefits costs while paying a third party to adjudicate the claims and manage the records. The employer assumes the risk, but actuaries have determined, with great precision, what their costs will be for the year. From the patient’s perspective, dental coverage spreads the risk of incurring disease and its repair across a population and thus acts as insurance.

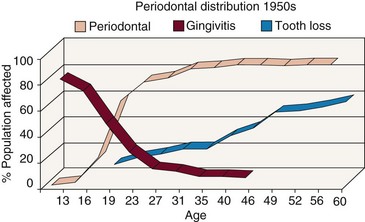

Given the high incidence and prevalence of dentistry’s two primary diseases in the 1950s, dental insurance plans were written to treat the entire population. At present, neither dental caries nor periodontal diseases are pandemic, at least in populations covered by commercial insurance. Using national data from both the second National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES II study)4 and dental insurance records5 (Figure 85-4), it is clear that these diseases are sequestered in an increasingly smaller number of individuals. The penetration of both diseases has been declining for the past 50 years. This uneven distribution of disease makes dentistry much more like risk insurance than when everyone had dental diseases.1

Principles

In principle when analyzing insurance by who assumes the payment risk, there are only three major ways to provide dental benefits. In traditional risk insurance, the dental insurance entity assumes the risk and potential gains or losses from revenue spent or not spent on treatment. This is the traditional view of “dental insurance.” A less- [variation of the] traditional type of “risk insurance” is capitation or prepaid care (DHMO), in which the dentist is paid a fixed amount per enrolled patient to provide a contractually specified level of treatment. In this model the dentist assumes the risk.

The third type of dental payment is aptly called an administrative services contract (ASC). Employers, generally with 1000 or more employees, are self-insured and pay third-party administrators, dental services corporations, or insurance companies to provide program management services. Employers have found that the administrative services contractor has more expertise in this domain and can perform these services better, faster, and cheaper than the purchaser can self-administer these functions. These services generally include all the record keeping (administration) and adjudicative practices (rules enforcement and professional determinations of the extent of benefits), but there is no potential for a gain or loss on the dental claims for the administrative company. For example, regardless of whether a specific claim for services is approved or denied by the ASC contractor, there is no impact on its revenues. It is paid a flat administrative rate to manage these activities for the self-insured business.

Within these three general insurance funding types, there are numerous administrative strategies. These include full-service programs in which the administrative entity provides all the services necessary to manage a dental plan. This involves suggesting and developing plan designs, writing the services contracts, receiving and keeping eligibility data, recruiting dentist networks, credentialing the dentists, and receiving, adjudicating, and paying claims for services. There are variations on this theme, with a “ratcheting back” of services until direct reimbursement is the remaining service. In the most basic form of direct reimbursement, the administrator manages only eligibility information, bookkeeping, and payment of submitted claims. No professional review services are rendered (see later discussion).

It should be noted that the purchasers of health care services make the final decisions about what they will and will not put in their benefits plans. Dental insurance companies advise purchasers about the costs of individual benefits, but ultimately this is the purchaser’s decision. That decision may be determined by labor contracts because dental benefits are often negotiated benefits. In these cases the union(s) also has a voice in the benefits design. This is a complex process that is not simply a coverage choice for the insurance company, the purchaser, or the represented groups.

Classification of Programs

Dental payment programs may be classified in several different ways. Traditionally, they have been classified by who assumes the risk for loss. As discussed previously, the insurance company may assume the risk, and this is often referred to as an “indemnity” plan. When the dentist assumes the risk, the plan is generally called a capitation or dental health maintenance organization (DHMO) plan. Finally, when the employer assumes the risk, the plan is an “administrative services” or a “self-insured” plan.

In most of these types of plan designs, there is a system of checks to ensure that appropriate services are being rendered. Although no validated data exist to support the figures, some have estimated that in the US, approximately 7% to 10% of health care expenses are fraudulently claimed.6 With a $2.4 trillion annual expenditure on health care, this means that at the high end, $240 billion would be fraudulently expended. With these staggering numbers, purchasers of health care services want external validation that services have been rendered and that the services rendered were consistent with the benefits they desire to provide. There is no evidence that the rate of fraud in dentistry is in this percentage range or that the incentives are equivalent. Most dental plans have annual maximums and patient co-insurance that do not permit extensive fraud. However, the dental industry is still part of the health care industry and is held to the same review principles.

