In Transition to Adulthood

The Occupations and Performance Skills of Adolescents

1 Describe the physical, psychological, and social development that occurs in adolescence.

2 Examine the areas of occupation and occupations that promote and support adolescent development.

3 Recognize the interrelationship between health and psychosocial adolescent development.

4 Discuss how developmental issues of adolescents influence and guide the choice of therapeutic activities and interventions.

5 Highlight how parents and practitioners can promote self-determination and opportunities for exploration in adolescence for teens with disabilities.

6 Identify the role and responsibilities of an occupational therapy practitioner in facilitating participation by adolescents with disabilities.

This chapter provides an overview of the physical, cognitive, and psychosocial development that characterizes adolescence. Instead of providing a comprehensive guide to “typical” adolescent development, information that is readily available in human development textbooks, it focuses on the developmental issues that influence adolescents’ participation in occupations and occupational performance. In particular, the chapter explores the affect of disabilities and chronic health conditions on adolescents’ experiences and participation in age-related occupations. The information in this chapter comes with the caveat that occupational therapy practitioners need to see each adolescent as an individual and apply knowledge of typical development judiciously, cognizant that variability in development is normal. The client’s strengths, goals, needs, priorities, context (e.g., socioeconomic, cultural), and current developmental status are all part of a comprehensive evaluation and intervention plan.

ADOLESCENCE

Of all the stages of life adolescence is the most difficult to describe. Any generalization about teenagers immediately calls forth an opposite one. Teenagers are maddeningly self-centered, yet capable of impressive acts of altruism. Their attention wanders like a butterfly, yet they can spend hours concentrating on seemingly pointless involvements. They are lazy and rude, yet when you least expect it they can be loving and helpful (p. xiii).23

Adolescents live mostly in the moment. They have moments of joy and pleasure, overwhelming loneliness and isolation, laughter and fun, unbearable emotional pain, anger, frustration, and embarrassment, which are equal to moments of supreme confidence and perceived immortality. They want the security of family, but push boundaries, demanding to be seen as grown up. They desire and experience the closeness of peer friendships; they experience the pleasure and anxiety of exploring intimacy; and they have intense and seemingly eternal passion for clothes, music, sports, or other interests, which for a week, a month, or year are all-absorbing. More than anything, they wish to belong, to fit in, to be seen the same as others, while at the same time wishing to be unique. These are the experiences of all American teenagers. In Case Study 4-1, Caroline, whose teenage sister is intellectually developmentally disabled, speaks to the universality of being a teenager.

ADOLESCENT DEVELOPMENT

Adolescence is generally defined as the high school years (between 12 and 18), which are associated with physical maturation and puberty. This intense period of physical and physiologic (biologic) maturation and psychosocial development influences an adolescent’s ability to think, relate, and act as a competent adult. Adolescence is also a period of learning, experimentation, and experiences that affect individuals’ choice of long-term occupations and their physical and psychological well-being. Box 4-1 lists facts about American teenagers.

In observing the developmental process of adolescence, occupational therapy practitioners observe adolescents’ growth and their physical, emotional, and psychological changes; how adolescents perform common age-related tasks; how they choose occupations; and what experiences they seek. The age-related tasks and experiences are crucial to the process of gaining physical and financial independence from parents and redefining their psychological and emotional relationships with their parent. As they develop, adolescents establish norms and lifestyles congruent with the values and culture of their peers and their families. They accept and explore the physical and sexual development of their bodies. They work to establish their gender, personal, moral, and occupational identity. When successfully navigated, adolescence culminates in an overall state of well-being and the transition to adulthood and adult roles. Failure to integrate and engage in the roles and tasks of adolescence can result in ongoing physical and psychosocial difficulties that will affect future occupational performance and roles.51

Effective occupational therapy interventions begin with an evaluation of physical, cognitive, and psychosocial factors associated with adolescents’ development and the quality of their occupational performance. This includes standardized criterion-referenced (based on performance expected of an adolescent) or norm-referenced (based on actual performance of other adolescents) assessments that evaluate client factors and performance. Only interventions based on thorough evaluation are likely to be age appropriate and promote performance skills. Therefore, a working knowledge of adolescent development and awareness of occupations that facilitate age-appropriate development are fundamental to effective occupational therapy with adolescents. This chapter provides an overview of adolescent development intended to guide occupational therapy evaluations and interventions with the adolescent population.

PHYSICAL DEVELOPMENT AND MATURATION

Adolescence is characterized by the biologic and physiologic changes of puberty, dramatic increases in height and weight, and changes in body proportion. The age for the onset of puberty is variable and a child may begin to notice these changes from ages 8 to 14 years. The stimulus for this physical growth and physiologic maturation of reproductive systems is a complex interaction of hormones. It involves the hypothalamus and the pituitary gland that releases hormones that control growth and stimulate the release of sex-related hormones from the thyroid, adrenal glands, and the ovaries and testes (collectively referred to as the gonads).92

The growth and sex-related hormones initiate a period of rapid physical growth, which varies in intensity, onset, and duration. In this growth phase, people gain approximately 50% of their adult weight and 20% of their adult height. This process, which generally lasts about four years, can start as early as 9 years of age and may continue in some adolescents to age 17. In the United States, the average peak of growth occurs around age 11 for girls and age 13 for boys.

Growth of the skeletal system is not even: head, hands, and feet reach their adult size earliest. Bones become longer and wider. Calcification, which replaces the cartilaginous bone composition of childhood, makes bones denser and stronger. Muscles also become stronger and larger. This process of skeletal growth and muscle development culminates in increased overall strength and endurance for physical activities. Increases in strength are greatest about 12 months after adolescents’ height and weight have reached their peak, and is associated with an overall improvement in motor performance, including better coordination and endurance. Increases in muscle mass and heart and lung function are typically greater in boys than in girls. This growth is the basis of the difference in strength and gross motor performance between males and females.20 Motor performance peaks for males in late adolescence around 17 to 18 years of age.16 Girls typically show an increase in motor performance, including enhancements in speed, accuracy, and endurance, around the age of 14. However, the changes in motor performance in girls are highly variable and are influenced by a complex interaction of physical and social factors such as their musculoskeletal development, onset of menses, personal interests, motivation, and participation in physical activities.16

An adolescent finds security and social confidence in fitting within the “norm” for physical development, and perceived physical competency in activities such as sports builds self-esteem, particularly for young males. Early maturing teens’ self-confidence benefits from enhanced physical performance and enhanced social status. However, expectations of coaches, parents, and peers to excel at sport from can add unwelcome pressure and anxiety. These adolescents are more concerned with being liked and are likely to adhere to rules and routines. Adolescents who achieve the “desired standard” for physical appearance and/or level of physical performance (e.g., high school sports teams with high visibility such as football, cheerleading, or basketball) receive validation and approval from their peers and from adults. Hence, during adolescence, early-maturing boys are reportedly more popular, described as better adjusted, more successful in heterosexual relationships, and more likely to be leaders at school. Conversely, late maturing boys are reported to feel self-conscious about their lack of physical development.42

Physical Activities and Growth: Teenagers with Disabilities

Physical activity is important for the health of all teens, including those with physical, emotional, or cognitive disabilities. Participation in physical activities maintains functional mobility, enhances well-being and overall health, and provides opportunities for social interaction with peers. However, compared with nondisabled teens, adolescents with disabilities are less likely to engage in regular physical activity.44 For example, adolescents with cerebral palsy report walking less than they did as children.2

Scholars have frequently reported that physical functioning (e.g., mobility) deteriorates in adolescents with congenital physical disabilities because of secondary musculoskeletal impairments associated with adolescent growth.2,100 These secondary impairments include an inability of muscles to lengthen in proportion to bone growth, deterioration of joint mobility due to contractures, fatigue, overuse syndromes, obesity, and early joint degeneration. However, recent evidence does not support that such deterioration in performance is inevitable.85 Studies have shown maintenance or improvement in teens with disabilities who engage in physical fitness and/or therapy programs.3,85 Activity/exercise programs have resulted in adolescents’ improving and maintaining gross motor function and walking speed. The achieved independence promotes self-efficacy.60 For example, Darrah et al. reported that teens with cerebral palsy who participated in a community-based fitness program showed significant gains in strength and reported improved psychosocial skills at school.24

Occupational therapy practitioners take an active role in assisting teens to identify opportunities for physical activity within supportive environments (e.g., teams and physical fitness programs that accommodate and welcome adolescents with disabilities). They work with the teen’s education team to facilitate inclusion in junior high and high school sports and fitness programs as specified as goals in a teen’s individual education program (IEP). Physical activities can also include programs outside of school, such as summer camps and community activities. All such activities strengthen occupational performance skills and promote physical and emotional health.

