Chapter 9 Aromatic medicine

Introduction

The practice of aromatic medicine has undergone something of a revolution in recent times. It has its origins in France, where essential oils are used internally and externally in larger dosages – and prescribed by those who are trained as medical practitioners. Unfortunately, in the UK there is a great suspicion of those who advocate internal use of essential oils. The fear is based on current legislation, which allows aromatherapy under a single exemption (Section 12(1) of the Medicines Act 1968), effectively treating the use of essential oils as a cosmetic. To advance to claims for therapeutic use would necessitate new legislation, with the fear that current aromatherapeutic uses would be endangered by such revision. The exception permissible at the moment is that trained and qualified herbalists (who are not specifically qualified in the administration of essential oils) may prescribe them for internal use. However, there are aromatherapists who want to hold on to a distinct, yet related, aromatic practice that has little or no association with massage. Given that there are some clients who for various reasons may be unable – or do not wish – to receive massage, the acceptance of aromatic medicine may be an equal opportunities issue, in that it allows access to the use of essential oils for those who, limited by movement, use of limbs or weight, cannot receive what would in the UK be regarded as a ‘normal’ aromatherapy treatment.

Aromatic medicine explained

Aromatic medicine has a number of distinctive elements that distinguish it from aromatherapy as it is practised in the UK:

• It is a therapy in which essential oils are used confidently and efficaciously in the most appropriate way for any presenting condition. The therapy is aromatic because it uses the aromatic, volatile molecules that constitute essential oils.

• It moves beyond the near-homoeopathic normal doses associated with aromatherapy massage and involves a considered response to a particular situation, balancing the presenting condition with a detailed knowledge of essential oils.

• It is built on knowledge of the therapeutic actions of the chemical components that make up essential oils, plus an understanding of the synergy within a single oil and the synergistic potential of blended oils.

It may well be that practitioners of aromatic medicine may have to train to the same level of recognition as herbalists before they will be permitted to prescribe for internal use, but as this is not the entire therapy one should look to building both understanding and confidence in what is a very precise and exacting branch of aromatherapy. There certainly should be no restriction in the intensive topical use. The intensive and specific use of essential oils is a valid expression of aromatherapy and is:

• intensive because of the higher dosage than that used in massage

• intensive because it is more focused on a particular presenting condition

• intensive because of the application of chemistry as the principal tool used in oil selection

• specific because essential oils are engaged for a particular health improvement rather than general wellbeing

• specific because whole-body massage is not always needed or wanted, a more focused application being more necessary.

Those who teach aromatherapy tend to attribute the advent of contemporary aromatherapy to the rediscovery made by Gattefossé of the healing properties of Lavandula angustifolia following a burn. Certainly this was an epiphany, supporting the intensive use of essential oils rather than the English-style aromatherapy, which owes as much to massage (a separate and independent therapy) and the use of carrier oils as it does to essential oils. It is this intensive use that will now be explored.

Beginning with essential oils

Any credible course in aromatherapy has an element of training in the chemistry of essential oils. This provides a foundation on which aromatic medicine is built. A much more detailed knowledge of the chemistry of essential oils and the therapeutic action of the various chemical components gives the use of essential oils in aromatic medicine its distinctiveness.

It is easy to read books on aromatherapy and to have claims for the various benefits from essential oils delineated. Many of these claims are based on traditional use (which is not to be disparaged, in that it has been tested through time – as valid a form of research as any), and without these uses practitioners may not be aware of how a benefit is to be achieved.

