Transition Services

From School to Adult Life

1 Describe the policy context for transition.

2 Identify the population for whom transition services are mandated.

3 Identify transition practices supported by peer-reviewed research.

4 Identify desired transition outcomes.

5 Differentiate between evidence-based practice and practice-based evidence within an educational research and transition context.

6 Describe the role of occupational therapy on a collaborative transition team:

Establishing a vision for the future

Ecologic performance evaluation

7 Describe interagency linkages that support positive transition outcomes.

Individuals with disabilities may spend up to 21 years receiving a public education. Education is viewed as a way for these young people to develop the knowledge, skills, and experiences necessary to make the critical transition from school into a variety of adult roles and activities. Upon exiting high school, young adults with and without disabilities can face a dizzying array of options, including postsecondary education, paid employment, volunteer work, establishing a home, and participating in meaningful and healthy relationships. When a person has a disability, this transition can become more complex and often requires timely planning plus access to variety of supports and services that begin during and extend after high school.

The requirement to provide school-to-adult life transition services was established in 1990 by the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA) (P.L. 101–476). The more recently amended version of the IDEA (P.L. 108–446) states that transition-related planning must begin for students with disabilities when they are 16 years old or earlier based on individual student needs (§614 (d)(1)(A)(i)(VII)). Students receiving transition-related planning and services may graduate or complete high school around the age of 18 with their age peers who do not have disabilities. Others may continue to receive school-funded education and transition services through the age of 21. The high school exit point differs for different students. Ideally students either graduate or complete their schooling and do not drop out. High school exit decisions (before age 22) are based on individual student needs and goals as determined by the transition team.

Transition team is a term that is used throughout this chapter. It refers to the interdisciplinary and interagency team required by IDEA and that is assembled by the school. The transition team is responsible for the development of the student’s individualized education program (IEP) and subsequent transition services (§614 (d)). In some school districts, the transition team goes by other names such as IEP team or individualized transition team. Regardless of the team’s name, the role remains the same and all team members share responsibility for the student’s achievement of positive post–high school outcomes.

The student is the most critical and central member of his or her transition team and is joined by an array of school and community professionals. When appropriate, the student’s parent or guardian joins the team as an essential partner. It is the student’s parents or other family members who most often accompany the student during the entire journey into adult life by providing essential support along the way. In contrast, professional members of the transition team are involved for only portions of the student’s journey. When considered in this way,the need for professional members of the transition team to partner with family members becomes evident.

Students who receive transition services must have a disability that fits one or more of the disability categories recognized by IDEA: mental retardation; hearing impairment including deafness, speech, or language impairments; visual impairments (including blindness); serious emotional disturbance; orthopedic impairments; autism; traumatic brain injury; other health impairments; or specific learning disabilities (§602 (3)(A)(ii)). Furthermore, students with identified disabilities who receive specialized instruction (special education) are automatically eligible for related services such as occupational therapy.

OCCUPATIONAL THERAPY CONTRIBUTIONS TO TRANSITION

Occupational therapy is included as a transition service when the transition team determines that occupational therapy can help the student access, participate in, and benefit from his or her specialized education and transition services. Regardless of the student’s disability label, the occupational therapist’s involvement with a particular student is based on that student’s demonstrated or anticipated problem(s) in performance and participation in education and transition-related activities and contexts. These contexts may include the high school classroom, a variety of in-school environments, public transportation systems, the general community, home, internship placements, community job sites, and more.

Occupational therapists and occupational therapy assistants are highly qualified to serve as transition team members. Occupational therapy personnel working in schools understand the educational performance and participation demands, opportunities, and challenges experienced by children and youth with disabilities. Of importance, they use conditional reasoning56 to understand and, to some extent, anticipate how a student’s disability may affect his or her transition to post–high school activities and roles including postsecondary or vocational education, employment, and community living. Occupational therapists’ positive, future-oriented view of students combines a commitment to student-centered services, collaborative team work, and achievement of performance and participation outcomes, making them a valuable addition to a student’s transition team.

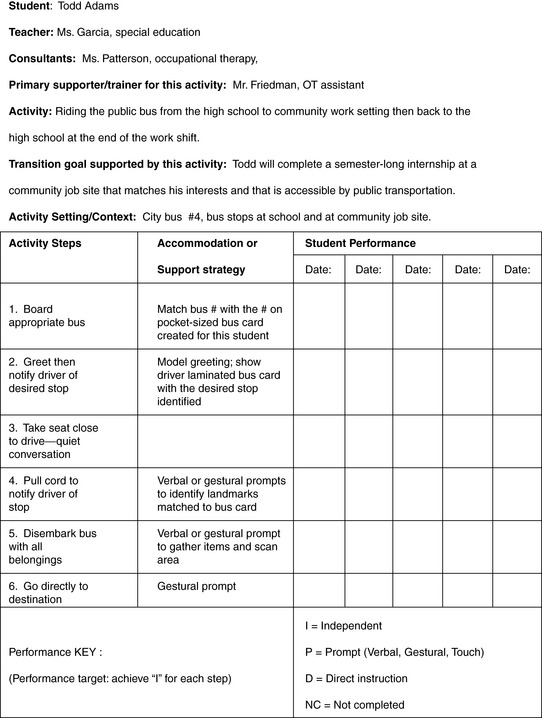

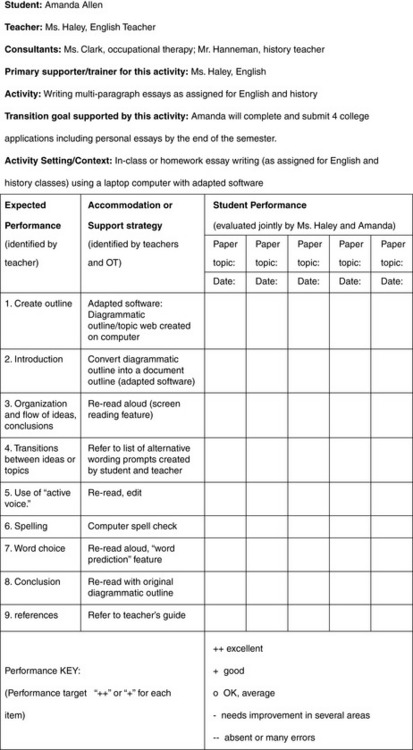

Transition service follows the major steps outlined in the Occupational Therapy Framework: Domain and Process.4 Student-focused evaluation, intervention, and outcome achievement characterize the occupational therapy process and are readily integrated and coordinated with the work of other transition team members. For instance, a transition-focused student evaluation completed by the therapist considers the student in his or her actual performance contexts and all evaluation findings are shared with the team to guide subsequent planning and services (intervention). Occupational therapy intervention may then occur directly with the student, indirectly through other members of the team, or at a system level. For instance, a transition-focused intervention recommended by the occupational therapist to promote student self-determination can be carried out by the therapist by working directly with the student and can be implemented by other team members after training and with support provided by the occupational therapist. In another context, the therapist intervenes on behalf of the student by working at the system level to expand the high school’s work-study or internship program to better include students with disabilities.3,28,34 During the intervention process, the occupational therapist may establish a system for the student’s job coach to consistently gather data on the student’s job performance. Systematic data collection and monitoring of student performance allow the entire team to understand student progress and to modify services as needed. The third and final step of the occupational therapy process focuses on the extent to which the student has achieved targeted performance and participation outcomes. Occupational therapy’s outcome focus is absolutely consistent with the intent of transition services as mandated by IDEA. Occupational therapists who are already familiar with the need to help students make tangible progress toward desired performance outcomes will be an asset to any transition team. It is this critical focus on performance and participation outcomes that drives evaluation and intervention activities and that justifies occupational therapy involvement with transition-age students.

