Chapter 19 Abnormalities of early pregnancy

This chapter is concerned with conditions that occur during the first 20 weeks of pregnancy. These are a significant cause of maternal morbidity and even on occasion mortality. Midwives will often be the first point of contact by women seeking advice for these problems and be involved in care in both primary and secondary healthcare settings. Increased understanding of the abnormalities that can occur in early pregnancy will enhance the quality of midwifery care provided for these women.

Bleeding in early pregnancy

Vaginal bleeding occurs in up to 25% of pregnancies prior to 20 weeks. It is a major cause of anxiety for all women, especially those who have experienced previous pregnancy loss, and may be the presenting symptom of life-threatening conditions, such as ectopic pregnancy. Bleeding should always be considered as abnormal in pregnancy and investigated appropriately.

A small amount of bleeding may occur as the blastocyst implants in the endometrium 5–7 days after fertilization (implantation bleed). If this occurs at the time of expected menstruation it may be confused with a period and so affect calculations of gestational age based on the last menstrual period.

The common causes for bleeding in early pregnancy are miscarriage, ectopic pregnancy and benign lesions in the lower genital tract. Less commonly it may be the presenting symptom of hydatidiform mole or cervical malignancy.

Spontaneous miscarriage

The term miscarriage is normally used in preference to spontaneous abortion because of the association of the latter term with induced abortion. It is defined as the termination of pregnancy prior to 24 weeks’ gestation or a fetal weight of <500 g. In practice, with fetal survival rates now of up to 50% at 23 weeks, the management of these babies can best be considered as part of the care of other extremely premature infants born before 26 weeks.

Incidence

A total of 15–20% of clinical pregnancies end in miscarriage. If all women who have had biochemical evidence of pregnancy (i.e. a positive serum hCG) are included, the pregnancy loss rate is as high as 30%. The majority of miscarriages occur prior to 13 weeks’ gestation, although 1–2% occur between 13 and 24 weeks (Stirrat 1990).

The aetiology of miscarriage

In many cases no definite cause can be found for miscarriage. It is important to identify this group as the prognosis for future pregnancies is generally better than average (Regan & Rai 2000).

Genetic abnormalities

Up to 50% of sporadic miscarriages are associated with chromosomal abnormalities which result in failure of development of the embryo. The most common chromosomal defects are autosomal trisomies, which account for half the abnormalities, and polyploidy or monosomy X, which account for a further 20% each. Although chromosome abnormalities are common in sporadic miscarriage, parental chromosomal abnormalities are present in only 3–5% of partners presenting with recurrent pregnancy loss.

Endocrine factors

Progesterone is essential for the maintenance of a pregnancy, and early failure of the corpus luteum may lead to miscarriage. However, it is difficult to be certain whether falling plasma progesterone levels represent a primary cause of miscarriage or whether they are a result of a failing pregnancy. The prevalence of polycystic ovarian syndrome (PCOS) is significantly higher in women with recurrent miscarriage than in the general population. Women with poorly controlled diabetes and untreated thyroid disease are at higher risk of miscarriage and fetal malformation.

Maternal illness and infection

Infections such as syphilis, listeria monocytogenes, mycoplasma and Toxoplasma gondii and severe maternal febrile illnesses associated with infections, such as influenza, pyelitis and malaria predispose to miscarriage. The presence of bacterial vaginosis has been reported as a risk factor for preterm birth and second, but not first trimester, miscarriage (Hay et al 1994). Other severe illnesses involving the cardiovascular, hepatic and renal systems are also associated with increased rates of miscarriage.

Abnormalities of the uterus

Uterine anomalies, such as a bicornuate uterus or subseptate uterus, can be demonstrated in 15–30% of women experiencing recurrent miscarriages. There is an increased frequency of early pregnancy loss in the presence of submucosal fibroids (Benson et al 2001). Following damage to the endometrium and inner uterine walls, the surfaces may become adherent, thus partly obliterating the uterine cavity (Asherman syndrome). The presence of these synechiae may lead to recurrent miscarriage.

Cervical incompetence

Cervical incompetence results in painless dilatation of the cervix, spontaneous rupture of the membranes and miscarriage or early pre-term birth. The diagnosis has historically been made on the basis of the history of previous late pregnancy loss. However, ultrasound examination is being used increasingly to identify where there is an increased risk of premature cervical dilatation. The key feature is shortening of the cervical canal to <25 mm and funneling of the internal cervical os. Cervical incompetence may be associated with other congenital abnormalities of the genital tract but most commonly results from physical damage caused by mechanical dilatation of the cervix or by damage inflicted during childbirth.

Autoimmune factors and thrombophilic defects

The antiphospholipid antibodies lupus anticoagulant (LA) and anticardiolipin antibody (aCL) are present in 2% of women with normal reproductive histories but 15% of women with recurrent miscarriage. Without treatment the live birth rate in women with primary antiphospholipid syndrome may be as low as 10%. Defects in the natural inhibitors of coagulation – antithrombin III, protein C and protein S – are more common in women with recurrent miscarriage. The majority of cases of activated protein C deficiency are secondary to a mutation in the factor V (Leiden) gene.

Pregnancy loss in these conditions is thought to be due to thrombosis of the uteroplacental vasculature and impaired trophoblast function. In addition to miscarriage there is an increased risk of intrauterine growth restriction, pre-eclampsia and venous thrombosis.

Alloimmune factors

Research into the possibility of an immunological basis of recurrent miscarriage has generally explored the possibility of a failure to mount the normal protective immune response or if the expression of relatively non-immunogenic antigens by the cytotrophoblast may result in rejection of the fetal allograft. There is evidence that unexplained spontaneous miscarriage is associated with couples who share an abnormal number of HLA antigens of the A, B, C and DR loci (Beydoun & Saftlas 2005). Despite attempts to treat women with paternal lymphocytes, which initially appeared to reduce the incidence of recurrent miscarriage, subsequent studies have failed to confirm the initial findings.

Clinical presentation

Spontaneous miscarriage progresses through a number of stages with clinical symptoms of vaginal bleeding and lower abdominal pain.

Threatened miscarriage

The presence of bleeding from the uterus in an ongoing early pregnancy is described as a threatened miscarriage. Uterine size is normally consistent with the estimated gestation and the cervical os is closed. Lower abdominal pain is either minimal or absent. Some 80% of women presenting with a threatened miscarriage will continue with the pregnancy.

Inevitable/incomplete miscarriage

In inevitable miscarriage there is usually increasing abdominal pain associated with heavier vaginal bleeding. The cervix opens, and eventually products of conception are passed into the vagina. However, if some of the products of conception are retained, then the miscarriage remains incomplete.

Complete miscarriage

An incomplete miscarriage may proceed to completion spontaneously, when the pain will cease and vaginal bleeding will subside with involution of the uterus.

Miscarriage with infection

During the process of miscarriage – or after therapeutic termination of a pregnancy – infection may be introduced into the uterine cavity. The clinical findings are similar to those of incomplete miscarriage with the addition of uterine and adnexal tenderness. The vaginal loss may become purulent and the patient pyrexial. In cases of severe overwhelming sepsis, endotoxic shock may develop with profound and sometimes fatal hypotension. Other manifestations include renal failure, disseminated intravascular coagulopathy and multiple petechial haemorrhages. Organisms which commonly invade the uterine cavity are Escherichia coli, Streptococcus faecalis, Staphylococcus albus and aureus, Klebsiella, and Clostridium welchii and C. perfringens.

Missed or silent miscarriage

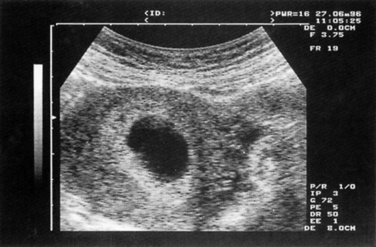

Early fetal demise occurs when a pregnancy is identified within the uterus on ultrasound, but despite a fetal pole being visible no fetal heartbeat is seen. In anembryonic pregnancy a gestational sac is seen on ultrasound but there is no evidence of a fetus or fetal parts (Fig. 19.1). There is usually some pain and bleeding and the uterus does not increase in size.

