Interpretation of Trauma, and Pulpal and Periapical Lesions

After completion of this chapter, the student will be able to do the following:

• Define the key terms associated with the interpretation of trauma, pulpal lesions, and periapical lesions as viewed on a dental image

• Describe and identify the appearance of crown, root, and jaw fractures as viewed on a dental image

• Describe and identify the appearance of an avulsion as viewed on a dental image

• Describe and identify the appearance of internal and external resorption as viewed on a dental image

• Describe and identify the appearance of pulpal sclerosis, pulpal obliteration, and pulp stones as viewed on a dental image

• Describe and identify the appearance of periapical granuloma, cyst, and abscess as viewed on a dental image

• Describe and identify the appearance of condensing osteitis, sclerotic bone, and hypercementosis as viewed on a dental image

In many cases, the dental image shows changes and thus acts as a detector. Changes associated with trauma, resorption, and pulpal and periapical lesions can all be viewed on dental images. Dental images allow the dental professional to evaluate areas that cannot be examined clinically, such as the roots, pulp chambers, and periapical regions of teeth. Detailed information about trauma, pulpal lesions, and periapical lesions is beyond the scope of this text. For more complete information on these topics, the dental radiographer should consult a text on interpretation.

The purpose of this chapter is to provide a brief overview of the common features of trauma, pulpal lesions, and periapical lesions as viewed on dental images.

Trauma Viewed on Dental Images

Trauma can be defined as an injury produced by an external force. Trauma may affect the crowns and roots of teeth as well as alveolar bone. Trauma may result in fractures of teeth and bone and injuries such as intrusion, extrusion, and avulsion.

Fractures

A fracture can be defined as the breaking of a part. Fractures may affect the crowns and roots of teeth or the bones of the maxilla and the mandible. Whenever a fracture is evident or suspected, dental imaging of the injured area is necessary.

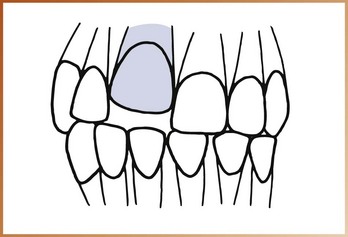

Crown Fractures

Fractures that affect tooth crowns most often involve anterior teeth. Most crown fractures result from a fall or a motor vehicle accident. Crown fractures may involve enamel only; enamel and dentin; or enamel, dentin, and pulp. The missing part of a crown caused by a fracture is evident on a dental image (Figure 35-1). The image allows the dental professional to evaluate the proximity of the pulp chamber to the fracture and to examine the root for any additional fractures.

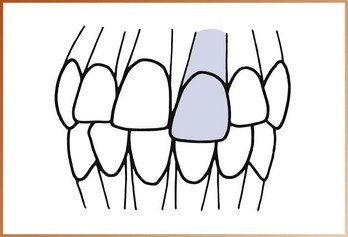

Root Fractures

Root fractures are less common than crown fractures and also result from an accident or a traumatic blow. Root fractures occur most often in the maxillary central incisor region. Tooth roots may be fractured at any level along the root and may involve more than one root of a multirooted tooth. If the x-ray beam is parallel with the plane of the fracture, the root fracture appears as a sharp radiolucent line on a periapical image (Figure 35-2). If the x-ray beam is not parallel with the fracture, adjacent areas of the tooth structure obscure the fracture site; as a result, the fracture cannot be seen on the dental image. With time, root fractures have a tendency to enlarge because of displacement of root fragments, hemorrhage, or edema. A root fracture that was initially overlooked may be identified on a later dental image.

Jaw Fractures

Fractures of the mandible occur more often than do fractures of any other bone of the face and frequently as a result of assaults, accidents, and sports injuries. The panoramic image is recommended for the evaluation of mandibular fractures. On a panoramic image, a mandibular fracture appears as a radiolucent line at the site where the bone has separated (Figure 35-3). Fractures of the maxilla occur less frequently than do mandibular fractures and most often involve anterior alveolar bone and teeth. Maxillary fractures are typically difficult to detect on a dental image.

Injuries

In addition to fractures, trauma may result in the displacement of teeth. Dental images enable the dental professional to evaluate structures after tooth displacement. Tooth displacement includes luxation (intrusion or extrusion) and avulsion.

