Becoming a Better Student

On completion of this chapter, you should be able to:

• Identify the needs common to all individuals.

• Describe physiologic needs and their effect on learning.

• Describe the way you perceive the world and your unique pattern of behavior for satisfying your needs.

• Examine your lifestyle to identify causes of stress and conflict.

• Examine your values and determine what is and what is not important to you.

• Describe ways in which conflict may be resolved.

• Increase your skills in memory and recall.

• Explain how perception is influenced by your memory of sights, sounds, and events.

• Improve your listening skills and reading effectiveness.

• Examine inaccurate memory and distortions in remembering and explain the theories for why these inaccuracies occur.

Choosing a vocation is an explicit statement about the kind of person you are or hope to be. Professional satisfaction will depend on the extent to which you can use your abilities in a productive manner. Your work should be consistent with your values and interests and the roles you fulfill in society. Choosing radiologic technology is an exploration. Education in radiologic technology is vastly different from the learning acquired in high school or a liberal arts college; the main difference is that your curriculum will require you to spend much of your time in the clinical setting, where you will learn how to manage sick and injured patients. Because patient care is the focus of your curriculum, generally the code of conduct is more rigidly defined and is based on the moral and ethical standards associated with the medical profession. You should expect and understand these differences to avoid future frustration or disappointment.

All students experience some frustration, anxiety, and perhaps a degree of disillusionment in preparing for their careers. Fortunately, most students adjust to these irritants with only minor strain. This chapter is provided to help you cope with the rigors of your educational program by learning about yourself and learning how to learn.

Knowing your human needs

Knowing yourself is the most important information you can possess at the beginning of your education. You have your own unique pattern of solving problems and your own values, ambitions, aspirations, and experiences in addition to the basic needs common to everyone; these qualities make up your unique personality. Indeed, personality is a combination of habitual patterns and qualities of behavior and attitudes. You think, feel, and act according to your perceptions of the world. You are a seeker, and your thoughts, feelings, and actions are purposefully directed toward satisfying your needs.

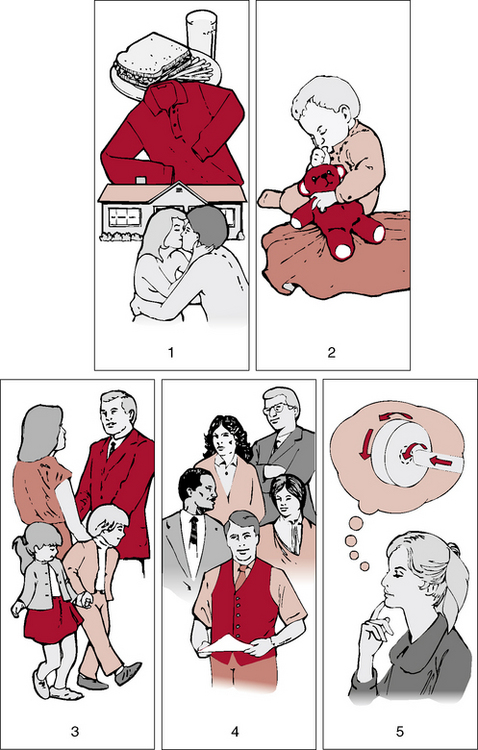

Human needs are complex. Some are unique to the individual, and others are common to everyone. Abraham H. Maslow, a noted psychologist, described a hierarchy of human needs that ranges from basic needs that are essential to life (e.g., food, clothing, shelter) to the highly complex, psychologic, and self-actualization needs (Fig. 2-1). Maslow’s hierarchy of needs is listed in the following order:

FIGURE 2-1 Maslow’s hierarchy of needs: (1) food, clothing, shelter, and the will to reproduce; (2) a feeling of safety; (3) love; (4) satisfying relationships; and (5) creativity, self-expression, and achievement.

First Level

Needs that are essential to life are first in the order of importance. These needs are food, clothing, shelter, and the will to reproduce.

Second Level

A feeling of safety is essential to growing and developing. You can never be completely safe from physical injury or disease. Feeling a degree of safety in your social and physical environment, however, is important.

Third Level

The need to be loved is inherent. You need the emotional support of others and the warmth and closeness of those important to you. This need also includes the desire to love others, to return affection, and to support and care for those who love you.

