CHAPTER 52 Eating Disorders

Differentiate among anorexia nervosa, bulimia nervosa, and eating disorder not otherwise specified, based on systemic, psychologic, and physical characteristics and epidemiology.

Differentiate among anorexia nervosa, bulimia nervosa, and eating disorder not otherwise specified, based on systemic, psychologic, and physical characteristics and epidemiology. Explain the value of the dental hygienist’s role in identification and referral of clients with eating disorders, as well in interprofessional collaboration for client-centered care.

Explain the value of the dental hygienist’s role in identification and referral of clients with eating disorders, as well in interprofessional collaboration for client-centered care. Assess clients’ oral signs and symptoms of anorexia or bulimia nervosa, and engage client in dialogue of discovery or disclosure.

Assess clients’ oral signs and symptoms of anorexia or bulimia nervosa, and engage client in dialogue of discovery or disclosure.BACKGROUND

Dental hygienists as health professionals will knowingly and unknowingly encounter clients who have eating disorders. An eating disorder is a mental illness which often coexists with other illnesses. Although mental health counseling and treatment of the illness and its comorbid conditions is outside the scope of dental hygiene practice, the dental hygienist as a primary healthcare provider ethically is responsible to help the client access interventions and care. This help may be in the form of helping the client seek initial contact with experts, or helping the client with harm reduction by making a custom tray clients can wear over their teeth while orally purging. Eating disorders are a challenge for all: the client, the client’s family and friends, healthcare professionals, and society in general. The challenge arises from the very nature of the illness, from its initial insidious onset to its secretive behavior and manipulation of the person’s way of thinking about his or her body, eating habits, and perception of personal health and wellness. When a person is diagnosed with an eating disorder, the person can be so deeply engaged in the thinking associated with the disorder and resultant body and mental dysfunction that the restructuring of thought to healthy habits and mindsets is very difficult to manage, often requiring many years for recovery.

The American Psychiatric Association (APA) classifies eating disorders as mental disorders.1 There are two clearly defined eating disorders—anorexia nervosa and bulimia nervosa—as well a third diagnosis of “eating disorder not otherwise specified” (EDO-NOS). EDO-NOS is used as a diagnostic category if the person manifests criteria not specific to either anorexia or bulimia but has clinically significant disturbances in eating. As the knowledge base increases the understanding of disordered thinking about body, weight, and eating relationships, the need for further diagnoses becomes evident, such that clusters of eating disturbances are being identified to help with diagnosis of an eating disorder. Of the many clusters of EDO-NOS, one that is receiving attention has been categorized as binge-eating disorder. Although this chapter focuses on anorexia nervosa, bulimia nervosa, and binge-eating disorder, the dental hygienist should be aware of other eating disturbances that fall under the EDO-NOS umbrella, for example, compulsive overeating, compulsive overexercising, night-eating syndrome, and sleep eating disorder (SED-NOS).2 Anorexia nervosa and bulimia nervosa are discussed in relation to the dental hygiene care plan, as these two are associated with significant oral sequelae.

Eating disorders are illnesses of thinking that result in physiologic, biologic, physical, mental, emotional, and social deterioration of the person.1 Death is a very real outcome of an eating disorder. The mortality rate for anorexia nervosa is as high as 10% to 20%, much higher than any other mental illness, even depression.2 The body system of a person who is nutritionally starved begins to shut down, electrolyte imbalances occur, and the person develops psychologic distress, with attempted suicide a real possibility; all these can and do result in death. When a dental hygienist suspects a client has an eating disorder, the hygienist must address it and become a person in the client’s life who enables recovery from the illness and not one who hesitates and vacillates, saying “I should have” or “I would have, but…,” as illustrated in Scenario 52-1. The time to take action is now. The longer the eating disorder grips the client, the more difficulty he or she will have in fighting the illness and repossessing his or her life.

SCENARIO 52-1

SCENARIO 52-1

When Phillip, the dental receptionist, comes into Sandra Hamm’s dental hygiene room, he says, “Have you noticed how skinny Linda Pham is getting?”

“Yes, she had a very fit body last time she was here a little over 2 months ago when she had her braces removed,” replies Sandra. “I did notice her weight loss when I walked by the reception area. It looks like she has lost at least 20 pounds. She’s a waif of a figure now.” Sandra makes a mental note to ask Linda about her weight loss during her dental hygiene appointment. Sandra suspects a possible eating disorder. She has known Linda for most of Linda’s 20 years, but Sandra feels uncomfortable asking her. She wonders how to go about asking someone “Are you anorexic?”

Throughout the appointment it becomes evident to Sandra that Linda is not behaving like herself. She is evasive when answering questions about her health history. By the end of the appointment, Sandra hasn’t asked Linda about the weight loss and decides that perhaps it is none of her business.

A few months go by, and Linda’s father comes in for his dental hygiene appointment. He discloses to Sandra that Linda has been hospitalized for anorexia nervosa. He apologies for his own oral health state, saying, “All our attention has been centered on Linda. She nearly died from malnutrition. We’ve been busy with doctor appointments, family therapy sessions, group support, and just plain occupied with strategizing around providing her support as she recovers from this illness.”

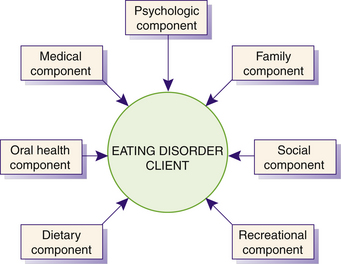

The dental hygienist can serve such clients as their advocate. For example, dental hygienists can enable access to needed healthcare; facilitate honest disclosure of the disorder and behaviors associated with it; promote healthy thinking and being; and help the client obtain and maintain good oral and general health. Because eating disorders are complex in terms of both cause and treatment, successful care requires a client-centered collaborative practice approach3 involving many health professionals such as specially trained psychologists for individual and family therapy; psychiatrists and social workers; physicians and nurses with experience in eating disorders; nutritionists and exercise therapists for education and reorientation of eating and exercise habits; and the oral health team for support and treatment of oral manifestations of the illnesses (Figure 52-1). Collaboration with other health professionals as part of the client’s healthcare team is vital. For example, the dental hygienist informs the healthcare team of oral conditions; manages oral health risk and harm reduction; reinforces consistent messages regarding recovery from the illness; and ensures a team approach to care. Scenario 52-2 provides an example of the dental hygienist’s role in helping a client overcome an eating disorder.

SCENARIO 52-2

SCENARIO 52-2

“Jennifer, are you ready to have your parents come in the room?” asks Dr. Beckham, Jennifer’s psychiatrist.

“Oh, whatever. Let’s just get this over with! I’m fine. You all are just overreacting. They’re going to freak with your diagnosis of bulimia, and then I’ll never be able to live again. I hate this! I wish everyone would just leave me alone. I’m 17 years old!” shouts Jennifer back to Dr. Beckham and her healthcare team, Sally Friesen (social worker), Marlee Ford (nutritionist), and Darcy MacAlroy (nurse and case manager).

After team meetings with Jennifer Black over several appointments, Jennifer has been informed that her behavior is consistent with that of a person with bulimia, a mental illness. Darcy invites Mr. and Mrs. Black into the conference room. Jennifer doesn’t even look at them; rather, she noticeably sits with her body in a “closed” position. Dr. Beckham welcomes them and informs them that Jennifer is ready to discuss some behaviors that explain why they brought her to the eating disorder clinic program in the first place a couple of weeks ago.

Jennifer begins to cry. “Mom, Dad, I’m so ashamed. I can barely say it, but for the last 7 months I’ve forced myself to throw up five times a day. At first I only did it once a day, and then I just kept doing. Dr. Beckham says I have bulimia. Inside I know I do and it is so freaking embarrassing because I think it’s disgusting. I can’t seem to stop. I’m ready for help. I can’t stop doing this on my own.”

Mrs. Black, with tears streaming down her face, replies, “Honey, we’re all about helping you fight this illness. We’ll fight it with you. You can count on us. Admitting you have bulimia is a great first step.”

