Chapter 37 Contraception and sexual health

Contraception is an important part of the lives of many women, with needs varying according to age. For many people throughout the world, control of their own fertility is difficult as they do not have access to contraception. The National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence UK (NICE) guidelines (2005) describe how important it is for women to make an informed choice about what type of contraceptive method will suit their lifestyle best. Information should be appropriate for people with additional needs, for example people with physical, sensory or cognitive needs and those who do not speak or read English or who have different cultural or religious requirements. In 2004, the government recognized that sexual health services needed to be improved, and in their white paper ‘Choosing Health: Making Healthy Choices Easier’ (DH 2004) they promised a review of sexual health services followed by investment to meet gaps in local services. This should ensure a full range of contraceptive services become available and that services are modernized.

The role of the midwife

The midwife has a unique and pivotal role in discussing contraception and sexual health. The Nursing and Midwifery Council (2004) in the UK states that one of the activities of a midwife is ‘to provide sound family planning information and advice’. Midwives, who are encouraged to take on a wider public health role, are in a key position to create and use opportunities to enable women to express their needs.

The Royal College of Midwives (2000) feel that the most appropriate time to discuss sexual health, resumption of sexual activity and contraception will, in some respect, be dependent on the individual woman. Issues such as loss of libido, adjustment to motherhood, breastfeeding, discomfort of the perineum, vaginal dryness and body image may influence choice and use of a particular method of contraception. The use of a leaflet from the Family Planning Association (FPA) is helpful; the leaflets are clear to understand in both illustration and language.

The knowledge the midwife has about a client will enable her to appreciate influences such as religion, culture, relationships, lifestyle, age, motivation and socioeconomic status, which all affect the choices she will make. The midwife should be familiar with the contraception and sexual health services available in the area in which she practises and know the system of referral to these specialist services.

For most contraceptive methods discussed in this chapter, the failure rate is given per 100 woman years (HWY). This is the number who would become pregnant if 100 women used the method for 1 year. This rate does not reflect the fact that fertility decreases with age and may be suppressed during lactation, or that the success of a method is partially dependent on motivation, experience of using the method and the teaching received on its use. Unprotected intercourse results in 80–90 pregnancies per HWY. Barrett et al (2000) suggest health professionals assume that women will resume intercourse soon after childbirth and consequently discuss contraception, however, at 6 weeks postnatal as many as 60% of women will not have resumed intercourse. Discussions need to take place well before this time to ensure no unintended pregnancies occur. Some mothers may even appreciate information on contraception in the antenatal period, to give them plenty of time to decide which contraceptive method would be right for them. Partnership working between the new mother and midwife is essential, conversations regarding contraception should take place in a quiet, relaxed setting, with the midwife having up-to-date knowledge on all methods available.

In Britain, all contraception is available free of charge from the National Health Service. This is different in other parts of the world, with a range of charges for contraception.

Hormonal contraceptive methods

The combined hormonal contraceptive pill

The combined oral contraceptive pill (COC or ‘the pill’) (Fig. 37.1) came as a break-through in 1960 and it has proven to be effective and safe. It is the most popular method of contraception in Europe, used by approximately 25 per cent of sexually active couples in Britain, France and Germany. Around 100 million women rely on the pill worldwide (Guillebaud 2004).

The combined pill contains the synthetic steroid hormones oestrogen and progestogen. All COCs available in the UK contain ethinyl oestradiol, with the exception of Norinyl-l, which contains mestranol. There is a variety of COCs available containing different progestogens. This accounts for subtle differences in their biological effects and provides women with a wide choice. The most commonly used pills in the UK are monophasic pills, which deliver a constant dose of steroids throughout the packet. ‘Everyday’ pills contain 28 pills in the packet, 21 of which are active monophasic pills while the seven remaining pills contain no hormones.

Also available are biphasic and triphasic pills, in which the dose of steroids administered varies in two or three phases throughout the packet to mimic the natural fluctuations of the hormones during the menstrual cycle. These pills are less commonly used in Britain.

The first generation COC pills contained large doses of oestrogen and were associated with a high risk of deep vein thrombosis. They were replaced in the late 1960s with pills that had low doses of oestrogen and progestogen. They were equally as effective as the earlier pills, much safer and well-tolerated. The progestogens in these second generation pills were norethisterone and levonorgestrel. The third generation pills, which came along in the mid-1980s, contained a variety of new synthetic progestogens, which appeared to have better effects on ce:anchor id="p707"/>serum lipid profiles. Among these were desogestrel and norgestimate, which were also less androgenic; gestodene, which was the most potent and which achieved the best cycle control and cyproterone acetate, which is anti-androgenic but licensed only as a treatment for acne. Drospirenone has been the most recent addition, included from the late 1990s, with mild antimineralocorticoid activity to counteract oestrogen-induced water retention. It is also anti-androgenic.

Mode of action

COCs work primarily by preventing ovulation. The first seven active pills in a packet inhibit ovulation. The remaining pills maintain anovulation, according to the Faculty of Family Planning and Reproductive Healthcare (FFPRHC 2006a).

Oestrogen and progestogen suppress follicle stimulating hormone (FSH) and luteinizing hormone (LH) production causing the ovaries to go into a resting state; the ovarian follicles do not mature and ovulation does not normally take place. Progestogen also causes the cervical mucus to thicken, making penetration by spermatozoa difficult. The pill renders the endometrium unreceptive to implantation by the blastocyst. These actions provide additional contraception in the event of breakthrough ovulation occurring.

Failure rate

Provided that the pill is taken correctly and consistently, is absorbed normally and interaction with other medication does not affect its metabolism, its reliability is almost 100% (Guillebaud 2004).

Important considerations

The pill is a reliable contraceptive, which is independent of intercourse and has many advantages. Healthcare providers should manage consultations for contraceptive pills with due regard for the woman’s personal context and contraception experience. The woman’s ideas, concerns and expectations should be addressed and information should be provided to correct any mistaken notions and perceptions about risks.

Additional benefits of taking the combined oral contraceptive pill, in the short term, are regular, lighter, less painful periods, possible reduction in premenstrual symptoms, protection against pelvic inflammatory disease (PID) – because of the thickened cervical mucus, decreased incidence of ectopic pregnancy and reduced risk of benign breast disease. Taken long term, COC pills offer protection against ovarian and endometrial cancers (International Agency for Research on Cancer 2005) and prevent ovarian cysts and fibroids (Szarewski & Guillebaud 2000).

Use of the COC pill may lead to side-effects such as breast tenderness, nausea, weight increase, depression and loss of libido. These effects often diminish with continued use or may improve with a change of pill. There is a speculative idea that vegetarians have less gut bacteria flora population and consequently less enterohepatic circulation of oestrogen (Guillebaud 2004).

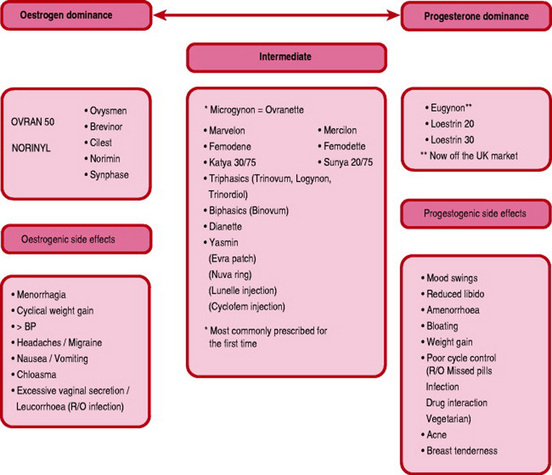

A basic knowledge of the side-effects attributable to the components of the COC pill is helpful when making decisions about changing pills.

Oestrogen dominance in a pill may cause water retention, resulting in breast tension, mild headaches, elevated blood pressure and cyclical weight gain. It may also be responsible for nausea and vomiting, excessive vaginal secretion (leucorrhoea) and skin pigmentation similar to chloasma.

