Play

1 Describe the importance and relationship of play to occupational therapy.

2 Describe play theories in terms of form, function, meaning, and context.

3 Describe play assessments and determine their usefulness for assessment and treatment planning.

4 Describe environmental and individual qualities that facilitate or constrain play.

5 Describe how play is used in intervention.

6 Describe how occupational therapists can become advocates for play in our society.

Play…is the way the child learns what no one can teach him. It is the way he explores and orients himself to the actual world of space and time, of things, animals, structures, and people. Through play he learns to live in our symbolic world of meanings and values, of progressive striving for deferred goals, at the same time exploring and experimenting and learning in his own individualized way. Through play the child practices and rehearses endlessly the complicated and subtle patterns of human living and communication, which he must master if he is to become a participating adult in our social life (pp. v-vi).45

All children play, and it is through play that they learn about themselves and the world around them. Watching children play is like looking through a window into their very being. Play has been identified as one of the primary occupations in which people engage, according to the American Occupational Therapy Association (AOTA) Practice Framework.3 As defined by Parham and Fazio, play is “any spontaneous or organized activity that provides enjoyment, entertainment, amusement or diversion” (p. 448) and is “an attitude or mode of experience that involves intrinsic motivation, emphasis on process rather than product and internal rather than external control; an ‘as-if’ or pretend element; takes place in a safe, unthreatening environment with social sanctions” (p. 448).87

There are two sides of play: the science of play, in which play is a critical aspect of human development that deserves serious study, and the art of play, in which the therapist and the child are players, where there is joy, pleasure, and freedom. Occupational therapists need knowledge and skill in both aspects. This chapter describes play as the child’s occupation from a historical perspective, discusses why play is important to occupational therapists, describes methods of assessing play, and discusses play in intervention.

PLAY THEORIES

Clark et al. defined occupations as “the chunks of culturally and personally meaningful activity in which humans engage” (p. 310).31 People create or orchestrate their daily experiences through planning and participating in occupations.114 Occupational therapy generally considers work, self-care, leisure, play, and rest to be the major occupations of people. Occupations can be explained through the substrates of form, function, meaning, and context.31

Play can be viewed through these substrates of occupation:

• As an activity having certain characteristics (i.e., its form, including motor skill requirements and products)

• As a developmental phenomenon contributing to a child’s development and enculturation (i.e., its function, including purposes, processes, and experiences)

• As an experience or a state of mind (i.e., its meaning, including what motivates or satisfies the individual).

Play, like any other activity, takes place within context, which denotes the individual’s environments and the personal, physical, and social elements of each environment.

Form

Many play theorists describe play as categories of activities in which children engage.14,28,33,40 These include such activities as games, building and construction, social play, pretend, sensorimotor play, and symbolic or dramatic play. Children’s play activities change over time and reflect their development.14,83

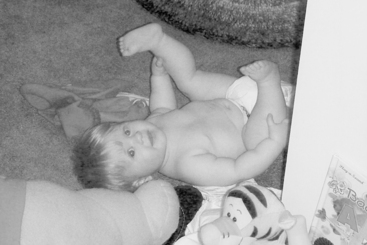

Sensorimotor and exploratory play predominate in infancy (Figure 18-1) as infants develop mastery over their own bodies and learn the effect of their actions upon objects and people in the environment.90,100 Sensorimotor play peaks in the second year of life and then declines. Children continue to use sensory motor play when they learn new motor skills. Exploratory play begins in infancy, and by the end of the first year, infants actively explore their surroundings, demonstrate a beginning understanding of cause and effect, and are interested in how things work. In the second year, play centers on combining objects and learning their meaning. Children begin to classify objects and develop purpose in their actions. Exploratory play gradually declines through the preschool years, but it reappears when the child is learning new skills.14

FIGURE 18-1 A first type of sensory motor-exploratory play is the infant’s exploration of his or her own body. Courtesy Dianne Koontz Lowman.