Physical growth in adolescents with disabilities can lead to performance difficulties that require occupational therapy interventions. For example, changes in height and weight often require reassessment at the level of client factors (e.g., positioning, balance, strength, and coordination) that affect clients’ occupational performance and activities of daily living (ADL). Clients may need new or modified assistive devices mobility aids (e.g., a wheelchair); they may also need new adaptive strategies, strengthening, and endurance training to ensure full participation in their occupations. With new environmental and activity demands1 such as transitioning between classrooms in high school, some teens elect to conserve their energy and use a wheelchair instead of crutches or replace a manual chair with a powered chair.

Teens with progressive disorders (e.g., spinal muscular atrophy, Friedreich’s ataxia, and muscular dystrophy) may require ongoing therapy as their functional abilities deteriorate. For example, boys with Duchenne’s muscular dystrophy, the most common type of muscular dystrophy, use wheelchairs by early adolescence for functional mobility because of their progressive muscle weakness. Their ability to use their hands and fingers for eating, writing, and keyboarding abilities becomes weaker throughout their adolescence. Respiratory and trunk muscles become progressively weaker, and scoliosis and other skeletal deformities including joint contractures at the ankles, knees, elbows, and hips are common. With these adolescents, occupational therapy practitioners have an active role in facilitating adaptation to the progressive loss of motor function. Often they implement compensatory strategies such as wheelchair seating to maintain skeletal stability, splinting to prevent deformities, and assistive technology (e.g., voice recognition software for computers) to maintain occupational performance.

Primary caregivers must also adjust to the physical growth and physiologic maturation of the adolescent. Adolescence can be challenging, especially for parents/caregivers of adolescents with moderate to severe physical disabilities and/or mental retardation, because of the continued and, at times, increased levels of care required. For example, transferring small children into and out of vehicles, lifting them into the shower, and dressing them are relatively easy. As the adolescent grows and gains weight, these caregiving tasks become more difficult. Significant household modifications may be needed to accommodate the changes, and additional adapted equipment, such as the use of commode chair or hoists for transfers, may be required for basic ADLs.

In other situations, such as when an adolescent is developmentally disabled, the family’s challenge is to encourage more autonomy and independence in self-care to prepare for a transition to semi-independent settings such as a group home. This can require that parents reduce supervision and the adolescent develop independence in new self-care routines, such as shaving or managing menses.

Although the occupational therapy practitioner effectively addresses practical needs with adolescents and parents, it is equally important that the practitioner be aware of the emotional adjustment for parents. With each new developmental stage that has a universally recognized marker of progress (e.g., going to junior high school, first date, learning to drive), parents may revisit their grief as they adapt to the realization that their child may not have the opportunity to enjoy many of these activities. Adolescence can heighten parents’ awareness of the barriers and limitations that exist for their children.49 The effective, empathetic practitioner is sensitive to the meaning of adolescence for teens and their families and acknowledges the experience and concerns that this period brings.

PUBERTY

Puberty is the term used to define the maturation of the reproductive system. During puberty, primary and secondary sex characteristics develop in conjunction with significant physical growth. This involves both biologic and psychosocial development. A complex interaction/feedback loop involving the pituitary gland, hypothalamus, and the gonads (ovaries in females and testes in males) controls the biologic development. In healthy adolescents, full sexual development may vary as much as 3 years from the average age. The average age at onset of puberty for American girls is between 8 and 13 years, with occurrence of the first period (menarche) between 12 and 13 years of age.8,81 In boys, puberty generally begins later than it does for girls, on average between 11 and 12 years of age.

Changes in the sex organs involved in reproduction (e.g., menarche in girls and the growth of penis and testicles in males) are the hallmark of puberty. In girls, race, socioeconomic status, heredity, and nutrition influence the time of menarche. Ovulation usually occurs 12 to 18 months after the onset of menarche.92 Breasts, areolar size, and adult pubic hair patterns develop over a 3- to 4-year period. This is also a period of peak growth in height, and a girl usually reaches her full height two years after she begins menstruating.

Puberty has additional challenges for adolescents already dealing with developmental and physical disabilities. Minimal information about puberty in this population is available to guide these adolescents, their caregivers, or health professionals.90 Some research suggests that in girls with moderate to severe cerebral palsy, sexual maturation begins earlier or ends much later than it does on average in the general population.114 A retrospective study involving women with autism spectrum conditions reported menarche either 8 months earlier or somewhat later than is typical (i.e., around the age of 13 years).62

In boys, development of the primary sex characteristics, such as an increase in the size of the testicles and the penis (length and circumference), coincides with overall physical growth. Changes include growth of the larynx, causing a deepening of the voice, and the ability to obtain an erection and ejaculate. First ejaculations (spermarche) occur on average between the ages of 12 and 13 years, but the seminal fluid does not contain mature sperm until later (around age 15). In this process, referred to as adrenarche, the adrenal glands are largely responsible for the secondary sex characteristic such as the growth of axillary and pubic hair, axillary perspiration, and body odor. Also, many adolescents, especially males (70% to 90%) develop acne because of the effect of testosterone.39,81

For adolescents with disabilities, puberty can present additional practical and psychosocial issues. For example, misperceptions exist about the capacity of an adolescent with a disability to be in a sexual relationship, experience sexual desire, and reproduce successfully.41 Many adolescents with disabilities report that others ignore or avoid their emerging sexuality. Consequently, they receive minimal education about contraception or sexually transmitted diseases or how their disability may affect their sexuality or reproductive.41,58 Sexual development and the individuation process can be difficult for parents, especially when the child requires extensive caregiving.58 Adults with disabilities describe the ambivalence and difficulties that their parents had in acknowledging them as sexual beings.46,104 Mary Stainton poignantly describes the demands associated with managing her menses, the emotional strain this task posed for her mother, and the decisions that denied her womanhood. In the following excerpt, she describes her mother’s response to her menses: “Frustration ripped through her as she cleaned between my legs and pulled up the Kotex pad. She felt she constantly needed to be with me when I went to the bathroom. I felt guilty for making a mess: for bleeding at all” (p. 1445).104 Her menarche was not celebrated as a coming of age as a woman; instead, she writes, “Around the time I was 12 or 13, we started talking about options. She [her mother] took me to doctors. I was put on the pill, then, given shots to stop or at least curtail my menstrual flow. A normal body process was now a huge problem, we had to control” (p. 1445).104

A meta-analysis of 36,284 adolescents in the 7th through 12th grades with visible (e.g., physical) and nonvisible (e.g., deafness) disabilities found no differences between adolescents with or without disabilities, with respect to the proportion who have had intercourse, age at first sexual experience, pregnancy, contraceptive use, or sexual orientation.108 However, a significant number of girls with invisible conditions reported a history of sexual abuse. A similar finding was reported in a study of children and adolescents with mobility impairments in which more girls with visible conditions reported a history of a sexually transmitted disease.53 The conclusion drawn in these studies is that adolescents with chronic conditions and disabilities are at least as sexually involved as other teens. However, these teens are significantly more likely to be sexually abused.

