Feeding Intervention

1 Describe the acquisition of feeding, eating, and swallowing skills as developmental milestones.

2 Describe the anatomic landmarks and four phases of swallowing or deglutition.

3 Outline the cranial nerves involved in feeding and swallowing.

4 Explain the components of a feeding, eating, and swallowing evaluation.

5 Assess feeding difficulties in children within the larger context of the family’s cultural, social, and behavioral routines around food and mealtimes.

6 Classify common abnormalities and disorders related to the phases of swallowing.

7 Identify factors that may warrant further evaluation, including a videofluoroscopic swallow study.

8 Describe additional diagnostic and medical testing that may be used in a comprehensive evaluation.

9 Understand the developmental and psychosocial implications for a child whose nutritional intake is altered.

10 Identify medical, developmental, behavioral, and social issues that contribute to feeding, eating, and swallowing problems.

11 Explain the team approach to evaluating and treating the child from a biopsychosocial perspective.

12 Describe intervention strategies for feeding, eating, and swallowing deficits.

FEEDING: DEFINITION AND OVERVIEW

The process of feeding, eating, and swallowing is critical for health and wellness and plays an integral part in the child’s social, emotional, and cultural maturation. At the most basic level, the process of taking in adequate nutrition is essential for normal growth and development.

Throughout childhood, from infancy and all the way through adolescence, dietary requirements are constantly changing. At the same time, a child’s development gradually moves from complete dependence toward independent self-feeding. This dynamic process depends on the acquisition of both complex oral motor and fine motor skills. Indeed, mealtimes allow a child to explore new tastes and textures, while at the same time encouraging the development of motor skills through finger feeding and the use of utensils. Equally important, the feeding process is marked by social contact with other children, parents, and family and is thus essential for development of social interaction skills in the child. Children learn to communicate needs and desires through verbal and nonverbal cues. Feeding is one of the earliest instances in a child’s life where he or she learns to signal hunger, satiety, and thirst among other needs and desires. Finally, because this complex process is shaped by cultural and social norms, it often lays the foundation for the acquisition of certain customs and rules of sociocultural behavior.

Feeding—sometimes called self-feeding—is defined as the process of setting up, arranging, and bringing food from the plate or cup to the mouth. Eating is the ability to keep and manipulate food or fluid in the mouth and swallow it. Swallowing is a complex act in which food, fluid, medication, or saliva is moved from the mouth through the pharynx and the esophagus, and into the stomach.4

Children develop problems with feeding, eating, and swallowing as a result of medical, oral, sensorimotor, and behavioral factors, either alone or in combination.55 Medical conditions include prematurity, neuromuscular abnormalities, structural anomalies, gastroesophageal diseases, food allergies, and tracheostomy. Children with developmental disabilities may fail to meet basic nutritional needs because of delayed or deficit oral motor and self-feeding skills. Oral motor dysfunction causing poor nutrition is strongly associated with poor growth and adverse health outcomes.27,63 Clinical findings may include food refusal/selectivity, vomiting, swallowing difficulty, prolonged mealtimes, poor weight gain, and failure to thrive.

Behavioral problems are very common in children with feeding disorders. Food refusal and/or food selectivity can often signal negative interaction between children and their caregivers. However, they may be, and often are, secondary to underlying medical causes such as reflux or food allergy. In fact, both medical and behavioral etiologic factors are often present, making definitive diagnosis difficult.

The Role of the Occupational Therapist

Of all the activities of daily living, none is more life-sustaining than eating. Occupational therapists and occupational therapy assistants have long played an integral role in providing essential services and comprehensive management to children who have problems with one or more aspects of the feeding process. A competent occupational therapist should therefore be familiar with the following:

• Basic anatomy and physiology

• Growth and developmental milestones

Some occupational therapists work in specialized facilities as part of a multidisciplinary team that often consists of pediatric specialists, including gastroenterologists, developmental pediatricians, allergists, otolaryngologists (also known as ENTs), nurse practitioners, nutritionists, speech–language pathologists, behavioral psychologists, and social workers, all of whom work in tandem to evaluate and manage complex cases. However, many therapists work in school settings or as solo practitioners and are often the first to detect a child’s difficulties with feeding. In either instance, the occupational therapist has a well-defined, unique role in the assessment and management of feeding, eating, and swallowing disorders.

THE MEALTIME: AN OVERVIEW

Mealtime is generally a family time that provides physical, cognitive, and emotional nourishment of all members. Meals arrange the day temporally, organizing it into periods and signaling that certain activities end and new ones begin. Mealtimes provide a routine and a structure and offer a time for relaxation, communication, and socialization. At mealtimes, parents and children communicate symbolically and emotionally while at the same time satisfying very basic needs.22 Many believe that to nourish a child is to nurture a child. Thus, mealtimes are cultural rituals and, as such, an integral part of a family’s life, a time for bonding and sharing.

Caregivers and children engage in both shared and individual roles during mealtimes. Usually, the child is expected to remain seated, to attend to the caregiver, to feed himself or herself, to communicate with others at the table, and, generally, to follow the table manners and routines. The caregiver is expected to provide food in quantities sufficient to satisfy hunger, to assist in feeding younger children, to communicate and interact with other family members, and to establish mealtime norms and routines.

A child’s mealtime participation changes as he or she goes through the different stages of growth and development, from infancy to adulthood. During infancy, the parents are responsible for feeding or assisting the child. During the preschool and school-age years, the parents’ role shifts toward oversight, communication, and discipline. Almost all parents try to create a pleasant and relaxing family atmosphere during meals. This could be challenging and not always easy to achieve if a child has a disability that affects eating performance. The child’s temperament, health, and disposition and the parent’s health and mood are all important factors contributing to mealtime social interactions.

Contextual Influences on Mealtime

Family composition determines who is present at mealtime. The child may be fed in an isolated setting alone with his mother or may sit with all family members around the dinner table. Large families may have chaotic or noisy mealtimes. Such an environment creates difficulties for a child with hypersensitivities or high sensory arousal. Caregivers may not notice that a child has poor intake when many are present at the dinner table. On the flipside, large families have extra hands to assist in a child’s feeding if needed. Sometimes, children who need a quieter environment or who need maximal assistance are fed separately before or after the other family members. Sometimes only one family member can feed the child successfully. When a child has only one feeder, the responsibility for feeding around the clock can, over time, become stressful and exhausting for the feeder.

In some cultures, children are fed by a caregiver throughout the preschool years, whereas in others, infants are encouraged to self-feed despite the ensuing mess. For example, Puerto Rican mothers may continue to feed their children well into their preschool years, whereas Anglo mothers encourage self-feeding much earlier. Puerto Rican mothers who feed their children as toddlers generally emphasize respectful relations and appropriate interpersonal relationships during the meal. In contrast, Anglo mothers who allow self-feeding at 12 months of age tend to emphasize the young child’s independence and autonomy.59 Cultural beliefs also determine the amount and type of food that parents believe their children should eat. For example, southern African American children are often given sweetened tea to supplement their diet, because parents believe that tea enhances the physical and cognitive abilities of a child.41 The tea, however, may replace other drinks (e.g., milk) that have more vitamins and nutrients.

A family’s socioeconomic status also has an impact on mealtime and feeding patterns. Families in poverty may be unable to provide sufficient food or may eat cheaper foods that tend to be high in carbohydrates and fat. A parent’s educational level, which is often related to socioeconomic status, can affect a child’s diet because an undereducated parent may lack knowledge of basic nutrition. Obesity and hunger coexist in high-poverty areas. Diets of low-income consumers may be high in sugars and fat because they are the cheapest source of nutrition.

According to the results of the annual survey of the U.S. Census Bureau, those at greatest risk of being hungry live in households that are headed by a single woman; that are Hispanic or Black; or with incomes below the poverty line. Overall, households with children have food insecurity at almost double the rate for households without children. According to survey undertaken by the U.S. Department of Agriculture in 2006, 35.5 million persons are food insecure, of which 12.6 million are children.24 Food insecurity refers to the lack of access to enough food to fully meet basic needs at all times because of a lack of financial resources.47 UNICEF defines undernutrition as being underweight for age, too short for age (stunted growth), dangerously thin for height (wasted), and deficient in vitamins and minerals.66

A single parent may be under greater stress and may not be able to provide structured mealtimes, causing the child to have chaotic mealtime patterns. In the absence of mealtime structure, the child may graze throughout the day whenever hungry, eating whatever is easily available. Adolescent parents may not have access to information on child development and feeding and may feed their young children inappropriate foods or foods with poor nutritional value.

