30 Schizophrenia

The concept of schizophrenia can be difficult to understand. People who do not suffer from schizophrenia can have little idea of what the experience of hallucinations and delusions is like. The presentation of schizophrenia can be extremely varied, with a great range of possible symptoms. There are also many misconceptions about the condition of schizophrenia that have led to prejudice against sufferers of the illness. People with schizophrenia are commonly thought to have low intelligence and to be dangerous. In fact, only a minority shows violent behaviour, with social withdrawal being a more common picture. Up to 10% of people with schizophrenia commit suicide.

Classification

Since the late nineteenth century there have been frequent attempts to define the illness we now call schizophrenia. Kraepelin, in the late 1890s, coined the term ‘dementia praecox’ (early madness) to describe an illness where there was a deterioration of the personality at a young age. Kraepelin also coined the terms ‘catatonic’ (where motor symptoms are prevalent and changes in activity vary), ‘hebephrenic’ (silly, childish behaviour, affective symptoms and thought disorder prominence) and ‘paranoid’ (clinical picture dominated by paranoid delusions). A few years later Bleuler, a Swiss psychiatrist introduced the term ‘schizophrenia’, derived from the Greek words skhizo (to split) and phren (mind), meaning the split between the emotions and the intellect.

Two systems for the classification of schizophrenia are widely used: the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th edition (DSM IV; American Psychiatric Association, 1994) and the International Classification of Diseases, 10th edition (ICD 10; World Health Organization, 1992).

Symptoms and diagnosis

Acute psychotic illness

To establish a definite diagnosis of schizophrenia it is important to follow the diagnostic criteria in either DSM IV or ICD 10, but symptoms which commonly occur in the acute phase of a psychotic illness include the following:

These symptoms are commonly called positive symptoms.

Factors affecting diagnosis and prognosis

There is a reluctance to classify people as suffering schizophrenia on the basis of one acute psychotic illness, but there are a number of features which aid prediction of whether an acute illness will become chronic. These features include:

Treatment

There is a wide range of antipsychotic drugs available for the treatment of a psychotic illness. Although most antipsychotic drugs are equally effective in the treatment of psychotic symptoms, some individuals respond better to one drug than another.

There is controversy over how long people should remain on an antipsychotic drug following their first acute illness. Some would argue that, if the prognosis is poor, long-term therapy should be advocated. Others would want to see a second illness before advocating long-term therapy.

Chronic schizophrenia

Between 60% and 80% of patients who suffer from an acute psychotic illness will suffer further illness and become chronically affected. For these patients the diagnosis of schizophrenia can be applied.

As schizophrenia progresses, there may be periods of relapse with acute symptoms but the underlying trend is towards symptoms of lack of drive, social withdrawal and emotional apathy. Such symptoms are sometimes called negative symptoms and respond poorly to most antipsychotic drugs.

Causes of schizophrenia

Although the cause of schizophrenia remains unknown, there are many theories and models.

Vulnerability model

The vulnerability model postulates that the persistent characteristic of schizophrenia is not the schizophrenic episode itself but the vulnerability to the development of such episodes of the disorder. The episodes of the illness are time limited but the vulnerability remains, awaiting the trigger of some stress. Such vulnerability can depend on premorbid personality, the individual’s social network or the environment. Manipulation and avoidance of stress can abort a potential schizophrenic episode.

Developmental model

The developmental model postulates that there are critical periods in the development of neuronal cells which, if adversely affected, may result in schizophrenia. Two such critical periods are postulated to occur when migrant neural cells do not reach their goal in fetal development and when supernumerary neural cells slough off at adolescence. This model is supported by neuroimaging studies which show structural brain abnormalities in patients with schizophrenia.

Ecological model

The ecological model postulates that external factors involving social, cultural and physical forces in the environment, such as population density, individual space, socio-economic status and racial status, influence the development of the disorder. The evidence in support of such a model remains weak.

Genetic model

There is undoubtably a genetic component to schizophrenia, with a higher incidence in the siblings of schizophrenics. However, even in monozygotic twins there are many cases where only one sibling has developed schizophrenia.

Transmitter abnormality model

The suggestion that schizophrenia is caused primarily by an abnormality of dopamine receptors and, in particular, D2 receptors, has largely emerged from research into the effect of antipsychotic drugs. Such a theory is increasingly being questioned.

Other factors

Numerous other factors have been implicated in the development and cause of schizophrenia. These include migration, socio-economic factors, perinatal insult, infections, season of birth, viruses, toxins and family environment.