When the occupational therapy process is examined at a deeper level, occupational therapists will recognize that their services can occur at multiple levels and can address student performance skills and patterns, performance contexts, and activity demands. Transition-focused occupational therapists will find themselves helping students establish new skills, transfer skills to new contexts and activities, modify contexts and activities to better support performance and participation, and, at times, use approaches to prevent new performance problems.4 Given the age of the students being served and the positive focus of transition services on student ability versus disability, rarely will the therapist work to remediate underlying student variables tied to body structure or function. Alternatively, compensation and adaptation play a very prominent role in the design and delivery of transition services provided by the occupational therapist and other members of the transition team.68

This chapter connects transition policy and research-supported practices in a way that allows occupational therapy personnel to see, understand, and articulate their role in the transition process and as members of a collaborative, interdisciplinary, and interagency transition team. A variety of student stories and examples are included throughout to further illustrate how occupational therapy personnel work with transition-age youth. Occupational therapy, when added to the mix of transition services, can make a real difference in the lives of young people, whose goals and dreams include some combination of post–high school employment, community living, further education or training, economic self-sufficiency, and social connections.35

THE INTERSECTION OF POLICY AND SCIENTIFIC EVIDENCE

The federal mandate for comprehensive school-to-adult life transition services was issued in 1990 following years of study by the Office of Special Education Programs in the U.S. Department of Education.42,68 While laws guaranteeing all children a free and appropriate public education have been in place since 1975 after passage of the Education of all Handicapped Children Act (P.L. 94–142), outcome-focused research during 1980s and 1990s revealed that educational results for youth with disabilities were disappointing at best. The extensive public investment in specialized education and related services was not consistently producing competent, well-adjusted, and self-sufficient adults. High rates of unemployment or underemployment, dependency, and social isolation characterized post–high school years for students with disabilities.29,44,64,65

While very important in the shaping of federal transition policy, early outcome-focused research did little to help education and related service professionals identify which specific transition practices were most likely to produce the best results for youth. Transition policy as stated in IDEA (P.L. 105-17) specified system level processes and expected post high school outcomes, but does not specify practices to promote those outcomes.

In the absence of research-supported practices, responsibility for the early design and implementation of transition services landed squarely on the shoulders of local and state education agencies, teachers and related service professionals, and others who worked directly with youth. At the same time, the U.S. Department of Education began to invest in transition-related research, model demonstration projects, and personnel preparation efforts to build the knowledge and skill base of transition-focused education and related service professionals.42 This effort continues today through the “What Works” and other research programs sponsored by the U.S. Department of Education’s Institute for Education Sciences. Research findings from a variety of federally funded projects are constantly growing and are presented in understandable and usable formats through the U.S. Department of Education website.

Unlike the transition pioneers of the 1990s, special education and related service professionals in the twenty-first century can now draw upon a growing body of practice-focused research, which takes much of the guesswork out of transition service design and delivery. Furthermore, research-demonstrated relationships between particular transition practices and positive student outcomes provide local school districts with greater confidence that they can meet both the intent and letter of the transition provisions laid out in IDEA. It will be the ongoing interaction between policy and research that will add needed detail to the transition services “road map” used by education and related service professionals working to prepare youth to reach their adult life destinations.

IDEA initially established transition policy and outcome-focused transition services. It is not, however, the only federal law that addresses the transition needs of youth. Other federal laws with particular relevance include Section 504 of the Rehabilitation Act (P.L. 93-516), the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) (i.e., PL 101-336), and Ticket to Work Incentive Improvement Act (P.L. 106-170). Beginning with the IDEA, these four federal laws are introduced here because of their central importance in the overall transition landscape.

Transition Policy

Individuals with Disabilities Education Act

The Individuals with Disabilities Education Improvement Act of 2004 (P.L. 108-446), still known as IDEA, is the federal law most responsible for ensuring that children and youth with disabilities have access to publicly funded, individualized education including school-to-adult life transition services. Initially passed in 1975, IDEA is the law responsible for the strong presence of occupational therapists in public schools. Foundational to IDEA are the following core beliefs expressed by the U.S. Congress and written into the law:

Disability is a natural part of the human experience and in no way diminishes the right of individuals to participate in or contribute to society. Improving educational results for children with disabilities is an essential element of our national policy of ensuring equality of opportunity, full participation, independent living, and economic self-sufficiency for individuals with disabilities (§601(d)(1)(A)).

Beginning with the 1997 amendments to IDEA, participation of all students within the general education context became a central focus. Specifically, students with disabilities receiving specialized instruction (special education) were expected to participate and show progress in the general curriculum alongside their same-age peers without disabilities. This means that for students with and without disabilities, the general education standards provide educational achievement and performance targets.

With specialized support, many students with disabilities can and will achieve general education targets. For other students with disabilities, steady and individualized progress towards general education standards is the expectation. IDEA’s focus on student participation in general education has significantly raised the educational bar for the nation’s children and youth who have disabilities. The general education focus of IDEA challenges previously held views and practices of separate special and general education programs, staff, and curricula.20,42

Accompanying the shift toward a single general education system, special educators and related service personnel including occupational therapists are similarly shifting their roles and activities to better support students and their teachers within a variety of general education and transition-related contexts. Collaboration with teachers and others characterizes the evolving role of transition-focused occupational therapists, who are expected to help students achieve postsecondary education, vocational training, employment, and/or community living outcomes.

Occupational therapists working under the auspices of IDEA must understand the overarching purpose of the law and its key provisions. The full text of the IDEA law and a variety of interpretive resources are readily available at the U.S. Department of Education website (http://www.ed.gov) and are essential reading for school-based occupational therapy personnel. As a starting point, familiarity with the following IDEA purpose statement and definitions will be helpful:

• The purpose of IDEA is “to ensure that all children with disabilities have available to them a free appropriate public education that emphasizes special education and related services designed to meet their unique needs and prepare them for further education, employment, and independent living” (§601(d)).

• Special education is defined as “specially designed instruction, at no cost to parents, to meet the unique needs of a child with a disability” (§602(29)).

• Related services are defined as “transportation, and such developmental, corrective, and other supportive services (including speech-language pathology and audiology services, interpreting services, psychological services, physical and occupational therapy, recreation, including therapeutic recreation, social work services, school nurse services designed to enable a child with a disability to receive a free appropriate public education as described in the individualized education program of the child, counseling services, including rehabilitation counseling, orientation and mobility services, and medical services, except that such medical services shall be for diagnostic and evaluation purposes only) as may be required to assist a child with a disability to benefit from special education, and includes the early identification and assessment of disabling conditions in children” (§602 (26)).

• Transition services are defined as a coordinated set of activities for a child with a disability that “(A) is designed to be within a results-oriented process, that is focused on improving the academic and functional achievement of the child with a disability to facilitate the child’s movement from school to post-school activities, including post-secondary education, vocational education, integrated employment (including supported employment), continuing and adult education, adult services, independent living, or community participation; (B) is based on the individual child’s needs, taking into account the child’s strengths, preferences, and interests; and (C) includes instruction, related services, community experiences, the development of employment and other post-school adult living objectives, and, when appropriate, acquisition of daily living skills and functional vocational evaluation” (§602(26)).

Section 504 of the Rehabilitation Act

A second federal law that impacts public education and the school-to-adult life transition process is Section 504 of the Rehabilitation Act (as amended in 1998 by P.L. 93–516). Initially signed into law in 1973, Section 504 was among the first civil rights laws prohibiting discrimination on the basis of disability by any program or agency receiving federal funding and defines individuals with disabilities as “persons with a physical or mental impairment which substantially limits one or more major life activities” (34 C.F.R. §104.3 (j)(2)(i)). Subparts of the law address specific areas in which discrimination is prohibited, including employment, building and program accessibility, schooling (preschool through secondary education), and postsecondary education (colleges, universities, community colleges, vocational programs).

The concept of “reasonable accommodation” first appeared in Section 504 and is tied to the law’s employment protections. Reasonable accommodation means that an employer (or educational institution) must take reasonable steps to accommodate an individual’s disability. This may mean installing grab bars in work or learning areas, purchasing assistive technology to support job or school performance, ramping an entrance, or providing specific job-related training (refer to the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services Office for Civil Rights’ Web page at http://www.hhs.gov/ocr/504.html). The term “reasonable,” while somewhat vague, is used in the law to protect employers from “undue hardship” when accommodations are needed or requested. The law recognizes that for some employers, the resources needed to provide accommodations for an individual employee who has a disability may exceed employer resources. Most accommodations, however, are in fact low cost, which is outweighed by the benefit of having a motivated and reliable worker who happens to have a disability.