Indemnity plans allow the patient to seek care from any general dentist or specialist of his or her choice. There is no contractual relation between the dentist and the third party. The plan provides benefits for covered services based on the plan’s determination of some maximum plan allowance for a procedure or on a fee schedule (“table of allowances”). The patient is responsible for any balance beyond the benefit provided by the plan. Almost all of these plans have a yearly or lifetime deductible and maximum payments for specific procedures and involve payment by the patient of a percentage (co-insurance) of the fee. That percentage varies with the type of treatment provided. For example, Class I treatment is generally diagnostic and preventive services and often has no required co-insurance contribution. Class II services (e.g., basic restorative, endodontics, periodontics, or extractions) usually involve a patient payment of 20%. Fixed and removable prosthetics and major restorative procedures such as crowns typically are classified as Class III, with 50% co-insurance. Periodontal surgery, although most often considered a Class II expense, is categorized as type III by some plans.

Other plans offer a contractual relationship between the dentist and the plan. They may involve a capitation (prepaid) plan, preferred provider organization (PPO), individual practice association (IPA), service corporation, or discount plan. These plans may be further classified by access to dentists. In a point-of-service plan (POS), patients may see any dentist. The insurance plan may or may not pay a higher portion of the bill for a patient seeing dentists who have joined their network. If the plan pays more of the bill (and the patient less) when a patient sees a network dentist, the plan is called a PPO. POS plans also include programs in which the patient has a “schedule of allowances.” In this case, the plan pays any dentist the amount listed on the schedule. Members agree by contract to accept the allowance as their fee subject to the Class system described above. If the dentist is not a member of the network (also called a “nonparticipating” dentist), the patient will be responsible for any additional fee the dentist requires.

Direct reimbursement (DR) is another type of POS program. In this strategy, the employer sets aside a sum of money for each employee and patients see the dentist of their choice, make payments directly to the dentist, and receive a statement demonstrating those payments. The plan then reimburses patients up to the limits of the plan. In this particular case, there is no review of treatment for appropriateness or even whether any particular service was actually rendered. This plan is attractive to many dentists and some employers. However, most major purchasers of health services desire external review.

When payment is restricted to only network dentists, the plan is termed an exclusive provider organization (EPO). If a patient chooses to see a dentist outside the network of dentists, the plan pays nothing and the patient is responsible for all fees. Most capitation plans fall into this category, with some exceptions for specialty care.

In a prepaid DHMO or capitation plan, the contracting dentist is paid a set fee each month for each enrolled patient, regardless of whether the patient has received any treatment. The dentist agrees to provide all needed covered services with no patient payment except for specified co-payments for specified, usually more expensive, treatment such as periodontal surgery and crowns and bridges. Although the contracting dentist usually is responsible for nonsurgical periodontal care, periodontal surgery typically is referred to a specialist, who is reimbursed according to a fee schedule. If the periodontist has contracted with the plan, the patient has no financial responsibility beyond a co-payment. If the specialist has not contracted with the plan, the patient is responsible for the difference between the plan payment and the dentist’s fee. Payment for non-covered services is the patient’s responsibility. The dentist assumes the financial risk, so if the capitation fee, co-payments, and patient payment for services are not sufficient to cover the cost of treatment, the dentist, not the insurance company or the employer, is responsible for that difference. Conversely, if the patient uses fewer resources than the capitated amount, the dentist gains the difference.

There are different economic incentives and potential deterrents for dental offices to join panels, groups, or networks. With the PPO the reimbursement may be discounted from the dentist’s usual fees. If there is a discount, the plan is referred to as a “fee-discounted PPO.” The advantage of belonging to a PPO is the increased access to patients for the dental office. The increase in patients is driven by the listing of the dentist in a directory of dentists available to patients and by the patient’s economic incentive to see a network dentist because the plan pays a greater portion of the bill. If a dentist needs additional patients in the practice, this may be an attractive program depending on the reimbursement offered or allowed by the insurance entity. However, the additional income generated by an increased patient load must be counterbalanced by the increased expenses incurred for supplies and materials (see later discussion on how to make this economic decision).

