Chapter 55 International midwifery

The chapter outlines the issues and agendas facing midwifery from an international perspective. Its focus is on the major events and global issues that have helped raise the profile of midwives and their profession.

In such a short chapter it is not possible to give an in-depth analysis of the global situation, nor describe in detail midwifery in every country. When reference is made to the situation in a named country, it is done so as an example to assist understanding and not to criticize the midwives working there. The aim of this chapter is to increase understanding of the midwifery context globally and foster a sense of unity and respect for a shared philosophy that underpins the profession, despite the different models of health or education systems in use throughout the world.

Introduction

Today, the effects of globalization, including advances in technology and use of the internet, as well as ease of travel, mean that the issues and problems of the world are finding their way into both the workplace and our homes. Health has to some extent always been considered a global issue, especially in relation to communicable diseases. However, renewed interest as a result of the increased commercialization of health as a commodity, is making many countries, such as the UK, invest in developing a specific global health strategy (see UK Dept of Health website at: http://www.dh.gov.uk). In addition, widening socioeconomic differentials, failures of the global market place, demographic shifts and ageing populations have contributed to workforce shortages, especially in the public sector and acutely so in the health sector. One of the strategies used to fill such shortages, especially by the richer OECD countries (organization for economic cooperation and development), has been to recruit health workers from other countries, often from countries that can ill afford to lose such a valuable resource. Finally, the last decade has uniquely seen unprecedented massive population shifts and displacements for economic or humanitarian reasons due to natural disasters or conflict and across Europe, due to opening of borders, especially between East and Western Europe. The rise in migration of peoples across nations is seen as one of the major issues currently facing health service planners in a number of countries, particularly low-income countries in Africa (Awases et al 2004, Mensah et al 2005, WHO 2006a).

Therefore, for all the above reasons it is likely that at some time in their working career all midwives will find themselves working in another country with different cultures, traditions and resources, or working alongside midwives from other countries, or providing services to women and families from other countries with vastly different cultures and traditions. As such, more than ever, midwives need to have an acute sense of the global village we live in and the issues facing midwifery globally. This chapter will first try to explore some of the issues as well as practicalities of working in another country, as well as working in an international setting. It will then try to outline some of the relevant international health agendas and initiatives that impact on midwifery. In one chapter it is not possible to cover all aspects of international midwifery in depth, but rather the main aim is to give some insights to the various issues with the aim of benefiting those who wish to explore this field of practice, as well as those who are just interested in what is happening in relation to midwifery globally.

The practicalities of working in another country

Before departure

One of the first practical issues to address for those wishing to work outside their own country is obtaining permission to work and ensuring that they have the correct visa. This can be difficult, as many countries have stringent regulations for issuing work visas and it may be necessary to produce an official letter of invitation from the employing agency or company. Without the correct documents and letter of invitation, it can be complicated to gain entry into the country and obtain permission to stay and work there; therefore it is always advisable to check the requirements carefully before departure. Most embassies or consulates will provide the necessary information and advice on the documentation needed to apply for a work visa.

Attention to health and personal safety is another essential practicality that must be taken care of before departure. In particular, it is essential to have adequate medical insurance cover. Where possible, always ensure insurance cover will allow an unscheduled return home to deal with personal difficulties, as trying to arrange this very quickly from another country can be traumatic. Many agencies or employers will be sympathetic and may include this as a benefit in the recruitment package or terms and conditions of the contract, if one exists. When responding to advertisements for a specific post, these details should be clarified before accepting the position. Critically it is vital to have up-to-date vaccination cover. Information on necessary immunizations, health precautions and so on is readily available from the WHO. Many countries also have a national travellers’ help-line or institution and professional association that will also be able to offer advice.

The issues that are frequently least easy to deal with are the actual feelings and psychological practicalities of working in another culture. Adaptation to working in a different country with different customs, beliefs and traditions can be difficult, even when anticipated. Midwives may find such feelings difficult to accept, as they conflict with their internal view of themselves as a capable, flexible practitioner. A great deal of illness however, can result from the stress of working in such conditions. The potential for such illness needs to be acknowledged by those going to other countries to work, as well as those recruiting staff from other countries. Therefore speaking to and if possible spending some time with someone who has worked in the same area can be very helpful and rewarding. One of the difficulties of preparing for such stress is that it is not easy to predict how well an individual will cope in a given situation at any specific time. The factors that help adaptation are different in every situation. Experience of working in different cultures and countries can help, but each situation is new and must be seen as such.

Increasingly, organizations are providing courses or workshops for health workers who would like to consider this work, to help explore some of these issues before making a definite decision. The International Health Exchange in the UK and the International Red Cross are two such organizations and they provide excellent courses for those intending to work internationally and those wishing to consider it. Information on such courses is often available in quality primary or international healthcare journals. Also there is an increase in the number of university programmes that include elective periods where a short time can be spent in another country undertaking a small project or work experience. Finally The Royal College of Midwives (RCM), the Royal College of Nursing (RCN) and the British Medical Association all have printed materials to help health practitioners who wish to work overseas.

One factor that can influence adaptation to working in another country is the careful consideration of the motives for doing so. As with all career choices, there are varied and complex reasons why someone would choose this particular path. There is no one valid reason for embarking on such a career move, only an issue of individual choice. However in doing so, midwives must apply a certain level of objectivity to ensure the right choice is being made about the suitability, type, as well as place of work that is appropriate for them. It is all too easy to become quickly disillusioned with the new environment if the main motive for seeking this type of work was travel, but the project or place chosen makes travel difficult or impossible.

Clarification of motives is also helpful when faced with unfamiliar, frustrating or difficult situations. Working in another country in a culture that is unfamiliar, is very different from visiting on holiday or for pleasure or interest. However, such work does have its rewards. It can help to develop a wider view of midwifery, motherhood and health. It offers the opportunity for reflection and seeing one’s own practice through different eyes. Most midwives who have done such work feel that it allows them to develop greater flexibility, innovation and self-confidence. Of course, much will depend upon the type of work undertaken, but the advantages and the friendships that develop while undertaking such work often outweigh the difficulties.

Working in a different culture

The requirement to provide culturally sensitive care is embodied in the International code of ethics for midwives (ICM 1999). The main issue facing midwives from another country developing culturally sensitive care is often around difficulties with language and being unable to listen to women’s voices; often transmitted through traditional songs and folklore. Also, in some countries, particularly in Asia, beliefs and taboos surrounding pregnancy and birth can make listening to women’s stories particularly difficult, as they are usually not spoken about directly, for fear of evoking bad spirits or bringing bad luck. Just to acknowledge the pregnancy might be viewed as dangerous. This raises obstacles to both provider and recipients of midwifery care. For example, encouragement of antenatal care, promotion of health in pregnancy, or even advice on planned pregnancies is problematic in a culture where to do so is seen as culturally unacceptable.

One way to overcome such cultural barriers is to work with the local community, especially women’s groups and community or religious leaders. Where such leaders are usually men however, this can raise other gender-laden issues. Gender training or gender sensitivity courses may help the midwife to find a way to work with or through male leaders in a way that will empower women, although it is always essential to first identify, together with the women, what strategies women currently use for dealing with such issues. Assisting the male leaders and the community to consider general household practices and beliefs, and the effects that these may have on childbearing women, is possible, and where this approach has been used it has had positive results (Mullay 2006).

When working on empowerment issues it is important to remember that notions of empowerment are also culturally bound (Portela & Santarelli 2003). Women from different cultures have different ideas about what they see as empowerment (Chitnis 1988, Collins 1994, Dawit & Busia 1995). Given the opportunity however, women from all cultures have clear ideas about what they think would assist them to give birth in a way that is safe and yet culturally sensitive.

