Reproductive System Concerns

• Differentiate signs and symptoms of common menstrual disorders.

• Develop a nursing care plan for a woman with primary dysmenorrhea.

• Outline client teaching about premenstrual syndrome (PMS).

• Relate the symptoms of endometriosis to the associated pathophysiology.

• Differentiate the various causes of abnormal uterine bleeding.

• Identify health risks of perimenopausal women.

• Develop an assessment guide for perimenopausal women.

• Develop a nursing plan of care for a postmenopausal woman.

• Examine the risks and benefits of menopausal hormone therapy.

• Summarize client teaching strategies for prevention of osteoporosis.

• Evaluate the use of alternative therapies for menstrual disorders and menopausal symptoms.

Problems may occur at any point in the menstrual cycle. In addition, many factors, including anatomic abnormalities, physiologic imbalances, and lifestyle, can affect the menstrual cycle. Many women seek out nurses as advisers, counselors, and health care providers for information about menstrual cycle experiences, concerns, or disorders. If they are to meet their clients’ needs, nurses must have accurate, up-to-date information. This chapter provides information on menstrual cycle experiences, including menarche and menopause; common menstrual disorders; abnormal bleeding problems; and problems associated with menopause.

Knowledge of the normal parameters of menstruation is essential to the assessment of menstrual cycle experiences and disorders. The menstrual cycle is a result of a complex interplay among the reproductive, neurologic, and endocrine systems. The hypothalamus produces gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH), which stimulates the pituitary gland to produce follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH) and luteinizing hormone (LH). In turn, FSH and LH stimulate the ovaries to produce first estrogen and then progesterone. In response to the hormones, the endometrium, or lining of the uterus, proliferates and then sheds. Chapter 4 provides additional information on the menstrual cycle and endocrine physiology.

Normal menstrual patterns are averages based on observations and reports from large groups of healthy women. When counseling an individual woman, remember that these values are averages only. Generally a woman’s menstrual frequency stabilizes at 28 days within 1 to 2 years after puberty, with a range from 26 to 34 days (Blackburn, 2007). Although no woman’s cycle is exactly the same length every month, the typical month-to-month variation in an individual’s cycle is usually plus or minus 2 days. However, greater but still normal variations are noted frequently.

During her reproductive years a woman may have more than one physiologic variation in her menstrual cycle. An understanding of the physiologic variations that occur in several age-groups is essential for nurses. Menstrual cycle length is most irregular at the extremes of the reproductive years including the 2 years after menarche and the 5 years before menopause, when anovulatory cycles are most common. Irregular bleeding, both in length of cycle and amount, is the rule rather than the exception in early adolescence. It takes approximately 15 months for completion of the first 10 cycles and an average of 20 cycles before ovulation occurs regularly. Cycle lengths of 15 to 45 days are not unusual, and during the first 2 years after menarche, intervals of 3 to 6 months between menses can be normal.

Women’s knowledge and understanding of the menstrual cycle may be limited and is often influenced by myths and misunderstandings. Women typically have menstrual cycles for about 40 years. Once the irregular nature of menses in the first 1 to 2 years after menarche subsides and a cyclic, predictable pattern of monthly bleeding is established, women may worry about any deviation from that pattern, or from what they have been told is normal for all menstruating women. A woman may be concerned about her ability to conceive and bear children or she may believe that she is not really a woman without monthly evidence. A sign such as amenorrhea or excess menstrual bleeding can be a source of severe distress and concern for women.

Common Menstrual Disorders

Amenorrhea, the absence of menstrual flow, is a clinical symptom of a variety of disorders. Although these criteria for a clinical problem of amenorrhea are not universal, these circumstances should generally be evaluated: (1) the absence of both menarche and secondary sexual characteristics by age 14 years; (2) absence of menses by age 16 years, regardless of presence of normal growth and development (primary amenorrhea); or (3) a 3- to 6-month absence of menses after a period of menstruation (secondary amenorrhea) (Speroff & Fritz, 2005).

Although amenorrhea is not a disease, it is often the sign of one. Still, most commonly and most benignly, amenorrhea is a result of pregnancy. It also may result from anatomic abnormalities such as outflow tract obstruction, anterior pituitary disorders, other endocrine disorders such as polycystic ovary syndrome, hypothyroidism or hyperthyroidism, chronic diseases such as type 1 diabetes, medications such as phenytoin (Dilantin), drug abuse (alcohol, tranquilizers, opiates, marijuana, cocaine), or oral contraceptive use.

Hypogonadotropic amenorrhea reflects a problem in the central hypothalamic-pituitary axis. In rare instances a pituitary lesion or genetic inability to produce FSH and LH is at fault. More commonly it results from hypothalamic suppression as a result of two principal influences: stress (in the home, school, or workplace) or a body fat-to-lean ratio that is inappropriate for an individual woman, especially during a normal growth period (Lobo, 2007d). Research has demonstrated a biologic basis for the relationship of stress to physiologic processes. Amenorrhea is one of the classic signs of anorexia nervosa, and the interrelatedness of disordered eating, amenorrhea, and altered bone mineral density has been described as the female athlete triad (Lebrun, 2007). Calcium loss from bone, comparable to that seen in postmenopausal women, may occur with this type of amenorrhea.

Exercise-associated amenorrhea can occur in women undergoing vigorous physical and athletic training. The pathophysiology is complex and is thought to be associated with many factors, including body composition (height, weight, and percentage of body fat); type, intensity, and frequency of exercise; nutritional status; and the presence of emotional or physical stressors (Lobo, 2007d). In addition, it is probably due to diminished secretion of GnRH. Women who participate in sports emphasizing low body weight are at greatest risk, including the following (Bonci, Bonci, Granger, Johnson, Malina, Milné, et al., 2008):

• Sports in which performance is subjectively scored (e.g., dance, gymnastics)

• Endurance sports favoring participants with low body weight (e.g., distance running, cycling)

• Sports in which body contour–revealing clothing is worn for competition (e.g., swimming, diving, volleyball)

• Sports with weight categories for participation (e.g., rowing, martial arts)

• Sports in which prepubertal body shape favors success (e.g., gymnastics, figure skating)

Assessment of amenorrhea begins with a thorough history and physical examination. An important initial step, often overlooked, is to be sure that the woman is not pregnant. Specific components of the assessment process depend on a client’s age—adolescent, young adult, or perimenopausal—and whether she has previously menstruated.

Once pregnancy has been ruled out by a β-human chorionic gonadotropin (β-hCG) pregnancy test, diagnostic tests may include FSH level, thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH) and prolactin levels, radiographic or computed tomography scan of the sella turcica, and a progestational challenge (Lobo, 2007d).

Management

When amenorrhea is a result of hypothalamic disturbances, the nurse is an ideal health professional to assist women because many of the causes are potentially reversible (e.g., stress, weight loss for nonorganic reasons). Counseling and education are primary interventions and appropriate nursing roles. When a stressor known to predispose a client to hypothalamic amenorrhea is identified, initial management involves addressing the stressor. Together the woman and the nurse plan how the woman can decrease or discontinue medications known to affect menstruation, correct weight loss, deal more effectively with psychologic stress, address emotional distress, and alter her exercise routine.

The nurse works with the woman to help her identify, cope with, and possibly resolve sources of stress in her life. Deep-breathing exercises and relaxation techniques are simple yet effective stress reduction measures. Referral for biofeedback or massage therapy also may be useful. In some instances, referrals for psychotherapy may be indicated.

If a woman’s exercise program is thought to contribute to her amenorrhea, several options exist for management. The American College of Sports Medicine (ACSM) recommends increasing nutritional intake to increase energy availability and reducing exercise energy expenditure as the first line of treatment (Nattiv, Loucks, Manore, Sandborn, Sundgot-Borgen, Warren, & ACSM, 2007). Therefore, the woman may decide to decrease the intensity or duration of her training if possible or to gain 2% to 3% in body weight. Coming to accept this alternative may be difficult for one who is committed to a strenuous exercise regimen, and the nurse and the client may have several sessions before the woman elects to try exercise reduction. Many young female athletes may not understand the consequences of low bone density or osteoporosis; nurses can point out the connection between low bone density and stress fractures. The nurse and the woman also should investigate other factors that may be contributing to the amenorrhea and develop plans for altering lifestyle and decreasing stress.

A daily calcium intake of 1000 to 1500 mg and vitamin D 400 to 600 International Units is recommended for women with amenorrhea associated with the female athlete triad (Bonci et al., 2008). Some researchers have found that low-dose oral contraceptives have a positive effect on bone density in premenopausal women with exercise-associated amenorrhea (Liu & Lebrun, 2006; Vescovi, VanHeest, & De Souza, 2008).