As transition-age students begin to explore the realm of work and careers (Figure 27-1), it is important to recognize that organizations receiving federal funding have a history of Section 504 compliance. Furthermore, these organizations may be very receptive to hiring high school students or recent high school completers who have disabilities. Similarly, postsecondary education programs (e.g., community colleges, vocational schools, universities) that receive federal funding must comply with Section 504 and are often well equipped to accommodate students who have disabilities as they pursue their career-focused education and training.

While Section 504 prohibits discrimination against individuals on the basis of disability, these individuals must still meet all employment and education-related qualifications or admission criteria. Section 504 does not provide the same specialized education and related services that are available under IDEA.

Prevention of disability-related discrimination is at the core of the Rehabilitation Act and Section 504; however, the law also created a nationwide network of vocational rehabilitation (VR) services to enable potential workers with disabilities to ultimately enter and be successful in the workforce. VR is supported by a blend of federal and state resources and provides needed employment and independent living support for adults with disabilities. An individual who is eligible for VR services works with a VR counselor, who can serve as an important member of school-based transition team. The VR counselor is expected to work in concert with school personnel to plan for the student’s future job-related education/training, job placement, and independent living. VR can provide qualified individuals with needed financial support for job training, job placement services, job coaching, postsecondary education, and independent living. In all cases, VR-supported services are outcome oriented, with community employment and improved self-sufficiency as the end goal. School-based occupational therapists may work closely with VR counselors on behalf of young adults with disabilities, to optimize the match between the individual and available job or postsecondary education opportunities, to recommend needed accommodations, and to address community and independent living needs.

Americans with Disabilities Act

The Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) of 1990 (amended in 2008) (P.L. 110–325) is a civil rights law and, like Section 504 of the Rehabilitation Act, focuses on accessibility and nondiscrimination. Unlike Section 504, ADA protections extend beyond programs and services that receive federal funding. The ADA addresses access and discrimination in public and private schools, business establishments, and public buildings. The law also establishes clear accessibility standards for new building construction and public facilities. Occupational therapists working with transition-age youth are advised to become familiar with the ADA and its many provisions so they can assist employers and public facilities to eliminate barriers and provide reasonable accommodations for young adults with disabilities.

Ticket to Work and Work Incentive Improvement Act

Ticket to Work and Work Incentive Improvement Act (P.L. 106-170) was initially passed in 1999. It allows workers who have disabilities and who receive Medicare or Medicaid insurance to keep their needed health care benefits after they obtain paid employment. Before the Ticket to Work program, workers with disabilities faced the potential loss of needed medical insurance and health care when they became employed. Among individuals with disabilities who can and want to work, the possibility of losing needed health care benefits can create a powerful disincentive for employment and self-sufficiency. Ticket to Work now provides a safety net for workers who do not have access to private or employer-provided health insurance. Income earned by workers enrolled in Ticket to Work offsets federal or state disability income. The result is a more self-sufficient worker who has access to needed health care and who has reduced his or her need for publicly funded disability income.

Given the critical nature of health care for many individuals who have disabilities, high-quality transition services must address the student’s future health care needs and available health care insurance. For students whose future employment or postsecondary education opportunities are unlikely to include health care benefits, applying for Ticket to Work benefits is a particularly important component of the transition planning process.

Evidence-Based Practice

Federal education policy and our nation’s commitment to civil rights and equal educational opportunity mobilized initial school-to-adult life transition efforts in the United States. Policies specify expected education outcomes plus procedures and processes that must be followed by state and local education agencies to ensure that all children have access to a free and appropriate education. Policies, however, do not specify which research-supported practices are most likely to produce the desired outcomes. Added to the challenge of identifying the most effective practices is the challenge of generating high-quality research evidence that can be widely applied to diverse students who are enrolled in many different types of educational contexts and activities.49 Despite challenges, promising transition practices have emerged from the ongoing work of education and related service professionals and, increasingly, research (Box 27-1).

Using scientifically based transition practices is an expectation of IDEA, which states that services must be based on “peer-reviewed research to the extent practicable” (§614 (d)(1)(A)(i)(IV)). Like special education, the occupational therapy profession is also dedicated to the principles of evidence-based practice and the continuous expansion of high-quality, peer-reviewed research to improve services and results for the individuals, groups, and organizations served.41

The school-to-adult life transition needs of youth with disabilities can be met by blending policy, a growing body of peer-reviewed research, and the accumulated experience of thoughtful transition service providers. The following set of four recommended practices provide critical direction for transition-focused programs and are based on scientific studies presented in the peer-reviewed literature. Though widely used, these practices are effective only when accompanied by another type of scientific evidence: the systematic monitoring of individual student progress and performance in relevant contexts.55 This second type of evidence is student and context specific; it is not generally reported in peer-reviewed research journals. For the purposes of this chapter, it is be termed “practice-based evidence.”4,18,19,37,55,61

Recommended transition practices from the peer-reviewed scientific literature include the following:

1. Collaborative, interdisciplinary, and interagency teamwork that is outcome-oriented, student-centered, and that enlists family members as transition partners5,46,48,68

2. Application of ecologic assessment and intervention to include the use of accommodation strategies linked to the student’s actual performance context5,46,68

3. Self-determination, self-regulation, and social competence training2,5,15,45,46,67

The preceding practices are supported by research, and none exists in isolation from the others. For example, the recommended practice of evaluating student performance in a variety of actual work or community contexts (ecologic assessment) can be helpful only if it leads to student placement in meaningful community-based work opportunities (paid work experience). Similarly, seeking partnerships with families and then failing to address each family’s unique time and resource constraints can undermine the family’s ability to support and participate as valued team members during transition planning and services (collaborative teamwork). Teams that provide meaningful and real opportunities for students to participate in and influence the future course of their lives (self-determination) can accept student input even when this leads to employment or postsecondary education decisions that do not match the preferences or values of individual team members. Teams that respectfully invite and honor the contributions of students will find that even students with very limited abilities can demonstrate self-determined actions.2,45

Transition-related research appears primarily in the special education literature and relies on multiple research methodologies. Much of this research may be termed “emergent” or “preliminary” in that it offers strong beginning evidence for the use of certain transition practices that are linked with specific student outcomes such as employment, postsecondary education, or community living. Occupational therapy has also been termed a “research emergent” field, which indicates that the body of knowledge linking specific interventions or practices with occupational performance and participation outcomes is still growing.33 Over time and with additional high-quality research, the evidence linking specific transition practices with student outcomes will come into sharper focus.16,41,49 This chapter considers transition practices that are based on multiple scientific studies and reported in the peer-reviewed research literature as evidence-based practice.

Collaborative Interdisciplinary and Interagency Teamwork

Outcome-oriented, student-centered planning and services based on collaborative teamwork are at the center of high-quality transition services.67 For transition-age students, this teamwork is accomplished by the individualized education program (IEP) team. IEP team is synonymous with transition team, the term used throughout this chapter because it conveys an essential transition focus for IEP processes and documentation. As students with disabilities move toward the end of their high school careers, all IEP planning and services must converge around the student’s postsecondary goals and activities.38

Membership on the transition team is determined in part by IDEA policy and in part by the unique interests and needs of the student. At a minimum, the team must include the student, a special education teacher, a general education teacher, and a school district representative (§614 (d)(1) (B)). Transition teams are strongly advised in IDEA and through research to include the student’s parent or family representative and selected representatives from community agencies or programs that are currently providing services to the student or that are likely to provide support or service at a future date (Box 27-2).46

When the student, family members, teachers, and related service personnel are joined on the transition team by representatives from nonschool agencies, the interdisciplinary team becomes an interagency team. Congress, when crafting the IDEA, did not intend for schools to have sole responsibility for transition processes and outcomes. Interagency linkages became a part of IDEA in 1990, indicating the expectation for shared responsibility across local education agencies and adult or community programs. Establishing interagency linkages, while challenging, can be of enormous benefit to students with disabilities who are preparing to exit the public education system.60

Upon graduation or completion of public education programs, a student’s IDEA-based entitlement to school-sponsored educational, vocational, and other services ends. In the place of one lead agency (the school system), a confusing assortment of service providers fills the landscape (e.g., the state vocational rehabilitation agency, the state departments of mental health and developmental disabilities, state brain injury programs, postsecondary education or training programs). Individuals who are no longer eligible for the school’s transition-focused special education or related services become responsible for identifying where to obtain the ongoing services they need and for demonstrating their eligibility to receive those services.