Use of appropriate technology

In addition to adopting the right approach to providing such care, midwives also need to concern themselves with the appropriate use of technology. Careful consideration is necessary when taking new technology from one country to another. For example, in many industrialized settings it is no longer considered essential to give iron supplementation routinely to well-nourished pregnant women. In under-resourced countries however, haemorrhage before, during and after birth remains the major cause of death owing to poor nutrition and social deprivation (WHO 2005a). In these situations, faced with high maternal mortality and high levels of under nutrition, it is clearly appropriate to have a protocol that promotes routine iron supplementation to all pregnant women.

Importing systems, technologies and tools without ensuring they get appropriately adapted can adversely affect the quality of care. Although in themselves the tools may be good, if they are not adapted to meet the cultural complexity of the country, they may be ineffective, or used in an inappropriate way. For example, there is almost universal acceptance that the partograph is a useful and effective tool, yet in some countries or cultures the counting of time is not in units of minutes or hours, and even the idea of charting events on a graph can be very difficult. Midwives working in an international arena therefore, need to ensure that the technology they take with them is appropriate and that correct training and systems are provided for its effective implementation and use.

The role of the consultant midwife

Beware the ‘expert’

Although the above practicalities of working in a different country are of concern for all midwives, it is particularly problematic for those working as international midwifery consultants or expatriate project workers, trainers or managers. The temptation to allow oneself to be seen as the ‘expert’, the one who knows all, is sometimes difficult to avoid. In the eyes of the new community, women and local midwives, there is a serious risk of being perceived as the expert who knows all. Such views can leave the midwife seen as an outsider, precluded from being accepted into the local community and therefore denied access to their knowledge and cultural systems.

The issue of being viewed as an outside expert is particularly problematic when working in countries that do not have recent experience of personal autonomy or personal responsibility. In countries that have a particular political tradition of being controlled from the centre, women may feel more comfortable seeing the consultant midwife as an ‘expert’, dictating the actual activities of care to be provided. Those not familiar with democracy or participation in decision-making may feel slightly afraid or unsure when introduced to participatory approaches. Therefore locals may initially resist or misinterpret requests for their views and opinions, or may not respond to opportunities to share their ideas with the newcomer.

Equally, for the consultant faced with enthusiastic individuals eager for change, tight work schedules, needs that often far outweigh resources or expectations that they will be the one to sort out the problems, can be daunting. In such situations it can be difficult to hold firm to principles of facilitation and participatory approaches to decision-making. In these situations, advocacy can easily stray into paternalism (or maternalism) and then only the voice of the ‘expert’ midwife is heard. The midwife’s role is always to encourage women to find their own voice and as far as possible ensure that it is the local women’s voice that is being heard; for the international consultant this includes the voices of the local midwives. The key skills for the consultant midwife are listening, supporting and participating in the daily lives and tasks of those they work with, be they receivers of care, or working colleagues.

Finally, the role of the consultant midwife can be lonely; therefore anyone taking on this role should ensure that they have a good personal support system from family, friends or long-standing colleagues (preferably ones with similar experiences).

International issues

International Confederation of Midwives (ICM)

One of the main actors in the global arena working to improve maternity services by empowering of midwives, especially through strengthening professional associations and promoting good practice, is the International Confederation of Midwives (ICM). ICM, a non-governmental organization (NGO), was started by midwives in Belgium in 1919 as the International Midwives’ Union. The purpose of the union was to ‘improve the services available to childbearing women through campaigning for a stronger, better educated and properly regulated midwifery profession’ (ICM 1994, p 1).

In the early 1960s ICM gained accreditation by the United Nations (UN) as a NGO in official relations, which means it can be part of official UN consultations. ICM works closely with UN organizations especially World Health Organization (WHO) and United Nations Population Fund (UNFPA) as well as with United Nations Fund for Children (UNICEF). ICM now has more than 85 member associations that cover approximately 72 countries. ICM Council admits new members on demonstration they meet the criteria for membership and payment of a membership fee, calculated against the number of midwives in the association and taking into account the economic situation of the country.

ICM has a small but friendly office that relocated from the UK to the Netherlands in 1999. The office welcomes both visitors and enquiries from midwives and midwifery organizations from anywhere in the world. Information on the history of the ICM, along with other information and leaflets, is obtainable from ICM HQ (see Useful addresses). The ICM also produces a regular newsletter free to its member associations, but is available to individuals on payment of a modest subscription.

ICM accomplishments

In recent years, the ICM has been proactive in a variety of global initiatives. By working collaboratively with other agencies, ICM has contributed to the increasing acceptance of the midwife as the key provider of quality maternity care. Working with WHO and the International Federation of Gynaecologists and Obstetricians (FIGO) ICM developed the International definition of the midwife. Having been first devised in 1966 and later revised in 1992, the latest revision was adopted by ICM Council in Brisbane during the 2005 Triennial Congress.

Most recently, ICM has been a significant actor in the establishment of the global Partnership for Maternal, Newborn and Child Health (PMNCH) the secretariat of which is housed in WHO HQ Geneva. PMNCH is the successor to the Inter-Agency Group on Safe Motherhood (IAGSM) established at the beginning of the Safe Motherhood Initiative in 1987. PMNCH aim is to bring together all constituent groups working on safe motherhood, newborn and child health. For more information on the work of PMNCH, see their website at: http://www.who.int/pmnch. In addition, ICM is working with both WHO, the United Nations’ Population Fund (UNFPA) and other partners such as The White Ribbon Alliance, to increase global, regional and national advocacy for investing in midwives and midwifery. The focus of the work is to accelerate progress to reach the Millennium Development Goals (MDG), in particular for improving maternal health (MDG Goal 5), as well as contributing to improving child health (MDG-4) and increasing gender equity (MDG-3). Information on and progress reports on achieving the MDGs can be found on many of the UN websites.

In addition to the development of the International Code of Ethics for Midwives (ICM 1999), other ICM achievements include instituting and coordinating of the International Day of The Midwife (annually on 5 May). Each country and midwifery organization may choose to devise the programme for celebrating this day. However, ICM Board draws up the major theme each year, with the intention to assist midwives and midwifery associations unite under a central banner to promote the role and responsibilities of the midwife.

By far, one of the most rewarding accomplishments of ICM, is the bringing together of groups of midwives from different countries for workshops, seminars and the triennial congress. The meetings, particularly the triennial congresses, are valuable not only for allowing midwives internationally to meet, debate and network, but also have been a useful vehicle for promoting midwives and midwifery in the host country. For example, the opening ceremony of the triennial congress is usually attended by high-ranking political officials of the host country and remains a favourite and often moving spectacle for all who attend.

Immediately prior to the congress, ICM often hosts a workshop, usually for 3 days on a theme related to safe motherhood; these too have been extremely beneficial for those attending and for raising certain issues related to midwifery in the international arena. A report of these workshops, which usually include useful background papers or information and material for the midwives attending the workshops, is always published. The action orientation of these workshops has allowed midwives from a variety of countries to develop plans and activities for improving the midwifery services to women nationally and globally.

The global Safe Motherhood Initiative

The global Safe Motherhood Initiative (SMI) was officially launched in Nairobi in February 1987. WHO, UNICEF and the World Bank as well as many NGOs, associations and multi- and bilateral aid agencies and ICM, have supported the global programme from the beginning. The impetus for this initiative was the outrage that many maternal deaths are preventable and that MCH programmes, at that time, focused mainly on the child and ignored the health and well-being of the pregnant woman. The slogan used in the early days being: ‘where is the M in MCH?’

The aim of SMI was to achieve a reduction of 50% in the global number of maternal deaths by 2000. Initially, SMI advocates envisaged that the goals of SMI would be achieved through empowerment of women. This point was further strengthened following the International Conference on Population and Development in Beijing and the UN Conference on Women Platform of Action, Cairo 1995, both of which called for the rights of women to be further strengthened and respected. Since 1987, various strategies have been employed to achieve the goal of safe motherhood and more attention has been given to the right to health and adoption of a rights based approach to health policy (Cook & Dickens 2001). Consequently there was an increase in strategies that focused on improving the sociopolitical and legal status of women, increasing their access to wealth and ending gender discrimination, especially in education and access to healthcare. However, the target set for 2000 was not achieved.