Cyclic Perimenstrual Pain and Discomfort

Cyclic perimenstrual pain and discomfort (CPPD) is a concept developed by a nurse science team for a research project for the Association of Women’s Health, Obstetric and Neonatal Nurses (AWHONN) (Collins Sharp, Taylor, Thomas, Killeen, & Dawood, 2002). This concept includes dysmenorrhea, premenstrual syndrome (PMS), and premenstrual dysphoric disorder (PMDD) as well as symptom clusters that occur before and after the menstrual flow starts. Symptoms occur cyclically and can include mood swings as well as pelvic pain and physical discomforts. These symptoms can range from mild to severe and can last a day or two or up to 2 weeks (Taylor, Berg, & Fogel, 2008). CPPD is a health problem that can have a significant effect on a woman’s quality of life. The following discussion focuses on the three main conditions of CPPD.

Dysmenorrhea

Dysmenorrhea, pain during or shortly before menstruation, is one of the most common gynecologic problems in women of all ages. Many adolescents have dysmenorrhea in the first 3 years after menarche. Young adult women ages 17 to 24 years are most likely to report painful menses. Approximately 75% of women report some level of discomfort associated with menses, and approximately 15% report severe dysmenorrhea (Lentz, 2007b); however, the amount of disruption in women’s lives is difficult to determine. Researchers have estimated that up to 10% of women with dysmenorrhea have severe enough pain to interfere with their functioning for 1 to 3 days a month. Severe dysmenorrhea is also associated with early menarche, nulliparity, and stress (Lentz, 2007b). Traditionally dysmenorrhea is differentiated as primary or secondary. Symptoms usually begin with menstruation, although some women have discomfort several hours before onset of flow. The range and severity of symptoms are different from woman to woman and from cycle to cycle in the same woman. Symptoms of dysmenorrhea may last several hours to several days.

Pain is usually located in the suprapubic area or lower abdomen. Women describe the pain as sharp, cramping, or gripping or as a steady dull ache; pain may radiate to the lower back or upper thighs.

Primary Dysmenorrhea

Primary dysmenorrhea, a condition associated with abnormally increased uterine activity, is due to myometrial contractions induced by prostaglandins in the second half of the menstrual cycle. During the luteal phase and subsequent menstrual flow, prostaglandin F2α (PGF2α) is secreted. The uterine muscle of both normal and dysmenorrheic women is sensitive to prostaglandins; however, the amount of prostaglandin produced is the major differentiating factor. Excessive release of PGF2α increases the amplitude and frequency of uterine contractions and causes vasospasm of the uterine arterioles, resulting in ischemia and cyclic lower abdominal cramps. Systemic responses to PGF2α include backache, weakness, sweating, gastrointestinal symptoms (anorexia, nausea, vomiting, and diarrhea), and central nervous system symptoms (dizziness, syncope, headache, and poor concentration). Pain begins at the onset of menstrual flow and lasts from 8 to 48 hours (Lentz, 2007b).

Primary dysmenorrhea is not caused by underlying pathology; rather it is the occurrence of a physiologic alteration in some women. Primary dysmenorrhea usually appears within 6 to 12 months after menarche when ovulation is established. Anovulatory bleeding, common in the few months or years after menarche, is painless. Because both estrogen and progesterone are necessary for primary dysmenorrhea to occur, it is experienced only with ovulatory cycles. This problem is most common in women in their late teens and early 20s; the incidence declines with age. Psychogenic factors may influence symptoms, but symptoms are definitely related to ovulation and do not occur when ovulation is suppressed.

Management: Management of primary dysmenorrhea depends on the severity of the problem and an individual woman’s response to various treatments. Important components of nursing care are information and support. Because menstruation is so closely linked to reproduction and sexuality, menstrual problems such as dysmenorrhea can have a negative influence on sexuality and self-worth. Nurses can correct myths and misinformation about menstruation and dysmenorrhea by providing facts about what is normal. Nurses must support their clients’ feelings of positive sexuality and self-worth.

Often more than one alternative for alleviating menstrual discomfort and dysmenorrhea can be offered. Women can then try options and decide which ones work best for them. Heat (heating pad or hot bath) minimizes cramping by increasing vasodilation and muscle relaxation and minimizing uterine ischemia. ![]() Massaging the lower back can reduce pain by relaxing paravertebral muscles and increasing pelvic blood supply. Soft rhythmic rubbing of the abdomen (effleurage) may be useful because it provides distraction and an alternative focal point. Biofeedback, transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation (TENS), progressive relaxation, Hatha yoga, acupuncture, and meditation are also used to decrease menstrual discomfort, although evidence is insufficient to determine their effectiveness (Lentz, 2007b).

Massaging the lower back can reduce pain by relaxing paravertebral muscles and increasing pelvic blood supply. Soft rhythmic rubbing of the abdomen (effleurage) may be useful because it provides distraction and an alternative focal point. Biofeedback, transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation (TENS), progressive relaxation, Hatha yoga, acupuncture, and meditation are also used to decrease menstrual discomfort, although evidence is insufficient to determine their effectiveness (Lentz, 2007b). ![]()

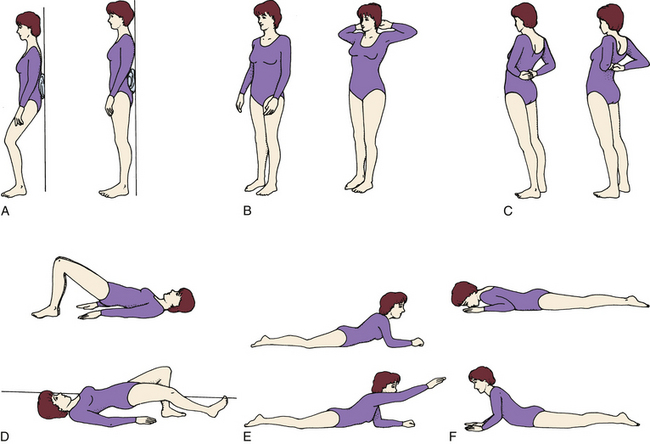

Exercise has been found to help in relieving menstrual discomfort through increased vasodilation and subsequently decreased ischemia; release of endogenous opiates, specifically beta-endorphins; suppression of prostaglandins; and shunting of blood flow away from the viscera, resulting in less pelvic congestion. A specific exercise that nurses can suggest is pelvic rocking.

In addition to maintaining good nutrition at all times, specific dietary changes may be helpful in decreasing some of the systemic symptoms associated with dysmenorrhea. Decreased salt and refined sugar intake 7 to 10 days before expected menses may reduce fluid retention. Increasing water intake may serve as a natural diuretic. Including natural diuretics such as asparagus, cranberry juice, peaches, parsley, and watermelon in the diet may help reduce edema and related discomforts. Decreasing red meat intake also may help minimize dysmenorrheal symptoms.

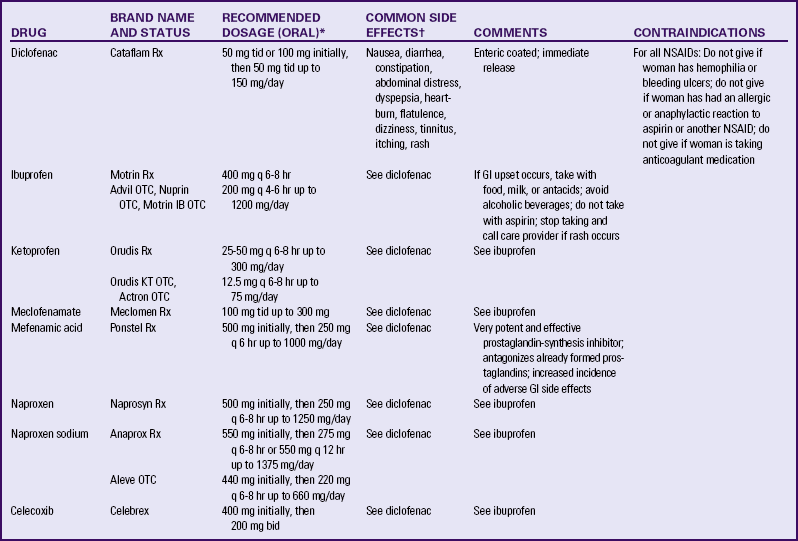

Medications used to treat primary dysmenorrhea in women not desiring contraception include prostaglandin synthesis inhibitors, primarily nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) (Lentz, 2007b) (Table 6-1). NSAIDs are effective if begun 2 to 3 days before menses or with the sign of first bleeding; this regimen decreases the possibility of a woman taking these drugs early in pregnancy (Speroff & Fritz, 2005). All NSAIDs have potential gastrointestinal side effects, including nausea, vomiting, and indigestion. All women taking NSAIDs should be warned to report dark-colored stools, because this may be an indication of gastrointestinal bleeding.

TABLE 6-1

NONSTEROIDAL ANTIINFLAMMATORY AGENTS USED TO TREAT DYSMENORRHEA

bid, Twice a day; GI, gastrointestinal; NSAIDs, nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs; OTC, over the counter; q, every; Rx, prescription; tid, three times a day.

∗Dosages are current recommendations and should be verified before use. Recommended doses for over-the-counter preparations are generally less than recommendations for therapeutic doses. As-needed dosing is recommended by manufacturer; scheduled dosing may be more effective.

