Nursing Care of the Family During the Postpartum Period

• Describe components of a systematic postpartum assessment.

• Recognize signs of potential complications in the postpartum woman.

• Identify common selection criteria for safe early postpartum discharge.

• Formulate a nursing care plan for a woman in the postpartum period.

• Explain the influence of cultural beliefs and practices on postpartum care.

• Identify psychosocial needs of the woman in the early postpartum period.

• Prepare a plan for postpartum teaching for self-management.

• Describe the nurse’s role in these postpartum follow-up strategies: home visits, telephone follow-up, warm lines and help lines, support groups, and referrals to community resources.

![]() http://evolve.elsevier.com/Lowdermilk/MWHC/

http://evolve.elsevier.com/Lowdermilk/MWHC/

Audio Glossary

Case Study

Critical Thinking Exercise

NCLEX Review Questions

Video—Nursing Skills

At no other time is family-centered maternity care more important than in the postpartum period. Nursing care is provided in the context of the family unit and focuses on assessment and support of the woman’s physiologic and emotional adaptation after birth. During the early postpartum period, components of nursing care include assisting the mother with rest and recovery from the process of labor and birth, assessment of physiologic and psychologic adaptation after birth, prevention of complications, education regarding self-management and infant care, and support of the mother and her partner during the initial transition to parenthood. In addition, the nurse considers the needs of other family members and includes strategies in the nursing care plan to assist the family in adjusting to the new baby.

The approach to the care of women after birth is wellness oriented. In the United States most women remain hospitalized no more than 1 or 2 days after vaginal birth, and some for as few as 6 hours. Because so much important information needs to be shared with these women in a very short time, their care must be thoughtfully planned and provided. This chapter discusses nursing care of the woman and her family in the postpartum period extending into the fourth trimester—the first 3 months after birth.

Transfer from the Recovery Area

After the initial recovery period has been completed, and provided that her condition is stable, the woman may be transferred to a postpartum room in the same or another nursing unit. In facilities with labor, delivery, recovery, postpartum (LDRP) rooms, the woman is not moved and the nurse who provides care during the recovery period usually continues caring for the woman. In many settings, women who have received general or regional anesthesia must be cleared for transfer from the recovery area by a member of the anesthesia care team. In other settings, a nurse makes the determination.

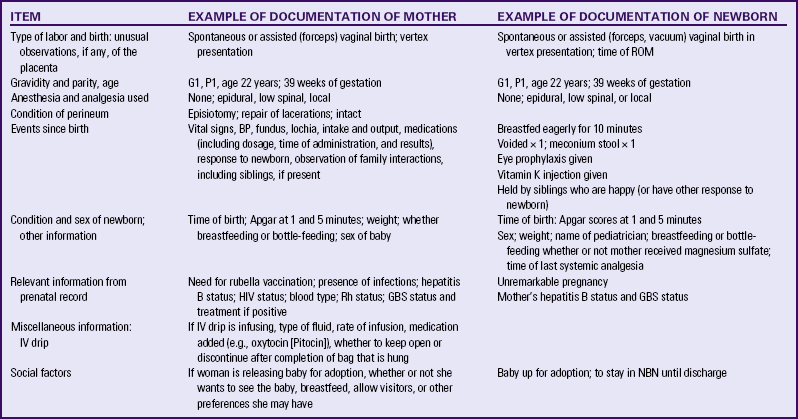

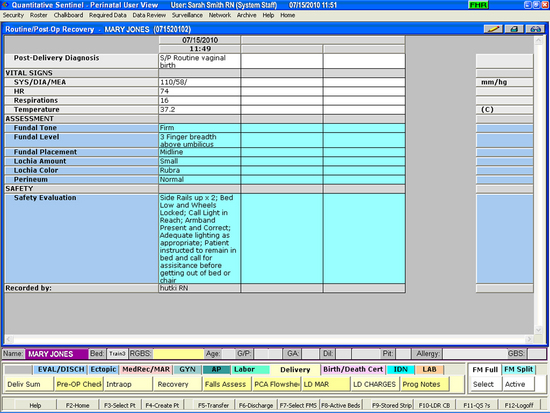

In preparing the transfer report, the recovery nurse uses information from the records of admission, birth, and recovery (Fig. 21-1). Information that must be communicated to the postpartum nurse includes identity of the health care provider; gravidity and parity; age; anesthetic used; any medications given; duration of labor and time of rupture of membranes; whether labor was induced or augmented; type of birth and repair; blood type and Rh status; group B streptococci (GBS) status; status of rubella immunity; human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) and hepatitis B serology test results; other infections identified during pregnancy (e.g., syphilis, gonorrhea, chlamydia), and whether these were treated; intravenous infusion of any fluids; physiologic status since birth; description of fundus, lochia, bladder, and perineum; sex and weight of infant; time of birth; chosen method of feeding; any abnormalities noted; and assessment of initial parent-infant interaction.

FIG. 21-1 Portion of a vaginal birth recovery screen in an electronic record. (Courtesy Kitty Cashion, Memphis, TN.)

Most of this information is also documented for the nursing staff in the newborn nursery if the infant is transferred to that unit (in some settings, the newborn never leaves the mother’s room). In addition, specific information should be provided regarding the newborn’s Apgar scores (see Chapter 24), weight, voiding, stooling, whether fed since birth, and the name of the pediatric care provider. Nursing interventions that have been completed (e.g., eye prophylaxis, vitamin K injection) as well as identification procedures done (e.g., footprints, armbands) must be recorded.

Table 21-1 gives examples for documenting this information before the transfer of the woman from the recovery area.

Planning for Discharge

From their initial contact with the postpartum woman, nurses prepare the new mother for the time when she will return home. The length of hospital stay after giving birth depends on many factors, including the physical condition of the mother and the newborn, mental and emotional status of the mother, social support at home, client education needs for self-management and infant care, and financial constraints.

Women who give birth in birthing centers may be discharged within a few hours, after the woman’s and infant’s conditions are stable. Mothers and newborns who are at low risk for complications may be discharged from the hospital within 24 to 36 hours after vaginal birth. This short time frame is often called early postpartum discharge, shortened hospital stay, and 1-day maternity stay. The trend of shortened hospital stays is based largely on efforts to reduce health care costs coupled with consumer demands to have less medical intervention and more family-focused experiences. Although there are advantages to early postpartum discharge, disadvantages also exist (Box 21-1).

Laws Relating to Discharge

Health care providers have expressed concern with shortened stays because some medical problems do not show up in the first 24 hours after birth. The greatest risk associated with early discharge is for the infant who may develop jaundice, feeding difficulties, infection, or unrecognized respiratory or cardiac problems (Cargill, Martel, & Society of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists of Canada, 2007). In addition, new mothers may not have had sufficient time to learn how to care for their newborns, and breastfeeding may not be well established. The concern for the potential increase in adverse maternal-infant outcomes from hospital early-discharge practices led the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG), the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP), and other professional health care organizations in the U.S. to promote the enactment of federal and state maternity length-of-stay bills to ensure adequate care for mother and newborn. The passage of the Newborns’ and Mothers’ Health Protection Act of 1996 provided minimum federal standards for health plan coverage for mothers and their newborns. Under this act, all health plans are required to allow the new mother and newborn to remain in the hospital for a minimum of 48 hours after a normal vaginal birth and for 96 hours after a cesarean birth unless the attending provider, in consultation with the mother, decides on early discharge (AAP Committee on Fetus and Newborn, 2004).

