CHAPTER 1 Partially Edentulous Epidemiology, Physiology, and Terminology

This textbook focuses on what the clinician should know about partially edentulous patients to appropriately provide comfortable and useful tooth replacements in the form of removable partial dentures. Removable partial dentures are a component of prosthodontics, which denotes the branch of dentistry pertaining to the restoration and maintenance of oral function, comfort, appearance, and health of the patient by the restoration of natural teeth and/or the replacement of missing teeth and craniofacial tissues with artificial substitutes.

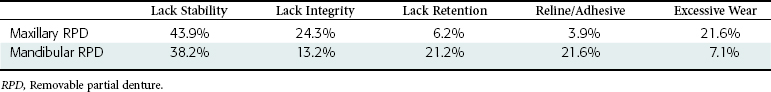

Current practice in the management of partial tooth loss involves consideration of various types of prostheses (Figure 1-1). Each type of prosthesis requires the use of various remaining teeth, implants, and/or tissues, and consequently demands appropriate application of knowledge and critical thinking to ensure the best possible outcome given patient needs and desires. Although more than one prosthesis may serve the needs of a patient, any prosthesis should be provided as part of overall management that meets the basic objectives of prosthodontic treatment, which include (1) the elimination of oral disease to the greatest extent possible; (2) the preservation of the health and relationships of the teeth and the health of oral and paraoral structures, which will enhance the removable partial denture design; and (3) the restoration of oral functions that are comfortable, are esthetically pleasing, and do not interfere with the patient’s speech. It is critically important to emphasize that the preservation of health requires proper maintenance of removable partial dentures. To provide a perspective for understanding the impact of removable partial denture prosthodontics, a review of tooth loss and its sequelae, functional restoration with prostheses, and prosthesis use and outcomes is in order.

Figure 1-1 A, Fixed partial dentures that restore missing anterior (#10) and posterior (#5, #13) teeth. Teeth bordering edentulous spaces are used as abutments. B, Clasp-type removable partial denture restoring missing posterior teeth. Teeth adjacent to edentulous spaces serve as abutments. C, Tooth-supported removable partial denture restoring missing anterior and posterior teeth. Teeth bounding edentulous spaces provide support, retention, and stability for restoration. D, Mandibular bilateral distal extension removable partial denture restoring missing premolars and molars. Support, retention, and stability are shared by abutment teeth and residual ridges.

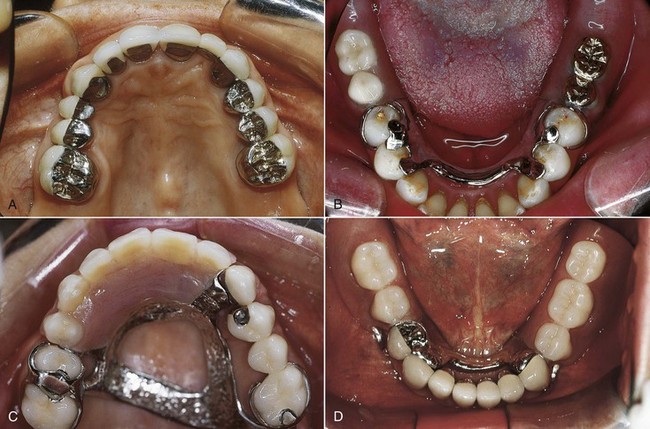

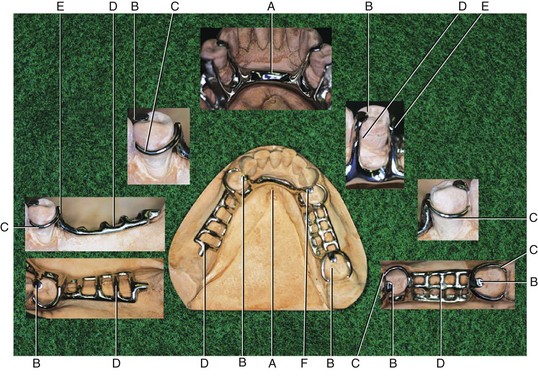

Familiarity with accepted prosthodontic terminology related to removable partial dentures is necessary. Figures 1-2 and 1-3 provide prosthesis terms related to mandibular and maxillary frameworks, and Appendix A provides a review of selected prosthodontic terms. Additional terminology can be reviewed in The Glossary of Prosthodontic Terms1 and a glossary of accepted terms in all disciplines of dentistry, such as Mosby’s Dental Dictionary, second edition.2

Figure 1-2 Mandibular framework designed for a partially edentulous arch with a Kennedy Classification II, modification 1 (see Chapter 3). Various component parts of the framework are labeled for identification. Subsequent chapters will describe their function, fabrication, and use. A, Major connector. B, Rests. C, Direct retainer. D, Minor connector. E, Guide plane. F, Indirect retainer.