Fourth Level

You also need satisfying relationships with others in the larger social community. You need to be valued, accepted, and appreciated to maintain self-esteem, self-respect, and a unique identity.

Fifth Level

Creativity, self-expression, and achievement are also needs characteristic of all human beings. Work needs to be useful, productive, and valuable to others.

The higher-level needs are not felt until the first-level needs are satisfied. For example, a drowning man gasping for air does not feel the need to be creative at that moment. A person with extreme hunger and thirst feels the need for love and affection less than the more immediate and urgent need for sustenance. Physical needs must be met before creativity and other higher-level needs are felt.

Physiologic needs

Optimal health and well-being require attention to nutrition, sleep, relaxation, and exercise. To expect optimal learning performance, you must take optimal care of your body.

Nutrition

Diet, nutrition, and learning are tightly interwoven. Learning is easier with a sound body, and a sound body can help produce a sound mind. Nutritional biochemicals keep body cells healthy and functioning, and these biochemicals come from only one source—what you eat. Improper diet can also result in unexplained emotional upsets such as crying, depression, and even violent impulses.

Sleep

Your body also requires adequate sleep, which offers rest to the brain and nervous system. In preparing for your career, you want to be relaxed and well rested when you enter the classroom and laboratory so that you and your body can easily meet the demands placed on you. Both sleep and adequate diet are crucial to the learning process.

Recreation and Exercise

Recreation and exercise are important for both the mind and the body. Use of the mind can tire an individual. The mind functions better when mental concentration alternates with periods of diversion and exercise. Proper diet, rest, and recreation are valuable ways to practice personal preventive health care and are essential tools for creating optimal learning conditions.

Psychologic needs

Psychologic care involves developing and maintaining a healthy balance between rational thoughts and emotions. Although your studies will require a great deal of self-discipline, maintaining healthy social interactions with family and friends and accepting your emotions as a natural part of your personality are also important.

Emotionality

Emotionality is the quality or state of a sound emotional balance. Living by values based on a healthy balance between mind and heart and maintaining a sound emotional balance can help you decide what is and what is not important and can help enhance your learning.

Objectivity

Objectivity is the quality or state of being objective; that is, the ability to interpret a situation from an unbiased point of view rather than from your own subjective view. Learning to use rational thought in making decisions will enhance your objectivity. You will learn more about this in Chapter 3, “Critical Thinking Skills.” Learning to be objective about your behavior, as well as that of others, will help you become a mentally and emotionally healthy person.

Emotional and primal stress

You seldom encounter the stress of a life-threatening event as did the early cave dwellers, but your body responds to stress in the same way (Fig. 2-2). Imagine being stalked by a hungry predator. Your heartbeat accelerates, your blood pressure rises, and hormones rush into your bloodstream to send sugar to your muscles and brain. Food digestion temporarily ceases so that more blood is available for energy. In this way, your body prepares to fight the beast or flee to safety. This type of acute stress, which requires a fight-or-flight response, is what McQuade and Aikman call the first primal stress. Because the body does not identify the source of the fear, it reacts in the same way when you get what is commonly known as “stage fright.” Stage fright is not life threatening, but for some, the fear they experience when speaking before a group is so intense that the body responds as if it were (Fig. 2-3). McQuade and Aikman also list two other types of acute stress that cause a primal body reaction.

FIGURE 2-3 Speaking in a key situation such as before a jury can also be a frightening experience, causing the body to respond as if a physical danger were present.

The second primal stress is the basic problem of obtaining food. This type of threat does not elicit a fight-or-flight response but rather persuasion, bartering, searching, and producing. Although the stress resulting from a threat to the food supply is seldom life threatening to us today, it is a psychologic stress that may be as painful as hunger itself. You learned in infancy that while receiving food you also received attention, which you translated as receiving love; you were receiving more than the basic nutrients for life. When food is withheld, you may feel that recognition, attention, and love are also being withheld.

Death, the third primal stress, is inevitable. For many people a philosophic or religious belief provides an anchor in times of turmoil & stress. The unalterable truth is that someday you will die. In the meantime, you should make your life worth living and become the person you want to be.