Participation in any dental program is a personal decision for each dentist, but before signing any contract, the dentist should obtain competent legal advice. The dentist also should read the contract carefully to be aware of the obligations he or she is incurring. It never is sufficient to look only at the fee schedule to determine if participation in a particular plan will be beneficial.

Government-funded programs in the US, such as Medicaid and Medicare, provide limited coverage for dental care. Medicaid is a joint federal-state program. Benefits are determined by the states and vary greatly among them. In some cases, benefits may be limited to restorations and extractions for children. Medicare is the federally sponsored program under the Social Security Act and does not cover most routine dental services. In fact, it specifically excludes “services in conjunction with the care, treatment, filling, removal of teeth or structures directly supporting teeth.” There are some limited benefits for treatment related to trauma or tumors.

![]() Science Transfer

Science Transfer

The reality of treating periodontal problems in the 21st century is that clinicians need to have expertise in managing a variety of reimbursement mechanisms that control payments and treatment options. These mechanisms are constantly changing and are different for each practice locale. Clinicians must make patients aware of all treatment possibilities and make therapeutic recommendations centered on the patient’s specific needs and not solely on the available insurance coverage. This will give each patient a reliable basis to consent to any given treatment plan and broaden the availability of high quality periodontal care.

Benefits Design

Time Limits

Time limits are imposed on various procedures to control costs by holding the dentist responsible for his or her work for a finite period of time or in some cases to permit a reevaluation period. An example is the 2-year limitation on amalgam or resin restorations. Most plans will not pay for the replacement of a restoration placed within the preceding 24 months if the plan paid for the original restoration.

In periodontics, these limitations are imposed on surgical and nonsurgical services. Often, a plan will not pay for a second surgery of the same type in the same site for 2 or 3 years. Some carriers interpret this so that benefits are provided for osseous surgery, but not for the bone grafts or guided tissue regeneration to repair or regenerate defects. Benefit frequencies for scaling and root planing are also limited in most plans. Many of these time limitations have not been based on scientific evidence or individual patient risk profiles in the past. Whether they will be based on such evidence and the emerging “personalized health care” principles in the future remains to be seen.

A separate example of time limitations is applicable to site-specific therapies in treating localized periodontal defects. Some carriers will not benefit the application of locally applied antibiotics, whereas others cover them with little or no restrictions. Others will provide a benefit only after a finite healing period has elapsed following scaling and root planing or periodontal surgery, and then the plan will only reimburse for application to residual pockets that show signs of active disease. The rationale is to allow a healing response to occur, thereby reducing the number of sites that need to be treated. This limitation is not validated (i.e., neither supported or refuted) by evidence because most studies for the current, locally delivered antibiotics have involved placement at the time of scaling and root planing and not after a healing period.

Balance Billing

Balance billing is a term used to describe how fee differences between a plan’s allowance and a dentist’s fees are handled. Depending on the dentist’s relationship with the plan, the dentist may be unable to bill the patient for the fee difference.

Dentists who join a dental plan’s group and who have their name listed in the directory and receive patients from among the plan’s subscribers may be limited in their right to bill the patient for fee differences between their usual fees and those permitted by the plan. The dentist is trading this fee limitation for the additional patients received. This may or may not make economic sense. Determining whether it makes good business sense is quite simple but does require a careful analysis of treatment provided, the expenses incurred and the remuneration received. Using the general equation provided below establishes whether this is an acceptable dental plan for any specific office.

First, an office needs to examine its mix of services. For a periodontal office, the mix of time spent in providing nonsurgical therapies, surgical services, and implant services needs to be calculated for a routine three-month period. The results should be designed to show the percentage of time spent in each of the major areas of practice, and each area should include the associated case-planning and presentation times.

