Perinatal Loss and Grief

• Describe the causes of perinatal loss.

• Describe the grieving process of parents who experience perinatal loss.

• Analyze the personal and societal issues that can complicate responses to perinatal loss.

• Formulate appropriate nursing diagnoses for parents experiencing perinatal loss.

• Identify specific nursing interventions to meet the special needs of parents and their families related to perinatal loss and grief.

• Differentiate among helpful and nonhelpful responses in caring for parents experiencing loss and grief.

• Discuss assessment and nursing interventions for parents experiencing complicated grief.

Becoming a parent is an important developmental milestone that most men and women in our society anticipate. Becoming a parent gives one social status, expands one’s capacity for caring and for loving another, and adds immense responsibility to one’s life. However, pregnancy and birth can also be associated with loss.

The focus of this chapter is to prepare the nurse to provide sensitive, supportive, and therapeutic interventions to parents experiencing perinatal loss in a variety of settings. An overview of the grief process is presented as a guide for assessing and understanding the responses of bereaved women, men, and their families. Guidelines for interventions are given and specific intervention approaches are discussed.

Perinatal Loss

During pregnancy parents plan for the birth, imagine what the birth will be like, and develop an image of the baby. The reality of childbirth can be inconsistent with the parents’ hopes and dreams. In particular, the experience of preterm labor and birth or cesarean birth involves loss of the expected pregnancy and birth plans. Parents also may grieve over the sex or appearance of their child. For some parents, loss is associated with the birth of an infant who has a birth defect or chronic illness.

Although having children can be a strong desire and goal for women and men, not everyone is successful in achieving parenthood. For some couples, infertility can thwart their plans and desires for parenthood and cause intense feelings of grief (McGrath, Samra, Zukowsky, & Baker, 2010). When couples undergo infertility treatments, feelings of loss can intensify, especially when treatments fail and/or a pregnancy ends in an ectopic pregnancy loss or miscarriage. When infertility treatment is successful, loss and grief can confound the joy if selective reduction of multifetal pregnancy is done (Little, 2010).

Many women and their partners, whether infertile or not, experience perinatal loss. This includes ectopic pregnancy, fetal death, or miscarriage, all of which occur in the early months of pregnancy. These early pregnancy losses are often called “hidden” or “silent” because others in the women’s network do not even know about the pregnancy and subsequent loss, or because family and friends do not feel comfortable bringing up the loss with the woman and her partner, resulting in acute grief and loneliness (Brier, 2008).

Women and their partners can suddenly be confronted with stillbirth, the birth of an infant who is not alive. Stillbirth is particularly devastating because it occurs suddenly and late in the pregnancy when expectant parents are preparing for the birth of a healthy infant (Cacciatore, 2010).

Couples also can face the death of an infant after birth who has serious health problems related to prematurity, severe congenital anomalies, genetic defects, or other complications. Some of these newborns survive only a few hours or die after days, weeks, or months in an intensive care unit, where complex highly technologic care and invasive treatments are used to try to save their lives. Many of these parents are confronted with making difficult end-of-life decisions about their baby (De Lisle-Porter & Podruchny, 2009). Another tragic loss for parents is death of an older infant from sudden infant death syndrome (SIDS).

Parents who face challenges in achieving and maintaining a pregnancy, learning about their infant’s fatal or serious health problems, and coping with the loss of a fetus or death of an infant experience intense psychologic distress and grief. Grief involves the painful emotions and related behavioral and physical responses to a major loss. Grief can be particularly difficult with perinatal losses for a number of reasons. One is the societal belief that there are no barriers to getting pregnant, thus, perinatal losses are often hidden or private. Another is the expectation that once a woman is pregnant, the outcome will be a healthy live infant. As a result, our society tends to minimize or discount perinatal loss and lacks an understanding of the associated pain (Brier, 2008; Fretts, 2009).

Perinatal losses can be intensified for couples who delay pregnancy until the woman’s career and the family’s financial status are at the right point to take on the responsibilities of a child. Feelings of helplessness and loss of control can be very difficult when the couple experiences infertility or miscarriage. In many instances of perinatal loss, the lack of an identified cause for the loss can complicate grief. This is particularly difficult for women, who often feel personally responsible for infertility, miscarriage, and infant death. Some couples endure repeated losses, which can be devastating. Further, society allows too little time for mothers to grieve a perinatal loss and even less for men (O’Leary & Thorwick, 2006). Women and men who undergo perinatal losses often struggle with these issues alone and without the support they need because many perinatal losses are hidden or private.

Nurses have a powerful influence on how parents experience and cope with perinatal loss (Gold, 2007; Gold, Dalton, & Schwenk, 2007; Murphy & Merrell, 2009). Nurses encounter these parents in a variety of settings, including the antepartum, labor and birth, neonatal, postpartum, and gynecologic units of hospitals; and obstetric, gynecologic, and infertility outpatient clinics and general medical offices. In these settings nurses have opportunities to provide sensitive and caring interventions to parents. Parents have reported that their nurses were an important resource in helping them cope with their grief; parents tend to rate nurses as more supportive than physicians or other care providers (Gold, 2007).

Nurses in many inpatient settings have developed protocols that provide clear direction to all staff in how to help parents through this difficult process. In some units experienced nurses or social workers who are particularly comfortable in helping bereaved parents are designated as perinatal grief consultants. They are available to help parents and to help staff prepare for their roles with parents. In addition, many institutions now have follow-up programs involving telephone calls, home visits, and support groups that are effective in helping parents after discharge. These models for care of bereaved parents have evolved into more formalized perinatal hospice or palliative care programs in a variety of settings including prenatal diagnostic and genetic programs, maternity care clinics, and inpatient maternity and neonatal intensive care units (Breeze, Lees, Kumar, Missfelder-Lobos, & Murdoch, 2007; Leuthner & Jones, 2007; Murphy & Merrell, 2009; Rousch, Sullivan, Cooper, & McBride, 2007). It is important, then, that nurses are prepared to help parents deal with perinatal loss.

Grief Responses

Grief or bereavement has been described as a cluster of painful responses experienced following a major loss or death. In a concept analysis of grief, Cowles and Rodgers (2000) identified attributes of grief: (a) grief is dynamic and involves an ever-changing complex of emotions, thoughts, and behaviors, (b) grief is a process that is enduring and has no time limit; (c) grief is highly individualized and manifested in many different ways from one person to the next; and (d) grief is pervasive in that it involves psychologic, social, physical, cognitive, behavioral, and affective responses and can affect every aspect of a person’s life. Grief is experienced and expressed in an individualized manner and is particularly affected by the meaning of the loss to the person.

The model of grief presented here is based on years of clinical work by the author with bereaved parents and on the conceptualization of others regarding grief (Miles, 1984). It is hypothesized that parental grief responses occur in three overlapping phases (Box 38-1). There is an early period of acute distress and shock followed by a period of intense grief that includes emotional, cognitive, behavioral, and physical responses. Parents reach the phase of reorganization when they return to their usual level of functioning in society, although the pain associated with the death remains. There is general agreement that parental grief is a long-term process that can extend for months and years and that some aspects of their grief endure through life.

Acute Distress

The loss of a pregnancy or the death of an infant is an acute and distressing experience for mothers and fathers. The loss encompasses a loss of their identity as a mother or father and their many dreams related to parenthood (Arnold & Gemma, 2008). The immediate reaction to news of a perinatal loss or infant death encompasses a period of acute distress. Parents generally are in a state of shock and numbness. They can feel a sense of unreality, loss of innocence, and powerlessness as though they were in a bad dream or in a fog or trance-like state. Disbelief and denial can occur. Sadness, devastation, and depression as well as intense outbursts of emotion and crying are common. However, lack of affect, euphoria, and calmness can reflect numbness, denial, or a personal way of coping with stress.

Much of the literature and research on grief after perinatal loss and infant death has focused on the mother. Likewise, much of the attention during the time of a loss is on the mother; the father is expected to be her main support but is often not acknowledged as grieving, too. The response of fathers can be more variable than that of mothers and depends on the level of identification with the pregnancy. With early miscarriage or ectopic pregnancy, some fathers have not yet developed a strong investment in the wished-for child. However, many fathers are profoundly affected and do grieve deeply for a perinatal loss, yet their feelings are often ignored (O’Leary & Thorwick, 2006).