Occupational therapy practitioners working with adolescents with disabilities and chronic conditions need to be receptive to teen-initiated discussions and open to dialogue with adolescents and their parents on topics ranging from physical development, sexual expression, and contraception. Furthermore, they need to be aware of signs of sexual abuse. Information about sex education as it relates to people with disabilities can be found at websites such as www.sexualhealth.com and the National Information Center for Children and Youth with Disabilities (NICHCY).

Psychosocial Development of Puberty and Physical Maturation

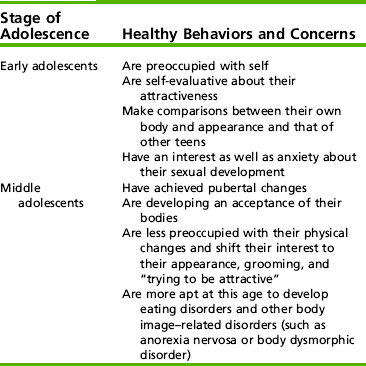

Adolescents regard the physical changes in their bodies and their emerging sexuality with a combination of anxiety and pride. These changes can cause confusion, excessive anxiety, or emotional turmoil. With changes in physical stature and the development of secondary sex characteristics, physical appearance becomes increasingly important. Sexuality and the development of relationships are critical to positive personal adjustment. Therefore, how an adolescent views his or her own physical and sexual development influences self-esteem.97 Adolescence involves integrating these significant physical and physiologic changes into a healthy self-concept that includes a positive attitude towards one’s body, referred to as body image (Table 4-1).

TABLE 4-1

Normal Development of Body Image

Modified from Radizik, M., Sherer, S., & Neinstein, L. (2002) Psychosocial development in normal adolescents. In L. S. Neinstein (Ed.), Adolescent health: A practical guide (4th ed.). Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins.

Body image, a dynamic perception of one’s body, affects the person’s emotions, thoughts, and behaviors and influences both public and intimate relationships.89 Adolescents need support to learn about their bodies and to understand that their feelings and thoughts about their bodies are universal among their peers. Such support significantly reduces the anxiety associated with physical and sexual development. Support from family and friends and the availability of information positively influence adolescents’ adjustment to their bodies’ physical and physiologic changes.

Self-esteem, self-worth, and the evaluations of others influence perceptions of and attitudes towards one’s body.22 Teenage girls pepper their conversations with remarks about their appearance (e.g., “Do you think my backside is too big in these jeans” “I’m too fat,” or “I need to lose weight”). Negative body image is associated with both low self-esteem and mental health problems, including anxiety, depression, and eating disorders such as anorexia nervosa. It is estimated that between 50% and 80% of girls, especially in early adolescence, are dissatisfied with two or more aspects of their appearance.40 Studies show that body dissatisfaction is universal. Girls, regardless of ethnicity, express a desire to be thin.70 Boys also compare their internalized perceptions of masculinity with the image they see of themselves in the mirror. This ideal body image is defined by characteristics such as height, speed, broadness of the upper body, and strength.121 Boys dissatisfied with their bodies generally want to gain weight and develop muscle mass in their upper body (i.e., shoulders, arms, and chest),35 and such desires can lead to excessive weight training and use of steroids. However, concerns about being overweight are also becoming prevalent among males.34 Research shows that, by 18 years of age, boys and girls are more satisfied with their bodies than they were in early and mid-adolescence.33

Socially constructed views of femininity and masculinity affect how a teenager develops a body image. One powerful social influence is the media (e.g., advertisements, magazines, music videos, video games, movies, and the fashion industry). The media markets a physical appearance that represents little of the diverse population of American teens. They portray an “ideal” that bears little resemblance to the “average” teen. Therefore, it is not surprising that many adolescents are critical of their bodies.15 When girls compare themselves with the media’s images of slim, perfect skin, large-breasted, small-waisted women or boys try to measure up to the lean, strong, attractive, acne-free men, they inevitability feel inadequate compared with these illusions of perfection. Furthermore, the media’s portrayal often includes proximity of equally “perfect” members of the opposite sex, and possessions such as cars and consumer goods equating attractiveness with success.22

Since the process of healthy body image development involves comparison with peers and the media’s “ideal” image, one might expect that developing a healthy body image would be even more challenging for adolescents with visible disabilities or conditions (e.g., spina bifida, cerebral palsy, Tourette’s syndrome, or congenital limb abnormalities). However, the research in this area is contradictory. Stevens et al. (1996) reported no significant differences between disabled adolescents and nondisabled adolescents in self-esteem or satisfaction with physical appearance,105 and Meeropol (1991) found that a majority of adolescents surveyed with spina bifida and cerebral palsy felt they are attractive to other people.75 However, other studies report that adolescents with physical disabilities viewed themselves as different from their peers and unattractive to others.47

Body image can also be difficult for a teen that develops a disorder or illness (e.g., cancer, diabetes, epilepsy) in adolescence; their previously healthy bodies “fail” them. Research indicates that teens who have long-term effects (e.g., impaired organ function, scars, skeletal deformities) from serious illness have a negative body image and impaired emotional functioning.14

As with physical growth and development, sexual maturation has social implications. Adolescents who outwardly appear sexually mature and seem older than their actual age can encounter demands and expectations (including sexual) that they are not psychologically equipped to navigate. Unlike boys, early-maturing girls often demonstrate lower self-esteem and poor self-concept associated with body image, and they engage in more risky behaviors (e.g., unprotected sex).112 They also experience more psychological difficulties (e.g., eating disorders and depression) than their more slowly developing girlfriends do. They are more likely to have lower grades, engage in substance abuse (alcohol, drugs), and have behavioral issues. Late maturation in boys is associated with such difficulties as inappropriate dependence and insecurity, disruptive behaviors, and substance abuse.39 Some late maturing boys find validation in academic pursuits and nonphysical competitive activities, especially those from middle and upper socioeconomic status families that value such achievements.42

Adolescents use appearance to express their individuality and/or make a statement of belonging (e.g., fashionable clothes similar to those of friends, gang colors and insignia). Since the 1990s, body piercing and tattoos have emerged as forms of self-expression among adolescents. Whatever the “body project” (e.g., clothes, jewelry, hairstyles, make-up, tattoos), these activities related to appearance are within the adolescent’s control and are consistent with practices within Western countries.12 Experimentation with appearance is healthy for most adolescents and is integral to developing self-identity. It promotes a level of satisfaction and connectedness with peers. On the other hand, adolescents with psychological difficulties may abuse their bodies by engaging in activities such as cutting, excessive piercings and tattoos, or extreme weight loss; others will adopt clothing and make-up that marginalizes them. All such actions further alienate vulnerable teens from mainstream society. Piercing and tattooing of minors is regulated in many states and thus the struggle for autonomy can be an act of rebellion, or a public display of “I own my body; I can do to it what I choose.”12

Adolescents who have a disability may depend on others for their self-care, may not have their own discretionary money from part-time work, and may lack independence in community mobility. Therefore, their opportunities to participate in activities of self-expression, experimentation, and expressing personal control are limited. For example, adolescents with disabilities are not always encouraged or offered opportunities to experiment with appearance (clothes, hairstyles) or interest that differ from those sanctioned by family and caregivers. Furthermore, it is sometimes more comfortable for parents and others to prolong childhood for these teens. Making choices about appearance and experimentation are part of the adolescent experience that contributes to self-identity, self-esteem, and healthy body image; the practitioners can find ways to facilitate experimentation for the adolescent with a disability (developmental or physical).