Feeding and mealtime patterns vary from family to family, and factors beyond the ones described above may be at play. Interviewing parents about the degree of flexibility they allow a child who refuses to eat, Humphry and Thigpen-Beck found that older, better-educated parents were more likely to be flexible.36 Parents who placed emphasis on discipline and obedience were less likely to be flexible with a child’s refusal to eat. Clearly, social context can be helpful in understanding a family’s feeding strategy and how parents interpret and respond to a child’s mealtime behavior.37

Personal Influences on Mealtime

A caregiver’s personality traits and other individual factors can also shape mealtime and affect a child’s ability to feed. When the caregiver does not enjoy feeding a child or approaches it as a chore, the task can lose much of its meaning, changing the mealtime experience for both the adult and the child. For example, some caregivers are anxious about feeding and tend to be controlling when the child is a poor eater. The caregiver may have preconceived ideas about how much the child should eat and force food on the child or become disappointed with the child’s intake. A controlling parent may find that the child desires control of what he or she eats, and a battle of the wills may result.

Personal/individual factors that influence mealtime include the child’s health, eating skills, and communication/interaction skills. Children with feeding/eating problems can require extra time, special food preparation, adaptive equipment, and a structured protocol for the caregiver. This chapter discusses some health problems and delayed or deficient oral motor skills that can affect feeding. Occupational therapists are often called on to provide intervention in such circumstances.

DEVELOPMENTAL SEQUENCE OF MEALTIME PARTICIPATION

Progression of Mealtime Participation

In the first 6 months of life, parents feed their infant in their arms. Feeding is a time for bonding, characterized by close holding and warmth, eye contact, and nonverbal communication between the parents (or other primary caregivers) and the child. A typical interaction between child and parent may be the parent’s stroking and touching the infant, who responds by grasping the mother’s breast or hair or the father’s shirt or fingers. Although the parent determines what the infant eats, it is the infant who typically sets the pace, duration, and end of a meal. When this interaction is less than smooth, the parent may compensate by trying to exercise more control. Positive early mealtime experiences solidify the bond between parent and child and strengthen the relationship between them.

An infant becomes more independent between 7 and 24 months. For example, a 7-month-old infant can usually finger feed. By 18 months, the child is typically attempting to use a spoon and a cup. As independence grows, so do the chaos and messiness of mealtimes. Although the parent continues to select the foods for the child, the child can now choose whether to eat or refuse the food. During this time, the toddler gets a greater variety of foods. The child moves out of the parents’ arms and into a high chair or a booster seat. The toddler studies his or her foods and truly enjoys making a mess. Most toddlers explore the sensory qualities of foods, such as texture, with their hands and tongues. Parents encourage their child’s efforts at self-feeding and allow him or her to try different foods, while ensuring they limit those difficult to chew and/or digest. Eating, however, continues to be time for communication, by now both verbal and nonverbal. Parents begin to describe the child’s foods and thus provide a source for new vocabulary. In fact, words denoting food are often among the first words acquired by many toddlers.

Once the child is about 2 years old and is feeding relatively independently, he or she usually becomes a full participant in family mealtime. The child sits at the table, where she or he can observe and mimic the actions and behaviors of fellow meal participants. By preschool, children begin to eat some or all of the foods that other family members are eating. Family members become models for appropriate feeding behaviors and instruct the child in the basics of self-feeding. For most preschool children, mealtimes are enjoyable social times, marked by a sense of togetherness and an altogether positive, relaxing environment. Disability, however, can have a negative effect on mealtimes and hinder or slow the progression and accomplishment of these outcomes. Too much pressure on preschoolers to eat more, eat neatly, or eat certain foods may create anxiety about eating and may be harmful in the long run by making eating a less than enjoyable physical, sensory, and social activity.

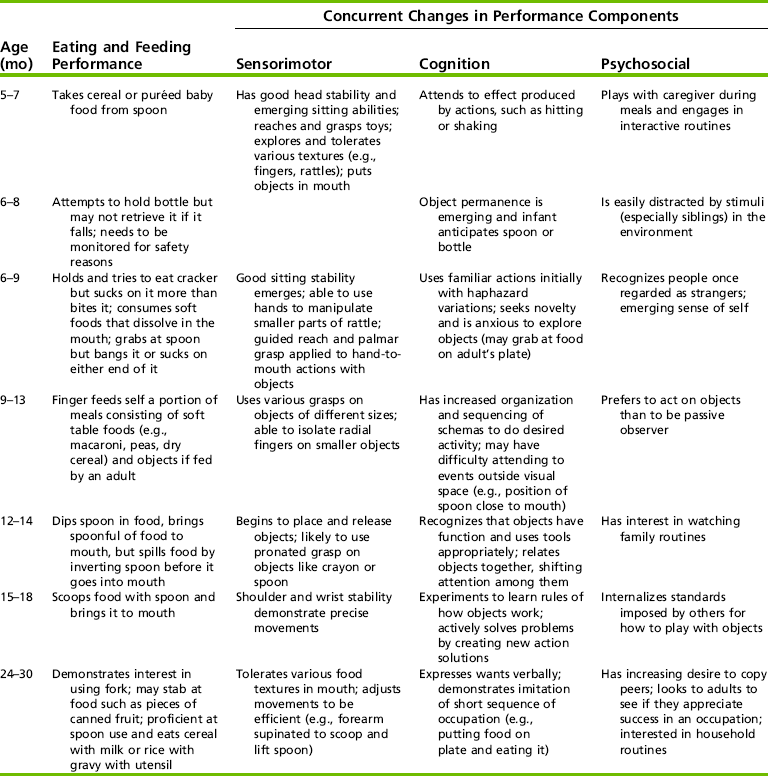

Development of Oral Structures

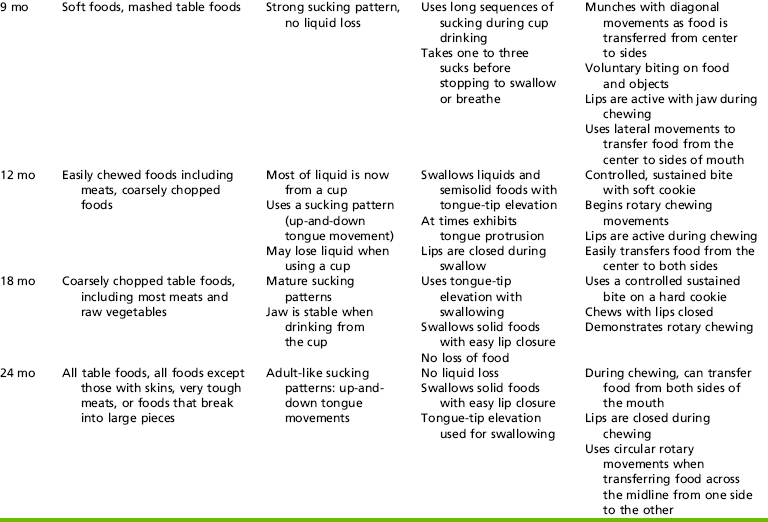

Intact oral structures and cranial nerves are prerequisites for normal eating and drinking. Various aspects of oral motor development emerge as the child begins to control jaw, tongue, cheek, and lip movement. The anatomic structures of the mouth and throat change significantly during the first 12 months. The growth and development of the oral structures allow for increasingly mature feeding patterns. Table 15-1 lists the oral structures involved in feeding.

TABLE 15-1

Functions of Oral Structures in Feeding

| Structure | Parts | Function during Feeding |

| Oral cavity | Hard and soft palate, tongue, fat pads of cheeks, upper and lower jaws, and teeth | Contains the food during drinking and chewing and provides for initial mastication before swallowing |

| Pharynx | Base of tongue, buccinator, oropharynx, tendons, and hyoid bone | Funnels food into the esophagus and allows food and air to share space; the pharynx is a space common to both functions |

| Larynx | Epiglottis and false and true vocal folds | Valve to the trachea that closes during swallowing |

| Trachea | Tube below the larynx supported by cartilaginous rings | Allows air to flow into bronchi and lungs |

| Esophagus | Thin and muscular esophagus | Carries food from the pharynx, through the diaphragm, and into the stomach; it is collapsed at rest and distends as food passes through it |

Modified from Wolf, L. S., & Glass, R. P. (1992). Feeding and swallowing disorders in infancy: Assessment and management. Tucson, AZ: Therapy Skill Builders.