Constructive play has identifiable outcomes and predominates during the preschool years as practice. Constructive play remains high during middle childhood and adolescence but becomes more abstract. It may develop into arts and crafts. Symbolic play and pretense develop at the end of the first year and through the second, peaking at around 5 years of age and evolving into dramatic and sociodramatic play. During middle childhood, symbolic play and fantasy play are seen in mental games, secret clubs, and daydreaming, and in language play such as riddles or secret codes.14 Television, computer games, and movies are also ways of indulging in fantasy play.

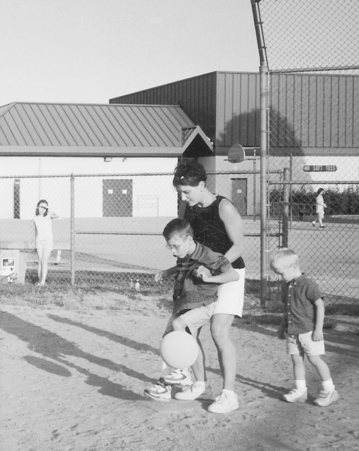

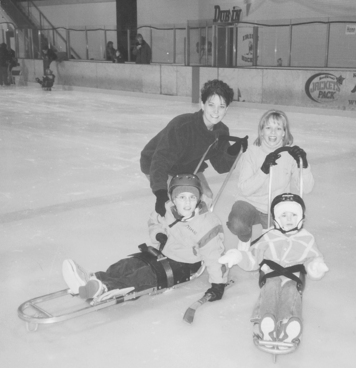

Social play begins very early with interaction between the infant and mother, and by age 3, children are able to engage in complex social games. Children use role play to learn about social systems and cultural norms. Garvey described four types of roles seen in group play: (1) functional roles, such as pretending to be a doctor; (2) relational roles, such as pretending to be mother and baby; (3) character roles, such as those from television and movies; and (4) roles with no specific identity.46 Social play combined with motor play develops into rough-and-tumble play.14 Games with rules teach children to take turns and to initiate, maintain, and end social interactions.59 This type of play predominates during the school-age years.14,44 Social play and games with rules are particularly influenced by the culture. The physical environments available for play, peer groups, and the types of play encouraged by parents have changed as our society has become more urbanized.83 Currently, time, places, and types of play are more planned and structured, such as with organized sports and “play dates” (Figure 18-2).66

FIGURE 18-2 Play today is often highly structured; for example, this play date takes place at the ice-skating rink. Courtesy Jill McQuaid.

Adolescents are concerned with autonomy and being socialized into adult roles. This is a period of transition as obligations, time available for play, changes and refinements of interests, family, and peer pressures all affect teen activity.83 In a study by Csikszentmihalyi and Larson, the most frequent single activity of adolescents was socializing.37 Second was television and third was sports, games, hobbies, reading, and music.

Another way to look at the forms of play is through their characteristics. Scholars of play have not identified a single characteristic common to all kinds of play but have suggested many qualities or characteristics of play that differentiate play from non-play. These characteristics include intrinsic motivation, suspension of reality, internal locus of control, and being spontaneous, fun, flexible, totally absorbing, vitalizing, an end in and of itself, non-literal, and challenging.33,40,55,71,84,96 According to Rubin et al., play is characterized by the following traits: it (1) expresses intrinsic motivation and self-direction; (2) focuses on means rather than ends; (3) is organism-centered rather than object-centered; (4) is noninstrumental or symbolic; (5) shows freedom from externally imposed rules; and (6) reveals active engagement in the activity.100 Takata defined the following principles of play: (1) it is a complex set of behaviors characterized by “fun”; (2) it involves sensory, neuromuscular, or mental processes; (3) it involves repetition of experience, exploration, experimentation, and imitation; (4) it proceeds within its own time and space boundaries; (5) it functions as an agent for integrating the internal and external worlds; and (6) it follows a sequential developmental progression.109