In 1997, to mark the tenth anniversary of SMI a technical review was held in Colombo, Sri Lanka to consider and document lessons learned (Starrs, IAGSM 2000). At this review a number a key messages were agreed – as a call for action. One of the major key messages was a call for ensuring all women have access to a ‘skilled attendant’ at birth (WHO UNFPA UNICEF World Bank 1999). A skilled attendant is a professional health provider with midwifery skills (Box 55.1) (WHO 2004a); to most people this is a professional midwife, someone who has the competency for provision of normal care, is able to manage or initiate first-line care for emergencies and is linked to a facility where specialist obstetric and neonatal care is available for management of complications and cases that fall outside the midwife’s scope of practice.

Box 55.1 Definition of a skilled attendant

(From: WHO 2004a Making pregnancy safer: the critical role of a skilled attendant. A joint statement by WHO, ICM FIGO.)

A revised version (from the original that appeared in the 1999 statement on maternal mortality reduction by WHO, UNFPA, UNICEF, and the World Bank) was developed in 2004 by WHO ICM and FIGO to clarify that all skilled birth attendants must be able to provide life saving skills and offer pregnancy and postnatal, including newborn, care. It stated that:

A skilled attendant is an accredited health professional – such as midwives, doctor or nurse – who has been educated and trained to proficiency in the skills needed to manage normal (uncomplicated) pregnancies, childbirth and the immediate postnatal period, and in the identification, management and referral of complications in women and newborns.

(This definition has been endorsed by UNFPA, The World Bank and ICN 2004.)

The call for ‘skilled attendants’ for all women came about as a result of perceived failure to reduce maternal deaths by employing a ‘risk approach’ to antenatal screening, whereby pregnant women identified as having risk factors were provided with specialist obstetric care. Criticism of the risk approach strategy for reducing maternal mortality focused around the lack of specificity, sensitivity and predictability of the risk factors used. Even though it is known that some women with certain histories and medical conditions have a potentially higher risk than others for developing a pregnancy-related complication, research shows that a significant proportion of life-threatening problems occur in women identified as being at low risk when using most of the risk-scoring systems. The failure of the risk approach and risk scoring to directly reduce maternal deaths does not mean that antenatal care does not play a significant role in maternal healthcare and identification of problems. Indeed much research has been undertaken that shows the effectiveness of a more focused approach to antenatal care.

Current SMI strategies: skilled care for all pregnant women

Based on the lessons learnt at Colombo and supported by historical evidence around maternal mortality reduction, the prevailing consensus of the maternal and newborn health community is that safe motherhood can only be achieved if all pregnant women have access to a continuum of care throughout pregnancy, childbirth and the postnatal period; in particular have access to a skilled attendant and emergency obstetric care, especially at and around the time of childbirth. (Campbell & Graham 2006, De Brouwere & Van Lerberghe 2003, Koblinsky 2003, Koblinsky et al 2006, Loudon 2000, WB 2005, WHO 2005a). The same is true when considering reductions in perinatal mortality and morbidity. The WHO considers almost a half of all perinatal deaths could be avoided if all newborns were assisted at birth by a skilled birth attendant (WHO 2006b). As testimony to the commitment to women and recognizing their importance in development and health, the compact agreed by 189 Heads of States towards poverty alleviation resulted in the MDGs. Included as one of the targets to be achieved by 2015, requires governments to increase access for all women to skilled care, especially at the time of birth, by including a target of 95% of all births to be attended by a skilled attendant, of which the figure of 85% was set for developing countries (see the MDG website: http://www.un.org/millenniumgoals).

The evidence shows however that the skilled attendant alone is not sufficient and, that minimally skilled attendants must work in an enabling environment where systems are in place to allow the practitioner to provide skilled care. These systems include among others, a regular safe supply of drugs and equipment, as well as supportive supervision and close links for easy referral to a facility able to offer higher level medical obstetric and neonatal services (Graham et al 2001). Recent estimates however suggest that in 2006 only between 40% and 60% of all pregnant women globally had access to a skilled attendant at birth (Stanton et al 2007).

Although the initial focus of SMI was only maternal mortality, in recent years this focus has shifted slightly and is now on the broader women’s health and reproductive health for all, especially adolescents. Also, using a human rights lens, there is also concern for morbidity. Studies in India and Bangladesh give morbidity rates as high as 15–16 times that of mortality rates (Goodburn 1995, WHO 2005a). A great deal of the morbidity was found to be due to unsafe and unhygienic practices based on superstitions and taboos, such as putting mustard oil into the vagina to try to hasten cervical dilatation and ensure a speedy exit through the birth canal, or use of excessive fundal pressure to deliver the placenta, in the belief that it is the placenta that harbours or attracts the evil spirits. Access to sexual and reproductive health services has now been added to the indicators for monitoring MDG-5.

At the twentieth anniversary of SMI, the number of maternal deaths worldwide remains similar to when it began in 1987, although analysis of data on maternal mortality, using 2005 data, shows there has been a slight reduction of MMR at the global level of 1% per annum since the late 1980s, however this is far below the 5.5% annual reduction needed to achieve the MDGs (WHO 2007).

Major global actions under the Safe Motherhood banner

Other global events significant to Safe Motherhood

One other important initiative, which has undoubtedly helped focus global attention on the continuing need to develop safe motherhood programmes, has been the WHO, UNICEF and UNFPA partnership around monitoring Maternal Mortality Ratios (MMR) across the globe and developing a new way to estimate MMR (WHO 1996b, 2001a). The revised estimates for 1990 for example demonstrated unequivocally that the figures for maternal mortality had been drastically underestimated, with some 8000 more deaths than was initially thought. Subsequent estimates of MMR demonstrate that the anticipated decline in maternal mortality set at the beginning of the Safe Motherhood Initiative has not occurred. In some countries there had been either a levelling off, or even a rise in MMR (WHO 2005a, WHO 2007). A recent systematic review of national reports show that variability of national maternal mortality estimates remain large across regions and within sub-regions (Gülmezoglu et al 2004). This is, or at least should be of concern to all involved in safe motherhood. It underlines the fact that there is no room for complacency in the attempts to make motherhood safer, if not completely safe. Therefore, efforts to recruit, train and deploy health personnel with midwifery skills is an urgent, continuing and priority need, especially in countries with high levels of maternal mortality.

Safe motherhood means more than surviving pregnancy and childbirth

The Safe Motherhood community is not just concerned with maternal mortality. Recently more attention has been given to morbidity and to the newborn health, although some would say not yet adequately. Increasingly, newborn health and reduction of perinatal mortality and morbidity is being highlighted in national maternal and child health and/or Safe Motherhood plans. Safe Motherhood advocates are also highly concerned with adolescent health and maternal morbidity, including access to family planning and safe abortion care. In addition to the estimated 530 000 women who die each year from complications of pregnancy and childbirth, with over 90% occurring in South-Asia and sub-Saharan Africa, there are in the region of 10–20 million each year who suffer severe morbidity following childbirth, of which obstetric fistula is probably the most debilitating and devastating. To highlight this, UNFPA in 2002 with WHO and others partners, launched a global advocacy programme on obstetric fistula (Donney & Weil 2004).

