Chapter 36 Perinatal mental health

Pregnancy and the puerperium are best construed as major life events or in psychological terms – life crises. Having children is associated with an immense increase in individual life changes that are likely to lead to anxiety and chronic stressors. This may be associated with a change of housing. Pregnant women in employment will inevitably take maternity leave and may return to work in a different capacity or even on a part-time basis. Roles and responsibilities alter with changes to the dynamics of family relationships. Having a child places strains on relationships and there is a higher rate of relationship breakdown around this time. Many women find coping with the physiological adaptation to pregnancy, the plethora of antenatal screening tests, issues around choice, control and communication emotionally draining. Therefore, while many women and their partners experience pregnancy and childbirth as a joyous, exciting and life-affirming event, the transition to parenthood is an emotionally charged time bringing common anxieties, a certain degree of loss and periods of self-doubt. This can culminate in pregnancy and postpartum being a fragile time of physical, psychological and social upheavals. Unlike other stressful life events that can precipitate mental illness, childbirth is known to be associated with an increased risk of psychiatric illness. Pregnancy provides a wealth of opportunities for promoting emotional health while preventing and predicting mental illness. It is important for midwives to be able to identify normal reactions to motherhood from the early warning signs of emotional distress or indeed mental illness.

Parts A and B are two distinct but inter-related parts.

The aim of Part A is to explore

The aim of Part B is to explore:

Stress/anxiety

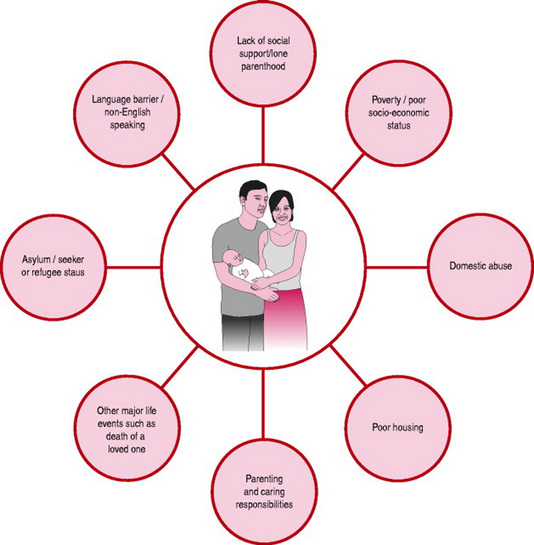

Pregnancy and the puerperium are normal life events, yet they are periods in a woman’s life when her vulnerability exposes her to a significant amount of anxiety and stress. Stress during pregnancy is both essential and normal for the psychological adjustment of pregnant women. The ‘worry work’ that women encounter assists in their psychological adaptation to the emotional changes of pregnancy. Conversely, elevated levels of stress hormones and unnecessary anxiety will stretch coping reserves, and could prove crippling. The deleterious effects for both mother and fetus of raised levels of the stress hormone, cortisol, during pregnancy have been reported (Evans et al 2001, Teixeira et al 1999). Even though such studies have raised the profile of antenatal stress factors as a possible precursor to mental illness, they have provided very little insight as to how antenatal stress may be alleviated. As depicted in Figure 36A.1, there are many factors that contribute to unhappiness in women’s lives and affect their emotional health and well-being. Understanding the root cause and expression of mental distress in women is complex as the social circumstances into which women live and children are born play a major role in their health and well-being.

Domestic abuse

Domestic abuse as reported by the Home Office for England (Nicholas et al 2005) and CEMACH report ‘Saving Mothers’ Lives (Lewis 2007) features as a major public health concern. Emotionally and socially, women are affected on many levels as it occurs across society regardless of race, ethnicity, gender, age, wealth and geography. Irion et al (2000) provide some evidence of women in abusive relations and the implications for their emotional well-being. Domestic abuse statistics account for:

Antenatal screening for domestic abuse

A firm recommendation is to make routine and sensitive enquiry about domestic abuse during the antenatal period (DH 2006, Lewis 2007). Effective strategies must be in place such as multi-agency support services, to ensure that appropriate help and information is offered to women at an early stage (DH 2004). Domestic abuse causes both physical injury and psychological harm to women and children on a very substantial scale. Furthermore the adverse effects on women’s mental health can last for many years (Irion et al 2000). Victims of child sexual abuse can suffer from depression, anxiety, substance abuse, eating disorders, self-harm and suicide. There is a consistent link between domestic abuse and the physical and or sexual abuse of children. This often involves the same male perpetrator, and the majority of these children will witness the violence and abusive behaviour exacted on their mothers. Women who are in abusive relationships are more likely to self-harm, develop eating disorders or other symptoms of mental illness (DH 2003a).

Transition to parenthood

Postnatally, parents may find coping with the demands of a new baby, e.g. infant feeding, financial constraints, the whole process of lifestyle adjustments and role changes, a real strain. For new mothers, this will involve diverse emotional responses ranging from joy and elation to sadness and utter exhaustion. Fatigue, pain and discomfort commonly result once the elation that follows the safe arrival of the baby wears off. Disturbed sleep is inevitable with a new baby. Mothers who are trying to establish breastfeeding, older women, women who are recovering from a caesarean section or those who have had a long and difficult labour/birth, twins or higher multiples, may feel wretched and constantly weary for months following childbirth. Soreness and pain being experienced from perineal trauma will affect libido, so too will feelings of exhaustion, despair and unhappiness that may be associated with the round-the-clock demands of caring for a new baby. Women may be left feeling bereft and quite miserable after giving birth.

Role change/role conflict

Having a baby, and particularly the transition to parenthood that accompanies the first child, leads to a significant shift in the couple’s relationship. Social networks are disrupted, especially those of the mother and the quality and quantity of social support such networks can and do provide. There is a strong possibility that old relationships, particularly with those who are childless or single, may be weakened. However, some relationships are strengthened or even replaced gradually by new contacts established with other parents. The dynamics of relationships with family members are also altered during this process of transition and change. The relationship with the woman’s parents for example alters as the daughter becomes a mother herself and her parents develop new roles as grandparents. The competing demands on time of caring for a new baby may lead to role conflict and confusion for parents. Mothers may find that there is little time for them to pursue other activities, which can diminish any opportunity for contact with and support from others (Raynor 2006). Postnatal care is therefore essential to women’s emotional well-being and should be a continuation of the care given during pregnancy. Its contribution plays a significant part in the positive adjustment to parenthood, as it assists in the acquisition of confident and well-informed parenting skills (DH 2004).

Communication

Effective communication during pregnancy and the puerperium is essential. Yet poor communication is still the single most common factor that is associated with women’s dissatisfaction with their care. A survey by the National Perinatal Epidemiology Unit (NPEU) (Redshaw et al 2007) reports that communication remains a matter of concern within the maternity service. Being provided with adequate information will serve to:

The ideology of motherhood

Motherhood, it is thought, ensures that a woman has fulfilled her biological destiny, confirms a woman’s femininity and raises her status in society, but without financial gain (Crittenden 2001, Winson 2003). Instead of feeling elated by motherhood some women experience displeasure, harbour feelings of unhappiness and feel dismayed or even disappointed in their role as new mothers (Grabowska 2003). Many may be afraid to speak out about their feelings in case they are judged a ‘bad’ or not a ‘good enough’ mother. Painful emotions may be internalized, magnifying difficulties with coping and sleeping, leading many women to suffer in silence. Distress may then manifest as mothers rage against their impossible situation. Some women may even grieve for the loss of their former lifestyle, career or status. Nicholson (1998) contends that healthcare professionals have defined women’s postnatal experience through proposing that well-adjusted, ‘normal’ and therefore ‘good’ mothers are those who are happy and fulfilled, but those who are unfulfilled, anxious or distressed are ‘ill’ and may be perceived as ‘bad’ mothers. This may lead to feelings of isolation, inadequacy and confusion. The ideology of motherhood is therefore an assumption and a paradox with inherent dichotomies as the woman strives to be ‘super mum, super wife, super everything’ (Choi et al 2005). Midwives have a pivotal role to play in assisting women and their partners to prepare for the physical, social, emotional and psychological demands of pregnancy, labour, the puerperium and, perhaps more importantly, parenthood (Barlow & Coren 2005).