Function

Another way of looking at play is in relation to function, or how play influences adaptation. Play functions include processes, experiences, and purposes. Historically, play has been described as the way a child develops the skills necessary for life,49,100 as a way of working off surplus energy,102 or for recreation and relaxation.100 Modern or contemporary theories emphasize the value of play in contributing to the child’s development or to enculturation. They include using play to achieve optimal arousal15,40 and develop ego function41 and cognitive skills.21,90,112 Sociocultural explanations include the development of social abilities,88,106 role development,96 and play’s contribution to culture.55,103 Johnson et al. identified three ways to consider play and development: (1) play reflects development; (2) play reinforces development; and (3) play is an instrument for developmental change.59

Miller and Kuhaneck conducted interviews on the perceptions of play experiences and play preferences in 10 children between the ages of 7 and 11.78 The children described “fun” as the core category explaining their choices of play activities. The authors developed a dynamic model for play choice describing the interplay of four characteristics—child, activity, relational, and contextual—that affected the perception of fun.

Meaning

Play meaning refers to the quality of the experience or to a person’s state of mind. The attitude a person assumes during play is usually termed playfulness. Liebermann felt that each person has an internal disposition to play that could be described along five dimensions: physical spontaneity, cognitive spontaneity, social spontaneity, manifest joy, and sense of humor.72 Barnett8,9 and Barnett and Kleiber10,11 further related playfulness to the development of cognitive abilities. In the occupational therapy literature, Bundy defined the qualities of playfulness as a person’s intrinsic motivation, internal control, and the ability to suspend reality.23,24 These three elements are best regarded as a continuum, and “it is the sum contribution of these three elements that tips the balance toward play or nonplay, playfulness or nonplayfulness” (p. 219).24 In addition to these three elements, children give and receive social cues to denote that they are playing.

Knox, in a qualitative study of preschool children’s play, identified actions and behaviors that characterized playful children.64 The playful children showed flexibility and spontaneity in their play and in social interactions, curiosity, imagination, creativity, joy, the ability to take charge of situations, the ability to build on and change the flow of play, and total absorption. Non-playful children were less flexible and had difficulty with transitions or changes, expressed negative or immature affect or speech, often withdrew either physically or emotionally from play sequences, did not have control over situations, and tended to prefer adults or younger children for play.

Blanche explored persons’ motivations to engage in meaningful play and identified six motivations: (1) restoring a sense of well-being through quiet activity; (2) exposing oneself to novelty; (3) seeking short-term diversion through light-hearted spontaneous activity; (4) increasing the intensity of involvement in physically and/or mentally stimulating activity; (5) enjoying the ability to master an activity; and (6) creating novelty.16 She suggested that these motivations can act as potential guides to treatment.

Context

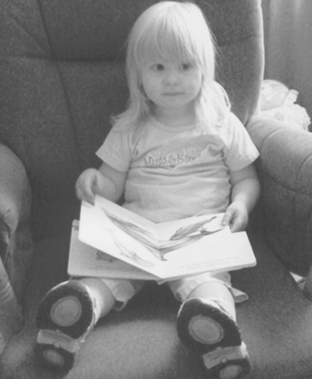

Play also obtains meaning through context. Children’s activities can never be isolated from the environment within which they are playing, nor from familial, social, and cultural influences. The presence or absence of other persons, animals, the physical setting, and the availability of toys and other objects upon which to interact all have a profound effect on children’s play (Figure 18-3). Play context includes cultural and societal expectations of play. Yerxa et al. stated, “The environment provides physical, psychological, social, cultural, and spiritual demands and resources” (p. 7).114

FIGURE 18-3 “Reading” books is an early play activity even before the child is able to actually read. Courtesy Dianne Koontz Lowman.