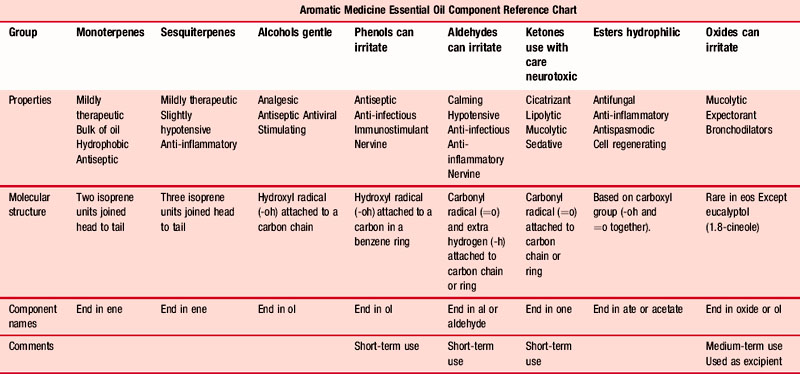

In aromatic medicine, treatment is based on the known and verifiable therapeutic effects of the chemical components found within the oils (Table 9.1), which means that practitioners need a sound working knowledge of the constituent parts of the oils to be used. They also need to be competent enough to work out what the components in the synergy of an essential oil mix will achieve – this can only be understood by detailed training in the chemistry of essential oils.

Table 9.1 Essential Oil Component Reference Chart Diagram (simplified) By kind permission of Penny Price Aromatherapy Ltd (www.penny-price.com)

Perhaps this approach is best illustrated with a recent example that caused a great deal of anxiety. Avian flu was followed by swine flu as a threatened pandemic. The few fatalities that ensued fuelled the hysteria that grew – disproportionately to the risk. The author, when taking a long-haul flight to China for a punishing teaching schedule of 7 days (including 10 flights), responded to the situation by researching the possible aromatic responses, the development in approaches 1–4 below showing the difference between the populist aromatherapy approach and that used in aromatic medicine (see Case 4.4 for the antiviral recipe used).

The available literature indicates that there are some essential oils and related products that are helpful in the treatment of viral conditions.

1. The general aromatherapy literature states that some essential oils are powerfully antiviral. Davis (2000 p. 308), for instance, suggests that bergamot, eucalyptus and tea tree may be used, but does not specify the oils, giving only the common names. These may indeed be effective, but there is no explanation as to how or why they work.

2. There is much more precision in the work of Pénoël and Franchomme. Franchomme (Franchomme & Pénoël 1990 p, 190) suggests that enveloped viruses respond to essential oils having a predominance of terpene-alcohols and phenols, whereas naked viruses respond to oils rich in terpenoid ketones. Pénoël is even more specific, suggesting that α-terpineol and the oxide 1,8-cineole should be administered. The oils suggested, in which these constituents are found, are Laurus nobilis [bay leaf], Eucalyptus radiata [narrow leaf peppermint] and Melaleuca viridiflora [niaouli].

3. Schnaubelt (1997 p. 98) states that terpenes enhance the immune system and metabolic activity by changing the receptors present on cell surfaces, and that new work is being undertaken on the reaction between sesquiterpenes and cell penetration.

4. Price and Price (2007 p.106) suggest that the effectiveness of essential oils may not be dependent upon any specific molecule, but rather on a property common to essential oils, perhaps lipid solubility.

5. The hypericin in Hypericum perforatum [St. John’s wort] has been indicated as inhibiting the development of a virus within an infected cell (Miller 1998). Hypericin is active against several viruses, including cytomegalovirus, the human papilloma virus, hepatitis B and herpes virus. This antiviral activity has been shown in the laboratory and animal studies, but not in human studies. The herb seems to work against viruses by oxidation and its antiviral effect is stronger when exposed to light (as when animals eat the herb). St. John’s Wort was studied in 1991 in people with HIV disease (Freeman & Lawlis, 2001, 415), where the doses were much higher than for treating depression. Patients were given intravenous doses of purified hypericin, but the study was stopped when every white-skinned patient in the trial became very sensitive to light. They developed skin rashes and some could not go outside until after they stopped taking hypericin. The one black-skinned patient did not have this reaction.