The newborn has a small oral cavity filled with fat pads inside the cheeks and the tongue. The small and tight oral cavity allows the child to grasp and easily compress the nipple during breast-feeding and to achieve automatic suction. The negative pressure caused by the sucking movements of the jaw extracts liquid from the nipple.44 Thus, a full-term healthy newborn can suck easily and successfully from a breast or bottle nipple.

The structures in an infant’s throat are also in close proximity to one another. The epiglottis and soft palate are in direct approximation. As a result, the liquid from the nipple safely passes from the base of the tongue to the esophagus. During swallowing, the larynx elevates and the epiglottis falls over it to protect the trachea. Therefore, aspiration is less likely before 4 months of age, and the infant can safely feed in a reclined position.

As the infant grows, the neck elongates, and the configuration of the oral and throat structures changes. The oral cavity becomes larger and more open, the tongue becomes thinner and more muscular, and the cheeks lose much of their fatty padding. With the increase in oral cavity space, the tongue, lips, and cheeks provide greater control of liquid and food within the mouth. New sucking patterns develop enabling the infant to handle liquid without the structural advantages of early infancy. These include up-and-down movements of the tongue to extract liquid from the nipple. The increasing oral space also provides room to advance food texture and to move the tongue in the rotary pattern required during chewing.69

As the infant approaches 12 months of age, the hyoid, epiglottis, and larynx descend, creating space between these structures and the base of the tongue. The hyoid and larynx become more mobile during swallowing, elevating with each swallow. The greater complexity of the suck-swallow-breathe sequence leads to greater coordination among these structures. The elongated pharynx increases the risk of aspiration during feeding in reclined position as the pull of gravity accelerates the flow of liquid into the entrance of the esophagus. Figure 15-1 shows the structures of the mouth and pharynx of the infant.

Phases of Swallowing

There are four defined phases of swallowing. The oral preparatory phase is under voluntary control and the area of oral motor/feeding intervention. Oral manipulation using the jaw, lips, tongue, teeth, cheeks, and palate results in the formation of a bolus. The amount of time varies depending on the texture of food/liquid. The trigeminal (V), facial, (VII), glossopharyngeal (IX), and hypoglossal (XII) cranial nerves are listed in Box 15-1.

The second phase is the oral phase, also under voluntary control. This phase begins when the tongue elevates against the alveolar ridge moving the bolus posteriorly and ends with the onset of the pharyngeal swallow lasting for 1 to 3 seconds. The third phase is the pharyngeal phase, also lasting 1 to 3 seconds, which starts with the trigger of the swallow at the anterior faucial arches. The hyoid and larynx move upward and anteriorly, and the epiglottis retroflexes to protect the opening of the airway. It ends with the opening/relaxation of the cricopharyngeal sphincter. The final phase is the esophageal, which, along with the pharyngeal phase, is not under voluntary control. It starts with the contraction of the cricopharyngeus muscle and ends with relaxation of the lower esophageal sphincter, allowing food to enter the stomach. The duration is 8 to 10 seconds.

ORAL MOTOR DEVELOPMENT ASSOCIATED WITH EATING SKILLS

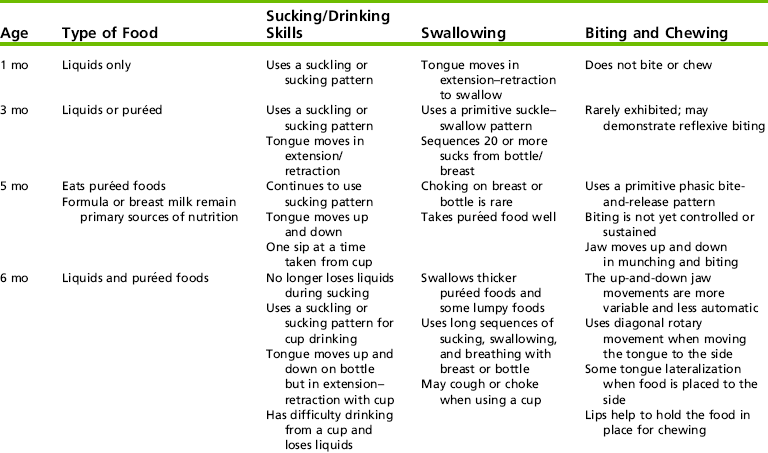

Sucking, drinking, biting, and chewing are closely linked to the child’s overall motor development. Oral patterns evolve along with the child’s changing nutritional needs, growing desire for self-feeding, and increasingly greater ability to communicate.7 Table 15-2 summarizes the sequence of eating skills development.

TABLE 15-2

Developmental Sequence of Eating Skills

Ages are approximate and may vary among infants.

Adapted from Glass, R., & Wolf, L. (1998). Feeding and oral motor skills. In J. Case-Smith (Ed.), Pediatric occupational therapy and early intervention. Boston: Butterworth Heinemann; Morris, S. E., & Klein, M. (2000). Prefeeding skills (2nd ed.). San Antonio, TX: Therapy Skill Builders.

Coordination of Sucking, Swallowing, and Breathing

The sucking reflex is present in the fetus and is the predominant method of feeding during the first 8 to 10 months of life. Sucking can be either nonnutritive or nutritive, and each one is different. Nonnutritive sucking, the goal of which is not to feed but rather to calm, occurs when a child is sucking on a pacifier. It is marked by rapid, rhythmic movements, occurring at a speed of about two sucks per second. By contrast, the nutritive pattern occurs when a child is sucking on a source of nutrition, such a bottle nipple. It is rhythmic, but its rhythm is marked by alternating bursts with pauses, which allows the infant to breathe and rest between sucking bursts.

Premature infants of 33 weeks’ gestational age or less are typically fed by nonoral methods such as an intravenous line or a nasogastric tube. The reason for this is that infants younger than 33 weeks, although capable of rhythmic nonnutritive sucking, have insufficient strength and endurance for nipple feeding. A 35-week-old healthy premature baby typically has sufficiently strong jaw and tongue movements to be fed orally, at least part of the time.

Two important factors that determine the ability to feed are sucking rhythm and type of suction (i.e., negative pressure for expression of liquid) that the infant achieves and sustains over time.21 Both compression and suction are required for the expression of liquid.69

To achieve suction and compression, the infant seals his or her lips around the nipple and simultaneously moves the tongue back and forth and up and down. By 36 weeks of gestational age, most premature infants can take all food by mouth and are able to suck nearly as well as a full-term infant.

The full-term infant (37 to 42 weeks’ gestation) has strong oral reflexes that enable him or her to take in liquid nutrition without difficulty. Exposed to tactile stimulation near the mouth (such as gentle touching of the lips), the hungry infant reacts by turning the head (rooting reflex), which permits him or her to latch onto any potential source of nutrition. The infant also exhibits gag and cough reflexes to prevent liquid from entering the airway.

The amount of liquid consumed during a meal is determined by three factors: rate or speed of sucking, force of suction or compression, and length of feeding time. Thus, infants who suck faster and pull more forcefully on the nipple and take in more fluid may finish eating in less time than those who suck more slowly or weakly. The sucking pattern of the full-term infant is rhythmic, sustained, and efficient. Sucking speed and force begin to decrease with satiety. Each infant has a unique sucking pattern that may vary from feeding to feeding depending on factors such as fatigue and hunger. Most infants complete an oral feeding in 20 to 25 minutes.

An infant’s first sucking pattern is called suckling.44 During suckling, the tongue moves back and forth, and the jaw opens and closes, following the movement of the tongue.70 Typically, the tongue extends to, but not beyond, the border of the lips. Suckling is the predominant sucking pattern during the first 4 months of life. At 1 month of age, a hungry infant usually performs one suck per swallow. However, as the infant becomes satiated, he or she decreases the force of suction, taking in less and less liquid with each sucking motion. The rate slows down to about two to three sucks per swallow. Slight liquid loss and air intake may occur with suckling and are primarily observed in the second and third months, after the infant’s physiological flexion has disappeared but before the infant has acquired mature oral motor control.

At 4 months of age, the tongue begins to move up and down, the hallmark movement of true sucking. The wide jaw excursions of the young infant are reduced, less liquid is lost, and nipple suction force increases. By 4 months of age, the infant is capable of taking in 20 or more sucks from the breast or bottle before pausing. Swallowing occurs intermittently (after four to five sucks) and without pausing. Breathing slows during sucking and occurs within and between sucking sequences. Occasionally, the infant may cough or choke when he or she momentarily loses coordination of sucking, swallowing, and breathing.