†Risk with all NSAIDs is gastrointestinal ulceration, possible bleeding, and prolonged bleeding time. Incidence of side effects is dose related. Reported incidence, 1% to 10%.

Sources: Facts and Comparisons (2009). Nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs. Available at www.factsandcomparisons.com. Accessed February 15, 2010; Lentz, G. (2007b). Primary and secondary dysmenorrhea, premenstrual syndrome, and premenstrual dysphoric disorder: Etiology, diagnosis, and management. In V. Katz, G. Lentz, R. Lobo, & D. Gershenson (Eds.), Comprehensive gynecology (5th ed.). Philadelphia: Mosby; U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, U.S. Food and Drug Administration. (2008). Medication guide for non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs). Available at www.fda.gov/CDER/drug/infopage/COX2/NSAIDmedguide.htm. Accessed February 15, 2010.

OCPs prevent ovulation and can decrease the amount of menstrual flow, which can decrease the amount of prostaglandin, thus decreasing dysmenorrhea. There is evidence that combined OCPs can effectively treat dysmenorrhea (Lentz, 2007b). OCPs may be used in place of NSAIDs if the woman wants oral contraception and has primary dysmenorrhea. OCPs have side effects, and women who do not need or want them for contraception may not wish to use them for dysmenorrhea. OCPs also may be contraindicated for some women (see Chapter 8 for a complete discussion of OCPs).

Over-the-counter (OTC) preparations that are indicated for primary dysmenorrhea include the same active ingredients (e.g., ibuprofen, naproxen sodium) as prescription preparations; however, the labeled recommended dose may be subtherapeutic. Preparations containing acetaminophen are less effective because acetaminophen does not have the antiprostaglandin properties of NSAIDs.

If dysmenorrhea is not relieved by one of the NSAIDs, further investigation into the cause of the symptoms is necessary. Conditions associated with dysmenorrhea include müllerian duct anomalies, endometriosis, and pelvic inflammatory disease.

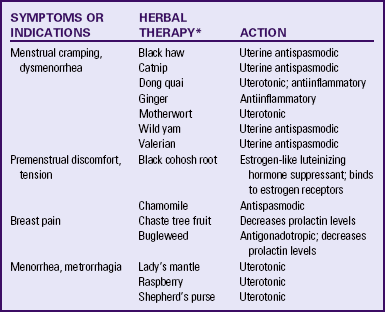

Alternative and complementary therapies are increasingly popular and used in developed countries. Therapies such as acupuncture, acupressure, biofeedback, desensitization, hypnosis, massage, Reiki, relaxation exercises, and therapeutic touch have been used to treat pelvic pain (Dehlin & Schuiling, 2006; Taylor et al., 2008).![]() Herbal preparations have long been used for management of menstrual problems including dysmenorrhea (Table 6-2). Herbal medicines may be valuable in treating dysmenorrhea; however, it is essential that women understand that these therapies are not without potential toxicity and may cause drug interactions. It is also important for women to know that research is limited about the effectiveness of use (Dehlin & Schuiling, 2006).

Herbal preparations have long been used for management of menstrual problems including dysmenorrhea (Table 6-2). Herbal medicines may be valuable in treating dysmenorrhea; however, it is essential that women understand that these therapies are not without potential toxicity and may cause drug interactions. It is also important for women to know that research is limited about the effectiveness of use (Dehlin & Schuiling, 2006).![]()

Secondary Dysmenorrhea

Secondary dysmenorrhea is acquired menstrual pain that develops later in life than primary dysmenorrhea, typically after age 25 years. This condition is associated with pelvic pathology, such as adenomyosis, endometriosis, pelvic inflammatory disease, endometrial polyps, or submucous or interstitial myomas (fibroids). Women with secondary dysmenorrhea often have other symptoms that may suggest an underlying cause. For example, heavy menstrual flow with dysmenorrhea suggests a diagnosis of leiomyomata, adenomyosis, or endometrial polyps. Pain associated with endometriosis often begins a few days before menses, but can be present at ovulation and continue through the first days of menses or start after menstrual flow has begun. In contrast to primary dysmenorrhea, the pain of secondary dysmenorrhea is often characterized by dull, lower abdominal aching radiating to the back or thighs. Often women experience feelings of bloating or pelvic fullness. In addition to a physical examination with a careful pelvic examination, diagnosis may be assisted by ultrasound examination, dilation and curettage, endometrial biopsy, or laparoscopy. Treatment is directed toward removal of the underlying pathology. Many of the measures described for pain relief of primary dysmenorrhea also are helpful for women with secondary dysmenorrhea.

Premenstrual Syndrome and Premenstrual Dysphoric Disorder

Approximately 30% to 80% of women experience mood or somatic symptoms (or both) that occur with their menstrual cycles (Lentz, 2007b). Establishing a universal definition of premenstrual syndrome (PMS) is difficult, given that so many symptoms have been associated with the condition, and at least two different syndromes have been recognized: PMS and premenstrual dysphoric disorder (PMDD).

PMS is a complex, poorly understood condition that includes one or more of a large number (more than 100) of physical and psychologic symptoms beginning in the luteal phase of the menstrual cycle, occurring to such a degree that lifestyle or work is affected, and followed by a symptom-free period. Symptoms include fluid retention (abdominal bloating, pelvic fullness, edema of the lower extremities, breast tenderness, and weight gain); behavioral or emotional changes (depression, crying spells, irritability, panic attacks, and impaired ability to concentrate); premenstrual cravings (sweets, salt, increased appetite, and food binges); and headache, fatigue, and backache.

All age-groups are affected, with women in their 20s and 30s most frequently reporting symptoms. Ovarian function is necessary for the condition to occur because it does not occur before puberty, after menopause, or during pregnancy. The condition is not dependent on the presence of monthly menses: women who have had a hysterectomy without bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy (BSO) still can have cyclic symptoms.

PMDD is a more severe variant of PMS in which 3% to 8% of women have marked irritability, dysphoria, mood lability, anxiety, fatigue, appetite changes, and a sense of feeling overwhelmed (Lentz, 2007b). The most common symptoms are those associated with mood disturbances.

A diagnosis of PMS is made when the following criteria are met (American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists [ACOG], 2000; AWHONN, 2003):

• Symptoms consistent with PMS occur in the luteal phase and resolve within a few days of menses onset.

• Symptom-free period occurs in the follicular phase.

• Symptoms have a negative effect on some aspect of a woman’s life.

• Other diagnoses that better explain the symptoms have been excluded.

For a diagnosis of PMDD, the following criteria must be met (American Psychiatric Association [APA], 2000):

• Five or more affective and physical symptoms are present in the week before menses and are absent in the follicular phase of the menstrual cycle.

• At least one of the symptoms is irritability, depressed mood, anxiety, or emotional lability.

• Symptoms interfere markedly with work or interpersonal relationships.

• Symptoms are not caused by an exacerbation of another condition or disorder.

These criteria must be confirmed by prospective daily ratings for at least two menstrual cycles.

The causes of PMS and PMDD are not known, but there is general agreement that they are distinct psychiatric and medical syndromes rather than an exacerbation of an underlying psychiatric disorder. They do not occur if there is no ovarian function. A number of biologic and neuroendocrine etiologies have been suggested; however, none have been conclusively substantiated as the causative factor. It is likely that biologic, psychosocial, and sociocultural factors contribute to PMS and PMDD (Lentz, 2007b; Taylor, Schuiling, & Sharp, 2006). Readers are encouraged to explore current feminist, medical, and social science literature for more information on PMS.

Management

There is little agreement on management. A careful, detailed history and daily log of symptoms and mood fluctuations spanning several cycles may give direction to a plan of management. Any changes that assist a woman with PMS to exert control over her life have a positive effect. For this reason, lifestyle changes are often effective in the treatment of PMS.

Education is an important component of the management of PMS. Nurses can advise women that self-help modalities often result in significant symptom improvement. Women have found a number of complementary and alternative therapies to be useful in managing the symptoms of PMS. Nurses can suggest that women:

• Not smoke and limit their consumption of refined sugar (less than 5 tablespoons/day), salt (less than 3 g/day), red meat (up to 3 ounces/day), alcohol (less than 1 ounce/day), and caffeinated beverages.

• Include whole grains, legumes, seeds, nuts, vegetables, fruits, and vegetable oils in their diet.

• Eat three small to moderate-sized meals and three small snacks a day that are rich in complex carbohydrates and fiber (Lentz, 2007b).

• Use natural diuretics (see section on dysmenorrhea management on p. 121) to help reduce fluid retention.

Nutritional supplements can assist in symptom relief. Calcium (1000 to 1200 mg daily), magnesium (300 to 400 mg daily), and vitamin B6 (100 to 150 mg daily) have been shown to be moderately effective in relieving symptoms, to have few side effects, and to be safe. Daily supplements of evening primrose oil are reportedly useful in relieving breast symptoms with minimal side effects, but research reports are conflicting (Taylor et al., 2008). Other herbal therapies have long been used to treat PMS; see Table 6-2 for specific suggestions.![]()

Regular exercise (aerobic exercise three or four times a week), especially in the luteal phase, is widely recommended for relief of PMS symptoms (Lentz, 2007b). A monthly program that varies in intensity and type of exercise according to PMS symptoms is best. Women who exercise regularly seem to have less premenstrual anxiety than do nonathletic women. Researchers believe aerobic exercise increases beta-endorphin levels to offset symptoms of depression and elevate mood.