It is clear that essential oils are useful in the prevention of viral infection and in its treatment. Reflecting on the research, it appears as if essential oils are able to inhibit the absorption of a virus into a cell, and also to inhibit the reproduction of a virus once it has taken over a cell. On balance, the essential oils most useful are those with a predominance of 1,8-cineole and a significant presence of α-terpineol (although as has been seen, opinion varies and some viruses respond better to some oils than others – see Table 4.5 Ch. 4):

One further essential which should be on this list, effective largely because of the powerful phenol eugenol, is Syzygium aromaticum (flos,) [clove bud].

It would be both possible and fitting to use the essential oil Illicium verum [star anise] as a preventative: the chemistry of the oil reveals that both 1,8-cineole and α-terpineol are present.

Given that viruses are contagious and very inventive in finding hosts, every care must be taken to prevent airborne infection and infection from contact. Diffusing an oil blend using a vaporizer is the best form of prevention. A blend of these oils added to a hand-wash would give further protection. If a viral infection has become established there are many proven and efficacious responses using essential oils, particularly to herpes simplex 1 and to the influenza viruses (Stephen 2010).

As aromatic medicine is a holistic therapy – a treatment tailored to an individual situation; it is a bespoke response in a therapeutic relationship.

Case study 9.1 Eye virus infection

Assessment:

The editor (S Price) has suffered with a recurring herpes simplex virus in her left eye since it first appeared as a dendritic ulcer, necessitating an operation.

The prescription drops had to be collected each time from the hospital 15 miles away, which involved a day away from work (it included a test – and long wait), so she formulated what was to become her Chamomile Eye Drops (CED), a blend of orange flower water, distilled water and essential oil of Chamaemelum nobile (1 drop in 30 mL liquid). The virus disappeared as quickly with this as with the prescribed drops, and was used whenever it recurred (usually after a cold sore) until she retired in 1998.

Ten years later the virus appeared in a stronger form, necessitating a visit to the eye hospital, which prescribed a cream and two lots of drops to be put in separately several times of the day – a veritable nightmare! Hospital visits for check-ups went on for 2 years till the virus eventually ‘went to sleep’ again.

A year later it reappeared after a cold sore while in France, and as the nearest eye hospital was 2 hours away, S decided to try essential oils first – stronger than CED, as her eye was completely cloudy .

A practitioner need not be able to read a GC (gas chromatography) analysis, but should be aware of the principal components of the oils to be used (which should be obtained from a reputable supplier) and not just how an oil is generally made up. The prescription is used uniquely for the therapeutic action of chemical components in a properly calculated synergistic blend, to accomplish a specific objective. It is the whole oil that is used and not an isolate, which is why knowledge of the chemistry leads to awareness of the internal synergy of any resultant blend – as far as this is possible.

Matters of training and safety

Safety when using essential oils remains at the heart of practice; it is also at the heart of the debate between practitioners of aromatherapy and aromatic medicine. Aromatherapists – who may not always be aware of the full extent and possibilities of aromatherapy – will usually concede that intensive topical use of essential oils is sustainable as a practice, while rejecting any form of internal use, even though some schools teach the use of suppositories/pessaries and every aromatherapist uses and advocates gargling. It has been the author’s contention for some time that topical use of essential oils (even in the quantities used in aromatherapy) becomes internal use, insofar as an essential oil is absorbed through the skin into the bloodstream and thence to the rest of the body. In 1877, Fleischer stated that the human skin was totally impermeable to all substances, including gases (Scheuplein et al., 1971 p. 703), but by 1945, Valette was able to demonstrate that essential oils penetrate the skin and goes on to say:

Molecules which have passed through the skin’s epidermis are carried away by capillary blood circulating in the dermis below. This tends to happen easily because the dermis is more or less freely permeable and the capillaries let small molecules pass through their walls. The most permeable regions of the skin to small molecules, including essential oils and vegetable oils, appear to be the palms of the hands and the soles of the feet, forehead, armpits and scalp (cited in Balacs, 1993c: 13)

Each time essential oils are applied to the skin there is a demonstrable presence of the chemical components in the blood. Essential oils molecules are carried into the cardiovascular lymphatic networks and thence diffused into all the organs. Hepatic sulfo- or glycurocombination then takes pace and renal elimination occurs (Byrne 1997: 35).