The 6-month-old infant demonstrates strong up-and-down tongue movement with minimal jaw excursion during sucking. Jaw stability increases and allows for better control of tongue movement. The lip seal is tighter, and liquid loss no longer occurs. In fact, 6 months is the age when many caregivers in the United States introduce the cup, usually a sipper cup with a spout. When first presented with a cup, the infant will try to use a suckling pattern so the jaw continues to move up and down, and the tongue moves back and forth in the mouth. The wide jaw excursions can result in some liquid loss. An infant’s early attempts at cup feeding may be accompanied by some coughing.

At 9 months of age, the infant continues to feed from the bottle nipple using strong sucking patterns. When drinking from a cup, the jaw is not consistently stable on the rim of the cup, which makes drinking from a cup somewhat messy at that age. The infant stops to swallow or breathe after one to three sucks from the cup.

At 12 months of age, many infants make a full transition from bottle to cup for drinking during mealtime but may continue to bottle-feed at other times. Jaw stability, and consequently cup support, continues to be somewhat of a challenge. The infant may try to overcompensate by protruding his or her tongue slightly beneath the cup for additional support. At this age, elevation of the tongue tip during swallowing occurs for the first time. He or she bites on the rim of the cup to make the jaw more stable and obtain greater control of the cup. By 12 months of age, sequences of three suck-swallows occur during cup drinking.44

By 15 to 18 months of age, the infant has excellent coordination of sucking, swallowing, and breathing. When drinking from a cup, the infant’s swallowing follows sucking without pauses. Coughing or choking rarely occurs.

At 24 months of age, the child can efficiently drink from a cup. He or she uses both up-and-down tongue movements and tongue tip elevation. Internal jaw stabilization develops, and the jaw appears still. The jaw becomes stable enough to support the rim of the cup, and biting on it is no longer necessary. The child swallows with easy lip closure and does not lose liquids from the cup. Lengthy suck-swallow sequences occur.

As the infant gains more control of jaw, tongue, and lip movement, he or she also learns to coordinate and arrange oral movements into rhythmic patterns of sucking, swallowing, and breathing.16 The intricate synchronization among the oral structures is perhaps more important to the feeding process than the development of control of any one oral structure by itself.

Biting and Chewing

An infant’s first biting or chewing movements are reflexive. At 4 to 5 months of age, the infant uses a rhythmic, stereotypic, phasic bite-and-release pattern on almost any substance placed in the mouth (e.g., a soft cookie, a cracker, or a toy). The jaw moves up and down rather than sideways and diagonally. When the phasic bite-and-release pattern occurs rhythmically and repeatedly, it is called munching. A munching pattern is characterized by vertical jaw movement and a back-and-forth tongue movement. The ability to move the tongue and jaw sideways is not yet developed at this age. The munching pattern allows the infant to successfully eat pureed or soft foods that dissolve quickly.65

By 7 to 8 months of age, the infant begins to exhibit variations in this up-and-down munching pattern. He or she begins to use some diagonal jaw movement when the texture of the food requires the jaw to move both horizontally and vertically. The infant continues to use the phasic bite-and-release pattern when he or she bites on a cookie; thus, the jaw closes abruptly on the cookie and the infant sucks on it. The jaw holds the cookie, but the infant cannot yet successfully bite through it. A piece is broken off while the jaw remains closed on the cookie. When the infant receives food on a spoon, the upper lip actively cleans it from the spoon. The lips become more active during sucking and maintaining the food within the mouth.

By 9 months of age, the infant handles pureed and soft foods well. He or she continues to use a munching pattern, but the up-and-down jaw movements are now interspersed with diagonal movements. The infant transfers the food from the center of the mouth to the side using lateral tongue movements. The same lateral movements keep the food on the side during munching, making that process effective in mastication of soft or mashed table food. The lips are active during chewing, so they make contact as the jaw moves up and down.

Rotary chewing movements develop at approximately 12 months of age and are made possible by the increasing stability, control, and mobility of the jaw, evidenced by the child’s sustained, well-graded bite on soft cookies. The tongue is actively involved in chewing by moving food from the center of the mouth to the sides, licking food from the lips, and demonstrating tip elevation on occasion. The infant is able to retrieve food on the lower lip by drawing it inward into the mouth.

At 18 months of age, the infant exhibits well-coordinated rotary chewing. He or she is able to chew soft meat and various table foods. The child can control and sustain bites and can bite off a piece of a hard cookie or a pretzel. The tongue becomes increasingly mobile and efficiently moves food within the mouth.

At 24 months of age, the child can eat most meats and raw vegetables.65 The child can grade and sustain the bite and can easily bite on hard foods. The circular jaw movements that characterize mature chewing are present at this age. The tongue transfers food from one side of the mouth to the other using a rolling movement and moves skillfully to clear the lips and gums. Lip closure during chewing prevents loss of food.

Self-Feeding

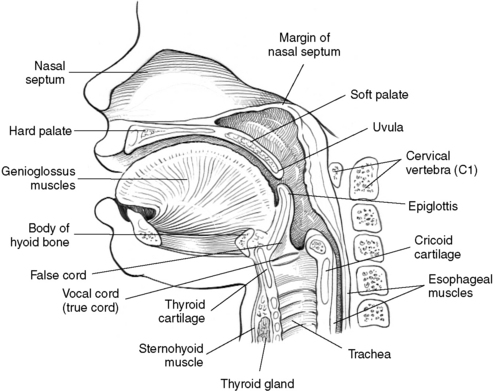

The caregiver can introduce new challenges to the feeding process even before the child shows full mastery in a certain area of performance. Table 15-3 outlines the developmental sequence of self-feeding. The ages are approximate and overlapping.

Children are often eager to feed themselves. As early as 6 months of age, the infant may bring his or her hands up to the bottle and try to hold it. The caregiver should not prop the bottle because the infant lacks the motor skills necessary to remove the bottle if choking occurs. Also, the infant typically lacks the cognitive understanding that a dropped bottle can be retrieved and put back into the mouth. Infants older than 8 months of age actively hold the bottle, but caregivers should monitor their self-feeding to ensure adequate intake, because infants are easily distracted once they satisfy their initial hunger.

Typically, finger feeding develops quickly and naturally by about 8 months of age when the infant receives soft cookies or crackers to hold. At this age, infants exhibit a radial digital grasp, which positions the cookie for entry into the mouth. From 9 to 13 months of age, the infant develops several important abilities, including better control of sitting posture, improved sitting balance, refined pincer grasp with controlled release, and refined isolated forearm and wrist movements, all of which greatly improve self-feeding skills. By 12 months of age, finger feeding is generally a preferred and enjoyed activity and occurs simultaneously with certain psychosocial changes that signal the infant’s increased desire for independence, often manifested by refusal to be fed. The selection of finger foods should match the child’s oral–motor skills (e.g., cooked vegetables are easily grasped and mashed with the tongue and gums).

Infants younger than 1 year of age will grasp, wave, and bang spoons during feeding. Around 12 months of age, the infant demonstrates an understanding of the spoon’s function by poking at a bowl of food with a spoon and bringing it to the mouth. Because visual monitoring of the spoon’s position is poor and the infant has difficulty sequencing scooping movements or adjusting the forearm and wrist, the food often slips from the spoon before it reaches the mouth. Attending to the whole activity and recognizing when the spoon is empty, which requires sufficient cognitive changes to use feedback, is necessary before the infant starts to control the wrist and forearm sufficiently for spoon-feeding. Infants will frequently insist on self-feeding even though independence means less success at satisfying hunger.

Full spoon-feeding proficiency emerges between 15 and 18 months of age when the infant begins to bring a spoon with sticky food, such as yogurt, into the mouth with minimal spillage. The infant holds the spoon in a pronated gross grasp and uses primarily shoulder movement to bring it to the mouth. By 24 months of age, the child spoon-feeds without spillage, balancing the spoon to hold a variety of foods. He or she holds the spoon in the radial fingers with the forearm supinated and is able to obtain the food and efficiently place the spoon into the mouth. Between 30 and 36 months of age, the child may begin to prefer a fork for stabbing foods and may learn to eat foods that are more difficult to balance on a spoon (e.g., cold cereal and rice with gravy).

Drinking

Infants as young as 6 months may demonstrate interest in drinking from a cup, but cup-drinking skills do not emerge fully until 12 months of age. At that time, the infant is better able to correctly position the cup to the mouth and to tip it at a degree that makes spillage less likely. There are several types of cups that can facilitate an infant’s acquisition of cup-drinking skills. The first type used by the infant is a cup with a lid and a spout. It may have handles or it may be a small cup that the infant can hold in one hand. Placing only a little liquid in the cup initially decreases spillage and allows the child to control the flow. At 24 months of age, the child may begin to use a small 4- to 6-ounce cup without a lid, but spillage is inevitable at this juncture.