In reality, all of these factors may influence both the development and progression of schizophrenia. Social, familial and biological factors may lead to premorbid vulnerability and subsequently influence both the acute psychosis and the progression to chronic states. What is then likely is that the illness will feed back to influence social, familial and biological factors, thus leading to future vulnerability.

Drug treatment

Mode of action of antipsychotic drugs

Although the cause of schizophrenia is the subject of controversy, an understanding of the mode of action of antipsychotic drugs has led to the dopamine theory of schizophrenia. This theory postulates that the symptoms experienced in schizophrenia are caused by an alteration to the level of dopamine activity in the brain. It is based on knowledge that dopamine receptor antagonists are often effective antipsychotics while drugs which increase dopamine activity, such as amfetamine, can either induce psychosis or exacerbate a schizophrenic illness.

At least six dopamine receptors exist in the brain, with much activity being focused on the D2 receptor as being responsible for antipsychotic drug action. However, drugs such as pimozide, that claim to have a more specific effect on D2 receptors, do not appear superior in antipsychotic effect when compared to other agents.

Research into the mode of action of clozapine has caused a change of attention to the mesolimbic system in the brain and to different receptors. Clozapine does not chronically alter striatal D2 receptors but does appear to affect striatal D1 receptors. It also appears to have more effect on the limbic system and on serotonin (5HT2) receptors, which may explain its reduced risk of extrapyramidal symptoms. The term ‘atypical’ is used to categorise those antipsychotic drugs that, like clozapine, rarely produce extrapyramidal side effects (EPSEs).

Although the reason for the superiority of clozapine in schizophrenia treatment remains an enigma, a variety of theories have led to the development of a new family of antipsychotic drugs. Some mimic the impact of clozapine on a wide range of dopamine and serotonin receptors, for example, olanzapine, others mimic the impact on particular receptors, for example, 5HT2/D2 receptor antagonists such as risperidone, others focus on limited occupancy of D2 receptors, for example, quetiapine, while others focus on alternative theories such as partial agonism (aripiprazole).

Rationale for use of drugs

Although a variety of social and psychological therapies are helpful in the treatment of schizophrenia, drugs form the essential cornerstone. The aim of all therapies is to minimise the level of handicap and achieve the best level of mental functioning. Drugs do not cure schizophrenia and are only partially effective at eradicating some symptoms such as delusions and negative symptoms. At the same time, benefits have to be balanced against side effects and whether the need to suppress particular symptoms is important. For example, if the person has a delusion that he or she is responsible for famine in Africa, but this does not in any way influence that person’s behaviour or mood, a common view would be that there would be little point in increasing antipsychotic drug therapy. However, others would argue that this ‘untreated’ delusion would make the person stand out or be subject to social stigma and the delusion should be more aggressively treated. If, on the other hand, this delusion led to great distress, or violent or dangerous behaviour, then an increase in antipsychotic drugs would usually be indicated.

It is now accepted that antipsychotic drugs can control or modify symptoms such as hallucinations and delusions that are evident in the acute episode of illness. Except for clozapine and the other atypicals, there is little evidence for antipsychotic drugs being of value in the treatment of the negative symptoms, although the matter remains controversial (Chakos et al., 2001). Antipsychotic drugs increase the length of time between breakdowns and shorten the length of the acute episode in most patients.

Drug selection and dose

Over the years there have been many changes to the range of antipsychotic drugs available. Despite the availability of newer agents many of the issues relevant to drug selection and dose have remained similar for the last 50 years and include:

Individual response

Drug selection should not be based on chemical group alone, since individual response to a particular drug or dose may be more important.

Side effects

For older, typical antipsychotic drugs, side effects such as hypotension, extrapyramidal symptoms and anticholinergic effects are key factors in the choice of drug. In contrast, with the newer atypical drugs, side effects such as diabetes, sexual dysfunction and weight gain affect adherence in many patients. Sedation remains a factor for all antipsychotic drugs.

The key side effects of concern are those categorised as EPSEs. Those that caused these side effects were called typical antipsychotic drugs and those that did not were called atypical. This classification system, however, has always remained subject to criticism as some atypicals will cause EPSEs when used at higher doses and the side effects of the different atypicals can vary considerably. EPSEs include:

Akathisia or motor restlessness. This causes patients to pace up and down, constantly shift their leg position or tap their feet.

Dystonia is the result of sustained muscle contraction. It can present as grimacing and facial distortion, neck twisting and laboured breathing. Occasionally the patient may have an oculogyric crisis in which, after a few moments of fixed staring, the eyeballs move upwards and then sideways, remaining in that position. In addition to these eye movements, the mouth is usually wide open, the tongue protruding and the head tilting backwards.

