Education and Counseling

Behavioral Change

Sections of this chapter were written by Linda Snetselaar, PhD, RD for the previous edition of this text

Key factors in changing nutrition behavior are the person’s awareness that a change is needed and the motivation to change. Nutrition education and nutrition counseling both provide information and motivation, but they do differ. Nutrition education can be individualized or delivered in a group setting; it is usually more preventive than therapeutic, and there is a transmission of knowledge. Counseling is most often used during medical nutrition therapy, one on one. In the one-on-one setting, the nutritionist sets up a transient support system to prepare the client to handle social and personal demands more effectively while identifying favorable conditions for change. The goal of nutrition counseling is to help individuals make meaningful changes in their dietary behaviors.

Behavior Change

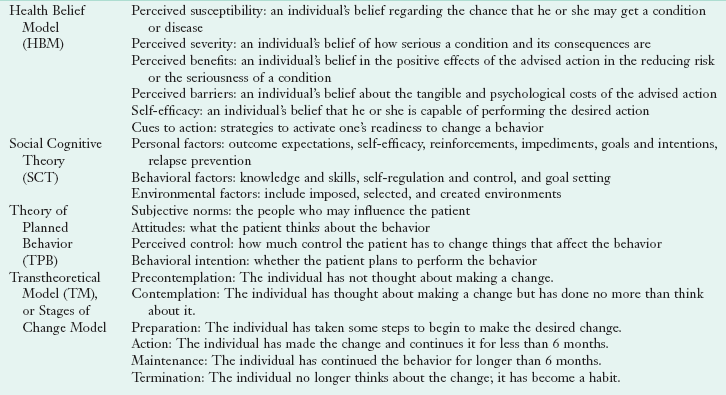

Although there are differences between education and counseling as intervention techniques, the distinctions are not as important as the desired outcome, behavior change. Behavior change requires a focus on the broad range of activities and approaches that affect the individual choosing food and beverages in his or her community and home environment. Behavior modification implies the use of techniques to alter a person’s behavior or reactions to environmental cues through positive and negative reinforcement, and extinction of maladaptive behaviors. In the context of nutrition, both education and counseling can assist the individual in achieving short-term or long-term health goals. Education provides the knowledge and skills needed to change; counseling is aimed at the other steps shown in Figure 15-1.

FIGURE 15-1 Seven steps to behavior change. (Accessed 31 May 2010 from http://www.comminit.com/en/node/201090.)

Factors Affecting the Ability to Change

Multiple factors affect a person’s ability to change, the educator’s ability to teach new information, and the counselor’s ability to stimulate and support small changes. Inability to afford nutrition counseling, unstable living environments, inadequate family or social support, expensive food costs, insufficient transportation, and low literacy are some of the socioeconomic factors that may be barriers for obtaining and maintaining a healthy diet. With a population that is culturally diverse, it is imperative to appreciate the differences in beliefs or understanding that may lead to the inability to change.

Physical and emotional factors also make it hard to change, especially for seniors. Older adults need education and counseling programs that address low vision, poor hearing, limited mobility, decreased dexterity, and memory problems or cognitive impairments (Kamp et al., 2010).

Trust and respect are essential for all helping relationships. The quality of the provider-patient relationship can have either a positive or a negative effect on the outcome of the sessions. If a treatment plan is complex and not understood, decreased adherence is likely. When uncertain of comprehension, asking a few questions can be quite helpful to identify gaps in the patient’s knowledge, understanding, or motivation.

Cultural Competency

The health care community was the first to promote cultural competency and, although there is no agreement on its exact definition, it is fair to say it involves cultural sensitivity or awareness. It requires respecting and understanding the attitudes, values, and beliefs of others; willingness to use cultural knowledge while interacting with clients; and consideration of culture during discussions and recommendations (Ulrey and Amason, 2001). Culture encompasses more than race, religion, or ethnicity; it includes community perspectives and perceptions. Care must be taken not to label people with a stereotype (Stein, 2009).

Gregg et al. (2006) define the following five tenets as the basis for cultural competency:

• Understanding the role of culture. Learning the skills to elicit patients’ individual beliefs and interpretations and to negotiate conflicting beliefs is important to good patient care, regardless of the social, ethnic, or racial backgrounds of the patient.

• Learning about culture and becoming “culturally competent” is not a panacea for health disparities.

• Culture, race, and ethnicity are distinct concepts. Just learning about the culture will not eliminate racism.

• Culture is mutable and multiple; any understanding of a particular cultural context is always incompletely true, always somewhat out of date, and partial.

• Context is critical. Because culture is so complex, so shape-shifting, and so ultimately inseparable from its social and economic context, it is impossible to consider it as an isolated or static phenomenon.

Multicultural awareness is the first step toward establishing rapport and becoming a competent nutrition educator or counselor. It is important to evaluate one’s own beliefs and attitudes and become comfortable with differences among racial, ethnic, or religious beliefs, culture, and food practices (Clinical Insight: The Counselor Looks Within). Heightening awareness of personal biases and increasing sensitivity allows the counselor to be more effective in understanding what the client may need to move forward.