To summarize, safe motherhood is not just about ensuring that women do not die in childbirth. It is also about empowering women to take control over their own bodies to enable them to achieve optimum health. This must include being empowered to make effective and informed choices about if and when they will embark upon pregnancy. If they choose to become pregnant, then they should have access to all services, education and support (including community support) needed to achieve a healthy outcome; this may include access to safe abortion in countries where abortion is not against the law. It also includes the need for women, families and society to be assured that the newborn can reach healthy adult maturity; without this the pressures on women to conceive many babies will not be reduced and family planning strategies will be impeded. Above all it requires empowerment of women to demand services and to demand quality. Midwives as women (for the vast majority are usually women in many countries), also need to be empowered, both as women and as healthcare providers. They too need to be able to demand better services, better training, improved supportive supervision and support. Moreover they need and must be able to demand, better human resource policies – to ensure they can not only function effectively and provide quality midwifery care where and when women need it, but so they are able to earn a basic living wage and receive appropriate remuneration for their work.

The strategies required to achieve all of the above will vary from country to country. In most countries this will require addressing the sociological perspectives of women’s health, as well as the management and provision of effective health services. As Thompson & Bennett (1996) outline in their ICM pre-congress paper, ‘the provision and access to healthcare has only a small effect on the overall determinants for the health of women’. It would appear that by far the most important strategy for improving women’s health, are changes in the cultural practices, eliminating gender inequalities and improving the environment in which the woman lives – which include elimination of poverty and improved nutrition. This inevitably means that, in addition to developing appropriate technical midwifery skills, midwives must also involve themselves in political action to address these issues, as increasingly it is acknowledged that they have a direct effect on improving women’s health (Gill et al 2007).

The role of the midwife in Safe Motherhood

Much has been written and discussed in the various symposia, conferences, events, books and articles on the contribution midwives can make to the Safe Motherhood Initiative and safe motherhood programmes. However, what all midwives must remember is that safe(r) motherhood, in its broadest and narrowest sense, is still not an option for many thousands of women across the world (WHO 2005a). Although women in highly industrialized countries are subject to a different lack of control over their own bodies from women in developing or transitional market economy countries, both are frequently denied their rights related to pregnancy and childbirth. They are denied the right to choose and denied their right to exercise control over their own birth processes. Some Western countries however are making progress in this field, in particular New Zealand along with The Netherlands and the UK are in the forefront of ensuring that women have the right to choose what type of assistance they want during pregnancy and childbirth and where and when they want it. Yet other countries are seeing an acute rise in medicalization and medical dominance over pregnancy and childbirth care.

It is clear there is urgent need for strengthening the evidence-base for many safe motherhood interventions in low-income and resource-poor countries and in some countries for more effective scale up of midwifery (Miller et al 2003). For this reason, midwives must become more pro-active and learn to relate to, work with and seek to influence the leaders and major decision makers, both at the local and at the national level. They must also work more collaboratively with other professions, specifically their obstetric colleagues, to advocate for increased commitment to ensure skilled care for all women and newborns regardless of where they live, or of their socioeconomic situation.

Global Initiatives including Breastfeeding and Baby Friendly Hospital Initiative (BFHI), Saving Newborns Lives (SNBL)

Baby Friendly Hospital Initiative (BFHI)

Since the launch of the Safe Motherhood Initiative, there has been a number of related global activities of which the Baby Friendly Hospital Initiative (BFHI), driven by UNICEF and WHO is now considered to be one of the most effective mechanisms for creating strong political commitment to breastfeeding. The BFHI was launched in 1991 following the joint WHO/UNICEF statement on breastfeeding made in 1989, which outlined the ‘ten steps to successful breastfeeding’ (WHO, UNICEF 1989). The ‘ten steps’ have become the management tool and criteria for awarding BFHI status. According to recently published materials from WHO the BFHI has been implemented in 152 countries (WHO, UNICEF 2006). A training package for hospitals that wish to work towards the award of the status ‘baby friendly hospital’ can be downloaded from: http://www.who.int/nutrition/topics/bfhi

Unfortunately, despite the reported success of BFHI, global indicators demonstrate that the decline of breastfeeding, which began in the 1950s, and the trend towards bottle-feeding continues to date in many countries, including low-resource countries. This is despite of the research supporting the promotion of exclusive breastfeeding in the first 4–6 months, particularly for the control of diarrhoeal disease and upper respiratory tract infections. Understandably, the HIV pandemic and the findings that the virus can be found in breastmilk has given rise to concerns and debate regarding recommendations for replacement feeding in high HIV areas. The most recent WHO guidelines however, suggest that the risk of HIV transmission must be weighed against the risk of bottle-feeding in many low-resource countries (WHO 2001b) and others support this view (Latham & Prebble 2000). The WHO also suggest that mothers who are HIV-seropositive and where replacement feeding is not optimal and therefore choose to breastfeed, should continue to do so exclusively for the first few months. They should then, over a period of days and weeks (rather than abrupt cessation), change to replacement feeding, providing the conditions for safe replacement feeding are in place (WHO 2004b).

Difficulties to be overcome to achieve exclusive breastfeeding

Despite these global initiatives, the lack of exclusive breastfeeding for 4–6 months and the practice of discarding the colostrum remain the two major difficulties yet to be overcome in many countries. Very often, such practices, influenced by strong cultural superstitions and belief systems, cannot be overcome by simply presenting mothers with scientific evidence. Despite almost universal agreement that it is unacceptable and immoral to import and promote formula feed to countries where the water supply is not safe, violations of the code that governs marketing of formulae feeds continue, much as was highlighted by UNICEF more than a decade ago (UNICEF 1997b). Consequently, the International Baby Food Action Network (IBFAN) and others must continue to advocate for vigilance as well as identifying violations of the International Code of Marketing of Breastmilk Substitutes.

The newborn

In recent years, more attention has been given for the need to ensure that safe motherhood includes care for the newborn. Not only does each newborn, as a sovereign being, have the right to a safe start in life under the UN Convention on the Rights of the Child agreed in 1990, (UNICEF website: http://www.unief.org/crc), but governments have a responsibility to newborns. Moreover it is also recognized that attempt for parents to limit their fertility and avoid the cycle of rapid childbirths, which too often ends in maternal death, is undermined if the newborn does not survive. One of the leading advocates on newborn health has been Save the Children, who in 2000 launched a global Saving Newborns Lives (SNBL) initiative, which not only addresses policy issues, technical issues and advocacy, but also works with countries, as partners, to integrate better the issue of essential care of newborns (see: www.savethechildren.org/health/healthsavingnewbornlives).

International agenda

Midwifery identities

Listening to midwives at many and varied conferences and meetings worldwide, it would appear that the global concerns of midwives and the constraints they face have changed little since Kwast & Bentley published their paper in 1991 (Kwast & Bergström, 2001, Odberg-Pettersson et al 2007, Sherratt 2007). Their seminal paper, presented at the ICM pre-congress workshop in 1990, detailed the constraints and problems facing midwives worldwide, which include both the shortage and maldistribution of midwives, as well as the economic and training problems facing midwifery in many countries.

Midwives need specific policies and legislation to practise

One of the most common and urgent needs facing midwives in many countries is the need for specific (if not separate) policies and legislation to enable them to practise. This was highlighted most recently during the first International Forum on Midwifery in the Community organized by UNFPA, ICM and WHO in collaboration with partners. At this pivotal meeting, a Call to Action was made (Hammamet Call to Action) for increased investments in midwifery. Participants at this forum agreed, where separate policies and practices for midwifery are not identified, midwives can be hampered if they have to practise under nursing protocols and legislation, which too often do not cover the midwife’s right to practise essential life-saving skills for pregnancy, childbirth and newborn care.

Also of common concern, as expressed at this Forum, was the continuing issue that faces many midwives internationally, the lack of acceptance that they have a right to practise as autonomous practitioners. The manifestations of this issue will vary depending on the country concerned. For many, the domination of the medical profession will be the most difficult barrier to overcome. However, it is heartening to recall that, as far back as 1985, the WHO and some obstetricians recognized the pivotal role of the midwife in providing quality maternity care (Wagner 1994). Moreover, as evidenced by the increasing number of joint statements and joint action between the professional associations representing obstetricians and those for midwives, including at the international level, this mutual respect is growing and more is being translated into action. Nevertheless, too often the relationship between the two professions in some countries remains contentious and leads to the fragmentation of care and services for women and babies, as well as placing barriers for the delivery of broader public health interventions (de Bernis et al 2003).