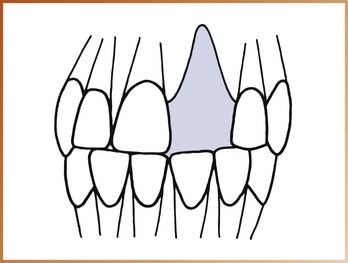

Luxation

Luxation, the abnormal displacement of teeth, can be categorized as either intrusion or extrusion. Intrusion refers to the abnormal displacement of teeth into bone (Figure 35-4). Extrusion refers to the abnormal displacement of teeth out of bone (Figure 35-5). Teeth that have been luxated should be evaluated using a periapical image and examined for root and adjacent alveolar bone fractures, damage to the periodontal ligament, and pulpal problems.

Avulsion

Avulsion is the complete displacement of a tooth from alveolar bone. Most avulsions result from trauma associated with assault or accidental fall. An avulsed tooth is not actually seen on a dental image; instead, a periapical image shows a tooth socket without a tooth (Figure 35-6). Dental images are important in the evaluation of the socket area and should be used to examine the region for splintered bone.

Resorption Viewed on Dental Images

Two types of resorption are associated with teeth: physiologic and pathologic.

Physiologic resorption is a process that is seen with the normal shedding of primary teeth. The roots of a primary tooth are resorbed as the permanent successor moves in an occlusal direction; the primary tooth is shed when resorption of the roots is complete (Figure 35-7).

FIGURE 35-7 Physiologic resorption of a mandibular deciduous second molar. (From Haring JI, Lind LJ: Radiographic interpretation for the dental hygienist, Philadelphia, 1993, Saunders.)

Pathologic resorption is a regressive alteration of tooth structure that is observed when a tooth is subjected to abnormal stimuli.

Resorption of teeth can be described as external or internal, depending on the location of the resorption process.

External Resorption

External resorption is seen along the periphery of the root surface and is often associated with reimplanted teeth, abnormal mechanical forces, trauma, chronic inflammation, tumors and cysts, impacted teeth, or idiopathic causes. External resorption most often affects the apices of teeth; the apical region appears blunted, and the length of the root appears shorter than normal (Figure 35-8). Both the lamina dura and the bone around the blunted apex appear normal.

FIGURE 35-8 External resorption of the apical region of a maxillary lateral incisor. (From Haring JI, Lind LJ: Radiographic interpretation for the dental hygienist, Philadelphia, 1993, Saunders.)

External resorption is not associated with any signs or symptoms and is not detected clinically. Teeth that undergo external resorption do not exhibit mobility. Currently, no effective treatment is available for external resorption.

Internal Resorption

Internal resorption occurs within the crown or root of a tooth and involves the pulp chamber, pulp canals, and surrounding dentin. Precipitating factors such as trauma, pulp capping, and pulp polyps are believed to stimulate the internal resorption process. Internal resorption appears as a round-to-ovoid radiolucency in the midcrown or midroot portion of a tooth (Figures 35-9 and 35-10).

FIGURE 35-9 Internal resorption seen as a round radiolucency in the cervical region of a mandibular second premolar. (From Haring JI, Lind LJ: Radiographic interpretation for the dental hygienist, Philadelphia, 1993, Saunders.)

FIGURE 35-10 Internal resorption seen as a radiolucency in the root of a maxillary central incisor. (From Haring JI, Lind LJ: Radiographic interpretation for the dental hygienist, Philadelphia, 1993, Saunders.)

Internal resorption is generally asymptomatic. Treatment is variable; endodontic therapy may be used if the resorptive process has not physically weakened the tooth. If the tooth is weakened by the resorptive process, extraction is recommended.

Pulpal Lesions Viewed on Dental Images

Many dental procedures require information about the size and location of the pulp cavity before treatment begins. Without dental images, examination of pulp chambers and canals is impossible. Pulpal sclerosis, pulpal obliteration, and pulp stones are common conditions of the pulp cavity that can be seen on dental images.

Pulpal Sclerosis

Pulpal sclerosis, a diffuse calcification of the pulp chamber and pulp canals of teeth, results in a pulp cavity of decreased size (Figure 35-11). For unknown reasons, pulpal sclerosis is associated with aging. No clinical features are associated with pulpal sclerosis; it is generally considered an incidental finding that is of little clinical significance unless endodontic therapy is indicated.

Pulpal Obliteration

Some conditions (e.g., attrition, abrasion, caries, dental restorations, trauma, abnormal mechanical forces) may act as irritants to the pulp and stimulate the production of secondary dentin, which results in obliteration of the pulp cavity. On a dental image, a tooth with pulpal obliteration does not appear to have a pulp chamber or pulp canals (Figure 35-12). Teeth that exhibit pulpal obliteration are nonvital and therefore do not require treatment.