Figure 1-3 Maxillary framework designed for a partially edentulous arch with a Kennedy Classification I (see Chapter 3). As in Figure 1-2, component parts are labeled for identification. A, Major connector. B, Rests. C, Direct retainer. D, Minor connector. E, Guide plane. F, Indirect retainer.

Tooth Loss and Age

It should come as no surprise that tooth loss and age are linked. A specific tooth loss relationship has been documented with increasing age because some teeth are retained longer than others. It has been suggested that in general an interarch difference in tooth loss occurs, with maxillary teeth demonstrating loss before mandibular teeth. An intraarch difference has also been suggested, with posterior teeth lost before anterior teeth. These observations are likely related to respective caries susceptibilities, which have been reported (Table 1-1). Frequently the last remaining teeth in the mouth are the mandibular anterior teeth, especially the mandibular canines, and it is a common finding to see an edentulous maxilla opposing mandibular anterior teeth.

Table 1-1 Caries Risk Assessment*

| High Risk | Lower 6 and 7 | Mandibular 1st and 2nd molars |

| Upper 6 and 7 | Maxillary 1st and 2nd molars | |

| Low Risk | Upper 3 and lower 4 | Maxillary canine, Mandibular 1st premolar |

| Lower 1, 2, 3 | Mandibular central, Lateral incisors, Canines |

* If tooth loss parallels caries activity, caries risk may be a proxy for tooth loss.

Data from Klein H, Palmer CE: Studies on Dental Caries: XII. Comparison of the caries susceptibility of the various morphological types of permanent teeth. J Dent Res 20:203-216, 1941.

If one accepts that tooth loss and age are linked, how will this affect current and future dental practice? Replacement of missing teeth is a common patient need, and patients will demand it well into their elderly years. Current population estimates show that 13% of the U.S. population is 65 years of age or older. By the year 2030, this percentage is expected to double, with a significant increase also expected worldwide. These individuals are expected to be in better health, and health care strategies for this group should focus on maintenance of active and productive lives. Oral health care is expected to be a highly sought after and significant component of overall health care.

Tooth loss patterns associated with age are also evolving. The proportion of edentulous adults has been reported to be decreasing, although this varies widely by state. However, it has been reported that the absolute number of edentulous patients who need care is actually increasing. More pertinent to this text, estimates suggest that the need for restoration of partially edentulous conditions will also be increasing. An explanation for this is presented in an argument that 62% of Americans of the “baby boomer” generation and younger have benefited from fluoridated water. The result of such exposure has been a decrease in caries-associated tooth loss. In addition, current estimates suggest that patients are keeping more teeth longer, demonstrated by the fact that 71.5% of 65- to 74-year-old individuals are partially edentulous (mean number of retained teeth = 18.9). It has been suggested that partially edentulous conditions are more common in the maxillary arch, and that the most commonly missing teeth are first and second molars.

Consequences of Tooth Loss

Anatomic

With the loss of teeth, the residual ridge no longer benefits from the functional stimulus it once experienced. Because of this, a loss of ridge volume—both height and width—can be expected. This finding is not predictable for all individuals with tooth loss, as the change in anatomy has been reported to be variable across patient groups. In general, bone loss is greater in the mandible than in the maxilla and more pronounced posteriorly than anteriorly, and it produces a broader mandibular arch while constricting the maxillary arch. These anatomic changes can present challenges to fabrication of prostheses, including implant-supported prostheses and removable partial dentures. Associated with this loss of bone is an accompanying alteration in the oral mucosa. The attached gingiva of the alveolar bone can be replaced with less keratinized oral mucosa, which is more readily traumatized.

Physiologic

What are we replacing when we consider managing missing teeth? We are replacing both the physical anatomic tools for mastication and the oral capacity for neuromuscular functions to manipulate food. Chewing studies have shown that the oral sensory feedback that guides movement of the mandible in chewing comes from a variety of sources. The most sensitive input, which means the input that provides the most refined and precisely controlled movement, comes from periodontal mechanoreceptors (PMRs), with additional input coming from the gingiva, mucosa, periosteum/bone, and temporomandibular joint (TMJ) complex.