Recurrent miscarriage

Recurrent miscarriage is defined as three or more successive pregnancy losses prior to viability. The incidence of 1% is higher than would be expected by chance given that 15–20% of pregnancies miscarry suggesting that there are persistent factors operating in successive pregnancies to increase the risks of pregnancy loss. However, it is important to remember that after two consecutive miscarriages the likelihood of a successful third pregnancy is still around 80%. Even after three consecutive miscarriages, there is still a 55–75% chance of success.

Diagnosis

An initial clinical assessment involves determining haemodynamic status and general condition for evidence of blood loss. Distension of the cervical canal by products of conception in an incomplete miscarriage can cause profound vagal response resulting in hypotension and bradycardia (cervical shock).

Where there is evidence of haemodynamic compromise the key differential diagnosis will be of ruptured ectopic pregnancy. Although there is often considerable lower abdominal pain associated with miscarriage there is not normally evidence of peritonism on abdominal examination.

A vaginal examination to assess whether the cervix is open and to look for the presence of products of conception will distinguish an inevitable or incomplete from a threatened miscarriage.

Transvaginal ultrasound will be required for the majority of women presenting with bleeding in early pregnancy and has a high predictive value for the confirmation of miscarriage. In approximately 10% of women with intrauterine pregnancies viability will be uncertain at the first assessment. This occurs when there is no evidence of a yolk sac or fetus and the gestation sac is <20 mm or there is a fetal pole of <6 mm with no evidence of fetal cardiac activity. In these cases it will be necessary to repeat the scan a week later to confirm the diagnosis of viability or miscarriage (Fig. 19.1).

For most women presenting with bleeding, urine based human chorionic gonadotrophin (hCG) tests are sensitive enough to confirm pregnancy within 9–10 days of conception. The use of serial hCG measurements is mainly of value in distinguishing miscarriage from ectopic pregnancy. Serum hCG levels double approximately every 48 hrs in 85% of normal intrauterine pregnancies between 4 and 6 weeks’ gestation.

Treatment options

For women with threatened miscarriage there is no specific treatment except reassurance that once viability has been confirmed the prognosis for ongoing pregnancy is usually good. There is no evidence that bed rest alters the risk of further bleeding. Where complete miscarriage has occurred no further treatment is indicated other than appropriate resuscitation and replacement of blood loss if indicated. Where there is evidence of retained products of tissue the options include expectant management, medical treatment or surgical uterine evacuation.

Surgical evacuation

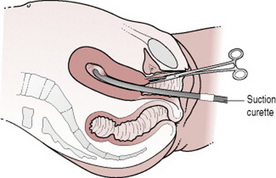

Surgical uterine evacuation of retained products of conception (ERPOC) involves the removal of tissue by suction curettage of the uterine cavity under general or local anaesthetic (Fig. 19.2). Until recently, it was standard treatment for all women with miscarriage on the assumption that retained tissue increases the risk of infection and bleeding. In fact, if anything, infection rates are lower in women who are managed expectantly or medically (Demetroulis et al 2001). Despite this up to a third of women express a strong preference for surgical management once the diagnosis of miscarriage has been confirmed (Hindshaw 1997). Clinical indications for ERPOC include persistent excessive bleeding, haemodynamic instability, evidence of infected retained tissue and suspected gestational trophoblastic disease. Where infection is suspected antibiotic treatment should be given for 12–24 hrs before surgery. Preoperative treatment with prostaglandins makes it easier to dilate the cervix and reduces the risk of bleeding and cervical/uterine trauma.

Figure 19.2 Surgical evacuation of retained products of conception.

(From Symonds E M, Symonds I 2003 Essential Obstetrics and Gynaecology, 4th edn. Churchill Livingstone, Edinburgh.)

Complications of surgery include uterine perforation, cervical tears, intra-abdominal trauma, intrauterine adhesions and bleeding. The overall incidence of serious morbidity is similar to that for surgical termination of pregnancy at 1–2%.

Women who have lower genital tract infections with chlamydia, gonorrhoea or bacterial vaginosis are at increased risk of pelvic inflammatory disease following surgical evacuation. Screening for chlamydia by urinary polymerase chain reaction (PCR) or endocervical swabs should be offered to women undergoing surgical management. The routine use of antibiotic prophylaxis prior to surgery has not been shown to reduce the incidence of postoperative pelvic inflammatory disease.

Expectant management

The natural history of most cases of miscarriage will be the spontaneous passage of products of conception. Waiting for this to happen is an effective and acceptable alternative to surgery for women where there is no infection or heavy bleeding. It is important that women who choose this option are aware that complete resolution may take several weeks, particularly where there is an intact gestation sac. Expectant management is more likely to be successful in incomplete miscarriage (94%; range 80–100%) than missed miscarriage (28%; range 14–47%) (Graziosi et al 2004).

Medical management

Various treatment regimes using prostaglandins with or without antiprogesterone have been described. Reported efficacy rates vary from 13–96%. Success rates for medical treatment vary according to the type of miscarriage, gestation, sac size (if present), total dose of prostaglandin and route of administration. Success rates for incomplete miscarriage are comparable to surgical treatment with equal patient satisfaction and lower rates of pelvic infection (Demetroulis et al 2001). Potential complicating factors are increased pain and blood loss and duration of bleeding.

Medical and expectant management can be undertaken on an outpatient basis. It is important that this is supported by access to 24 hrs telephone advice and emergency admission if required.

Anti-D immunoglobulin

Rhesus negative women who are non-sensitized should receive Anti-D immunoglobulin following any bleeding in pregnancy after 12 weeks’ gestation including threatened miscarriage. In pregnancies <12 weeks anti-D should be given where the bleeding is heavy or associated with pain or after medical or surgical evacuation of the uterus. The discharge documentation should state whether anti-D was given (RCOG 2002).

Recurrent miscarriage

Recurrent miscarriage should be investigated by examining the karyotype of both parents and, if possible any fetal products. Maternal blood should be examined for lupus anticoagulant and anticardiolipin antibodies on at least two occasions, 6 weeks apart. An ultrasound scan should be arranged to assess ovarian morphology for polycystic ovarian syndrome (PCOS) and the uterine cavity (RCOG 2003). Women with persistent lupus anticoagulant and anticardiolipin antibodies can be treated with low-dose aspirin and heparin during subsequent pregnancies (Rai et al 1996). Those with karyotypic abnormalities should be referred to a clinical geneticist. Cervical cerclage carried out at 14–16 weeks in cases of cervical incompetence reduces the incidence of pre-term birth but has not been shown to improve fetal survival.

Organization of care

The efficiency of service and quality can be improved by the use of dedicated Early Pregnancy Assessment Units (EPAU). Admission to hospital can be avoided in 40% of cases and length of stay reduced in a further 20% (Bigrigg & Read 1991). Direct access should be available to GPs and selected patients such as those who have had a previous ectopic pregnancy or recurrent miscarriage. Facilities for transvaginal ultrasound scanning and rapid access to rhesus antibody testing and serum human chorionic gonadotrophin (hCG) estimation should be available. Except where bleeding is heavy or ectopic pregnancy suspected most women can be give an appointment to be assessed in the clinic during the day reducing the need for out-of-hours admission. These units function best when dedicated nursing staff use established diagnostic and therapeutic algorithms of care.

Psychological aspects of miscarriage

Miscarriage is often not regarded medically as ‘serious’ and is usually not investigated further when it occurs for the first time. As a result, many women do not receive an explanation of their loss. There is no evidence to associate miscarriage with an overall increased risk of psychiatric morbidity. However, feelings of anger, grief and guilt are common and almost half of all women are considerably distressed at 6 weeks following miscarriage.