Parkinson-like side effects usually present as tremor, rigidity and poverty of facial expression. Drooling and excessive salivation are also common. A shuffling gait may be seen and the patient may show signs of fatigue when performing repetitive motor activities.

Another movement disorder more commonly associated with typical antipsychotics is tardive dyskinesia. Tardive dyskinesia normally affects the tongue, facial and neck muscles but can also affect the extremities. Individuals with tardive dyskinesia often have abnormalities of posture and movement of the fingers in addition to the oral-lingual-masticatory movements.

Epidemiological studies support the association between the prescribing of typical antipsychotic drugs and the development of tardive dyskinesia. Other factors which also appear to be associated include the duration of exposure to antipsychotic drugs, the co-prescribing of anticholinergic drugs, the co-prescribing of lithium, advanced age, prior experience of acute extrapyramidal symptoms and brain damage. Many other factors have been postulated to be associated with tardive dyskinesia such as depot formulations of antipsychotic drugs, dosage of antipsychotic drug and antipsychotic drugs with high anticholinergic activity, but such associations remain unproven.

Although the mechanism by which tardive dyskinesia arises is unclear, the leading hypothesis is that after prolonged blockade of dopamine receptors, there is a paradoxical increase in the functional activity of dopamine in the basal ganglia occurs. This increased functional state is thought to come about through a phenomenon of disuse supersensitivity of dopamine receptors. The primary clinical evidence to support this theory arises because tardive dyskinesia is late in onset following prolonged exposure to antipsychotic drugs and has a tendency to worsen upon abrupt discontinuation of the antipsychotic drug.

Attempts to treat tardive dyskinesia have been many and varied. Treatments include use of dopamine-depleting agents such as reserpine and tetrabenazine, dopamine-blocking agents such as antipsychotic drugs, interference with catecholamine synthesis by drugs such as methyldopa, cholinergic agents such as choline and lecithin, use of GABA mimetic agents such as sodium valproate and baclofen, and the provision of drug holidays. Rarely are these strategies successful. Most successful strategies currently involve a gradual withdrawal of the typical antipsychotic drug and replacement with an atypical antipsychotic drug.

Concerns about the EPSEs and toxicity of typical antipsychotic drugs led to calls over the past 10 years for the ‘atypicals’ to be prescribed more widely. This approach was supported in national guidance which advocated that atypical antipsychotic drugs should be used for the treatment of a first illness. However, increasing concern about the side effects of the atypical antipsychotic drugs, which includes weight gain, diabetes and sexual dysfunction, has led many clinicians to question the benefits of the newer and more expensive atypical antipsychotics. In more recent guidance (National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence, 2009), it has been advocated that:

Information on the advantages and disadvantages of the various antipsychotic drugs can be found in Table 30.1.

Table 30.1 Neuroleptics/antipsychotics and their commonly associated attributes and problems

| Drug group | Drug | Comment |

|---|---|---|

| Butyrophenones | Haloperidol | Regarded as the gold standard reference antipsychotic |

| Extrapyramidal side effects of parkinsonian rigidity, dystonia, akathisia | ||

| Tardive dyskinesia with long-term use | ||

| Drug most associated with neuroleptic malignant syndrome | ||

| Sedation common | ||

| Hormonal effects common | ||

| Wide range of formulations including long-acting injection | ||

| Benperidol | As haloperidol | |

| Claimed to reduce sexual drive, although little evidence to support the claim | ||

| Phenothiazines | ||

| Piperidine | Pericyazine | Marked anticholinergic side effects of dry mouth, blurred vision and constipation |

| Postural hypotension and falls in the elderly | ||

| Lower incidence of extrapyramidal side effects | ||

| Pipotiazine | As pericyazine but only available as depot formulation | |

| Aliphatic | Chlorpromazine | As haloperidol but in addition postural hypotension, low body temperature, rashes and photosensitivity |

| Increased sedative effects | ||

| Promazine | As chlorpromazine but low potency | |

| Considered by some to have weak antipsychotic effect | ||

| Levomepromazine | Very sedative and postural hypotension common | |

| (methotrimeprazine) | Mostly used in terminal illness | |

| Piperazine | Trifluoperazine | As chlorpromazine but greater incidence of extrapyramidal side effects and lower incidence of anticholinergic effects |

| Tardive dyskinesia with long-term use | ||

| Some antiemetic properties | ||

| Fluphenazine | As trifluoperazine but also available as depot formulation | |

| Perphenazine | As trifluoperazine | |

| Thioxanthines | Flupentixol | Similar to fluphenazine but also available as depot formulation |