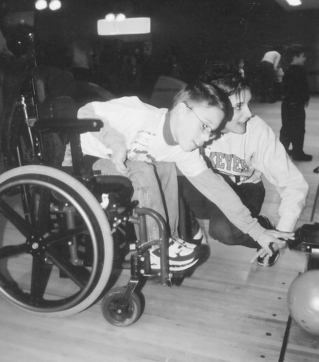

A number of authors have studied the effects of the environment, quality of care, and types of interactions between caregivers and children on play behavior.11,14,54,58 They found that higher socioeconomic status correlated with greater levels of imaginary play, that permissive home environments encouraged creativity, and that high program quality improved children’s social interaction and level of play. The variety of materials and opportunities for children to explore and interact with and their ability to control their activities were associated with improved quality of play. In addition, caregivers and peers who were emotionally and verbally responsive helped to improve the child’s quality of play. Cultural and ecologic factors also influence the way children play.59,100 The cultural factors include child-rearing and parental influences, peer experiences, the physical environment, the schools, and the media (Figure 18-4).12,104 Ecologic influences on play include the effects of stimulus novelty on play, object and material influences, play space density, and indoor versus outdoor play space.

FIGURE 18-4 Mom’s enthusiasm and encouragement add to the playfulness experienced in bowling. Courtesy Jill McQuaid.

All environments offer affordances for and constraints to an individual’s behavior. Knox63 and Michelman77 described factors in the environment that either promote or inhibit play. Factors that promote play include the availability of objects and persons, freedom from stress, provision of novelty, and opportunities to make choices. Factors that may inhibit play include external constraints, self-consciousness, too much novelty or challenge, limited choices, and over-competition.

Contextual components that appear to promote play include (1) familiar peers, toys, and other materials; (2) freedom of choice; (3) adults who are nonintrusive or directive; (4) safe and comfortable atmosphere; and (5) scheduling that avoids times of fatigue, hunger, or stress.100 These elements appear to facilitate playfulness (i.e., the expression of internal motivation and internal control to explore or pretend).

PLAY IN OCCUPATIONAL THERAPY

Play has always been a part of the pediatric occupational therapist’s repertoire, although its importance has altered over the years. Adolph Meyer wrote of work, play, rest, and sleep as being the four rhythms that shaped human organization.76 In one of the earliest articles on play in the occupational therapy literature, Alessandrini referred to play as a “serious undertaking, not to be confused with diversion or idle use of time. Play is not folly. It is purposeful activity, the result of mental and emotional experiences” (p. 9).1 Richmond spoke of play as the vehicle for communication and growth of the child.97 Play in the early years of occupational therapy was used for a variety of purposes such as diversion, development of skills, or remediation.

Mary Reilly was instrumental in bringing play into the forefront of occupational therapy in the late 1960s. She described play along a continuum that she called occupational behavior.96 Through play, children learn skills and develop interests that later affect choices and success in work and leisure. Play is the arena for the development of sensory integration, physical abilities, cognitive and language skills, and interpersonal relationships. In their play, children practice adult and cultural roles and learn to become productive members of society.14,71,96 Reilly felt that play is a multidimensional system to adapt to the environment and that the exploratory drive of curiosity underlies play behavior. This drive has three hierarchical stages: exploration, competency, and achievement. Exploratory behavior is seen most in early childhood and is fueled by intrinsic motivation. Competency is fueled by effectance motivation, a term defined by White as an inborn urge toward competence.113 This stage is characterized by experimentation and practice to achieve mastery. Achievement is linked to goal expectancies and is fueled by a desire to achieve excellence. Using this frame of reference, other scholars studying under Reilly expanded the concepts of play. Florey offered a developmental framework of play and explored the concept of intrinsic motivation as being central to play.43 Takata developed a taxonomy of play and described play epochs based on Piagetian stages,108,110 and Knox examined play in relation to development for the purposes of evaluation.63 Robinson described how play is used for the child to learn rules and roles.98

In researching the relationship between play and sensory integration, Clifford and Bundy found that children with sensory integration dysfunction differed in play scores on the Preschool Play Scale but that many of their play skills were within normal expectations.32 This led Bundy to conclude that there were other foundations for play than sensory integration or physical capabilities, and this led to her studies on playfulness.23–25,105

Occupational science developed in the late 1980s as an academic discipline to study the nature of occupation and how it influences health. Because play is the primary occupation of children, a number of researchers have studied various aspects of play. Primeau studied parent-child routines and how play is orchestrated into daily routines.93 She proposed that parents use two types of play strategies: segregation and inclusion. In the segregated strategy, play times were separate from other daily routines, whereas in the inclusion strategy, play was incorporated into other daily routines. Parents use play routines to support their children’s learning. Pierce studied object play in infants.91,92 She described three types of object rules learned by children: (1) object property rules (that is, the child’s internal representation of the properties of objects); (2) object action rules (the repertoire of actions on the objects); and (3) object affect rules (those factors affecting object choice and keeping play enjoyable).