It is most unlikely that any essential oils fail to reach the bloodstream entirely when administered on to the skin; the factors that determine in what quantities they do, and how quickly and in what form, are many and complex (Balacs 1992a: 25).

Devlieghere (1996) put up a strong defence for the internal use of essential oils at the first Australasian Aromatherapy Conference. He stated that anxiety about internal use of essential oils is due solely to a lack of knowledge. It is his contention that ingestion of essential oils may be safer than topical application for two reasons:

1. Phototoxicity: several essential oils (e.g. bergamot, lime etc.) contain furanocoumarins. There is a phototoxic effect if essential oils are used topically in combination with UV light. This does not happen when an essential oil is ingested.

2. Allergic reactions: the risk of allergic reactions is much reduced in ingestion compared to dermal administration.

Oral toxicity versus dermal toxicity

Table 9.2 (Devlieghere 1996: 17) is based on the work of Dr Maria Lis-Balchin (1997) and demonstrates that the LD50 (the median lethal dose applicable to 50% of the population) is sometimes safer in internal (oral) administration than when topically applied (dermal).

Table 9.2 Oral toxicity versus dermal toxicity

| LD50 – value in g/kg | ||

|---|---|---|

| Essential oil | Oral LD50 | Dermal LD50 |

| Ocimum basilicum ct. linalool | 1.4 | 0.5 |

| Citrus basilicum ssp bergamia | >10 | >20 |

| Melaleuca leucadendron | 4 | >5 |

| Cinnamomum camphora (white) | >5 | >5 |

| Cinnamomum camphora (yellow) | 4 | >5 |

| Cedrus atlantica | >5 | >5 |

| Juniperus mexicana | >5 | >5 |

| Juniperus virginiana | >5 | >5 |

| Matricaria recutita | >5 | >5 |

| Chamaemelum nobile | >5 | >5 |

| Cinamomum zeylanicum ex foliae | 2.7 | >5 |

| Cinamomum zeylanicum ex cotex | 3.4 | 0.7 |

| Cymbopogon nardus | >5 | 4.7 |

| Salvia sclarea | 5 | >2 |

| Eugenia caryophyllata ex flores | 2.7–3.7 | >5 |

| Eugenia caryophyllata ex foliae | 1.4 | 1.2 |

| Anethum graveloens | 4 | >5 |

| Eucalyptus citriodora | >5 | 2.5 |

| Eucalyptus globules | 4.4 | >5 |

| Foeniculum vulgaris var. dulce | 4.5 | >5 |

| Foeniculum vulgaris var. vulgare | 3.8 | >5 |

| Boswellia carterii | >5 | >5 |

| Zingiber officinale | >5 | >5 |

| Cinnamomum camphora var. hosho | 3.8 | >5 |

| Jasminum grandiflorum | >5 | >5 |

| Juniperus communis ex fructus | 8 | >5 |

| Lavandula angustifolia | >5 | >5 |

| Lavandula x burnatii | >5 | >5 |

| Lavandula latifolia | 4 | 2 |

| Citrus limonum | >5 | >5 |

| Citrus aurantium ssp amara ex flores | 4.5 | >5 |

| Citrus aurantium ssp amara ex pericarpium | >5 | >10 |

| Citrus sinesis | >5 | >5 |

| Rosa damascene | >5 | 2.5 |

| Salvia officinalis | 2.6 | >5 |

| Salvia lavandulaefolia | >5 | >5 |

| Melaluca alternifolia | 1.9 | >5 |

| Cananga odorata forma genuina | >5 | >5 |

| Citrus aurantium ssp amara ex pericarpium | >5 | >10 |

| Citrus sinesis | >5 | >5 |

| Rosa damascene | >5 | 2.5 |

| Salvia officinalis | 2.6 | >5 |

| Salvia lavandulaefolia | >5 | >5 |

| Melaluca alternifolia | 1.9 | >5 |

| Cananga odorata forma genuina | >5 | >5 |

It is impossible to replicate naturally the chemical make-up of essential oils year after year, hence the importance of using the best-quality essential oils from trusted suppliers who have reliable sources.