Social support

During periods of stress, supportive and holistic care from midwives will not only assist in promoting emotional well-being of women, but will also help to ameliorate threatened psychological morbidity in the postnatal period (Hodnett 2000, Oakley et al 1996, Webster et al 2000, Wessely et al 2000). Women who are socially isolated or who have poor socioeconomic circumstances are particularly vulnerable to mental health problems and need additional help and support. This includes women from minority ethnic groups who do not speak English, and often have problems accessing healthcare. Bick et al (2002) provide evidence regarding the psychosocial benefits of midwifery care well beyond the historical boundaries of the traditionally defined postnatal period. The restructuring of postnatal care means there is now a social expectation that midwives will respond flexibly and responsively to women’s emotional needs on an individual basis (Brown et al 2002, DH 2004, 2007a,b, NICE 2006). This calls for skilled multidisciplinary and multi-agency collaboration as well as effective team work, taking into account the diversity within teams, for example the Department of Health (DH 2003b) acknowledges the contribution of the maternity support worker in maternity care. Social support is further explored in Part B.

Normal emotional changes during pregnancy, labour and the puerperium

Pregnancy

Since many decisions have to be made it is perfectly normal for women to have periods of self-doubt and crises of confidence. Box 36A.1 outlines the many and varied emotions women may experience during the different trimesters of pregnancy. The reality for many women will encompass fluctuations between ambivalence to positive and negative emotions.

Box 36A.1 Normal emotional changes during pregnancy

First trimester

Second trimester

Labour

During labour, midwives must facilitate choice to help women maintain control. Factors that induce stress should be prevented, or at least minimized, as the woman’s long-term emotional health may be severely compromised by an adverse birth experience (Lyons 1998, Redshaw et al 2007). Choice and control are important psychological concepts to mental health and well-being. Evidence from Green et al’s (1998) prospective study of women’s expectations and experiences of childbirth suggests that having choice in pregnancy and childbirth, and a sense of being in control, leads to a more satisfying birth experience. The timely publication of ‘Maternity Matters’ (DH 2007a) epitomizes a real philosophical shift in maternity care in terms of the guaranteed choices for women. ‘Recorded Delivery’ (Redshaw et al 2007) identifies key factors related to women’s perception of control during labour, these are:

Ongoing research to determine the relationship between women’s perception of control during childbirth and postnatal outcomes is needed in order to measure factors such as postnatal depression, positive parenting relationships and self-esteem. Common emotional responses during labour are detailed in Box 36A.2.

The puerperium

The puerperium is hailed as the ‘fourth trimester’ – an emotionally complex transitional phase. By definition, it is the period from birth to 6–8 weeks postpartum, when the woman is readjusting physiologically, socially and psychologically to motherhood. Emotional responses may be just as intense and powerful for experienced as well as for new mothers. The major psychological changes are therefore emotional. The woman’s mood appears to be a barometer, reflecting the baby’s needs of feeding, sleeping and crying patterns. New mothers tend to be easily upset and oversensitive. A sense of proportion is easily lost, as women may feel overwhelmed and agitated by minor mishaps. The woman might start to regain a sense of proportion and ‘normality’ between 6 and 12 weeks. Exhaustion is also a major factor of women’s emotional state. Perhaps the most important factor in regaining any semblance of normality is the mother’s ability to sleep throughout the night. A woman’s sexual urges, emotional stability and intellectual acuity may take months, if not longer, to return and for the woman to feel whole again. Normal emotional changes in the puerperium are summarized in Box 36A.3.

Box 36A.3 Normal emotional changes during the puerperium

Postnatal ‘blues’

Childbirth is an emotionally intense experience. Mood changes in the early days postpartum are particularly common. The postnatal ‘blues’ is a transitory state, experienced by 50–80% of women depending on parity (Harris et al 1994). It has been identified as an antecedent to depression following childbirth (Cooper & Murray 1997, Gregoire 1995). The mean onset typically occurs between day 3 and 4 postpartum, but may last up to 1 week or more, though rarely persisting longer than 48 hrs. The main features are mild and may include:

The actual aetiology is unclear but hormonal influences (e.g. changes in oestrogen, progesterone and prolactin levels) seem to be implicated as the period of increased emotionality appears to coincide with the production of milk in the breasts, as well as the quality of social support. This state of heightened emotionality is self-limiting and will resolve spontaneously, assisted by support from loved ones. The midwife should be vigilant during this time as persistent features could be indicative of depressive illness.

Distress or depression?

Repeated contact with women during pregnancy and puerperium afford a wealth of opportunity to explore feelings, experience and emotions, and for midwives to provide clear explanations to women about the differences between distress – a normal reaction to major life events – and depression – an abnormal reaction to life crises. However, midwives should be mindful of over-reliance on the medical model to describe women’s moods as such an approach may serve to pathologize or medicalize normal emotional changes (Nicholson 1998).

Emotional distress associated with traumatic birth events

Understanding the root cause and expression of mental distress associated with pregnancy and childbirth is complex. It is important to recognize the inter-relationship between traumatic life events and women’s mental health. What is intended to be one of the happiest days in a woman’s life can quickly turn into anguish and distress. Effects of intense pain, use of technological interventions, insensitive and disrespectful care may prove very distressing and frightening. Post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) a term most commonly associated with individuals who have suffered the onslaught of war, has emerged in the literature around maternity care (Lyons 1998). Unlike mild to moderate depression in the postpartum period, which seems to have its roots in the biophysical and psychosocial domains, obstetric distress after childbirth appears to be directly linked to the stress, fear and trauma of birth, yet its prevalence is unrecognized (Lyons 1998). Psychological interventions such as ‘debriefing’ has been suggested to manage immediate symptomatology but there is no reliable evidence that it is a useful intervention in reducing psychological morbidity (Alexandra 1998, Bick et al 2002, Wessely et al 2000). Moreover, clinical guidelines from NICE (2007) have stated that following a traumatic birth, women should not routinely be offered ‘single-session formal debriefing focused on the birth’. Instead midwives and other healthcare professionals should support women who wish to talk about their experience and draw on the love and support of family and friends. Neither should midwives overlook the impact of birth on the partner.

Conclusion

A plethora of significant social and health policies and clinical guidelines have resulted in wider consideration being given to the social and psychological context of pregnancy and the puerperium. Midwives need to have knowledge and understanding of how they influence care provision. Box 36A.4 provides a summary of key points.

Box 36A.4 Summary of key points

Introduction

Perinatal psychiatric disorder is now an accepted term used both nationally and internationally. It emphasizes the importance of psychiatric disorder in pregnancy as well as following childbirth. It emphasizes the variety of psychiatric disorders that can occur at this time, not just postnatal depression and the importance of psychiatric disorders that were present before conception, but those that arise during the perinatal period (Box 36B.1).

Box 36B.1 What is perinatal psychiatric disorder?