Chewing as a learned behavior has a basic pattern of movement that is generated from within the central nervous system. In typical function, this patterned movement is moderated on the basis of food and task needs by oral sensory input from various sources. With loss of the finely tuned contribution from tooth PMRs, the resulting peripheral receptor influence is less precise in muscular guidance, producing more variable masticatory function, and the type of prosthesis selected to replace missing teeth may potentially contribute to functional impediments.

The esthetic impact of tooth loss can be highly significant and may be more of a concern to a patient than loss of function. It is generally perceived that in today’s society, loss of visible teeth, especially in the anterior region of the mouth, carries with it a significant social stigma. With loss of teeth and diminishing residual ridge, facial features can change as the result of altered lip support and/or reduced facial height caused by a reduction in occlusal vertical dimension. Restoring facial esthetics in a manner that maintains an appropriate appearance can be a challenge and is a major factor in restoration and maintenance decisions made for various prosthetic treatments.

Functional Restoration with Prostheses

Individuals with a full complement of teeth report some variation in their levels of masticatory function. The loss of teeth may lead patients to seek care for functional reasons if they notice diminished function to a level that is unacceptable to them. The level at which a patient finds function to be unacceptable varies among individuals. This variability increases with accelerating tooth loss. These variables may be confusing to clinicians, who may perceive that they have provided prostheses of equal quality to different patients with the same tooth loss patterns, and yet have received different patient reports of success.

An understanding of these variations among individuals with a full complement of teeth and those with prostheses can help clinicians formulate realistic treatment goals that can be communicated to the patient. A review of oral function, especially mastication, may help interested clinicians better understand issues related to the impact of removable partial denture function.

Mastication

Although functionally considered as a separate act, mastication as part of the feeding continuum precedes swallowing and is not an end in itself. The interaction of the two distinct but coordinated aspects of feeding suggests that some judgment of mastication termination or completeness precedes the initiation of swallowing. Although the mastication-swallowing sequence is obvious, the interaction of the two functions is not widely understood and may be important to prosthesis use when removable partial dentures are considered.

Mastication involves two discrete but well-synchronized activities: subdivision of food by applied force, and selective manipulation by the tongue and cheeks to sort out coarse particles and bring them to the occlusal surfaces of teeth for further breakdown. The initial subdivision or comminution phase involves the processes of selection, which refers to the chance that a particle is placed between the teeth in position to be broken, and breakage, which is the degree of fragmentation of a particle once selected. The size, shape, and texture of food particles provide the sensory input that influences the configuration and area of each chewing stroke. Larger particles are selectively reduced in size more rapidly than fine particles in efficient mastication. The process of mastication is therefore greatly influenced by factors that affect physical ability to reduce food and to monitor the reduction process by neurosensory means.

Food Reduction

Teeth or prostheses serve the role of reducing food to a point ready for swallowing. An index of food reduction is described as masticatory efficiency, or the ability to reduce food to a certain size in a given time frame. A strong correlation has been shown between masticatory efficiency and the number of occluding teeth in dentate individuals, which would suggest variability of particle selection related to contacting teeth. Performance measures reveal a great deal of functional variability in patients with similar numbers of contacting teeth, and even greater variability is seen within populations with greater loss of teeth (increasing degrees of edentulousness).

Because occlusal contact area is highly correlated with masticatory performance, the loss of molar teeth would be expected to have a greater impact on measures of performance in that the molar has a larger occlusal contact area. This effect has been demonstrated in individuals with missing molars who reveal a greater number of chewing strokes required and a greater mean particle size before swallowing. The point at which an individual is prepared to swallow the food bolus is another measure of performance and is described as the swallowing threshold. Superior masticatory ability that is highly correlated with occlusal contact area also achieves greater food reduction at the swallowing threshold. Conversely, a diminished ability to chew is reflected in larger particles at the swallowing threshold.

These objective measures, which show a benefit to molar contact in dentate individuals, are in conflict with some subjective measures from patients who express no perceived functional problems associated with having only premolar occlusion. This shortened dental arch concept has highlighted that patient perceptions of functional compromise, as well as benefit, should be considered when it is decided whether to replace missing molars. When the loss of posterior teeth results in an unstable tooth position, such as distal or labial migration, tooth replacement should be carefully considered; this is a separate situation from the shortened dental arch concept.

It has been reported that prosthetic replacement of teeth provides function that is often less than that seen in the complete, natural dentition state. Functional measures are closest to the natural state when replacements are fixed partial dentures rigidly supported by teeth or implants, intermediate in function when replacements are removable and supported by teeth, lower in function when replacements are removable and supported by teeth and edentulous ridges, and lowest in function when replacements are removable and supported by edentulous ridges alone.