It is true to say however, that the unique nature of midwifery practice, as separate and distinct from nursing, is still not universally accepted. In many countries in Africa and elsewhere, there are logical and rational reasons for having a multi-professional provider such as a nurse-midwife, where the provider has competencies of both professions. Moreover, ‘midwifery’ can appropriately be a qualification obtained after training as a nurse, especially where the nurse-midwife may be the only healthcare person available in a rural setting (Box 55.2). However, what is unequivocal, yet still needs highlighting, is that the two professions each have a distinctive, if overlapping, body of knowledge and practice. As such they both need valuing for their individual contribution to a nation’s health. It is also clear that legislation and structures must reflect these differences, as well as the similarities. Legislation must be drafted in such a way that it respects and assures each profession as to the right to practise. While legislation must be sensitive to the particular situation in a country, it must permit the midwife the responsibility to provide quality care – including care during labour and birth, as well as delivery of certain interventions necessary for saving life.

(Report of Tanzanian midwifery representative at WHO technical meeting on strengthening midwifery services to support Making Pregnancy Safer, November 2001.)

Many women in our country still live in rural areas, whereas most skilled attendants (midwives) work in urban areas. Therefore many births are still attended by TBAs (Traditional Birth Attendants) or family members. The reasons why midwives prefer working in urban areas include: lack of infrastructure, lack of incentives, high workload in rural areas where the midwife must do more than midwifery, poor safety and professional isolation. Not only is there a need to address these issues, there is also a need to strengthen the skills, knowledge and attitude among the skilled providers. Women are reported to have preference for TBAs’ services rather than skilled midwifery services because of the bad attitudes of those skilled attendants (midwives) and that, although trained, many woman feel the midwives still have insufficient and inadequate skills. There is also lack of updating of skills specifically for those few in the rural areas. Recently many actions including the White Ribbon Alliance in Tanzania is taking steps to redress this situation.

Another issue requiring urgent attention is ‘licence to practise’. Although licence to practise is an issue of safeguarding the public and therefore a matter for government concern and good stewardship and governance, mechanisms to support licensure are too often absent or weak. In many resource-poor countries there is a lack of professional standards, including competency-based standards for education and training, as well as the rigorous systems and mechanisms to ensure that such standards are not just set, but complied with. As such, the mechanisms used to ensure licence to practise, including re-registration and mandatory continuing professional updating are compromised. Good governance however, must not be confused with political interference or dominance in the determination of professional standards. It is the responsibility of governments to ensure that frameworks exist that will demonstrate that individual health practitioners have received appropriate education – but not necessarily their role to execute such systems – this being the prerogative of the profession.

Education of midwives

The education of midwives has been a matter of long-standing debate and concern in many countries, for a variety of reasons. While education and in-service training for midwives in some countries is weak, it must be remembered that education and training is only one element to ensuring that providers are competent; there must also be adequate and appropriate supportive supervision. Moreover, there must also be a functioning health system to support service providers and create an environment where midwives are able to carry out their function correctly, including ensuring their safety and proper remuneration and career pathways.

As previously stated, in some countries, the preparation of midwives may follow on from nursing. While there may be good reasons for this in some situations, there are also a number of disadvantages, particularly where nursing does not have a sufficiently strong public health basis. In some situations, the midwifery-following-nursing model can result in midwifery being seen as an adjunct to nursing. The consequence of this can be that midwifery is too often afforded very little time within the nursing curriculum, as happens in both resource-poor countries and highly industrialized ones.

Increasingly, because of the global shortage of human resources, as outlined in the World Health Report 2006 (WHO 2006a), many countries are or have turned to semi-skilled or multi-purpose workers to fill their human resources for health gaps, especially for provision of healthcare at the community level. Where multi-purpose providers exist, there can be role confusion, as well as overlaps or even gaps in continuity of care for pregnant women and their newborns. For example, sometimes community health workers, or multipurpose public health workers provide the prenatal services work completely separately from midwives who offer intranatal care. Often these multipurpose workers have minimal midwifery input into their curriculum. Some midwifery experts agree the move to increased use of multipurpose workers, coupled with incorporating midwifery into nursing curricula, has led to an ever-spiralling decrease in midwifery standards. The teaching of midwifery being weak, leads to practitioners who have limited midwifery competencies who eventually find themselves as teachers, ill-equipped for developing midwifery competencies in others. For Kwast and Bergström, midwifery, as a specialization, has in many low-income and resource-poor countries become reduced to maternal and child healthcare, or obstetric or maternity nursing (Kwast & Bergström 2001); many others would echo this. These multipurpose practitioners are often unable to perform the full range of midwifery competencies, in particular the essential life-saving skills. Given the short time the curriculum allows for developing midwifery competencies, coupled with the low case-loads because of low utilization of healthcare professionals and/or health facilities, it is little surprise that many of these multipurpose and community healthcare workers also lack confidence and are unable to perform midwifery skills outside of the hospital environment, or without supervision. This issue becomes even more problematic as less and less time is available for developing specific midwifery competencies due to increasing demands on their curricula for additional content related to HIV AIDS and other relatively new public health concerns, such as SARS and avian flu.

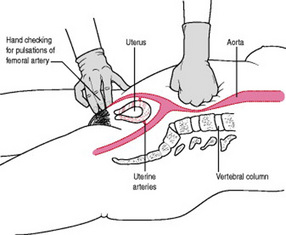

Everyone will agree training must be skills-based. However, many training programmes in the past have failed to take account of the fact that midwifery is essentially a practical profession, where practice is underpinned by evidence, scientific principles and knowledge coupled with sound practical application using critical thinking skills (Penny & Murray 2000). The skills required by the midwife may vary from country to country, depending on the specific needs of the country. However, ICM (2002) have now developed a list of international evidence-based core competencies – essential competencies (Fullerton & Thompson 2005). During the First International Forum on Community Midwifery, participants agreed that the ICM competencies should be used as the international benchmark for assessing midwifery competence (Odberg-Pettersson et al 2007). It must be remembered however that in some situations additional core competencies, that may not be seen as usual for midwives in the UK, are required as standard (essential) for all midwives in many resource-poor countries. For example, being able to undertake a manual removal of the placenta or being able to apply aortic compression competently as shown in Figure 55.1 and outlined in the WHO manual Managing Complications of Pregnancy and Childbirth (WHO 2000) may be the only way to save a woman’s life in some countries. Midwives from industrial countries therefore should be aware that, in some resource-poor settings, midwives may find themselves in a situation where knowledge and skills alone are all that are available to save the woman’s life. Training for these and other life-saving skills must therefore focus on achieving competence, which implies use of critical thinking skills, as well as sufficient opportunity for hands-on-practice. Very often in some countries, although the theoretical knowledge may be taught well in the initial pre-service programmes, there is too often little or no opportunity to practise the skills in the clinical situation. As a result, all too frequently, newly trained midwives find themselves lacking in confidence and competence in many of the core midwifery competencies.

