CHAPTER 48 Renal Disease and Organ Transplantation

End-stage organ disease can occur in persons regardless of socioeconomic status or age, creating a need for organ transplant to sustain quality of life. Solid organ transplant refers to the removal of a diseased organ such as a heart, liver, pancreas, lung, intestine, or kidney and replacement with a healthy donor organ. One commonality of organ transplant recipients, regardless of the cause of the condition, the organ affected, or comorbidities, is susceptibility to organ rejection and infection. With current immunosuppressive therapy, acute organ rejection is a rare consequence; however, sepsis and chronic rejection continue to threaten the medical stability of the organ transplant recipient.

As treatment for end-stage organ disease advances and individuals live longer, dental hygienists are likely to treat both solid organ transplant candidates and solid organ transplant recipients. However, there are no uniform pretransplant dental protocols for transplant candidates.1 Furthermore, dental protocols within the same hospital center may differ based on organs transplanted. Understanding the medical complexities associated with solid organ transplantation is essential if safe, high-quality care is to be provided to individuals before and after their transplants.

Although there is no concrete evidence to support the impact of oral infections on organ transplantation, at this time dental and renal experts consider infections of oral origin as potentially dangerous to kidney transplant patients. As a result, several sensible recommendations for providing oral care to the candidate for solid organ transplant have been published and include the following1:

UNITED NETWORK FOR ORGAN SHARING

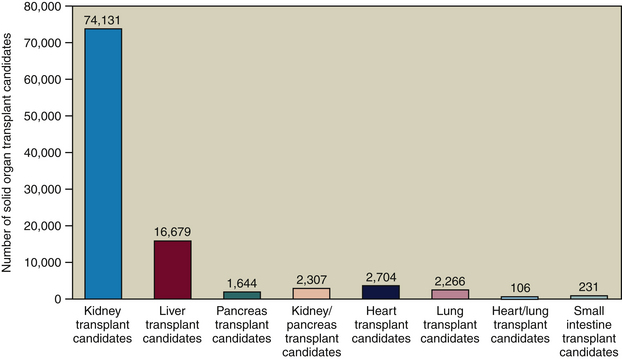

The United Network for Organ Sharing (UNOS) is a nonprofit, scientific, and educational organization that maintains the nation’s only Organ Procurement and Transplantation Network (OPTN). Their “waiting list” includes persons who need solid organ transplantation in the United States. UNOS manages the OPTN, establishes organ donation policies and procedures, facilitates organ matching and placement, and maintains a national database of organ transplant candidates and donors. Although waiting periods vary, oral healthcare providers can determine average waiting times for specific hospitals and geographic areas (Figure 48-1). With this information, a dental hygiene care plan can be developed for the client in the pretransplant waiting phase to avoid postoperative complications from poor oral health and hygiene.

Figure 48-1 Number of persons awaiting organ transplant in 2007.

(Data from United Network for Organ Sharing, Richmond, Virginia.)

Of the more than 98,000 solid organ transplant candidates listed with UNOS, only about 27,000 organ transplant procedures are performed annually. Therefore, pretransplant patients are more likely to receive dental hygiene care than post-transplant patients. Furthermore, because the majority of transplant candidates are waiting for kidney transplantation, they are predialysis or dialysis patients.

SOLID ORGAN TRANSPLANT CANDIDATES

End-Stage Renal Disease

The National Kidney Foundation (NKF) estimates that 26 million Americans have chronic kidney disease (CKD) and another 20 million are undiagnosed or at risk for CKD; these estimates are anticipated to grow as the population ages. Far more people are awaiting renal solid organ transplants than any other type of solid organ transplant because dialysis is a bridge to transplantation. Dialysis is a method of cleaning and filtering wastes and toxins from the blood when the kidneys lose their function in end-stage renal disease (ESRD). With ESRD, treatment modalities include the following:

Although renal transplantation is not a cure for ESRD, it provides a less inhibited lifestyle than required with dialysis; therefore many (though not all) patients seek consideration for the National Solid Organ Waiting List.