About 2 months ago Mrs. Black began suspecting that Jennifer was developing an eating disorder. Mrs. Black noticed food missing from their house; Jennifer was excusing herself from the supper table and disappearing into the downstairs washroom. Mrs. Black gently asked Jennifer if she was experiencing any issues with eating, but Jennifer denied any problem. She did mention her teeth were sensitive and asked to see Claudette, her dental hygienist. In the end, Mrs. and Mr. Black persuaded Jennifer to see Dr. Beckham, which she did, but she was initially very reluctant and dismissive of the idea. Her appointment with Claudette is booked for next week.

Persons with an eating disorder such as bulimia nervosa are likely to eventually seek oral care because of the changing appearance of teeth or complaints of oral or dental discomfort. Therefore the dental hygienist may be the first health professional to identify oral and physical manifestations characteristic of these disorders. Keep in mind that individuals with eating disorders are reluctant to acknowledge the gravity of their obsession with food and weight, and they carefully protect the secret of their obsessive, compulsive behavior. The dental hygienist then becomes essential in the initial recognition and referral of the client to the medical and psychologic treatment system, as well as integral to the support of the oral environment.

Eating disorders are comorbid with other mental disorders, such as depression, anxiety, compulsive disorder, substance abuse, and self-injurious behavior.1,4,5 Scenario 52-3 describes a person experiencing both anorexia nervosa and self-injurious behavior. It provides an example dental hygienist’s dialogue during a client interview. The comorbid conditions along with the eating disorder result in multiple effects on the person’s psyche, mental state, emotions, social interactions, and life in general. The dental hygienist must be cognizant of the comorbidity of eating disorders with other illnesses, as the client will greatly benefit from help available to treat and manage the illnesses that often coexist with eating disorders. Many of these illnesses also have oral manifestations or adversely influence oral health. For example, antidepressants can result in dry mouth, which then results in increased risk for dental caries, periodontal disease, and opportunistic oral infections and adversely affects taste acuity and pleasure in eating. If the client has a dry mouth as a result of antidepressant use, then the client will need to lessen that effect by replenishing the wetness in the mouth, thereby improving the eating experience. Having a functional mouth is part of the recovery from an eating disorder. Dental hygienists need to be aware of the role they play in encouraging the client to comply with healthcare professional advice and care.

SCENARIO 52-3

SCENARIO 52-3

“I noticed you have several puncture marks on you’re arm, Melanie. How did you get those?” asked Susan Little, the dental hygienist, during Melanie’s appointment.

“Well, I hurt myself,” replied Melanie.

“You hurt yourself? Looks like you fell into a bush,” said Susan.

“No, I hurt myself.” Melanie simply stated, “I hurt myself. I stab myself.”

Susan thought a moment, knowing that self-harm behavior is comorbid with many other illnesses and that eating disorders are among them. “Melanie, are you having issues with your body, with eating?” gently asked Susan.

“I am so fat! I hate my body! I wish I would just disappear,” cried Melanie; she curled herself into a tight ball on the dental hygiene chair.

Susan thought for a moment and then said to Melanie, “I see the marks on your arm and I hear you express dissatisfaction with your body. It makes me think you might have an eating disorder. I would like you to see a colleague of mine. He is a nurse who specializes in eating disorders. Jon is a really good person to talk with, in general, and then if you have more to talk about, he’ll be terrific. Very nonjudgmental. It really concerns me that you are harming yourself. It isn’t safe for you. I wonder if you would see Jon for me.”

The sensitivity associated with suspecting a client has an eating disorder or treating a client who admits to having one can be challenging for the dental hygienist who has one as well. The nature of the disorder is secretive; it induces shame and guilt. Therefore it is difficult for individuals to discuss the problem openly. The ethical responsibility of the dental hygienist is to overcome personal discomfort, depersonalize the discussion with the client, and proceed to provide client care of the highest quality.

A common belief is that people with eating disorders are “doing this to themselves.” The dental hygienist must be mindful of the scientific evidence that eating disorders are a biologic and psychologic illness (Box 52-1). Affected individuals are not willfully bringing the illness on themselves.2 What may start off as a diet for the person at risk for developing an eating disorder becomes a trigger for the onset of the illness. For example, evidence is mounting that in persons with anorexia nervosa the brain responds differently to food than in persons who do not have the illness. In bulimia nervosa the body’s biologic systems governing appetite (homeostatic) and eating (hedonic) are in disharmony.

BOX 52-1 Eating Disorders Are Illnesses

Data from National Eating Disorder Association: Eating disorders information index. Available at: www.myneda.org/p.asp?webpage_id=294. Accessed January 2008.

Eating disorders are illnesses with a biologic basis modified and influenced by emotional and cultural factors. The stigma associated with eating disorders has long kept individuals silent, has inhibited funding for crucial research, and has created barriers to treatment. Because of insufficient information, the public and professionals fail to recognize the dangerous consequences of eating disorders. Although eating disorders are serious, potentially life-threatening illnesses, there is help available and recovery is possible.

ANOREXIA NERVOSA

Anorexia nervosa is a mental illness affecting adolescent girls and young women, although boys and men are not immune to it and it is seen in adults of both genders.1,4,5 Something seems to trigger the illness, such as a comment regarding weight, realization that friends are thinner, or attending a new school. Some trigger situation for the person susceptible to the illness awakens the cascading thinking and behaviors that begin the course of the illness. Such trigger situations are extremely variable.5 Anorexia nervosa is the least common eating disorder, but it has a high profile in society because of publicity related to many public figures who have either died as a result of the illness or have made public their diagnosis. The term anorexia is a misnomer, as it literally means “loss of appetite,” whereas the client with anorexia nervosa suppresses and denies sensation of hunger. It is suspected some people have a brief episode of the disorder and recover on their own, but people in whom the course of illness is severe will need help to recover from it. The body of evidence regarding anorexia nervosa is predominately based on individuals requiring hospitalization; therefore the many suspected subclinical or unreported cases are not part of that evidence.5

Diagnosis

There are four key diagnostic criteria for anorexia nervosa, with two specified types: restricting type or binge-eating and purging type (Box 52-2). During an anorexia nervosa episode, persons with the restricting type achieve weight loss through dieting, fasting, or excessive exercise. By comparison, persons with the binge-eating and purging type may engage in purging behaviors such as self-induced vomiting, misuse of laxatives, and diuretics or enemas, as well as binge eating. These behaviors are seen at least weekly during an anorectic episode. The stereotypic image of the extremely emaciated person may or may not be accurate in clients with anorexia nervosa. Body weight less than 85% below normal for the person’s age and height does not ensure an emaciated appearance. Distortion in body image may be demonstrated by clients with anorexia nervosa through verbalization of how they feel or look fat when they are obviously thin or underweight.

BOX 52-2 DSM-IV-TR Diagnostic Criteria for 307.1, Anorexia Nervosa

Reprinted with permission from the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Text Revision, Fourth Edition (Copyright 2000), American Psychiatric Association.

Epidemiology

The epidemiology of anorexia nervosa is being investigated and reported by credible bodies1,4,5 (Table 52-1). Anorexia nervosa appears to be a mental illness common to industrialized and affluent countries that place value on thinness. A cultural trend is being considered as possible, although when persons immigrate to industrialized countries such as the United States or Canada, there is an appearance of anorexia nervosa attributed to assimilation into a culture supporting the thin-body ideal. The lifetime prevalence of strictly defined anorexia nervosa among females is 0.5% to 1%. Approximately one tenth of those affected are male; therefore it is viewed as a female-associated illness. The onset of the illness primarily occurs in prepuberty, adolescence, and young adulthood. It is a relatively rare eating disorder but has the highest morbidity rate of any psychiatric diagnosis and has a poor response rate and protracted course of illness. The incidence appears to be rising.

TABLE 52-1 Epidemiology of Anorexia, Bulimia, and Binge Eating

| Anorexia Nervosa | Bulimia Nervosa | Binge-Eating Disorder (BED) |

|---|---|---|

Adapted with permission from the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Text Revision, Fourth Edition (Copyright 2000), American Psychiatric Association.