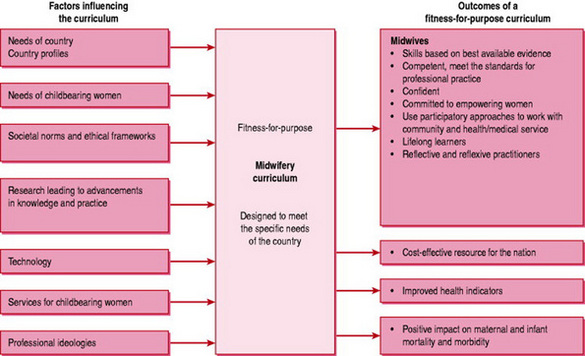

With the above in mind, many countries including Western countries such as the USA, Canada and New Zealand, have successfully introduced direct entry programmes into midwifery, while others are exploring the issue. Direct entry programmes have been well established in some countries such as France, the UK, and Holland as well as Chile and Indonesia to mention but a few, for many decades. Some feel that such programmes offer a greater opportunity for midwives to be acknowledged as autonomous practitioners and true partners in the team required for safe pregnancy and childbirth (Box 55.3). Such programmes would also allow developments based on a fitness-for-purpose model (Fig. 55.2). The fitness-for-purpose approach to curriculum planning looks at the required competencies of a midwife for that particular situation or country, and helps countries develop innovative and tailor-made programmes to suit the specifics of their own nation; as for example done by Canada, to address the specific midwifery needs of their First Nation’s (aboriginal) population (NAHO 2004).

Box 55.3 Midwifery in Canada: an autonomous direct entry profession by Bridget Lynch from the Canadian Midwives Association

(For more information on midwifery in Canada, visit the website of the Canadian Association of Midwives at: http://www.canadianmidwives.org)

In Canada, midwifery is legislated and regulated at a provincial rather than federal level. Since the early 1990s, six of ten provinces have legislated midwifery as a direct entry health profession, with legislation pending in two more provinces. Midwives in Canada are independent practitioners who provide primary care to low risk women and their newborns from conception to 6 weeks’ postpartum. Midwives are required by provincial regulation to attend women, as appropriate, in a woman’s choice of birthplace, whether in the home, in a birth centre, or in hospital. The midwives’ scope of practice includes admitting and discharge privileges in the hospital setting. Continuity of care, with a small group of midwives known to a woman providing care throughout her pregnancy, birth and the postpartum, is fundamental to the Canadian model of midwifery.

The route of entry to the profession is through a Bachelor of Science in Midwifery, offered in both francophone and anglophone university settings. There is also a process offered by provincial colleges, the regulators of the profession, to assess and register midwives who have been educated in jurisdictions outside of Canada. In several provinces, aboriginal midwives and the practice of aboriginal midwifery are recognized and protected through legislation. Midwifery services are funded through the public healthcare system.

Attempts are being made to strengthen the skills of midwives in many countries. However, this is complicated by the fact that identification of who is a midwife is not always easy. For example in a survey across the 10 countries that make up the WHO South-east Asia Region, there were approximately 18 different categories of worker providing maternity services, of which only seven had the word ‘midwife’ in their job title (WHO SEARO 1996). Some, such as the border midwives in Bhutan, had only 3 months’ training in midwifery and provide delivery (intrapartum)-only care, while others had 1-year midwifery after nursing programme and in Indonesia, midwives follow a 3-year direct entry diploma programme. At a recent regional meeting on nursing and midwifery, from data presented in the various country reports it would appear the situation has not changed and there remains a lack of clarity as to which cadres of maternity workers are truly competent in midwifery.

As outlined in the recent International Forum on community midwifery, one of the main difficulties facing the preparation of midwives is the lack of sufficient numbers of appropriately trained midwife teachers (Odberg-Pettersson et al 2007). Many countries, including some European countries, are currently without a standardized approved preparation for their midwife teachers. This is not new however and has been recognized as a problem for many years. It was partly the debate about strengthening midwifery education and in recognizing the needs of midwive teachers in some countries for additional teaching material, which led WHO to fund the development of the midwifery modules for safe motherhood.

Finally, issues around the omission of research from the midwifery curriculum also remain hotly debated. The lack of research appreciation and research skills in the formal curriculum in many countries is recognized as being detrimental to the preparation of critically thinking midwives. Lack of research training hampers development of the needed documentary evidence from operations research to show how best to strengthen midwifery and midwifery practice in under resourced countries. Midwives must have the capacity to be both proactive and responsive to the needs of individual mothers and babies. Without midwives who are active researchers, not simply research assistants or data gatherers for medical research, engaging upon midwifery research is difficult. Yet without such endeavours it is impossible to build up a sufficient evidence-base to midwifery practice. It is imperative therefore that each country has a mechanism by which some midwives are able to receive adequate preparation not just as expert clinicians and teachers, but also as researchers. Such research is not only essential for midwives and their clients, but is also needed by governments and other decision-makers, to assist with improving maternity services and care. What is needed to bring this to fruition however, yet lacking in too many under-resourced countries, is strong midwifery leadership coupled with sufficient management capacity, including and especially workforce planning, to be able to build an effective midwifery workforce.

Employment and the need for a positive practice environment

Another major problem facing many midwives worldwide includes issues surrounding employment and the environments in which midwives work. Changes such as the rise in HIV and demographic changes and increasing migration to city dwellings (bringing with it the demise of family support networks for childbearing women) will require different approaches to the provision of maternity services.

Mass urbanization, with its overcrowding, increased poverty and deprivation often leading to higher crime and violence, has resulted in an increased concern for the safety of midwives at work. Civil conflict, an increasing phenomenon in many parts of the world, also brings specific issues for midwives and the provision of quality midwifery care. Coupled with the likelihood of poor nutrition, poverty, and other factors that usually accompany civil conflict (the lack of access to medical care), the health of women and their newborns are at greater risk and so the midwife’s role becomes even more crucial. Sometimes the midwife is the only professional healthcare provider that women and their families have access to. However in these situations, both holding and obtaining equipment and drugs become a major issue for the midwife. Midwives in some places have been subject to violence against them because militia have thought they have drugs, which they need for their fighters. Such violence against midwives however is not just a feature of resource-poor countries or in conflict situations. Midwives working in large urban and periurban areas in almost any country of the world where there are high levels of drug-related crime, face such risks on a daily basis.

Demographic changes due to internal migration and increasingly to displacements of populations from conflict areas and/or natural disaster areas, bring with them an explosion of demands on the health services. The resulting economic burden laid on communities means that obtaining adequate remuneration for all public sector workers is a major issue. South Africa for example is facing such problems since the move to free healthcare following the political changes that marked the end of apartheid. Coupled with the effects of mass urbanization and the rise in HIV AID, South Africa is struggling with an overstretched health service, where demand exceeds hospital and district budgets. Midwives working in similar situations are being faced with many of the same problems (Box 55.4).

(Report of Zimbabwe midwifery representative at WHO technical meeting on strengthening midwifery services to support Making Pregnancy Safer, November 2001.)

Midwives in Zimbabwe have a long tradition and have done a great deal to strengthen midwifery care to ensure they meet the changes in society. One of the greatest challenges Zimbabwe has had to face in recent years has been the incredible rise in HIV/AIDS. The midwifery curricula have been revised to take on board HIV/AIDS and counselling. Currently, the country is busy strengthening midwifery education and services through offering a master’s degree with specialization in MCH and midwifery. However, these gains are being wiped out due to the current crisis, namely increased migration of midwives to other countries that are offering better salaries and packages including improving safety. Due to the staff shortage, the need for capacity building is greater than ever in the country. Sometimes even in the large hospitals there are not sufficient midwives and nurses and others are left to assist the woman during birth. The midwife then becomes a supervisor of staff rather than carrying out the skills she has been trained to do.

Finally, in many countries, despite the challenges placed on public services, setting up of independent community practice is difficult and is often devalued. Even some Western countries, including the UK and some states in the USA and Canada and Norway, are facing similar problems with independent midwifery as insurance companies can be reluctant for a variety of reasons to pay for this type of service. Often the reason for these problems relates to the close association of insurers with the medical profession, who are not always supportive of midwifery-led care. As funding of healthcare becomes increasingly reliant on insurance scheme, this is likely to become an increasing problem.