Interagency responsibilities and linkages should be clearly stated in IEP documents developed by the transition team. Failure to initiate and formalize these connections during high school can result in the student’s being left out of services, sitting for extended periods on waiting lists, or losing skills and motivation because of lost opportunities to participate in employment, community living, or postsecondary education. The importance of strong interagency linkages cannot be overstated.

As important as having the right mix of team members is consideration for how the team works together. Collaboration has long been considered an essential quality of effective education and transition teams.23,24,28,50,58 Rainforth and York-Barr provided an enduring description of collaboration within educational contexts: “an interactive process in which individuals with varied life perspectives and experiences can join together in a spirit of willingness to share resources, responsibility, and rewards in creating inclusive and effective educational programs and environments for students with unique learning capacities and needs” (p. 18).51

For transition-age students, collaboration is viewed as an effective way for a team to come together to help them plan for and achieve desired transition outcomes in the areas of postsecondary education, community living and recreation, and employment. Collaborative teams have a shared sense of purpose with shared responsibility for student outcomes.28,58 An effective transition team is not simply a collection of individuals, each with a different set of skills or degrees. In the language of Hanft and Shepherd, transition teams cannot function if the members behave as “lone rangers.”28 Collaboration should be evident during the planning of individualized transition services, which is captured in the student’s IEP document and can also be observed during the implementation of transition services by multiple members of the team in a variety of school and community contexts (Box 27-3).

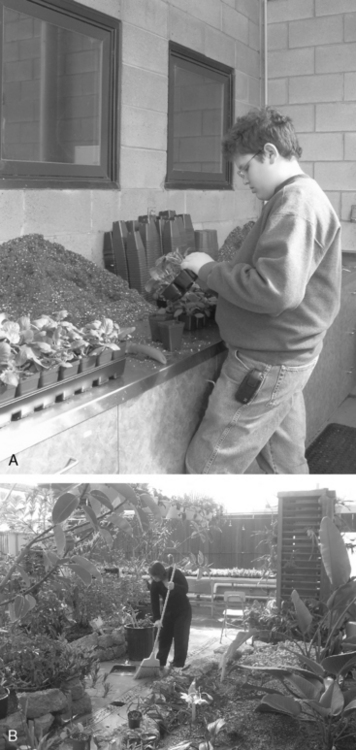

Essential for collaborative teamwork is the creation of a shared, positive vision for student outcomes that drives all subsequent team decisions. To illustrate, a transition-related evaluation to guide service planning for a student who plans to attend college, live in a dorm, and study culinary arts will be significantly different from the transition-related evaluation completed for a student who plans to live at home and work in a private, home-based childcare setting directly out of high school (Figure 27-2). By remaining focused on desired student outcomes and targeted performance contexts, the evaluation process can help team members get “on board” while also building team momentum towards desired results.

Numerous formats exist to help the team move through the critical “vision” process to identify potential transition outcomes.47,57 For example, the student and the team may discuss a future that includes living in an apartment or a home with others who are identified or chosen by the student, use of community services (e.g., transportation, shopping, banking) and amenities (e.g., joining a health club, attending public concerts), employment (full- or part-time employment or other productive volunteer work), postsecondary education (vocational training or university enrollment), and relationships. Not surprisingly, these are goals that most people, with or without disabilities, envision for themselves or their loved ones.

While establishing a positive vision for the student’s future, the team also begins to consider the student’s anticipated long-term needs for resources and support that will allow the vision to become reality. For example, a young adult with significant disabilities may require long-term job support in the form of a job coach, who provides on-the-job training and other support needed to maintain employment. Another individual with high-functioning autism may require social and academic support or accommodations to be in place and operational at the selected university before the start of the school year.

This type of planning is often termed person-centered47 and involves a group of individuals who know the student well and who have come together to engage in positive, facilitated discussion focused on the student’s future. Emerging from this discussion is a comprehensive understanding of the student’s unique strengths and interests, effective support and accommodations, and potential resources and opportunities that can be incorporated into the student’s transition services. Collaborative, group-oriented planning processes have been shown to be a reliable and valid approach to student evaluation and transition planning.31

Depending on the student’s age, anticipated exit point from high school, and the complexity of student needs, the future being envisioned may be 1 to 5 years into the future. To help the team consider all aspects of transition, including desired outcomes and needed support or services, Wehman recommends that transition teams address eight areas67: Many of these can be directly supported by occupational therapy personnel serving as collaborative members of the transition team.67

Transition outcomes that emerge from a collaborative team process help establish a set of transition goals that all members of the team work toward.28,34 Not needed are discipline-specific goals (e.g., “occupational therapy goals” or “special education goals”) established by individual members of the team. Collaboratively developed transition goals help the team unify efforts and share responsibility for services and the ultimate achievement of targeted outcomes (Box 27-4). The collaborative nature of teamwork is illustrated in Case Study 27-1 concerning Mike, a 16-year-old student with emotional, behavioral, and mild cognitive disabilities.

Mike’s story illustrates the benefits of collaborative teamwork and the involvement of different team member perspectives and knowledge that come together to create effective, individualized services. In addition to the benefits realized by the student, collaboration can benefit team members. Collaborative practices promote cooperative and caring relationships among members of the team, which is characterized by open communication, shared responsibility, and mutual support.28

Ecologic Approaches

Ecologically focused curricula for student learners with disabilities were first recommended in the 1970s.13 In the education literature, the ecologic approach is also referred to as community-referenced or environmentally referenced teaching and learning.46 Viewed as highly functional, relevant, and contextual, ecologic approaches are considered an essential feature of effective transition practices.23,51,68 An ecologic approach supports the identification of student performance needs and abilities in the environments that he or she currently uses or is expected to use as an adult. For example, if the team seeks to identify the student’s interests, needs, and abilities as they relate to future community living, an ecologic assessment would take place, to a large extent, in the community and the home. Systematic and careful observation of the student’s performance during home chores, food shopping, banking, using transportation, and bill paying may be completed to identify discrepancies between the demands of the task or context and the student’s current performance level. Services are subsequently designed to reduce these discrepancies by directly teaching the student needed living skills or by modifying tasks and providing accommodations.

Occupational therapy personnel will recognize the ecologic approach; it is deeply ingrained in the field’s view of individuals, groups, and populations who desire participation in all areas of human occupation.4 Ecologic approaches consider the characteristics of the individual and the physical, social, cultural, and temporal demands being placed on that individual by his or her performance context. Similarly, the occupational therapy field has long recognized that human performance and participation can be influenced by strategic changes in features within the environment (e.g., adaptive equipment, addition of social support, task modification).

Occupational therapists can help transition teams adopt ecologic evaluation and intervention approaches. Ecologic thinking contrasts with approaches that emphasize the remediation of a student’s underlying deficits (e.g., physical, cognitive, or psychological) as a precondition for performance and participation in targeted transition-related activities. Ecologic approaches accept and value the student’s current level of performance, which provides the starting point for improving or refining that performance to better match specific environmental demands or opportunities. This is accomplished by pairing context and task-specific training for the student with any needed adjustments to the performance environment.46

Parallels may be drawn between ecologic approaches and dynamic systems theory, which has begun to replace hierarchical and linear explanations of human development and learning.53 Dynamic systems theory offers, in part, an explanation of human behavior and learning tied directly to the opportunities and demands present within that individual’s performance context.26 Extended to the transition process, students with disabilities may be viewed as complex and dynamic systems that change over time based in large part on their direct interactions with opportunities and challenges present in everyday activities and environments. The opportunities or challenges afforded by the environment may, in fact, be inseparable from an individual’s learning and the resulting performance.