The progestogens may lower mood and libido, provoke acne and seborrhoea and cause mastalgia.

The vast majority of women experience no adverse effects. Every woman is unique in their biological response and also in their perception and tolerance of side-effects. Many women discontinue using contraceptives if they experience side-effects, even if those side-effects seem only subjective or trivial to the providers (Kubba 2005). Most of these women will then use a less effective method of contraception and run the risk of unplanned pregnancy. Women who find any side-effect intolerable should be provided with information about other options and concordance ensured.

The metabolic effects of the COC pill can occasionally result in major side-effects. The risk of venous thromboembolism (VTE) is higher in women with a BMI over 30, heavy smokers, those with a previous history of deep vein thrombosis or a family history of venous thrombosis and those who are immobile. The absolute risk of VTE with COC use remains very small, estimated at 15–25/100 000 woman-years.

The progestogens in third generation COC pills were reported to be associated with an increased risk of venous thromboembolism. A meta-analysis by Kemmeren et al (2001) supported this view. Presenting the risks of VTE for different pills in relative terms may sound alarming, as was the case with the ‘pill scare’ of 1995. The news media described the risk of VTE as ‘double’. The risks of VTE with the COC pill, in absolute terms, recognize the rarity of VTE in women of reproductive age (Table 37.1).

Table 37.1 Risks of venous thromboembolism

| Risk of VTE per 100 000 woman years | |

|---|---|

| Not using COC | 5 |

| Using second generation COC containing norethisterone or levonorgestrel | 15 |

| Using third generation COC containing desogestrel or gestodene | 25 |

| In pregnancy | 60 |

The Committee of Safety of Medicine, UK (2004) concluded that the risks of VTE with all COCs are very small and practically similar. Therefore, any of them may be prescribed first line.

Some women may develop a significantly high blood pressure, which could increase the potential for haemorrhagic stroke and myocardial infarction. Hypertension with blood pressure (BP) between 141/91 mmHg and 159/94 mmHg is considered to be a level of risk, which outweighs the benefits of using the COC. Hypertension with BP of 160/95 mmHg or higher poses an unacceptable health risk with COC use (FFPRHC 2006a).

Cigarette smoking is known to potentiate most of the risks associated with COC pill use such as ischaemic and haemorrhagic stroke and myocardial infarction (Dunn et al 1999).

Following re-analysis of worldwide epidemiological data, women currently using the COC pill are considered to be at a slightly increased risk of developing breast cancer (Collaborative Group on Hormonal Factors in Breast Cancer 1996). Another population-based, case control study found that current COC users appear to have no increased risk compared with those who have never used the COC pill (Marchbanks et al 2002). Any excess risk of breast cancer associated with COC use declines in the first 10 years after discontinuing the pill.

Studies show a small increase in the relative risk of cervical cancer, which is associated with a long duration of use (Beral et al 1999). However, the effects of confounding factors such as sexually transmitted infections (STI), non-use of barrier methods and a high number of sexual partners complicate our understanding of the influence of the COC.

Contraindications to COC pill use are pregnancy, undiagnosed abnormal vaginal bleeding, history of arterial or venous thrombosis (or predisposing factors such as immobility), hypertension, focal migraines, current liver disease, hydatidiform mole (until serum HCG is no longer detectable), smoking (if the woman’s age is over 35 years) and BMI over 39.

This is not an exhaustive list. As the pill is not suitable for everyone, women wishing to consider using this form of contraception should have a full history recorded and be fully informed and counselled regarding possible side-effects.

Using the COC pill

When initially commencing the pill, the very first pill is usually taken on the first day of the menstrual period (for postpartum use, see later). Starting on any day up to the 5th day is just as good, provided the first seven pills are taken correctly (Schwarz et al 2002). If a 21-day pill has been prescribed, the contraceptive effect is immediate, provided that the remainder of pills in the packet are taken correctly. If the pill is initially commenced on any day beyond the 5th day of the cycle, additional contraception (such as a condom) should be used, in conjunction with the pill, for the first 7 days. One pill is taken every day for 21 days, then no pills for the next 7 days. Vaginal bleeding usually occurs within the 7-day break, before the next packet of pills is commenced.

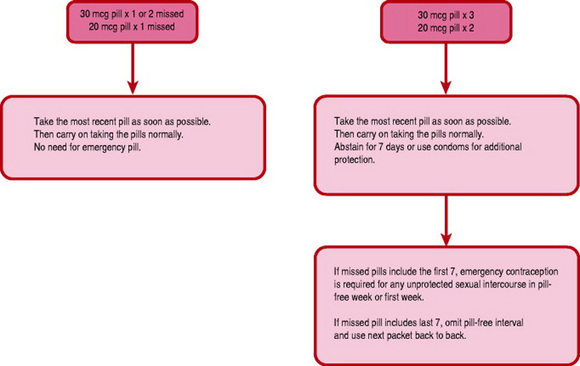

When commencing the everyday (ED) COC pill, the active pills are taken first. One pill is taken daily, with care being taken to take the pills in the correct order. Vaginal bleeding will usually occur when the inactive pills are taken, which are usually denoted by a different coloured section on the pill packet. If the pill is forgotten by >12 hrs, the advice given in Figure 37.2 should be followed. If a pill is forgotten from the beginning or end of a packet the pill free interval is lengthened and ovulation may be more likely to occur. If a woman is concerned about a missed or late pill, she can contact the local contraception clinic or GP for reassurance or advice, as emergency contraception may be indicated (see later).

Other factors, which may render the pill less effective, include interaction with other medication, vomiting within 3 hrs of taking a pill and severe diarrhoea. Medications that may hinder the effectiveness of the pill include broad-spectrum antibiotics (such as ampicillin), liver-enzyme-inducing drugs such as rifampicin, some anticonvulsants and some herbal remedies, for example St John’s wort.

After absorption, synthetic oestrogen and progestogen are transported to the liver via the portal vein. Liver-enzyme-inducing drugs reduce the efficacy of the pill by increasing the metabolism, and subsequent elimination of oestrogen and progestogen in the bile. Some newer antiepileptics are not enzyme inducers but the COC pill may reduce seizure control with lamotrigine.

Broad-spectrum antibiotics may reduce the gut flora, which free up oestrogen excreted in bile to be reabsorbed. If antibiotics impair the enterohepatic circulation, the oestrogen is disposed of, thereby reducing the amount available in the body for contraception.

The advice to be given in cases of an illness with severe vomiting and diarrhoea is to use additional contraception during the illness and for 7 days afterwards. It is important that women are made aware of possible drug interactions and inform their medical practitioner that the COC pill is being taken whenever other medications are prescribed.

Preconception considerations

It is useful to wait for one natural period after stopping the pill before trying to get pregnant as dating the pregnancy can be more accurate and pre-pregnancy care can begin.

Postpartum considerations

The combined oral contraceptive pill reduces milk supply, particularly if lactation is not well established and is therefore not recommended for use in the early months in lactating women. If the mother is bottle-feeding, the COC pill may be commenced 21 days postpartum. This allows the high oestrogen levels of pregnancy to fall before introducing the pill (Guillebaud 2004), thus reducing the risk of thromboembolism, but allowing the contraceptive effect to be initiated before ovulation resumes. Women who have experienced pregnancy-induced hypertension may use the combined oral contraceptive pill once their blood pressure has returned to normal levels (Speroff & Darney 2001). Women who have experienced severe pregnancy-induced hypertension with persistent biochemical abnormalities are at greater risk of thrombosis and, if no alternative method is acceptable, should delay starting the pill until at least 8 weeks postpartum (Guillebaud 2004).