Schnaubelt (1997 p. 128) responds adequately to questions of safety (particularly with reference to intensive use) when he says:

A reasonable discussion of the safety of essential oils is distorted by the demand for “absolute safety”by consumers and practitioners. These demands are usually entertained by commercial interest looking for a way to sell to a public perceived as underinformed. The real intent of these demands is to ensure safety for the business venture. Alarmist attempts to discontinue completely the use of certain essential oils are a result of this. These warnings are made because there is a fear that accidents with essential oils could be used by government organizations to prohibit trade and thus hurt business. In light of the potential benefits, a modality as safe as aromatherapy should continue to be accessible despite the fact that minor accidents may occur, especially because the probability is much lower than for any other form of self-medication.

Training

Training is essential for any complementary therapy and is vital if the intensive therapeutic use of essential oils is to be developed. It is extremely distressing to see advertisements for training in aromatology or aromatic medicine lasting but one or two days, after which a certificate in competence is issued. A course of such length, however well intentioned, lacks credibility and is a waste of money; a suitable course would be delivered at around Master’s degree level in the UK.

An aspiring practitioner should have experience in using essential oils with a good grounding in theory and practice. Built onto this (or other related experience) should be an in-depth course in the chemistry of essential oils, followed by theoretical and practical knowledge of the specific techniques for intensive application or other appropriate use. Alongside this the specific philosophical theory of diagnostic triptychs, used to understand the development and progression of disease, was first suggested by Pénoël in 1988 and significantly developed by Gascoigne (1994).

It is essential that a period of supervised practice is undertaken, supported by case studies showing an understanding of reflective practice. Competence must be demonstrated by successfully completing an examination in both theory and practice, with regular study and engagement to sustain continuing professional development. This academic and technical rigour is necessary to ensure the wellbeing of clients.

Such a strict training regime is regarded as being elitist and unnecessarily academic, and beyond the intellectual reach of some. Quite so! By comparison, those who wish to practise aromatic medicine in France are expected to qualify as medical doctors before they begin their studies in aromatic medicine. An accredited course gives confidence to both clients and practitioners.

Treating clients

The potential of aromatic medicine is best seen in a case study, showing in one client both acute and chronic symptoms.

A full consultation leads to decisions being made about the priority of treatment needs. It would be accurate to state that, unlike aromatherapy, which anticipates an improvement and maintenance of general wellbeing and homoeostasis, aromatic medicine seeks to see specific and measurable responses to a targeted treatment.

Client assessment

Jim had had to have an amputation just above his ankle 3 years prior to his visit to the Penny Price Academy. The wound contracted MRSA. After the hospital had tried to cure the infection without success, Jim had to have another piece taken from his leg. This happened a further twice and Jim still had MRSA – he had become depressed and tired. His prosthetic leg could not be fitted until the infection had been cured and the skin over the wound had toughened enough not to break down when it came into contact with it.

Intervention

After a holistic assessment confirming both infection and depression, the following essential oils were selected:

• Thymus vulgaris ct. thymol [phenolic thyme] – powerful antiseptic, antidepressant, immunostimulant

• Ravansara aromaticum [ravensara] – antimicrobial, antiseptic, immunostimulant

• Aniba rosaeodora [rosewood] – analgesic, anti-inflammatory, neurotonic

The following were also used in the treatment:

• Hypericum perforatum [hypericum] macerated oil – antidepressant

• Lavandula angustifolia hydrolat [lavender] – anti-inflammatory, cell regenerating

The thyme, ravansara and rosewood oils were blended together in a 10 mL bottle for Jim to apply 4 drops three times a day to his wound, using a pipette to ensure that the oils went as deeply as possible into the infection.

He was given lavender hydrolat to spray on the stump regularly to help improve skin health.