Yoga, acupuncture, hypnosis, light therapy, chiropractic therapy, and massage therapy have all been reported to have a beneficial effect on PMS. ![]() Further research is needed for all of these suggested therapies.

Further research is needed for all of these suggested therapies.

Nurses can explain the relation between cyclic estrogen fluctuation and changes in serotonin levels, that serotonin is one of the brain chemicals that assist in coping with normal life stresses, and the ways in which the different management strategies recommended help maintain serotonin levels. Support groups or individual or couples counseling may be helpful. Stress reduction techniques also may assist with symptom management (Lentz, 2007b; Taylor et al., 2008).

If these strategies do not provide significant symptom relief in 1 to 2 months, medication is often begun. Many medications have been used in treatment of PMS, but no single medication alleviates all PMS symptoms. Medications often used in the treatment of PMS include diuretics, prostaglandin inhibitors (NSAIDs), progesterone, and OCPs. Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) such as fluoxetine (Prozac or Sarafem), sertraline (Zoloft), and paroxetine (Paxil CR) are approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) as agents for PMS. Use of these medications results in a decrease in emotional premenstrual symptoms, especially depression (Lentz, 2007b). Common side effects are headaches, sleep disturbances, dizziness, weight gain, dry mouth, and decreased libido (see Nursing Care Plan: Premenstrual Syndrome).

Endometriosis

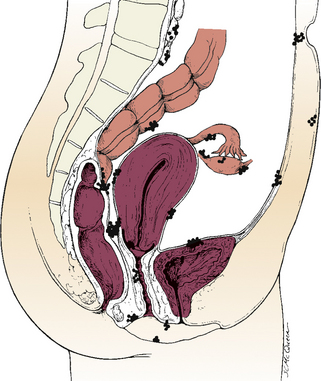

Endometriosis is characterized by the presence and growth of endometrial glands and stroma outside of the uterus. The tissue may be implanted on the ovaries; the anterior and posterior cul-de-sac; the broad, uterosacral, and round ligaments; the uterine tubes; the rectovaginal septum; the sigmoid colon; the appendix; the pelvic peritoneum; the cervix; and the inguinal area (Fig. 6-1). Endometrial lesions have been found in the vagina and on surgical scars, as well as on the vulva, the perineum, and the bladder, and sites far from the pelvic area such as the thoracic cavity, the gallbladder, and the heart. A chocolate cyst is a cystic area of endometriosis in the ovary. Old blood causes the dark coloring of the cyst’s contents.

FIG. 6-1 Common sites of endometriosis. (Lobo, R. [2007b]. Endometriosis. In V. Katz, G. Lentz, R. Lobo, & D. Gershenson [Eds.], Comprehensive gynecology [5th ed.]. Philadelphia: Mosby.)

Endometrial tissue contains glands and stoma and responds to cyclic hormonal stimulation in the same way that the uterine endometrium does. During the proliferative and secretory phases of the cycle, the endometrial tissue grows. During or immediately after menstruation, the tissue bleeds, resulting in an inflammatory response with subsequent fibrosis and adhesion to adjacent organs.

Endometriosis is a common gynecologic problem, affecting from 6% to 10% of women of reproductive age (Lobo, 2007b). Although the condition usually develops in the third or fourth decade of life, endometriosis is being diagnosed more frequently in adolescents with disabling pelvic pain or abnormal vaginal bleeding (Templeman, 2009). The condition is found equally in Caucasian and African-American women, is slightly more prevalent in Asian women, and may have a familial tendency for development (Lobo). Endometriosis may worsen with repeated cycles, or it may remain asymptomatic and undiagnosed, eventually disappearing after menopause.

Several theories have been offered to account for the cause of endometriosis, yet the causes and pathologic features of this condition are poorly understood. One of the most widely accepted, long-debated theories is transtubal migration or retrograde menstruation. According to this theory, endometrial tissue is regurgitated or mechanically transported from the uterus during menstruation to the uterine tubes and into the peritoneal cavity, where it implants on the ovaries and other organs.

Symptoms vary among women, from nonexistent to incapacitating. Severity of symptoms can change over time and may be disproportionate to the extent of the disease. The major symptoms of endometriosis are pelvic pain, dysmenorrhea, dyspareunia (painful intercourse), abnormal menstrual bleeding, and infertility. Women also may experience chronic noncyclic pelvic pain, pelvic heaviness, or pain radiating to the thighs. Many women report bowel symptoms such as diarrhea, pain with defecation, and constipation caused by avoiding defecation because of the pain. Less common symptoms include abnormal bleeding (hypermenorrhea, menorrhagia, or premenstrual staining) and pain during exercise as a result of adhesions (Lobo, 2007b).

Women who have endometriosis can have fibromyalgia, chronic fatigue syndrome, endocrine disorders, and autoimmune disorders (Tietjen, Bushnell, Herial, Utley, White, & Hafeez, 2007).

Impaired fertility may result from adhesions around the uterus that pull the uterus into a fixed, retroverted position. Adhesions around the uterine tubes may block the fimbriated ends or prevent the spontaneous movement that carries the ovum to the uterus.

Management

Treatment is based on the severity of symptoms and the goals of the woman or couple. Women without pain who do not want to become pregnant need no treatment. Women with mild pain who may desire a future pregnancy may use NSAIDs for pain relief. Women who have severe pain and can postpone pregnancy may be treated with continual OCPs that have a low estrogen-to-progestin ratio to shrink endometrial tissue. However, when this therapy stops, women often experience high rates of pain recurrence and other symptoms.

Hormonal antagonists that suppress ovulation and reduce endogenous estrogen production and subsequent endometrial lesion growth are used to treat mild to severe endometriosis in women who wish to become pregnant at a future time. GnRH agonist therapy (leuprolide, nafarelin [Synarel], goserelin acetate [Zoladex]) acts by suppressing pituitary gonadotropin secretion. FSH and LH stimulation to the ovary declines noticeably, and ovarian function decreases significantly. The hypoestrogenism results in hot flashes in almost all women. In addition, minor bone loss sometimes occurs, most of which is reversible within 12 to 18 months after the medication is stopped. Leuprolide (3.75-mg intramuscular injection given once a month) or nafarelin (200 mcg administered twice daily by nasal spray) are effective and well tolerated. Both medications reduce endometrial lesions and pelvic pain associated with endometriosis and have posttreatment pregnancy rates similar to that of danazol therapy (Lobo, 2007b). Common side effects of these drugs are similar to those of natural menopause—hot flashes and vaginal dryness. Some women report headaches and muscle aches.

Danazol (Danocrine), a mildly androgenic synthetic steroid, suppresses FSH and LH secretion, thus producing anovulation with resulting decreased secretion of estrogen and progesterone and regression of endometrial tissue. Bothersome side effects include masculinizing traits in the woman—weight gain, edema, decreased breast size, oily skin, hirsutism, and deepening of the voice—all of which often disappear when treatment is discontinued. Other side effects are amenorrhea, hot flashes, vaginal dryness, insomnia, and decreased libido. Some women report migraine headaches, dizziness, fatigue, and depression. In addition, some women experience decreases in bone density that are only partially reversible. Danazol should never be prescribed when pregnancy is suspected, and contraception should be used with it because ovulation may not be suppressed. Danazol can produce pseudohermaphroditism in female fetuses. The drug is contraindicated in women with liver disease and should be used with caution in women with cardiac and renal disease (Lobo, 2007b).

Administration of NSAIDs and continuous combined hormonal therapy (oral contraceptive pills, estrogen/progestin patch, estrogen/progestin vaginal ring) for menstrual suppression are the usual treatment of adolescents younger than the age of 16 who have endometriosis. GnRH agonists are not usually used because the resultant hypoestrogenic state can affect bone mineralization (ACOG Committee on Adolescent Health Care, 2005).

Surgical intervention is often needed for severe, acute, or incapacitating symptoms. A woman’s age, desire for children, and location of the disease influence decisions regarding the extent and type of surgery. For women who do not want to preserve their ability to have children, the only definite cure is hysterectomy and BSO (total abdominal hysterectomy [TAH] with BSO). In women who are in their childbearing years and who want children if the disease does not prevent pregnancy, surgery or laser therapy is used to carefully remove as much endometrial tissue as possible to maintain reproductive function (Lobo, 2007b).