Women who lose pregnancies in the second trimester face the same risks of postpartum ‘mood disorder’ as women in the normal puerperium. Grief reactions are usually more severe and may persist for up to 6 months following the loss of their pregnancy (see Ch. 38). (see Box 19.1 for key points)

Ectopic pregnancy

The term ‘ectopic pregnancy’ refers to any pregnancy occurring outside the uterine cavity (see Box 19.2). Ectopic pregnancy occurs in 1 in 100 pregnancies in the UK and accounted for 3% of pregnancy related deaths between 1994 and 1996. Between 1973 and 1996, the number of ectopic pregnancies per 1000 pregnancies increased from 4.9 to 11.5, while mortality fell from 16 to 4/10 000 cases (DoH 1998, Lewis & Drife 2001). The last 20 years have also seen major changes in both the diagnosis and treatment of the disease.

Box 19.2 Summary of key points on ectopic pregnancy

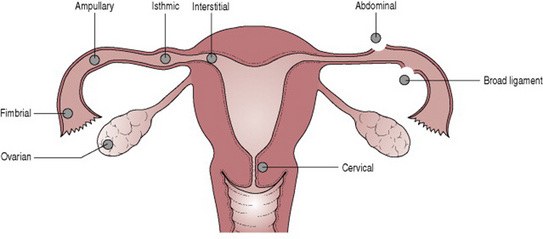

Pathology

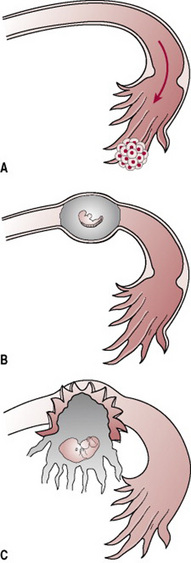

The commonest site of extrauterine implantation is the uterine tube, usually in the ampullary region. Ectopic implantation may also occur on the ovary, in the abdominal cavity or in the cervical canal (Fig. 19.3). Abdominal pregnancy may result from direct implantation of the conceptus or it may result from extrusion of a tubal pregnancy with secondary implantation in the peritoneal cavity. As with normal pregnancy the conceptus produces hCG, which maintains the corpus luteum and the production of oestrogen and progesterone. This causes the uterus to enlarge and the endometrium to undergo decidual change.

Figure 19.3 Sites of implantation of ectopic pregnancy.

(From Symonds E M, Symonds I 2003 Essential Obstetrics and Gynaecology, 4th edn. Churchill Livingstone, Edinburgh.)

Trophoblastic cells invade the wall of the tube and erode into blood vessels of the mesosalpinx. This process will continue until the pregnancy ruptures into the abdominal cavity or the broad ligament, or the embryo dies, thus resulting in a tubal mole. Under these circumstances, absorption or tubal miscarriage may occur. Expulsion of the embryo into the peritoneal cavity or partial miscarriage may also occur with continuing episodes of bleeding from the tube (Fig. 19.4). Vaginal bleeding occurs as a result of shedding of the decidual lining of the endometrium and progesterone levels fall with the failing pregnancy.

Predisposing factors

The majority of cases of ectopic pregnancy have no identifiable predisposing factor, but a previous history of ectopic pregnancy, sterilization, pelvic inflammatory disease and sub-fertility all increase the likelihood of an ectopic pregnancy. The increased risk for an intrauterine device (IUCD) applies only to pregnancies that occur despite the presence of the IUCD. Because of their effectiveness as contraceptives ectopic rates per year in IUCD users are lower than in women not using contraception (Table 19.1).

Table 19.1 Risk factors and associated relative risk of ectopic pregnancy

| Risk factor | Relative risk |

|---|---|

| Previous ectopic pregnancy | 10 |

| Failed IUCD | 10 |

| Failed sterilization | 9 |

| Previous tubal surgery | 4.5 |

| Previous pelvic inflammatory disease | 4 |

Clinical presentation

Acute presentation

The ‘classical’ pattern of symptoms includes amenorrhoea, lower abdominal pain and vaginal bleeding. The abdominal pain is typically of sudden onset starting on one side of the lower abdomen, but rapidly becomes generalized as blood loss extends into the peritoneal cavity. Sub-diaphragmatic irritation by blood produces referred shoulder tip pain and discomfort on breathing. There may be episodes of syncope.

The findings on clinical examination are hypotension, tachycardia and signs of peritonism including abdominal distension, guarding and rebound tenderness. On pelvic examination the cervix is closed and acutely tender when moved (cervical excitation) because of irritation of the pelvic peritoneum caused by the bleeding. This type of acute presentation occurs in no more than 25% of cases.

Subacute presentation

The majority of ectopic pregnancies present less acutely and some or all of the classic symptoms of pain, bleeding and amenorrhoea may be absent (Sperov et al 1994). Typically, there is a history of amenorrhoea or of an abnormally light last ‘period’ followed by irregular vaginal bleeding and abdominal pain. Any woman who develops lower abdominal pain following an interval of amenorrhoea should be assessed for a possible ectopic pregnancy. In its subacute phase, it may be possible to feel a mass in one fornix on vaginal examination although this should be undertaken with care because of the risk of provoking rupture of the ectopic pregnancy.

Diagnosis

While the diagnosis of the acute ectopic pregnancy rarely presents a problem, diagnosis in the subacute phase may be much more difficult. The commonest diagnosis to be made in error on clinical diagnosis is threatened or incomplete miscarriage. It may also be confused with complications of ovarian cysts or acute salpingitis. Because bleeding into the peritoneum can cause bowel irritation maternal deaths have been reported when the diagnosis has been delayed in patients presenting with symptoms of abdominal pain and diarrhoea (DoH 1998). The overall accuracy of clinical diagnosis is only 50% (Ling & Stovall 1994).

The high sensitivity of modern immunoassays for hCG (98% for urine and 100% for serum) (Sperov et al 1994) mean that a negative serum hCG will effectively exclude ectopic pregnancy. It should be possible to visualize a normal intrauterine pregnancy on transvaginal ultrasound when the serum level of hCG is >1500 IU/L (6000–6500 IU/L for transabdominal), although in multiple pregnancy this level may be higher. A rise of <66% in the serum hCG between two levels taken 48 hrs apart is associated with >80% of ectopic pregnancies (Kadar et al 1981) but is also seen in non-viable intrauterine pregnancies and in up to 15% of normal pregnancies (Sperov et al 1994).

The main value of ultrasound is to confirm intrauterine pregnancy. Confirmation of an intrauterine pregnancy does not exclude heterotopic pregnancy, which although rare in spontaneous conceptions (1/3000–4000), can be seen in up to 3% of pregnancies resulting from assisted reproduction. Ultrasound may also provide direct evidence of ectopic pregnancy (Table 19.2) with the commonest finding being an extraovarian solid tubal mass (Atri et al 1996) and free fluid in the peritoneal cavity. The combination of serial serum hCG measurement and transvaginal ultrasound has a sensitivity and specificity for the diagnosis of ectopic pregnancy that is comparable with laparoscopy (Sadek & Schiotz 1995).

Table 19.2 Features of intrauterine and ectopic pregnancy on transvaginal ultrasound

| Intrauterine pregnancy | Ectopic pregnancy |

|---|---|

| Intrauterine gestation sac (4–5 weeks) | Empty uterus |

| Yolk sac (5–6 weeks) | Poorly defined tubal ring with fluid in Pouch of Douglas |

| Double decidual sign (5 weeks) | Pseudosac in uterus |

| Fetal heartbeat (7 weeks) | Tubal ring with extrauterine heartbeat |

Sadek & Schiotz 1995, Dodson 1991.

