Epidemiology of skin disease

Skin disease is very common. About 10% of a general practitioner’s workload and 6% of hospital outpatient referrals can be accounted for by skin problems. Skin disease is also economically significant; it is a major occupational cause of loss of time from work and the third most common industrial disease (p. 124).

In any discussion of epidemiology, it is important first to define the terms used:

Prevalence refers to the proportion of a defined population affected by a disease at any given time.

Prevalence refers to the proportion of a defined population affected by a disease at any given time.

Incidence is defined as the proportion of a population experiencing the disorder within a stated period of time (usually 1 year).

Incidence is defined as the proportion of a population experiencing the disorder within a stated period of time (usually 1 year).

The type, prevalence and incidence of skin disease all depend on social, economic, geographical, racial, cultural and age-related factors.

Skin disease in the general population

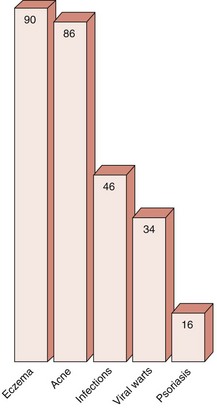

Reliable population statistics are difficult to obtain, but it appears that, in Europe, the prevalence of skin disease needing some sort of medical care is about 20%. Eczema, acne and infective disorders (including warts) are the commonest complaints (Fig. 1). Only a minority seek medical advice.

Skin disease in community and specialized clinics

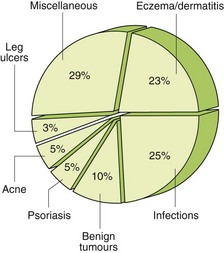

The precise proportion of skin disorders seen in a community setting (Fig. 2) will vary with the age structure of the population served, the amount and type of industry in the area and socioeconomic factors. Demographic studies may reveal a trend; for example, for unknown reasons, atopic eczema has become more common over the last 30 years.

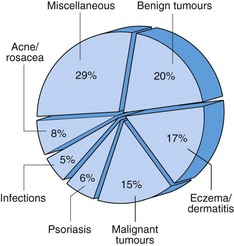

Patients seen in a specialist dermatology clinic are a selected population (Fig. 3). In some countries, e.g. the UK, a general practitioner will have referred them; in other places, self-referral may depend on the availability of medical insurance. Referral patterns vary between different regions, depending on local facilities, interests and customs. In Europe, within a year, just over 1% of the population is referred for a dermatological opinion. In the early 2010s, a quarter of all new referrals required a surgical procedure.

Socioeconomic factors

Improvements in the standard of living resulting from the nineteenth-century industrialization of Europe were accompanied by a fall in the incidences of most infectious diseases and a decline in the infant mortality rate. Better nutrition, improved living conditions and the introduction of hygienic measures are thought to have been important. Most forms of infectious disease, including those of the skin, are now more common in the developing world than in western countries, and it would seem that the poorer standards of living are a cause of this.

However, industrialization brings its own problems. Occupational dermatitis is quite common in industrialized countries, and mild cases are often not reported. Increased sophistication in western countries also means that patients now want something done about disorders or minor imperfections that would not have bothered past generations.

Changes in social fashion have also brought about changes in skin disease. For example, the habit of sunbathing, which became popular in the 1970s, seems to have resulted in an increase in the incidence of malignant melanoma from the 1980s to the present.

The media have also had an effect: the numerous articles and programmes on the potential problems associated with a change in pigmented naevi have produced a flood of referrals of worried patients seeking reassurance about their lesions! However, it is still true that many people with minor skin problems do not consult a doctor.

Geographical factors

Humid conditions found in hot countries predispose to fungal and bacterial infections, and to other conditions such as ‘prickly heat’ (miliaria: an itchy eruption due to blocked sweat ducts). Ultraviolet radiation in sunny climes will result in actinic damage and malignant change in the skin of non-pigmented migrants to the area.