Ecologic approaches, as recommended in the transition literature, emphasize ability (versus deficit) thinking. A student’s lack of performance is viewed as a mismatch between the student’s current abilities or interests and the demands or expectations present in the environment (e.g., completing a school assignment, using the telephone, asking for assistance). Student evaluation by members of the transition team, therefore, requires a balanced look at the student as he or she operates within everyday contexts and activities, followed by services that target both the student’s identified learning needs and the environmental demands. The goal is to optimize the match between the student and the demands of a particular context.5,46

Occupational therapists and others on the team can contribute to a transition-focused, ecologic assessment by doing the following:

1. Specify the environments in which the student will likely participate (e.g., home, postsecondary education, vocational, community, leisure).

2. Prioritize the performance environments considered to be most essential in the short term and those that will become more important over time.

3. Identify the activities that occur naturally in the selected, prioritized environments (because of validity concerns, team members are strongly discouraged from using contrived activities or artificial or simulated environments for assessment purposes).

4. Divide responsibility for conducting different parts of the assessment among members of the educational team. Family members and professionals may share responsibilities during the assessment process.

5. Conduct assessments by actually observing student performance during activities in the selected environments. Based on careful observation, discrepancies between the environment and activity demands and the student’s ability to perform can be noted. This type of discrepancy analysis forms the heart of the assessment and guides later planning and decision making.

6. Record the evaluation findings for the purposes of communicating with all members of the educational team, including the student and his or her parents.

7. Share findings with the team to facilitate goal setting and the planning of transition services based on an ecologic model.

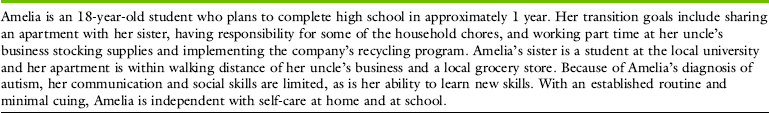

Table 27-1 contrasts an ecologic assessment (left column) with a more conventional assessment (right column) for a student named Amelia.

Self-Determination, Self-Regulation, and Social Competence Training

A student’s active involvement in planning and decision making is considered an important aspect of effective transition services.2,5,15,45,46,68 To effect self-determination, students need to become positive agents of change in their own lives, who have goals, and who are active (versus passive) in the pursuit of those goals. Such students will realize multiple benefits in the form of positive relationships, community engagement, and quality of life.2,15,66,71 Promoting self-determined student engagement in the transition process permeates all transition services and must be supported by all members of the transition team.

Regardless of the type or severity of the student’s disability, it is incumbent upon the team to enlist the active involvement of the student to the maximum extent possible. Research indicates that the transition planning meeting or IEP provides an important opportunity for positive and proactive student involvement.15,45,70 For example, the student (with or without support) may prepare the agenda, introduce team members, or chair the meeting. To assume these functions, students need direct support and preparation from a member of the transition team to consider possible transition goals, activities, and timetables. During the transition-focused IEP meeting, attending professionals and parents must be willing to relinquish “expert control” and support the student’s lead while maintaining a focus on the student’s strengths and abilities versus deficits (Box 27-5).

To help transition team members prepare students to be self-determined, a number of curricula are available.69 With or without a specific curriculum, it is critical that all members of the transition team, including the occupational therapist, have knowledge about self-determined student participation and its relationship to positive transition outcomes. Furthermore, all members of the team must collaborate to implement strategies that promote student self-determination across multiple school and community contexts including engagement in planning and decision making. This means that promoting self-determination cannot be assigned to a single team member and cannot occur within a single context.

Among the critical ingredients needed for students to become self-determined and self-directed agents in their own future are social competencies67 and the ability to self-regulate.1,73 Transition team members must consistently provide students with opportunities to learn and practice self-monitoring and regulation strategies in a variety of contexts while receiving support and constructive feedback (Box 27-6).

Incidents of widely publicized youth violence in schools magnify the importance of building and supporting social competence and self-regulation among transition-age youth. Furthermore, promoting a school climate that skillfully recognizes and addresses bullying and other forms of violence is now considered essential.7,36 School-based transition teams must take seriously the opportunity provided by transition policy and individualized transition services to help youth who are at risk for school or postschool failure or involvement in violence. These students must learn how to set goals, make positive plans, take responsibility, work well with others, and handle challenges or frustration. For youth with significant emotional or behavioral disabilities, this is particularly important and requires early and ongoing attention by the transition team in cooperation with other school-based or community-based professionals (Box 27-7).15

Because social competence is such an important part of self-determined engagement in the school-to-work transition process, students who have autism may have a significant disadvantage in this area (Box 27-8). Self-determination generally requires some level of interaction with others and with a variety of “systems” (e.g., employers, postsecondary education institutions, roommates). Well-planned and timely academic, social, and vocational support can greatly facilitate meaningful participation in adult roles and activities by students who have autism (Box 27-9).

Case Study 27-2 illustrates how transition-related services can support self-determined student participation in transition planning and the ongoing practice of social and self-regulation skills.

Recommended Practice: Paid work experience during high school

According to the National Longitudinal Transition Study 2 commissioned by the Institute for Education Sciences of the U.S. Department of Education, student engagement in paid work before his or her exit from high school is strongly associated with post high school employment.14,44 Even for students who plan to pursue postsecondary education, the ability to obtain and hold down a job is considered a critical life skill that cannot be delayed until all formal education is complete. Furthermore, parallels may be drawn between inclusive educational practices that occur in elementary and secondary school and community-based employment for transition-age youth who have disabilities. Perhaps student employment in the community during the transition from school to adult life is simply an extension of inclusive school practices.59 The importance of paid employment for youth with disabilities cannot be overstated; such employment is often at the center of many school-to-adult life transition programs.

Although there are many ways in which individuals may go about securing paid work,9 students who have disabilities may lack the ability to effectively access or use conventional job search strategies. For these students, supported employment provides an excellent alternative that has strong research support.39,43,52 Simply defined, supported employment is real work that is paid and that occurs in community businesses and organizations with on-the-job training and support provided as needed by a job coach. Robert Lawhead, a parent and supported employment professional from Colorado, described supported employment in the following way during his testimony before the U.S. Senate on Oct. 20, 2005:

In the late seventies and early eighties, professionals developed a process for employing people with very significant disabilities within the regular workforce. The process has been refined over the past 25 years and is referred to as “supported employment” which is defined as integrated paid work, within businesses and industry, with ongoing support. Presently it is estimated that nearly 200,000 people with severe disabilities are employed within our business communities through supported employment and similar strategies such as supported self-employment and customized employment.

Evidence-based research completed over the last 25 years shows that employment programs placing people into business and industry represents a good tax-payer investment. When one public dollar is spent on supported employment service costs, tax-payers earn more than a dollar in benefits through increased taxes paid, decreased government subsidies, and foregone program costs. Further, this positive cost-benefit relationship for community employment holds true for people with the most significant disabilities and is stronger when people are employed individually as opposed to within group models of employment (e.g., sheltered employment).40

Many variations on supported employment exist to meet unique individual or contextual needs. Occupational therapy personnel can be instrumental in helping the transition team apply different supported employment strategies such as job carving or job customization.