Using this percentage mix of services delivered, the dentist should examine their fee schedule to determine the average hourly gross income for the office. Using the same percentages and the dental plan’s schedule of maximum fees or its preapproved fee allowance, the office should calculate the cash flow that will be generated by the plan’s subscribers.

It is important to measure these numbers as “dollars/ hour of production” and not the total day’s hours because unutilized chair time is costly to an office and may warrant participating in a plan to cover overhead, even with a reduced profit margin.

With the previous information, the following general equation applies:

For the purposes of this chapter, “office overhead” represents the fixed costs of running the office, including heat, lights, rent, computers, insurance, and staff salaries. “Additional expenses” are the variable costs associated with treating more patients and the mix of services they receive.

If this equation yields a number greater than 1, the plan’s payments are at an acceptable level for the dentist.

If the number is less than 1, the dentist must determine whether to modify the desired profit. If the dentist has unwanted empty chair time, the calculation should be used to determine if the plan’s allowable fees will cover the dentist’s overhead and additional expenses.

More complex formulas exist to perform these calculations, but the underlying principles remain the same.

The dentist should do more than determine if the additional income is adequate. The contract itself must be analyzed to determine that all obligations imposed are acceptable to the dentist. Advice should be obtained from advisors who are familiar with dental benefits contracts.

Coordination of Benefits

When patients have access to more than one source of dental insurance, the insurance benefits are coordinated (generally by state law) to determine which plan pays first. Most states follow the lead of the National Association of Insurance Commissioners (NAIC) in setting up the rules for how the benefits are paid. It is important to know that in most cases, neither the insurance company nor the purchaser of the health care benefit controls these rules. It is also important to know what the rules are in your state.

In general, when the patient has dental coverage, his or her policy is primary (pays first). If the patient is covered as a dependent under two or more policies, the policyholder whose birthday is earlier in the year usually is considered primary. In most cases the secondary carrier will make a supplemental payment only to bring total benefits up the amount it would have paid had it been primary.

Lack of coordination of benefits information on a claim is the second most common claim problem encountered by dental insurance companies. If you know that there is only one form of coverage, make a note on the dental claim that there is no other coverage. Even if the patient is the policyholder, omitting this information may delay a claim because the insurance plan needs this information to determine the level of payment to make in a given situation.

There are a number of nuances in how plans will pay, within the state’s rules for payment. It is important to know this information so that it can be discussed with the patient. An easy way to accomplish this with a new plan or when the situation is unclear is to submit an “estimate of benefits.” This will allow both the dental office and the patient to review the insurance company’s pre-estimates before financial commitments are made.

A caution regarding pre-estimations in general is that they are issued based on the claims that have been paid on the date of the pre-estimation. If other claims are being processed but have not been paid, or if additional treatment is received before the claim for actual services is processed, a plan’s maximum may be exceeded by the time a claim for the pre-estimated treatment is actually received. The only rational solution to this dilemma is to work closely with patients to determine whether they have recently received or are planning to receive other services and if so, the amount of those services. Pre-estimations also may not be valid if the insured individual no longer is covered because of job change or change in carrier.

As health care costs continue to escalate, an increasing number of purchasers choose variations on coordination of benefits. For example, when both members of a spousal pair are employed by the same employer, the employer may choose to provide coverage to only the employee and not provide secondary coverage from the other spouse’s insurance. This is called “nonduplication” of benefits. Alternatively, an employer may choose to provide coverage for only the individual employee. Any additional coverage for a spouse or children is elective, and the employee will pay all or a portion of the additional costs. This listing is not all-inclusive and should be used only as a cautionary guide.

Alternate Benefits

When several treatments can be used to treat a given situation, plans may choose to pay for the least expensive, professionally acceptable treatment. Dentists and their patients are free to choose the therapy that they want, but the plan will limit payment to the lower-cost procedure. The dentist and the patient must then determine how to settle the cost difference between the two procedures.