Pulp Stones

Pulp stones are calcifications that are found in the pulp chamber or pulp canals of teeth. The cause of pulp stones is unknown. On a dental image, pulp stones appear as round, ovoid, or cylindrical radiopacities; some pulp stones may conform to the shape of the pulp chamber or canal (Figures 35-13 and 35-14). Pulp stones may vary in shape, size, and number. Pulp stones do not cause any problems and therefore do not require treatment.

Periapical Lesions Viewed on Dental Images

A periapical lesion is a lesion that is located around the apex (tip of the root) of a tooth. The use of dental imaging is particularly important in the identification of periapical problems. Periapical lesions cannot be evaluated on a clinical basis alone. On dental images, periapical lesions may appear either radiolucent (dark or black) or radiopaque (light or white).

Periapical Radiolucencies

Periapical granulomas, cysts, and abscesses are common periapical radiolucencies that can be seen on dental images. These lesions cannot be diagnosed by their appearances alone; instead, diagnosis is based on clinical features, dental imaging, and microscopic appearances. Because it is impossible to distinguish these three periapical lesions based on their dental image features, the dental radiographer should refer to these lesions simply as “periapical radiolucencies.”

Periapical Granuloma

A periapical granuloma is a localized mass of chronically inflamed granulation tissue at the apex of a nonvital tooth. It results from pulpal death and necrosis and is the most common sequela of pulpitis (inflammation of the pulp). A periapical granuloma may give rise to a periapical cyst or periapical abscess. A tooth with a periapical granuloma is typically asymptomatic but has a previous history of prolonged sensitivity to heat or cold. Treatment for a periapical granuloma may include endodontic therapy or removal of the tooth with curettage of the apical region.

On a dental image, a periapical granuloma is initially seen as a widened periodontal ligament space at the root apex (Figure 35-15). With time, the widened periodontal ligament space enlarges and appears as a round or ovoid radiolucency (Figure 35-16). The lamina dura is not visible between the root apex and the apical lesion.

Periapical Cyst

A periapical cyst (also known as a radicular cyst) is a lesion that develops over a prolonged period; cystic degeneration takes place within a periapical granuloma and results in a periapical cyst. The periapical cyst results from pulpal death and necrosis. Periapical cysts are the most common of all tooth-related cysts and comprise 50% to 70% of all cysts in the oral region. Periapical cysts are typically asymptomatic. Treatment may include endodontic therapy or extraction of the tooth as well as curettage of the apical region. On a dental image, the typical periapical cyst appears as a round or ovoid radiolucency (Figure 35-17).

Periapical Abscess

A periapical abscess is a localized collection of pus in the periapical region of a tooth that results from pulpal death. Periapical abscesses may be acute or chronic. An acute periapical abscess has features of an acute pus-producing process and inflammation. An acute abscess may result from an acute inflammation of the pulp or an area of chronic infection, such as a periapical granuloma. A chronic periapical abscess has features of a long-standing, low-grade, pus-producing process. A chronic abscess may develop from an acute abscess or a periapical granuloma.

An acute periapical abscess is painful; the pain may be intense, throbbing, and constant. The tooth is nonvital and is sensitive to pressure, percussion, and heat. Chronic periapical abscesses are usually asymptomatic because the pus drains through bone or the periodontal ligament space. Clinically, a gum boil (parulis) may be seen in the apical region of the tooth at the site of drainage. Treatment of the periapical abscess includes drainage and endodontic therapy or extraction.

With an acute periapical abscess, no change may be evident on a dental image. Early changes viewed on dental images include increased widening of the periodontal ligament space (Figure 35-18). A chronic periapical abscess appears as a round or ovoid apical radiolucency with poorly defined margins (Figure 35-19). The lamina dura cannot be seen between the root apex and the radiolucent lesion.

FIGURE 35-18 An increased widening of the periodontal ligament space seen in the periapical region of the mandibular first molar. (From Haring JI, Lind LJ: Radiographic interpretation for the dental hygienist, Philadelphia, 1993, Saunders.)

FIGURE 35-19 Periapical radiolucencies associated with mandibular premolars. (From Haring JI, Lind LJ: Radiographic interpretation for the dental hygienist, Philadelphia, 1993, Saunders.)

It is important to differentiate between a periapical abscess and a periodontal abscess. A periodontal abscess results from bacterial infection within the walls of periodontal tissues and typically results from a pre-existing periodontal condition. The most common symptom of a periodontal abscess is pain. Therapy includes deep scaling and débridement of periodontal tissues, although the prognosis for the tooth’s periodontal health depends on the amount of bone loss and mobility.

