Chapter 27 Comfort and support in labour

This chapter will explore the variety of means used by the midwife to achieve, for each woman and her partner, a birth experience that they can regard as positive.

A variety of factors affect the woman’s experience of labour and the progress made. These include:

Factors influencing women’s perceptions and experience of labour

The biological, psychological, social, spiritual, cultural and educational dimensions of each woman have an impact on how they express themselves and, indeed, how they experience labour. The challenge for midwifery is to provide adequate and adapted care for each childbearing woman. The essence of midwifery is to be ′with woman′, providing comfort and support to women in labour. Historically, the provision of care has been the role of women (Kitzinger 2000). Women have, throughout the ages, supported and helped each other during the process of birth. There is much literature to venerate the presence of the doula, midwife or friend of the birthing woman and the positive effect of the presence of this person on the outcome of labour.

One-to-one support in labour

Much midwifery and medical research has indicated that the one-to-one support by a midwife in labour reduces the need for analgesia and improves the birth experience of the mother. It also shortens the length of the labour (Haines & Kimber 2005, RCM 2006). This is reaffirmed in the Modernizing Maternity Care document (MCWP 2006), which concludes that maternity services should develop the capacity for every woman to have a designated midwife to provide care in established labour for 100% of the time. Continuous one-to-one support during labour can both reduce intervention rates and improve maternal and neonatal outcomes. The relationship between the woman and the midwife is important and can also impact on how the woman perceives the pain of labour (Lundgren & Dahlberg 2005).

The language of childbirth

The terms ′pain′ and ′labour′ are suggestive of difficulty and trouble. ′The skill of watching what you are saying is essential′ (Robertson 2003, p 63), when dealing with women during childbirth. A huge difference is made if sensitivity is used when explanations are provided or when information is given, to women. A lot of the terminology is medical, masculine and negative (Robertson 2003). The midwife is now able to rely on research, evidence and her/his decision-making skills to provide care. The word ′delivery′ today is replaced by the term birthing or birth and this is more suitable when talking about the concept and practice of normality within midwifery. Care must be taken to use appropriate and adapted language which is woman-friendly.

Understanding childbirth processes

As pain is caused by an ailment such as a burn, fracture or cut and not caused by a physiological process, these pathological notions cannot be readily employed or drawn upon, for midwifery purposes, or to explain what occurs during labour. The discomfort of labour is caused by the descent of the fetal head further into the pelvis. It is also caused by pressure on the cervix and the stretching of the vaginal walls and pelvic floor muscles, as descent of the presenting part occurs. The large uterine muscle is contracting more strongly, more frequently and for a longer duration, as labour progresses. This also increases the discomfort felt by the woman. It is therefore not suitable to use pain-relieving measures used in other medical circumstances, as the purpose is not to stop or impair the birth process (or contractions), but to let the labour progress normally, with the descent of the presenting part and with the rotation of this.

The object behind providing relief for the childbearing woman is to work with the contractions and the discomfort caused by these and the descending presenting part. The reactions of the woman to labour and to the discomfort of this varies greatly. So then must the response of the midwife. Answers and solutions are needed to support and enable the woman to cope with the birthing process.

Normal birth is a physiological process characterized by non-intervention, a supportive environment and empowerment of the woman (Anderson 2003). The midwife is a key figure in this process, supporting and assisting women through childbirth. Women state that they need someone who cares about them, rather than the use of supportive technology, to help them during childbirth (Walsh et al 2004). The needs of women must be addressed rather than prioritizing the needs of the service (Deery & Kirkham 2006). One study describes the midwife as ′anchored companion′ (Lundgren & Dahlberg 2005). Midwives stated that listening to the woman, giving the woman the opportunity to participate and take responsibility, developing a trusting relationship, reading the bodily expressions and following the woman through childbirth, were all very important aspects to ensure an optimal birth experience. Time, waiting and following the woman are important elements of care. The idea of patience and supporting the woman on her journey, giving meaning and sense to the pain of labour is paramount.

It is more convenient to think in terms of facilitating the birthing process. The campaign for normal birth launched by the Royal College of Midwives (RCM) (Day-Stirk 2005) has the following intended outcomes:

From this it is clear that the needs of the women who are giving birth are at the centre and the focus of the midwife’s attention. Not only will this ensure that care is optimal, but the midwife will enjoy providing care for women.

The MCWP (2006, p 10) reiterates this sentiment proposing a course of action that all ′… Maternity services develop the capacity for every woman to have a designated midwife to provide care for them when in established labour for 100% of the time′.

Mobility and positioning in labour

Studies carried out on ambulation, mobility and positioning during labour confirm that mobility during labour improves both the woman’s experience and the outcome of labour (Deakin 2001, Downe et al 2001, Haines & Kimber 2005). The uterine action is more effective, labour is shortened, there is a reduced need for pharmacological analgesia and oxytocin augmentation. The risk of fetal compromise is lowered.

It is documented that recumbent positions result in supine hypotension, diminished uterine activity and a reduction in the dimensions of the pelvic outlet (Walsh 2000). Women who take up an erect position during labour experience less pain, have significantly less perineal trauma and have fewer episiotomies. Restriction of movement can actually compromise labour (Gould 2000).