Fathers are distressed by the grief of the mother and often feel helpless as to how to help her with the intense pain (O’Leary & Thorwick, 2006). Some fathers appear stoic and unemotional to maintain the societal expectation that they are “strong” for the mother and other family members. It is important to realize that fathers can be experiencing deep pain beneath their calm and quiet appearance and need help in acknowledging these feelings. Because many fathers do not easily share feelings or ask for help, special efforts are needed to help them realize that they too have a right to receive support from others as they grieve.

During this time of acute distress parents face the first task of grief, accepting the reality of the loss. The pregnancy has ended or the baby has died, and their life has changed. Parents are often required to make many decisions, such as naming the infant and making funeral arrangements during this period when normal functioning is impeded and decisions are difficult to make. This can be especially painful and difficult for young couples who have limited or no previous experience with death. Grandparents are often called on to help make difficult decisions regarding funeral arrangements and/or disposition of the body because they have more life experience with taking care of these painful, yet required arrangements. However, some well-meaning grandparents and other family members try to take over all the decisions that must be made. It is critical for the nurse to remember that a very important role is always to be a client advocate and that the parents themselves should approve the final decisions.

Intense Grief

The phase of intense grief encompasses many difficult emotions as the parents work through their pain and adjust to life without the wished-for child. In the early months after the loss parents often experience feelings of loneliness, emptiness, and yearning. The mother may report that her arms ache to hold or nurse her baby and that she wakes to the sound of a baby crying. When her milk comes in, it is particularly poignant when there is no baby to breastfeed. Mothers and fathers can be preoccupied with thoughts about the wished-for child. Some women cope with these feelings by avoiding memories and by not talking about the baby, whereas others want to reminisce and discuss their loss over and over. Deciding what to do about the nursery and baby clothes is particularly difficult. Some women want the room taken down before they go home, whereas others want the room left intact until they have had time to grieve their loss. It is not unusual for a grandparent or other family member to want to rush home to take down the nursery with the thought that they would be sparing additional painful grief. In fact, their actions might only complicate the grief if parents were not involved in the decision. The bereaved parents, in their own time frame, must go through these types of experiences so that healing can take place.

During this phase of intense grief, guilt can emerge from the deep feelings of helplessness related to the inability to have somehow prevented the pregnancy loss or the death of the infant. Mothers are particularly vulnerable to feel guilt because of their sense of responsibility for the well-being of the fetus and baby. With many perinatal losses there is no clear cause of the event, leaving the woman to speculate about what she might have done or not done to cause the loss. Guilt can be intense if a mother thinks she is being punished for some unrelated event such as having had a prior induced abortion. Such self-blame is torture for mothers, and they need repeated emotional reassurance that they were not at fault. Guilt can occur when the mother or father begins enjoying life and experiencing happiness again despite the loss of the infant.

Other common responses during this phase of grief are anger, resentment, bitterness, or irritability. Anger is particularly poignant if the loss is perceived as senseless, and there is a need to blame others. Anger can be focused on the health care team who failed to save the pregnancy or infant. Some parents direct their anger toward God, who they blame for allowing the loss to occur. This can lead to a spiritual crisis. Anger also occurs toward family, friends, and peers when they do not provide the support bereaved parents need and want. Some parents focus their resentment on parents who do not appreciate their children or who neglect and abuse them. A sense of bitterness or generalized irritability, rather than frank anger, can be another response.

Fear and anxiety can occur during the grief process as a profound worry that something else bad might happen to another. Fear and anxiety are particularly poignant when the couple considers another pregnancy (DeBackere, Hill, & Kavanaugh, 2008). Some parents, especially mothers, are almost obsessed with the desire to become pregnant again; others struggle with whether they can cope with another potential loss.

Deep sadness and depression occur when the parent faces the full awareness of the reality of the loss. This often occurs several months after a perinatal loss and can continue for some time. Sadness and depression are often accompanied by disorganization and problems with cognitive processing. This leads to behavioral changes such as difficulty in getting things done, an inability to concentrate, restlessness, confused thought processes, difficulty in solving problems, and poor decision making. Disorganization and depression often cause difficulties in keeping up with work and family expectations. Additionally parents returning to work face issues such as handling well-meaning but painful comments or the silence of coworkers.

Physical symptoms of grief include fatigue, headaches, dizziness, or backaches. Parents are at risk for developing health problems, such as colds or hypertension. The grieving process makes it difficult for bereaved parents to sleep. Their appetites can be depressed or voracious. Lack of sleep and inadequate nutrition and fluids can complicate other grief responses.

Grief responses are very personal, ongoing, and difficult to endure. Some parents suppress or deny their feelings because of societal indifference toward pregnancy loss and infant death. Suppression of feelings may, on the surface, be more socially acceptable. However, denying the pain of grief can lead to eventual physical and emotional distress or illness. Many parents, especially mothers, want to tell their story over and over. This helps them actualize the loss and face their feelings. Sometimes parents begin to think they are the only individuals who have ever had such a rough time and that they are going crazy. Although bereaved parents have ups and downs for many months and even years after a child’s death, few parents actually become mentally ill or commit suicide. Knowing that their feelings are normal and that others have felt the same is helpful. The grief process during this phase is often difficult for fathers (O’Leary & Thorwick, 2006). Some may continue to have difficulty sharing their feelings. A rift can occur if one parent, usually the mother, wants to talk about the loss and pain, and the other parent, often but not always the father, withdraws. Other signs of problems include reliance on alcohol and drugs, extramarital affairs, prolonged hours at work, and overinvolvement in activities outside the home as an escape.

Reorganization

From the time of the pregnancy loss or infant death, parents attempt to understand “why?” This leads to a long and intense search for meaning. At first the “why” is focused on the cause of death. Finding few good answers, parents focus next on “why me, why mine?” These questions lead some parents into an existential search about the meaning of life and death. “What does my loss mean to my life?” “What is life all about?” “What do I do with the rest of my life?” This search continues into the phase of reorganization and can lead to profound changes in the parents’ views about the fragility of life.

Time helps to ease slowly the painful feelings of grief. Although some grief models focus on “letting go” as an important step in the grief process, bereaved parents often want to hold on to their relationship with their child (Davies, 2004). With perinatal loss, however, parents have few, if any, memories of their infant to provide a balance to their devastating loss, and this adds to their pain.

Over time the feelings become less painful. Reorganization occurs when the parent is better able to function at home and work, experiences a return of self-esteem and confidence, can cope with new challenges, and has placed the loss in perspective. Reorganization begins to peak sometime after the first year as parents begin to achieve the task of moving on with their lives. Enjoying the simple pleasures of life without feeling guilty, nurturing self and others, developing new interests, and reestablishing relationships are signs of moving on. For some women and families, another pregnancy and the birth of a subsequent child is an important step in moving on with their lives (Swanson, Connor, Jolley, Pettinato, & Wang, 2007). However, the term recovery is never used because the grief related to perinatal loss can continue in varying degrees for life.

Parents have shared that they will never forget the baby who has died, and they are not the same people as before the loss. The term bittersweet grief refers to the grief response that occurs with reminders of the loss. This typically happens at special anniversary dates related to the loss. Grief feelings also can be triggered during subsequent pregnancies and after birth (Côté-Arsenault & Marshall, 2000; DeBackere et al., 2008).

Resuming the sexual relationship is an important aspect of recovery, but it can be very complicated. Many parents are comforted with the belief that their babies were conceived in love, lived in love, and died in love. Their love and intimacy created this child, and parents can believe that they will never experience joy and closeness again. Once the doctor has given permission for resumption of sexual activities, parents can find it emotionally very difficult. Some couples have an increased need for sexual activity in an attempt for closeness and healing, whereas others have a decreased desire for sexual intimacy. It is important that parents are aware of some possible deep need from inside themselves to stop the emotional pain. Difficulties arise when the needs of the couple differ.

