Introduction to Anesthesia

When you have completed this chapter, you will be able to:

• Define anesthesia, and differentiate topical, local, regional, general, and surgical anesthesia.

• Differentiate sedation, tranquilization, hypnosis, and narcosis.

• Explain the concept of balanced anesthesia and the advantages of this approach.

• List common indications for anesthesia.

• Describe fundamental challenges and risks associated with anesthesia.

• List the qualities and abilities of a successful veterinary anesthetist.

HISTORY AND TERMINOLOGY OF ANESTHESIA

On October 16, 1846, at Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston dentist William T. G. Morton gave the first successful demonstration of the pain-relieving properties of diethyl ether in the presence of a group of physicians and medical students. On receiving the ether, the patient, who was undergoing a tumor removal, entered a state of insensibility during which the surgical pain was alleviated. During the next several months, additional experiments conducted by Morton and others confirmed the value of ether as an effective pain-relieving agent in surgery patients.

Although ether had been used experimentally as early as 1842, Dr. Morton’s demonstration is particularly significant because it attracted the attention of the prominent physician Oliver Wendell Holmes Sr., who, in a letter to Dr. Morton dated November 21, 1846, suggested that the state of insensibility to pain produced by this agent be called anesthesia. The name was adopted by the medical community, and over the next few years the practice of anesthesia spread widely throughout North America and Europe. The veterinary community, however, did not embrace the use of anesthetics as rapidly. Although reports began to appear in the veterinary literature regarding the use of inhalation anesthetics such as ether and chloroform within the following decade, inhalation anesthesia was not an accepted practice until early in the twentieth century. Only after the development of injectable barbiturates in the 1930s did the use of anesthetics in veterinary patients become commonplace.

The term anesthesia (derived from the Greek word anaisthesia which means “without feeling” or “insensibility”) may be defined as “a loss of sensation.” By providing a loss of sensation, or more specifically the loss of sensitivity to pain, the development and use of anesthetics during the mid-nineteenth century solved one of the primary problems associated with surgery. Since then, the practice of anesthesia has gradually evolved from an experimental technique to a highly sophisticated science. Now, over 160 years after its introduction, anesthesia is used daily in most veterinary practices to provide sedation, tranquilization, immobility, muscle relaxation, unconsciousness, and pain control for a diverse range of indications including surgery, dentistry, grooming, diagnostic imaging, wound care, and capture and transport of wild animals, just to name a few. So although the literal definition of the term anesthesia accurately describes one of its fundamental effects, when viewed from the perspective of current practice the word falls far short of capturing the many facets of this complex discipline.

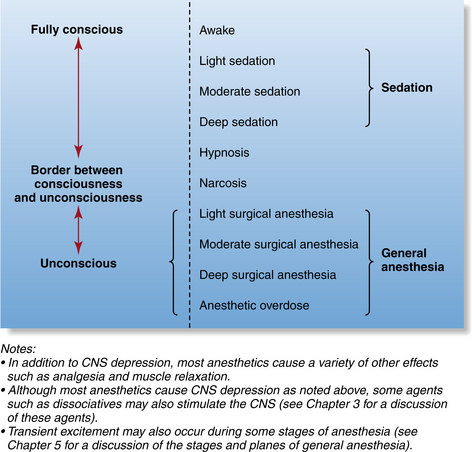

Most people associate the word anesthesia with general anesthesia, which is only one extreme in a continuum of levels of central nervous system (CNS) depression that can be induced by administration of anesthetic agents (Figure 1-1). General anesthesia may be defined as a reversible state of unconsciousness, immobility, muscle relaxation, and loss of sensation throughout the entire body produced by administration of one or more anesthetic agents. While under general anesthesia, a patient cannot be aroused even with painful stimulation. For this reason, general anesthesia is commonly used to prepare patients for surgery or other acutely painful procedures. Surgical anesthesia is a specific stage of general anesthesia in which there is a sufficient degree of analgesia (a loss of sensitivity to pain) and muscle relaxation to allow surgery to be performed without patient pain or movement.

FIGURE 1-1 The continuum of levels of central nervous system depression induced by anesthetic agents.

Other states within the continuum of CNS depression include sedation and tranquilization. Sedation refers to drug-induced CNS depression and drowsiness that vary in intensity from light to deep. A sedated patient generally is minimally aware or unaware of its surroundings but can be aroused by noxious stimulation. Sedation is often used to prepare patients for diagnostic imaging, grooming, wound treatment, and other minor procedures. Tranquilization is a drug-induced state of calm in which the patient is reluctant to move and is aware of but unconcerned about its surroundings. Although the terms tranquilization and sedation are not exactly the same in meaning, they are often used interchangeably.

The terms hypnosis and narcosis are also used to describe anesthetic-induced states. Hypnosis is a drug-induced sleeplike state that impairs the ability of the patient to respond appropriately to stimuli. This meaning of this term is somewhat imprecise, as it is used to describe various degrees of CNS depression. In this text, hypnosis will be used to mean a sleeplike state from which the patient can be aroused with sufficient stimulation. The term narcosis refers to a drug-induced sleep from which the patient is not easily aroused and that is most often associated with the administration of narcotics.

The effect of anesthetic agents may be selectively directed to affect specific areas or regions of the body. Smaller areas can be targeted by use of local or topical anesthesia. Local anesthesia refers to loss of sensation in a small area of the body produced by administration of a local anesthetic agent in proximity to the area of interest. Infiltration of local anesthetic into the tissues surrounding a small tumor to facilitate removal is an example of local anesthesia. Topical anesthesia is the loss of sensation of a localized area produced by administration of a local anesthetic directly to a body surface or to a surgical or traumatic wound. Use of ophthalmic local anesthetic drops in the eye before an ophthalmic examination or application of local anesthetic to an open declaw incision for the purpose of pain control are examples of topical anesthesia.