The course of anorexia nervosa is variable but appears marked by chronicity and relapse (Box 52-3). The cardiovascular system, hematopoietic system, fluid and electrolyte balance, gastrointestinal system, endocrine system, and bone become medically compromised for persons with anorexia nervosa. In addition, their psychiatric and mental well-being becomes upset. Table 52-2 outlines medical problems associated with anorexia nervosa. See Tables 52-3 and 52-4, respectively, for primary symptoms and warning signs of anorexia nervosa. In addition to the medical problems, persons with anorexia nervosa have psychologic challenges such as major depression and anxiety disorders, substance abuse, self-injurious behavior, and restricted affect and capacity for insight. Scenario 52-4 shows the role the dental hygienist may be asked to play with respect to an eating disorder and a comorbid condition, in this case substance abuse. The dental hygienist’s holistic approach to oral health recognizes the oral health–systemic health link and understands that upset in one body system affects whole-body wellness. Hopeful outcomes are associated with early diagnosis and intervention, but this mental illness is very challenging to the person and the healthcare team. Persons with anorexia nervosa commonly have a migration to bulimia nervosa.

BOX 52-3 Course and Outcome of Anorexia Nervosa

Reprinted with permission from the Clinical Manual of Eating Disorders (Copyright 2007), American Psychiatric Association.

TABLE 52-2 Examples of Medical and Health Consequences of Anorexia and Bulimia

| Anorexia Nervosa | Bulimia Nervosa |

|---|---|

Adapted with permission from the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Text Revision, Fourth Edition (Copyright 2000), American Psychiatric Association.

TABLE 52-3 Primary Symptoms of Anorexia, Bulimia, and Binge-Eating Disorder

Adapted with permission from the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Text Revision, Fourth Edition (Copyright 2000), American Psychiatric Association.

TABLE 52-4 Warning Signs and Behaviors of Anorexia Nervosa, Bulimia Nervosa, and Binge-Eating Disorder

Reprinted with permission from the National Eating Disorders Association. For more information, go to www.NationalEatingDisorders.org.

SCENARIO 52-4

SCENARIO 52-4

“Hi, Lynne. Can I have a moment with you before you see Ben for his dental hygiene appointment? We just celebrated his fifteenth birthday,” stated Mrs. Friesen, Ben’s mother. “I need your help. I suspect Ben has an eating disorder. He’s lost a lot of weight in the last few months, he exercises every night at home even though he plays high school volleyball, he swims with the community club team, and he’s always out front kicking a soccer ball around. Ben hasn’t said he has a problem, and every time I try to bring it up he gets really upset with me. Lately I’ve noticed him tapping his teeth together. Ben has never done that before. I’m really frightened. I was watching a documentary the other night on TV about teens and street drugs. Tooth tapping is a symptom of that drug ecstasy. The host of the show said sometimes kids will use street drugs like ecstasy and crystal meth to loose weight. When you see him, will you ask him about the tooth tapping? Can you say something to him? The way I look at it, it takes a community to care for our children. I consider you one of the community.”

BULIMIA NERVOSA

People with bulimia nervosa are able to maintain a body weight within a normal range for their body type; however, they are unduly focused on body shape and weight and express a general dissatisfaction with body image.1,4,5 Bulimia literally means “ox hunger” and accurately describes this abnormal craving for food. People with bulimia nervosa may gorge on large quantities of food and then eliminate the consumed food by purging or other means of ridding the body of the calories consumed. Binge foods typically are high in carbohydrate content and caloric value. Vomiting most often follows binge-eating episodes. With 80% to 90% of persons with bulimia nervosa reporting vomiting as the primary method of ridding themselves of the engorged food, the dentition becomes at risk for erosion owing to the acidity of the stomach contents and also for dental caries owing to the consumption of cariogenic foods.

Diagnosis

Bulimia nervosa is characterized by repeated binge eating (eating significantly more food than what would be considered normal amounts and doing so without control over eating) and purging behaviors to offset the binge, such as self-induced vomiting, use of laxatives or diuretics, excessive exercising, fasting, and enemas.1 There are two specific types: purging type and nonpurging type. The difference between the two is how and what the person does to offset the binge. If the individual engages in self-induced vomiting or misuse of laxatives, diuretics, or enemas, the condition is the purging type. If he or she uses another type of inappropriate compensatory behavior to prevent weight gain, such as excessive exercise or fasting, but does not regularly vomit or misuse laxatives, the condition is the nonpurging type. The most common reported means of preventing weight gain is purging by vomiting; 80% to 90% of persons with bulimia nervosa who report for treatment use this means. See Box 52-4 for the DSM-IV-TR diagnostic criteria for bulimia nervosa.

BOX 52-4 DSM-IV-TR Diagnostic Criteria for 307.51, Bulimia Nervosa

Reprinted with permission from the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Text Revision, Fourth Edition (Copyright 2000), American Psychiatric Association.

Epidemiology

Sources on the epidemiology of bulimia nervosa indicate that bulimia nervosa is much more common than anorexia nervosa1,4,5 (see Table 52-1). Estimated rates are 1% to 3% and higher for college-age women. Prevalence is more significantly known in females than in males at a ratio of 10:1. Onset is generally in later teens and young adulthood. High-risk populations are those where weight and appearance are held important to an activity, such as ballet, wrestling, long-distance running, and modeling. It appears industrialized countries support the role of sociocultural factors in the development of bulimia nervosa.

The course and outcome of bulimia nervosa are variable, but the condition tends to be chronic and relapsing. Unlike anorexia nervosa, it does not have a high mortality rate (Box 52-5). Scenario 52-5 illustrates a mother’s response to her son’s relapse with bulimia nervosa and the value she places on his oral health. Based on those persons seeking help, the condition appears to be of long-term duration, with recovery requiring diligence and professional assistance, and at times pharmaceutical interventions such as antidepressants. Because bulimia nervosa is a secretive illness and the affected person can maintain normal body weight, it can go on for a very long time without ever being disclosed or diagnosed.

BOX 52-5 Course and Outcome of Bulimia Nervosa

Reprinted with permission from the Clinical Manual of Eating Disorders (Copyright 2007), American Psychiatric Association.

SCENARIO 52-5

SCENARIO 52-5

Frank’s mother was straightforward and kind when she confronted him with her discovery of his relapse back to bulimia nervosa behaviors. She said, “I found Ziploc bags in your closet today when I was picking up your laundry from your room. Dear, I see you are purging again. Please do it in the toilet rather than in these bags. The dog might find these and eat them, which won’t do him any good. You’ll beat this disorder. Let’s book an appointment with your nurse therapist for tomorrow rather than wait until next week’s scheduled one. Do you think it would be good to see your dental hygienist this week? It’s getting time for another fluoride application, isn’t it?”

Bulimia nervosa has less impact on the body systems than anorexia nervosa, although medical complications are known (see Table 52-2). See Tables 52-3 and 52-4, respectively, for primary symptoms and warning signs of bulimia nervosa. Persons may develop cardiac problems such as arrhythmias, gastrointestinal problems (e.g., gastroesophageal reflux disease), esophagitis, irritable bowel syndrome, and fluid and electrolyte abnormalities. It is rare to develop gastrointestinal abnormalities, although esophageal tears or gastric ruptures can occur and are potentially life-threatening. Bulimia nervosa is associated with anxiety and mood disorders, particularly major depressive disorders, dysthymic disorder, self-injurious behavior, substance abuse, and personality disorders. Because of the repeated vomiting, some will develop painless salivary gland enlargement. Dental erosion of the maxillary front teeth is an outcome resulting in tooth sensitivity. Professional help may be sought by the person because of discomfort with the dentition. Therefore the dental hygienist may be the first health professional to help the person on the recovery journey.

BINGE-EATING DISORDER

Binge-eating disorder is an EDO-NOS.1,4,5 For diagnosis of EDO-NOS the person must have behavior patterns inconsistent with either anorexia or bulimia nervosa, yet with thinking and behaviors regarding food and body image that are not within normal limits. Binge-eating disorder is described as repeated binge eating without compensatory behaviors such as vomiting but with associated shame, guilt, and lack of control. Box 52-6 outlines the criteria of this disorder.

BOX 52-6 DSM-IV-TR Diagnostic Criteria for Binge-Eating Disorder

Data from Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Text Revision, Fourth Edition (Copyright 2000), American Psychiatric Association.

Epidemiology

Obesity is associated with binge-eating disorder. Persons with binge-eating disorder have difficulty sustaining attempted weight loss. The disorder appears to be a chronic one. From those surveyed, the prevalence is 15% to 20%, with females approximately 1.5 times more likely to have binge-eating disorder than males. It is prevalent across ethnicity. The disorder primarily appears in late adolescence and early adulthood and seems to be associated with significant recent weight loss (see Table 52-1).