Short of TAH with BSO, endometriosis recurs in approximately 40% to 50% of women, regardless of the form of treatment. Therefore, for many women, endometriosis is a chronic disease with conditions such as chronic pain or infertility. Counseling and education are critical components of nursing care of women with endometriosis. Women need an honest discussion of treatment options with potential risks and benefits of each option reviewed. Because pelvic pain is a subjective, personal experience that can be frightening, support is important. Sexual dysfunction resulting from dyspareunia may be present and may necessitate referral for counseling. Some locations have support groups for women with endometriosis; Resolve (www.resolve.org), an organization for infertile couples, or the Endometriosis Association (www.ivf.com/endohtml.html) also may be helpful. The nursing care measures discussed in the section on dysmenorrhea are appropriate for managing chronic pelvic pain associated with endometriosis (see Nursing Care Plan: Endometriosis).

Alterations in Cyclic Bleeding

Women often experience changes in amount, duration, interval, or regularity of menstrual cycle bleeding. Commonly, women worry about menstruation that is infrequent or scanty, is excessive, or occurs between periods.

Oligomenorrhea/Hypomenorrhea

The term oligomenorrhea often is used to describe decreased menstruation, either in amount, time, or both. However, oligomenorrhea more correctly refers to infrequent menstrual periods characterized by intervals of 40 to 45 days or longer, and hypomenorrhea to scanty bleeding at normal intervals. The causes of oligomenorrhea are often abnormalities of hypothalamic, pituitary, or ovarian function. Oligomenorrhea also can be physiologic, or part of a woman’s normal pattern for the first few years after menarche or for several years before menopause.

Treatment is aimed at reversing the underlying cause, if possible. Hormonal therapy using progestins, with or without estrogens, also may be used to prevent complications of unopposed estrogen production (endometrial hyperplasia or carcinoma) or of absent estrogen (vaginal dryness, hot flashes or flushes, or osteoporosis).

Women with menstruation characterized by prolonged intervals between cycles need education and counseling. The cause of the condition and the rationale for a specific treatment should be discussed, as should advantages and disadvantages of hormonal therapy. If a woman chooses medical intervention, she should be provided with written instructions, taught how to take the medications, and made aware of side effects of any medications. Teaching and counseling should emphasize the importance of the woman keeping careful records of her vaginal bleeding.

One of the most common causes of scanty menstrual flow is OCPs. If a woman is considering OCPs for contraception, it is important to explain in advance that the use of OCPs can decrease menstrual flow by as much as two thirds. This effect is caused by the continuous action of the progestin component, which produces a decidualized endometrium with atrophic glands.

Hypomenorrhea also may be caused by structural abnormalities of the endometrium or the uterus that result in partial destruction of the endometrium. These conditions include Asherman syndrome, in which adhesions resulting from curettage or infection obliterate the endometrial cavity, and congenital partial obstruction of the vagina.

Metrorrhagia

Metrorrhagia, or intermenstrual bleeding, refers to any episode of bleeding, whether spotting, menses, or hemorrhage, that occurs at a time other than the normal menses. Mittlestaining, a small amount of bleeding or spotting that occurs at the time of ovulation (14 days before onset of the next menses), is considered normal. The cause of mittlestaining is not known;

however, its common occurrence can be documented by its repetition in the menstrual cycle.

Women taking OCPs may have midcycle bleeding or spotting. (See Chapter 8 for a discussion of the side effects of OCPs.) If the OCP does not maintain a sufficiently hypoplastic endometrium, the endometrium will begin to shed, usually in small amounts at a time, a process termed breakthrough bleeding. Breakthrough bleeding is most common in the first three cycles of OCPs. The reduced potency of OCPs (resulting in increased safety) has decreased the amount of available hormones, making it more important that blood levels be kept constant. Taking the pill at exactly the same time each day may alleviate the woman’s problem. If the spotting continues, a different formulation of the OCP that increases either the estrogen or progestin component of the pill can be tried.

Progestin-only contraceptive methods (oral and injectable) also may cause midcycle bleeding, especially in the first several cycles. Women should be advised of this and counseled to report continuation of breakthrough bleeding after the first three to six cycles to their health care provider.

Women with an intrauterine device (IUD) may have spotting between their periods and possibly heavier menstrual flow.

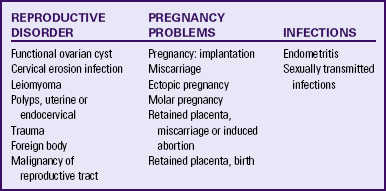

The causes of intermenstrual bleeding are varied (Table 6-3). It is important that the nurse always consider the possibility that any woman who has not undergone menopause and who seeks care for intermenstrual bleeding is or recently has been pregnant.

Treatment of intermenstrual bleeding depends on the cause and may include reassurance and education concerning mittlestaining, observation of three menstrual cycles for suspected functional ovarian cyst, adjustment of an OCP, removal of foreign bodies, and treatment for vaginal infections. More complex treatment may consist of removal of polyps; evaluation and treatment of an abnormal Papanicolaou (Pap) test, including colposcopy, biopsy, cautery, cryosurgery, or conization; and surgery, chemotherapy, or radiation treatment for malignancy. Important nursing roles include reassurance, counseling, education, and support.

Menorrhagia

Menorrhagia (hypermenorrhea) is defined as excessive menstrual bleeding, in either duration or amount. The causes of heavy menstrual bleeding are many, including hormonal disturbances, systemic disease, benign and malignant neoplasms, infection, and contraception (IUDs). A single episode of heavy bleeding may occur, or a woman may have regular flooding as a pattern in which she changes tampons or pads every few hours for several days.

Hemoglobin and hematocrit provide objective indicators to actual blood loss and should always be assessed.

A single episode of heavy bleeding may signal an early pregnancy loss. This type of bleeding is often thought to be a period that is heavier than usual, perhaps delayed, and is associated with abdominal pain or pelvic discomfort. When early pregnancy loss is suspected, a hematocrit and serum β-hCG pregnancy test should be done.

Infectious and inflammatory processes such as acute or chronic endometritis and salpingitis may cause heavy menstrual bleeding. Although rare, systemic diseases of nonreproductive origin such as blood dyscrasias, hypothyroidism, and lupus erythematosus also can cause hypermenorrhea. In obese women anovulation caused by increased peripheral conversion of androstenedione to estrogen may develop and manifest as menorrhagia. Medications also may cause abnormal bleeding. Chemotherapy, anticoagulants, neuroleptics, and steroid hormone therapy all have been associated with excessive flow.

Uterine leiomyomata (fibroids or myomas) are a common cause of menorrhagia. Fibroids are benign tumors of the smooth muscle of the uterus, the etiology of which is unknown. Fibroids are estrogen sensitive and commonly develop during the reproductive years and shrink after menopause. Other uterine growths ranging from endometrial polyps to adenocarcinoma and endometrial cancer are other common causes of heavy menstrual bleeding, as well as of intermenstrual bleeding.

Treatment for menorrhagia depends on the cause of the bleeding. If the bleeding is related to the contraceptive method, the nurse provides factual information and reassurance and discusses other contraceptive options. If bleeding is related to the presence of fibroids, the degree of disability and discomfort associated with the fibroids and the woman’s plans for childbearing will influence treatment decisions. Treatment options include medical and surgical management. Most fibroids can be monitored by frequent examinations to judge growth, if any, and correction of anemia, if present. Women with menorrhagia should be warned not to use aspirin because of its tendency to increase bleeding. Medical treatment is directed toward temporarily reducing symptoms, shrinking the myoma, and reducing its blood supply (Katz, 2007). This reduction is often accomplished with the use of a GnRH agonist. If the woman wishes to retain childbearing potential, a myomectomy may be done. Myomectomy, or removal of the tumors only, is particularly difficult if multiple myomas must be removed. If the woman does not want to preserve her childbearing function, or if she has severe symptoms (severe anemia, severe pain, considerable disruption of lifestyle), hysterectomy or endometrial ablation (laser surgery or electrocoagulation) may be done (see Chapter 11). Uterine artery embolization, based on the assumption that control of arterial blood flow to the fibroid will control symptoms, has been reported to result in reduced menorrhagia, less dysmenorrhea, and reduced pelvic pressure and urinary symptoms. This method of treatment is used for women who have completed their childbearing since there is a risk for loss of fertility (see Chapter 11).

Dysfunctional Uterine Bleeding

Abnormal uterine bleeding (AUB) is any form of uterine bleeding that is irregular in amount, duration, or timing and not related to regular menstrual bleeding. Box 6-1 lists possible causes of AUB. Although often used interchangeably, the terms AUB and dysfunctional uterine bleeding (DUB) are not synonymous. Dysfunctional uterine bleeding is a subset of AUB defined as “excessive uterine bleeding with no demonstrable organic cause, genital or extragenital” (Lobo, 2007a). DUB is most frequently caused by anovulation. When there is no surge of LH, or if insufficient progesterone is produced by the corpus luteum to support the endometrium, it will begin to involute and shed. This process most often occurs at the extremes of a woman’s reproductive years—when the menstrual cycle is just becoming established at menarche or when it draws to a close at menopause. DUB also can be found with any condition that gives rise to chronic anovulation associated with continuous estrogen production. Such conditions include obesity, hyperthyroidism and hypothyroidism, polycystic ovary syndrome, and any of the endocrine conditions discussed in the sections on amenorrhea and oligomenorrhea. A diagnosis of DUB is made only after all other causes of abnormal menstrual bleeding have been ruled out (Lentz, 2007a).