Implementation of a cultural competency in interactions with patients or clients may seem like a very time-consuming challenge, without readily available resources in some cases. However, having this skill will in the end result in a more thorough communication with the patient or client and ultimately a better outcome. The Joint Commission continues to strengthen guidelines related to communication and cultural competency with guidelines and roadmaps for hospitals (The Joint Commission, 2010). Cultural competency is expected to be added as a Joint Commission standard in the future (Stein, 2009).

Communication

One of the most essential competencies in the delivery of health care is effective multicultural communication. The United States will continue to become more diverse. By the year 2050, it is estimated that almost 25% of the total U.S. population will be Hispanic. Of those who are non-Hispanic, projections for 2050 reflect a population that is 72.1% white, 14.6% black, and 8% Asian (Shrestha, 2010). Each culture has values, ideas, assumptions, and beliefs about life and a common system of encoding and decoding verbal and nonverbal messages (Ulrey and Amason, 2001).

Language is always important in communication. Although knowing several languages can be an asset, many will rely on translators. Unofficial translators, such as family or friends, are not usually a good choice because of a lack of understanding of nutrition and health. Using professional translators is also not without limitations in that the educator needs to understand not only the client but also the interpreter. The educator should maintain contact with the client and explain the role of the interpreter (Mossavar-Rahmani, 2007). When working with clients who have limited ability to speak and understand English, always use common terms, avoiding slang and words with multiple meanings. Always speak directly to the client, even when using a translator, and watch the client for nonverbal responses during the translation.

Communication not only encompasses language but also the context in which words are interpreted, including posture, gestures, concepts of time, spatial relationships, the role of the individual within a group, status and hierarchy of persons, and the setting (Satia-About et al., 2002). Nonverbal messages convey information about relationships. The way in which cultures combine verbal and nonverbal messages to transmit a message determines the context of the communication (Kittler and Sucher, 2007). Spatial relationships vary among cultures and among individuals. Movements such as gestures, facial expressions, and postures are often the cause of confusion and misinterpretations in intercultural communication. Good posture is an important sign of respect in nearly all cultures. Rules regarding eye contact are usually complex and vary according to issues such as gender, distance apart, and social status (Clinical Insight: Body Language and Communication Skills).

All counselors should be empathetic, genuine, and respectful. A good way to begin communication is by finding out how the client prefers to be addressed. Although in America it is common to call strangers and acquaintances by their given names, nearly all other cultures expect a more respectful approach. Listening sensitively, sharing control, accepting differences, demonstrating sincere concern, respecting other cultures, seeking feedback, and being natural and honest are strategies important to achieving client compliance and satisfaction (Patterson, 2004). Use of these techniques helps make the counseling sessions more effective and satisfying for both parties.

Message Framing

The way in which a message is framed can influence its persuasiveness and effectiveness. Framing a message in a positive way focuses on the positive aspects of change; framing it with a negative spin highlights what could be lost without the change. By observing the community in which one practices, the counselor can adjust his or her comments accordingly. Visiting a grocery store, restaurants in the neighborhood, schools, or social centers will help the nutritionist understand the client’s perspective. For example, knowing that fresh produce is not readily available from the local grocery store, the counselor may discuss the benefits of using canned or frozen vegetables instead of praising only the benefits of raw vegetables.

Messages and materials must be available for various educational levels, English language proficiencies, geographic locations, sexual orientation (lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender), and folk customs and beliefs. Instructional information should be simple, clear, and free from bias in content and use of graphics or pictures.

Health Literacy

Low health literacy is common among older adults, minorities, and those who are medically underserved or have a low socioeconomic status (Health Resources and Services Administration, 2010). This problem can lead to poor management of chronic health conditions, as well as low adherence to recommendations. The counselor should be careful to avoid jargon and to use language or examples that have relevance to the client. Although there are many guidelines for writing health materials at lower literacy levels, oral communication requires interactive dialogue for assessment of the client’s understanding and ability to absorb potentially complex concepts. Relying on the client’s educational attainment provides some guidance, but asking the client to repeat explanations in his or her own words can also help the nutrition educator evaluate the client’s level of understanding. Useful resources from the Agency on Healthcare Research and Quality are Rapid Estimate of Adult Health Literacy in Medicine (REALM) and Short Assessment of Health Literacy for Spanish Adults (SAHLSA-50) (Agency on Healthcare Research and Quality, 2010).

Models for Behavior Change

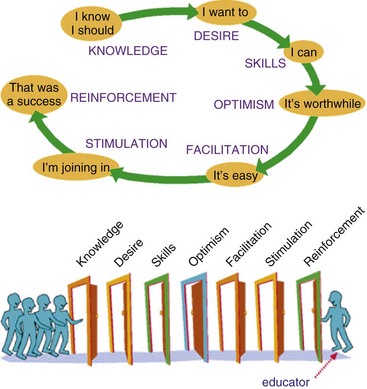

Changing behavior is the ultimate goal for nutrition counseling and education. Simply providing a pamphlet or a list of foods usually does not change eating behavior. Because so many different factors influence what someone eats, nutritionists have been learning from behavioral scientists to identify and intervene based on mediators of people’s eating behavior. Health professionals can support individuals in deciding what and when to change by using a variety of health behavior theories. Some of the most common theories for behavior change are listed in Table 15-1, with examples described in the following paragraphs.