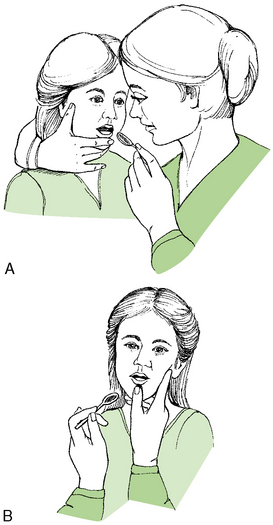

The ability to drink from a straw emerges at about 2 years of age, but it may become a skill even earlier if the caregiver exposes the child to straw drinking at a younger age. Use of a straw requires good lip seal and strong suction to bring the liquid into the mouth (Figure 15-2). In addition to the oral motor skills required to draw the liquid into the mouth, cognitive skills are needed to figure out how to use the straw. The infant often bites or blows on the straw before learning how to suck through it. This framework of typical development should help the therapist identify problems and establish realistic intervention goals and expected outcomes.16

EVALUATION

The process of analyzing and identifying problematic areas should always start by asking parents and caregivers questions about feeding, eating, and swallowing. In addition, the therapist should elicit information about the child’s medical history and evaluate the child for clinical signs of underlying disorders (Box 15-2).

Any evaluation for possible feeding problems should start by assessing mealtime participation, as well as by gathering information and impressions of the feeding situation from the caregivers. The child’s developmental status and health history are also important in identifying feeding problems, as well as for making decisions about further evaluation and subsequent intervention. Usually, such information can be easily obtained from the child’s medical records, from written and oral interviews with the parents and caregivers, and by mere observation. Such data often give the occupational therapy practitioner a general picture and may point to the feeding problem and, sometimes, to its underlying cause. The therapist obtains information about current feeding practices by asking the parents to describe feeding over the course of a typical day. This open-ended inquiry, as opposed to multiple-choice questions, allows the parents to bring forward their concerns. After these initial impressions, the therapist can ask more targeted questions, focusing on certain areas of interest, and obtain even more comprehensive information.

A discussion of the feeding problem from the parents’ perspective is critical because it helps identify their primary concerns. For example, are the parents most concerned about weight gain or is it the length of time required for feeding that poses a problem Does the child seem to lose most of the food consumed during feeding (e.g., through vomiting or reflux) Is the child’s behavior during feeding causing distress for the entire family during mealtime Although the parents’ expressed concerns become the focus of the subsequent intervention, the therapist should always consider other concerns expressed by professionals (such as doctors or other health care personnel) in developing a feeding plan, especially when these concerns differ from those expressed by the parents.

The parents also provide the team with information about the child’s developmental and feeding histories. Obtaining this information helps the therapist identify the root of the feeding problem (e.g., if longstanding sensory or behavioral issues have affected feeding). Inquiring about the feeding history helps the therapist get a sense of any possible frustration and the parents’ ability to cope with the child’s feeding issues. The techniques used by parents may be helpful in identifying appropriate intervention strategies. Parents whose children have received therapy services in the past probably have important information to share regarding interventions that worked and those that did not. The interview can also help the therapist determine which parent or caregiver would do best in implementing recommendations, initiating a referral to an oral motor or feeding program, and discussing information about the child’s progress in developing eating/feeding skills.

Recorded developmental histories are important because they supplement the parents’ report and offer additional insights for the therapist. The written reports of other occupational and physical therapists, speech-language pathologists, early childhood specialists, and teachers provide fundamental knowledge about the child. For example, a child with a sustained hospitalization may not have had enough opportunities to progress, or an early history of restricted upper extremity movement may lead to restricted oral play, influencing sensory systems and, by extension, the ability to eat. Understanding the child’s developmental course and rate of change in other occupational performance areas such as object play and social interactions is important for the therapist to set realistic goals, prioritize objectives, and choose appropriate intervention strategies.

Although these issues are discussed separately, feeding problems are seldom attributable to a single cause and usually are the result of delays or impairments in multiple areas. For example, children with severe sensory problems generally have oral motor skill delays, and children with swallowing disorders often have motor deficits.

Neuromotor Evaluation

The occupational therapist then completes a “hands-on” evaluation of generalized muscle tone, neuromuscular status, and general developmental level. Observation of movement initiation and transition patterns allows the occupational therapist to observe whether abnormal tone could be affecting feeding, eating, and/or swallowing. Muscle tone abnormalities interfere with the ability to maintain upright posture and head/neck alignment. They may also lead to difficulty grading or sustaining oral motor patterns, uncoordinated breathing, drooling, decreased oral exploration, and limited self-feeding. The use of adapted seating systems during the evaluation helps determine the optimal position for feeding. For many children, the upright position is the most effective and provides airway protection. For others some degree of recline may allow for better head control and retention of food.

Examination of Oral Structures and Oral Motor Patterns

The oral sensorimotor examination is the third part of the evaluation. The initial step is observation of symmetry, size, and range of motion of oral structures, including the jaw and larynx proceeding intraorally to the gums, dentition, hard and soft palate, and tongue. A thorough examination of the tongue is critical because the tongue serves many functions in feeding/eating and swallowing. At rest, the tongue should have a well-defined shape, with a nicely rounded tip and a central groove, and be seated inside on the bottom of the oral cavity. Increased oral tone may cause the tongue to be retracted, humped, or have tip elevation and may often be the primary cause of feeding difficulties. Children with food refusal and normal oral tone sometimes use these tongue positions as a defensive posture. In contrast, hypotonia may cause the tongue to be flat, lack a midline groove, and extend beyond the lips.

Eating and Feeding Performance

The final aspect of the comprehensive clinical assessment is the observation of the actual feeding/eating and swallowing process to assess level of performance and to analyze how motor, sensory, cognitive, and communication skills contribute to performance. It is important that the observation mimic those conditions as closely as possible under which the child normally eats and uses foods the child would typically eat. Parents or caregivers can either bring a meal from home or help the therapist select the menu. The therapist places the child in his or her typical feeding position, provides familiar utensils, and asks a parent or caregiver to feed the child the initial portion of the meal.

Observing the parent–child interaction gives the therapist clues about factors that may affect the child’s food intake. During this time, the therapist reflects on the potential meaning of the occupation of eating to the child and his or her interest in participating. Observing the parent–child interaction also provides insights into the everyday context of feeding to help formulate recommendations. The following are signs to watch for:

• Does the parent talk to the child

• Does the child send clear cues regarding readiness to eat, satiation, or preferences to foods

The therapist also needs to use a variety of textures while observing the child eating if this is age appropriate. When possible, the therapist precedes a trial of different textures with relaxed play with the child so that he or she becomes comfortable. Nonintrusive play can also help to establish rapport.

To observe the child’s sensory responses, the therapist should use various textures and attempt placement of food in different parts of the mouth. When the child exhibits aversive responses to food inside the mouth, the parent is asked if the responses are typical or exaggerated because of discomfort with an unfamiliar feeder.

Videofluoroscopic Swallow Study (VFSS)

To further analyze the child’s feeding and eating issues, the therapist may need to return to the child’s medical record for additional information. Does the child have a medical condition that leads to feeding problems or poor weight gain Instances of pneumonia and frequent and prolonged upper respiratory infection may indicate a swallowing problem. To confirm or rule out swallowing problems, a videofluoroscopic swallow study may be needed.

The modified barium swallow study is the radiographic procedure of choice for assessing the oral, pharyngeal, and upper esophageal anatomy, and the physiology of the stages of swallowing. It is particularly useful in identifying aspiration or the risk of aspiration and in tailoring treatment for infants and children with feeding disorders. The test can also be helpful in detecting problems related to head and neck positioning, bolus characteristics, rate and sequence of presentation, and food/liquid consistencies. The results of the test can be helpful in identifying compensatory techniques to minimize the risk of aspiration and maximize eating efficiency.9 The therapist selects the types of food textures based on the child’s current diet and feeding goals and mixes them with liquid or paste barium.58 It is important to remember that the VFSS only shows a brief sample of swallowing, and positioning, amount, and order of food/liquid bolus presentation is up to the occupational therapist or speech pathologist conducting the study.8

VFSS is used to analyze the swallow mechanism and is particularly important for children who aspirate or are at high risk for aspiration because of severe motor problems.29 Factors that suggest swallowing problems include gagging, coughing, choking, nasopharyngeal reflux, increased congestion, wet vocal quality, and the occurrence of respiratory infections and/or pneumonia.46 Aspiration may be silent, so a thorough history and feeding observation are critical. The therapist should distinguish aspiration from penetration. Penetration describes the flow of food or liquid underneath the epiglottis into the laryngeal vestibule but not into the airway. It does not pass through the vocal folds. Aspiration refers to food entering the airway before, during, or after a swallow. Because the recording shows the food traveling through the mouth and pharynx, the therapist receives real-time, detailed information about the swallowing problem.60,69 The results of the VFSS indicate the safety and appropriateness of oral feeding and guide the therapist’s recommendations.71 These may include modified positions and textures for the parents to use during feeding that appear to result in optimal swallowing patterns without aspiration. Although the VFSS gives the therapist important information and insight about the swallowing problem, it may not always be representative of the child’s typical feeding in a more natural environment.