Culture, movement and positioning

Kitzinger (2000, p 749) would go as far as pronouncing that ′birth is movement′. Gould (2000) would agree, saying that movement is a significant characteristic of normal labour. Cultures where women are constrained and limited in their posture and positioning during labour, are in fact the exception, rather than the rule. Many cultures use movement, dance, physical contact and massage to encourage and sustain the process of labour. Writers now provide valuable reports and evidence of the engineering and movements made by some mothers in Africa, Japan and Fiji, which actually employ physiological responses of the woman, including turning, moving and dancing. These enhance the experience and facilitate the process of labour. There is much to be said for such an approach where the woman dictates the course of events and adapts to the activity of the uterus. One author also remarks how women move and swing their pelvis, thereby accommodating the passage of the fetal head through it (Kitzinger 2000). Walsh (2000) mentions that the compelling logic of gravity, meaning birthing in an upright position, should make us wonder how it has become routine practice to birth in a semi-recumbent position.

Henley-Einion (2007) discusses the value of the Five Rhythms method. Movements described as flowing, staccato, chaos, lyrical and stillness, which are a combination of expressive movements, rather than a set of routine exercises, are employed to provide dance and the music defines, guides, inspires and prompts the body. This is explained by Henley-Einion (2007, p 20) as the dance, beginning ′… with the head and then move the shoulders, elbows, hands, spine, hips, knees and feet. These body parts are used to “lead” the dance and to understand the connections between the body’s elements and how they blend together′. Such a strategy would be a fitting one to use during the birthing process.

The birth plan

The birth plan is a document that describes the woman’s requests in relation to her antenatal, intrapartum and postnatal care. This may be adjusted and changed as necessary to meet the needs of the woman during the pregnancy, labour, birth and postpartum period. It is a valuable tool for midwives and facilitates the provision of holistic, individualized care. Requests are written down and are kept in the handheld notes of the woman. It may also be useful to confirm the contents of the plan with her as labour commences. It must also be made clear that these are the personal choices of the woman in labour, and may well change as labour progresses, the unpredictable nature of labour being as it is. It may be useful for providing an insight into how the woman has viewed her pain relief at the beginning of pregnancy, and on commencing labour. The midwife may use this information to tailor and plan suitable care for the woman.

Nolan (2005) warns of the harm, which can be caused by the birth plan. In one study (Jones et al 1998), findings revealed that far from improving relationships between mothers and obstetric and midwifery staff, birth plans caused annoyance and actually affected the outcome of these labours negatively, with high intervention rates.

Women’s control of pain during labour

Pain control during labour should be a woman-centred strategem and not a medically oriented one. There is much evidence to suggest that women are not always more satisfied by a birth experience that is pain free (Fairlie et al 1999). Midwives are therefore required to give control of the pain to women rather than eradicating it. A clear differentiation must be made between the traditional goal of pain relief and the control of pain in labour.

The role of pain in labour is an important one and an empowering process, whereby the woman triumphs, by giving birth. The midwife must realize the importance of her own attitude to ′pain relief′ in labour, as this is frequently informed by the medical model.

The role of the midwife is to encourage and assist women to ′anticipate positively′ the birth of their baby. Two researchers in Japan revealed in their study on the intensity of memorized labour pain (Kabeyama & Miyoshi 2001, p 51) that ‘Self-control is the most important predictor of satisfactory childbirth experience for mothers’. They state that women who viewed labour as a challenge, in their attempt to control their breathing and relaxation, had much better outcomes. These active attitudes are supposed to reflect the positive attitudes to everything in daily life by the individual. The study goes on to say that not only does the removal of excessive fear and anxiety make a birth experience more satisfactory but that it also increases the mother’s pride and self-confidence. A greater motivation for constructing good mother–baby relationships also comes about.

Pain perception and somatosensory sensation

Many writers and researchers now agree that emotions such as fear, confidence, and also cognition, affect the person’s perception of pain (Leap & Anderson 2004, Mander 1998). More than any other type of sensation, pain can be modified by past experience, anxiety, emotion and suggestion. Lack of food, rest and sleep also impact on the woman’s perception of pain. The midwife must take into account not only the level or extent of the pain, but also all other subjective or illusory aspects of this.

The physiology of pain

Pain stimulus and pain sensation

Pain is caused by a stimulus; this stimulus may cause, or be on the verge of causing, tissue damage. Pain sensation may therefore be distinguished from other sensations, although emotions such as fear and anxiety are also experienced at the same time, thereby affecting the person’s perception of pain. It must also be remembered that a painful stimulus may also induce such changes by the sympathetic nervous system as increased heart rate, a rise in blood pressure, release of adrenaline (epinephrine) into the bloodstream and an increase in blood glucose levels. There is also a decrease in gastric motility and a reduction in the blood supply to the skin, causing sweating. Thus, stimuli that cause pain result in a sensory incident or occurrence.

Pain transmission

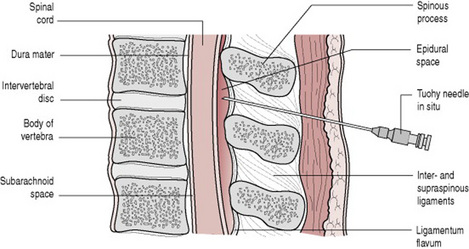

The pain pathway or ascending sensory tract originates in the sensory nerve endings at the site of trauma. The impulse travels along the sensory nerves to the dorsal root ganglion of the relevant spinal nerve and into the posterior horn of the spinal cord. This is known as the first neuron. The second neuron arises in the posterior horn, crosses over within the spinal cord (the sensory decussation) and transmits the impulse via the medulla oblongata, pons varolii and the mid-brain to the thalamus. From here, it travels along the third neuron to the sensory cortex (Fig. 27.1).

Figure 27.1 The sensory pathway showing the structures involved in the appreciation of pain.

(From Bevis 1984 with permission from Baillière Tindall.)