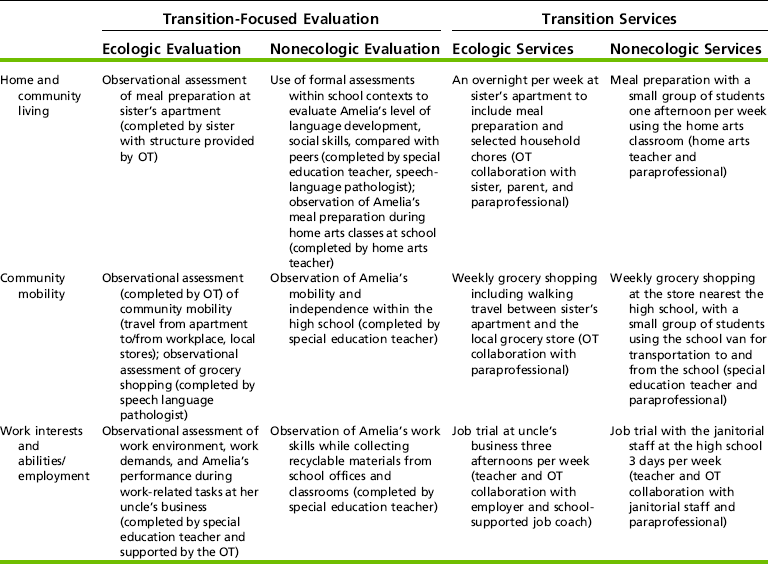

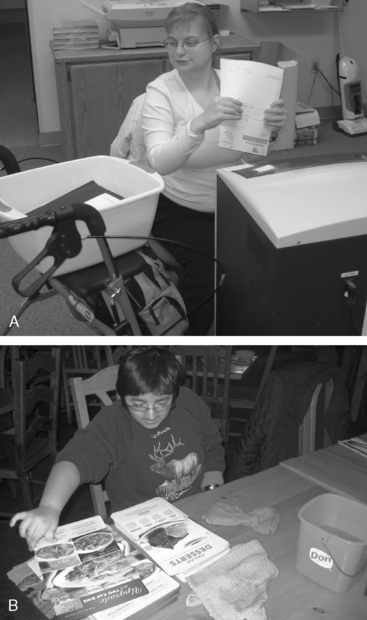

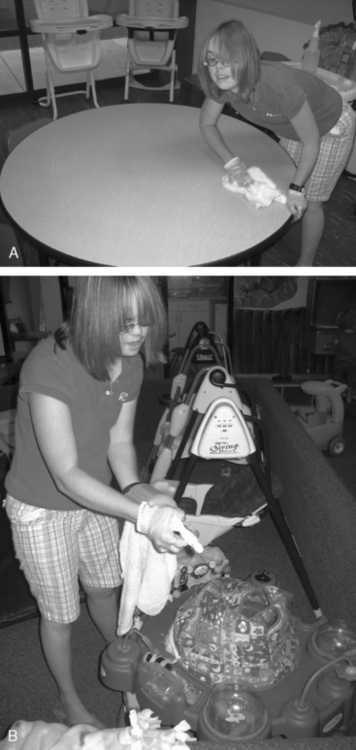

According to Griffin and Targett, job carving is defined as “determining the job seeker’s skills, interests, and contributions and matching these to a set of duties found in the local workplace. Because such job descriptions rarely appear as a perfect match, carving involves creating a new list of duties that meet both employer and employee needs and which complement the common interests of both.” (p. 290).27 For example, a student may obtain an office job with one primary duty carved out of the typical list of office worker duties: paper shredding. In this case, paper shredding matches the abilities, interests, and needs of the student worker and the employer (Figure 27-3).

FIGURE 27-3 Job carving. A, Creating a job focused on shredding office paper. B, Creating a job focused on cleaning menus.

Customized employment, according to the U.S. Department of Labor, “may include employment developed through job carving, self-employment, or entrepreneurial initiatives, or other job development or restructuring strategies that result in job responsibilities being customized and individually negotiated to fit the needs of individuals with a disability.” For example, a student who cannot handle the noise and distractions associated with working in a busy warehouse may work with her transition team to arrange an “after hours” shift to break down, stack, and bundle cardboard boxes for recycling.

Enabling youth who have disabilities to secure community employment that is individually matched to their interests is among the most important achievements of transition-focused teams. It is primarily around employment that local VR agencies become involved and can apply state VR resources to either support the student’s job search and placement process or to fund postsecondary education at a university, community college, or vocational training program as long as a career/job path is evident.5,46 Case Study 27-3 demonstrates how supported employment can work for a young woman who sustained a brain injury.

Education policy and research are focused on improving the quality of education for all students. Special education research relies on multiple research methodologies that identify effective practices that align with IDEA.25 The preceding evidence-based transition practices have been reported in peer-reviewed journals. As with all areas of special education research, the addition of new studies to the literature will help build needed scientific evidence and refine transition practices. Future research will be increasingly scrutinized for quality and the extent to which it answers important and relevant questions. According to Odom and colleagues, “Researchers cannot just address simple questions about whether a practice in special education is effective; they must specify clearly for whom the practice is effective and in what contexts” (p. 41).49

Similar to the emphasis on high-quality research evidence in occupational therapy,41,54,61 special education scholars are developing and debating research guidelines and quality indicators for evidence-based practices.8,49

The long history of research in occupational therapy and special education has relied on many different research methodologies that are being increasingly scrutinized for rigor. Special education has seen the widespread use of four research methodologies, all of which have the potential to add to the evidence base for transition: qualitative,12 correlational,62 single-subject,32 and finally, group and quasi-experimental designs.22 Connected with each of these approaches are proposed quality indicators to help researchers and practitioners evaluate the extent to which the research actually provides evidence for a particular practice.49 As in occupational therapy, special education has not reached consensus on a single standard for evidence or a single set of quality indicators. What is important, however, is the commitment and dedication of special education and related service scientists to continuously meet rigorous research standards regardless of the research approach taken.16,49 To this end, the U.S. Department of Education’s Institute for Education Sciences is actively moving high-quality special education research forward by only funding studies that that will generate research evidence and that meet one of five different research goals63:

1. Identify programs, practices, and policies that may have an impact on student outcomes, and factors that may mediate or moderate the effects of these programs, practices, and policies.

2. Develop programs, practices, and policies that are theoretically and empirically based.

3. Establish the efficacy of fully developed program, practices, and policies.

4. Evaluate the impact of programs, practices, and policies implemented at scale.

5. Develop and/or validate data and measurement systems and tools.

Occupational therapy personnel and special educators working together on transition teams are expected to apply findings from high-quality, peer-reviewed research to the design of transition programs and services for youth (evidence-based practice). Transition services, guided by scientific evidence, are expected by IDEA and the professional and regulatory bodies that oversee teaching and related service professionals. Accompanying peer-reviewed research evidence is the need for systematic progress monitoring and data-based decision making at the individual student and context level.55 This type of practice-based evidence requires attention to the growing body of peer-reviewed research and the systematic monitoring of individual student performance in response to transition services using valid and reliable measures administered with high fidelity.11,21 The following section further explains practice-based evidence.

Practice-Based Evidence

High-quality peer-reviewed research evidence sets the stage for the systematic monitoring of individual student performance during everyday school activities and contexts.21,55 It is the intersection between peer-reviewed research and individual progress monitoring that ensures scientifically based transition practice. The term practice-based evidence18 describes the gathering and interpreting of individual student or client performance data as the basis for intervention planning and actions. Sometimes termed effective practice,61 practice scholarship,19,37 or intervention review,4 practice-based evidence is concerned with the systematic examination of student performance associated with specific education or related service interventions over time (Box 27-10). It is a form of individual progress monitoring called for by IDEA and documented in each student’s IEP (Box 27-11).4,30,72

All members of a student’s transition team engage in the generation and use of practice-based evidence. Unlike research-based evidence derived from peer-reviewed studies, practice-based evidence is specific to a student. This means that data-gathering strategies and performance findings cannot be readily generalized or transferred to other students, groups, or contexts. Data are gathered during student engagement in a variety of transition-related activities and in a variety of contexts.