Criteria for Discharge

Early discharge with postpartum home care can be a safe and satisfying option for women and their families when the plan is comprehensive and based on individual needs (AAP Committee on Fetus and Newborn, 2004) and when follow-up takes place (see Box 21-1). Effective follow-up within 72 hours after discharge can significantly decrease infant readmissions and maternal postpartum depression (Goulet, D’Amour, & Pineault, 2007).

Ideally, hospital stays are long enough to identify problems and ensure that the woman is sufficiently recovered and is prepared to care for herself and the baby at home. Nurses must consider the medical needs of the woman and her baby and provide care that is coordinated to meet those needs so as to provide timely physiologic interventions and treatment to prevent morbidity and hospital readmission.

Hospital-based maternity nurses continue to play invaluable roles as caregivers, teachers, and advocates for mothers, newborn, and families in developing and implementing effective home-care strategies. Postpartum order sets and maternal-newborn teaching checklists can be used to accomplish client care tasks and educational outcomes. With coordination, clinical care and education can be planned and provided throughout pregnancy, during the hospital stay, and in the home after discharge to ensure the family’s continued well-being.

Care Management: Physical Needs

The nursing care plan includes both the postpartum woman and her newborn, even if the nursery nurse retains primary responsibility for the infant. In many hospitals, couplet care (also called mother-baby care or single-room maternity care) is practiced. Nurses in these settings have been educated in both mother and infant care and function as primary nurses for both mother and infant, even if the infant is kept in the nursery. This approach is a variation of rooming-in, in which the mother and infant room together and mother and nurse share the care of the infant. The organization of the mother’s care must take the newborn into consideration. The day actually revolves around the baby’s feeding and care times (see Nursing Process: Postpartum Physical Concern).

Ongoing Physical Assessment

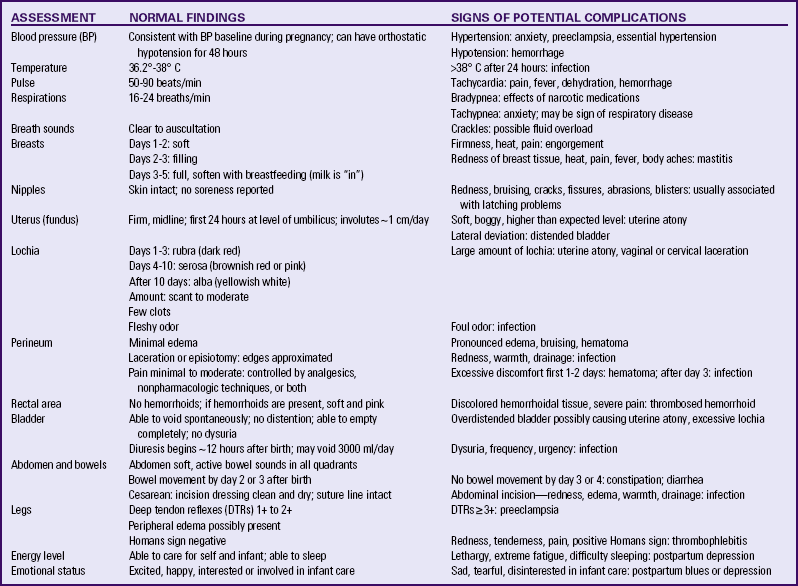

Ongoing assessments are performed throughout hospitalization. In addition to vital signs, physical assessment of the postpartum woman focuses on evaluation of the breasts, uterine fundus, lochia, perineum, bladder and bowel function, vital signs, and legs (Table 21-2).

Routine Laboratory Tests

Several laboratory tests may be performed in the immediate postpartum period. Hemoglobin and hematocrit values are often evaluated on the first postpartum day to assess blood loss during childbirth, especially after cesarean birth. In some hospitals a clean-catch or catheterized urine specimen may be obtained and sent for routine urinalysis or culture and sensitivity, especially if an indwelling urinary catheter was inserted during the intrapartum period. In addition, if the woman’s rubella and Rh status are unknown, tests to determine her status and need for possible treatment should be performed at this time.

Nursing Interventions

Once the nursing diagnoses are formulated, the nurse plans with the woman what nursing measures are appropriate and which are to be given priority. The nursing care plan includes periodic assessments to detect deviations from normal physical changes, measures to relieve discomfort or pain, safety measures to prevent injury and infection, and teaching and counseling measures designed to promote the woman’s feelings of competence in self-management and infant care. The spouse or partner and other family members who are present can be included in the teaching. The nurse evaluates continually and is ready to change

the plan if indicated. Almost all hospitals use standardized care plans or care paths as a basis for planning. Nurses individualize care of the postpartum woman and neonate according to their specific needs (see the Nursing Care Plan). Signs of potential problems that may be identified during the assessment process are listed in Table 21-2.

Nurses assume many roles while implementing the nursing care plan. They provide direct physical care, teach mother-baby care, and provide anticipatory guidance and counseling. Perhaps most important, they nurture the woman by providing encouragement and support as she begins to assume the many tasks of motherhood. Nurses who take the time to “mother the mother” do much to increase feelings of self-confidence in new mothers.

The first step in providing individualized care is to confirm the woman’s identity by checking her wristband. At the same time, the infant’s identification number is matched with the corresponding band on the mother’s wrist, and in some instances the father’s or partner’s wrist. The nurse determines how the mother wishes to be addressed, then notes her preference in her record and in her nursing care plan.

The woman and her family are oriented to their surroundings. Familiarity with the unit, routines, resources, and personnel reduces one potential source of anxiety—the unknown. The mother is reassured through knowing whom and how she can call for assistance and what she can expect in the way of supplies and services. If the woman’s usual daily routine before admission differs from the facility’s routine, the nurse works with the woman to develop a mutually acceptable routine.

Infant abduction from hospitals in the United States has increased over the past several years. As a result, many units have special limited-entry systems. Nurses teach mothers to check the identity of any person who comes to remove the baby from their room. Hospital personnel usually wear picture identification badges. On some units all staff members wear matching scrubs or special badges. Other units use closed-circuit television, computer monitoring systems, or fingerprint identification pads. As a rule, the infant is never carried in a staff member’s arms between the mother’s room and the nursery but is always wheeled in a bassinet, which also contains baby care supplies. New mothers and nurses must work together to ensure the safety of newborns in the hospital environment.

Prevention of Infection

Nurses in the postpartum setting are acutely aware of the importance of preventing infection in their clients. One important means of preventing infection is by maintaining a clean environment. Bed linens should be changed as needed. Disposable pads and draw sheets are changed frequently. Women should wear slippers when walking about to prevent contamination of the linens when they return to bed. Personnel must be conscientious about their hand hygiene to prevent cross-infection. Standard Precautions must be practiced. Staff members with colds, coughs, or skin infections (e.g., a cold sore on the lip [herpes simplex virus, type 1]) must follow hospital protocol when in contact with postpartum women. In many hospitals, staff members with open herpetic lesions, strep throat, conjunctivitis, upper respiratory infections, or diarrhea are encouraged to avoid contact with mothers and infants by staying home until the condition is no longer contagious. Visitors with signs of illness are not permitted to enter the postpartum unit.