Sexuality also brings with it decisions about a future pregnancy. The decision to have another child involves intense and conflicting emotions (DeBackere et al., 2008). Parents want to be hopeful about having a normal healthy child but also have fears about having another loss. A deep fear of experiencing the pain of loss again can make the resumption of sexual activity difficult. These ambivalent feelings are normal, and couples will find themselves moving back and forth between the emotions of exhilaration and fear. The subsequent pregnancy after a loss is often filled with guarded emotions and great anxiety (Côté-Arsenault & Donato, 2007). The excitement that many others experience with a pregnancy is very different for previously bereaved parents (Côté-Arsenault, 2007). This distress can continue even after the birth of a healthy infant and affect maternal attachment to the new baby (Armstrong, 2007). Fathers also report anxiety about the outcome of the next pregnancy and increased their vigilance (Armstrong, 2007; O’Leary & Thorwick, 2006). Couples sometimes mark the progress of the pregnancy in terms of fetal development, waiting anxiously until the number of weeks of the previous loss have passed. The fear of repeated loss is especially high after a stillbirth.

Family Aspects of Grief

It is extremely important for nurses taking care of grieving parents to keep in mind that they have an entire family to minister to, including especially grandparents and siblings. Grandparents have hopes and dreams for a grandchild; these have been shattered. The grief of grandparents is often complicated by the fact that they are experiencing intense emotional pain by witnessing and feeling the immense grief of their own child. It is extremely difficult to watch their son or daughter experience unimaginable emotional trauma with very few ways to comfort and end their pain. As a result, the grief response can be complicated or delayed for grandparents. Some grandparents experience immense “survivor guilt” because they feel the death is out of order as they are alive and their grandchild has died.

The siblings of the expected infant also experience a profound loss. Most children have been prepared for having another child in the family once the pregnancy is confirmed. These children come in all ages and stages of development, and the nurse must consider this to understand how the child views the event and their loss experience. Given that young children are now often kept fully aware about a pregnancy and an expected brother or sister, they can have a great deal of difficulty understanding why there suddenly is no baby or the baby has not come home (Limbo & Kobler, 2009). A young child will respond to the reactions of his or her parents, picking up on the fact that they are behaving differently and are extremely sad. This can cause clinging, altered eating and sleeping patterns, or acting-out behaviors, yet it is a time when parents have limited patience for responding to and meeting the needs of the child. Older children have a more complete understanding of the loss. School-aged children can be frightened by the entire event, whereas teens can understand fully but feel awkward in responding.

Nurses can help to include siblings in grieving rituals to the extent the parents and the child feels comfortable. They may need to see the baby to actualize the loss. Nurses need to have a basic understanding about how children view death and grieve to reach out to siblings in an appropriate and sensitive manner. Nurses also need to help parents recognize and be sensitive to the grief of siblings, include them in family rituals, and keep the baby alive in the family memory. Nurses can direct parents to the website, “Children’s Understanding of Death” (http://sids-network.org/sibling/sibunderstanding.htm) for information about helping children cope with infant death.

Care Management

Nursing care of mothers and fathers experiencing a perinatal loss begins the first time the parents are faced with the potential loss of their pregnancy or death of their infant. Supportive interventions are important when parents are anticipating loss, at the time of the loss, and after the parents have returned home (see the Nursing Process box).

In order to provide competent, compassionate, individualized care to grieving parents and their families, the nurse first conducts a thorough assessment. Several key areas to address include the following:

• The nature of the parental attachment with the pregnancy or infant, the meaning of the pregnancy and infant to the parent, and the related losses they are experiencing. Each pregnancy and birth has a special meaning to parents. Whether a woman has experienced a miscarriage or ectopic pregnancy, stillbirth, or death of an infant, it is important to gain some understanding of parents’ perceptions of their unique loss. The meaning of the loss is determined by familial and cultural systems of the parents. Feelings about perinatal loss can range from feeling devastated to feeling relieved (Corbet-Owen & Kruger, 2001). Listening to parents tell their story and being sensitive to the language used to describe their experience can help nurses gain an understanding of the meaning of the loss. Open-ended questions are helpful: “Tell me about your labor and birth with Mia.” Or “When did you know you were miscarrying?” Mothers who have had a previous pregnancy loss may feel less attached, which can increase their feelings of guilt when a loss occurs.

• The circumstances surrounding the loss, including the level of preparation for the loss and the parents’ level of understanding about the cause of the loss or death, and any related unresolved issues. While listening to the parents’ stories, it is important to uncover any special experiences that may make their losses even more poignant. A history of infertility, repeated pregnancy losses, a previous stillbirth, or infant death can make this loss even more painful. In addition, other life circumstances such as illness of another family member, loss of a job, or other family stresses can increase the distress of parents. It also is helpful to know whether the mother and father perceived the loss to be totally unexpected, or whether they had some forewarning or preparation.

• The immediate response of the mother and father to the loss, whether their responses are complementary or problematic, and how their responses match with their past experiences, personalities, and behavioral and cultural backgrounds. An understanding of the usual responses to grief described earlier can be helpful in attempting to understand the unique grief responses of the mother and the father and other family members. As nurses work with families, they can uncover information about how the individual or family responded to a previous loss, or a personality or behavioral trait that may be involved in their responses to this grief. In particular, it is important to know about any history of infertility, previous pregnancy losses, or infant deaths and evaluate how that might affect parental responses. It also is important to be sensitive to different expectations during grief for men and women from different cultural groups (see section on cultural and spiritual needs of parents later in this chapter).

• The social support network of the parent (e.g., extended family, friends, coworkers, church) and the extent to which it has been activated. Support during a perinatal loss is important to most parents; however, it is important to assess the amount of support and the type of support that the parents desire. Some prefer to handle the tragedy alone for a time. Others want assistance in calling other family members, friends, and clergy to be with them and to help them with decisions.

Nursing care for grieving families should be comprehensive. It can be complex as the nurse considers the shock and numbness of the bereavement process and the varied grief responses of the parents and other family members during hospitalization. (See Nursing Care Plan on p. 947.)