The COC pill can be commenced immediately following spontaneous abortion or therapeutic termination of pregnancy. Due to the risk of thromboembolism, the COC pill should be stopped 4 weeks before major surgery and a progestogen-only method of contraception used; if this is not possible then thromboprophylaxis and compression hosiery are advised. Women who have minor surgery do not need to discontinue the pill.

Further postpartum considerations for discussion with the mother may include whether remembering to take the pill will fit into her current lifestyle and if she can easily access a clinic or surgery.

Research evidence for optimum follow-up intervals is lacking but blood pressure recordings must be reviewed. Common practice is to check the blood pressure at about 10–12 weeks after the initial visit and then at 6-monthly intervals. If this proves difficult for the woman, she may be referred to a domiciliary family planning service, if available, or her health visitor.

The combined hormone injectable (Lunelle)

Lunelle contains 25 mg medroxyprogesterone acetate and 5 mg estradiol cypionate. It is not yet licensed in the UK. It is commenced on the 1st day of a period or within 7 days, and given every 28–33 days. It is very effective and reversible. Side-effects include break-through bleeding and weight gain. The efficacy is comparable with perfect use of the COC pill.

The combined hormone patch

The combined hormone patch (EVRA) was licensed in the UK in 2003. One patch is used weekly for 3 weeks followed by 1 week patch-free. It is particularly suitable for women who are unable to tolerate oral medications and those with malabsorption syndrome. It releases 20 μg of ethinyl oestradiol and 150 μg of norelgestromin per 24 hrs. Compliance and cycle control may be improved. The efficacy is comparable with the COC pill. The patch may be worn on most places on the body except the breasts. It is extremely sticky and should stay on during showering or swimming.

The FPA (2005a) suggest it may be used from day 28 in the postnatal period. If the mother is breastfeeding, the patch should not be recommended as it will reduce breastmilk production.

The combined hormone vaginal ring

The combined hormone vaginal ring (NuvaRing) is inserted into the vagina during the first 7 days of the cycle and is used for 3 weeks continuously, followed by 1 week free of its use. It releases 15 μg of ethinyl oestradiol and 120 μg of etonogestrel per 24 hrs. It is not yet licensed in the UK. It seems to be acceptable to many women and well tolerated (Novak et al 2003). Compliance and cycle control were remarkably good in clinical trials (Dieben et al 2002). The efficacy is comparable with the COC pill.

The progestogen-only pills

Progestogen-only pills (POP) were introduced partly to avoid the side-effects of oestrogen in the combined pill, as discussed earlier. They also offer increased choice for women. Currently available in the UK are the older preparations, which contain norethisterone (Noriday, Micronor), etynodiol diacetate (Femulen) and levonorgestrel (Norgeston, Microval) and the new anovulant progestogen-only pills containing desogestrel (Cerazette). All have lower doses of progestogen compared with the COC pill.

Mode of action

The POP exerts its contraceptive effects at different levels. The cervical mucus is viscid, making it impenetrable to spermatozoa; the endometrium is modified to prevent implantation. The older POPs have been shown to suppress ovulation in about 40% of women. The new POP, Cerazette is anovulant and also suppresses FSH and LH consistently.

Drawbacks to the POPs use include menstrual disturbances, encompassing unpredictable and quite often prolonged bleeding, oligomenorrhoea or amenorrhoea. Little is understood about the mechanism of erratic uterine bleeding, which most women experience to some degree. The menstrual disruption is the most common reason for discontinuation of progestogen-only methods. This indicates the need for careful explanation of the drawbacks to potential users.

An increased prevalence of functional ovarian cysts has been demonstrated in women using progestogen-only pills. These may settle with continuation of use and will resolve if the POP is discontinued.

Contraindications to the use of POP are pregnancy, undiagnosed abnormal vaginal bleeding, severe arterial disease and hydatidiform mole (until serum HCG is no longer detectable). The rate of ectopic pregnancy in women using the progestogen-only pill is no higher than in women using no contraception; however, the POP prevents uterine pregnancy more effectively than tubal pregnancy. This is not a problem with the anovulant POP Cerazette.

Antibiotics do not adversely affect progestogen-only methods of contraception but women should be advised to consult the doctor regarding possible interactions if any other medications (especially enzyme inducers such as rifampicin) are prescribed.

Postpartum consideration

POP may be started 21 days postpartum for contraception. They have no adverse effect on lactation. Secretion of the hormone in breastmilk and absorption by the neonate is minimal and does not affect the short-term growth and development of infants. The POP can be used immediately following spontaneous or therapeutic termination.

Using the POP

The POP is taken every day; there are no pill-free days and thus tablets are taken throughout periods. If the first tablet is taken on the 1st day of menstruation the contraceptive effect is immediate. If the POP is started on any other day of the cycle then additional contraception, e.g. a condom should be used for the first 7 days.

If a pill is forgotten, the woman has only 3 hrs in which to remember to take it. This is because the effect on cervical mucus is at its maximum between 4 and 22 hrs, and lapses by 27 hrs after the tablet has been taken. For this reason, it is also recommended that the daily tablet be taken about 4 hrs before the usual time of intercourse and at the same time each day. If the woman is over 3 hrs late in taking a tablet, she should continue taking her pills and use additional contraception for the next 7 days. The leeway for the anovulant POP Cerazette is up to 12 hrs.

Following vomiting or severe diarrhoea, additional contraception should be used until 7 days after the illness ceases. Women concerned about missed or late pills should be advised to contact their family planning clinic or GP, as emergency contraception may be indicated (see later). The effects of broad-spectrum antibiotics on the gut flora do not affect the action of the POP.

Failure rate

The effectiveness of the older POP is dependent upon meticulous compliance. Vessey et al (1985) found that the failure rate of this method is clearly related to age, with failure rates ranging from 3/HWY in a population aged 25–29 to only 0.3/HWY in women aged 40 years or over. For women under 25, the failure rate is approximately 4/HWY, suggesting this method is less appropriate for younger women. The new anovulant POP Cerazette has a failure rate of less than 1/HWY.

Long acting reversible contraception

Contraceptives that are used daily or weekly sometimes fail because of non-adherence or incorrect use. The NICE guidelines (2005) recommend giving women wider access to long acting reversible contraceptive (LARC) methods, as a feasible way to reduce unintended pregnancy. Long-acting reversible contraceptive methods, usually referred to as LARC, are considered to be more reliable and cost-effective than other methods.

LARC includes injectable progestogen contraceptives, intrauterine devices, intrauterine hormonal systems and subdermal contraceptive implants. These are all available in the UK but usage is currently low due to inadequate awareness of their availability and access. Most general practitioners and practice nurses do not fit implants and intrauterine methods.

For a long acting method to be initiated, informed choice is crucial because only women who have realistic expectations may tolerate protracted side-effects. The implants and intrauterine systems are expensive, therefore, a reasonable continuation rate is pertinent.

Progestogen injections

The two contraceptive progestogen injections currently available in the UK are depo Provera or depot medroxyprogesterone acetate (DMPA) and Noristerat (norethisterone enanthate). Both methods are given by deep intramuscular injection.

DMPA is the method of choice for many women, not simply those for whom other methods are contraindicated. Over 6 million women use this method worldwide and in some countries it is the most commonly used reversible method. In the UK, <5% of women attending contraception clinics use injectables. The progestogen injections prevent ovulation, thicken cervical mucus and atrophy the endometrium.