In cases of acute pain, sensations are transmitted along Aδ fibres, which are large diameter nerve fibres. This type of pain is perceived as being a pricking pain that is readily localized by the sufferer. The pathway for chronic pain is slightly different, the nerve fibres involved are of smaller diameter and are called C fibres. Chronic pain is often described as a burning pain that is difficult to localize.

Somatosensory function

′Somatic sensation′ refers to the sensory function of the skin and body walls. This is moderated by a variety of somatic receptors. There are particular receptors for each sensation, such as heat, cold, touch, pressure, etc. On entering the central nervous system, the afferent nerve fibres from somatic receptors form synapses with interneurons that comprise the specific ascending pathways going to the somatosensory cortex via the brain stem and the thalamus.

An afferent neuron, with its receptor, makes up a sensory unit. Usually the peripheral end of an afferent neuron branches into many receptors. The receptors whose stimulation gives rise to pain are situated in the peripheries of small unmyelinated or slightly myelinated afferent neurons. These receptors are known as nociceptors because they detect injury (Noci, from the Latin: harm, injury). The primary afferents coming from nociceptors form synapses with interneurons after entering the central nervous system. Substance P is a neurotransmitter that is liberated at some of these synapses when there is a pain impulse; it facilitates information about pain, which is transmitted to the higher centres.

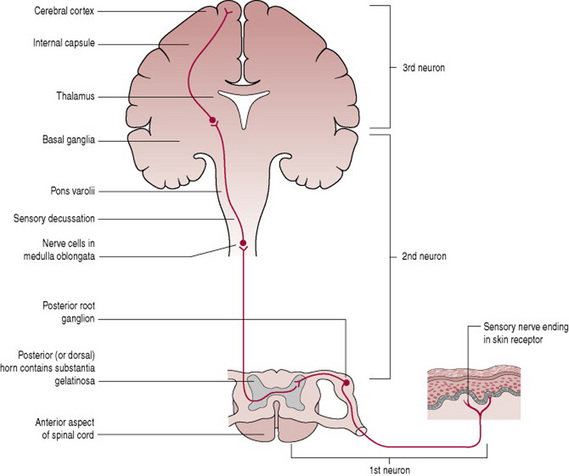

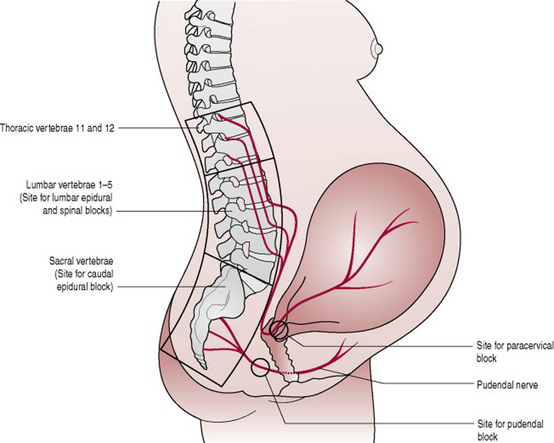

The stretching of the muscles and ligaments of the pelvic cavity and the pressure of the descending fetus during the birthing process causes, to varying degrees, pain in labour (Fig. 27.2). This sensation is transmitted by afferent or visceral sensory neurons, visceral pain being caused by the stretching or irritation of the viscera. Afferent neurons convey both autonomic sympathetic and parasympathetic fibres. Pain fibres from the skin and the viscera run adjacent to each other in the spinothalamic tract. Therefore pain from an internal organ, such as the uterus, may be perceived or felt as if it was coming from a skin area supplied by the same section or part of the spinal cord. Pain from the uterus may be perceived or felt in the back or the labia. When this sort of pain occurs or is experienced, it is commonly called referred pain.

Figure 27.2 Pain pathways in labour showing the sites at which pain may be intercepted by local anaesthetic techniques.

(From Bevis 1984 with permission of Baillière Tindall.)

One physiological explanation for the differing views, attitudes and perceptions of pain is that offered by Martini (2001, p 93) who states that: ′Due to the facilitation that results from glutamate and substance P release, the level of pain experienced can be out of proportion to the amount of painful stimuli. This effect can be one reason why people differ so widely in their perception of pain associated with childbirth′.

Endorphins and enkephalins

Endorphins are described as being opiate-like peptides, or neuropeptides, which are produced naturally by the body at neural synapses at various points in the central nervous system pathways. They modulate the transmission of pain perception in these areas. Endorphins are found in the limbic system, hypothalamus and reticular formation (Martini 2001). They bind to the presynaptic membrane, inhibiting the release of substance P. Therefore they inhibit the transmission of pain. Enkephalins are also neuropeptides; they have the ability to inhibit neurotransmitters along the pathway of pain transmission, thereby reducing it. These act like a natural pain relieving substance.

Theories of pain

Many theories of pain have been presented in the literature. These are not always applicable in the situation mentioned here (i.e. pain and labour). These theories include specificity, pattern, affect and psychological/behavioural theory (Mander 1998). The most widely used and accepted theory is that of Melzack & Wall (1965). These researchers have established that gentle stimulation actually inhibits the sensation of pain (Mander 1998). Their gate-control theory declares that a neural or spinal gating mechanism occurs in the substantia gelatinosa of the dorsal horns of the spinal cord. The nerve impulses received by nociceptors, the receptors for pain in the skin and tissue of the body, are affected by the gating mechanism. It is the position of the gate that determines whether or not the nerve impulses travel freely to the medulla and the thalamus, thereby transmitting the sensory impulse or message, to the sensory cortex. If the gate is closed, there is little or no conduction. If the gate is open, the impulses and messages pass and are transmitted freely (Fig. 27.2). Therefore, when the gate is open, pain and sensation are experienced.