The course and outcome of binge-eating disorder are not known, given that the diagnosis is unstable (based on limited research). See Tables 52-3 and 52-4, respectively, for primary symptoms and warning signs of binge-eating disorder. Chances for recovery are apparently good for those who receive treatment, with less likelihood of relapse than in patients with anorexia and bulimia nervosa. Obesity is associated with numerous medical problems as well as psychologic ones.

ETIOLOGY OF ANOREXIA NERVOSA AND BULIMIA NERVOSA

Current theories regarding the cause of anorexia and bulimia suggest a complex interrelationship among biologic, genetic, psychodevelopmental, neurochemical, and sociocultural components.4 Comprehensive information in this area is limited4,5; however, evidence from studies on a genetic element suggest a predisposition for an individual to develop an eating disorder.3

The psychodevelopmental components of both disorders are associated with developmental complexities of adolescence, including personality, personal identity and value shaping, maturation of neurotransmitters and hormones regulating emotions and impulsivity, social relationships, family dynamics, and sexuality, as well as the onset of other mental illnesses such as depression and anxiety disorder. It is believed that a psychosocial environment that focuses on thinness for women puts unrealistic pressure on women, and for some this results in a cascade of ill thinking which seems to self-perpetuate to very harmful compulsive behaviors.

EFFECTS OF EATING DISORDERS

The effects of anorexia and bulimia on the general well-being of an individual are significant.1,4,5 Eating disorders have been referred to as the eclipsing of the person’s thinking with the eating disorder thoughts—that is, behind the eating disorder is the person who has been overshadowed by the illness, which has literally possessed the person’s normal thinking and being.6

Psychosocial Dimension

In the individual with anorexia nervosa, distortion of body image and obsession with food restriction results in self-starvation. Keep in mind that the “self” aspect of “self-starvation” is an illness in thinking and not truly a “self” guidance. Characteristically the appearance of the illness is control over hunger and body as a psychologic coping mechanism gone awry. Clients with anorexia nervosa report this control of food and perfectionist behavior brings feelings of being more competent and in control of life.

In bulimia nervosa, low self-esteem and subsequent feelings of inadequacy are reinforced by the guilt and embarrassment associated with binge and purge behavior. Ironically, the behavior itself becomes self-reinforcing because achievement and maintenance of low weight are perceived as bringing increased attractiveness and more friends; hence the eclipsing analogy. Scenario 52-6 illustrates a person’s feelings about the illness. Persons with bulimia nervosa do not experience the distortion of body image or rigidity of thought characteristic of anorexia nervosa, but they do obsess on body image. They may appear quite successful in the management of life. Affective expression may appear gregarious to the casual observer; however, underlying the facade is a flattened affect resulting from the associated anxiety, guilt, and dysphoria.

SCENARIO 52-6

SCENARIO 52-6

“When I was 21 I discovered by chance I could throw up all I had eaten and I wouldn’t gain weight,” said Amanda, a 23-year-old client of Janet, a dental hygienist. Amanda added, “I was an active university student with good friends, okay grades, and this ever-present worry about weight gain.”

Janet asked, “Amanda, do you still throw up? Your teeth are showing very slight erosion. Do they hurt you? Are they sensitive? Sometimes a person who vomits regularly develops enamel erosion. I’m just seeing some slight evidence of this on your teeth.”

Amanda replied, “Well, this is so embarrassing, I do feel, oh what’s the word—ashamed, mortified that I even got into this, but I did, and to answer your question, not for awhile, and when I do it’s just when I feel too full. I’m better about not eating until I feel too full.”

Janet nodded and said, “I’m glad you told me this. It is important to know for your oral health. Let’s work on a plan. Have you sought help for this behavior?”

Impaired psychologic development and concomitant distortion of attitudes in the client with eating disorders provide the foundation for continued dysfunction and progression of the disorder. Persons with eating disorders rarely seek professional assistance on their own and may resist recommendations and offers of help from family members and friends. Those with bulimia nervosa may eventually seek help owing to tooth sensitivity or a change in the appearance of their teeth.

Physiologic Responses

Many body systems are at risk for disruption as a result of the behaviors associated with an eating disorder. In anorexia nervosa, restricted food intake and resulting undernutrition impair the individual’s overall functioning and health. A common physiologic effect of anorexia nervosa behavior is hormonal abnormalities. In females, prolonged decrease in estrogen along with decreased body fat may contribute to amenorrhea and decreased bone density (osteoporosis). In males, decreased testosterone levels may result in impotence and decreased libido. Cardiovascular, gastrointestinal, renal, and hematologic systems may be compromised in clients with anorexia nervosa. Vital statistics in the client will likely reveal low pulse rates, decreased blood pressure, and reduced left ventricular output. The client may not openly complain about physiologic symptoms such as constipation; however, a comprehensive health history may identify abnormal function such as this gastrointestinal disturbance. A person with pale skin or general fatigue may be experiencing hematologic changes and electrolyte imbalances. Conducting a health history is about establishing normal from abnormal and then following through to improve the diagnosis and resulting care.

The repeated binge and purge behavior in the client with bulimia nervosa may result in dangerous complications, which when left untreated can become life-threatening. Excessive vomiting and diuretic and laxative abuse lead to dehydration and electrolyte imbalance. Loss of potassium is a particular threat because the resulting hypokalemia and metabolic alkalosis may result in cardiac or renal failure. Ipecac syrup use to induce vomiting after binge periods is particularly dangerous. Ipecac syrup contains emetine, which can destroy fibers of the heart muscle. Chronic ipecac ingestion and absorption can lead to fatal myocardial dysfunction. In addition, repeated binge eating and vomiting can cause gastric dilation, esophagitis, esophageal tears, or rupture. Although not common, these are life-threatening.

Other General Physical Findings

As an eating disorder progresses, general physical appearances become evident, based on the disorder. The dental hygienist must be aware to look for these signs during the assessment phase. Two common physical findings for persons with anorexia nervosa in more developed stages of the disorder are lanugo and “feeling cold.” Lanugo is a fine downy hair usually found on the lower half of the face and upper body. Dry skin and hair, as well as decreased scalp hair, are predictable findings as the eating disorder progresses. The client might even report losing hair or that she or he no longer brushes the hair because it is “falling out.” Hypothermia and increased sensitivity to cold may be evidenced by wearing inappropriately warm clothing when environmental temperatures are moderate. The dental hygienist needs to be aware of these presentations and gently engage the client in discussion regarding them.

The dental hygienist may suspect a client is engaging in oral purging if they notice callused knuckles. Persons who orally purge using their fingers may have callused knuckles from the repetitive friction of the teeth riding over the finger during the digital stimulation to induce vomiting. Though it may be common to use one’s own fingers to create the urge to vomit, other objects are used as well. These, along with fingers, can traumatize the palate and other soft tissues of the mouth. Damage done depends on the force used when the vomit reaction is manipulated. Therefore the dental hygienist during the intraoral examination needs to look for lesions and bruises, as they may be cues that a person is orally purging.

EATING DISORDER TREATMENT: INTERPROFESSIONAL COLLABORATION

The treatment involved for a person with an eating disorder involves many health professionals and interventions. Practice guidelines for eating disorder treatment include the following3:

Nutritional treatment planned with the client and if applicable the client’s family. Dietitians offer expert recommendations. The nutritional treatment is aimed at weight restoration and a normal balanced diet. With restoration of weight, the mind is better able to respond to the cognitive therapy to follow; a starved or nutritionally deprived brain does not function optimally.

Nutritional treatment planned with the client and if applicable the client’s family. Dietitians offer expert recommendations. The nutritional treatment is aimed at weight restoration and a normal balanced diet. With restoration of weight, the mind is better able to respond to the cognitive therapy to follow; a starved or nutritionally deprived brain does not function optimally. Psychotherapy such as cognitive behavioral therapy, interpersonal psychotherapy, group psychotherapy, and family therapy is initiated at a time when the eating disorder team and client are ready to engage in it.