Perineal lacerations and episiotomies can increase the risk of infection as a result of interruption in skin integrity. Proper perineal care helps prevent infection in the genitourinary area and aids the healing process. Educating the woman to wipe from front to back (urethra to anus) after voiding or defecating is a simple first step. In many hospitals a squeeze bottle filled with warm water or an antiseptic solution is used after each voiding to cleanse the perineal area. The woman should change her perineal pad from front to back each time she voids or defecates and wash her hands thoroughly before and after doing so (Box 21-2).

Prevention of Excessive Bleeding

A moderate amount of vaginal bleeding (lochia) is expected in the immediate postpartum period. Nurses need to assess and prevent excessive bleeding, the most frequent cause of which is uterine atony, failure of the uterine muscle to contract firmly. The two most important interventions for preventing excessive bleeding are maintaining good uterine tone and preventing bladder distention. If uterine atony occurs, the relaxed uterus distends with blood and clots, blood vessels in the placental site are not clamped off, and excessive bleeding results. Although the cause of uterine atony is not always clear, it often results from retained placental fragments.

Excessive blood loss after childbirth can also be caused by vaginal or vulvar hematomas or unrepaired lacerations of the vagina or cervix. These potential sources might be suspected if excessive vaginal bleeding occurs in the presence of a firmly contracted uterus.

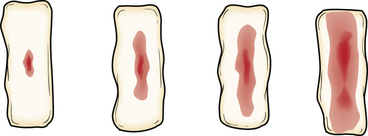

Accurate visual estimation of blood loss is an important nursing responsibility. Blood loss is usually described subjectively as scant, light, moderate, or heavy (profuse). Figure 21-2 shows examples of perineal pad saturation corresponding to each of these descriptions.

FIG. 21-2 Blood loss after birth is assessed by the extent of perineal pad saturation as (from left to right) scant (<2.5 cm), light (<10 cm), moderate (>10 cm), or heavy (one pad saturated within 2 hours).

Although postpartal blood loss may be estimated by observing the amount of staining on a perineal pad, judging the amount of lochial flow is difficult if based only on observation of perineal pads. More objective estimates of blood loss include measuring serial hemoglobin or hematocrit values; weighing blood clots and items saturated with blood (1 mL equals 1 g); and establishing how many milliliters are required to saturate perineal pads being used. In general nurses tend to overestimate, rather than underestimate, blood loss.

Any estimation of lochial flow is inaccurate and incomplete without consideration of the time factor. The woman who saturates a perineal pad in 1 hour or less is bleeding much more heavily than the woman who saturates one perineal pad in 8 hours.

Different brands of perineal pads vary in their saturation volume and soaking appearance. For example, blood placed on some brands tends to soak down into the pad, whereas on other brands it tends to spread outward. Nurses should determine saturation volume and soaking appearance for the brands used in their institution so that they may improve accuracy of blood loss estimation.

When excessive bleeding occurs, vital signs are monitored closely. Blood pressure is not a reliable indicator of impending shock from early postpartum hemorrhage because compensatory mechanisms prevent a significant drop in blood pressure until the woman has lost 30% to 40% of her blood volume (see Chapter 34). Respirations, pulse, skin condition, urinary output, and level of consciousness are more sensitive means of identifying shock (see the Emergency box). The frequent physical assessments performed during the fourth stage of labor are designed to provide prompt identification of excessive bleeding. Nurses maintain vigilance for excessive bleeding throughout the hospital stay as they perform periodic assessment of the uterine fundus and lochia.

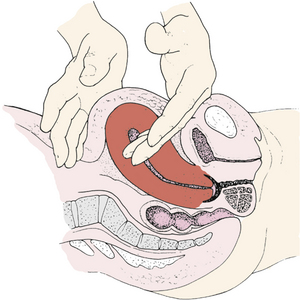

Maintenance of Uterine Tone: A major intervention to alleviate uterine atony and restore uterine muscle tone is stimulation by gently massaging the fundus until firm (Fig. 21-3). Fundal massage can cause a temporary increase in the amount of vaginal bleeding seen as pooled blood leaves the uterus. Clots can also be expelled. The uterus can remain boggy even after massage and expulsion of clots.

FIG. 21-3 Palpating fundus of uterus during the postpartum period. Note that upper hand is cupped over fundus; lower hand dips in above symphysis pubis and supports uterus while it is massaged gently.

Fundal massage can be a very uncomfortable procedure. If the nurse explains the purpose of fundal massage as well as the causes and dangers of uterine atony, the woman will likely be more cooperative. Teaching the woman to massage her own

fundus enables her to maintain some control and decreases her anxiety.

When uterine atony and excessive bleeding occur, additional interventions likely to be used are administration of intravenous fluids and oxytocic medications (drugs that stimulate contraction of the uterine smooth muscle). (See Medication Guide in Chapter 34 for information about common oxytocic medications.)

Prevention of Bladder Distention: Uterine atony and excessive bleeding after birth can be the result of bladder distention. A full bladder causes the uterus to be displaced above the umbilicus and well to one side of midline in the abdomen. It also prevents the uterus from contracting normally.

Women may be at risk of bladder distention resulting from urinary retention based on intrapartum factors. These risk factors include epidural anesthesia, episiotomy, extensive vaginal or perineal lacerations, instrument-assisted birth, or prolonged labor. Women who have had indwelling catheters, such as with cesarean birth, may experience some difficulty as they initially attempt to void after the catheter is removed. Nurses who are aware of these risk factors can be proactive in preventing complications.

Nursing interventions for a postpartum woman focus on helping the woman to empty her bladder spontaneously as soon as possible. The first priority is to assist the woman to the bathroom or onto a bedpan if she is unable to ambulate. Having the woman listen to running water, placing her hands in warm water, or pouring water from a squeeze bottle over her perineum may stimulate voiding. Other techniques include assisting the woman into the shower or sitz bath and encouraging her to void; relaxation techniques can also be helpful. Administering analgesics, if ordered, may be indicated because some women fear voiding because of anticipated pain. If these measures are unsuccessful, a sterile catheter may be inserted to drain the urine.

Promotion of Comfort, Rest, Ambulation, and Exercise

Comfort: Most women experience some degree of discomfort during the postpartum period. Common causes of discomfort include pain from uterine contractions (afterpains), perineal lacerations or episiotomy, hemorrhoids, sore nipples, and breast engorgement. Women likely to experience the greatest perineal discomfort are those who had forceps- or vacuumassisted operative birth, and those who have an episiotomy (Declercq, Cunningham, Johnson, & Sakala, 2008). Multiparous and breastfeeding women have the most discomfort from afterpains.

The woman’s description of the location, type, and severity of her pain is the best guide in choosing an appropriate intervention. To confirm the location and extent of discomfort, the nurse inspects and palpates areas of pain as appropriate for redness, swelling, discharge, and heat and observes for body tension, guarded movements, and facial tension. Blood pressure, pulse, and respirations may be elevated in response to acute pain. Diaphoresis may accompany severe pain. A lack of objective signs does not necessarily mean there is no pain because there can be a cultural component to the expression of pain. Nursing interventions are intended to eliminate the pain sensation entirely or reduce it to a tolerable level that allows the woman to care for herself and her baby. Nurses may use nonpharmacologic and pharmacologic interventions to promote comfort. Pain relief is enhanced by using more than one method or route.