Laparoscopy has been the mainstay of diagnosis for the last 30 years. False negatives occur in 3–4% of cases and false positives in up to 5% (Ling & Stovall 1994), with interpretation being especially difficult in very early pregnancy and in the presence of previous pelvic pathology. Using algorithms incorporating quantitative hCG measurements, transvaginal ultrasound and clinical symptoms allows earlier diagnosis, results in fewer ruptured ectopics and reduces the need for diagnostic laparoscopy (especially those done out-of-hours) (Ling & Stovall 1994). Furthermore, the diagnostic accuracy of laparoscopy itself is improved when used together with the hCG and ultrasound results.

Surgical treatment

Laparotomy is indicated in the haemodynamically compromised patient and may be indicated in obese patients or those with extensive pelvic adhesions or haemoperitoneum depending on the experience and training of the operator in laparoscopic surgery.

The advantages of laparoscopic compared with open surgery include lower blood loss and reduced need for postoperative pain relief. Mean duration of hospital stay is 50% less than for open surgery (Vu et al 1996) and there are similar or greater reductions in the time to return to normal activity.

Whether the laparotomy or laparoscopy is used there are two main options for surgical removal of the ectopic: partial salpingectomy (removal of part of the tube) or salpingotomy (leaving the tube in place and removing the ectopic through an incision in the wall of the tube). Salpingotomy is associated with a higher rate of subsequent intrauterine pregnancy than salpingectomy but also results in a higher rate of recurrent ectopic pregnancy. Of those women who attempt to conceive following salpingotomy for ectopic pregnancy, 61% achieve intrauterine pregnancy and 15% have further ectopic pregnancies (Yao & Tulandi 1997). It must be remembered that other factors influence subsequent fertility rates as much, if not more than the surgical treatment used. In particular, these are a previous history of infertility and the condition of the contralateral tube at the time of surgery (Pouly et al 1991, Yao & Tulandi 1997).

Where the tube is not removed, there is a risk that some gestational tissue may be left in place and continue to develop. Follow-up with weekly hCG measurements is therefore necessary after conservative surgery and it may take up to 10 weeks for these to return to normal.

Salpingectomy remains the treatment of choice where there is uncontrolled bleeding or a second ectopic pregnancy in the same tube. It should also be discussed where childbearing is complete or for a severely damaged tube.

Expectant management

A proportion of haemodynamically stable patients with falling hCG levels will show spontaneous resolution of ectopic pregnancy. The overall success rate of this approach is 69%, although higher rates have been reported where the initial hCG was <200 IU/L (Yao & Tulandi 1997). An hCG level of >2000 is an absolute contraindication to expectant management. Furthermore, tubal rupture has been reported even in low and falling levels of hCG. The efficacy and safety of systemic methotrexate make this a more attractive alternative to surgical management.

Medical management

Medical treatment has the advantage of avoiding the need for surgery with concomitant reductions in cost and surgical morbidity. The commonest drug used is methotrexate, an antimetabolite that interferes with the synthesis of DNA, given i.m. as a single dose of 1 mg/kg body weight or 50 mg/m2. Multiple dose regimes have higher success rates but are associated with more side-effects. Weekly follow-up with serum hCG levels is required. Success rates of up to 92% have been reported but 5% of patients will require surgery for failed treatment. Subsequent intrauterine and ectopic pregnancy rates appear comparable with those reported for surgical treatment (54% and 8%, respectively) (Slaughter & Grimes 1995).

The success of medical treatment is related to the serum hCG level, size of the ectopic and the presence of fetal cardiac activity Although significant adverse effects are uncommon after systemic administration of methotrexate, up to 60% of patients experience increased abdominal pain 6–7 days after treatment (Yao & Tulandi 1997). Good patient compliance is essential for non-surgical treatment and selection of suitably reliable individuals is as important as the size of the ectopic itself.

Although promising, the clinical role for methotrexate, given the availability of highly effective and safe conservative surgical treatments, remains unproven. It can be considered as an alternative to surgical treatment where the serum hCG is <2000 IU/L and the ectopic <2 cm with no fetal cardiac activity seen (Shalev et al 1995).

Trophoblastic disease

This is a group of disorders characterized by abnormal placental development. The chorionic villi are hydropic with vacuolation of the placenta and destruction of the normal stroma.

Incidence

Trophoblastic disorders affect 1.5 per 1000 pregnancies in the UK (Bagshawe et al 1986). There is considerable geographic variation in incidence, the highest being in countries of the Far East.

Pathology

Benign trophoblastic disease is usually either a complete hydatidiform mole, where there is no evidence of an embryo, or a partial hydatidiform mole which may be associated with an embryo (usually abnormal) (Szulman 1988). Other types of trophoblastic disease include invasive moles, placental site reactions, trophoblastic tumours and hydropic change.

Malignant trophoblastic disease (choriocarcinoma) complicates approximately 3% of complete moles although in 50% of cases of choriocarcinoma there is no history of immediately preceding trophoblastic disease. It may also occur following normal pregnancy. Blood-borne metastases may occur locally in the vagina but most commonly appear in the lungs.

Aetiology

Trophoblastic disease is thought to arise by fertilization of the oocyte by a single diploid spermatozoon or by two haploid sperm. If this occurs in the absence of any female nuclear material the resulting conceptus pregnancy is a complete mole with a diploid karyotype (46XX). A partial mole is thought to occur where fertilization occurs with the maternal chromosome and the conceptus is triploid (69XXX or 69XXY). Older women and those with a previous history of trophoblastic disease or an A type blood group are at increased risk (Lawler et al 1991).

Presentation

Molar pregnancy most commonly presents as bleeding in the first half of pregnancy, and is usually diagnosed initially as a threatened miscarriage. Occasionally, the passage of a ‘grape-like’ tissue raises a clinical suspicion but the diagnosis is normally made on ultrasound or after uterine evacuation. The uterus is larger than dates in about half the cases. Associated conditions include severe hyperemesis, pre-eclampsia and unexplained anaemia and ovarian cysts. The high circulating levels of hCG have a TSH like action and can cause clinical thyrotoxicosis. Choriocarcinomas may present with the symptoms of distant metastases (cerebral, pulmonary).

Diagnosis

A ‘snowstorm’ appearance with multiple highly reflective echoes and areas of vacuolation within the uterine cavity on ultrasound examination usually suggests molar disease. In a partial mole, a gestation sac with a fetus may also be present. Other imaging, such as chest X-rays, CT or MRI may be indicated to exclude pulmonary or cerebral metastases if choriocarcinoma is suspected. The diagnosis of trophoblastic disease is confirmed by histological examination of products of conception removed at the time of uterine evacuation.

Management

Once the diagnosis is established, the pregnancy is terminated by suction curettage. Occasionally, repeat evacuation may be required if there is persistent bleeding or a raised serum hCG but routine second evacuation is not helpful. All cases of molar pregnancy in the UK should be registered with one of the trophoblastic disease screening centres who will arrange follow-up.

The aim of follow-up is to detect persistent trophoblastic disease and choriocarcinoma. Because all trophoblastic tumours produce hCG patients can be monitored by measurement of urinary or serum hCG levels. Levels are checked fortnightly until the serum level is <2 IU/L, and then monthly for 6 months following this if the hCG is negative within 6 weeks of treatment. If the hCG takes longer than 6 weeks to become negative, follow-up is continued for a further 12 months (Newlands et al 2001, RCOG 2004). Patients should be counselled to avoid pregnancy until 6 months after the serum hCG levels fall to normal.

There is a 0.8–2.9% risk of recurrence in subsequent pregnancies after one mole, 15–28% after two moles and serum hCG levels should be checked 6 weeks after any subsequent pregnancy.