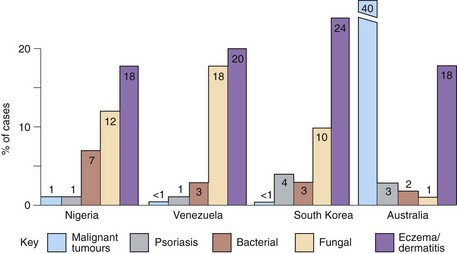

Figure 4 shows a comparison between some common complaints in different geographical locations. The rates for bacterial and fungal infections show variation, and skin cancers are more common in Australia. However, the figures for eczema/dermatitis are remarkably constant.

Racial and cultural factors

Quite apart from the obvious differences in pigmentation, the skin structure varies between the different races (p. 122). For example, hair is often spiral in black Africans but straight in mongoloids. In caucasians, hair is more variable and may be straight, wavy or helical. Skin tumours and actinic damage are seen more in caucasians than in black Africans, with mongoloids showing an intermediate incidence. Keloids and hair problems, such as pseudofolliculitis (p. 123), are more common in black Africans, whereas mongoloid skin has a tendency to become lichenified and acne may be less frequent. Vitiligo appears to have a similar incidence in all races, but is more conspicuous and may have a greater psychological impact in those with a dark skin.

Cultural factors may bring problems. For example, tight braiding of the hair, practised by some black Africans, may result in alopecia, whereas the use of certain traditional oils or cosmetics can produce dermatitis or a change in pigmentation.

Age and sex prevalence of dermatoses

Different disorders are associated with different times of life (Table 1). Some disorders occur throughout life but are more common at certain ages, whereas others are almost exclusively encountered in defined age groups. For example, atopic eczema is most common in infants, acne is mainly seen in adolescents and psoriasis has its peak onset in the second and third decades of life. Certain disorders tend to appear in middle age, e.g. pemphigus and malignant melanoma. In old age, degenerative and malignant skin conditions are often found. Thus, the age structure of the population will influence the type of dermatology practised.

Table 1 Age-related onset of selected skin disorders

| Age | Disorder |

|---|---|

| Childhood | Port wine stain and strawberry naevi, ichthyosis, erythropoietic protoporphyria, epidermolysis bullosa, atopic eczema, infantile seborrhoeic dermatitis, urticaria pigmentosa, viral exanthems, viral warts, molluscum contagiosum, impetigo |

| Adolescence | Melanocytic naevi, acne, psoriasis (notably guttate), seborrhoeic dermatitis, vitiligo, pityriasis rosea |

| Early adulthood | Psoriasis, seborrhoeic dermatitis, lichen planus, dermatitis herpetiformis, lupus erythematosus, vitiligo, tinea versicolor |

| Middle age | Porphyria cutanea tarda, lichen planus, rosacea, pemphigus vulgaris, venous ulceration, malignant melanoma, basal cell carcinoma, mycosis fungoides |

| Old age | Asteatotic eczema, generalized pruritus, bullous pemphigoid, venous and arterial ulcers, seborrhoeic warts, solar keratosis, solar elastosis, Campbell-de-Morgan spots, basal cell carcinoma, squamous cell carcinoma, herpes zoster |

Some conditions are more common to a specific gender (Table 2).

Table 2 Skin disorders with a male or female preponderance

| Sex | Disorder |

|---|---|

| Female | Palmoplantar pustulosis, lichen sclerosus, lupus erythematosus, systemic sclerosis, morphoea, rosacea, dermatitis artefacta, venous ulceration, in situ squamous cell carcinoma, malignant melanoma |

| Male | Seborrhoeic dermatitis, dermatitis herpetiformis, porphyria cutanea tarda, polyarteritis nodosa, pruritus ani, tinea pedis and cruris, mycosis fungoides, squamous cell carcinoma, actinic keratosis |

Epidemiology

The commonest skin diseases in the general community are eczema, acne and infections, including viral warts.

The commonest skin diseases in the general community are eczema, acne and infections, including viral warts.

About 20% of the general population have some sort of skin disorder requiring medical attention.

About 20% of the general population have some sort of skin disorder requiring medical attention.

Skin disease accounts for more than 10% of all consultations in general practice.

Skin disease accounts for more than 10% of all consultations in general practice.

Better living conditions reduce skin infection, but excess sun on a white skin predisposes to skin cancer.

Better living conditions reduce skin infection, but excess sun on a white skin predisposes to skin cancer.