Health Belief Model

The health belief model (HBM) focuses on a disease or condition, and factors that may influence behavior related to that disease (Contento, 2007). The HBM has been used most with behaviors related to diabetes and osteoporosis, focusing on barriers to and benefits of changing behaviors (Sedlak et al., 2007; Tussing and Chapman-Novakofski, 2005).

Social Cognitive Theory

Social cognitive theory (SCT) represents the reciprocal interaction among personal, behavioral, and environmental factors (Bandura, 1977, 1986). This theory is quite extensive and includes many variables; some of the most important to counseling include self-efficacy, goal setting, and relapse prevention.

Transtheoretical Model of Change

The transtheoretical model (TTM), or stages of change model, has been used for many years to alter addictive behaviors. TTM describes behavior change as a process in which individuals progress through a series of six distinct stages of change, as shown in Table 15-1 (Prochaska et al., 1992; Prochaska and DiClemente, 1982; Sigman-Grant, 1996). The value of the TTM is in determining the individual’s current stage, then using change processes matched to that stage (Resnicow et al., 2006). Recently, however, the effectiveness of the TTM has been questioned (Salmela et al., 2009).

Theory of Planned Behavior

The theory of planned behavior (TPB) is based on the concept that intentions predict behavior (Ajzen, 1991). Intentions are predicted by attitudes, subjective norms (important others), and perceived control. This theory is most successful when a discrete behavior is targeted (e.g. milk consumption), but has also been used for healthy diet consumption (Brewer et al., 1999; Pawlak et al., 2009).

Counseling Strategy: Cognitive Behavioral Therapy

Cognitive behavior therapy (CBT) can be used to help individuals develop skills to achieve healthier eating habits. Instead of helping to decide what to change, it helps to identify how to change thinking, behavior, and communication. Lifestyle modification can be time-consuming and skill-intensive, but new methods include use of the Internet and cognitive therapy to alter distorted thinking. CBT can be used for obesity treatment to promote and encourage self-care among patients, or for managing chronic diseases such as diabetes or cardiovascular disease.

Many textbooks describe the CBT process. For example, for a textbook on eating disorders describes steps such as shaping concerns and mindsets, managing dietary restraint and rules, and handling events and moods related to eating (Fairburn et al., 2003). CBT counselors can help clients explore troubling themes, strengthen their coping skills, and focus on their well being. The CBT process is practical, action-oriented, and goal-directed. CBT training is available from many universities or centers for cognitive therapy (National Alliance on Mental Illness, 2010).

Counseling Strategy: Motivational Interviewing

Motivational interviewing (MI) has been used to encourage clients to identify discrepancies between how they would like to behave and how they are behaving, and then motivate them to change (Miller and Rollnick, 2002). Studies point to the positive influence of MI on changes in dietary behavior, either alone or in combination with other strategies. These include increases in self-efficacy in relation to dietary changes, increased fruit and vegetable intake, and decreased body mass index. As with any strategy, better outcomes were associated with longer interventions and increased number of counseling session (Martins and McNeil, 2009). The following are principles used in MI to enhance behavior change.

Expressing Empathy

Empathy, nutrition counselor acceptance of what a client feels in times of turmoil, can often result in change. Acceptance facilitates change. Beyond this acceptance is a skillful form of reflective listening, which allows the client to describe thoughts and feelings, while the nutritionist reflects back understanding. Many clients have no one with whom to discuss problems in their lives. This opportunity to have someone listen and understand the emotions behind the words is crucial to eventual dietary change.

As clients review situations in their lives and lack of time for dietary changes, the nutrition counselor will hear ambivalence. On the one hand, clients want to make changes; on the other hand, they want to pretend that change is not important. Ambivalence is normal.

Developing Discrepancy

An awareness of consequences is important. Identifying the advantages and disadvantages of modifying a behavior, or developing discrepancy, is a crucial process in making changes.

Rolling with Resistance (Legitimation, Affirmation)

Invite new perspectives without imposing them. The client is a valuable resource in finding solutions to problems. Perceptions can be shifted, and the nutrition counselor’s role is to help with this process. For example, a client who is wary of describing why she is not ready to change may become much more open to change if she sees openness to her resistive behaviors. When it becomes okay to discuss resistance, the rationale for its original existence may seem less important.

Supporting Self-Efficacy

Belief in one’s own capability to change is an important motivator. The client is responsible for choosing and carrying out personal change. However, the nutrition counselor can support self-efficacy by having the client try behaviors or activities while the counselor is there.

First Session

The first session of a one-on-one educational intervention establishes the counseling relationship. The environment should be conducive to privacy, and there should be a plan for reduction of interruptions (e.g., no telephone calls). The counselor should be seated in a manner that reflects interest in the client, such as sitting directly across from one another in chairs without a desk as a barrier. In this first session, it is most important to establish rapport and invite input from the client.