To summarize, the term periapical abscess refers to an infection in the pulp of a tooth; periodontal abscess refers to a purulent inflammation within periodontal tissues.

Periapical Radiopacities

Condensing osteitis, sclerotic bone, and hypercementosis are some common periapical radiopacities seen on dental images. Unlike periapical radiolucencies, periapical radiopacities can be diagnosed on the basis of dental images, clinical information, and patient history.

Condensing Osteitis

Condensing osteitis (also known as chronic focal sclerosing osteomyelitis) is a well-defined radiopacity that is seen below the apex of a nonvital tooth with a history of long-standing pulpitis (Figure 35-20). The opacity represents a proliferation of periapical bone that is a result of low-grade inflammation or mild irritation. The inflammation that stimulates condensing osteitis occurs in response to pulpal necrosis. Condensing osteitis may vary in size and shape and does not appear to be attached to the tooth root.

FIGURE 35-20 A diffuse radiopacity seen along the roots of a mandibular first molar. (From Haring JI, Lind LJ: Radiographic interpretation for the dental hygienist, Philadelphia, 1993, Saunders.)

Condensing osteitis is the most common periapical radiopacity observed in adults. The tooth most frequently involved is the mandibular first molar. Teeth associated with condensing osteitis are nonvital and typically have a large carious lesion or a large restoration. Because condensing osteitis is believed to represent only a physiologic reaction of bone to inflammation, no treatment is necessary.

Sclerotic Bone

Sclerotic bone (also known as osteosclerosis or idiopathic periapical osteosclerosis) is a well-defined radiopacity that is seen below the apices of vital, noncarious teeth (Figure 35-21). The cause of sclerotic bone is unknown; however, it is not believed to be associated with inflammation. The lesion is not attached to a tooth and varies in size and shape. The margins may appear smooth or irregular and diffuse. The borders are continuous with adjacent normal bone, and no radiolucent outline is seen. Sclerotic bone is asymptomatic and is usually discovered during routine dental imaging.

Hypercementosis

Hypercementosis is the excessive deposition of cementum on root surfaces. Hypercementosis results from supra-eruption, inflammation, or trauma; sometimes there is no obvious cause. On dental images, hypercementosis is visible as an excessive amount of cementum along all or part of a root surface (Figure 35-22). The apical area is most often affected and appears enlarged and bulbous. Root areas affected by hypercementosis are separated from periapical bone by a normal-appearing periodontal ligament space; the surrounding lamina dura appears normal as well.

FIGURE 35-22 Hypercementosis of a maxillary premolar. (From Haring JI, Lind LJ: Radiographic interpretation for the dental hygienist, Philadelphia, 1993, Saunders.)

No signs or symptoms are associated with hypercementosis; most cases are discovered during routine dental imaging. Teeth affected by hypercementosis are vital and do not require treatment.

Summary

• Changes associated with trauma, resorption, and pulpal and periapical lesions can be viewed on dental images.

• Dental imaging allows the dental professional to evaluate the roots, pulp cavities, and periapical regions of teeth, all of which are areas that cannot be examined clinically.

• Dental imaging is important in the evaluation of trauma and injury and can be used for diagnostic, treatment, and post-treatment purposes.

• Dental imaging is useful in the evaluation of tooth and jaw fractures and of tooth injuries, including intrusion, extrusion, and avulsion.

• Dental imaging is useful in identifying regressive alterations of teeth, such as external and internal resorption. These alterations are usually asymptomatic and discovered only through dental imaging.

• Dental imaging is also useful in examining and in obtaining information about the pulp cavity. Pulpal sclerosis, obliteration of the pulp cavity, and pulp stones are common conditions that can be viewed on dental images.

• Periapical lesions cannot be examined without the aid of dental images. Examples include periapical granulomas, periapical cysts, periapical abscesses, condensing osteitis, sclerotic bone, and hypercementosis.

Frommer, HH, Savage-Stabulas, JJ, Pulpal and periapical lesions. Radiology for the dental professional, ed 9, St. Louis, Mosby, 2011.

Haring, JI, Lind, LJ. Trauma, pulpal and periapical lesions. In: Radiographic interpretation for the dental hygienist. Philadelphia: Saunders; 1993.

Herrera, D, Roldán, S, Sanz, M. The periodontal abscess: A review. J Clin Periodontol. 2000;27(6):377–386.