Knox expanded the concept of playfulness to study the play styles of preschool children.66 Four dimensions of play style were identified using grounded theory methods: preferences, attitudes, approach, and social reciprocity. Within these dimensions, elements of style were determined. Preferences included setting, toys, types of play, roles, and playmates. Attitudes included mood, consistency, and humor. Approach included direction, focus, and spontaneity. Social reciprocity included social orientation, responsivity, and flexibility. The children were described in terms of their unique play style and the elements of style were analyzed across the children. Knox found that play style differed among all the children and the way they approached play episodes was dependent on their play style.

PLAY ASSESSMENT

Even though play is considered the child’s major occupation, and most occupational therapists would agree that it is important to the child, few therapists routinely evaluate it.34,36,70 Couch found that 62% of pediatric occupational therapists who responded to her questionnaire stated that they evaluated play, but less than 20% used criterion-referenced play assessments. Play was usually evaluated through clinical observations or as a part of developmental tests.34

Play assessments are usually of four types: (1) those that assess skills in a particular area through play; (2) those that assess developmental competencies; (3) those that assess the way a child plays, including playfulness and play style; and (4) narratives.

Skills

Most of the play assessments described in the literature are designed to evaluate a particular skill area, such as cognition or social interaction. These assessments use structured play settings, materials, and activities or play observations. The assessments described here include those most often cited in the occupational therapy literature. Rosenblatt99 and Hulme and Lunzer56 assessed play in relation to language and reasoning. The Piagetian stages of cognitive development have formed the basis of a number of play assessments.101,106 The classic assessment of the social aspects of play was developed by Parten. She assessed social participation in play of preschool children by examining two dimensions: degree of participation and degree of leadership.88 Degree of participation included the social interaction during play and was rated as unoccupied, solitary, onlooker, parallel, associative, and organized supplementary play. Degree of leadership included how much the child depended on or directed others in play.

Development

A few assessments rate the developmental skills of the child through play. Linder developed a transdisciplinary play-based assessment that assesses the child in cognitive, social-emotional, language, physical, and motor development through naturalistic play.73

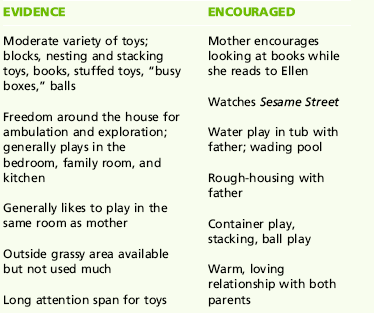

Two assessments developed by occupational therapists explore play in its developmental aspects: the Play History108–110 and the Knox Preschool Play Scale.19,62,63,65,67 Takata described play developmentally within time and space and felt that play reflected the interaction between the individual and the external environment. The Play History is a semistructured interview and play observation, yielding information on the child’s daily activity schedule. She identified two elements of play: form and content. Form parallels changes in development and includes the choice of play materials, amount and nature of playfulness, and organization in play. Content reflects life’s situations and is the expression of the child’s immediate needs, impulses, and physical and emotional state. Takata developed a taxonomy of play epochs based on the Piagetian stages to analyze the interview and play observation. Behaviors are classified as evident, not evident, encouraged, and not encouraged. As a result of the analysis, a play prescription can be developed. Behnke and Fetokovich conducted reliability and validity studies on the Play History and found it to be a reliable and valid instrument for assessing children’s play behavior.13 Bryze discussed the play history as a guide to using narrative in assessment of past and present play behavior.22