Nonpharmacologic Interventions: A variety of nonpharmacologic measures is used to reduce postpartum discomfort. ![]() These include distraction, imagery, therapeutic touch, relaxation, acupressure, aromatherapy, hydrotherapy, massage therapy, music therapy, and transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation (TENS).

These include distraction, imagery, therapeutic touch, relaxation, acupressure, aromatherapy, hydrotherapy, massage therapy, music therapy, and transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation (TENS).

For women who are experiencing discomfort associated with uterine contractions, application of warmth (e.g., heating pad) or lying prone may be helpful. Interaction with the infant may also provide distraction and decrease this discomfort. Because afterpains are more severe during and after breastfeeding, the timing of interventions are planned to provide the most timely and effective relief.

Simple interventions that can decrease the discomfort associated with an episiotomy or perineal lacerations include encouraging the woman to lie on her side whenever possible. Other interventions include application of an ice pack; topical application (if ordered) of anesthetic spray or cream; dry heat; cleansing with water from a squeeze bottle; and a cleansing shower, tub bath, or sitz bath. Many of these interventions are also effective for hemorrhoids, especially ice packs, sitz baths, and topical applications (such as witch hazel pads). Box 21-2 gives additional specific information about these interventions.

Sore nipples in breastfeeding mothers are most likely related to ineffective latch technique. Assessment and assistance with feeding can help alleviate the cause. To ease discomfort associated with sore nipples the mother may apply topical preparations such as purified lanolin or hydrogel pads (see Chapter 25).

Breast engorgement can occur whether the woman is breastfeeding or formula feeding. The discomfort associated with engorged breasts may be reduced by applying ice packs or cabbage leaves (or both) to the breasts, and wearing a well-fitted support bra. Antiinflammatory medications can also be helpful in relieving some of the discomfort. Decisions about specific interventions for engorgement are based on whether the woman chooses breastfeeding or bottle-feeding (see Chapter 25).

Pharmacologic Interventions: Pharmacologic interventions are commonly used to relieve or reduce postpartum discomfort. Most health care providers routinely order a variety of analgesics to be administered as needed, including both narcotic and nonnarcotic (e.g., nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs [NSAIDs]). In some hospitals NSAIDs are administered on a scheduled basis, especially if the woman had perineal repair. Topical application of antiseptic or anesthetic ointment or spray can be used for perineal pain. Patient-controlled analgesia (PCA) pumps and epidural analgesia are commonly used to provide pain relief after cesarean birth.

Many women want to participate in decisions about analgesia. Severe pain, however, may interfere with active participation in choosing pain relief measures. If an analgesic is to be given, the nurse must make a clinical judgment of the type, appropriate dosage, and frequency from the medications ordered. The woman is informed of the prescribed analgesic and its common side effects; this teaching is documented.

Breastfeeding mothers often have concerns about the effects of an analgesic on the infant. Although nearly all drugs present in maternal circulation are also found in breast milk, many analgesics commonly used during the postpartum period are considered relatively safe for breastfeeding mothers and infants. Often the timing of medications can be adjusted to minimize infant exposure. A mother may be given pain medication immediately after breastfeeding so that the interval between medication administration and the next nursing period is as long as possible. The decision to administer medications of any kind to a breastfeeding mother must always be made by carefully weighing the woman’s need against actual or potential risks to the infant.

If acceptable pain relief has not been obtained in 1 hour and there is no change in the initial assessment, the nurse may need to contact the primary care provider for additional pain relief orders or further directions. Unrelieved pain results in fatigue, anxiety, and a worsening perception of the pain. It might also indicate the presence of a previously unidentified or untreated problem.

Rest: Postpartum fatigue (PPF) is more than just feeling tired; it is a complex phenomenon affected by a combination of physiologic, psychologic, and situational variables. Fatigue is common in the early postpartum period and involves physiologic as well as psychologic components. Physical fatigue or exhaustion may be associated with long labors or cesarean birth; hospital routines and infant care demands such as breastfeeding also contribute to maternal fatigue. Fatigue can also be associated with anemia, infection, or thyroid dysfunction (Corwin & Arbour, 2007). The excitement and exhilaration experienced after the birth of the infant makes resting difficult. Physical discomfort can interfere with sleep. Well-intentioned visitors can interrupt periods of rest in the hospital and at home. Mothers can also experience psychologic fatigue related to anxiety or depression. PPF is a recognized risk factor for postpartum depression (Corwin, Brownstead, Barton, Heckard, & Morin, 2005).

Fatigue is likely to worsen over the first 6 weeks after birth, often because of situational factors. After discharge from the hospital, fatigue increases as the woman provides care and feeding for the newborn in combination with other family and household responsibilities such as caring for other children, preparing meals, and doing laundry. Many women have partners, family members, or friends to provide much-needed assistance, whereas others can be without any help at all. The nurse needs to inquire about resources available to the woman after discharge and help her plan accordingly (Runquist, 2007).

Interventions are planned to meet the woman’s individual needs for sleep and rest while she is in the hospital. Back rubs, other comfort measures, and medication for sleep may be necessary. The side-lying position for breastfeeding minimizes fatigue in nursing mothers. Support and encouragement of mothering behaviors help reduce anxiety. Hospital and nursing routines can be adjusted to meet needs of individual mothers. In addition, the nurse can help the family limit visitors and provide a comfortable chair or bed for the partner or other family member who is staying with the new mother.

Because PPF can be very debilitating, follow-up after hospital discharge is important. Screening for PPF can be accomplished with a nurse-initiated telephone call at 2 weeks, as well as at the routine 6-week postpartum visit with the health care provider (Corwin & Arbour, 2007).

Physiologic factors contributing to postpartum fatigue are amenable to intervention and may be identified even before birth. Women with anemia, infection or inflammation, or thyroid dysfunction can be identified as having increased risk for postpartum fatigue. Other physical conditions and psychologic or situational factors that might contribute to PPF can be identified during the prenatal period. The medical records of women with known risk factors can be flagged to alert hospital staff to their special needs (Corwin & Arbour, 2007).

Ambulation: Early ambulation is associated with a reduced incidence of venous thromboembolism (VTE); it also promotes the return of strength. Free movement is encouraged once anesthesia wears off unless a narcotic analgesic has been administered. After the initial recovery period the mother is encouraged to ambulate frequently.

In the early postpartum period, women can feel lightheaded or dizzy when standing. The rapid decrease in intraabdominal pressure after birth results in a dilation of blood vessels supplying the intestines (splanchnic engorgement) and causes blood to pool in the viscera. This condition contributes to the development of orthostatic hypotension when the woman who has recently given birth sits or stands up, first ambulates or takes a warm shower or sitz bath. When assisting a woman to ambulate, the nurse needs to consider the baseline blood pressure, amount of blood loss, and type, amount, and timing of analgesic or anesthetic medications administered.