Establishing Rapport

To build rapport, one begins by asking how the client prefers to be addressed.

It is acceptable to ask one or two questions that are relevant to important aspects of the client’s life or conversational to allow the client to adjust.

Some clients may choose very little conversation, while others are quite talkative. At some point, the nutrition counselor needs to move the conversation to the point of the visit.

In an initial visit, the counselor introduces the subject of the session and invites the client to contribute. The following are sample conversations:

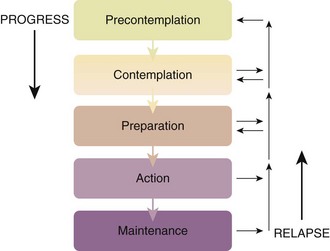

Although not every first session lends itself to an assessment of the client’s readiness to change, at some point after the topic has been agreed upon, the counselor must assess if the client is ready to change. To identify in which of these three stages a client is, see Figure 15-2.

FIGURE 15-2 A model of the stages of change. In changing, a person progresses down these steps to maintenance. If relapse occurs, he or she gets back on the steps at some point and works down them again.

It may be difficult to build rapport with some clients. Someone who appears hostile, unusually quiet, or dismissive may have more success with either a different nutritionist or with someone with whom he or she has background in common. In those cases, working with a peer educator may be most effective. The peer educator should ideally share similarities with the target population in terms of age or ethnicity, and have primary experience in the nutrition topic (e.g., has breastfed her infant) (Pérez-Escamilla et al., 2008). Peer educators are usually community health workers or paraprofessionals. The Expanded Food and Nutrition Education Program (EFNEP) has demonstrated the effectiveness and cost efficiency of peer educators (Dollahite et al., 2008). In prenatal or WIC clinics, breastfeeding peer counselors are often highly effective in helping new mothers with their questions and concerns.

Assessment Results: Choosing Focus Areas

The purpose of assessment is to identify the client’s stage of change and to provide appropriate help in facilitating change. The assessment should be completed in the first visit if possible. If conversation extends beyond the designated time for the session, the assessment steps should be completed at the next session. The nutritional assessment requires gathering the appropriate anthropometric, biochemical, clinical, dietary, and economic data relating to the client’s condition. The nutritional diagnosis then focuses on any problems related to food or nutrient intake.

Determining present eating habits provides ideas on how to change in the future. It is important to review the client’s eating behavior, to identify areas needing change, and to help the client select goals that will have the most effect on health conditions. For instance, if the nutrition diagnosis includes excessive fat intake (nutrient intake [NI]-5102), inappropriate intake of food fats (NI-51.3), excessive energy intake (NI-1.5), inadequate potassium intake (NI-55.1), food- and nutrition-related knowledge deficit (nutrition behavior [NB]-1.1), and impaired ability to prepare foods or meals (NB-2.4), the counselor may need to focus on the last diagnosis before the others. If all other diagnoses are present except impaired ability to prepare foods or meals (NB-2.4), the nutritionist may want to have a discussion about whether excessive fat intake, inappropriate intake of types of food fats, or excessive energy intake are more appealing or possible for the client to focus on first.

Assessment of Readiness to Change

Once the nutrition diagnosis is selected for intervention, it is important to assess readiness for changes. Using a ruler that allows the client to select his or her level of intention to change is one method of allowing client participation in the discussion. The counselor asks the client, “On a scale of 1 to 12, how ready are you right now to make any new changes to eat less fat? (1 = not ready to change; 12 = very ready to change).” The nutritionist may use this method with each nutrition diagnosis to help the client decide where to focus first.

Three possibilities for readiness exist: (1) not ready to change; (2) unsure about change; (3) ready to change. These three concepts of readiness have condensed the six distinct stages of change described in this chapter to assist the counselor in determining the level of client readiness. There are many concepts to remember, and readiness to change may fluctuate during the course of the discussion. The counselor must be ready to move back and forth between the phase-specific strategies. If the client seems confused, detached, or resistant during the discussion, the counselor should return and ask about readiness to change. If readiness has lessened, tailoring the intervention is necessary. Not every counseling session has to end with the client’s agreement to change; even the decision to think about change can be a useful conclusion.

Not-Ready-To-Change Counseling Sessions

In approaching the “not-ready-to-change” stage of intervention, there are three goals: (1) facilitate the client’s ability to consider change, (2) identify and reduce the client’s resistance and barriers to change, and (3) identify behavioral steps toward change that are tailored to each client’s needs. At this stage identifying barriers (HBM), the influence of subjective norms and attitudes (TPB), or personal and environmental factors (SCT) that may have negative influences on the intention to change can be helpful. To achieve these goals, several communication skills are important to master: asking open-ended questions, listening reflectively, affirming the patient’s statements, summarizing the patient’s statements, and eliciting self-motivational statements.