The success of the midwives in The Netherlands, Canada and New Zealand to have their services recognized as a legitimate option for pregnant women, does however offer hope (Donley 1989, Donley 1995, Smulders & Limburg 1995), but it should be remembered that these successes were as a result of hard-fought battles. In each case, although circumstances may be different, the force of medical opposition was enormous and the midwifery profession had to unite and work in partnership with women to achieve success. In both Canada and New Zealand the force of women’s support was paramount. This can be achieved only if women are free and able to offer this support – free in that they are not excessively burdened with malnutrition, ill health and poverty. Unfortunately in some countries, women’s status is low and many women are still being denied freedom to demand what should be a basic human right – the right to access care during pregnancy, childbirth and for the important months after, from a competent professional midwife.

Scope of midwifery practice increased in some countries

Increasingly, turbulence, war and political upheaval are posing new problems for midwifery. Violence against women is more than ever on the international agenda, despite the UN Convention on the elimination of all forms of discrimination against women (UN 1979) and the Declaration on violence against women (UN 1993). According to a large-scale scientific study conducted in collaboration with WHO it was revealed that between 10% and 50% of all women reported they had been subject to physical abuse by an intimate partner in their lifetime, much of the violence beginning in and around pregnancy (WHO 2005b).

Female genital mutilation is still a concern in many countries, as is the damage inflicted on women as a result of lack of appropriate healthcare in pregnancy and childbirth. Morbidity, especially pelvic floor problems, incontinence and vesicovaginal fistulae, and the provision of appropriate and safe reproductive healthcare for refugees and displaced persons, are perhaps the most pressing concerns for research and innovations by midwives. Such occurrences call for midwives in those countries to extend their practice into the broader sexual reproductive health and rights’ arena. Midwives in some of these countries are being trained to undertake limited surgical procedures such as performing a caesarean section and repairing vesicovaginal fistulae, as well as carrying out medical abortions and menstrual regulation. Therefore, despite the catalogue of challenges facing midwifery and midwives worldwide, there are signs that midwives are increasingly being seen as key workers and the current climate is favourable for strengthening and making midwifery more visible.

Conclusion

It is not possible to reflect all the issues or the different approaches being made by midwives in different countries in one short chapter. What is possible though, is to heighten all midwives’ awareness that today, more than ever, globalization does have an impact on the work of individual midwives in many countries, including those who practise only within their own country. Midwives must become more politically active if they are to bring about safe(r) motherhood in their own and other countries. It is clear that what is required to bring about safe motherhood in most countries is sufficient well-trained midwives and the resources to provide holistic quality care, including emergency obstetric care, which includes care of newborns with life-threatening conditions. Such care must be available close enough for all women to gain access to it. Equally, women must be able to influence the provision of care to ensure it is culturally acceptable. This requires action by community leaders, policy makers and politicians. Therefore midwives must become active in political debates concerning structures of society, especially the rights of women and women’s empowerment. In addition, if they are to be true advocates for mothers and newborns, midwives must also be able to identify and influence local leaders and key decision-makers in the community.

With this in mind there is a need to re-think the skills required in midwives seeking work experience and job opportunities in low income and resource-poor countries. It is no long sufficient to be a competent clinical midwife, but there is a need for midwives looking for such opportunities to have additional broader skills in leadership, management, especially in human resource planning and in teaching and research.

Finally, if midwives are to provide appropriate effective care anywhere in the world, they must always listen to and respect the women they seek to serve. For midwives working at an international level or working outside their own country, this means ensuring that it is the voices of women, including the midwives they work with (regardless of the gender of the midwife) that are heard and that it is their voice leading actions to strengthen midwifery.

Awases M, Gabary A, Nyoni J, et al. Migration of health professions in six countries: A Synthesis Report for World Health Organization Regional Office For Africa, Division of Health Systems and Services Development. South Africa: WHO AFRO, 2004.

Campbell O, Graham W. Strategies for reducing maternal mortality: getting on with what works. Lancet. 2006;368(9544):1284-1299.

Chitnis S. Feminism: Indian ethos and Indian convictions. In: Ghandially S, editor. Women in Indian society: a reader. London: Sage, 1988.

Collins P. Shifting the centre: race, class, and feminist theorizing about motherhood. In: Glenn E, Chang G, Forcey L, editors. Mothering ideology, experience, and agency. New York: Routledge, 1994.

Cook R, Dickens B. Advancing safe motherhood through reproductive rights, World Health Organization, Department of Reproductive Health and Research, Geneva, 2001. Online. Available http://who.int/reproductive-health/publications/RHR_01_5_advancing_safe_motherhood.

Dawit S, Busia A. Thinking about culture: some programme pointers. Gender development. Oxfam Journal. 1995;5(1):7-11.

de Bernis L, Sherratt DR, AbouZhar C, et al. Skilled attendants for pregnancy and childbirth. Rodeck C, editor. Pregnancy, Reducing maternal death and disability. British Medical Bulletin, 67. 2003, 39-57. Online. Available http://www.bmb.oupjournals.

De Brouwere V, Van Lerberghe W, editors. Safe motherhood strategies: a review of the evidence. Studies in Health Service Organization and Policy, 17. 2003, 7-33.

Donley J. Professionalism. The importance of consumer control over childbirth. New Zealand College of Midwives Journal, 1989, 6-7, September.

Donley J. Independent midwifery in New Zealand. In: Murphy-Black T, editor. Issues in midwifery. Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone, 1995.

Donney F, Weil L. Reproductive health and rights. Obstetric fistula: the international response. Lancet. 2004;363(9402):71-72.

Fullerton J, Thompson J. Examining the evidence for The International Confederation of Midwives’ essential competencies for midwifery practice. Midwifery. 2005;21(1):2-13.

Gill K, Pande R, Malhotra A. Women deliver for development. Lancet. 2007;370(9595):1347-1357.

Goodburn E. Maternal morbidity in rural Bangladesh: an investigation into the nature and determinants of maternal morbidity related to delivery and the puerperium. Dhaka: Bangladesh Rural Advancement Committee, 1995.

Graham W, Bell J, Bullough CHW. Can skilled attendance at delivery reduce maternal mortality in developing countries?. De Brouwere V, Van Lerberghe WV, editors. Safe motherhood strategies: a review of the evidence. Studies in Health Services Organization and Policy, 17. 2001, 97-130.

Gülmezoglu AM, Say L, Betrán AP, et al. WHO systematic review of maternal mortality and morbidity: methodological issues and challenges. BMC Medical Research Methodology, 5. 2004;4:16. Online. Available http://www.biomedcentral.com/1471–2288/4/16.

ICM (International Confederation of Midwives). International code of ethics for midwives. 1999. Online. Available http://www.interntionalmidwives.org.

ICM (International Confederation of Midwives). A birthday for midwives: seventy five years of international collaboration. The International Confederation of Midwives 1919–1994. ICM, London, 1994.

ICM (International Confederation of Midwives). Essential competencies for midwives, 2002 ICM. Online Available http://www.interntionalmidwives.org.

Koblinsky M, editor. Reducing maternal mortality: learning from Bolivia, China, Egypt, Honduras, Indonesia, Jamaica and Zimbabwe. Human Development Network. Health, Nutrition and Population Series. Washington, DC: The World Bank, 2003.

Koblinsky M, Matthews Z, Hussein J, et al. Going to scale with professional skilled care. Lancet. 2006;368(9544):1377-1386.

Kunst A, Howlling T. A global picture of poor-rich differences in the utilization of delivery care. De Brouwere V, Van Lerberge W, editors. Safe motherhood strategies: a review of the evidence. Studies in Health Services Organization and Policy, 17. 2001, 297-315.

Kwast B, Bentley J. Introducing confident midwives: midwifery education – action for safe motherhood. Midwifery. 1991;7:8-19.