Women who have had epidural anesthesia may have slow return of sensory and motor function in their lower extremities, increasing the risk of falls with early ambulation. Careful assessment by the postpartum nurse can prevent falls. Factors that the nurse should consider are the time lapse since epidural medication was given; the woman’s ability to bend both knees, place both feet flat on the bed, and lift buttocks off the bed without assistance; medications since birth; vital signs; and estimated blood loss with birth. Before allowing the woman to ambulate the nurse assesses the ability of the woman to stand unassisted beside her bed, simultaneously bending both knees slightly, and then standing with knees locked. If the woman is unable to balance herself, she can be safely eased back into bed without injury (Frank, Lane, & Hokanson, 2009).

Prevention of venous thromboembolism is important. Women who must remain in bed after giving birth are at increased risk for the development of a thromboembolism. Antiembolic stockings (TED hose) or a sequential compression device (SCD boots) can be ordered prophylactically. If a woman remains in bed longer than 8 hours (e.g., for postpartum magnesium sulfate therapy for preeclampsia), exercise to promote circulation in the legs is indicated, using the following routine:

• Alternating flexion and extension of feet

• Rotating the ankles in a circular motion

If the woman is susceptible to thromboembolism, she is encouraged to walk about actively for true ambulation and is discouraged from sitting immobile in a chair. Women with varicosities are encouraged to wear support hose. If a thrombus is suspected, as evidenced by complaint of pain in calf muscles or warmth, redness, or tenderness in the suspected leg, or a positive Homans sign (dorsiflexing the foot sharply with the knee flexed; may cause pain in the calf in the presence of deep vein thrombosis), the primary health care provider should be notified; meanwhile the woman should be confined to bed, with the affected limb elevated on pillows.

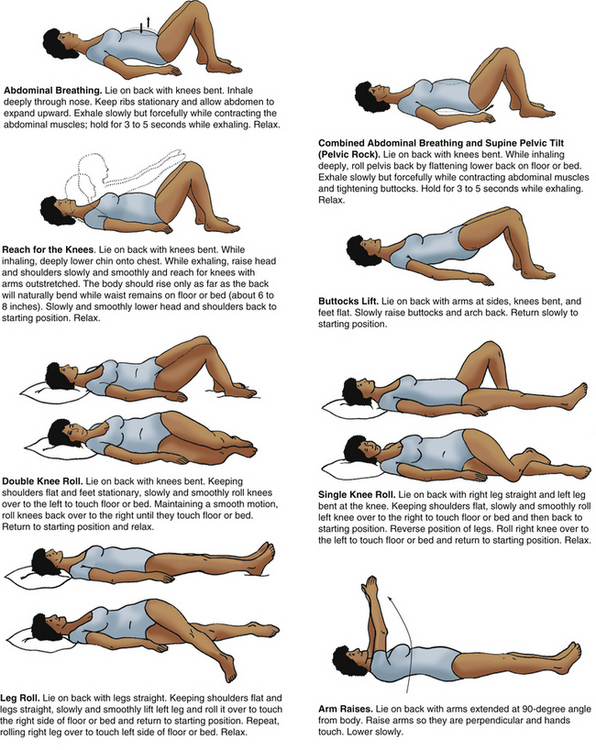

Exercise: Postpartum exercise can begin soon after birth, although the woman should be encouraged to start with simple exercises and gradually progress to more strenuous ones. Figure 21-4 illustrates a number of exercises appropriate for the new mother. Abdominal exercises are postponed until approximately 4 weeks after cesarean birth.

FIG. 21-4 Postpartum exercise should begin as soon as possible. The woman should start with simple exercises and gradually progress to more strenuous ones.

Kegel exercises to strengthen muscle tone are extremely important, particularly after vaginal birth. Kegel exercises help women regain the muscle tone that is often lost as pelvic tissues are stretched and torn during pregnancy and birth. Women who maintain muscle strength benefit years later by retaining urinary continence.

Women must learn to perform Kegel exercises correctly (see Teaching for Self-Management box on p. 91). Some women perform them incorrectly and may increase their risk of incontinence, which can occur when inadvertently bearing down on the pelvic floor muscles, thrusting the perineum outward. The woman’s technique can be assessed during the pelvic examination at her checkup by inserting two fingers intravaginally and noting whether the pelvic floor muscles correctly contract and relax.

Promotion of Nutrition

During the hospital stay most women display a good appetite and eat well. They can request that family members bring favorite or culturally appropriate foods. Cultural dietary preferences must be respected. This interest in food presents an ideal opportunity for nutritional counseling on dietary needs after pregnancy, with specific information related to breastfeeding, preventing constipation and anemia, promoting weight loss, and promoting healing and well-being (see Chapter 14). Prenatal vitamins and iron supplements are often continued until 6 weeks after childbirth or until the ordered supply has been used.

The recommended caloric intake for the moderately active, nonlactating postpartum woman is 1800 to 2200 kcal/day. According to the Institute of Medicine (2005) the estimated energy requirement (EER) for a lactating woman during the first 6 months is 2700 kcal/day; during the next 6 months it is 2768 kcal/day. Higher-than-normal caloric intake is recommended

for lactating women who are underweight or who exercise vigorously and those who are breastfeeding more than one infant. See Chapter 14 for recommendations for weight loss for the obese woman. Although most women desire to return to their prepregnancy weight as soon as possible, gradual weight loss is recommended (Becker & Scott, 2008).

Promotion of Normal Bladder and Bowel Patterns

Bladder Function: The mother should void spontaneously within 6 to 8 hours after giving birth. The first several voidings should be measured to document adequate emptying of the bladder. A volume of at least 150 mL is expected for each voiding. Some women experience difficulty in emptying the bladder, possibly as a result of diminished bladder tone, edema from trauma, or fear of discomfort. Nursing interventions for inability to void and bladder distention are discussed on p. 494.

Bowel Function: After birth, women may be at risk for constipation related to side effects of medications (narcotic analgesics, iron supplements, magnesium sulfate), dehydration, immobility, or the presence of episiotomy, perineal lacerations, or hemorrhoids. The woman may fear pain with the first bowel movement.

Nursing interventions to promote normal bowel elimination include educating the woman about measures to prevent constipation, such as ensuring adequate intake of roughage and fluids and promoting exercise. Alerting the woman to side effects of medications such as narcotic analgesics (e.g., decreased gastrointestinal tract motility) may encourage her to implement measures to reduce the risk of constipation. Stool softeners or laxatives may be necessary during the early postpartum period. With early discharge, a new mother may be home before having a bowel movement.

Some mothers experience gas pains; this is more common following cesarean birth. Antigas medications may be ordered. Ambulation or rocking in a rocking chair may stimulate passage of flatus and relief of discomfort.

Breastfeeding Promotion and Lactation Suppression

Breastfeeding Promotion: The ideal time to initiate breastfeeding is within the first 1 to 2 hours after birth. Baby-friendly hospitals mandate that the infant be put to breast within the first hour after birth (Baby-Friendly Hospital Initiative USA, 2010). At this time, most infants are alert and ready to nurse. Breastfeeding aids in the contraction of the uterus and prevention of maternal hemorrhage. The first hour after birth is also an opportune time to assist the mother with breastfeeding, assess her basic knowledge of breastfeeding, and assess the physical appearance of the breasts and nipples. Throughout the hospital stay, nurses provide teaching and assistance for the breastfeeding mother, making appropriate referrals to lactation consultants as needed and available. (See Chapter 25 for further information on assisting the breastfeeding woman.)