Depot medroxyprogesterone acetate

This is the most commonly used injectable and is given in a 150 mg dose at 12-week intervals. It is released slowly from the injection site into the circulation. The failure rate is 0.2/HWY. Prolonged spotting is a common side-effect in the first year but amenorrhoea often prevails in long-term use. Some DMPA users experience other side-effects such as breast discomfort, nausea, vomiting, weight gain, seborrhoea, acne and mood swings. It is now recognized that amenorrhoea for >2 years with DMPA is associated with chronic low serum oestrogen and reduced bone density. All women choosing DMPA should be aware of this information. Teenagers, who may not yet have attained peak bone mass, should preferably use other methods. The peak bone mass is attained around the age of 30 years (Teegarden et al 1995). Women who have been amenorrhoeic for more than 3 years on DMPA may have their bone density checked with dual X-ray absorptiometry (DEXA) scan. It may be reassuring to learn that reduced bone mineral density (BMD) on DMPA does not progress indefinitely but it stabilizes after about 5 years. The BMD returns to normal after discontinuation (Scholes et al 2005).

DMPA offers additional health benefits for women with homozygous sickle cell haemoglobinopathy by reducing haemolytic and bone pain crises (Serjeant 1985).

After discontinuation of DMPA, there may be a delay in the return of fertility for up to 18 months.

Using injectable progestogens

The initial injection is given within the first 7 days of the menstrual period and the contraceptive effect is immediate. If given at any other time, the practitioner must ensure that there is no likelihood of pregnancy already and advise that additional contraception is used for the next 7 days (WHO 2002).

Specific considerations

This method is irreversible for the time of action; therefore any side-effects may be present until the injection wears off. The efficacy of DMPA is not affected by concurrent use of liver enzyme inducing medications, as hepatic clearance is practically perfect.

Subdermal contraceptive implants

Contraceptive implants have been used internationally for several years. Norplant was used in the UK from 1993 and replaced by Implanon from 1999.

Using implants

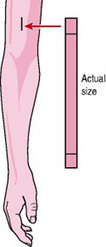

Implants are capsules containing progestogen, which are inserted, under local anaesthetic, into the inner aspect of the non-dominant upper arm (Fig. 37.3). The steroid is released into the circulation, producing a change in the cervical mucus which prevents spermatozoa penetration, disturbance of the maturation of the endometrium and suppression of ovulation.

Norplant has six capsules containing levonorgestrel (Norplant 2, also marketed as Jadelle, has two capsules). Norplant and Jadelle are effective for 5 years and still available in some countries. Implanon is a single contraceptive rod containing 68 mg of 3-keto desogestrel (etonogestrel). It should be inserted during the first 7 days of the menstrual cycle and no additional contraceptive cover is required. Ovulation is suppressed within 24 hrs. It is effective for 3 years but can be removed at any time if the woman wishes. After removal, the serum is cleared of etonogestrel within 1 week and fertility is regained promptly.

Failure rate

Norplant has a cumulative failure rate of 0.2/HWY. Implanon has practically zero failure rates if instructions are followed (Guillebaud 2004). Reported implant failures are often due to interaction with enzyme inducing medications used concurrently, unrecognized failure to insert the implant at all and unnoticed pregnancy before the fitting.

Specific considerations

Irregular bleeding is the most common problem for women using this method. Only 20–30% of users become amenorrhoeic. Headache, seborrhoea, acne and mood swings have also been reported as side-effects. Insertion and removal require a minor surgical procedure, with accompanying risks of bleeding and infection. These aspects should be discussed prior to the woman making her decision. Counselling before fitting and during use appears to be the only way to reduce premature discontinuation due to the side-effects.

Preconception considerations

The action of the implant is quickly reversible and ovulation can return within 21 days of removal (Croxatto & Makarainen 1998). This makes it suitable also for women wishing to ‘space’ pregnancies.

Intrauterine contraceptive device (IUCD)

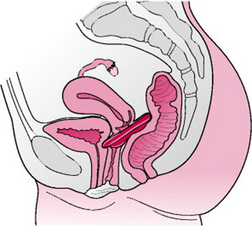

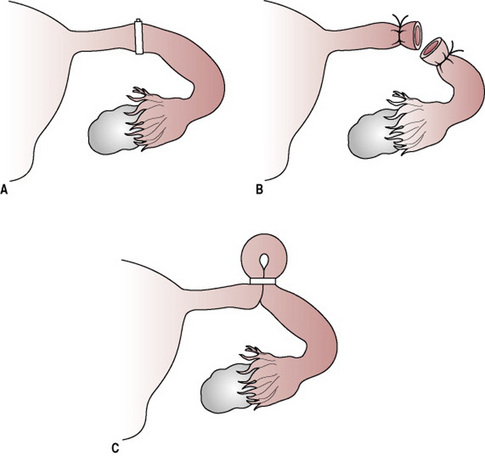

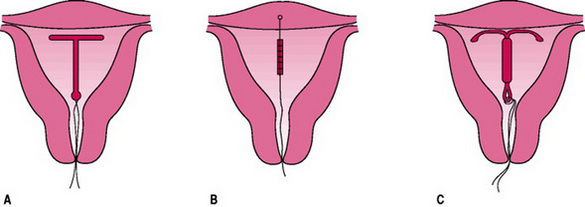

These devices are inserted into the uterus, as illustrated in Figure 37.4. They contain copper, which increases contraceptive efficacy. There seems to be an aversion for the use of IUCDs in the UK where only 3% of women use them (Guillebaud 2004). Some myths surrounding the old generation IUCDs perpetuated concerns about efficacy and safety. Service providers need to address these to allay women’s fears.

Figure 37.4 Intrauterine contraceptive devices. After insertion through the cervix, the framed devices assume the shape shown; the threads attached to it protrude into the vagina. (A) Copper-carrying device. (B) Frameless copper device. (C) Levonorgestrel-releasing system.

The IUCD is the most popular method in some countries and 156 million women use IUCDs worldwide, of which 60 million are in China.

Mode of action

The IUCD creates an inflammatory response in the endometrium. Leucocytes are capable of destroying spermatozoa and ova. Gamete viability is also impaired by alteration of uterine and tubal fluids. Copper affects endometrial enzymes, glycogen metabolism and oestrogen uptake, thus rendering the endometrium hostile to implantation. Failure rate is 0.4/HWY.

Using the IUCD

A copper IUCD can be inserted up to 5 days following the earliest estimated date of ovulation – that is day 19 in a 28-day cycle. The woman may experience some discomfort during the procedure, which should be performed using aseptic techniques. Depending upon the type of IUCD used, it may be left in place from 5 to 10 years and longer in some instances; e.g. if a woman aged 40 years or over has an IUCD fitted, it may remain in place until 1 year after the menopause, if this occurs after the age of 50. Once in situ, the device requires no action of the user and it does not interfere with intercourse. Women are usually taught to feel the threads as reassurance that it remains in place. A follow up in 3–6 weeks is recommended to check for infection, translocation or expulsion. Subsequently, the woman needs a check up only if she has concerns. The traditional routine annual review is no longer recommended (NICE 2005).

Side-effects of using the IUCD include menorrhagia, dysmenorrhoea, bacteria vaginoses and colonization by Actinomycetes-like organisms. When the latter is reported in a routine cervical smear, the woman should be counselled about the options of either changing the IUCD or keeping it and being reviewed periodically to ensure there is no pelvic infection. Removal of the IUCD is easy and painless whenever desired and fertility promptly restored.

The suggestion that IUCDs promote pelvic inflammatory disease (PID) has been refuted; although there is evidence to suggest that asymptomatic sexually transmitted infection (STI) in the cervix may be introduced at the time of insertion of the device. Clinical risk assessment for STI is recommended (WHO 2002). Routine or selective screening for chlamydia and gonorrhoea prior to insertion may prevent pelvic infections, since prompt treatment and contact tracing will be offered. IUCDs are associated with a decreased risk of ectopic pregnancies because of their effectiveness. However, the ratio of ectopic to intrauterine pregnancies is greater among women using IUCDs as, in general, the device prevents more intrauterine pregnancies than ectopic pregnancies. Thus a woman who has an IUCD fitted should be advised to seek early medical advice, should she suspect that she is pregnant.