Kidney Disease Outcomes Quality Initiative

The world-recognized Kidney Disease Outcomes Quality Initiative (K/DOQI) publishes evidence-based practice guidelines for all stages and aspects of kidney disease: anemia and CKD, diabetes and CKD, hemodialysis adequacy, PD, vascular access, anemia management, nutrition, disease classification, dyslipidemia, bone metabolism disorders, and cardiovascular disease in people living with kidney disease.2

Renal Physiology

Kidneys perform three essential bodily functions: excretion of nitrogenous waste products; regulation of volume, composition, and acid-base balance of plasma; and synthesis of hormones necessary for erythrocyte production, bone metabolism, and maintenance of blood pressure.3 When kidney function declines, wastes and excess fluids begin to accumulate; hypertension and anemia often develop. Chronic renal failure, also known as chronic kidney disease (CKD), is defined as the gradual loss of the ability of the kidneys to remove wastes, concentrate urine, and conserve electrolytes.

Signs and symptoms of CKD may include the following:

Some people do not notice early signs or symptoms, and many individuals are not diagnosed until there is irreversible, bilateral damage to the kidneys. The most accurate means of measuring renal function is via the glomerular filtration rate (GFR), an expression of the quantity of glomerular filtrate created each minute in the renal nephrons. The GFR can determine stages of CKD as follows:

Stage 1: Renal damage with normal GFR (GFR ≥90). Renal damage may occur before a reduction in GFR. Primary treatment goals are to delay the progression of CKD and reduce risk of cardiovascular disease.

Stage 1: Renal damage with normal GFR (GFR ≥90). Renal damage may occur before a reduction in GFR. Primary treatment goals are to delay the progression of CKD and reduce risk of cardiovascular disease. Stage 2: Renal damage with mild decrease in GFR (GFR 60 to 89). Treatment goals are to delay the progression of CKD and reduce risk of cardiovascular disease.

Stage 2: Renal damage with mild decrease in GFR (GFR 60 to 89). Treatment goals are to delay the progression of CKD and reduce risk of cardiovascular disease. Stage 3: Moderate decrease in GFR (GFR 30 to 59). Anemia and bone metabolism disorders become more common.

Stage 3: Moderate decrease in GFR (GFR 30 to 59). Anemia and bone metabolism disorders become more common. Stage 5: ESRD (GFR <15). Patient is unable to maintain essential life functions unless dialysis is initiated to remove fluid and nitrogenous wastes.

Stage 5: ESRD (GFR <15). Patient is unable to maintain essential life functions unless dialysis is initiated to remove fluid and nitrogenous wastes.Preventive treatment to delay (or avoid) ESRD includes the pharmacologic use of angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors and angiotensin receptor blockers (ARBs).

Dialysis Treatment Modalities

In hemodialysis the person’s blood (a few ounces at a time) is cleansed with a special filter. The dialysis access (vascular access, fistula or graft) is surgically created, usually in the forearm (Figure 48-2), and during each treatment session an intravenous cannula is inserted into the vascular access. Hemodialysis treatments may be performed in a dialysis center (typically three times a week for a prescribed period of time each session) or in the home with a special hemodialysis machine.

Alterations in the dental hygiene care plan for the person receiving hemodialysis treatments are as follows:

Do not take blood pressure readings in the dialysis access arm (this could cause the access to become occluded or infected).

Do not take blood pressure readings in the dialysis access arm (this could cause the access to become occluded or infected). Avoid treatment after dialysis treatment on the same day, because of coagulation complications associated with the use of heparin (blood anticoagulant therapy) administered during dialysis.

Avoid treatment after dialysis treatment on the same day, because of coagulation complications associated with the use of heparin (blood anticoagulant therapy) administered during dialysis.Peritoneal dialysis (PD), like hemodialysis, filters the blood of the person with ESRD. However, this treatment modality uses the person’s own peritoneal lining to filter the blood. A catheter is placed into the person’s abdomen, giving access to the peritoneal lining; the person uses this access to inject a dialysate fluid into the peritoneal lining. This fluid contains dextrose, salt, and other minerals dissolved in water; waste products and extra body fluid pass from the person’s blood into the dialysis solution. After a prescribed period of time the waste-filled solution is drained and immediately replaced with a fresh solution, and the dialysis process of filtering the blood begins again.