Lactation Suppression: Suppression of lactation is necessary when the woman has decided not to breastfeed or in the case of neonatal death. Wearing a well-fitted support bra continuously for at least the first 72 hours after giving birth is important. Women should avoid breast stimulation, including running warm water over the breasts, newborn suckling, or pumping of the breasts. Some nonbreastfeeding mothers experience severe breast engorgement (swelling of breast tissue caused by increased blood and lymph supply to the breasts as the body produces milk, occurring at about 72 to 96 hours after birth). Breast engorgement can usually be managed satisfactorily with nonpharmacologic interventions.

Ice packs to the breasts help decrease the discomfort associated with engorgement. The woman should use a 15 minutes on, 45 minutes off schedule (to prevent the rebound swelling that can occur if ice is used continuously). While there is lack of scientific evidence to support effectiveness, cabbage leaves are often recommended to help relieve the engorgement; formula-feeding mothers may be told to place fresh green cabbage leaves over their breasts and to replace the leaves when they are wilted. ![]() A mild analgesic or antiinflammatory medication can aid in decreasing the discomfort associated with engorgement. Medications that were once prescribed for lactation suppression (e.g., estrogen, estrogen and testosterone, and bromocriptine) are no longer used.

A mild analgesic or antiinflammatory medication can aid in decreasing the discomfort associated with engorgement. Medications that were once prescribed for lactation suppression (e.g., estrogen, estrogen and testosterone, and bromocriptine) are no longer used.

Health Promotion for Future Pregnancies and Children

Rubella Vaccination: For women who have not had rubella (10% to 20% of all women) or women who are serologically not immune (titer of 1:8 or enzyme immunoassay level less than 0.8), a subcutaneous injection of rubella vaccine is recommended in the postpartum period to prevent the possibility of contracting rubella in future pregnancies. Seroconversion occurs in approximately 90% of women vaccinated after birth. The live attenuated rubella virus is not communicable in breast milk; therefore, breastfeeding mothers can be vaccinated. However, because the virus is shed in urine and other body fluids, the vaccine should not be given if the mother or other household members are immunocompromised. The most common side effects are fever, lymphadenopathy, and arthralgia.

Varicella Vaccination: The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) recommend that varicella vaccine be administered before discharge in women who have no immunity. A second dose is given at the postpartum follow-up visit (4 to 8 weeks) (CDC, 2007).

Tetanus-Diphtheria-Acellular Pertussis Vaccine: Tetanus-diphtheria-acellular pertussis (Tdap) vaccine is recommended for postpartum women who have not previously received the

vaccine; it is given before discharge from the hospital or as early as possible in the postpartum period to protect women from pertussis and to decrease the risk of infant exposure to pertussis. For women whose most recent tetanus-diphtheria (Td) vaccine was given more than 2 years before the pregnancy, the Tdap vaccine can also be given in the early postpartum period (CDC, 2008).

Prevention of Rh Isoimmunization: Injection of Rh immune globulin (a solution of gamma globulin that contains Rh antibodies) within 72 hours after birth prevents sensitization in the Rh-negative woman who has had a fetomaternal transfusion of Rh-positive fetal red blood cells (RBCs) (see the Medication Guide). Rh immune globulin promotes lysis of fetal Rh-positive blood cells before the mother forms her own antibodies against them.

The administration of 300 mcg (1 vial) of Rh immune globulin is usually sufficient to prevent maternal sensitization. If a large fetomaternal transfusion is suspected, however, the dosage needed should be determined by performing a Kleihauer-Betke test, which detects the amount of fetal blood in the maternal circulation. If more than 15 ml of fetal blood is present in maternal circulation, the dosage of Rh immune globulin must be increased.

A 1:1000 dilution of Rh immune globulin is crossmatched to the mother’s RBCs to ensure compatibility. Because Rh immune globulin is usually considered a blood product, precautions similar to those used for transfusing blood are necessary. The identification number on the woman’s hospital wristband should correspond to the identification number found on the laboratory slip. The nurse must also check to see that the lot number on the laboratory slip corresponds to the lot number on the vial. Finally, the expiration date on the vial should be checked to be certain of a usable product.

Rh immune globulin suppresses the immune response. Therefore, the woman who receives both Rh immune globulin and rubella vaccine must be tested at 3 months to see if she has developed rubella immunity. If not, she will need another dose of rubella vaccine.

There is some disagreement about whether Rh immune globulin should be considered a blood product. Health care providers need to discuss the most current information about this issue with women whose religious beliefs conflict with having blood products administered to them (e.g., Jehovah’s Witnesses).

Care Management: Psychosocial Needs

Meeting the psychosocial needs of new mothers involves assessing the parents’ reactions to the birth experience, feelings about themselves, and interactions with the new baby and other family members. Specific interventions are planned to increase the parents’ knowledge and self-confidence as they assume the care and responsibility of the new baby and integrate this new member into their existing family structure in a way that meets their cultural expectations (see Chapters 22 and 24 and the Nursing Process box: Postpartum Pyschosocial Concerns).

There is evidence that nurses and other health care providers do not adequately address maternal psychosocial needs, instead focusing their attention on postpartum physical changes and medically based care (Cheung, Fowles, & Walker, 2006). Taking time to assess maternal emotional needs and to address concerns before discharge may promote better psychologic health and adjustment to parenting. Ongoing support for postpartum women is also needed. Even though issues such as fatigue are often evident during the hospital stay, clearly this type of support will likely be an ongoing concern after discharge when the woman is providing care for the newborn, herself, and other family members. Postpartum support is especially beneficial to at-risk populations such as low-income primiparas, those at risk for family dysfunction and child abuse, and those at risk for postpartum depression (Shaw, Levitt, Wong, & Kaczorowski, 2006).

Sometimes the psychosocial assessment indicates serious actual or potential problems that must be addressed. The Signs of Potential Complications box identifies psychosocial characteristics and behaviors that may warrant ongoing evaluation after hospital discharge. Women exhibiting these needs should be referred to appropriate community resources for assessment and management.

Effect of the Birth Experience

Many women indicate a need to examine the birth process itself and look retrospectively at their own intrapartal behavior. Their partners may express similar desires. If their birth experience was different from their birth plan (e.g., induction, epidural anesthesia, cesarean birth), both partners may need to mourn the loss of their expectations before they can adjust to the reality of their actual birth experience. Inviting them to review the events and describe how they feel helps the nurse assess how well they understand what happened and how well they have been able to put their childbirth experience into perspective.

Maternal Self-Image

An important assessment concerns the woman’s self-concept, body image, and sexuality. How the new mother feels about herself and her body during the postpartum period may affect her behavior and adaptation to parenting. The woman’s self-concept and body image can also affect her sexuality.

Feelings related to sexual adjustment after childbirth are often a cause of concern for new parents. Women who have recently given birth may be reluctant to resume sexual intercourse for fear of pain or may worry that coitus could damage healing perineal tissue. Because many new parents are anxious for information but reluctant to bring up the subject,

postpartum nurses should matter-of-factly include the topic of postpartum sexuality during their routine physical assessment and teaching. Partners often have questions and concerns as well; it is helpful to include them in teaching sessions or discussions regarding sexuality in the postpartum period.