| Zuclopenthixol | Similar to chlorpromazine but also available as depot formulation | |

| Diphenylbutylpiperidines | Pimozide | As haloperidol but concerns about cardiac effects at high dose limits use |

| Benzamides | Sulpiride | Lower incidence of extrapyramidal effects |

| Few anticholinergic effects | ||

| Useful adjunct to clozapine in refractory illness | ||

| Amisulpride | As sulpiride | |

| Dibenoxazepine tricyclics | Clozapine | Drug of choice for treatment-resistant schizophrenia |

| Low incidence of extrapyramidal side effects or tardive dyskinesia | ||

| Neutropenia in 1–2% of cases | ||

| Enhanced efficacy against both positive and negative symptoms | ||

| Sedation, dribbling, drooling, weight gain and diabetes | ||

| Thienobenzodiazepines | Olanzapine | Sedation, weight gain and diabetes |

| Low incidence of extrapyramidal side effects and low impact on prolactin | ||

| Quetiapine | Low incidence of extrapyramidal side effects and low impact on prolactin | |

| Zotepine | Similar to olanzapine but higher rate of prolactin elevation and higher rate of drug-induced seizures | |

| Serotonin–dopamine antagonists | Risperidone | Extrapyramidal side effects at higher doses. High rate of prolactin elevation |

| Paliperidone | As risperidone | |

| Ziprasidone | As risperidone | |

| Sertindole | Available on named patient basis only due to risk of sudden cardiac events | |

| Partial dopamine agonist | Aripiprazole | Low level of side effects but light-headedness and blurred vision common |

A significant factor that has influenced prescribing practice in schizophrenia in recent years has been an improved understanding of the role of clozapine in treatment-resistant schizophrenia.

Clozapine and refractory illness

Clozapine was developed as an antipsychotic drug during the 1960s. Unfortunately, use is associated with a 1–2% incidence of neutropenia and this initially resulted in the withdrawal of the drug from clinical practice. However, it was noted even at an early stage in the drug’s history that it was free of the extrapyramidal side frequently seen with the other antipsychotic drugs. In the 1980s, clozapine was demonstrated to have a greater efficacy than other antipsychotics (Kane et al., 1988; Lieberman et al., 1994) and was subsequently reintroduced into clinical practice but with routine monitoring of blood mandatory.

Clozapine is now established as the drug of choice in treatment-resistant schizophrenia but it is not without problems (Tuunainen et al., 2000). In addition to neutropenia, it is associated with a greater risk of seizures, particularly if doses are above 600 mg daily. Some guidelines recommend the co-prescribing of sodium valproate to reduce this risk. In addition, use is associated with excessive drooling, hypotension and sedation during the early stages of treatment, requiring slow dose increases initially.

A regimen of gradual dose increases starting at 12.5 mg twice daily aiming to reach 300 mg in 2–3 weeks is normally recommended. However, this rate of dose increase is frequently too rapid, with tachycardia being a particular problem. In such cases, it is usual to slow down the rate of dose increase to a half or a quarter of that recommended. Although tachycardia is a common problem with clozapine initiation, if use is associated with fever, chest pain or hypotension this may indicate a high risk of myocarditis and the drug should be stopped (Committee on Safety of Medicines, 2002).

Polypharmacy

Polypharmacy remains a matter of concern in the management of individuals with schizophrenia. It usually arises because:

Neuroleptic equivalence

Although antipsychotic drugs vary in potency, studies on relative dopamine receptor binding have led to the concept of chlorpromazine equivalents as a useful method of transferring dosage from one product to another. Concern has been expressed about the variation between sources for such values, in particular about the quoted chlorpromazine equivalents of the butyrophenones and the conversion of depot doses to oral doses (Table 30.2). Likewise, there is no agreement on the equivalent doses of the atypicals.

Table 30.2 Equivalence of typical antipsychotic drugs to 100 mg chlorpromazine (from Foster, 1989)

| Drug | Usual dose (mg) equivalent of to 100 mg chlorpromazine | Variations in quoted dosage (mg) equivalent to 100 mg of chlorpromazine |

|---|---|---|

| Oral antipsychotics | ||

| Promazine | 200 | 100–250 |

| Thioridazine | 100 | 50–120 |

| Trifluoperazine | 5 | 3.5–7.5 |

| Haloperidol | 2 | 1.5–5 |

| Sulpiride | 200 | – |

| Depot antipsychotics administered every 2 weeks (all administered as the decanoate) | ||

| Zuclopenthixol | 200 | 80–200 |

| Flupentixol | 40 | 16–40 |

| Fluphenazine | 25 | 10–25 |

| Haloperidol | 20 | – |

For research purposes the concept of proportion of the maximum dose stated in the British National Formulary (BNF) has been developed as a standardised method for calculating average doses used in practice. However, this may not be a useful way of determining a dose when transferring a patient from one antipsychotic to another.