The occupational therapist’s ability to observe and record student performance and performance patterns while simultaneously considering the demands of the activity and environment can yield important information for the team. This type of performance analysis4 tied to activities at school, in the community, at home, on the job, or during a student visit to a university campus can yield needed data for individualized transition planning and help the team evaluate the relative effectiveness of individualized interventions. A well-executed performance analysis can identify what a student is doing well and where performance breaks down. Performance analysis, which is “the analysis of occupational performance focuses on collecting and interpreting information using assessment tools designed to observe, measure, and inquire about factors that support or hinder occupational performance” (p. 649),4 also allows the evaluator to examine the amount and type of assistance, adaptation, or accommodation needed to support effective student performance.17

Performance analysis can be paired with an activity analysis to pinpoint activity-specific factors that limit or support student participation. Activity analysis is “an important process used by occupational therapy practitioners to understand the demands that a specific desired activity places on a client….When activity analysis is completed and the demands of a specific activity that the client needs or wants to do are understood, the client’s specific skills and abilities are then compared with the selected activity’s demands” (p. 651).4 Activity analysis (further defined in Box 28-13) focuses on the context-specific demands of a specific activity.

Case Study 27-4 illustrates the concept of practice-based evidence while also demonstrating how performance and activity analysis can contribute to this critical aspect of transition service planning, intervention, and outcome monitoring. Case Study 27-5 further illustrates the concept of practice-based evidence through combined performance and activity analysis.

Occupational therapists are well acquainted with progress monitoring and documentation. In many occupational therapy contexts, this process is driven by insurance reimbursement policies. In school contexts, progress monitoring is driven by the IDEA’s accountability expectations and the need for data to guide service planning and intervention.

Both education and related service professionals are expected to contribute to the ongoing data collection for monitoring of individual student learning, performance, and achievement over time.10,55,74 Anyone who has participated in publicly supported education within the United States is familiar with the central role that student evaluation plays in education. Some classroom assignments and tests are informal, whereas others impact decisions about a student’s course grade, school placement, or which education or related services will be provided. Beyond individual student assessment, educational progress is monitored at the school and district levels by states and the federal government (No Child Left Behind Act, P.L. 107–110).

Response to intervention (RTI) is another form of practice-based evidence that is addressed by the IDEA and widespread in U.S. schools (§613 (f)). RTI is the strategic application of educational interventions and the subsequent monitoring of student performance based on those interventions.6 RTI can target any student (including those involved with transition services), who is demonstrating learning difficulty. Initially intended for students with specific learning disabilities, RTI has potential applications to a broader population of learners who are struggling.34 The timely application of strategic, scientifically based educational interventions accompanied by systematic data collection and progress monitoring (practice-based evidence) characterizes RTI. Considered preventive, the RTI model seeks to meet a variety of student learning needs within the general curriculum and through high-quality instruction. When done well, RTI is expected to prevent the overidentification of disability and the inappropriate referral of students for special education and related services.

RTI begins with the least amount of intervention. Simply stated, this means strong general education instruction for all children based on universal design principles (Box 27-12) that can address a variety of student learning styles. Termed Tier 1 intervention, this strong general instruction is accompanied by systematic evaluation of the student’s response to the instruction (practice-based evidence). When good general instruction does not sufficiently boost student performance, more individualized instruction can be implemented for specific students within the context of the general curriculum (Tier 2). Finally, when progress monitoring and systematic data collection reveal that a student has not responded to Tier 1 and 2 intervention and the student continues to lag educationally or behaviorally, intensive and individualized interventions become necessary (Tier 3). Tier 3 intervention can include specialized education and related services. All tiers in the RTI process require continuous student performance evaluation based on measures that are reliable and valid. RTI is an example of how practice-based evidence is used to guide educational decision making. Occupational therapists can support the design and implementation of RTIs at all tier levels and carry responsibility with other team members to monitor the student’s response to the intervention and to adjust services and supports accordingly.

SUMMARY

The transition from school to adult life represents a major life step for young adults. When a disability is present, this transition can be challenging and requires comprehensive and timely planning and service from an interdisciplinary and interagency transition team. Transition teams must have a deep understanding of transition-related policy, research-supported transition practices as presented in the peer-reviewed literature and the ability to systematically gather and use practice-based evidence during the day-to-day delivery of transition services. Occupational therapy personnel on the team are expected to collaborate with other team members during all phases of the transition process: establishing a vision for the student’s future, evaluation of student performance and participation in relevant contexts and activities, outcome-oriented planning, service delivery, and ongoing progress and outcome monitoring. The success of the student and therefore the transition team may be measured by the extent to which students actually achieve postsecondary education, employment, community living, and/or involvement in meaningful and enduring relationships.

Although exciting and absolutely essential, providing effective transition services may feel messy or complicated. How true! Consider the number of players involved along with the number and variety of educational and community contexts needed for valid student evaluation and services, plus the constantly emerging research evidence for specific practices. Occupational therapy personnel are reminded that transition services, even when planned and delivered well, always include an element of uncertainty and unpredictability. However, by holding high expectations for student performance combined with a spirit of flexibility and creativity, occupational therapists and other members of the transition team will be amazed at what students can and do achieve during the school-to-adult life transition process.

REFERENCES

1. Agran, M., Sinclair, T., Alper, S., Cavin, M., Wehmeyer, M., Hughes, C. Using self-monitoring to increase following-direction skills of students with moderate to severe disabilities in general education. Education and Training in Developmental Disabilities. 2005;40(1):3–13.

2. Agran, M., Wehmeyer, M.L., Cavin, M., Palmer, S. Promoting student active classroom participation skills through instruction to promote self-regulated learning and self-determination. Career Development for Exceptional Individuals. 2008;31(2):106–114.

3. American Occupational Therapy Association Transforming caseload to workload in school-based and early intervention occupational therapy services, 2006. Retrieved May 29, 2008 from, www.aota.org.

4. American Occupational Therapy Association. Occupational therapy practice framework: Domain and process, 2nd ed. American Journal of Occupational Therapy, 2008;62:625–683.

5. Bambara, L.M., Wilson, B.A., McKenzie, M. Transition and quality of life. In: Odom S.M., Horner R.H., Snell M.E., Blacher J., eds. Handbook of developmental disabilities. New York: Guilford Press; 2007:371–389.

6. Batsche, G., Elliott, J., Graden, J.L., Grimes, J., Kovaleski, J., Prasse, D. Response to intervention: Policy considerations and implementation. Alexandria, VA: National Association of State Directors of Special Education, 2005.

7. Baugh, T. Bystander focus groups: Bullying—roles, rules, and coping tools to break the cycle. Washington, DC: George Washington University, 2003.

8. Berliner, D.C. Educational research: The hardest science of all. Educational Researchers. 2002;31(8):18–20.

9. Bolles, R.N. What color is your parachute? Berkeley, CA: Ten Speed Press, 2008.

10. Bradley, R., Danielson, L., Doolittle, J. Responsiveness to intervention: 1997–2007. Teaching Exceptional Children. 2007;39:8–12.

11. Bradley, R., Danielson, L., Hallahan, D.P. Identification of learning disabilities: Research to practice. Mahway, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum, 2002.

12. Brantlinger, E., Jimenez, R., Klingner, J., Pugach, M., Richardson, V. Qualitative studies in special education. Exceptional Children. 2005;71(2):195–207.

13. Brown, L., Branston-McLean, M.B., Baumgart, D., Vincent, L., Falvey, M., Schroeder, J. Using the characteristics of current and future least restrictive environments in the development of curricular content for severely handicapped students. American Association for Education of the Severe and Profound Handicapped Review. 1979;4(4):407–424.

14. Cameto, R., Employment of youth with disabilities after high school. Wagner M., Newman L., Cameto R., Garza N., Levine P., eds. After high school: A first look at the postschool experiences of youth with disabilities. A report from the national longitudinal transition study-2 (NLTS2). SRI International: Menlo Park, CA, 2005:5.1–5.21. Available at, http://www.nlts2.org/reports/2005_04/nlts2_report_2005_04_ch5.pdf.

15. Carter, E.W., Lane, K.L., Pierson, M.R., Glaeser, B. Self-determination skills and opportunities of transition-age youth with emotional and learning disabilities. Exceptional Children. 2006;72(3):333–346.

16. Cook, B.G., Tankersley, M., Cook, L., Landrum, T.J. Evidence-based practices in special education: Some practical considerations. Intervention in School and Clinic. 2008;44(2):69–75.