He was also given a month’s supply of capsules using hypericum as the base, with 1 drop each of thyme and rosewood per capsule – Jim took three capsules a day. The hypericum was chosen to help relieve the depression and strengthen the nervous system. The capsules were stopped after 1 month, but Jim continued with the drenches on the wound for 3 months.

Outcome

When Jim returned to the clinic after 3½ months, he walked through the door using his newly fitted prosthetic leg. The MRSA was no longer present, the wound had completely healed and the skin on the stump was strong and healthy. He was bright and cheerful and ‘over the moon’ that he had his independence back, no pain and no depression. Jim’s wife was so impressed by the change in Jim that she has begun a training course in aromatology. Jim is using his prosthetic leg and is now well enough holistically to engage with life again – he says ‘MRSA is not just about wounds – energy, appetite and will have all returned and everyone says how well I look’.

Conclusion

Aromatic medicine is a natural treatment using organic, unadulterated, whole plant volatile oils, hydrolats and fixed carrier oils, creating the most appropriate chemical synergy via the most effective interface as a targeted response to a presenting symptom or symptoms. It is often regarded as a development of aromatherapy, but should properly be understood as part of complete aromatherapy. As such, it is an exciting and safe therapy, using the same tools as in current aromatherapy practice but applied in distinct ways for specific outcomes.

Balacs T. Dermal crossing. Int. J. Aromather.. 1992;4(2):23-26.

Balacs T. Hormones and health. Int. J. Aromather.. 1993;5(1):18-20.

Balacs T. Essential oils in the body: their absorption, distribution, metabolism and excretion. Proceedings of the AROMA 93 Conference. 1993.

Byrne K. Ingestion of essential oils: food for thought. Simply Essential. 1997;26:34-36.

Davis P. Aromatherapy: an A-Z. London: Vermilion; 2000.

Devleighere G. Oral use of essential oils. Proceedings of the Australasian Aromatherapy Conference. 1996.

Franchomme P., Pénoël D. L’Aromathérapie Exactement Roger Jollois Editeur. 1990.

Freeman L.W., Lawlis G.L. Complementary and Alternative Medicine: a researched based approach. St Louis: Mosby; 2001.

Gascoigne S. The Manual of Conventional Medicine for Alternative Practitioners. Dorking: Jigme Press; 1994.

Miller A.L. St. John’s Wort (Hypericum perforatum): Clinical Effects on Depression and Other Conditions. Altern. Med. Rev.. 1998;3(1):18-26.

Price L., Price S. Aromatherapy for Health Professionals, third ed. Edinburgh: Churchill-Livingstone; 2007.

Scheuplein R.J., Blank I.H. Permeability of the skin. Psychol. Rev.. 1971;51(4):702-747.

Schnaubelt K. Friendly molecules: aspects of essential oil constituents and their pharmacology. Int. J. Aromather.. 1989;2(2):20-22. and 2 (3), 16–17

Schnaubelt K. Advanced Aromatherapy. Vermont: Healing Arts Press; 1996.

Schnaubelt K. Medical Aromatherapy. Berkeley: Frog; 1997.

Stephen R. Essential oils and viral illness. Aromatopia. 2010;19(1):9-13.

Valette G., Sobrin E. Absorption percutanée de diverses huiles animals ou végétales. Pharmaceutia acta Helvetiae. 1962;38:710-716.

Valnet C. Comptes Rendus. Société de Biologie. 1945. (13th October)

Webster R.C., Maibach H.I. Cutaneous pharmacokinetics: 10 steps to percutaneous absorption. Drug Metab. Rev.. 1983;14(2):169-205.

Weyers W., Brodbeck R. Skin absorption of essential oils. Pharm. Unserer Zeit. 1989;18(3):82-86.

Williams D.G. The chemistry of essential oils. Weymouth: Mycelle Press; 1996.

Zatz J.L. Scratching the surface: rationale and approach to skin permeation. In: Zatz J.L., editor. Skin Permeation: fundamentals and applications. Wheaton: Allured, 1993.