Psychotherapy such as cognitive behavioral therapy, interpersonal psychotherapy, group psychotherapy, and family therapy is initiated at a time when the eating disorder team and client are ready to engage in it. Psychopharmacologic treatment is a possibility and determined by the team and client. Medications used are antidepressants and antianxiolytics. Little evidence supports medication use as the single treatment for eating disorders; however, evidence does support medication use for the comorbid conditions associated with eating disorders. Such medications have dry mouth as a potential side effect.

Psychopharmacologic treatment is a possibility and determined by the team and client. Medications used are antidepressants and antianxiolytics. Little evidence supports medication use as the single treatment for eating disorders; however, evidence does support medication use for the comorbid conditions associated with eating disorders. Such medications have dry mouth as a potential side effect. Inpatient, outpatient, day program, and hospitalization treatment settings are determined based on the severity and client responsiveness.

Inpatient, outpatient, day program, and hospitalization treatment settings are determined based on the severity and client responsiveness.Intraoral and Extraoral Findings

Intraoral and extraoral manifestations of eating disorders, particularly bulimia and the binge and purge subtype of anorexia, occur but are dependent on the duration of the illness, severity of behaviors, diet, and oral hygiene behaviors7,8 (Table 52-5). The client with an eating disorder may exhibit one or more of these manifestations, but few individuals exhibit all of them; some may experience none of them. Many of these signs are seen only once the person has had the disorder for some time. Therefore early identification and prompt intervention are challenging, and more likely the dental hygienist seeing the client at this stage will employ tertiary prevention interventions. After conducting a comprehensive health history and oral assessment in a nonjudgmental, respectful environment, the dental hygienist acts to promote prompt intervention to lessen the disorder’s effect on the oral cavity and on the person’s overall health and wellness.

TABLE 52-5 Potential Effect of Eating Disorders on the Oral and Perioral Tissues

| Effect on Oral and Perioral Tissues | Anorexia Nervosa | Bulimia Nervosa and Binge-Purge Anorexia Nervosa |

|---|---|---|

| Parotid enlargement | Yes | Yes |

| Diminished taste acuity | Yes | Yes |

| Dehydration or xerostomia | Yes | Yes |

| Enamel erosion (perimolysis) | No | Yes |

| Intraoral trauma (e.g., palatal abrasion, palatal hematoma) | No | Yes |

| Increased risk of dental caries | No | Yes |

| Other comorbid disorders (e.g., self-injurious behavior) | Yes | Yes |

| Oral side effects of medications (e.g., antidepressants) | Yes | Yes |

| Oral health–systemic health issues (e.g., esophageal reflux disease, yeast infection) | Yes | Yes |

Parotid Enlargement

Extraorally, parotid enlargement has been observed in both anorexia and bulimia. This enlargement is noninflammatory in nature. It gives the jaw an enlarged appearance that subsides with abstinence from self-induced vomiting. Palpation will reveal the enlargement to be soft and generally painless.

Diminished Taste Acuity

Although not obvious from the intraoral examination, diminished taste acuity has been reported by clients with eating disorders. This alteration in taste sensation is thought to be a result of malnutrition, specifically trace metal deficiency, or hormonal abnormalities. Changes in hormonal levels have been shown to decrease sensations of taste and smell.

Dehydration and Xerostomia

Xerostomia, dry chapped lips, and commissure lesions resembling angular cheilitis may occur if the client is dehydrated from vomiting, diuretic or laxative abuse, or antidepressant medications used to treat eating disorders. It is thought the commissure lesions occur when oral tissues are dehydrated and vomiting is frequent.

Perimolysis or Enamel Erosion

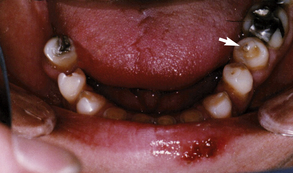

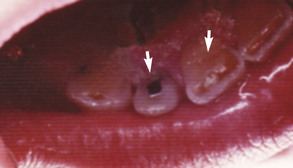

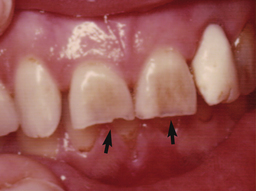

Perimolysis, or enamel erosion, is the most common dental finding in the client who vomits (Figures 52-2 to 52-6). The hydrochloric acid from the stomach is in the vomit. The chemical erosion that results is on the lingual, occlusal, incisal, or facial tooth surfaces. Typically the maxillary teeth are involved, but any tooth that comes in regular contact with the acid is susceptible to erosion. Subsequent mechanical erosion then occurs when the tongue or toothbrush moves against the teeth. Early perimolysis is difficult for practitioners to identify because tooth structure loss usually is subtle. Slight pitting is evident on the incisal surfaces of the anterior teeth, and a cupping appearance may be present on the cusps of the posterior teeth. This dished-out appearance should be differentiated from the typical flattened appearance that occurs from abrasion. As perimolysis progresses, the teeth exhibit a loss of normal anatomic features, such as developmental grooves and pits, and develop a matlike surface with rounded margins. This anatomic loss may become so extensive that complete enamel loss is evident. Loss of lingual and incisal enamel on anterior teeth weakens the tooth structure, making them more susceptible to chipping. Anterior teeth of clients with eating disorders may appear translucent and motheaten, with an open bite. Enamel loss around amalgam restorations results in a raised-island appearance of the amalgam. Teeth without restorations show a significant loss of occlusal contours.

Figure 52-2 Perimolysis on maxillary incisors resulting from habitual vomiting associated with bulimia nervosa.

(Courtesy J. Charbonneau, 2008.)

Figure 52-3 Comparison of loss of vertical height of teeth 11 and 12 versus teeth 21 and 22. Vertical height restored with resin restorations. Height loss was due to regular vomiting of client with bulimia nervosa.

(Courtesy J. Charbonneau, 2008.)

Figure 52-4 Thinning and chipping of incisal third of teeth 11 and 21 in person with bulimia nervosa.

(Courtesy S. Issac, 2008.)

Dentinal Hypersensitivity

Perimolysis may eventually result in dentinal exposure and associated tooth sensitivity. Clients who purge their food may complain of tooth sensitivity; often this is their chief reason for seeking dental care.

Dental Caries

Decreased salivary flow along with disturbed dietary patterns can predispose the client to an increased dental caries rate. Not all studies support the theory that individuals with eating disorders have an increased prevalence of dental caries. Evidence, however, suggests that persons with bulimia nervosa may be prone to caries owing to a high carbohydrate intake, changes in oral pH, decreased saliva quantity and/or quality, and use of antidepressants and/or other medications associated with diminished salivary flow rate. Xerostomia also can result from illicit drug use, coexisting with the eating disorder.

Periodontal Disease

Persons who are nutritionally deprived are at risk for periodontal disease. Thus, clients with an eating disorder may be at risk for periodontal disease. Moreover, the body is a system, and if at a cellular level the nutrients for efficient body function are lacking, then the body is unable to properly maintain itself, not only in the oral cavity, but also in the heart and other body organs. The client who is on antidepressants and/or other medications, including street drugs, may experience dry mouth, which exacerbates dental plaque biofilm growth. Having depression comorbid with an eating disorder may result in apathy toward oral hygiene habits, thus increasing risk of periodontal disease.

Intraoral Trauma

Intraoral trauma may be evident in the client who orally purges or regurgitates the stomach contents. In addition, oral soft tissues may be fragile because of nutritional deficiencies. Findings may include the presence of traumatic lesions such as ulcerations or hematomas on the hard and soft palates, as well as cheek and lip bites.

DENTAL HYGIENE PROCESS OF CARE FOR CLIENTS WITH EATING DISORDERS

A multidisciplinary approach to care may increase the success rate of treatment of the eating disorder. The role of the dental hygienist and the oral healthcare team varies according to the circumstances surrounding the client’s status. For individuals with an eating disorder who have not been medically diagnosed, the dental hygienist may be the health professional who identifies the need for referral to the psychologic and medical support team. A working knowledge of organizations and individuals within the client’s community who specialize in caring for individuals with eating disorders allows the dental hygienist to guide the client to appropriate therapy. This knowledge can be obtained by contacting mental health organizations or eating disorder treatment facilities within the community. These organizations may not be in the immediate geographic locale, but they are generally knowledgeable about available support throughout the area.