Asking Open-Ended Questions

Open-ended questions allow the client to express a wider range of ideas, whereas closed questions can help in targeting concepts and eliminating tangential discussions. For the person who is not ready to change, targeted discussions around difficult topics can help focus the session. The nutritionist asks questions that must be answered by explaining and discussing, not by one-word answers. This is particularly important for someone who is not ready to change, because it opens the discussion to problem areas that keep the client from being ready. The following statements and questions are examples that create an atmosphere for discussion:

• “We are here to talk about your dietary change experiences to this point. Could you start at the beginning and tell me how it has been for you?” (SCT, personal factors)

• “What are some things you would like to discuss about your dietary changes so far? What do you like about them? What don’t you like about them?” (TPB, attitudes)

Reflective Listening

Nutrition counselors not only listen but also try to tag the feelings that surface as a client is describing difficulties with an eating pattern. Listening is not simply hearing the words spoken by the client and paraphrasing them back. Figure 15-3 shows a nutrition counselor listening reflectively to her client.

Reflective listening involves a guess at what the person feels and is phrased as a statement, not a question. By stating a feeling, the nutrition counselor communicates understanding. The following are three examples of listening reflectively:

Affirming

Counselors often understand the idea of supporting a client’s efforts at following a new eating style but do not put those thoughts into words. When the counselor affirms someone, there is alignment and normalization of the client’s issues. In alignment the counselor tells the client that he or she understands these difficult times. Normalization means telling the client that he or she is perfectly within reason and that it is very normal to have such reactions and feelings. The following statements indicate affirmation:

Summarizing

The nutrition counselor periodically summarizes the content of what the client has said by covering all the key points. Simple and straightforward statements are most effective, even if they involve negative feelings. If conflicting ideas arise, the counselor can use the strategy exemplified by the statement, “On the one hand you want to change, but love those old eating patterns.” This helps the client recognize the dichotomy in thinking that often prevents behavior change.

Eliciting Self-Motivational Statements

The four communication strategies (asking open-ended questions, listening reflectively, affirming, and summarizing) are important when eliciting self-motivational statements. The goal here is for the client to realize that a problem exists, that concern results, and that positive steps in the future can be taken to correct the problem. The goal is to use these realizations to set the stage for later efforts at dietary change. Examples of questions to use in eliciting self-motivational feeling statements follow.

Intention to Change

• “The fact that you’re here indicates that at least a part of you thinks it’s time to do something. What are the reasons you see for making a change?”

• “If you were 100% successful and things worked out exactly as you would like, what would be different?”

• “What things make you think that you should keep on eating the way you have been?” And in the opposite direction, “What makes you think it is time for a change?”

Optimism

• “What encourages you that you can change if you want to?”

• “What do you think would work for you if you decided to change?”

Clients in this “not-ready-to-change” category have already told the counselor they are not doing well at making changes. Usually if a tentative approach is used by asking permission to discuss the problem, the client will not refuse. One asks permission by saying, “Would you be willing to continue our discussion and talk about the possibility of change?” At this point, it is helpful to discuss thoughts and feelings about the current status of dietary change by asking open-ended questions:

• “Tell me why you picked _________ on the ruler.” (Refer to previous discussion on the use of a ruler.)

• “What would have to happen for you to move from a _________ to a _________ (referring to a number on the ruler)? How could I help get you there?”

• “If you did start to think about changing, what would be your main concern?”

To show real understanding about what the client is saying, it is beneficial to summarize the statements about his or her progress, difficulties, possible reasons for change, and what needs to be different to move forward. This paraphrasing allows the client to rethink his or her reasoning about readiness to change. The mental processing provides new ideas that can promote actual change.

Ending the Session

Counselors often expect a decision and at least a goal-setting session when working with a client. However, it is important in this stage to realize that traditional goal setting will result in feelings of failure on both the part of the client and the nutritionist. If the client is not ready to change, respectful acknowledgment of this decision is important. The counselor might say, “I can understand why making a change right now would be very hard for you. The fact that you are able to indicate this as a problem is very important, and I respect your decision. Our lives do change, and, if you feel differently later on, I will always be available to talk with you. I know that, when the time is right for you to make a change, you will find a way to do it.” When the session ends, the counselor will let the client know that the issues will be revisited after he or she has time to think. Expression of hope and confidence in the client’s ability to make changes in the future, when the time is right, will be beneficial. Arrangements for follow-up contact can be made at this time.

With a client who is not ready to change it is easy to become defensive and authoritarian. At this point, it is important to avoid pushing, persuading, confronting, coaxing, or telling the client what to do. It is reassuring to a nutritionist to know that change at this level will often occur outside the office. The client is not expected to be ready to do something during the visit (see New Directions: Dietitian Counselor as Life Coach).

Unsure-About-Change Counseling Sessions

The only goal in the “unsure-about-change” session is to build readiness to change. This is the point at which changes in eating behavior can escalate. This “unsure” stage is a transition from not being ready to deal with a problem eating behavior to preparing to continue the change. It involves summarizing the client’s perceptions of the barriers to a healthy eating style and how they can be eliminated or circumvented to achieve change. Heightened self-efficacy may provide confidence that goals can be achieved. A restatement of the client’s self-motivational statements assists in setting the stage for success. The client’s ambivalence is discussed, listing the positive and negative aspects of change. The nutritionist can restate any statements that the client has made about intentions or plans to change or to do better in the future.