Augmentation strategies and polytherapy

Schizophrenia is a complex illness with a very varied presentation. In addition to the core symptoms, elements of other mental illnesses such as mania, depression and anxiety may predominate. Controversy remains about whether these associated symptoms should be treated separately or as a part of schizophrenia. In addition, there is debate about whether these presentations represent an alternative diagnosis, for example, schizoaffective disorder when the mood disorder is a primary component of the presentation. The current fashion is for these components of the illness to be treated separately, with much resulting polytherapy with SSRI antidepressants and antiepileptic drugs for mood control.

In addition to the above, complex prescriptions can arise when treatment with clozapine is perceived to be inadequate or doses are limited due to side effects. The theory behind the addition of a further drug can be either that the plasma concentration of the clozapine will be enhanced by the addition of another drug, or the second drug will enhance a particular receptor blockade which may be considered necessary in a specific patient (Cipriani et al., 2009; Paton et al., 2007). The augmentation strategy with the best evidence to support its use is the addition of sulpiride or amisulpride to clozapine. Other strategies include the addition of risperidone, lamotrigine or Ω3 fatty acids. However, many of the trials that support these augmentation strategies are small scale and a meta-analysis concluded that no single strategy was superior to another (Paton et al., 2007).

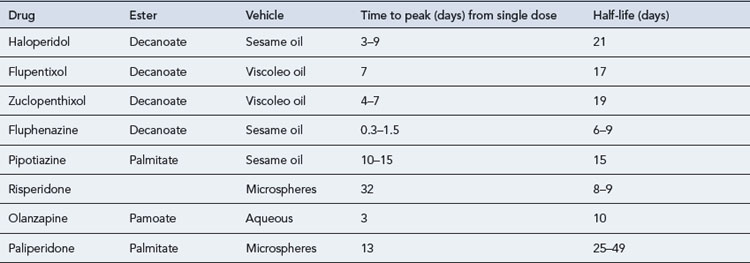

Long-acting formulations of antipsychotic drugs

Most long-acting (depot) formulations, including the long-acting olanzapine formulation, are synthesised by esterification of the hydroxyl group of the antipsychotic drug to a long chain fatty acid such as decanoic acid. The esters which are more lipophilic and soluble are dissolved in an oily vehicle such as sesame oil or a vegetable oil (viscoleo). Once the drug is injected into muscle it is slowly released from the oil vehicle. Active drug becomes available following hydrolysis for distribution to the site of the action. A long-acting injection of olanzapine has been marketed which contains a salt of olanzapine and pamoic acid suspended in an aqueous vehicle. This also is designed for intramuscular injection every 2–4 weeks.

Although the ideal long-acting antipsychotic formulation should release the drug at a constant rate so that plasma level fluctuations are kept to a minimum, all the available products produce significant variations (Table 30.3). This can result in increased side effects at the time of peak plasma concentrations, usually after 5–7 days, for oil-based depots and increased patient irritability towards the end of the period, as plasma concentrations decline. For many patients though, oil-based long-acting formulations result in a very slow decline in drug availability after a period of chronic administration (Altamura et al., 2003). When transferring a patient from depot formulations to oral administration, it may be many months before the effect of the depot finally wears off.

Long-acting risperidone injection involves a microsphere formulation. The microspheres delay the release of risperidone for 3–4 weeks. Once release has commenced, the risperidone reaches a maximum concentration 4–5 weeks after the injection with a decline over the subsequent 2–3 weeks. This more rapid decline has an advantage that by 2 months after the last injection, little of the risperidone will remain. The delay in onset is often a reason for relapse as it is necessary to maintain oral supplementation for at least 6 weeks and this may be overlooked.

In addition to the principles of drug choice and dosage selection that apply to oral drugs, with depot therapy there is also a need to consider the future habitation of the patient. If the patient is to live an independent lifestyle, depot formulations are indicated, but if the person is to remain in staffed accommodation and receive other medicines routinely administered by a nurse, the use of depot formulations may not be logical.