Chemotherapy with methotrexate (with folinic acid rescue) is indicated for a rising hCG level in the absence of a new pregnancy, an hCG persistently >20 000 IU/L by 4 weeks after treatment, persistent symptoms or evidence of metastatic disease. Subsequent fertility does not appear to be impaired by chemotherapy and there does not seem to be an increased incidence of other chromosomal abnormalities.

Other causes of bleeding in early pregnancy

Vaginal bleeding in pregnancy may occur from other lesions in the lower genital tract in the same way as in non-pregnant women of the same age. These may be normal physiological variants such as cervical ectropion, benign or malignant neoplastic lesions or infections.

Cervical ectropion (eversion)

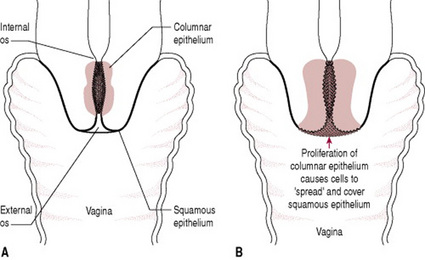

This condition is commonly and erroneously known as cervical erosion. Following puberty and increasingly in pregnancy high levels of oestrogen cause proliferation of columnar epithelial cells, found in the cervical canal. As a result the area of columnar epithelium extends beyond the external cervical os onto the vaginal surface of cervix giving a dark red appearance (Fig. 19.5).

Figure 19.5 Cervical ectropion: (A) columnar epithelium becomes profuse in pregnancy; (B) cervical eversion caused by growth of columnar epithelial cells.

Hyperactivity of the endocervical cells increases the quantity of vaginal discharge. There is only a single layer of epithelial cells covering the underlying stroma and capillaries in columnar epithelium so this tends to be more friable and liable to bleed. This may cause intermittent bloodstained loss, or spontaneous bleeding, particularly following sexual intercourse. The ectropion will usually reduce in size during the puerperium and normally requires no treatment in pregnancy.

Cervical polyps

These are small, vascular pedunculated growths consisting of squamous or columnar epithelium covering a core of connective tissue and blood vessels. They are thought to arise by hyperplasia of the underlying epithelium and can arise from either the cervical canal or the ectocervix. They may be asymptomatic or cause bleeding during pregnancy. They can be visualized on speculum examination and no treatment is required during pregnancy, unless bleeding is profuse or a cervical smear suggests malignancy.

Carcinoma of the cervix

The incidence of cancer in pregnancy is 1 in 6000 live births (Lewis & Drife 2001). Carcinoma of the cervix is the most frequently diagnosed cancer in pregnancy. Some 80% of cases detected in pregnancy are diagnosed in the first or second trimester. The disease is usually squamous cell carcinoma although up to 40% of cases now reported are adenocarcinomas.

Aetiology

Cervical neoplasia is strongly associated with infection with some serotypes of human papilloma virus (HPV). Two serotypes, 16 and 18, are found in >70% of cases of invasive disease. HPV infection is common (80% of women will have some evidence of exposure by the age of 50) and the reasons that some women develop neoplasia while others exposed to the virus do not is not clear, although it does appear related to how long the virus persists in the epithelium (NHSCSP 2005, Schlecht et al 2001).

Clinical presentation and diagnosis

The commonest presenting symptom is blood stained vaginal discharge. The diagnosis may be suspected on routine cervical screening or because of the appearance of the cervix on speculum examination. Confirmation of the diagnosis is made by colposcopy and cervical biopsy.

Treatment

Treatment depends on the stage of the disease and gestation.

Cone biopsy under general anaesthesia involves excision of cervical tissue and is both a diagnostic tool and a treatment for early stage disease. The cervix is highly vascular in pregnancy so that the risk of haemorrhage is high, and there is the possibility of causing the mother to miscarry.

If the changes to the cervix are advanced and diagnosis is made in the first or second trimester, the mother may have to make a choice as to whether to terminate the pregnancy in order to undergo treatment. If diagnosis is made later in pregnancy, a decision to deliver the fetus may be taken to allow the mother to commence treatment.

Cervical intraepithelial neoplasia

Cervical intraepithelial neoplasia (CIN) is the precursor to invasive cancer of the cervix and is normally diagnosed by colposcopy following referral for an abnormal Papanicolaou smear (Pap smear). The condition is asymptomatic and treatment can usually be deferred until after the pregnancy. For high-grade CIN, follow-up with colposcopy during the pregnancy is normally carried out to check for any signs of invasive disease.

Vaccination against HPV 16 and 18 became available in 2007 for women aged up to 26 and appears to be effective in preventing the development of CIN associated with these serotypes. The vaccines are not licensed for use during pregnancy. Vaccination will not obviate the need for cervical screening but should substantially reduce the risk of developing CIN/cervical cancer.

Midwives have a role in explaining the value of regular smear tests to mothers. National guidelines in the UK recommend that every woman between the ages of 25 and 49 has a cervical smear test every 3 years, and from 50–64 every 5 years. Where there is no evidence of a recent smear having been carried out, it may be appropriate for a smear to be taken during pregnancy. Simple explanations about the procedure can help overcome anxieties about the smear test. Cervical screening may be carried out at the 6-week postnatal examination. For women under the age of 26 this should now also be an opportunity to discuss the benefits of vaccination against HPV. Midwives acting as advocates for disadvantaged mothers should be aware that women who are at risk include those with learning disabilities, those from minority ethnic and those from indigenous populations. This group of women are vulnerable through sexual activity, sexual abuse and smoking and are less likely to access healthcare (NHSCSP 2000).

Lower genital tract infection

Inflammatory change in the cervix (cervicitis) or vagina can present with increased vaginal discharge or bleeding in pregnancy. Women in the reproductive age group, especially those aged 16–25 are at greatest risk of sexually transmitted infections such as Chlamydia Trachomatis and Neisseria Gonorrhoea. Non-STIs including candidiasis and bacterial vaginosis may also be associated with increased susceptibility of the vaginal mucosa to bleeding. Screening for chlamydia with urinary PCR should be included in the investigation of women presenting with lower genital tract bleeding (see also Ch. 23).

Nausea and vomiting in early pregnancy

Nausea and vomiting are common symptoms in early pregnancy usually starting between 4 and 10 weeks’ gestation, and resolving before 20 weeks. Hyperemesis gravidarum is defined as persistent pregnancy-related vomiting associated with weight loss of >5% of body mass and ketosis. Affecting 0.3–3% of all pregnant women, this is associated with dehydration, electrolyte imbalance and thiamine deficiency. (see Box 19.3)

Box 19.3 Nausea and vomiting in pregnancy

Aetiology

The aetiology of hyperemesis is uncertain, with multifactorial causes, such as endocrine, gastrointestinal and psychological factors proposed. Hyperemesis occurs more often in multiple pregnancy and hydatidiform mole, suggesting an association with the level of hCG. Although transient abnormalities of thyroid function are common this does not require treatment in the absence of other clinical features of hyperthyroidism. Infection with Helicobacter pylori, the organism implicated in gastric ulcers, may also contribute (Frigo et al 1998). Women with a previous history of hyperemesis are likely to experience it in subsequent pregnancies (Snell et al 1998).

Diagnosis

It is important to ask about the frequency of vomiting, trigger factors and whether any other members of the family have been affected. A history of vomiting in a previous pregnancy or outside pregnancy should be sought. Smoking and alcohol can both exacerbate symptoms, and should be enquired of. If this pregnancy resulted from fertility treatment, or there is a close family history of twins, a multiple pregnancy is more likely. Early pregnancy bleeding or a past history of trophoblastic disease may point to a hydatidiform mole.

The clinical features of dehydration include tachycardia, hypotension and loss of skin turgor. Causes of vomiting not due to pregnancy, such as thyroid problems, urinary tract infection or gastroenteritis, need to be excluded so the abdomen should be palpated for areas of tenderness, especially in the right upper quadrant, hypogastrium and renal angles. A dipstick analysis of the urine for ketones, blood or protein should be performed.