Objective and subjective measures of a patient’s oral function often are not in agreement. It has been shown that subjective measures of masticatory ability are often overrated compared with objective functional tests, and that for complete denture wearers, the subjective criteria may be more appropriate in monitoring perceived outcomes. Some literature reports that removable partial dentures can be described by patients as adding very little benefit over no prostheses. However, these findings may be related to a number of factors, including lack of maintenance of occluding tooth relationships, limitations of this form of dental prosthesis for patient populations that may be unreliable in maintaining follow-up visits, and intrinsic variation in patient response to prostheses.

Food reduction is also influenced by the ability to monitor the process required to determine the point at which swallowing is initiated. As was mentioned earlier, the size, shape, and texture of food are monitored during mastication to allow modification in mandibular movement for efficient food reduction. This has been demonstrated in dentate individuals given food particles of varying size and concentration suspended in yogurt, who revealed that increased concentrations and particle size required more time to prepare for swallowing (i.e., greater swallowing threshold). These findings suggest that the oral mucosa has a critical role in detecting characteristics necessary for efficient mastication. The influence of the removable partial denture on the ability of the mucosa to perform this role in mastication is not known.

Current Removable Partial Denture Use

Given an understanding of the relationship between tooth loss and age, the consequences of tooth loss, and our ability to restore function with removable partial prostheses, what do we know about current prosthesis use for these conditions, and what are some common clinical outcomes? A recent study estimated 21.4% prosthesis use among individuals aged 15 to 74. In the 55- to 64-year-old group, 22.2% were found to wear a removable partial denture. This age group has the highest use of removable partial dentures among those reviewed. It has been suggested that the use of removable partial dentures among individuals aged 55 years or older is even greater.

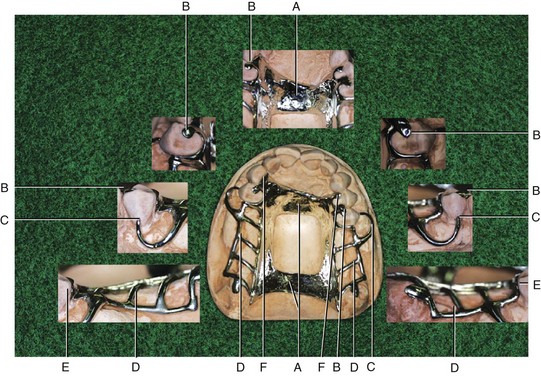

Analysis of this study provides some useful information for consideration. Partially edentulous individuals not wearing a prosthesis were 6 times more likely to have missing mandibular teeth (19.4%) than missing maxillary teeth (2.2%). This might suggest greater difficulty in the use of a mandibular prosthesis. The distribution of prostheses used in this large patient group is shown in Table 1-2. The prostheses in this large study were evaluated on the basis of five technical quality characteristics: integrity, excessive wear of posterior denture teeth, the presence of temporary reline material or tissue conditioner or adhesive, stability, and retention. As seen in Table 1-3, lack of stability was the most common characteristic noted. In the maxilla, lack of stability was 7 times more prevalent than lack of retention. In the mandible, lack of stability was 1.8 times more prevalent than lack of retention. In another study, rest form, denture base extension, stress distribution, and framework fit were identified as common flaws associated with poor removable partial dentures. These characteristics are directly related to the functional stability of prostheses.

Table 1-2 Distribution of Prostheses

| Removable partial dentures | RPD/RPD 9.0% | RPD/–15.3%, –/RPD 4.5% |

| Complete dentures | CU/CL 3.8% | CU/–20.7% |

| Combination | CU/RPD 11.5% | RPD/CL 0.3% |

CL, Complete lower denture; CU, complete upper denture; RPD, removable partial denture. Natural teeth denoted with dash (–).

Need for Removable Partial Dentures

What does all this information mean to us today? It means a number of things that are important to consider. The need for partially edentulous management will be increasing. Patient use of removable partial dentures has been high in the past and is expected to continue in the future. Some patients who are given the choice between a prosthesis entirely supported by implants or a removable partial denture are not able to pursue implant care. This contributes to higher use of removable partial dentures.

Finally, these findings suggest that we should strive to understand how to maximize the opportunity for providing and maintaining stable prostheses because this is the most frequently deficient aspect of removable partial denture service. Consequently, throughout this text the basic principles of diagnosis, mouth preparation, prosthesis design, fabrication, placement, and maintenance will be reinforced to improve the reader’s understanding of care of removable partial denture prostheses.