Creating a formal referral protocol with eating disorder treatment centers or with medical and psychologic specialists in eating disorders is important for the dental team. Mental health professionals treating eating disorder clients often need oral healthcare professionals to whom they can refer clients who are experiencing oral problems. A liaison between the oral health team and the psychologic and medical team will open the door for comprehensive client care through referrals and collaboration.

Assessment

Assessment of all dental hygiene clients involves collection of data on the client’s comprehensive health history, intraoral and extraoral status, and physical status. In addition, intraoral photographs and study models are helpful in establishing baseline data to be used for subsequent evaluation of enamel erosion and soft-tissue abnormalities. When the clinician observes deviations from normal in client assessment data that suggest an eating disorder, follow-up questioning is necessary to rule out other possible explanations (Box 52-7). Possible causes for the oral manifestations observed are as follows:

Commissure lesions and/or dry chapped lips, a finding typical of an eating disorder, may also be a result of the presence of other illnesses that cause dehydration and/or undernutrition. Usually clients who have been ill and have dehydration sequelae, however, willingly convey this information on questioning.

Commissure lesions and/or dry chapped lips, a finding typical of an eating disorder, may also be a result of the presence of other illnesses that cause dehydration and/or undernutrition. Usually clients who have been ill and have dehydration sequelae, however, willingly convey this information on questioning. Dental erosion, the most common oral finding in bulimia and the binge-purge subtype of anorexia, also has been associated with vomiting as a result of gastric disturbances and other conditions.

Dental erosion, the most common oral finding in bulimia and the binge-purge subtype of anorexia, also has been associated with vomiting as a result of gastric disturbances and other conditions. Intraoral trauma may result from an accident or may be evidence of self-mutilation indicative of psychologic problems other than eating disorders.

Intraoral trauma may result from an accident or may be evidence of self-mutilation indicative of psychologic problems other than eating disorders. Clients with medication-induced xerostomia may rely on sucrose-containing mints or gum to relieve the dryness associated with decreased salivary flow. Commonly these individuals experience an increase in dental caries rate that can easily be identified by examining the health history and questioning the client. For example, asking “Have there been any dietary changes that have increased your exposure to sugar or sugar-containing foods?” or asking “Can you tell me a little about your snacking habits?” provides an opportunity to discuss eating habits in a nonthreatening manner. Follow-up questions related to frequency or patterns of snacking or sugar consumption provide additional information while allowing the clinician to observe the client’s demeanor regarding discussion of food.

Clients with medication-induced xerostomia may rely on sucrose-containing mints or gum to relieve the dryness associated with decreased salivary flow. Commonly these individuals experience an increase in dental caries rate that can easily be identified by examining the health history and questioning the client. For example, asking “Have there been any dietary changes that have increased your exposure to sugar or sugar-containing foods?” or asking “Can you tell me a little about your snacking habits?” provides an opportunity to discuss eating habits in a nonthreatening manner. Follow-up questions related to frequency or patterns of snacking or sugar consumption provide additional information while allowing the clinician to observe the client’s demeanor regarding discussion of food.BOX 52-7 Possible Causes for Oral Findings Commonly Associated with Clients Who Have Eating Disorders

Perimolysis and Erosion

Parotid Enlargement

During assessment of a client with a suspected eating disorder, it is imperative that the dental hygienist gather specific information in a professional, nonjudgmental manner. An assessment tool to consider using is the SCOFF Questionnaire (Box 52-8). Concluding the presence of an eating disorder without adequate assessment is to be avoided. Concluding prematurely that a client has an eating disorder puts the client and clinician in an unnecessary and uncomfortable position.

BOX 52-8 SCOFF Questionnaire∗ for Screening for Eating Disorders

From Morgan JF, Reid F, Lacey JH: The SCOFF questionnaire: assessment of a new screening tool for eating disorders, BMJ 319:1467, 1999.

Setting the threshold at two or more positive answers to all five questions provided 100% sensitivity for anorexia and bulimia, separately and combined (all cases, 95% confidence interval 96.9% to 100%; bulimic cases, 92.6% to 100%; anorectic cases, 94.7% to 100%), with specificity of 87.5% (79.2% to 93.4%) for controls. The false-positive rate of 12.5% is an acceptable tradeoff for very high sensitivity.

Assessment of the client who reports a history of bulimia or anorexia involves several important components. In the client with a diagnosed eating disorder, historical information regarding the course and treatment of the eating disorder, past medical and dental care and treatment interventions, and current status of the oral environment is necessary to provide appropriate client care. This evaluation should provide a clear depiction of the extent to which the eating disorder relates to associated behaviors, current status regarding psychotherapy and/or supportive care, and current physical and oral findings (Table 52-6).

TABLE 52-6 Assessment of Client with a Suspected and/or Previously Diagnosed Eating Disorder

| Component | Assessment Technique |

|---|---|

| Health History | |

| Physical appearance and gait: skin, build, hair, pallor | Observation |

| Vital signs: blood pressure, heart rate, body temperature | Objective measurement |

| Systemic disease: current and past status | Interview, collaborative consultation |

| Systems review (e.g., bowel movements, postural hypertension) | Interview, collaborative consultation |

| Medications: drug names, dosage, duration, purpose | Interview, collaborative consultation |

| Substance abuse: alcohol, nonprescription medications, street drugs | Interview |

| Physical activity: frequency and duration | Interview |

| Dietary habits: cariogenicity of diet, general healthy eating habits | Interview, dietary analysis for dental caries control and general healthy eating habits |

| Oral homecare: routine, products, techniques | Interview, observation |

| Extraoral Assessment | |

| Salivary and lymph glands | Palpation |

| Temporomandibular joint | Palpation, auscultation |

| Skin: color, moisture, facial hair (lanugo), lesions | Observation |

| Perioral structures: commissure lesions, lip integrity, trauma | Observation |

| Hands (knuckles calloused) | Observation |

| Intraoral Assessment | |

| Soft tissue: mucous membranes, palatal tissue, tongue, floor of mouth, throat | Observation and palpation |

| Dental caries and tooth color | Observation, radiographic assessment, manual assessment |

| Tooth wear: presence or absence, location, appearance (motheaten, cupped, thinned, abraded), open bite | Observation, comparative study model |

| Periodontal tissues | Observation, radiographic assessment, manual assessment |

| Oral hygiene | Observation and manual assessment |

Dental Hygiene Diagnosis

Dental hygiene diagnoses can be accomplished using assessment data to determine deficits in the human needs related to dental hygiene care. Actual diagnosis of the eating disorder is not a function of members of the oral health team because this can be determined only through a thorough psychologic evaluation. A client usually manifests several human need deficits arising directly or indirectly from the eating disorder. For example, repeated binge eating of carbohydrates followed by vomiting may result in a deficit related to a biologically sound dentition, as evidenced by enamel erosion (perimolysis) and increased signs of dental caries. Dehydration from vomiting or diuretic or laxative abuse also may result in a deficit relating to the integrity of the skin and mucous membranes, as evidenced by dry chapped lips and commissure lesions similar to angular cheilitis. It is essential that the dental hygienist consider all possible reasons for these deficits so that essential care may follow.

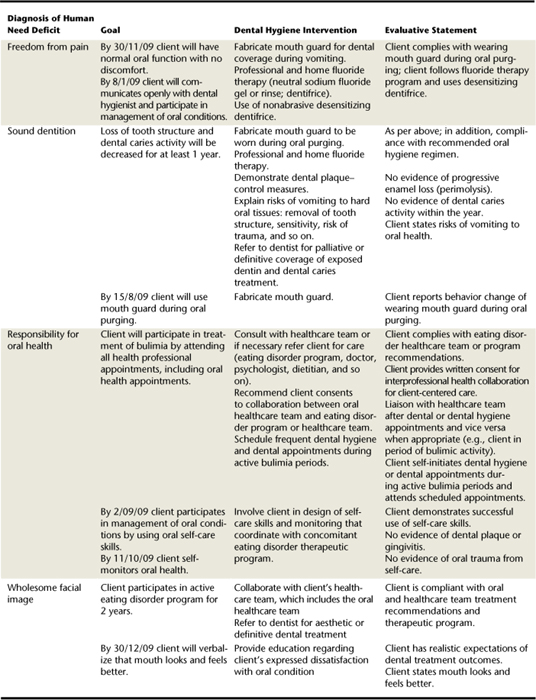

The dental hygiene diagnosis of responsibility for oral health depends on the client’s behaviors associated with the eating disorder. Examples of dental hygiene diagnoses for eating disorders are presented in Table 52-7.