When uterine bleeding is profuse and a woman’s hemoglobin level is less than 8 g/dl (hematocrit of 23% or 24%), the woman may be hospitalized and given conjugated estrogens (e.g., Premarin), 25 mg intravenously. The dose may be repeated until bleeding stops or slows significantly (usually within 1 to 5 hours) (Behera & Price, 2009). If the bleeding has not stopped in 12 to 24 hours, dilation and curettage (D&C) may be done to control severe bleeding and hemorrhage. An endometrial biopsy may be collected at the same time to evaluate endometrial tissue or rule out endometrial cancer. After this treatment, oral conjugated estrogen, 2.5 mg, is given daily followed by the addition of progesterone (e.g., medroxyprogesterone [Provera], 10 mg by mouth), given in the final 10 days of therapy to initiate withdrawal bleeding. Alternatively, a combined OCP is given for 21 days after intravenous therapy. Once the acute phase has passed, the woman is maintained on cyclic low-dose OCPs for 3 to 6 months. Such long-term treatment will help prevent recurrence of the pattern of dysfunctional uterine bleeding and hemorrhage. If the woman wants contraception, she should continue to take OCPs. If the woman has no need for contraception, the treatment may be stopped to assess her bleeding pattern. If menstruation does not resume, a progestin regimen (e.g., medroxyprogesterone, 10 mg/day for 10 days before the expected date of her menstrual period) may be prescribed after ruling out pregnancy. This is done to prevent persistent anovulation with chronic unopposed endogenous estrogen hyperstimulation of the endometrium, which can result in eventual atypical tissue changes (Lobo, 2007a).

If the recurrent, heavy bleeding is not controlled by hormonal therapy or D&C, ablation of the endometrium through laser treatment may be performed. Nursing roles include counseling and educating women about their options as needed and referring women to the appropriate specialists and health care services.

Menopause

With the increasing life span of American women, most women can expect to live one third of their lives after their reproductive years. As women age many experience transitions that present challenges and require adaptation such as changing health, work, or marital status. Nowhere is this more true than with the changes associated with menopause. In the United States, most women have menopause during their late 40s and early 50s, with the median age being 51 to 52 years (Lobo, 2007c). The average age for the onset of the perimenopausal transition is 46 years; 95% of women experience the onset between ages 39 and 51. The average duration of the perimenopause period is 4 to 5 years, with 95% of women postmenopausal by age 58 (Lobo). Cigarette smoking and a history of short intermenstrual intervals seem to decrease the age at onset of menopause. African-American and Hispanic women in the United States experience menopause earlier than Caucasian women. However, heredity is the major determinant of age at menopause; genetics may explain most of the variation in menopause age (Lobo).

Perimenopause is the period that encompasses the transition from normal ovulatory cycles to cessation of menses and is marked by irregular menstrual cycles. Another term used to signal the period when a woman moves from the reproductive stage of life through the perimenopausal transition and menopause to the postmenopausal years is the climacteric. Menopause refers to the complete cessation of menses and is a single physiologic event said to occur when women have not had menstrual flow or spotting for 1 year, and it can be identified only in retrospect. Surgical menopause occurs with hysterectomy and bilateral oophorectomy. Postmenopause is the time after menopause.

Although all women have similar hormonal changes with menopause, the experience of each woman is influenced by her age, cultural background, health, type of menopause (spontaneous or surgical), childbearing desires, and relationships. Women may view menopause as a major change in their lives—either positive, such as freedom from troublesome dysmenorrhea or the need for contraception, or negative, such as feeling “old” or losing childbearing possibilities.

Physiologic Characteristics

Knowledge of the normal changes that occur during the perimenopause is essential to the assessment of menopausal experiences and problems. Natural menopause is a gradual process with progressive increases in anovulatory cycles and eventual cessation of menses. In the 2 to 8 years preceding menopause, subtle hormonal changes eventually lead to altered menstrual function and later to amenorrhea. When women are in their 40s, anovulation occurs more often, menstrual cycles increase in length, and ovarian follicles become less sensitive to hormonal stimulation from FSH and LH. Because of these changes, a follicle is stimulated to the point that an ovum grows to maturity and is released in some months, whereas in other months, no ovulation takes place. Without ovulation and release of an ovum, progesterone is not produced by the corpus luteum. The lining continues to grow until it lacks a sufficient blood supply, at which point it will bleed. During this time a woman’s cycle will become more irregular. She may skip or miss periods; have shorter or lighter periods or longer, heavier periods; and have clotting. FSH levels become elevated, reflecting an attempt to stimulate a follicle to produce estrogen.

Physical Changes During the Perimenopausal Period

During the perimenopausal years, women may have longer menstrual periods that differ in the type of bleeding. They may have 2 to 3 days of spotting followed by 1 to 2 days of heavy bleeding, or they may have regular menses followed by 2 to 3 days of spotting. Such symptoms are characteristic of degenerating corpus luteum function. After menopause women continue to have small amounts of circulating estrogen. Although the ovaries do not produce estrogen, androgens (androstenedione and testosterone) are produced for some time after menopause. Androgens produced by the adrenal glands are converted to estrone, a form of estrogen, in the liver and fat cells. With advanced age the ovaries stop producing androstenedione, which further limits the amount of estrone in the body. Obese women are more likely to have dysfunctional uterine bleeding and endometrial hyperplasia because women with more body fat have higher circulating levels of estrone. This occurs because the estrogen that is stored in the fat cells of the body is converted into a form of estrogen (estrone) that is available to the estrogen receptors within the endometrium.

Genital Changes

The vagina and urethra are estrogen-sensitive tissues, and low levels of estrogen can cause atrophy of both. Age-related vaginal changes not affected by estrogen also occur. Through both processes the vaginal membranes thin, hold less moisture, and lubricate more slowly. However, not all women have symptoms of genital atrophy. Women who are sexually active have less vaginal atrophy and fewer problems related to intercourse. Thin women are more likely to have more symptoms related to reduced estrogen levels such as vaginal dryness because of lack of adipose tissue and thus stored estrogen. Additionally, vaginal pH increases, lactobacillus growth can be depressed, and other bacteria tend to multiply. This combination of factors can lead to vaginitis.

Dyspareunia (painful intercourse) can occur because the vagina becomes smaller, the vaginal walls become thinner and drier, and lubrication during sexual stimulation takes longer. Intercourse becomes painful and may result in postcoital bleeding. Some women may decide to forgo intercourse altogether.

In some women the shrinking of the uterus, the vulva, and the distal portion of the urethra associated with aging leads to disturbing symptoms, including urinary frequency, dysuria, uterine prolapse, and stress incontinence. Vaginal relaxation with cystocele, rectocele, and uterine prolapse is not caused by reduced estrogen levels but may be a delayed result of childbearing or other cause of weakness of pelvic support structures. Urinary frequency sometimes occurs after menopause because the distal portion of the urethra, which has the same embryologic origin as the reproductive organs, shortens and shrinks. Irritants have easier access to the urinary tract with its shorter urethra and may cause frequency and urinary tract infections.

Urinary incontinence and uterine displacement are two other common age-related rather than menopause-related findings in the postmenopausal period. These conditions are discussed in Chapter 11.

Vasomotor Instability

During the past three decades investigators have devoted significant attention to identifying ovarian, hypothalamic, and pituitary hormonal mechanisms that produce symptoms related to menopause. Two symptoms appear to increase in incidence as women progress through menopause: hot flashes and night sweats. Many of the other changes commonly associated with menopause, such as decrease in size of genital structures, skin changes, and changes in breast size, are more correctly attributed to aging.

Vasomotor instability in the form of hot flashes or flushes is a result of fluctuating estrogen levels and is the most common disturbance of the perimenopausal years, occurring in up to 75% of women having natural menopause and 90% of women who have a surgical menopause. In the United States, Hispanic and African-American women report a higher incidence of these symptoms than Caucasian women; Asian women have the lowest incidence (Lobo, 2007c). Vasomotor instability occurs most frequently in the first 2 postmenopausal years; the number of episodes decreases over time. However, some women have hot flashes before menopause and continue to have them for 10 or more years afterward. During this time women experience changeable vasodilation and vasoconstriction as a hot flush (visible red flush of skin and perspiration) or hot flash (sudden warm sensation in neck, head, and chest) and night sweats. These disturbances vary widely in severity, and only about 40% of women seek health care for them (Nedrow, Miller, Walker, Nygren, Huffman, & Nelson, 2006). For some women hot flashes may be an infrequent, possibly pleasant, sensation of warmth; for others, they may be an intensely unpleasant sensation of heat or warmth that may occur 20 to 50 times a day, create intense anxiety, and significantly decrease quality of life. Several factors can precipitate or aggravate an episode, including crowded or warm rooms, alcohol, hot drinks, spicy foods, proximity to a heat source, and stress.