Adaptation to Parenthood and Parent-Infant Interactions

The psychosocial assessment also includes evaluating adaptation to parenthood. This task is accomplished by observing maternal and paternal reactions to the newborn and their interactions with the infant. Clues indicating successful adaptation begin to appear soon after birth as parents react positively to the newborn infant and continue the process of establishing a relationship with their infant. In nontraditional families, such as lesbian couples, it is important to observe the partner’s reactions and interactions with the neonate.

Parents are adapting well to their new roles when they exhibit a realistic perception and acceptance of their newborn’s needs and limited abilities, immature social responses, and helplessness. Examples of positive parent-infant interactions include taking pleasure in the infant and in providing care, responding appropriately to infant cues, and providing comfort (see Chapter 24). Should these indicators be missing, the nurse needs to investigate further what is hindering the normal adaptation process.

Family Structure and Functioning

A woman’s adjustment to her role as mother is affected greatly by her relationships with her partner, her mother and other relatives, and any other children (Fig. 21-5). Nurses can help ease the new mother’s return home by identifying possible conflicts among family members and helping the woman plan strategies for dealing with these problems before discharge. Such a conflict could arise when couples have very different ideas about parenting. Dealing with the stresses of sibling rivalry and unsolicited grandparent advice also can affect the woman’s psychologic well-being. Only by asking about other nuclear and extended family members can the nurse discover potential problems in such relationships and help plan workable solutions for them.

Effect of Cultural Diversity

The final component of a complete psychosocial assessment is the woman’s cultural beliefs, values, and practices. Much of a woman’s behavior during the postpartum period is strongly influenced by her cultural background. Nurses are likely to come into contact with women from many different countries and cultures. Within the North American population, varied traditional health beliefs and practices can be found. All cultures have developed safe and satisfying methods of caring for new mothers and babies. Only by understanding and respecting the values and beliefs of each woman can the nurse design a plan of care to meet the individual’s needs.

To identify cultural beliefs and practices when planning and implementing care, the nurse conducts a cultural assessment. This assessment is ongoing; it is ideally begun during pregnancy and continued into the postpartum period. It can be accomplished most easily through conversation with the mother and her partner. Some hospitals have assessment tools designed to identify cultural beliefs and practices that may influence care (Cooper, Grywalski, Lamp, Newhouse, & Studlien, 2007). Components of the cultural assessment include the ability to read and write English, primary language spoken, family involvement and support, dietary preferences, infant care, attachment, circumcision, religious or cultural beliefs, folk medicine practices, nonverbal communication, and personal space preferences.

Women from various cultures view health as a balance between opposing forces (e.g., cold versus hot; yin versus yang), being in harmony with nature, or just “feeling good.” Traditional practices may include the observance of certain dietary restrictions, clothing, or taboos for balancing the body; participation in certain activities such as sports and art for maintaining mental health; and use of silence, prayer, or meditation for developing spiritually. Practices (e.g., using religious objects or eating garlic) are used to protect oneself from illness and can involve avoiding people who are believed to create hexes or spells or who have an “evil eye.” Restoration of health can involve taking folk medicines (e.g., herbs, animal substances) or using a traditional healer.

Childbirth occurs within this sociocultural context. Rest, seclusion, dietary restraints, and ceremonies honoring the mother are all common traditional practices that are followed for the promotion of the health and well-being of the mother and baby.

During the postpartum period there are several common traditional health practices used and beliefs held by women and their families. In Asia, for example, pregnancy is considered to be a “hot” state, and childbirth results in a sudden loss of this state. Therefore, balance must be restored by facilitating the return of the hot state, which is present physically or symbolically in hot food, hot water, and warm air.

Another common belief is that the mother and baby remain in a weak and vulnerable state for several weeks after birth. During this time the mother may remain in a passive role, taking no baths or showers, and may stay in bed to prevent cold air from entering her body.

Women who have immigrated to the United States or other Western nations without their extended families may have little help at home, making it difficult for them to observe these activity restrictions. The Cultural Considerations box lists some common cultural beliefs about the postpartum period and family planning.

It is important that nurses consider all cultural aspects when planning care and avoid using their own cultural beliefs as the framework for that care. Although the beliefs and behaviors of other cultures seem different or strange, they should be encouraged as long as the mother wants to conform to them and she and the baby suffer no ill effects. The nurse needs to determine whether a woman is using any folk medicine during the postpartum period because active ingredients in folk medicine can have adverse physiologic effects when used in combination with prescribed medicines. The nurse should not assume that a mother desires to use traditional health practices that represent a particular cultural group merely because she is a member of that culture. Many young women who are first- or second-generation Americans follow their cultural traditions only when older family members are present, or not at all.

Discharge Teaching

Self-Management and Signs of Complications

Discharge planning begins at the time of admission to the unit and should be reflected in the nursing care plan developed for each individual woman. For example, a great deal of time during the hospital stay is usually spent in teaching about

maternal self-management and care of the newborn because the goal is for all women to be capable of providing basic care for themselves and their infants at the time of discharge. In addition, every woman must be taught to recognize physical and psychologic signs and symptoms that might indicate problems and how to obtain advice and assistance quickly if these signs appear. Table 21-2 and the Signs of Potential Complications box on pp. 489 and 5000, respectively, list several common indications of maternal physical and psychosocial problems in the postpartum period. (See Chapter 34 for more information on postpartum complications.) Before discharge, women need basic instruction regarding a variety of self-management topics such as nutrition, exercise, family planning, the resumption of sexual intercourse, prescribed medications, and routine mother-baby follow-up care.

Because of the limited time available for teaching, nurses must target their teaching on expressed needs of the woman. Giving the woman a list of topics and asking her to indicate her learning needs helps the nurse maximize teaching efforts and can increase retention of information. Providing written materials on postpartum self-management, breastfeeding, and infant care that the woman can consult after discharge is helpful.

Just before the time of discharge the nurse reviews the woman’s chart to see that laboratory reports, medications, signatures, and other items are in order. Some hospitals have a checklist to use before the woman’s discharge. The nurse verifies that medications, if ordered, have arrived on the unit; that any valuables kept secured during the woman’s stay have been returned to her and that she has signed a receipt for them; and that the infant is ready to be discharged. The woman’s and the baby’s identification bands are carefully checked.

No medication that can cause drowsiness should be administered to the mother before discharge if she is the one who will be holding the baby on the way out of the hospital. In most instances, the woman is seated in a wheelchair and is given the baby to hold. Some families leave unescorted and ambulatory, depending on hospital protocol. The newborn must be secured in a car seat for the drive home.

In many hospitals, new mothers (breastfeeding and formula feeding) are routinely presented with gift bags that contain samples of infant formula.

Sexual Activity and Contraception

Discussing sexual activity with the woman and her partner and family planning with heterosexual couples is important before they leave the hospital because many couples resume sexual activity before the traditional postpartum checkup 6 weeks after childbirth. For most women the risk of hemorrhage or infection is minimal by approximately 2 weeks postpartum. Couples may be anxious about the topic but uncomfortable and unwilling to bring it up. The nurse needs to discuss the physical and psychologic effects that giving birth can have on sexual activity (see the Teaching for Self-Management box). Contraceptive options should also be discussed with heterosexual women (and their partners, if present) before discharge so that they can make informed decisions about fertility management before resuming sexual activity. Waiting to discuss contraception at the 6-week checkup may be too late. Ovulation can occur as soon as 1 month after birth, particularly in women who bottle-feed. Breastfeeding mothers should be informed that breastfeeding is not a reliable means of contraception and that other methods should be used; nonhormonal methods are best because oral contraceptives can interfere with milk production. Women who are undecided about contraception at the time of discharge need information about using condoms with foam or creams until the first postpartum checkup. Contraceptive options are discussed in detail in Chapter 8.