One crucial aspect of this stage is the process of discussing thoughts and feelings about current status. Use of open-ended questions encourages the client to discuss dietary change progress and difficulties. Change is promoted through discussions focused on possible reasons for change. The counselor might ask the question: “What would need to be different to move forward?”

This stage is characterized by feelings of ambivalence. The counselor should encourage the client to explore ambivalence to change by thinking about “pros” and “cons.” Some questions to ask are:

• “What are some of the things you like about your current eating habits?”

• “What are some of the good things about making a new or additional change?”

• “What are some of the things that are not so good about making a new or additional change?”

By trying to look into the future, the nutrition counselor can help a client see new and often positive scenarios. As a change facilitator, the counselor helps to tip the balance away from being ambivalent about change toward considering change by guiding the client to talk about what life might be like after a change, anticipating the difficulties as well as the advantages. An example of an opening to generate discussion with the client might be: “I can see why you’re unsure about making new or additional changes in your eating habits. Imagine that you decided to change. What would that be like? What would you want to do?” The counselor then summarizes the client’s statements about the “pros” and “cons” of making a change and includes any statements about wanting, intending, or planning to change.

The next step is to negotiate a change. There are three parts to the negotiation process. The first is setting goals. Set broad goals at first and hold more specific nutritional goals until later. “How would you like things to be different from the way they are?” and “What is it that you would like to change?”

The second step in negotiation is to consider options. The counselor asks about alternative strategies and options and then asks the client to choose from among them. This is effective because, if the first strategy does not work, the client has other choices. The third step is to arrive at a plan, one that has been devised by the client. The counselor touches on the key points and the problems and then asks the client to write down the plan.

To end the session the counselor asks about the next step, allowing the client to describe what might occur next in the process of change. The following questions provide some ideas for questions that might promote discussion:

Resistance Behaviors And Strategies To Modify Them

Resistance to change is the most consistent emotion or state when dealing with clients who have difficulty with dietary change. Examples of resistance behaviors on the part of the client include contesting the accuracy, expertise, or integrity of the nutrition counselor; or directly challenging the accuracy of the information provided (e.g., the accuracy of the nutrition content). The nutrition counselor may even be confronted with a hostile client. Resistance may also surface as interrupting, when the client breaks in during a conversation in a defensive manner. In this case, the client may speak while the nutrition counselor is still talking without waiting for an appropriate pause or silence. In another, more obvious manner, the client may break in with words intended to cut off the nutrition counselor’s discussion.

When clients express an unwillingness to recognize problems, cooperate, accept responsibility, or take advice, they may be denying a problem. Some clients blame other people for their problems (e.g., a wife may blame her husband for her inability to follow a diet). Other clients may disagree with the nutrition counselor when a suggestion is offered, but they frequently provide no constructive alternative. The familiar “Yes, but …” explains what is wrong with the suggestion but offers no alternative solution.

Clients try to excuse their behavior. A client may say, “I want to do better, but my life is in a turmoil since my husband died 3 years ago.” An excuse that was once acceptable is reused even when it is no longer a factor in the client’s life.

Some clients make pessimistic statements about themselves or others. This is done to dismiss an inability to follow an eating pattern by excusing poor compliance as just a given resulting from past behaviors. Examples are “My husband will never help me” or “I have never been good at sticking with a goal. I’m sure I won’t do well with it now.”

In some cases, clients are reluctant to accept options that may have worked for others in the past. They express reservations about information or advice given. “I just don’t think that will work for me.” Some clients will express a lack of willingness to change or an intention not to change. They make it very clear that they want to stop the dietary regimen.

Often clients show evidence that they are not following the nutrition counselor’s advice. Clues that this is happening include using a response that does not answer the question, providing no response to a question, or changing the direction of the conversation.

These types of behavior can occur within a counseling session as clients move from one stage to another. They are not necessarily stage-specific, although most are connected with either the “not ready” or “unsure-about-change” stages. A variety of strategies are available to assist the nutrition counselor in dealing with these difficult counseling situations. These strategies include reflecting, double-sided reflection, shifting focus, agreeing with a twist, emphasizing personal choice, and reframing. Each of these options is described in the following paragraphs.

Reflecting

In reflecting, the counselor identifies the client’s emotion or feeling and reflects it back. This allows the client to stop and reflect on what was said. An example of this type of counseling is, “You seem to be very frustrated by what your husband says about your food choices.”

Double-Sided Reflection

In double-sided reflection, the counselor uses ideas that the client has expressed previously to show the discrepancy between the client’s current words and the previous ones. For example:

Shifting Focus

Clients may hold onto an idea that they think is getting in the way of their progress. The counselor might question the feasibility of continuing to focus on this barrier to change when other barriers may be more appropriate targets. For example:

Agreeing with a Twist

This strategy involves offering agreement, then moving the discussion in a different direction. The counselor agrees with a piece of what the client says but then offers another perspective on his or her problems. This allows the opportunity to agree with the statement and the feeling, but then to redirect the conversation onto a key topic. For example:

Reframing

With reframing the counselor changes the client’s interpretation of the basic data by offering a new perspective. The counselor repeats the basic observation that the client has provided and then offers a new hypothesis for interpreting the data. For example:

These strategies help by offering tools to ensure that nutrition counseling is not ended without appropriate attempts to turn difficult counseling situations in a more positive direction.