Advantages and disadvantages of long-acting formulations

Non-adherence with oral medicines is a major problem in patients with any long-term illness and the administration of depot formulations guarantees drug delivery. It has been argued that, although depot injections are expensive, they have economic advantages because they reduce hospital admissions, improve drug bioavailability by avoiding the deactivating processes which occur in the gut and liver, and result in more consistent plasma levels of drug.

Depot formulations have the disadvantage of reduced flexibility of dosage, the painful nature of administration and, for the older depots, a high incidence of EPSEs. In addition, risperidone long-acting injection has the disadvantage of considerable delay in onset, whilst the olanzapine depot is associated with a post-injection syndrome consistent with olanzapine overdose. Although this side effect is relatively rare there is a requirement for patients to be observed for 3 hours following injection thereby limiting its acceptability.

Anticholinergic drugs

Anticholinergic drugs are prescribed to counter the EPSEs of typical antipsychotics, and at one time were routinely prescribed. It is generally accepted that, with the possible exception of the first few weeks of treatment with antipsychotic drugs known to have a high incidence of EPSEs, anticholinergic drugs should only be prescribed when a need has been shown. A number of studies have looked at the discontinuation of anticholinergic agents and reported re-emergence of the symptoms. Up to 60% of patients may be affected by re-emergence of symptoms and between 25% and 30% of patients will have a continuing need for anticholinergic drugs. The anticholinergic drugs are not without problems, having their own range of side effects that include dry mouth, constipation and blurred vision. Trihexyphenidyl in particular, is renowned for its euphoric effects and withdrawal problems can include cholinergic rebound. One of the benefits of the atypical antipsychotic drugs is the reduced need for co-prescription of anticholinergic drugs. However, EPSEs can still occur with atypical antipsychotic drugs, particularly at high dose.

Interactions and antipsychotic drugs

There are claimed to be many interactions involving antipsychotic drugs but few appear to be clinically significant. Propranolol increases the plasma concentration of chlorpromazine, and carbamazepine accelerates the metabolism of haloperidol, risperidone and olanzapine. When tricyclic antidepressants are administered with phenothiazines, increased antimuscarinic effects such as dry mouth and blurred vision can occur and most antipsychotic drugs increase the sedative effect of alcohol. The SSRI antidepressants fluvoxamine, fluoxetine and paroxetine interact with clozapine, resulting in increases in clozapine plasma concentration.

Therapeutic drug monitoring

Therapeutic drug monitoring is only of value if there is a reliable laboratory assay and a correlation exists between the concentration of the drug in any particular body compartment, usually blood/plasma, and its clinical effectiveness. Unfortunately, this is not the case for most antipsychotic drugs and the measurement of drug concentrations is not a part of routine clinical practice. In recent years, however, it has become common to measure clozapine levels although even with this drug there is only a weak correlation between plasma levels and clinical effect. The general guidance is that individuals who have not adequately responded to clozapine and have a plasma level below 350–500 µcg/L may benefit from a dose increase and those who suffer side effects and have a plasma level above this range may benefit from a dose reduction. Those with a plasma level above 1000 µcg/L are more likely to suffer seizures and cover using sodium valproate should be considered.

Adverse effects and antipsychotic medicines

There are a large number of adverse effects associated with antipsychotic medicines. Some of these effects, such as sedation, antilibido effects and weight gain may be considered to be of value with particular patients, but the susceptibility to such adverse effects is often a major factor in determining drug choice. Prescribing guidelines are available (Bazire, 2009; Taylor et al., 2009) which provide details of the relative likelihood of side effects with the various antipsychotic drugs. The major side effects are set out below.

Sedation

Although sedation is most commonly associated with chlorpromazine and clozapine, it is primarily related to dosage with other antipsychotics. Products claiming to be less sedating can often only substantiate this when used at low doses.

Weight gain and diabetes

Weight gain was a common feature of the first phenothiazine antipsychotics. It was originally thought this side effect was caused by a direct effect on metabolism. This side effect has also become a feature of some of the newer atypical antipsychotic medicines, particularly olanzapine and clozapine. This re-emergence of an old side effect with the new drugs has rekindled interest in the cause, which is now thought to be more associated with loss of control of food intake, rather than a direct effect on food metabolism. In addition to weight gain, these two atypical antipsychotic drugs have also been associated with increased incidence of diabetes. Controversy remains about whether there is a link between the weight gain and onset of diabetes, and whether the development of diabetes is more associated with the illness of schizophrenia than the drugs. Whatever the link, the controversy has led to the acceptance that people with schizophrenia often suffer poor physical health in addition to poor mental health and require regular monitoring of physical health risk factors. Increased concern about the physical and metabolic side effects of the antipsychotic medicines has led to increased requirements to monitor urea and electrolytes, blood lipids, full blood count, plasma glucose and blood pressure.