Physiological responses to pain in labour

Several of the body’s systems are affected by labour. Pain of labour is associated with an increased respiratory rate. This may cause a decrease in the PaCO2 level, with a corresponding increase in the pH. The fetus is then affected and a subsequent drop in the fetal PaCO2 ensues. This may be suspected by the presence of late decelerations on the cardiotocograph. The acid–base equilibrium of the system may be altered by hyperventilation and breathing exercises. Alkalosis may then affect the diffusion of oxygen across the placenta, leading to a degree of fetal hypoxia.

Cardiac output increases during the first and second stages of labour. This can be by up to 20% and 50%, respectively. The augmentation is caused by the return of uterine blood to the maternal circulation, about 250–300 ml with each contraction. Pain, apprehension and fear may cause a sympathetic response, thereby producing a greater cardiac output.

Both the above systems are affected by catecholamine release. Adrenaline (epinephrine), which comprises about 80% of this, has the effect of reducing the uterine blood flow. This may in turn lead to a reduction of uterine activity.

Non-pharmacological methods of pain control

Homeopathy (see Ch. 50)

The aim of homeopathy is to reinforce the body’s physiological response. It attempts to ′cure like with like′ (Alexander et al 1990). Homeopathic remedies are prepared from plant extracts and from minerals. Professional advice is recommended during pregnancy as the holistic approach of this method entails a consideration of all the facets and the requirements of the individual. Castro (1992) recommends such solutions as Aconitum to relieve anxiety and Kali Carbonicum to alleviate back pain during labour.

Hydrotherapy

Immersion in water during labour as a means of analgesia has been used for years (Forde et al 1999). Garland & Jones (1994) state that the effectiveness of hydrotherapy is due to two factors. Heat relieves muscle spasm, and therefore pain, and ′hydrokinesis′ does away with the effects of gravity and also the discomfort and strain on the pelvis. Mander (1998) suggests that there is relatively little reliable and valid evidence to prove that bathing during labour increases maternal or neonatal infection. Other writers agree with this (Forde et al 1999). Advantages such as less augmentation by oxytocics and a reduction of analgesia used, were reported (Forde et al 1999, Mander 1998). Forde et al (1999) maintain that hydrotherapy has other benefits such as a reduction in the length of labour and a lower incidence of genital tract trauma. It is difficult to establish the evidence for hydrotherapy, because of the increase in pool births. However, these two –hydrotherapy used as analgesia, and, birthing in the pool, when the birth is carried out in water – are different.

Hydrotherapy during childbirth has the following outcomes:

There is however some contention regarding the use of water during labour and birth. A study by Burns (2001) shows that water immersion has been highly rated by both women and midwives and was valued by both multiparous and first time mothers (Box 27.1, Aly’s story). Benjoya Miller (2006, p 484) agrees that ′the calming atmosphere of a pool room benefits everyone involved′. The woman is less anxious and therefore feels less pain. Most women (95%) who used the pool had a normal vaginal birth (Baxter 2006).

Box 27.1 Aly’s story of Reuben’s birth

My waters broke at home at 2.45 a.m. (in two bursts) and my contractions started with gentle flutterings. The advice from our antenatal class was to stay at home as long as possible, ideally until the contractions were 2 every 10 min.

By 8.15 a.m., this was the case, and we were driving through rush hour traffic with me on all fours in the back of the car!

At the hospital, we were shown to the birthing pool room and I was examined at 9.00 a.m. to find I was 3 cm. The contractions continued to come stronger and closer together. I managed the pain with a TENS machine and some well taught yoga breathing, while sitting on an exercise ball!

At the point of needing something stronger, it was suggested I got into the pool; wow, it felt great, my whole body instantly felt calmer and with the aid of gas and air, I was ready to push. An hour later at 1.14 p.m. out came a beautiful, sleeping little boy.

We were so lucky with our birth, the support from the midwives was invaluable as even with a straightforward labour they are still an essential ingredient. Together with the imagery a pool birth creates, the day will always be a positive memory for us.

One randomized controlled trial showed that pain increased less markedly in women who used hydrotherapy (Cammu et al 1994). One Swiss hospital (Geissbuhler & Eberhard 2000) is able to offer hydrotherapy to all birthing women and this without harmful consequences.

Music therapy

Many birthing rooms are equipped with radio or CD apparatus and this is often a useful strategem to help women relax, be entertained and find some distraction while birthing. This is especially useful during the early stages of labour. Many types of music are available for relaxation, some are provided specifically for the birthing woman. Henley-Einion (2007) recounts that music has a positive effect on the body, mind and spirit of the woman. It provides empowerment and an enabling effect.

TENS

Transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation (TENS) is a widely used, well-appreciated and effective method of pain relief. This effectiveness is related to the action of TENS, which stimulates the production of natural endorphins and enkephalins and also its ability to impede incoming pain stimuli. One of its distinct advantages is that it includes the partner in the events surrounding the birth. Much documentary evidence suggests that when using TENS many husbands and birth partners feel able to assist and support their partner in labour and childbirth to a much greater degree. Partners feel a purposeful role and are able to help in managing the device. A reduction in the demand for pethidine and other pain relief was also found when TENS was employed (Poole 2007).

Technique

TENS is a small device which distributes low intensity electrical charges across the skin (de Ferrer 2006). These signals are said to prevent pain signals from the uterus, vagina and cervix arriving at the brain. The body’s own pain relief, the endorphins, are then released. TENS works by stimulating low threshold afferent fibres from, for example, the fibres of touch receptors. This then leads to inhibition of neurons in the pain pathways. As pathways activated by the touch receptors add a synaptic input into the pain pathways, people may rub or massage a painful area to relieve the pain; TENS functions in the same way.