Self-Efficacy and Self-Management

Counselors should always emphasize that any future action belongs to the client, that the advice can be taken or disregarded. This emphasis on personal choice (autonomy) helps clients avoid feeling trapped or confined by the discussion. Belief in the ability to change through his or her own decisions is an essential and worthy goal. A sense of self-efficacy reflects the belief about being capable of influencing events and choices in life. These beliefs determine how individuals think, feel, and behave. If people doubt their capabilities, they will have weak commitments to their goals. Success breeds success, and failure breeds a sense of failure. Having resilience, positive role models, and effective coaching can make a significant difference.

Ready-To-Change Counseling Sessions

The major goal in the “ready-to-change” session is to collaborate with the client to set goals that include a plan of action. The nutrition counselor provides the client with the tools to use in meeting nutrition goals. This is the stage of change that is most often assumed when a counseling session begins. To erroneously assume this stage means that inappropriate counseling strategies set the stage for failure. Misaligned assumptions often result in lack of adherence on the part of the client and discouragement on the part of the nutritionist. Therefore it is important to discuss the client’s thoughts and feelings about where he or she stands relative to the current change status. Use of open-ended questions helps the client confirm and justify the decision to make a change and in which area. The following questions may elicit information about feelings toward change:

• “Tell me why you picked _____ on the ruler.”

• “Why did you pick (nutrition diagnosis 1) instead of (other nutrition diagnoses)?”

In this stage, goal setting is extremely important. Here the counselor helps the client set a realistic and achievable short-term goal: “Let’s do things gradually. What is a reasonable first step? What might be your first goal?”

Action Plan

Following goal setting, an action plan is set to assist the client in mapping out the specifics of goal achievement. Identifying a network to support dietary change is important. What can others do to help?

Early identification of barriers to adherence is also important. If barriers are identified, plans can be formed to help eliminate these roadblocks to adherence.

Many clients fail to notice when their plan is working. Clients can be asked to summarize their plans and identify markers of success. The counselor then documents the plan for discussion at future sessions and ensures that the clients also have their plans in writing. The session should be closed with an encouraging statement and reflection about how the client identified this plan personally. Indicate that each person is the expert about his or her own behavior. Compliment the client on carrying out the plan. Ways to express these ideas to clients are:

• “You are working very hard at this, and it’s clear that you’re the expert about what is best for you. You can do this!”

• “Keep in mind that change is gradual and takes time. If this plan doesn’t work, there will be other plans to try.”

The key point for this stage is to avoid telling the client what to do. Clinicians often want to provide advice. However, it is critical that the client express ideas of what will work best: “There are a number of things you could do, but what do you think will work best for you?” The next contact may be in person, online, or by phone.

Following up with clients by phone or online has become a popular counseling method for many nutritionists. When behavior and counseling theories are combined with phone counseling, the results have been effective in managing weight, type 2 diabetes, and hypertension (Eakin et al., 2009; Kim et al., 2009). Online weight reduction programs have also been successful, especially when the websites are interactive and communication with counselors is available (Krukowski et al., 2009).

Evaluation Of Effectiveness

Clinicians need to evaluate their services. Just completing the process does not mean that outcomes will match the goals. The sessions must be confidential, empowering, and personalized. When the American Dietetic Association Evidence Analysis Library Nutrition Counseling Workgroup conducted a review of literature related to behavior change theories and strategies used in nutrition counseling, they found the following (Spahn et al., 2010):

1. Strong evidence supports the use of a CBT in facilitating modification of targeted dietary habits, weight, and cardiovascular and diabetes risk factors.

2. MI is a highly effective counseling strategy, particularly when combined with CBT.

3. Few studies have assessed the application of the TTM or SCT on nutrition-related behavior change.

4. Self-monitoring, meal replacements, and structured meal plans are effective; financial reward strategies are not.

5. Goal setting, problem solving, and social support are effective strategies.

6. Research is needed in more diverse populations to determine the most effective counseling techniques and strategies.

American Counseling Association

American Dietetic Association—Nutrition Diagnosis and Intervention

Counseling Relationships—Code of Ethics

http://www.counseling.org/Resources/CodeOfEthics/TP/Home/CT2.aspx

http://www.thinkculturalhealth.org/

http://www.thinkculturalhealth.org/online_resources.asp

Cultural Competency with Adolescents

http://www.ama-assn.org/ama1/pub/upload/mm/39/culturallyeffective.pdf

International Coaching Federation

http://www.coachfederation.org/

Journal of Counseling Psychology

http://www.apa.org/pubs/journals/cou/

http://minorityhealth.hhs.gov/

References

Agency on Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ). Health literacy measurement tools. Accessed 31 May 2010 from http://www.ahrq.gov/populations/sahlsatool.htm.