The emotional well-being of women is of primary importance to midwives. Not only do mental health problems affect obstetric outcomes but also the transition to parenthood and emotional well-being and health problems in the infant. Prior to the report ‘Saving Mothers’ Lives’ (Lewis 2007) psychiatric disorder in pregnancy and the postpartum period was leading cause of maternal morbidity and mortality (Oates 2001, 2004). These reports of the Confidential Enquiry into Maternal Deaths in the United Kingdom, recommend that midwives routinely ask at early pregnancy assessment about previous mental health problems, their severity and care. These recommendations have also been made by the Royal College of Psychiatrists Council (RCPC 2000), the Women’s Mental Health Strategy, (part of the Mental Health NSF DH 1999), the Maternity Standard 11 of the Children, Young Peoples and Maternity NSF (DH 2004), the NICE Guidelines (2007) on the management of antenatal and postnatal mental health and the Clinical Negligence Standards for Trusts. In addition, NICE (2007) recommends that midwives should ask questions on at least two occasions, antenatally and following birth about women’s current mental health. Systems should be in place locally to ensure that women with mental health problems and those at risk of developing them receive the appropriate care.

It is therefore essential that all midwives have education and training to be familiar with normal emotional changes, commonplace distress and adjustment reactions as well as the signs and symptoms of more serious illnesses.

Types of psychiatric disorder

The term mental health problem is commonly used to describe all types of emotional difficulties from transient and temporary states of distress, often understandable, to severe and uncommon mental illness. It is also used frequently to describe learning difficulties, substance misuse problems and difficulties coping with the stresses and strains of life. It is therefore too general and too non-specific to be of use to the midwife. The term does not discriminate between severity and need and does not help the midwife distinguish between those conditions which she can manage and those which require specialist attention. For this reason, in this chapter, the term psychiatric disorder is preferred as it can be further categorized and the different types can be described aiding recognition and the planning of care.

Psychiatric disorders are conventionally categorized into:

Serious mental illnesses

These include schizophrenia, other psychotic conditions, bipolar illness and severe (unipolar) depressive illness. Previously, these conditions were called psychotic disorders.

Mild to moderate psychiatric disorders

These were previously known as ‘neurotic disorders’. These include non-psychotic mild to moderate depressive illness, mixed anxiety and depression, anxiety disorders including phobic anxiety states, panic disorder, obsessive compulsive disorder and post-traumatic stress disorder.

Adjustment reactions

These would include distressing reactions to life events including death and adversity.

Substance misuse

This includes those who misuse or who are dependent upon alcohol and other drugs of dependency including both prescription and legal/illegal drugs.

Personality disorders

This is a term which should only be used to describe people who have persistent severe problems throughout their adult life in dealing with the stresses and strains of normal life, maintaining satisfactory relationships, controlling their behaviour, foreseeing the consequences of their own actions and which persistently cause distress to themselves and other people.

Learning disability

This is a term used to describe people who have a life time evidence of intellectual and cognitive impairment, developmental delay and consequent learning disabilities. This is usually graded as mild, moderate or severe.

Overall psychiatric disorders are very common in the general population. The General Household Survey (2000), as reported by the Office of National Statistics (ONS 2002), reveals a prevalence of over 20% of these disorders. They are commoner in women than in men with the exception of substance misuse problems. However, the majority of psychiatric disorders in the community are mild to moderate conditions, particularly general anxiety and depression. Mild to moderate depressive illness and anxiety disorders are at least twice as common in women than in men and are particularly common in young women with children under the age of five. The majority of these disorders are managed in primary care and do not require the attention of specialist psychiatric services. Mild to moderate depressive illness and anxiety states respond to psychological treatments. Despite this, perhaps because of shortage of such treatments, prescription of antidepressants is widespread in the community, particularly among women.

Serious mental illnesses are less common. Both schizophrenia and bipolar illness affect approximately 1% of the population. Bipolar illness affects men and women equally. However schizophrenia, particularly the more severe chronic forms is commoner among men. These conditions require the attentions of specialist psychiatric services and require medical treatments as well as psychological care.

Psychiatric services are usually organized separately for adult mental health (serious mental illnesses), substance misuse (drug and alcohol treatment services) and learning disability. There are also, but not relevant to this chapter, separate services for psychiatric disorders in the elderly.

Psychiatric disorder in pregnancy

In general, psychiatric disorder in adults is not associated with a decrease in fertility. Therefore all the previously described psychiatric disorders can and do complicate pregnancy and the postpartum period. The prevalence of psychiatric disorder in young women means that at least 20% of women will have current or previous psychiatric disorder in early pregnancy. An equivalent number will also be taking psychiatric medication at this time. However, it can be seen that only a small number will have a past history of a serious mental illness and an even smaller number will be currently suffering from such an illness. Pregnancy is not protective against a recurrence or relapse of a previous psychiatric disorder particularly if the medication for these disorders is stopped when pregnancy is diagnosed. Women with a previous history of serious illness are at increased risk of a recurrence of that illness following birth. It is for these reasons that it is so important for midwives to enquire into women’s current and previous mental health at early pregnancy assessment. Table 36B.1 highlights the incidence of perinatal psychiatric disorders.

Table 36B.1 Incidence of perinatal psychiatric disorders

| Psychiatric disorder | (%) |

|---|---|

| ‘Depression’ | 15–30 |

| PND (postnatal depression) | 10 |

| Moderate/severe depressive illness | 3–5 |

| Referred psychiatry | 2 |

| Admitted to hospital | 0.4 |

| Admitted psychosis | 0.2 |

| Births to schizophrenic mothers | 0.2 |

Types of disorder in pregnancy

Mild–moderate conditions

The incidence (new onset) of psychiatric disorder in pregnancy is mostly accounted for by mild depressive illness, mixed anxiety and depression or anxiety states. These disorders present most commonly in the early weeks of pregnancy, becoming less common as the pregnancy progresses. They are probably predominantly of psychosocial aetiology, and for some women they will represent a recurrence of a previous episode, of depression, anxiety, panic or obsessional disorders. Women may also be vulnerable at this time because of:

In the past, it was often assumed that hyperemesis gravidarum (severe vomiting) was a psychosomatic manifestation of personal unhappiness and psychological disturbance. This condition is less common than in the past and usually resolves by 16 weeks of pregnancy. Psychological factors, anxiety and cognitive misattribution remain a significant factor in some women.

Prognosis and management

Most of the conditions are likely to improve as the pregnancy progresses. Psychological treatments and psychosocial interventions are effective for these conditions and caution needs to be exercised before pharmacological interventions are used during pregnancy, although medication may be necessary for the more severe illnesses.

For others, particularly those who develop a psychiatric illness in the later stages of pregnancy, their conditions are likely to continue and worsen in the postpartum period.

Serious conditions

This term refers to schizophrenia, other psychoses, bipolar illness (manic depressive illness) and severe depressive illness (unipolar depression or endogenous depression).

Incidence

Women are at a lower risk of developing a serious mental illness during pregnancy than at other times in their lives. This is in marked contrast to the elevated risk of suffering from such a condition in the first few months following childbirth (Kendell et al 1987). While these conditions are uncommon, they require urgent and expert treatment particularly as an acute psychosis in pregnancy can pose a risk to the mother and developing infant, both directly because of the disturbed behaviour and indirectly because of the treatments. There is a possibility that such an illness can interfere with proper antenatal care.

Prevalence

While new onset psychosis in pregnancy is relatively rare, the prevalence of these illnesses at the beginning of pregnancy will be the same as at other times. Women suffering from schizophrenia or bipolar illness are as likely to become pregnant as the rest of the general population. This means that approximately 2% of women in pregnancy will either have had such an illness in the past or be currently suffering from one. It is important to realize that these women may range from women who are well and stable, leading normal lives through to those who are disabled, chronically symptomatic and on medication. The management of these women in pregnancy therefore has to be individualized and plans made on a case-by-case basis. Nonetheless, there are three broad groups of women.