The apparatus consists of four electrodes and four flexes that connect these to the TENS unit, which has controls to alter the frequency and the intensity of the impulse. The electrodes are positioned at the level of T10 and L1 on the mother’s back. These have been found to be effective for the control of pain during the first stage of labour. The other two electrodes are situated between S2 and S4 and provide control of pain during the second stage of labour. A boost control button conveys high intensity and high frequency patterns of stimulation of the dermatomes, thereby controlling pain during the uterine contraction and providing relief.

There are few contraindications to the utilization of TENS in labour (Walsh 1999). There is a slight risk of interference with the fetal monitor. Skin allergies may be caused by the electrodes or by the tape used. Finally, clients who have pacemakers may not employ this mode of pain control.

TENS is often more effective when started in early labour, and this fact is upheld by the literature (Johnson 1997, Walsh 1999). An important factor regarding TENS is that it is preferred by women. This is probably due to the fact that TENS enhances their control over the birth process.

The research on TENS reveals the paucity of scientific evidence to substantiate the fact that women in labour do find the application of this method effective (Juman Blincoe 2007). The reality is that it is used in conjunction with other methods of pain relief, and this makes the method very difficult for researchers to verify the evidence. There is, however, evidence of the usefulness of TENS as a pain relieving strategy in labour. In one study by Johnson (1997), 71% of the respondents out of a population of 10 077 stated having had either good or excellent pain relief from the TENS. Although Johnson (1997) cautions against an over simplistic interpretation of these results, as many of the participants used other methods of pain relief in conjunction with TENS, it can still be observed that many women find TENS suitable, effective and beneficial.

Pharmacological methods of pain control

Opiate drugs

The pain of labour is only partially amenable to opiates. Because of the episodic nature of labour pain, the mother tends to receive little benefit during contractions but may become over-sedated at other times. (Collis 2000, p 365)

Opiate drugs are frequently used during childbirth because of their powerful analgesic properties. The action of these drugs lies in their ability to bind with receptor sites in the central nervous system. The receptor sites are mainly found in the substantia gelatinosa of the dorsal horn of the spinal cord. Others are located in the midbrain, thalamus and hypothalamus.

Three systemic opioids are commonly used for pain relief in labour. Pethidine (meperidine in the USA) is the most popular but some units prefer diamorphine or meptazinol (Meptid). All have similar pain-relieving properties but they also have side-effects. These include nausea, vomiting and drowsiness in the mother and depression of the baby’s respiratory centre at birth. An antiemetic agent is sometimes given at the same time to reduce the nausea effect. Opioids given to the mother in labour can make breastfeeding more difficult to establish as the baby tends to be sleepy (Ransjo-Arvidson et al 2001). The side-effects are, however, variable and are influenced by maternal metabolism of drugs, the degree and speed of transfer of drugs and metabolites from maternal to fetal circulation and the ability of the fetus to process and excrete both. It is therefore important to ensure that the mother is fully informed antenatally so that she can make informed decisions about pain relief. A systematic review by Elbourne & Wiseman (2000) to compare different types of opioids concluded that no strong preference could be recommended.

Pethidine

Pethidine is the most frequently used systemic narcotic analgesic in England. This is possibly because it is of low cost and midwives have been administering pethidine for many years. It is a synthetic compound and acts on the receptors in the body. It is usually administered intramuscularly in doses of 50–150 mg (taking the size of the woman into account) and takes about 20 min to have an effect. Pethidine can be administered intravenously for a faster effect and some units use a machine to allow patient-controlled analgesia (PCA), but this is less common.

Pethidine delays stomach emptying and women may not use the birthing pool if they have been given an opiate drug. Some reports show that pethidine slows down the process of labour. Carson (1996) states that this may be due to the effect of opioids on the myometrium, relaxing it by their action on calcium ions, and also the effect of opioids on the hypothalamus, inhibiting the release of oxytocin from the posterior pituitary gland.

There is evidence to show that pethidine is reported as being less effective, or even not effective at all (Ranta et al 1994), when compared to nitrous oxide and oxygen (Entonox) and that sedation was wrongly assumed to be analgesia.

Diamorphine

Diamorphine has been found to provide effective analgesia for up to 4 hrs in labour. It is also said to be more rapidly eliminated from maternal and neonatal plasma (Freeman et al 1982). Diamorphine is used far less commonly than other opiates in labour, even though some claim it gives better pain relief and hence more comparative studies are needed (Fairlie et al 1999). It is possible that its lack of use in normal labour might be due to fears of the potentially addictive nature of diamorphine.

Meptazinol

Meptazinol is usually given in doses of 100–150 mg intramuscularly. It is fast acting and is effective for about 4 hrs. Meptazinol may be associated with an increased incidence of nausea and vomiting (Carson 1996). It has failed to replace pethidine in most maternity units in England.

Inhalation analgesia

A premixed gas made up of 50% nitrous oxide (N2O) and 50% oxygen administered via the Entonox apparatus is the most commonly used inhalation analgesia in labour. Nitrous oxide, like many other forms of analgesia, acts by limiting the neuronal and synaptic transmission within the central nervous system. Evidence shows that N2O induces opioid peptide release in the periaqueductal grey area of the mid-brain leading to the activation of the descending inhibitory pathways, which results in modulation of the pain/nociceptive processing in the spinal cord (Fujinaga & Maze 2002). The mixture (of gases) is stable at normal temperature, but separates under the temperature of −7 °C. In many large obstetric units the gas is piped, (this is stored in a bank) or alternatively is available in cylinders. Hospitals take responsibility for the safe storage of cylinders but in community practice midwives should store cylinders on their side, rather than upright. This is because nitrous oxide is heavier than oxygen and the horizontal position reduces the risk of delivering a severely hypoxic mixture. The cylinders must be brought into a warm room if they have been exposed to cold temperatures, and the gases remixed by inverting the cylinder at least three times before use.