Coping with life stresses is not new to you. While growing and developing, you made many adjustments and concessions. You learned to distinguish your father, mother, brother, and sister, and finally you realized that you were not any of them—this was your discovery of yourself. Later in childhood you began exploring and discovered that you could control parts of your world. You learned what was dangerous and what was safe, what belonged to you and what belonged to others, and that certain behavior brought rewards whereas other behavior was punished. While you were learning these things, you were developing patterns for coping with life situations. Your behavior was based on your most satisfying experiences. It may sound simplistic, but most people behave in a manner that will give them something in return that will satisfy their basic human needs.

B. F. Skinner, a twentieth century educational psychologist, studied animal and human behavior. He found that, when placed in a controlled environment (i.e., an artificial environment to verify the results of an experiment), animals could be taught to perform complex acts by rewarding the desired behavior. He called this reinforcement behavior. He found that behavior could also be modified through punishment or merely with the absence of a reward. Skinner later worked with humans under less-controlled conditions. He found that a form of the reinforcement theory could be applied to shape and modify human behavior.

Stress and conflict

Stress is a response that can occur when your behavior or that of another fails to produce the desired or expected results. Although you should expect a moderate amount of stress throughout life, a disproportionate amount of stress may occur during your first year away from home. A primary source of stress during adolescence and early adulthood occurs when the need to assert your independence does not produce the expected results in a world that requires a balance between independence and dependence. You must face the problem of needing to be both dependent and independent at the same time. The life situations that require a balance between dependence and independence are many. A financial base is necessary for independent living; however, even with wealth, a totally independent existence is impossible. You will always be dependent on others to a certain degree. Most employment opportunities are authoritarian in nature, which means that workers depend on supervisors and supervisors depend on managers. Regardless of how independent you wish to be, you still have dependent needs; therefore you must accept those aspects of life that involve interdependence. You learn to submit to rational authority and at the same time retain a degree of independence.

Conflict

Conflict is the tension that results from disagreements between incompatible needs or drives, either within you or with others. Conflict does not have to be open warfare or an outbreak of hostilities. It can be as mild and benign as a difference of opinion or diversity in taste. Conflict is an inescapable part of living, and, generally speaking, the closer and more intimate the relationship, the greater the opportunities for conflict. Conflict can be either healthy and constructive or hostile and destructive. Conflicts occur in families, among close friends, in work relationships, in student groups, and even among strangers.

A type of conflict that is increasingly important concerns identity and role assignment. In the past, roles were often assigned by society; male and female roles were clearly defined. Today, people are questioning their assigned roles and are independently seeking their own identities. This is a source of conflict for both sexes for which there is no magic formula. It calls for understanding, tolerance, and patience.

Another category of conflict concerns your perceptions of encroachment on your territory. For example, nonsmokers may be offended by cigarette smoke, or a roommate may disturb you by playing the radio too loudly. Persuasion, tact, diplomacy, and compromise may be required in these situations.

Managing and Resolving Conflict

Some types of conflicts are more easily resolved than others. Factual issues are simpler to resolve than value or identification issues. The most important factor in resolving conflict is to attack the issue rather than the individual. You should focus on the issue and resist any temptation to criticize or demean the other person; remember, a true victory is one in which the relationship remains intact and both people are satisfied with the results.

Resolving conflict with casual acquaintances is different from resolving conflict with family and friends. With casual acquaintances, you are less concerned about maintaining goodwill. The fear of damaging the relationship is slight or perhaps nonexistent. With family and close friends, your desire to maintain the relationship is more intense. Consequently, emotions and feelings influence your behavior. Compromise, participation, and allowance for imperfections are elements that you will have to use in resolving conflicts with others and within yourself.

Internal conflict may be as damaging and destructive as the tense encounters you have with others. With others you can use the inherent fight-or-flight response. Whether you choose fight or flight, your action is clearly defined and directed. Dealing with conflict within yourself is more difficult. You cannot run away from yourself, and to fight yourself is unproductive. To maintain a low-stress lifestyle, you must learn to control the factors that are at the root of tension and anxiety.