COGNITIVE DEVELOPMENT

Cognition is the term used to define the mental processes of construction, acquisition, and the use of knowledge, as well as perception, memory, and the use of symbolism and language.84 Advances in magnetic resonance imaging have enhanced understanding of the neurobiologic processes that enable these higher-level cognitive functions and the changes that occur in the brain during adolescence. For example, the prefrontal lobe matures later than other regions, and its development is reflected in increased abilities in abstract reasoning, as well as processing speed and response inhibition.119

Quality of thinking changes in adolescence. Piaget88 referred to this cognitive development as logical thinking (formal operations), which involves functions such as symbolic thought and hypothetical-deductive reasoning.56,121 Adolescents’ ability to think becomes more creative, complex, and efficient in both speed and adeptness. Thinking is more thorough, organized, and systematic than it was in late childhood, and problem solving and reasoning become increasingly sophisticated. In developing the capacity to think abstractly, adolescents rely less on concrete examples. Hypothetical-deductive reasoning, for example, does not require actual situations. Instead, a person identifies and explores many imagined possible outcomes to determine the most likely outcome to a particular situation or problem, as well as the relationship between present actions and future consequences. Hypothetical-deductive reasoning is essential for problem solving, and for the process of arguing. Preadolescents have difficulty considering possibilities as generalizations of actual real events, whereas the adolescent appreciates that the actual world is one of many possibilities.84

The development of cognitive abilities enables adolescents to achieve independence in thought and action.19 They develop a perspective of time and become interested in the future. Thus, cognitive development is also central to the development of personal, social, moral, and political values that denote membership in adult society. The development of moral and social reasoning is seen in the adolescent’s newly acquired ability to deal with concepts such as justice, truth, identity, and a sense of self.84

Because of this cognitive development, teens come to understand the consequences of their actions and the values influencing their decision-making. Furthermore, they become future oriented. They increasingly evaluate their behaviors and decisions in relation to the future they desire. The impulsive behaviors of a middle school or early high school student are replaced by decisions and actions that anticipate the consequences. This emerging self-regulation means that the adolescent gains the ability to control emotions and to moderate behavior appropriately relative to both situation and social cues.

Adolescents with cognitive impairments have difficulties comprehending the consequences of their actions and to moderating their behavior accordingly. Because of the lack of hypothetical-deductive reasoning, problem solving in relation to future, or responsiveness to subtleness of social cues, the self-evaluation that typically informs judgment is lacking. Instead, their impulsive decisions and actions are consistent with a cognitive level arrested at the preformal stage and their occupational performance skills are limited. Adolescents with diagnosed autism-spectrum disorders or teens with developmental disabilities whose abilities are classified in the moderate to higher functioning levels of mental retardation, and teens who have had a traumatic brain injury (TBI) may find at this stage that the academic demands of high school markedly exceed their abilities. Their peers’ increasing psychosocial maturity and independence accentuate the long-term implications of their cognitive and social disabilities. At this phase of their education, they often transition into prevocational programs and programs that will facilitate their skills for their optimal level of independence in adulthood.

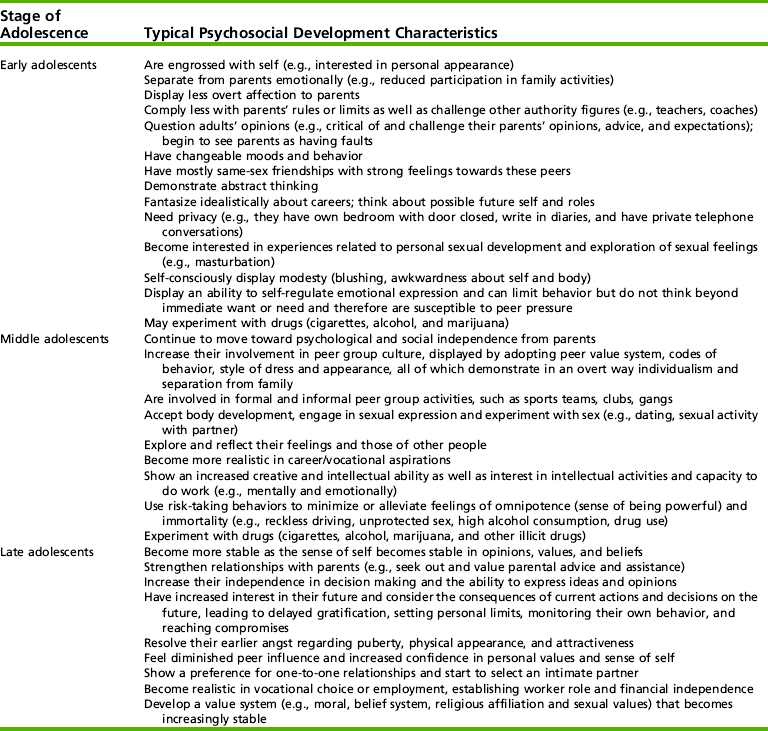

PSYCHOSOCIAL DEVELOPMENT

It is useful to view adolescent psychosocial development in three phases (Table 4-2). Phase one is early adolescence, which encompasses the middle school years between ages 10 and 13. Phase two is middle adolescence, which occurs during the high school years between ages 14 and 17. Phase three is late adolescence, 17 through 21, which is typically the first years of work or college.4,91 The middle years of adolescence are the most intense period of psychosocial development. In this phase, peers displace parents as the significant influence in the adolescent’s life. Conformity with peer groups is desirable, and the opinions of friends and peers matter.

TABLE 4-2

Summary of the Typical Characteristics of Psychosocial Development

Data from Radizik, M., Sherer, S., & Neinstein L., (2002). Psychosocial development in normal adolescents. In L. S. Neinstein (Ed.), Adolescent health care: A practical guide (4th ed.). Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; and American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry website: http://www.aacap.org/publications. Retrieved 9/7/2004.

Late adolescence is a period of consolidation. By this last phase, adolescents ideally are developing into responsible young adults who can make decisions, have a stable and consistent value system, and can successfully take on adult roles, such as an employee or a contributing member of the community. A stable, positive sense of self and self-knowledge of ability enable late adolescents and young adults to establish healthy relationships.

Difficulties navigating psychosocial development can have adverse health and social outcomes such as psychological problems (e.g., eating disorders, depression, substance abuse), and psychopathology with behavioral problems (e.g., oppositional defiance disorder, criminal activity). Psychological problems do not necessarily result in difficulties in adult life, although disorders can increase the vulnerability for further psychological and life challenges. However, some adolescent disorders, such as conduct disorder, are associated with adverse outcomes (e.g., dropping out of school, lower employment rates, substance abuse).21

The Search for Identity: Identity Formation

Society permissively tolerates a period of exploration in adolescence as the process that will result in young adults who have defined themselves as individuals, can problem-solve, take responsibility for their actions, self-regulate their emotions and behaviors, and demonstrate commitment to a set of values congruent with the social norms and values of their community.

The adolescent’s quest for self-identity is the material for films and literature and the angst that fills the lyrics of popular music.

Self-identity has two elements: an individualistic component (Who am I?) and a contextual component (Where and how do I fit in my world?).65 The individualistic sense of identity is the internalized, stable self-concept from which a person interacts with the world.72 The contextual component of self-identity allows a person to understand his/her values, beliefs, interests, and commitments to a job or career and social roles such as daughter or friend.72 The contextual aspect of a person’s identity is visible to others and is shaped by society (Box 4-2).

