Tropical infections and infestations

Infections constitute one of the biggest problems in dermatology in tropical countries of the developing world. Leprosy, for example, despite being a treatable disease, continues to ravage in many parts of the globe.

However, tropical infections may also be seen in countries in which they are non-endemic – among visitors and immigrants, or when acquired abroad by the indigenous population.

Leprosy

Leprosy is a chronic disease caused by Mycobacterium leprae. This is an acid- and alcohol-fast bacillus that cannot be cultured in the laboratory. Nasal droplets spread the infection, and the incubation period is several years. The disease is usually acquired in childhood, as the risk to exposed adults is about 5%. Leprosy is no longer endemic in northern Europe. Most cases are found in India, Brazil, Indonesia, Myanmar, Madagascar and Nepal. The manifestation of the disease depends on the degree of the delayed (type IV) hypersensitivity response in the infected individual. Those with strong cell-mediated immunity develop the tuberculoid type, whereas those in whom the cell-mediated reactivity is poor develop lepromatous leprosy. Borderline lesions are seen in those whose immune state is intermediate.

M. leprae has a predilection for nerves and the dermis but, in the lepromatous type, infection may be much more widespread. Tuberculoid leprosy is characterized by a granulomatous reaction in the nerves and dermis with no acid-fast bacilli demonstrated using the Ziehl–Neelsen stain. In contrast, bacilli are plentiful in the dermis of the lepromatous type, and large numbers of macrophages are seen on microscopy.

Clinical presentation

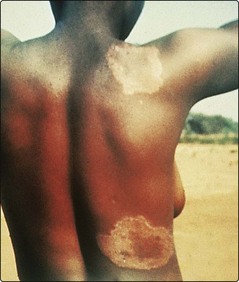

Tuberculoid leprosy affects the nerves and the skin. Nerves may be thickened, and anaesthesia or muscle atrophy is found. Skin lesions often occur on the face, and as few as one or two may be seen. They usually take the form of raised red plaques with a hypopigmented centre, which is typically dry and hairless (Fig. 1). Sensation may be impaired within the plaque.

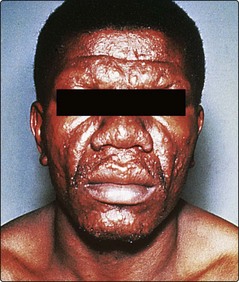

The skin lesions of lepromatous leprosy are multiple and take the form of macules, papules, nodules and plaques. They are symmetrical and tend to involve the face, arms, legs and buttocks. Sensation is not impaired. Untreated, the condition is infectious from the nasal involvement. Progression gives a thickened furrowed appearance to the face (leonine facies) with loss of eyebrows (Fig. 2). Borderline leprosy shows features intermediate between lepromatous and tuberculoid.

Leprosy must be distinguished from a variety of other dermatological conditions (Table 1).

Table 1 Differential diagnosis of leprosy

| Type of leprosy | Differential diagnosis |

|---|---|

| Tuberculoid | Vitiligo, pityriasis versicolor, pityriasis alba, sarcoidosis, lupus vulgaris, granuloma annulare, post-inflammatory hypopigmentation |

| Lepromatous | Disseminated cutaneous leishmaniasis, yaws, guttate psoriasis, discoid lupus erythematosus, mycosis fungoides |

Complications

Tuberculoid leprosy may result in bone damage to a hand or foot from repeated trauma to an insensitive area. In lepromatous leprosy, nasal damage may progress to a saddle nose defect. Ichthyosis, testicular atrophy and leg ulcers are seen. A peripheral neuropathy leads to shortening of the toes and fingers from repeated trauma. Lepra reactions, which result from an upgrading or a downgrading of the immune response, can produce nerve destruction or acute skin lesions.

Management

Lepromatous (multibacillary) leprosy is treated with rifampicin, dapsone and clofazimine. Treatment is for at least 2 years, continued until skin smears are negative. Tuberculoid (paucibacillary) leprosy responds to rifampicin and dapso ne, given for 6 months. The complications of leprosy may require the skills of rehabilitation specialists and orthopaedic and plastic surgeons.

In countries where leprosy is endemic, the education of the public about the disease is important in reducing the stigma attached to sufferers. Public health programmes aimed at leprosy control are active in several countries.

Leishmaniasis

Leishmaniasis is a disease caused by Leishmania protozoa, which are transmitted by sand fly bites. It exists in tropical and subtropical areas in a cutaneous, mucocutaneous or visceral form. Three protozoa cause disease:

1. Leishmania tropica causes the cutaneous ‘oriental sore’ and is seen around the Mediterranean coast, in the Middle East and in Asia.

2. L. braziliensis, endemic in Central and South America, leads to cutaneous and mucosal disease.

3. L. donovani is widely distributed in Asia, Africa and South America, and causes visceral disease (kala-azar) with associated skin lesions.