Silber and Glim (1981) list seven ways people behave when confronted with conflict: they attack, internalize, deny, isolate, manipulate, withdraw, or confront. These authors suggest confronting the problem in a mature manner in open dialogue. Feelings of empathy are created between two people when they share risks, dangers, doubts, and insecurities. Emotions must be dealt with to bring about a change in behavior. Negative emotions serve as a barrier and must be confronted to resolve the conflict. Silber and Glim also state that you must trust the other person when trying to resolve conflict and you must be open and honest about your objectives, expectations, and needs.

The first step in resolving any conflict is identifying the cause of the conflict. In some cases the cause may be a simple difference of opinion. Factual issues can usually be resolved by accepting the opinion of an authority on the issue. Issues involving values, such as differences in religion, politics, or ethics, are more difficult; a clear-cut answer is unlikely. Facts related to values may be questioned or interpreted differently. For example, a religious writing may be considered to be the authority, but the interpretation of that writing may vary considerably.

Examine the way you have organized your life. Stress and tension can result from the failure to organize your life in a way that is comfortable for you. Pacing your work and study will prevent a sense of urgency and help you keep up with your obligations in a more relaxed manner.

Planning, setting objectives, listing activities for reaching objectives, and scheduling work and recreation should reduce stress (Fig. 2-4). Making improvements in your performance through discipline and motivation should improve your chances of minimizing anxiety, tension, and conflict. The aim is to create a healthier, happier self and to find serenity, meaning, and wholeness in your life.

Learning how to learn

As stated earlier in this chapter, learning how to learn is an important component in mastering the requirements of the radiography program. With the assumption that you have the ability to learn, this discussion is designed to help you use that ability more effectively.

Learning is a matter of storing information in memory and retrieving the information when needed. Storing information is not difficult. The sights and sounds of daily living are stored in memory with no particular effort. It is recall or retrieval from memory that is difficult. Educators have long known this; there was a time when rote memorization, which means learning word-by-word with little internalization, was a common practice in schools. This practice was due, in part, to the economic conditions of the time; only the youth had access to schools, and education ceased abruptly as the youth entered the labor market. Teachers believed they were educating for a lifetime; although the material might not be immediately understood because of the students’ limited life experiences, they could rely on the memory-stored information to serve as the need arose.

Some educators thought that memorizing exercised the mind and thus increased the learning ability. The analogy was drawn from the effects of exercise on muscular tissue—an analogy that recent research suggests is valid.

Understanding does not occur without memory. The ability to think depends on information being stored in memory and on the ability to recover it and logically manipulate it. Curriculum design is based on the assumptions that students remember what has been learned and that advanced courses can build on knowledge stored in memory. So memorizing, even rote drilling, has again become respectable.

Intentional memorization

Many things are stored in memory, some with conscious effort. Intentional memorization occurs in your deliberate pursuit of knowledge in a systematic or planned study situation. It can be divided into two parts: perception and attention.

Perception

If a scene is presented to a group of observers, each observer will probably perceive it in a different way. To make sense of it, each observer will try to match the scene with a similar scene or scenes stored in his or her memory. The observers are unaware that they are supplying data to make the scene fit into a similar scene or experience in their past. Thus, how you perceive something is heavily influenced by what you have stored in memory. Memory also influences the accuracy of your perceptions, which are your observations and resultant mental images. In his experiments in the psychology of perception, Sir Frederick Bartlett found that line drawings that were even vaguely familiar to observers could be perceived and reproduced with greater accuracy than unfamiliar patterns. Thus, the greater the amount of similar information stored in your memory, the more accurate your perceptions and recall of something new.

Suppose you have before you a familiar object, for example, a fish, and are asked to make a line drawing of it. You can probably produce a line drawing that is fairly recognizable to anyone (Fig. 2-5). You perceive the fish with its fins, scales, and gills. Now, suppose marine biology students with a vast amount of knowledge about the particular species of fish undertake the same assignment. Their perceptions of the object will no doubt be different. They will note the lateral fin spread, the positions of the upper and lower fins, the graduated arrangement of the scales, the medially deeply notched tail, and many other details that escape the eye of the untrained observer; their reproductions of their perceptions of the object will be more detailed and accurate (Fig. 2-6). This is an example of how things previously learned and stored in memory affect the perception of objects.