Johnson, ON, McNally, MA, Essay, CE, Preliminary interpretation of the radiographs. Essentials of dental radiography for dental assistants and hygienists, ed 8, Upper Saddle River, NJ, Pearson Education, Inc, 2007.

Manson-Hing, LR, Interpretation and value of radiographs. Fundamentals of dental radiography, ed 3, Philadelphia, Lea & Febiger, 1990.

Miles, DA, Van Dis, ML, Jensen, CW, Williamson, GF, Basics of interpretation: normal versus abnormal and common radiographic presentation. Radiographic imaging for the dental team, ed 4, Philadelphia, Saunders, 2009.

White, SC, Pharoah, MJ, Inflammatory lesions of the jaws. Oral radiology: principles of interpretation, ed 6, St. Louis, Mosby, 2009.

White, SC, Pharoah, MJ, Trauma to teeth and facial structures. Oral radiology: principles of interpretation, ed 6, St. Louis, Mosby, 2009.

Matching

For questions 1 to 6, match the terms with the appropriate definition.

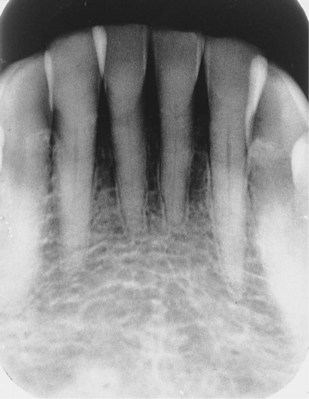

Identification

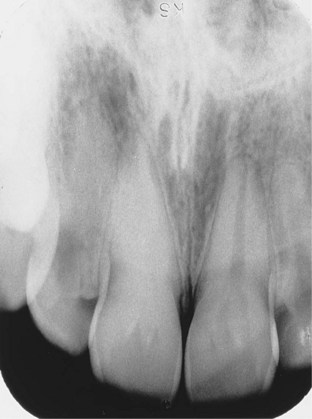

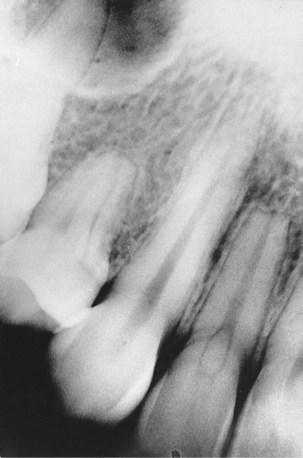

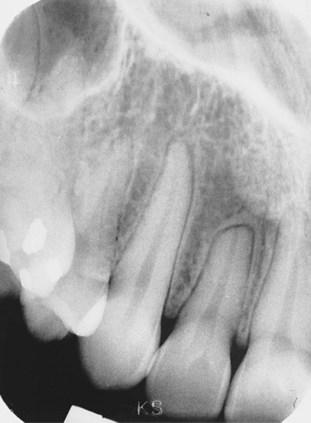

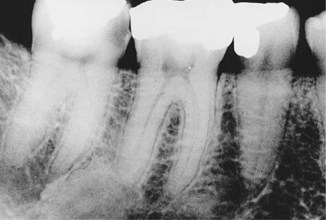

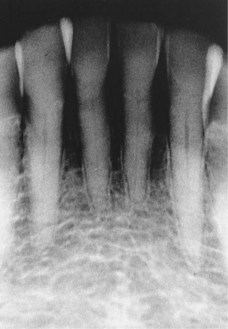

For questions 7 to 12, refer to Figures 35-23 to 35-28. Identify or describe the periapical and pulpal lesions shown in each figure.

FIGURE 35-23 (From Haring JI, Lind LJ: Radiographic interpretation for the dental hygienist, Philadelphia, 1993, Saunders.)

FIGURE 35-24 (From Haring JI, Lind LJ: Radiographic interpretation for the dental hygienist, Philadelphia, 1993, Saunders.)

FIGURE 35-25 (From Haring JI, Lind LJ: Radiographic interpretation for the dental hygienist, Philadelphia, 1993, Saunders.)

FIGURE 35-26 (From Haring JI, Lind LJ: Radiographic interpretation for the dental hygienist, Philadelphia, 1993, Saunders.)

FIGURE 35-27 (From Haring JI, Lind LJ: Radiographic interpretation for the dental hygienist, Philadelphia, 1993, Saunders.)

FIGURE 35-28 (From Haring JI, Lind LJ: Radiographic interpretation for the dental hygienist, Philadelphia, 1993, Saunders.)