Ajzen, I. The theory of planned behavior. Organ Behav Hum Decis Process. 1991;50:179.

Bandura, A. Social foundations of thought and action. Englewood Cliffs, N.J.: Prentice-Hall; 1986.

Bandura, A. Social learning theory. New York: General Learning Press; 1977.

Brewer, JL, et al. Theory of reasoned action predicts milk consumption in women. J Am Diet Assoc. 1999;99:39.

Contento, I. Nutrition education: linking research, theory and practice. Sudbury, Mass: Jones and Bartlett; 2007.

Dollahite, J, et al. An economic evaluation of the expanded food and nutrition education program. J Nutr Educ Behav. 2008;40:134.

Eakin, E, et al. Telephone counseling for physical activity and diet in primary care patients. Am J Prev Med. 2009;36:142.

Fairburn, CG, et al. Enhanced cognitive behavior therapy for eating disorders: the core protocol. St Louis: Elsevier; 2003.

Gregg, J, et al. Losing culture on the way to competence: the use and misuse of culture in medical curriculum. Acad Med. 2006;81:542.

Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA). Health literacy. Accessed 31 May 2010 from http://www.hrsa.gov/healthliteracy/.

Kamp, B, et al. Position of the American Dietetic Association, American Society for Nutrition, and Society for Nutrition Education: food and nutrition programs for community-residing older adults. J Nutr Educ Behav. 2010;42:72.

Kim, Y, et al. Telephone intervention promoting weight-related health behaviors. Prev Med. 16 December 2009. [[Epub ahead of print.]].

Kittler, PG, Sucher, KP. Food and culture, ed 5. Belmont, Calif: Wadsworth- Thomson Learning; 2007.

Krukowski, RA, et al. Recent advances in internet-delivered, evidence-based weight control programs for adults. J Diabetes Sci Technol. 2009;3:184.

Martins, RK, McNeil, DW. Review of motivational interviewing in promoting health behaviors. Clin Psychol Rev. 2009;29:283.

Miller, W, Rollnick, S. Motivational interviewing: preparing people for change, ed 2. New York: Guilford; 2002.

Mossavar-Rahmani, Y. Applying motivational enhancement to diverse populations. J Am Diet Assoc. 2007;107:918.

National Alliance on Mental Illness (NAMI). Cognitive-behavioral therapy. Accessed 31 May 2010 from http://www.nami.org/Template.cfm?Section=About_Treatments_and_Supports&template=/ContentManagement/ContentDisplay.cfm&ContentID=7952.

Patterson, CH. Do we need multicultural counseling competencies? J Mental Health Couns. 2004;26:67.

Pawlak, R, et al. Predicting intentions to eat a healthful diet by college baseball players: applying the theory of planned behavior. J Nutr Educ Behav. 2009;41:334.

Pérez-Escamilla, R, et al. Impact of peer nutrition education on dietary behaviors and health outcomes among Latinos: a systematic literature review. J Nutr Educ Behav. 2008;40:208.

Prochaska, JO, DiClemente, CC. Transtheoretical therapy: toward a more integrative model of change. Psychother Theory Res Pract. 1982;20:276.

Prochaska, JO, et al. In search of how people change. Am Psychol. 1992;47:1102.

Resnicow, K, et al. Motivational interviewing for pediatric obesity: conceptual issues and evidence review. J Am Diet Assoc. 2006;106:2024.

Salmela, S, et al. Transtheoretical model-based dietary interventions in primary care: a review of the evidence in diabetes. Health Educ Res. 2009;24:237.

Satia-Abouta, J, et al. Dietary acculturation: applications to nutrition research and dietetics. J Am Diet Assoc. 2002;102:1105.

Sedlak, CA, et al. DXA, health beliefs, and osteoporosis prevention behaviors. J Aging Health. 2007;19:742.

Shrestha, LB, The changing demographic profile of the United States. Congressional Research Service Report for Congress 30 January 2010. from Accessed. http://www.fas.org/sgp/crs/misc/index.html

Sigman-Grant, M. Stages of change: a framework for nutrition interventions. Nutr Today. 1996;31:162.

Spahn, JM, et al. State of the evidence regarding behavior change theories and strategies in nutrition counseling to facilitate health and food behavior change. J Am Diet Assoc. 2010;110:879.

Stein, K. Navigating cultural competency: in preparation for an expected standard in 2010. J Am Diet Assoc. 2009;109:1676.

The Joint Commission. Advancing Effective Communication, Cultural Competence, and Patient- and Family-Centered Care: A Roadmap for Hospitals. Oakbrook Terrace, IL: The Joint Commission; 2010.

Tussing, L, Chapman-Novakofski, K. Osteoporosis prevention education: behavior theories and calcium intake. J Am Diet Assoc. 2005;105:92.

Ulrey, KL, Amason, P. Intercultural communication between patients and health care providers: an exploration of intercultural communication effectiveness, cultural sensitivity, stress and anxiety. Health Comm. 2001;13:449.