The two primary forms of PD are as follows:

Continuous Cycler-Assisted Peritoneal Dialysis (CCPD), in which treatment is performed by a machine. Although PD is offered in some dialysis centers, persons who chose this modality do so because it can be self-administered at home, and it eliminates the need for an intravenous cannula in a vascular access three times per week.

Continuous Cycler-Assisted Peritoneal Dialysis (CCPD), in which treatment is performed by a machine. Although PD is offered in some dialysis centers, persons who chose this modality do so because it can be self-administered at home, and it eliminates the need for an intravenous cannula in a vascular access three times per week.Alteration in the dental hygiene care plan for persons receiving PD treatments are as follows:

Consult with and obtain clearance from the nephrologist to:

Consult with and obtain clearance from the nephrologist to:

Unless patients have comorbidities or conditions that indicate antibiotic prophylaxis per the American Heart Association guidelines or the American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons guidelines, PD patients usually do not require prophylactic antibiotic premedication. Cardiovascular complications, the most prevalent cause of mortality, are common within the hemodialysis and PD population. With that in mind, all patients should be medically evaluated for antibiotic prophylaxis based on risk factors present.

Unless patients have comorbidities or conditions that indicate antibiotic prophylaxis per the American Heart Association guidelines or the American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons guidelines, PD patients usually do not require prophylactic antibiotic premedication. Cardiovascular complications, the most prevalent cause of mortality, are common within the hemodialysis and PD population. With that in mind, all patients should be medically evaluated for antibiotic prophylaxis based on risk factors present.Etiology

Diabetes mellitus and hypertension are the most prevalent causes of ESRD. Regardless of the cause or treatment modality chosen, ESRD patients are prone to comorbidities such as diabetes and hypertension that must also be considered in the process of care. Secondary medical conditions are results of a ripple effect that occurs from another condition. For instance, consider a person living with ESRD and on dialysis. Although the primary cause of ESRD in this person may be diabetes mellitus, owing to a cascade of complications (fluid retention, anemia, and so on) the person now has secondary hypertension. In addition to secondary diabetes and hypertension, anemia, secondary hyperparathyroidism, and malnutrition are serious conditions to manage in persons receiving dialysis therapy.

Cardiovascular Disease and Inflammation

Persons with renal disease have a 10 to 100 times greater risk of cardiovascular disease.4 Regardless of the stage of CKD, inflammation plays an important role in clinical outcomes.

Anemia

With normal, healthy renal function, the kidneys produce the hormone erythropoietin (EPO), which stimulates bone marrow to produce red blood cells, essential in delivering oxygen throughout the body. Diseased kidneys fail to make enough EPO; therefore less oxygen is distributed throughout the body. Anemia, the reduction in the mass of circulating red blood cells, is not a disease in itself but rather a symptom of other illnesses (Figure 48-3). Anemia may be present in the early stages of renal disease and worsens as renal disease progresses. Nearly all people living with end-stage renal failure (<10% renal function) have anemia. Additional factors that contribute to anemia in people with ESRD include iron deficiency, foliate deficiency, shortened red blood cell life span, hypothyroidism, secondary hyperparathyroidism, blood loss, and acute and chronic inflammation. Oral manifestations of anemia include pallor of the oral mucosa, glossitis (an early sign of folate or vitamin B12 deficiency), recurrent aphthae, candidiasis, and angular stomatitis (cheilitis). Fatigue and increased risk of infection are common systemic complications of anemia. Furthermore, anemia may also contribute to cardiovascular complications.

According to K/DOQI guidelines, persons living with kidney disease are considered anemic when hemoglobin levels are less than 11 g/dL or hematocrit levels fall below 33%. Anemia treatment for those with kidney disease may include a genetically engineered form of the EPO hormone, iron supplements, and/or foliate supplements.