QT prolongation and cardiac risk

Some antipsychotic drugs are associated with changes to the QT interval measured on the elecrocardiogram (ECG) and, if given in high doses, may increase the risk of sudden cardiac death. Although, overall, the risk is low, monitoring the ECG has become part of normal practice, especially if high doses are used.

Anticholinergic side effects

Side effects such as dry mouth, constipation and blurred vision are particularly associated with piperidine phenothiazines.

Extrapyramidal side effects

Side effects such as akathisia, dystonia and parkinsonian effects are associated with typical antipsychotic drugs and occur frequently, particularly with depot antipsychotics, piperazine phenothiazines such as trifluoperazine and fluphenazine, and butyrophenones such as haloperidol. These side effects are reversible by using anticholinergic drugs or by dosage reduction. The common extrapyramidal effects include akathisia, dystonia and parkinson-like side effects (see the previous section)

Hormonal effects and sexual dysfunction

These side effects are primarily influenced by the effect on prolactin. This may result in galactorrhoea, missed menstrual periods and loss of libido. Some studies have suggested very high levels of sexual dysfunction with some antipsychotic drugs such as typical antipsychotic drugs and the atypical antipsychotics risperidone and amisulpride. However, in many of these studies the background level of such dysfunction is unclear. In addition, there has been a debate about the extent to which the long-term elevation of prolactin, particularly in the young, may be a cause of osteoporosis. What remains controversial though is at what point an elevated prolactin level should result in a discussion about choosing an alternative antipsychotic.

Postural hypotension and photosensitivity

Postural hypotension and photosensitivity are particularly associated with the aliphatic phenothiazines such as chlorpromazine.

Neuroleptic malignant syndrome (NMS)

The NMS is a rare but serious complication of antipsychotic drug treatment. The primary symptoms are rigidity, fever, diaphoresis, confusion and fluctuating consciousness. Confirmation can be sought through detection of elevated levels of creatinine kinase. The onset is particularly associated with high-potency typical drugs such as haloperidol, recent and rapid changes to dose and abrupt withdrawal of anticholinergic drugs. Treatment usually requires admission to a medical ward and withdrawal of all antipsychotic drugs.

Case 30.1

Lee is a 20-year-old man. His childhood was disrupted by constant changes to family membership. From an early age his behaviour was difficult but despite such changes by the age of 16 he was achieving well at school. Aged 17, he became involved with the illicit drug culture and increasingly lost interest in his studies. His parents became concerned as he appeared to undergo a change of personality, communicating with them very little. He eventually dropped out of school and took various short-term jobs. He was unable to sustain any long-term employment. He moved into a flat and seemed to live a twilight existence involving illicit drugs and all-night raves. Police were called to his flat following a violent disturbance. They found Lee living in squalor. He was surrounded by pieces of paper containing incomprehensible messages and was incoherent. He sat with a fixed stare, appearing quite inaccessible. He kept laughing and responding to imaginary people. He was very resistant to hospital admission, and had to be admitted under a section of the Mental Health Act 2007. On the ward he has remained quiet but appears to be in conversation with people who are not there.

Answers

Case 30.2

Gordon has relapsed for the third time this year, the pattern for the last two relapses being the same. His positive symptoms responded rapidly on both previous occasions. On the first he suffered severe extrapyramidal side effects with 30 mg daily of haloperidol and was subsequently stabilised and discharged on sulpiride 400 mg twice daily and procyclidine 5 mg twice daily. He almost immediately stopped taking the sulpiride, claiming not to be ill. During his second relapse he was successfully treated with risperidone 4 mg daily but again stopped the medicine.

Answers

In most cases, the use of a depot antipsychotic injection would be the easiest way to ensure adherence, although if Gordon is determined to avoid drug treatment this strategy is unlikely to be successful. In his case, the history of good response to oral risperidone and severe extrapyramidal side effects with a typical antipsychotic drug would indicate that the long-acting intramuscular formulation of risperidone may be a good choice.

Case 30.3

Sharon, aged 25, has a 3-year history of schizophrenia with many admissions to hospital. Throughout the period of her illness she has received a range of different oral antipsychotic drugs including chlorpromazine, haloperidol, sulpiride, risperidone and olanzapine, as well as the depot formulations of haloperidol and zuclopenthixol. For most of this time she has had a fixed belief that she is involved with a range of mythical beasts that sexually assault her. When she is ill these beings torment her. She currently receives zuclopenthixol decanoate 500 mg by intramuscular injection every week, olanzapine 10 mg at night, carbamazepine 200 mg three times daily, haloperidol 10 mg four times daily, and procyclidine 10 mg three times daily. She has remained on the ward for the last 4 months with no sign of improvement. She has greatly increased in weight, now approaching 20 stone. The team wishes to consider clozapine for Sharon.