Night sweats, characterized by profuse perspiration and heat radiating from the body during the night, are another form of vasomotor instability experienced by many women. Sleep may be interrupted nightly because nightclothes and bed linens may be soaked. Women may find that they are not able to go back to sleep. Sleep deprivation is a primary complaint of women experiencing hot flashes (Lobo, 2007c). Other problems that may be associated with perimenopausal fluctuations of vasoconstriction or vascular spasms include dizziness, numbness and tingling in fingers and toes, and headaches.

Mood and Behavioral Responses

The tendency to associate hormonal changes with psychologic symptoms in midlife that has been prevalent in medical literature for decades and continues today was fueled by a belief that postmenopausal women have “estrogen deficiency.” Contrary to this common belief, there is no concrete evidence that menopause has a deleterious effect on mental health of midlife women. Reviews of epidemiologic studies on menopause and depression found no causal association between menopause and depression (Lobo, 2007c). Women with hot flashes and night sweats do report insomnia, fatigue from loss of sleep, and depressed mood. Women complain of feeling more emotionally labile, nervous, or agitated, with less control of their emotions. However, the interaction of psychologic, biologic, and sociocultural factors is so complex that it is difficult to determine whether a woman’s reported mood shifts are the result of hormonal changes, normal aging, or cultural conditioning. Most likely a woman’s psychologic makeup, cultural background, intercurrent stresses, and changing life roles and circumstances are more important than estrogen levels. Dealing with teenage children; having teenagers leave home; helping aging parents; becoming widowed or divorced; the onset of a major illness or disability (even death) in a spouse, relative, or friend; grieving for friends and family who are ill or dying; retirement; and financial insecurity are among the many stresses of women in their 40s and 50s.

Cultural messages also influence a woman’s perception of menopause. Women’s experiences with menopause are not universal and vary among cultural groups. Most North American women do not believe that menopause interferes with their quality of life (National Institutes of Health [NIH], 2005). Women do not find symptoms to be a cause for concern; however, they do report that symptoms are bothersome. Many women have accepted childbearing and child rearing as their major role in life, and the inability to bear children is a significant loss. Others see menopause as the first step to old age and associate it with a loss of attractiveness, physical ability, and energy. Western culture values youth and physical attractiveness; the wisdom gained from life experience is not valued, and older adults have a loss of status, function, and role. No rituals give older women a special place and function. In cultures where postmenopausal women gain status, such as India, the Far East, and the South Pacific islands, depression among menopausal women is not observed. Western women, however, may have little to compensate for their losses.

For other women, menopause is not a loss or a symbol of losses, but a relief. For some, menopause is a relief from the fear of pregnancy, the discomfort and bother of menstruation, and the inconveniences of contraception.

The ability to cope with any stress involves three factors: the person’s perception or understanding of the event, the support system, and coping mechanisms. Nurses counseling women in their perimenopausal years must therefore assess their understanding of perimenopausal changes, their perceptions of stressful experiences, their support systems, and their repertoire of coping skills.

Health Risks of Perimenopausal Women

Osteoporosis and coronary heart disease are the major health risks of perimenopausal women and the focus of the following discussion.

Osteoporosis

Aging is associated with a progressive decrease in bone density in men and women. Osteoporosis is a generalized, metabolic disease characterized by decreased bone mass and increased incidence of bone fractures. Normally there is a dynamic balance between bone formation (osteoblastic activity) and bone resorption (osteoclastic activity). Because one of the functions of estrogen is to stimulate the osteoblasts, the postmenopausal decrease in estrogen levels causes an imbalance between bone formation and resorption. Old bone deteriorates faster than new bone is formed, resulting in a slow thinning of the bones. Estrogen also is required for the conversion of vitamin D into calcitonin, which is essential in the absorption of calcium by the intestine. Reduced calcium absorption from the gut, in addition to the thinning of the bones, places postmenopausal women at risk for problems associated with osteoporosis.

Osteoporosis is a major health problem in the United States, affecting more than 8 million women older than 45 years (National Osteoporosis Foundation [NOF], 2010). Approximately 50% of U.S. women have some degree of osteoporosis. One in two Caucasian women will have changes severe enough to predispose them to fractures. In the United States, the incidence of osteoporosis-related fractures has increased in the past 20 years. Postmenopausal women with a hip or symptomatic vertebral fracture have a 25% increased risk of death in the year following their fracture. After a hip fracture 25% of women will need long-term care and 50% will have long-term loss of mobility (North American Menopause Society [NAMS], 2010b). During the first 5 to 6 years after menopause, women lose bone six times more rapidly than men. By age 65, one third of women have had a vertebral fracture; by age 81, one third have had a hip fracture. By the time women reach age 80, they have lost 47% of their trabecular bone, concentrated in the vertebrae, the pelvis and other flat bones, and the epiphyses. The most well-defined risk factor for osteoporosis is the loss of the protective effect of estrogen associated with cessation of ovarian function, particularly at menopause. Women at risk are likely to be Caucasian or Asian, small boned, and thin. Obese women have higher estrogen levels resulting from the conversion of androgens in adipose tissue; mechanical stress from extra weight also helps preserve bone mass. A family history of the disease is common. The influences of heredity, race, and sex may result in differences in peak bone mass (NOF, 2010).

Inadequate calcium intake is a risk factor, particularly during adolescence and into the third and fourth decades, when peak bone mass is attained. An excessive caffeine intake increases calcium excretion, causing a systemic acidosis that stimulates bone resorption. Vitamin D deficiency can affect the physiologic regulation and stimulation of intestinal absorption of calcium (NOF, 2010). Smoking is associated with earlier and greater bone loss and decreases estrogen production. Excessive alcohol intake interferes with calcium absorption and depresses bone formation. A greater phosphorus than calcium intake, which occurs with soft drink consumption, may be a risk factor. Other risk factors include steroid therapy and disorders such as hypogonadism, hyperthyroidism, and diabetes mellitus (NOF).

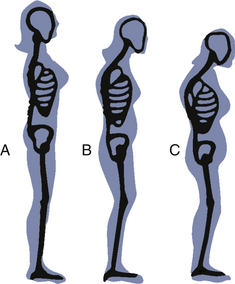

The first sign of osteoporosis is often loss of height resulting from vertebral fracture and collapse (Fig. 6-2). Back pain, especially in the lower back, may or may not be present. Later signs include “dowager’s hump,” in which the vertebrae can no longer support the upper body in an upright position, and fractured hip, in which the fracture often precedes a fall. Damage to the vertebrae usually precedes bone loss in the hip by an average of 10 years. Osteoporosis cannot be detected by radiographic examination until 30% to 50% of the bone mass has been lost; thus routine screening is not warranted in women younger than age 65. However, bone density testing is recommended for women at high risk for osteoporosis at age 60 and for all women older than 65 to assess fracture risk (NOF, 2010; U.S. Public Health Services Task Force, 2002). Medicare will pay for tests for high risk women once every 2 years (NOF, 2008). Insurance reimbursement for the tests varies among insurance carriers and from state to state.

FIG. 6-2 Skeletal changes secondary to osteoporosis assessed by height and body shape at A, age 55 years; B, age 65 years; and C, age 75 years.

Coronary Heart Disease

A woman’s risk of developing and dying of cardiovascular disease increases after menopause. Diseases of the heart are the leading cause of death for women in the United States. The lifetime risk is 31% versus 3% for breast cancer in postmenopausal women (Lobo, 2007c). Known risk factors for coronary heart disease include obesity, cigarette smoking, elevated cholesterol and blood pressure levels, diabetes mellitus, family history of cardiac disease, alcohol abuse, and the effects of aging on the cardiovascular system (Cunningham, 2008; Lobo). Estrogen has a favorable effect on circulating lipids, decreasing low-density lipoprotein (LDL) and total cholesterol and increasing high-density lipoprotein (HDL), and has a direct antiatherosclerotic effect on arteries. Postmenopausal women are at risk for coronary artery disease because of changes in lipid metabolism: a decline in serum levels of HDL cholesterol and an increase in LDL levels (Lobo). These changes can be favorably reduced by diet and exercise.

Menopausal Hormonal Therapy

Until 2002 menopausal hormonal therapy (MHT)—either as estrogen replacement therapy (ERT) or estrogen therapy (ET), in which a woman takes only estrogen, or hormonal replacement therapy (HRT) or hormonal therapy (HT), in which she takes both estrogen and progestins—was widely prescribed for discomforts associated with the perimenopausal years, including hot flashes and vaginal and urinary tract atrophy. Further, MHT was aggressively used for therapeutic and preventive management. At the same time its use remained highly controversial in women’s health. Some authorities recommended HT or ET for all women; these proponents viewed the perimenopause as a disease or deficiency state. Others insisted that the use of hormones was never indicated for menopausal symptoms. The middle-ground approach advocated the use of MRT for women who have specific discomforts (therapeutic management) and for women in certain high risk groups (preventive management). Research studies challenged these beliefs in the preventive and beneficial effects of HT. Findings from the Women’s Health Initiative, a study by the National Institutes of Health, documented increased risks for blood clots, heart attack, stroke, and invasive breast cancer in older women with a uterus (mean age 63, range 50 to 79 years) with long-term use of continuous combined estrogen plus progestin (Kaunitz, 2002; Rossouw, Anderson, Prentice, LaCroix, Kooperberg, Stefanick, et al., 2002).