Mineral and Bone Disorder

A serious complication of renal disease characterized by an excessive secretion of parathyroid hormone (PTH) is known as mineral and bone disorder (formerly referred to as secondary hyperparathyroidism). As renal disease progresses, the kidneys lose their ability to excrete phosphorus from the body and produce the active form of vitamin D necessary in bone metabolism. These changes result in decreased serum calcium. In response to regain balance, increases in PTH result, causing hypercalcemia. This impediment in bone metabolism was once diagnosed as a bone disease. However, mineral and bone disorder is now recognized for causing greater potential complication, calcifications within the body’s vascular system and organs.

Persons with mineral and bone disorder must limit phosphorus intake. In addition, vitamin D supplements and medications known as phosphorus binders may be prescribed to reduce absorption of phosphorus. Furthermore, medications that target the patient’s serum calcium levels may be prescribed. A renal dietitian will work with the nephrologist and patient to plan a renal-friendly diet (see the discussion of nutrition in the next section).

Oral manifestations of mineral and bone disorder may include areas of abnormal calcium leaching from osseous structures and calcium deposits on and in teeth, soft tissues, vasculature, and/or organs. In addition to dental calculus, calcium deposits may be visible on panoramic radiographs as calcifications in the carotid arteries, on periapical radiographs as narrowing of the pulp chamber or abnormal calcifications in soft tissues, or as a radiolucent osseous lesion (also known as a brown tumor). Other radiographic manifestations include loss of lamina dura, loss of trabecular pattern, and bone density changes. Early diagnosis and management of bone metabolism disorders are essential for positive outcomes. Dental radiographs may help screen patients with CKD for calcifications because of their high diagnostic potential.5

Nutrition

To offset complications associated with renal disease, patients are typically prescribed a renal diet that restricts fluid and sodium intake (owing to decreased renal output, excess body fluid, and hypertension) and limits dietary phosphorus and potassium. Fluid restrictions result in reduced salivary flow that interferes with the cleansing role of saliva. Therefore patients receiving dialysis treatment commonly have greater than normal deposits of dental calculus. Uremia compounds the dental calculus problem. During dialysis treatments, patients frequently require dietary protein to aid in tissue healing and to avoid infection.

Salivary pH

As kidney disease progresses, nitrogenous materials accumulate in the body, producing a condition known as uremia and altering the pH of blood and saliva. Whether uremia is a protective factor or a risk factor for dental caries remains unclear.6-8 Dialysis patients are often advised to “suck on a lemon” and chew on ice to cope psychologically and physically with chronic xerostomia. Other alternatives should include daily chewing of xylitol gum that contains at least 1.55 g of xylitol as a therapeutic dose, daily sucking on xylitol mints that contain at least 1.55 g of xylitol as a therapeutic dose, sucking on frozen grapes, and/or sucking on a button tied with a 20-inch string to prevent accidental ingestion. Oral self-care may include use of a power toothbrush, oral irrigation (caution patient about fluid restrictions and ingestion), and sleeping with a humidifier to aid in moisturizing the oral and nasopharyngeal passages. The dental hygienist should consult with the patient’s renal dietitian to be sure that all oral self-care recommendations and products are within the patient’s prescribed renal diet and medical treatment plan.

Periodontal Disease

At best there is a moderate relationship between periodontal disease and renal insufficiency.9 The relationship between periodontal disease and renal disease is the subject of ongoing research.

Communication with Others on the Transplantation Team

The nephrology team usually includes the following:

In the pretransplant phase the dental hygienist will likely communicate solely with the pretransplant coordinator on the renal transplant team. In most instances this will be a registered nurse or physician’s assistant. The pretransplant coordinator is responsible for coordinating all required preoperative appointments for the transplant candidate.

In the post-transplant phase the patient will receive care at a transplant center or return to a primary healthcare provider if a transplant center is not located nearby. The dental hygienist should consult with the patient’s current healthcare provider to determine the patient’s medical stability and precautions during dental hygiene care.

A reliable bridge to transplantation does not yet exist for liver, heart, and lung transplant candidates; therefore they are often in more critical condition and treated in a hospital setting. In this situation, oral healthcare providers consult directly with the patient’s medical specialist. These patients should be carefully evaluated before dental hygiene care to determine a safe and effective course of action.