Erik Erikson (1980) first proposed that acquiring a sense of identity (identity formation) is a critical task of adolescence. His theory of how identity develops through recognition of one’s abilities, interests, strengths, and weaknesses by the self and others continues to dictate how identity formation is viewed in research and clinical practice.34 Erikson proposed that identity formation is the optimal outcome of a crisis resolution process in which exploration and experimentation leads to a commitment (i.e., an investment in a set of values, beliefs, interests, and an occupation) to a positive sense of identity.34 It is a complex process that involves identifying one’s spiritual and religious beliefs; intellectual, social, and political interests; and a vocational or career path. It includes relationships and gender orientation (i.e., awareness and acceptance of one’s female or male identity and sexual orientation), culture, ethnicity, and perceptions of one’s personality traits (e.g., introverted, extroverted, open, conscientious).

To achieve a sense of identity, adolescents daydream and fantasize about their real and imagined selves. These images energize and motivate. They actively attempt to make sense of their world and find meaning in what happens to them. To achieve this, they explore different roles, express a variety of opinions and preferences, make choices, and interpret their experiences. They engage in a variety of activities and lifestyles before settling on a viewpoint, set of values, or life goals. Adolescents are reflective and introspective, spending time thinking about themselves, making social comparisons between self and peers, and evaluating how others view them. They set goals, take actions, learn to resolve conflicts and problems,65 and, through this process, identify what makes them individual.

Adolescents’ behaviors, thoughts, and emotions can seem contradictory, especially between ages 13 and 15. For example, a teen might have body piercings, break parental rules, and attend school erratically, but at the same time they responsibly hold a job and dress appropriately for the work setting. Similarly, adolescents may choose healthy behaviors such as vegetarianism or sports participation, but also experiment with alcohol, drugs, and/or tobacco. Adolescents can be fickle and contrary; they may be interested in different religions and political systems, arguing passionately with their parents on political views. They express disinterest in relationships with the opposite sex, but spend the following day exclusively with a girlfriend or boyfriend.

Developmental theorist Marcia describes four states of identity: identity diffusion, moratorium, identity foreclosure, and successful identity achievement.72 Some developmental theorists claim that describing identity as “states” implies the existence of a final ideal state of identity formation, rather than the reality, which is a complex and ongoing process of negotiation, adaptation, and decision making throughout adulthood. However, describing identity states is common and can be helpful.

Identity diffusion, common in early adolescence, is a state in which a person has an ill-defined sense of identity. In this state, adolescents have little or no interest in exploring their options. They have not made any commitments to choices, interests, or values and are not interested in the question “Who am I?”9 Adolescents who continue to experience identity diffusion into their middle and late teen years have difficulty meeting the psychosocial demands of adolescence. They may demonstrate an “I don’t care” attitude of impulsivity, disorganized thinking, and immature moral reasoning.20 Identity diffusion is associated with lower self-esteem, a negative attitude, and dissatisfaction with their life, their parents’ lifestyle, and school.20,55 In this state, adolescents seldom anticipate and think about their future and have difficulties meeting day-to-day demands of life such as completing schoolwork or participating in sports or extracurricular activities. Consequently, they may be unhappy and lonely.8 In later adolescence, because they have not explored their interests or considered their strengths in relation to work, they sometimes have problems finding employment.

Moratorium is a state, common to early and middle adolescence, of actively exploring and developing a sense of identity. While in identity diffusion, adolescents avoid or ignore the task of exploring their identity; in moratorium state, identity is a project that is pursued vigorously. Teens in moratorium openly explore alternatives, striving for autonomy and a sense of individuality. However, later in adolescence, prolonged moratorium becomes problematic. Indecision about life goals, course of study, or future career can cause anxiety, self-consciousness, impulsiveness, and depression.20

Identity foreclosure is the state in which an adolescent appears to have achieved a sense of identity but has actually avoided self-exploration and experimentation by making premature decisions about career, relationships, and interests, and thereby committing to an identity.64 Adolescents demonstrating identity foreclosure commonly accept their parents’ values and beliefs and follow family expectations regarding career choices without considering other possibilities. Such adolescents are conventional in their moral reasoning, less autonomous than their peers, less flexible in their thinking regarding opinions about what is “right,” and more comfortable with a structured environment.64 Research has found foreclosure is associated with approval-seeking behaviors, avoidance of new experiences, and a high respect for authority. These teens are less self-reflective, less intimate in personal relationships, and less open to experiences than peers, but foreclosure on identity makes these adolescents less anxious than many of their peers (see Box 4-2).20

Successful achievement of a sense of identity through the healthy resolution of experimentation and exploration is coherence between a person’s identity and his/her self-expression and behaviors.64,97 It is characteristic of adolescents in later years of high school or in college or those in the work force. It follows a state of moratorium and represents commitment to interests, values, gender orientation, political views, career or job, and includes a moral stance after exploring the possibilities. Research shows that identity achievement is associated with autonomy and independence, especially in decision making.64

Adolescents who have resolved their identity issues are able to adapt and respond to personal and social demands without undue anxiety. A relatively stable sense of self gives adolescents self-esteem and efficacy in their abilities. These adolescents are less self-absorbed, less self-conscious, and less susceptible to pressure from peers. They are open and creative in their thinking and have a capacity for intimacy. They are able to self-regulate emotions, and they demonstrate mature (postconventional) moral reasoning.

Adolescents who are unable to develop a stable and distinct sense of self may have difficulties, such as a lack of confidence and lower self-esteem. As adults, they may have problems with work, establishing and maintaining intimate relationships, and meeting the responsibilities of life, such as parenting or being a contributing member of their community. Identity formation enables adolescents and young adults to integrate contradictory aspects of the self into a global self-concept, which enables them to present differently to meet different situational (contextual) demands.

The study of identity development continues to expand interdisciplinary perspectives, including the effect of external barriers and culture on adolescents’ exploration and commitment to identity.117 Occupational therapy practitioners observe identity exploration in the activities adolescents choose, the roles they take on, and the desires they express about their futures. Practitioners promote psychosocial development, including identity formation, by emotionally supporting adolescents, working with them to develop abilities in their chosen activities and roles, and offering opportunities for self-directed exploration through participation in age-related activities. Occupational therapy sessions should develop and explore work and leisure activities, promote the acquisition of social and life skills, promote participation and self-determinism, as well as address barriers to community access. In short, they should create an environment that supports identity achievement.

Sexual Orientation: Gender Identity

Sexual orientation refers to an individual’s pattern of physical and emotional arousal towards other persons of either the opposite or the same sex.37 Awareness of sexual orientation generally occurs during adolescence, a time of sexual exploration, dating, and romance. Most adolescents identify their sexual orientation as heterosexual, although about 15% of teens in mid-adolescence experience an emotional and/or sexual attraction to their own gender. Approximately 5 percent of teens will identify their sexual orientation as gay or lesbian,93 although they often delay openly identifying their sexual orientation until late adolescence or early adulthood. Reasons include a lack of support among their peers and experiences of verbal and physical harassment in high school.37,55 Openness and a willingness to discuss emerging sexuality with all adolescents is important for all practitioners working with them. Practitioners need to use gender-neutral language (e.g., partner rather than boyfriend or girlfriend; protection rather than birth control), inquire if they suspect violence in intimate relations, and provide nonjudgmental support to adolescents as they develop their sexuality and sexual orientation.37

Self-Concept and Self-Esteem

As adolescents define their identity, their self-concept (the feelings and perception of one’s identity consisting of stable values, beliefs, and abilities) becomes differentiated.92 Self-concept is multifaceted. It includes self-acceptance, which is associated with many areas of the adolescent’s life (e.g., sports and athletic competence, parent and peer relationships, academic competence, social acceptance, and physical appearance). In adolescence, self-concept develops from a self-absorbed description based on social roles and personality characteristics in early adolescence to an integrated self-concept that reflects development in cognition, moral reasoning, and social awareness.