Entonox apparatus is usually manufactured by the British Oxygen Company (BOC). Both the apparatus and the cylinder are made so that they do not fit on to other equipment. These fit together by a pin index system. The cylinder is blue with a blue and white shoulder. The one-way valve opens on inspiration and the mother needs to be adequately informed of the functioning of the apparatus, being advised that optimal analgesia is obtained by closely applying the lips around the mouthpiece (Fig. 27.3) or, in some cases, firmly applying the mask to the face. The gases take effect within 20s; it is therefore important that the woman uses it before a contraction. The maximum efficacy of the gases occurs after about 45–50 s and, if the timing is right, this should happen with the height of the contraction, providing maximum relief for the woman. This method of pain control is useful in that the woman is able to administer it herself. The effectiveness of it relies on the woman’s prior instruction and ability to follow this.

Some reports state that teratogenic and other side-effects exist among staff who are exposed to high levels of nitrous oxide (Ahlborg et al 1996). The main one of these is that of sub-fertility. Scavenging equipment, to extract expired gases, is recommended for all birthing rooms.

Regional (epidural) analgesia

More women are now requesting a pain-free labour and ask for epidural analgesia as soon as labour is established. Women who find alternative methods of pain relief inadequate once experiencing strong contractions might decide to request an epidural when labour is well advanced. This makes explanation of epidural analgesia antenatally even more important. The pain relief from an epidural is obtained by blocking the conduction of impulses along sensory nerves as they enter the spinal cord. When epidural block in labour was first introduced in the 1970s most attention was focused on the technique and less on the problems it caused in relation to normal birth. In those early years, as well as providing the required sensory block, the blockade of motor and sympathetic nerves caused loss of bladder sensation and function, complete numbness of the legs, significant hypotension, relaxation of pelvic floor muscles and impairment of expulsive efforts in the second stage of labour.

Preparation of the woman

The woman and her partner must receive clear explanations of the procedure and the woman’s consent must be obtained. An intravenous infusion of crystalloid fluids is commenced prior to siting the epidural. The need for ′preloading′ has reduced now that low dose epidural blockades are used, reducing the risk of hypotension. Frequently the mother is positioned in the left lateral position for the procedure. This is partly because of the risk of supine hypotension and also because the mother may well be more comfortable in this position when in labour. Some may prefer to ask the mother to sit up and flex the spine, in an effort to separate the vertebrae, thus facilitating the management of the procedure. The position of the mother is very important, and this should be discussed and negotiated with her. The fetal heart rate and the woman’s blood pressure must be recorded throughout, especially in the case of pregnancy-induced hypertension, or in any case of suspicion of fetal compromise.

Epidural technique

A local anaesthetic is injected into the epidural space of the lumbar region, usually between vertebrae L1 and L2, or between L2 and L3, or between L3 and L4. The procedure is usually carried out by an experienced (obstetric) anaesthetist, under strict aseptic conditions. A small amount of local anaesthetic is used before inserting a Tuohy needle into the epidural space (Fig. 27.4). To locate the epidural space the anaesthetist advances the needle cautiously. The Tuohy needle, usually 16 g, is introduced little by little until the resistance of the ligamentum flavum is encountered. At this point a syringe is attached to the Tuohy needle, after removal of the stilette. The needle is then inserted further, cautiously, until it enters the epidural space. This is recognized by the loss of resistance when pressure is applied to the plunger of the syringe (loss of resistance to saline is sometimes a preferred technique). It is particularly important that the woman keeps very still at this stage as the subarachnoid space is a few millimetres deeper. A slight movement by the woman could result in the Tuohy needle inadvertently puncturing the meninges and causing a ′dural tap′.

Once confident that the Tuohy needle is in the epidural space and there has been no leakage of blood or CSF, a catheter is threaded through the needle to facilitate bolus top-ups or a continuous infusion. A test dose of the local anaesthetic lidocaine (lignocaine), of about 4 ml, may then be given – although some anaesthetists prefer to inject the first dose of bupivacaine (Marcain) very slowly whilst observing for any adverse reactions. Continuous infusion of dilute bupivacaine and opioids (usually fentanyl) has permitted significant reductions in the amount of local anaesthetic used whilst ensuring rapid analgesia. A further advantage of this regimen lies in the mother’s ability to move about and bear down in the second stage of labour because of the minimal motor block effect. The Comparative Obstetric Mobile Epidural Trial (COMET Study Group UK 2001) found that low dose infusion epidurals resulted in a lower incidence of instrumental vaginal deliveries compared with traditional bolus epidurals.

An antibacterial filter is attached to the end of the catheter. The catheter is then secured to the mother’s back with strapping and a syringe pump set up by the anaesthetist if there is to be a continuous infusion.

Observations and care by the midwife

After the administration of the first dose of bupivacaine and any subsequent top-up doses of local anaesthetic, the blood pressure and pulse should be measured and recorded every 5 min for 20–30 min and then every 30 min. The mother may sit up in bed once it has become established that her blood pressure is stable, but should be tilted to one side to prevent aortocaval compression.

Throughout labour the mother should be assisted to change her position regularly to avoid soft tissue damage. The fetal heart is usually monitored electronically. The mother may be unaware of a full bladder, so the midwife must ensure that the woman is encouraged to empty her bladder regularly. Similarly she will not feel uterine contractions, or a desire to bear down in the second stage of labour, so close observation is necessary. Uterine activity may be electronically monitored.