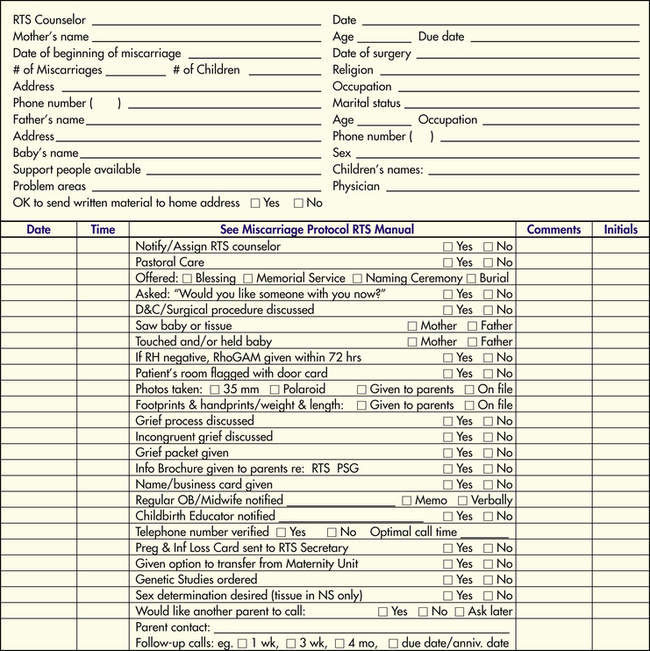

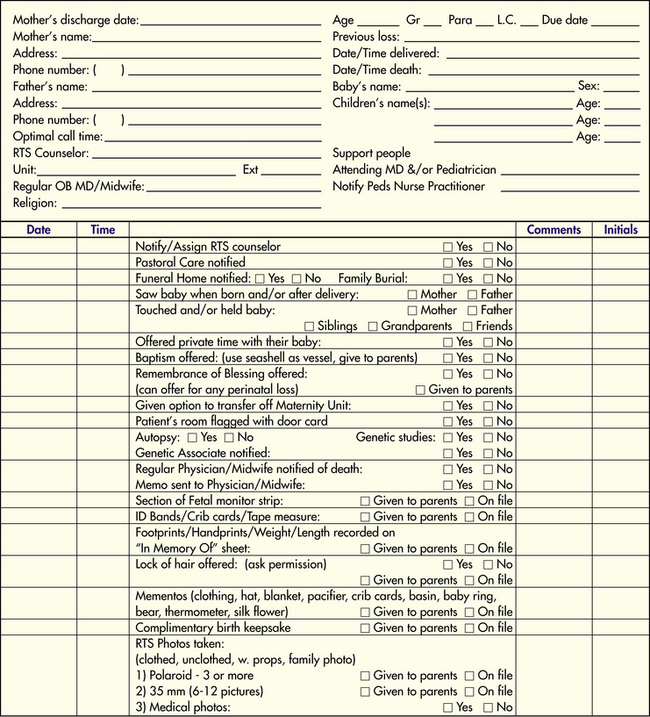

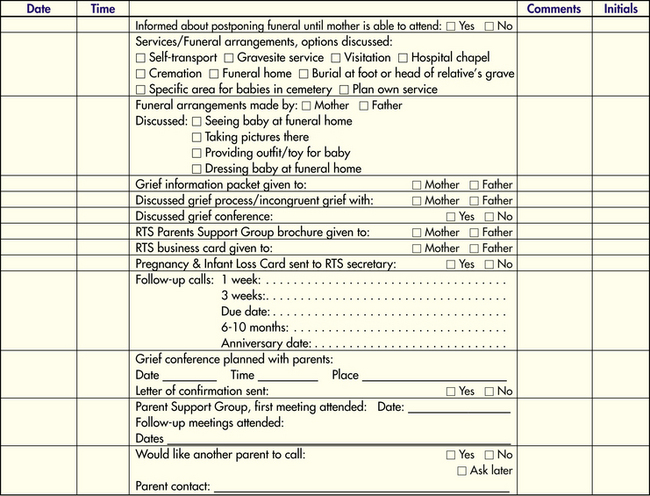

Checklists can be used to facilitate comprehensive care. Many hospitals use checklists for providing care, mobilizing members of the multidisciplinary health care team, communicating options the family has chosen, and keeping track of all the details in meeting the needs of bereaved parents (Figs. 38-1 and 38-2). Such checklists can be a permanent part of the chart. Documentation in the nursing notes of primary concerns, grief responses, health teaching, health care advice, and any referrals of the mother or other family members is essential to ensure consistency and continuity of care.

FIG. 38-1 Sample checklist for assisting parents experiencing miscarriage/ectopic pregnancy. (Used with permission of Bereavement Services. Copyright Lutheran Hospital—La Crosse, Inc., A Gundersen Lutheran Affiliate, La Crosse, WI.)

FIG. 38-2 Sample checklist for assisting parents experiencing stillbirth or newborn death. (Used with permission of Bereavement Services. Copyright Lutheran Hospital—La Crosse, Inc., A Gundersen Lutheran Affiliate, La Crosse, WI.)

Interventions and support for parents from the nursing and medical staff after a perinatal loss or infant death are extremely important in their healing. Although parents often cannot recall details of their experiences at the time of death, they may recall vividly minor events that were perceived as particularly painful or particularly helpful. However, care must be individualized for each parent and family. Parents whose infants were stillborn have noted that nurses were important in supporting them during periods of chaos, helping them meet and separate from the baby, and providing bereavement support (Saflund, Sjogren, & Wredling, 2004). Nurses also have an important role in helping parents who experience miscarriage, fetal death, or abortion related to a lethal fetal diagnosis (Breeze et al., 2007; Leuthner & Jones, 2007; Murphy & Merrell, 2009). Their grief can be overlooked because they are often treated as outpatients or have very brief hospital stays.

Furthermore, nurses should consider the cultural and spiritual beliefs and practices of individual parents and families. The interventions discussed later are general ideas about what may be helpful to parents.

Help the Mother, the Father, and Other Family Members Actualize the Loss

When a loss or death occurs, the nurse should be sure that parents have been honestly told about the situation by their physician or others on the health care team. It is important for their

nurse to be with them during this time. With early pregnancy loss, it is recommended that the terminology “miscarriage” be used consistently (Cameron & Penney, 2005). With infant death, caregivers should use the words “dead” and “died,” rather than “lost” or “gone,” to assist the bereaved in accepting this reality. Parents need opportunities to tell their story about the events, experiences, and feelings surrounding the loss. This can help them come to terms with the reality of their loss. Listening to their pain and allowing time for them to absorb the information is important.

One way of actualizing the loss is to tell the parents the sex of the baby and give them the option of naming the fetus or to help them to name an infant who has died. Choosing a name helps make the baby a member of their family so that the baby can be remembered in a special way. Once the baby is named, the nurse should use the name when referring to the baby. Although naming can be helpful, it is important not to create the sense that the parents must name the “baby,” especially in the case of an early pregnancy loss.

Research evidence supports the importance of parents’ seeing or holding their fetus or infant (Gold et al., 2007). Most parents find this experience valuable and many indicate that they would have liked more time or more opportunities to do so. Seeing and holding the fetus or baby is important because it can help parents face the reality of the loss, reduces painful fantasies, and facilitates the grieving process. It should be noted, however, that while this is a beneficial experience for most parents, it can increase feelings of sadness about their loss and can even be traumatic for some individuals (Badenhorst & Hughes, 2007). Parents should be allowed to choose whether or not they want to see and/or hold their fetus or baby. They should never made to feel they “should” see or hold their baby when this is something that they do not really want. Encouraging reluctant parents to hold or see their dead child by telling them that not seeing the child could make mourning more difficult is inappropriate. Obviously, this subject must be approached very carefully. The nurse might ask question such as, “Some parents have found it helpful to see their baby. Would you like time to consider this?” is helpful Because the need or willingness to see also may vary between the mother and father, it is extremely important to determine what each parent really wants. This should not be a decision made by one person or a decision made for the parents by grandparents or others. It is a good policy for the nurse to first tell them about this option and then give them time to think about it. Later the nurse can return and ask each parent individually what he or she decided.

In preparation for the visit with the baby, parents appreciate explanations about what to expect. Descriptions of the baby’s appearance are important. For example, babies can have red, peeling skin resembling severe sunburn, dark discoloration similar to bruises, molding of the head that makes the head look soft and swollen, or birth defects. The nurse should make the baby look as normal as possible, and remember that parents see their baby with different eyes from health care professionals. Bathing the baby, applying lotion to the baby’s skin, combing hair, placing identification bracelets on the arm and leg, dressing the baby in a diaper and special outfit, sprinkling powder in the baby’s blanket, and wrapping the baby in a pretty blanket convey to the parents that their baby has been cared for in a special way. If the baby has been in the morgue, the nurse can place him or her underneath a warmer for 20 to 30 minutes and wrap the infant in a warm blanket before taking the infant to the parents. Cold cream rubbed over stiffened joints can help in positioning the baby. The use of powder and lotion stimulates the parents’ senses and provides pleasant memories of their baby.

When bringing the baby to the parents, it is important to treat the baby as one would a live baby. Holding the baby close, touching a hand or cheek, using the baby’s name, and talking with the parents about the special features of their child conveys that it is all right for them to do likewise. If a baby has a congenital anomaly, the nurse can help to desensitize the family by pointing out aspects of the baby that are normal. Nurses can help parents explore the baby’s body as they desire. Parents often seek to identify family resemblance. A good question might be: “Who in your family does Michael resemble?”

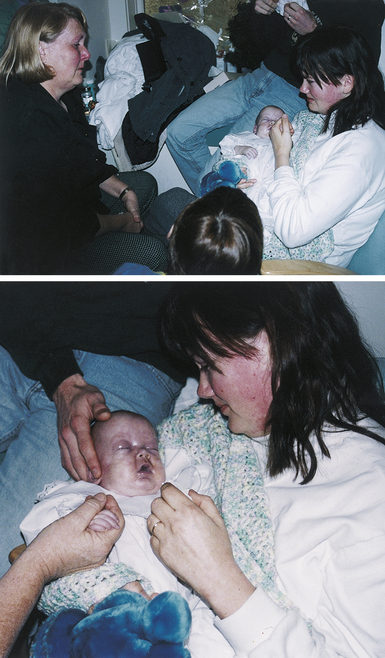

Some families like to have the opportunity to bathe and dress their baby. Although the skin is fragile, parents can still apply lotion with cotton balls, sprinkle powder, tie ribbons, fasten the diaper, and place amulets, medallions, rosaries, or special toys or mementos in their baby’s hands or alongside their baby. Volunteers in communities across the country make special burial clothes to give parents at this difficult time. Parents may want to perform other parenting activities, such as combing the hair, dressing the baby in a special outfit, wrapping the baby in a blanket, or placing the baby in a crib (Fig. 38-3)

Parents need to be offered time alone with their baby. They also need to know when the nurse will return and how to call if they should need anything. When possible, the family is placed in a private room with a rocking chair for the parents to sit in when holding their baby. This offers the mother and father special time together with their baby and with other family members (Fig. 38-4). Marking the door to the room with a special card helps remind the staff that this family has experienced a loss (Fig. 38-5).