The first group includes women who have had a previous episode of bipolar illness or a psychotic episode earlier in their lives. They are usually well, stable not on medication and may not be in contact with psychiatric services. These women, if their last episode of illness was more than 2 years ago, may not be at an increased risk of a recurrence of their condition during pregnancy but face at least a 50% risk of becoming psychotic in the early weeks postpartum. The most important aspect of their management is therefore a proactive management plan for the first few weeks following birth.

The second broad group of women are those who have had a previous and/or recent episode of a serious mental illness, who are relatively well and stable but whose health is being maintained by taking medication. This may be antipsychotic medication or in the case of bipolar illness, a mood stabilizer (lithium or an anticonvulsant). These women are at risk of a relapse of their condition during pregnancy. This risk is particularly high if they stop their medication at the diagnosis of pregnancy. As some of these medications may have an adverse effect on the development of the fetus and yet an acute relapse of the illness also is hazardous, it is important that these women have access to expert advice on the risks and benefits of continuing the treatment or changing it as early as possible in pregnancy.

The third broad category includes women who are chronically mentally ill with complex social needs, persisting symptoms and on medication. These women will usually be in contact with psychiatric services. Midwifery and obstetric care needs to be closely integrated into the case management of these women and there needs to be a close working relationship between maternity, psychiatric and social services.

Ideally all women who have a current or previous history of serious mental illness should have advice and counselling before embarking upon a pregnancy. They should be able to discuss the risk to their mental health of becoming pregnant and becoming a parent as well as the risks to the developing fetus of continuing with their usual medication and perhaps the need to change it. However, in the general population, at least 50% of all pregnancies are unplanned at the point of conception. Midwives should therefore enquire at early pregnancy assessment about the women’s previous and current psychiatric history and alert psychiatric services as soon as possible about the pregnancy so that relapses of the psychiatric illness during pregnancy and recurrences postpartum can be avoided wherever possible.

Psychiatric disorder after birth

The majority of postpartum onset psychiatric disorders are affective disorders. However, symptoms other than those due to a disorder of mood are frequently present. Conventionally three postpartum disorders are described:

The ‘blues’ is a common dysphoric, self-limiting state, occurring in the first week postpartum (see Part A).

Puerperal psychosis

Puerperal psychosis, the most severe form of postpartum affective disorder has been recognized and described since antiquity. It leads to 2/1000 women being admitted to a psychiatric hospital following childbirth, mostly in the first few weeks postpartum. Although a relatively rare condition, there is a marked increase in the risk of suffering from a psychotic illness following childbirth (Kendell et al 1987). It is also remarkably constant across nations and cultures.

Risk factors

Most women who suffer from this condition will have been previously well, without obvious risk factors and the illness comes as a shock to them and their families. However, some women will have suffered from a similar illness following the birth of a previous child, some may have suffered from a non-postpartum bipolar affective disorder from which they have long recovered or they may have a family history of bipolar illness. For others there may be marked psychosocial adversity. It is generally accepted that biological factors (neuroendocrine and genetic) are the most important aetiological factors for this condition. This implies that puerperal psychosis can and does strike without warning, women from all social and occupational backgrounds – those in stable marriages with much wanted babies as well as those living in less fortunate circumstances.

Clinical features

Puerperal psychosis is an acute, early onset condition. The overwhelming majority of cases present in the first 14 days postpartum. They rarely arise within 48 hrs following birth and most commonly develop suddenly between day 3 and day 7, at a time when most women will be experiencing the ‘blues’. Differential diagnosis between the earliest phase of a developing psychosis and the ‘blues’ can be difficult. However puerperal psychosis steadily deteriorates over the following 48 hrs while the ‘blues’ tends to resolve spontaneously.

During the first 2–3 days of a developing puerperal psychosis there is a fluctuating rapidly changing, undifferentiated psychotic state. The earliest signs are commonly of perplexity, fear – even terror – and restless agitation associated with insomnia. Other signs include: purposeless activity, uncharacteristic behaviour, disinhibition, irritation and fleeting anger and resistive behaviour.

A woman may have fears for her own and her baby’s health and safety, or even about its identity. Even at this early stage, there may be, variably throughout the day, elation and grandiosity, suspiciousness, depression or unspeakable ideas of horror.

Women suffering from puerperal psychosis are among the most profoundly disturbed and distressed found in psychiatric practice (Dean & Kendell 1981). In addition to the familiar symptoms and signs of a manic or depressive psychosis, first-rank symptoms of schizophrenia – particularly primary delusions, delusional mood and delusional perception – are commonplace. Delusional ideas about the identity of loved ones, health professionals and even the baby can occur. Depressive delusions about maternal and infant health are commonplace. The behaviour and motives of others are frequently misinterpreted in a delusional fashion. An effect of perplexity and terror is often found, as are delusions about the passage of time and other bizarre delusions. Women can believe that they are still pregnant or that more than one child has been born or that the baby is older than it is.

Women often seem confused and disorientated. In the very common mixed affective psychosis, along with the familiar pressure of speech and flight of ideas, there is often a mixture of grandiosity, elation and certain conviction alternating with states of fearful tearfulness, guilt and a sense of foreboding. The sufferers are usually restless and agitated, resistive, seeking senselessly to escape and difficult to reassure. However, they are usually calmer in the presence of familiar relatives.

The woman may be unable to attend to her own personal hygiene and nutrition and unable to care for her baby. Her concentration is usually grossly impaired and she is distractible and unable to initiate and complete tasks. Over the next few days her condition deteriorates and the symptoms usually become more clearly those of an acute affective psychosis. Most women will have symptoms and signs suggestive of a depressive psychosis, a significant minority a manic psychosis and very commonly a mixture of both – a mixed affective psychosis.

Relationship with the baby

Some women are so disturbed, distractible and their concentration so impaired that they do not seem to be aware of their recently born baby. Others are preoccupied with the baby, reluctant to let it out of their sight and forever checking on its presence and condition. Although delusional ideas frequently involve the baby and there may be delusional ideas of infant ill health or changed identity, it is rare for women with puerperal psychosis to be overtly hostile to their baby and for their behaviour to be aggressive or punitive. The risk to their baby lies more from an inability to organize and complete tasks and to inappropriate handling and tasks being impaired by their mental state. These problems, directly attributable to the maternal psychosis, tend to resolve as the mother recovers.

Management

Most women with psychotic illness following childbirth will require admission to hospital, which should be to a specialist mother and baby unit, the only setting in which the physical needs of the mother who has recently given birth can be met and where specialist psychiatric nursing is available.

Prognosis

In spite of the severity of puerperal psychosis, they frequently resolve relatively quickly over 2–4 weeks. However, initial recovery is often fragile and relapses are common in the first few weeks. As the psychosis resolves, it is common for all women to pass through a phase of depression and anxiety and preoccupation with their past experiences and the implications of these memories for their future mental health and their role as a mother. Sensitive and expert help is required to assist women through this phase, to help them understand what has happened and to acquire a ‘working model’ of their illness. The overwhelming majority of women will have completely recovered by 3–6 months postpartum. However, they face at least a 50% risk of a recurrence should they have another child and some may go on to have bipolar illness at other times in their lives (Robertson et al 2005).

Postnatal depressive illness

Approximately 10% of all postnatal women will develop a depressive illness. The studies, from which this figure is derived, are usually community studies using the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale (EPDS) either as a diagnostic tool or as a screen prior to the use of other research tools. Studies using a cut-off point of 14 usually give an incidence of 10%; those using lower scores will give a higher incidence. A score on a screening instrument is not the same as a clinical diagnosis. Nonetheless a score of 14 is said to correlate with a clinical diagnosis of major depression and the lower scores with that of major and minor depression (Elliot 1994). The incidence of women who would meet the diagnostic criteria for moderate to severe depressive illness is lower, probably between 3% and 5% (Cox et al 1993). Depression following childbirth has the same range of severity and subtypes as depression at other times. According to the symptomatology, duration and severity, they may be graded as mild to moderate or severe, and subtypes may have prominent anxiety and obsessional phenomena.