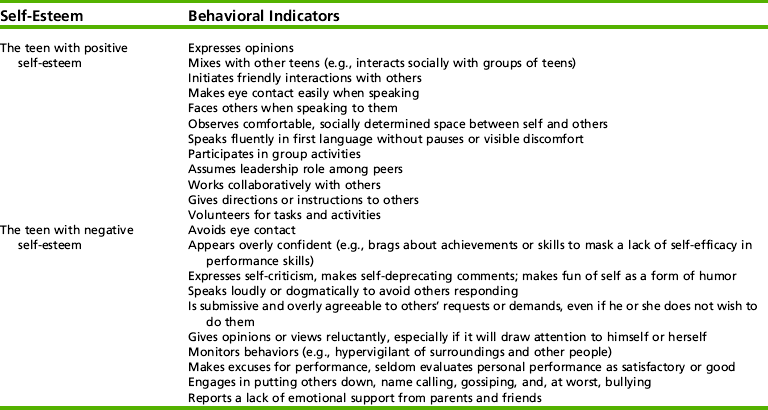

A significant aspect of self-concept is self-esteem, the global self-evaluation of values and positive and negative qualities (i.e., how a person feels about oneself). In early adolescence, self-esteem tends to decline, partly because of an increased self-awareness and a tendency to compare one’s self with the ideal and thus realize a discrepancy between one’s actual self and desired ideal self.92 However, self-esteem usually improves throughout adolescence. Table 4-3 provides an outline of the behavioral characteristics of positive and negative self-esteem throughout adolescence. Persistent low self-esteem is associated with serious psychological difficulties (e.g., depression; anxiety disorders such as social phobia, bulimia, and self-abuse). Self-abuse may take the form of cutting or harming one’s self, excessive use of alcohol and drugs, or engaging in risky behaviors such as promiscuity and unprotected sex. Behaviors such as frequently making negative self-critical statements, fears of anticipated failure, and difficulty coping with perceived failure also indicate poor self-esteem. Teens with poor self-esteem are hypersensitive to negative comments from peers and adults alike, and to lack of responsiveness or over-reaction from others, and can be defensive to constructive criticism. In a desire to belong or “fit in” by seeking social approval, they are more susceptible to peer-group influence.

TABLE 4-3

Behavioral Indicators of Self-Esteem

Modified from Santrock, J. W. (2003). Adolescence. New York: McGraw-Hill.

Factors contributing to self-esteem of adolescents with disabilities are similar to those of nondisabled teens, especially the value-laden self-assessment of one’s own attributes and limitations. A stereotypical view of adolescents with disabilities infers that self-esteem is low. However, the research data on this topic do not support this view. A meta-analysis of studies examining self-esteem in teens with minor physical disabilities reported that, compared with their nondisabled peers, they had lower self-esteem about physical competencies, but the effect on their general, social, and physical appearance self-esteem was only moderate.76 This analysis did find a relationship between the severity of physical disability and level of general self-esteem. However, Miyahara and Register found that this low self-esteem was related to misunderstanding by peers and adults and poor performance that reflected lack of effort rather than disability.77 A study of self-esteem and self-consciousness among adolescents with spina bifida found that their perception of being treated by parents in an age-appropriate manner and parents’ tolerance of social participation contributed positively to self-esteem, whereas school problems and the perceptions of disability by others contributed negatively.113 Occupational therapy practitioners who work with students who are “clumsy” or have poor motor planning or learning disabilities need to recognize these potential obstacles to positive self-esteem and incorporate strategies and experiences that validate and facilitate self-recognition of one’s strengths and abilities as part of the therapeutic process.

Adolescence and Mental Health

Mental health is defined as the “successful performance of mental functions, resulting in productive activities, fulfilling relationships with others, and the ability to change and cope with adversity.”107 Adolescents who have good mental health generally have better physical health than peers who have poor mental health; they demonstrate positive social behaviors and are less likely to participate in risky behaviors (Box 4-3).63 However, adolescents are vulnerable to mental health disorders. Most diagnosable disorders associated with altered thinking, mood, or changes in behavior causing distress and/or impaired cognitive functioning begin in adolescence, many before the age of 14. Adolescents who have mental health disorders (e.g., depression, substance abuse) are likely to have difficulties learning and developing social and life skills, and are likely to engage in risky health behaviors.

The Mental Health of Adolescents: A National Profile Report estimates that 1 in 5 adolescents experience symptoms of emotional distress and that 1 in 10 are emotionally impaired.63 The most common disorders are depression, anxiety disorders, substance use/abuse, and attention deficit disorder (with and without hyperactivity). The Youth Risk Behavior Surveillance study reported that 37% of female and 20% of male high school students answered “yes” to the question “Have you ever felt so sad or hopeless every day for two weeks in a row that you couldn’t do some of your usual activities?”17 This depression in young people (15 to 20 years of age) is often comorbid with other mental health disorders, such as addictions, anxiety disorders, and conduct disorder. Furthermore, suicide, the third leading cause of death in adolescents, is significantly associated with depression. In 2005, 8.4% of high school students attempted suicide. Although suicide attempts were more frequent among female students, especially in the ninth grade, the number of deaths from suicide among males between the ages of 10 and 14 was 2.5% higher than females and 3.5% higher in the 15- to 19-year-old age range.30

Other mental health disorders include eating disorders (e.g., anorexia nervosa or bulimia), learning disorders, and behavioral disorders (e.g., conduct disorder and oppositional defiance disorder). Schizophrenia and bipolar disorder are serious, but less common disorders. The onset of schizophrenia (excluding paranoid schizophrenia) in males is typically in late adolescence. Both schizophrenia and bipolar disorder have significant implications for teens because they disrupt participation in typical developmental activities, and these lost opportunities can contribute to lifelong disability.

Occupational therapy practitioners can assist with early identification of children and adolescents with mental health disorders because initially (e.g., in early adolescence) they may receive services for related difficulties such as learning and behavioral problems. Occupational therapy practitioners also are among the professionals involved in interdisciplinary teams providing early detection and intervention for teens with mental health disorders such as schizophrenia and bipolar disorder.

AREAS OF OCCUPATION: PERFORMANCE SKILLS AND PATTERNS

In the American Occupational Therapy Association (AOTA) Practice Framework activities that humans in engage in are categorized into domains. These are ADLs, instrumental activities of daily living (IADLs), rest and sleep, education, work, play, leisure, and social participation.1 Participation in all of these areas develops self-efficacy (confidence in one’s abilities to achieve desired outcomes), peer acceptance, and promotion of social status and self-esteem. Furthermore, adolescents are likely to adopt the values that are associated with the work, play, leisure, and social activities that they participate in.31 This section describes adolescent development and participation in four domains (work, IADL, play and leisure, and social participation).