FIG. 38-5 Door card for room of mother who has had a perinatal loss. (Used with permission of Bereavement Services. Copyright Lutheran Hospital—La Crosse, Inc., A Gundersen Lutheran Affiliate, La Crosse, WI.)

It is difficult to predict how long and how often parents will need to spend time with their baby. These moments are the only ones they will have to parent their child while their child’s physical presence is still with them. Some parents need only a few minutes; others need hours. It is extremely painful for some parents to say good-bye to their baby. They will tell the nurse when they are ready verbally and nonverbally. Nonverbal cues include when parents are no longer holding their child close to them or have placed the baby back in the crib. Grandparents should have the same opportunities to hold, rock, swaddle, and love their grandchildren so that their grief is started in a healthy way.

Help the Parents with Decision Making

At a time when they are experiencing the great distress of a perinatal loss, and especially if the loss was of an infant, parents have many decisions to make. Mothers, fathers, and extended families look to the medical and nursing staff for guidance in discerning what must be done immediately and what can wait and in understanding their options relative to each decision. Thus it is a primary responsibility of the nurse to help them and to advocate for them, because choices made during the time of their loss will influence their memories for a lifetime.

One decision might be related to conducting an autopsy. An autopsy can be very important in answering the question “why” if there is a chance that the cause of death can be determined. This information can be helpful in processing grief and perhaps preventing another loss. However, asking parents about an autopsy takes the ulmost of sensitivity to personal, cultural, and religious views about an autopsy. (For a complete description of multicultural issues in requesting an autopsy, see Chichester [2007].) Some religions prohibit autopsy or limit the choice to times when it may help prevent another loss. Options for the type of autopsy, such as excluding the head, are available to parents. Note that the cost of an autopsy must be considered because it is not covered by insurance and is expensive. Some parents feel that their baby has been through enough and prefer not to have further information about the cause of death. In any event, parents need time to make this decision. There is no need to rush them, unless there was evidence of contagious disease or maternal infection at the time of death.

Organ donation can be an aid to grieving and an opportunity for the family to see something positive associated with their experience. The federal Gift of Life Act and HCFA-3005-F, enacted in 1998, shifted the responsibility for determining organ donation potential from the hospital staff to the state’s organ procurement organization (OPO). States and hospitals have clear procedures for how and when to call the OPO. Generally, if a death certificate is issued, a call must be made to the OPO. Once contacted, they will decide whether to talk to the family, and either an OPO representative or a designated requester will contact them. This allows requests to be made by trained personnel in a consistent and compassionate manner. The most common donation is of corneas; donation of corneas from a baby can occur if the baby was born alive at 36 weeks of gestation or later.

Another important decision relates to spiritual rituals that can be helpful and important to parents. Support from the clergy should be offered to all parents. Parents may wish to have their own pastor, priest, rabbi, or spiritual leader contacted, or they may wish to see the hospital’s chaplain. They may choose to do neither. Members of the clergy can offer the parents the opportunity for baptism when appropriate. Other rituals that can be important include a blessing, a naming ceremony, anointing, ritual of the sick, memorial service, or prayer.

One of the major decisions parents must make has to do with disposition of the body. Parents should be given information about the choices for the final disposition of their baby, regardless of gestational age. Nurses must be aware, however, of cultural and spiritual beliefs that can dictate the choices of parents, issues related to the cost of burial, alternatives to burial, and state laws related to burial. A baby younger than 20 weeks of gestation is considered a product of conception, whereas embryos, uterine tubes removed with an ectopic pregnancy, and tissue from a pregnancy obtained during a dilation and curettage are considered tissue. Many hospitals will make arrangements for the cremation of these infants or tissue. The nurse should know the hospital’s policies and procedures and answer the parents’ questions honestly. In most states if a fetus is at least 20 weeks and 1 day of gestational age or is born alive, it is the parents’ responsibility to make the final arrangements for their baby, although some hospitals will offer free cremation. In this case, the family does not receive the ashes.

Final disposition of all identifiable babies, regardless of gestational age, includes burial or cremation. Depending on the cemetery’s policies, babies in caskets or the ashes from cremated babies can be buried in a special place designated for babies, at the foot of a deceased relative, in a separate plot, or in a mausoleum. Ashes also can be scattered in a designated area; many states have regulations regarding where ashes can be scattered. A local funeral director or a state’s Vital Statistics Bureau should have information about the state’s rules, codes, and regulations regarding live births, burial requirements, transportation of the deceased by parents, and cremation.

In making final arrangements for their baby, some parents want a special service. They can choose to have a service in the hospital chapel, visitation at a funeral home or their own home, a funeral service, in a church or a graveside service. Parents can make any of these services as special, personal, and memorable as they like. They can choose special music, poetry, or prose written by themselves or others.

If the family has decided on a funeral and burial, they still have decisions about which funeral home to call and where to bury the baby. Many couples live in an area distant from their family homes, and they may want to bury their child in their hometown or family cemetery. If the family desires cremation, they may want to have the option of obtaining the ashes. It is important to determine whether this will be done by the facility conducting the cremation.

Parents’ hopes, dreams, self-esteem, and role expectations have been shattered with a perinatal loss; thus they have many needs. Unmet needs can form the basis of “if only” that may plague a mother or family for a lifetime and can be the foundation for the development of complicated bereavement. However, it is difficult for parents to know exactly what they can expect or what they need; thus the nurse as an advocate should lead by offering various options to meet specific needs. When a mother or family is able to verbalize needs, it is extremely important for the nurse to respond positively and to do everything to see that the request is met.

Families become unaware of time frames and do not care about the change of shifts or any needs the hospital system might have in “moving things along.” When families are pushed or rushed into making decisions, in most cases, they make a decision in response to the health care system’s needs, not their own. Actions such as naming the baby, seeing and holding the baby, disposition of the body, and funeral arrangements should never be rushed. In some cases, the mother is discharged home before these decisions are made. Then the family can think about them in the comfort of their home and contact the hospital in the following days to give their answers.

Help the Bereaved Parents Acknowledge and Express Their Feelings

One of the most important goals of the nurse is to validate the experience and feelings of the parents by encouraging them to tell their stories and listening with care (Corbet-Owen & Kruger, 2001). At the very least, the nurse should acknowledge the loss with a simple but sincere comment such as, “I’m sorry about the baby.” Helping the parents to talk about their loss and the meaning it has for their lives and to share their emotional pain is the next step. Because nurses tend to be very focused on the physical and emotional needs of the mother, it is especially important to ask the father or partner directly about his or her views of what happened and the associated feelings of loss.

The nurse should listen patiently during the story of loss or grief; however, listening can be difficult and painful for the caregiver. The feelings and emotions of expressed grief can overwhelm health care professionals. Being with someone who is terribly sad and crying or sobbing can be extremely difficult. The initial impulse to reduce one’s sense of helplessness is to say or do something to reduce their pain. Although such a response seems supportive at the time, it can stifle the further expression of emotion. Bereaved parents have identified many unhelpful responses made to them by well-meaning health care professionals, family, and friends. The nurse should resist the temptation to give advice or use clichés in offering support to the bereaved (Box 38-2). Nurses need to be comfortable with their own feelings of loss and grief to support and care for bereaved persons effectively. The nurse should have a presence of self, the willingness to be alongside, quietly supporting the bereaved in whatever expressions of feelings or emotions are appropriate for them. This presence leaves parents feeling that they were cared for. Leaning forward, nodding the head, and saying “Uh-huh” or “Tell me more” is often encouragement enough for the bereaved person to tell his or her story. Sitting through the silence can be therapeutic; silence gives the bereaved person an opportunity to collect thoughts and to process what he or she is sharing. Furthermore, careful assessment is important before using touch as a therapeutic technique. For some, touch is a meaningful expression of concern, but for others it is an invasion of privacy.