TABLE 52-7 Example of Dental Hygiene Human Needs Diagnoses for Clients with Eating Disorders

| Dental Hygiene Diagnosis Deficit | Due or Related to | As Evidenced by |

|---|---|---|

| Wholesome facial image | Client expression of dissatisfaction with tooth discoloration, loss of tooth structure, open bite, visible dental caries, parotid gland enlargement | |

| Freedom from pain | Oral discomfort from exposed dentin from enamel erosion, dental caries, and dehydration of oral tissues | |

| Integrity of skin and mucous membranes | ||

| Protection from health risks | ||

| Freedom from fear and stress | ||

| Responsibility for oral health |

Planning

The planning phase for the client suspected of having an eating disorder includes the following:

Planning for the client with a previously diagnosed eating disorder includes phases two and three. Members of the oral health team must recognize their limitations in treating clients with these disorders. Oral and dental treatment, either palliative or definitive, may be necessary, but the primary role of the oral health team treating the client with a suspected eating disorder is to refer the client to eating disorder specialists. Such specialists can help clients with the psychologic and medical aspects of their eating disorders. Establishment of a caring, nonjudgmental environment based on mutual trust is necessary to successfully achieve a referral. Attention to the client’s need for freedom from pain through palliative oral care initially is recommended if the client is experiencing discomfort.

Client involvement in setting goals is essential. Goals with the following characteristics must be set:

A sample dental hygiene care plan for a client with an eating disorder is shown in Table 52-8.

Implementation

Professional Confrontation

Once the dental hygiene assessment and diagnoses have been completed, consultation between the dentist and dental hygienist affords both healthcare providers an opportunity to view the data collaboratively. At the initial decision-making juncture, it is determined, based on factors such as psychosocial issues, gender, and ethnocultural sensitivities, whether the dental hygienist or dentist is the best person to confront the client with the objective findings and suspicion of an eating disorder.

No matter who conducts the initial confrontation, a matter-of-fact, nonjudgmental approach must be maintained. Many clinicians are initially uncomfortable with the prospect of confronting a client with a suspected eating disorder and may inadvertently communicate this discomfort nonverbally to the client. To prevent this scenario, the inexperienced clinician benefits from role-playing to practice these types of confrontational situations before an actual experience. Using desensitizing and follow-up questions, such as those suggested in Box 52-9, provides the professional with the opening to apprise the client that observed oral changes are commonly associated with eating disorders.

BOX 52-9 Suggestions for Confronting a Person with a Suspected Eating Disorder

Approach

Dos and Don’ts

The actual confrontation needs to occur in a confidential setting. If dental erosion is the most obvious oral finding, asking questions that eliminate other reasons for erosion allows the clinician to gain valuable information while desensitizing the client to the more direct interview to follow. The confrontational interview should be conducted by asking direct questions while maintaining eye contact. The client’s body language may provide clues about whether the suspicion of an eating disorder is accurate. Few clients openly admit a problem with an eating disorder when questioned. Many have become quite accomplished at denial and can maintain that posture in the dental environment. Most clients with eating disorders, however, experience discomfort at being confronted with objective information they have attempted to hide. The dental hygienist should be aware of nonverbal cues, such as avoidance of eye contact by the client or dropping of the head with a look of embarrassment. These clues are usually an indication the clinician is on the right track with the questions even though the client may verbally respond negatively.

Individuals with eating disorders commonly react to the initial confrontation with various emotions. Two common responses are denial accompanied by tears and outright anger. It is important for the dental hygienist to maintain a professional demeanor during emotional outbursts and to reinforce the observation that the client’s oral, physical, and/or health history findings are consistent with an eating disorder and have no other causative explanation. Some clients are relieved at being discovered and are receptive to suggestions for referral to an eating disorder specialist.

Phase 1: Referral

Suggesting the client make an appointment with an identified eating disorder specialist or treatment center for an evaluation is a less-threatening approach than making a definitive statement that the client has an eating disorder. Many clients are receptive to having the dental hygienist initiate a consultation appointment for them at an eating disorder treatment center (see Box 52-10 for referral guidelines). Others prefer to take the referral information with them to initiate the consultation appointment on their own. Either way, it is important that the client assume personal responsibility for attending a consultation appointment. Follow-up contact is necessary to promote the client’s taking action.

BOX 52-10 Referring a Person with a Suspected Eating Disorder

Refer the Individual

After the confrontation appointment the dental hygienist thoroughly documents the discussion and the decisions regarding referral for evaluation in the client’s permanent dental record. This documentation permits subsequent evaluation and monitoring of the client at future appointments. In addition, it legally documents that the discussion took place and that the oral health team is offering help to the client.

Although some clients may deny they have an eating disorder, over time they may become sufficiently comfortable with the dental hygienist to be receptive to the referral. Persistence on the part of the oral health team when no other explanations can be identified for the findings is crucial because untreated eating disorders can be life-threatening. Ethically, failure to refer a client who has obvious signs of an eating disorder for subsequent psychologic evaluation is neglecting one’s professional responsibility as a healthcare provider.

Phase 2: Establishment of the Dental–Eating Disorder Team Liaison

Once a client with a suspected eating disorder has been confronted and referred for eating disorder counseling, a working relationship between the oral health team and eating disorder therapy team is established and harm reduction and restoration of the oral cavity are initiated as soon as possible.

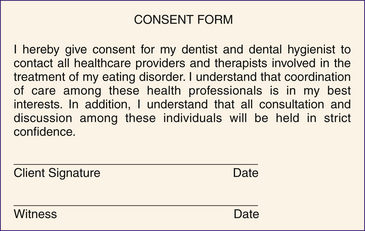

Success of oral healthcare is largely determined by the client’s ability to control behaviors associated with the eating disorder. For this reason, open dialogue among all health providers prevents segmented care planning and permits an integrated approach to client care. Many persons with bulimia nervosa and binge-purge anorexia nervosa have extensive erosion requiring significant dental reconstruction. Lack of coordination among healthcare providers may mean dental failure if the reconstruction is completed before the client has made adequate progress with the eating disorder. Use of a signed release form allows oral health professionals to contact and collaborate with the eating disorder healthcare providers and is recommended when a client with an eating disorder is cared for. A sample release form is shown in Figure 52-7.

Professional collaboration between the oral healthcare team and the eating disorder team permits the oral health team to have a better understanding of the client’s specific psychologic issues and increases the success rate of all dental hygiene and dental interventions. The client is often confronting significant personal issues in psychologic therapy. These may influence the timing and ultimate success of definitive oral care. Without dialogue between the oral health team and the eating disorder team, oral health professionals may make care decisions that fail to address the comprehensive needs of the client. If clients are aware that all health providers are working together in their care, then they are less likely to claim “all is well” in order to have short-term desires met. It is not uncommon for clients with eating disorders to attempt to manipulate healthcare providers during the course of therapy. Dental hygienists and dentists must maintain a collaborative interprofessional approach to healthcare for maximal success with the client with eating disorders.

Management and Support of Oral Tissues

Implementation of individualized education and preventive strategies to support a healthy oral environment is a primary focus of this phase of the dental hygiene process. To meet the client’s human need for conceptualization and understanding, oral health education assists the client in understanding the effect of eating disorder behaviors on oral health and provides self-care strategies to ameliorate or control the associated problems. When providing client education, health-promoting behaviors and management of oral problems as they relate to facial image and freedom from pain are emphasized. Oral health education strategies for the eating disorder client are provided in Box 52-11. These strategies may not be relevant for all clients, but an overview of general concepts is included in each educational program.

BOX 52-11 Oral Health Education for the Client with an Eating Disorder

Oral health education programs should include discussion of the following:

Causes of Oral Manifestations Associated with the Disorder

An overview of the causes of identified problems is necessary before individualized oral hygiene instructions are provided. For example, clients with significant perimolysis as a result of repeated vomiting need to understand that the low pH of stomach contents causes chemical dissolution of tooth enamel. If toothbrushing follows vomiting episodes, mechanical abrasion of the presoftened tooth surfaces is likely. The causes of all oral manifestations need to be adequately explained to clients.