The spread of the block is checked regularly by the midwife. Units vary in whether they use a cold object or ethyl chloride spray to test the extent to which the mother has lost sensation.

The epidural top-up

Midwives top-up the epidural block by giving a further dose as prescribed by the anaesthetist. The prescription should indicate clearly the dosage and frequency of the drugs to be given, and the positioning of the woman. The midwife is personally responsible for ensuring that she is competent to carry out the procedure. The same observations are made as with the initial dose. The midwife should be aware of the possible complications and their immediate treatment. It is important to prevent aortocaval occlusion since this would compound the effects of any hypotension occurring as a result of the epidural block.

Complications of epidural analgesia

The use of low dose bupivacaine solutions for analgesia in labour has limited the risks of hypotension and local anaesthetic toxicity. The complications of epidurals may include:

For most women, the side-effects following epidural are minimal and backache is more likely to be due to localized bruising and immobility than epidural analgesia. The increased use of epidural analgesia has in particular resulted in an increase in assisted vaginal birth. According to Thorp et al (1993), intervention is much less likely to occur if the epidural has been sited after 5 cm of dilatation of the cervical os, but this view remains contentious. Thorp’s study is in keeping with the view of Sutton (2000), who puts forward the notion that the birth process necessitates the ′opening of the mother’s back′. This means the lifting up of the lower lumbar vertebrae and the sacrum to facilitate the passage and birth of the baby. It is argued that today’s lifestyle, e.g. the way women sit with their legs crossed or in a car seat position, with their knees higher than the pelvis, does not increase the available space for the fetus to descend, therefore making it difficult for the head to enter the pelvis.

The fact that more forceps births are carried out if the cervical dilatation is <5 cm when the epidural is sited also supports the above view. If the head is engaged and below the ischial spines, the head is likely to be well flexed and satisfactory progress will be made. The effect of the local anaesthetic reduces the muscle tone of the pelvic floor, which needs to remain firm, to aid flexion and rotation of the fetal head, before allowing the fetal head to advance. The fetal head then, in the case of an epidural, may not fully flex and progression may be arrested. Intervention then follows.

Post-dural puncture headaches and dural tap

If there has been a ′dural tap′ during the procedure, women are likely to develop a severe postural headache caused by leakage of CSF. Headaches from a dural tap can also follow spinal anaesthesia for operative deliveries. However, needles used for deliberate spinal injection are much finer than Tuohy needles and the use of smaller gauge ′pencil point′ needles has greatly reduced the leakage of CSF. Severe headache following a ′dural tap′ is treated by epidural injection of 10–20 ml of maternal blood (a ′blood patch′), to seal the puncture and relieve the headache.

Hypotensive incident

Local analgesia affects the sympathetic nervous system by causing vasodilatation and a fall in blood pressure. For most women the fall is minimal. However, if the mother’s systolic blood pressure falls below 75% of baseline (e.g. from 120 to 90 mmHg) she should be given oxygen and turned on her side while waiting for the anaesthetist. Hartmann’s solution is normally infused rapidly if the blood pressure remains low. The lateral position should be assumed to prevent this happening. Adrenaline (epinephrine), a vasopressor, may be used if required to raise maternal blood pressure, increase cardiac output and the heart rate.

Patchy blocks

The epidural may be more effective on one side or in certain areas of the woman’s body. It may be extremely difficult for the anaesthetist to produce an even, effective block. The anaesthetist must be kept informed and will attempt to render the block more efficient, by re-siting it, changing the position of the woman or injecting more local anaesthetic.

The responsibilities of the midwife

The midwife has an important enabling and facilitating role to help the woman during childbirth. Careful administration of drugs and monitoring the effects of these is essential to the provision of quality care. Accurate and detailed records of all care given will provide a good basis from which proper decisions may be made concerning the progress and the needs of the woman.

Ahlborg G, Axelsson J, Bodin L. Shift work nitrous oxide exposure and subfertility among Swedish midwives. International Journal of Epidemiology. 1996;25(4):783-790.

Alexander J, Levy V, Roch S. Intrapartum care: a research-based approach. London: MacMillan, 1990.

Anderson G. A concept analysis of normal birth. Evidence-based Midwifery. 2003;1(2):48-54.

Baxter L. What a difference a pool makes: Making choice a reality. British Journal of Midwifery. 2006;16(6):368-372.

Benjoya Miller J. All women should have the choice of waterbirth. British Journal of Midwifery. 2006;14(8):484.

Bevis R. Anaesthesia in midwifery. London: Baillière Tindall, 1984.

Burns E. Waterbirth. MIDIRS Midwifery Digest. 2001;11:S10-S13.

Cammu H, van Classen K, Wettere L, et al. ′To bathe or not to bathe′ during the first stage. Acta Obstetricia et Gynecologica Scandinavica. 1994;73(6):468.

Carson R. The administration of analgesics. Modern Midwife. 1996;6:12-16.

Castro M. Homeopathy for mother and baby. London: MacMillan, 1992.

Collis R. Pain relief and anesthesia. In: Kean L, Baker P, Edelstone D, editors. 2000 Best practice in labor ward management. London: W B Saunders, 2000.

COMET (Comparative Obstetric Mobile Epidural Trial) Study Group UK. Effect of low-dose mobile versus traditional epidural techniques on mode of delivery: a randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2001;358:19-23.

Day-Stirk F. The big push for normal birth. Midwives. 2005;8:18-20.

Deakin B-A. Alternative positions in labour and childbirth. British Journal of Midwifery. 2001;9(10):620-625.