Work: Paid Employment and Volunteer Activities

Work is a general term associated with a job (work undertaken as a means of earning money) or a career (an organized life path that often involves a formal occupation or vocation). Studies of working patterns in American teenagers report that approximately 70% of adolescents older than age 16 work while also attending school.6 Fourteen years is the age at which teens may work; however, the hours they may work are regulated. Beyond the age of 16, teens attending school cannot work more than 4 hours on a day that they attend school and are restricted on the evening hours they may work. Although working can be beneficial for adolescents, excessive working (i.e., more than 20 hours a week) for high school students can be detrimental. It is associated with emotional distress, early onset of sexual activity, and substance abuse.108 Work takes time away from schoolwork, recreational activities, social activities, and participation in sports, and it may expose teens to work-related injuries.94 Despite these adverse consequences, approximately 18% of high school students work 20 hours or more per week.83

The occupational domain of work also includes unpaid work, namely volunteerism. The 2000 edition of “America’s Children: Key National Indicators of Well-being” reported that 55% of high school students participated in volunteer activities. Community service is encouraged by schools and organizations such as sports teams and church groups. Similar to adults, the reasons teens cited for participating in volunteer activities are a desire to help others, social interaction, and recognition of contributions.99 The motivation for volunteerism is also influenced by adolescents’ personal future goals. Students with higher grade point averages and higher academic self-esteem who have plans for higher education volunteer in their communities.54

Work (both paid and unpaid) significantly contributes to healthy adolescent development. In work settings, adolescents interact with adults on a more equal level, have opportunities to assume responsibilities and learn social behaviors, shape values, and develop knowledge of their possible preferences for adult career/work.61 Participating in paid employment and volunteerism also develops life and social skills beyond the work environment, such as managing money, organizing time, developing routines, developing skills in collaboration, and negotiating relationships with other people. It also provides opportunities to learn from and communicate with more diverse social and racial groups than their family and school contexts.94 The disposable income earned from paid employment gives some adolescents discretionary spending and a sense of economic independence, whereas others need to work to support themselves financially or contribute to their families. Whatever the circumstances, work helps adolescents assume adult-like responsibilities.

Occupational therapy programs for adolescents focus on strategies that develop work skills and behaviors that will assist in their transition from school to work. These skills and behaviors constitute the performance dimension of work required for adult employment. In addition to these skills and behaviors, another significant aspect of engaging in work is the development of an occupational identity.

Occupational identity combines interests, values, and abilities into a realistic choice of a job or career path. It begins in early adolescence with the development of abstract thinking and a capacity for future-oriented thinking. Adolescents start to fantasize about their future work occupations. Initially, these daydreams are idealistic aspirations about a possible adult self. By mid-adolescence, such fantasies become more realistic, and by late adolescence, their aspirations have a realism based on interests, values, and a match between their performance abilities and actual job demands. Pursuing postsecondary education (college or university) delays the transition to full-time work, and settling on an occupational identity may be deferred. Professional academic programs of study that begin with undergraduate degrees (e.g., nursing, occupational therapy, and engineering) proactively facilitate and shape occupational identity generally earlier than postsecondary degrees in the science or liberal arts.

In summary, full-time employment is a tangible marker of the transition from adolescent to adult. The worker role with the accompanying financial independence replaces the student role. The successful transition to the worker role involves a choice of occupation that integrates personal identity and interests with individual occupational performance skills and job requirements. Hence, occupational therapy programs start to explore occupational identity early in adolescence and combine this process with skill development, ensuring future work options.

Work Opportunities for Adolescents with Disabilities

Opportunities for inclusion in paid employment have increased for teens with disabilities. Hence, the transition from school to work is frequently the focus of occupational therapy. These transition programs are most effective when based on students’ strengths, interests, and needs. Successful work experiences for teens with disabilities are contingent on strong social networks, formal and informal support within the work setting, support of supervisors, and a workplace culture that positively supports inclusion and diversity in hiring practices.13

Instrumental Activities of Daily Living

IADLs support daily life within the home and the community and, although the tasks can appear mundane, competency in the performance skills associated with everyday living is essential. Developing independence and interdependence in IADLs establishes the foundation of physical and financial independence.

Adolescents take on more responsibility for IADLs; for example, the chores and simple routines of childhood increase from cleaning one’s room to tasks that contribute to the household (e.g., mowing lawns, doing laundry, cleaning the car, cooking). As autonomy increases, teens gain experience with most IADLs. They learn to drive and/or use public transport so they can move about the community without adult supervision. Although still receiving parental oversight, they take on their own health management, such as taking medications, learning about health risks, and making decisions about health behaviors (e.g., smoking, having protected sex, nutrition, and personal hygiene routines). They learn money management associated with IADLs, such as shopping, planning how and when to spend money, saving for the future, and managing a credit card and bank account.

By middle adolescence, teens may also take on responsibilities of caring for children by babysitting and assisting with coaching or lifeguarding. With these tasks, they develop a knowledge and awareness of safety and emergency procedures. These roles and associated responsibilities further extend their repertoire of skills. Positive role models such as adult family members and other significant adults facilitate the gradual development of multiple and complex IADLs.

Adolescents initiate communication and use a wide variety of communication technologies to interact with peers. Eighty-seven percent of adolescents between the ages of 12 and 17 interact through online social networks.68 Consequently, they have almost 24-hour connection with peers through text messaging, cell phones, instant messaging, and increased contact with adults such as teachers and coaches via email. This is particularly true of girls, and their contact increases with age. These social networks are equally available to teens with and without disabilities. Adolescents’ use of the Internet has intensified and broadened: they log on more often and do more things when they are online. They shop online, play games, and research information for school assignments. Girls dominate most content-created online by teens; 35% of girls blog, whereas only 20% of boys blog; 54% of girls post photos compared with 40% of boys; but more boys post video content.69 In a Canadian study, adolescents’ reported use of technologies could be seen as a continuum from highly interactive to fixed information sources that fell within one of four domains. These were personal communication (telephone, cell phone, and pager), social communication (e-mail, instant messaging, chat, and bulletin boards), interactive environments (websites, search engines, and computers), and unidirectional sources (television, radio, and print).102 Consequently, teens have access to a vast amount of information and connect with people beyond their known social network and geographic location.

The enjoyment of creating and social networking on sites such as Myspace and Facebook is tempered with risks. Teens are making moral decisions about the information accessed and people interacted with, often outside of parental/adult oversight. Discerning use of technology integrates cognitive skills, values and interests, and knowledge of the need to protect personal identity and privacy, all at an age when risk taking is more likely, the anticipation of consequences is underdeveloped, and problem-solving skills are inconsistent. The Internet and communication technologies, which provide a complex virtual, social, and physical world for children and adolescents, are increasingly becoming an area of research in child and adolescent development.43 The future of this research will expand the understanding of how these technologies influence and facilitate cognitive, psychological and social development.

Achieving Competencies in IADLs with a Disability

Adolescents with disabilities and their families face an array of challenges in the area of IADLs. They deal with the paradox of achieving emotional and psychological independence and developing identity as a self-determining individual (which in society is represented overtly by work and autonomy in IADLs) while still physically dependent on their parents or caregivers. These teens may always require the assistance or oversight of other people for many IADLs. Although teens with developmental delays eventually learn skills to optimize their autonomy, most have semi-dependent relationships with their care providers, who will make executive life decisions with them. However, it is a different scenario for cognitively able teens with physical disabilities. To enter adult life, these teens must learn to apply their executive cognitive skills and emotional self-regulation to IADLs. They need opportunities to develop decision-making and problem-solving skills applicable to IADLs such as health management, money management, and community access (maybe driving an adapted vehicle), all decisions previously undertaken by parents. They need these experiences because eventually as adults they will instruct and oversee attendant caregivers. Thus it is the responsibility of the adults in their lives (occupational therapy practitioners, family members, and other caregivers) to augment this learning. As caregivers gradually transfer such responsibilities to the teens, they are simultaneously changing their roles in relation to their children.