Answers

Ideally all other treatments would be stopped and clozapine prescribed alone. Sometimes the final step of withdrawing other medicines may occur during the initiation phase with clozapine.

Altamura A., Sassella F., Santini A., et al. Intramuscular preparations of antipsychotics uses and relevance in clinical practice. Drugs. 2003;63:493-512.

American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, fourth ed. Washington: American Psychiatric Association; 1994.

Bazire S. Psychotropic Drug Directory: The Professionals’ Pocket Handbook and Aide Memoire. Salisbury: Fivepin Ltd; 2009.

Chakos M., Lieberman J.A., Hoffman E., et al. Effectiveness of second-generation antipsychotics in patients with treatment-resistant schizophrenia: a review and meta-analysis of randomized trials. Am. J. Psychiatry. 2001;158:518-526.

Cipriani A., Boso M., Barbui C. Clozapine combined with different antipsychotic drugs for treatment resistant schizophrenia. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev.. (3):2009. Art. No. CD006324 doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD006324.pub2. Available at: http://www2.cochrane.org/reviews/en/ab006324.html

Committee on Safety of Medicines. Clozapine and cardiac safety: updated advice for prescribers. Curr. Probl. Pharmacovigil.. 2002;28:8.

Kane J., Honigfield G., Singer J., et al. Clozapine for the treatment-resistant schizophrenic; a double blind comparison with chlorpromazine (clozaril collaborative study). Arch. Gen. Psychiatry. 1988;45:789-796.

Lieberman J.A., Safferman A.Z., Pollack S., et al. Clinical effects of clozapine in chronic schizophrenia: response to treatment and predictors of outcome. Am. J. Psychiatry. 1994;15:1744-1752.

National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence. Schizophrenia: Core Interventions in the Treatment and Management of Schizophrenia in Adults in Primary and Secondary Care. Clinical guideline 82 update http://www.nice.org.uk/nicemedia/live/11786/43608/43608.pdf, 2009.

Paton C., Whittington C., Barnes T. Augmentation with a second antipsychotic in patients with schizophrenia who partially respond to clozapine: a meta-analysis. J. Clin. Psychopharmacol.. 2007;27:198-204.

Royal College of Psychiatrists. Consensus Statement on High-Dose Antipsychotic Medication. London: RCP; 2006. CR138

Taylor D., Paton C., Kapur S. The Maudsley Prescribing Guidelines, 10th ed. London: Informa Healthcare; 2009.

Tuunainen A., Wahlbeck K., Gilbody S. Newer atypical antipsychotic medication versus clozapine for schizophrenia. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev.. (1):2000. Art No. CD000966. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD000966

World Health Organization. International Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems, 10th ed. Geneva: World Health Organization; 1992. (ICD 10)

Barbui C., Signoretti A., Mule S., et al. Does the addition of a second antipsychotic drug improve clozapine treatment? Schizophr. Bull.. 2009;35:458-468.

Bobo W.V., Stovall J.A., Knostman M., et al. Converting from brand-name to generic clozapine: a review of effectiveness and tolerability data. Am. J. Health Syst. Pharm.. 2010;67:27-37.

Gao K., Gajwani P., Elhaj O., Calabrese J.R. Typical and atypical antipsychotics in bipolar depression. J. Clin. Psychiatry. 2005;66:1376-1385.

Lang U., Willbring M., von Golitschek R., et al. Clozapine-induced myocarditis after long-term treatment: case presentation and clinical perspectives. J. Psychopharmacol.. 2008;22:576-580.

Leucht S., Komossa K., Rummel-Kluge C., et al. A meta-analysis of head-to-head comparisons of second-generation antipsychotics in the treatment of schizophrenia. Am. J. Psychiatry. 2009;166:152-163.

Lieberman J.A., Stroup T.S., McEvoy J.P., for the Clinical Antipsychotic Trials of Intervention Effectiveness (CATIE) Investigators. Effectiveness of antipsychotic drugs in patients with chronic schizophrenia. N. Engl. J. Med.. 2005;353:1209-1223.

National Collaborating Centre for Mental Health. Schizophrenia: The NICE Guideline on Core Interventions in the Treatment and Management of Schizophrenia in Adults in Primary and Secondary Care. London: British Psychological Society; 2010.