If uterine pregnancy occurs, there is an increased risk of spontaneous abortion; therefore gentle removal of the device is preferred, to prevent septic miscarriage and premature labour. If removal is not possible it is reassuring to know there is no evidence of teratogenicity.

A newer frameless device, GyneFix (Fig. 37.4B) comprising six copper sleeves crimped onto a polypropylene monofilament thread, is fitted with one end embedded into the fundal myometrium of the uterus. This is associated with lower expulsion rates and less dysmenorrhoea.

Progestogen-releasing intrauterine systems (IUS)

These were developed to overcome some of the problems associated with conventional IUCDs and heavy menstrual bleeding.

The device in current use consists of a small plastic T-shaped frame carrying a Silastic sleeve loaded with 52 mg of levonorgestrel. It is inserted into the uterus and the steroid hormone is released steadily at 20 μg/day. The hormone prevents endometrial proliferation, thickens the cervical mucus and may suppress ovulation in some cycles; the frame, by inducing a sterile inflammatory reaction may also contribute to the contraceptive effect. The system is fitted within the first 7 days of the menstrual period; the contraceptive effect is then immediate. It is licensed for 5 years of use. Failure rate is of 0.2/HWY. A new frameless device containing progestogen has already been developed (Fibroplant- LNG).

Specific considerations

Irregular vaginal bleeding is common initially, and then gradually ceases. The uterine bleeding associated with the IUS is lighter than the menstrual period experienced when using a copper IUCD, with possible amenorrhoea in the long run. The failure rates of both intrauterine methods compare favourably with female sterilization.

Postpartum considerations

The IUS and copper IUCD have no adverse effect on lactation. They can be inserted 4–6 weeks after normal birth and 6–8 weeks after caesarean section (Guillebaud 2004). Following miscarriage or induced abortion, immediate insertion is safe.

Barrier methods of contraception

Barrier methods of contraception prevent the sperm coming into contact with the oocyte. They include male and female condoms, caps and diaphragms. They can be used in conjunction with spermicidal preparations. Barrier methods also offer some protection against cervical cancer (Mindel & Estcourt 2000).

Some of the advantages of using condoms are that they are easily available at many outlets in the UK and using them does not require medical intervention. They offer some protection against sexually transmissible infections and can be used with another method of contraception. This is often called ‘double Dutch method’. One of the main disadvantages of using barrier methods of contraception is the possible interruption to intercourse, which may be off-putting for some couples.

It is good practice to ensure that anyone choosing a barrier method is aware of emergency contraception and how to access it, should it be required.

The male condom

Some 44 million couples worldwide use the male condom but with striking geographical differences. Japan accounts for more than one-quarter of all condom users in the world. By contrast, and despite the massive problem of HIV/AIDS, use of this method of contraception remains low in Africa, the Middle East and Latin America, which together account for an estimated 10% of worldwide use (Guillebaud 2004).

Guillebaud (2004) writes that recent studies show approximately 20% of all couples in the UK use condoms but this may be occasional use or in addition to other methods. There are many varieties of condoms on the market including latex, hypoallergenic and polyurethane. Polyurethane condoms are less sensitive to heat and humidity and not affected by oil-based lubricants (FPA 2005b).

Correct use of condoms is essential. Only condoms with a CE mark should be used and the expiry date should be checked. They should be stored away from extremes of heat, light and damp. Care should be taken when handling the condom to prevent it from tearing. The condom is rolled on to the erect penis before any genital contact is made, this is because it is possible for some sperm to be present in the pre-ejaculate (Guillebaud 2004). About 1 cm of air-free space must be left at the tip of the condom for the ejaculate, otherwise the condom may burst. Some condom designs incorporate a teat end for this purpose. The penis should be withdrawn very soon after ejaculation before it reduces in size and the condom becomes loose. The condom should be held in place during withdrawal of the erect penis so that it does not slip off. The condom should only be used once, and then disposed of in a waste bin. It will not flush down the toilet.

If extra lubrication is required, care must be taken to ensure that the lubrication chosen will not damage the condom. Oil-based lubricants can damage rubber condoms but not polyurethane types. Water-based lubricants are not known to cause damage and are therefore recommended.

The failure rate with condom use is dependent on experience and age of the user and can vary widely between 1 and 10/HWY.

Female condom

This consists of a polyurethane sheath that is inserted into the vagina. The closed inner end is anchored in place by a polyurethane ring, while the outer edge lies flat against the vulva. It is available free from contraception clinics and may be purchased from selected chemists. Great care has to be taken to ensure that the penis is inside the polyurethane sheath and not wrongly positioned between the condom and the vaginal wall.

The efficacy depends on age and experience of the user. The FPA (2005b) state that if it is used correctly it is 95% effective.

Diaphragm

This is a thin rubber dome with a metal circumference to help maintain its shape. It is available in a range of types and sizes and, in the UK, it is individually fitted at contraception clinics and some GP practices. Only approximately 1% of women use this method of contraception in the UK (Guillebaud 2004). It is not used widely in developing countries and Guillebaud (2004) believes this may be due to the fact that it requires medical fitting.

When in place, the rim of the diaphragm should lie closely against the vaginal walls and rest between the posterior fornix and the symphysis pubis. Before insertion, spermicide should be applied. After insertion, the woman has to check that her cervix is covered. In order to preserve spontaneity during intercourse, the diaphragm can be inserted every evening as a matter of routine (Fig. 37.5).

If intercourse occurs >3 hrs after insertion of the diaphragm, then additional spermicide is required. The diaphragm must be left in place for at least 6 h after the last intercourse. Once removed the diaphragm should be washed with a mild soap, dried and inspected for damage. A new diaphragm should be fitted annually or following a loss or gain in weight of >3 kg.

The failure rate depends on age and experience of use. The FPA (2004a) quote that it is between 92% and 96% effective if used according to instructions.

In order to feel confident in using this method, the woman must feel comfortable touching her genitalia and have the physical ability to do this. The woman will also need privacy and access to water to clean the diaphragm. Cultural beliefs may affect acceptability of this method (Jogee 2004). The rim of the diaphragm may put pressure on the urethra and bladder base and this could result in cystitis. This could be remedied by a change in size or type of diaphragm.

Postnatal considerations

Following the birth of her baby, the woman should not rely on her previous diaphragm. The size should be reassessed at the 6th postnatal week when the vagina and pelvic floor muscles will have regained some of their tone and any tissue injury sustained from the birth will have healed.

Cervical and vault caps

These cover only the cervix, adhering to it by suction. They are made of rubber and may look smaller in diameter than the diaphragm. They require fitting at a contraception clinic.

Spermicidal creams, aerosols, pessaries

These preparations kill sperm but, as they are not able to penetrate the cervical mucus, they are probably only active in the vagina. Guillebaud (2004) recommends spermicidal creams, aerosols and pessaries are not used without another form of contraception.

The creams or aerosols must be applied immediately before intercourse. Pessaries must be inserted 10 min before intercourse to allow time for them to dissolve. Allergies can occur and couples need to experiment to find the most suitable preparation. Some spermicides are available free from contraception clinics and on prescription or they can be purchased from pharmacies.

Although there is evidence of inactivation of STIs including HIV in vitro, Jeffries and Aitken (2000), suggest there is no conclusive evidence that any spermicide will prevent infection in vivo. Concern has been expressed about possible teratogenicity if spermicides are used around the time of conception but most studies are reassuring. Guillebaud (2004) states they do not have any detectible teratogenic effect in ordinary use.

Emergency contraception

Emergency contraception is required when contraception was not used before, or during intercourse, used incorrectly or when there is perceived to have been a failure in contraception used, e.g. a condom mishap such as breaking, tearing or coming off. There are two types of emergency contraception.