Clinical presentation

Oriental sore is a common infection in endemic areas normally affecting children, who subsequently develop immunity. In non-endemic regions, it is not infrequently seen in travellers after a Mediterranean holiday. The face, neck or arms are usually affected. At the site of inoculation, a red or brown nodule appears, which either ulcerates or spreads slowly to form a crust-topped plaque (Fig. 3). Untreated, the lesion will heal in 6–12 months, although a chronic form is seen. In mucocutaneous leishmaniasis, the skin lesion resembles an oriental sore but, subsequently, necrotic ulcers affect the nose, lips and palate with deformity. Kala-azar principally affects children and has a significant mortality. It causes hepatomegaly, splenomegaly, anaemia and debility. The cutaneous signs are patchy pigmentation on the face, hands and abdomen.

Fig. 3 The oriental sore of cutaneous leishmaniasis.

Small lesions may respond to cryotherapy. Otherwise, intravenous sodium stibogluconate may be given.

Leishmaniasis must be distinguished from some other disorders (Table 2).

Table 2 Differential diagnosis of leishmaniasis

| Variant | Differential diagnosis |

|---|---|

| Cutaneous | Lupus vulgaris, leprosy, discoid lupus erythematosus |

| Mucocutaneous | Syphilis, yaws, leprosy, blastomycosis |

| Kala-azar | Leprosy |

Larva migrans

Larva migrans is a ‘creeping’ eruption due to penetration of the skin by the larval stage of animal hookworms. Larva migrans is often acquired from tropical beaches where ova from the hookworms of dogs and cats have hatched into larvae that are able to penetrate the human skin. Penetration usually occurs on the feet. The larvae advance at the rate of a few millimetres a day in a serpiginous route causing red intensely itchy tracks to appear (Fig. 4). They eventually die spontaneously after a few weeks, as they cannot complete their life cycle in humans.

Topical 10% thiabendazole cream or a single oral dose of ivermectin (200 mcg/kg) is usually effective.

Deep mycoses

Deep mycoses are defined as the invasion of living tissue by fungi, causing systemic disease. Brief details are given in Table 3.

| Mycosis | Clinical features | Management |

|---|---|---|

| Actinomycosis (filamentous bacteria) | A chronic suppurating granulomatous infection with multiple sinuses discharging yellow granules, particularly around the jaw, chest and abdomen | Long-term high-dose penicillin, surgical excision |

| Blastomycosis | Ulcerated discharging nodules that show central clearing with scarring; may spread from pulmonary infection | Oral itraconazole, systemic amphotericin B or ketoconazole |

| Histoplasmosis | Seen in immunosuppressed patients who develop lung disease with granulomatous skin lesions | Oral itraconazole or ketoconazole, or systemic amphotericin B |

| Mycetoma | A chronic granulomatous infection usually of the foot, involving skin, subcutaneous tissue and bones, due to several types of fungi or actinomycetes; nodules with abscesses, sinuses, ulceration and tissue necrosis result | Depends on the organism; surgical excision, dapsone with co-trimoxazole, and itraconazole may help |

| Sporotrichosis | An abscess forms with nodules subsequently occurring proximally along the line of lymphatic drainage | Potassium iodide, itraconazole or terbinafine |

Filariasis

Filariasis is seen in the tropics and is often due to the nematode worm Wuchereria bancrofti. Lymphatic damage ultimately results in gross oedema of the legs and scrotum (‘elephantiasis’). Treatment is with diethylcarbamazine.

Onchocerciasis

Onchocerciasis is a disease affecting the eyes and skin, caused by the worm Onchocerca volvulus. It is endemic in Africa and Central America and is an important cause of blindness. A gnat transmits the worm to humans. Dermal nodules with lichenification and pigmentary change follow an itchy papular eruption. Microfilariae invade the eye and result in blindness.

Ivermectin, as a single dose, is the drug of choice for onchocerciasis. Retreatment at 6- or 12-month intervals may be needed until the worms die out.

Tropical infections

Leprosy: tuberculoid and lepromatous forms mainly affect the skin and nerves; treatment is with dapsone, rifampicin and clofazimine.

Leprosy: tuberculoid and lepromatous forms mainly affect the skin and nerves; treatment is with dapsone, rifampicin and clofazimine.

Leishmaniasis: cutaneous, mucocutaneous and visceral types; treatment is with sodium stibogluconate.

Leishmaniasis: cutaneous, mucocutaneous and visceral types; treatment is with sodium stibogluconate.

Larva migrans: creeping eruption due to animal hookworms; responds to thiabendazole cream or oral ivermectin.

Larva migrans: creeping eruption due to animal hookworms; responds to thiabendazole cream or oral ivermectin.

Deep mycoses: serious infections that may be difficult to eradicate.

Deep mycoses: serious infections that may be difficult to eradicate.

Onchocerciasis: an important cause of blindness; skin shows lichenified nodules and pigmentary changes. Treatment is with oral ivermectin.

Onchocerciasis: an important cause of blindness; skin shows lichenified nodules and pigmentary changes. Treatment is with oral ivermectin.