DENTAL CARE AFTER SOLID ORGAN TRANSPLANT

Gingival Enlargement

The discovery of the drug cyclosporine provided a breakthrough in solid organ transplantation. However, cyclosporine increases risk of nephrotoxicity, the quality or state of being toxic to kidney cells. Most transplant recipients are treated with a trio of immunosuppressive medications (e.g., cyclosporine, prednisone, and mycophenolate mofetil). However, even prednisone can cause long-term complications of bone metabolism and adrenal crisis; therefore the pursuit of immunosuppressive therapy with minimal side effect continues.

The research literature is replete with instances of drug-influenced gingival enlargement in solid organ transplant recipients. Gingival enlargement is another adverse side effect associated with immunosuppressive therapy. Gingival enlargement may be due to poor oral hygiene and/or increased sensitivity to cyclosporine. Although modifications in immunosuppressive therapy may be explored when gingival enlargement is a concern, transplant physicians are reluctant to alter the immunosuppressive therapy when the patient’s condition is medically stable. Drug-influenced gingival enlargement has been less common with the immunosuppressive medication tacrolimus.10

Prevention of gingival enlargement is best. Meticulous daily oral self-care should emphasize optimal oral biofilm removal to avoid infection and inflammation, and frequent oral debridement (3- to 4-month continued-care intervals) by the dental hygienist to reduce risk of gingival enlargement. Immunosuppressive therapy can mask inflammation.

Infection

Immunosuppressive therapy is at its most aggressive level in transplant recipients immediately after transplant surgery. In the months after surgery the patient’s immunosuppressive therapy is gradually reduced and then maintained at a level that balances the threat of rejection and infection. Any infection (such as vascular or catheter infections, pneumonia, cellulitis, or periodontal abscess) can be reactivated or exacerbated in the immediate postoperative period during the introduction of immunosuppressive therapy or afterward, depending on the overall state of immunosuppression.11 When providing care, oral healthcare providers should educate patients about the potential risk dental infections play in organ rejection and infection.

Infective Endocarditis and Invasive Dental Procedures

The need for antibiotic prophylaxis for invasive dental procedures in clients who have undergone solid organ transplant is controversial. Although surveys of transplant providers demonstrate opposing views, the majority of providers do recommend antibiotic prophylaxis for invasive dental procedures. Neither the American Heart Association nor K/DOQI addresses this issue. Therefore organ transplant recipients should be individually evaluated for infectious risk, and medical and dental consultation is necessary to determine the following:

Candidiasis and Viral Infections

Patients taking immunosuppressive therapy often experience candidiasis or recurrence of herpetic infections. The oral healthcare provider works with the transplant team to determine appropriate treatment.

Malignancies

Organ transplant recipients have an increased incidence of squamous and basal cell carcinomas; therefore annual screening of the skin and oral pharyngeal area is indicated. Liver transplant recipients with a history of tobacco use and/or alcoholism are at particular risk for oral pharyngeal cancer.

AFTER SOLID ORGAN TRANSPLANTATION

Immediately after transplantation, only emergency dental care is recommended. During the post-transplant period, a medical consultation is necessary to determine the patient’s medical stability and determine what dental procedures are sensible.

During the stable post-transplant phase, the following actions are indicated:

Consultation with and clearance from the physician to:

Consultation with and clearance from the physician to:

Meticulous oral-self care including twice daily antimicrobial mouth rinses and use of xylitol-containing products

Meticulous oral-self care including twice daily antimicrobial mouth rinses and use of xylitol-containing productsCLIENT EDUCATION TIPS

LEGAL, ETHICAL, AND SAFETY ISSUES

Medical consultation is required to evaluate the client’s medical stability, use of medications, and necessary precautions before invasive dental treatment.

Medical consultation is required to evaluate the client’s medical stability, use of medications, and necessary precautions before invasive dental treatment. Document results from the medical consultation, including medical provider’s recommendations and conversation with the client or caregiver.