Medical Conditions Affecting Eating

Feeding problems may be associated with specific medical diagnoses. Children with cerebral palsy may be either hypotonic or hypertonic. Facial hypotonia often results in an open-mouth resting posture, drooling, and decreased sensory awareness. Children with hypertonia often present with a strong tongue thrust or bite reflex.54 Congenital oral–facial anomalies such as cleft lip and palate and micrognathia may be associated with Pierre-Robin malformation sequence or may be part of Stickler syndrome.69 Children with Down syndrome often have a small oral cavity, hypotonia, and macroglossia, all of which can contribute to feeding difficulties. Other structural abnormalities that could impact feeding are tracheoesophageal fistula and esophageal atresia, as well as gastrointestinal problems such as gastroesophageal reflux and dysmotility.

Complicated pulmonary and feeding issues are well documented in the premature infant.34,67 The Neonatal Oral-Motor Assessment Scale (NOMAS)50 is the visual observation method most commonly used to assess the nonnutritive sucking and the nutritive sucking skills of infants up to approximately 8 weeks postterm.20

Behavioral difficulties often manifest as food refusal or food selectivity but are often associated with some medical problem such as pain from reflux or an allergic reaction and are often maintained over time by behavioral factors.15 Food refusal can also be associated with poor dentition or sensitive gums. Caregivers sometimes neglect oral hygiene in children with oral motor dysfunction, oral hypersensitivity, or in those demonstrating food refusal.

Gastroesophageal reflux (GER) is an increasingly common problem in the general population and may be an underlying cause of swallowing dysfunction in children. GER occurs when the lower esophageal sphincter does not close properly or opens spontaneously, and stomach contents move upward (acid reflux) into the esophagus. During the first year of life, mild GER is common, resulting in occasional spitting up or vomiting, but it is transient and is generally not considered a medical problem. True gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) results from more prolonged reflux that causes clinical signs and symptoms including regurgitation, nausea, chest pain, coughing, and other respiratory problems. During feeding, infants or young children with GERD may be unusually irritable, arch their backs, and refuse food completely, which leads to poor weight gain.45

The presence and extent of GERD can be confirmed by an esophageal pH probe. The probe is inserted into the esophagus through the nose to monitor abnormal acid levels, usually over a 24-hour period. Radiology studies including barium swallow or upper GI series can detect anatomic abnormalities such as hiatal hernia and assess peristalsis in the esophagus. If the GERD causes aspiration, the x-ray film may show lung changes. An upper endoscopy with esophageal biopsy (also referred to as an esophagogastroduodenoscopy [EGD]) can diagnose inflammatory conditions such as reflux esophagitis or eosinophilic esophagitis, commonly associated with allergies. Fiberoptic endoscopic evaluation of swallowing with sensory testing (FEESST) is a relatively new tool that allows direct visualization of the larynx and pharynx to observe penetration, aspiration, spillage, and residual material.45 Gastroesophageal scintigraphy or “milk scan” assesses the severity of GERD using a noninvasive nuclear medicine scanning technique that involves the ingestion and tracking of radiolabeled milk as it moves through the esophagus and stomach.53

Contextual Factors

Evaluation of the context (environment) in which feeding occurs is essential to the development of intervention plans. In some cases, feeding problems are based primarily on contextual issues, including physical, social, temporal, and cultural. Box 15-3 lists some of the contextual factors that should be considered in assessing feeding.

Understanding the contextual factors that influence mealtimes and feeding performance helps determine the basis for the problem and possible solutions. Certain contextual factors can be changed easily (e.g., a child can be positioned in a chair that is more upright and has straps that maintain good alignment); however, cultural beliefs and family routines are less amenable to change and should be accommodated in the intervention plan. Contextual factors may determine the success of the intervention (i.e., which recommended strategies the family will implement). For example, if the caregivers do not value or prioritize the child’s independence in feeding, they are unlikely to follow through with suggestions to increase feeding independence.

The assessment findings are discussed and interpreted by team members, including the family, to develop a cohesive intervention plan. Any intervention for feeding problems should be holistic, meaning that it considers the whole child, involves the family, and involves collaboration with professionals from other disciplines as needed.60,64

INTERVENTION: GLOBAL CONSIDERATIONS

Problems with feeding, eating, and swallowing are caused by multiple underlying factors. If feeding problems persist as the child grows older, new problems or skill impairments may appear that further complicate the intervention needs. For example, children with dysphagia who require nonoral feeding for an extended period of time may experience subsequent developmental delays in self-feeding skills because of lack of experience. Occupational therapists can provide direct intervention for children with feeding, eating, and swallowing disorders to improve functional participation in mealtimes. Throughout the intervention process, therapists must consider medical and nutritional problems that often coexist with the child’s feeding disorder and collaborate with physicians and nutritionists to create an optimal intervention plan.

Feeding activities occur multiple times throughout the day within a variety of natural environments, and occupational therapists must work closely with families and other caregivers to ensure carryover within daily routines. Children with oral feeding difficulties often require one-on-one attention or increased caregiver time and effort throughout each day. Mealtimes may be quite stressful for parents, especially when the child’s oral feeding difficulties create ongoing problems with nutrition and growth. Whenever possible, typical family mealtime routines should be preserved within the intervention program. Therapists should consider the caregivers’ time investment and provide realistic recommendations that do not significantly increase the burden of care within the family system. Parents of children with feeding, eating, and swallowing disorders may benefit from peer support groups, which have been shown to strengthen caregivers’ abilities to cope with stressful problems on a day-to-day basis.17

Occupational therapists use a holistic approach when developing a treatment plan for children with feeding, eating, and swallowing disorders. Consideration is given to many different overlapping areas described within the Occupational Therapy Practice Framework, including child factors, performance skills, activity demands, contexts, and family patterns.5 A comprehensive intervention plan may include environmental adaptations, positioning recommendations, sensory development activities, behavioral strategies, neuromuscular handling techniques, food texture modifications, adaptive equipment, or suggestions to improve independence in self-feeding.

Safety and Health

Basic safety guidelines should be followed when providing occupational therapy treatment. Children who demonstrate clinical signs of aspiration may require additional assessment with videofluoroscopy to determine appropriate feeding goals. Therapists must also consider the child’s nutritional status and prioritize treatment goals to maximize a child’s ability to meet basic nutritional needs. Some interventions may require implementation outside of regular meal sessions, so as not to disrupt the child’s ability to meet oral intake requirements.

The Occupational Safety and Health Administration mandates the use of gloves during therapy activities when there is potential for contact with mucous membranes within the mouth.48 Another critical factor when working with different food textures is the understanding that certain foods carry a high choking risk and require modifications or close supervision with young children, especially round slices of hot dogs, small hard candies, nuts, popcorn, raw carrots, fruits with seeds, and chewing gum.

INTERVENTION STRATEGIES

Occupational therapists often recommend changes to the mealtime environment to promote success with oral feeding. Environmental adaptations may be recommended to change the structure of the child’s daily mealtime routines. Specifically, therapists may provide intervention recommendations for scheduling and location of meals, length of meal periods, sensory stimulation within the environment, or changes to the order of mealtime activities.

Children often benefit from regularly scheduled meals at consistent times or locations from day to day. When parents allow children to snack or consume liquids throughout the day, there may be little opportunity for children to become hungry during mealtimes, when more nutritious foods are presented. Consistently scheduled meals and snacks allow the child to experience periods of time without eating, which may promote hunger cues and more interest in eating.44 Children should also have a consistent location for meals, such as sitting in a high chair or at a specific table. Wandering around while eating or having meals in different locations every day may be distracting for young children and does not help to establish positive mealtime behaviors.39

Some children may require shorter meal lengths. Children with neuromuscular impairments may eat slowly and have long meal periods because of oral motor or self-feeding difficulties. Parents of children with poor growth may prolong mealtimes to try to encourage more food intake. When mealtimes are longer than 30 to 40 minutes on a regular basis, the demands on the child and the caregiver become extremely high. Children who become fatigued during prolonged meals may expend increased energy to sustain the feeding, outweighing any benefits from additional oral intake.29 Children with delayed gastric emptying or gastroesophageal reflux may benefit from smaller, more frequent meals throughout the day.44 Larger meals may create more discomfort or episodes of vomiting in children with gastrointestinal disorders.