17. Coster, W., Deeney, T., Haltiwanger, J., Haley, S. School function assessment. San Antonio, TX: Psychological Corp./Therapy Skill Builders, 1998.

18. Craig Hospital Improving spinal cord injury rehabilitation outcomes, 2009. Retrieved January 16, 2009 from, http://www.craighospital.org/Research/Abstracts/SCIRehab.asp.

19. Crist, P., Munoz, J.P., Hansen, A.M.W., Bensen, J., Provident, I. The practice-scholar program; An academic-practice partnership to promote the scholarship of “best practices”. Occupational Therapy in Health Care. 2005;19(1/2):71–93.

20. Falvey, M.A., Rosenberg, R.L., Monson, D., Eshilian, L. Facilitating and supporting transition: Secondary school restructuring and the implementation of transition services and programs. In: Wehman P., ed. Life beyond the classroom: Transition strategies for young people with disabilities. Baltimore: Brookes; 2006:165–182.

21. Fuchs, L.S., Fuchs, D. What is scientifically-based research on progress monitoring? (Technical report). Nashville, TN: Vanderbilt University, 2002.

22. Gersten, R., Fuchs, L.S., Compton, D., Coyne, M., Greenwood, C., Innocenti, M.S. Quality indicators for group experimental and quasi-experimental research in special education. Exceptional Children. 2005;71(2):149–164.

23. Giangreco, M. Vermont interdependent services team approach: A guide to coordinating educational support services (VISTA). Baltimore: Brookes, 1996.

24. Giangreco, M.F., Cloninger, C.J., Iverson, V.S. Choosing outcomes and accommodations for children (COACH): A guide to educational planning for students with disabilities, 2nd ed. Baltimore: Brookes, 1998.

25. Graham, S. Preview. Exceptional Children. 71(135), 2005.

26. Gray, J.M., Kennedy, B.L., Zemke, R. Application of dynamic systems theory to occupation. In: Zemke R., Clark F., eds. Occupational science: The evolving discipline. Philadelphia: F.A. Davis, 1996.

27. Griffin, C., Targett, P.S. Job carving and customized employment. In: Wehman P., ed. Life beyond the classroom: Transition strategies for young people with disabilities. Baltimore: Brookes; 2006:289–308.

28. Hanft, B., Shepherd, J. Collaborating for student success: A guide for school-based occupational therapy. Bethesda, MD: American Occupational Therapy Association, 2008.

29. Hasazi, S., Hock, M., Cravedi-Cheng, L. Vermont’s post-school indicators: Using satisfaction and post-school outcome data for program improvement. In: Rusch F., Destefano L., Chadsey-Rusch J., Phelps L.A., Szymanski E., eds. Transition from school to adult life: Models, linkages, and policy. Pacific Grove, CA: Brooks/Cole; 1992:485–506.

30. Heaton, J., Bamford, C. Assessing the outcomes of equipment and adaptations: Issues and approaches. British Journal of Occupational Therapy. 2001;64(7):346–356.

31. Holburn, S., Vietze, P.M. Person-centered planning: Research, practice, and future directions. Baltimore: Brookes, 2002.

32. Horner, R.H., Carr, E.G., Halle, J., McGee, G., Odom, S., Wolery, M. The use of single-subject research to identify evidence-based practice in special education. Exceptional Children. 2005;71(2):165–180.

33. Ilott, I. Challenges and strategic solutions for a research emergent profession. American Journal of Occupational Therapy. 2004;58(3):347–352.

34. Jackson L.L., ed. Occupational therapy services for children and youth under IDEA, 3rd ed., Bethesda, MD: AOTA Press, 2008.

35. Kardos, M., White, B.P. The role of the school-based occupational therapist in secondary education transition planning: A pilot survey study. American Journal of Occupational Therapy. 2005;59:173–180.

36. Keenan, S. Bullying: A culture of fear and disrespect. The Council for Children with Behavioral Disorders. 2004;18(2):1–2. [4].

37. Kielhofner, G. A scholarship of practice: Creating discourse between theory, research and practice. Occupational Therapy in Health Care. 2005;19:7–16.

38. Kohler, P.D., Field, S. Transition-focused education: Foundation for the future. Journal of Special Education. 2003;37(3):174–183.

39. Kregel, J., Dean, D.H. Sheltered work vs. supported employment: A direct comparison of long-term earnings outcomes for individuals with cognitive disabilities. In: Dregel J., Dean D.H., Wehman P., eds. Achievements and challenges in employment services for people with disabilities: The longitudinal impact of workplace supports. Richmond, VA: Virginia Commonwealth University, Rehabilitation Research and Training Center on Workplace Supports, 2002.

40. Lawhead, R.A. Hearing on opportunity for too few? Oversight of federal employment programs for people with disabilities. U.S. Senate: Testimony before the Health, Education, Labor, & Pensions Committee, 2005. [October 20, 2005].

41. Lieberman, D., Scheer, J. AOTA’s evidence-based literature review project: An overview. The American Journal of Occupational Therapy. 2002;56:344–349.

42. Lipsky, D.K., Gartner, A. Inclusion and school reform: Transforming America’s classrooms. Baltimore: Brookes, 1997.

43. Mank, D., O’Neill, C., Jansen, R. Quality in supported employment: A new demonstration of the capabilities of people with severe disabilities. Journal of Vocational Rehabilitation. 1998;11(1):83–95.

44. Marder, C., Cardoso, D., Wagner, M., Employment among youth with disabilities. Wagner M., Cadwallader T., Marder C., eds. Life outside the classroom for youth with disabilities. A report from the national longitudinal transition study-2 (NLTS2). SRI International: Menlo Park, CA, 2003:5.1–5.11. Retrieved from, www.nlts2.org/reports/2003_04-2/nlts2_report_2003_04-2_complete.pdf.

45. Martin, J.E., Van Dycke, J.L., Christensen, W.R., Greene, B.A., Gardener, J.E., Lovett, D.L. Increasing student participation in IEP meetings: Establishing the self-directed IEP as an evidence-based practice. Exceptional Children. 2006;72(3):299–316.

46. McMahan, R., Baer, R. IDEA transition policy compliance and best practice: Perceptions of transition stakeholders. Career Development for Exceptional Individuals. 2001;24:169–184.

47. Mount, B. Person-centered planning: Finding direction for change using personal futures planning, 2nd ed. New York: Graphic Features, 1997.

48. National Center for School Engagement (NCSE) What research says about family-school-community partnerships, 2005. Retrieved November 2008 from, http://www.schoolengagement.org.

49. Odom, S., Brantlinger, E., Horner, R., Thompson, B., Harris, K. Research in special education: Scientific methods and evidence-based practices. Exceptional Children. 2005;71:137–148.

50. Pugach, M.C., Johnson, L.J. Collaborative practitioners, collaborative schools. Denver CO: Love Publishing, 1995.

51. Rainforth, B., York-Barr, J. Collaborative teams for students with severe disabilities: Integrating therapy with educational services, 2nd ed. Baltimore: Brookes, 1997.

52. Revell, G., Wehman, P., Kregel, J., West, M., Rayfield, R. Funding supported employment: Are there better ways? In: Wehman P., Kregel J., West M., eds. Supported employment research: Expanding competitive employment opportunities for persons with significant disabilities. Richmond, VA: Virginia Commonwealth University Rehabilitation Research and Training Center on Supported Employment, 1994.

53. Roberton, M.A. New ways to think about old questions. In: Smith L., Thelen E., eds. A dynamic systems approach to development: Applications. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1993.

54. Sackett, D., Rosenburg, W., Gray, J., Haynes, R., Richardson, W. Evidence-based medicine: What it is and what it isn’t. British Medical Journal. 1996;31:71–72.

55. Safer, N., Fleischman, S. Research matters/How student progress monitoring improves instruction. Educational Leadership. 2005;62(5):81–83.

56. Schell, B., Schell, J. Clinical and professional reasoning in occupational therapy. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2008.