Routine investigations should include full blood count, electrolytes, liver and thyroid function tests. Elevated haematocrit, alterations in electrolyte levels and ketonuria are associated with dehydration. Urine should be sent for culture to exclude infection and an ultrasound arranged to look for multiple pregnancy or gestational trophoblastic disease.

Management

The impact of nausea and vomiting on the woman and her daily life should not be underestimated. The midwife should enquire of all women attending for early antenatal care whether they are experiencing nausea or vomiting. If the vomiting is mild to moderate, and not causing signs of dehydration then usually, reassurance and advice will be all that is necessary.

A history of persistent, severe vomiting with evidence of dehydration requires admission to hospital for assessment and management of symptoms.

Hypovolaemia and electrolyte imbalance should be corrected by intravenous fluids. These should be balanced electrolyte solutions or normal saline as overly rapid rehydration with 5% dextrose can result in water intoxication.

Thromboprophylaxis with compression stockings and low molecular weight heparin should be considered. Most women will settle in 24–48 hrs with these supportive measures. Once the vomiting has ceased, small amounts of fluid, and eventually food can be re-introduced. It is worthwhile doing this gently. If rushed, many women relapse and require re-admission.

Antiemetic therapy is reserved for those women who do not settle on supportive measures, or who persistently relapse. The use of antiemetics in pregnancy received widespread publicity when links were found between thalidomide and severe malformations of children born to mothers who had taken the drug for morning sickness. Currently antihistamines are the recommended pharmacological first line treatment for nausea and vomiting, no antiemetic being approved for treatment. Metoclopramide and prochlorperazine have not been shown to be teratogenic in man (though metoclopramide is in animals).

Vitamin supplements including thiamine should be given, particularly where hyperemesis has been prolonged. If vomiting continues, and the history is suggestive of severe reflux or ulcer disease, endoscopy can be very valuable. It is a safe technique in pregnancy. If severe oesophagitis is confirmed then appropriate treatment with alginates and metoclopramide can be given. Ulcer disease will require H2 antagonist treatment (ranitidine) or if very severe, omeprazole, though there is limited experience of this in pregnancy.

Very occasionally, women do not settle with a combination of the above measures. Some of these women may improve with steroid therapy, though trials are still ongoing. Women in whom there is liver function derangement may benefit particularly. H2 antagonists must be given in conjunction with the steroid treatment. Parenteral nutrition is necessary for some that develop severe protein/calories malnutrition. Specialized nutrition units can be very helpful in this setting.

If hyperemesis is left untreated, the mother’s condition worsens. Wernicke’s encephalopathy is a complication associated with a lack of vitamin B1 (thiamine). Coma and death have been reported because of hepatic and renal involvement. Termination of pregnancy may reverse the condition and has a place in preventing maternal mortality. Hyperemesis persisting into the third trimester should be further investigated as it may be symptomatic of serious illness such as acute fatty liver of pregnancy (Lewis & Drife 2001).

Abdominal pain in early pregnancy

Abdominal pain is a common presenting symptom for miscarriage and ectopic pregnancy in early pregnancy. As in non-pregnant women, there is a long potential list of other differential diagnoses of causes and in some cases no definitive diagnosis will be reached and management will be symptomatic. This section concentrates on those causes that are specific to the reproductive tract other than miscarriage and ectopic pregnancy and some of the commoner non-gynaecological conditions that can present with pain in early pregnancy.

Retroversion of the uterus

Where the angle between the long axis of the uterus and the axis of the vagina is >180°, the uterus is said to be retroverted. In most cases this causes no problems during pregnancy and corrects spontaneously as the uterus rises out of the pelvis into the abdomen as pregnancy progresses.

Incarceration of the retroverted gravid uterus

If the retroverted uterus fails to rise out of the pelvic cavity by the 14th week, it is said to be incarcerated. The growing uterus is confined within the pelvis, beneath the sacral promontory. Pressure causes abdominal discomfort, and a feeling of pelvic fullness, low abdominal or back pain. Frequency of micturition, dysuria and paradoxical incontinence are the result of the urethra being elongated as the cervix is increasingly displaced. Compression of the bladder neck leads to urinary retention. Urinary stasis can result in infections developing, including pyelonephritis (Myers & Scotti 1995).

On examination, the bladder will be palpable abdominally. Demonstrating effective clinical practice the midwife should explain, and gain consent for catheterization to relieve the retention of urine. An indwelling catheter is used to keep the bladder empty, enabling the uterus to rise out of the pelvis.

Fibroids (leiomyomas)

These are firm, benign tumours of muscular and fibrous tissue, ranging in size from very small to very large. The incidence of detectable fibroids in pregnancy is 1%; the lowest risk being in Caucasian women, but risk increases in Afro-Caribbean women and women over 35-years-old (Lumsden & Wallace 1998).

Although ultrasound monitoring of fibroids has demonstrated that they do not significantly increase in size during pregnancy (Aharoni et al 1988, Davis et al 1990), they do become more vascular and oedematous. Red degeneration of a fibroid occurs when a rapidly growing fibroid occludes its own venous drainage. The central core necroses, and bleeding occurs into the middle. The mother experiences severe abdominal pain that is acute in nature (Katz et al 1989), the affected area is tender on palpation, and she may also have low-grade pyrexia.

Referral for ultrasound scan aids differential diagnosis of the pain, as the relationship between the placental site and the focus of pain can be established. The degeneration can be seen clearly on ultrasound. The pain is normally relieved by rest and analgesia; no other treatment is required (Lumsden & Wallace 1998).

Ovarian cysts

Incidence

Between 1 in 80 and 1 in 300 pregnancies are complicated by the presence of ovarian cysts (Singer 1989). The majority of these will be benign, the commonest being functional ovarian cysts (follicular cysts, corpus luteum). The commonest solid, benign ovarian cysts found in pregnancy are mature cystic teratomas (dermoid cysts). Most cystic neoplasms are epithelial (serous or mucinous cystadenomas). Between 2% and 5% of ovarian cysts in pregnancy will be malignant with an overall incidence of between 1 in 8000 and 1 in 20 000 pregnancies.

Diagnosis

Most lesions are asymptomatic and diagnosed following palpation of an abdominal or pelvic mass or on routine ultrasound scanning for fetal viability or abnormality. Symptoms usually arise as a result of complications, such as torsion or rupture of the cyst causing abdominal pain, nausea, vomiting and local tenderness. Torsion (but not haemorrhage and rupture) is more common in pregnancy and in the puerperium than at other times (complicates 10–15% of tumours). Ultrasound examination should be arranged to distinguish ovarian cysts from other types of pelvic mass. Definitive diagnosis can only be made by removal of the cyst at laparotomy.

Management

Asymptomatic cysts of <10 cm can be left and monitored by ultrasound. They will usually resolve without treatment after birth. It is important to remember that in the first trimester the continuation of the pregnancy is dependant on progesterone produced by the corpus luteum and if this is removed the pregnancy will miscarry unless progesterone supplements are given.

Laparotomy is indicated for cysts that are persistently >10 cm in diameter, are enlarging, or contain abnormal features on ultrasound scan (complex multilocular or solid areas). Unless indicated earlier because of an acute surgical complication of the cyst such as torsion, laparotomy is usually performed during the mid-trimester at 16 weeks (by which time the pregnancy is not dependant on the corpus luteum and miscarriage is less likely). Benign lesions are treated by unilateral cystectomy or salpingo-oophorectomy. Stage I ovarian carcinoma can be treated by unilateral salpingo-oophorectomy providing that there is no obvious invasion of the capsule or involvement of the contralateral ovary and no ascites. Where the diagnosis is made in the second trimester, a decision will need to be made on a case by case basis as to whether to delay treatment to allow the pregnancy to reach viability.