Bereaved parents have many questions surrounding the event of their loss that can leave them feeling guilty. This is particularly true for mothers. Such questions include “What did I do?” “What caused this to happen?” “What do you think I should have, could have done?” Part of the grief process for bereaved parents is figuring out what happened, their role in the loss, why it happened to them, and why it happened to their baby. The nurse should recognize that the answers to these questions must be answered by the bereaved themselves; it is part of their healing. For example, a bereaved mother might ask, “Do you think that this was caused by painting the baby’s room?” An appropriate response might be, “I understand you need to find an answer for why your baby died, but we really don’t know why she died. What are some of the other things you have been thinking about?” Trying to give bereaved parents answers when there are no clear answers or trying to squelch their guilt feelings by telling them they should not feel guilty does not help them process their grief. In reality, many times there are no definite answers to the question of why this terrible thing has happened to them. However, factual information, such as data about the frequency of miscarriages in pregnant women or the fact that there usually is no clear cause of a stillbirth, can be helpful.

Feelings of anger, guilt, and sadness can occur immediately but often become more problematic in the early days and months after a loss. When a bereaved person expresses feelings of anger, it can be helpful to identify the feeling by simply saying, “You sound angry,” or “You look angry.” The nurse’s willingness to sit down and listen to these feelings of anger can help the bereaved move past those surface feelings into the underlying feelings of powerlessness and helplessness in not being able to control the many aspects of the situation.

Normalize the Grief Process and Facilitate Positive Coping

While helping parents share their feelings of pain, it is critical to help them understand their grief responses and feel they are not alone in these painful responses. Most parents are not prepared for the raw feelings that they experience or the fact that these painful, complex feelings and related behavioral reactions continue for many weeks or months. Thus reassuring them of the normality of their responses and preparing them for the length of their grief is important.

The nurse can help parents prepare for the emptiness, loneliness, and yearning; for the feelings of helplessness that can lead to anger, guilt, and fear; and for the cognitive processing problems, disorganization, difficulty making decisions; and sadness and depression that are part of the grief process. Many parents have reported feelings of fear that they were going crazy because of the many emotions and behavioral responses that leave them feeling totally out of control in the months after the loss.

It is essential for the nurse to reassure and educate bereaved parents about the grief process, including the physical, social, and emotional responses of individuals and families. Pamphlets about parental grief that are sensitive and brief can be very helpful (Geller, Psaros, & Kerns, 2006). Offering health teaching on the bereavement process alone is not enough, however. In the initial days after a loss, other strategies might include follow-up phone calls, referral to a perinatal grief support group, or providing a list of publications or websites intended for helping parents who have experienced a perinatal loss (Geller et al., 2006). Some important websites include www.compassionatefriends.org, www.resolve.org, www.mend.org, www.sidscenter.org, and www.natonalshareoffice.com. As with any referral, however, the nurse should first review the materials or the websites for accuracy and appropriateness.

To reduce relationship problems that can occur in grieving couples, nurses help them understand that they may respond and to grieve in very different ways (Abboud & Liamputtong, 2005). Discongruent grieving can lead to serious marital problems and can be a risk factor for complicated bereavement. It is important to remind the couple of the importance of being understanding and patient with each other. A father may need encouragement to be able to share his grief with his wife, because of the desire to protect the woman from his pain or the need to appear strong.

Nurses can reinforce positive coping efforts and attempt to prevent negative coping (Abboud & Liamputtong, 2005). They can remind the parents of the importance of being patient and being good to themselves during the grief process. Additional suggestions are to encourage attempts to resume normal activities; reinforce and encourage positive ways to hold on to memories of the pregnancy or baby, while letting go; and help the parent to organize a plan for daily activities, if needed. In particular, nurses should discourage dependence on drugs and alcohol.

Meet the Physical Needs of the Postpartum Bereaved Mother

Coping with loss and grief after childbirth can be an overwhelming experience for the woman and her family. One particularly difficult aspect of the loss is hearing the sound of crying babies and witnessing the happiness of other families on the unit who have given birth to healthy infants. The mother should have the opportunity to decide if she wants to remain on the maternity unit or to move to another hospital unit. The nurse should help her to understand the positive and negative aspects of each choice. Postpartum care as well as grief support may not be as good on another hospital unit where the staff members are not experienced in postpartum and bereavement care.

The physical needs of a bereaved mother are the same as those of any woman who has given birth. The cruel reality for many bereaved mothers is that their milk comes in with no baby to nurse, their afterpains remind them of their emptiness, and gas pains feel as though a baby is still moving inside. The nurse should ensure that the mother receives appropriate medications and other interventions to reduce these physical symptoms. Adequate rest, diet, and fluids must be offered to replenish her physical strength.

Mothers need postpartum care instructions on discharge. They also need ideas about how to cope with problems with sleep such as decreasing food or fluids that contain caffeine, limiting alcohol and nicotine consumption, exercising regularly, and using strategies to promote rest such as taking a warm bath or drinking warm milk before bedtime, doing relaxation exercises, listening to restful music, or a having a massage.

Assist the Bereaved in Communicating with, Supporting, and Getting Support from Family

Providing sensitive care to bereaved parents means including their families in the grief process. Grandparents and siblings are particularly important when a perinatal loss has occurred. However, it is up to the parents to decide to what extent they want family involved in their grief process. If it is the parents’ desire, nursing staff should allow children, grandparents, extended family members, and friends to be involved in the rituals surrounding the death, such as seeing and holding the baby. Such visits afford others the opportunity to become acquainted with the baby, to understand the parents’ loss, to offer their support, and to say good-bye (see Fig. 38-4). This experience helps parents explain to their surviving children about their brother or sister and what death means, offers the children answers to their questions in a concrete manner, and helps the children in expressing their grief. Involving extended family and friends enables the parents to mobilize their social support system of people who will support the family not only at the time of loss but also in the future. Parents also need information about how grief affects a family. They may need help in understanding and coping with the potential differing responses of various family members. Frustrations can arise because of the insensitive or inadequate responses of other family members. Parents may need help in determining ways to let family members know how they feel and what they need.

Create Memories for Parents to Take Home

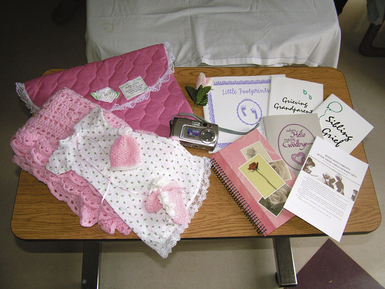

Parents may want tangible mementos of their baby to help them to actualize the loss. Some will bring in a previously purchased baby book. Special memory books, cards, and information on grief and mourning are available for purchase by parents or hospitals or clinics through national perinatal bereavement organizations (Fig. 38-6).

FIG. 38-6 A memory kit assembled at John C. Lincoln Hospital, Phoenix, AZ. Memory kits may include pictures of the infant, clothing, death certificate, footprints, identification bands, fetal monitor printout, and ultrasound picture. (Courtesy Julie Perry Nelson, Loveland, CO.)

The nurse can provide information about the baby’s weight, length, and head circumference to the family. Footprints and handprints can be taken and placed with the other information on a special card or in a memory or baby book. Sometimes it is difficult to obtain good handprints or footprints. Application of alcohol or acetone on the palms or soles can help the ink adhere to make the prints clearer, especially for small babies. When making prints, it is helpful to have a hard surface underneath the paper to be printed. The baby’s heel or palm is placed down first, and the foot or hand is rolled forward, keeping the toes or fingers extended. If the print is not clear or well-defined, tracing around the baby’s hands and feet can be done, although this distorts the actual size. A form of plaster of Paris can also be used to make an imprint of the baby’s hand or foot.