Attention

Attention means concentrating on one activity to the exclusion of others. One of the obvious ways to maintain attention is to eliminate interfering thoughts that come from distractions in the environment or from pressing problems. Many of the distractions in the environment can be controlled (e.g., loud noises, conversation or chatter, uncomfortable room temperature). Inner anxiety, fears, and persistent worry about personal and financial problems are distractions that are more difficult to eliminate. Realizing, however, that these distractions are probably the ones that are most seriously interfering with your ability to concentrate is important. A special effort should be made to discipline your mind. You may need to abandon your problem temporarily during those learning sessions that require intense concentration. If the problem itself cannot be immediately solved, practice shelving it by refusing to give it conscious attention during periods that require intense concentration.

You can also improve your ability to concentrate by preparing to pay attention. Preparing involves creating a state of readiness; this means that you must prepare yourself to get the most from a class lecture, a laboratory demonstration, or a reading assignment. You may encounter lectures that seem dull, speakers who are boring, and reading material that is monotonous. You can add interest to a dull lecture by learning something about the subject and the speaker, if possible, before the lecture begins.

Working rapidly is another way to improve concentration. By this time, you probably have an idea of what your attention span is, so the objective is to maximize the effectiveness of your span. The adage, “what is rapidly learned is quickly forgotten; what is slowly learned is long remembered” has no basis. In fact, experiments have shown the reverse to be true. Rapid learning results in slow forgetting, and slow learning results in rapid forgetting. Working rapidly may require that you increase your listening and reading skills, as well as other mental activities.

Improving Listening Skills

Educators have given a great deal of attention to improving reading skills. Only recently, however, has adequate attention been paid to the skill of listening. The research of Ralph Nichols and Ned Flanders of the University of Minnesota exemplifies this interest in listening skills; they report that people rarely listen with near-maximum efficiency. Nichols estimates that listeners operate at approximately a 25% level of efficiency when listening to a 10-minute talk. He found that Americans average 100 words per minute when speaking informally to an audience. The listener, however, listens at an easy cruising speed of 400 to 500 words per minute. Nichols concludes that the difference between speech speed and thought speed operates as a tremendous pitfall; it allows for increments of time in which the mind of the listener can wander.

Educators and psychologists have suggested some ways for improving listening skills:

1. Create an interest in what is being said. You must make an effort to find a motive or reason for listening so that you get in the right frame of mind.

2. Listen without prejudice and with an open mind (Fig. 2-7). You must guard against tuning out individuals whose ideas and beliefs are not congruent with your own. Your perceptions of the significance of the educator have an effect on how well you listen. Master teachers such as John Dewey and Maria Montessori are not encountered every day, but many educators are worth your listening efforts. Listening with an open mind is equally important with regard to subject matter. In this area, too, students tend to be selective. Details that do not fit comfortably with their notions and values are screened out.

3. Make written notes. Because you cannot remember every part of a lecture and you may unwittingly tune out certain uncomfortable parts, taking notes is important.

Improving Reading Skills

Improving reading skills requires far more than mere speed-reading techniques. The efficient reader thinks, anticipates, and evaluates while reading. Reading is a complex intellectual process with no magic formula. Some basic principles, however, can be used to increase your reading speed without sacrificing comprehension:

1. Quickly scan through the reading material to familiarize yourself with the organization and structure of the body of thought.

2. Develop a clear idea of what you expect to learn. Ask yourself what information you expect to learn and what questions are likely to be answered.

3. Search for the main ideas. Generally, the first sentence of a paragraph gives the main thought; the sentences that follow are a further development of the idea.

Practice exercises may increase your concentration while reading. When reading technical and scientific materials, the exercise that will probably be the most helpful is the practice of recall. Recall is a simple exercise performed by reading a page and then, with the page covered, trying to recall as much of the material as possible. Recall what you have read by reciting it aloud. Reciting gives you the benefit of both hearing and voicing the material, and involving the senses enhances the memory. Reciting aloud is probably the best test of how well you understand the material. Continue to practice the technique until you feel confident in your progress. This exercise not only improves your reading skills, but it is also one of the best ways of increasing your memory power.