Parents as primary caregivers have different demands and new emotional strains as their child enters adolescence. Similar to parents of nondisabled teens, they are seeking the balance of “letting go” while still being supportive. Yet they and their adolescent are dealing with many additional life challenges that are psychologically and socially demanding. This transition is difficult for parents, and retrospective studies report that adults with disabilities say that, as adolescents, their parents tended to be overprotective.79

Although adolescents with physical and developmental disabilities may struggle to become autonomous self-determining individuals, at-risk, emotionally troubled teens often find themselves prematurely independent. Although they still need the support and nurturing of a stable family, these teens, because of personal and socioeconomic circumstances, have a pseudo independence that they are not developmentally ready to manage. They may lack adequate cognitive development and performance skills to meet their IADL and ADL needs. Sometimes, they are even caregivers of their own children. Adolescents in such circumstances often deal with issues such as violence, poverty, homelessness, school failure, and discrimination, while struggling through normal developmental processes.119

Leisure and Play

Leisure and play activities are the discretionary, spontaneous, and organized activities that provide enjoyment, entertainment, or diversion in social environments that may be different to school and work settings.86,115 These activities account for more than 50% of American adolescents’ waking hours.66 In an occupational therapy study, teens reported that leisure provided enjoyment, freedom of choice, and “time-out.”87 The use of this free time may seem like “time-out,” but it can have a significant role in development. In this free time, teens can explore and engage in new behaviors and roles, be exposed to different interests, establish likes and dislikes, and socialize with an array of social groups, thereby developing skills, patterns of behavior, and self-identity.

Unstructured use of time, in particular passive activities such as watching television and playing computer games, have few positive benefits. The main criticism of passive activities is that they contribute to boredom, which is associated with a greater risk of dropping out of school, drug use, and antisocial/delinquent activities.111 Alternatively, constructive use of nonschool hours in nonacademic extracurricular and leisure activities such as sports is linked with positive adolescent health and well-being and development of physical, intellectual, and social skills.32 These extracurricular school programs (e.g., sport teams, school band or orchestra, drama club) and community-based activities such as scouts, music, or dance classes typically include goal-directed activities as well as a sense of belonging to a peer group (Figure 4-2).

An additional benefit of these activities is relationships with nonfamilial adults. Positive interactions with coaches, adult leaders, and teachers facilitate problem solving, provide social support (sometimes compensating for a lack of parental validation and support), increase teens’ self-esteem, and promote skill acquisition and competency.32 Participation in these extracurricular activities is also associated with higher academic performance and occupational achievement such as the likelihood of attending college.10 Male students with lower academic achievement and/or those from lower socioeconomic backgrounds who play sports are more likely to finish high school, be involved in the community, and have better interpersonal skills. They also have lower rates of alcohol and drug use or antisocial behaviors.32,45,73

An area of concern is the decline of physical extracurricular and leisure activities, which is linked to an increased risk for poor health among adolescents, including obesity and chronic health conditions such as diabetes.57 The national public health initiatives to promote adolescents’ participation in physical extracurricular and leisure activities, which have not been successful, have significant implications. Adolescent physical leisure activity patterns predict adult physical activity levels.110 Males are more likely to continue to participate in and have a positive attitude toward physical activities than females, perhaps because of the relationship between masculinity and vigorous sport, competition, and sports achievement.110 The stereotypes of bodily contact, face-to-face opposition, and endurance associated with male sports, and aesthetics or gracefulness with female sports, may explain why some girls drop out of sports and physical activities47 and why girls are more likely to participate in dance and gymnastics, which do not compromise their femininity. Although stereotypes and other influences such as parents and teachers influence participation in physical activity, the strongest influence is peer participation.110

Choosing popular adolescent activities that are transferable beyond the context of occupational therapy develops performance skills and facilitates social behaviors that enhance self-efficacy and autonomy. The outcome of developing leisure skills in occupational therapy can be successful participation in peer activities and increased social inclusion. Having the skills to engage successfully in leisure activities contributes to healthy and perceived quality of life by providing a social network, enjoyment, and constructive use of time. Long-term improvement in performance in leisure skills can have additional value, especially for adolescents who may not gain employment.

Social Participation

Social activities, friendships, and the behaviors associated with these activities and roles that characterize and define individuals within society are salient to adolescents’ development of social participation. Social roles and relationships are explored and developed by engaging in a variety of social activities, especially peer group activities.87 In middle and high school, teens strive to “fit in” and make friends. Peer-focused social interactions and relationships formed in school through leisure activities provide social status and develop adolescents’ social identity.50 This emerging identity may differ from the teen’s identity in his or her family. The changes represent moving from family members as the primary source of emotional and social support to a reliance on friends, peers, and nonfamily adults.7,50

Peer Relationships

Having friends significantly contributes to social and emotional adjustment in adolescents.118,120 Peer relationships offer social integration and a sense of belonging or acceptance. Initially, these relationships develop around cliques, which are small, cohesive groups of teens that have a somewhat flexible membership, meet personal needs, and share common activities. Participation in peer cliques provides a normative reference for comparison with peers and influences adolescents’ developing social attitudes and behaviors, as well as their academic adjustment.7 Making the shift from middle school to high school can be easier with membership in supportive and peer-recognized cliques. Initially, in early and middle adolescence, membership in cliques develops spontaneously around common interests, school activities, or even neighborhood affiliations. In junior high, cliques are usually same sex; by middle to late adolescence, these groups expand to include the opposite sex. In late adolescence, cliques weaken, and they are replaced by loose associations between groups that consist of couples.50 Lack of participation in peer groups or exclusion from cliques comes with a cost (e.g., a sense of rejection, a lack of opportunity to participate in peer activities, social isolation, a lack of social status). Adolescents who do not find their niche in cliques are more likely to be depressed and lonely and have other psychological problems.19 Exclusion from cliques and the resulting lack of choices are suggested as the reason some adolescents join less constructive peer groups such as gangs or groups who engage in illegal and/or antisocial activities.

Most adolescents also have lasting stable friendships that differ from the relationships within cliques. Initially, they are same-sex friendships that develop around sharing activities and a closeness of mutual understanding. They can be emotionally intense, involve openness and shared confidences, and depend less on social acceptance; however, these same-sex friendships also imply a heightened vulnerability.19 Girls’ friendships are interdependent and reflect a preference of intimacy, whereas boys’ friendships are congenial relationships established around shared interests such as sports, music, or computer games. These friendships evolve with social and cognitive development. In middle adolescence, the basis of friendships is shared loyalty and an exchange of ideas; in the latter years, friendships progress to incorporate autonomy and interdependence, and as intimate relationships develop in late adolescence, the salience of these friendships lessens.

Navigating Social Participation with a Disability

Because teens strive for conformity and identification with their peers, making and maintaining friendships can be particularly difficult for teens with disabilities (Case Study 4-2). The data on the social life of adolescents with disabilities provide contradictory information. A national Canadian study found that adolescents with physical disabilities reported good self-esteem, strong family relationships, and positive attitudes toward school, teachers, and many close friends.105 However, other studies have found that because teens with disabilities lack the “qualities” that bestow social status among adolescents (e.g., excellence in sports or physical attractiveness), they often are not included socially in peer groups.106 Teens with disabilities have reported more loneliness, participation in fewer social activities, fewer intimate relationships, and more social isolation than their peers without disabilities report.29,106 Even teens with good social relationships in school have less contact with friends outside the school setting than their peers without disabilities.38,105 Factors that affect social acceptance of teens with physical disabilities include role marginalization (lacking a clear role and the inability to undertake the tasks of typical adolescent roles), lower social achievement, and limited contact with peers.78 Adolescents without disabilities consider their peers with physical disabilities as less socially attractive and report that they are less likely to interact with them in social settings.38 An asset for teens with disabilities is academic achievement, because high academic achievement is shown to promote better social acceptance.78