The emergency hormonal contraception (EHC) is a progestogen preparation with the brand name Levonelle. It is one pill containing 1.5 mg of levonorgestrel, which is available in many countries throughout the world. In the UK it is free from sexual health clinics, walk-in centres, some accident and emergency departments and GP practices. Many Primary Care Trusts provide EHC free of charge through selected pharmacies in an effort to reduce unwanted pregnancies. It can also be purchased over the counter from pharmacies.

The method works by delaying ovulation or preventing implantation of the fertilized oocyte, depending on the stage of ovulation. This method may be contraindicated if there has been more than one episode of unprotected intercourse during the cycle, as the earlier intercourse may already have resulted in a pregnancy. Very careful questioning by the practitioner needs to take place prior to supplying EHC to prevent an unfavourable outcome.

Nausea is uncommon with the progestogen based pill but an additional pill is required if the woman vomits within 3 hrs of taking the medication. The next period may begin earlier or later than expected and the need to use contraception until the next period should be stressed. If the woman receives the EHC in a contraception clinic in the UK, she is always given an appointment to return to clinic if her period does not arrive on time, or is shorter or lighter than usual. If her period is over 7 days late, a pregnancy test will be offered. Any unusual lower abdominal pain must be investigated as this could be a sign of an ectopic pregnancy.

The failure rate of EHC depends how quickly the emergency contraception is used. If taken within 24 h of intercourse, it will prevent 95% of pregnancies. This gradually decreases to 58% by 72 hrs (FPA 2005c). There are very few contraindications to using this method but anyone administering Levonelle needs to know about any other medication being used by the woman. EHC can be used more than once in each menstrual cycle, but it may disrupt the period pattern.

The copper intrauterine device (IUCD) is the most effective method of emergency contraception, with a failure rate of <1%. Implantation of the fertilized oocyte is avoided if the IUCD is inserted within 5 days of the unprotected intercourse or earliest estimated date of ovulation. This gives the clinician a much longer time range in which to offer emergency contraception. For example in a regular 28-day cycle, the IUCD can be fitted up to day 19 of the cycle. It can then be left in place for use as a regular method of contraception, or removed during the next period.

Coitus interruptus, involves withdrawal of the penis from the vagina prior to ejaculation, and couples should be made aware of emergency contraception. Many euphemisms are used when referring to this, such as ‘being careful’ or the ‘withdrawal method’. Andrews (2006) gives a rate of 90% effectiveness as a contraceptive. Failure is due to the small amount of semen, which may leak from the penis, prior to ejaculation. Its success depends on the man exercising a great amount of self-control and the method is based on trust and honesty.

This method is used widely throughout the world by different cultures. It is the oldest form of contraception and is referred to in the old testament of the Bible.

Natural family planning

The study of natural family planning is a fascinating observation of the way in which the body works to produce the optimum conditions for conception.

According to UK Medical Eligibility Criteria for Contraceptive Use (FFPRHC 2006b), ‘Natural Family Planning’ includes all the methods of contraception based on the identification of the fertile time in the menstrual cycle. The effectiveness of these methods depends on accurately identifying the fertile time and modifying sexual behaviour. To avoid pregnancy, the couple can either abstain from intercourse or use a barrier method of contraception during the fertile time. Natural methods are attractive to couples that do not wish to use hormonal or mechanical methods of contraception. The success of natural family planning depends on adequate teaching by qualified fertility awareness teachers. Such instruction may be beyond the scope of many midwives but they should be able to provide basic information and appropriate leaflets from the FPA. The midwife can signpost the couple to the local contraception clinic or find local information on natural family planning teachers and available education from the website: www.fertilityuk.com

The method can also be used as a guide to women wishing to become pregnant, by concentrating sexual intercourse on the days they are most fertile. The fertile time lasts around 8–9 days each menstrual cycle. The oocyte lives for up to 24 hrs, the FPA (2005d) suggest that a second oocyte could, occasionally, be released within 24 hrs of the first and that a sperm can live inside a female body for around 7 days. This means that if sexual intercourse takes place 7 days before ovulation a pregnancy could occur.

Fertility awareness

Physiological signs of fertility are:

Cervical secretions

This method monitors the characteristic changes that occur in the cervical mucus throughout the menstrual cycle. Following menstruation there will be dryness at the vaginal entrance. As oestrogen levels rise, the fluid and nutrient content of the secretions increases to facilitate sperm motility. Following menstruation, a sticky white, creamy or opaque secretion is noticed. As ovulation approaches the secretions become wetter, more transparent and slippery with the appearance of raw egg white and capable of considerable stretching between the finger and thumb. The last day of the transparent slippery secretions is called the peak day. This day coincides closely with ovulation. Following ovulation, the hormone progesterone causes the secretions to thicken forming a plug of mucus in the cervical canal, acting as a barrier to sperm. The secretions will then appear sticky and dry until the next menstruation.

When practising this method of contraception, the cervical secretions are observed daily. The fertile time starts when secretions are first noticed following menstruation and ends on the third morning after the peak day. If the secretions are used as a single indicator of fertility, the presence of seminal fluid can make observation difficult. During the preovulatory, relatively infertile dry days it is recommended that intercourse takes place only on alternate dry evenings so that the mucus can be assessed. Intercourse should also be avoided during menstruation as this can mask the first appearance of cervical secretions. Changes in secretions will also be affected by spermicide, vaginal infections and some medications (Guillebaud 2004).

Postpartum considerations

In the first 6 months following the birth, the majority of women who are fully breastfeeding will be able to rely on lactational amenorrhoea (LAM) for contraception. Women who wish to continue using natural methods of contraception should begin observing cervical secretions for the last 2 weeks before the LAM criteria will no longer apply, in order to establish their basic infertile pattern.

Basal body temperature

A woman can calculate her ovulation by recording her temperature immediately on waking each day. If she has been up in the night she must have been resting for at least 3 hrs before recording her temperature. After ovulation, the hormone progesterone produced by the corpus luteum causes the temperature to rise by about 0.2°C and to remain at this higher level until the next menstruation. The infertile phase of the menstrual cycle will begin on the 3rd day after the temperature rise has been observed. Andrews (2006) points out that the temperature can be affected by infection. Therefore care needs to be taken when interpreting temperature charts.

Postpartum considerations

Day-to-day variation is greater at this time, because new mothers are likely to get up more during the night to take care of their baby’s needs. Therefore, taking an accurate temperature reading in the morning becomes harder. For this reason, many women prefer to rely on examining cervical secretions, or combine noting secretions with cervical changes at this time.

Cervical palpation

Changes in the cervix throughout the menstrual cycle can be detected by daily palpation by the woman or her partner. After menstruation the cervix is low, easy to reach, feels firm and dry and the os is closed. As ovulation approaches the cervix shortens and sits higher in the vagina, it softens and the os dilates slightly under the influence of oestrogen.

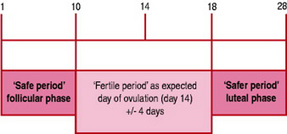

Calendar calculation (Fig. 37.6)

The calendar method is based on observation of the woman’s past menstrual cycles. When starting out using this method, the specialist practitioner and the woman will look at the previous six menstrual cycles (Andrews 2006). The shortest and longest cycles over the previous 6 months are used to identify the likely fertile time. The first fertile day is calculated by subtracting 21 days from the end of the shortest menstrual cycle. In a 28-day cycle, this would be day 7. The last fertile day is calculated by subtracting 11 days from the end of the longest menstrual cycle. In a 28-day cycle, this would be day 17. Cycle length is constantly reassessed and appropriate calculations made. Guillebaud (2004) indicates that the calendar method is not sufficiently reliable to be recommended as a single indicator of fertility, but is useful when combined with other indicators of fertility. Ovulation usually takes place 14 days before the first day of the next menstrual period. Therefore a woman who has a 28-day period would ovulate on approximately day 14 of her cycle and a woman who had a 30-day cycle would ovulate on approximately day 16 of her cycle.