Deery R, Kirkham M. Supporting midwives to support women. Page L, McCandlish. The new midwifery, 2nd edn., London: Churchill Livingstone, 2006. Ch. 6

de Ferrer G. TENS: Non-invasive pain relief for the early stages of labour. British Journal of Midwifery. 2006;14(8):480-482.

Downe S, McCormick C, Beech BL, et al. Labour interventions associated with normal birth. British Journal of Midwifery. 2001;9(10):602-606.

Elbourne D, Wiseman RA. Types of intra-muscular opioids for maternal pain relief in labour. Cochrane Database System Reviews. (Issue 2):2000. CD001237

Fairlie FM, Marshall L, Walker JJ, et al. Intramuscular opioids for maternal pain relief in labour: a randomised controlled trial comparing pethidine with diamorphine. British Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology. 1999;106:1181-1187.

Forde C, Creighton S, Batty A, et al. Labour and delivery in the birthing pool. British Journal of Midwifery. 1999;7(3):165-171.

Freeman RM, Moreland TA, Blair AW. Diamorphine, the obstetric analgesia: a neurobehavioural and pharmacokinetic study in the neonate. Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology. 1982;3:102-106.

Fujinaga M, Maze M. Neurobiology of nitrous oxide-induced antinociceptive effects. Molecular Neurobiology. 2002;25(2):167-189.

Garland D, Jones K. Waterbirth, first stage immersion or non-immersion? British Journal of Midwifery. 1994;2(3):113-120.

Geissbuhler V, Eberhard J. Waterbirths: a comparative study. a prospective study on more than 2000 waterbirths. Fetal Diagnosis and Therapy. 2000;15:21-300.

Gould D. Normal labour: a concept analysis. Journal of Advanced Nursing. 2000;31(2):418-427.

Haines A, Kimber L. Improving the birthing environment. The Practising Midwife. 2005;8(10):18-20.

Henley-Einion A. The ecstasy of the spirit: Five Rhythms for healing. British Journal of Midwifery. 2007;10(3):20-23.

Jones M, Barik S, Mangune H, et al. Do birth plans adversely affect the outcome of labour? British Journal of Midwifery. 1998;6(1):38-41.

Johnson MI. Transcutaneous nerve stimulation in pain management. British Journal of Midwifery. 1997;5(7):400-405.

Juman Blincoe A. TENS machines and their use in managing labour pain. British Journal of Midwifery. 2007;15(8):516-519.

Kabeyama K, Miyoshi M. Longitudinal study of the intensity of memorized labour pain. International Journal of Nursing Practice. 2001;7:46-53.

Kitzinger S. Some cultural perspectives of birth. British Journal of Midwifery. 2000;8(12):746-750.

Leap N, Anderson T. The role of pain in normal birth and the empowerment of women. In: Downe S, editor. 2004 Normal childbirth: evidence and debate. London: Churchill Livingstone, 2004.

Lundgren I, Dahlberg K. Midwives’ experience of the encounter with women and their pain during childbirth. In: Wickham S, editor. Midwifery best practice. London: Books for Midwives, 2005. Vol. 3

Mander R. Pain in childbearing and its control. London: Blackwell Science, 1998.

Martini FH. Fundamentals of anatomy and physiology, 5th edn. London: Prentice Hall, 2001.

MCWP (Maternity Care Working Party). Modernising maternity care –A Commissioning Toolkit for England. The National Childbirth Trust, 2nd edn. 2006. The Royal College of Midwives. The Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists

Melzack R, Wall PD. Pain mechanisms: a new theory. Science. 1965;150(3699):971-979.

Nolan M. Birth plans – A relic of the past or still a useful tool? In: Wickham S, editor. Midwifery best practice 2. London: Books for Midwives, 2005.

Poole D. Use of TENS in pain management: Part 2 How to use TENS. Nursing Times. 2007;103(8):28-29.

Ransjo-Arvidson AB, Matthieson AS, Lilja G, et al. Maternal analgesia during labor disturbs newborn behavior: effects on breastfeeding, temperature and crying. Birth. 2001;28(1):5-11.

Ranta P, Joupilla P, Spalding M, et al. Parturients’ assessment of water blocks, pethidine, nitrous oxide, paracervical and epidural blocks in labour. International Journal of Obstetrics and Anaesthesia. 1994;3(4):193-198.

RCM (Royal College of Midwives). Position Statement No. 26 Refocusing the role of the midwife. London: RCM, 2006.

Robertson A. Watch your language!. In: Wickham S, editor. Midwifery best practice. London: Books for Midwives, 2003.

Sutton J. Occipito-posterior positioning. The Practising Midwife. 2000;3(6):20-22.

Thorp JA, Hu DH, Albin RM, et al. The effect of intrapartum epidural analgesia on nulliparous labour: a randomized, controlled, prospective trial. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. 1993;169(4):851-858.

Walsh D. Transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation. British Journal of Midwifery. 1999;7(9):580.

Walsh D. Evidence-based care series 1. Birth environment. British Journal of Midwifery. 2000;8(5):276-278.

Walsh D, El-Nemer A, Downe S. Risk safety and the study of physiological birth. In: Downe S, editor. Normal childbirth: evidence and debate. London: Churchill Livingstone, 2004.

Downe S. Normal childbirth: evidence and debate. London: Churchill Livingstone, 2004.

This publication provides an insightful account into how to support women during the birthing process. Chapter 2 on ‘The role of pain in normal birth and the empowerment of women’, presents some accounts of women’s experiences of birth and also proposes many useful strategies and ways of working with pain, to help women during birth. The working with pain paradigm offers very interesting and constructive recommendations and perceptions