The amount of sensory stimulation and number of distractions within the environment may also impact a child’s oral feeding skills. Many children show improved oral feeding when environmental distractions are limited. Limiting the sensory stimuli within the environment may be beneficial for children who are concentrating on independent self-feeding, children who are hypersensitive to environmental stimuli, and infants with disorganized suck-swallow-breathe coordination. A calming sensory environment can be created with dim lights, reduced noise, soft or rhythmic music, and limited interruptions. Alternatively, some children may eat better when environmental distractions are present during mealtimes. Active toddlers may consume more food or have improved ability to remain seated at a meal when they are allowed access to a favorite toy or television show. The use of distraction may also help some children with defensive behaviors, to reduce the child’s focus on the discomfort of the oral feeding activity.50

Occupational therapists may also consider the order of presenting foods and liquids during meal sessions. Some children have more success when challenging oral feeding activities are presented at the beginning of the meal, when the child is feeling hungry and their muscles are less fatigued. When the challenging task creates disruption or distress and impacts the child’s oral intake for the remainder of the meal, therapists may consider implementing a new intervention outside of meals or during a smaller snack session.

Positioning Adaptations

Oral motor and feeding activities require skilled movement and coordination of many small muscle groups. Children with postural instability and neuromuscular impairments have difficulty with oral motor control if they do not have adequate positioning support. Positioning changes may have an immediate impact on some difficult oral motor problems such as tonic bite and tongue thrust movement patterns. When a therapist is making positioning adaptations, proximal support (i.e., support at the trunk and neck) influences distal movement and control. For this reason, therapists should consider positioning throughout the child’s whole body. Positioning of the feet, legs, and pelvis influences the child’s trunk stability. Stability, muscle tone, and activity in the trunk muscles affect the child’s ability to move or stabilize the head and neck. The position and muscle activation of the child’s head and neck influence jaw movements. Finally, good jaw stability and freedom of movement influence the child’s tongue and lip control.44 Providing external postural stability, excellent alignment, and comfort during oral feeding activities optimizes a child’s oral motor skills and oral intake.

In general, positioning adaptations provide stability in the trunk and support the child in a midline orientation with the head and neck aligned in neutral or slight flexion during oral feeding. The child’s age, size, neuromuscular status, and self-feeding skills must be considered, as well as the caregiver’s position and comfort. Lastly, positioning adaptations should promote social interaction and communication during mealtimes.

Infants may be supported in a variety of positions during oral feeding. Side-lying within the caregiver’s arms is a common position during breast-feeding. This position may also be recommended for children who have difficulty coordinating sucking, swallowing, and breathing, because the impact of gravity does not immediately draw the liquid into the pharyngeal space. It may be difficult for the caregiver to hold a child in a side-lying position for prolonged periods, especially with older children or infants with hypotonia. Infants may also be supported in supine position within the caregiver’s arms or on a caregiver’s thighs facing the caregiver (Figure 15-3). The supine position provides excellent alignment and midline orientation for infants who take formula from a bottle. An infant seat, car seat, or a Tumble Forms Feeder Chair (Figure 15-4) may be adapted with small rolls to provide head and trunk support or slight shoulder protraction to help an infant hold his or her own bottle. Both of these positioning options allow the feeder to have two hands free, creating opportunities to provide oral motor support or implement handling techniques.

For older infants and toddlers who are engaging in spoon-feeding activities, additional positioning options are available. A regular high chair may provide adequate trunk support and can be easily adapted with small towel rolls for additional foot support or lateral support. The height of a standard high chair also allows caregivers to sit comfortably at a table, promoting social interaction between the child and the family.

Older children with neuromuscular impairments may require a wheelchair or a Rifton chair (Figure 15-5) to provide optimal support during oral feeding. A variety of options and accessories are available for customization of these positioning devices. Within a seated position, the child should have supported feet and neutral pelvic alignment. Lateral trunk or arm supports, a pelvic strap, or a tray may help to provide more stability for the trunk. Wheelchairs may also be customized with a padded vest strap or humeral wings to help promote a forward position of the shoulders and arms for added stability.

FIGURE 15-5 Rifton chair provides a firm base of support to trunk and feet during self-feeding. (Courtesy Kennedy Krieger Institute.)

Research has been conducted to evaluate the use of adaptive seating in children with neuromuscular impairments and developmental delays. Results from this research indicate that children demonstrated improved head control, reaching, grasping, sitting posture, and visual tracking when using positioning devices, as well as decreased dependence on caregivers during activities of daily living.35 Hulme and colleagues reported that optimal positioning included vertical head and trunk position, hip flexion greater than 90 degrees, knee flexion at 90 degrees, and feet supported on a flat surface.35

Therapists may need to work with families to determine whether positioning equipment will fit comfortably within the home and to evaluate caregiver perceptions about adaptive equipment. Reilly and Skuse studied positioning during mealtimes within the home for children with cerebral palsy.52 They found that positioning problems were common among children with cerebral palsy; however, only 50% of parents who received adaptive positioning devices used the equipment regularly. Occupational therapists must evaluate each child and caregiver individually to determine the best options for positioning during oral feeding, provide education about the benefits of proper positioning, and suggest alternatives to adaptive equipment when necessary.

Interventions for Sensory Problems

Abnormal sensory processing, such as hypersensitivity to food tastes, textures, or smells, can create significant problems with oral feeding. Children with oral hypersensitivity often react negatively to touch near or within the mouth. They may turn away from feeding or tooth-brushing activities, restrict food variety, gag frequently, or have difficulty transitioning to age-appropriate food textures. Children diagnosed with generalized tactile defensiveness have a significantly higher incidence of oral hypersensitivity and oral feeding difficulties compared with typical peers.62 Oral hypersensitivity is also common in children who have received extensive medical interventions. Medical interventions such as intubation, orogastric or nasogastric tube feeding, or frequent oral suctioning may have caused ongoing distress or gagging, affecting the development of the sensory systems. Early feeding problems experienced in infancy, such as gastroesophageal reflux or swallowing difficulties, may have created negative associations between food consumption and discomfort.61 The child’s sensory system becomes overprotective, and hypersensitivities may continue long after the noxious stimuli or swallowing impairments are eliminated. Children with developmental and neurologic conditions, including diagnoses such as autism, pervasive developmental disorders, cerebral palsy, traumatic brain injury, genetic conditions, and generalized sensory integration dysfunction may also exhibit oral hypersensitivity.

In most young children, oral exploration and gradual adaptation are natural processes assisted by oral feeding and associated comfort and caregiver bonding. Children who experience prolonged periods of nonoral feeding may demonstrate signs of oral hypersensitivity.64 When the child’s oral sensory system is not challenged to explore tastes and textures of objects and foods during critical periods of development, the child may have difficulty adjusting to new oral stimuli at a later developmental stage.61

Occupational therapists create opportunities for gradual oral sensory exploration through play and positive experiences to reduce oral hypersensitivity. Children may tolerate greater sensory input if the activity is under the child’s control and provided in the context of a motivating, developmentally appropriate activity.14 Therapists provide access to textured objects, teethers, or vibrating toys, and playfully encourage the child to explore them with his or her hands, face, and mouth. Therapists may also engage the child in songs or games to encourage self-directed touch to the face, or play dress-up with hats, scarves, or sunglasses.

Children with oral hypersensitivity may benefit from generalized sensory deep pressure or calming strategies such as slow, linear rocking before oral stimulation. Infants may be encouraged to soothe themselves with hand-to-mouth activities or a pacifier.

Children may gradually improve acceptance of therapist-directed touch with firm pressure that is first applied distally on the body, such as on the arms or shoulders, before moving to touch near the face. A variety of tools can be used to provide stimulation within the mouth, including a gloved finger, a warm washcloth, a Nuk brush, a Pro-Prefer (nonridged) device, an infant or child toothbrush, or a teething ring. Applying firm pressure to the child’s gums or palate may help to reduce oral hypersensitivity. Older children with more mature oral motor skills may enjoy whistles, oral sound-making games, bubbles, and blow toys to improve oral sensory processing.