Symptothermal method

This is a combination of temperature charting, observing cervical secretions, calendar calculation and optionally observing cervical palpation, to identify the fertile time. Andrews (2006) also includes in this method the observation of ovulation pain or ‘mittelschmerz’ and cyclic changes such as breast tenderness. Use of more than one indicator increases the accurate identification of the fertile time. When combining indicators, a couple should avoid intercourse from the first fertile day by calculation, or first change in the cervix until the 3rd day of elevated temperature, provided all elevated temperatures occur after the peak day.

Fertility monitoring device

There are a few different makes of devices on the market now which can be purchased at selected pharmacies. Prices range from £10.99 to £59.99 and they are not available on prescription. It is a hand-held computerized monitor which tests urine sticks. With careful and consistent, use it is between 93% and 97% effective in preventing pregnancy. The device monitors luteinizing hormone and oestrone-3-gluronide, a metabolite of oestradiol, through testing the urine. The ‘Persona’ monitoring device will detect from the urine test when a woman is fertile and indicate this through a series of lights. A green light indicates that she is in her infertile period and a red light indicates that she is in her fertile period therefore barrier methods must be used if she has sexual intercourse. A yellow light indicates that the database needs more information and a further urine test is required.

Postnatal considerations

The fertility monitor is not recommended as a method of contraception during lactation. The manufacturers recommend that a woman has had two normal menstruations with cycle lengths from 23 to 35 days before using the monitor at the beginning of the third period (Guillebaud 2004).

Lactational amenorrhoea method (LAM)

Before modern forms of contraception, lactation, with its inhibiting action on ovulation, was a major factor in ensuring adequate intervals between births. It is thought that the action of the infant suckling at the breast causes neural inputs to the hypothalamus. This results in the inhibition of gonadotrophin release from the anterior pituitary gland, leading to suppression of ovarian activity. The delay in return of postnatal fertility in lactating mothers varies greatly as it depends on patterns of breastfeeding, which are influenced by local culture and socioeconomic status. The time taken for the return of ovulation is directly related to sucking frequency and duration. The maintenance of night-feeds and the introduction of supplementary feeds also affects the return of ovulation.

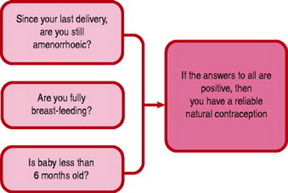

Bellfield et al (2006) describe breastfeeding as a very effective method of contraception when used according to the Bellagio Consensus statement. This concludes that there is a 98% protection against pregnancy during the first 6 months following birth if a mother is still amenorrhoeic and fully or almost fully breastfeeding her baby. The mother can be asked if these three rules still apply to confirm LAM remains effective (Fig. 37.7). Mothers who work outside the home can still be considered to be nearly fully breastfeeding, provided they stimulate their nipples by expressing breastmilk several times a day.

The LAM is not recommended for use after 6 months following birth, because of the increased likelihood of ovulation. A WHO (1999) multicentre study reported that in the first 6 months after childbirth the pregnancy rate ranged from 0.9% to 1.2% during full breastfeeding.

Male and female sterilization

This is the choice of contraception for many couples once their family is complete. Sterilization should be viewed as permanent, although in a few cases reversal of the operation is requested. Couples requesting sterilization need thorough counselling to ensure that they have considered all eventualities, including possible changes in family circumstances. Although consent of a partner is not necessary, joint counselling of both partners is desirable. The procedure is available on the NHS for both sexes but waiting times vary throughout Britain. There are no alterations to hormone production following sterilization in males or females and some couples find the freedom from fear of pregnancy very liberating.

Female sterilization

An estimated 210 million women worldwide have undergone female sterilization (Fig. 37.8) (Guillebaud 2004). During the procedure, the uterine tube is occluded using division and ligation, application of clips or rings, diathermy or laser treatment. Modern methods aim to achieve minimal tissue damage with the isthmus section of the uterine tube being chosen as the place to divide the tube as it is of static diameter and this would increase the chance of successful reversal.

The operation is performed under local or general anaesthetic. The procedure can be performed via a laparotomy, minilaparotomy or laparoscopy. It can also be performed vaginally using a hysteroscope. It usually requires a day in hospital.

The effect is immediate, although the woman using the contraceptive pill may be advised to continue to use contraception until the next menstrual period, to prevent ovulation taking place. This is because in the case of failure of the procedure, there may be an increased chance of ectopic pregnancy (Bellfield 2006). Because of this risk, the couple should be advised to seek medical help urgently if they suspect pregnancy following sterilization because of the increased risk of ectopic pregnancy. Following hysteroscopic sterilization (Essure), tubal blockage is confirmed by hysterosalpingography after 3 months.

Postpartum considerations

The woman may experience regret later. This highlights the need for thorough counselling prior to the procedure. FFPRHC (2006b) suggests waiting 6 weeks after the woman has given birth before carrying out the procedure. They also suggest that if sterilization is going to be carried out at the same time as an elective caesarean operation, then 1 week or more should be given for counselling and decision-making before the procedure takes place. Guillebaud (2004) suggests that a waiting period of 12 weeks is desirable to ensure that the couple will have no regrets over the sterilization.

The failure rate for female sterilization is 1 in 200 (FPA 2004b). Reversal of the sterilization is not usually available on the NHS in the UK and can be difficult and expensive to obtain privately.

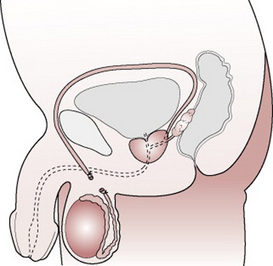

Male sterilization (vasectomy) (Fig. 37.9)

This procedure involves excision or removal of part of the vas deferens, which is the tube that carries sperm from the testes to the penis. There is a small cut or puncture to the skin of the scrotum. It is easier to access the vas deferens at this point. The tubes are cut and the ends closed by tying them or sealing them with diathermy. The wound on the scrotum will be very small and stitches are not usually required. In the UK, the operation is carried out in an outpatients department or clinic setting. It is usually completed under local anaesthetic and takes around 10–15 min. Men are advised to refrain from excessive physical activity for about 1 week and avoid heavy lifting (Andrews 2006).

It may take some time for sperm to be cleared from the vas deferens. Approximately 12 weeks after the operation, the semen must be tested to confirm that it no longer contains sperm and sometimes a second test is necessary to confirm the absence of sperm. Sexual intercourse can take place during this period but contraception must be used until a negative sperm result is confirmed.

The failure rate of male sterilization is 1 in 2000 (FPA 2004b). Careful counselling needs to take place before the procedure is carried out. Reversal of vasectomy is not usually available on the NHS. Even if the reversal is successful in achieving re-anastomosis of the vas, pregnancy may be difficult to achieve because of the development of anti-sperm antibodies in some men. Andrews (2006) quotes a 50% success rate in achieving a pregnancy following successful reversal.

The future of contraception and sexual health services

Development of sexual health and contraception services is now a top priority for the government, as discussed in The National Strategy for Sexual Health and HIV (DH 2002). Primary Care Trusts are now being required to address local priorities in contraception and sexual health, e.g. offering an appointment within 48 hrs at a genito-urinary clinic; prompt referral to abortion services and lowering the teenage pregnancy rate.

In response to the Social Exclusion Unit Report (DH 1999), many PCTs now provide clinics and projects for young people. One of the specific targets of this report was to reduce the teenage pregnancy rate by 50% by 2010. With the development of the Fraser guidelines (Royal College of General Practitioners 2000), it is now possible to give contraceptive advice to young people under 16 years old, provided parental involvement is encouraged and the young person understands the nature of the consequences of treatment. The practitioner should also be of the opinion that, if contraception were withheld, sexual intercourse would still be likely to occur and the young person’s physical and mental health could be compromised.