Parents often appreciate articles that were in contact with or used in caring for the baby. This might include the tape measure used to measure the baby, baby lotions, combs or hairbrushes, clothing, hats, blankets, crib cards, and identification bands. The identification band helps the parents remember the size of the baby and personalizes the mementos. The nurse should ask parents if they wish to have these articles before giving them to the parents. A lock of hair can be another important keepsake. The nurse must ask the parents for permission before cutting a lock of hair, which can be removed from the nape of the neck, where it is not noticeable.

For some, pictures are the most important memento. Photographs are generally taken when it has been determined to be culturally acceptable to the family. It does not matter how tiny the baby is, what the baby looks like, or how long the baby has been dead. Pictures should include close-ups of the baby’s face, hands, and feet and photos of the baby clothed and wrapped in a blanket as well as unclothed. If there are any congenital anomalies, close-ups of the anomalies also should be taken. Flowers, blocks, stuffed animals, or toys can be placed in the background to make the picture more special. Parents may want their pictures taken holding the baby. Keeping a camera nearby and taking pictures when parents are spending special time with their baby can provide special memories. Some parents have their own camera or video camera and appreciate having the nurse record them as they bathe, dress, hold, or diaper their baby.

Communicate Using a Caring Framework

Mothers, fathers, and extended families look to the nursing staff for support and understanding during the time of loss. One model for conceptualizing interventions was developed by Swanson based on her research with women experiencing perinatal loss (Swanson, Chen, Graham, Wojnar, & Petras, 2009). The framework identifies five components in a caring concept:

Knowing implies that the nurse has taken the time to understand the perception of the loss and its meaning to the woman and her family. Being with involves how the nurse conveys acceptance of the various feelings and perceptions of each family member. Doing for refers to the activities performed by the nurse that provide physical care, comfort, and safety for the woman and her family. This can include offering pain medication or sitz baths, maintaining the patency of the intravenous line, performing postpartum checks, and giving back rubs. Enabling occurs when the nurse offers the woman and her family options for care. Offers of information, anticipatory guidance, choices for decision making, and support during hospitalization and after discharge help the family feel more in control of a situation in which they feel very much out of control. Enabling raises their self-esteem and allows them to feel more comfortable in asking for options according to their needs for memories and closure, rather than to the nurse’s perception of their needs. Maintaining belief involves encouraging the woman and her family to believe in their own ability to pick up the pieces and begin to heal. The nurse spends time with the family, learns their inner strengths and coping abilities, and points out these inner resources to the family by saying, “I know this is a difficult time for you, but I have seen some of your inner strength and know that you will be able to make it through all of this.”

Be Concerned About Cultural and Spiritual Needs of Parents

Given the growing diversity of the American culture, parents who experience perinatal loss can be from widely diverse cultural, ethnic, and spiritual groups. Many of the emotional responses and suggested interventions in this chapter are based on middle-class European-American views. Although there are likely no particular differences in the individual, intrapersonal experiences of grief based on culture, ethnicity, or religion, there are complex differences in the meaning of children and parenthood, the role of women and men, the beliefs and knowledge about modern medicine, views about death, mourning rituals and traditions, and behavioral expressions of grief. Thus the nurse must be sensitive to the responses and needs of parents from various cultural backgrounds and religious groups. To do this the nurse needs to be aware of his or her own values and beliefs and acknowledge the importance of understanding and accepting the values and beliefs of others who are different or even in conflict (Chichester, 2005). Furthermore, it is critical to understand that the individual and unique responses of a parent to a perinatal loss cannot be entirely predicted by their cultural or spiritual backgrounds. The nurse approaches each mother and father as an individual needing support during a profoundly difficult and distressing life experience.

It would be impossible to address all of the specific differences and needs of parents from diverse cultural and religious groups because of the complexity of this task and the lack of adequate research in this area of practice. Instead, some key concepts are presented and a few examples of areas of particular concern are given. For more detailed discussion of this topic, the reader is referred to an article by Melanie Chichester (2005).

The cultural meaning of children has a strong effect on the response of parents, extended family, and the community when an infant dies or is stillborn. For example, death of an infant or having a stillborn child shakes the foundation of a Jewish family and is surrounded by many cultural traditions, such as naming of the baby, burial, and mourning rituals (Shuzman, 2003). Likewise, in Hispanic families, children are deeply valued and there are many cultural differences associated with perinatal loss. Culture and religious beliefs often affect decision making surrounding stillbirth or death of an infant. Autopsies and cremation are not allowed by some religious groups, except under unusual circumstances (Chichester, 2007). Making a decision to end life-sustaining measures is more difficult for some groups. African-American parents can be less likely than Caucasians to make a decision to stop life-sustaining treatments in a mortally ill infant (Moseley, Church, Hempel, Yuan, Goold, & Freed, 2004). Photographs can conflict with beliefs of some cultures, such as among some Native Americans, Inuit, Amish, Hindus, and Muslims. Families from these cultures should be sensitively offered this opportunity but not pushed into having a photograph taken. In many cultures, decisions do not reside solely in the individual woman or couple but in the extended family. In Hispanic families, the concept of la familia is critical. Family decisions are usually made together and communicated through someone appointed by the family rather than the parents (Chichester, 2005). In Muslim families, the father typically makes the decisions.

Culture and religious beliefs also influence the customs following death. Many religious groups have rituals such as prayers, ritualistic washing and shrouding, or anointing with oil that are performed at the time of death. It is critical to ask parents about their needs as they relate to rituals at the time of and following death. For example, baptism is extremely important for Roman Catholics and some, but not all, Protestant groups. Baptism can be performed by a layperson, such as a nurse, in an emergency situation when a priest cannot be there in a timely fashion. The nurse should inquire about parental beliefs and preferences related to infant baptism. The nurse can offer to contact the hospital chaplain or the family’s own clergy.

Expressions of grief vary across cultures from quiet and stoic to dramatic and hysterical responses. Muslims view death as a part of life and believe a baby’s death is God’s will. The Muslim mother may cry but loud wailing is not acceptable. The tearing of a garment, keria, may be done at the time of a death by Jewish parents. Hispanic parents and family members may be very demonstrative in their grief with loud wailing and weeping (Purnell & Paulanka, 2008). Some African-American women may use self-healing strategies that reflect inner processes, resources, and remedies (Van, 2001).

Provide Sensitive Care At and After Discharge

When leaving the hospital, mothers are often taken out in a wheelchair. This can be a devastating experience for the mother who has experienced a pregnancy loss. Leaving the hospital without a baby in her arms is a very empty and painful experience. It is especially difficult if others are seen leaving with babies; thus the discharge of mothers and fathers who have experienced a perinatal loss should be done with great sensitivity to their feelings. They should not be discharged at a time when other mothers with live babies are leaving. Giving the mother a special flower to carry in her arms can be a thoughtful gesture.

The grief of the mother and her family does not end with discharge; rather it really begins once they return home, attend the funeral, and start to live their lives without their baby. There are numerous models for providing follow-up care to parents after discharge and, although there is no solid evidence from sound clinical trials regarding the benefit of these programs, nonexperimental studies and clinical evaluations suggest these programs are helpful (Côté-Arsenault & Freije, 2004; Reilly-Smorawski, Armstrong, & Catlin, 2002). Programs include hospital-based bereavement teams who provide support during hospitalization and follow-up contacts.

Follow-up phone calls after a loss are helpful to some parents; however, it must be determined which parents do not want a follow-up call. The calls are made at predictably difficult times such as the first week at home, 1 month to 6 weeks later, 4 to 6 months after the loss, and at the anniversary of the death. Families who experienced a miscarriage, ectopic pregnancy, or death of a preterm baby can appreciate a phone call on the estimated date of birth. The calls provide an opportunity for parents to ask questions, share their feelings, seek advice, and receive information to help them in processing their grief.

A grief conference can be planned when parents return for an appointment with their physician or midwife, nurses, and other members of the health care team. At the conference, the loss or death of the infant is discussed in detail, parents are given information about the baby’s autopsy report and genetic studies, and they have opportunities to ask the questions that have arisen since their baby’s death. Parents appreciate the opportunity to review the events of hospitalization, go over the baby’s and/or mother’s chart with their primary health care provider, and talk with those who cared for them and their baby during hospitalization. This is an important time to help parents understand the cause of the loss, or to accept the fact that the cause will forever be unknown. This gives health care professionals the opportunity to assess how the family is coping with their loss and provide additional information and education on grief.