A straightforward example is a plan paying for an amalgam restoration in a posterior tooth. If the dentist and patient choose to restore the tooth with a resin-based restorative material, the plan will pay for the equivalent amalgam restoration. Because posterior resin restorations are more labor and procedure intensive, the dentist will typically charge one-third to half more for an equivalent resin restoration. The payment of the additional fee is the patient’s responsibility. Coverage for implants also may be affected by this contract provision. Although the dentist and patient may agree that replacement of a missing tooth with an implant is appropriate, the plan may determine that it could be replaced by a removable partial denture. In these cases the plan may provide a benefit to the restorative dentist equal to that for a removable partial denture but no benefit for placement of the implant. In some cases, however, benefits will be provided only for the treatment provided so the patient would not receive any reimbursement.

Exclusions

Purchasers of dental benefits may exclude certain procedures or classes of procedures as a mechanism for containing costs. For example, a purchaser may choose to exclude orthodontic treatment from its coverage or limit it to children under age 19 years. This represents a whole service category that is not covered by the plan.

Purchasers could also choose to limit how they will pay for the restoration of a bounded edentulous space. They may cover a three-unit bridge or a removable partial denture and not an implant. Alternatively, they may cover either the bridge or the implant but exclude preprosthetic procedures (e.g., sinus lift surgery).

Exclusions are generally considered totally outside the insurance plan and not limited by the plan. However, this statement requires a word of caution, particularly as it relates to implants. A number of plans will not pay for the placement of an implant (it is clearly excluded in the contract language), whereas the restoration of the implant may receive coverage at the standard rate for a crown. Although in this case the clinician placing the implant must be remunerated for those services outside the insurance plan, the patient should be advised to check with the plan to see if the prosthesis that will be placed on the implant is a covered benefit. Some contracts specify that payment for “noncovered” services (as distinct from excluded benefits) is determined by the carrier. This may occur even though that amount may not have been negotiated and, in some cases, is not made known to the patient or dentist before submission of a claim. In these cases, pre-estimation of benefits is in everyone’s best interest.

Adjudication

Adjudication means “acting as a judge or referee.” This is a function performed by a dental benefits carrier for the purchaser of health care services. The purchaser wants to ensure that needed and appropriate services for their employees are benefited and that the third-party payer has the expertise to provide this service. This can be an area of conflict between the periodontal office and the carrier in that differences of opinion can exist regarding whether a specific case meets the contract requirement for specific services. Most dental benefit plans “provide coverage for services and supplies that are determined [by the carrier] to be necessary for the diagnosis, care, or treatment of the condition involved.” Because few, if any, dentists provide services they do not believe are necessary for the diagnosis, care, or treatment of the condition involved, there can be a difference of opinion between the dentist and the payer’s dental consultant.

Differences of opinion occur for a number of reasons, but the most common reason is a lack of salient information being transferred between the dental office and the insuring entity. The key to obtaining coverage, within the scope of the purchased benefits, is providing the claims reviewer with enough information so that the person can make an informed decision. When information is lacking, the person adjudicating the claim is compelled to deny the service because the contract with the purchaser defines the reviewer’s duties and responsibilities in this area. It would be a violation of the contract between the insurance entity and the purchaser to pay for services that do not meet the conditions of the contract. Carriers are audited regularly by plan purchasers and must refund moneys paid inappropriately.

To overcome this problem, the submitting dental office should provide enough information so that a person with similar training would be able to make the same treatment decision as the dental office. This can be in the form of a narrative or attachments. The narrative should be clinically descriptive rather than the expression of an opinion. The submitter should briefly describe the clinical condition in sufficient detail to allow a person who is not seeing the patient to make an informed decision about the service the clinician is performing or wants to perform. In most cases it is not necessary to describe the procedure in detail; dental consultants know what is done.

Attachments

Attachments such as periodontal charts, radiographs, and narratives are a useful way to augment the information on a claim. They can be submitted along with a paper claim or electronically. Electronic claims have limitations on the length of a narrative, so attachments can be provided either by mailing them to the insurance company or by providing them by electronic means. Some insurance companies are set up to receive electronic attachments directly; however, many do not have this capability.