Other causes of abdominal pain in early pregnancy

Urinary tract infection

Lower urinary tract infection is common in pregnancy and should be treated because of the increased risk of ascending infection. Acute pyelonephritis occurs in 1–2% of pregnant women. The clinical features include fever, loin tenderness and urinary frequency. Treatment should be as an inpatient with intravenous antibiotics, fluids and adequate analgesia.

Urolithiasis

Renal colic occurs in 0.03–0.5% of pregnancies. Urinary calculi in pregnancy normally present with sudden onset abdominal pain, which is severe enough to warrant hospital admission, associated with urinary tract infection and haematuria. Ultrasound scan findings of unilateral hydronephrosis or a calcified area are suggestive of renal calculi. The management should be conservative with intravenous fluids, antibiotics and effective analgesia. If a calculus is large enough to cause obstruction then surgery may be required.

Appendicitis

Acute appendicitis complicates about 1/1000 of pregnancies. There is no increase in incidence during pregnancy but mortality is higher. During pregnancy the caecum and appendix are displaced upwards and to the right with advancing gestation. The pain is less well localized and tenderness, rebound and guarding less obvious. This leads to delay in diagnosis and treatment and an increased incidence of perforation (15–20% of cases), peritonitis and sepsis. When perforation occurs, maternal and fetal mortality reaches 17% and 43%, respectively. Early referral for surgical treatment is essential. In the first trimester this can be accomplished laparoscopically.

Cholecystitis

Acute cholecystitis complicates about 1 in 1000 pregnancies. Presentation is with sudden onset of right upper quadrant or epigastric colicky pain with associated nausea, vomiting and fever. Jaundice is uncommon. The diagnosis is made by the clinical features, biochemical tests and the presence of stones in the biliary tree on ultrasound scan. The treatment is by using the appropriate antibiotics, adequate analgesia and fluids. Surgery is indicated during pregnancy where there is associated pancreatitis or recurrent episodes but otherwise is deferred until after the puerperium.

Induced abortion (pregnancy termination)

In the UK, this is carried out in approved centres under the provision of the Abortion Act 1967. This Act requires that two doctors agree that continuation of the pregnancy would either involve greater risk to the physical or mental health of the mother or her other children than termination, or that the fetus is at risk of an abnormality likely to result in it being seriously handicapped. The most recent amendment to the Act (1990) sets a limit for termination under the first of these categories at 24 weeks, although in practice the majority of terminations are carried out prior to 20 weeks (see Box 19.4).

Box 19.4 Indications for termination of pregnancy under the Abortion Act 1967, as amended by Human Fertilization and Embryology Act 1990

All women who are opting to terminate a pregnancy need adequate support and counselling, both before and after the procedure. Social, medical and psychological factors all contribute to the decision.

Methods of termination of pregnancy

All women undergoing termination of pregnancy should be screened for sexually transmitted infection and/ or offered antibiotic prophylaxis. Following termination anti-D immunoglobulin should be given to all Rhesus negative women. All women should be offered follow-up appointment to check that there are no physical problems and contraceptive measures are in place.

Up to 12% of women requesting termination of pregnancy will have active infection with C. trachomatis. In these women, there is a 30% pelvic inflammatory disease if the appropriate antibiotic treatment is not given at the time of surgical termination.

Surgical termination of pregnancy

This is the method most commonly used in the first trimester. The cervix is distended using a series of graduated dilators and the conceptus removed using a suction curette. A variation involving piecemeal removal of the larger fetal parts with forceps (dilatation and evacuation) allows the method to be used for later second-trimester pregnancies. Although most procedures are carried out under general anaesthesia in the UK, the use of local anaesthetic for terminations under 10 weeks is widely used in many countries and reduces the time the patient needs to stay in the hospital or clinic.

Medical termination of pregnancy

This is the method most commonly used for pregnancies after 14 weeks and is increasingly being offered as an alternative to surgical termination in first trimester pregnancies (up to 9 weeks’ gestation). The standard regimes for first trimester termination uses the progesterone antagonist mifepristone (RU 486) given orally followed 36–48 hrs later by prostaglandins administered either orally or as a vaginal pessary. There are several different regimes but all have a success rate of >95%. Second trimester terminations can be performed using vaginal prostaglandins given 3-hourly or as an extra-amniotic infusion through a balloon catheter passed through the cervix. Pre-treatment with mifepristone significantly reduces the time from induction to abortion. After delivery of the fetus, an examination under general anaesthetic may be necessary to remove the placenta.

The mother needs to be cared for in a single room, her privacy being protected at all times. She should be offered information about the process so she is aware of what is happening. Adequate analgesia should be available and supportive staff identified to care for the mother and her family throughout the procedure (Kohner 1995). It may be appropriate for the named midwife to care for the mother during her termination.

Legal abortion should not result in a live birth and feticide may be carried out as part of or prior to the procedure. Amendments implemented in 1991 to the Abortion Act 1967 allowed for the reduction of multiple pregnancies where one or more of the fetuses, but not all, may be terminated (Paintain 1994).

Complications of termination

Early complications include bleeding, uterine perforation (with possible damage to other pelvic viscera), cervical laceration, retained products and sepsis. All the procedures also have a small failure rate (overall rate 0.7/1000). Late complications include infertility, cervical incompetence, isoimmunization and psychiatric morbidity. In the developing world, unsafe abortion is one of the five main causes of direct maternal death (WHO 1997). Septic abortion remains a major complication of an illegal abortion or one carried out in non-sterile conditions.

Psychological sequelae of termination

The majority of women who find themselves with an unwanted pregnancy are very distressed. Despite this, evidence shows that the majority of women do not experience medium- to long-term psychological sequelae following termination for psychosocial reasons. The available evidence is that the rate of psychiatric morbidity following termination of pregnancy decreases. The situation for women having a termination of pregnancy because of fetal abnormality is different. These are usually older women who have a much wanted pregnancy and whose problem has been diagnosed either because of a previous experience or as the result of screening. The decision to terminate the pregnancy is usually reached only after much thought and anguish. The consequence of termination is, therefore, very much like the spontaneous loss of a more advanced pregnancy, that is to say, of a grief reaction. Most late terminations of pregnancy involve the induction of labour and a prolonged process of giving birth. This can be a distressing and traumatic experience, and psychological recovery will be improved by sensitive and compassionate handling by the doctor and midwifery or nursing staff. Their psychosocial recovery may be assisted by granting them the dignity of a naming and burial.

The role of the midwife

Midwives will primarily be caring for mothers for whom termination of pregnancy is an option they are considering as a result of the antenatal screening or diagnostic tests offered.

Within the terms of the Abortion Act 1967, if an individual has a conscientious objection then he or she is not required to assist with abortion. A midwife would normally be required to notify her manager of such an objection before any care was expected. The Act requires practitioners, however, to provide care to prevent harm to the pregnant woman so the exception to this would be in the event of an emergency when conscientious objection does not preclude the midwife from involvement. The midwife otherwise has a duty of care to mothers for whom she is the named midwife. Midwifery practice may involve assisting with blood tests or amniocentesis, the results of which could lead to a termination. The duty of care and exercise of professional accountability means that mothers should be given the necessary information and advice. Professional guidelines require the midwife to care for clients in a non-judgemental manner. This applies when caring for a mother terminating a current pregnancy or a mother who has undergone termination in a previous pregnancy.

Abortion Act Abortion Act. HMSO, London, 1967.

Aharoni A, Reiter A, Golan D, et al. Patterns of growth of uterine leiomyomas during pregnancy. A prospective longitudinal study. British Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology. 1988;95:510-513.

Atri M, Leduc C, Gillett P, et al. Role of endovaginal sonography in the diagnosis and management of ectopic pregnancy. Radiographics. 1996;16(4):755-774.

Bagshawe KD, Dent J, Webb J. Hydatidiform mole in England and Wales 1973–1983. Lancet. 1986;ii:673-675.