Prescribed Medications

Women routinely continue to take their prenatal vitamins during the postpartum period. Breastfeeding mothers usually continue prenatal vitamins for the duration of breastfeeding. Supplemental iron can be prescribed for mothers with lower than normal hemoglobin levels. Women with extensive episiotomies or perineal lacerations (third or fourth degree) are usually prescribed stool softeners to take at home. Pain medications (analgesics or NSAIDs) may be prescribed, especially for women who had cesarean births. The nurse should make certain that the woman knows the route, dosage, frequency, and common side effects of all medications that she will be taking at home. Written information about the medications is usually included in the discharge instructions.

Follow-Up After Discharge

Routine Mother and Baby Follow-up Care

Women who have experienced uncomplicated vaginal births are commonly scheduled for the traditional 6-week postpartum examination. Women who have had a cesarean birth are often seen in the health care provider’s office or clinic within 2 weeks after hospital discharge. The date and time for the follow-up appointment should be included in the discharge instructions. If an appointment has not been made before the woman leaves the hospital, she should be encouraged to call the health care provider’s office or clinic to schedule an appointment.

Parents who have not already done so need to make plans for newborn follow-up at the time of discharge. Breastfeeding infants are routinely seen by the pediatric health care provider or clinic within 3 to 5 days after discharge and again at approximately 2 weeks of age. Formula-feeding infants may be seen for the first time at 2 weeks of age. If an appointment for a specific date and time was not made for the infant before leaving the hospital, the parents should be encouraged to call the office or clinic soon after their arrival home.

Home Visits

Home visits to mothers and babies within a few days of discharge can help bridge the gap between hospital care and routine visits to health care providers. Nurses can assess the mother, the infant, and the home environment; answer questions and provide education and emotional support; and make referrals to community resources if necessary. Home visits have been shown to reduce the need for more expensive health care, such as emergency department visits and rehospitalization; they can also reduce the incidence of postpartum depression in women who are at risk (Goulet et al., 2007).

The support provided by nurses and other trained community health workers can enhance parent-infant interaction and parenting skills; home visits also help to promote mutual support between the mother and her partner (De La Rosa, Perry, & Johnson, 2009). Breastfeeding outcomes can be enhanced through home visitation programs (Mannan, Rahman, Sania, Seraji, Arifeen, Winch, et al., 2008).

Home nursing care may not be available, even if needed, because no agencies are available to provide the service or no coverage is in place for payment by third-party payers. If care is available, a referral form containing information about the mother and baby should be completed at hospital discharge and sent immediately to the home care agency.

The home visit is most commonly scheduled on the woman’s second day home from the hospital, but it can be scheduled on any of the first 4 days at home, depending on the individual family’s situation and needs. Additional visits are planned throughout the first week, as needed. The home visits may be extended beyond that time if the family’s needs warrant it and if a home visit is the most appropriate option for carrying out the follow-up care required to meet the specific needs identified.

During the home visit the nurse conducts a systematic assessment of mother and newborn to determine physiologic adjustment and to identify any existing complications, The assessment also focuses on the mother’s emotional adjustment and her knowledge of self-management and infant care. Conducting the assessment in a private area of the home provides an opportunity for the mother to ask questions on potentially sensitive topics such as breast care, constipation, sexual activity, or family planning. Family adjustment to the newborn is assessed and concerns are addressed during the home visit.

During the newborn assessment the nurse can demonstrate and explain normal newborn behavior and capabilities and encourage the mother and family to ask questions or express concerns they have. The home care nurse verifies if the newborn screen for phenylketonuria and other inborn errors of metabolism has been drawn. If the baby was discharged from the hospital before 24 hours of age, a blood sample for the newborn screen can be drawn by the home care nurse or the family will need to take the infant to the health care provider’s office or clinic.

Telephone Follow-up

In addition to or instead of a home visit, many providers are implementing one or more postpartum telephone follow-up calls to their clients for assessment, health teaching, and identification of complications to effect timely intervention and referrals. Telephone follow-up may be among the services offered by hospitals, private physicians, clinics, or private agencies. It may be either a separate service or combined with other strategies for extending postpartum care. Telephone nursing assessments are frequently used as follow-up to postpartum home visits.

Warm Lines

The warm line is another type of telephone link between the new family and concerned caregivers or experienced parent volunteers. A warm line is a help line or consultation service, not a crisis intervention line. The warm line is appropriately used for dealing with less extreme concerns that seem urgent at the time the call is placed but are not actual emergencies. Calls to warm lines commonly relate to infant feeding, prolonged crying, or sibling rivalry. Families are encouraged to call when concerns arise. Telephone numbers for warm lines should be given to parents before hospital discharge.

Support Groups

The woman adjusting to motherhood may desire interaction and conversation with other women who are having similar experiences. Postpartum women who have met earlier in prenatal clinics or on the hospital unit may begin to associate for mutual support. Members of childbirth classes who attend a postpartum reunion may decide to extend their relationship during the fourth trimester. Fathers or partners also benefit from participation in support groups.

A postpartum support group enables mothers and partners/fathers to share with and support each other as they adjust to parenting. Many new parents find it reassuring to discover that they are not alone in their feelings of confusion and uncertainty. An experienced parent can often impart concrete information that is valuable to other group members. Inexperienced parents can imitate the behavior of others in the group whom they perceive as particularly capable.

Referral to Community Resources

To develop an effective referral system the nurse should have an understanding of the needs of the woman and family and of the organization and community resources available for meeting those needs. Locating and compiling information about available community services contributes to the development of a referral system. The nurse also needs to develop his or her own resource file of local and national services that are commonly used by health care providers (see Resources on this book’s Evolve website).

KEY POINTS

• Postpartum care is family centered and modeled on the concept of health.

• Cultural beliefs and practices affect the maternal and family response to the postpartum period.

• The nursing care plan includes assessments to detect deviations from normal, comfort measures to relieve discomfort or pain, and safety measures to prevent injury or infection.

• Common nursing interventions in the postpartum period focus on prevention of excessive bleeding, bladder distention, infection; nonpharmacologic and pharmacologic relief of discomfort associated with the episiotomy, lacerations, or breastfeeding; and instituting measures to promote or suppress lactation.

• Teaching and counseling measures are designed to promote the woman’s feelings of competence in self-management and infant care.

• Meeting the psychosocial needs of new mothers involves taking into consideration the composition and functioning of the entire family.

• Early postpartum discharge will continue as a result of consumer demand, medical necessity, discharge criteria for low risk childbirth, and cost-containment measures.

• Early discharge classes, telephone follow-up, home visits, warm lines, and support groups are effective means of facilitating physiologic and psychologic adjustments in the postpartum period.

![]() Audio Chapter Summaries Access an audio summary of these Key Points on

Audio Chapter Summaries Access an audio summary of these Key Points on ![]()