To fill this electronic business need, a number of companies have entered the business of receiving electronic dental attachments and storing them for use by any insurance company or other professional. In general with these services, the dental office uses its direct digital images (e.g., digital radiographs, electronic periodontal charts) or converts existing documents (e.g., periodontal charts, radiographs) into a digital format. This format can usually be any of the standard formats that scanners or digital devices output. That digital information is transmitted via the Internet to the electronic attachment company using its software. In some cases these images have been integrated into electronic dental records so that only one data entry is required. When the electronic attachment company receives the image, it immediately transmits a randomized unique identification code for that image(s) back to the dental office. The dental office then puts that unique code into the “Comments” box on the claim form and transmits it to the dental benefits company. Because the code is randomized and unique to the specific digital information transmitted from the dental office to the online storage facility, the carrier uses that code to view only that attachment. The images are available for a preset amount of time, often up to 3 years, so appeals and submissions for subsequent treatment or decision appeals do not require added transmissions.

The cost of these services varies slightly, but for periodontal offices, they may represent a significant cost reduction mechanism. These stored images are available to the insurance company and can be used to share patient information with a referring dentist, thereby saving time, handling, and other costs associated with moving information back and forth. It also eliminates the potential for lost records.

Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act

The Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act of 1996 (HIPAA) required the US Department of Health and Human Services to adopt national standards for electronic submission of all electronic administrative and financial health care transactions. Dentists and all other health care providers who submit claims electronically either directly or through a billing service (clearinghouse) are considered covered entities and must comply with all HIPAA provisions. The law requires payers to accept and health care providers to submit all electronic claims in the standard format, but it does not require dentists to submit all (or any) claims electronically. Third parties still must accept paper claims. Because paper claims are substantially more expensive to manage for the benefits companies (as well as for dental offices), it is likely that they will charge a premium for them in the future. In other words, if the dental office chooses to submit paper claims, it will be charged for the increased transaction costs. It is unclear when this will occur, but it is being considered.

Most Common Errors

The three most common submission errors that dental offices make when submitting claims to third-party payment systems are as follows:

If these elements are double-checked by the office staff before submission, approximately 50% of all errors will be eliminated.

Third-party carriers also make errors, although electronic submission of claims lowers third-party error rates because the data entry function occurs in the dental office. The most common third-party errors are as follows:

Conclusion

Dental benefits are part of many patients’ payment strategies for dental services. Therefore it is useful to understand the nature of dental insurance, why purchasers of benefits provide insurance for their employees, and how insurance is changing as the incidence, prevalence, and penetration of diseases change. These areas will continue to change as we learn more about treating the primary diseases of dentistry.

As in medicine, more individualized health plans, based on a patient’s risk profile and the best currently available evidence will begin to emerge in dental plans. These risk calculations will take a number of forms and will evolve over time so that in the future, patients at higher risk for either caries or periodontal diseases will have increased access to proven preventive or interceptive techniques.

It is the responsibility of the treating dentist to provide the information on the best available therapies for patients regardless of the limitations of the patient’s insurance. It is important always to remember that the dentist is treating the patient, not the insurance policy. Armed with this information, the patient and the dentist can reach an individual decision about treatment. It is also in the patient’s best interest for a dental office to submit a pre-estimation of benefits for more expensive and nonroutine treatments. In this way, the office is helping the patient maximize the use of available benefits and is not making assumptions that may limit this opportunity.

1 Anderson MH, del Augila M: Treatment distribution in an insured population, 1998 (Unpublished study of insurance data).

2 Goodman BF: Personal communication, 2000.

3 Marshall-Day CD. The epidemiology of periodontal disease. J Periodontal Res. 1951;22:13.

4 National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS). Second National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (Nhanes II). Hyattsville, MD: NCHS; 1996.

5 National Center for Health Statistics. Life expectancy at birth and at 65 years of age by sex and race, 1900-2000. http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/fastats/lifexpec.htm, 2005.

6 National Health Care Fraud Association. Health care fraud: a serious and costly reality for all Americans. http://www.nhcaa.org/pdf/all_about_hcf.pdf, 2005.