Benson CB, Chow JS, Chang-Lee W, et al. Outcome of pregnancies in women with uterine leiomyomas identified by sonography in the first trimester. Journal of Clinical Ultrasound. 2001;29(5):261-264.

Beydoun H, Saftlas AF. Association of human leucocyte antigen sharing with recurrent spontaneous abortions. Tissue Antigens. 2005;65(2):123-135.

Bigrigg MA, Read MD. Management of women referred to early pregnancy assessment unit: care and effectiveness. British Medical Journal. 1991;302:577-579.

Davis JL, Ray-Mazumder S, Hobel CJ, et al. Uterine leiomyomas in pregnancy: a prospective study. Obstetrics and Gynaecology. 1990;75(1):41-44.

Demetroulis C, Saridogan E, Kunde D, et al. A prospective RCT comparing medical and surgical treatment for early pregnancy failure. Human Reproduction. 2001;16:365-369.

Dodson MG. Early ectopic pregnancy. In: Dodson MG, editor. Transvaginal ultrasound. Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone; 1991:165-214.

DoH (Department of Health), Welsh Office, Scottish Home and Health Department, Department of Health and Social Services, Northern Ireland. Why mothers die. Report on Confidential Enquiries into Maternal Deaths in the United Kingdom 1994–1996. London: Stationery Office, 1998.

Frigo P, Lang C, Reisenberger K, et al. Hyperemesis gravidarum associated with Helicobacter pylori seropositivity. Obstetrics and Gynecology. 1998;91(4):615-617.

Graziosi GC, Moi BW, Ankum WM, et al. Management of early pregnancy loss – a systematic review. International Journal of Gynaecology and Obstetrics. 2004;86:337-346.

Hay PE, Lamont RF, Taylor-Robinson D, et al. Abnormal bacterial colonization of the genital tract and subsequent pre-term delivery and late miscarriage. British Medical Journal. 1994;308:295-298.

Hindshaw HKS. Medical management of miscarriage. In: Grudzinskas JG, O’Brien PMS, editors. Problems in early pregnancy: advances in diagnosis and management. London: RCOG press; 1997:284-298.

Human Fertilization and Embryology Act. London: HMSO, 1990.

Kadar N, Caldwell BV, Romero R. A method for screening for ectopic pregnancy and its indications. Obstetrics and Gynecology. 1981;58:162-165.

Katz VL, Dotters DJ, Droegemueller W. Complications of uterine leiomyomas in pregnancy. Obstetrics and Gynecology. 1989;73(4):593-596.

Kohner N. Pregnancy loss and the death of a baby. In: Guidelines for professionals. London: SANDS; 1995.

Lawler SD, Fisher RA, Dent J. A prospective genetic study of complete and partial hydatidiform moles. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. 1991;164(5):1270-1277.

Lewis G, Drife J, editors. Why mothers die. The fifth report of the Confidential Enquiries into Maternal Deaths in the UK 1997–1999. London: RCOG Press, 2001.

Ling FW, Stovall TG. Update on the diagnosis and management of ectopic pregnancy. In: Advances in Obstetrics and Gynecology. Chicago: Mosby Year Book; 1994:55-83.

Lumsden MA, Wallace EM. Clinical presentation of uterine fibroids. Baillière’s Clinical Obstetrics and Gynaecology. 1998;12(2):177-195.

Myers DL, Scotti RJ. Acute urinary retention and the incarcerated, retroverted, gravid uterus. A case report. Journal of Reproductive Medicine. 1995;40:487-490.

Newlands ES, Seckl SJ, Boultbee JE, et al. Gestational trophoblastic tumours. Information for medics. Hydatidiform mole and choriocarcinoma UK information and support service. 2001. Online. Available http://www.hmole-chorio.org.uk, 19 December 2001

NHSCSP (National Health Service Cancer Screening Programme). Good practice in breast and cervical screening for women with learning disabilities. Sheffield: NHSCSP, 2000.

NHSCSP (National Health Service Cancer Screening Programme). The aetiology of cervical cancer. Sheffield: NHSCSP, 2005.

Paintain D. Induced abortion. In: Clements RV, editor. Safe practice in obstetrics and gynaecology. A medico-legal handbook. Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone; 1994:355.

Pouly JL, Chapron C, Manhes H, et al. Multifactorial analysis of fertility after conservative laparoscopic treatment of ectopic pregnancy in a series of 223 patients. Fertility and Sterility. 1991;56:453-460.

Rai R, Clifford K, Regan L. The modern preventative treatment of recurrent miscarriage. British Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology. 1996;103:106-110.

RCOG (Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists). Use of anti-d immunoglobulin for Rh prophylaxis (22). 2002. Online. Available http://www.rcog.org.uk/index.asp?PageID=1972.

RCOG (Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists). The investigation and treatment of couples with recurrent miscarriage (17). 2003. Online. Available http://www.rcog.org.uk/resources/Public/pdf/Recurrent_Miscarriage_No17.pdf.

RCOG (Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists). The management of gestational trophoblastic disease, evidence based guidelines. 2004. Online. Available http://www.rcog.org.uk/index.asp?PageID=519.

Regan L, Rai R. Epidemiology and the medical causes of miscarriage. Best Practice and Research in Clinical Obstetrics and Gynaecology. 2000;14(5):839-854.

Sadek AL, Schiotz HA. Transvaginal sonography in the management of ectopic pregnancy. Acta Obstetrica et Gynecologica Scandinavica. 1995;74:293-296.

Schlecht NF, Kulaga S, Robitaille J, et al. Persistent human papillomavirus as a predictor of cervical intraepithelial neoplasia. Journal of the American Medical Association. 2001;286(24):3106-3114.

Shalev E, Peleg D, Bustan M, et al. Limited role for intratubal methotrexate treatment of ectopic pregnancy. Fertility and Sterility. 1995;63:20-24.

Singer A. Malignancy and premalignancy of the genital tract in pregnancy. In: Turnbull A, Chamberlain G, editors. Obstetrics. Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone; 1989:657-672.

Slaughter JL, Grimes DA. Methotrexate therapy: nonsurgical management of ectopic pregnancy. Western Journal of Medicine. 1995;162:225-228.

Snell LH, Haughey BP, Buck G, et al. Metabolic crisis: hyperemesis gravidarum. Journal of Perinatal and Neonatal Nursing. 1998;12(2):26-37.

Sperov L, Glass RH, Kase NG. Ectopic pregnancy. In: Sperov L, Glass RH, Kase NG, editors. Clinical gynecologic endocrinology and infertility. Baltimore: Williams & Wilkins; 1994:947-964.

Stirrat GM. Recurrent miscarriage I: definition and epidemiology. Lancet. 1990;336:673-675.

Szulman AE. The biology of trophoblastic disease: complete and partial hydatidiform moles. In: Beard RW, Sharp F, editors. Early pregnancy loss, mechanisms and treatment. London: Springer-Verlag; 1988:309-316.

Vu K, Gehlbach DL, Rosa C. Operative laparoscopy for the treatment of ectopic pregnancy in a residency program. Journal of Reproductive Medicine. 1996;41(8):602-604.

WHO. Unsafe abortion: Global and regional estimates of incidence of mortality due to unsafe abortion with a history of available country data, 3rd edn. Geneva: WHO, 1997.

Yao M, Tulandi T. Current status of surgical and nonsurgical management of ectopic pregnancy. Fertility and Sterility. 1997;67:421-433.

Kohner N, Henley A. When a baby dies: the experience of late miscarriage, stillbirth and neonatal death. London: HarperCollins, 2003.

RCOG (Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists). The care of women requesting termination; evidence based guideline No. 7. London: RCOG, 2004.

RCOG (Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists). Management of early pregnancy loss; evidence based guidelines. 2006. Online. Available http://www.rcog.org.uk/index.asp?PageID=515.