Retrieving from memory

Psychologists make a distinction between short-term memory and long-term memory. Remembering a telephone number just long enough to dial it is an example of short-term memory. It is transient and fleeting, and it fades rapidly. Long-term memory is more permanent memory storage (i.e., the recording of memory facts, images, sounds, pleasure, pain, and other life experiences), and it is the subject of this discussion about memory retrieval, which is the recalling, recovering, or obtaining of events and experiences stored in memory.

Long-term memory seems to require more activity in the storing process that relates to the organization and association of the information. The organizing process is not fully understood, but an analogy may help. Think of your mind as a file into which you place all previously acquired data under the appropriate subject headings. The filing of information continues with each new item placed with the associated data previously stored. In time, some of the files contain large quantities of information, and they expand and bulge with the sheer volume of items; other files may receive only a few items of information, and others may receive none. The files that increase only slightly or that do not increase at all may be displaced to make room for the more voluminous ones. Indeed, an inactive file may become lost or may at least require considerable effort to locate. Storage and retrieval in memory may be similar. This is a simple analogy to apply to something as complex as the human memory, but it should serve to make a point: the more facts you associate with an item of information, the more permanent the storage of the item in memory and the more accessible that item becomes.

Donald and Eleanor Laird, in their Techniques for Efficient Remembering, offer some helpful suggestions for retrieving facts from memory. Having a mental set for remembering is their first suggestion, which means that you intend to remember and resolve to remember information that you know will be useful.

Reacting actively is their second suggestion; that is, talk and think about the information; make an application, if possible; and rehearse, recite, and interpret what you have learned.

Refreshing your memory is the third suggestion. Forgetting occurs rather rapidly despite our best efforts to remember. Refreshing or touching up a fading memory reinforces the learning process, which is particularly important with unfamiliar technical material.

Searching for meaning is the fourth—and probably most important—suggestion. Searching for meaning will increase your concentration and thus aid in memorization.

Forgetting

Understanding why you forget will help you to understand how you remember. Forgetting is frustrating when you are trying to pass a test, recall the name of an acquaintance, or solve a pressing problem. You must realize, however, that forgetting is essential to survival. Suppose you could not forget. Imagine what life would be like if all the pains of a lifetime remained fresh in your memory. Think of the mental and emotional anguish you have experienced, and add to this the physical pain of illness and trauma. Suppose none of this faded and the sharp reality of every painful experience was as vivid in your memory now as when it occurred. Nature has marvelous ways of protecting you, and forgetting is one method. This survival mechanism allows you to partially—but not entirely—forget pain.

The inability to forget painful experiences entirely has its positive aspects. It is essential to survival. Remembering the painful consequence of touching a hot stove, jumping from an extreme height, or being hit by a moving or flying object gives direction to your action and allows you to order the safety of your environment.

Forgetting: Pain, Pleasure

The scale from pain to pleasure is a broad one. In the middle of the extremes lies a neutral ground that cannot be identified as painful or pleasant. Some experiences that are neither painful nor particularly pleasant may be interpreted as merely insignificant; this may account for the common failure to remember names, dates, places, and material you do not understand. You seldom forget the name of a significant person or the date and place of a happily anticipated event. When the pleasure-anticipation level is high, you are able to remember with no difficulty. You can even recall pleasurable experiences that happened years ago. Conversely, you tend to forget events associated with embarrassment, disappointment, or other unpleasant feelings. In effect, you can will yourself to forget unpleasant experiences and to remember the pleasant ones.

If it is true that you forget, by design, unpleasant things and remember pleasant things, then why do you sometimes forget what you want to remember? What you want to remember is perceived as pleasant in that it will help you pass an examination, solve a problem, or make a decision. So why does it take so much effort? Forgetting and remembering are activities far too complex to fit neatly into a pain-pleasure concept. However, taking a commonsense approach should help you identify and analyze your own pattern of remembering. This does not mean that you have to enjoy all the material you must commit to memory to remember it.

Errors in Remembering

Human beings have a way of altering and distorting the details of a remembered event. You seldom remember factual details of an event, a speech, or reading material. Some things are incorrectly remembered; for example, where the car is parked. You correctly remember that the car is parked in the parking garage, but you incorrectly think that it is parked on the third level, when in fact it is on the fourth level. You have noticed how the size of the fish caught by the hopeful fisherman increases with each telling or how the brawl in the beer parlor increases in drama at each recounting. Perhaps the most common example of distortion of memory is in reminiscing about the “good old days.” It is not generally remembered that the “good old days” did not include refrigeration, washing machines, television, reliable automobiles, penicillin, polio vaccine, and other things that today’s technology makes possible. Memory does not fade uniformly. Some parts of memory remain to hold together the general structure, but the details are often missing or altered.