Some parents are very interested in finding a perinatal or parent grief support group. The opportunity to talk with others who have been through similar experiences, share memories of the pregnancy and the baby, and gain an understanding of the normality of the grief process have been generally found to be supportive (Côté-Arsenault & Freije, 2004). Over time, it is possibly the only place where bereaved parents can talk about the wished-for child and their grief. However, not all parents find such groups helpful.

When referring to a group, it is important to know something about the group and how it operates. For example, if a group has a religious base for their interventions, a nonreligious parent would not likely find the group to be helpful. If parents experiencing a perinatal loss are referred to a general parental grief group, they might feel overwhelmed with the grief of parents whose older children have died of cancer, suicide, or homicide. In addition, other parents can help to minimize the grief of parents following a perinatal loss. Thus the focus of the group needs to match the parents’needs.

Provide Postmortem Care

Preparation of the baby’s body and transport to the morgue depend on the procedures and protocols developed by individual hospitals. The Joint Commission (www.jointcommission.org) requires that appropriate care is offered to the body after death. A sensitive and respectful approach for taking the fetus or infant to the morgue is the use of a “burial cradle,” which makes the process more dignified for parents and the nursing staff. A burial cradle is a miniature coffin usually made of Styrofoam or wood (Fig. 38-7).

Postmortem care can be an emotional and sometimes difficult task for the nurse. However, nurses can find that providing postmortem care helps them in their own grief related to a perinatal loss. This is particularly true for neonatal intensive care nurses who have cared for an infant for several hours, days, or weeks.

Special Losses

Prenatal Diagnoses with Negative Outcome

Early prenatal diagnostic tests such as ultrasonography, chorionic villus sampling, and amniocentesis can determine the well-being of the embryo or fetus. Reasons for prenatal testing include history of chromosomal abnormality in the family;

three or more miscarriages; maternal age over 35 years; lack of fetal growth, movement, or heartbeat; and diabetes mellitus or other chronic illnesses. If the health care provider is certain that the baby has a serious genetic defect that will lead to death in utero or after birth (congenital anomalies incompatible with life or genetic disorders with severe mental retardation), the choice of interruption of a pregnancy via dilation and evacuation or induction of labor can be offered (Manning, 2009).

Foreknowledge of a prenatal diagnosis along with perception of the future low health status of the baby as well as multiple congenital problems intensify the grief response (Hunfeld, Tempels, Passchier, Hazebroek, & Tibboel, 1999). The decision to terminate a pregnancy is difficult and can pave the way for feelings such as guilt, despair, sadness, depression, and anger. The parent who decides to continue the pregnancy needs intensive support from the nursing staff. The time of labor and birth can be particularly difficult. The nurse should remember that parents can be grieving for not only the loss of the perfect child but also loss of expectations for their child’s future. Thus nurses should assess how these parents feel about the experience, offer options for their memories as appropriate, and be a support person and good listener. Healing can take place when words can be given to feelings. Perinatal hospice care for parents experiencing prenatal diagnoses of lethal birth defects can be effective in helping families before and after their loss is actualized (Calhoun, Napolitano, Terry, Bussey, & Hoeldtke, 2003). Perinatal hospice does not have to be a formal program, although some do exist. It is the provision of care for families as they plan for the birth and probable death of their baby and involves support, information and resources. If the baby lives more than a few minutes or hours after birth, conventional hospice care may be incorporated into care management of the infant and family (Davis & Helzer, 2011).

Loss of One in a Multiple Birth

The death of a twin or baby in a multifetal gestation during pregnancy, labor, birth, or after birth requires the mother and father (or partner) to parent and grieve at the same time. Such a death imposes a confusing and ambivalent induction into parenthood (Swanson, Kane, Pearsall-Jones, Swanson, & Croft, 2009). They can experience difficulty parenting their surviving child with all the joy and enthusiasm of new parents because their surviving child reminds them of what they have lost. Yet they can also have difficulty fully grieving their loss because their surviving child demands their attention. These parents can be at risk for altered parenting and complicated bereavement.

It is important to help the parents acknowledge the birth of all their babies. The nurse treats the parents as bereaved families, offering all the options previously discussed. With the parents’ consent, photographs should be taken of the babies and parents should be offered the opportunity to hold their babies in their arms and have time to say good-bye to the baby who has died.

It is helpful to warn bereaved parents that well-meaning family members or friends may say, “Well, at least you have the other baby,” implying that there should be no grief because they are lucky to have one at all. Parents need to be able to anticipate insensitivity to their loss and be empowered to say to those people, “That is not how I feel.” By simply setting a boundary on what their feelings are, they are able to acknowledge the baby who died and then have an opportunity to share more about their feelings if they so choose.

Bereaved parents of multiples have special problems in coping with life without their anticipated “extra special” family, telling their surviving child about his or her twin, dealing with the possibility of that child’s feelings of survivor guilt, and deciding on how to celebrate birthdays, death days, or special holidays, or anniversaries of the baby’s death.

Adolescent Grief

Adolescent pregnancy accounts for many births in the United States. Each year, many adolescents experience perinatal loss, particularly as elective abortion or miscarriage. Adolescents grieve the loss of their babies through miscarriage, stillbirth, or newborn death and have significant emotional, social, and cognitive responses (Wheeler & Austin, 2001). These teens need emotional support from the nurses who care for them.

Often nurses and other health care professionals, as well as family members, believe that the adolescent’s loss of her baby was for the best, so that the adolescent can move on with her life. Adolescent girls, then, may not receive the support they need from staff and family. In addition, adolescent girls often do not have the support from the father of the baby as compared with older women who have a perinatal loss; thus there is a great need to provide sensitive care to all adolescents who experience any type of perinatal loss.

The first step for the nurse in caring for a bereaved adolescent is to acknowledge the significance of giving birth, no matter what age the mother might be. Second, the nurse should make additional efforts to develop a trusting relationship in working with the adolescent. Third, the nurse should offer options for saying good-bye, and provide anticipatory guidance, support, and information to meet the adolescent at the point of her need. It can take longer for adolescents to process their grief because of their level of cognitive and emotional maturation. Being patient, saving mementos, and giving the adolescent information on how to contact the nurse are interventions that can help the adolescent accept the reality of the loss and process her grief.

Complicated Grief

Although most parents cope adequately with the pain of their grief and return to some level of normal functioning, some have extremely intense grief reactions that last for a very long time; this response is complicated grief. It is also called complicated bereavement, prolonged grief, pathologic grief, or pathologic mourning (Zhang, El-Jawahri, & Prigerson, 2006). Complicated grief often results when there is sudden or traumatic loss, as occurs with stillbirth or termination of pregnancy due to lethal fetal anomalies (Cacciatore, 2010; Kersting, Kroker, Steinhard, Ludorff, Wesselman, Ohrmann, et al., 2007). Complicated grief differs from what is considered normal grief in its duration and the degree to which behavior and emotional state are affected (Badenhorst & Hughes, 2007). Risk factors for complicated grief include poor social support, history of mental health problems, and a more neurotic pre-loss personality (Badenhorst & Hughes, 2007). A study by Swanson and colleagues (2007) found that women who were still overwhelmed with grief at 1 year, had miscarried again, and/or were not pregnant, experienced six or more negative events in their lives and were distant from their partners.

Persons experiencing complicated grief seem to be in a state of chronic mourning. Evidence of complicated grief includes intense longing and yearning for the deceased, inability to trust others, excessive bitterness, difficulty moving on with one’s life, feeling that life is empty or meaningless, hopelessness, loneliness, intense and continued guilt or anger, relentless depression or anxiety that interferes with role functioning, abuse of drugs (including prescription medications) or alcohol, severe relationship difficulties, high depressive symptomatology, low self-esteem, feelings of inadequacy, and suicidal thoughts or threats years after the loss has occurred (Swanson, 2000; Zhang et al., 2006).