Postnatal depressive illness of all types and severities is therefore relatively common and represents a considerable burden of disability and distress in these women. Although postnatal depressive illness is popularly accepted, with the exception of the most severe forms, it is no more common than during pregnancy or in non-childbearing women of the same age (O’Hara & Swain 1996). However, this does not detract from its importance. Depressive illness of any severity occurring at a time when the expectation is of happiness and fulfillment and when major psychological and social adjustments are being made together with caring for an infant, creates difficulties not found at other times in the human lifespan.

The term ‘postnatal depression’ (PND) is often used as a generic term for all forms of psychiatric disorder presenting following birth. While in the past, this has undoubtedly been helpful in raising the profile of postpartum psychiatric disorders, improving their recognition and reducing stigma, it has also become problematic. Use of the term in this way can diminish the perceived seriousness of other illnesses, and has led to a ‘one size fits all’ view of diagnosis and treatments (Oates 2001). The term postnatal depression should only be used for a non-psychotic depressive illness of mild to moderate severity which arises within 3 months of childbirth.

Severe depressive illness

Severe depressive illness with biological features affects at least 3% of all women who have given birth, a seven-fold increase in risk in the first 3 months (Cox et al 1993). Again, the majority of women who suffer from this condition will have been previously well. However, women with a previous history of severe postnatal depressive illness or severe depression at other times or a family history of severe depressive illness or postnatal depression are at increased risk. Psychosocial factors are more important in the aetiology of this condition than in puerperal psychosis, although biological factors play an important role in the most severe illnesses. Nonetheless, severe postnatal depression can affect women from all backgrounds not just those facing social adversity.

Like puerperal psychosis, severe depressive illness is an early onset condition in which the woman commonly does not regain her normal emotional state following birth. However, unlike puerperal psychosis, the onset tends not to be abrupt; rather, the illness develops over the next 2–4 weeks. The more severe illnesses tend to present early, by 4–6 weeks postpartum, but the majority present later, between 8 and 12 weeks postpartum. These later presentations may be missed. This is partly because some of the symptoms may be misattributed to the adjustment to a new baby and partly because the mother may ‘put on a brave face’ concealing how she feels from others.

Risk factors

A variety of risk factors for postnatal depressive illness have been identified and include those associated with depressive illness at other times. To these can be added ambivalence about the pregnancy, high levels of anxiety during pregnancy and adverse birth experiences, to name but a few. All of these risk factors, though statistically significant are so common as to have little positive predictive value. However a clustering of these risk factors might lead to those caring for the woman to be extra vigilant. Of more use are those risk factors which have a higher positive predictive value. These include a family history of severe affective disorder, a family history of severe postnatal depressive illness, developing a depressive illness in the last trimester of pregnancy and the loss of the previous infant (including stillbirth). There may also be an increased risk in those women who have conceived through IVF.

Clinical features

The familiar symptoms of severe depressive illness are often modified by the context of early maternity and the relative youth of those suffering from the condition:

The ‘somatic syndrome’ of broken sleep and early morning wakening, diurnal variation of mood, loss of appetite and weight, slowing of mental functioning, impaired concentration, extreme tiredness and lack of vitality can easily be misattributed to a crying baby, understandable tiredness and the adjustment to new routines.

The all pervasive anhedonia or loss of pleasure in ordinary everyday tasks, the lack of joy and fearfulness for the future may be misattributed by the woman herself to ‘not loving the baby’ or ‘not being a proper mother’ and all too easily described as ‘bonding problems’ by professionals. Anhedonia is a particularly painful symptom at a time when most women would expect to feel overwhelmed with joy and happiness and in turn contributes to feelings of guilt, incompetence and unworthiness that are very prominent in postnatal depressive illness. These overvalued ideas can verge on the delusional.

It is also common to find overvalued morbid beliefs and fears for the woman’s own health and mortality and that of her baby. She may misattribute normal infant behaviour to mean that the baby is suffering or does not like her. A baby that settles in the arms of more experienced people may confirm the mother’s belief that she is incompetent. Commonplace problems with establishing breastfeeding may become the subject of morbid rumination.

Some women with severe postnatal depressive illness may be slowed, withdrawn and retreat easily in the face of offers of help, avoid the tasks of motherhood and their relationship with the baby. Others may be agitated, restless and fiercely protective of their infant, resenting the contribution of others.

Anxiety and obsessive compulsive symptoms

Although women with pre-existing anxiety and panic disorder or obsessional compulsive disorder (OCD) frequently experience relapses or recurrences postpartum, it is not known whether there is an increase in incidence of these conditions following birth. Nonetheless, severe anxiety, panic attacks and obsessional phenomena are common following birth. These symptoms may dominate the clinical picture or accompany a postnatal depressive illness. They frequently underpin mental health crises, calls for emergency attention and maternal fears for the infant. Repetitive intrusive, and often deeply repugnant, thoughts of harm coming to loved ones, particularly the infant, are commonplace, often leading to repetitive doubting and checking. The woman may doubt that she is safe as a mother and believe that she is capable of harming her infant. Crescendos of anxiety and panic attacks may result from the baby’s crying or being difficult to settle and may lead the mother to be frightened to be alone with her child. This is easily misinterpreted by professionals who may fear that the child is at risk.

Obsessional, vacillating indecisiveness is also common and contributes to an overwhelming sense of being unable to cope with everyday tasks in marked contrast to premorbid levels of competence. While complex obsessive compulsive behavioural rituals are relatively rare, obsessive cleaning, housework and checking are very common. Intrusive obsessional thoughts and the typical catastrophic cognitions associated with panic attacks frequently lead to a fear of insanity and loss of control.

Relationship with the baby

Severe depressive symptomatology, particularly when combined with panic and obsessional phenomena can have a profound effect on the relationship with the baby, in many, but by no means all women. Most women who suffer from severe postnatal depression maintain high standards of physical care for their infants. However, many are frightened of their own feelings and thoughts and few gain any pleasure or joy from their infant. Most affected women feel a deep sense of guilt and incompetence and doubt whether they are caring for their infant properly. Normal infant behaviour is frequently misinterpreted as confirming their poor views of their own abilities. While a fear of harming the baby is commonplace, overt hostility and aggressive behaviour towards the infant is extremely uncommon. It should be remembered that the majority of mothers who harm small babies are not suffering from a serious mental illness. The speedy resolution of maternal illness usually results in a normal mother–infant relationship. However, prolonged chronic depressive illness can interfere with attachment and social and cognitive development in the longer term particularly when combined with social and mental problems (Cooper & Murray 1997).

Management

These conditions need to be speedily identified and treated, preferably by a specialist perinatal mental health team. The value of early contact with professionals who recognize and validate the symptoms and distress, and can re-attribute the overvalued ideas of the mother and instill hope for the future cannot be underestimated. The treatment of the depressive illness is the same as the treatment of depressive illness at other times. The use of antidepressants together with good psychological care should result in an improvement of symptoms within 2 weeks and the resolution of the illness between 6 and 8 weeks.

Prognosis

With treatment, these patients should fully recover. Without, spontaneous resolution may take many months and up to one-third of women can still be ill when their child is 1 year old.