Kwast B, Bergström S. Training professionals for safe motherhood. In: Lawson JB, Harrison KA, Bergström S, editors. Maternity care in developing countries. London: RCOG Press, 2001.

Latham MC, Prebble EA. Appropriate feeding methods for infants of HIV infected mothers in sub-Saharan Africa. British Medical Journal. 2000;328:1656-1659.

Loudon I. Maternal mortality in the past and its relevance to the developing world today. American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 2000;1S:241S-246S.

Mensah K, Mackintosh M, Henry L. The ‘skills drain’ of health professionals from the developing world: a framework for policy formation. London: Medact, 2005.

Miller S, Sloan NL, Winikoff B, et al. Where is the ‘E’ in MCH? The need for evidence-based approach to safe motherhood. Journal of Midwifery Women’s Health. 2003;48(1):10-18.

Mullay B. Barriers to and attitudes towards promoting husbands’ involvement in maternal health in Katmandu, Nepal. Social Science and Medicine. 2006;62(11):2798-2809.

NAHO (National Aboriginal Health Organization). Midwifery and Aboriginal midwifery in Canada. Ottowa: NAHO, 2004.

Odberg-Pettersson K, Sherratt DR, Mayo NT. Midwifery in the Community: lessons learnt. International Forum on training and scaling up midwives. New York: UNFPA, 2007. Final Report

Penny S, Murray S. Training initiatives for essential obstetric care in developing countries: a ‘state of the art’ review. Health Policy and Planning. 2000;14(4):286-393.

Portela A, Santarelli C. Empowerment of women, men, families, and communities: true partners for improving maternal and newborn health. Rodeck C, editor. Pregnancy, reducing maternal death and disability. British Medical Bulletin, 67. 2003, 59-72. Online. Available http://www.bmb.oupjournals.

Royston E, Armstrong S. Preventing maternal deaths. Geneva: WHO, 1989.

Sherratt DR. Towards MDG 5: Scaling up the capacity of midwives to reduce maternal mortality and morbidity. In: Odberg Pettersson K, Sherratt DR, editors. Midwifery in the community: lessons learnt. International forum on training and scaling up midwives. New York: UNFPA; 2007:21-23. Final Workshop Report. March

Smulders B, Limburg A. Obstetrics and midwifery in the Netherlands. In: Kitzinger S, editor. The midwifery challenge. London: Pandora, 1995.

Stanton C, Blanc AK, Croft T, et al. Skilled care at birth in the developing world: progress to date and strategies for expanding coverage. Journal of Biosocial Science. 2007;39(1):109-120.

Starrs A, IAGSM. The Safe Motherhood Action Agenda: Report on the Safe Motherhood Technical Consultation, 18–23 October 1997, Colombo, Sri Lanka. New York: Inter Agency Group for Safe Motherhood, 2000.

Thompson J, Bennett R. Women are dying: midwives in action. Background paper for ICM/WHO/UNICEF Pre-Congress Safe Motherhood Workshop. Oslo: WHO/ICM, 1996. May

UN (United Nations). Convention on the elimination of all forms of discrimination against women. New York: UN, 1979.

UN (United Nations). The convention on the rights of the child. New York: UN, 1990.

UN (United Nations). Declaration on violence against women. New York: UN, 1993.

UNICEF (United Nations Children’s Fund). The progress of nations. New York: UNICEF, 1993.

UNICEF (United Nations Children’s Fund). The state of the world’s children: 1997 summary. New York: UNICEF, 1997.

UNICEF (United Nations Children’s Fund). Cracking the code (code no. 16027). Essex: UNICEF, 1997.

Wagner M. Pursuing the birth machine: the search for appropriate birth technology. Camperdown: Ace Graphics, 1994.

WB (World Bank). World Development Report 2004. Making services work for poor people. World Bank, Washington DC, 2005.

WHO (World Health Organization). Maternal mortality: a global factbook. Geneva: WHO, 1991.

WHO (World Health Organization). The application of the WHO partograph in the management of labour. Maternal Health and Safe Motherhood Programme, Division of Family Health. Geneva: WHO, 1994.

WHO (World Health Organization). Mother–baby package: a practical guide to implementing safe motherhood in countries. Maternal Health and Safe Motherhood Programme, Division of Family Health. Geneva: WHO, 1994.

WHO (World Health Organization). Normal birth. Safe Motherhood Programme. Maternal Health and Safe Motherhood Programme, Division of Family Health. Geneva: WHO, 1996.

WHO (World Health Organization). Revised 1990 estimates of maternal mortality: a new approach by WHO and UNICEF. Geneva: WHO, 1996.

WHO (World Health Organization). Management of complications in pregnancy and childbirth: guidelines for midwives and doctors. Geneva: WHO, 2000.

WHO (World Health Organization). Maternal mortality in 1995: Estimates developed by WHO, UNICEF, UNFPA. Geneva: WHO, 2001.

WHO (World Health Organization). New data on the prevention of Mother-to-Child Transmission of HIV and their policy implications. Technical consultation: UNFPA/UNICEF/ WHO/UNAIDS Inter-Agency Team–Conclusions and recommendations. Geneva: WHO Department of Reproductive Health and Research, 2001.

WHO (World Health Organization). Making pregnancy safer: the critical role of the skilled attendant. A Joint Statement by WHO ICM FIGO. Geneva: WHO, 2004.

WHO (World Health Organization). HIV transmission: a Review of Available Evidence. Geneva: WHO Department of Child and Adolescent Health and Development and Department of Nutrition, 2004.

WHO (World Health Organization). World Health Report 2005. Make every mother and child count. Geneva: WHO, 2005.

WHO (World Health Organization). Multi-country study on women‘s’ health and domestic violence against women. Geneva: WHO Department of Gender and Women’s Health, 2005.

WHO (World Health Organization). World Health Report 2006. Working together for health. Geneva: WHO, 2006.

WHO (World Health Organization). Neonatal and perinatal mortality – country, regional and global estimates. Geneva: WHO, 2006.

WHO (World Health Organization). Proportion of births attended by a skilled attendant – 2007 updates, WHO Department of Reproductive Heath and Research, Geneva, 2007. Online. Available http://www/who.int/ reproductive-health/global_monitoring/skilled_attendant_atbirth2007.

WHO, ICM. Midwifery education modules: education for safe motherhood, 2nd edn. WHO Department of Making Pregnancy Safer, Geneva, 2007. Online Available http://www/who.int/making_pregnancy_safer.

WHO SEARO (World Health Organization South-East Asia Regional Office). Standards for midwifery practice for safe motherhood. Working Paper 1: An inter-country consultation. New Delhi, India: WHO/SEARO, 1996. November

WHO, United Nations Children’s Fund. Protecting, promoting and supporting breastfeeding: the special role of maternity services. Geneva: WHO, 1989.

WHO, United Nations Children’s Fund. Baby-friendly hospital initiative: Revised, updated and expanded for integrated care: Section 1: Country Implementation. 2006. Online Available http://www.who.int/nutrition/topics/BFHI_Revised_Section1.pdf.

WHO, United Nations Children’s Fund, International Confederation of Midwives. Midwifery education action for safe motherhood: report of a collaborative pre-congress workshop, Kobe, Japan, 5–6 October 1990. Geneva: WHO, 1991.

WHO/United Nations Population Fund/United Nations Children’s Fund/World Bank. Reducing maternal mortality. Geneva: WHO, 1999.

Berer M, Sundari Ravindran TK, editors. Safe Motherhood Initiatives: critical issues. London: Blackwell Science, 1999.

Devries R, Benoit C, Van Teijlingen, Wrede S. Birth by design pregnancy, maternity care, and midwifery in North America and Europe. New York: Routledge, 2001.

A good review of the policies and development of maternity care in Europe and North America.

Jeffrey P, Jeffrey R, Lyon A. Labour pains and labour power: woman and childbearing in India. London: Zed Books, 1988.