Document results from the medical consultation, including medical provider’s recommendations and conversation with the client or caregiver.KEY CONCEPTS

Patients awaiting solid organ transplantation outnumber the actual number of transplants performed each year.

Patients awaiting solid organ transplantation outnumber the actual number of transplants performed each year. The most common pre–solid-organ-transplant patient will be a patient with end-stage renal disease who most likely is receiving dialysis therapy.

The most common pre–solid-organ-transplant patient will be a patient with end-stage renal disease who most likely is receiving dialysis therapy. When assessing a client who is on renal dialysis, do not take blood pressure readings in the dialysis access arm (this could cause the access to become occluded or infected).

When assessing a client who is on renal dialysis, do not take blood pressure readings in the dialysis access arm (this could cause the access to become occluded or infected). Avoid treatment after dialysis treatment on the same day, because of coagulation complications associated with the use of heparin (blood anticoagulant therapy) administered during dialysis.

Avoid treatment after dialysis treatment on the same day, because of coagulation complications associated with the use of heparin (blood anticoagulant therapy) administered during dialysis. When treating patients on dialysis, consult with and obtain clearance from the nephrologist to confirm that the patient is medically stable to receive dental treatment (may need to delay treatment if patient received heparin [blood anticoagulant therapy] during peritoneal dialysis treatment within the previous 24-hour period) and to determine if prophylactic antibiotic premedication is indicated to prevent either infection of the dialysis access or infective endocarditis.

When treating patients on dialysis, consult with and obtain clearance from the nephrologist to confirm that the patient is medically stable to receive dental treatment (may need to delay treatment if patient received heparin [blood anticoagulant therapy] during peritoneal dialysis treatment within the previous 24-hour period) and to determine if prophylactic antibiotic premedication is indicated to prevent either infection of the dialysis access or infective endocarditis. Among solid organ transplant centers, there is no one standard pretransplant or post-transplant dental protocol.

Among solid organ transplant centers, there is no one standard pretransplant or post-transplant dental protocol. The need for antibiotic prophylaxis for invasive dental procedures in clients who have undergone solid organ transplant is controversial. Although surveys of transplant providers demonstrate opposing views, the majority of providers do recommend antibiotic prophylaxis for invasive dental procedures. Neither the American Heart Association nor K/DOQI addresses this issue. Therefore organ transplant recipients should be individually evaluated for infectious risk, and medical and dental consultation is necessary.

The need for antibiotic prophylaxis for invasive dental procedures in clients who have undergone solid organ transplant is controversial. Although surveys of transplant providers demonstrate opposing views, the majority of providers do recommend antibiotic prophylaxis for invasive dental procedures. Neither the American Heart Association nor K/DOQI addresses this issue. Therefore organ transplant recipients should be individually evaluated for infectious risk, and medical and dental consultation is necessary. The Kidney Disease Outcomes Quality Initiative (K/DOQI) is a globally acknowledged set of guidelines addressing all stages and aspects of renal disease.

The Kidney Disease Outcomes Quality Initiative (K/DOQI) is a globally acknowledged set of guidelines addressing all stages and aspects of renal disease. In persons with mineral and bone disorder, calcium deposits may be visible on panoramic radiographs as calcifications in the carotid arteries, on periapical radiographs as narrowing of the pulp chamber or abnormal calcifications in soft tissues, or as a radiolucent osseous lesion (also known as a brown tumor). Other radiographic manifestations include loss of lamina dura, loss of trabecular pattern, and bone density changes.

In persons with mineral and bone disorder, calcium deposits may be visible on panoramic radiographs as calcifications in the carotid arteries, on periapical radiographs as narrowing of the pulp chamber or abnormal calcifications in soft tissues, or as a radiolucent osseous lesion (also known as a brown tumor). Other radiographic manifestations include loss of lamina dura, loss of trabecular pattern, and bone density changes.CRITICAL THINKING EXERCISES

ACTIVITY 1

Client: Mrs. T. is a 60-year-old retired public school teacher with end-stage renal disease. She desires a less-restrictive lifestyle without dialysis.