The Knox Preschool Play Scale is an observational assessment designed to describe developmental skills as seen during play for children through 6 years of age.62,63,65,67 This assessment was revised by Bledsoe and Shepherd19 and more recently by Knox.65 The scale describes play in terms of 6-month increments through age 3 and yearly increments through age 6. Four dimensions are examined: space management, material management, pretense/symbolic, and participation. Space management is the manner in which the child learns to manage his or her body and the space around it. Material management is the way in which the child manages his or her material surroundings. The pretense/symbolic dimension is the way in which the child learns about the world through imitation and the development of the ability to understand and separate reality from make-believe. Participation is the amount and manner of social interaction. Children are observed indoors and outdoors and rated on all four dimensions (Case Study 18-1.). Bledsoe and Shepherd examined reliability and validity on the first revision with typically developing children.19 Harrison and Kielhofner did the same with children with disabilities.50 Both studies found the scale to be highly reliable and valid. Many studies have been conducted using the Knox Preschool Play Scale, and these have been summarized by Knox.65,67

Experience

The third way therapists assess play is to analyze the child’s experience or state of mind when playing (i.e., playfulness and play style). Barnett devised a rating scale based on Liebermann’s playfulness concepts.8,9 Children were rated on items representing the five playfulness traits: physical spontaneity, manifest joy, sense of humor, social spontaneity, and cognitive spontaneity.

Bundy developed the Test of Playfulness (ToP), designed to assess the individual’s degree of playfulness.24,25 The scale contains 68 items representing four elements of playfulness: intrinsic motivation, internal control, ability to suspend reality, and framing. The child is rated on scales of extent, intensity, and skill. The ToP can be scored from direct observations or videotapes of children engaged in free play. Bundy and her associates have also developed an assessment of the environment’s capacity to support playfulness, the Test of Environmental Supportiveness (TOES).105

The previous assessments are based on behavioral observation and parent interviews. Because play is unique to the individual, it is important to obtain the child’s own perspective of his or her play, and this is usually done through self-report. Henry developed the Pediatric Interest Profiles, three age-appropriate profiles of play and leisure interests and participation for children from 6 to 9 years of age, from 9 to 12 years, and from 12 to 21 years.51 The profiles assess what activities the child is doing, the child’s feelings about the activity, how skilled they perceive themselves, and with whom they play. They can be used in evaluation in three ways: (1) to conduct a play interview, (2) to identify children and adolescents who may be at risk for play-related problems, and (3) to set play-related goals and identify play or leisure activities to use in intervention.

Ellen’s weaknesses included the following: she was behind in all areas of development; she showed some mild hypersensitivity to tactile and auditory sensory stimuli; her mother lacked expertise and knowledge in facilitating development and was apprehensive about Ellen’s reflux, and she rarely allowed Ellen to challenge herself or become upset. Ellen’s mother had few social and emotional supports.

The following goals were established for treatment: (1) improve developmental skills through play; (2) improve play and playfulness; (3) enable Ellen’s mother to play with her, incorporate play into their daily routines, and scaffold play to encourage new skills and abilities; and (4) increase Ellen’s mother’s knowledge of developmentally appropriate play.

The intervention plan included weekly sessions with Ellen and her mother to teach them both play skills and playfulness. Her mother was also encouraged to seek out other resources in the community such as Mommy and Me classes and gym classes. She was also encouraged to set up play dates with other mothers. Ellen’s father was included whenever he was available.

Both Ellen and her mother made striking gains with therapy. Ellen’s development improved and she became very playful with both her mother and the therapist. Her mother became an active participant in the therapy sessions and became involved in community activities. Individual therapy was terminated when Ellen and her mother enrolled in an early intervention program. A few months later, the therapist visited Ellen and her mother and was pleased with her progress. Ellen was speaking a few words, and she showed the therapist some of the toys and games she played with her mother. Ellen’s mother also seemed much happier and appeared to enjoy her daughter more. The experiences they described were typical, playful, and rewarding for both of them.