Women who have had a severe depressive (unipolar) illness face a 1:2–1:3 risk of a recurrence of the illness following the birth of subsequent children (Cooper & Murray 1995). They are also at elevated risk from suffering from a depressive illness at other times in their lives. However, the long-term prognosis would appear to be better than when the first episode is in non-childbearing women, both in terms of the frequency of further episodes and in their overall functioning (Robling et al 2000).

Mild postnatal depressive illness

This is the commonest condition following childbirth, affecting up to 10% of all women postpartum. It is in fact no commoner after childbirth than among other non-child bearing women of the same age.

Risk factors

Some women who suffer from this condition will be vulnerable by virtue of previous mental health problems or psychosocial adversity, unsatisfactory marital or other relationships or inadequate social support. Others may be older, educated and married for a long time, perhaps with problems conceiving, previous obstetric loss or high levels of anxiety during pregnancy. Unrealistically high expectations of themselves and motherhood and consequent disappointment are commonplace. Also common are stressful life events such as moving house, family bereavement, a sick baby, experience of special care baby units and other such events that detract from the expected pleasure and harmony of this stage of life.

Clinical features

The condition has an insidious onset in the days and weeks following childbirth but usually presents after the first 3 months postpartum. The symptoms are variable, but the mother is usually tearful, feels that she has difficulty coping and complains of irritability and a lack of satisfaction and pleasure with motherhood. Symptoms of anxiety and a sense of loneliness and isolation and dissatisfaction with the quality of important relationships are common. Affected mothers frequently have good days and bad days and are often better in company and anxious when alone. The full biological (somatic subtype) syndrome of the more severe depressive illness is usually absent. However, difficulty getting to sleep and appetite difficulties, both over-eating and under-eating, are common.

Relationship with the baby

Dissatisfaction with motherhood and a sense of the baby being problematic are often central to this condition, particularly when compounded by difficulty in meeting the needs of older children. Lack of pleasure in the baby, combined with anxiety and irritability, can lead to a vicious circle of a fractious and unsettled baby, misinterpreted by its mother as critical and resentful of her and thus a deteriorating relationship between them. However, it should also be remembered that the direction of causality is not always mother to infant. Some infants are very unsettled in the first few months of their life. A baby who is difficult to feed and cries constantly during the day or is difficult to settle at night can just as often be the cause of a mild postnatal depressive illness as the result of it. Even mild illnesses, particularly when combined with socioeconomic deprivation and high levels of social adversity can lead to longer-term problems with mother–infant relationships and subsequent social and cognitive development of the child (Cooper & Murray 1997). A very small minority of sufferers from this condition may experience such marked irritability and even overt hostility towards their baby that the infant is at risk of being injured.

Management

Early detection and treatment is essential for both mother and baby. For the milder cases, a combination of psychological and social support and active listening from a health visitor will suffice. For others, specific psychological treatments, such as cognitive behavioural psychotherapy and interpersonal psychotherapy are as, if not more effective, than antidepressants as outlined in Antenatal and Postnatal Mental Health guidelines (NICE 2007).

Prognosis

With appropriate management, postnatal depression should improve within weeks and recover by the time the infant is 6 months old. However, untreated there may be prolonged morbidity. This, particularly in the presence of continuing social adversity, has been demonstrated to have an adverse effect not only on the mother/infant relationship but also on the later social, emotional and cognitive development of the child.

Treatment of perinatal psychiatric disorders

The role of the midwife

Midwives need knowledge and understanding of the different management strategies for perinatal psychiatric disorder and of the use of psychiatric drugs in pregnancy and lactation. This knowledge is required because the women themselves may wish for advice, because the midwife may have to alert other professionals, for example general practitioners and psychiatrists to ask for a review of the woman’s medication and because in case of serious mental illness, the midwife will be part of a multiprofessional team caring for the women.

Midwives should routinely ask all women at booking clinic whether they have had an episode of serious mental illness in the past and whether they are currently in contact with psychiatric services. Those women who have a previous episode of serious mental illness (schizophrenia, other psychoses, bipolar illness and severe [unipolar] depressive illness) should be referred to a psychiatric team during pregnancy even if they have been well for many years. This is because they face at least a 50% risk of becoming ill following birth. The midwife should also urgently inform the psychiatric team if the woman is currently in contact with psychiatric services. The psychiatric team may not be aware that their patient is pregnant. A woman who is taking psychiatric medication at the time when the midwife first sees her should be advised not to abruptly stop her medication. The midwife should urgently seek a review of the woman’s medication from the general practitioner, obstetrician or psychiatrist as appropriate. This may result in the woman being advised to reduce, change or undertake a supervised withdrawal of her medication.

There are three components to the management of perinatal psychiatric disorder: psychological treatments and social interventions, pharmacological treatments and the skills, resources and services needed.

Those who are seriously mentally ill will require all three. Those with the mildest illnesses may require only psychological and social interventions which can be carried out in primary care.

Psychological treatments

All illnesses of all severities and indeed those who are not ill but experiencing commonplace episodes of distress and adjustment need good psychological care. This can only be based upon an understanding of the normal emotional and cognitive changes and common concerns of pregnancy and the puerperium. It also requires a familiarity with the symptoms and clinical features of postpartum illnesses.

For most women with mild depressive illness or emotional distress and difficulties adjusting, extra time given by the midwife or health visitor, ‘the listening visit’, will be effective. For others, particularly those with more persistent states associated with high levels of anxiety, brief cognitive therapy treatments and brief interpersonal psychotherapy are as effective as antidepressants and may confer additional benefits in terms of improving the mother/infant relationships and satisfaction. Similar claims have been made for infant massage and other therapies that focus the mother’s attention on enjoying her infant. It is particularly important during pregnancy to use psychological treatments wherever possible and avoid the unnecessary prescription of antidepressants.

Social support

Lack of social support particularly when combined with adversity and life events has long been implicated in the aetiology of mild to moderate depressive illness in young women. Social support not only includes practical assistance and advice but also having an emotional confidante, female friends and people who improve self-esteem. There is evidence that organizations that are underpinned by social support theory, such as HomeStart and Sure Start can have a beneficial effect on maternal and infant well-being and perhaps on mild postnatal depression (Oakley et al 1996).

Pharmacological treatment

In general, psychiatric illnesses occurring during the perinatal period respond to the same treatments as at other times. There are no specific treatments for perinatal psychiatric disorder. Moderate to severe depressive illnesses respond to antidepressants, psychotic illnesses to antipsychotics and mood stabilizers may be needed for those with bipolar illnesses. However, the possibility of adverse consequences on the embryo and developing fetus and via breastmilk on the infant makes the choice and dose of the drug important.

The evidence base for the safety or adverse consequences of psychotropic medication is constantly changing both in the direction of increased concern and reassurance. Any text detailing specific advice is in danger of being quickly out of date and the reader is directed to the regularly updated information published by the National Teratology Information Service (NTIS) – via Toxbase website: http://www.spib.axl.co.uk and to NICE (2007) Guidelines on Antenatal and Postnatal Mental Health.

No matter what the changing evidence is, some general principles apply:

Antidepressants

Pregnancy

Tricyclic antidepressants (e.g. imipramine, lofepramine, amitriptyline and dosulepin) have been in use for 40 years. There is no evidence of harmful effects in pregnancy. Tricyclic antidepressants are not associated with an increased risk of fetal abnormality, early pregnancy loss or growth restriction when used in later pregnancy. However, newborn babies of mothers who were receiving a therapeutic dose of these antidepressants at the point of birth are at risk of suffering from withdrawal effects (jitteriness, poor feeding and on occasion fits). Consideration should therefore be given to a gradual tapering and reduction of the dose prior to birth.

Breastfeeding

The excretion of tricyclic antidepressants in breast milk is very low. However doxepin should not be used because it has been reported to cause sedation in babies. Any adverse effects in the fully breastfed newborn baby can be minimized by dividing the dose, e.g. 50 mg of imipramine t.d.s.

Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) (e.g. fluoxetine, paroxetine, citalopram) have been in use for approximately 15 years and are now the antidepressants most used in the treatment of depressive illness at other times.

There has been some recent concern about the possible adverse effects of certain SSRIs in early pregnancy. The evidence continues to emerge and the risks are therefore difficult to quantify. There may be an increased risk of miscarriage associated with the use of all SSRIs. It is likely that there is an increased risk of cardiac abnormalities related to 1st trimester exposure to SSRIs, particularly ventricular septal defects (VSD) and paroxetine (Seroxat). This has led to both the manufacturer and the drug regulation authorities in the USA and the UK advising against the use of paroxetine in pregnancy. At the moment, this restriction does not apply to fluoxetine (Prozac) and sertraline (Lustral) but it remains to be seen whether this adverse effect is related to all SSRI medications. The NICE (2007) guidelines therefore recommend that tricyclic antidepressants should be the treatment of choice if antidepressants are required during pregnancy. They also recommend that antidepressants should not be used for mild to moderate illness and that psychological treatments should be used wherever possible. However, the withdrawal of SSRI antidepressants in early pregnancy, particularly if the woman has been receiving them for some time is often associated with a withdrawal syndrome or the recurrence of her condition. In such circumstances, consideration should be given to changing the woman to a ‘safer’ alternative or reducing the dose and supervised withdrawal.

Continued use of SSRI medication during pregnancy has been associated with pre-term birth, reduced crown–rump measurement and lower birth weight. Babies born to mothers receiving SSRI medication at the point of birth are likely to experience withdrawal effects particularly those babies who are preterm. SSRIs, such as citalopram and fluoxetine that have a long half life are also associated with a serotonergic syndrome in the newborn (jitteriness, poor-feeding, hypoglycaemia and sleeplessness). Consideration should therefore be given to reducing and withdrawing this medication before birth.

Breastfeeding. The excretion of SSRIs in breastmilk is higher than that of tricyclic antidepressants. The fully breastfed newborn may be vulnerable to serotonergic side-effects. Those SSRIs with a long half life (fluoxetine and citalopram) should be avoided when breastfeeding the newborn. Venlafaxine and paroxetine are not recommended for use in breastfeeding mothers. However, in older and larger weight infants, particularly those who are partially weaned, other SSRIs particularly sertraline may be less problematic.

Tricyclic antidepressants should be the antidepressant of choice in breastfeeding.

Antipsychotics

There are two groups of antipsychotic medications, the older ‘typical’ antipsychotics (e.g. trifluoperazine, haloperidol, chlorpromazine) and the newer atypical antipsychotics (for example, risperidone, olanzapine, clozapine).

Typical antipsychotics

Pregnancy

Typical antipsychotics have been in use for 40 years. There is no evidence that their use in early pregnancy is associated with an increased risk of fetal abnormality nor that their continuing use in pregnancy is associated with growth restriction or pre-term birth. However, antipsychotic medication freely passes to the developing fetus and its brain and the dose should be reduced to that which is the minimum for clinical effectiveness. Babies born to mothers receiving relatively high doses of typical antipsychotics may experience a withdrawal syndrome and extra pyramidal symptoms (muscle stiffness, rigidity, jitteriness and poor feeding). Consideration therefore should be given to a reduction of the dose before birth and a possibility of induction at term. Withdrawal of medication at any stage in pregnancy may be associated with a risk of a relapse of the maternal condition.

Breastfeeding

Typical antipsychotics are present in breastmilk, although the amount to which the infant is exposed is likely to be very small. The added benefits of breastfeeding to the infant probably justify the continuation of breastfeeding providing that the dose required is small and divided. Drugs such as procyclidine, given to prevent extra pyramidal side effects, are not recommended.

Atypical antipsychotics

The manufacturers advise against the use of atypical antipsychotics in pregnancy and breastfeeding but this reflects lack of data rather than evidence of harm. The use of olanzapine in pregnancy has been associated with an increased risk of gestational diabetes. Women who become pregnant while taking these newer antipsychotics should be urgently reviewed. In some cases, it may be possible to change their medication to the older type of antipsychotic. In others, because of the substantial risk of relapse of their condition, it may be necessary to continue with their medication. Again this should be reduced to the lowest possible dose and consideration given to a further reduction immediately prior to birth and if necessary, a managed delivery. Clozapine should not be used in pregnancy and breastfeeding because of the risk of blood dyscrasias in the infant.

Mood stabilizers

This is a group of drugs used to treat the manic component of bipolar illness and longterm to prevent relapses of the condition. The drugs used as mood stabilizers are lithium carbonate (Priadel) and various anti-epileptic drugs commonly sodium valproate and carbamazepine but also on occasion lamotrigine.

Pregnancy

Lithium carbonate in pregnancy is associated with a substantial increased risk of developing a rare, serious cardiac condition, Ebstein’s anomaly. Although the relative risk is large, the absolute risk is low, 2/1000 exposed pregnancies. However, there is also an increased risk of a range of cardiac abnormalities including milder and less serious conditions. The absolute risk of all types of cardiac abnormality is 10/100 exposed pregnancies. Lithium in early pregnancy is not associated with an increased risk of neural tube abnormalities.

The continued use of lithium throughout pregnancy is associated with an increased risk of fetal hypothyroidism, diabetes insipidus, fetal macrosomia and the floppy baby syndrome (neonatal cyanosis and hypotonia). These risks are difficult to quantify. An additional problem is that the woman will require increasing doses of lithium in later pregnancy to maintain a therapeutic serum level because of the increased maternal clearance of lithium. However, the fetal clearance does not increase. Women receiving lithium in pregnancy therefore require frequent estimations of their serum lithium and close monitoring of their condition. During labour and immediately following birth, physiological diuresis can result in toxic levels of maternal lithium. The woman therefore requires frequent estimations of her serum lithium throughout labour and in the early postpartum days.

Women who are taking lithium carbonate should be advised to carefully plan their pregnancies and to seek medical advice. Abrupt cessation of lithium is associated with a substantial risk of a recurrence of their condition. These women will usually be advised to either slowly withdraw their lithium prior to conception or consider changing to another medication. However, there will be rare occasions when it is necessary to continue lithium throughout pregnancy. Such a pregnancy will need to be managed by an obstetrician working closely with psychiatric services and a fully compliant well informed patient.

Anticonvulsants

Anticonvulsants have been used as mood stabilizers for 30 years. Carbamazepine was first used in this way, sodium valproate is now increasingly the mood stabilizer of choice and recently the newer anticonvulsants such as lamotrigine and topiramate are being used.

Pregnancy

All anticonvulsants are associated with a doubling of the base-line risk of fetal abnormality if used in the first trimester of pregnancy. A total of 4/100 infants exposed to carbamazepine will have a major congenital malformation. The risk of cleft lip and palate is further increased with exposure to lamotrigine. The risks are highest with sodium valproate, 8/100 exposed pregnancies. The use of folic acid reduces but does not eliminate the risk of neural tube abnormalities. Continued use of anticonvulsants throughout pregnancy is associated with an increased risk of neurodevelopmental problems in the child. This is particularly high with sodium valproate. For this reason, NICE (2007) guidelines advise against the use of sodium valproate in pregnancy. Women receiving these medications should carefully plan their pregnancies with expert advice. They should, wherever possible, either have a supervised withdrawal of their medication or change to a ‘safer’ alternative. They should also take folic acid. If a woman becomes pregnant while still taking these medications, she should be urgently referred for expert advice and for an early fetal anomaly scan. As all harm is dose related, the woman should be advised wherever possible to reduce her sodium valproate to below 1000 mg daily.