Effect of Eating Disorder Behaviors on the Oral Environment

Client education also includes an overview of systemic physiologic changes typical of the specific eating disorder as it relates to changes in the oral environment. For example, the effects secondary to vomiting and/or diuretic and laxative abuse should be explained as they relate to decreased salivary flow and increased dental caries activity.

Self-starvation and decreased body fat alter endocrine function, which in turn has the potential of causing osteoporosis early in life. It has not been determined to what degree early osteoporosis affects periodontal bone support later in life, but it is important that the client be cognizant of potential changes in bone density as they relate to overall health.

Clients with parotid gland enlargement may express concern about the unaesthetic appearance of the enlargement. If the individual understands that the enlargement usually decreases once the eating disorder behaviors are brought under control, this may increase motivation for following through with psychologic and medical care.

Implementing care for clients with perimolysis is aimed at eliminating pain, maintaining existing tooth structure, and preventing further erosion.7-9 Such care may include one or more of the following: self-applied daily fluoride therapy, mouth guard fabrication to provide tooth coverage during vomiting episodes, desensitization of dentinal hypersensitivity with either professionally applied or over-the-counter agents, avoidance of abrasive prophylaxis, restorative and other appropriate dental care, and education for oral harm reduction and the promotion of oral health.

Effect of Diet on Oral Health

Individuals with eating disorders commonly have unusual eating habits that potentially alter normal oral health. For example, foods containing simple carbohydrates such as cookies, cake, and other sweets are common binge foods for the bulimic. Counseling on the effect of repeated binge eating, frequent sucrose intake, and/or extreme intake of dietary carbonated drinks is provided to the client. Dietary habits in anorexia frequently include excessive intake of diet soda beverages in lieu of food. Continual consumption of low-pH diet beverages in the presence of diminished salivary flow may result in dental erosion and accompanying dentinal hypersensitivity. By adequately assessing eating habits, the dental hygienist can provide appropriate preventive education and treatment. The dental hygienist as part of the eating disorder healthcare team promotes healthy eating and lifestyle; this message never waivers.

Oral Self-Care

Client education is specific to the oral care, but in general, the dental hygiene recommendations are to lessen the acidity, maintain a wet mouth, effectively remove dental plaque biofilm without damage to the tooth and surrounding tissues, remineralize the dentition, protect it and restore it, prevent soft-tissue lesions, and comply with dental and dental hygiene appointments.7-9 Clients need to be informed about the following ways they can reduce the harm to their oral cavity:

Rehydrating the mouth with salivary substitutes, frequent sips of water, ice chips, and sugar-free gum. For the person with an eating disorder such as anorexia nervosa, this may be a formidable expectation during acute phases because the person is supersensitized to calories and the prospect of water retention, hence “feeling fat.”

Rehydrating the mouth with salivary substitutes, frequent sips of water, ice chips, and sugar-free gum. For the person with an eating disorder such as anorexia nervosa, this may be a formidable expectation during acute phases because the person is supersensitized to calories and the prospect of water retention, hence “feeling fat.” No toothbrushing after a purge owing to the mechanical abrasion of the already chemically assaulted tooth structure. Instead, the client should neutralize the acidity in the mouth by promptly rinsing with a neutralizing solution such as sodium bicarbonate (1 tsp in 8 oz of water), slightly alkaline mineral water, or magnesium hydroxide (milk of magnesia) solutions. The toothbrush itself should be soft and used with gentle touch so as to not further destroy enamel crystals.

No toothbrushing after a purge owing to the mechanical abrasion of the already chemically assaulted tooth structure. Instead, the client should neutralize the acidity in the mouth by promptly rinsing with a neutralizing solution such as sodium bicarbonate (1 tsp in 8 oz of water), slightly alkaline mineral water, or magnesium hydroxide (milk of magnesia) solutions. The toothbrush itself should be soft and used with gentle touch so as to not further destroy enamel crystals. Use of desensitizing fluoridated dentifrices to provide additional benefit for exposed dentin from erosion.

Use of desensitizing fluoridated dentifrices to provide additional benefit for exposed dentin from erosion. Employing a home fluoride therapy regimen in addition to professional fluoride applications to remineralize fragile dentition. Daily use of 1.1% neutral sodium fluoride gel, administered either with a custom-fabricated tray or by brushing, or a 0.2% sodium fluoride mouth rinse provides maximal protection while strengthening enamel to prevent additional erosion. Critical to the integrity of the oral cavity is the re-establishment of normal pH; therefore choice should not be a fluoride product that has a low pH.

Employing a home fluoride therapy regimen in addition to professional fluoride applications to remineralize fragile dentition. Daily use of 1.1% neutral sodium fluoride gel, administered either with a custom-fabricated tray or by brushing, or a 0.2% sodium fluoride mouth rinse provides maximal protection while strengthening enamel to prevent additional erosion. Critical to the integrity of the oral cavity is the re-establishment of normal pH; therefore choice should not be a fluoride product that has a low pH.These strategies are aimed at meeting the client’s human needs for integrity of skin and mucous membranes of the head and neck and for a biologically sound dentition.

Dental Hygiene Instrumentation

During instrumentation (scaling, root planing, and removal of extrinsic stain), appropriate pain management techniques are used to protect sensitive hard and soft tissues. Maintaining a moist, clean environment by frequent rinsing of the oral cavity during instrumentation increases comfort especially if the individual has xerostomia. Selective polishing is used when clients have extensive enamel erosion resulting in dentinal exposure. Many polishing pastes are excessively abrasive to dentin (e.g., pumice and/or medium- or coarse-grade agents) and should be avoided. Avoid polishing if the individual does not have extrinsic stains or if the dental hypersensitivity impedes client comfort during stain removal.

Dental hygiene care and necessary palliative treatment of discomfort (e.g., use of desensitization treatments) must be scheduled for both period of quiescence and activity of the eating disorder.

Evaluation

Evaluation of dental hygiene care for the client with an eating disorder consists of the following two parts:

An objective evaluation based on mutual goals previously established by the dental hygienist and client to determine whether the goals have been met, partially met, or unmet

An objective evaluation based on mutual goals previously established by the dental hygienist and client to determine whether the goals have been met, partially met, or unmetObjective Evaluation

For an objective evaluation, the dental hygienists compares baseline data on plaque biofilm accumulation, periodontal status, dental caries, enamel erosion, dentinal hypersensitivity, and oral tissues with data obtained at each subsequent appointment. Many changes that occur over time are subtle and defy detection unless accurate data are collected and compared with previous data. This subtlety is especially true in cases of perimolysis. Clients receiving psychologic treatment but who have not controlled binge and purge behavior may convince the oral health team to believe dental erosion is no longer a threat. Objective comparison of pretreatment and posttreatment oral photographs and study models can verify or negate the client’s subjective report.

Subjective Evaluation

The client’s subjective evaluation provides additional information for future care planning. A caring, professional environment ensures that client confidentiality is maintained while oral health needs are met humanistically. The oral health team must be aware that successful treatment of eating disorders requires intensive therapy followed by many years of maintenance. It is common for clients who have successfully controlled eating disorder behaviors for several weeks or months to revert periodically to previous behaviors. Awareness and verbal acknowledgment of this pattern by the dental hygienist during evaluation permits clients to share honestly about areas of progress as well as areas of distress. This information can then be used in conjunction with the objective data and information from other attending health professionals to guide subsequent care.

On occasion, objective and subjective evaluations conflict with each other. For instance, a client with previously documented dental erosion may report that binge and purge episodes have been under control for 6 months and that she no longer is in need of psychologic treatment. Comparison of current dental status with intraoral photographs and diagnostic models obtained 1 year previously may indicate the erosion is progressive. Discussing these discrepancies with the client and expressing concern about the reported cessation of aftercare therapy are crucial. The oral health team often becomes instrumental in encouraging the client to seek additional psychotherapy when it is apparent that previous therapy outcomes are lapsing. In this situation it may even become necessary for the oral health team to refuse definitive dental treatment unless the client is in therapy and coordination between the psychologist and oral health professionals can occur.