During feeding activities, the occupational therapist introduces new flavors and textures gradually. A lollipop or teething ring can be dipped into a new flavor of food. Children may advance their oral feeding skills when slight changes are made to their current preferred foods. The therapist can gradually thicken a food, combine strained baby foods with pureed table foods for stronger flavors, or change food temperatures to expand the child’s sensory experiences. The therapist or parent should provide consistent praise and encouragement for the child’s oral exploration and feeding attempts.

Some children with sensory integration dysfunction have low sensory registration and may demonstrate poor oral sensory awareness. These children may frequently seek oral sensory stimulation by mouthing their hands, toys, or clothing. They may have decreased awareness of drooling or try to overstuff their mouths when eating. Occupational therapists may establish a treatment program to provide enhanced oral sensory input intermittently throughout the day. Oral activities with a Nuk brush, cold washcloth, or vibrating device can be used to provide oral sensory stimulation.39 During mealtimes, foods with strong flavors and cold temperatures may help the child take appropriately sized bites of food. Children who consistently overstuff their mouths when eating may require foods that are cut into pieces, verbal cues, or supervision for safety.

Neuromuscular Interventions for Oral Motor Impairments

A wide range of children demonstrate oral motor impairments that affect the development of feeding skills. Oral motor problems are seen frequently in children with global neuromuscular impairments resulting from cerebral palsy, traumatic brain injury, prematurity, or genetic conditions such as trisomy 21. Children without neuromuscular impairments may also demonstrate oral motor problems when they are delayed in transitioning from a bottle to a cup or from puréed foods to textured foods. Inexperience with normal feeding activities may contribute to oral motor weakness and coordination difficulties. Oral hypersensitivity may cause a child to retract his tongue back within the mouth to avoid stimulation, contributing to maladaptive oral movement patterns. Occupational therapists include oral motor activities within a comprehensive intervention plan to promote strength and coordination for the development of functional oral feeding skills.

Whenever possible, oral motor activities should include foods or flavors to incorporate taste receptors and facilitate the integration of both sensory and motor skills for a functional response. Hypersensitive children may tolerate nonnutritive activities initially, before they are able to accept the additional sensory input that food flavors provide.

Jaw weakness is often seen in children with oral feeding difficulties. This may contribute to an open-mouth posture at rest, drooling, food loss during feeding, difficulty with chewing a variety of age-appropriate foods, or poor stabilization when drinking from a cup. Jaw weakness and instability may also affect lip closure for spoon feeding and control during swallowing. Occupational therapists may facilitate jaw strength with a variety of nonnutritive or nutritive activities. Nonnutritive strengthening activities may include sustained biting or repetitive chewing on a resistive device or flexible tubing (Figure 15-6) before the introduction of food textures. Nutritive jaw strengthening activities may include biting or chewing on fruits or vegetables encased in a mesh pouch or progressive resistive activities with a variety of solid or chewy foods placed over the molar surfaces.56

FIGURE 15-6 Using a resistive device to improve oral motor skills for advanced food textures. (Courtesy of Kennedy Krieger Institute.)

Children with neuromuscular impairments may have strong patterns of abnormal oral movement. A tonic bite may be seen, in which a child bites down forcefully in response to a stimulus and has subsequent difficulty opening or relaxing the jaw. Poor trunk and head control and positioning in an extension pattern may contribute to a tonic bite. Assisting the child into flexion of the neck with good trunk and shoulder support helps to reduce this pattern. A strong tongue thrust movement pattern may also be present, where the tongue forcefully protrudes beyond the border of the lips during oral feeding activities. A well-supported and slightly flexed position reduces the severity of this abnormal movement pattern. Children with tongue thrust may also benefit from oral motor activities to facilitate tongue lateralization and placement of the spoon or food bolus to the sides of the mouth rather than at midline.11

Children may demonstrate immature forward-backward tongue movements during feeding, poor dissociation of the tongue from the jaw, and poor tongue lateralization to control textured food over the molar surfaces. Occupational therapists may engage the child in activities to facilitate tongue movements such as encouraging the child to make silly faces in a mirror or to lick lollipops or favorite flavors at the corners of the mouth or within the cheeks. Stimulating the sides of the tongue and inside the cheeks with a Nuk brush or oral motor tool may encourage tongue lateralization. Elevation of the tongue tip can be facilitated when touching the tip of the tongue with an oral motor device and providing slight pressure on the anterior hard palate just behind the front teeth.11,33

Problems affecting the lips and cheeks include abnormal tightness or weakness. Children may demonstrate lip or cheek retraction, making it difficult for the child to assume or sustain lip closure. Good lip closure and lip seal are needed to assist the child with oral food control and prevent anterior spillage during feeding. It is also very difficult to swallow with retracted lips and cheeks because the lips seal the oral cavity to create pressure to propel the food bolus into the pharyngeal cavity. Slow perioral and intraoral cheek stretches can help promote lip closure before initiating functional activities with spoon-feeding or whistles.

Evidence reporting the efficacy of oral motor intervention is extremely limited. Research Note 15-1 describes one study evaluating oral motor intervention in children with cerebral palsy. However, numerous authors suggest that oral motor therapy is an important component of a global treatment approach for children with feeding problems.6,18,42

Adaptive Equipment

A variety of adaptive equipment is available for feeding activities, including adaptive spoons, forks, cups, and straws. Adaptive equipment may promote improvement in oral motor control, increase independence in self-feeding, or compensate for a motor or sensory impairment.

Occupational therapists should consider the properties of the spoon or fork used in feeding activities. A spoon with a shallow bowl may help a child with decreased lip closure. A spoon with bumps or ridges on the bottom of the bowl or a chilled metal spoon may provide additional sensory input for a child with decreased sensory registration. A rubber-coated or dense plastic spoon may be used as an alternative to a metal spoon for a child who bites down on the utensil. Utensils with shorter handles or larger grip diameters may help a child to self-feed more independently.39

A child first learning to drink from a straw may do well with a shorter or smaller straw, such as one that typically comes with a juice box. These straws require less oral suction and deliver a smaller liquid bolus. Children who require thickened liquids or those with decreased lip closure may benefit from the use of a relatively short straw with a larger diameter. Therapists may also consider using a straw with a specialized one-way valve. When liquid is pulled into a valved straw, it does not fall back into the cup if the child loses suction. A cup with a handle on it may help a child with poor fine motor skills to drink more independently. U-shaped cut-out cups help to maintain a neutral head position when drinking liquid. Clear cut-out cups also allow the therapist or caregiver to easily see liquid entering the child’s mouth when physical assistance is provided for drinking activities.

Modifications to Food and Liquid Properties

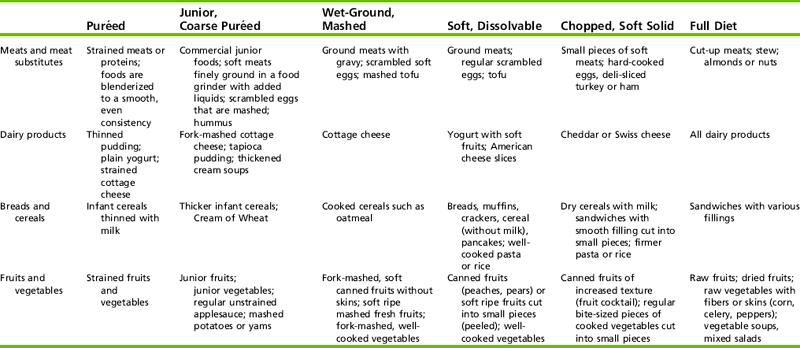

Different consistencies of liquid require different oral motor and oral sensory demands (Box 15-4). Thin liquids presented from an open cup are the most difficult to control within the mouth. Thick, lumpy, or pasty foods such as oatmeal require more oral motor strength and sensory tolerance when compared with smoother and thinner puréed foods. Occupational therapists may recommend changes to food or liquid properties to compensate for a variety of swallowing, oral motor, and oral sensory deficits.

Thickened liquid is easier to control with the lips and tongue, moves more slowly within the mouth, and allows the child more time to organize a bolus for effective swallowing without early spillage into the pharyngeal cavity. Children with dysphagia may not be able to coordinate swallowing with thin liquids, and aspiration and penetration events are more common with thin liquids when evaluated with videofluoroscopic swallow studies.13,26,43 Thickened liquids may also be used to compensate for oral motor difficulties when a child is first learning to drink from an open cup, even when the child has pharyngeal competence with thin liquids from a bottle or sip cup. When a therapist recommends thickened liquids, the child’s liquid intake and hydration status must be closely monitored to ensure the child is meeting daily fluid requirements.