These findings changed the way MHT is used. Many women stopped taking MHT and sought alternative therapies to treat their menopausal symptoms. Others chose to continue with the MHT but had questions about the available regimens and associated risks. Although the absolute risk for these adverse outcomes in an individual woman is very low, menopausal women should be aware of the most current research to make an informed decision regarding if, when, and for how long they use MHT.

Decision to Use Hormone Therapy

All women considering ET or HT must understand that studies on MHT are ongoing, and there is still much to be learned. Nurses can provide information and counseling to assist women to make decisions regarding MHT use. Important teaching points include the following (National Women’s Health Information Center, 2006 [www.4women.gov]; NAMS, 2010a [www.menopause.org]; Santoro & Steunkel, 2009):

• For women taking MHT for short-term (1 to 3 years) relief of menopausal discomforts and who do not have increased risks for cardiovascular disease, the benefits may outweigh the risks. The decision to use MRT should be made between a woman and her health care provider.

• If used, MHT should be taken at the lowest effective dose for the shortest possible duration.

• When a woman decides to stop MHT, a recurrence of symptoms will occur whether the medication is tapered or discontinued abruptly. NAMS makes no recommendation on how to discontinue the medication, although some clinicians recommend a gradual withdrawal.

• Older women who are taking or considering MHT only for the prevention of cardiovascular disease should be counseled on other methods to reduce their risks of cardiovascular disease.

• Alternatively there may be beneficial cardiovascular effects associated with MHT for younger, more recently menopausal women, but research is needed.

• Women who are taking MHT only for prevention of osteoporosis should be counseled regarding their personal risks and benefits for continuing the therapy and reassured that there are effective alternatives for long-term prevention. Bone density studies also may be indicated to determine the degree of risk in an individual woman.

• Women with a high risk for breast cancer or who have had breast cancer should be counseled against using MHT.

• Conjugated estrogens are associated with an increased incidence of gallbladder disease, and women with a known history of gallbladder disease should not use MHT.

Nurses are encouraged to stay current with ongoing MHT research findings. As other Women’s Health Initiative (WHI) data on MHT are analyzed, further clarification of the issues will be published.

Side Effects

Side effects associated with estrogen use include headaches, nausea and vomiting, bloating, ankle and feet swelling, weight gain, breast soreness, brown spots on the skin, eye irritation with contact lenses, and depression. The type of estrogen used for postmenopausal hormonal therapy is much less potent than ethinyl estradiol used in OCPs and has fewer serious side effects. Side effects that occur with MHT may disappear with a change in estrogen preparation or a decrease in the dose prescribed.

Treatment Guidelines

Research in MHT continues; however, nurses who counsel women about MHT must understand what is available and teach women who choose to continue MHT how to take the medications correctly. Thus the following discussion about the different regimens of MHT is included.

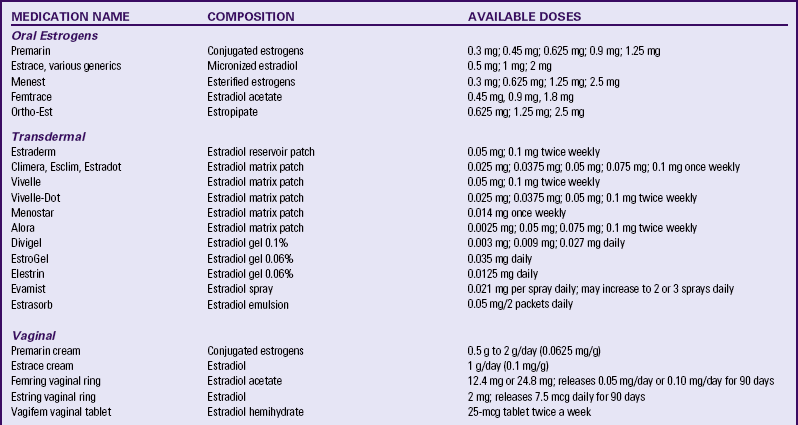

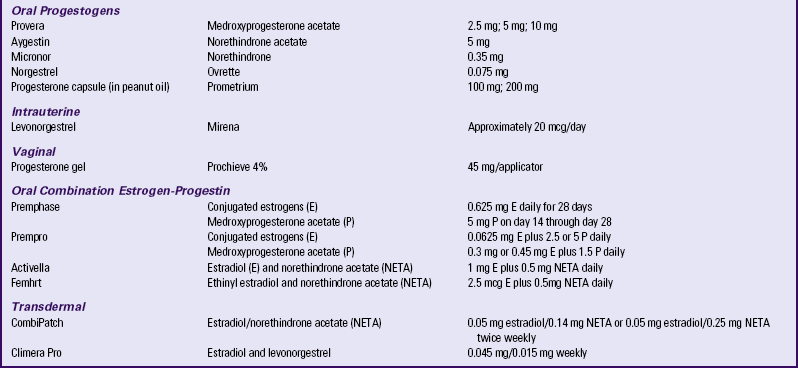

Many different estrogen preparations, natural and synthetic, and ways of administering them—oral tablets, topical creams, transdermal preparations, suppositories, and vaginal rings—exist (Table 6-4). However, most women today in the United States use tablets (Carroll, 2010).

TABLE 6-4

HORMONE MEDICATIONS FOR MENOPAUSAL SYMPTOMS

Source: North American Menopause Society. (2009). Hormone products for postmenopausal use in the United States and Canada. Available at www.menopause.org. Accessed March 1, 2010.

There are multiple dosing regimen options for combining progesterone with estrogen for women who have a uterus. According to NAMS (2010a), there is insufficient research to recommend one regimen over another; however, there is evidence to recommend keeping exposure to progesterone at a minimum. An oral continual-cyclic regimen that is most commonly prescribed is estrogen on days 1 to 28 and a progestogen (e.g., medroxyprogesterone) on days 14 to 28. Women usually do not have cyclic bleeding with this regimen and are less likely to have progestin side effects. There are also multiple regimen options for ET for women who have had a hysterectomy.

The transdermal estrogen patch is applied once or twice a week to a hairless area of skin. Transdermal gels and sprays are applied daily. Any site on the trunk or upper arms provides adequate absorption. Sites should be rotated. The patches should not be placed on the breasts because of their sensitivity. Some women report minor skin irritation and reddening at the patch site. Generally transdermal estrogen offers the same relief of menopausal symptoms as the oral preparation. The transdermal method of delivery of estrogen does not have the same side effects such as breast tenderness and fluid retention. Oral progestin therapy can be used with transdermal ET. Combined estrogen-progestin transdermal patches also are available.

Vaginal creams and tablets are inserted daily or twice a week. Usually these local administrations of low-dose estrogen are used for vaginal symptoms of dryness and atrophy. Vaginal rings are inserted and left in place for 90 days. Although minimal systemic absorption is possible, there are no reports of adverse effects when a low dose is used (NAMS, 2010a).

Bioidentical and Custom-Compounded Hormones

Bioidentical hormones, sometimes referred to as natural hormones, are structurally identical to those produced by the ovary. Bioidentical hormone preparations are available as government approved well-tested brand-name prescription medications. Others are made at compounding pharmacies. Custom-compounded hormones are custom mixes of one or more hormones in varying amounts. These mixes can provide individualized doses and mixtures of hormones that are not available commercially. They also include ingredients that are nonhormonal (e.g., dyes, preservatives). The risks are that these mixtures have not been studied to confirm whether appropriate absorption occurs or if predictable levels can be detected in blood and tissue (NAMS, 2006). Preparations may vary from one pharmacy to another, meaning that a woman may not get consistent amounts of medication. These preparations are not approved by any regulatory agency (NAMS, 2010a). Although these hormones may relieve menopausal symptoms, more research is needed to determine their effects on the body. Women who choose to take these hormones need to understand and accept the potential risks. Expense is also an issue because these drugs often are more expensive and are not covered by third-party payers.

Alternative Therapies

Many complementary and alternative therapies are useful for relieving some of the changes associated with altered estrogen levels. Homeopathy, acupuncture, and herbs have been used with varying degrees of success for menopausal problems such as heavy bleeding, hot flashes, irritability, and headaches.

Homeopathy views menopausal symptoms as the body’s efforts to heal itself from the hormonal changes it is experiencing. Examples of remedies commonly prescribed during menopause by homeopaths are sepia, made from the inky juice of the cuttlefish, to relieve symptoms such as dry mouth, eyes, and vagina; nux vomica, derived from the poison nut, to relieve backaches, constipation, and frequent awakenings; and pulsatilla, made from the windflower, to relieve severe menstrual symptoms and hot flashes. Homeopathic remedies are subject to regulation by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA), although the FDA does not require proof of effectiveness. Most studies have not proven homeopathy to be any more effective than a placebo for relieving menopausal symptoms (Martin, Pinkerton, & Santen, 2009).![]()