Some motive for twisting and distorting the reality of events and experiences must exist. Indeed, two well-confirmed explanations for errors in memory are offered. One is that you distort and retouch memories to make the details more in keeping with what you wish were so; this distortion helps you support your beliefs, values, notions, and hopes and defends your prejudices. The second explanation is that you add detail to your recollection of an event in a way that seems reasonable to you to complete and make sense of a sketchy or incomplete recollection; it is simply more satisfying to fill in and round out the missing details to achieve wholeness.

Inaccurate remembering cannot be eliminated altogether, but cutting it down to some extent is possible. The most obvious safeguard against inaccurate recall is to memorize well. Taking notes is essential for safeguarding important facts and information that must be recalled precisely. Understanding your prejudices and biases, as well as your hopes, dreams, and aspirations, can guard against wishful remembering. The most important safeguard is to understand clearly from the start so that fallacies in thinking will not occur.

The following is a list of recommended practices that will help you optimize your memory’s performance:

1. Give the cerebral cells an opportunity to rest and rejuvenate, which can be done by getting a sufficient amount of sleep and relaxation.

2. Provide the brain with sufficient nutrients to meet the requirements of the cells. Proper nutrition cannot be overemphasized. Research indicates that the brain tires less easily when it receives glucose derived from protein rather than from carbohydrates.

3. Schedule your study periods at a time when you are most alert and attentive.

4. Organize your environment so that distractions are reduced and attention can be focused on the material to be learned.

Conclusion

Becoming a better student requires effort, but understanding yourself, your needs, your aspirations, and your perception of the world around you will enable you to order your activities in a practical and logical manner.

Mastering effective ways to better your skills in reading, listening, and storing and retrieving information in memory will ensure success in becoming a better student. These skills will allow you to proceed with confidence, not only in your radiography program, but throughout your career.

Bibliography

Alessandra, A., Hunsaker, P. Communicating at work. New York: Simon & Schuster, 1993.

Bartlett, F. Remembering, a study in experimental and social psychology. Cambridge University Press, 1964.

Charles, C.M. Educational psychology: the instructional endeavor, ed 2. St Louis: Mosby, 1976.

Cohen, G., Kiss, G., Voi, L.M. Memory current issues, ed 2. Philadelphia: Open University Press, 1993.

Coles, G.S. The learning mystique, a critical look at learning disabilities. New York: Pantheon Books, 1987.

Coury, V. Personal communication (compiled for course supplement). Memphis: University of Tennessee Center for the Health Sciences, 1982.

Fulghum, R. From beginning to end, the rituals of our lives. New York: Villard Books, 1996.

Gordon, S. Psychology for you. Oxford: New York, 1974.

James, W. The principles of psychology. In: The works of William James. Cambridge: Harvard University Press; 1981.

Laird, D.A., Laird, E.C. Techniques for efficient remembering. New York: McGraw-Hill, 1960.

Maslow, A.H. A theory of human motivation. Psychol Rev. 1943;50:370.

McQuade, W., Aikman, A. Stress—what it is—what it can do to your health—how to fight back. New York: Bantam Books, 1975.

Morse, R., Furst, M.L. Stress for success: a holistic approach to stress and its management. New York: Van Nostrand Reinhold, 1979.

Nichols, R.G. Listening is good business. Ann Arbor, Mich: Bureau of Industrial Relations, School of Business Administration The University of Michigan; 1962;vol 1. [no 2,].

Silber, M., Glim, J. We-ism world of the 80s, May/June 1981. [Pace magazine].

Skinner, B.F. Science and human behavior. New York: McMillan, Inc, 1960.

Small, G. The memory prescription: Dr. Gary Small’s 14-day plan to keep your brain and body young. New York: Hyperion, 2004.

Tye, M. The imagery debate. Boston: Massachusetts Institute of Technology, 1991.