Chief Compliant: “I would like to get on the waiting list for a new kidney, but I’ve been told by my dialysis center that I need a dental clearance first.”

Social History: Mrs. T. has been on dialysis for 3 years. She has a low energy level but does have a daughter and grandchildren who live next door and help her when necessary.

Dental History: Mrs. T. has a history of regular dental visits before she started dialysis but has not had a professional oral debridement since she started dialysis 3 years ago. Oral assessment findings reveal heavy supragingival and subgingival oral biofilm and dental calculus deposits generalized throughout the mouth, spontaneous gingival bleeding, and a uremic mouth odor. Dental examination does not reveal active carious lesions.

Oral Self-Care Assessment: Poor oral hygiene, xerostomia, use of a manual toothbrush once daily with no interdental cleaning.

Supplemental Notes: Mrs. T. wants to be listed on the transplant waiting list.

ACTIVITY 2: LEARN EMPATHY, NOT SYMPATHY

This activity asks participants to experience life through the eyes of a dialysis patient and provides insight into the lives of patients with end-stage organ disease.

ACTIVITY 3: CRITICAL THINKING EXERCISE FOR CLIENT WHO HAS UNDERGONE SOLID ORGAN TRANSPLANT

Client: Mr. Y. is a 30-year-old accountant. He takes cyclosporine daily.

Chief Compliant: “My gums are swollen.”

Social History: Mr. Y. received an organ transplant 1 year ago. He has not had a dental visit since before his surgery.

Dental History: Mr. Y. has a history of regular dental visits before he started dialysis but has not had a professional oral debridement since before his surgery 1 year ago. Oral assessment findings reveal gross deposits of moderate supragingival and subgingival oral biofilm and dental calculus. Dental examination reveals no active carious lesions; however, oral radiographs reveal unusual radiopaque lesions in the soft-tissue areas.

Oral Self-Care Behavior Assessment: Fair oral hygiene, xerostomia, use of a manual toothbrush once daily.

Supplemental Notes: Mr. Y. is an active participant in his medical care but does not quite understand how his oral health can affect other parts of his body.

1. Guggenheimer J., Egthesad B., Stock D.J. Dental management of the (solid) organ transplant recipient. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 2003;95:383.

2. National Kidney Foundation: NKF-KDOQI guidelines. Available at: www.kidney.org/professionals/kdoqi/guidelines.cfm. Accessed December 20, 2007.

3. National Kidney Foundation: How your kidneys work. Available at: www.kidney.org/kidneydisease/howkidneyswrk.cfm#where. Accessed March 11, 2008.

4. Kuma S: A double-edged sword in the patient with chronic kidney disease. Available at: http://www.medscape.com/viewarticle/465461. Accessed October 9, 2008.

5. Antonelli J.R., Hottel T.L. Oral manifestations of renal osteodystrophy: case report and review of the literature. Spec Care Dent. 2003;23:28.

6. Takeuchi Y., Ishikawa H., Inada M., et al. Study of oral microflora in patients with renal disease. Nephrology (Carlton). 2007;12:182.

7. Lucas V.S., Roberts G.J. Uremia in a protective role in caries risk. Pediatr Nephrol. 2005:20.

8. Lucas V.S., Roberts G.J. Oro-dental health in children with chronic renal failure and after renal transplantation: a clinical review. Pediatr Nephrol. 2005;20:1388.

9. Kshirsagar A.V., Moss K.L., Elter J.R., et al. Periodontal disease is associated with renal insufficiency in the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities (ARIC) study. Am J Kidney Dis. 2005;45:650.

10. Ellis S., Seymour R.A., Taylor J.J., Thomason J.M. Prevalence of gingival overgrowth in transplant patients immunosuppressed with tacrolimus. J Clin Periodontol. 2004;31:126.

11. Danovitch G.M. Handbook of kidney transplantation. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams and Wilkins; 2001.

Visit the  website at http://evolve.elsevier.com/Darby/Hygiene for competency forms, suggested readings, glossary, and related websites..

website at http://evolve.elsevier.com/Darby/Hygiene for competency forms, suggested readings, glossary, and related websites..