Larger areas can be targeted by use of regional anesthesia, which refers to a loss of sensation in a limited area of the body produced by administration of a local anesthetic or other agent in proximity to sensory nerves. Regional anesthesia can be produced with a variety of techniques including nerve blocks and epidural anesthesia. For example, a brachial plexus block can be used to anesthetize the forelimb distal to and including the elbow; a maxillary nerve block can be used to anesthetize the upper dental arcade; and epidural anesthesia can be used to provide pain control of the rear quarters and pelvic region.

When anesthetics are administered, it is common practice to administer multiple drugs concurrently in smaller quantities than would be required if each were given alone. This technique, termed balanced anesthesia, maximizes the benefits of each drug, minimizes adverse effects, and gives the anesthetist the ability to produce anesthesia with the degree of CNS depression, muscle relaxation, analgesia, and immobilization appropriate for the patient and the procedure. Premedication with acepromazine, anesthetic induction with a combination of ketamine and diazepam, maintenance with isoflurane, and administration of a morphine and lidocaine infusion for analgesia is one example of balanced anesthesia.

THE VETERINARY TECHNICIAN’S ROLE IN THE PRACTICE OF ANESTHESIA

Preparation, operation and maintenance of anesthetic equipment, administration of anesthetic agents, endotracheal intubation, and patient monitoring are considered part of the credentialed veterinary technician’s scope of practice and are a required part of any accredited veterinary technology program’s curriculum. Competency in each of these areas of responsibility requires an advanced knowledge and skill level that can be achieved only with a substantial commitment of time and effort on the part of the student. Before embarking on a study of anesthesia, the student must be aware of the following fundamental challenges and inherent risks she will face when acting as anesthetist.

• Most anesthetic agents have a very narrow therapeutic index, so the consequences of a calculation or administration error may be serious. Therefore care and attention to detail are critical when dosages are calculated and rates of administration are adjusted.

• Most anesthetic agents cause significant changes in cardiovascular and pulmonary function (e.g., decreased cardiac output, respiratory rate, tidal volume, and blood pressure), which can be dangerous or lethal if not carefully assessed and managed. These changes often occur quickly and without much warning. Vital signs and indicators of anesthetic depth must therefore be closely monitored.

• The anesthetist must accurately interpret a wide spectrum of visual, tactile, and auditory information from the patient, anesthetic equipment, and monitoring devices. To do this successfully, she must be able to rapidly assess multiple pieces of information and distinguish those that require action from those that do not.

• The anesthetist must have a comprehensive understanding of the significance of physical parameters and machine-generated data. The anesthetist must also be able to use her knowledge to make rapid and decisive judgments regarding patient management and to carry out corrective actions quickly and effectively.

• The potential for patient harm during administration of anesthetics is relatively high when compared with many other procedures. When serious anesthetic accidents occur, they are often devastating not only for the patient but also for the client and the anesthetist. In addition, after an accident, clients may choose to pursue legal action or file a complaint with the state veterinary medical board if they feel negligence was involved. These factors underscore the importance of maintaining a high standard to maximize the likelihood of a favorable outcome. This standard includes not only sound practices but also maintenance of detailed and accurate medical records, which are the cornerstone of a solid legal defense should a complaint arise. (See Chapter 5 for more information about anesthetic records.)

In view of each of these risks and challenges, the anesthetist must approach any anesthetic procedure with a genuine willingness to take personal responsibility for the well-being of the patient. Acceptance of this responsibility by the anesthetist is dependent on development of competance and confidence. Ultimately, competance and confidence are acquired only with much study, practice, persistence, an attitude of caring, and a dedication to excellence. Only then can the accomplished anesthetist use her skills and knowledge to protect and improve the life of each and every patient under her care in a way that is infinitely gratifying and singular to this complex and challenging discipline.

KEY POINTS

1. General anesthesia is a reversible state of unconsciousness, immobility, muscle relaxation, and generalized loss of sensation, produced by administration of anesthetic agents. It is only one extreme in a continuum of levels of CNS depression produced by anesthetic agents, which also include sedation, hypnosis, and narcosis.

2. Many techniques including sedation, tranquilization, and topical, local, regional, and general anesthesia are used to produce specific effects appropriate to each patient.

3. Balanced anesthesia (the administration of multiple drugs in the same patient during one anesthetic event) is commonplace in the practice of anesthesia and produces many benefits not possible with administration of a single anesthetic.

4. Anesthesia involves a number of unique risks and dangers, of which the anesthetist must be conscious and aware.

5. The successful practice of anesthesia requires a high level of knowledge, competency, commitment, and acceptance of responsibility on the part of the anesthetist.

REVIEW QUESTIONS

1. A drug-induced state of calm in which the patient is reluctant to move and is aware of but unconcerned about its surroundings.

2. The term regional anesthesia refers to:

a. Loss of sensation in a limited area of the body produced by administration of a local anesthetic or other agent in proximity to sensory nerves

b. Loss of sensation in a small area of the body produced by administration of a local anesthetic agent in proximity to the area of interest

c. Loss of sensation of a localized area produced by administration of a local anesthetic directly to a body surface or to a surgical or traumatic wound

d. A drug-induced sleeplike state that impairs the ability of the patient to respond appropriately to stimuli

3. A sleeplike state from which the patient can be aroused with sufficient stimulation.

4. The term balanced anesthesia refers to:

a. The administration of two or more agents in equal volume

b. Administration of multiple drugs concurrently in smaller quantities than would be required if each were given alone

c. General anesthesia in which the patient’s physiologic status remains stable

d. The administration of a local and general anesthetic concurrently

For the following questions, more than one answer may be correct.