Breastfeeding

The advantages of breastfeeding probably outweigh the risks of taking carbamazepine or sodium valproate during breastfeeding. However, the infant should be monitored for excessive drowsiness and in the case of sodium valproate, rashes. Lamotrigine should not be used in breastfeeding because of the increased risk of severe skin reactions in the infant.

Service provision

There are a number of national recommendations for the needs of women with perinatal psychiatric disorders (Table 36B.2). The distinctive clinical features of the conditions, their physical needs and the professional liaison with maternity services all require specialist skills and knowledge (Oates 1996). The frequency of the serious conditions at locality level makes it difficult for general adult psychiatric services to manage the critical mass of patients required to develop and maintain their experience and skills. It is difficult for maternity services to relate to multiple psychiatric teams. However, at supra-locality (regional) level, the frequency of serious perinatal psychiatric disorder is sufficient to justify the joint commissioning and provision of specialist services. Mothers, who require admission to a psychiatric hospital in the early months postpartum should, unless it is positively contraindicated, be admitted to a mother and baby unit. This is not only humane but also in the best interests of the infant and cost-effective as it shortens inpatient stay and prevents re-admission. There should be specialist perinatal community outreach services available to every maternity service, to deal with psychiatric problems that arise postpartum but also to see women in pregnancy who are at high risk of developing a postnatal illness.

Table 36B.2 Perinatal mental health: National Documents (regularly updated)

The majority of women suffering from postnatal mental illness will not require to be seen by specialist psychiatric services. However, there is a need for integrated care pathways to ensure that women are effectively identified and managed in primary care and if necessary, referred on to specialist services. There is a need to enhance the skills and competencies of health visitors, midwives, obstetricians and GPs to deal with the less severe illnesses themselves.

Prevention and prophylaxis

Prevention

The National Screening Committee (2001) and NICE guidelines (2007) do not recommend routine screening using the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale and other ‘paper and pen’ scales in the antenatal period for those at risk of postnatal depression. They also find that there is a lack of evidence to support antenatal interventions to reduce the risk of non-psychotic postnatal illness. In contrast, these and other bodies (DH 2004, Lewis 2007, NICE 2008) all recommend that women should be screened at early pregnancy assessment for a previous or family history of serious mental illness, particularly bipolar illness, because they face at least a 50% risk of recurrence of that condition following birth. Those who undertake early pregnancy assessment will need training to refresh their knowledge of psychiatric disorder.

There is little point in screening for women at high risk of developing severe postnatal illness if systems for the pro-active peripartum management of these conditions are not in place and if appropriate resources are not available. It is recommended that all women who are at high risk of developing a severe postpartum illness by virtue of a previous history are seen by a specialist psychiatric team during the pregnancy and a written management plan placed in the maternity records in late pregnancy and shared with the woman, her partner, her general practitioner, midwife, obstetrician and psychiatrist.

Prophylaxis

If a woman has a previous history of bipolar illness or puerperal psychosis, consideration should be given to starting medication on day one postnatally. For bipolar illness the use of lithium carbonate has been shown to reduce the risk of a recurrence. It is plausible that the use of antipsychotic medication may also reduce the risk of recurrence. However, lithium is not compatible with breastfeeding. Some women will not wish to take medication when they perceive there is 50% chance of them remaining well. They may also place a priority on continuing to breastfeed. Breastfeeding mothers at risk of developing a bipolar or mixed affective illness may take carbamazepine or sodium valproate. The evidence that antidepressants taken prophylactically may prevent the onset of a depressive psychosis is lacking. Antidepressants should be used with great caution in any woman who has bipolar disorder in her personal or family history because of the propensity of antidepressants to trigger a manic illness.

Hormones

There is no evidence that progesterone, natural or synthetic, prevents or treats postnatal depression or puerperal psychosis. Indeed there is evidence to suggest they may cause depression. While there is some evidence that transdermal oestrogens are effective in treating postnatal depression the potential adverse physical effects (Dennis et al 1999) and the known efficacy of antidepressants mean this should not be the treatment of choice.

The most important aspect of preventative management and one that will promote early identification and the avoidance of a life threatening emergency is close surveillance and contact in the early weeks, the period of maximum risk. A specialist community perinatal psychiatric nurse together with the midwife should visit on a daily basis for the first two weeks and remain in close contact for the first six. The local mother and baby unit should be aware of the woman’s expected date of birth and systems put in place for direct admission if necessary.

The Confidential Enquiries into Maternal Deaths: psychiatric causes of maternal death

The last three Confidential Enquiries into Maternal Deaths (Oates 2001, 2004, 2007) have found that in those cases reported to the Enquiry, suicide and other psychiatric causes of death were the second leading cause (indirect) of maternal death in the UK between 1997 and 2005. However, in the case of the 2001 and 2004 Reports, if those additional deaths ascertained by the Office of National Statistics Linkage Study are included, then suicide emerges as the leading cause of maternal death (15%). Psychiatric causes contribute 25% of all maternal deaths.

Maternal suicide is commoner than previously thought. Overall, the maternal suicide rate appears to be equivalent to that of the general rate in the female population. Suicide in pregnancy is uncommon. The majority of suicides took place in the year following birth, most in the first 3 months. Not only is the assumption of the ‘protective effect of maternity’ called into question but also the relative risk of suicide for seriously mentally ill women following childbirth is substantially elevated. An elevated standardized mortality ratio (SMR) of 70 for women with serious mental illness in the postpartum year has previously been reported (Appleby et al 1998) and further confirmed by evidence from the Enquiries with improved case ascertainment.

In contrast to other causes of maternal death, suicide was not associated with socioeconomic deprivation. The majority of suicides were older, married and relatively socially advantaged and seriously ill. A worrying number were health professionals. This underlines the error of merging issues of maternal mental health with those of socioeconomic deprivation.

The majority of the suicides occurred violently by jumping from a height or by hanging. This stands in contrast to the commonest method of suicide among women in general (self-poisoning), and underlines the seriousness of the illness from which the women died.

Half of the suicides had a previous history of admission to a psychiatric hospital. In few cases had this risk been identified at booking and in even fewer had any proactive management been put into place. Had their illnesses been anticipated, a substantial number of these deaths might have been avoided.

Women also died from other consequences of psychiatric disorder. Some of these were due to accidental overdoses of illicit drugs. However, deaths also occurred from physical illness that would not have occurred in the absence of a psychiatric disorder. Some of these were the physical consequences of alcohol or illicit drug misuse, others from side effects of psychotropic medication. However, a worrying number of deaths, some of which took place in a psychiatric unit, were due to physical illness being missed because of the psychiatric disorder or mistakenly attributed to a psychiatric disorder. These findings underline the importance of remembering that physical illness can present as or complicate psychiatric disorder. Suicide is not the only risk associated with perinatal psychiatric disorder. Box 36B.2 identifies the four main categories of psychiatric deaths emerging from ‘Saving Mothers’ Lives’ (Oates 2007).

Box 36B.2 The 4 main categories of psychiatric deaths emerging from ‘Saving Mothers’ Lives’ (Oates 2007)

Note: New themes are included concerning child protection and termination of pregnancy.

These findings have major implications for psychiatric and obstetric practice. If psychiatrists discussed with their patients plans for parenthood prior to conception; if obstetricians and midwives detected those at risk of serious mental illness; if psychiatric and maternity professionals communicated freely with each other and worked together; if specialist perinatal mental health services were available for those women who needed them and if all had a greater understanding of perinatal mental illness, then not only would a substantial number of maternal deaths be avoided but also the care and outcome of other mentally ill women would be greatly improved.

Conclusion