In this case, play was the primary goal as well as the therapeutic medium used. It illustrates how effective an occupation-based approach can be.

The information on the Knox Preschool Play Scale is described in terms of four dimensions: space management, material management, pretense/symbolic, and participation. Ellen’s play age in each of the dimensions is described in Box 18-2.

Physical or neurologic conditions were not interfering with her development, and it was felt that her delayed skills were primarily a result of lack of experience or stimulation. Her feeding problems were resolving. Her home environment was conducive to play in terms of space, objects, and people. The parent-child relationships were warm and loving, and her mother was eager to learn new ways to stimulate Ellen’s play.

Advantages and Disadvantages of Evaluating Play

Observing children at play is like looking through a window into their lives. An analysis of children’s play is helpful in assessing their physical and cognitive abilities, social participation, imagination, independence, coping mechanisms, and environment.14,20,46 An evaluation of play and of the child’s abilities as seen through play provides important information regarding the child’s occupational performance as well as performance skills and patterns.

Play is most often evaluated in routine, self-chosen, familiar activities in naturalistic settings, providing the therapist with a picture of everyday competencies. Play assessments based on identifying what the child can do in play enable the therapist to focus on the child’s abilities rather than disabilities.

Some of the disadvantages of play assessments have been summarized by Knox,66 and Bundy.24 Because play is an interaction between the child and the environment, the human and physical factors in the environment can substantially influence the child’s play.66 Play assessments that are designed to take place in standardized settings with standardized toys significantly alter and may inhibit the child’s play. In addition, although play specifies its own purpose, observed behaviors may have different meanings and serve different purposes for different people. It is difficult for an observer to assess the meaning of play to the participant.

Another limitation is in the amount of time available for observation of the child. The therapist must determine whether the sample of behavior is sufficient, typical, and representative of true play. Knox found that over a prolonged time, a child’s play could be vastly different at different times.66 Also, children engaged in play episodes for prolonged periods (up to 1 hour in some cases). To capture a variety of play behaviors, a therapist needs to observe a child multiple times and in a variety of settings.

Interpreting Play Assessments

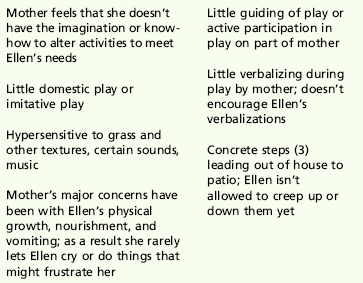

Assessment of play should be a part of every occupational therapy evaluation to develop a complete picture of an individual’s competence in his or her occupational performance and to plan adequate intervention that focuses on helping that individual participate in meaningful and self-satisfying occupations. Such assessments provide the therapist with a picture of how the individual uses play in his or her daily life. An analysis of play also provides the therapist with a picture of the child’s skills in motor, cognitive, and social areas (Figure 18-5). This is especially helpful in assessing a child who does not respond well to standardized developmental testing.

FIGURE 18-5 The occupational therapist assesses motor, cognitive, and social skills during a play activity. Courtesy Jayne Shepherd.

Some of the newer assessments of affect, playfulness, or play style indicate how the individual approaches and gives meaning to the gamut of activities during the day. These instruments hold much promise in helping to determine how an individual balances his or her daily occupations in a meaningful way.

Evaluation in occupational therapy leads to intervention planning. Intervention should capitalize on abilities of the individual to remediate the deficits. Knowledge of the individual’s skills, interests, and play style assists in this planning and guides treatment. Bundy offered a number of considerations in observing an individual’s play that are useful in developing treatment goals. These include the following24:

• In what activities does the child become totally absorbed?

• What does the child get from these activities?

• Does the child engage routinely in activities in which he or she feels free to vary the process and outcome in whatever way he or she sees fit?

• Does the child have the capacity, permission, and support to do what he or she chooses to do?

• Is the child capable of giving and interpreting messages that convey “this is play; this is how you should interact with me now”?

CASE STUDY 18-1

CASE STUDY 18-1