The NICE guidelines (2005) has emphasized the need to promote long-acting reversible contraception. This requirement will encourage more people to use a form of contraception which does not have to be remembered on a daily basis.

There is a trend in the UK for many women to have their children later in life and to have much smaller families. Throughout the world, people will seek to find new ways to limit their family size as the need to reduce population growth continues (Guillebaud 2004).

Future developments

An extended regimen of combined contraceptive pills for 84 days (e.g. Seasonale) has been confirmed to be safe (Edelman et al 2006) and is presently licensed in many countries. Alternative delivery systems reducing the need for daily pill taking are being explored. Vaginal rings, implants and metered dose transdermal systems (MDTS), frameless intrauterine systems, subcutaneous injections (depo-subQ) and chewable tablets are being developed for progestogens. Research into biodegradable implants (Andrews 2006) and the use of transdermal spray for the delivery of a potent progestogen is ongoing. The Population Council is considering research into proteomics and an immunological approach to contraception (Nass & Strauss 2004). Effective methods for men are still problematic; however long-acting testosterone injections with implanted progestogens may be available in the future (Guillebaud 2004).

Andrews G, editor. Women’s sexual health, 3rd edn, Edinburgh: Elsevier, 2006.

Barrett G, Pendry E, Peacock J, et al. Women’s sexual health after childbirth. British Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology. 2000;107(2):186-195.

Bellfield T, Carter YH, Matthews P, et al. The handbook of sexual health in primary care. London: Family Planning Association, 2006.

Beral V, Kay C, Hannaford P, et al. Mortality associated with oral contraceptive use: 25 year follow up of a cohort of 46 000 women from the RCGP’s oral contraception study. British Medical Journal. 1999;318:96-100.

Collaborative Group on Hormonal Factors in Breast Cancer. Breast cancer and hormonal contraceptives: collaborative reanalysis of individual data on 53 297 women with breast cancer and 100 239 women without breast cancer from 54 epidemiological studies. Lancet. 1996;347:1713-1727.

Committee of Safety of Medicine. Combined oral contraceptives: venous thromboembolism. Current Problems in Pharmacovigilance. 2004;30:7.

Croxatto HB, Makarainen L. The pharmacodynamics and efficacy of Implanon. An overview of the data. Contraception. 1998;58(Suppl):91S-97S.

DH (Department of Health). Teenage pregnancy. Report by the Social Exclusion Unit. The Stationery Office, London, 1999.

DH (Department of Health). The National Strategy for Sexual Health and HIV. Implementation of action plan. DoH, London, 2002.

DH (Department of Health). Choosing health – making healthier choices easier. London: DH, 2004.

Dieben TO, Roumen FJ, Apter D. Efficacy, cycle control, and user acceptability of a novel combined contraceptive vaginal ring. Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2002;100(3):585-593.

Dunn N, Thorogood M, Faragher B, et al. Oral contraceptives and myocardial infarction: results of the MICA case control study. British Medical Journal. 1999;318:1579-1584.

Edelman A, Gallo MF, Nichols MD, et al. Continuous versus cyclical use of combined oral contraceptive pills: Systematic Cochrane review of randomised control trials. Human Reproduction. 2006;21(3):573-578.

FPA (Family Planning Association). Leaflet: Your guide to diaphragms and caps, 2004.

FPA (Family Planning Association). Leaflet: Your guide to male and female sterilization, 2004.

FPA (Family Planning Association). Leaflet: Your guide to the contraceptive patch, 2005.

FPA (Family Planning Association). Leaflet: Your guide to male and female condoms, 2005.

FPA (Family Planning Association). Leaflet: Your guide to emergency contraception, 2005.

FPA (Family Planning Association). Leaflet: Your guide to natural family planning, 2005.

FFPRHC (Faculty of Family Planning and Reproductive Health Care) Clinical Effectiveness Unit. First prescription of combined oral contraception. London: FFPRHC, RCOG, 2006. (updated 2007)

FFPRHC (Faculty of Family Planning and Reproductive Health Care) Clinical Effectiveness Unit. UK medical eligibility criteria for contraceptive use, 3rd edn. FFPRHC, RCOG, London, 2006.

Guillebaud J. Contraception: your questions answered, 4th edn. Churchill Livingstone, Edinburgh, 2004.

International Agency for Research on Cancer (IntARC). Combined oestrogen-progestogen contraceptives. Monographs on the evaluation of carcinogenic risks to humans No. 91, 2005.

Jeffries D, Aitken R. Spermicides and virucides. In: Mindel A, editor. Condoms. London: BMJ Books, 2000.

Jogee M. Religions and cultures, 6th edn. Edinburgh: R & C Publications, 2004.

Kemmeren J, Algra A, Grobbee D. Third generation oral contraceptives and risk of venous thrombosis: a meta-analysis. British Medical Journal. 2001;323:131-139.

Kubba AA. Combined oral contraceptive choice: understanding the differences. Medicine Matters in General Practice. (Issue 101):2005.

Marchbanks PA, McDonald JA, Wilson HG, et al. Oral contraceptives and risk of breast cancer. New England Journal of Medicine. 2002;346:2025-2032.

Mindel A, Estcourt C. Condoms for the prevention of sexually transmitted infections. In: Mindel A, editor. Condoms. London: BMJ Books, 2000.

Nass S, Strauss J. New frontiers in contraception research: a blue print for action. Washington (DC): Institute of Medicine National Academy Press, 2004.

NICE (National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence). Clinical guideline 30. London: Department of Health, 2005.

Novak A, de la Logeb C, Abetzc L, et al. The combined contraceptive vaginal ring, NuvaRing: An international study of user acceptability. Contraception. 2003;67:187-194.

Nursing and Midwifery Council. Midwives rules and standards. London: Nursing & Midwifery Council, 2004.

Royal College of General Practitioners. Confidentiality and young people toolkit. London: Royal College of General Practitioners and Brook, 2000.

Royal College of Midwives. Midwifery practice in the postnatal period. London: Royal College of Midwives, 2000.

Scholes D, LaCroix AZ, Ichikawa LE, et al. Change in bone mineral density among adolescent women using and discontinuing depot medroxyprogesterone acetate contraception. Archives of Paediatric Adolescent Medicine. 2005;159:139-144.

Schwarz JL, Creinin MD, Pymar HC, et al. Predicting risk of ovulation in new start oral contraceptive users. Journal of the American College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists. 2002;99:177-182.

Serjeant GR. The long acting progestogen-only contraceptive injection: sickle cell disease. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1985;287-288.

Speroff L, Darney P. A clinical guide for contraception, 3rd edn. Philadelphia: Lippincott, 2001.

Szarewski A, Guillebaud J. Contraception: a users guide, 3rd edn. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2000.

Teegarden D, Proulx WR, Martin RR, Zhao J, et al. Peak bone mass in young women. Journal of Bone Mineral Research. 1995;10(5):711-715.

Vessey M, Lawless M, Yeates D, et al. Progestogen-only oral contraception. Findings in a large prospective study with special reference to effectiveness. British Journal of Family Planning. 1985;10:117-121.

WHO Reproductive Health and Research in Family and Community Health. Selected practice recommendations for contraceptive use. Geneva: WHO, 2002.

WHO (World Health Organization). Multicultural study of breast-feeding and lactational amenorrhoea method 111; pregnancy during breast-feeding. Fertility and Sterility. 1999;72(3):431-440.

Family Planning Association UKScotland: Tel: 0141 576 5088 Northern Ireland: Tel: 028 90 325 488 UK: 0845 310 1334 (open to 6 p.m.) www.fpa.org.uk All are open Monday to Friday from 9 a.m.–4.30 p.m.

Brook (putting young people first) UK: Tel: 0800 0185 023 www.brook.org.uk

Fertility UK www.fertilityuk.org

Faculty of Family Planning and Reproductive Health Care www.ffprhc.org.uk